Abstract

γ-Hexachlorocyclohexane (γ-HCH) is a recalcitrant man-made chlorinated pesticide. Here, the complete genome sequences of four γ-HCH-degrading sphingomonad strains, which are most unlikely to have been derived from one ancestral γ-HCH degrader, were compared. Together with several experimental data, we showed that (i) all the four strains carry almost identical linA to linE genes for the conversion of γ-HCH to maleylacetate (designated “specific” lin genes), (ii) considerably different genes are used for the metabolism of maleylacetate in one of the four strains, and (iii) the linKLMN genes for the putative ABC transporter necessary for γ-HCH utilization exhibit structural divergence, which reflects the phylogenetic relationship of their hosts. Replicon organization and location of the lin genes in the four genomes are significantly different with one another, and that most of the specific lin genes are located on multiple sphingomonad-unique plasmids. Copies of IS6100, the most abundant insertion sequence in the four strains, are often located in close proximity to the specific lin genes. Analysis of the footprints of target duplication upon IS6100 transposition and the experimental detection of IS6100 transposition strongly suggested that the IS6100 transposition has caused dynamic genome rearrangements and the diversification of lin-flanking regions in the four strains.

Keywords: xenobiotics, evolution, sphingomonads, genome, mobile genetic elements

1. Introduction

In the early 20th century, rapid development in the chemical industry led to the production and wide use of numerous anthropogenic chemicals. Because they are often recalcitrant in the environment and toxic to humans and ecosystems, they have caused serious environmental problems.1–3 Many bacterial strains capable of degrading man-made xenobiotic compounds have been isolated and characterized.4–9 Such strains are thought to have evolved to degrade xenobiotics within relatively short periods. However, with the exception of a few speculative examples, the evolutionary processes of these bacterial strains remain largely unknown.5,10–13 γ-Hexachlorocyclohexane (γ-HCH; also known as γ-BHC or lindane) is a completely man-made chlorinated pesticide that has caused serious environmental problems due to its toxicity and long persistence in upland soils.7,14,15 Only 60 years after the first release of γ-HCH into the environment, a number of bacterial strains that aerobically degrade γ-HCH have been isolated from geographically distant locations around the world.7 An archetypal γ-HCH-degrading strain, Sphingobium japonicum UT26, was isolated from an upland experimental field to which γ-HCH had been applied once a year for 12 years, and its aerobic γ-HCH degradation pathway (Fig. 1) and genome organization have been intensively studied.16–19 Recently, many draft genome sequences of other HCH (including not only γ-HCH but also other HCH isomers) degraders and their related but non-HCH-degrading strains were determined, and their comparative analyses have been published.20,21 These studies provided us some important primary information on the evolution of HCH-degraders with the involvement of plasmids and insertion sequences (ISs). However, the more detailed information (e.g. which and how plasmids/ISs are involved in the evolution of HCH-degraders) remains unclear.

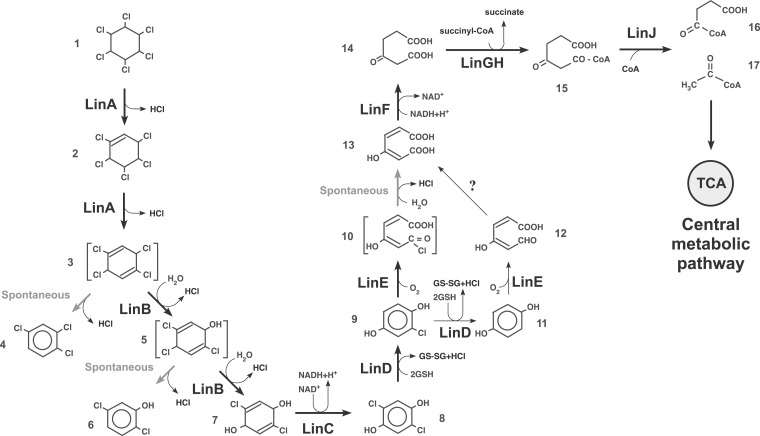

Figure 1.

Degradation pathway of γ-HCH in UT26. Compounds: 1, γ-HCH; 2, γ-pentachlorocyclohexene; 3, 1,3,4,6-tetrachloro-1,4-cyclohexadiene; 4, 1,2,4-trichlorobenzene; 5, 2,4,5-trichloro-2,5-cyclohexadiene-1-ol; 6, 2,5-dichlorophenol; 7, 2,5-dichloro-2,5-cyclohexadiene-1,4-diol; 8, 2,5-dichlorohydroquinone; 9, chlorohydroquinone; 10, acylchloride; 11, hydroquinone; 12, γ-hydroxymuconic semialdehyde; 13, maleylacetate; 14, β-ketoadipate; 15, 3-oxoadipyl-CoA; 16, succinyl-CoA; 17, acetyl-CoA. TCA, citrate/tricarboxylic acid cycle. Note that the compounds 4 and 6 are dead-end products. Spontaneous and non-enzymatic reaction is indicated by grey arrows. The reaction marked with ‘?’ has not been identified. Compounds in parentheses have not been directly detected.

In this study, to gain further insight into the functional evolution of bacterial genomes, the complete genome sequences of three other γ-HCH-degraders, Sphingomonas sp. MM-1,22,23 Sphingobium sp. MI1205,24,25 and Sphingobium sp. TKS,26 were determined. On the basis of our comparison of the complete genome sequences of these three strains and UT26, in association with several supporting experimental data, the evolution of γ-HCH-degrading bacterial strains is discussed.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture conditions

Strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table S1. All sphingomonad (the collective name of Sphingomonas, Sphingobium, Novosphingobium, Sphingopyxis, and their related genera) 27 strains were cultured at 30°C in 1/3LB medium or 1/10W minimal medium.24 If needed, antibiotics were added at the following concentrations: tetracycline (Tc) 20 μg/ml, nalidixic acid (Nal) 100 μg/ml, and kanamycin (Km) 50 μg/ml for UT26; Tc 5 μg/ml, Nal 100 μg/ml, gentamycin (Gm) 2 μg/ml, and Km 50 μg/ml for MM-1; Tc 2 μg/ml, Nal 100 μg/ml, and Km 50 μg/ml for TKS; and Tc 2 μg/ml, Nal 100 μg/ml, and Km 50 μg/ml for MI1205. Escherichia coli DH5α for genetic manipulation was grown at 37°C in LB.28 If needed, antibiotics were added at the following concentrations: Tc 20 μg/ml, Gm 20 μg/ml, and Km 50 μg/ml. The solid media were prepared by the addition of 1.5% agar.

2.2. Construction of plasmids and strains

The 3.6-kb region containing the MM-1 linKbLbMbNb genes was amplified by PCR using the primer set of MM_linKLMN_F and MM_linKLMN_R (Supplementary Table S2), and the amplified fragment was cloned into a broad-host-range vector, pKS13P,29 under the linA constitutive promoter30 to generate pKSR1020. The whole region of the linFb gene of strain TKS was amplified by PCR using the primer set of TKS_MAR_F_Hind and TKS_MAR_R_Bam (Supplementary Table S2), digested with BamHI and HindIII, and cloned into the corresponding sites of pBBR1-MCS231 to generate pBLFb. To disrupt the genomic linFb gene in TKS, an internal part of linFb was amplified by PCR using the primer set of TKS_MAR_single_F_Eco and TKS_MAR_single_R_Hind (Supplementary Table S2), digested with EcoRI and HindIII, and cloned into the corresponding sites of pEX18Gm.32 The resultant plasmid pEDLFb was introduced into TKS by electroporation to select the Gm-resistant transformants. Subsequent PCR analysis of one such transformant (TKSdLFb) confirmed that its genomic linFb gene was disrupted by reciprocal homologous recombination through the single crossover-mediated integration of pEDLFb (Supplementary Fig. S1).

2.3. DNA manipulations and Sanger sequencing

Established methods were employed for the preparation of plasmids and genomic DNAs, their digestion with restriction endonucleases, ligation, and agarose gel electrophoresis, and the transformation of E. coli cells.28,33 Electroporation of sphingomonad strains was performed as described previously.34 PCR for cloning was performed with KOD-Plus DNA polymerase (TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan). The primers used are listed in Supplementary Table S2. The Sanger sequencing was performed using an ABI PRISM 3130xl sequencer and ABI Prism Big Dye Terminator v3.1 Kit (Applied Biosystems).

2.4. Genome sequencing and annotation analyses

Fragment reads of genomic DNA of MM-1, MI1205, and TKS were obtained by the Roche 454 and Illumina HiSeq 2000 sequencing systems, and were assembled using the Newbler programme (Roche). The GenoFinisher and AceFileViewer programmes were used to finish the sequencing completion.35 More detailed information for these procedures have been published elsewhere.23,25,26 Sequencing gap regions were amplified by PCR using KOD FX (TOYOBO) or Ex Taq (TaKaRa) by using the total DNA of the respective strains as templates, and the resultant DNA fragments were sequenced using primers for PCR amplification. Pulsed-field-gel electrophoresis was also performed as described previously36 to support the whole genome sequencing data of MI1205 and TKS (data not shown). The annotation data of the complete genome sequences were obtained by PGAAP (Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/annotation_prok/; 22 August 2016, date last accessed), and was curated with the dedicated software bundled in the GenomeMatcher programme (http://www.ige.tohoku.ac.jp/joho/gmProject/gmhome.html; 22 August 2016, date last accessed)37 as well as by consulting the MiGAP auto-annotation system (Microbial Genome Annotation Pipeline, http://www.migap.org/; 22 August 2016, date last accessed).

2.5. Computational analyses of sequence data

The nucleotide and protein sequences were analysed using the Genetyx programme version 13–18 (Genetyx Corp., Tokyo, Japan). Homology searches were performed using the BLAST programmes available at the National Center for Biotechnology Information website (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/; 22 August 2016, date last accessed) with the default parameters. Venn diagram was depicted using the result obtained by BLASTClust analysis (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/executables/; 22 August 2016, date last accessed)38 for all predicted open reading frames (ORFs) of the four γ-HCH degraders with a parameter set ‘-p T -L .6 -b T -S 60 -a 24’. Comparative analyses of DNA sequences were performed by GenomeMatcher using BLASTN with a parameter set ‘-F F -W 21 -e 0.01’. Conserved motifs and repeat sequences were searched by GenomeMatcher. All neighbour-joining phylogenetic trees shown in this study were constructed using MAFFT programme (http://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/software/; 22 August 2016, date last accessed)39 and visualized by NJplot software (http://pbil.univ-lyon1.fr/software/njplot.html; 22 August 2016, date last accessed).40 Transposable elements were identified by analyses of regions containing putative transposase genes, i.e. mutual BLASTN analysis with a parameter set ‘-F F -W 21 -e 0.01’and searches for inverted and direct repeats using Dot Match mode of GenomeMatcher. For detection of candidate ORFs relevant to metabolisms of aromatic compounds, all ORFs obtained from each genome were BLASTP-searched with parameters ‘-e 1e-5 -b 5 -F F’ and threshold identity ≥50%, query and reference sequence coverage ≥50% against an in-house database for the enzymes for degradation of aromatic compounds.41

2.6. Entrapment of transposable elements

pGEN500, an entrapment plasmid vector of transposable elements,42 was introduced into UT26, MM-1, TKS, and MI1205 by electroporation or mating using E. coli S17-1, and the cells carrying pGEN500 were selected on the 1/3LB agar plate containing Tc. The pGEN500-containing strains were thereafter plated on 1/3LB agar containing Tc and 10% sucrose (w/v) at 30°C. The colonies formed on the plates were analysed for their resident pGEN500 derivatives. Such derivatives with enlarged sizes were postulated to be formed by the insertion of endogenous transposable elements in the sacB gene on pGEN500. The insertion event in each derivative was investigated by PCR using the multiple pairs of primers listed in Supplementary Table S2, and the insert was sequenced by the Sanger method.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Complete genome sequences of three γ-HCH-degrading sphingomonad strains

Most of the aerobic γ-HCH-degrading bacterial strains that have been critically analysed at the genetic level are sphingomonads that belong to Alphaproteobacteria.7 We have previously published an article describing our detailed analysis of the UT26 genome.18 In this study, the complete genome sequences of three other γ-HCH-degrading strains, Sphingomonas sp. MM-1,22,23 Sphingobium sp. MI1205,24,25 and Sphingobium sp. TKS,26 were determined.

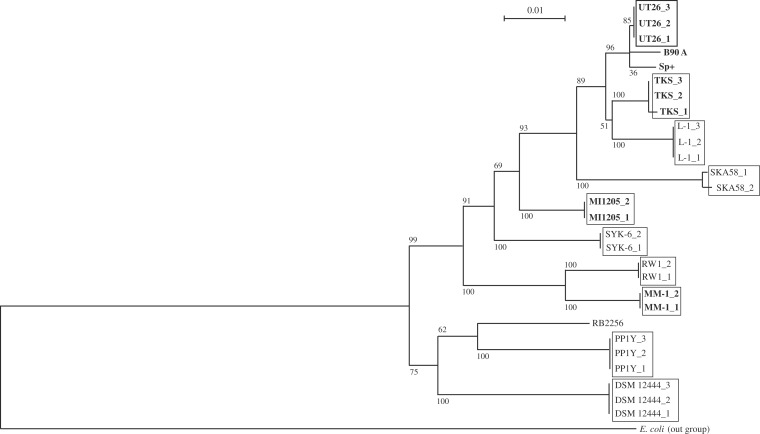

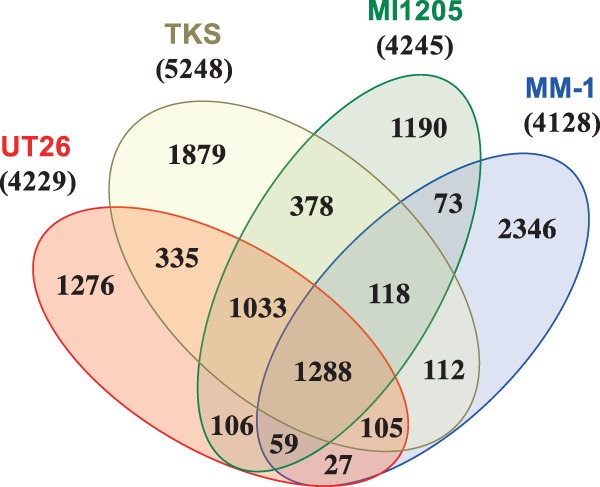

The basic genome organizations of the four γ-HCH-degrading strains isolated from different geographical areas are summarized in Table 1. Comparative analysis of the 16S rRNA genes indicated that these four γ-HCH-degrading strains are phylogenetically diverse among related sphingomonad strains (Fig. 2). All predicted ORFs of these four strains (19,312) were clustered into 10,325 ORF clusters. Figure 3 summarizes the result as a Venn diagram that shows the numbers of shared and unique ORF clusters among the four strains; these four strains each have 1,190–2,346 unique ORF clusters, but share only 1,288 ones. This observation supports the phylogenetic divergence of the four γ-HCH degraders. These results also strongly suggest that the four degraders independently acquired γ-HCH-degradation ability, and thus it is unlikely that the four strains have been derived from one ancestral γ-HCH-degrader.

Table 1.

Genome organization of four γ-HCH-degrading sphingomonad strains

| Strain name | Isolated site | Source type | Replicon | Length (bp) | Number of | Acc no. | Replicon typea | lin genesb | Reference for strain | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rrn operon | ORF | IS6100 | |||||||||

| S. japonicum UT26 | Tokyo, Japan | Soil artificially polluted | Chromosome 1 | 3,514,822 | 1 | 3,529 | 5 | AP010803 | Chr | linA, linB, linC, linKLMN | 18 |

| with γ−HCH | Chromosome 2 | 681,892 | 2 | 589 | 2 | AP010804 | UT26_Chr 2 | linF, linGHIJ, linEb | |||

| pCHQ1 | 190,974 | 0 | 224 | 4 | AP010805 | pCHQ1 | linRED | ||||

| pUT1 | 31,776 | 0 | 44 | 2 | AP010806 | pUT1 | — | ||||

| pUT2 | 5,398 | 0 | 8 | 0 | AP010807 | pUT2 | — | ||||

| total | 4,424,862 | 3 | 4,394 | 13 | |||||||

| Sphingomonas sp. MM-1 | Lucknow, India | Soil polluted | Chromosome | 4,054,833 | 2 | 3,801 | 0 | CP004036 | Chr | linKbLbMbNb | 22 |

| with HCH isomers | pISP0 | 275,840 | 0 | 251 | 1 | CP004037 | pCHQ1 | linF, linGHIJ | |||

| pISP1c | 172,140 | 0 | 174 | 7 | CP004038 | UT26_Chr 2/pISP4 | linA, linC, linF' | ||||

| pISP2 | 53,841 | 0 | 52 | 2 | CP004039 | pUT1 | — | ||||

| pISP3 | 43,776 | 0 | 44 | 1 | CP004040 | pISP3 | linRED | ||||

| pISP4 | 33,183 | 0 | 39 | 4 | CP004041 | pISP4 | linB, linC, linF' | ||||

| Total | 4,633,613 | 2 | 4,361 | 15 | |||||||

| Sphingobium sp. TKS | Kyushu, Japan | Sediment polluted | Chromosome 1c | 4,249,857 | 1 | 4,172 | 7 | CP005083 | Chr/UT26_Chr 2 | linB, linC, linF', linFb, linKLMN | This study |

| with HCH isomers | Chromosome 2 | 989,120 | 2 | 843 | 0 | CP005084 | UT26_Chr 2 | linGHIJ_homologue | |||

| pTK1c | 520,614 | 0 | 470 | 6 | CP005085 | UT26_Chr 2/pCHQ1 | — | ||||

| pTK2 | 195,308 | 0 | 182 | 1 | CP005086 | pTK2 | — | ||||

| pTK3c | 87,635 | 0 | 92 | 8 | CP005087 | pISP4/pTK3_type 1/pTK3_type 2 | linB, linC, linF' | ||||

| pTK4c | 75,938 | 0 | 86 | 6 | CP005088 | pUT1/pISP4 | linA, linC | ||||

| pTK5 | 53,908 | 0 | 76 | 0 | CP005089 | pLB1 | — | ||||

| pTK6 | 34,300 | 0 | 35 | 1 | CP005090 | pISP3 | linRED | ||||

| pTK7 | 9,585 | 0 | 12 | 0 | CP005091 | pTK7 | — | ||||

| pTK8 | 7,223 | 0 | 11 | 0 | CP005092 | pTK8 | — | ||||

| pTK9 | 5,391 | 0 | 8 | 0 | CP005093 | pUT2 | — | ||||

| total | 6,228,879 | 3 | 5,987 | 29 | |||||||

| Sphingobium sp. MI1205 | Miyagi, Japan | Soil polluted | Chromosome 1 | 3,351,250 | 1 | 3,285 | 0 | CP005188 | Chr | linKLMN | 24 |

| with HCH isomers | Chromosome 2 | 567,154 | 1 | 516 | 0 | CP005189 | UT26_Chr 2 | — | |||

| pMI1 | 292,135 | 0 | 299 | 7 | CP005190 | UT26_Chr 2 | linB, linC, linRED, linEb, linF, linF'', linGHIJ | ||||

| pMI2c | 287,488 | 0 | 323 | 7 | CP005191 | pUT1/UT26_Chr 2 | linA, linRD | ||||

| pMI3c | 88,374 | 0 | 102 | 7 | CP005192 | pLB1/pISP4 | linB, linC, linF'' | ||||

| pMI4c | 32,974 | 0 | 45 | 3 | CP005193 | pISP3/pISP4 | linRED | ||||

| total | 4,619,375 | 2 | 4,570 | 24 | |||||||

aSee Table 3

blinF′ and linF″ are probably pseudogenes (see Supplementary Fig. S2).

cReplicons having more than one rep genes.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree of 16S rRNA genes of sphingomonad strains. Neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree of the conserved sites in 16S rRNA genes of 13 sphingomonad strains, S. japonicum UT26S (UT26_1, SJA_C1-r0010; UT26_2, SJA_C2-r0010; UT26_3, SJA_C2-r0040), Sphingobium indicum B90A (B90A, NR_042943), Sphingobium francense Sp+ (Sp+, NR_042944), Sphingobium sp. TKS (TKS_1, Chr1_62351_63846; TKS_2, Chr2_117006_118503; and TKS_3, Chr2_376042_377539_c), Sphingobium chlorophenolicum L-1 (L-1_1, Sphch_R0043; L-2_2, Sphch_R0058; L-1_3, Sphch_R0067), Sphingomonas sp. SKA58 (SKA58_1, SKA58_r00366; SKA58_2, SKA58_r18278), Sphingobium sp. MI1205 (MI1205_1, Chr1_64638_66133; MI1205_2, Chr2_561355_562850_c), Sphingobiums sp. SYK-6 (SYK6_1, SLG_r0030; SYK6_2, SLG_r0060), Sphingomonas wittichii RW1 (RW1_1, Swit_R0031; RW1_2, Swit_R0040), Sphingomonas sp. MM-1 (MM-1_1, Chr_1791835_1793331_c; MM-1_2, Chr_2084177_2085673_c), Sphingopyxis alaskensis RB2256 (RB2256, Sala_R0048), Novosphingobium sp. PP1Y (PPY_1, PP1Y_AR03; PPY_2, PP1Y_AR23; PPY_3, PP1Y_AR65), and N. aromaticivorans DSM 12444 (DSM_1, Saro_R0065; DSM_2, Saro_R0059; DSM_3, Saro_R0053) was constructed. 16S rRNA gene (rrsE: gene ID 7437018) of E. coli str. K-12 substr. W3110 (E. coli) was used as an out-of-group sequence. Bootstrap values calculated from 1,000 resampling using neighbour-joining are shown at the respective nodes. Length of lines reflects relative evolutionary distances among the sequences. Sphingomonas sp. SKA58 should be Sphingobium sp. SKA58 on the basis of comprehensive 16S rRNA gene analysis. However, we used ‘Sphingomonas’ for the strain according to the database in order to avoid confusion. γ-HCH degraders are bolded.

Figure 3.

Venn diagram showing the number of shared and unique ORF clusters of four γ-HCH-degrading sphingomonad strains. Total ORFs (19,312) of the four strains were clustered into 10,325 ORF clusters by BLASTClust analysis. Numbers of total ORF clusters of these four strains are shown in parentheses under the strain names.

In addition to the genes for γ-HCH degradation (see below), putative genes for the degradation of various aromatic compounds, toluene/phenol, chlorophenol, anthranilate, and homogentisate, reside in the UT26 genome.18 These genes constitute four clusters for the degradation of the respective compounds, and each cluster contains all the genes necessary for the conversion of each compound to the metabolites in the central metabolic pathway, strongly suggesting that UT26 is able to utilize these compounds. Similarly, several putative genes for the degradation of aromatic compounds were found in the MM-1, MI1205, and TKS genomes (Supplementary Table S3). The potential of the four γ-HCH degraders for the degradation of aromatic compounds was estimated more comprehensively by BLASTP search of all their ORFs against our previously constructed in-house database which consists of enzymes for the degradation of aromatic compounds,41 and the result was summarized in Supplementary Table S4. The numbers of ORFs potentially involved in the degradation of aromatic compounds in the four strains (62, 46, 27, and 25 for TKS, UT26, MI1205, and MM-1, respectively) are much smaller than those in versatile recalcitrant pollutant degraders, Cupriavidus necator JMP134,43,44 and Burkholderia xenovorans LB40045,46 (149 and 135 for JMP134 and LB400, respectively). Especially, those in UT26, MI1205, and MM-1 are even smaller than those in typical metabolically versatile soil bacterial strains Burkholderia multivorans ATCC 1761647–50 and Pseudomonas putida KT244051 (73 and 62 for KT2440 and ATCC 17616, respectively). These results indicate that our sphingomonad strains are ‘specialists’ for γ-HCH degradation, but not ‘generalists’ for the degradation of many recalcitrant compounds.

3.2. The lin genes for γ-HCH utilization

UT26 converts γ-HCH to β-ketoadipate via reactions catalysed by dehydrochlorinase (LinA), haloalkane dehalogenase (LinB), dehydrogenase (LinC), reductive dechlorinase (LinD), ring-cleavage dioxygenase (LinE), and maleylacetate reductase (MAR) (LinF); β-ketoadipate is thereafter converted to succinyl-CoA and acetyl-CoA by succinyl-CoA:3-oxoadipate CoA transferase (LinGH) and β-ketoadipyl CoA thiolase (LinJ), respectively (Fig. 1).16,18 In addition to genes for these catabolic enzymes and their regulatory genes (linR for linDE and linI for linGHJ),18,52 the linKLMN genes encoding a putative ABC-transporter system are necessary for the γ-HCH utilization in UT26.29 The linA, linB, linC, and linF genes, and the linRED, linGHIJ, and linKLMN clusters are dispersed on the UT26 genome.18 Since the β-ketoadipate pathway is often used by environmental bacterial strains,53 the lin genes for the conversion of γ-HCH to β-ketoadipate (linA to linF) are peculiar to the γ-HCH-degrading pathway. In particular, the linA gene is unique because it does not show significant similarity to any sequences in the databases except for the almost identical (>90% identity) linA genes from other bacterial strains and metagenomes.7,16

The MM-1, MI1205, and TKS genomes carry linA, linB, and linC genes and a linRED cluster that are almost identical (>98% identity at the DNA level) to those of UT26 (Table 2). The former two strains additionally carry a linF gene and linGHIJ cluster that are almost identical (>98% identity at the DNA level) to those in UT26, strongly suggesting that γ-HCH is degraded in these two strains by the same pathway as in UT26 (Fig. 1). The last strain lacks the linFUT26 and linGHIJUT26 cluster for maleylacetate metabolism (Fig. 1). Although two copies of the truncated version of linF (named linF′) (Supplementary Fig. S2) are present in the TKS genome, linF' was assumed not to encode functional MAR, since linF' misses more than one half of the intact linF gene (Supplementary Fig. S2). TKS instead carries another putative gene, designated linFb, on Chr1. Although LinFb showed only 49% identity to LinFUT26 (Table 2), it showed much higher similarity with other known MAR proteins, such as TfdF from Bordetella petrii,54 Achromobacter denifrificans,55 Burkholderia sp. M701 (Acc no. YP_008864525), and Comamonas testosteroni56 (83,78, 78, and 71%, respectively). Interestingly, Sphingobium sp. HDIPO4, a recently isolated HCH degrader, has the identical linFb gene, although its start codon is annotated at a position different from that in TKS. 57 To clarify the LinFb function, its gene in TKS was disrupted (Supplementary Fig. S1). The resultant strain did not grow on a minimal agar plate supplemented with γ-HCH as a sole source of carbon and energy, and this growth defect was reversed by the supply of the intact linFb gene (Supplementary Fig. S3). In addition, the γ-HCH utilization defect of UT1023d, a linF mutant of UT26,34 was reversed by the supply of the linFb gene (data not shown). These results clearly demonstrated that the linFb encodes a MAR that is functional for the γ-HCH utilization. Although the linGHIJUT26 cluster was not found in the TKS genome, many homologues of linG, linH, and linJ were found (Supplementary Table S5). Among these homologues, one set of linGH homologues is located just downstream of linFb on Chr1TKS (Supplementary Fig. S4A) and only one set of linGHIJ homologues exists as a cluster on Chr2TKS (Supplementary Fig. S4B). Some of these homologues may be functional for the β-ketoadipate metabolism, and this experimental confirmation is necessary. These results strongly suggested that γ-HCH is also degraded in TKS by the same pathway as in UT26 (Fig. 1).

Table 2.

lin genes of four γ−HCH-degrading sphingomonad strains

| Geneb | Function | UT26 | MM-1 | TKS | MI1205 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A.A. residues | Locationa | A.A. residues | Locationa | Identity (%) to that of UT26 | A.A. residues | Locationa | Identity (%) to that of UT26 | A.A. residues | Locationa | Identity (%) to that of UT26 | ||||||

| A.A. | Nucleotide | A.A. | Nucleotide | A.A. | Nucleotide | |||||||||||

| linA | Dehydrochlorinase | 156 | Chr1_1860686-1861156_c | 156 | pISP1_13547_14017 | 98 (153/156) | 98 (466/471) | 156 | pTK4_18583_19053 | identical | 156 | pMI2_260065_260535_c | identical | |||

| linB | Halidohydrolase | 296 | Chr1_1966541-1967431 | 296 | pISP4_18957_19847_c | 98 (293/296) | 99 (883/891) | 296 | Chr1_230419_231309 | 97 (290/296) | 99 (883/891) | 296 | pMI1_179020_179910_c | 98 (292/296) | 99 (886/891) | |

| 296 | pTK3_34952_35842 | 97 (290/296) | 99 (883/891) | 296 | pMI3_39099_39989 | 97 (289/296) | 99 (883/891) | |||||||||

| 296 | pMI3_41282_42172 | 97 (289/296) | 99 (883/891) | |||||||||||||

| linC | Dehydrogenase | 250 | Chr1_566609-567361_c | 250 | pISP1_147367_148119 | 99 (249/250) | 99 (752/753) | 250 | Chr1_469607_470359_c | 99 (249/250) | 99 (752/753) | 250 | pMI1_169764_170516_c | 99 (249/250) | 99 (752/753) | |

| 250 | pISP4_11370_12122 | identical | 250 | pTK3_74827_75579 | 99 (249/250) | 99 (752/753) | 250 | pMI3_15466_16218 | 99 (249/250) | 99 (752/753) | ||||||

| 250 | pTK4_21888_22640 | 99 (249/250) | 99 (752/753) | |||||||||||||

| linD | Reductive dechlorinase | 346 | pCHQ1_110947-111987_c | 346 | pISP3_15908_16948 | identical | 346 | pTK6_21982_23022 | identical | 346 | pMI1_148490_149530_c | identical | ||||

| 346 | pMI2_214796_215836 | identical | ||||||||||||||

| 346 | pMI4_28637_29677 | identical | ||||||||||||||

| linE | Ring-cleavage dioxygenase | 321 | pCHQ1_114235-115200_c | 321 | pISP3_12695_13660 | identical | 321 | pTK6_18769_19734 | identical | 321 | pMI1_151777_152742_c | identical | ||||

| 321 | pMI4_25425_26390 | identical | 99 (965/966) | |||||||||||||

| linEbc | 320 | Chr2_564928_565890 | 320 | pMI1_141726_142688_c | 99 (319/320) | 99 (961/963) | ||||||||||

| linR | LysR-family transcriptional regulator | 303 | pCHQ1_115332-116243 | 303 | pISP3_11652_12563_c | 99 (302/303) | 99 (911/912) | 303 | pTK6_17726_18637_c | identical | 303 | pMI1_152874_153785 | identical | |||

| 303 | pMI2_210541_211452_c | identical | ||||||||||||||

| 303 | pMI4_24382_25293_c | identical | ||||||||||||||

| linF | Maleylactate reductase | 352 | Chr2_562332-563390_c | 352 | pISP0_110260_111318_c | identical | 98 (1046/1059) | 352 | pMI1_144226_145284 | identical | 99 (1049/1059) | |||||

| linF' | 180 | pISP1_150100_150642 | 98 (176/178) | 99 (526/531) | 180 | Chr1_466905_467447_c | 98 (176/178) | 99 (526/531) | ||||||||

| 180 | pISP4_8847_9389_c | 98 (176/178) | 99 (526/531) | 180 | pTK3_77560_78102 | 98 (176/178) | 99 (526/531) | |||||||||

| linF'' | 127 | pMI1_167400_167783_c | 100 (122/122) | 98 (366/371) | ||||||||||||

| 127 | pMI3_18199_18582 | 100 (122/122) | 98 (366/371) | |||||||||||||

| linFb | 357 | Chr1_438688_439761_c | 49 (174/350) | |||||||||||||

| linG | Acyl-CoA transferase, alpha subunit | 215 | Chr2_603108-603755 | 215 | pISP0_152221_152868 | identical | 99 (647/648) | 239 | pMI1_102652_103371_c | 100 (215/215) | 99 (647/648) | |||||

| linH | Acyl-CoA transferase, beta subunit | 212 | Chr2_603755-604393 | 212 | pISP0_152868_153506 | identical | 99 (637/639) | 212 | pMI1_102014_102652_c | identical | 99 (637/639) | |||||

| linI | IclR-family transcriptional regulator | 267 | Chr2_602168-602971_c | 267 | pISP0_151281_152084_c | 99 (265/267) | 99 (798/804) | 265 | pMI1_103442_104239 | 99 (263/265) | 99 (798/804) | |||||

| linJ | Thiolase | 403 | Chr2_600921-602132_c | 403 | pISP0_150034_151245_c | identical | 99 (1202/1212) | 401 | pMI1_104281_105486 | 99 (400/401) | 99 (1202/1212) | |||||

| linK | Putative ABC transporter system, inner membrane protein | 376 | Chr1_19347-20477 | 366 | Chr_2358426_2359526 | 65 (239/364) | 83 (526/627) | 316 | Chr1_40913_41863_c | 95 (301/316) | 88 (1004/11131) | 369 | Chr1_40248_41357_c | 86 (320/369) | 87 (739/840) | |

| linKb | ||||||||||||||||

| linL | Putative ABC transporter system, ATPase | 282 | Chr1_20477-21325 | 282 | Chr1_40065_40913_c | 95 (268/282) | 91 (721/786) | 290 | Chr1_39376_40248_c | 90 (252/280) | 85 (627/734) | |||||

| linLb | 268 | Chr_2359526_2360332 | 75 (194/258) | 83 (141/168) | ||||||||||||

| linM | Putative ABC transporter system, periplasmic protein | 320 | Chr1_21329-22291 | 320 | Chr1_39099_40061_c | 98 (314/320) | 93 (899/963) | 320 | Chr1_38410_39372_c | 93 (297/319) | 86 (827/958) | |||||

| linMb | 317 | Chr_2360339_2361292 | 63 (201/319) | |||||||||||||

| linN | Putative ABC transporter system, lipoprotein | 202 | Chr1_22299-22907 | 204 | Chr1_38477_39091_c | 93 (190/204) | 88 (538/611) | 203 | Chr1_37784_38395_c | 81 (168/205) | 82 (384/464) | |||||

| linNb | 193 | Chr_2361298_2361879 | 42 (80/190) | |||||||||||||

ac, encoding on complementary strand.

blinF′ and linF″" are probably pseudogenes.

clinEb is homologue of PcpA (96% identity) and partially involved in γ-HCH degradation in UT26.34

The linKLMNUT26 homologues have been found in various bacterial strains16,29 and were also found in the MM-1, MI1205, and TKS genomes (Table 2). However, their similarities to linKLMNUT26 are lower (<93% identity at DNA level; Table 2) than in the case of the other lin genes mentioned earlier, and this divergence roughly reflects the phylogenetic relationship of their hosts (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S5), suggesting that the linKLMN system is one of the inherent functions necessary for γ-HCH utilization in sphingomonads. In particular, the linKLMN homologues of MM-1, which is phylogenetically the most distant strain from UT26 (Fig. 2), show a relatively low similarity with linKLMNUT26 (42–75% identities at the amino acid level; Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. S5), and they were designated linKbLbMbNb. To confirm their function for γ-HCH utilization, we attempted to disrupt the linKbLbMbNb gene cluster in MM-1. However, such an expected disruptant could not be constructed because unknown DNA rearrangements often occurred in MM-1. As an alternative confirmation, a plasmid containing the linKbLbMbNbMM-1 gene cluster was introduced into RE1, a linKLMNUT26 disruptant of UT26.29 The growth of RE1 in 1/3LB medium was inhibited by the addition of γ-HCH (Supplementary Fig. S6A),29 and this inhibition was suppressed by the supply of the linKbLbMbNb cluster (Supplementary Fig. S6B) as well as the linKLMNUT26 one (Supplementary Fig. S6C),29 strongly suggesting that the both clusters function in the same way for the γ-HCH utilization. These results supported our hypothesis that the linKLMN system is one of the inherent functions necessary for γ-HCH utilization in sphingomonads. However, the possibility cannot be excluded that other functional homologue(s) of linKLMN system exist in MM-1.

All of the four strains carry almost identical linA to linE genes (designated ‘specific’ lin genes) (Table 2), suggesting they acquired such genes by lateral gene transfer. However, the specific lin genes are dispersed on multiple replicons in the four strains (Table 2). In UT26, linA to linC are located on Chr1, and only the linRED cluster is located on a plasmid. On the other hands, all the specific lin genes are dispersed on multiple plasmids with various combinations in other three strains, although additional copies of linB and linC are also located on Chr1 in TKS (Table 1). Furthermore, replicon types of such plasmids carrying the specific lin genes are various (Table 3). These observations indicate that these four strains did not simply acquire all the specific lin genes at once as a cluster. This contrasts with other aromatic compound-degrading strains, which can acquire a whole set of responsible genes by the conjugative transfer of plasmids and/or integrative and conjugative elements.58–60

Table 3.

Classification of sphingomonad plasmids and plasmid-type replicons

| Replicona | Size (bp) | Host | Host feature | RepA protein | Type | Gene cluster for conjugation | Genes for degradation | Accession number | Reference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | A.A. | Identity (%) to representativea | ||||||||||

| UT26_Chr2 | 681,892 | S. japonicum UT26 | γ-HCH degradation | 1_1203 | 400 | — | repABC | linF, linGHIJ | AP010804 | 18 | ||

| L-1_Chr2 | 1,368,670 | Sphingobium chlorophenolicum L-1 | PCP degradation | 321340_322506 | 388 | 89 (359/400) | repABC | pcpBDR, pcpEMAC | CP002799 | 11 | ||

| TKS_Chr2 | 989,120 | Sphingobium sp. TKS | γ-HCH degradation | 1_1206 | 401 | 89 (360/401) | repABC | linGHIJ_homologue | CP005084 | 26 | ||

| MI_Chr2 | 567,154 | Sphingobium sp. MI1205 | γ-HCH degradation | 1_1209 | 402 | 83 (338/405) | repABC | CP005189 | 25 | |||

| pNL2 | 487,268 | Novosphingobium aromaticivorans DSM 12444 | aromatic compounds degradation | 209439_210644_c | 401 | 70 (284/401) | repABC | CP000677 | unpublished | |||

| Lpl | 192,103 | Novosphingobium sp. PP1Y | aromatic compounds degradation | 88922_90199 | 425 | 67 (288/425) | repABC | FR856860 | 80 | |||

| pISP1b | 172,140 | Sphingomonas sp. MM-1 | γ-HCH degradation | 114750_115880_c | 376 | 55 (201/363) | repABC | F | linA, linC, linF' | CP004038 | 23 | |

| TKS_Chr1b | 4,249,857 | Sphingobium sp. TKS | γ-HCH degradation | 252492_253622_c | 376 | 55 (200/363)d | repABC | F | linB, linC, linF', linFb, linKLMN | CP005083 | 26 | |

| pMI2b | 287,488 | Sphingobium sp. MI1205 | γ-HCH degradation | 183355_184485 | 376 | 55 (200/363)d | repABC | F | linA, linRD | CP005191 | 25 | |

| pMI1 | 292,135 | Sphingobium sp. MI1205 | γ-HCH degradation | 1_1224 | 407 | 42 (174/409) | repABC | F | linB, linC, linRED, linEb, linF, linF'', linGHIJ | CP005190 | 25 | |

| pTK1b | 520,614 | Sphingobium sp. TKS | γ-HCH degradation | 312340_313539 | 399 | 42 (171/401) | repABC | Ti, F | CP005085 | 26 | ||

| pCHQ1 | 190,974 | S. japonicum UT26 | γ-HCH degradation | 1_1164 | 387 | — | repABC | Ti, F | linRED | AP010805 | 18 | |

| pTK1b | 520,614 | Sphingobium sp. TKS | γ-HCH degradation | 1_1164 | 387 | identical | repABC | Ti, F | CP005085 | 26 | ||

| pSLGP | 148,801 | Sphingobium sp. SYK-6 | lignin degradation | 1_1164 | 387 | identical | repABC | Ti | AP012223 | 81 | ||

| pSPHCH01 | 123,733 | Sphingobium chlorophenolicum L-1 | PCP degradation | 47083_48171_c | 362c | identical | repABC | Ti | CP002800 | 11 | ||

| pISP0 | 275,840 | Sphingomonas sp. MM-1 | γ-HCH degradation | 4081_5244 | 387 | 98 (381/387) | repABC | Ti | linF, linGHIJ | CP004037 | 23 | |

| pUT1 | 31,776 | S. japonicum UT26 | γ-HCH degradation | 1_1104 | 367 | — | iteron | AP010806 | 18 | |||

| pMI2b | 287,488 | Sphingobium sp. MI1205 | γ-HCH degradation | 1_1104 | 367 | identical | iteron | F | linA, linRD | CP005191 | 25 | |

| pISP2 | 53,841 | Sphingomonas sp. MM-1 | γ-HCH degradation | 1_1104 | 367 | identical | iteron | CP004039 | 23 | |||

| pTK4b | 75,938 | Sphingobium sp. TKS | γ-HCH degradation | 1_1104 | 367 | identical | iteron | linA, linC | CP005088 | 26 | ||

| pISP3 | 43,776 | Sphingomonas sp. MM-1 | γ-HCH degradation | 37217_38329 | 370 | — | iteron | linRED | CP004040 | 23 | ||

| pMI4b | 32,974 | Sphingobium sp. MI1205 | γ-HCH degradation | 1_1113 | 370 | identical | iteron | linRED | CP005193 | 25 | ||

| pTK6 | 34,300 | Sphingobium sp. TKS | γ-HCH degradation | 1_1113 | 370 | identical | iteron | linRED | CP005090 | 26 | ||

| pTK3_1b | 87,635 | Sphingobium sp. TKS | γ-HCH degradation | 1_960 | 319 | — | iteron | linB, linC, linF' | CP005087 | 26 | ||

| pTK3_2b | 87,635 | Sphingobium sp. TKS | γ-HCH degradation | 52874_53821_c | 315 | — | iteron | linB, linC, linF' | CP005087 | 26 | ||

| pISP4 | 33,183 | Sphingomonas sp. MM-1 | γ-HCH degradation | 101_1012 | 303 | — | iteron | linB, linC, linF' | CP004041 | 23 | ||

| pISP1b | 172,140 | Sphingomonas sp. MM-1 | γ-HCH degradation | 158477_159388_c | 303 | identical | iteron | F | linA, linC, linF' | CP004038 | 23 | |

| pTK3b | 87,635 | Sphingobium sp. TKS | γ-HCH degradation | 19263_20174_c | 303 | identical | iteron | linB, linC, linF' | CP005087 | 26 | ||

| pTK4b | 75,938 | Sphingobium sp. TKS | γ-HCH degradation | 56463_57374 | 303 | identical | iteron | linA, linC | CP005088 | 26 | ||

| pMI3b | 88,374 | Sphingobium sp. MI1205 | γ-HCH degradation | 30095_31006_c | 303 | identical | iteron | Ti | linB, linC, linF'' | CP005192 | 25 | |

| pMI4b | 32,974 | Sphingobium sp. MI1205 | γ-HCH degradation | 18420_19331 | 303 | identical | iteron | linRED | CP005193 | 25 | ||

| pTK2 | 195,308 | Sphingobium sp. TKS | γ-HCH degradation | 1_1122 | 373 | — | iteron | Ti | CP005086 | 26 | ||

| pTK7 | 9,585 | Sphingobium sp. TKS | γ-HCH degradation | 1_1107 | 368 | — | iteron | CP005091 | 26 | |||

| pTK8 | 7,223 | Sphingobium sp. TKS | γ-HCH degradation | 1_1032 | 343 | — | iteron | CP005092 | 26 | |||

| pNL1 | 184,462 | Novosphingobium aromaticivorans DSM 12444 | aromatic compounds degradation | 86362_87666 | 434 | — | iteron | CP000676 | unpublished | |||

| pCAR3 | 254,797 | Novosphigobium sp. KA1 | carbazole degradation | 200594_201898_c | 434 | 91 (398/433) | iteron | AB270530 | 82 | |||

| Mpl | 1,161,602 | Novosphingobium sp. PP1Y | aromatic compounds degradation | 513635_514939_c | 434 | 85 (372/434) | iteron | FR856861 | 80 | |||

| pSWIT02 | 222,757 | Sphingomonas wittichii RW1 | dioxin degradation | 63589_64893 | 434 | 82 (356/429) | iteron | CP000701 | 83 | |||

| pLB1 | 65,998 | unidentifed soil bacterium (S. japonicum UT26) | γ-HCH degradation | 1_783 | 260 | — | Ti | linB | AB244976 | 74 | ||

| pMI3b | 88,374 | Sphingobium sp. MI1205 | γ-HCH degradation | 1_783 | 260 | identical | Ti | linB, linC, linF' | CP005192 | 25 | ||

| pLA2 | 62,341 | Novosphingobium pentaromativorans US6-1 | benzo(a)pyrene degradation | 40543_41325 | 260 | 98 (256/260) | Ti | AGFM01000123 | 84 | |||

| pTK5 | 53,908 | Sphingobium sp. TKS | γ-HCH degradation | 1_783 | 260 | 97 (253/260) | Ti | CP005089 | 26 | |||

| pUT2 | 5,398 | S. japonicum UT26 | γ-HCH degradation | 1_654 | 217 | — | iteron | AP010807 | 18 | |||

| pTK9 | 5,391 | Sphingobium sp. TKS | γ-HCH degradation | 1_654 | 217 | identical | iteron | CP005093 | 26 | |||

aThe representative replicons of each type ones are indicated in bold in the first column.

bReplicons having more than one rep genes.

cStart codon is differently annotated for the same DNA region.

dIdentical with each other.

Although, in the present study, we only described the overall genetic repertoire of the lin genes for γ-HCH utilization, the composition of genes for LinA and LinB variants and their copy numbers and expression levels are important for the degradation performance of host strains toward HCH isomers, since the LinA and LinB variants show different levels of enzymatic activity toward different HCH isomers and their metabolites.7,16,61–64 However, in order to properly discuss this point from a genomic viewpoint, additional fundamental biochemical and experimental data will be needed.

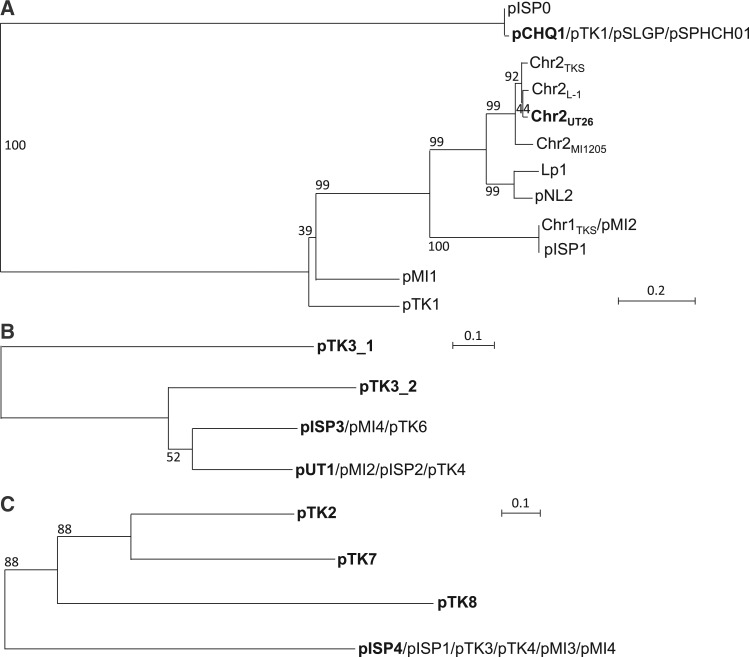

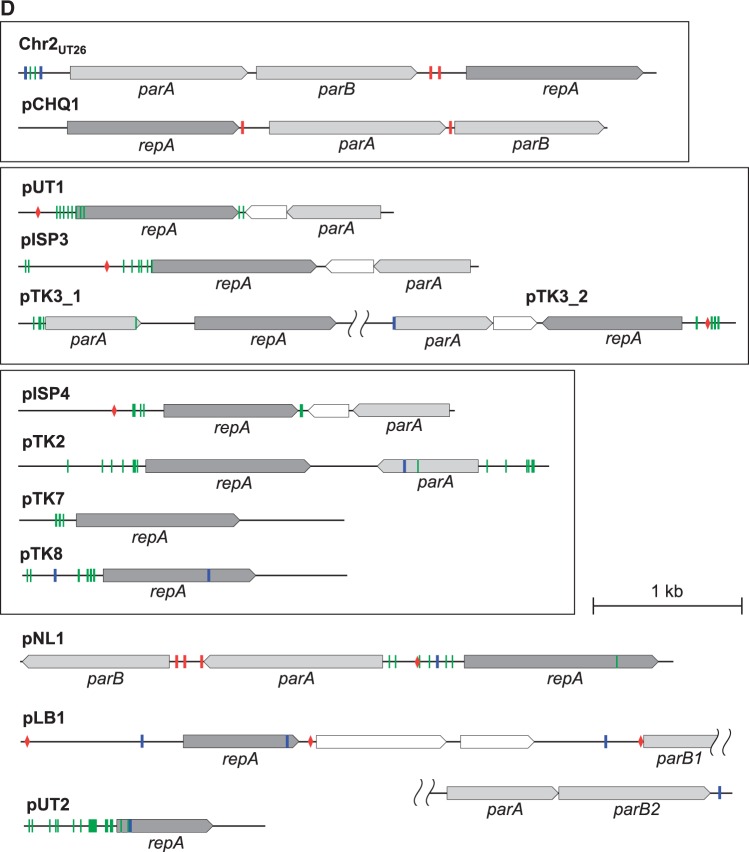

3.3. Replication/partition-encoding regions of plasmids and plasmid-type replicons in sphingomonad strains

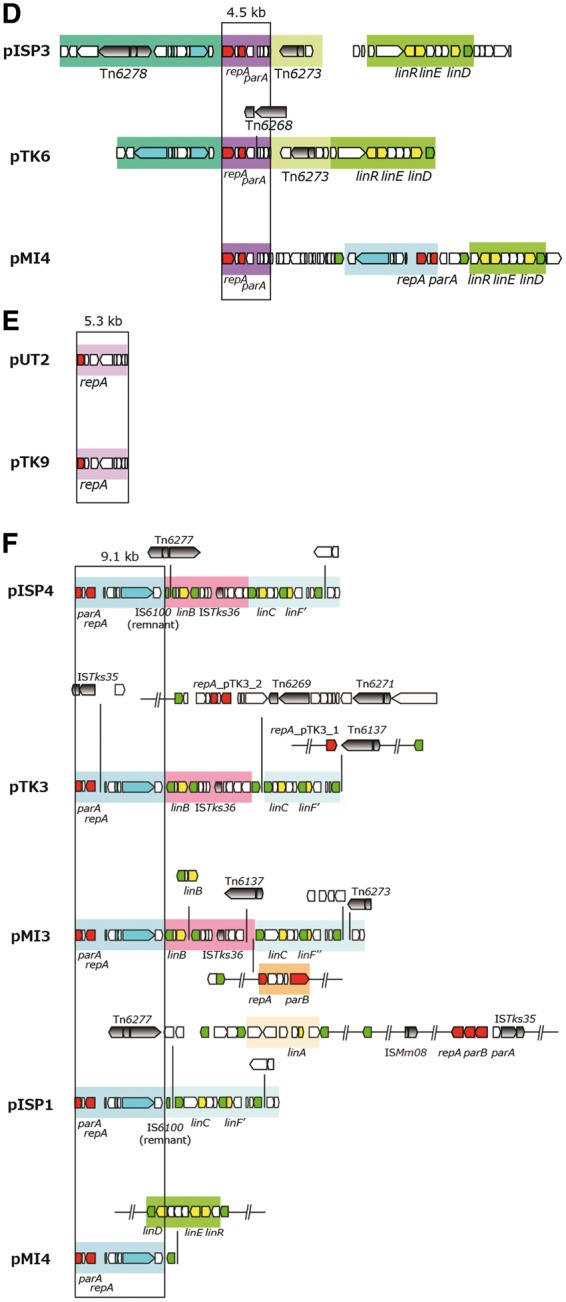

The putative replication origins (oriCs) of the main chromosomes (Chr1s) of TKS, MI1205, and MM-1 were, as in the case with Chr1UT26,18 found to be of alphaproteobacterial-chromosome type;65,66 these oriCs were located upstream of the uroprophyrinogen decarboxylase gene (hemE) with multiple DnaA boxes [TT(A/T)TNCACA] (Supplementary Fig. S7).67 On the other hand, as in the case of Chr2UT26, both Chr2TKS and Chr2MI1205 have the plasmid-type replication and active partition systems.18 These three plasmid-type chromosomes and the 21 plasmids in our four strains and the plasmids from other sphingomonads were, on the basis of the similarities of their RepA (DNA replication initiator) proteins, classified into 13 types (Table 3). Although the importance of plasmids in sphingomonads has been recognized,8 no detailed analysis of their fundamental machineries was reported. In addition, RepA proteins of plasmids in sphingomonads show a very low level of similarity to those of well-studied plasmids (e.g. IncP-1, F, IincP-7, and IncP-9 plasmids), and thus we compared only plasmids in sphingomonads in this study. Since the RepA proteins of the 13 types are very divergent, they were further categorized into three major groups, in each of which the RepA proteins exhibit 22–60% identity: (i) the Chr2UT26- and pCHQ1-types (Fig. 4A), (ii) the pUT1-, pISP3-, pTK3_1-, and pTK3_2-types (Fig. 4B), and (iii) the pISP4-, pTK2-, pTK7-, and pTK8-types (Fig. 4C). Based on our BLASTP analysis, the RepA proteins of pNL1, pLB1, and pUT2 did not show similarity to those of any of the other types of plasmids listed in Table 3, although the RepA of pUT2 was similar to those of the IncP-9 family of plasmids.18 Figure 4D schematically shows the organizations of the repA-flanking regions in the 12 representative plasmids (note that pTK3 has three types of repA genes), and many of these regions also carry the putative replication origin (oriV) sequences as well as the putative genes for the active partition systems, each with the putative parS (cis-acting centromeric) sequences, the parB gene encoding the parS-binding protein, and the parA gene encoding the NTPase that is capable of binding the parS-ParB complex.68 The Chr2UT26- and pCHQ1-type plasmids belong to the repABC-type plasmids,69 and putative palindromic parS sequences were found (Fig. 4D and Supplementary Table S6). The Chr2UT26-type plasmids have the parA-parB-repA cluster, and the order of these three genes is conserved in other typical repABC-type plasmids,69 although the RepA proteins from the Chr2UT26-type plasmids are divergent in their sizes and similarities (Table 3 and Fig. 4A). In contrast, the pCHQ1-type plasmids have a repA-parA-parB cluster (Fig. 4D) with nearly identical RepA proteins (Table 3). Other types of plasmids except the pLB1-type were categorized as iteron-type plasmids (Table 3),70,71 and direct repeats (iteron), DnaA box, and parS sequences were found in their repA-flanking regions (Fig. 4D and Supplementary Table S6). Each of the pISP1, Chr1TKS, pTK1, pTK3, pTK4, pMI2, pMI3, and pMI4 replicons appears to carry at least two repA genes, which are of different types (Tables 1 and 3). This observation suggested the frequent occurrence of fusions of ancestral plasmids (see below). Similar mosaic replicons carrying more than one repA gene have been reported in various bacterial strains.72 Interestingly, six pISP4-type plasmids carry identical repA and parA genes, and five of them also have other types of repA genes (Table 3), suggesting a prevalent fusion event of replicons in the pISP4-type plasmids (see below). It is noteworthy that all six pISP4-type plasmids contain the lin genes (Table 3), indicating that this type of plasmid plays an important role in dissemination of the lin genes.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic trees of putative RepA proteins of Chr2UT26- and pCHQ1- (A), pUT1- (B), and pISP4- (C) types plasmids and organizations of repA-flanking regions of 12 representative sphingomonad plasmids (D). Classification of 13 types of plasmids and information on RepA protein sequences are summarized in Table 3. Neighbour-joining phylogenetic trees of the conserved sites, 260 aa (A), 262 aa (B), and 257 aa (C), respectively, were constructed. Bootstrap values calculated from 1,000 resampling using neighbour-joining are shown at the respective nodes. Length of lines reflects relative evolutionary distances among the sequences. RepA proteins of the representatives of the plasmid types (Table 3) are bolded. In panel D, the repA-flanking regions of plasmids whose putative RepA proteins show significant similarity are boxed. Pentagons indicate size and direction of ORF. Putative ORFs involved in replication and partition are filled with dark and light gray, respectively. Putative parS (palindromic TTN4CG N4AA) 79 and DnaA box [TT(A or T)TNCACA] 67 sequences are shown in red bars and red diamonds, respectively. Inverted repeats and repeat sequences are shown in blue and green bars, respectively. See Supplementary Table S6 for their sequences.

3.4. Highly conserved regions of replicons in sphingomonad strains

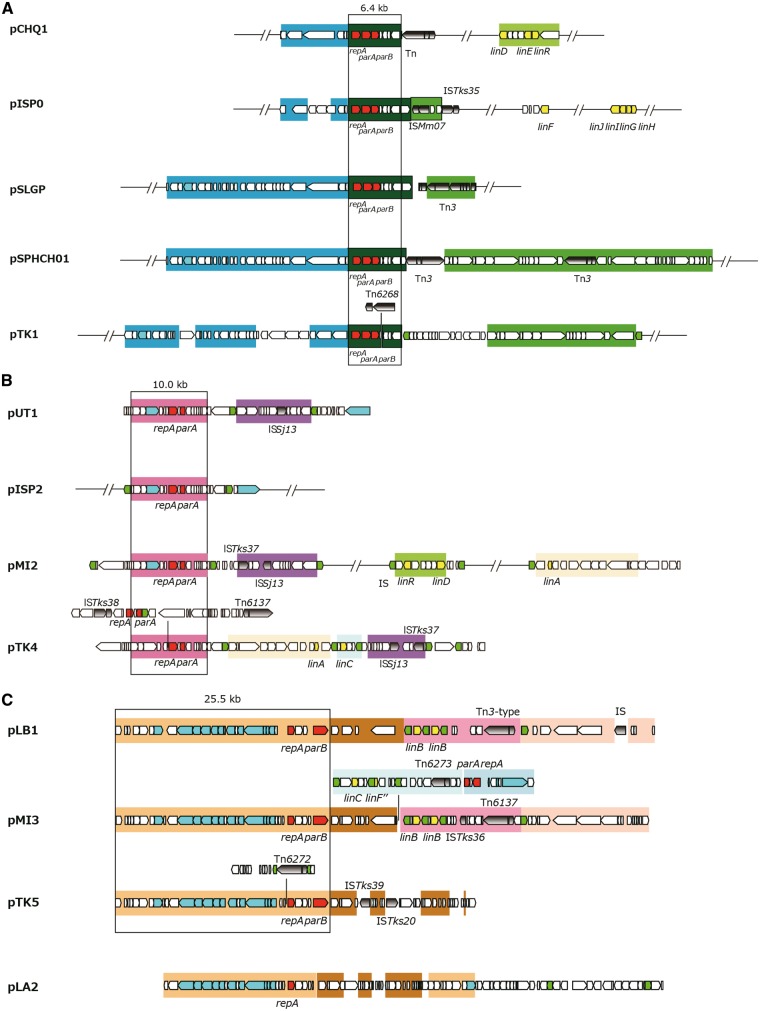

Although multiple members in each of the pCHQ1-, pUT1-, pLB1-, pISP3-, pUT2-, and pISP4-type plasmids have almost identical repA-containing regions, the sizes and gene contents of the plasmid members in each type are diverse (Table 3). Therefore, we compared the overall structures in the six types of plasmids (Fig. 5). The 6.4-kb repA-parA-parB-containing region and the 10-kb repA-parA-containing region are conserved in all members of the pCHQ1- and pUT1-type plasmids, respectively (Fig. 5AB). The 25.5-kb region containing the pLB1-type repA and parB genes is conserved in pMI3 and pTK5 (Fig. 5C). Most of this region is also conserved in pLA2, although the region is divided into two parts and the parB gene is lacking (Fig. 5C). pMI3 is a fusion plasmid of the pLB1- and pISP4-type plasmids because the 9.1-kb repA-parA-containing region commonly conserved in the pISP4-type plasmids (Fig. 5F) is, together with the linC- and linF″-containing region, inserted into the continuous region on pLB1 (Fig. 5C). A part of the 9.1-kb conserved region is also present in pTK4 (Fig. 5B). The 4.5-kb region containing the pISP3-type repA and parA genes is conserved in pTK6 and pMI4 (Fig. 5D). Two 1,645-bp plasmids, pUT2 and pTK9, differ by only 9 bp (Fig. 5E). As mentioned above, all the pISP4-type plasmids except for archetypal pISP4 have, in addition to the common repA gene, other distinct repA genes (Table 3), and probably are fusion plasmids. IS6100 or the Tn3-type transposon is located at the junctions of highly conserved regions of pISP4-type plasmids (Fig. 5F), suggesting that the pISP4-type plasmids are easily fused with other replicons via the transposition of IS6100 and/or the Tn3-type transposon. The repA, parA, and parB genes of the Chr2UT26-type replication machineries were also located on Chr1TKS, pISP1, pMI2, Chr2TKS, pTK1, Chr2MI1205, and pMI1 (Table 3), and the former three replicons carry an almost identical 20.3-kb region that covers the Chr2UT26-type repA, parA, and parB genes (Supplementary Fig. S8). Our findings in this section clearly indicate that the replicons having highly conserved replication/partition genes are distributed among sphingomonad strains with frequent recombination events including replicon fusion.

Figure 5.

Structures of plasmids which have the highly conserved regions in the four γ-HCH-degrading sphingomonad strains. The highly conserved regions in pCHQ1- (A), pUT1- (B), pLB1- (C), pISP3- (D), pUT2- (E), and pISP4- (F) types plasmids are schematically shown. See Table 3 for the classification of plasmids. ORFs shown by pentagons are coloured as follows: red, rep and par genes; green, transposase gene of IS6100; cyan, putative genes for conjugal transfer; yellow, lin genes; and gray with gradient, transposition-related genes in other putative transposons. Almost identical regions are shown by the same background colours.

3.5. Genes for conjugal transfer of plasmids in HCH-degrading sphingomonads

The genes for conjugal transfer consist of those encoding proteins involved in mating pair formation (Mpf) and DNA transfer and replication (Dtr).73 The mpf genes encode proteins that assemble in a large macromolecular structure called the Type IV secretion system (T4SS), whereas the dtr genes encode proteins that bind to the DNA at the origin of transfer region, oriT, forming a structure called a relaxosome. This modular gene organization is shared by most conjugative systems, showing a high degree of gene synteny conservation. Among the sphingomonad plasmids listed in Table 3, conjugal transferability of pCHQ1 and pLB1 has been experimentally confirmed,36,74 and these two plasmids have putative gene clusters for conjugal transfer similar to the vir gene cluster of Agrobacterium tumefaciens Ti plasmid, consisting of genes for Mpf (VirB1 to VirB11) and Dtr (relaxase VirD2 and coupling protein VirD4)( Supplementary Fig. S9A). 17,74 Putative vir gene clusters were also found on pISP0, pTK1, pTK2, pTK5, and pMI3 (Supplementary Fig. S9A), indicating the potential self-transferability of these plasmids. However, the level of similarity of each component to the counterpart of Ti plasmid is relatively low, and only the phylogenetic relationship of the putative cytoplasmic ATPase component (VirB4), which is the essential and most conserved component of T4SS,73 encoded by these clusters is shown (Supplementary Fig. S9B). pCHQ1 has another putative gene cluster for conjugal transfer similar to the tra gene cluster of F plasmid,75 and gene clusters similar to the tra gene cluster were also found on Chr1TKS, pMI1, pMI2, pTK1, and pISP1 (Supplementary Fig. S9C). As in the case with the gene clusters homologous to the vir gene cluster, the level of similarity of each component to its counterpart in F plasmid is relatively low, and only phylogenetic relationship of cytoplasmic ATPase component (TraC: VirB4 homologue in function) encoded by these clusters is shown (Supplementary Fig. S9D). However, traI and traD, which encode the relaxase and coupling protein, respectively, were not found on pCHQ1, and traD and traG, which encode the coupling protein and inner membrane platform component, respectively, are missing on pISP1 (Supplementary Fig. S9C). Further experimental confirmation is necessary to demonstrate the self-transferability of these plasmids having putative gene clusters for conjugal transfer.

3.6. Transposable elements in four γ-HCH degraders

Many putative transposable elements including IS elements and Tn3-type transposons were found in the genomes of the four γ-HCH degraders (Supplementary Table S7).18 Although most of the IS elements are present as a single-copy form in the four strains (Supplementary Table S7), IS6100 is, as in the case of UT26, the most abundant element in the MM-1, TKS, and MI1205 genomes (15, 29, and 24 copies, respectively) (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S7). This suggests that IS6100 can transpose and increase its copy number in these γ-HCH degraders. To investigate the transposition activity of IS6100 and other transposable elements, the IS entrapment methodology using pGEN50042 was applied for the four γ-HCH degraders. We conducted several independent analyses for each strain, and detected the successful transposition of IS6100, ISsp1, ISSj02, ISSj12, and Tn6134 in UT26, IS6100, ISSj02, ISTks12, Tn6268, and Tn6269 in TKS, and IS6100, ISsp1, ISMi02, ISMi08, Tn6137, and Tn6274 in MI1205 (Supplementary Table S7). On the other hand, this IS-entrapment system did not work well in MM-1 because of the high-frequency generation of the spontaneous sucrose-resistant mutants without the insertion of transposable elements into the sacB gene on pGEN500 (data not shown).

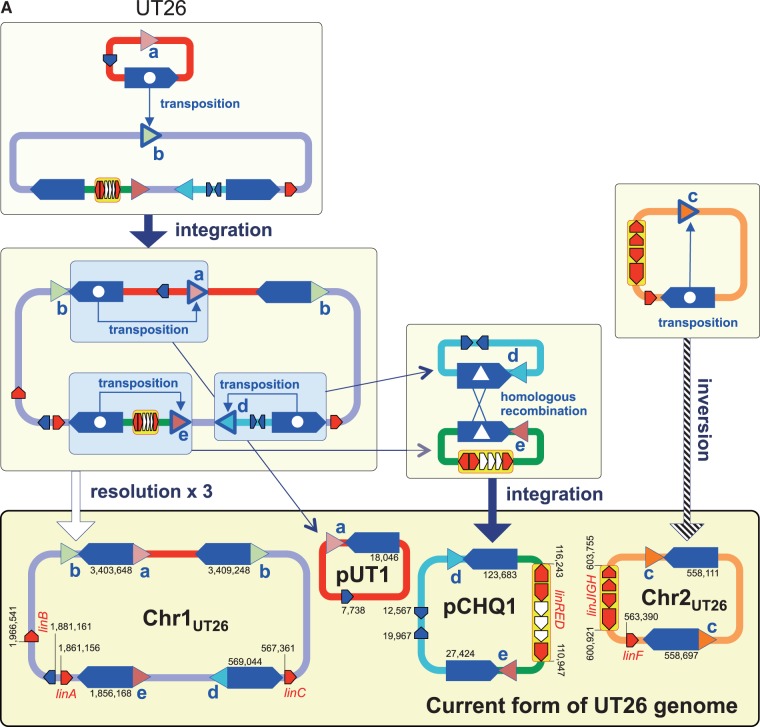

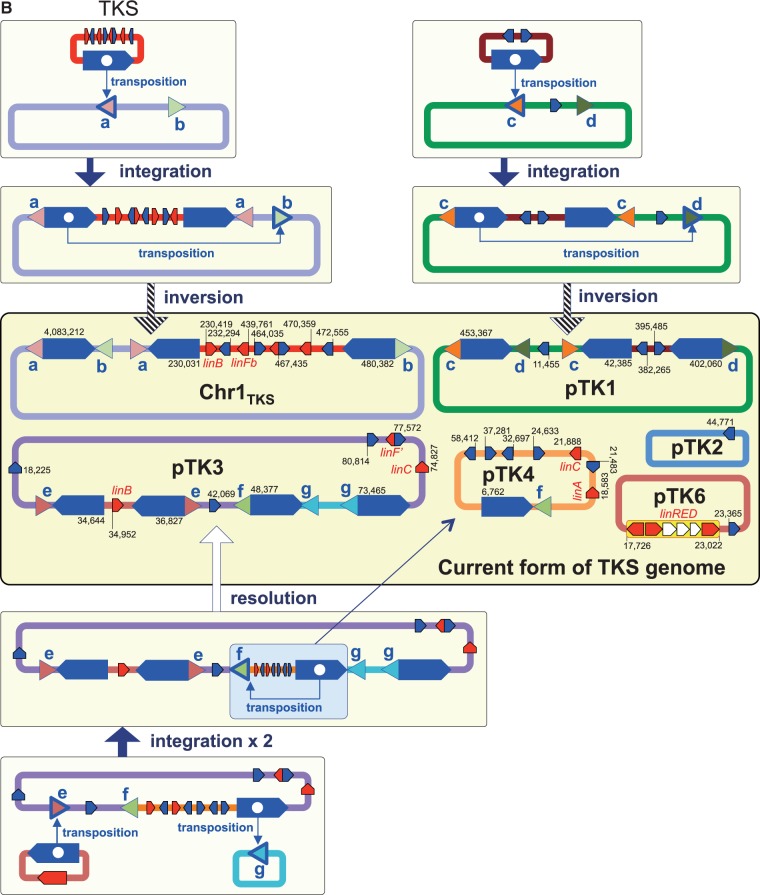

3.7. Inference of the past genome rearrangements via IS6100

IS6100 is often located in close proximity to the lin genes in the HCH-degrading strains and the metagenomic sequences from HCH-contaminated sites.76,77 IS6100 with a size of 880 bp is a ‘replicative’ IS element (Supplementary Fig. S10),78 and its transposition without apparent preference of target specificity causes the duplication of IS6100 with an 8-bp duplication of the target sequence. Therefore, the IS6100 transposition can generate three types of DNA rearrangements (Supplementary Fig. S11): intra-molecular transposition with a deletion/resolution (intra-replicon 1) or inversion (intra-replicon 2) event, and inter-molecular transposition with a fusion (inter-replicon) event. Our comparison of the regions just upstream and downstream of the 13 copies of IS6100 present on Chr1, Chr2, pCHQ1, and pUT1 of UT26 revealed five pairs of 8-bp sequences (Supplementary Table S8). On the basis of the IS6100 transposition mechanism (Supplementary Fig. S11), the most plausible past events caused by transposition of IS6100 can be inferred (Fig. 6A); it is indicated that not only simple transposition with inversion but also transposition accompanied with the fusion and resolution of replicons must have occurred. In a similar manner, seven, one, and four pairs of 8-bp sequences were found just upstream or downstream of IS6100 in TKS, MM-1, and MI1205, respectively (Supplementary Table S8), and the plausible past events mediated by transposition of IS6100 in these strains are depicted in Figure 6B–D.

Figure 6.

Inference of the past genome rearrangements via IS6100 in UT26 (A), TKS (B), MM-1 (C), and MI1205 (D). Blue pentagons, triangles with alphabet, and red pentagons indicate IS6100, 8-bp target sites, and lin genes, respectively. Triangles with the same alphabet mean identical sequence and direction (see Supplementary Table S8 and Supplementary Fig. S11 for detail: note that sequences shown in Supplementary Table S8 are cyan strands of 8-bp targets in Supplementary Fig. S11). Blue pentagons marked with internal white circle and triangle indicate the IS6100 element which transposed and mediated homologous recombination, respectively. IS6100 is a ‘replicative’ IS element, and it increases its copy number with the transposition (Supplementary Fig. S11). Only replicons carrying IS6100 are illustrated, and relative positions and directions of IS6100 and lin genes in each replicon are schematically shown. The IS6100 elements involved in the proposed past genome rearrangements are shown in larger size. Numbers in current forms of the four strains indicate locations of IS6100s and lin genes in each replicon.

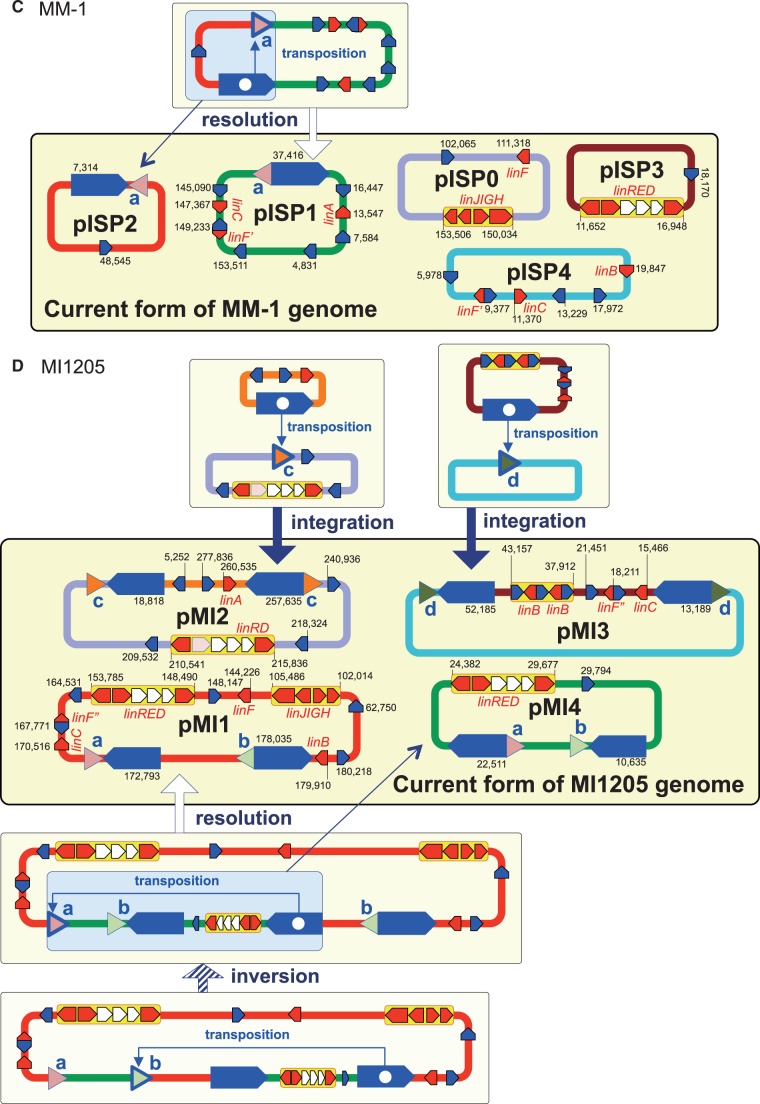

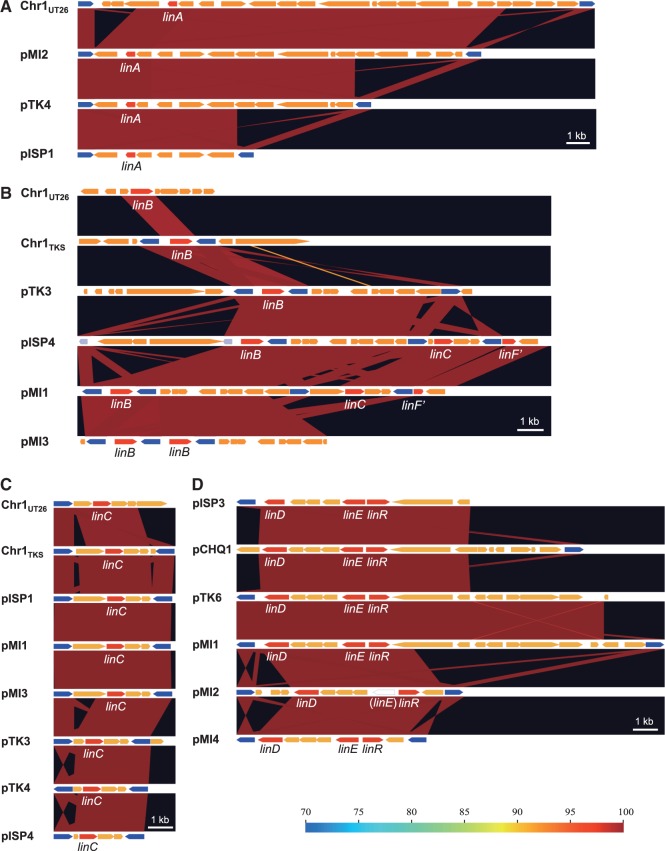

The specific lin-flanking regions in the four strains were compared (Fig. 7). Not only the lin genes themselves (Table 2) but also their flanking regions are highly conserved (Fig. 7). Interestingly, such conserved regions are located very close to IS6100 and the distances between the IS6100 copies and the lin genes are varied (Fig. 7). This means that IS6100 is likely to play a crucial ‘editing’ role in the ‘trimming’ of ‘unnecessary regions’ for HCH utilization and the ‘gathering’ of the specific lin genes. At least, it is the most plausible that the transposition of IS6100 led to the diversification of the distribution and organization of the lin genes in the genomes. The distance between IS6100 and linA is the longest in UT26 (Fig. 7A), and the linB gene in UT26 has no IS6100 element in its flanking regions (Fig. 7B). Moreover, IS6100 is located at only one side of linC (Fig. 7C) and the linRED cluster (Fig. 7D) in UT26. These results suggested that UT26 is the closest to the prototype of the γ-HCH degrader, at least among the four strains examined in this study.

Figure 7.

Comparison of regions containing the specific lin genes in the four γ-HCH-degrading sphingomonad strains. The regions containing linA (A), linB (B), linC (C), and linRED cluster (D) were compared. The regions homologous to each other were coloured in the gradient depending on the level of similarity as shown in explanatory note. The lin genes, transposase gene of IS6100, and other ORFs were shown by pentagons in red, blue, and orange, respectively. The pseudo ‘linE’ gene exists in pIM2 of MI1205 at the region corresponding to the linE gene in other plasmids.

3.8. Conclusions and perspectives

Our comparison of the complete genome sequences of four γ-HCH-degrading sphingomonad strains and gathering of experimental data in this study demonstrate or strongly suggest the following points: (i) the gene repertoires and genomic organizations of the four γ-HCH-degrading strains, which are phylogenetically dispersed among related sphingomonad strains (Fig. 2), are relatively different from one another (Table 1 and Fig. 3); (ii) all four strains carry almost identical linA to linE genes for the conversion of γ-HCH to maleylacetate (Fig. 1 and Table 2); (iii) considerably different genes are used for the metabolism of maleylacetate in TKS (Fig. 1, Table 2, and Supplementary Table S5); (iv) the linKLMN genes for the putative ABC transporter necessary for γ-HCH utilization are structurally divergent, and such divergence reflects the phylogenetic relationship of their hosts (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S5 and Table 2); (v) most of the linA to linJ genes for the catabolic enzymes are located on several replicons whose replication/partition systems are highly conserved among sphingomonad plasmids (Tables 1 and 3); and (vi) the transposition of IS6100 has caused dynamic genome rearrangements including the fusion and resolution of replicons and the diversification of lin-flanking regions in the four strains (Figs. 6 and 7).

Based on our results in this study, we propose that these γ-HCH-degraders were formed independently in different geographic regions through the recruitment of specific lin genes and genes for the metabolism of maleylacetate into ancestral strains that had the core functions (including the linKLMN-encoded one) of sphingomonads. Multiple plasmids whose replication/partition machineries are highly conserved in sphingomonads might have played important roles in the recruitment of the specific lin genes by their horizontal transfer. In addition, IS6100 likely plays a crucial ‘editing’ role in the distribution and organization of the lin genes in genomes. In the future, our hypothesis may be confirmed in experiments using the four HCH degraders and their related but non-HCH-degrading and/or IS6100-free sphingomonad strains.

4. Data availability

The sequences with the annotation of replicons in MM-1, MI1205, and TKS have been deposited in DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases under the accession numbers shown in Table 1. Nucleotide sequences of the Tn3-type transposons, Tn6268 to Tn6278, were deposited in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases under accession numbers LC102249 to LC102259, respectively.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Accession number

CP004036 to CP004041, CP005083 to CP005093, CP005188 to CP005193, and LC102249 to LC102259.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at www.dnaresearch.oxfordjournals.org.

Funding

This work was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI grant numbers (22380047 and 25292043).

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Ogata Y., Takada H., Mizukawa K., et al. 2009, International Pellet Watch: global monitoring of persistent organic pollutants (POPs) in coastal waters. 1. Initial phase data on PCBs, DDTs, and HCHs, Mar. Pollut. Bull., 58, 1437–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Shahawi M. S., Hamza A., Bashammakh A. S., Al-Saggaf W. T. 2010, An overview on the accumulation, distribution, transformations, toxicity and analytical methods for the monitoring of persistent organic pollutants, Talanta, 80, 1587–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tarcau D., Cucu-Man S., Boruvkova J., Klanova J., Covaci A. 2013, Organochlorine pesticides in soil, moss and tree-bark from North-Eastern Romania, Sci. Total Environ., 456–457, 317–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Janssen D. B., Dinkla I. J., Poelarends G. J., Terpstra P. 2005, Bacterial degradation of xenobiotic compounds: evolution and distribution of novel enzyme activities, Environ. Microbiol., 7, 1868–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Copley S. D. 2009, Evolution of efficient pathways for degradation of anthropogenic chemicals, Nature Chem. Biol., 5, 559–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stolz A. 2009, Molecular characteristics of xenobiotic-degrading sphingomonads, Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol., 81, 793–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lal R., Pandey G., Sharma P., et al. 2010, Biochemistry of microbial degradation of hexachlorocyclohexane and prospects for bioremediation, Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev., 74, 58–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stolz A. 2014, Degradative plasmids from sphingomonads, FEMS Microbiol. Lett., 350, 9–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagata Y., Tabata M., Ohtsubo Y., Tsuda M. 2015, Biodegradation of organochlorine pesticides In: Yates M., Nakatsu C., Miller R., Pillai S. (eds), Manual of Environmental Microbiology, 4th edn., ASM Press, Washington, DC. pp. 5.1.2-1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Top E. M., Springael D. 2003, The role of mobile genetic elements in bacterial adaptation to xenobiotic organic compounds, Curr. Opin. Biotechnol., 14, 262–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Copley S. D., Rokicki J., Turner P., Daligault H., Nolan M., Land M. 2011, The whole genome sequence of Sphingobium chlorophenolicum L-1: insights into the evolution of the pentachlorophenol degradation pathway, Genome Biol. Evol., 4, 184–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Udikovic-Kolic N., Scott C., Martin-Laurent F. 2012, Evolution of atrazine-degrading capabilities in the environment, Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol., 96, 1175–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Satola B., Wubbeler J. H., Steinbuchel A. 2013, Metabolic characteristics of the species Variovorax paradoxus, Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol., 97, 541–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phillips T. M., Seech A. G., Lee H., Trevors J. T. 2005, Biodegradation of hexachlorocyclohexane (HCH) by microorganisms, Biodegradation, 16, 363–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vijgen J., Abhilash P. C., Li Y. F., et al. 2011, Hexachlorocyclohexane (HCH) as new Stockholm Convention POPs-a global perspective on the management of Lindane and its waste isomers, Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int., 18, 152–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagata Y., Endo R., Ito M., Ohtsubo Y., Tsuda M. 2007, Aerobic degradation of lindane (γ-hexachlorocyclohexane) in bacteria and its biochemical and molecular basis, Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol., 76, 741–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagata Y., Ohtsubo Y., Endo R., et al. 2010, Complete genome sequence of the representative γ-hexachlorocyclohexane-degrading bacterium Sphingobium japonicum UT26, J. Bacteriol., 192, 5852–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagata Y., Natsui S., Endo R., et al. 2011, Genomic organization and genomic structural rearrangements of Sphingobium japonicum UT26, an archetypal γ-hexachlorocyclohexane-degrading bacterium, Enzyme Microb. Technol., 49, 499–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagata Y., Tabata M., Ohhata S.,, Tsuda M. 2014, Appearance and evolution of γ-hexachlorocyclohexane-degrading bacteria, In: Nojiri H., Tsuda M., Fukuda M., Kamagata Y. (eds) Biodegradative Bacteria, Springer Verlag: Tokyo, pp. 19–41. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Verma H., Kumar R., Oldach P., et al. 2014, Comparative genomic analysis of nine Sphingobium strains: insights into their evolution and hexachlorocyclohexane (HCH) degradation pathways, BMC genomics, 15, 1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pearce S. L., Oakeshott J. G., Pandey G. 2015, Insights into ongoing evolution of the hexachlorocyclohexane catabolic pathway from comparative genomics of ten Sphingomonadaceae strains, G3, 5, 1081–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tabata M., Endo R., Ito M., et al. 2011, The lin genes for γ-hexachlorocyclohexane degradation in Sphingomonas sp. MM-1 proved to be dispersed across multiple plasmids, Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem., 75, 466–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tabata M., Ohtsubo Y., Ohhata S., Tsuda M., Nagata Y. 2013, Complete genome sequence of the γ-hexachlorocyclohexane-degrading bacterium Sphingomonas sp. strain MM-1, Genome Announc., 1, e00247–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ito M., Prokop Z., Klvana M., et al. 2007, Degradation of β-hexachlorocyclohexane by haloalkane dehalogenase LinB from γ-hexachlorocyclohexane-utilizing bacterium Sphingobium sp. MI1205, Arch. Microbiol., 188, 313–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tabata M., Ohhata S., Nikawadori Y., et al. 2016, Complete genome sequence of a γ-hexachlorocyclohexane-degrading bacterium, Sphingobium sp. strain MI1205, Genome Announc., 4, e00246–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tabata M., Ohhata S., Kawasumi T., et al. 2016, Complete genome sequence of a γ-hexachlorocyclohexane degrader, Sphingobium sp. strain TKS, isolated from a γ-hexachlorocyclohexane-degrading microbial community, Genome Announc., 4, e00247–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yabuuchi E., Kosako Y., Fujiwara N., et al. 2002, Emendation of the genus Sphingomonas Yabuuchi et al. 1990 and junior objective synonymy of the species of three genera, Sphingobium, Novosphingobium and Sphingopyxis, in conjunction with Blastomonas ursincola, Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol., 52, 1485–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maniatis T., Fritsch E., Sambrook J. 1982, Molecular cloning: a Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory: NY. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Endo R., Ohtsubo Y., Tsuda M., Nagata Y. 2007, Identification and characterization of genes encoding a putative ABC-type transporter essential for utilization of γ-hexachlorocyclohexane in Sphingobium japonicum UT26, J. Bacteriol., 189, 3712–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nagata Y., Futamura A., Miyauchi K., Takagi M. 1999, Two different types of dehalogenases, LinA and LinB, involved in γ-hexachlorocyclohexane degradation in Sphingomonas paucimobilis UT26 are localized in the periplasmic space without molecular processing, J. Bacteriol., 181, 5409–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kovach M. E., Elzer P. H., Hill D. S., et al. 1995, Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes, Gene, 166, 175–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoang T. T., Karkhoff-Schweizer R. R., Kutchma A. J., et al. 1998, A broad-host-range Flp-FRT recombination system for site-specific excision of chromosomally-located DNA sequences: application for isolation of unmarked Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants, Gene, 212, 77–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sambrook J., Fritsch E., Maniatis T. 1989, Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 2nd, edn. Cold Spring Harbor: NY. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Endo R., Kamakura M., Miyauchi K., et al. 2005, Identification and characterization of genes involved in the downstream degradation pathway of γ-hexachlorocyclohexane in Sphingomonas paucimobilis UT26, J. Bacteriol., 187, 847–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ohtsubo Y., Maruyama F., Mitsui H., Nagata Y., Tsuda M. 2012, Complete genome sequence of Acidovorax sp. strain KKS102, a polychlorinated-biphenyl degrader, J. Bacteriol., 194, 6970–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagata Y., Kamakura M., Endo R., Miyazaki R., Ohtsubo Y., Tsuda M. 2006, Distribution of γ-hexachlorocyclohexane-degrading genes on three replicons in Sphingobium japonicum UT26, FEMS Microbiol. Lett., 256, 112–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ohtsubo Y., Ikeda-Ohtsubo W., Nagata Y., Tsuda M. 2008, GenomeMatcher: a graphical user interface for DNA sequence comparison, BMC bioinformatics, 9, 376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Altschul S. F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E. W., Lipman D. J. 1990, Basic local alignment search tool, J. Mol. Biol., 215, 403–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Katoh K., Standley D. M. 2013, MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability, Mol. Biol. Evol., 30, 772–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perriere G., Gouy M. 1996, WWW-query: an on-line retrieval system for biological sequence banks, Biochimie, 78, 364–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kato H., Mori H., Maruyama F., et al. 2015, Time-series metagenomic analysis reveals robustness of soil microbiome against chemical disturbance, DNA Res., 22, 413–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ohtsubo Y., Genka H., Komatsu H., Nagata Y., Tsuda M. 2005, High-temperature-induced transposition of insertion elements in Burkholderia multivorans ATCC 17616, Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 71, 1822–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perez-Pantoja D., De la Iglesia R., Pieper D. H., Gonzalez B. 2008, Metabolic reconstruction of aromatic compounds degradation from the genome of the amazing pollutant-degrading bacterium Cupriavidus necator JMP134, FEMS Microbiol. Rev., 32, 736–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lykidis A., Perez-Pantoja D., Ledger T., et al. 2010, The complete multipartite genome sequence of Cupriavidus necator JMP134, a versatile pollutant degrader, PLoS One, 5, e9729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chain P. S., Denef V. J., Konstantinidis K. T., et al. 2006, Burkholderia xenovorans LB400 harbors a multi-replicon, 9.73-Mbp genome shaped for versatility, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 103, 15280–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Romero-Silva M. J., Mendez V., Agullo L., Seeger M. 2013, Genomic and functional analyses of the gentisate and protocatechuate ring-cleavage pathways and related 3-hydroxybenzoate and 4-hydroxybenzoate peripheral pathways in Burkholderia xenovorans LB400, PLoS One, 8, e56038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stanier R. Y., Palleroni N. J., Doudoroff M. 1966, The aerobic pseudomonads: a taxonomic study, J. Gen. Microbiol., 43, 159–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yuhara S., Komatsu H., Goto H., Ohtsubo Y., Nagata Y., Tsuda M. 2008, Pleiotropic roles of iron-responsive transcriptional regulator Fur in Burkholderia multivorans, Microbiology, 154, 1763–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nagata Y., Senbongi J., Ishibashi Y., et al. 2014, Identification of Burkholderia multivorans ATCC 17616 genetic determinants for fitness in soil by using signature-tagged mutagenesis, Microbiology, 160, 883–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Perez-Pantoja D., Donoso R., Agullo L., et al. 2012, Genomic analysis of the potential for aromatic compounds biodegradation in Burkholderiales, Environ. Microbiol., 14, 1091–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nelson K. E., Weinel C., Paulsen I. T., et al. 2002, Complete genome sequence and comparative analysis of the metabolically versatile Pseudomonas putida KT2440, Environ. Microbiol., 4, 799–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miyauchi K., Lee H. S., Fukuda M., Takagi M., Nagata Y. 2002, Cloning and characterization of linR, involved in regulation of the downstream pathway for γ-hexachlorocyclohexane degradation in Sphingomonas paucimobilis UT26, Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 68, 1803–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Harwood C. S., Parales R. E. 1996, The β-ketoadipate pathway and the biology of self-identity, Annu. Rev. Microbiol., 50, 553–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gross R., Guzman C. A., Sebaihia M., et al. 2008, The missing link: Bordetella petrii is endowed with both the metabolic versatility of environmental bacteria and virulence traits of pathogenic Bordetellae, BMC genomics, 9, 449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vedler E., Vahter M., Heinaru A. 2004, The completely sequenced plasmid pEST4011 contains a novel IncP1 backbone and a catabolic transposon harboring tfd genes for 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid degradation, J. Bacteriol., 186, 7161–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Krol J. E., Penrod J. T., McCaslin H., et al. 2012, Role of IncP-1beta plasmids pWDL7::rfp and pNB8c in chloroaniline catabolism as determined by genomic and functional analyses, Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 78, 828–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mukherjee U., Kumar R., Mahato N. K., Khurana J. P., Lal R. 2013, Draft genome sequence of Sphingobium sp. strain HDIPO4, an avid degrader of hexachlorocyclohexane, Genome Announc., 1, e00749–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Davison J. 1999, Genetic exchange between bacteria in the environment, Plasmid, 42, 73–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shintani M., Nojiri H. 2013, Mobile genetic elements (MGEs) carrying catabolic genes, In: Malik A., Grohmann E.,, Alves M. (eds), Management of Microbial Resources in the Environment, Springer: the Netherlands, pp. 167–214. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ohtsubo Y., Ishibashi Y., Naganawa H., et al. 2012, Conjugal transfer of polychlorinated biphenyl/biphenyl degradation genes in Acidovorax sp. strain KKS102, which are located on an integrative and conjugative element, J. Bacteriol., 194, 4237–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shrivastava N., Prokop Z., Kumar A. 2015, Novel LinA-type 3 δ-hexachlorocyclohexane dehydrochlorinase, Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 81, 7553–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Moriuchi R., Tanaka H., Nikawadori Y., et al. 2014, Stepwise enhancement of catalytic performance of haloalkane dehalogenase LinB towards β-hexachlorocyclohexane, AMB Express, 4, 72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pandey R., Lucent D., Kumari K., et al. 2014, Kinetic and sequence-structure-function analysis of LinB enzyme variants with β- and δ-hexachlorocyclohexane, PLoS One, 9, e103632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nagata Y., Ohtsubo Y., Tsuda M. 2015, Properties and biotechnological applications of natural and engineered haloalkane dehalogenases, Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol., 99, 9865–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brassinga A. K., Marczynski G. T. 2001, Replication intermediate analysis confirms that chromosomal replication origin initiates from an unusual intergenic region in Caulobacter crescentus, Nucleic Acids Res., 29, 4441–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sibley C. D., MacLellan S. R., Finan T. 2006, The Sinorhizobium meliloti chromosomal origin of replication, Microbiology, 152, 443–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schaper S., Messer W. 1995, Interaction of the initiator protein DnaA of Escherichia coli with its DNA target, J. Biol. Chem., 270, 17622–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pinto U. M., Pappas K. M., Winans S. C. 2012, The ABCs of plasmid replication and segregation, Nat. Rev. Microbiol., 10, 755–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cevallos M. A., Cervantes-Rivera R., Gutierrez-Rios R. M. 2008, The repABC plasmid family, Plasmid, 60, 19–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.del Solar G., Giraldo R., Ruiz-Echevarria M. J., Espinosa M., Diaz-Orejas R. 1998, Replication and control of circular bacterial plasmids, Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev., 62, 434–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chattoraj D. K. 2000, Control of plasmid DNA replication by iterons: no longer paradoxical, Mol. Microbiol., 37, 467–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Osborn A. M., da Silva Tatley F. M., Steyn L. M., Pickup R. W., Saunders J. R. 2000, Mosaic plasmids and mosaic replicons: evolutionary lessons from the analysis of genetic diversity in IncFII-related replicons, Microbiology, 146, 2267–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cabezon E., Ripoll-Rozada J., Pena A., de la Cruz F., Arechaga I. 2015, Towards an integrated model of bacterial conjugation, FEMS Microbiol. Rev., 39, 81–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Miyazaki R., Sato Y., Ito M., Ohtsubo Y., Nagata Y., Tsuda M. 2006, Complete nucleotide sequence of an exogenously isolated plasmid, pLB1, involved in γ-hexachlorocyclohexane degradation, Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 72, 6923–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Frost L. S., Ippen-Ihler K., Skurray R. A. 1994, Analysis of the sequence and gene products of the transfer region of the F sex factor, Microbiol. Rev., 58, 162–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Boltner D., Moreno-Morillas S., Ramos J. L. 2005, 16S rDNA phylogeny and distribution of lin genes in novel hexachlorocyclohexane-degrading Sphingomonas strains, Environ. Microbiol., 7, 1329–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fuchu G., Ohtsubo Y., Ito M., et al. 2008, Insertion sequence-based cassette PCR: cultivation-independent isolation of γ-hexachlorocyclohexane-degrading genes from soil DNA, Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol., 79, 627–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mahillon J., Chandler M. 1998, Insertion sequences, Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev., 62, 725–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Livny J., Yamaichi Y., Waldor M. K. 2007, Distribution of centromere-like parS sites in bacteria: insights from comparative genomics, J. Bacteriol., 189, 8693–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.D’Argenio V., Petrillo M., Cantiello P., et al. 2011, De novo sequencing and assembly of the whole genome of Novosphingobium sp. strain PP1Y, J. Bacteriol., 193, 4296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Masai E., Kamimura N., Kasai D., et al. 2012, Complete genome sequence of Sphingobium sp. strain SYK-6, a degrader of lignin-derived biaryls and monoaryls, J. Bacteriol., 194, 534–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shintani M., Urata M., Inoue K., et al. 2007, The Sphingomonas plasmid pCAR3 is involved in complete mineralization of carbazole, J. Bacteriol., 189, 2007–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Miller T. R., Delcher A. L., Salzberg S. L., Saunders E., Detter J. C., Halden R. U. 2010, Genome sequence of the dioxin-mineralizing bacterium Sphingomonas wittichii RW1, J. Bacteriol., 192, 6101–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Luo Y. R., Kang S. G., Kim S. J., et al. 2012, Genome sequence of benzo(a)pyrene-degrading bacterium Novosphingobium pentaromativorans US6-1, J. Bacteriol., 194, 907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.