Abstract

Consumption of navy beans (NB) and rice bran (RB) have been shown to inhibit colon carcinogenesis. Given the overall poor diet quality in colorectal cancer (CRC) survivors and low reported intake of whole grains and legumes, practical strategies to increase consumption merit attention. This study determined feasibility of increasing NB or RB intake in CRC survivors to increase dietary fiber and examined serum inflammatory biomarkers and telomere lengths. Twenty-nine participants completed a randomized-controlled trial with foods that included cooked NB powder (35g/day), heat-stabilized RB (30g/day), or no additional ingredient. Fasting blood, food logs, and gastrointestinal health questionnaires were collected. The amount of NB or RB consumed equated to 4–9% of participants daily caloric intake and no major gastrointestinal issues were reported with increased consumption. Dietary fiber amounts increased in NB and RB groups at weeks 2 and 4 compared to baseline and to control (p≤0.01). Telomere length correlated with age and HDL-cholesterol at baseline, and with improved serum amyloid A (SAA) levels at week 4 (p≤0.05). This study concludes feasibility of increased dietary NB and RB consumption to levels associated with CRC chemoprevention and warrants longer-term investigations with both foods in high-risk populations that include cancer prevention and control outcomes.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer in the United States, with an estimated 132,700 new cases in 2015 [1, 2]. Decades of research indicate that lifestyle factors, including poor diet and physical inactivity, can contribute to a higher risk of CRC [3]. Current dietary recommendations to prevent CRC include eating a variety of vegetables, fruits, whole grains, and beans, while limiting consumption of processed foods, and eating less red and processed meat [4]. Recent studies demonstrate that diets high in fiber can be preventive against CRC, as every 10 grams of fiber consumed daily reduces risk by 10% [3–5].

People who regularly eat beans and whole grains are frequently spotlighted for increased longevity and lower chronic disease burden, including obesity, cardiovascular disease (CVD), type II diabetes, and CRC [6–11]. The Polyp Prevention Trial stated that an intake of over 39 grams of beans per day was associated with a 65% lower rate of recurrence of advanced colorectal adenomas [11]. Bobe et al. and Hangen and Bennink both reported lower incidences of colon carcinogenesis in mice or rats consuming NB [12, 13]. Eating brown rice once a week may reduce risk of colorectal polyps by 40% [14] and diets consisting of 30% RB fiber formulation had a preventive effect on adenomas in mice [15]. RB has also been shown to modulate the human stool microbiome and metabolome that may influence CRC outcomes [16]. The numerous studies and diverse chemopreventive mechanisms for RB bioactive compounds have been reviewed in [8, 15].

There are approximately 1.2 million CRC survivors in the United States [17], and many experience co-existing chronic conditions such as CVD, diabetes, and osteoporosis, in addition to an increased risk for CRC recurrence or developing new primary cancers [18–20]. Chronic inflammation is a major risk factor [21], and can persist over long periods of time to create oxidative stress on host genetic material, leading to higher incidences of mutations [22], and influence other cancer hallmarks [23]. Mutations can activate oncogenes, render tumor suppressor genes nonfunctional, and act in a variety of ways to promote carcinogenesis [22]. Telomeres are specialized nucleoprotein structures at the ends of chromosomes that progressively shorten, and telomere integrity is critical for maintaining genomic stability [24]. Several studies have indicated that both long and short telomere lengths are associated with an increased risk for CRC development [25], and a recent study suggested this effect is likely determined by age where older individuals with short telomeres and young individuals with long telomeres are both at a higher risk for CRC [26]. Diet and nutrition status are associated with telomere length, and interventions may be promising for decreasing telomere attrition rate [27].

To our knowledge, there have been no randomized-controlled trials reporting increased consumption of NB or RB in CRC survivors, and which translate from previous findings in animal and human epidemiological studies. Given the low levels of consumption in the United States [28, 29], we implemented a Beans/Bran Enriching Nutritional Eating For Intestinal health Trial, titled BENEFIT, to advance current dietary chemoprevention research in northern Colorado (NCT01929122). Our main objectives were to determine feasibility of increasing NB or RB consumption in CRC survivors to improve overall dietary intake and to examine modulations in chronic inflammation as measured by serum biomarkers and telomere length. We hypothesized that increasing daily consumption of NB (35g/day) or RB (30g/day) in study-provided meals and snacks was feasible to increase dietary fiber intake, and would not elicit gastrointestinal distress when compared to a control group. Additionally, we hypothesized that these daily amounts of NB powder or RB consumed would meet the 5–10% intake that showed efficacy for CRC prevention in animals [8, 12, 13, 15].

Materials and Methods

Study design

A four-week, randomized-controlled, single-blinded, three-arm dietary intervention trial recruited CRC survivors through the University of Colorado Health-North (UCH-North) Cancer Center Network. Eligibility included: 1) more than four months post cancer treatment (e.g. chemotherapy or radiation), 2) no history of other malignancies besides a CRC diagnosis, 3) no history of food allergies or major dietary restrictions, 4) not currently pregnant or lactating, 5) a non-smoker, 6) not taking antibiotics within the month prior to enrollment, and 7) no history of gallstones.

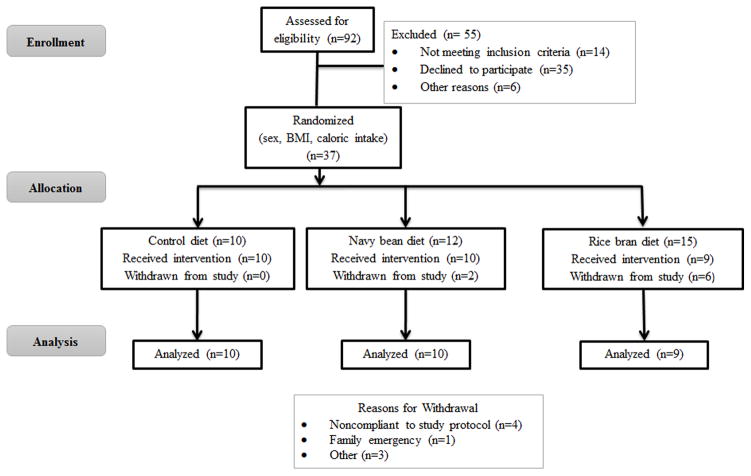

Participants who met eligibility criteria were randomized by body mass index (BMI), sex, and daily caloric intake. The Colorado State University Research Integrity and Compliance Review Board and the UCH-North Institutional Review Board approved this study protocol and informed consent (Protocol #s 09-1530H and 10-1038, respectively). Written informed consent was obtained from all individuals. Figure 1 illustrates the CONSORT flow of participants.

Figure 1.

Participation and recruitment into the study based on the CONSORT Statement guidelines.

Participants completed a baseline 3-day food log, which included recording all food and drink consumed on two weekdays (Monday-Thursday) and one weekend day (Friday-Sunday), as previously described [30]. The food logs were analyzed using Nutritionist Pro™ (Axxya Systems, Redmond, WA) and averaged total caloric intake was used for randomization. Four participants did not complete the baseline food log as it became part of the study protocol after their enrollment began.

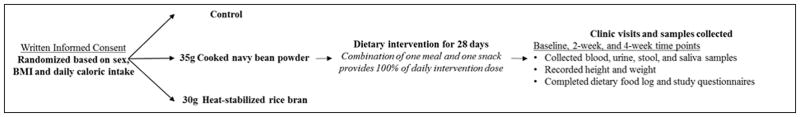

Participants completed three scheduled study visits at baseline, week 2, and week 4. Fasted blood samples were collected at each study visit by venipuncture. Blood was processed for a serum lipid panel analysis completed by UCH-North. Plasma and peripheral blood serum mononuclear cells (PBMC) were processed from whole blood and stored for inflammatory biomarkers and telomere length analyses (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Beans/Bran Enriching Nutritional Eating For Intestinal Health Trial study design overview.

For the first 13 participants, the study coordinator asked each participant at the study visits to report any gastrointestinal (GI) discomfort issues with the intervention. While no major issues were reported, our interim analysis indicated that a validated questionnaire was needed to confirm study feasibility [30]. We adapted a questionnaire that included five questions from 2 prior studies measuring perceptions on GI symptoms during a dry bean dietary intervention [31, 32]. This questionnaire was provided to n=16 participants to quantify any GI concerns by answering questions about changes in flatulence frequency, stool frequency, stool consistency, and bloating. If they experienced any of these symptoms within the past 2 weeks, participants recorded how it changed (e.g. increase/decrease) and rated the severity of the change (1=little change, 5=a lot of change). Additionally, participants recorded if any of these symptoms interfered with daily activities. The questionnaire was completed at each study visit.

Study food development

Seven meals and six snacks were developed for each of the three study arms (control, cooked NB powder, and heat-stabilized RB) and covered a range of food preferences as previously described [16, 30]. The control meals and snacks contained the same ingredients as the intervention meals, but did not have NB or RB included. Consumption of one meal and one snack was equal to the daily required intervention amount across control, cooked NB powder (35 g), and heat-stabilized RB groups (30 g). Control and intervention recipes were designed to provide comparable quantities of calories and macronutrients [30]. Complete nutritional analysis was done for each recipe using the Nutritionist Pro™ Diet Analysis Module.

Archer Daniels Midland (ADM) Edible Bean Specialties, Inc. supplied the cooked NB powder (Decatur, IL). The bean powders were processed from ground cooked navy beans by washing, soaking, and cooking whole beans and then were ground and dehydrated to create a powder form [33]. NB powder was used instead of whole navy beans to ensure participant blinding to study group and ease of dietary inclusion into a variety of meals and snacks. A recent study indicated that cooked beans in powder form have similar and comparable glycemic index to whole beans [34] and supports that bean powder consumption is reflective of whole beans. The United States Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service (USDA-ARS) Dale Bumpers National Rice Research Center provided RB that was polished from U.S. rice varieties named Calrose, Dixiebelle, and Neptune. RB is prone to fat oxidation and heat stabilization was performed to prolong shelf life as previously described [16]. Table 1 illustrates the nutrient composition of NB powder and RB for the amount consumed by the participants [33, 35].

Table 1.

Nutrient content of cooked navy bean powder and heat-stabilized rice bran in the daily consumed amounts provided for study participants [33, 35]

| Nutrient | Navy Bean Powder (35 g) | Rice bran (30 g) |

|---|---|---|

| Calories (kcal) | 110 | 95 |

| Protein (g) | 9 | 4 |

| Carbohydrate (g) | 23 | 15 |

| Fat (g) | 1 | 6 |

| Total Fiber (g) | 9 | 6 |

| Iron (mg) | 1.8 | 5 |

| Calcium (mg) | 100 | 17 |

| Sodium (mg) | 10 | 2 |

| Potassium (mg) | 1000 | 446 |

| Thiamin (Vitamin B1) (mg) | 0.3 | 0.83 |

| Niacin (Vitamin B3) (mg) | 1.5 | 10 |

| Pyridoxine (vitamin B6) (mg) | 0.25 | 1.2 |

| Total Folate (μg) | 40 | 19 |

Dietary intervention

Participants were given a two-week supply of frozen study-provided foods that included written instructions on thawing and reheating each meal and snack. To ensure participants remained blinded, study-provided meals and snacks were coded so that only the study coordinator knew group assignments. Participants consumed one study meal and one study snack daily that provided approximately one-third of their daily intake. They were free-living for the remainder of their daily intake needs.

Compliance to the dietary intervention was determined by recording the study meal and snack that participants consumed each day by increments of 25%, 50%, 75%, or 100% [30]. Similar to their baseline food log, weekly logs were analyzed using NutritionistPro™ for average daily caloric intake, macronutrient, amino acid, vitamin, and mineral profile assessments. Additionally, all food logs were analyzed for food group intake levels (e.g. cups/day, g/day) for fruit, vegetables, dry beans, and rice bran.

We also determined how much 35 g/day NB powder and 30g/day RB contributed to daily caloric intake. Participants’ food logs listed any additional dry beans or brown rice consumption and their amounts. Our daily dietary intervention provided 110 kcal to total caloric intake from 35 g of NB powder and 95 kcal from 30 g RB [33, 35]. The following equations were used to determine percent intake of NB and RB for each participant:

Serum inflammatory biomarker and telomere length analyses

C-reactive protein (CRP) concentrations were measured from plasma samples using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) protocol from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Serum amyloid A (SAA) concentrations were measured using an ELISA protocol from Abazyme (Cambridge, MA). All samples were thawed on ice, diluted in water, and aliquoted into pre-coated 96-well plates according to manufacturers’ guidelines. After coating, applying sample and wash steps, we incubated with a CRP or SAA conjugate solution. A final incubation with a chromogenic substrate was completed, using 2 N sulfuric acid. Optic density (OD) at 450 nm was measured using a Cytation3 plate reader (BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT). OD values were compared to standard solutions and CRP concentrations were interpolated using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) according to a fourth order polynomial standard curve.

Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) concentrations were measured using endpoint chromogenic reaction following a protocol from Lonza (Basel, Switzerland). Samples were thawed on ice, diluted in endotoxin-free reagent water, and heated to 75°C for 5 min to heat inactivate proteases. Samples were then aliquoted into sterile 96-well plates and incubated with Limulus Amebocyte Lysate for 10 min at 37°C. A chromogenic substrate was added and incubation continued for 6 min at 37°C. The reaction was stopped using 25% glacial acetic acid. Color change relative to the standards was determined using the Cytation3 plate reader with an OD reading at 405 nm. LPS concentrations were interpolated using GraphPad Prism according to a linear standard curve.

Genomic DNA samples were used for telomere length estimation. DNA was isolated from individual PBMC samples using a DNeasy Kit (QIAgen, Valencia, CA). DNA samples were stored at −20 °C prior to telomere length measurement. After thawing, individual sample DNA concentrations were quantified using a Cytation3 plate reader. DNA purity was assessed by A260/280 ratio with a range of 1.8–2.0 used for pure DNA.

Relative telomere length was analyzed using a monochrome multiplex qPCR method [36], with the following modifications: the final concentration of the reagents in the qPCR reaction were 1x GoTaq qPCR Master Mix (Promega), 900 nM telg and telc telomere primer pair, 400 nM albu and albd albumin primer pair, and 10 ng genomic DNA from PBMCs. The stated thermal cycling profile was carried out in 96-well plates compatible with a BioRad CFX96/C1000 Thermal Cycling System. Upon completion of data collection, CFX manager Software 3.1 was used to generate standard curves for the telomere signal and the albumin signal [37]. Relative telomere length is reported as a number reflecting the ratio between the telomere and albumin signals, i.e. the ratio is set to 1 for the unrelated reference DNA, so that values above 1 indicate a longer telomere length than the reference, and the values less than 1 indicate a shorter telomere length than the reference. Telomere lengths were measured at baseline and week 4 time points only.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis was completed on participant characteristics, including serum biomarkers and telomere length, as well as nutrient intake data using Statistical Analysis System (SAS) V9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). For all outcomes that were continuous, ranks were used (due to small sample size) to analyze the data using linear regression analysis and to compare the outcomes between diet and time categories. The analysis did adjust for repeated measures from the same individual over time. Spearman’s rho (non-parametric) was used to assess correlation between the characteristic variables and telomere length. The medians are reported to describe the data. A Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the distribution of genders across the diet groups. A p-value of 0.05 was applied for statistical significance.

Results

A total of 37 CRC survivors who had been diagnosed with CRC between 2001–2013 were randomized to one of three study groups. There were 29 participants that successfully completed the 4-week pilot dietary intervention trial between August 2010 and December 2014 (Figure 1). Eight participants withdrew from the trial due to noncompliance (n=4), family emergency (n=1), and other reasons (n=3). No adverse events were reported and only one unanticipated problem occurred, which was due to an unreported food intolerance issue. Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 2 with significant differences in total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, vegetable consumption, iron intake, and zinc intake.

Table 2.

Baseline study participant characteristics across study groups1

| Characteristic | Control (n=10) | Navy Bean Powder (n=10) | Rice Bran (n=9) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 64 ± 14 (65) | 59 ± 12 (58) | 62 ± 8 (63) | 0.4843 |

| Sex | ||||

| Males (%) | 4 (40%) | 4 (40%) | 4 (44%) | 1 |

| Females (%) | 6 (60%) | 6 (60%) | 5 (56%) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.3 ± 3.3 (26.1) | 28.5 ± 7.9 (26.6) | 28.7 ± 5.2 (31.5) | 0.785 |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 167 ± 44 (156)a | 186 ± 40 (195)a,b | 209 ± 45 (208)b | 0.1259 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 87 ± 33 (72)a | 109 ± 33 (112)a,b | 124 ± 41 (127)b | 0.0823 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 52 ± 19 (51) | 52 ± 11 (51) | 53 ± 15 (47) | 0.9449 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 146 ± 68 (142) | 124 ± 81 (106) | 161 ± 101 (114) | 0.6555 |

| SAA (μg/mL) | 3.83 ± 1.04 (4.16) | 3.63 ± 1.13 (4.17) | 4.01 ± 0.34 (3.86) | 0.89 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 0.84 ± 1.57 (0.24) | 2.64 ± 3.96 (0.59) | 2.05 ± 2.77 (0.29) | 0.274 |

| LPS (EU/mL) | 0.17 ± 0.04 (0.17) | 0.15 ± 0.04 (0.15) | 0.17 ± 0.07 (0.14) | 0.564 |

| Telomere Length2 | 0.78 ± 0.28 (0.78) | 0.84 ± 0.18 (0.80) | 0.73 ± 0.17 (0.70) | 0.4587 |

| Fruit (cups/day) | 1.5 ± 0.9 (1.25) | 1.1 ± 0.9 (1.0) | 1.4 ± 0.9 (1.3) | 0.6953 |

| Vegetable (cups/day) | 1.4 ± 0.6 (1.3)a,b | 1.3 ± 1.5 (0.5)a | 2.0 ± 1.5 (1.6)b | 0.0793 |

| Dry Beans (g/day) | 7 ± 10 (2.5) | 12.5 ± 13 (7) | 9 ± 15 (0) | 0.7194 |

| Rice bran (g/day) | 0.1 ± 0.4 (0) | 0.1 ± 0.3 (0) | 1.6 ± 3 (0) | 0.229 |

| Calories (kcal) | 2096 ± 818 (1894) | 1919 ± 496 (1765) | 1945 ± 283 (1953) | 0.811 |

| Protein (g) | 81 ± 32 (84) | 73 ± 24 (70) | 75 ± 9 (75) | 0.6006 |

| Fat (g) | 84 ± 42 (71) | 69 ± 25 (63) | 77 ± 14 (75) | 0.6778 |

| Carbohydrates (g) | 268 ± 114 (253) | 251 ± 70 (229) | 238 ± 57 (253) | 0.933 |

| Total Fiber (g) | 30 ± 18 (22) | 20 ± 10 (16) | 25 ± 8 (24) | 0.4702 |

| Iron (mg) | 20 ± 14 (18)a | 11 ± 5 (10)b | 13 ± 4 (13)a,b | 0.0676 |

| Magnesium (mg) | 392 ± 226 (327) | 298 ± 225 (236) | 305 ± 66 (296) | 0.5605 |

| Zinc (mg) | 10 ± 4 (10)a | 6 ± 2 (6)b | 8 ± 2 (8)a,b | 0.0771 |

| Vitamin B1 (Thiamin) (mg) | 1.8 ± 1.4 (1.4) | 1.0 ± 0.4 (1.1) | 1.1 ± 0.2 (1.1) | 0.1824 |

| Vitamin B3 (Niacin) (mg) | 18 ± 7 (17) | 18 ± 12 (15) | 18 ± 7 (18) | 0.8975 |

| Vitamin B6 (mg) | 1.6 ± 0.7 (2.1) | 1.3 ± 0.5 (1.3) | 1.4 ± 0.2 (1.4) | 0.3271 |

| Total Folate (μg) | 409 ± 257 (413) | 261 ± 129 (260) | 278 ± 81 (255) | 0.34 |

| Alpha-Tocopherol (mg) | 13.0 ± 15.9 (5.6) | 6.2 ± 4.8 (3.2) | 5.6 ± 1.8 (6.0) | 0.6917 |

Values are reported as Average ± standard deviation; (Median). Medians in a row with superscripts without a common letter differ, p≤0.05

Relative telomere length is reported as a number reflecting the ratio between the telomere and albumin signals, values above 1 indicate a longer telomere length than the reference, and the values less than 1 indicate a shorter telomere length than the reference.

Feasibility of increasing NB and RB intake in CRC survivors

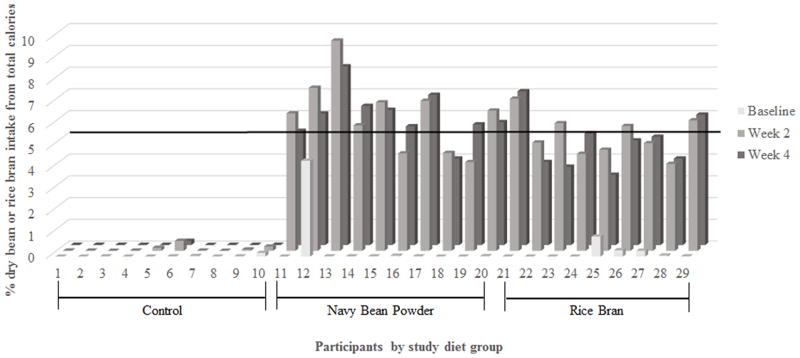

Compliance to the daily dietary intervention averaged 85% across the three study arms (80–100% range). Table 2 confirms that participants in the NB and RB groups significantly increased consumption of beans and rice bran from baseline (p≤0.01). Figure 3a illustrates each individual’s percent consumption for all beans and RB/brown rice at baseline, week 2, and week 4. The daily addition of 35 g of NB or 30 g of RB for four weeks resulted in 3.9% to 9.6% in the NB group and 3.9% to 8.3% in the RB group. The horizontal line in Figure 3a represents the minimum 5% intake amount needed each week to meet the percent consumption for chemopreventive effects observed in animals [13, 15]. No individuals in the control group met the 5% minimum intake level and consumed less than 0.5% of either dry beans or rice bran/brown rice.

Figure 3. Feasibility of dietary intervention that includes consumption of 35 g/day NB powder or 30 g/day RB.

(a) Calculated percent intake at baseline, week 2, and week 4. (b) Gastrointestinal health questionnaire responses from sixteen BENEFIT participants.

Sixteen out of twenty-nine (55%) participants completed the study questionnaire to assess changes in GI distress over the course of the intervention (Figure 3b). The criterion used to quantify GI discomfort issues included participants who responded ‘yes’ to a GI change and rated the GI discomfort level with 3 or more (out of 5 point scale).

Reports at baseline indicated that a majority of participants in control (n=4/6), NB (n=5/5), and RB (n=4/5) groups reported no major GI discomforts. Two participants in the control group reported changes in stool consistency (e.g. loose or firm) and 1 RB participant reported bloating issues. At week 2, two participants in each of the NB and RB groups reported changes in flatulence compared to 1 participant in the control group. Additionally, 1 participant in the control group reported changes in stool consistency and 1 participant in the RB group reported two or more GI symptoms. At week 4, the control group had 1 participant report stool consistency changes and another participant reported two or more GI symptoms. Two participants in the NB group reported changes in stool consistency. In the RB group, 1 participant reported changes in flatulence, and another participant reported two or more GI symptoms. No participants reported that their GI symptoms affected their daily activities.

Serum inflammatory marker analysis over 4 weeks

The diet intervention effects on inflammation and telomere length at weeks 2 and 4 are illustrated in Table 3. SAA increased from baseline to week 4 by a median of 0.26 μg/dL in the NB group (p<0.01). The NB and RB groups increased LPS levels by a median of 0.03 EU/mL from baseline to week 2 (p≤0.01). This trend was not observed in the RB group at week 4, however LPS levels remained significantly higher for the NB group at week 4 compared to baseline (p=0.047). CRP increased from baseline to week 2 and week 4 in the RB group by a median of 4.1 and 3.9 mg/L, respectively and these increased levels were significantly higher when compared to control at both time points (p≤0.01).

Table 3.

Percent change from baseline at Week 2 and Week 4 across groups1

| Characteristic | Control (n=10) | Navy Bean Powder (n=10) | Rice Bran (n=9) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Week 2 | Week 4 | Week 2 | Week 4 | Week 2 | Week 4 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Δ Control | p-value | Δ Control | p-value | Δ Navy Bean Powder | p-value | Δ Navy Bean Powder | p-value | Δ Rice Bran | p-value | Δ Rice Bran | p-value | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | −0.11 ± 0.24 (−0.05) | 0.254 | −0.16 ± 0.29 (−0.20) | 0.063 | −0.01 ± 0.32 (−0.05) | 0.600 | 0.02 ± 0.35 (0) | 0.822 | −0.39 ± 0.72 (−0.30) | 0.088 | −0.16 ± 0.44 (−0.20) | 0.450 |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | −1.7 ± 9.4 (−1.0) | 0.607 | 4.1 ± 13.7 (4.5)a | 0.507 | 0.5 ± 14.1 (0) | 0.903 | 1.5 ± 10.8 (−1.0)a,b | 0.674 | 2.2 ± 11.1 (4.0) | 0.424 | 0.1 ± 13.0 (2.0)b | 0.701 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | −2.0 ± 11.7 (1.5) | 0.692 | 3.4 ± 10.7 (1.0)a | 0.401 | −4.7 ± 11.7 (−4.0) | 0.252 | −0.9 ± 9.2 (−4.0)a,b | 0.926 | 2.8 ± 9.4 (1.0) | 0.405 | 1.1 ± 16.7 (4.0)b | 0.792 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | −2.8 ± 3.1 (−3.5) | <0.01 | 0.20 ± 5.1 (0.50) | 0.796 | −1.0 ± 5.0 (−1.5) | 0.388 | −1.3 ± 4.6 (−1.5) | 0.258 | 0 ± 4.2 (−2.0) | 0.867 | −1.7 ± 4.0 (−4.0) | 0.719 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 14.9 ± 46.2 (4.5) | 0.678 | 1.7 ± 32.3 (−4.5) | 0.321 | 31.2 ± 34.8 (25.5) | <0.01 | 18.6 ± 49.3 (20.5) | 0.065 | −3.9 ± 40.8 (6.0) | 0.496 | 2.6 ± 39.3 (9.0) | 0.665 |

| SAA (μg/dL) | 0.31 ± 0.49 (0.08) | 0.040 | 0.02 ± 0.94 (0.12) | 0.863 | −0.002 ± 0.55 (0.02) | 0.469 | 0.36 ± 0.73 (0.26) | <0.01 | −0.86 ± 0.90 (−1.2) | 0.080 | −0.45 ± 0.59 −0.47) | 0.124 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 0.97 ± 2.4 (1.7)a | 0.072 | 1.4 ± 3.5 (0.03)a | 0.235 | 1.5 ± 2.1 (0.73)a,b | 0.263 | 0.80 ± 3.1 (0.99)a,b | 0.084 | 2.7 ± 3.9 (4.1)b | 0.012 | 2.8 ± 3.7 (3.9)b | <0.01 |

| LPS (EU/mL) | 0.11 ± 0.27 (0.03) | 0.066 | 0.03 ± 0.04 (0.02) | 0.112 | 0.03 ± 0.04 (0.03) | <0.01 | 0.08 ± 0.18 (0.01) | 0.047 | 0.04 ± 0.05 (0.03) | 0.011 | −0.006 ± 0.05 (0.002) | 0.622 |

| Telomere Length2 | n/a | n/a | −0.03 ± 0.13 (−0.05) | 0.350 | n/a | n/a | −0.02 ± 0.08 (−0.005) | 0.825 | n/a | n/a | −0.007 ± 0.09 (0.004) | 0.674 |

| Fruit (cups/day) | −0.71 ± 0.98 (−0.75) | 0.033 | −0.11 ± 0.72 (−0.35) | 0.187 | −0.22 ± 0.57 (0) | 0.255 | −0.16 ± 0.55 (0) | 0.703 | −0.34 ± 0.77 (−0.25) | 0.144 | 0.15 ± 1.7 (−0.40) | 0.141 |

| Vegetable (cups/day) | −0.55 ± 0.67 (−0.60)a | <0.01 | −0.49 ± 0.97 (−0.60) | 0.049 | −0.46 ± 1.4 (0)a | 0.623 | −0.46 ± 1.3 (0) | 0.708 | −0.55 ± 1.3 (−0.75)b | 0.430 | −0.29 ± 1.2 (−0.45) | 0.369 |

| Dry beans (g/day) | 5.4 ± 7.4 (5.8)a | 0.069 | 0.75 ± 9.8 (5.0)a | 0.456 | 34.8 ± 15.5 (42.0)b | <0.01 | 35.4 ± 16.3 (37.0)b | <0.01 | 0.63 ± 15.2 (7.5)a | 0.085 | −0.50 ± 16.7 (7.5)a | 0.205 |

| Rice bran (g/day) | 1.3 ± 3.5 (0)a | 0.670 | 0.63 ± 1.8 (0)a | 0.635 | 0.06 ± 0.17 (0)a | 0.250 | 0.11 ± 0.33 (0)a | 0.940 | 28.9 ± 2.9 (30.0)b | <0.01 | 28.5 ± 2.8 (30.0)b | <0.01 |

| Calories (kcal) | 63.3 ± 653.5 (−85.5) | 0.701 | 19.0 ± 659.7 (−64.5) | 0.944 | −15.4 ± 576.7 (−81.2) | 0.997 | −22.5 ± 295.5 (−65.9) | 0.628 | 3.1 ± 158.5 (36.5) | 0.459 | 295.3 ± 406.9 (228.7) | 0.371 |

| Protein (g) | 5.9 ± 27.0 (4.7) | 0.756 | −1.5 ± 27.3 (−6.6) | 0.734 | −0.31 ± 24.5 (−2.7) | 0.955 | 1.4 ± 22.3 (−3.2) | 0.696 | 10.7 ± 10.5 (9.0) | 0.059 | 12.8 ± 17.9 (4.5) | 0.198 |

| Fat (g) | 4.7 ± 36.4 (9.7)a | 0.372 | −1.4 ± 39.8 (3.8) | 0.850 | −3.6 ± 26.7 (−1.6)b | 0.506 | −3.9 ± 18.8 (−0.07) | 0.562 | 3.2 ± 9.7 (5.3)a,b | 0.901 | 9.4 ± 23.5 (11.5) | 0.976 |

| Carbohydrates (g) | −9.8 ± 80.5 (−23.5) | 0.914 | −4.4 ± 82.2 (−7.0) | 0.764 | 10.9 ± 80.1 (4.6) | 0.921 | 12.3 ± 57.5 (25.5) | 0.179 | −3.2 ± 47.6 (4.1) | 0.407 | 54.1 ± 69.6 (66.5) | 0.129 |

| Total Fiber (g) | −2.3 ± 15.6 (−0.36)a | 0.987 | −4.3 ± 12.2 (0.1)a | 0.321 | 9.8 ± 11.4 (11.0)a,b | <0.01 | 13.0 ± 8.5 (11.7)b | <0.01 | 8.3 ± 8.3 (7.1)b | <0.01 | 10.2 ± 6.7 (7.4)b | <0.01 |

| Iron (mg) | −4.3 ± 15.5 (−1.7)a | 0.412 | −3.1 ± 10.4 (0.1)a | 0.575 | 3.0 ± 5.4 (3.9)a | 0.087 | 4.1 ± 3.3 (4.5)a | <0.01 | 7.1 ± 3.5 (7.0)b | <0.01 | 8.8 ± 7.5 (7.4)b | <0.01 |

| Magnesium (mg) | −15.5 ± 284.3 (−13.0)a | 0.568 | −31.1 ± 199.9 (30.3)a | 0.899 | 65.0 ± 239.5 (87.5)a | 0.145 | 97.9 ± 197.5 (130.8)b | <0.01 | 230.9 ± 51.0 (213.4)b | <0.01 | 229.8 ± 56.7 (236.0)c | <0.01 |

| Zinc (mg) | 1.64 ± 4.4 (0.67) | 0.366 | 0.7 ± 2.8 (−0.03) | 0.645 | 2.4 ± 3.7 (3.1) | 0.025 | 2.9 ± 3.3 (2.1) | <0.01 | 3.3 ± 2.9 (2.6) | <0.01 | 2.7 ± 2.1 (2.7) | <0.01 |

| Vitamin B1 (Thiamin) (mg) | −0.45 ± 1.2 (−0.30)a | 0.382 | −0.19 ± 1.3 (0.01)a | 0.535 | −0.04 ± 0.48 (−0.06)a | 0.882 | 0.15 ± 0.38 (0.07)b | 0.104 | 0.86 ± 0.44 (0.98)b | <0.01 | 1.0 ± 0.48 (1.0)c | <0.01 |

| Vitamin B3 (Niacin) (mg) | 1.6 ± 7.6 (0.71)a | 0.732 | 1.2 ± 6.4 (−0.24)a | 0.671 | −1.6 ± 9.2 (−1.6)a | 0.517 | −0.45 ± 10.1 (−0.98)a | 0.856 | 9.4 ± 6.2 (8.6)b | <0.01 | 8.8 ± 8.3 (8.2)b | <0.01 |

| Vitamin B6 (mg) | 0.03 ± 0.62 (−0.15)a | 0.839 | 0.04 ± 0.52 (−0.01)a | 0.670 | 0.16 ± 0.61 (0.23)a | 0.595 | 0.27 ± 0.46 (0.46)a | 0.050 | 1.4 ± 0.24 (1.3)b | <0.01 | 1.5 ± 0.54 (1.3)b | <0.01 |

| Total Folate (μg) | −46.7 ± 270.6 (0.99) | 0.707 | 15.8 ± 150.2 (69.4) | 0.927 | 24.0 ± 137.5 (44.9) | 0.413 | 64.6 ± 87.9 (72.8) | <0.01 | 83.5 ± 117.7 (101.1) | <0.01 | 97.0 ± 160.2 (86.7) | 0.146 |

| Alpha-Tocopherol (mg) | −5.5 ± 15.9 (−0.16)a | 0.658 | −6.0 ± 15.0 (−0.05)a | 0.982 | −0.06 ± 4.3 (1.3)a | 0.812 | 0.28 ± 3.7 (1.6)a | 0.423 | 2.7 ± 2.4 (2.5)b | <0.01 | 3.6 ± 2.5 (4.0)b | <0.01 |

Values are reported in change from baseline ± standard deviation (Median). Medians in a row with superscripts without a common letter differ at either Week 2 or Week 4 time point, p≤0.05

Relative telomere length is reported as a number reflecting the ratio between the telomere and albumin signals, values above 1 indicate a longer telomere length than the reference, and the values less than 1 indicate a shorter telomere length than the reference.

n/a = not applicable

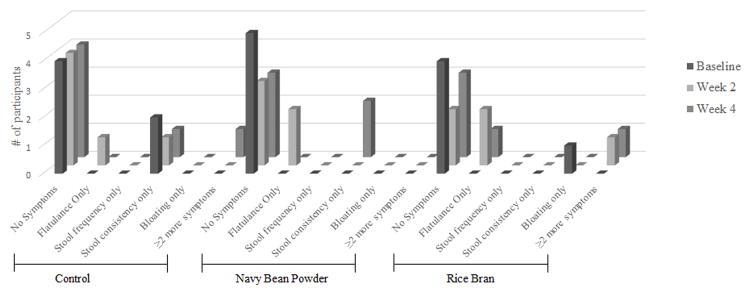

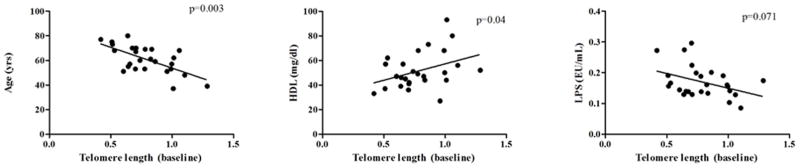

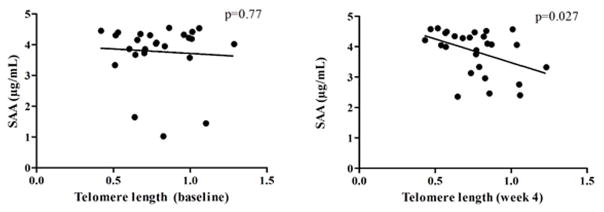

Relationship between telomere length and participant characteristics

No significant changes were observed in telomere length over the intervention period (Table 3). Telomere length data were analyzed for correlations between age, sex, BMI, total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, triglycerides, CRP, SAA, and LPS at baseline and week 4, regardless of diet group. Increasing age was found to be negatively correlated, and higher levels of HDL-cholesterol were positively correlated with telomere length at baseline (p<0.01 and p=0.04, respectively). Correlations between LPS and telomere length at baseline approached significance (p-value=0.071). Figure 4a illustrates baseline correlations between shorter telomeres with increasing age and longer telomere lengths in individuals with higher HDL-cholesterol levels. LPS negatively correlated with telomere length showing longer telomeres with lower levels of LPS.

Figure 4. Correlation analyses between telomere length and other participant characteristics at baseline and week 4 that were significant or were near-significant.

(a) Significant correlations between telomere length and age (p=0.003), HDL-cholesterol (p=0.04), and near-significant correlation with LPS (p=0.071) at baseline. Baseline telomere lengths were analyzed for correlations between age, sex, BMI, total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, triglycerides, CRP, SAA, and LPS for all participants regardless of diet intervention group. Age, HDL-cholesterol, and LPS variables showed high correlation with telomere length levels across time points. (b) Non-significant correlation between telomere length and SAA at baseline (p=0.77) and significant correlation at week 4 (p=0.027). SAA was the only variable in the correlation analysis with telomere length that became significant at week 4 across entire study cohort.

Linear regression analysis at baseline between telomere length and SAA levels showed no significant correlation (p=0.77) (Figure 4b). However, at week 4, there was a significant negative correlation (p=0.027), whereby participants with lower levels of SAA after the dietary intervention had longer telomeres.

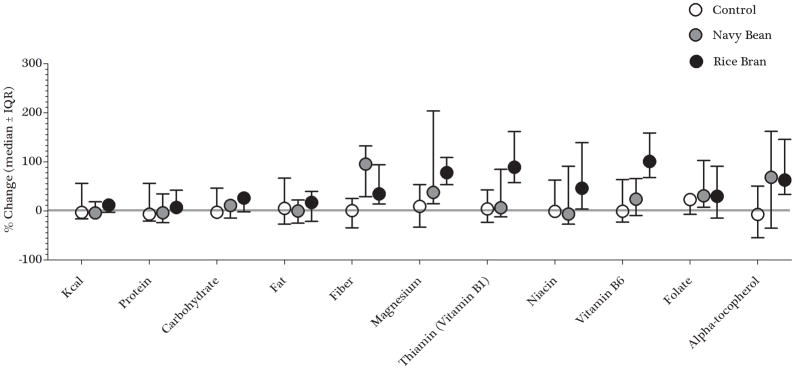

Dietary modulations with increased intake of NB or RB

Three-day food logs were analyzed at week 2 and week 4 compared to baseline levels to evaluate dietary modulations between study groups and time points. Table 3 shows macronutrient and micronutrient changes from baseline for week 2 and week 4 time points.

In this 4-week intervention, dietary fiber was the major macronutrient to significantly change in the NB and RB groups. There were no significant differences in dietary fiber between the three groups at baseline (p=0.47). The NB group consumed a median of 11 grams more dietary fiber at weeks 2 and 4 (p<0.01), and the RB group significantly consumed a medium of 7 grams more of dietary fiber at weeks 2 and 4 (p<0.01). The increased intake of NB or RB was significantly higher than dietary fiber consumption in the control group over the 4-week study (p≤0.05). Additionally, no significant change in dietary fiber was observed in the control group over time.

Intake levels of micronutrients that significantly changed over time included iron, magnesium, zinc, thiamin, niacin, vitamin B6, total folate, and alpha-tocopherol. The NB group increased iron levels by a median of 4.5 mg/day from baseline to week 4 (p<0.01). The RB group also increased iron levels by a median of 7 mg at weeks 2 and 4 (p<0.01). At week 2, iron levels in the RB group were higher than both control and NB groups and this trend continued into week 4 (p=0.02 and p=0.04, respectively). Over the 4-week intervention, both NB and RB groups significantly increased magnesium levels. The RB group increased magnesium levels from baseline by a median of 213 mg at week 2 and 236 mg at week 4 (p<0.01). These increases from baseline levels were significantly higher than magnesium levels consumed in control and NB groups (p<0.01). Increased intake of magnesium for the NB group compared to control at week 4 was also significant (p=0.02). Zinc intake significantly increased over time in both NB and RB groups. The NB group had increased levels at week 2 and week 4 compared to baseline (p=0.02 and p<0.01, respectively). The RB group increased zinc intake levels at week 2 and week 4 compared to baseline (p<0.01). No significant changes were observed in the control group over time for iron, magnesium, or zinc.

With regards to B-vitamin intake from foods, thiamin levels significantly increased by a median of 1 mg in the RB group at from baseline to week 2 and week 4 (p<0.01). The increased intake level was significantly different compared to control and NB groups over time (p<0.01). Intake levels of niacin and vitamin B6 also significantly increased in the RB group over time. At week 4, the NB group increased levels of vitamin B6 from baseline levels (p=0.05).

For folate levels, the NB group increased intake with a median of 73 μg/day compared to baseline levels at week 4 (p<0.01). Alpha-tocopherol intake was higher in the RB group with a median increase of 2.5 mg/day at week 2 and 4.0 mg/day at week 4 (p<0.01). Alpha-tocopherol levels in the RB group were significantly higher compared to control and NB groups at both week 2 (p=0.02 and p=0.01, respectively) and week 4 time points (p=0.04 and p=0.035, respectively). No significant changes were observed in either control or NB groups for alpha-tocopherol intake over time.

Figure 5 summarizes the percent change from baseline to week 4 of nutrients across diet groups to visualize whether the dietary intervention increased various nutrient intake levels after a 4-week intervention. The NB group significantly increased dietary fiber by a median of 96% compared to control with a median of 23% (p=0.02) and magnesium by 47% compared to control at 35% (p=0.04). The RB group also increased magnesium levels by 78% compared to control (p<0.01), as well as vitamin B6 with a median increase of 101% compared to both control and NB groups with medians of 26% and 27%, respectively (p<0.01).

Figure 5. Percent change from baseline to week 4 of selected nutrients across diet groups (*.

=Significant to control group; p<0.05)

Discussion

This pilot study established the feasibility of increasing NB or RB consumption in CRC survivors to levels that previously showed dietary chemopreventive bioactivity. There have been several epidemiological and animal studies completed to reveal the potential for chemopreventive effects of NB and RB consumption, yet to our knowledge, this is the first randomized-controlled study to investigate how increasing NB or RB intake in CRC survivors helped to increase intakes of dietary fiber, iron, zinc, thiamin, niacin, vitamin B6, folate, and alpha-tocopherol (Table 2 and Figure 5).

Current U.S. dietary recommendations for legume intake (including dry beans) indicate a minimum of 1.5 cups/week (based on a 2,000 calorie diet), which is approximately 37.5 g/day [38]. At baseline, there was one participant in the NB group consuming 37.5 g/day of dry beans to meet the recommendation. By the end of the 4-week trial, all participants in the NB group were consuming more than 37.5 g/day of dry beans/legumes. There were 2 participants that consumed over 60 g/day. Participants in the control and RB groups consumed dry beans, but did not meet the recommended levels. The conversion of RB consumption to meet current whole grain dietary recommendations is possible, as the white rice portion of the whole grain is missing. Providing 30 grams of RB per day is the same amount of bran available in 1.5 cups of brown rice (300 grams) as the bran comprises ~10% of the total grain [35, 39].

In regards to previous chemoprevention literature, consuming 35 g/day NB powder or 30 g/day RB allowed a majority of study participants to meet the 5% dietary intake level that was shown to inhibit colon tumor formation (Figure 3a) [13, 15]. Calculating the percent consumption of the intervention ingredients in each participant provides relevant dose information to help translate findings from animal CRC studies and identify the levels of intake that demonstrate chemopreventive actions.

Another important finding was that no major changes in GI symptoms occurred over the course of the intervention and we confirmed the lack of perceived GI distress that may be anticipated with consuming the study-provided foods. Moreover, no participants withdrew from the study due to the intervention meals and snacks affecting their GI health status. Blinding participants to study intervention grouping may have helped reduce the misconception that these high fiber foods promote GI discomforts, including bloating, increased flatulence, or stool consistencies [28]. Given that NB or RB-rich diets did not cause more GI distress compared to a control diet, we confirmed that promoting consumption of these amounts was safe and feasible in CRC survivors and merits further research for CRC control and prevention efficacy in follow-up cohorts.

The current dietary reference intakes (DRI) for adults for total fiber ranges between 21–38g/day depending on age and sex [38]. While all groups had a median intake of fiber within the range, only the NB and RB groups maintained higher amounts at Week 2 and Week 4. Dietary fiber is a major macronutrient to show convincing evidence for decreased CRC risk [3, 4]. The actual mechanisms for dietary fiber’s protective role in CRC prevention is likely multi-faceted as fiber helps to maintain a healthy gut through decreased oro-fecal transit time, as well as produces short-chain fatty acids that reduce gut inflammation and promote apoptosis. Additionally, it’s possible that not all foods containing fiber are created equal when it comes to GI health. Park and colleagues examined individuals’ intake of foods containing dietary fiber in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study and found that dietary fiber from whole grains and beans had a more protective effect on all-cause mortality when compared to fiber from fruits and vegetables [7]. Diets of CRC survivors have shown to have poor adherence to dietary guidelines, including fiber consumption, indicating a strong need for more cancer survivor research involving dietary interventions [40]. While BENEFIT was designed to first determine feasibility, this study revealed significant changes in dietary intakes after controlling for approximately one-third of the total diet. The dietary fiber increase was of major importance for participants consuming NB or RB compared to their baseline, as well as to the control group over time because of the relevancy to CRC prevention.

Micronutrients in the form of dietary supplements have been investigated for cancer prevention and control outcomes. While in vitro and animal studies have found positive outcomes in regards to chemopreventive effects of beta-carotene, selenium, or alpha-tocopherol, to name a few [41], the translation to human clinical trials via dietary supplements have not been reproducible, with some dietary supplementation trials causing more harm than good [42]. Due to these negative responses to dietary supplements for cancer control and prevention, the American Institute for Cancer Research (AICR) recommends not taking supplements to reduce cancer risk [4]. The increasing evidence for consuming whole foods, including staple foods like beans and brown rice/rice bran, which have chemopreventive effects provides strong rationale for foods to play a stronger role than supplements to reduce CRC risk and recurrence. The synergistic effects from various nutrients and bioactive food components consumed from whole grains and beans could reduce CRC risk and recurrence and merit application to CRC survivors, as well as the general population [7, 43].

Consumption of whole grains and dry beans have had an extensive amount of research to reduce CVD, particularly through lowering cholesterol and regulation of bile acid and lipid metabolism [6, 44]. However, most of these studies were completed over a longer period of time than 4 weeks [45–47]. Serum biomarker analysis of inflammatory cytokines and endotoxins in this study indicated several aspects of health that may be useful for determining ranges that are considered normal for survivors, such as SAA within a range of 1.0–5.0 μg/mL [48], CRP – 1.0–3.0 mg/L [49], and LPS – 0.15–0.35 EU/mL [50]. Increased SAA levels have been related to cancer severity and play a role in the induction of metastasis [51]. Even though there was a significant increase in SAA levels between baseline and week 4 for the NB group, levels remained within the normal range, and similarly levels of CRP significantly increased in the RB group from baseline to week 4 and should be monitored over longer periods of intake. Higher chronic CRP levels have been directly linked with an increased risk for recurrence, as well as increased fatality risk upon recurrence and overall survival [52, 53]. Increased serum endotoxin levels may be indicative of a permeable intestinal lining and is related to decreased digestive health, as well as less absorption of nutrients and inflammation that merits further investigation in CRC survivors [54].

Shortened telomeres are associated with increased age and risk of age-related degenerative pathologies including cancer; dysfunctional telomeres have been shown in CRC and proposed as contributors to the process of carcinogenesis [55]. Although telomere length is influenced by a variety of lifestyle factors, including diet, there were no significant changes in telomere length over the 4 week course of the current study; however significant relationships with several variables were observed. These included age, HDL-cholesterol, LPS, and SAA, and in general were associated with healthier/improved profiles that agree with previously reported outcomes [56–59]. Results support the value of monitoring telomere length in diet intervention studies, as telomere maintenance represents a general measure of health (not diagnostic in and of itself). Dietary components, including dietary fiber, and telomere length should also be further understood as lifestyle factors that can aid in CRC secondary prevention and other chronic co-morbidities [60].

With promising health promoting outcomes associated with increased consumption of whole grains and beans for longer lifespan and reduced risk of CRC and other chronic conditions [6, 9, 7, 8, 10–14], higher intakes of these foods should be emphasized by clinicians and dietitians for CRC survivors to meet current dietary recommendations. Adding NB and RB in powder form to common U.S. meals and snacks represents a novel way to increase intake and strengthened the adherence to this study protocol. Our findings of high compliance to the 4-week dietary intervention, along with minimal GI concerns and improved nutritional intake provide rationale for pursuing longer interventions that evaluate a combination of NB and RB for effects on primary and secondary CRC prevention. Even though this pilot study had a low number of participants and a short study duration to measure any major chemopreventive outcome effects, the investigation confirmed feasibility of consuming NB or RB in CRC survivors. Future research should focus on the confirmation of dietary biomarkers of dry beans, including NB, which was recently reported in parallel human and mouse studies [61], as well as further establishing RB dietary biomarkers to allow for stronger CRC control and prevention outcomes. Additionally, more effort is needed to increase consumption of these healthy staple foods through public health education and awareness.

For many individuals, the diagnosis of CRC provides strong motivation for dietary improvements. Foods with multiple bioactive components and nutrients play a big role in the development and prevention of CRC. Although many studies have taken a reductionist approach to focus on individual nutrients and their effects on cancer, more research is needed on whole foods, such as NB and RB, over long periods of time. Consumption of whole foods for healthful eating and disease prevention should be an achievable goal for CRC survivors.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by NIH 1R21CA161472, University of Colorado Cancer Center – Division of Cancer Prevention and Control, and the Dry Bean Health Research Group. We appreciate the University of Colorado Health-North Cancer Clinical Research group, specifically Joann Lovins and Erica Dickson, for helping with participant recruitment and assistance with study implementation. We thank Gordon Gregory from Archer Daniels Midland Edible Bean Specialties and Dr. Anna McClung from the United States Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service (USDA-ARS) Dale Bumpers National Rice Research Center for supplying the cooked navy bean powders and heat-stabilized rice bran. We also thank Katie Schmitz, Genevieve Forster, Amy Sheflin, Cadie Tillotson, Allie Reava, Kerry Gundlach, and Brianna Nervig for technical support with meal and snack design and food preparations, and all our study participants.

References

- 1.Siegel R, DeSantis C, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(2):104–17. doi: 10.3322/caac.21220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(1):5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Cancer Research Fund / American Institute for Cancer Research. Food, nutrition, physical activity, and the prevention of colorectal cancer. 2011. Continuous update project report. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perera PS, Thompson RL, Wiseman MJ. Recent evidence for colorectal cancer prevention through healthy food, nutrition, and physical activity: Implications for recommendations. Curr Nutr Rep. 2012;1:44–54. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aune D, Chan DSM, Lau R, Vieira R, Greenwood DC, et al. Dietary fibre, whole grains, and risk of colorectal cancer: Systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Brit Med J. 2011:343. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d6617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hayat I, Ahmad A, Masud T, Ahmed A, Bashir S. Nutritional and health perspectives of beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.): An overview. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2014;54(5):580–92. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2011.596639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park Y, Subar AF, Hollenbeck A, Schatzkin A. Dietary fiber intake and mortality in the NIH-AARP diet and health study. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(12):1061–8. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henderson AJ, Ollila CA, Kumar A, Borresen EC, Raina K, et al. Chemopreventive properties of dietary rice bran: Current status and future prospects. Adv Nutr. 2012;3(5):643–53. doi: 10.3945/an.112.002303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schatzkin A, Mouw T, Park Y, Subar AF, Kipnis V, et al. Dietary fiber and whole-grain consumption in relation to colorectal cancer in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85(5):1353–60. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.5.1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dipti SS, Bergman C, Indrasari SD, Herath T, Hall R, et al. The potential of rice to offer solutions for malnutrition and chronic diseases. Rice. 2012;5(1):16. doi: 10.1186/1939-8433-5-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lanza E, Hartman TJ, Albert PS, Shields R, Slattery M, et al. High dry bean intake and reduced risk of advanced colorectal adenoma recurrence among participants in the Polyp Prevention Trial. J Nutr. 2006;136(7):1896–903. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.7.1896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bobe G, Barrett KG, Mentor-Marcel RA, Safflotti U, Young MR, et al. Dietary cooked navy beans and their fractions attenuate colon carcinogenesis in Azoxymethane-Induced Ob/Ob mice. Nutr Cancer. 2008;60(3):373–81. doi: 10.1080/01635580701775142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hangen L, Bennink MR. Consumption of black beans and, navy beans (Phaseolus vulgaris) reduced azoxymethane-induced colon cancer in rats. Nutr Cancer. 2002;44(1):60–5. doi: 10.1207/S15327914NC441_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tantamango YM, Knutsen SF, Beeson WL, Fraser G, Sabate J. Foods and food groups associated with the incidence of colorectal polyps: The Adventist Health Study. Nutr Cancer. 2011;63(4):565–72. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2011.551988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Norris L, Malkar A, Horner-Glister E, Hakimi A, Ng LL, et al. Search for novel circulating cancer chemopreventive biomarkers of dietary rice bran intervention in Apc mice model of colorectal carcinogenesis, using proteomic and metabolic profiling strategies. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2015 doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201400818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sheflin AM, Borresen EC, Wdowik MJ, Rao S, Brown RJ, et al. Pilot dietary intervention with heat-stabilized rice bran modulates stool microbiota and metabolites in healthy adults. Nutrients. 2015;7(2):1282–300. doi: 10.3390/nu7021282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeSantis CE, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, Siegel RL, Stein KD, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(4):252–71. doi: 10.3322/caac.21235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rock CL, Doyle C, Demark-Wahnefried W, Meyerhardt J, Courneya KS, et al. Nutrition and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(4):243–74. doi: 10.3322/caac.21142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edwards BK, Noone AM, Mariotto AB, Simard EP, Boscoe FP, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2010, featuring prevalence of comorbidity and impact on survival among persons with lung, colorectal, breast, or prostate cancer. Cancer. 2014;120(9):1290–314. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El-Shami K, Oeffinger KC, Erb NL, Willis A, Bretsch JK, et al. American Cancer Society colorectal cancer survivorship care guidelines. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015 doi: 10.3322/caac.21286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khansari N, Shakiba Y, Mahmoudi M. Chronic inflammation and oxidative stress as a major cause of age-related diseases and cancer. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2009;3(1):73–80. doi: 10.2174/187221309787158371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420(6917):860–7. doi: 10.1038/nature01322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Colotta F, Allavena P, Sica A, Garlanda C, Mantovani A. Cancer-related inflammation, the seventh hallmark of cancer: links to genetic instability. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30(7):1073–81. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blackburn EH. Structure and function of telomeres. Nature. 1991;350(6319):569–73. doi: 10.1038/350569a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qin Q, Sun JW, Yin JY, Liu L, Chen JG, et al. Telomere length in peripheral blood leukocytes is associated with risk of colorectal cancer in Chinese population. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boardman LA, Litzelman K, Seo S, Johnson RA, Vanderboom RJ, et al. The association of telomere length with colorectal cancer differs by the age of cancer onset. Clin Transl Gastroen. 2014:5. doi: 10.1038/ctg.2014.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paul L. Diet, nutrition and telomere length. J Nutr Biochem. 2011;22(10):895–901. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lucier G, Lin BH, Allshouse J, Kantor LS. Factors affecting dry bean consumption in the United States (2000). US Department of Agriculture. Vegetables and Specialties. [Accessed September 2015];Economic Research Service website. http://www.agmrc.org/media/cms/DryBeanConsumption_1BB21AC669838.pdf.

- 29.Batres-Marquez SP, Jensen HH, Upton J. Rice consumption in the United States: Recent evidence from food consumption surveys. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(10):1719–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borresen EC, Gundlach KA, Wdowik M, Rao S, Brown RJ, Ryan EP. Feasibility of increased navy bean powder consumption for primary and secondary colorectal cancer prevention. Curr Nutr Food Sci. 2014;10(2):112–9. doi: 10.2174/1573401310666140306005934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Winham DM, Hutchins AM. Perceptions of flatulence from bean consumption among adults in 3 feeding studies. Nutr J. 2011 doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-10-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pittaway JK, Ahuja KDK, Robertson LK, Ball MJ. Effects of a controlled diet supplemented with chickpeas on serum lipids, glucose tolerance, satiety and bowel function. J Am Coll Nutr. 2007;26(4):334–40. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2007.10719620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Archer Daniels Midland Company. [Accessed September 2015];VegeFull™ Cooked Ground Bean Ingredients. 2011 Available at: www.adm.com/vegefull.

- 34.Anderson GH, Liu YD, Smith CE, Liu TT, Nunez MF, et al. The acute effect of commercially available pulse powders on postprandial glycaemic response in healthy young men. Brit J Nutr. 2014;112(12):1966–73. doi: 10.1017/S0007114514003031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.US Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Nutrient Data Laboratory. USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 27 (slightly revised). Version Current. 2015 May; Internet: http://ndb.nal.usda.gov/

- 36.Cawthon RM. Telomere length measurement by a novel monochrome multiplex quantitative PCR method. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(3):e21. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zahran S, Snodgrass JG, Maranon DG, Upadhyay C, Granger DA, Bailey SM. Stress and telomere shortening among central Indian conservation refugees. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(9):E928–E36. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1411902112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2015 – 2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. (8) 2015 Dec; Available at http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/

- 39.Borresen EC, Ryan EP. Rice Bran: A Food Ingredient with Global Public Health Opportunities. In: Watson R, Preedy V, Zibadi S, editors. Wheat and Rice in Disease Prevention and Health: Benefits, risks, and mechanisms of whole grains in health promotion. Oxford, UK: Elsevier; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang FF, Liu S, John EM, Must A, Demark-Wahnefried W. Diet quality of cancer survivors and noncancer individuals: Results from a national survey. Cancer. 2015 doi: 10.1002/cncr.29488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin C, Vitamin E, Selenium, and Carotenoids: Food and Nutrition Board. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martinez ME, Jacobs ET, Baron JA, Marshall JR, Byers T. Dietary supplements and cancer prevention: Balancing potential benefits against proven harms. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104(10):732–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rebello CJ, Greenway FL, Finley JW. Whole grains and pulses: A comparison of the nutritional and health benefits. J Agric Food Chem. 2014;62(29):7029–49. doi: 10.1021/jf500932z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Friedman M. Rice brans, rice bran oils, and rice hulls: composition, food and industrial uses, and bioactivities in humans, animals, and cells. J Agric Food Chem. 2013;61(45):10626–41. doi: 10.1021/jf403635v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ha V, Sievenpiper JL, de Souza RJ, Jayalath VH, Mirrahimi A, et al. Effect of dietary pulse intake on established therapeutic lipid targets for cardiovascular risk reduction: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Can Med Assoc J. 2014;186(8):E252–62. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.131727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jones JM, Engleson J. Whole grains: benefits and challenges. Annu Rev Food Sci Technol. 2010;1:19–40. doi: 10.1146/annurev.food.112408.132746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith CE, Tucker KL. Health benefits of cereal fibre: a review of clinical trials. Nutr Res Rev. 2011;24(1):118–31. doi: 10.1017/S0954422411000023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Biran H, Friedman N, Neumann L, Pras M, Shainkin-Kestenbaum R. Serum amyloid A (SAA) variations in patients with cancer: Correlation with disease activity, stage, primary site, and prognosis. J Clin Pathol. 1986;39(7):794–7. doi: 10.1136/jcp.39.7.794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gurven M, Kaplan H, Winking J, Finch C, Crimmins EM. Aging and inflammation in two epidemiological worlds. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(2):196–9. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.2.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ghanim H, Abuaysheh S, Sia CL, Korzeniewski K, Chaudhuri A, Fernandez-Real JM, et al. Increase in plasma endotoxin concentrations and the expression of Toll-like receptors and suppressor of cytokine signaling-3 in mononuclear cells after a high-fat, high-carbohydrate meal: implications for insulin resistance. Diabetes care. 2009;32(12):2281–7. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hansen MT, Forst B, Cremers N, Quagliata L, Ambartsumian N, Grum-Schwensen B, et al. A link between inflammation and metastasis: serum amyloid A1 and A3 induce metastasis, and are targets of metastasis-inducing S100A4. Oncogene. 2015;34(4):424–35. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mori K, Toiyama Y, Saigusa S, Fujikawa H, Hiro J, et al. Systemic analysis of predictive biomarkers for recurrence in colorectal cancer patients treated with curative surgery. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60(8):2477–87. doi: 10.1007/s10620-015-3648-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Woo HD, Kim K, Kim J. Association between preoperative C-reactive protein level and colorectal cancer survival: a meta-analysis. Cancer Causes Control. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10552-015-0663-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Szabo G, Bala S, Petrasek J, Gattu A. Gut-liver axis and sensing microbes. Dig Dis. 2010;28(6):737–44. doi: 10.1159/000324281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tanaka H, Beam MJ, Caruana K. The presence of telomere fusion in sporadic colon cancer independently of disease stage, TP53/KRAS mutation status, mean telomere length, and telomerase activity. Neoplasia. 2014;16(10):814–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2014.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen W, Kimura M, Kim S, Cao X, Srinivasan SR, et al. Longitudinal versus cross sectional evaluations of leukocyte telomere length dynamics: Age-dependent telomere shortening is the rule. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66(3):312–9. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen W, Gardner JP, Kimura M, Brimacombe M, Cao X, et al. Leukocyte telomere length is associated with HDL cholesterol levels: The Bogalusa heart study. Atherosclerosis. 2009;205(2):620–5. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhao M, Chen X. Effect of lipopolysaccharides on adipogenic potential and premature senescence of adipocyte progenitors. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2015;309(4):E334–E44. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00601.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wong JYY, De Vivo I, Lin X, Fang SC, Christiani DC. The relationship between inflammatory biomarkers and telomere length in an occupational prospective cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(1):e87348. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cassidy A, De Vivo I, Liu Y, Han JL, Prescott J, et al. Associations between diet, lifestyle factors, and telomere length in women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91(5):1273–80. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Perera T, Young MR, Zhang Z, Murphy G, Colburn NH, et al. Identification and monitoring of metabolite markers of dry bean consumption in parallel human and mouse studies. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2015;59(4):795–806. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201400847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]