Abstract

The CH4 emissions from soil were influenced by the changeable CH4 concentrations and diffusions in soil profiles, but that have been subjected to nitrogen (N) and biochar amendment over seasonal and annual time frames. Accordingly, a two-year field experiment was conducted in southeastern China to determine the amendment effects on CH4 concentrations and diffusive effluxes as measured by a multilevel sampling probe in paddy soil during two cycles of rice-wheat rotations. The results showed that the top 7-cm soil layers were the primary CH4 production sites during the rice-growing seasons. This layer acted as the source of CH4 generation and diffusion, and the deeper soil layers and the wheat season soil acted as the sink. N fertilization significantly increased the CH4 concentration and diffusive effluxes in the top 7-cm layers during the 2013 and 2014 rice seasons. Following biochar amendment, the soil CH4 concentrations significantly decreased during the rice season in 2014, relative to the single N treatment. Moreover, 40 t ha−1 biochar significantly decreased the diffusive effluxes during the rice seasons in both years. Therefore, our results showed that biochar amendment is a good strategy for reducing the soil profile CH4 concentrations and diffusive effluxes induced by N in paddy fields.

Methane (CH4) is an important greenhouse gas with a global warming potential that is 34 times greater than that of the equivalent mass of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere1. Paddy fields are considered an important source of atmospheric CH4. It is estimated that the CH4 emissions from Chinese paddy fields were 7.4 Tg yr−1, and they contributed to 29.9% of the global total annual emissions2. Rice-wheat rotation systems are ubiquitous in South and East Asia, and they play an important role in modulating the climate3. Fertilizer nitrogen (N) is usually required to achieve optimal yields, but when it is applied in excess, there is increased risk of pollution, such as soil acidification and increased emissions of greenhouse gas4,5, which will affect agricultural production and the ecological environment6,7. Therefore, it has become essential to explore the reasonable management steps that can be taken to achieve CH4 emissions mitigation without reducing crop yields from the agroecosystem by gaining a better understanding of CH4 production and emission processes.

Soil CH4 emissions depend not only on the production or oxidation rate but also on the quantity of pathways; these emissions are the result of a combination of production, oxidation and transmission8. The biological production of CH4 is mainly dominated by methanogenic archaea, and there is recent evidence for anaerobic fungi and plants that can release CH49. However, before CH4 is released to the atmosphere, part of it was consumed by methanotrophs in the soil or water layer10. The study of CH4 production and distribution laws is helpful for exploring the soil-atmosphere exchange mechanism of CH4 in paddy soil. Yan et al.11 found that CH4 production in the points near the soil surface have the fastest growth rates and the shortest times to reach steady state, with the maximum concentration. Liu et al.12 reported that CH4 production primarily occurred in the reduced layer in a wetland, and part of the CH4 was oxidized when passing the oxidation zone. Yagi et al.13 analyzed Japanese rice fields and found that the top 1 cm layer always showed the highest oxidation potential in both of the plots, either in the surface layer of the paddy soil or in the rhizosphere of rice plants, and the oxidation rate in the deeper layer was nearly 58% lower than that of the surface soil. An incubation study with nine types of Philippine soil and two type of Indian soil by Mitra et al.14 revealed that the soil type has a great impact on the production potential of CH4 in the surface soil layer, and the topsoil was the primary source of CH4 in flooded rice fields, accounting for 99.9% of the total CH4 production; the contribution rate of the subsoil layer was only 0.05%. Kamman et al.15 analyzed the CH4 concentration in grassland soil profiles and showed that even in aerobic environments, there was CH4 production, and the reason might be related to the anaerobic micro-domain or other soil factors.

The spatial and temporal variability distribution of this gas in the soil profile will directly affect the gas exchange between the soil and the atmosphere16. Many studies on CH4 emissions have been based on the use of the closed-chamber method15,17. Using the closed-chamber method to measure CH4 emissions usually represents the net result of transport, consumption and production of CH4 in the soil18. Thus, the closed-chamber method applies to only the surface emission efflux, and there is a lack of research on the CH4 diffusion and transfer process in the soil profile. It is important to allow additional assessment of the vertical dimensions of the CH4 sources and sinks in the soil profile. The gradient method has already been applied to determine the soil-atmosphere exchange of CH419. Wolf et al.16 reported that the gradient method can provide additional information about the depth profile of net gas production. Furthermore, problems associated with the use of the chambers, such as the disturbance of the concentration gradient between the soil and atmosphere and changes in the microclimate of the chamber, can be reduced or avoided18. Calculating the soil gas diffusive efflux using the concentration gradient method can provide a better understanding of the generation, storage, and transfer process of soil profile gas, and it can be used to estimate CH4 emissions at the same time20. There are still some limitations using the concentration gradient method that the soil was not always homogeneous and the device are limited by water flooding, even homogeneous soils can exhibit a transient soil water profile after rainfalls21. Previous researches were mainly concentrated on the soil CH4 profiles in different regions of upland soil or homogeneous soil22. We improved and applied the novel device to collect soil gas profiles under both drought and flooding conditions19.

There are a variety of impact factors on CH4 emissions from the soil, such as the fertilizer management23, field environmental factors24 and water regime17. It has been recognized that various agricultural practices including water regimes and organic matter amendments should be considered to estimate CH4 emission. During rice growing period, water management such as periodic drainage and intermittent irrigation can significantly reduce CH4 emissions25. Nitrogen fertilization plays an important role in CH4 emissions, but previous results on the effects of N fertilizers on CH4 emissions from rice fields are still inconsistent. Cai et al.23 proposed that a certain amount of urea could suppress CH4 emissions, and Wang et al.5 reported that urea can promote CH4 emissions. In the past few years, biochar has become an intensively discussed topic because of its proposed impacts of increased soil carbon and fertility26. The application of biochar can also increase plant growth by improving soil physical, chemical, and biological properties, including the soil structure, nutrient availability, and water and nutrient retention27,28. Biochar is an excellent source of organic matter to add to soil because it acts as a support material for several applications and adsorbents that remove pollutants29. Although comparatively few studies have addressed CH4 emissions after biochar addition30,31, Knoblauch et al.32 found that there was no significant difference in CH4 emissions between the biochar plot and the control plot during the following year, indicating that the time effect of biochar amendments needs to be further defined. Field studies of the biochar effect on the profile distribution and diffusion of CH4 from paddy soil is still limited. Moreover, the studies are necessary to understand the interannual variability of the combined biochar amendment and N fertilizer on the production site and diffusion of CH4 in the soil profile. Therefore, more studies are clearly needed to build a better understanding of biochar’s effects on the CH4 emissions from soil profiles with rice-wheat cropping rotations during consecutive years.

We established, a two-year field experiment from June 2013 to May 2015 with the following objectives: (1) to evaluate N fertilizer, biochar and their interaction effects on the distribution and diffusion of CH4 within soil profiles (2) to address the CH4 production location, diffusion and concentration within the soil profiles, and (3) to estimate the sources and sinks of CH4 in different soil depths during the rice-wheat rotations over seasonal and annual time frames from 2013 to 2015.

Results

CH4 concentrations along soil profiles in the rice-wheat rotation system

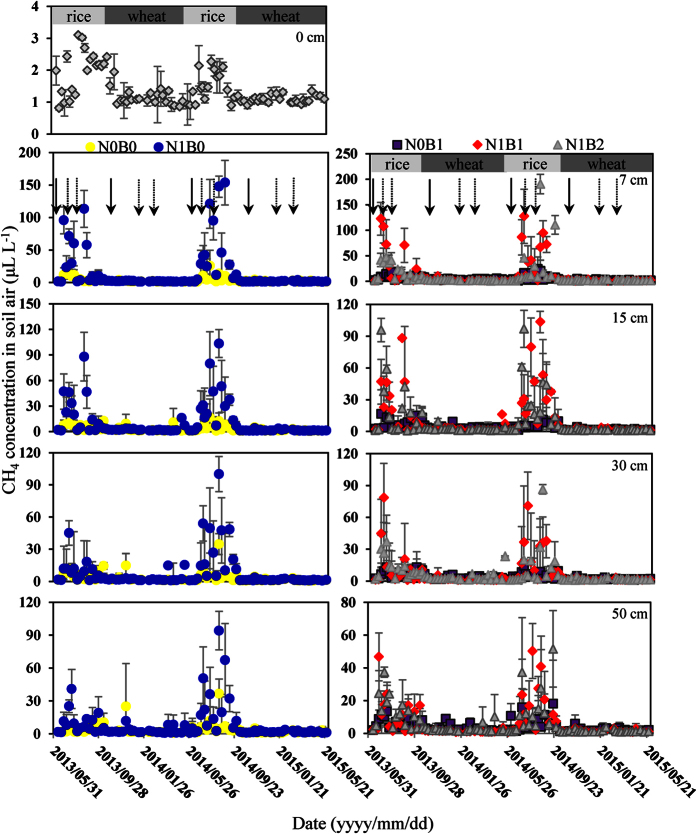

By observing the soil CH4 profile concentrations in different soil depths from June 2013 to May 2015 (Fig. 1), we found that the CH4 concentration dynamics showed a similar pattern between two rice-wheat rotations. As shown in Fig. 1, all the treatments revealed similar temporal patterns in the CH4 concentrations during these two years, and the profile concentrations of CH4 were higher during the rice seasons. However, no obvious pattern (very low concentrations; close to 0 μL L−1) was detected during the wheat seasons, which indicated that CH4 was essentially only produced and accumulated during the flooded rice seasons.

Figure 1. Seasonal dynamics of CH4 concentrations at different soil depths in the rice-wheat annual rotation system, with different N and biochar additions.

The error bars show the standard deviations (n = 3). The solid and dashed arrows indicate basal fertilization and topdressing, respectively. N0B0 (no nitrogen (N) and biochar (B) amended) as control, N0B1 (only biochar amended, 20 t hm−2), N1B0 (only N fertilizer amended, 250 kg hm−2 urea), N1B1 (250 kg hm−2 urea and 20 t hm−2 biochar amended), and N1B2 (250 kg hm−2 urea and 40 t hm−2 biochar). The concentration of CH4 at 0 cm was used as the mean surface air sample which close to the background atmospheric value at the sampling time.

In comparison with the N0B0, the average CH4 concentrations from four depths in the N1B0, N1B1 and N1B2 treatments significantly increased by 261%, 205% and 165% (P < 0.05), respectively, especially during the second year, with increases by 413%, 285% and 205%, indicating that N fertilization significantly increased the average CH4 concentrations in our study (Table 1). Throughout the 2014–2015 growing season, the soil profile CH4 concentrations in the N1B0, N1B1 and N1B2 treatments during the rice-growing stage were significantly higher than the concentrations from 2013–2014, which suggests that there was clear inter-annual variability in the CH4 concentration during rice growing stages (Table 2, P < 0.01). Furthermore, no significant interaction effects were found between the different layers during the two different years, indicating that the soil CH4 concentration was consistent in the vertical distribution across the different years (Table 2).

Table 1. Soil CH4 concentration profiles (unit) across all treatments and all depths over 2013–2015 growing seasons.

| CH4 concentration (μL L−1) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice season |

Wheat season |

|||

| 2013–2014 | 2014–2015 | 2013–2014 | 2014–2015 | |

| Treatment | ||||

| N0B0 | 5.13 ± 0.82*,§ | 4.85 ± 0.57*,§ | 2.16 ± 0.50 | 1.47 ± 0.10 |

| N1B0 | 18.53 ± 1.91 | 24.87 ± 3.35 | 2.02 ± 0.45 | 1.55 ± 0.18 |

| N0B1 | 6.90 ± 0.51 | 5.32 ± 0.89 | 2.46 ± 0.19 | 1.70 ± 0.15 |

| N1B1 | 15.66 ± 3.38 | 18.65 ± 2.46 | 1.74 ± 0.25 | 1.39 ± 0.03 |

| N1B2 | 13.60 ± 1.32 | 14.81 ± 3.94 | 2.12 ± 0.19 | 1.53 ± 0.13 |

| Soil depth | ||||

| 7 cm | 16.65 ± 2.84¶ | 19.97 ± 5.56¶ | 1.81 ± 0.27¶ | 1.55 ± 0.14 |

| 15 cm | 12.80 ± 1.17 | 13.13 ± 2.94 | 2.16 ± 0.22 | 1.46 ± 0.07 |

| 30 cm | 9.50 ± 1.78 | 12.18 ± 3.46 | 2.12 ± 0.35 | 1.50 ± 0.13 |

| 50 cm | 8.91 ± 1.02 | 9.51 ± 3.74 | 2.32 ± 0.55 | 1.61 ± 0.24 |

B0, B1 and B2 represent biochar applied at the rates of 0, 20 and 40 t ha−1, respectively; N0 and N1 represent N fertilizer applied at the rates of 0 and 250 kg N ha−1 crop−1, respectively.

Data are Means ± SD.

*Indicates significant interaction between treatment and soil depth.

§Indicates significant difference among treatments across all depths.

¶Indicates significant difference among soil depths across all treatments.

Table 2. Results of linear mixed effect models for wheat and rice seasons with the treatments (T), depths (D), and years (Y) as fixed effects and plot as random effects.

| Crop season | Response variable | CH4 concentration (μL L−1) |

CH4 diffusive efflux (mg C m−2 h−1) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| df | F-value | P-value | df | F-value | P-value | ||

| Wheat season | T | 4 | 2.885 | 0.079 | 4 | 0.594 | 0.668 |

| D | 3 | 2.463 | 0.070 | 3 | 42.298 | 0.000 | |

| Y | 1 | 59.017 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.045 | 0.833 | |

| T × D | 12 | 1.322 | 0.226 | 12 | 2.126 | 0.024 | |

| T × Y | 4 | 0.973 | 0.428 | 4 | 0.444 | 0.777 | |

| D × Y | 3 | 2.026 | 0.118 | 3 | 2.450 | 0.070 | |

| T × D × Y | 12 | 0.616 | 0.822 | 12 | 1.214 | 0.289 | |

| Rice season | T | 4 | 41.148 | 0.000 | 4 | 9.023 | 0.000 |

| D | 3 | 37.013 | 0.000 | 3 | 255.451 | 0.000 | |

| Y | 1 | 7.104 | 0.009 | 1 | 2.941 | 0.090 | |

| T × D | 12 | 7.704 | 0.000 | 12 | 30.069 | 0.000 | |

| T × Y | 4 | 4.494 | 0.003 | 4 | 0.844 | 0.501 | |

| D × Y | 3 | 1.315 | 0.276 | 3 | 11.577 | 0.000 | |

| T × D × Y | 12 | 0.637 | 0.804 | 12 | 2.647 | 0.005 | |

The soil CH4 concentrations for the 2013 and 2014 rice seasons were both considerably influenced by N fertilizer application (Table 1, P < 0.05). Following basal fertilization and topdressing during the two rice seasons, the peak CH4 concentrations of 190.6, 103.4, 100.1 and 94.2 μL L−1 were measured in soil air at depths of 7, 15, 30 and 50 cm, respectively. The largest concentrations were 153.7, 127.4 and 190.6 μg N m−2 h−1 for the N1B0, N1B1 and N1B2 treatments, respectively, which occurred after the second topdressing during the rice season in 2014. Similarly, during the rice seasons of the two years (Fig. 1), the mean soil CH4 concentration in the four soil layers significantly increased with the N fertilizer application in comparison with the N0B0 treatment; however, the growth rate decreased with the increase in soil depth (see Supplementary Table S1, P < 0.05).

As shown in Table 1, no significant difference was observed in the averaged CH4 concentrations across all soil depths between N0B0 and N0B1, and there was also no significant difference between the different soil layers in these two treatments, indicating that no reduction effect from biochar was observed without N fertilization, with the only exception being the 50 cm layer during the rice seasons of 2013. For the rice-growing season in 2013, compared with the N1B0 treatment, the biochar amendment did not significantly affect the CH4 concentration in different depths of the N1B1 treatment, and all the soil CH4 concentrations significantly decreased in the N1B2 by 26.6% (Table 1, P < 0.05). However, unlike 2013, the soil CH4 concentrations during the rice season in 2014 were both significantly decreased in the N1B1 and N1B2 treatments by 25.0% and 40.5% compared with the N1B0 treatment (P < 0.05), with the only exception being the 50 cm layer, which had a similar value as the N1B0 treatment (see Supplementary Table S1). These results suggested that there was significant interaction between different treatments and years in the rice growing stages (Table 2, P < 0.01).

Soil profile CH4 diffusive effluxes in the rice-wheat annual rotation system

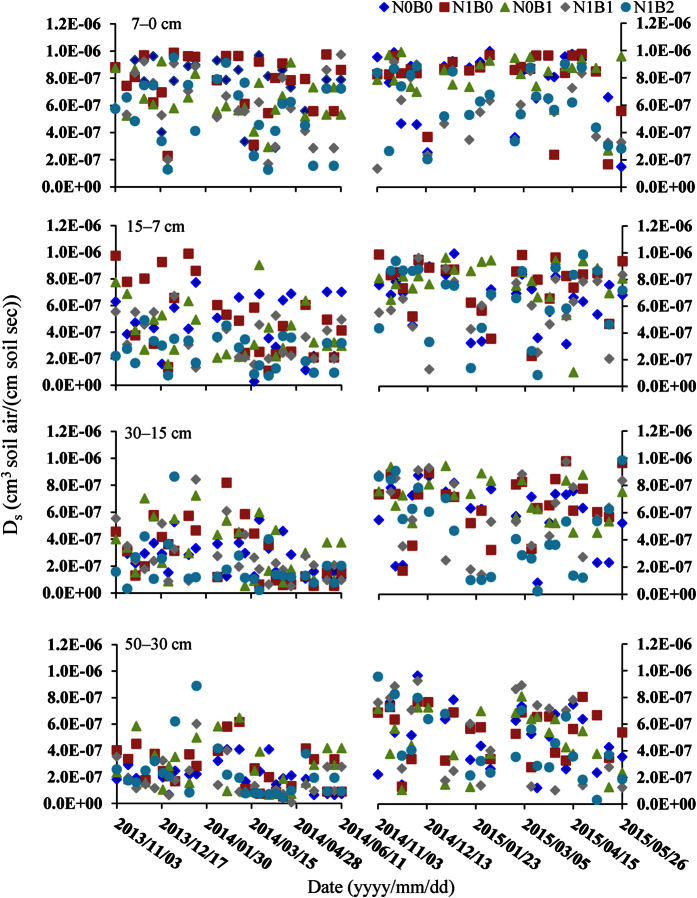

As shown in Fig. 2, the soil CH4 diffusion coefficient did not vary under the water-saturated condition during the flooded rice season as defined by equation (3), but it varied with the soil water-filled pore space (WFPS), which was primarily affected by precipitation over the two wheat seasons. The soil WFPS varied from 30.9% to 89.3% (see Supplementary Fig. S1). The WFPS increased in all treatments with the increase in the soil depth, but there was no significant difference observed among treatments (P > 0.05). The CH4 diffusion coefficients for the N1B0 treatment were higher than the other treatments, which decreased in the following order: N1B0 > N1B1 > N1B2 in the 7 cm depth, and it decreased with increasing depths (Fig. 2). There was no obvious rule for the five treatments in the other soil layers. Although the differences were not significant between the treatments, the differences in the CH4 diffusion coefficients between different soil depths were significant since both the soil moisture content and bulk density increased while the porosity decreased with depths, which all affecting the diffusion coefficient. As shown in Fig. 2, the CH4 diffusion coefficients were higher in 2014 to 2015 and varied from 7.80E-09 to 9.88E-07, and the coefficients from 2013 to 2014 varied from 2.04E-08 to 9.95E-07 cm3 soil air cm−1 soil−1 s−1.

Figure 2. Soil gas diffusion coefficient for soil CH4 in different layers during the rice and wheat seasons from 2013 to 2015.

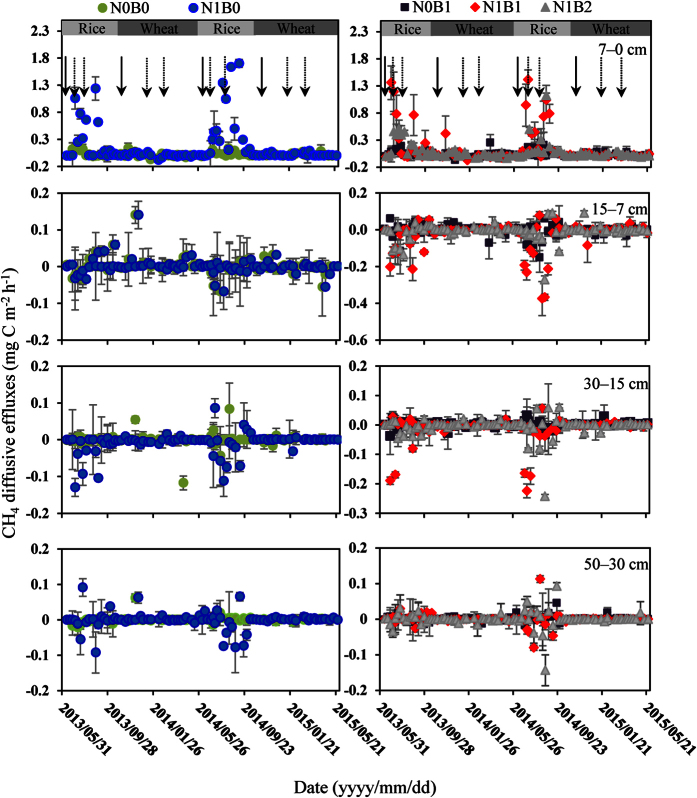

The soil profile CH4 diffusive effluxes were calculated from the gas concentration profiles according to equations (2, 3, 4, 5). As shown in Table 3, no significant differences (P > 0.05) were recorded between the CH4 diffusive effluxes in the five treatments during the wheat seasons, and the mean values were low throughout the study. Thus, we primarily analyzed the change in CH4 diffusive efflux during the two rice seasons. The highest diffusive effluxes were all recorded at a depth of 7–0 cm averaged across all treatments, which showed 139.9 and 208.2 μg C m−2 h−1 during the rice seasons of 2013 and 2014, respectively. However, the diffusive effluxes were mostly negative in the deeper soil layers (Table 3). The highest diffusive influx was less than −24.8 and −52.2 μg Cm−2 h−1, which were recorded at a depth of 15–7 cm averaged across all treatments during the rice seasons of 2013 and 2014, respectively. Significant interactions were found between different depths and years of CH4 diffusive effluxes (Table 2, P < 0.001). Subsequently, the CH4 diffusive efflux values were found between the adjacent soil layers, which increased from positive to negative with the increase in soil depth. This finding indicated that the top 7-cm layer in rice paddy soils was the primary source of CH4 generation, and the deeper soil layers acted as the sink (Table 2).

Table 3. The diffusive effluxes and surface emission fluxes of CH4 (unit) across all treatments and all depths over 2013–2015 growing seasons.

| Treatment | CH4 fluxes (μg C m−2h−1) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice season |

Wheat season |

|||||||

| 2013–2014 |

2014–2015 |

2013–2014 |

2014–2015 |

|||||

| Means | Surface emission fluxes | Means | Surface emission fluxes | Means | Surface emission fluxes | Means | Surface emission fluxes | |

| N0B0 | 7.8 ± 16.7*,§ | 1059.3 ± 36.4 | 9.5 ± 21.4*,§ | 334.3 ± 49.9 | 4.4 ± 6.9* | 159.3 ± 12.3 | 4.0 ± 8.8 | 141.2 ± 46.8 |

| N1B0 | 40.6 ± 132.4 | 1056.6 ± 31.2 | 70.2 ± 242.4 | 553.8 ± 138.4 | 3.8 ± 3.9 | 160.4 ± 17.1 | 6.4 ± 8.6 | 160.2 ± 66.3 |

| N0B1 | 13.3 ± 27.8 | 2325.4 ± 69.7 | 11.4 ± 30.9 | 1497.9 ± 68.1 | 7.3 ± 14.6 | 176.8 ± 13.9 | 5.6 ± 11.5 | 120.0 ± 23.5 |

| N1B1 | 38.0 ± 130.5 | 1859.5 ± 70.5 | 52.6 ± 173.2 | 1367.3 ± 83.0 | 3.8 ± 8.8 | 173.2 ± 10.1 | 3.3 ± 8.2 | 146.5 ± 13.3 |

| N1B2 | 29.6 ± 77.7 | 1424.2 ± 27.1 | 37.4 ± 226.4 | 1119.9 ± 63.3 | 4.1 ± 8.0 | 143.3 ± 16.2 | 5.8 ± 12.6 | 109.6 ± 90.4 |

| Soil depth | Means | |||||||

| 0–7 cm | 139.9 ± 95.4¶ | 208.2 ± 165.2¶ | 14.5 ± 9.9¶ | 19.6 ± 3.8¶ | ||||

| 7–15 cm | −24.8 ± 29.0 | −52.2 ± 43.5 | 4.6 ± 6.1 | −0.3 ± 4.2 | ||||

| 15–30 cm | −11.2 ± 9.8 | −3.5 ± 11.9 | −0.4 ± 1.9 | 0.1 ± 1.8 | ||||

| 30–50 cm | −0.6 ± 2.0 | −7.5 ± 11.0 | 0.1 ± 1.8 | 0.7 ± 0.9 | ||||

B0, B1 and B2 represent biochar applied at the rates of 0, 20 and 40 t ha−1, respectively; N0 and N1 represent N fertilizer applied at the rates of 0 and 250 kg N ha−1 crop−1, respectively.

Data are Means ± SD.

*Indicates significant interaction between treatment and soil depth.

§Indicates significant difference among treatments across all depths.

¶Indicates significant difference among soil depths across all treatments.

The results indicated that the soil CH4 diffusive effluxes were significantly affected by the treatments (Table 2, P < 0.001). Basal fertilization and topdressing result in soil CH4 diffusive efflux, which increased significantly during the rice-growing stages (Fig. 3). Relative to the N0B0 treatment, the CH4 emission and diffusive efflux in the N1B0 treatment significantly increased from 1059.3 to 2325.4 and 7.8 to 40.6 μg C m−2 h−1 in 2013, 334.3 to 1497.9 and 9.5 to 70.2 μg C m−2 h−1 in 2014 (Table 3). However, the levels significantly decreased from 2.7 to −50.9 μg C m−2 h−1 and −7.0 to −111.5 μg C m−2 h−1 in 15–7 cm, and they displayed no obvious difference in the other layers (see Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 3. Seasonal dynamics of CH4 diffusive effluxes at different soil depths in the rice-wheat annual rotation system, with different N and biochar additions.

The error bars show the standard deviations (n = 3). The solid and dashed arrows indicate basal fertilization and top-dressing, respectively.

Biochar amendments could reduce the CH4 diffusive efflux that occurred from the 7 cm depth to the surface 0 cm to a certain extent, under N fertilizer application. In comparison with the N1B0 treatment, the means that averaged all depths for each treatments were decreased in N1B1 and N1B2 treatments (Table 3), the mean emission fluxes of the surface soil respectively decreased from 2325.4 to 1859.5 and 1424.2 mg C m−2 h−1 and 1497.9 to 1367.3 and 1119.9 μg C m−2 h−1 in the N1B1 and N1B2 treatment of the rice stages in 2013 and 2014, the reducing emission of CH4 only were significant in N1B2 treatments. Be consisted with the result of the mean emission fluxes, the mean soil CH4 diffusive effluxes to a depth of 7 cm were decreased by 2.95% and 38.82% in the N1B1 treatment, and they significantly decreased by 27.80% and 51.64% in the N1B2 (P < 0.05) of the rice seasons in 2013 and 2014, respectively (see Supplementary Table S2). By contrast, there was no difference between the CH4 emission and diffusive efflux of the N0B1 and N0B0 treatments, indicating that the biochar amendment had no effect on the CH4 diffusion without the N fertilizer application in the annual rice-wheat rotations. Similarly, in 2013 and 2014, there was no obviously difference between the N1B0 and N1B1 treatments, as shown in Table 3. Thus, we can deduce that the amendment of 20 t ha−1 biochar with N fertilization has no significant effect on reducing the diffusive effluxes of CH4 in the soil profile.

Comparative study of soil CH4 emission and diffusion efflux

The top 7-cm soil depth performed as the main source for the CH4 production while the diffusion effluxes in other layers all were low or negative (Tables 1 and 3). Thus the CH4 diffusion in the 7–0 cm soil depth was selected to compare with the CH4 emissions of soil surface.

Similar pattern were shown in 2013–2014 and 2014–2015, that the emission fluxes were nearly 2.5 to 38.8 times significantly higher than the diffusion effluxes (Table 3, P < 0.05). Regression analysis results showed that under the condition of conventional N fertilization, there was a significant positive correlation between the CH4 diffusive effluxes in the 7–0 cm soil layer and the CH4 emission fluxes. While the diffusive effluxes in the deeper soil layers showed significant negative correlation with the emission efflux (Table 4, P < 0.05). The above results indicated that the top 7-cm layer in rice paddy soils was the primary source of CH4 production and oxidation, while the deeper soil layers performed as the sink. Although there obtained the certain correlation between the CH4 diffusive effluxes between the CH4 emission fluxes, but there were significant differences between the values of them (Table 3 and see Supplementary Table S2).

Table 4. Correlation coefficients between CH4 emissions and diffusive effluxes within the soil profiles among the different treatments from the rice-wheat annual rotations.

| Year | Diffusive flux | Treatment |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N0B0 | N0B1 | N1B0 | N1B1 | N1B2 | ||

| 2013–2014 | 7–0 | 0.207 | 0.048 | 0.299* | 0.347* | 0.501** |

| 15–7 | −0.151 | 0.209 | 0.144 | −0.404** | −0.519** | |

| 30–15 | −0.050 | 0.244 | 0.050 | −0.111 | −0.141 | |

| 50–30 | −0.318* | 0.110 | −0.053 | −0.353* | −0.119 | |

| 2014–2015 | 7–0 | 0.124 | 0.228 | 0.291* | 0.416** | 0.404** |

| 15–7 | −0.111 | −0.093 | −0.145 | −0.506** | −0.346* | |

| 30–15 | 0.105 | −0.049 | 0.117 | 0.040 | −0.111 | |

| 50–30 | 0.133 | −0.116 | −0.085 | −0.178 | −0.072 | |

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ns not significant.

Discussion

The soil CH4 concentrations were considerably influenced by N applications that resulted in peaks throughout the soil profile (Fig. 1), and the concentrations performed higher in the upper (7 cm and 15 cm) layers than in the deeper ones (30 cm and 50 cm) during the rice seasons (Table 1). The probable reason might be the absence of substantial amounts of methanogens in the deeper soil layers33. Conrad et al.34 explained that the decrease in CH4 below the oxic surface layers was likely related to the presence of rice roots in these soil layers, which provided a favorable environment for methanotrophs and allowed for the release of CH4 by plant vascular transport. In our study, significant interactions between the treatments and years were only found in the soil CH4 concentrations profiles during the rice growing stages (Table 2, P < 0.05). Given that the surface water was maintained continuously by irrigation at the rice-growing stage, the water regime in the field was not considered to influence the yearly variation in the CH4 emission35. The microbial and root metabolic activity were inhibited under the low soil water content during the wheat season, while soil oxygen would be depleted when pore spaces were saturated with water under the very high soil water content36, that can reduce the oxidation of CH4. Watanabe et al.24 explained that the temperature is considered the most influential factor when the fertilizer application and other cultivation methods are constant. There was only a small amount of difference between the soil temperatures from 2013–2014 and 2014–2015. Thus, we further hypothesized that the higher concentrations of CH4 in 2014 might be related to the fact that the surface soil contained more organic material and microorganisms following more cultivation and agricultural management36,37.

The nitrogen application significantly increased the CH4 concentrations from all the soil layers in our study (Table 1, P < 0.01), primarily because the N fertilizer application can stimulate CH4 production by increasing the growth of rice plants and root exudation, which can promote the carbon supply for methanogens38 in soil layers to provide an enabling environment for CH4 generation. Conrad et al.10 proposed that a favorable habitat for the growth of methanogens and sufficient substrates are prerequisites for CH4 generation. Wang et al.5 also showed that the observed increase in CH4 production might be related to the fact that N fertilizer can decrease the soil C:N ratio and promote the activity of soil microorganisms. The increased CH4 concentrations associated with N fertilization are likely ascribed to the fertilizer-induced reduction in soil CH4 oxidation in different soil layers39. As a result of the increase in the soil NH4+-N concentration after the application of N fertilizer, because of the competition effect, a higher concentration of NH4+-N may reduce the probability of CH4 oxidization by methanotrophs40. Mohanty et al.41 hypothesized that NH4+-N is a competitive inhibitor of CH4 monoxygenase. The research of Wu et al.42 demonstrated that N fertilizers can directly alleviate N limitation to methanogens especially near the rhizosphere where concentration of ammonia is lower due to rice plants uptake.

Biochar amendments of 20 t ha−1 and 40 t ha−1 with N fertilization reduced the soil CH4 concentration during the rice-wheat rotation systems from 2013 to 2015 (Table 1, Fig. 1, P < 0.05), significantly at the 0–15 cm depth (see Supplementary Table S1, P < 0.05), which is consistent with the study by Scheer et al.31 in which the biochar amendment can reduce the generation and emission of soil CH4. Han et al.43 even found that there was an increase in CH4 uptake in soil amended with biochar. However, elevated CH4 production and emission following biochar amendments in soil have been shown in previous studies30,32. The contrasting observations in our study may be explained by the different soil types and site conditions as well as the properties of biochar having a different effect on the CH4 emissions of soil. According to Van Zwieten et al.44, the labile organic C added by the biochar can provide abundant available substrates for methanogens and create locally anaerobic microsites in soil that favors CH4 production. In addition, biochar can increase the air permeability of soil with a greater specific surface area27, which was more beneficial to the growth of the methanotrophs. Feng et al.45 found that biochar can increase the abundance of methanotrophs in the paddy soil and reduce the ratios of methanogens to methanotrophs. While Han et al.43 reported that the decreased CH4 release was primarily attributable to the decreased activity of methanogens along with the increased CH4 oxidation activity, Silber et al.46 showed that biochar can also increase the soil cation exchange capacity (CEC) to improve the soil pH, which can further inhibit the activity of methanogens. Yu et al.47 reported that soil moisture can affect CH4 emissions by directly influencing methanogenic and methanotrophic activities and by indirect effects through changes in soil aeration and redox potential. The CH4 uptake appeared to be very sensitive to the soil moisture content at all depths48 since soil water content and soil electrical conductivity (EC) were the most influential factors driving the changes in the microbial community during agricultural practices38. These findings indicated that the different effects of biochar on the CH4 concentration in the treatment amended with biochar between different seasons and different layers in our study may be related to the different moisture levels.

In this study, the application of N fertilizer with biochar had no significant effect on the soil CH4 concentration during the wheat seasons (Table 1), which might be related to the variety of water contents present during the rice and wheat growing seasons. The environment factors might reduce the biochar effect to some extent.

The emission of CH4 is the combined consequence of soil production, oxidation and diffusion in soil8, and the difference in the CH4 concentrations in different soil profile depths is the primary dynamic mechanism of CH4 emission33. The results of the soil CH4 concentration and diffusive flux (Tables 1 and 3 and Figs 1 and 3) can directly reflect the generation and storage site of CH4 in soil, providing detailed information for research on the source and sink of CH4 in paddy soil.

Because of the high spatial variation in CH4 concentrations, there is a spatial variation in the soil CH4 diffusive efflux in the field under flooded conditions during the rice seasons. As previously described, the soil CH4 concentration patterns varied with the rice and wheat seasons (Fig. 1 and Table 1), affecting the concentration gradient of CH4 in the soil profile, which might be explained by the fact that the soil was under the flooded anaerobic conditions that prevailed in the rice paddy, and CH4 was produced when the organic materials decomposed under oxygen-deprived conditions49. A large portion of the CH4 generated in the soil profile might be oxidized, and it is estimated that more than 50–90% of the CH4 produced belowground is oxidized before reaching the atmosphere34.

The distribution of the soil CH4 concentration and diffusion showed the same dynamic rule during the rice-wheat crop rotations from 2013–2015. As previously described, with only the exception of the soil CH4 diffusive efflux at 7–0 cm during the two rice growing stages, the values of the soil CH4 diffusive efflux during the wheat seasons and the rest of the soil depths were small or negative, and the average soil CH4 concentrations and diffusive effluxes from the 7–0 cm depth were significantly higher than that of the subsoil (Tables 1, 3 and Tables S1 and S2). As a complicated heterogeneous system, the different soil layers have different structural features, and there are differences in their contents of soil organic matter37. With a higher soil organic matter content, the total N and NH4+-N was greater in the soil surface layer than in the deeper depths50,51, and the CH4 concentration was significantly promoted in the surface layer of the paddy field, making the surface soil the primary CH4 generation area. Hütsch et al.40 reported that the topsoil was more conducive to the generation of CH4, because even in an anaerobic state, the lower soil layers had fewer nutrient substrates; thus, the CH4 content might also be relatively lower than that of the topsoil. The vertical distribution of CH4 storage in the soil profile also reflects the distribution rule of soil organic matter decomposition and CH4 diffusion in the soil profile. The significant interaction of the soil CH4 diffusive effluxes between different depths and years (Table 2, P < 0.001) may be related to the different gas diffusion coefficients (Ds) and the soil WFPS in the different depths. The study by Pingintha et al.52 explained that with the lower suction of soil water in the surface soil than in lower depths for agricultural soil, the Ds in the soil decreased with the increase in depth, and thus the gas in the surface soil is more prone to being diffused to the atmosphere, as opposed to the other layers. The CH4 diffusive efflux in shallow soil can directly reflect the CH453 emissions. Similar to the grassland study of Hartmann et al.39, we observed that the soil CH4 concentrations were always decreased with the soil depth, which indicated that the depths below 7 cm in the soil and the soil in the wheat seasons were the net sink for atmospheric CH4 and primarily acted in the absorption of CH4 (Table 3). The average CH4 concentrations increased with the N fertilization application in 2014–2015, which was more obvious than that in 2013–2014. Compared with the N0B0 treatments with less available nutrient substrates, the treatments received the N fertilization and biochar amendment showed more obvious effects in the second year than the first year. The fact that N fertilization would promote the growth of plant38 and then provide the substrates to methanogens34 and play an important role in the transport of CH48 may explain this phenomenon.

High soil CH4 concentrations lead to more accumulation and emissions19. However, in comparison with the field experiments that monitored the CH4 emissions from the same plots in Li et al.54, the emission effluxes of CH4 were clearly higher than the diffusive effluxes that we observed. Although there was a significantly positive correlation between the soil CH4 emission fluxes and diffusive effluxes in 7–0 cm in the treatments with N fertilizer application in rice-wheat crop rotations of 2013–2015, there were no significantly positive correlation in the treatments without N fertilization, nor the other soil layers (Table 4) associated with the low ratios between CH4 diffusion efflux and surface emissions (Table 3). Nitrogen fertilization amendment could significantly increase the production of CH4, correspondingly increased the CH4 diffusion and emission as previously mentioned.

The CH4 diffusive effluxes in the top 7-cm soil layers were significantly lower than the emissions of the surface soil in rice-wheat rotation systems, the values of the CH4 diffusive effluxes in 7–0 cm soil depth being only 2.5 to 28.6% of the surface soil emissions (see Supplementary Table S2). The reason might be due to the facts that the soil CH4 is mainly transported by plants or bubbles other than free diffusion into the atmosphere during rice season with saturated soil moisture condition, and agreed well that the concentration gradient method produced smaller estimates18. While during the wheat season the diffusion was a major transport way of soil gas when the soil moisture contents were low, soil CH4 might easily be oxidized in the aerobic zone of surface layer8. In addition, the position deviation of the observation and the uneven distribution of soil moisture and organic matter were also the possible causes for the difference between surface emission and diffusion21. Similarly, Hendriks et al.55 reported soil CH4 diffusion rates were lower than the CH4 emissions observed by the chamber method in similar paddy fields. The transportation of CH4 emissions from paddy soil into atmosphere is the comprehensive result of production, oxidation and diffusion, while only calculating the CH4 diffusion by concentration gradient method to estimate the CH4 emissions will get the relatively smaller values. However, Dunfield et al.22 found a good correlation between the diffusion calculated by the concentration gradient and the emission measured by the chamber method due to the homogeneous unstructured soil conditions. Therefore use the concentration gradient method to estimate the amount of CH4 diffusion in rice−wheat rotation system cannot completely take place of the observation on soil surface emissions, which needs a further research.

Materials and Methods

Field site and experimental design

A field experiment that involved the monitoring of the emission and diffusion of CH4 in the soil profile was performed in a typical rice paddy in MoLing Town (31°58′ N, 118°48′ E), Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China. The field was cultivated under a crop rotation system of rice in summer (June to October) and wheat in winter (November to May). The site is characterized by a subtropical humid monsoon climate with a mean annual air temperature of 15.7 and 16.9 °C and precipitation of 1,050.2 and 1,072.4 mm for two years. The field soil is classified as Irragric Anthrosols56 with a silty clay loam texture consisting of 14% clay, 6% sand, and 80% silt. The physicochemical properties of the soil in the 0–50 cm horizon are shown in Supplementary Table S3. The soil pH was higher in the deeper (7.01 ± 0.15 in 15–30 cm and 6.72 ± 0.20 in 30–50 cm) layers than in the upper ones (5.91 ± 0.16 in 0–7 cm and 6.53 ± 0.12 in 7–15 cm); and the surface soil layers have the highest organic carbon, 16.23 ± 0.83 g C kg−1; total N, 1.43 ± 0.07 g kg−1; and CEC (cation exchange capacity), 28.60 ± 0.11 cmol kg−1, while the soil bulk density increased with the soil depth increased, being 1.41 ± 0.01 g cm−3 in the 30–50 cm soil layers. The daily mean air temperatures and precipitation during the study period from June 19, 2013, to May 31, 2015, are given in Supplementary Fig. S2.

Five treatments were established in three replicates in a completely random design as follows: N0B0, N0B1, N1B0, N1B1, and N1B2. The same 15 field plots were used for all the two rice-wheat rotations in both years. In brief, biochar was added to the soil at a rate of 0 (as the control), 20 and 40 t ha−1 (which were coded as B0, B1, and B2, respectively), and N fertilizer (urea) was applied at two rates of 0 (N0) and 250 kg N ha−1 crop−1 (N1). Each plot had an area of 5 m × 4 m. In each treatment, the biochar, which was originally in particulate form, was added once to the paddy fields in June 2012 and was incorporated into the soil by plowing to a depth of 50 cm. The biochar used in this experiment was produced from wheat straw at a temperature of approximately 350–550 °C by a local pyrolysis plant in a vertical kiln constructed from refractory bricks at Sanli New Energy Company, Henan, China. The biochar had a total C content of 467 g kg−1, a total N content of 5.6 g kg−1, a pH of 9.4 (1:1.25 H2O), an ash content of 208 g kg−1 and a cation exchange capacity of 24.1 cmol kg−1.

Field plot management

The field management including the crop species, fertilizer application rates and methods, tillage, irrigation, pesticide and weed control were performed in accordance with local practices (Supplementary Table S4). No irrigation was performed during the wheat season. In treatments receiving N fertilization, urea was applied at a rate of 250 kg N ha−1 and split into a 4:3:3 ratio of basal fertilizer and two topdressings for both the rice and wheat crops. The topdressing was applied at the tillering and panicle stages of the rice crop and at the seedling establishment and elongation stages of the wheat crop. Both calcium superphosphate and potassium chloride were applied as basal fertilizers at rates of 60 kg P2O5 ha−1 crop−1 and 120 kg K2O ha−1 crop−1 during both the rice and wheat seasons. Rice was transplanted on June 19, 2013 and June 10, 2014 and harvested on October 18, 2013 and October 25, 2014, respectively. Winter wheat was directly sown on November 3, 2013 and November 13, 2014 and then harvested on May 28, 2014 and May 26, 2015, respectively.

Gas sample collection and measurement

Observations of the CH4 soil profile were conducted during the rice-wheat growing season from June 13, 2013, to May 31, 2015. The monitoring of CH4 emission fluxes were performed using a static chamber method and we constructed soil gas collection tubes to obtain samples from different soil depths (the samples were centered at 0, 7, 15, 30 and 50 cm) at a single site19. There was one sampling column collecting soil gas at different depths at the same position and one sampling chamber on the ground in each plot. The 0–15 cm soil layer was the plough layer, and the redox mainly happened in this layer; 15–30 cm soil layer was the plow pan; 30–50 cm soil layer was the saturated soil layer. The gas sampler was installed along the same vertical section of the soil profile. Every sampler consists of four independent chambers, which represent the CH4 concentrations at depths of 7, 15, 30, and 50 cm (see Supplementary Fig. S3). The internal headspace volume for each sampling unit was approximately 48 cm3. The structure of the samplers consisted of long, 50-cm polyvinyl chloride (PVC) tubes with four individual units (the inside diameter was 4.0 cm and the height was 5.0 cm) connected together, and each unit contained eight uniformly distributed holes that were 1.2 cm in diameter each and covered by two layers of 80-mesh nylon for soil gas equilibration from the surrounding soil layers. For each gas equilibration unit, silicone tubing (inner diameter = 4.76 mm; outer diameter = 7.62 mm) was fixed inside the sampler and penetrated out of the PVC tube surface. The ends of the four stretching silicone tubes were fitted with three-way stopcocks that allowed the sampling of the subsurface gases above the soil surface. A PVC plate was installed between each individual unit to ensure isolation. Soil gas samples were collected by first drawing 5 mL of gas to purge the volume of the spaghetti tubing and then drawing a 20 mL sample using a syringe. The valves were kept closed between samplings to ensure that subsurface gas samplers were not contaminated with atmospheric air. The CH4 sampling tubes were left in place for the whole two years.

The gas samples were analyzed for CH4 concentrations using a gas chromatograph (Agilent 7890 A Shanghai, China) equipped with a hydrogen flame ionization detector (FID). The carrier gas was nitrogen, and it had a flow rate of 40 mL min−1. The temperatures of the oven and the FID were 50 and 300 °C, respectively. The mean concentrations and soil diffusive fluxes of CH4 for the rice and wheat were all calculated as the average of all the measured concentrations, and fluxes that were weighted by the two measurements at each sampling point divided by the time interval. The CH4 fluxes were calculated using the linear increases in gas concentration with time. The concentration of CH4 at 0 cm was used as the mean surface air sample, which close to the background atmospheric value at the sampling time (Fig. 1), sampled from the surface ground in each plot.

All analyses of soil chemical properties were based on the standard methods for soil analyses described by Sparks et al.57. We monitored only the soil moisture contents at depths of 7, 15, 30, and 50 cm during the wheat season because the soil moisture content did not vary during the flooded rice season under the water-saturated condition. The water content was converted to water-filled pore space (WFPS) with the following equation58:

|

here, the total soil porosity = [1− (soil bulk density (g cm−3)/2.65)] with an assumed soil particle density of 2.65 (g cm−3). The soil bulk density at different depths was determined using the cutting ring method59.

Data calculation

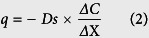

Soil CH4 concentration data were used to estimate the diffusive efflux of CH4 within different soil depths with Fick’s Law as follows:

|

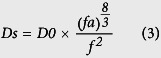

where q is the diffusive efflux of CH4 (ng cm−2 s−1), Ds is the soil gas diffusion coefficient of CH4 in the soil (cm3 soil air cm−1 soil s−1), C is the concentration of CH4 (ng m−3), ΔC is the concentration difference between two depths, X is the vertical position (cm) (i.e., 0, −7, −15, −30 and −50 cm according to the soil stratification and redox conditions in the paddy field), ΔX is the difference in depths between two adjacent soil layers, and ΔC/ΔX is the vertical soil CH4 gradient (ng cm−3 cm−1). The CH4 diffusive efflux is the rate of CH4 efflux from the lower designated soil layer to the upper soil layer (i.e., 7–0, 15–7, 30–15 and 50–30 cm). A positive value for the diffusive efflux represents CH4 efflux, which indicates CH4 diffusing to the upper soil layer, and negative values represent CH4 diffusing to the lower soil layer, as expressed as the CH4 diffusive influx. The effective diffusion coefficient Ds of CH4 in the soil is lower than that in the atmosphere and can be expressed as follows:

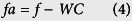

|

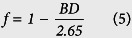

|

|

where D0 is the diffusion coefficient of the atmosphere (cm2 s−1) and is determined as 0.156 cm2 s−1 for CH4 at T = 293.2 K and P = 101.3 kPa60. The fa and f are the air-filled porosity (cm3 cm−3) and total porosity of the soil (cm3 cm−3), respectively. WC is the soil volumetric moisture content (cm3 cm−3), and BD is the soil bulk density (g cm−3), which was assumed to be constant for each corresponding soil layer, although some variations may have occurred during crop rotation. Depending on the gas and chemistry of the soil solution, the amount of gas stored in the aqueous phase may be neglected. Although there may have been some variations in the actual bulk density among the replications, treatments and crops rotations (±0.1 g cm−3), they were not expected to be significant relative to the changes in CH4 diffusive efflux.

Statistical analysis

To examine differences in the mean soil CH4 concentrations and diffusive effluxes data among different treatments, years, depths were subjected to linear mixed-effects models (LMMs). The data for the wheat and rice were analyzed separately. Models included treatment (N0B0, N0B1, N1B0, N1B1, N1B2), year (2013–2014, or 2014–2015) and depth (0–7, 7–15, 15–30, 30–50 cm) as fixed effects and plot was included as a random effect. The depth was treated as a multilevel factor. We validated the use of LMMs with restricted maximum likelihood estimation method (REML) based on the normalized scores of standardized residual deviance of response variables for the soil CH4 concentrations and diffusive effluxes. Statistical analyses were performed with the statistical package R 3.0.0 (using the ‘lme4’ package) with a significance level of alpha = 0.05 for LMMs (R Development Core Team 2013).

Before the analysis, the data from each depth interval were averaged within each ring, the ring refers to the individual units (the inside diameter was 4.0 cm and the height was 5.0 cm, see Supplementary Fig. S3) and each ring was treated as a statistical replicate for the treatments. Simple and multiple linear and nonlinear regression analyses were used to examine the relationships between the CH4 fluxes measured using the static chamber and gas concentration gradient methods. The multiple comparisons among the means were done based on the pooled errors from the analyses summarised in Table 2, performed with the statistical package R 3.0.0 (using the ‘lme4’ package). We define an emission peak as a peak that was significantly higher than the previous and following effluxes. Normal distribution and variance uniformity were checked, and all the data were consistent with the variance uniformity (P > 0.05) within each group. The results are presented as the means and standard deviation (mean ± SD, n = 3).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Xu, X. et al. Effects of nitrogen and biochar amendment on soil methane concentration profiles and diffusion in a rice-wheat annual rotation system. Sci. Rep. 6, 38688; doi: 10.1038/srep38688 (2016).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We sincerely appreciate three anonymous reviewers for their critical and valuable comments to help improve this manuscript. This work was jointly supported by the National Science Foundation of China (41471192), Special Fund for Agro-Scientific Research in the Public Interest (201503106) and the Ministry of Science and Technology (2013BAD11B01).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions X.X., Z.W., Y.D. and Z.Z. participated in field sampling and measurements; Z.X. and X.X. wrote the manuscript and carried out data analysis; Z.X. supervised the project. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- IPCC. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis in Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Stocker T. F. et al.) 710–716 (Cambridge and New York, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Yan X., Akiyama H., Yagi K. & Akimoto H. Global estimations of the inventory and mitigation potential of methane emissions from rice cultivation conducted using the 2006 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Guidelines. Glob Biogeochem Cycles 23, GB003299 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. et al. Seasonal and interannual variations of carbon exchange over a rice-wheat rotation system on the North China Plain. Adv Atmos Sci 32, 1365–1380 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Guo J. H. et al. Significant acidification in major Chinese croplands. Science 327, 1008–1010 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Delaune R. D., Lindau C. W. & Patrick W. H. Jr. Methane production from anaerobic soil amended with rice straw and nitrogen fertilizers. Fert Res 33, 115–121 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Asai H. et al. Biochar amendment techniques for upland rice production in Northern Laos: 1. Soil physical properties, leaf SPAD and grain yield. Field Crop Res 111, 81–84 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Ebenstein A., Zhang J., McMillan M. S. & Chen K. Chemical fertilizer and migration in China. NBER Working Paper. w17245 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Le Mer J. & Roger P. Production, oxidation, emission and consumption of methane by soils: a review. Eur J Soil Biol 37, 25–50 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. et al. A novel pathway of direct methane production and emission by eukaryotes including plants, animals and fungi: an overview. Atmos Environ 115, 26–35 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Conrad R. Microbial ecology of methanogens and methanotrophs (eds Donald L. S.). 96, 1–63 (Advances in agronomy Academic Press, 2007).

- Yan Y., Dong X. & Li J. Experimental study of methane diffusion in soil for an underground gas pipe leak. J Nat Gas Sci Eng 27, 82–89 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Liu D. Y., Ding W. X., Jia Z. J. & Cai Z. C. Relation between methanogenic archaea and methane production potential in selected natural wetland ecosystems across China. Biogeosciences 8, 329–338 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Yagi K., Kumagai K., Tsuruta H. & Minami K. Emission, production, and oxidation of methane in a Japanese rice paddy field (eds Lal R. et al.). Soil management and greenhouse effect. 231–243 (CRC/Lewis Boca Raton, 1995). [Google Scholar]

- Mitra S., Wassmann R., Jain M. C. & Pathak H. Properties of rice soils affecting methane production potentials: 2. Differences in topsoil and subsoil. Nutr Cycl Agroecosyst 64, 183–191 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Kammann C., Hepp S., Lenhart K. & Müller C. Stimulation of methane consumption by endogenous CH4 production in aerobic grassland soil. Soil Biol Biochem 41, 622–629 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Wolf B. et al. Applicability of the soil gradient method for estimating soil-atmosphere CO2, CH4, and N2O fluxes for steppe soils in Inner Mongolia. J Plant Nutr Soil Sci 174, 359–372 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Z. Q., Xing G. X. & Zhu Z. L. Nitrous oxide and methane emissions as affected by water, soil and nitrogen. Pedosphere 17, 146–155 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Maier M. & Schack-Kirchner H. Using the gradient method to determine soil gas flux: A review. Agr Forest Meteorol 192, 78–95 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Yang B. et al. Effects of elevated atmospheric CO2 concentration and temperature on the soil profile methane distribution and diffusion in rice–wheat rotation system. J Environ Sci 32, 62–71 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. et al. Assessment of winter fluxes of CO2 and CH4 in boreal forest soils of central Alaska estimated by the profile method and the chamber method: a diagnosis of methane emission and implications for the regional carbon budget. Tellus B 59, 223–233 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Billings S. A., Richter D. D. & Yarie J. Sensitivity of soil methane fluxes to reduced precipitation in boreal forest soils. Soil Biol Biochem 32 10, 1431–1441 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Dunfield P. F., Topp E., Archambault C. & Knowles R. Effect of nitrogen fertilizers and moisture content on CH4 and N2O fluxes in a humisol: measurements in the field and intact soil cores. Biogeochemistry 29, 199–222 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Cai Z. et al. Methane and nitrous oxide emissions from rice paddy fields as affected by nitrogen fertilisers and water management. Plant Soil 196, 7–14 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe A., Yamada H. & Kimura M. Analysis of temperature effects on seasonal and interannual variation in CH4 emission from rice-planted pots. Agric Ecosyst Enviro 105, 439–443 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Zhang W., Zheng X., Li J. & Yu Y. Modeling methane emission from rice paddies with various agricultural practices. J Geophys Res: Atmos. 109(D8) (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Ameloot N., Graber E. R., Verheijen F. G. & De Neve S. Interactions between biochar stability and soil organisms: review and research needs. Eur J Soil Sci 64, 379–390 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B., Lehmann J. & Zech W. Ameliorating physical and chemical properties of highly weathered soils in the tropics with charcoal–a review. Biol Fert Soil 35, 219–230 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann J. & Rondon M. Bio-char soil management on highly weathered soils in the humid tropics. Biological approaches to sustainable soil systems. (eds Uphoff N. et al.) Ch. 36, 517–530 (CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, 2006).

- Kookana R. S. The role of biochar in modifying the environmental fate, bioavailability, and efficacy of pesticides in soils: a review. Soil Res 48, 627–637 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang A. et al. Effect of biochar amendment on yield and methane and nitrous oxide emissions from a rice paddy from Tai Lake plain, China. Agric Ecosyst Enviro 139, 469–475 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Scheer C., Grace P. R., Rowlings D. W., Kimber S. & Van Zwieten L. Effect of biochar amendment on the soil-atmosphere exchange of greenhouse gases from an intensive subtropical pasture in northern New South Wales, Australia. Plant Soil 345, 47–58 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Knoblauch C., Maarifat A. A., Pfeiffer E. M. & Haefele S. M. Degradability of black carbon and its impact on trace gas fluxes and carbon turnover in paddy soils. Soil Biol Biochem 43, 1768–1778 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Stiehl-Braun P. A., Hartmann A. A., Kandeler E., Buchmann N. I. N. A. & Niklaus P. A. Interactive effects of drought and N fertilization on the spatial distribution of methane assimilation in grassland soils. Glob Chang Biol 17, 2629–2639 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Conrad R. & Rothfuss F. Methane oxidation in the soil surface layer of a flooded rice field and the effect of ammonium. Biol Fert Soil 12, 28–32 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- Nugroho S. G., Lumbanraja J., Suprapto H., Haraguchi H. & Kimura M. Three-year measurement of methane emission from an Indonesian paddy field. Plant Soil 181, 287–293 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Li C. H., Tang L. S., Jia Z. J. & Li Y. Profile Changes in the Soil Microbial Community When Desert Becomes Oasis. PloS one 10, e0139626 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syswerda S. P., Corbin A. T., Mokma D. L., Kravchenko A. N. & Robertson G. P. Agricultural management and soil carbon storage in surface vs. deep layers. Soil Sci Soc Am J 75, 92–101 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Schimel J. Global change: rice, microbes and methane. Nature 403, 375–377 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann A. A., Buchmann N. & Niklaus P. A. A study of soil methane sink regulation in two grasslands exposed to drought and N fertilization. Plant Soil 342, 265–275 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Hütsch B. W. Methane oxidation in soils of two long-term fertilization experiments in Germany. Soil Biol Biochem 28, 773–782 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Mohanty S. R., Bodelier P. L., Floris V. & Conrad R. Differential effects of nitrogenous fertilizers on methane-consuming microbes in rice field and forest soils. Appl Environ Microbiol 72, 1346–1354 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L., Ma K., Li Q., Ke X. & Lu Y. Composition of archaeal community in a paddy field as affected by rice cultivar and N fertilizer. Microbial ecology 58, 819–826 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X. et al. Mitigating methane emission from paddy soil with rice-straw biochar amendment under projected climate change. Sci Rep-UK 6, 24731 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Zwieten L. et al. Biochar and emission of non-CO2 greenhouse gases from soil. In: Biochar for environmental management: science and technology (eds Lehmann J., Joseph S.). pp 227–249 (Earthscan, London, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y., Xu Y., Yu Y., Xie Z. & Lin X. Mechanisms of biochar decreasing methane emission from Chinese paddy soils. Soil Biol Biochem 46 80–88 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Silber A., Levkovitch I. & Graber E. R. pH-dependent mineral release and surface properties of cornstraw biochar: agronomic implications. Environ Sci Technol 44, 9318–9323 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L., Tang J., Zhang R., Wu Q. & Gong M. Effects of biochar application on soil methane emission at different soil moisture levels. Biol Fert Soil 49, 119–128 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Mosier A., Schimel D., Valentine D., Bronson K. & Parton W. Methane and nitrous oxide fluxes in native, fertilized and cultivated grasslands. Nature 350, 330–332 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- Sass R. L., Fisher F. M., Ding A. & Huang Y. Exchange of methane from rice fields: national, regional, and global budgets. J Geophys Res 104, 26943–26951 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C., Liu G., Xue S. & Sun C. Soil organic carbon and total nitrogen storage as affected by land use in a small watershed of the Loess Plateau, China. Eur J Soil Biol 54, 16–24 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Z. Q., Khalil M. A. K., Xing G., Shearer M. J. & Butenhoff C. Isotopic signatures and concentration profiles of nitrous oxide in a rice-based ecosystem during the drained crop-growing season. J Geophys Res 114, JG000827 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Pingintha N., Leclerc M. Y., BEASLEY J. Jr., Zhang G. & Senthong C. Assessment of the soil CO2 gradient method for soil CO2 efflux measurements: comparison of six models in the calculation of the relative gas diffusion coefficient. Tellus B 62, 47–58 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Maenhout P., Sleutel S., Ameloot N. & De Neve S. Influence of biochar on soil pore structure and denitrification. Egu General Assembly 16, 2632 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Zhou Z. Q., Pan X. J. & Xiong Z. Q. Effects of biochar on N2O and CH4 emissions from paddy field under rice-wheat rotation during rice and wheat growing seasons relative to timing of amendment. Acta Pedol. Sin (Chin) 52, 839–848 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks D. M. D., Van Huissteden J. & Dolman A. J. Multi-technique assessment of spatial and temporal variability of methane fluxes in a peat meadow. Agr Forest Meteorol 150, 757–774 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- WRB 2006. World reference base for soil resources 2006. IUSS Working Group. 2nd edition. World Soil Resources Reports 103 (FAO, Rome, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- Sparks D. L. et al. In Methods of soil analysis: Part 3-Chemical methods (ed. Sparks D. L. et al.) No. 5, (Agronomy Society of American, Soil Science Society of America Inc, 1996). [Google Scholar]

- Li B. et al. Combined effects of nitrogen fertilization and biochar on the net global warming potential, greenhouse gas intensity and net ecosystem economic budget in intensive vegetable agriculture in southeastern China. Atmos Environ 100, 10–19 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Brasher B. R., Franzmeier D. P., Valassis V. & Davidson S. E. Use of saran resin to coat natural soil clods for bulk-density and water-retention measurements. Soil Sci 101, 108 (1966). [Google Scholar]

- Massman W. J. A review of the molecular diffusivities of H2O, CO2, CH4, CO, O3, SO2, NH3, N2O, NO, and NO2 in air, O2 and N2 near STP. Atmos Environ 32, 1111–1127 (1998). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.