Abstract

The objectives of the present study were to screen for key gene and signaling pathways involved in the production of male germ cells in poultry and to investigate the effects of the transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) signaling pathway on the differentiation of chicken embryonic stem cells (ESCs) into male germ cells. The ESCs, primordial germ cells, and spermatogonial stem cells (SSCs) were sorted using flow cytometry for RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) technology. Male chicken ESCs were induced using 40 ng/mL of bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4). The effects of the TGF-β signaling pathway on the production of chicken SSCs were confirmed by morphology, quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction, and immunocytochemistry. One hundred seventy-three key genes relevant to development, differentiation, and metabolism and 20 signaling pathways involved in cell reproduction, differentiation, and signal transduction were identified by RNA-seq. The germ cells formed agglomerates and increased in number 14 days after induction by BMP4. During the induction process, the ESCs, Nanog, and Sox2 marker gene expression levels decreased, whereas expression of the germ cell-specific genes Stra8, Dazl, integrin-α6, and c-kit increased. The results indicated that the TGF-β signaling pathway participated in the differentiation of chicken ESCs into male germ cells.

Introduction

Due to their plasticity, spermatogonial stem cells (SSCs) have attracted considerable attention among biologists because these cells can be used instead of embryonic stem cells (ESCs) for therapeutic purposes and for generating genetic modifications without having to consider ethical issues and or immune rejection. Ralph and James (1994) transplanted mouse-derived germ cells into the testicles of conspecific mice treated with busulfan and found that spermatogenesis in the testicles of conspecific acceptor mice was remodeled by donor mouse cells. David et al. (1996) extracted SSCs from rat testes, reproduced the cells in vitro and transplanted them into the testes of 10 immunodeficient mice, and induced the production of mature rat sperm in mice.

In other studies, Mito et al. (2004) induced the differentiation of SSCs into ESC-like cells and myocardial cells, whereas Li et al. (2010) induced the differentiation of SSCs into osteoblasts, neurocytes, and adipocytes. The results suggest that SSCs can not only be reprogrammed into pluripotent stem cells but can also be induced into cell lines with different functions. Accordingly, SSCs could be used for genetic modifications and for the treatment of diseases in lieu of ESCs without the associated ethical issues or immune rejection. However, obtaining abundant SSCs by in vitro cultivation and producing functional sperm cells remain problematic.

Although Hayashi et al. (2011) injected primordial germ cells (PGCs) into the convoluted tubules of mice in the absence of endogenous germ cells and produced healthy mouse offspring by mating with normal male mice, they only obtained PGCs in vitro and not induced sperm cells. However, Pan and Hua (2010) and Takuya et al. (2011) also suggested that ESCs can be induced and can differentiate in vitro into male germ cells with marker genes, but pluripotent sperm cells were not achieved. Hence, despite the exciting progress that has been made in the differentiation of ESCs into male germ cells, the lack of a consistent, established induction method or induction system and the low induction efficiency would have to be solved before clinical application. In addition, due to the confines of study materials and the amount of stem cell RNA, no research group has ever conducted a digital gene expression profiling study. Systemic solutions to these issues are essential for the efficient and stable conversion of ESCs to male germ cells, overcoming the uncertainty of in vitro induction, and acquiring plentiful functional sperms.

In the present study, we obtained chicken ESCs, PGCs, and SSCs during chicken embryo development using Rugao yellow chickens. The transcriptomic differences in ESCs, PGCs, and SSCs were analyzed by RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) technology, and some key signaling pathways relevant to germ cell differentiation were detected. Our findings will provide important references for researchers who are addressing the mechanisms of germ cell differentiation and SSC induction efficiency.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

The Rugao yellow chickens used in this study were provided by the Institute of Poultry Science of the Chinese Academy of Agriculture Sciences. Procedures involving the care and use of animals conformed to the U.S. National Institutes of Health guidelines (NIH Pub. No. 85-23, revised 1996) and were approved by the Yangzhou University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Test materials

Eighteen thousand three hundred forty fresh fertilized eggs laid by Rugao yellow chickens bred by the Poultry Institute of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences were used in these experiments. ESCs were isolated from 10,540 eggs (including 4845 male and 4854 female embryos and 841 eggs without embryos), PGCs were isolated from 3400 eggs (including 1594 male and 1556 female embryos and 250 eggs without embryos), and 4400 eggs were used to isolate SSCs. The fertilized fresh eggs used for ESC isolation were collected directly from the farm and contained phase X embryos, whereas the PGCs were collected from the genital ridge of phase 19 chicken embryos (5.5-day hatching), and the SSCs were collected from the testicles of 18-day chicken embryos. The ESCs, PGCs, and SSCs were isolated according to the methods reported by Dai et al. (2007), Qin et al. (2006), and Sun et al. (2008). The sex of the ESCs and PGCs was determined by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and the male and female cells were collected, respectively.

Isolation and culture of chicken ESCs

Fresh fertilized eggs were disinfected by 4% benzalkonium bromide and 75% alcohol. The blunt end of egg was broken by the tweezer and eggwhite was removed, then blastoderm cells at stage X were collected by the spoon method (Dai et al., 2007) in tissue culture dishes and rinsed with Ca2+- and Mg2+-free phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-CMF to remove the yolks and vitelline membrane. After washing with PBS, ESCs were transferred into fresh tissue culture dishes containing PBS with 0.25% trypsin and 0.04% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA). Followed was digestion at 37.0°C for 5–8 minutes, the dissociated cells were collected by centrifugation at 1000 rpm for 8–10 minutes and suspended, then ESCs were maintained in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere at 37.0°C with cytokine culture medium (Table 1), and chicken embryonic fibroblast (CEF) cells were used as the feeder monolayer.

Table 1.

Media Composition for Embryonic Stem Cells, Primordial Germ Cells, and Spermatogonial Stem Cells

| Medium | Composition |

|---|---|

| I | |

| Basal medium | DMEM (sodium pyruvate, l-glutamine) + 10% FBS + 1% nonessential amino acid + 5.5 × 10−5 mol/L β-ethyl alcohol + 2% chicken serum |

| II | |

| ESCs medium | I + 10 ng/mL bFGF + 0.1 ng/mL LIF + 5 ng/mL SCF |

| III | |

| PGCs medium | I + 10 ng/mL bFGF + 0.1 ng/mL LIF + 5 ng/mL SCF + 10 ng/mL hIGF |

| IV | |

| SSCs medium | I + 10 ng/mL bFGF + 0.1 ng/mL LIF + 5 ng/mL SCF + 20 ng/mL GDNF |

bFGF, basic fibroblast growth factor; DMEM, Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium; ESCs, embryonic stem cells; GDNF, glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor; LIF, leukemia inhibitory factor; PGCs, primordial germ cells; SCF, stem cell factor; SSCs, spermatogonial stem cells.

Isolation and culture of PGCs

Briefly, the embryos at 5.5 days were collected in tissue culture dishes and rinsed with Ca2+- and Mg2+-free PBS to remove the yolks. After opening of the abdomen under a stereoscope, the genital ridges and gonads were collected with sharp forceps and transferred into fresh tissue culture dishes containing PBS plus 0.25% trypsin and 0.04% EDTA. Following digestion at room temperature for 5 minutes and repeated pipetting, the dissociated cells were collected by centrifugation at 180 g for 8 minutes and about 1 × 104 PGCs from each embryo were cultured at 37°C, 5% CO2 in a tissue culture dish with cytokine culture medium (Table 1) and CEF cells was used as the feeder monolayer.

Preparation and culture of SSCs

Chicken SSCs were prepared and cultured as the following procedure: testes were obtained sterilely from 18-day-old embryos and the seminiferous tubules mechanically dissected from connective tissues. After digestion with 1 mg/mL type II collagenase (Sigma) in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Gibco) at 37°C for 15–20 minutes, the digested matter was filtered through a 350-μ nylon filter. Following additional digestion with 1 mg/mL collagenase II plus 0.25% trypsin and 0.02% EDTA, SSCs were purified by Percoll density-gradient centrifugation and cultured at 37°C, 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere at 37.0°C with cytokine culture medium (Table 1) and CEF cells was used as the feeder monolayer.

Cell and RNA extraction by flow cytometry

Multiple sorting was used to obtain high-purity cells based on differences in the surface markers of the different cells using flow cytometry-activated cell sorting. The stage-specific embryonic antigen 1-positive and sex determining region Y-box 2-positive (SSEA-1+ [ab16285; Abcam, Shanghai, China] + SOX2+ [ab97959; Abcam]) ESCs, SSEA-1+ + c-kit+ (ab5505; Abcam) PGCs, and integrin-α6+ (ab20142; Abcam) + integrin-β1+ (ab3167; Abcam) SSCs were collected, respectively. RNA was extracted from the selected cells and submitted for Illumina sequencing after quality control.

RNA-seq experiments

The transcriptomic sequencing of RNA was conducted by Shanghai OE Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Total RNA was diluted in diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC) water and denatured at 65°C to unfold the secondary structure. Oligo (dt) magnetic beads were used to enrich mRNA, then the mRNA was eluted by heating and fragmented using the fragmentation buffer. The first cDNA strand was synthesized using random hexamers with mRNA as the template. The second cDNA strand was synthesized by adding the buffer solution, dNTPs, RNase H, and DNA polymerase I. The cDNA was purified using magnetic beads and eluted with the elution buffer. The cDNA was then subjected to an end repair process, and the sequencing joints were connected. After quality control, the library was sequenced using the Illumina HiSeq™ 2000 system.

Data analysis

The quality of raw reads resulting from RNA-seq was tested using FastQC (www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/), and clean reads were aligned against the reference sequence using SOAP2 (http://soap.genomics.org.cn/soapaligner.html). Gene expression levels were analyzed statistically using the RPKM method. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were filtered out by repeatability analysis based on the expression level results. Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis and pathway enrichment analysis were determined based on the DEGs (|log2| > 1) using the Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery (DAVID; http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/home.jsp), FunNet (www.funnet.info/), and WEGO (http://wego.genomics.org.cn/cgi-bin/wego/index.pl). Hierarchical cluster analysis was conducted using the Eisen Cluster software based on log2 DEG values. Hierarchical clustering was determined using Euclidean distance, and the mean distance was used for cluster analysis. The FUNNET database (www.funnet.info/) was used to screen the candidate key genes for regulatory network analysis. For all analyses, a p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was extracted from three cell types (ESCs, PGCs, and SSCs) and the cells induced by bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4) in vitro using TRIzol® reagent (Tiangen, Beijing, China), and the reverse transcription kit was used to synthesize cDNA (Tiangen). Seven signal molecules from RNA-seq results of transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) signaling pathway were selected for quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR). The primers used for qRT-PCR are listed in Table 2. Assays were conducted using the SuperReal PreMix Color (SYBR Green) (FP215; Tiangen) and performed on an ABI two-step RT-PCR system (Applied Biosystems 7500) with diluted first-strand cDNA according to the manufacturer's instructions. For each reaction, 0.1 ng of total RNA was used as input. The qRT-PCR mixtures included 1 μL of cDNA, 10 μL of 2 × SuperReal Color PreMix, 0.6 μL of the forward and reverse primers (10 μmol/L), 0.4 μL of 50 × ROX Reference Dye, and RNase-free ddH2O in a total reaction mixture volume of 20 μL. The mixtures were put into a clear tube (0.2 mL thin wall; Axygen). The reactions comprised 40 cycles of the following program: 95°C for 15 minutes, followed by 95°C for 10 seconds, 60°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 32 seconds. The β-actin gene (housekeeping genes) was served as an internal reference gene, and all reactions were performed in triplicate. Gene expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method.

Table 2.

Primers for Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction Identification of Transforming Growth Factor Beta Signaling Pathway Genes

| Gene name | GenBank Accession No. | Primer pairs (5′-3′) | The exon locations | Annealing temperature (°C) | Fragments (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMP4 | NM_205237 | F: GGGAGATGATGGCTATGTG | Exon 1, 2 | 52 | 117 |

| R: TTCTTGGGTGTTCCTGATT | |||||

| BMPR1A | NM_205357 | F: CCTGACCAAAAGAAACAA | Exon 2, 3 | 48 | 148 |

| R: CCTCAATGATAGCAAAGC | |||||

| BMPR1B | NM_205132 | F: GTCAGTGCCACCACCATT | Exon 1, 2 | 53 | 139 |

| R: TCCGAGCCCTCTAATCCT | |||||

| BMPRII | NM_001001465.1 | F: AAGGACCCGTATCAGC | Exon 1, 2 | 59 | 299 |

| R: TCAGGAGGTGGGAAGT | |||||

| TGF-β2 | NM_001031045.1 | F: CACCACCATTGTCCTGAG | Exon 2, 3 | 51 | 133 |

| R: AGTCCGAGCCCTCTAATC | |||||

| INHBA | NM_205396 | F: ACAGACCTAACATCACCCAG | Exon 1, 2 | 51 | 266 |

| R: GAAGAGCCATACTTCAGCA | |||||

| ACVR1 | NM_204560 | F: GGGGTCTTTGTATGACTATCT | Exon 6, 7 | 60 | 238 |

| R: CTGGTTCGTGCTTTGG | |||||

| C-kit | D13225.1 | F: GCGAACTTCACCTTACCCGATTA | Exon 7, 8 | 64 | 150 |

| R: TGTCATTGCCGAGCATATCCA | |||||

| Dazl | NM_204218.1 | F: TGTCTTGAAGGCCTCGTTTG | Exon 1, 2 | 61 | 138 |

| R: CATATCCTTGGCAGGTTGTTGA | |||||

| Integrin-α6 | NM_205289.1 | F: GCTGGAAACATGGACCTGGATAA | Exon 9, 10 | 64 | 145 |

| R: TTCAGGTCAAGTTTGTCAGGCTGTA | |||||

| Stra8 | JX204292.1 | F: GGAAGAAGACGGAAAGCC | Exon 1, 2 | 54 | 141 |

| R: ACCTCCTCAGCGGAAACA | |||||

| β-actin | L08165.1 | F: CAGCCATCTTTCTTGGGTAT | Exon 3, 4 | 60 | 164 |

| R: CTGTGATCTCCTTCTGCATCC |

In vitro induction

To test the role of the TGF-β signaling pathway in the differentiation of male germ cells, BMP4 from the TGF-β superfamily was used to induce the differentiation of Rugao yellow chicken ESCs into male germ cells. Third generation ESCs grown in wells were transferred to a 24-well plate containing supporting cells. In each well, 105 cells were inoculated with 40 ng/mL BMP4 in the induction medium. After inoculation, the cells were collected every third day, and the effects of induction were determined by morphology, qRT-PCR, and immunocytochemistry.

Immunocytochemistry

The induced cells were inoculated on cover slips treated by polylysine. Cells climbing on the slice were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 minutes, rinsed with PBS three times, and then incubated at 37°C for 1 hour in 10% bovine serum albumin-PBS. After incubation, the primary antibodies anti-integrin-β1 (ab3167; Abcam), anti-c-kit (ab5505; Abcam), anti-Dazl (ab34139; Abcam), and anti-integrin-α6 (ab20142; Abcam) were added at a concentration of 1:200. The slices were incubated at 37°C for 2 hours and then overnight at 4°C. The resulting slices were rinsed with PBST three times, sealed in glycerol, and observed and photographed using an inverted microscope.

Results

Morphology and sex identification of ESCs, PGCs, and SSCs

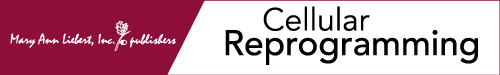

The volume of the chicken ESCs was relatively small, their shapes were round or elliptical, and they typically had one or more nuclei that were large in proportion to the cytoplasm, which was minimal. The border of the ESCs clones was very clear and typically took the form of a bird's nest or island. The volume of the PGCs was very large and their nuclei were very clear. The halo around each of the PGCs was also very clear and it developed from the ESCs. The volume of the SSCs was also very large. Furthermore, the SSCs grew closely and the cloned cells resembled the form of a grape cluster (Fig. 1A). The sexes of the chicken ESCs and PGCs were clearly identified by the results of amplification using CHD-W-specific primers. The female (ZW) had two bands at 600 and 450 bp, respectively, whereas the male (ZZ) had only one band at 600 bp (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

The morphology and sex of ESCs, PGCs, and SSCs. (A) AKP staining of ESCs, PGCs, and SSCs (400 × ); (B) PCR amplification results of CDH-W gene. ESCs, embryonic stem cells; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; PGCs, primordial germ cells; SSCs, spermatogonial stem cells.

Signaling pathway and DEGs in ESCs-male, PGCs-male, and SSCs

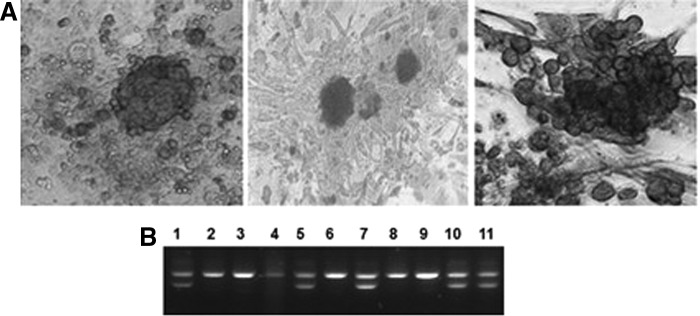

The basic screening conditions for DEGs were set at p ≤ 0.005, FDR ≤0.001, and differences greater than twofold. The preliminary scatter plots of DEGs in ESCs, PGCs, and SSCs revealed that the number of upregulated genes was greater than the number of downregulated genes (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, there were 7697 genes that were differentially expressed in ESCs and PGCs, including 4187 upregulated genes and 3510 downregulated genes (Fig. 2B). In addition, there were 7868 DEGs in ESCs and SSCs, including 4944 upregulated genes and 2924 downregulated genes, and there were 6226 DEGs in PGCs and SSCs, including 3876 upregulated genes and 2350 downregulated genes. Following GO analysis, it was discovered that these DEGs could be generalized into three processes, including biological processes, cellular components, and molecular function (Fig. 2C).

FIG. 2.

DEGs screening in ESCs-male, PGCs-male, and SSCs, and GO function annotation. (A) Scattered plot of gene expression; graph of the expressed genes; (B) statistic graph of DEGs; (C) DEGs screening of ESCs-male, PGCs-male, and SSCs, and GO function analysis. For ESCs versus PGCs, DEGs annotated to cell process were the most in terms of biological process classification, and they were 2316. In the cellular components, DEGs annotated to cell and cell parts were the most, and they were both 2828. In molecular function, DEGs annotated to binding were the most, and they were 2343. For ESCs versus SSCs, DEGs annotated to cell process were the most in terms of biological process classification, and they were 2399. In cellular components, DEGs annotated to cell and cell parts were the most, and they were both 2955. In molecular function, DEGs annotated binding were the most, and they were 2399. For PGCs versus SSCs, DEGs annotated to biological process, cellular components, and molecular function were 28, 12, and 15, respectively. In the biological process classification, DEGs annotated to cell process were the most, and they were 1891. In the cellular components, DEGs annotated to cell and cell parts were the most, and they were both 2360. In molecular function, DEGs annotated to binding were the most, and they were 1884. DEGs, differentially expressed genes; GO, Gene Ontology.

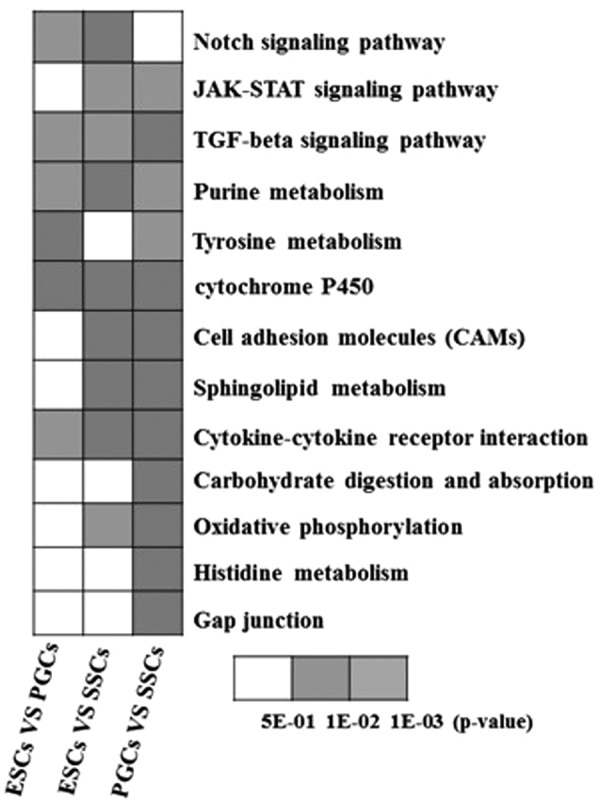

Enrichment analysis using KEGG PATHWAY mapping was performed based on 2668 of the DEGs detected, and 72 signaling pathways with significant expression were identified. These 72 signaling pathways were subjected to functional cluster analysis, of which 22 were putative signaling pathways involved in the development of chicken male germ cells (Fig. 3 and Table 3). In particular, the TGF-β signaling pathway, purine metabolism signaling pathway, cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction signaling pathway, and the cell adhesion molecule signaling pathway were significantly expressed.

FIG. 3.

Enrichment results of KEGG signaling pathway in DEGs revealed by RNA-seq. RNA-seq, RNA sequencing.

Table 3.

Enrichment of Pathways Relevant to Differentially Expressed Genes

| Pathway ID | Pathway | No. of genes detected |

|---|---|---|

| ko04330 | Notch signaling pathway | 58 |

| ko00230 | Purine metabolism | 174 |

| ko00532 | Glycosaminoglycan biosynthesis-chondroitin sulfate | 18 |

| ko04974 | Protein digestion and absorption | 80 |

| ko00350 | Tyrosine metabolism | 37 |

| ko00980 | Metabolism of xenobiotics by cytochrome P450 | 35 |

| ko04514 | CAMs | 98 |

| ko00600 | Sphingolipid metabolism | 65 |

| ko04060 | Cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction | 102 |

| ko00040 | Pentose and glucuronate interconversions | 23 |

| ko04973 | Carbohydrate digestion and absorption | 36 |

| ko00190 | Oxidative phosphorylation | 62 |

| ko00340 | Histidine metabolism | 19 |

| ko04630 | JAK-STAT signaling pathway | 103 |

| ko03050 | Proteasome | 19 |

| ko00480 | Glutathione metabolism | 27 |

| ko04540 | Gap junction | 56 |

| ko04350 | TGF-β signaling pathway | 74 |

| ko00140 | Steroid hormone biosynthesis | 38 |

| ko00260 | Glycine, serine, and threonine metabolism | 31 |

| ko00190 | Oxidative phosphorylation | 70 |

| ko00250 | Alanine, aspartate, and glutamate metabolism | 22 |

CAMs, cell adhesion molecules; TGF-β, transforming growth factor beta.

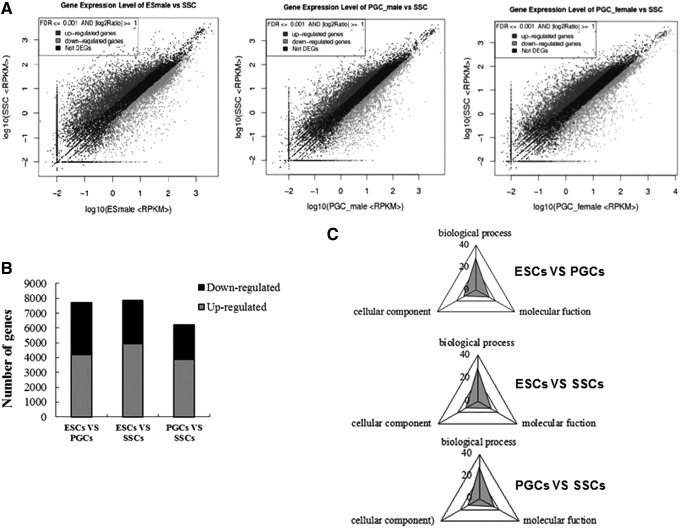

Dynamic analysis of DEGs in the TGF-β signaling pathway

Statistical analysis of the expression levels of DEGs in the TGF-β signaling pathway, as well as the exploration of key signal molecules and their functional mechanisms in the TGF-β signal transduction pathway, would aid in the construction of the regulatory network that governs germ cell differentiation in male chickens. In addition, the results will provide information for elucidating the mechanisms of germ cell differentiation. Therefore, the present study will provide a comprehensive investigation into the dynamic expression of the TGF-β signaling pathway.

Thirty-three DEGs were enriched in the TGF-β signaling pathway. These DEGs were either switched on or off or were upregulated or downregulated along the developmental and differential axes of ESCs, PGCs, and SSCs (Fig. 4B). Eight members of the BMP subfamily of TGF-β coordinators participated in the regulation process. All of these BMP subfamily members, except for BMP7, were continuously downregulated. Conversely, the expression of BMP5 and AMH was continuously upregulated. The expression of BMP4, GDF6/7, GDF5, and Vgr-1 was upregulated, but their expression was slightly downregulated in SSCs.

FIG. 4.

Cluster results of DEGs in ATGF-β signaling pathway.

Of the members of the TGF-β subfamily, only TGF-β2 participated in the regulation process. The expression of inhibitor βA (NHBA), a member of the activin subfamily, was continuously upregulated, and its expression level was the highest in SSCs. However, the expression of the protein Nodal, which is an inhibitor of TGF-β signaling, was continuously downregulated. The expression levels of BMPRIA, BMPRIB, and BMPRII, which are receptors in the BMP subfamily, were downregulated in PGCs but upregulated in SSCs.

Furthermore, the expression levels of the TGF-β subfamily receptors TGF-βRI and TGF-βRII were the highest in SSCs. The expression levels of ActivinRI and ActivinRII, receptor activins in the activin subfamily, were continuously downregulated, which could potentially be attributed to the continuous upregulation of inhibin-βA (INHBA). The expression level of the Nodal protein receptor was continuously downregulated, which was consistent with the Nodal protein expression level. However, the main regulator of the TGF-β signaling pathway was the Smad proteins. In the present study, the expression levels of Smad5 and Smad9 were the highest in SSCs, which was consistent with the BMPRI receptor. The expression levels of Smad2 and Smad3, which were involved in the regulation of the TGF-β and activin subfamily receptors, tended to increase, whereas Smad6 and Smad7 inhibited the regulatory role of Smad5, Smad9, Smad2, and Smad3. Similar to Smad2 and Smad3, the expression levels of Smad6 and Smad7 tended to increase and they negatively regulated the transduction of the TGF-β signaling pathway.

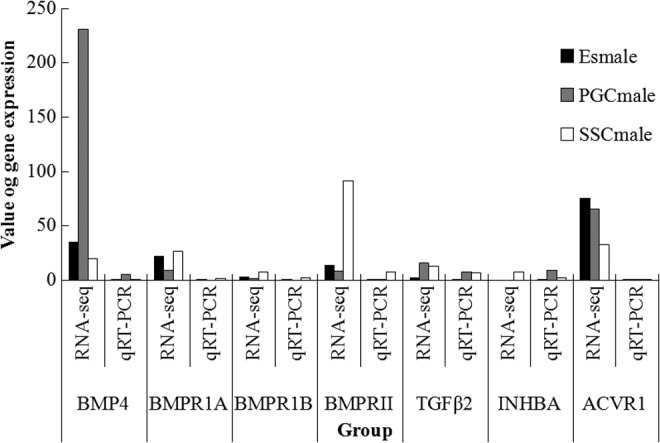

Seven signaling molecules in the TGF-β signaling pathway were analyzed by qRT-PCR, and the results indicated that their expression levels were consistent with the RNA-seq results, which suggested the reliability of the sequencing results (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

RNA-seq results as tested by qRT-PCR. qRT-PCR, quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction.

BMP4 promotes ESCs to differentiate into male germ cells

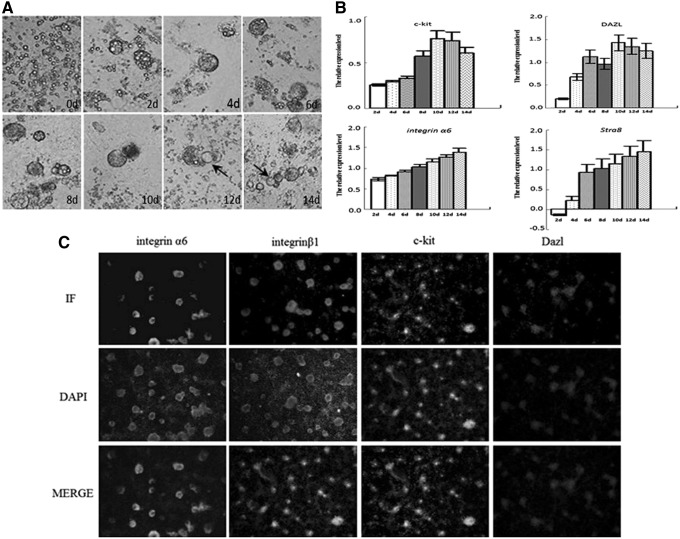

BMP4 is a member of the TGF-β superfamily that can effectively activate the TGF-β signaling pathway. When ESCs were induced by BMP4, embryoid bodies appeared on day 4, enlarged and manifold on days 6–8, but disintegrated and dwindled to round cells on day 10. The germ cell-like cells started to arise around the disintegrated embryoid bodies on day 12, and the number of germ cell-like cells increased on day 14 and formed an aggregate (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

BMP4 promotes ESCs to differentiate into male germ cells. (A) Cell morphology after BMP4 treatment (400 × ); (B) expression of genes relevant to BMP4 induction as tested by qRT-PCR; and (C) protein expression as tested by immunocytochemistry (400 × ). BMP4, bone morphogenetic protein 4.

The expression level of the ESCs was set at 1. After BMP4 induction, the expression levels of germ cell-specific genes were increased. During induction, the expression level of Dazl was the highest on days 10–12, but decreased slightly on day 14. The expression of Stra8 was first noted on day 4 and reached maximal levels at day 14, but its expression level did not exceed the level observed in the SSCs. The expression level of integrin-α6 increased significantly on day 8 after induction and was the greatest on day 14. The initial expression level of c-kit did not change markedly; however, expression of c-kit started to increase on day 8, reached maximal levels on day 10, and declined thereafter.

The expression levels of the Dazl, integrin-α6, integrin-β1, and c-kit proteins in the ESCs induced by BMP4 were determined by immunocytochemistry. Positive Dazl, integrin-α6, integrin-β1, and c-kit clones could be observed, but the expression of the relevant proteins was not detected in the control group (Fig. 6).

Discussion

Germ cells play important roles in the transfer of genetic information between generations during sexual reproduction. Furthermore, germ cells can be used instead of ESCs to treat diseases and to generate genetic modifications without associated ethical issues and problems related to immune rejection. Through in-depth germ cell research and the development of in vitro ESC induction methods, the differentiation of ESCs into PGCs and spermatogonia has been induced by cytokines, chemical reagents, and transgenic methods (Cao, 2009; Lou and Dean, 2007; Olayioye et al., 2000). However, the signaling networks involved in the regulation of this process remain unclear. In recent years, studies concerning the ontogenesis and differentiation of germ cells have received considerable attention. In the present study, the transcriptomes of ESCs, PGCs, and SSCs were sequenced by RNA-seq, the DEGs were annotated and their signaling pathways enriched using KEGG PATHWAY mapping, and the TGF-β signaling pathway was analyzed and tested. The results suggested that the TGF-β signaling pathway played an important role in the differentiation of male germ cells in chickens.

The TGF-β superfamily of proteins is a group of dimeric proteins with conserved domains that comprise at least 30 secreted signaling molecules. Furthermore, members of the TGF-β superfamily of proteins can be divided into three categories according to their structure and function, including TGF-βs, BMPs, and cytokines (Yue and Mulder, 2001). TGF-β and BMP signaling play key roles in regulating the differentiation of germ cells. In addition, Smad (mothers against decapentaplegic) proteins are important downstream signaling molecules in TGF-β signaling and serve as ligands that transduce signals from the cytoplasm to the nucleus.

TGF-β downstream effector cell cycle-related factors that play a role in important biological functions such as embryonic development, cell proliferation, differentiation, and extracellular matrix formation have been found, including transcription factors, apoptosis-related factors, interorganizational quality ingredients, and four other categories (Nohe et al., 2004). Although research has shown that the TGF-β signaling pathway occurs in germ cells, the precise mechanisms by which the TGF-β signaling pathway is involved in the in vivo pathogenesis of germ cells have not been elucidated. Hence, experiments aimed at defining the in vivo function of the TGF-β signaling pathway are necessary.

Studies have shown that TGF-β1 and TGF-β3 are expressed in mouse embryonic testes. A study by Kawase et al. (2004) demonstrated that BMP signaling in male germ stem cells plays a key role in maintaining the mutant, two BMP genes, dpp and gbb, maintain reproductive growth, and that BMP signaling may block the differentiation inhibitory factor bam, which promotes the differentiation of ESCs. Furthermore, Ohinata et al. (2009) reported that BMP/Smad plays an important role in germ cell development and that knockout of BMP8b and BMPZ in PGCs can cause deletions. Ohinata et al. (2009) also reported that BMP4 signaling in the embryonic ectoderm and mesoderm can induce the expression of Blimp-1 and Prdml4, two key specialized PGC regulatory genes, thus ensuring that the proximal epiblast cells develop into germ cells.

Zhao et al. (1996, 1998) and Hu et al. (2004) reported that mutations in Bmp7, Bmp8a, Bmp8b, and Bmp4 block spermatogenesis. In addition, Dudley et al. (2007) confirmed that the quantity of PGCs is regulated by the BMP4 signal. A separate study by Shimasaki et al. (2004) has shown that the synergy of BMP4 and BMP8b can contribute to the mesodermal cell PGCs, whereas gene knockout experiments have demonstrated that BMP4 plays an important role in the formation of PGCs (Ohinata et al., 2009).

Wei et al. (2008) used BMP4 to induce the differentiation of Stella-GFP ESCs into germ cells and noted that the GFP-positive cell rate reached 2.96%. Compared with other concentrations of BMP4 used, 50 ng/mL BMP4 was the most effective for induction. Hamidabadi et al. (2011) demonstrated that a 5–10 ng/mL concentration of BMP4 is beneficial for the differentiation of ESCs. Nonetheless, the results of this study indicated that 40 ng/mL BMP4 could induce cytopoiesis in male chicken ESCs.

Stéphanie et al. (2010) detected TGF-β receptors and their ligands during development in mouse testes and found that TGF-β1 is not expressed in testes, but that TGF-β3 is expressed in each stage of Sertoli cell development and spermatogonia and that only TGF-β2 exhibited changes at different developmental stages of spermatogonia, suggesting that TGF-β2 is involved in germ cell proliferation. Furthermore, a TGF-βRII knockout experiment likewise verified that TGF-β plays an important role in germ cell proliferation and apoptosis. Stéphanie et al. (2010), Memon et al. (2008), and others have also shown that TGF-β1 and TGF-β3 are both expressed in mouse embryonic testes, and Mai et al. (2010) noted that TGF-β is necessary for testis development following a functional defect analysis in mice.

In a separate study, Zhang et al. (2012) showed that the Smad4 protein is widely expressed in the cytoplasm of testicular germ cells and that it regulates testicular development and spermatogenesis by BMP signaling. In addition, Miles et al. (2013) indicated that TGF-β signaling plays a key role in the formation of testes cords and that ALK4 and ALK7 promote differentiation of male germ cells by Activin DAL receptor signaling by inhibiting TGF-β downstream signaling of ALK4, ALK5, and ALK7 expression.

Early findings of our research group revealed that inhibiting the TGF-β signaling pathway led to significantly decreased expression of Smad2 and Smad5 and that the proportion of germ cells and expression of related reproductive marker genes likewise decreased. In addition, our prior research has indicated that inhibiting the TGF-β signaling pathway also suppressed BMP4 induction, which further confirmed the theory that the TGF-β signaling pathway is a key regulator of the differentiation of chicken ESCs to male germ cells (unpublished results). In addition, this study also explored the BMP4 mechanisms involved in inducing the differentiation of chicken ESCs into male germ cells and provided in vitro experimental evidence to aid in establishing the model of BMP4 induction of chicken ESCs to male germ cells, as well as verified the signaling pathways involved. Likewise, the current study provides the theoretical basis for optimizing the system for inducing the differentiation ESCs to germ cells and clarified the occurrence and development of germ cells.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31301959, 31472087); Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province; Science and technology project of Yangzhou (YZ2015105). A Project Funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions.

Authors’ Contributions

Y.Z. and B.L. conceived and designed the experiments; Q.Z. and W. Z. performed the experiments; Y.Z., D.L., and Y.W. analyzed the data; C.L., B.T., T.X., and M.W. contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools; and Y.Z. wrote the article. K.W. supplied the fresh fertilized eggs to separate the ESCs.

Author Disclosure Statement

No conflict of interest exists in the submission of this article, and this article is approved by all authors for publication.

References

- Cao X. (2009). New DNA-sensing pathway feeds RIG-I with RNA. Nat. Immunol. 10, 1049–1051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai J.M., He X.H., Zhao W.M., Wu X.S., and Li B.C. (2007). Isolation and cultivation of chicken embryonic stem cells. Chin. J. Anim. Sci. 43, 15–19 [Google Scholar]

- David E.C., Mary R.A., Shanna D.M., Robert E.H., and Ralph L.B. (1996). Rat spermatogenesis in mouse testis. Nature. 381, 418–421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudley B.M., Runyan C., Takeuchi Y., Schaible K., and Molyneaux K. (2007). BMP signaling regulates PGC numbers and motility in organ culture. Mech. Dev. 124, 68–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamidabadi H.G., Pasbakhsh P., Amidi F., Soleimani M., Forouzandeh M., and Sobhani A. (2011). Functional concentrations of BMP4 on differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells to primordial germ cells. Int. J. Fertil. Steril. 5, 104–109 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi K., Ohta H., Kurimoto K., Aramaki S., and Saitou M. (2011). Reconstitution of the mouse germ cell specification pathway in culture by pluripotent stem cells. Cell. 146, 519–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J., Chen Y.X., Wang D., Qi X.X., Li T.G., Hao J., Yuji M., David L.G., and Zhao G.Q. (2004). Developmental expression and function of Bmp4 in spermatogenesis and in maintaining epididymal integrity. Dev. Biol. 276, 158–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawase E., Wong M.D., Ding B.C., and Xie T. (2004). Gbb/Bmp signaling is essential for maintaining germline stem cells and for repressing bam transcription in the Drosophila testis. Development. 131, 1365–1375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B.C., Wang X.Y., Tian Z.Q., Xiao X.J., Xu Q., Wei C.X., Y, F., and Sun H.C., and Chen G.H. (2010). Directional differentiation of chicken spermatogonial stem cells in vitro. Cryotherapy. 12, 326–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou H., and Dean M. (2007). Targeted therapy for cancer stem cells: The patched pathway and ABC transporters. Oncogene. 26, 1357–1360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mai A.S., Ruth M.E., Alexandra U., Hui K.C., Chris S., Mike G., Kate L., Jock K.F., and Kaye L.S. (2010). Fetal testis dysgenesis and compromised Leydig cell function in Tgfbr3 (betaglycan) knockout mice. Biol. Reprod. 82, 153–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Memon M.A., Anway M.D., Covert T.R., Uzumcu M., and Skinner M.K. (2008). Transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ1, TGFβ2 and TGFβ3) null-mutant phenotypes in embryonic gonadal development. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 294, 70–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles D.C., Wakeling S.I., Stringer J.M., Van den Bergen J.A., Wilhelm D., Sinclair A.H., and Western P.S. (2013). Signaling through the TGF beta-activin receptors ALK4/5/7 regulates testis formation and male germ cell development. PLoS One., 8 e54606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mito K.S., Kimiko I., Jiyoung L., Momoko Y., Narumi O., Hiromi M., Shiro B., Takeo K., Yasuhiro K., Shinya T., Megumi T., Ohtsura N., Mitsuo O., Toshio H., Tatsutoshi N., Fumitoshi I., Atsuo O., and Takashi S. (2004). Generation of pluripotent stem cells from neonatal mouse testis. Cell. 119, 1001–1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nohe A., Keating E., Knaus P., and Petersen N.O. (2004). Signal transduction of bone morphogenetic protein receptors. Cell. Signal. 16, 291–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohinata Y., Ohta H., Shigeta M., Yamanaka K., Wakayama T., and Saitou M. (2009). A signaling principle for the specification of the germ cell lineage in mice. Cell. 137, 571–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olayioye M.A., Neve R.M., Lane H.A., and Hynes N.E. (2000). The ErbB signaling network: Receptor heterodimerization in development and cancer. EMBO J. 19, 3159–3167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan S.H., and Hua J.L. (2010) Study on mouse embryonic stem cells differentiation into male germ cells. Master thesis, North-West A and F University [Google Scholar]

- Qin J., Cai L.L., Li B.C., Han W., Zhou G.Y., Wu H., and Sun S.Y. (2006). In vitro cultivation of chicken primordial germ cells (PGCs). Chin. J. Vet. Sci. 4, 444–447 [Google Scholar]

- Ralph L.B., and James W.Z. (1994). Spermatogenesis following male germ-cell transplantation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91, 11298–11302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimasaki S., Moore R.K., Otsuka F., and Erickson G.F. (2004). The bone morphogenetic protein system in mammalian reproduction. Endocr. Rev. 25, 72–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stéphanie G.M., Myriam A., Isabelle A., Sébastien M., Pierre F., Hervé C., Paul-Henri R., and René H. (2010). TGFβ signaling in male germ cells regulates gonocyte quiescence and fertility in mice. Dev. Biol. 342, 74–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S.Y., Li B.C., Wei C.X., Qin J., Wu H., Zhou G.Y., and Chen G.H. (2008). In vitro cultivation of chicken spermatogonial stem cells. Chin. J. Vet. Sci. 1, 102–105 [Google Scholar]

- Takuya S., Kumiko K., Ayako G., Kimiko I., Narumi O., Atsuo O., Yoshinobu K., and Takehiko O. (2011). In vitro production of functional sperm in cultured neonatal mouse testes. Nature. 471, 504–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei W., Qing T., Ye X., Liu H., Zhang D., Yang W., and Deng H. (2008). Primordial germ cell specification from embryonic stem cells. PLoS One., 3 e4013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue J., and Mulder K.M. (2001). Transforming growth factor-β signal transduction in epithelial cells. Pharmacol. Ther. 91, 1–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.J., Wen X.X., Zhao L., and He J.P. (2012). Immunolocalization of Smad4 protein in the testis of domestic fowl (Gallus domesticus) during postnatal development. Acta Histochem, 114, 429–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao G.Q., Deng K., Labosky P.A., Liaw L., and Hogan B.L. (1996). The gene encoding bone morphogenetic protein 8B is required for the initiation and maintenance of spermatogenesis in the mouse. Genes Dev. 10, 1657–1669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao G.Q., Liaw L., and Hogan B.L. (1998). Bone morphogenetic protein 8A plays a role in the maintenance of spermatogenesis and the integrity of the epididymis. Development. 125, 1103–1112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]