Abstract

Health systems and polices have a critical role in determining the manner in which health services are delivered, utilized and affect health outcomes. ‘Health' being a state subject, despite the issuance of the guidelines by the central government, the final prerogative on implementation of the initiatives on newborn care lies with the states. This article briefly describes the public health structure in the country and traces the evolution of the major health programs and initiatives with a particular focus on newborn health.

Background

Report on the Health Survey and Development Committee, commonly referred to as the Bhore Committee Report, 1946, has been a landmark report for India, from which the current health policy and systems have evolved.1 The recommendation for three-tiered health-care system to provide preventive and curative health care in rural and urban areas placing health workers on government payrolls and limiting the need for private practitioners became the principles on which the current public health-care systems were founded. This was done to ensure that access to primary care is independent of individual socioeconomic conditions. However, lack of capacity of public health systems to provide access to quality care resulted in a simultaneous evolution of the private health-care systems with a constant and gradual expansion of private health-care services.2

Although the first national population program was announced in 1951, the first National Health Policy of India (NHP) got formulated only in 1983 with its main focus on provision of primary health care to all by 2000.3 It prioritized setting up a network of primary health-care services using health volunteers and simple technologies establishing well-functioning referral systems and an integrated network of specialty facilities. NHP 2002 further built on NHP 1983, with an objective of provision of health services to the general public through decentralization, use of private sector and increasing public expenditure on health care overall.4 It also emphasized on increasing the use of non-allopathic form of medicines such as ayurveda, unani and siddha, and a need for strengthening decision-making processes at decentralized state level.

Due to the India's federalized system of government, the areas of governance and operations of health system in India have been divided between the union and the state governments. The Union Ministry of Health & Family Welfare is responsible for implementation of various programs on a national scale (National AIDS Control Program, Revised National Tuberculosis Program, to name a few) in the areas of health and family welfare, prevention and control of major communicable diseases, and promotion of traditional and indigenous systems of medicines and setting standards and guidelines, which state governments can adapt. In addition, the Ministry assists states in preventing and controlling the spread of seasonal disease outbreaks and epidemics through technical assistance.5 On the other hand, the areas of public health, hospitals, sanitation and so on come under the purview of the state, making health a state subject. However, areas having wider ramification at the national level, such as family welfare and population control, medical education, prevention of food adulteration, quality control in manufacture of drugs, are governed jointly by the union and the state government.

Public health-care infrastructure in India

India has a mixed health-care system, inclusive of public and private health-care service providers.6 However, most of the private health-care providers are concentrated in urban India, providing secondary and tertiary care health-care services. The public health-care infrastructure in rural areas has been developed as a three-tier system based on the population norms and described below.7 The urban health system is discussed in the article on Urban Newborn.

Sub-centers

A sub-center (SC) is established in a plain area with a population of 5000 people and in hilly/difficult to reach/tribal areas with a population of 3000, and it is the most peripheral and first contact point between the primary health-care system and the community. Each SC is required to be staffed by at least one auxiliary nurse midwife (ANM)/female health worker and one male health worker (for details see recommended staffing structure under the Indian Public Health Standards (IPHS)). Under National Rural Health Mission (NRHM), there is a provision for one additional ANM on a contract basis.

SCs are assigned tasks relating to interpersonal communication in order to bring about behavioral change and provide services in relation to maternal and child health, family welfare, nutrition, immunization, diarrhea control and control of communicable diseases programs. The Ministry of Health & Family Welfare is providing 100% central assistance to all the SCs in the country since April 2002 in the form of salaries, rent and contingencies in addition to drugs and equipment.

Primary health centers

A primary health center (PHC) is established in a plain area with a population of 30 000 people and in hilly/difficult to reach/tribal areas with a population of 20 000, and is the first contact point between the village community and the medical officer. PHCs were envisaged to provide integrated curative and preventive health care to the rural population with emphasis on the preventive and promotive aspects of health care. The PHCs are established and maintained by the State Governments under the Minimum Needs Program (MNP)/Basic Minimum Services (BMS) Program. As per minimum requirement, a PHC is to be staffed by a medical officer supported by 14 paramedical and other staff. Under NRHM, there is a provision for two additional staff nurses at PHCs on a contract basis. It acts as a referral unit for 5-6 SCs and has 4-6 beds for in-patients. The activities of PHCs involve health-care promotion and curative services.

Community health centers

Community health centers (CHCs) are established and maintained by the State Government under the MNP/BMS program in an area with a population of 120 000 people and in hilly/difficult to reach/tribal areas with a population of 80 000. As per minimum norms, a CHC is required to be staffed by four medical specialists, that is, surgeon, physician, gynecologist/obstetrician and pediatrician supported by 21 paramedical and other staff. It has 30 beds with an operating theater, X-ray, labor room and laboratory facilities. It serves as a referral center for PHCs within the block and also provides facilities for obstetric care and specialist consultations.

First referral units

An existing facility (district hospital, sub-divisional hospital, CHC) can be declared a fully operational first referral unit (FRU) only if it is equipped to provide round-the-clock services for emergency obstetric and newborn care, in addition to all emergencies that any hospital is required to provide. It should be noted that there are three critical determinants of a facility being declared as a FRU: (i) emergency obstetric care including surgical interventions such as caesarean sections; (ii) care for small and sick newborns; and (iii) blood storage facility on a 24-h basis.

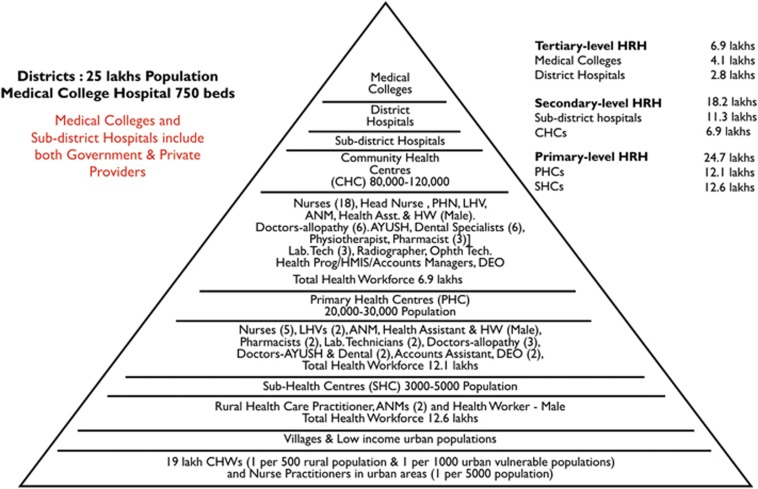

Schematic diagram of the Indian Public Health Standard (IPHS) norms, which decides the distribution of health-care infrastructure as well the resources needed at each level of care is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Indian Public Health System. Reprinted with permission from National Rural Health Mission, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India.21

On the basis of the distributional pyramid, currently there are 722 district hospitals, 4833 CHCs, 24 049 PHCs and 148 366 SCs in the country.

National rural health mission: strengthening of rural public health system

NRHM, launched in 2005, was a watershed for the health sector in India. With its core focus to reduce maternal and child mortality, it aimed at increased public expenditure on health care, decreased inequity, decentralization and community participation in operationalization of health-care facilities based on IPHS norms. It was also an articulation of the commitment of the government to raise public spending on health from 0.9% to 2-3% of GDP.8

Seeking to improve access of rural people, especially poor women and children, to equitable, affordable, accountable and effective primary health care, NRHM (2005-2012) aimed to provide effective health care to the rural population throughout the country with special focus on 18 states having weak public health indicators and/or weak infrastructure. Within the mission there are high-focused and low-focused states and districts based on the status of infant and maternal mortality rates, and these states are provided additional support, both financially and technically. Gradually it has emerged as a major financing and health sector reform strategy to strengthen the state health systems.

Major initiatives have been undertaken under NRHM for architectural correction of the rural health system—in terms of availability of human resources, program management, physical infrastructure, community participation, financing health care and use of information technology. Some of these activities are tabulated below (Table 1).

Table 1. Glimpse of activities under the National Rural Health Mission (2005–2013).

| Human resources (new providers) | 931 239 Accredited social health activists |

| 27 421 Doctors at PHCs, 4078 specialists at CHCs* | |

| 40 119 Staff nurses | |

| 72 984 ANM | |

| Human resources (program management) | 618 District Program Managers and 633 District Accounts Managers deployed |

| Ambulance | More than 30 000 ambulances deployed nation wide |

| Community participation structure | 499 210 Village level Health Sanitation and Nutrition Committees (VHSNCs) created |

| 29 063 Patient Welfare Committees created at public facilities | |

| Web-based mother and child tracking system | Tracking 105 million mother–baby dyads |

| Finances provided | A total of 21 billion USD invested (2005–2015) by the central government |

| Other | Between 2009 and 2013, graduate medical capacity increased by 54% and post graduate medical seats by 74% |

The mission emphasized on increasing health-care delivery points as well as facilities available at the health-care delivery points. It not only focused on increasing the number of physicians, specialists, staff nurses, as well as ANMs, but also gave importance to increasing the production capacity of medical colleges at graduate and post graduate levels. Physical infrastructure was enhanced by creating more health centers, newborn care units and renovating existing centers, which increased the capacity of health systems to treat more mothers and children. Special efforts were made to strengthen community participation through the formation of health committees at the village level and patient welfare committees at public health-care facilities. Information technology was used to track delivery of services to the mother and child. And all this has been an outcome of increased financial assistance by the central government and increased rates of utilization. During the period 2005-2013, the total investment by the central government equalled nearly 17 billion USD.

National programs and initiatives for newborn health

In India, major policies and national programs are planned and implemented during the 5-year planning phase. Despite the fact that no explicit programs on newborn care have been designed in the past, various programs and the 5-year plans in the country had focused on provision of services for mothers and children.11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 The launch of the CSSM program in 1992, for the first time included an essential newborn care component, and specifically integrated newborn care in the maternal and child health program. Thereafter, newborn care started receiving more attention and resources in the subsequent programs and initiatives.

Under NRHM, newborn health received unprecedented attention and resources with the launch of several new initiatives aimed at reducing the burden of maternal and newborn mortality and morbidity.

In February 2013, the government launched the strategic approach, reproductive, maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health (RMNCH+A),20 to accelerate actions for equity, harmonization and improved coverage of services. Although the RMNCH+A approach recognized that newborn health and survival is inextricably linked to women's health, across all life stages, it also clearly emphasized interlinkages between each of the five life stages with adolescent health as a distinct life stage, and connected community, outreach- and facility-based services. On the basis of this approach, the central government has taken vital policy decisions to combat major causes of newborn death, providing special attention to sick newborns, babies born too soon (premature) and too small (small for gestational age).

Specific interventions for the newborn included under the RMNCH+A strategy include:

Delivery of antenatal care package and tracking of high-risk pregnancies;

Skilled care at birth, emergency obstetric care and postpartum care for mother;

Home-based newborn care and prompt referral;

Facility-based care of the sick newborn;

Integrated management of common childhood illnesses (diarrhea, pneumonia and malaria)

The strategy identifies the roles to be played at each level of care and the service provision and health systems requirement in terms of manpower and commodities for each of them. (Figure 1)21, 22, 23 SCs and PHCs are designated as delivery points; CHCs (which are the FRUs) and district hospitals have been made functional 24 × 7 to provide basic and comprehensive obstetric and newborn-care services. Only those health facilities are designated as FRUs that have the facilities and manpower to conduct a caesarean section. Moreover, the strategic document identifies the required capacity building efforts for which NRHM has produced manuals. So far out of 116 capacity building manuals, 10 are dedicated to newborns. The document also has the guidance for reaching remote inaccessible areas to ensure maternal and child Health care.

One of the key aspects of the document and one that certainly contributes to its comprehensive nature is the involvement of various stakeholders in its development. Apart from the core drafting team of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, the technical support team is represented by the development partners, academic partners, practitioners, nationally and internationally. This has proved to be an important step for wider adaptation of processes and is crucial for implementation success.

Conclusion

India has been focussing on providing comprehensive care to mother and child. It has framed policies that allow the design and implementation of programs on newborn care in an inclusive manner. However, looking at the pace of achievements of the targets so far and future targets, it needs to focus more on framing of the policies in terms of building capacity of existing human resources, enhancing further allocation of finances dedicated toward newborn care, identifying areas through operational research, which can enhance quantity and quality of care for newborn care in India. The path is set and we need to operationalize and move forward.

Acknowledgments

This article was supported by Save the Children's Saving Newborn Lives program.

Footnotes

BP and RK are affiliated to Saving Newborn Lives, Save the Children, India (Sponsor of the Supplement). The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ma S, Sood N. A Comparison of the Health Systems in China and India. Rand Corporation: CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Peters DH, Rao KS, Fryatt R. Lumping and splitting: the health policy agenda in India. Health Policy Plan 2003; 18(3): 249–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOHFW National Health Policy. New Delhi Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Govt. of India 1983. Available at: http://www.nhp.gov.in/sites/default/files/pdf/nhp_1983.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2016).

- MOHFW National Health Policy. New Delhi Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Govt. of India 2002. Available at: http://www.nhp.gov.in/sites/default/files/pdf/NationaL_Health_Pollicy.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2016).

- MOHFW. Annual Report 2012-2013. Available at: http://mohfw.nic.in/index2.php?lang=1&level=2&sublinkid=3854&lid=2028 (accessed on 15 August 2014).

- Sheikh K, Saligram PS, Hort K. What explains regulatory failure? Analysing the architecture of health care regulation in two Indian states. Health Policy Plan 2015; 30(1): 39–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOHFW Indian Public Health Standards. Revised guidelines New Delhi Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Govt. of India 2012. Available at: http://nrhm.gov.in/nhm/nrhm/guidelines/indian-public-health-standards.html (accessed on 3 April 2016).

- MOHFW. National Rural Health Mission- Framework for Implementation. Available at: http://nrhm.gov.in/images/pdf/about-nrhm/nrhm-framework-implementation/nrhm-framework-latest.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2014).

- Quarterly NRHM MIS reports. National Executive Summary. Child Health Division, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. 2015. Available at: http://nrhm.gov.in/images/pdf/mis-report/Sept-2015/1-NRHM.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2016).

- Rural Health Statistics. Child Health Division, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. 2014-15. Available at: https://nrhm-mis.nic.in/RURAL%20HEALTH%20STATISTICS/(A)RHS%20-%202015/CoverPage.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2016).

- MCHIP India's Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child, and Adolescent Health (RMNCH+A) Strategy-A Case of Extraordinary Government Leadership. The Maternal and Child Health Integrated Program (MCHIP), USAID 2014.

- 5th Five year Plan (1974-79)-Chapter 5. Planning Commission, Govt. of India, New Delhi. Available at: http://planningcommission.nic.in/plans/planrel/fiveyr/welcome.html. (accessed on 13 April 2014.

- 6th Five year Plan (1980-85)-Chapter 22. Planning Commission, Govt. of India, New Delhi. Available at: http://planningcommission.nic.in/plans/planrel/fiveyr/welcome.html (accessed on 13 April 2014).

- 7th Five Year Plan (1985-90)-Vol-II, Chapter 11. Planning Commission, Govt. of India, New Delhi. Available at: http://planningcommission.nic.in/plans/planrel/fiveyr/welcome.html (accessed on 13 April 2014).

- 8th Five Year Plan (1992-97)-Vol-II, Chapter 12. Planning Commission, Govt. of India, New Delhi. Available at: http://planningcommission.nic.in/plans/planrel/fiveyr/welcome.html (accessed on 13 April 2014).

- 9th Five Year Plan (1997-2002)-Vol-II, Chapter 3.4. Planning Commission, Govt. of India, New Delhi. Available at: http://planningcommission.nic.in/plans/planrel/fiveyr/9th/vol2/v2c3-4.htm (accessed on 13 April 2014).

- 10th Five Year Plan (2002-2007)-Vol-II, Chapter 2.8. Planning Commission, Govt. of India, New Delhi. Available at: http://planningcommission.nic.in/plans/planrel/fiveyr/10th/volume2/v2_ch2_8.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2014).

- 11th Five Year Plan (2007-2012)-Vol-II, Chapter 3. Planning Commission, Govt. of India, New Delhi. Available at: http://planningcommission.nic.in/plans/planrel/fiveyr/11th/11_v2/11v2_ch3.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2014).

- 12th Five Year Plan (2012-17)- Vol-III, chapter 20. Planning Commission, Govt. of India, New Delhi. Available at: http://planningcommission.nic.in/plans/planrel/fiveyr/12th/pdf/12fyp_vol3.pdf (accessed 13 April 2014).

- A Strategic Approach to Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health (RMNCH+A) in India. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Govt. of India, New Delhi. Available at: http://nrhm.gov.in/images/pdf/programmes/rmncha-strategy.pdf (accessed on 13 August 2014).

- Human resources for health. National Rural Health Mission, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Child Health Division, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. 2011. Available at: uhc-india.org/reports/hleg_report_chapter_4.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2016).

- RGI. sample Registration System. Statistical Report. Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India, Ministry of Home Affairs, New Delhi. Available at: http://www.censusindia.gov.in/vital_statistics/SRS_Reports_2013.html (accessed on 10 April 2016).

- RGI Special Bulletin on Maternal Mortality In India 2010-12. Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India, Ministry of Home Affairs, New Delhi. Available at: http://www.censusindia.gov.in/vital_statistics/SRS_Bulletins/MMR_Bulletin-2010-12.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2016).