Abstract

Purpose

Faculty vitality is integral to the advancement of higher education. Strengthening vitality is particularly important for mid-career faculty, who represent the largest and most dissatisfied segment. The demands of academic medicine appear to be another factor that may put faculty at risk of attrition. To address these issues, we initiated a ten-month mid-career faculty development program.

Methods

A mixed-methods quasi-experimental design was used to evaluate the program's impact on faculty and institutional vitality. Pre/post surveys compared participants with a matched reference group. Quantitative data were augmented by interviews and focus groups with multiple stakeholders.

Results

At the program's conclusion, participants showed statistically significant gains in knowledge, skills, attitudes, and connectivity when compared to the referents.

Conclusion

Given that mid-career faculty development in academic medicine has not been extensively studied, our evaluation provides a useful perspective to guide future initiatives aimed at enhancing the vitality and leadership capacity of mid-career faculty.

INTRODUCTION

The American healthcare enterprise is threatened by increasing levels of burnout. Burnout has been negatively correlated with providers’ health, productivity, professionalism, compassion, and retention, as well as patients’ satisfaction and adherence (Shanafelt, 2009). According to the 2015 Medscape Physician Lifestyle Report, 46% of all physicians reported experiencing burnout, which was up from 40% in 2013 (Peckham, 2015). Mid-career physicians report the highest rates of burnout, emotional exhaustion, and low vitality (Dyrbye et al., 2013). They also report working more hours, having lower satisfaction with their work-life balance and their chosen specialty, and being more likely to leave the field of medicine in comparison to their early-career and late-career counterparts; these trends are experienced across specialties and in both women and men (Dyrbye et al., 2013).

Beyond academic medicine, diminishing vitality is a growing concern among mid-career faculty. Mid-career faculty typically constitute the largest and most productive segment of the faculty, yet they tend to be the most dissatisfied (Romano, Hoesing, O'Donovan, & Weinsheimer, 2004). The common themes reported by mid-career faculty across various schools and disciplines include high expectations, neglect, relief, reassessment, and adaptation (Baldwin, DeZure, Shaw, & Moretto, 2008). Baldwin and Chang (2006, p.28) describe mid-career faculty as “the keystone of the academic enterprise.” However, many faculty report reaching a professional crisis or apex during mid-career. A sense of career limitations may result in the questioning of personal and professional identity (Baker, 2005). In addition, mid-career faculty members often find decreased opportunities for mentoring, feedback, and professional development, and express feelings of isolation (Canale, Herdklotz, & Wild, 2013).

Since mid-career faculty and the healthcare sector are both vulnerable to burnout, academic medicine may be a particularly risky backdrop for attrition (Zwack & Schweitzer, 2013). Faculty attrition creates multiple downstream problems for academic health centers. A 2007 survey found that 42% of medical school faculty members were seriously considering leaving academic medicine within the next five years, with current attrition rates being disproportionately high for women and minorities (Lowenstein, Fernandez, & Crane, 2007). Whereas physicians outside of academia are able to focus solely on patient care, academic healthcare providers have the additional responsibility of teaching and training the next generation (Straus, Soobiah, & Levinson, 2013), while working longer hours at lower salaries (Cropsey et al., 2008). In academic medicine, attrition is costly in morale, institutional expertise, and patient access. Furthermore, the economic burden of one faculty departure ranges from $100,000 to $600,000 (Schloss, Flanagan, Culler, & Wright, 2009). In turn, the issue of retention poses a substantive threat to the educational infrastructure of health professions.

The significance of vitality for mid-career faculty in academic medicine suggests the need for targeted faculty development programs. Fortunately, there has been increased focus on faculty development in the context of academic medicine. In 2006, Steinert et al. performed a meta-analysis of faculty development programs in medical schools, finding that positive changes in attitude, increased knowledge, and gains in teaching skills were most commonly associated with programs designed around experiential learning, diverse instructional methods, nurturing of peer relationships, and provision of feedback. Although Steinert's work highlights the effectiveness of faculty development on medical campuses, there appears to be a paucity of faculty development initiatives designed specifically for the cross section of academic medicine and mid-career, which marks a clear need for the next stage of research in this arena.

To address the needs of mid-career faculty development in academic medicine, our institution initiated the Academy for Collaborative Innovation & Transformation (ACIT). ACIT was designed to have a positive influence on mid-career faculty engagement, address pressing needs identified by institutional leaders, and increase faculty capacity to innovate and collaborate effectively across disciplines.

Program

ACIT included mid-career faculty members, defined as late assistant (7+ years at rank) and associate professors. Participants were drawn from the School of Medicine and School of Public Health. The School of Medicine is a private, urban medical school with a safety net hospital serving as its primary teaching hospital. ACIT's pilot program ran from January to November 2014. To enable the participants to fully engage, all clinical faculty members were given 10% protected time during the program. There were three curricular components: 1) Six two-day, off campus, interactive learning modules facilitated by internal and external faculty, 2) Peer-mentoring networks (“learning communities”) focused on interpersonal accountability, and 3) Multidisciplinary group projects (“capstones”) addressing institutional needs.

In preparation for the program, a Mid-Career Faculty Development Task Force established a list of 16 core competencies that were advanced as essential for the ongoing success of a mid-career faculty member. The development and strengthening of these competencies were the foundation of ACIT's interactive, case-based curriculum.

Appraisal of strengths and areas for growth

Understanding disruptive innovation

Change leadership

Managing staff and team-building

Communicating effectively

Professional resiliency

Strategic partnerships and alliances

Educating the next generation

The value proposition: improving quality & efficiency

Formulating individual development plan

Developing organizational savvy

Scholarship and dissemination

Leveraging diversity and inclusion

Achieving work/life integration

Creating cultures of innovation

Developing financial acumen

The curriculum was designed to enable participants to accomplish four primary learning goals: 1) self-reflect and pursue an individual development plan; 2) connect longitudinally to the peer cohort and to the larger organization; 3) collaborate effectively with colleagues across disciplines, sectors, and roles; and 4) enhance ability to implement transformative work.

Also embedded in each module was a “Conversation Café,” which was a 90-minute session in the afternoon of the first day of the module for participants to engage with institutional leaders and other inspirational figures in an informal context about big picture issues (e.g. the future of academic medical centers, visionary leadership, improving the quality of healthcare, and strategic collaborations with the community). The Conversation Cafes were an opportunity for mid-career faculty to benefit from the experience and vision of inspirational leaders and for the leaders to engage with faculty members they may not otherwise interact with, thus creating value and potential opportunities for mentoring and future collaborations on both sides.

ACIT was designed to promote peer learning and social connectedness among participants in various ways. Much of the learning occurred naturally as participants interacted during the sessions and in conversations over lunch and other breaks. In addition, a more formal structure of peer learning was offered through “learning communities.” Each learning community, composed of four to five participants, met at the end of each day to reflect on the curricular content of the module and commit to specific ways in which they would implement new knowledge and skills in their work. By publicly committing to goals, the group held each person accountable and provided ongoing support to help meet those goals. The learning communities served as a network of support for participants, in which they could speak openly about challenges they were facing and brainstorm approaches to overcoming them.

In addition to the two-day modules, ACIT also included multidisciplinary group projects based on institutional needs identified by campus leadership, department chairs, and program participants. The complete list of submitted project ideas was narrowed down to those with the highest priority and sufficient resources to bring them to fruition in 2014. Each project was sponsored by specific institutional leaders. During the first module, participants self-selected into project teams through a facilitated process that ensured the teams were diverse and made up of participants who had an interest in the topic. Project teams consisted of four ACIT participants who collaboratively developed a project charter to establish goals, roles, and a timeline for completion. In addition, each team determined their milestones of success, held each other accountable for project progress, and provided ongoing peer mentoring and support to one another. As such, the capstone projects were seen as a venue for applying the learning from the curriculum, enhancing collaboration skills and peer mentoring, and meeting institutional needs, ideally strengthening connectivity to colleagues and the institution.

METHODS

Our mixed-methods program evaluation was performed to answer the question: How does a mid-career faculty development program in academic medicine impact faculty and institutional vitality? The evaluation focused on the following aspects of the program: (1) ACIT's ability to achieve its stated learning goals, (2) ACIT's curricular content, (3) effectiveness of pedagogies used, (4) impact of ACIT on the participants’ work, and (5) impact of ACIT on the institution. Our study was approved by our Institutional Review Board. Participants and referents provided informed consent.

Study Participant Selection

A competitive application process took place in October 2013 to select 16 faculty members (intervention group) to participate in ACIT. This inaugural group (also referred to as the “cohort”) included 13 clinical faculty members from 10 departments in the School of Medicine and three faculty members from three departments in the School of Public Health. Over 60% of the participants were women and 30% were under-represented minorities in medicine. In addition, twenty five faculty members were identified by participants’ department chairs as “equivalents” to the participants based on their rank, department/section, track, and number of years at rank (reference group).

Procedures

The intervention and reference groups were invited to complete two instruments via Qualtrics (Provo, UT) prior to and at the completion of the program. A 32-item Knowledge, Skills, and Attitudes Survey was designed to assess (1) faculty perceptions of their competence in the topic areas covered by the six ACIT modules and the skills targeted through the group projects, and (2) faculty perceptions of support by the institution. The survey was adapted from Stanford's Leadership Program Survey, which has been used through several iterations of their leadership development program. At this time, there have been no formal publications addressing the reliability and/or validity of this instrument.

A Connectivity Scale included the 25-item Sense of Community Index 2 (SCI-2), which uses perceptions of four elements to measure community (membership, influence, meeting needs, and shared emotional connections), wherein a higher total score reflects a greater sense of community. The SCI-2 has a maximum total score of 72, with each subscale having a max score of 18. Using a survey of 1800 people, analyses of the SCI-2 indicate strong reliability of both the overall instrument (coefficient alpha= .94) and the subscales (coefficient alpha scores of .79 to .86) (Chavis, Lee, & Acosta, 2008). Two additional questions taken from the 2012 Alfred P. Sloan Faculty Survey were added to provide data that could be compared to responses from the general faculty. We are not aware of any validation studies or technical data related to the 2012 Alfred P. Sloan Faculty Survey.

At the end of each module, participants were given a questionnaire designed to capture information about aspects of the module (e.g., content, pedagogy) that were effective or ineffective. In addition, the questionnaires asked about intent to apply information from the module in participants’ work and evidence of how they had applied content from past modules in their work thus far.

The quantitative data from the instruments above were triangulated with qualitative data collected from interviews and focus groups with multiple stakeholders. The first author conducted four participant focus groups, as well as in-person or phone interviews with nine department chairs and section chiefs, five ACIT staff members, and four institutional leaders.Each of the focus groups was 60 minutes, and interviews ranged in length from 10-60 minutes. The interviews and focus groups were conducted using a guide of semi-structured questions coinciding with the evaluation objectives and were audio-recorded with participant permission.

Data Analysis

Quantitative interval data from the Knowledge, Skills, and Attitudes Survey, the Connectivity Scale, and the module satisfaction questionnaires were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics with IBM SPSS Statistics 19 (Armonk, NY). In all of the analyses, only data from the participants and referents with matched pre/post surveys were included. Independent samples t-tests were performed to assess for baseline differences between ACIT and reference group participants. At the completion of the program, paired-samples t-tests were performed to assess changes within each group over the duration of the program. Independent samples t-tests were performed to assess whether there were significant differences between the changes of each group. For the two categorical questions on the Connectivity Scale that were taken from the 2012 Alfred P. Sloan Faculty Survey, chi-square tests were performed both pre- and post-intervention to compare participants to the reference group and to the general faculty, whose data had been collected previously as part of the 2012 Alfred P. Sloan Faculty Survey. Non-parametric tests (Mann Whitney tests, Wilcoxon signed ranks tests, and Fisher's exact test) were used to confirm results. A two-tailed significance level of p≤0.05 was used for all tests.

Qualitative data were gathered from the module satisfaction questionnaires, interviews, and focus groups. For each data source, the complete discourse was transcribed by the first author using QSR International's NVivo 10 qualitative data analysis software, which also was used to assist in coding for themes related to the evaluation's stated objectives. The first author manually coded all responses into a codebook of themes, and the initial data groupings were reviewed by the second author. Any disagreements were discussed until consensus was achieved. To establish inter-rater reliability, the second author coded 25% of the transcripts selected at random. Once the full data set of open-ended survey items and interview/focus group questions was coded, thematic analysis was used to generate inductive hypotheses using rich, thick narrative.

RESULTS

Pre-Intervention Results

Four items on the Knowledge, Skills, and Attitudes Survey were found to have significant differences between the participants’ and referents’ perceptions of their knowledge, skills, and attitudes prior to the ACIT program. In all cases, the reference group reported higher mean scores compared to the participants. On the Connectivity Scale, five of the statements representing how respondents felt about their community prior to the initiation of ACIT received significantly different responses. For each of these statements, the reference group expressed more agreement (i.e. a greater sense of community).

Post-Intervention Results

Comparing ACIT participants’ pre-intervention and post-intervention responses on the Knowledge, Skills, and Attitudes Survey, their mean scores increased for all 32 items, with 20 of the 32 gains being statistically significant. These gains included progress in establishing a career plan, recognizing and meeting the needs of stakeholders, understanding when, where, and how to spend resources, communicating effectively with colleagues, negotiating and resolving conflict, understanding disruptive innovation, leading in times of uncertainty, creating an innovative culture, and eliciting feedback from and providing feedback to colleagues. Conversely, the referents reported 16 gains, 10 losses, and 6 tied scores, with only 1 gain being significant. Thirteen of the gains made by participants were also statistically significant when comparing the pre/post changes in ratings between participants and referents.

Comparing ACIT participants’ pre-intervention and post-intervention responses on the Connectivity Scale, their mean scores increased for all 24 items, with 9 of the 24 gains being statistically significant. These gains included having shared values, getting needs met, trusting others, having influence, seeing good leadership, and feeling hopeful about the community. Conversely, the referents reported 17 gains, 4 losses, and 3 tied scores, with only 2 gains being significant. Two of the gains made by participants remained statistically significant when comparing the changes in ratings between participants and referents. In addition, the participants had a significant gain in their total SCI-2 scores, as well as their subscale scores for reinforcement of needs and shared emotional connections. In contrast, referents did not experience any significant gains in their total SCI-2 scores or their subscale scores. For the first question from The Alfred P. Sloan Faculty Survey (“All things considered, how satisfied are you with your faculty career at your institution?”), the overall satisfaction of ACIT participants after the ACIT program was significantly higher compared to the referents (p=.03).

Module Satisfaction Questionnaires

Using a 5-point Likert scale, with 1 = poor / very ineffective and 5 = excellent / very effective, participants rated the content and facilitation of each individual session, resulting in a session average of 4.06 for content (range = 2.71 – 5) and a session average of 4.14 for facilitation (range = 2.82 – 4.88). For the question “How helpful was the discussion in your LEARNING COMMUNITY?” the average rating among the six modules was 3.94 (range = 3.17 – 4.45). For the question “How helpful was the time spent meeting with your CAPSTONE PROJECT TEAM?” the average rating among the six modules was 3.88 (range = 3.70 – 4.35).

Qualitative Data

Sixteen primary themes emerged through coding the transcripts of the interviews, focus groups, and open-ended questions on the Module Satisfaction Questionnaires. The inter-rater reliability was found to be Kappa = 0.792 (p <.001), 95% CI (0.735, 0.849). The themes were grouped into four categories:

(1) Factors that Impact Mid-Career Faculty Vitality

Representatives from each of the evaluation constituencies commented on some defining characteristics of mid-career for themselves, their colleagues, or their faculty. One department chair noted that “the people in the middle get the short shrift,” whereas a participant stated that “mid-career is a really lonely place.” The evaluation uncovered nine factors impacting mid-career faculty vitality, both institutionally and globally, including the organizational mission and one's personal sense of purpose; available resources; opportunities to reflect, set goals, and develop; sense of community; opportunities for collaboration; guidance from mentors; work-life integration; positive reinforcement; and institutional culture. The evaluation participants were in agreement that ACIT's mere presence was viewed very positively by the faculty, especially with it occurring at a level beyond the section and department: “Just the fact that there was the process and the program is a reassuring message to the mid-career faculty at large... Isn't that a message that somebody at some level cares about the faculty and isn't that important?”

(2) ACIT's Infrastructure and Design

Evaluation participants commented on several important features of the program's infrastructure and design, including committed staff, peer mentoring and feedback, the location and length of the program, and the availability of protected time. In addition, the curriculum was viewed as comprehensive and appropriately targeted to the needs of mid-career faculty. The ACIT staff and participants reported that the core competencies accurately reflect the content that was delivered and should be at the heart of a second iteration of the program. One participant stated, “The ACIT curriculum is actually ‘the Anatomy and Physiology of Running a Thriving Organization.’” When asked specifically about content areas that could be added or enhanced, several constituencies mentioned administrative and management skills, mentoring, entrepreneurship, developing an international reputation, giving and receiving feedback, managing meetings, and financial or conflict negotiation.

The most influential aspects of the program's didactic sessions included diverse educational methods, experiential learning, immediate applicability, and accessible language. One area of frustration that was shared by many constituencies was the fact that the content wasn't always delivered in a language that was accessible to all participants. Several ACIT staff members and participants noted that some sessions were dominated by hospital jargon, which was less relevant for participants who were primarily researchers or educators.

The perceived utility of the learning communities appears to be related to the degree of connectedness among the group members and their satisfaction with the level of facilitation provided. The majority of participants expressed that their groups could have benefited from more explicit directions and structure, particularly at the beginning, while a few noted that they preferred either a balanced or less prescriptive model. ACIT staff and participants suggested other factors that could improve the effectiveness of future learning communities, such as having concrete personal development plans to keep members on task, and initiating ground rules to ensure that all members are able to speak and contribute equally.

Themes related to the capstone projects centered on the selection of project ideas and project teams, availability of time to complete the projects, level of facilitation, having realistic and relevant goals, and support from and interactions with the sponsors. A few participants suggested having everyone work on different facets of the same project or having groups select projects that are more directly related to their daily work. There was also general agreement among participants and ACIT staff that it would be beneficial to carve out more time during the modules for groups to work on their projects. Several individuals expressed that having reserved time at the end of each module would enhance the groups’ ability to implement what they had just learned into the execution of their projects. Similarly, there was basic consensus that the project teams would have benefited from having a facilitator to help set explicit goals and timelines, observe group dynamics, create transparent dialogue, and check in to ensure that the projects stay on track and are adequately supported by the sponsors. Concerns about the feasibility of the group projects were also raised, with one participant noting, “If they (the institutional leaders) couldn't solve it, then how could we?”

Although the didactic sessions, learning communities, and capstone projects were designed to unfold in a cohesive manner, the ACIT staff agreed that they would like for future programs to connect these elements in a more deliberate way. One staff member summarized this sentiment with “I finished the program feeling like there was a lot of information floating out there, but it wasn't that easy to tie it all back together. In the future, we should think more about how to strike the right balance between focusing on content and giving people a chance to reflect on what is happening in their lives.”

(3) Impact of ACIT on Faculty Vitality

There is tremendous evidence suggesting that the prevailing strength of the program was its ability to create a cohesive cohort. Several institutional leaders and department chairs commented on observing the high level of camaraderie that the group developed. The participants expressed appreciation for simply knowing that there are other people out there at the same place in their careers who are feeling the same way and are eager to collaborate. A participant commented on how these relationships are already reaping tangible dividends: “For me, ACIT is a group of real potential resources. Just yesterday I had a problem arise, and now I have a go-to person who I know exclusively from ACIT who can help me solve it.” There also appeared to be general consensus that the participants had ample opportunities to self-reflect and assess their strengths and areas for growth. One participant noted, “I would say that not a day goes by when I don't think about some aspect of ACIT. I'm reflecting on a day-to-day basis, rather than just once a year when I'm on vacation. That alone is a testament to what I've gotten out of the program.”

Multiple stakeholders indicated that the most ambitious aim of the program was to enhance participants’ ability to implement transformative work. However, several participants and department chairs commented on concrete ways that they can already see ACIT's impact on gains in knowledge and confidence regarding the core competencies of the program. Several participants reported feeling more energized, positive, empowered, and focused as a result of their participation in ACIT: “From the time I applied to the present, there is no doubt that I am more enthusiastic and have restored optimism, and I bet that permeates my work.”

Participants also commented on global improvement of their leadership skills and their ability to articulate a vision. Several indicated that their increased confidence has encouraged them to pursue new leadership opportunities, to move forward in areas where they had previously been indecisive, and to help their colleagues understand changes occurring at the institution by providing context. One of the participants stated, “Most of all, ACIT fueled my desire to make transformative contributions, invest in people and solutions that result in returns that benefit the organization, it's members, and the populations it serves... A culture where everyone wins!” However, these gains cannot be taken for granted and will need to be consistently reinforced (Daley et al., 2008). In the words of a participant, “Who is going to help me stay on track, make sure that I don't lose that momentum now that I've had some clarity over the last ten months about what is possible for me to accomplish?”

(4) Impact of ACIT on Institutional Vitality

Representatives from all constituencies noted that one of ACIT's primary strengths was identifying, nurturing, and retaining potential leaders from diverse backgrounds. The fact that over 60% of the participants were women and 30% were under-represented minorities enabled the program to leverage the strengths of specific individuals whose influence over the faculty at large may help the institution accomplish its strategic goal of recruiting and retaining a more diverse faculty.

At the conclusion of the program, many participants stated that they are more likely to stay because the institution invested in their development, with one noting, “For me, this program has taken me from a fairly discouraged mid-career faculty member who was seriously considering leaving the institution, to a newly energized leader with many new and valuable contacts and a thirst for being involved in medical campus leadership at a more significant level.” There was also a general consensus that having a core group of faculty who become more fulfilled, content, and productive will lead to stronger departments, better mentors, and more satisfied students, residents, and patients. As such, department chairs were unanimously supportive of continuing programs like ACIT, which was poignantly summarized by one chair who said, “This type of faculty development is a need that just can't be saturated.” Several interviewees also stated that custom-made programs like ACIT have much more potential to generate cohort and institutional connections than external programs and should be looked at as long-term investments. Various chairs and ACIT staff members referred to the ACIT participants as “treasures” and emphasized the importance of giving them time to put their new skills and knowledge to use.

DISCUSSION

Participants vs. Referents

The pre-intervention comparisons indicate that the ACIT participants and referents were fairly well matched; however, there were a few notable differences. First, the only pre-intervention differences pointed to the referents having higher levels of self-confidence in certain abilities (e.g. identifying their strengths and weaknesses, negotiating and resolving conflict, and understanding the impact of disruptive innovation) and a greater sense of community. This finding may suggest that the participants were particularly skilled at recognizing their own deficits and their need for faculty development, thus making them ideal candidates for the ACIT program. Furthermore, vital faculty members are generally organized and open-minded in their intentional pursuit of new challenges to address and new collaborations to form and have been shown to “grow personally and professionally throughout the academic career, continually pursuing expanded interests and acquiring new skills and knowledge” (Baldwin, 1990). Therefore, it appears that the inaugural cohort was well-suited for the ACIT program.

Program Outcomes

The post-intervention results indicate that there were indisputable gains made by the participants over the course of the program. Since the referents did not experience the same significant changes, we can infer that the program deserves at least partial credit for these gains. Another noteworthy post-intervention finding is that the participants’ ended the program with a significantly increased total sense of community and overall satisfaction with their academic careers, whereas no change was noted for the referents. This finding is meaningful due to the associations between connectivity, satisfaction, and vitality, the latter of which has been positively correlated with faculty retention (Baldwin, 1990).

The high ratings on the module satisfaction questionnaires and the supporting feedback from the focus groups suggest that ACIT's content was pertinent, well-received, and effective. The program was undoubtedly successful at generating a powerful cohort effect and enabling participants to self-reflect and think deeply about their career goals. Although it is premature to gauge ACIT's full impact on collaboration and transformation, it can be said with confidence that some of the institution's most capable faculty have an enhanced level of leadership skills, including emotional intelligence and institutional savvy.

The merit of ACIT can also be judged by comparing it to literature on effective faculty development programs. For example, work by Baldwin and Chang (2006) indicated that a comprehensive mid-career program should focus on three primary goals (career reflection and assessment, career planning, and career action / implementation) that are grounded in collegial support (e.g. mentoring, networking, and collaborating), resources (e.g. information, time, funding, and space), and reinforcement (e.g. recognition and rewards). Similarly, McLean Cilliers, and Van Wyk (2008) attributed the success of their faculty development program in academic medicine to their emphasis on experiential learning, multidisciplinary projects, and reflection activities. When considering these criteria, it is evident that ACIT's design was well-informed and based on best practices. Therefore, the inclusion of experiential learning, multidisciplinary projects, and reflection enhances the validity of the positive outcomes noted above. For a summary of general recommendations, please see Table 6.

Table 6.

General Recommendations

|

Based on the findings of this analysis, we provide a few recommendations for future iterations of ACIT that may be applied to other mid-career faculty development programs: |

| The protected time was critical for some participants, but not for others. Recommendation: |

| • Redesign the program for 20-25 faculty with enough scholarship funding to provide up to 5% of protected time, while continuing to provide the menu of less-intensive development opportunities currently utilized by the remaining faculty each year. |

| The primary staff members were ideally suited for their roles, as they set high expectations for the program and the participants (Mclean et al., 2008). Their commitment and finesse planted the seeds for connectivity and buy-in among all parties. Recommendation: |

| • The program organizers should be carefully selected and supported. |

| The off-site location and two-day sessions were essential to maximize participant engagement. Recommendation: |

| • Keep the program off-site and maintain consecutive two-day modules. |

| Although there were suggestions for additional topic areas that could be added, there was greater support for curtailing the content to allow more time for processing and application. Recommendations: |

| • Retain the content areas that received the highest ratings and integrate those speakers into the core faculty to create more continuity. |

| • Ensure that core faculty are committed to |

| ○ Using interactive activities that will focus on experiential learning and allow for movement throughout the day and |

| ○ Making the language and material relevant to participants from all schools and backgrounds. If necessary, incorporate break-out sessions to allow sub-groups to work together (e.g. clinicians, administrators, researchers, and teachers). |

| • Reserve time at the beginning and end of each module to discuss the participants’ practical applications of the material (Carroll, 1993) |

| The capstone projects were ambitious, difficult to coordinate, and not well supported by all sponsors. Recommendations: |

| • Either |

| 1. Chose one project with a committed sponsor and let individuals or groups tackle different aspects of the project |

| 2. Let participants chose a project where they can apply the content to their pre -existing work and responsibilities. |

| • Build the group-work time into the program. |

| • Employ facilitators to assist in successfully launching the project(s) and helping groups stay on track. |

| • Require regular meetings with the sponsor(s) during and at the completion of the program. |

| • Conclude with a formal agreement between group members and sponsor(s) about the “next steps” for the project. |

| • Given the importance of institutional culture to the success of faculty development initiatives (Laursen & Rocque, 2009), a true partnership between the participants and leaders would set a valuable precedent for future cohorts. |

| The learning communities’ camaraderie was appreciated by all, but their utility and effectiveness were mixed. Recommendations: |

| • Keep the learning communities, but have group members set ground rules and expectations at the beginning and schedule regular check-ins with facilitators. |

| • Ensure that participants’ career goals are congruent with their values (Banks, 2012), and then use their personal development plans to provide structure and accountability to the learning communities. |

| • Consider having members of the original cohort return to speak with the next cohort about how to maximize the effectiveness of the groups. |

| The longitudinal design was key to creating the cohort effect and increasing connectivity to the institution. However, the program lacked the robust level of cohesion that was desired. Recommendation: |

| • Maintain the longitudinal design, but be more intentional about interlacing the content and bridging the modules in order to connect the various components (Garet, Porter, Desimone, Birman, & Yoon, 2001). |

| ACIT's long-term impact on the participants and the institution would be enhanced by a self-sustaining peer mentoring system, which has also been shown to improve recruitment efforts and increase retention (Heinrich & Oberleitner, 2012). Recommendations: |

| • Formally integrate mentor training and peer coaching into the program or provide supplemental training to interested participants. |

| • Provide feedback to department chairs so that the strengths of their participating faculty members can be utilized most effectively by mentoring colleagues and serving as liaisons to the institutional leaders. |

Limitations

The results of this study are limited by the relatively small size of the data sets based on the number of completed surveys. We can only theorize that the timing of the post-intervention instruments (during the December holidays and at the end of an academic semester) may be responsible for the drop off in participation from both participants and referents. However, the validity of the results was enhanced by using both parametric and non-parametric tests and only labeling results as statistically significant if they had p-values ≤ .05 in both analyses.

Participation in ACIT was not randomized, and there may be a selection bias inherent in a competitive application process. We used referents nominated by department chairs as a comparison group but acknowledge that individuals who were selected as referents may not have been well matched. It was unanticipated that the referents had higher self-reported skills and connectivity than the participants.

Using self-reported data from a modest size cohort being evaluated with multiple instruments has the potential to inflate positive outcomes of the program, and the level of statistical significance did not account for multiple testing. In order to mitigate this risk, we attempted to corroborate or dispute the data through the focus groups and interviews with department chairs, institutional leadership, and ACIT staff.

Another threat to our study's validity was researcher bias due to the affiliation of the primary evaluator with the program's institution. However, she maintained an audit trail of all the pertinent details of the evaluation process to illustrate how the design and hypotheses emerged and how her experiences and preferences may have contributed to that progression. In addition, her formal role at the institution is in no way associated with or influenced by the staff or success of ACIT, thus minimizing any potential risk of intimidation or indebtedness and maximizing the likelihood of the evaluation's results being analyzed and reported in a balanced format.

Lastly, the results are bound to the setting and context of the study, and thus the conclusions may not be generalizable to other institutions. However, given the common themes surrounding the needs and experiences of mid-career faculty across schools and disciplines, the recommendations may be of value to other institutions that are interested in creating development opportunities specifically for their mid-career faculty.

Future Directions of the Program

ACIT undoubtedly made a positive impact on the inaugural cohort, but there are clearly many other faculty who are also in need of development. This invites the question of whether there are additional areas of faculty development that should be addressed in order to better meet institutional needs. There was general agreement that no single program will meet the needs of all faculty; therefore, a successful institution will provide a menu of opportunities. In turn, several department chairs suggested having ACIT reserved for those with the most evident leadership potential, while developing a broader curriculum for the remaining mid-career faculty. Representing another perspective, an ACIT staff member stated that, “A similar program could focus on the most vulnerable groups of faculty, such as women and under-represented minorities. I think that could be incredibly impactful on one of the institution's strategic goals, which is to increase diversity.”

Future Directions of the Evaluation

Student learning and aptitude have only rarely been examined as a part of faculty development program evaluations, while evaluations of participating faculty from peers, patients, or direct reports seem to be missing entirely (Steinert et al., 2006). Therefore, baseline data have been collected via patient satisfaction surveys and student/resident evaluations to provide the basis for a more robust longitudinal assessment. Future evaluations could also be strengthened by including interviews or focus groups with all stakeholders one or two years after the program is completed. The Knowledge, Skills, and Attitudes Survey and the Connectivity Scale could be re-administered at that time as well. In addition, the ACIT alumni and reference groups could be compared according to the number of new collaborations (measured through grants and papers) and the number of new institutional leaders (with special attention paid to women and under-represented minorities). These data sets would provide evidence for or against any lasting effects related to the gains in faculty and institutional vitality that may have resulted from ACIT.

CONCLUSION

While much has been done to address junior and senior faculty needs, mid-career faculty members have only recently been recognized as warranting and requiring unique support (Baldwin & Chang, 2006; Dyrbye et al., 2013). Given the growing economic uncertainty of medical school funding and the evolution of tenure policies, academic medicine is a particularly vulnerable backdrop for this group (Zwack & Schweitzer, 2013). In this new era, medical schools must realize the importance of investing in mid-career faculty in order to improve the long term success and stability of their institution. However, in order for a faculty development program to be sustainable, it must produce measurable outcomes that are beneficial to the individual faculty members, as well as their colleagues, patients, and students. In order to attain this ambitious goal, such programs must positively impact both faculty and institutional vitality by enhancing the level of engagement and collaboration. Kalb and O'Conner-Von stated, “Academic structures that effectively facilitate team-based learning in interprofessional education need to be determined, implemented, and then evaluated” (Kalb & O'Conner-Von, 2012). Therefore, our mixed methods evaluation tells the story of how one medical campus incorporated mid-career faculty development into academic medicine. Given that this specific subset of higher education faculty has been rarely studied, we hope to provide a useful perspective to guide other faculty development offices in similar initiatives.

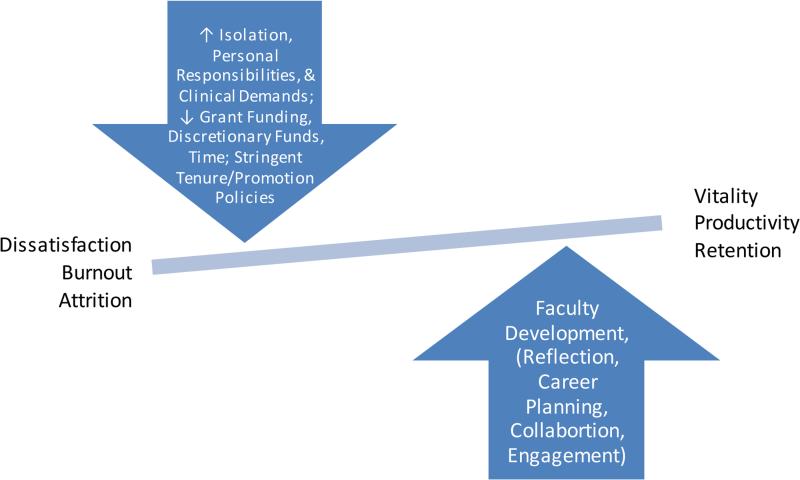

Figure 1.

Factors Influencing Mid-Career Faculty Vitality

Table 1.

Curricular Content

| Module 1: Envisioning Your Role in Tomorrow's Health Care (Feb 27-28) | |

| DAY 1 | Defining the Strategic Agenda |

| Challenges and Opportunities in Health Sciences | |

| Defining Your Personal Roadmap | |

| Career Development Planning | |

| DAY 2 | Capstone Project Introduction |

| Capstone Project Planning & Management | |

| Module 2: Meeting the Needs of Stakeholders (April 3-4) | |

| DAY 1 | Stakeholder Engagement: Who, Why, and How |

| Meeting the Needs of Stakeholders | |

| The Value Proposition | |

| DAY 2 | Transformative and Transactional Leadership |

| The Financial Perspective | |

| Strategic Planning | |

| Module 3: Working Across Boundaries: Teamwork, Communication & Leadership (May 29-30) | |

| DAY 1 | Communicating Effectively |

| The Entrepreneurial Mindset | |

| Building Collaborative Teams | |

| DAY 2 | Mentoring Networks |

| Strategic Partnerships & Alliances | |

| Negotiation & Conflict Resolution | |

| Difficult Conversations | |

| Module 4: Working Efficiently and Effectively (June 26-27) | |

| DAY 1 | Managing Process |

| Managing Projects | |

| DAY 2 | The Costs of Poor Quality |

| Working Efficiently and Effectively | |

| Module 5: Creating New Value (September 18-19) | |

| DAY 1 | Creating New Capabilities |

| Organizational Savvy | |

| DAY 2 | Leveraging Diversity & Inclusion |

| Disruptive Innovation | |

| Module 6: Envisioning the Future – And Getting to It (November 20-21) | |

| DAY 1 | Change Leadership |

| Managing Under Uncertainty | |

| Project Presentations | |

| DAY 2 | Creating Cultures of Innovation |

| Continuing on the Transformative Journey | |

Table 2.

Number of Completed Pre-/Post-Intervention Surveys

| Instrument | Period administered | Participants | Referents |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge, Skills, and Attitudes Survey | Pre-intervention | 16 | 20 |

| Post-intervention | 11 | 15 | |

| pre/post surveys with matching IDs | 9 | 11 | |

| Connectivity Scale | Pre-intervention | 16 | 19 |

| Post-intervention | 12 | 15 | |

| Pre/post surveys with matching IDs | 10 | 12 | |

Table 3.

Knowledge, Skills, and Attitudes Survey – Pre/Post Changes

| Participants | Referents | Change Difference | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item (Level of Ability) | PRE Mean | POST Mean | Mean change (SD) | P-value | PRE Mean | POST Mean | Mean change (SD) | P-value | P-value |

| 1.1: Identify my own strengths and weaknesses | 3.78 | 4.00 | 0.22 (0.44) | .17 | 4.18 | 4.18 | 0.00 (0.44) | 1.00 | .28 |

| 1.2: Establish a development plan for my career | 3.00 | 4.00 | 1.00 (0.71) | .003 | 3.27 | 3.27 | 0.00 (0.77) | 1.00 | .008 |

| 1.3: Recognize who our stakeholders are and how to meet their needs | 2.67 | 3.89 | 1.22 (1.39) | .03 | 3.27 | 3.18 | −0.09 (1.04) | .78 | .03 |

| 1.4: Improve both quality and efficiency | 3.11 | 4.11 | 1.00 (1.00) | .02 | 3.45 | 3.55 | 0.09 (0.83) | .72 | .05 |

| 1.5: Be a leader who is visionary and transformative | 2.44 | 3.78 | 1.33 (1.00) | .004 | 2.64 | 3.09 | 0.45 (1.13) | .21 | .08 |

| 1.6: Be a leader who is able to fulfill daily obligations and tasks | 4.00 | 4.56 | 0.56 (0.53) | .01 | 3.91 | 4.00 | 0.09 (1.04) | .78 | .22 |

| 1.7: Understand where, when, and why we spend resources | 2.22 | 3.89 | 1.67 (1.22) | .004 | 3.18 | 3.73 | 0.54 (0.82) | .05 | .04 |

| 1.8: Communicate effectively with colleagues | 3.56 | 4.44 | 0.89 (0.93) | .02 | 4.18 | 4.09 | −0.09 (0.70) | .68 | .02 |

| 1.9: Communicate effectively with the media | 2.78 | 3.44 | 0.67 (1.00) | .08 | 2.73 | 2.73 | 0.00 (0.89) | 1.00 | .14 |

| 1.10: Pitch a project to potential funders or supporters | 2.78 | 3.89 | 1.11 (0.78) | .003 | 2.91 | 3.36 | 0.45 (0.69) | .05 | .07 |

| 1.11: Build and manage collaborative teams | 3.33 | 4.00 | 0.67 (0.87) | .05 | 3.36 | 3.73 | 0.36 (0.81) | .17 | .43 |

| 1.12: Establish strategic partnerships and alliances | 3.00 | 4.00 | 1.00 (0.87) | .009 | 2.91 | 3.45 | 0.54 (0.93) | .08 | .28 |

| 1.13: Negotiate and resolve conflict effectively | 2.78 | 4.00 | 1.22 (1.30) | .02 | 3.73 | 3.82 | 0.09 (0.70) | .68 | .04 |

| 1.14: Manage process and projects effectively and efficiently | 3.78 | 4.33 | 0.56 (0.88) | .10 | 3.64 | 3.64 | 0.00 (1.00) | 1.00 | .20 |

| 1.15: Continue to learn and grow on an ongoing basis throughout my career | 3.67 | 4.44 | 0.78 (1.30) | .11 | 4.18 | 4.00 | −0.18 (0.75) | .44 | .07 |

| 1.16: Consider trade-offs of investing in different areas | 3.22 | 4.11 | 0.89 (1.45) | .10 | 3.27 | 3.55 | 0.27 (0.79) | .28 | .28 |

| 1.17: Recognize and manage my innate and implicit biases | 3.22 | 4.11 | 0.89 (1.27) | .06 | 3.73 | 3.64 | −0.09 (1.22) | .81 | .10 |

| 1.18: Effectively and respectfully engage diverse groups of colleagues, trainees, and patients | 3.67 | 4.22 | 0.56 (0.88) | .10 | 4.18 | 4.00 | −0.18 (0.87) | .51 | .08 |

| 1.19: Understand what disruptive innovation is and how it impacts our lives | 1.17 | 3.56 | 1.89 (0.93) | <.001 | 2.73 | 2.73 | 0.00 (0.89) | 1.00 | <.001 |

| 1.20: Lead in times of change and uncertainty | 2.33 | 3.89 | 1.56 (0.73) | <.001 | 2.82 | 3.27 | 0.45 (0.93) | .14 | .008 |

| 1.21: Create cultures that nurture innovation | 2.67 | 4.00 | 1.33 (0.87) | .002 | 2.91 | 3.36 | 0.45 (0.82) | .10 | .03 |

| Item (Agreement with Statement) | PRE Mean | POST Mean | Mean change (SD) | P-value | PRE Mean | POST Mean | Mean change (SD) | P-value | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.1: This institution cares about me | 2.11 | 3.44 | 1.33 (1.12) | .007 | 2.27 | 2.45 | 0.18 (0.75) | .44 | .02 |

| 2.2: I am receiving guidance and/or support for my progress/performance | 2.22 | 3.22 | 1.00 (0.87) | .009 | 2.55 | 2.73 | 0.18 (0.60) | .34 | .03 |

| 2.3: This institution is a place where careers can develop | 2.44 | 3.11 | 0.67 (1.32) | .17 | 2.91 | 2.82 | −0.09 (0.70) | .68 | .15 |

| 2.4: I am connected to and supported by my colleagues at work | 2.78 | 3.22 | 0.44 (0.88) | .17 | 3.18 | 3.09 | −0.09 (0.70) | .68 | .16 |

| Item (Behaviors in the Workplace) | PRE Mean | POST Mean | Mean change (SD) | P-value | PRE Mean | POST Mean | Mean change (SD) | P-value | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.1: Work toward a solution rather than just identifying a problem | 3.78 | 4.33 | 0.56 (0.53) | .01 | 3.82 | 4.36 | 0.54 (0.52) | .006 | .97 |

| 3.2: Pull a team together when you see a problem | 3.33 | 3.56 | 0.22 (0.97) | .51 | 3.73 | 3.27 | −0.45 (0.69) | .05 | .10 |

| 3.3: Initiate action when you see a problem | 3.67 | 4.00 | 0.33 (1.00) | .35 | 4.09 | 4.09 | 0.00 (.045) | 1.00 | .38 |

| 3.4: Ensure ongoing self-awareness through reflection | 3.44 | 4.22 | 0.78 (0.83) | .02 | 4.00 | 4.09 | 0.09 (1.04) | .78 | .12 |

| 3.5: Ensure ongoing self-awareness by eliciting feedback from colleagues | 2.67 | 3.33 | 0.67 (0.87) | .05 | 3.45 | 3.00 | −0.45 (0.69) | .05 | .006 |

| 3.6: Take responsibility to provide constructive feedback to colleagues with whom you are working, without being asked. | 2.78 | 3.89 | 1.11 (1.17) | .02 | 3.45 | 3.27 | −0.18 (0.60) | .34 | .01 |

| 3.7: Fully engage with team members and dedicate the time/effort needed (when you are a member of a team) | 4.22 | 4.33 | 0.11 (0.60) | .59 | 4.18 | 4.27 | 0.09 (0.54) | .59 | .94 |

The items above were scored on a 5-point Likert scale from 1-5, with 1 = novice and 5 = expert for level of ability in Section 1, 1 = strongly agree and 5 = strongly disagree for agreement with statements in Section 2, and 1 = never and 5 = always for behaviors in Section 3. Light blue shading = items with statistically significant differences.

Table 4.

Connectivity Scale – Pre/Post Changes

| Participants | Referents | Change Difference | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statement | PRE Mean | POST Mean | Mean change (SD) | P-value | PRE Mean | POST Mean | Mean change (SD) | P-value | P-value |

| 2.1: I get important needs of mine met because I am part of this community. | 1.30 | 2.10 | 0.80 (0.63) | .003 | 1.92 | 1.92 | 0.00 (0.60) | 1.00 | .007 |

| 2.2: Community members and I value the same things. | 1.30 | 1.90 | 0.60 (0.52) | .005 | 2.00 | 2.17 | 0.17 (0.72) | .44 | .12 |

| 2.3: This community has been successful in getting the needs of its members met. | 0.70 | 1.50 | 0.80 (0.79) | .01 | 1.17 | 1.58 | 0.42 (0.51) | .017 | .21 |

| 2.4: Being a member of this community makes me feel good. | 1.60 | 2.30 | 0.70 (0.67) | .01 | 2.08 | 2.42 | 0.33 (0.65) | .10 | .21 |

| 2.5: When I have a problem, I can talk about it with members of this community. | 1.70 | 2.20 | 0.50 (0.85) | .10 | 2.17 | 2.25 | 0.08 (0.79) | .72 | .25 |

| 2.6: People in this community have similar needs, priorities, and goals. | 1.80 | 2.00 | 0.20 (0.92) | .51 | 1.75 | 2.00 | 0.25 (1.06) | .43 | .91 |

| 2.7: I can trust people in this community. | 1.60 | 2.20 | 0.60 (0.52) | .005 | 2.08 | 2.17 | 0.08 (0.51) | .59 | .03 |

| 2.8: I can recognize most of the members of this community. | 1.70 | 1.80 | 0.10 (0.74) | .68 | 1.83 | 1.83 | 0.00 (0.85) | 1.00 | .77 |

| 2.9: Most community members know me. | 1.50 | 1.70 | 0.20 (1.40) | .66 | 1.67 | 1.92 | 0.25 (0.75) | .28 | .92 |

| 2.10: This community has symbols and expressions of membership such as clothes, signs, art, architecture, logos, landmarks, and flags that people can recognize. | 1.00 | 1.20 | 0.20 (1.03) | .56 | 1.50 | 1.42 | −0.08 (1.24) | .82 | .57 |

| 2.11: I put a lot of time and effort into being part of this community. | 1.80 | 2.10 | 0.30 (1.06) | .39 | 2.17 | 2.17 | 0.00 (0.85) | 1.00 | .48 |

| 2.12: Being a member of this community is a part of my identity. | 2.00 | 2.10 | 0.10 (0.99) | .76 | 2.25 | 2.58 | 0.33 (0.89) | .22 | .57 |

| 2.13: Fitting into this community is important to me. | 1.90 | 2.20 | 0.30 (0.95) | .34 | 2.25 | 2.50 | 0.25 (0.62) | .19 | .89 |

| 2.14: This community can influence other communities. | 1.90 | 2.20 | 0.30 (0.95) | .34 | 2.08 | 2.00 | −0.08 (0.90) | .75 | .35 |

| 2.15: I care about what other community members think of me. | 2.20 | 2.50 | 0.30 (0.82) | .28 | 2.50 | 2.42 | −0.08 (0.51) | .59 | .22 |

| 2.16: I have influence over what this community is like. | 0.90 | 1.60 | 0.70 (0.82) | .03 | 1.25 | 1.75 | 0.50 (0.67) | .026 | .55 |

| 2.17: If there is a problem in this community, members can get it solved. | 0.80 | 1.60 | 0.80 (1.03) | .04 | 1.33 | 1.50 | 0.17 (0.83) | .50 | .14 |

| 2.18: This community has good leaders. | 1.20 | 2.00 | 0.80 (0.79) | .011 | 1.58 | 1.92 | 0.33 (0.78) | .17 | .18 |

| 2.19: It is very important to me to be a part of this community. | 1.80 | 2.30 | 0.50 (0.85) | .10 | 2.00 | 2.25 | 0.25 (0.87) | .34 | .50 |

| 2.20: I am with other community members a lot and enjoy being with them. | 1.80 | 2.10 | 0.30 (0.67) | .19 | 1.92 | 2.08 | 0.17 (0.72) | .44 | .66 |

| 2.21: I expect to be a part of this community for a long time. | 2.00 | 2.10 | 0.10 (0.57) | .59 | 1.92 | 2.33 | 0.42 (0.67) | .05 | .24 |

| 2.22: Members of this community have shared important events together, such as holidays, celebrations, or disasters. | 1.40 | 1.80 | 0.40 (0.97) | .22 | 2.00 | 1.92 | −0.08 (1.00) | .78 | .26 |

| 2.23: I feel hopeful about this community. | 1.50 | 2.20 | 0.70 (0.48) | .001 | 2.08 | 2.17 | 0.08 (0.90) | .75 | .06 |

| 2.24: Members of this community care about each other. | 1.90 | 2.20 | 0.30 (0.48) | .08 | 2.25 | 2.33 | 0.08 (0.69) | .67 | .39 |

| Additional Question | PRE Mean | POST Mean | Mean change (SD) | P-value | PRE Mean | POST Mean | Mean change (SD) | P-value | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How important is it to you to feel a sense of community with other community members?” | 5.70 | 6.30 | 0.60 (0.97) | .08 | 5.75 | 6.33 | 0.58 (1.51) | .21 | .98 |

| Totals | PRE Mean | POST Mean | Mean change (SD) | P-value | PRE Mean | POST Mean | Mean change (SD) | P-value | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subscale 1: reinforcement of needs | 8.40 | 12.00 | 3.60 (3.10) | .005 | 11.08 | 12.33 | 1.25 (2.56) | .12 | .07 |

| Subscale 2: membership | 9.60 | 11.10 | 1.50 (4.43) | .31 | 11.50 | 12.08 | 0.58 (3.32) | .56 | .60 |

| Subscale 3: influence | 8.90 | 12.10 | 3.20 (4.57) | .05 | 11.00 | 12.08 | 1.08 (2.78) | .20 | .22 |

| Subscale 4: shared emotional connections | 10.40 | 12.70 | 2.30 (3.06) | .04 | 12.17 | 13.08 | 0.92 (3.18) | .34 | .31 |

| Total SCI-2 score | 37.30 | 47.90 | 10.6 (13.7) | .04 | 45.75 | 49.58 | 3.83 (9.40) | .18 | .20 |

The items above were scored on a 4-point Likert scale from 0-3, with 0 = not at all, 1 = somewhat, 2 = mostly, and 3 = completely. Light blue shading = items with statistically significant differences.

Table 5.

Career Satisfaction at the Institution

| PRE-Intervention | N (%) of Participants | N (%) of Referents |

|---|---|---|

| Very dissatisfied | 0 | 0 |

| Dissatisfied | 2 (20%) | 0 |

| Neutral | 2 (20%) | 2 (16.7%) |

| Satisfied | 5 (50%) | 8 (66.7%) |

| Very Satisfied | 1 (10%) | 2 (16.7%) |

| POST-Intervention | N (%) of Participants | N (%) of Referents |

|---|---|---|

| Very dissatisfied | 0 | 0 |

| Dissatisfied | 0 | 0 |

| Neutral | 1 (10%) | 0 |

| Satisfied | 4 (40%) | 11 (91.7%) |

| Very Satisfied | 5 (50%) | 1 (8.3%) |

Acknowledgments

This program and evaluation were funded by 1R01HL128914, 2R01HL092577, 1P50HL120163, and the American Council on Education/Alfred P. Sloan Foundation Awards for Faculty Career Flexibility.

Contributor Information

MaryAnn W. Campion, a doctorate in educational leadership and policy. At the time of this study, she was an Assistant Dean for Graduate Medical Sciences at Boston University School of Medicine and the primary evaluator for this project. She is now a Clinical Associate Professor at Stanford University. mcampion@stanford.edu

Robina M. Bhasin, the Director of Faculty Development for the Boston University Medical Campus. She was the secondary evaluator for this study. rbhasin@bu.edu

Dr. Donald J. Beaudette, an Associate Professor of the Practice at Boston University Schools of Education. He has extensive experience in faculty development at the K-12 level. djb@bu.edu

Dr. Mary H. Shann, a Professor of Education at Boston University Schools of Education. She specializes in educational assessment, research, program development, and evaluation. shann@bu.edu

Dr. Emelia J. Benjamin, the Assistant Provost for Faculty Development for the Boston University Medical Campus and a Professor of Medicine and Epidemiology at Boston University Schools of Medicine and Public Health. emelia@bu.edu

References

- Baker D. Peripatetic music teachers approaching mid-career: A cause for concern? British Journal of Music Education. 2005;22(2):141–153. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin R. Faculty vitality beyond the research university: Extending a contextual concept. The Journal of Higher Education. 1990:160–180. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin R, Chang DA. Reinforcing our “keystone” faculty: Strategies to support faculty in the middle years of academic life. Liberal Education. 2006;92(4):28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin R, DeZure D, Shaw A, Moretto K. Mapping the terrain of mid-career faculty at a research university: Implications for faculty and academic leaders. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning. 2008;40(5):46–55. [Google Scholar]

- Banks J. Development of scholarly trajectories that reflect core values and priorities: A strategy for promoting faculty retention. Journal of Professional Nursing. 2012;28(6):351–359. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canale AM, Herdklotz C, Wild L. Mid-career faculty support: The middle years of the academic profession. Faculty Career Development Services, the Wallace Center, Rochester Institute of Technology; Rochester, NY: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll RG. Implications of adult education theories for medical school faculty development programmes. Medical Teacher. 1993;15(2-3):163–170. doi: 10.3109/01421599309006709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavis D, Lee K, Acosta J. The sense of community (SCI) revised: The reliability and validity of the SCI-2.. Paper presented at the 2nd International Community Psychology Conference; Lisboa, Portugal. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cropsey KL, Masho SW, Shiang R, Sikka V, Kornstein SG, Hampton CL. Why do faculty leave? Reasons for attrition of women and minority faculty from a medical school: Four-year results. Journal of Women's Health. 2008;17(7):1111–1118. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley SP, Palermo A, Nivet M, Soto-greene ML, Taylor VS, Butts GC, Kondwani K. Diversity in academic medicine no. 6 successful programs in minority faculty development: Ingredients of success. Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine: A Journal of Translational and Personalized Medicine. 2008;75:533–551. doi: 10.1002/msj.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyrbye LN, Varkey P, Boone SL, Satele DV, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. Physician satisfaction and burnout at different career stages. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2013;88(12):1358–1367. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garet MS, Porter AC, Desimone L, Birman BF, Yoon KS. What makes professional development effective? Results from a national sample of teachers. American Educational Research Journal. 2001;38(4):915–945. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich KT, Oberleitner MG. How a faculty group's peer mentoring of each other's scholarship can enhance retention and recruitment. Journal of Professional Nursing. 2012;28(1):5–12. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalb KA, O'Conner-Von S. Breaking down silos, building up teams. Health Progress. 2012;93:38–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laursen S, Rocque B. Faculty development for institutional change: Lessons from an advance project. Change. 2009;41(2):18–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lowenstein SR, Fernandez G, Crane LA. Medical school faculty discontent: Prevalence and predictors of intent to leave academic careers. BMC Medical Education. 2007;7(1):37–37. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-7-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mclean M, Cilliers F, Van Wyk JM. Faculty development: Yesterday, today and tomorrow. Medical Teacher. 2008;30(6):555. doi: 10.1080/01421590802109834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NVivo qualitative data analysis Software. Version 10 QSR International Pty Ltd; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Peckham C. Physician burnout: It just keeps getting worse. 2015 Retrieved from http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/838437.

- Romano JL, Hoesing R, O'Donovan K, Weinsheimer J. Faculty at mid-career: A program to enhance teaching and learning. Innovative Higher Education. 2004;29(1):21–48. [Google Scholar]

- Schloss EP, Flanagan DM, Culler CL, Wright AL. Some hidden costs of faculty turnover in clinical departments in one academic medical center. Academic Medicine : Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2009;84(1):32–36. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181906dff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanafelt TD. Enhancing meaning in work: A prescription for preventing physician burnout and promoting patient-centered care. JAMA. 2009;302(12):1338–1340. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinert Y, Mann K, Centeno A, Dolmans D, Spencer J, Gelula M, Prideaux D. A systematic review of faculty development initiatives designed to improve teaching effectiveness in medical education: BEME guide no. 8. Medical Teacher. 2006;28(6):497–526. doi: 10.1080/01421590600902976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus SE, Soobiah C, Levinson W. The impact of leadership training programs on physicians in academic medical centers: A systematic review. Academic Medicine : Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2013;88(5):710–723. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31828af493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwack J, Schweitzer J. If every fifth physician is affected by burnout, what about the other four? Resilience strategies of experienced physicians. Academic Medicine : Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2013;88(3):382–389. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318281696b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]