Abstract

The regulatory information for a eukaryotic gene is encoded in cis-regulatory modules. The binding sites for a set of interacting transcription factors have the tendency to colocalize to the same modules. Current de novo motif discovery methods do not take advantage of this knowledge. We propose a hierarchical mixture approach to model the cis-regulatory module structure. Based on the model, a new de novo motif-module discovery algorithm, CisModule, is developed for the Bayesian inference of module locations and within-module motif sites. Dynamic programming-like recursions are developed to reduce the computational complexity from exponential to linear in sequence length. By using both simulated and real data sets, we demonstrate that CisModule is not only accurate in predicting modules but also more sensitive in detecting motif patterns and binding sites than standard motif discovery methods are.

Transcription factors (TFs) regulate genes by binding to their recognition sites. The common pattern of the binding sites for a TF is called a motif, usually modeled by a position-specific weight matrix (PWM). Experimental methods such as DNase footprinting (1) and gel-mobility shift assay (2, 3) have allowed the determination of some binding sites for selected TFs. Because these procedures are time-consuming, several computational methods have been developed for de novo motif discovery, including progressive alignment (4, 5), the expectation-maximization algorithm (6, 7), the Gibbs sampler (8–12), word enumeration (13, 14), and the dictionary model (15, 16). The propagation model (17) and the recursive Gibbs motif sampler (18) have been developed for locating multiple motifs simultaneously. In addition, methods also exist that combine motif discovery with gene expression data (19–21) or phylogenetic footprinting (22, 23). These experimental and computational analyses have given us a good number of useful TF motifs. However, there are still many important TFs whose motifs remain to be characterized. What is more, molecular analyses have established that most eukaryotic genes are not controlled by a single site but by cis-regulatory modules (CRMs), each consisting of multiple TF-binding sites (TFBSs) that act in combination (24–27). It can be argued that motif discovery is but an intermediate step toward the characterization of CRMs. Current approaches on module prediction such as those based on logistic regression (28, 29) or hidden Markov models (30, 31) depend on the availability of known motifs, i.e., PWMs for several TFs hypothesized to bind synergistically to regulatory modules. Clearly, we cannot apply these methods to the situations where no prior knowledge on the TFs is available, and in these cases we must resort to de novo motif discovery algorithms. We hypothesized that greater sensitivity and specificity can be achieved for motif discovery by considering the colocalization of different TFBSs and searched for modules and motifs simultaneously. It is clear that the task of module discovery and motif estimation is tightly coupled: on one hand, motif patterns and binding sites are essential for predicting regulatory modules; on the other hand, discovery of modules will greatly improve the performance of motif detection.

In this article, we propose a hierarchical mixture (HMx) model and develop a fully Bayesian approach for the simultaneous inference of modules, TFBSs, and motif patterns based on their joint posterior distribution. We test the approach by using both simulated and real data sets. Simulation studies show that, by capturing the combinatorial patterns of cooperating TFBSs, our algorithm detects modules accurately and is much more precise than standard motif discovery algorithms are in finding true binding sites. Similar improvement is observed when the method is tested on the known CRMs from a number of Drosophila developmental genes (26, 32, 33) and on the regulatory regions of a set of muscle-specific genes (28). Our approach for de novo motif-module discovery is of great current interest. Expression microarrays (34) and serial analysis of gene expression (35) have provided powerful means to identify clusters of genes tightly regulated during various cellular processes. Genes in the same clusters have a higher likelihood of sharing similar CRMs. Comparative analysis of multiple genomic sequences can further identify conserved regions enriched for such modules (36, 37). Finally, chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by microarray (ChIP-on-chip) is able to predict the binding locations of a TF in the whole genome with a resolution of 500–2,000 bp. These approaches are expected to provide sets of sequences enriched for CRMs involving an unknown or a partially unknown set of regulatory TFs. The identification of the CRMs within these sequences and the clarification of their structures, which are essential steps in understanding the regulatory networks, will depend on computational methods such as those proposed in this article.

Methods

HMx Model for Cis-Regulatory Modules. Our goal was to search for the binding sites for K different TFs within the CRMs of a given set of sequences S. We proposed a two-level HMx model for CRMs. At the first level, the sequences can be viewed as a mixture of CRMs, each of length l, and pure background sequences outside the modules; at the second level, modules are modeled as a mixture of motifs and within-module background. Detailed specification of the HMx model is illustrated in Fig. 1. The background sequences, both the regions outside the modules and the nonsite segments within the modules, are modeled by a first-order Markov chain θ0.

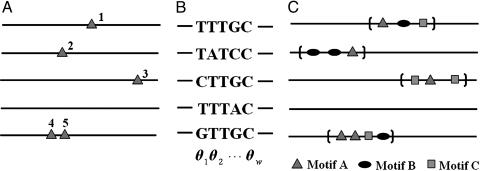

Fig. 1.

Specification of the HMx model. (A) Unaligned motif sites (triangles indexed by 1, 2,... ,5).(B) The aligned motif sites can be represented by a product multinomial model or equivalently by a PWM. Each binding site is regarded as a realization of a sequence of independent random variables X1X2...Xw, where each Xi (i = 1,..., w) follows a multinomial distribution over the four letters {A,C,G,T} with probabilities θi = [θi(A), θi(C), θi(G), θi(T)]. The whole motif is thus specified by a set of multinomial probabilities Θ = [θ1, θ2,..., θw]. (C) The cis-regulatory regions of coregulated genes are enriched for modules (the regions in the brackets). Each module is a sequence segment x1x2...xl in which several types of motifs (A, B, and C), each with its own product multinomial parameter (Θk), can occur. The rates of the occurrence of modules and their motif sites are denoted by r and qk (k = 1,..., K), respectively.

It is helpful to think of the HMx model as a stochastic machinery that generates sequences. Suppose the width of the kth motif is wk and its product multinomial model (PWM) is Θk (k = 1,..., K). Starting from the first sequence position, we made a series of random decisions of whether to initiate a module or generate a letter from the background model, with probabilities r and 1 - r, respectively. If a module was started at position i, within the region of [i, i + l - 1], we generated background letters or initiated the kth motif sites, with probabilities q0 and qk ( ), respectively. If a site for the kth motif was initiated at position n, we generated wk letters from its PWM Θk and placed them at [n, n + wk - 1]. After we reached the end of the current module at position i + l - 1, the decision at the next position was reverted back to the choice between sampling from the background or initiating a new module. Let M denote the module indicators and Ak denote the indicators for the binding sites for the kth motif. We used S(M) to denote the CRMs and S(Mc) to denote the background outside the modules. To simplify the notation, we let A = {A0, A1,..., AK}, where A0 indicates the nonsite background sequences in the modules, Θ = {θ0, Θ1,..., ΘK}, q = {q0, q1,..., qK}, and W = {w1,..., wK}. The notations for the model are summarized in Table 1.

), respectively. If a site for the kth motif was initiated at position n, we generated wk letters from its PWM Θk and placed them at [n, n + wk - 1]. After we reached the end of the current module at position i + l - 1, the decision at the next position was reverted back to the choice between sampling from the background or initiating a new module. Let M denote the module indicators and Ak denote the indicators for the binding sites for the kth motif. We used S(M) to denote the CRMs and S(Mc) to denote the background outside the modules. To simplify the notation, we let A = {A0, A1,..., AK}, where A0 indicates the nonsite background sequences in the modules, Θ = {θ0, Θ1,..., ΘK}, q = {q0, q1,..., qK}, and W = {w1,..., wK}. The notations for the model are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Notations used in the HMx model.

| S | Set of sequences (observed data) |

| M | Indicators for a module start |

| Ak | Indicators for a site start for motif k |

| θ0 | First-order Markov chain for background |

| Θk | Product multinomial parameters (PWM) for motif k |

| r | Probability of a module start |

| qk | Probability of starting a site for motif k |

| wk | Width of motif k |

Under the HMx model, the complete sequence likelihood with M and A given is

|

[1] |

Combining Eq. 1 with the prior distributions for all the parameters gives rise to the joint posterior distribution:

|

[2] |

where conjugate prior distributions are prescribed, i.e., a product Dirichlet distribution with parameter βk (a wk × 4 matrix) for (Θk|wk), a Dirichlet distribution with parameter α (a vector of length K + 1) for q, and Beta(a, b) for r. We put a Poisson(w0) prior on wk (k = 1,..., K).

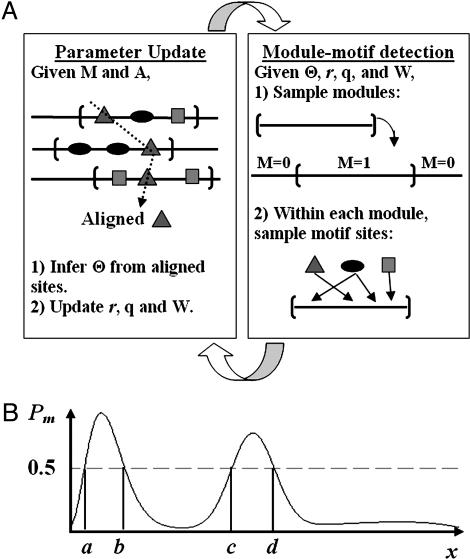

Bayesian Inference. We regarded M and A as missing data and used the Gibbs sampler (38–40) to perform Bayesian inference. Gibbs sampling algorithms are widely used for motif finding (8, 9, 17), but our problem was much more complex than traditional motif discovery because of its hierarchical structure. With a random initiation, our algorithm (CisModule) iteratively cycles through the steps of parameter update and module-motif detection (Fig. 2A). (i) Given current modules and motif sites (M and A), we updated all the parameters Ψ = (Θ, q, W, r) by sampling from their conditional posterior distributions [Ψ|M, A, S] (see Appendix A). (ii) Given current values of the parameters, we sampled modules and motif sites from the conditional distribution [M, A|Ψ, S]. Without loss of generality, suppose the sequence data are S = {x1x2,..., xL} = x[1,L]. The computational bottleneck is the step of module-motif detection. Sampling modules and sites naively results in a computational complexity of O((Kll)L/l), which increases exponentially with the total sequence length L. By using stochastic recursions we reduced the complexity to O(KL). First, we performed “forward summation” to compute P(S|Ψ) using the recursion (Eq. 5 in Appendix B). Then “backward sampling” was used to generate the module indicators as follows. Starting from n = L, at position n, we decided whether (i) xn was at the last position of a module or (ii) xn was from the background. The probabilities of these two events are proportional to the terms An(Ψ) and Bn(Ψ) in Eq. 6 in Appendix B, which are already computed from the forward summation. Depending on choosing event i or event ii, we moved to position n - l or n - 1 and repeated the binary decision process. In this way, we generated all the module indicators. Once modules were updated, we again used forward summation (see Eq. 7 in Appendix B) and backward sampling to update motif indicators within each module. Suppose we have sampled the motif indicators backward up to position m in the current module. The sequence segment x[m-wk+1,m] (k = 0,..., K) is drawn as a background letter (k = 0, w0 = 1) or a site for one of the K motifs with probability proportional to the K + 1 terms in Eq. 7. Apparently, because sites are sampled for each module separately, the combinatorial site patterns in the individual modules can be different.

Fig. 2.

Algorithm for model fitting and motif-module identification. (A) Iterative sampling procedure. In parameter update (Left), we are given the locations of modules and motif sites. Therefore, we align the motif sites of the same type to update the PWM of that motif. In module and motif detection (Right), we use stochastic recursions (see Appendix B and text) to sample the locations of modules and motif sites, conditional on the updated parameter values. (B) The use of sampled module indicators for module identification. For each position i in the sequences, compute Pm(i) = the proportion of times during iterative sampling when position i is within a sampled module. The positions with Pm(i) > 0.5 (e.g., the regions [a,b] and [c,d]) are our predicted modules. See Fig. 3A for further discussion.

By using the samples from the joint posterior distribution (Eq. 2), we obtained marginal distributions of the width and number of sites for each motif by smoothing their sampling histograms by means of a moving average. Based on the marginal modes that can be found through enumeration, we estimated ŵk and n̂k (k = 1,..., K). The top n̂k ŵk-mers that were most frequently sampled as sites for the kth motif were aligned as output sites. Furthermore, we inferred the modules by the marginal posterior probability of each sequence position being sampled as within modules. The positions where this probability is >0.5 were output as modules (Fig. 2B).

Strategies on l and K. In the discussion above, module length l and TF number K were left as user-input parameters. We now discuss how to determine l and K in case we have no prior knowledge of them.

An extra conditional sampling by a Metropolis update can be performed to determine the most likely module length. Let l be the current module length. We propose a new one, l + δ (δ = ±10), and accept it with the Metropolis ratio,

|

[3] |

where the prior distribution π(l) is geometric with mean l0 (usually between 100 and 200).

It is often desirable to provide some information about the TF number K. This can be formulated as a Bayesian model selection problem. Let HK (K = 1, 2,...) denote the hypothesis that there are K motifs (TFs) and H0 denote the null hypothesis that S is generated from pure background. With π(HK) ∝ (1/3)K as the prior, we calculate the posterior odds of HK over H0,

|

[4] |

where P(S|H0) is of known form and P(S|HK) can be calculated by importance sampling (see Appendix C for details). Thus we can run CisModule with K = 1,..., Km, where with Km the algorithm stops detecting new motifs, and treat the K* ∈ {1,..., Km - 1} that maximizes the posterior odds (Eq. 4) as our estimated number of motif types.

Results

We tested CisModule on both simulated and real biological data sets. Data Sets 1–4 are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site.

Simulation Studies. It is known that E2F, YY1, and c_MYC are potential cooperating factors (41). Thus, in our simulation, motif sites were generated according to the weight matrices of these three TFs based on TRANSFAC (42) matrix accession numbers, V$E2F_03, V$YY1_02, and V$MYCMAX_02, respectively. The background sequences were generated by a first-order Markov chain with parameters estimated by >2,000 upstream 1-kb sequences from the ensembl genome database (www.ensembl.org). In the first simulation study, each module was 100 bp long and contained one E2F site, one YY1 site, and one c_MYC site, randomly placed in the module. One data set consisted of 40 sequences, each 500 bp in length, and 20 modules were randomly located in these sequences. In the second simulation study, each data set contained 30 sequences, each 800 bp in length. Twenty 200-bp-long modules of different site combinations were generated, where four of them contained only three E2F sites, eight of them contained one E2F site, two YY1 sites, and one c_MYC site, and the rest contained one E2F site, one YY1 site, and two c_MYC sites. This different site combination mimics the fact that one TF (E2F) may work with different partners. For each of the simulation studies above, 10 data sets were generated independently. We applied CisModule to these data sets and fixed the module length to be 100 and 200 bp, respectively. The number of motifs K was set as 3 in both studies.

We evaluated our prediction for modules by their total length and coverage of true sites. The total lengths of our predicted modules were 2,009 and 4,108 bp on average for the two simulation studies, corresponding to excess rates of 0.5% and 2.7% over the actual module lengths (2,000 and 4,000 bp), respectively. The average true site coverage rates of the predicted modules were 84.3% and 94.0%, which showed that our module prediction was very informative with a high coverage of true sites and a low excess in length. In terms of motif discovery, we compared our predictions with MEME (7) and BioProspector (BP) (11) on these data sets. We set these algorithms to run multiple times and output the top 20 motifs they found. From Table 2 we see that, for all of the cases, CisModule showed the greatest success rates of discovering the correct motif patterns and found more true sites with comparable numbers of false positives. The improvement over MEME and BP was especially significant for weakly conserved motifs (c_MYC). These results demonstrate that the HMx model captures the colocalization of TFBSs and CisModule is capable of using this information to improve de novo motif discovery.

Table 2. Comparison of CisModule, MEME, and BP for simulated data sets.

| MEME

|

BP

|

CisModule

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motifs | Ps | TP | FP | Ps | TP | FP | Ps | TP | FP |

| E2F (20) | 0.6 | 10.8 | 3.0 | 0.8 | 10.9 | 4.5 | 1.0 | 17.3 | 2.9 |

| YY1 (20) | 1.0 | 15.3 | 5.1 | 0.9 | 11.2 | 3.3 | 1.0 | 17.1 | 2.3 |

| c_MYC (20) | 0.4 | 10.0 | 3.3 | 0.6 | 11.8 | 4.8 | 0.9 | 16.7 | 4.1 |

| E2F (28) | 0.9 | 16.6 | 3.9 | 0.9 | 15.3 | 4.7 | 1.0 | 23.7 | 4.6 |

| YY1 (24) | 1.0 | 18.6 | 2.1 | 0.8 | 12.4 | 3.8 | 1.0 | 21.5 | 2.5 |

| c_MYC (24) | 0.3 | 9.3 | 5.7 | 0.6 | 10.3 | 7.3 | 1.0 | 20.5 | 6.9 |

Ps is the success rate, i.e., the fraction of the data sets for which the algorithms found the motif pattern. TP and FP are the average numbers of true sites and false sites predicted by the algorithms over the data sets for which they successfully found the motif pattern. The upper and lower halves are the results for the first and second simulation studies, respectively. The TF names are followed by the numbers of true sites in the sequences.

We repeated the experiments with K = 4, and, for all of the data sets, CisModule did not predict any new (false) motifs. By using the posterior odds calculation, CisModule correctly estimated the true motif numbers (K* = 3) for 19 of the 20 data sets. We also tested our algorithm assuming l unknown. The most likely module lengths predicted by CisModule were within 30 bp of the true lengths for 18 data sets.

Homotypic Regulatory Modules in Drosophila. Analyses of experimental data from the early developmental Drosophila gene enhancers show that these regions are highly enriched of homotypic clusters, i.e., multiple binding sites for one TF are tightly clustered together (32, 33). More than 60 regulatory modules for 20 different genes were collected and the known regulatory interactions using published data were annotated (32). We built three sequence sets, each of which contained all the CRMs for one of the three most frequent binding motifs in their data sets, Bicoid (Bcd), Hunchback (Hb), and Krüppel (Kr). Thirty-four experimentally reported sites are in our data sets: 12 Bcd sites in three sequences, 14 Hb sites in four sequences, and 8 Kr sites in two sequences. Because binding sites are not reported in the remaining sequences, we scanned the data sets for putative target sites based on the known PWMs for the three TFs (32). These scanned-based sites served as an alternative basis for our comparison.

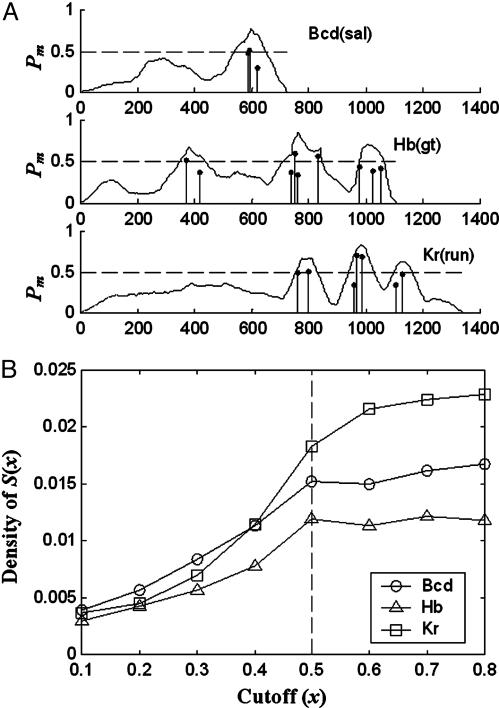

We applied CisModule to the three data sets with K = 1 (because the modules are clusters of binding sites for one TF) and l = 100. By the module-sampling step, CisModule provides more information through the marginal posterior probability of each position being sampled as within modules (Pm in Fig. 2B). Some examples of the predicted modules with this probability are illustrated in Fig. 3A. For each data set, we selected all the sequence positions with this probability greater than a given value x, denoted by S(x), and calculated the density of S(x), defined as the ratio of the number of high-score sites (those within the top 0.5% in scanning) to the size of S(x), for x varying from 0.1 to 0.8 (Fig. 3B). When x was increased to 0.9, the sizes of S(x) were too small to calculate the densities. From the figure it is clear that for x ≤ 0.5 the densities increase with x, i.e., those sequence positions that are more likely to be sampled within modules have a higher density of top sites. The densities for x = 0.5 (corresponding to the broken horizontal lines in Fig. 3A) for all of the three data sets were significantly higher than 0.5% with P values < 3E-6. If we further increased x (≥0.6), all of the positions in S(x) were selected from module regions, and thus the densities were approximately the same for different x.

Fig. 3.

Module prediction in the Drosophila data set. (A) Marginal posterior module probability (Pm) plots for example sequences in the three data sets of Drosophila homotypic modules. Pm is the probability of being sampled as within modules and it is plotted as a function of the position in the sequences (the solid curves). The horizontal broken lines correspond to Pm = 0.5, and the sequence bases with Pm > 0.5 are our predicted modules. The vertical lines are the motif sites predicted by CisModule. (B) Top site density of S(x) vs. cutoff value x. The broken vertical line at x = 0.5 corresponds to that of Pm = 0.5 in A.

As a comparison, we also applied MEME and BP to the data sets to find the top 20 motifs. From Table 3 we see that CisModule not only successfully discovered correct motifs in all three data sets but also found many more experimentally reported sites than the other two methods did. In total it reached a sensitivity of 56% for these reported sites. The numbers of output sites by CisModule were slightly more than those of scanned-based sites, because some weakly conserved sites missed by scanning can be detected by CisModule if they are close enough to other sites. The logo plots (43) for the three motifs found by CisModule are shown in Fig. 4, which is published in supporting information on the PNAS web site, where we see that they are consistent with the known consensus sequences listed in the figure legend. Furthermore, with the jaspar database (44, 45), the known Hb motif ranked number 1 compared with our predicted Hb matrix with a similarity score of 97/100. (The known motifs for Bcd and Kr are not collected in the jaspar database, so we did not compare these two factors to the database.) We also repeated the experiments with K = 2. For the Bcd and Kr data sets, CisModule did not output any new motifs. For the Hb data set, a weak motif with consensus GCMGGNM showed cooccurrence, but the posterior model odds was maximized at K* = 1. These results agreed with the homotypic cluster phenomenon.

Table 3. Comparison of CisModule (CMD), MEME, and BP for CRMs in Drosophila.

| TF | L/N | n1/n2 | MEME | CMD | BP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bcd | 11,984/10 | 12/49 | — | 7/68 | 1/10 |

| Hb | 24,789/19 | 14/116 | 3/50 | 7/138 | — |

| Kr | 12,741/10 | 8/44 | — | 5/61 | 1/14 |

| Total reported sites | 34 | 3 | 19 | 2 |

Each data set is denoted by its regulatory TFs. L and N are the total length and number of sequences in each data set, respectively. n1 and n2 are the numbers of experimentally reported sites and scanned-based sites, respectively.–indicates that the algorithm fails to find the motif; if the correct motif is found, the number of reported sites/the number of predicted sites are presented in the corresponding entry for each method. The summary of performance on experimentally reported sites is shown in the last row.

Muscle-Specific Regulatory Regions. Logistic regression was proposed as a predictive model for the regulatory regions for muscle-specific expression (28), where five TFs (Mef-2, Myf, Sp-1, SRF, and TEF) known to control the expression were used as predictors. The positive training set for the logistic regression was composed of 29 regulatory sequences sufficient for skeletal-muscle-specific expression that have been experimentally localized to within 200 bp. We annotated 25 experimentally reported binding sites, 10 for Mef-2, 7 for TEF, and 8 for SRF. Besides, by using the weight matrices for the five TFs (figure 1A in ref. 28), we scanned the 29 sequences and detected 19, 12, 23, 13, and 20 putative sites for the five TFs above at a false-positive error rate of 5E-4, which provided estimates for the numbers of target sites. Two data sets were constructed by adding 10 and 40 upstream sequences (200 bp each) randomly extracted from the ensembl database to the 29 positive training sequences. We tested how resistant the algorithm was to the presence of noisy sequences (those random upstreams). CisModule was applied to these data sets with K = 5 and l = 150. We also applied MEME and BP to the same data sets to output the top 20 motifs they could find. The logo plots for the motifs found by CisModule are shown in Fig. 5, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site.

It turns out that all three algorithms successfully found the Sp-1 motif (GC box). We focus our comparison on the other four factors. The results are summarized in Table 4, where we tabulate among all the predicted sites from each method the number of reported sites (n1), the number of putative sites in positive sequences that do not overlap with reported sites (n2), and the number of false-positive sites in random sequences (n3). The nature of putative sites (n2) is ambiguous because they may be unreported binding sites or false positives. For Mef-2 and TEF, CisModule found more reported sites and usually fewer false-positive sites for different cases. Furthermore, CisModule was the only algorithm that discovered the SRF motif (with a phase shift of two bases). None of the methods found the motif for Myf. From the summary in Table 4 we see that the sensitivity of CisModule in discovering reported sites (n1) is 88% (22 of 25) and 68% (17 of 25) for the data sets with 10 and 40 random sequences, respectively, which is much higher than the sensitivity of the other two methods. CisModule is also most resistant to the mixed random sequences with the fewest false-positive predictions (n3). These results confirm the notion that module sampling based on the combinatorial effects of several motifs is more stable than sampling each motif individually. Taking the data set with 40 random sequences as an example, we found that 54% of our predicted modules were from the 29 positive sequences, but only 34% of the output sites predicted by MEME were from the positive sets. The predicted modules that do not overlap with positive sequences are most likely false positives, but the possibility exists that some might be unreported modules.

Table 4. Comparison of CisModule (CMD), MEME, and BP for muscle-specific data sets.

| Algorithm | Mef-2 (10/19) n1/n2/n3 | TEF (7/20) n1/n2/n3 | SRF (8/13) n1/n2/n3 | Summary (25/52) n1/n2/n3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BP | 2/14/3 | 3/18/5 | — | 5/32/8 |

| MEME | 8/17/7 | 1/5/1 | — | 9/22/8 |

| CMD | 9/14/5 | 7/14/0 | 6/7/0 | 22/35/5 |

| MEME | 2/9/19 | 1/3/2 | — | 3/12/21 |

| CMD | 8/16/15 | 3/10/1 | 6/7/0 | 17/33/16 |

The TF names are followed by the numbers of experimentally reported sites and scanned-based sites in the sequences. n1/n2/n3 are defined in the text. (–indicates that the algorithm fails to find the motif.) The upper and lower halves correspond to the results for the data sets with 10 and 40 random sequences mixed, respectively. For the data set with 40 random sequences, BP failed to find any of the three motif patterns and thus is not listed in the table.

Discussion

The HMx model assumes that TFBSs are located within some relatively short sequence segments, the CRMs. The benefit of this model is that it captures the spatial correlation between different binding sites. It is clear that the more tightly clustered the motif sites, the more information the HMx model gains. Based on the model, a Bayesian module sampler, CisModule, is developed to simultaneously infer the motif modules and the binding sites for a set of TFs by means of the Gibbs sampling approach. The module detection step utilizes the combination of several motifs, which significantly enhances the sensitivity of the method.

As is true for all de novo motif discovery algorithms, CisModule may sometimes be trapped in local modes. To reduce this possibility, multiple trials are often needed. If some prior information is available for a particular data set, we can use it to initiate CisModule. For example, if we know that the sequences are controlled by one TF, and we are interested in finding the binding sites for this TF and its cooperating TFs, the weight matrix for the known TF can be used to prescribe more specific prior distributions. This will lead to faster convergence to the correct motif patterns.

An interesting future work would be to incorporate the information from comparative genomics into CisModule. Greater prior probabilities for modules and sites can be assigned to the regions that are highly conserved across species of appropriate evolutionary distances. This will effectively reduce the false-positive discovery and is especially important for higher organisms, whose upstream sequences are long and regulatory mechanisms are complex. Finally, the model presented here should be regarded as a first step to the development of realistic models for de novo motif-module discovery. The HMx model captures the colocalization tendency of cooperating TFBSs but not their order or precise spacing. It is possible that additional refinements to the model may further enhance its utility.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant (to W.H.W.).

Appendix A: Conditional Posterior Distributions for Parameters

Given M and A, we align the binding sites for each motif and calculate its wk × 4 count matrix Nk (k = 1,..., K). Then each Θk can be sampled from the product Dirichlet distribution with parameter Nk + βk. We denote the number of modules by |M|, the number of sites for the kth motif by |Ak|, and  is the total length of nonsite background segments within the modules. Let |A| = [|A0|, |A1|,..., |AK|], then [q|M, A] follows Dir(|A| + α). Similarly, [r|M] = Beta(|M| + a, L - l|M| + b), where L is the total length of S. The motif widths can be updated by a Metropolis step similar to that used in ref. 16.

is the total length of nonsite background segments within the modules. Let |A| = [|A0|, |A1|,..., |AK|], then [q|M, A] follows Dir(|A| + α). Similarly, [r|M] = Beta(|M| + a, L - l|M| + b), where L is the total length of S. The motif widths can be updated by a Metropolis step similar to that used in ref. 16.

Appendix B: Recursions for Forward Summation

Let fn(Ψ) = P(x[1,n]|Ψ) be the probability for the partial sequence x[1,n] given that xn is either a background or the end of a module, then P(S|Ψ) = fL(Ψ). Let h(i, m) be the probability of observing x[i,m] given that it is within a module. Then we have

|

[5] |

|

[6] |

where P(xn|xn-1, θ0) is the background transition probability. The initial conditions are f0(Ψ) = 1 and fn(Ψ) = 0 for n < 0. To calculate h(i, m), we need to sum over all possible site arrangements within x[i,m],

|

[7] |

where P(x[m-wk+1,m]|Θk) is the probability of generating x[m-wk+1,m] from the kth motif model. The initial conditions of Eq. 7 are h(i, i - 1) = 1 and h(i, m) = 0 for m < i - 1. This is the same recursion we use in motif site detection. It is still quite time-consuming in the module detection step to calculate h(i, i + l - 1) exactly for each possible module starting position i. Because sites are independently distributed within modules, we approximate this probability by [h(1, i + l - 1)]/[h(1, i - 1)]. Thus, only one recursive summation is needed for each sequence in the module-sampling step, which reduces the computational complexity to O(KL). We have observed in simulations that this approximation works well and, on average, the predicted motif sites using the approximation showed 95% overlapping with the results using the exact summation.

Appendix C: Importance Sampling for Calculating P(S|HK) in Eq. 4

The marginal sequence likelihood under HK is

|

[8] |

After summing over M and A by the recursive methods described in Appendix B, we use importance sampling to calculate the integral in Eq. 8 with a trial distribution Q(Ψ), a diffuse version of P(Ψ|S, M̂, Â, HK), where M̂ and  are our predictions based on their marginal posterior distributions. More specifically, in Q(Ψ), Θk ∼ ProductDirichlet(λN̂k + βk), where N̂k is the count matrix based on Âk, q ∼ Dir(λ|Â| + α), r ∼ Beta(λ|M| + a, λ(L - l|M|) + b), and λ = 0.25∼0.5. Consequently, our estimate for P(S|HK) is:

|

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: TF, transcription factor; TFBS, TF-binding site; CRM, cis-regulatory module; HMx, hierarchical mixture; PWM, position-specific weight matrix; BP, BioProspector; Bcd, Bicoid; Hb, Hunchback; Kr, Krüppel.

References

- 1.Galas, D. J. & Schmitz, A. (1978) Nucleic Acids Res. 5, 3157-3170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fried, M. & Crothers, D. M. (1981) Nucleic Acids Res. 9, 6505-6525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garner, M. M. & Revzin, A. (1981) Nucleic Acids Res. 9, 3047-3060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stormo, G. D. & Hartzell, G. W. (1989) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86, 1183-1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hertz, G. Z. & Stormo, G. D. (1999) Bioinformatics 15, 563-577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lawrence, C. E. & Reilly, A. A. (1990) Proteins 7, 41-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bailey, T. L. & Elkan, C. (1994) Proc. Int. Conf. Intell. Syst. Mol. Biol. 2, 28-36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lawrence, C. E., Altschul, S. F., Boguski, M. S., Liu, J. S., Neuwald, A. N. & Wootton, J. (1993) Science 262, 208-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu, J. S., Neuwald, A. N. & Lawrence, C. E. (1995) J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 90, 1156-1170. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roth, F. P., Hughes, J. D., Estep, P. W. & Church, G. M. (1998) Nat. Biotechnol. 16, 939-945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu, X., Brutlag, D. L. & Liu, J. S. (2001) Pac. Symp. Biocomput. 6, 127-138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou, Q. & Liu, J. S. (2004) Bioinformatics 20, 909-916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sinha, S. & Tompa, M. (2002) Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 5549-5560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hampson, S., Kibler, D. & Baldi, P. (2002) Bioinformatics 18, 513-528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bussemaker, H. J., Li, H. & Siggia, E. D. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 10096-10100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gupta, M. & Liu, J. S. (2003) J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 98, 55-66. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu, J. S., Neuwald, A. N. & Lawrence, C. E. (1999) J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 94, 1-15. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson, W., Rouchka, E. C. & Lawrence, C. E. (2003) Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3580-3585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bussemaker, H. J., Li, H. & Siggia, E. D. (2001) Nat. Genet. 27, 167-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pilpel, Y., Sudarsanam, P. & Church, G. M. (2001) Nat. Genet. 29, 153-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Conlon, E. M., Liu, X. S., Lieb, J. D. & Liu, J. S. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 3339-3344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang, T. & Stormo, G. D. (2003) Bioinformatics 19, 2369-2380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kellis, M., Patterson, N., Endrizzi, M., Birren, B. & Lander, E. S. (2003) Nature 423, 241-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yuh, C. H., Bolouri, H. & Davidson, E. H. (1998) Science 279, 1896-1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loots, G. G., Locksley, R. M., Blankespoor, C. M., Wang, Z. E., Miller, W., Rubin, E. M. & Franzer, K.A. (2000) Science 288, 136-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berman, B. P., Nibu, Y., Pfeiffer, B. D., Tomancak, P., Celniker, S. E., Levine, M., Rubin, G. M. & Eisen, M. B. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 757-762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Banerjee, N. & Zhang, M. Q. (2003) Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 7024-7031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wasserman, W. W. & Fickett, J. W. (1998) J. Mol. Biol. 278, 167-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krivan, W. & Wasserman, W. W. (2001) Genome Res. 11, 1559-1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frith, M. C., Hansen, U. & Weng, Z. (2001) Bioinformatics 17, 878-889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sinha, S., van Nimwegan, E. & Siggia, E. D. (2003) Proc. Int. Conf. Intell. Syst. Mol. Biol. 11, 292-301. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lifanov A. P., Makeev, V. J., Nazinna, A. G. & Papasenko, D. A. (2003) Genome Res. 13, 579-588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Makeev, V. J., Lifanov A. P., Nazinna, A. G. & Papasenko, D. A. (2003) Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 6016-6026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schena, M., Shalon, D., Davis, R. W. & Brown, P. O. (1995) Science 270, 467-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Velculescu, V. E., Zhang, L., Vogelstein, B. & Kinzler, K. W. (1995) Science 270, 484-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wasserman, W. W., Palumbo, M., Thompson, W., Fickett, J. W. & Lawrence, C. E. (2000) Nat. Genet. 26, 225-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Loots, G. G., Ovcharenko, I., Pachter, L., Dubchak, I. & Rubin, E. M. (2002) Genome Res. 12, 832-839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Geman, S. & Geman, D. (1984) IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 6, 721-741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tanner, M. A. & Wong, W. H. (1987) J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 82, 528-540. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gelfand, A. E. & Smith, A. F. M. (1990) J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 85, 398-409. [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Ginkel, P. R., Hsiao, K. M. & Farnham, P. J. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 18367-18374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wingender, E., Chen, X., Hehl, R., Karas, H., Liebich, I., Matys, V., Meinhardt, T., Pruss, M., Reuter, I. & Schacherer, F. (2000) Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 316-319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schneider, T. D. & Stephens, R. M. (1990) Nucleic Acids Res. 18, 6097-6100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sandelin, A., Alkema, W., Engström, P., Wasserman, W. & Lenhard, B. (2004) Nucleic Acids Res. 32, D91-D94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lenhard, B. & Wasserman, W. (2002) Bioinformatics 18, 1135-1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.