Abstract

More than 20,000 people suffer annually from ciguatera seafood poisoning in subtropical and tropical regions. The extremely low content of the causative neurotoxins, designated as ciguatoxins, in fish has hampered isolation, detailed biological studies, and preparation of anti-ciguatoxin antibodies for detecting these toxins. Furthermore, the large (3 nm in length) and complex molecular structure of ciguatoxins has impeded chemists from completing their total synthesis. In this article, the full details of studies leading to the total synthesis of ciguatoxin CTX3C are provided. The key elements of the first-generation approach include O,O-acetal formation from the right and left wing fragments, conversion from O,O-acetal to O,S-acetal, a radical reaction to cyclize the G ring, a ring-closing metathesis reaction to close the F ring, and final removal of the 2-naphtylmethyl protective groups. Subsequent studies provided a second-generation total synthesis, which is more concise and results in a higher yield. Second-generation synthesis was accomplished by using a direct method of constructing the key intermediate O,S-acetal from α-chlorosulfide and a secondary alcohol. These syntheses ensure a practical supply of ciguatoxin for biological applications.

Keywords: ciguatera, polyether, convergent strategy

Ciguatera is a human intoxication caused by the ingestion of certain reef fish (1). More than 20,000 people suffer annually from ciguatera, making it one of the most common forms of nonbacterial food poisoning. Ingestion of affected fish leads to neurological, gastrointestinal, and cardiovascular disorders, which may last up to a month or more. The most prominent symptom is a disorder of temperature sensation. Specifically, touching cold water can induce pain similar to that of an electric shock. Other symptoms include diarrhea, vomiting, muscle pain and itching, whereas paralysis, coma, and even death may occur in severe cases.

Yasumoto et al. (2) identified an epiphytic dinoflagellate, Gambierdiscus toxicus, as the causative organism and demonstrated that dinoflagellate-derived toxins are transferred by the food chain to various fish. About 100 species of fish cause ciguatera, and ciguateric fish look, taste, and smell like normal uncontaminated fish. In addition, the occurrence of poisoning is completely unpredictable. Current difficulties in predicting, detecting, and treating ciguatera have had an adverse socioeconomic impact, in particular, in developing countries.

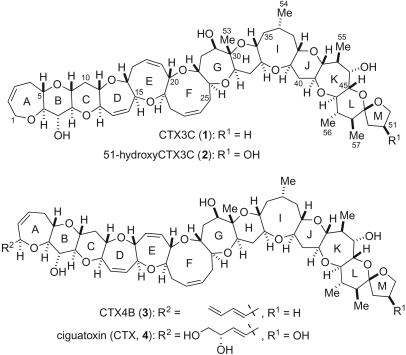

Ciguatoxins are regarded as the principal causative toxins of ciguatera seafood poisoning (Fig. 1) (3, 4). In 1989, the Yasumoto group successfully elucidated the structures of ciguatoxin (CTX) (4) and CTX4B (3) (5, 6), which were found to be large polycyclic ethers having molecular lengths >3 nm. They subsequently isolated other congeners including CTX3C (1) (7) and 51-hydroxyCTX3C (2) (8). To date, the structures of >20 congeners of ciguatoxins have been determined (9, 10).

Fig. 1.

Structures of ciguatoxins.

The lethal potencies of ciguatoxins (LD50 = 0.25–4 μg/kg) by i.p. injection into mice are much greater than the structurally related red-tide toxins, brevetoxins (LD50 > 100 μg/kg) (11–15). Orally, an amount as small as 70 ng of CTX 4 can induce intoxication symptoms in humans (16). To detect small amounts of ciguatoxins before ingestion of fish, highly sensitive antibody-based immunoassays have been necessitated; however, a reliable and easy-to-use assay kit is not currently available (17).

Pharmacological studies have found that ciguatoxins exert their toxicities by binding to the voltage-sensitive sodium channels of excitable membranes (18), which results in persistent activation of the channel. Ciguatoxins and brevetoxins share a specific binding site on the voltage-sensitive sodium channels (19, 20), although ciguatoxins bind 10 times more strongly than brevetoxins (21, 22). The site specificity and selective function of these toxins may present an opportunity for investigation into the activation and gating mechanisms of the channel itself.

However, the potential biological applications of ciguatoxins have been impeded by the extreme difficulty in isolating ciguatoxins. Thus, chemical construction has been the sole realistic solution available to obtain sufficient quantities of ciguatoxins for studying sodium channels and developing immunochemical methods. This prompted us to start a program of chemical construction of ciguatoxins. Herein, we describe full details of the total synthesis of ciguatoxin CTX3C 1 (23–25) and subsequent efforts that have provided an improved second-generation total synthesis.

Materials and Methods

All reactions sensitive to air or moisture were carried out under argon or nitrogen atmosphere in dry, freshly distilled solvents under anhydrous conditions, unless otherwise noted. Tetrahydrofuran (THF) was distilled from sodium/benzophenone, diethyl ether (Et2O) from LiAlH4, dichloromethane (CH2Cl2), pyridine, triethylamine (Et3N), and toluene from calcium hydride, and DMF and DMSO from calcium hydride under reduced pressure. All other reagents were used as supplied unless otherwise stated. Analytical TLC was performed by using E. Merck Silica gel 60 F254 precoated plates. Column chromatography was performed by using 100- to 210-μm Silica Gel 60N (Kanto Chemical Co., Tokyo), and flash column chromatography was performed by using 40- to 50-μm Silica Gel 60N (Kanto Chemical Co.). 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian INOVA 500 (500 MHz) or Varian INOVA 600 (600 MHz) spectrometer. IR spectra were recorded on a Perkin–Elmer Spectrum BX Fourier transform infrared spectrometer. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time-of-flight mass spectra were measured on an Applied Biosystems Voyager DE STR SI-3 instrument, and fast atom bombardment MS were measured on JEOL JMS-HX/HX-110A. Optical rotations were recorded on a DIP-370 polarimeter (Jasco, Tokyo). Melting points were measured on a MP-S3 micro melting point apparatus (Yanaco Analytical Instruments, Kyoto). Experimental procedures and spectroscopic data for all new compounds can be found in the supporting information, which is published on the PNAS web site.

Results and Discussion

Synthetic Strategy. The synthetic challenge posed by 1 reflects its highly complex molecular structure; 13 oxygen atoms and 52 carbon atoms are coiled in a polycyclic macromolecule that includes 13 rings and 30 stereogenic centers. Apparently, an efficient convergent strategy is crucial for practical construction of this large molecule (26–31).

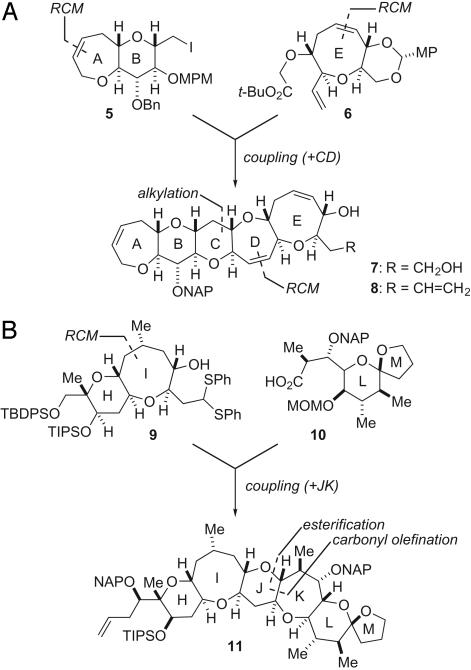

As shown in Fig. 2, we retrosynthetically dissected 1 into four relatively simple units (5, 6, 9, and 10). To maximize the convergence of the synthesis, the comparably complex left ABCDE (7 or 8) and right HIJKLM wings (11) were assembled from four fragments as follows. ABCDE ring systems 7 and 8 were produced by an alkylative coupling between AB ring 5 and E ring 6, followed by the construction of the CD ring portion with ring-closing metathesis (RCM) (32, 33) as a key transformation (34). HIJKLM ring system 11 was synthesized by (i) esterification between HI ring 9 and LM ring 10, (ii) intramolecular carbonyl olefination with a low-valent titanium complex to form the J ring (35), and (iii) sequential construction of the K ring (36, 37).

Fig. 2.

Synthesis of the left ABCDE and right HIJKLM wings from the four fragments. (A) Synthesis of left-wing fragment. MP, p-methoxyphenyl; MPM, p-methoxybenzyl. (B) Synthesis of right-wing fragment. TBDPS, t-butyldiphenylsilyl.

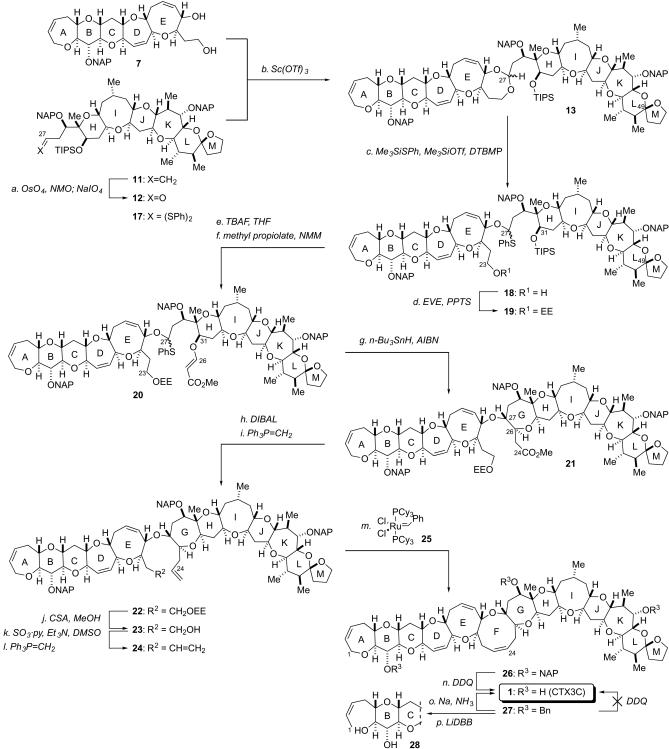

The final and most challenging tasks in the total synthesis were the coupling of these left- and right-wing fragments and the subsequent construction of the central FG ring system, followed by global deprotection. Our first-generation strategy for the total synthesis was envisioned to use five key transformations as shown in Fig. 3 (38, 39): (i) acetalization between 1,4-diol 7 and aldehyde 12, (ii) regioselective introduction of PhS group (13 → 15), (iii) radical cyclization to the seven-membered G ring (15 → 16), (iv) RCM reaction to build the nine-membered F ring, and (v) final removal of 2-naphthylmethyl (NAP) groups from the molecule (16 → 1).

Fig. 3.

First- and second-generation strategy for total synthesis of ciguatoxin CTX3C.

First-Generation Total Synthesis of CTX3C. As shown in Fig. 4, we undertook our goal of constructing the actual nanometer-scale ring system of 1, starting from the ABCDE ring and the HIJKLM ring segments (7, 11). First, the terminal olefin of 11 was oxidatively cleaved to produce aldehyde 12. Condensation of 1,4-diol 7 and aldehyde 12 (1.1 eq) by using catalytic scandium trifluoromethanesulfonate [Sc(OTf)3] successfully delivered seven-membered acetal 13 as a C27 epimeric mixture (5:1) in 69% yield (40–42). Subsequent acetal cleavage of 13 to form O,S-acetal 18 by using a reagent combination of phenylthiotrimethylsilane (Me3SiSPh) and Me3SiOTf proved to be problematic (39, 43). In trials, the right-wing S,S-acetal 17 arose, presumably from overreaction of the desired O,S-acetal 18. After extensive experimentation including model studies, it was speculated that trace amounts of TfOH, probably due to the partial hydrolysis of Me3SiOTf, catalyzed the conversion of O,S-acetal 18 to S,S-acetal 17. Thus, the reaction was performed in the presence of 2,6-di-t-butyl-4-methyl pyridine (DTBMP), which is able to trap protons without inhibiting the Lewis acid-mediated reaction. On treating 13 with Me3SiOTf, Me3SiSPh, and DTBMP at 35°C, 13 was reproducibly transformed into 18 (5:1 diastereomer ratio) in 89% yield based on recovered 13 (36%) after removal of the trimethylsilyl group on the C23-primary alcohol with K2CO3 in MeOH.

Fig. 4.

First-generation total synthesis of ciguatoxin CTX3C. Reagents and conditions: (a) OsO4, N-methylmorpholine-N-oxide (NMO), acetone/H2O (1:1), room temperature (RT), then NaIO4, RT; (b) 12 (1.1 eq), Sc(OTf)3 (0.3 eq), benzene, RT, 69% from 7; (c) Me3SiSPh (5.0 eq), Me3SiOTf (8.0 eq), DTBMP (12.0 eq), 4-Å molecular sieves, RT to 35°C; then K2CO3, MeOH, 89% based on recovered 13 (36%); (d) ethyl vinyl ether (EVE), pyridinium p-toluenesulfonate (PPTS), CH2Cl2, RT, 99%, EE, ethoxyethyl; (e) TBAF, THF, 40°C; (f) methyl propiolate, N-methylmorpholine (NMM), CH2Cl2, RT, 89% (two steps); (g) n-Bu3SnH, AIBN, toluene, 85°C; (h) DIBAL, CH2Cl2, -80°C; (i) Ph3PCH3Br, NaN(SiMe3)2, THF, 0°C; (j) 10-camphorsulfonic acid (CSA), MeOH/THF (2:1), RT, 41% (four steps); (k) SO3·pyridine (py), Et3N, DMSO/CH2Cl2 (1:1), RT; (l) Ph3PCH3Br, NaN(SiMe3)2, THF, 0°C, 100%; (m) (PCy3)2Cl2Ru = CHPh (0.3 eq), CH2Cl2,40°C, 90%; (n) DDQ (6.0 eq), CH2Cl2/H2O (20:1), RT, 63%; (o) Na, NH3, THF, EtOH, -90°C, 10 min; HPLC purification (Asahipak ODP-50, 75% MeCN-H2O), 7%; (p) lithium di-t-butylbiphenylide (LiDBB), THF, -80°C to -50°C, 1 h.

The stereoselective construction of the G ring was then investigated. The primary alcohol of 18 was protected as the ethoxyethyl ether to give 19 in 99% yield. Removal of the triisopropylsilyl (TIPS) group from 19, followed by treatment with methyl propiolate and N-methylmorpholine, afforded β-(E)-alkoxyacrylate 20 in 89% yield (two steps) (44). Compound 20 was then subjected to radical cyclization by using n-tributyltin hydride (n-Bu3SnH) and 2,2′-azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN) at 85°C in toluene, giving rise to the desired oxepane 21, the product of stereo- and chemoselective addition to the α,β-unsaturated ester.

The stereoselectivity of the cyclization is explained as indicated in Fig. 5 (45). Initially the stereochemical information of the acetal carbon was lost on formation of the radical intermediate 29. The β-(E)-alkoxyacrylate favored the extended s-transover s-cis-conformation to avoid the 1,3-diaxial-like interactions. Furthermore, the steric interactions between the bulky alkoxy group and the s-transalkoxyacrylate of the pseudoequatorial 29eq-trans resulted in the preference of the pseudoaxial 29ax-trans, from which the desired isomer 21 was the only possible outcome among the four possible isomers. Hence, the important aspect of this strategy is that the stereoselective synthesis of the O,S-acetal is not necessary, and yet the two stereogenic centers of 21 at C26 and C27 are controlled by conformation of the transition state.

Fig. 5.

Mechanistic rationale of the radical cyclization.

With the 12 ether rings in place, the final steps were construction of the F ring by RCM reaction and deprotection (Fig. 4). Diisobutylaluminum hydride (DIBAL) reduction of ester 21 to the aldehyde, followed by Wittig methylenation and acidic removal of the ethoxyethyl group, produced primary alcohol 23 in 41% overall yield (four steps). Oxidation of 23 with SO3·pyridine-DMSO and subsequent Wittig reaction afforded olefin 24 in 100% yield (two steps). Treatment of pentaene 24 with catalytic Grubbs reagent 25 (46) at 40°CinCH2Cl2 gave rise to NAP-protected CTX3C 26 in 90% yield. This remarkable transformation indicates the efficiency and reliability of metathesis reactions, even in these highly elaborate situations. As observed for natural ciguatoxins (5–9) and other model compounds (38, 47, 48), the 1H NMR signals of the F ring in 26 were severely broadened at room temperature due to the relatively slow conformational changes. Therefore, construction of the F ring in the last stage of the synthesis was favorable in avoiding complications in assigning the NMR spectra of the synthetic intermediates.

The final global deprotection to yield CTX3C was not a trivial step in our synthetic venture. We previously prepared benzyl (Bn)-protected CTX3C 27 instead of trisNAP-CTX3C 26. However, extensive studies for deprotection of Bn groups from 27 met only limited success. Reductive cleavage of the benzyl ethers of 27 with lithium di-t-buthylbiphenylide (LiDBB) (49) was accompanied by reductive cleavage of the A ring allylic ether, leading to compound 28. On the other hand, oxidative treatment of 27 with 2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone (DDQ) resulted in a complex mixture, presumably attributable to the low reactivity of pseudoaxial C44-benzyloxy group and competing undesired oxidation in particular involving the A ring. Conversion of 27 to 1 was realized by a carefully controlled Birch reduction; treatment of 27 with sodium in NH3/EtOH/THF at -90°C for 10 min resulted in global deprotection to yield pure synthetic CTX3C 1 (7% yield after HPLC purification) (23).

Since removal of the benzyl groups was not satisfactory for the practical synthesis of 1, the NAP group was chosen as an alternative protective group that can be chemoselectively removed under oxidative conditions and can survive the variety of conditions used in the total synthesis (50, 51). In fact, the stability of NAP ethers up to 26 was proven in several reactions, as shown in Fig. 4.

Oxidative removal of the NAP groups of 26 was thus pursued in the presence of the potentially reactive allylic ether of the A ring. A solution of 26 in CH2Cl2/H2O (20:1) was treated with 6 eq of DDQ (2 eq per NAP group) at room temperature for 2 h. We were pleased to find that the standard workup and column chromatography afforded synthetic CTX3C 1 in 63% yield (24). As expected, the NAP groups were smoothly removed at ambient temperature in much shorter reaction time than that for Bn groups. The synthetic CTX3C was determined to be identical with the naturally occurring form (TLC, HPLC, 1H and 13C NMR, circular dichroism, and MS) (7). Our study also confirmed the absolute stereochemistry of ciguatoxins (52).

Second-Generation Total Synthesis of Ciguatoxin CTX3C. The first-generation total synthesis demonstrated the power of the O,S-acetal strategy to build the complex polyether structure. In the scope of synthesizing CTX congeners (Fig. 1) and other natural and artificial polyethers, we have become interested in further expanding the applicability of the strategy by using alternative methods. In particular, the development of a new, mild route to O,S-acetal without the need for highly acidic conditions such as in the acetalization (7 + 12 → 13, Fig. 4) and PhS introduction (13 → 18) would be important for synthesizing structures with acid-sensitive functionalities.

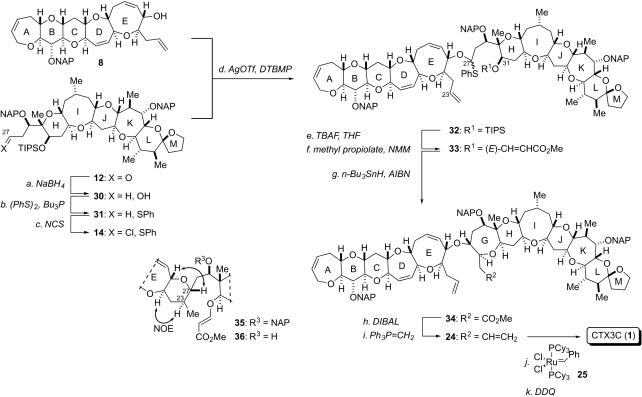

In light of these considerations, we planned the direct construction of O,S-acetal 15 by coupling secondary alcohol 8 and α-chlorosulfide 14 (Fig. 3) (53–55). This type of reaction was developed by Mukaiyama et al. (56) and was recently explored further by the Hindsgaul group (57) in the context of their syntheses of oligosaccharides. The obtained 15 would be readily subjected to the radical cyclization to form the seven-membered ring (15 → 16). Halophilic reagents, such as the silver cation, for the coupling are highly chemoselective, allowing the use of various functional groups. Also, fewer synthetic steps occur in the alternative method than in the previous one because it is not necessary to proceed by O,O-acetal 13.

The second-generation total synthesis is illustrated in Fig. 6. To prepare for the coupling reaction, the right-wing sulfide 31 was synthesized from aldehyde 12 in two steps (75% overall yield): (i) NaBH4 reduction of 12 in MeOH and (ii) subsequent introduction of phenyl sulfide by using (PhS)2 and Bu3P in pyridine (58). Installation of the α-chloride to sulfide 31 was realized by using NCS, leading to α-chlorosulfide 14 (56, 59, 60). The reproducibility of the chlorination depended on the experimental conditions, and the reliable conversion was attained by addition of 1 eq of NCS in CH2Cl2 to a solution of 31 in CCl4 at room temperature. The obtained solution of 14 in CH2Cl2/CCl4 (1:6) was directly used in the subsequent reaction because of the instability of 14 to any standard workup.

Fig. 6.

Second-generation total synthesis of ciguatoxin CTX3C. Reagents and conditions: (a) NaBH4, MeOH/CH2Cl2 (1:1), 0°C, 81%; (b) (PhS)2, n-Bu3P, pyridine, RT, 93%; (c) N-chlorosuccinimide (NCS) (1.0 eq), CH2Cl2/CCl4 (1:6), RT; (d) 8 (1.2 eq), AgOTf (2.0 eq), DTBMP (3.0 eq), 4-Å molecular sieves, CH2Cl2/CCl4 (5:1), -70°C to 0°C, 70% from 14; (e) TBAF, THF, 35°C, 85%; (f) methyl propiolate, N-methylmorpholine (NMM), CH2Cl2, RT, 100%; (g) n-Bu3SnH, AIBN, toluene, 85°C, 34: 54%, 35: 27%; (h) DIBAL, CH2Cl2, -90°C; (i) Ph3PCH3Br, t-BuOK, THF, 0°C, 92% (two steps); (j) (PCy3)2Cl2Ru = CHPh (0.3 eq), CH2Cl2, 40°C, 90%; (k) DDQ (6.0 eq), CH2Cl2/H2O (20:1), RT, 63%.

The coupling reaction to build decacyclic O,S-acetal 32 was effected by the action of AgOTf. The solution of α-chlorosulfide 14 was introduced to a CH2Cl2 solution of alcohol 8 (1.2 eq) and AgOTf (2.0 eq) in the presence of DTBMP (3.0 eq) and 4-Å molecular sieves. In this way, O,S-acetal 32 was obtained in 70% yield as a single diastereomer, thus accomplishing the direct construction of the key intermediate.

Similarly to the previous synthesis, the G ring was cyclized. The TIPS group of 32 was removed with tetra-n-butylammonium fluoride (TBAF) to give the secondary alcohol, which was converted to β-alkoxyacrylate 33 by using methyl propiolate and N-methylmorpholine in 85% yield. By subjecting 33 to the radical cyclization, the G ring of 34 was constructed stereoselectively in 54% yield along with 35 arising from the 6-exo cyclization to the terminal olefin (27% yield). The structure of new stereocenters of the byproduct was determined by the nuclear Overhauser effects of the deprotected compound 36.

Although the regioselectivity of the radical cyclization should be optimized, the presence of the terminal olefin in 34 facilitated the synthesis of the substrate for the final RCM reaction. Only two steps involving DIBAL reduction of 34 and the subsequent methylenation were required to obtain tetraene 24 in 92% yield. Finally, after the previous total synthesis in Fig. 4, RCM reaction of 24 resulted in the formation of trisNAP-CTX3C 24, global deprotection of which provided the targeted CTX3C 1. Remarkably, the transformations from the coupling reaction to 1 require only nine steps (previously 13 steps were required), and the overall yield was improved from 12% to 16%.

Conclusions

First- and second-generation total syntheses of ciguatoxin CTX3C were developed, and both enlist the decacyclic O,S-acetal as a key intermediate. The two highly convergent approaches secure the first chemical supply of CTX3C and are readily applicable to ciguatoxin congeners because of their common FG ring structures. Moreover, synthetic CTX3C and the intermediates described in this article will help accelerate the preparation of anti-ciguatoxin antibodies for detecting ciguateric fish and create probes for the voltage-sensitive sodium channel that may provide valuable insight into the protein–ligand interaction at the molecular level and the activation and gating mechanisms.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Takashi Iwashita and Dr. Tsuyoshi Fujita (Suntory Institute for Bioorganic Research) for their high-resolution mass spectroscopy measurements, Prof. Masayuki Satake for the NMR measurements of CTX3C, and Mr. Toyonobu Usuki for his contribution to the structural elucidation of a synthetic intermediate. This work was supported by a Grant-in-aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: AIBN, 2,2′-azobisisobutyronitrile; Bn, benzyl; Bu, butyl; CTX, ciguatoxin; Cy, cyclohexyl; DDQ, 2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone; DIBAL, diisobutylaluminum hydride; DTBMP, 2,6-di-t-butyl-4-methylpyridine; Me, methyl; NAP, 2-naphthylmethyl; NCS, N-chlorosuccinimide; OTf, trifluoromethanesulfonate; Ph, phenyl; py, pyridine; RCM, ring-closing metathesis; RT, room temperature; TBAF, tetra-n-butylammonium fluoride; THF, tetrahydrofuran; TIPS, triisopropylsilyl.

References

- 1.Lewis, R. J. (2001) Toxicon 39, 97-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yasumoto, T., Nakajima, I., Bagnis, R. & Adachi, R. (1977) Bull. Jpn. Soc. Sci. Fish. 43, 1015-1026. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yasumoto, T. & Murata, M. (1993) Chem. Rev. 93, 1897-1909. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scheuer, P. J. (1994) Tetrahedron 50, 3-18. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murata, M., Legrand, A.-M., Ishibashi, Y. & Yasumoto, T. (1989) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 111, 8929-8931. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murata, M., Legrand, A.-M., Ishibashi, Y., Fukui, M. & Yasumoto, T. (1990) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 112, 4380-4386. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Satake, M., Murata, M. & Yasumoto, T. (1993) Tetrahedron Lett. 34, 1975-1978. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Satake, M., Fukui, M., Legrand, A.-M., Cruchet, P. & Yasumoto, T. (1998) Tetrahedron Lett. 39, 1197-1198. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewis, R. J., Vernoux, J.-P. & Brereton, I. M. (1998) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120, 5914-5920. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yasumoto, T., Igarashi, T., Legrand, A.-M., Cruchet, P., Chinain, M., Fujita, T. & Naoki, H. (2000) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 4988-4989. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin, Y.-Y., Risk, M., Ray, S. M., Van Engen, D., Clardy, J., Golik, J., James, J. C. & Nakanishi, K. (1981) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 103, 6773-6775. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shimizu, Y., Chou, H.-N. & Bando, H. (1986) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 108, 514-515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shimizu, Y. (1993) Chem. Rev. 93, 1685-1698. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nicolaou, K. C., Rutjes, F. P. J. T., Theodorakis, E. A., Tiebes, J., Sato, M. & Untersteller, E. (1995) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117, 10252-10263. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nicolaou, K. C., Gunzner, J. L., Shi, G.-q., Agrios, K. A., Gärtner, P. & Yang, Z. (1999) Chem.-Eur. J. 5, 646-658. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yasumoto, T., Fukui, M., Sasaki, K. & Sugiyama, K. (1995) J. AOAC Int. 78, 574-582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oguri, H., Hirama, M., Tsumuraya, T., Fujii, I., Maruyama, M., Uehara, H. & Nagumo, Y. (2003) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 7608-7612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bidard, J.-N., Vijverberg, H. P. M., Frelin, C., Chungue, E., Legrand, A.-M., Bagnis, R. & Lazdunski, M. (1984) J. Biol. Chem. 259, 8353-8357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lombet, A., Bidard, J.-N. & Lazdunski, M. (1987) FEBS Lett. 219, 355-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poli, M. A., Mende, T. J. & Baden, D. G. (1986) Mol. Pharmacol. 30, 129-135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dechraoui, M.-Y., Naar, J., Pauillac, S. & Legrand, A.-M. (1999) Toxicon 37, 125-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inoue, M., Hirama, M., Satake, M., Sugiyama, K. & Yasumoto, T. (2003) Toxicon 41, 469-474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hirama, M., Oishi, T., Uehara, H., Inoue, M., Maruyama, M., Oguri, H. & Satake, M. (2001) Science 294, 1904-1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Inoue, M., Uehara, H., Maruyama, M. & Hirama, M. (2002) Org. Lett. 4, 4551-4554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Inoue, M. & Hirama, M. (2004) Synlett, 577-595.

- 26.Alvarez, E., Candenas, M.-L., Pérez, R., Ravelo, J. L. & Martín, J. D. (1995) Chem. Rev. 95, 1953-1980. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takakura, H., Sasaki, M., Honda, S. & Tachibana, K. (2002) Org. Lett. 4, 2771-2774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fujiwara, K., Koyama, Y., Kawai, K., Tanaka, H. & Murai, A. (2002) Synlett, 1835-1838.

- 29.Kira, K. & Isobe, M. (2001) Tetrahedron Lett. 42, 2821-2824. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bond, S. & Perlmutter, P. (2002) Tetrahedron 58, 1779-1787. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clark, J. S. & Hamelin, O. (2000) Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 39, 372-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fürstner, A. (2000) Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 39, 3013-3043. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trnka, T. M. & Grubbs, R. H. (2001) Acc. Chem. Res. 34, 18-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maruyama, M., Inoue, M., Oishi, T., Oguri, H., Ogasawara, Y., Shindo, Y. & Hirama, M. (2002) Tetrahedron 58, 1835-1851. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rahim, Md. A., Fujiwara, T. & Takeda, T. (2000) Tetrahedron 56, 763-770. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tatami, A., Inoue, M., Uehara, H. & Hirama, M. (2003) Tetrahedron Lett. 44, 5229-5233. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Inoue, M., Yamashita, S., Tatami, A., Miyazaki K. & Hirama, M. (2004) J. Org. Chem. 69, 2797-2804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sasaki, M., Noguchi, T. & Tachibana, K. (2002) J. Org. Chem. 67, 3301-3310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Imai, H., Uehara, H., Inoue, M., Oguri, H., Oishi, T. & Hirama, M. (2001) Tetrahedron Lett. 42, 6219-6222. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fukuzawa, S., Tsuchimoto, T., Hotaka, T. & Hiyama, T. (1995) Synlett, 1077-1078.

- 41.Ishihara, K., Karumi, Y., Kubota, M. & Yamamoto, H. (1996) Synlett, 839-841.

- 42.Inoue, M., Sasaki, M. & Tachibana, K. (1999) J. Org. Chem. 64, 9416-9429. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim, S., Do, J. Y., Kim, S. H. & Kim, D. (1994) J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1 17, 2357-2358. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee, E., Tae, J. S., Lee, C. & Park, C. M. (1993) Tetrahedron Lett. 34, 4831-4834. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sasaki, M., Inoue, M., Noguchi, T., Takeichi, A. & Tachibana, K. (1998) Tetrahedron Lett. 39, 2783-2786. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schwab, P., Grubbs, R. H. & Ziller, J. W. (1996) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 100-110. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Inoue, M., Sasaki, M. & Tachibana, K. (1999) Tetrahedron 55, 10949-10970. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takai, S., Sawada, N. & Isobe, M. (2003) J. Org. Chem. 68, 3225-3231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sabes, S. F., Urbanek, R. A. & Forsyth, C. J. (1998) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120, 2534-2542. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wright, J. A., Yu, J. & Spencer, J. B. (2001) Tetrahedron Lett. 42, 4033-4036. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xia, J., Abbas, S. A., Locke, R. D., Piskorz, C. F., Alderfer, J. L. & Matta, K. L. (2000) Tetrahedron Lett. 41, 169-173. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Satake, M., Morohashi, A., Oguri, H., Oishi, T., Hirama, M., Harada, N. & Yasumoto, T. (1997) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119, 11325-11326. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Inoue, M., Wang, G. X., Wang, J. & Hirama, M. (2002) Org. Lett. 4, 3439-3442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Inoue, M., Wang, J., Wang, G.-X., Ogasawara, Y. & Hirama, M. (2003) Tetrahedron 59, 5645-5659. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Inoue, M., Yamashita, S. & Hirama, M. (2004) Tetrahedron Lett. 45, 2053-2056. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mukaiyama, T., Sugaya, T., Marui, S. & Nakatsuka, T. (1982) Chem. Lett. 1555-1558.

- 57.McAuliffe, J. C. & Hindsgaul, O. (1998) Synlett, 307-309.

- 58.Nakagawa, I. & Hata, T. (1975) Tetrahedron Lett. 17, 1409-1412. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Iio, H., Nagaoka, H. & Kishi, Y. (1980) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 102, 7967-7969. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dilworth, B. M. & McKervey, M. A. (1986) Tetrahedron 42, 3731-3752. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.