SUMMARY

The ribosome is a complex macromolecular machine and serves as an ideal system for understanding biological macromolecular assembly. Direct observation of ribosome assembly in vivo is difficult, as few intermediates have been isolated and thoroughly characterized. Herein, we deploy a genetic system to starve cells of an essential ribosomal protein, which results in the accumulation of assembly intermediates that are competent for maturation. Quantitative mass spectrometry and single-particle cryo-electron microscopy reveal 13 distinct intermediates, which were each resolved to ~4–5Å resolution and could be placed in an assembly pathway. We find that ribosome biogenesis is a parallel process, that blocks of structured rRNA and proteins assemble cooperatively, and that the entire process is dynamic and can be ‘re-routed’ through different pathways as needed. This work reveals the complex landscape of ribosome assembly in vivo and provides the requisite tools to characterize additional assembly pathways for ribosomes and other macromolecular machines.

Keywords: Ribosome assembly, 50S subunit, macromolecular assembly, RNA folding, quantitative mass spectrometry, cryo-electron microscopy

INTRODUCTION

Macromolecular complex assembly involves the synthesis and assembly of defined sets of proteins, RNAs, lipids and other ligands into a functional superstructure, and understanding the underlying principles of this process remains a significant challenge. Indeed, molecular structures of individual components or complete assemblages are inadequate to infer the preferred in vivo assembly pathway. In addition, it is difficult to determine whether assembly proceeds in an obligate linear fashion or is parallel and flexibly allows for incorporation of elements in an arbitrary order.

The ribosome, which is responsible for protein synthesis in all living organisms, is a complex composite of RNA and protein and, due to the metabolic load associated with ribosome biogenesis, its assembly is under strong selective pressure for efficiency and precision. In bacteria, the primary ~5 kb transcript is cleaved into 3 component rRNAs, undergoes extensive post-transcriptional modification, and folds into ~150 helices that form ~600 precise tertiary RNA contacts (Petrov et al., 2014). The rRNA processing and folding occurs co-transcriptionally, along with the translation, modification, folding, and binding of ~50 ribosomal proteins, and the entire process is facilitated by the chaperoning activity of ~100 ribosome biogenesis assembly factors and rRNA and r-protein modification enzymes (Shajani et al., 2011). The mature 70S ribosome (Ban et al., 2000), is composed of a small subunit (30S, SSU) and a large subunit (50S, LSU) that essentially assemble independently. Despite this incredible complexity, the bacterial ribosome assembles in ~2 min, with each cell generating ~100,000 ribosomes per hour (Chen et al., 2012). As a result, ribosome assembly intermediates are extremely short-lived and difficult to isolate or characterize directly under rapid growth conditions.

To enrich for intermediates, ribosome assembly can be stalled either genetically (Shajani et al., 2011) or chemically (Stokes et al., 2014) and biochemical and structural characterization of these incomplete particles provides insights into the nature of the putative intermediates in the assembly pathway upstream of the block. As applied to the SSU (Sashital et al., 2014; Sykes and Williamson, 2009) this approach has led to a basic model where rRNA folding and r-protein binding begins at the 5′ end of the transcript and proceeds to the 3′ end.

Compared to the SSU, little is known of LSU assembly in vivo, due to the LSU’s greater complexity, a greater reliance on assembly factors, and more intricately folded rRNA. Many of the LSU precursor particles isolated to date are largely homogeneous or consist of closely related structures in the final stages of assembly (Jomaa et al., 2013; Li et al., 2013a; Ni et al., 2016). Our understanding of early LSU assembly intermediates is primarily derived from pioneering in vitro reconstitution experiments by the Nierhaus group (Herold and Nierhaus, 1987) that established hierarchical assembly of the 50S subunit with strong thermodynamic cooperativity observed between many of the r-proteins. By withholding sets of r-proteins from the reconstitution reactions, this work revealed the presence of primary proteins, which could bind rRNA independently, and secondary and tertiary proteins, which exhibited improved binding in the presence of primary and secondary proteins, respectively. These distinct classes were consistent with a hierarchical assembly model containing both sequential and parallel pathways, and this model has been critical to our understanding of ribosome biogenesis in vitro.

There are significant differences between ribosome assembly in vivo and in vitro (Shajani et al., 2011), and to better understand the pathways in vivo, we developed a genetic system to deplete a particular ribosomal protein in growing cells, in analogy to omission of an r-protein in the Nierhaus in vitro reconstitution studies. The conserved and essential protein bL17 was chosen for limitation due to its weak primary binding to rRNA and its binding potentiation of a set of other r-proteins in vitro (Herold and Nierhaus, 1987).

Here, we show that limitation of bL17 expression results in the accumulation of a series of incomplete LSU particles, which we establish are competent for maturation using pulse-labeling quantitative mass spectrometry (PL-qMS). We characterize the rRNA conformation of these particles using chemical probing, their composition using qMS, and determine the structures of 13 distinct LSU intermediates to ~4–5 Å resolution using single-particle cryo-EM (cryo-EM). Unlike prior structural work on the SSU (Mulder et al., 2010; Sashital et al., 2014), the resolution obtained herein allowed for detailed annotation of r-protein and rRNA helix occupancy across the different structures populated in vivo. Using these data, we propose that assembly is highly flexible, taking advantage of multiple accessible pathways to complete assembly when a component is limiting. Notably, progression along these pathways relies on incorporation of cooperative ‘blocks’ of rRNA and bound proteins.

RESULTS

A genetic system to perturb ribosome biogenesis

The r-protein limitation system was designed to minimally perturb the host chromosome, provide titratable control of the level of the r-protein of interest, and to ensure a homogeneous response of the entire population of cells to the limitation. Thus, the chromosomal copy of the rplQ gene encoding bL17 was replaced with a cassette (Shoji et al., 2011) intended to minimally disrupt expression of the α-operon, rpsM-rpsK-rpsD-rpoA-rplQ, using site-specific recombineering (Datsenko and Wanner, 2000), and this strain was complemented with a plasmid bearing a bL17 expression construct under control of the small molecule N-(β-Ketocaproyl)-L-homoserine lactone (HSL) (Canton et al., 2008) (Fig. 1A). The response of a plasmid-borne GFP reporter to the inducer could be accurately titrated without major effects to cellular growth rate (Fig. 1B) and, critically, in distinction to lac-based (Novick and Weiner, 1957) or ara-based (Siegele and Hu, 1997) induction systems, the population of cells responded homogenously (Fig. S1A). Titration with HSL induced and eventually saturated GFP expression, with an expression midpoint at 0.3 nM HSL (Fig. S1B). Unlike the GFP control strain, the cellular growth rate of the bL17-limitation strain strongly correlated to the level of bL17 produced, consistent with its essential function (Fig. 1B, C) and thereby demonstrating controlled expression of an essential ribosomal protein.

Figure 1.

Cellular response to an r-protein limitation. (A) Schematic for the genetic system to regulate the production of bL17. The rplQ gene encoding bL17 (dotted) was replaced with a chloramphenicol resistance gene (camR, bold) using site-specific recombineering. The strain was complemented with a plasmid-borne HSL-inducible copy of rplQ (top). Proteins, coding sequences, and promoters are marked with ovals, rectangles, and arrows respectively. Ribosomal genes and proteins are colored red. (B) Growth rate of bL17-titrated (JD321, black circles) and GFP-titrated control (JD270, gray triangles) strains as a function of the HSL inducer concentration. Restrictive (0.1 nM) and permissive (2.0 nM) HSL concentrations used subsequently are noted with vertical red and green dotted lines, respectively. (C) Ribosomal protein and (D) assembly factor or chaperone protein levels as measured by qMS as a function of HSL inducer concentration in bL17-limitation (JD321, dark circles) and control (JD270, light triangles) strains. Traces for ribosomal proteins, assembly factors, and chaperones are colored red, blue, and green, respectively.

Ribosome assembly factors are upregulated in response to depletion of bL17

To understand the response to an r-protein limitation, the JD321 depletion strain (E. coli NCM3722 rplQ::cat, pHSL-rplQ) was grown with differing levels of HSL, and the whole cell protein composition was determined using qMS. Wild-type control cells (JD270; E. coli NCM3722 pHSL-GFP) in which HSL was used to vary the levels of GFP were also analyzed to identify any proteome changes that were HSL-dependent but bL17-independent. More than 900 proteins (~3600 peptides) were measured relative to a fixed 15N-labeled reference standard using a SWATH MS2 quantitation strategy (Gillet et al., 2012). In addition to bL17, the cellular levels of ribosomal proteins bL32 and bL35 were strongly dependent on HSL, consistent with a downregulation of these proteins as the cells were starved for bL17. Most other ribosomal proteins exhibited small, but consistently elevated levels in response to bL17 depletion (Fig. 1C, S1D). Inspection of ribosome associated protein levels revealed upregulation of assembly factors SrmB, DeaD, Obg, RluB, YjgA, and the RNA chaperone CspA, consistent with a cellular response to the induced dysregulation of ribosome biogenesis. Notably, the abundance of multiple protein chaperones, including GroEL, decreased with bL17 depletion (Fig. 1D, S1E). Additionally, depletion of bL17 resulted in a dramatic increase in the cellular RNA/protein ratio (Fig. S1C), consistent with upregulation of rRNA synthesis in a similar manner to that observed with ribosome poisons such as chloramphenicol (Scott et al., 2010). Taken together, these data supported a model in which bL17 depletion decreases the cell’s translational capacity, resulting in a reduction of the cell’s growth rate and need for protein chaperones. In addition, the cell upregulates rRNA synthesis, the expression of ribosomal proteins and some associated ribosome assembly co-factors.

Depletion of bL17 perturbs formation or maintenance of mature ribosomes

Looking more closely at ribosome assembly intermediates, the bL17 depletion strain was grown with either 0.1 or 2.0 nM HSL as restrictive or permissive conditions, respectively. Cells were harvested at mid-log phase and ribosomal particles were analyzed using sucrose gradient ultracentrifugation (Fig. 2A). The restrictive conditions resulted in a clear decrease of 70S particles, with a concomitant increase in 30S particles. A pronounced new peak accumulated in the gradient at ~40S, and, based on the presence of the large subunit (LSU) 23S rRNA, this peak is referred to as LSUbL17dep.

Figure 2.

LSUbL17dep particles are maturation-competent assembly intermediates. (A) Sucrose density gradient profiles of JD321 cell lysates grown under restrictive (black) or permissive (gray) conditions. Absorbance at 260 nm, which largely corresponds to rRNA is plotted, and LSUbL17dep (red), 50S (purple), 30S, and 70S/polysome peaks are marked with vertical dashed lines. (B) Time-course of sucrose density gradient profiles for JD321 cells grown under restrictive conditions after pulsing to permissive conditions. The center of mass for the LSU is noted by the colored dashed lines for each timepoint harvested pre-, and post-pulse. 30S, 70S/polysome, and the bottom of the gradient are marked with black dashed lines. (C) Representative mass spectra for a bL17 peptide (VVEPLITLAK [47–56]; left) or a bL20 peptide (ILADIAVFDK [94–103]; right) isolated from the 70S fraction post-pulse/bL17-induction as a function of time. Intensities normalized to that of the 14N monoisotopic peak. Colors correspond to timepoints in (B). (D) Quantitation of pulsed-isotope label as a function of time post-pulse/bL17 induction. Median peptide value for bL17 (red), and the median LSU (black) or SSU (gray) proteins isolated from 70S particles are plotted at each timepoint. (E) Representative 70S particle pulse labeling kinetics from cells grown under steady-state bL17-limited conditions (0.3 nM HSL). Maximum labeling rate at this cellular growth rate of λ = 0.007 min−1 noted as max lab (dotted gray), and highlighted by bS21 (red), which is known to exchange and will thus label at approximately the growth rate. Kinetic traces were fit as described previously (Chen et al., 2012) resulting in a relative precursor pool size P, which was large for most LSU proteins and consistent with maturation-competent intermediates, as demonstrated by the delayed labeling of representative LSU protein, bL20 (blue).

The LSUbL17dep assembly intermediates are competent for maturation

The LSUbL17dep peak could correspond to degradation products, dead-end assembly products, or intermediates that are competent to mature into 50S subunits. L17-induction-pulse and steady state pulse-labeling (Chen et al., 2012; Jomaa et al., 2013) experiments were carried out to discriminate among these possibilities.

To chase the LSUbL17dep into 70S ribosomes, an induction-pulse experiment was performed where bL17-limited cells were simultaneously induced to a level of permissive bL17 expression and pulsed with an isotope label. The growth rate increased from 150 mins/doubling pre-pulse to 65 mins/doubling post-pulse, after a ~15–30 minute lag (Fig. S2A) accompanied by a gradual disappearance of LSUbL17dep and a concomitant appearance of new 50S and 70S/polysome particles (Fig. 2B). These changes outpaced simple dilution from growth, and all of the LSU particles migrated at 50S/70S/polysome within one cell doubling period. To determine whether the new 70S particles arose from pre-existing LSUbL17dep particles or were synthesized de-novo post-pulse, label incorporation into the 70S particle was monitored over time on a protein-by-protein basis (Fig. 2C). Consistent with the newly formed 70S particles arising from the pre-existing pool of LSUbL17dep particles, significant quantities of pre-pulse isotope-labeled proteins were observed in the 70S peak for the vast majority of both the LSU and SSU proteins (Fig. 2C). In contrast, rapid accumulation of post-pulse labeled bL17 protein was observed within the 70S peak, consistent with the majority of bL17 synthesis taking place after the induction and isotope pulse (Fig. 2C, D). Pre-existing LSUbL17dep intermediates are thus competent for rapid maturation and join with 30S subunits to form 70S particles and polysomes.

To determine if the LSUbL17dep particle was competent for maturation under steady state bL17-limiting conditions, cells were grown under bL17-restrictive conditions to mid-log phase, pulsed with isotopically-labeled media, and mature 70S particles were isolated and analyzed via mass spectrometry to measure isotope label incorporation as a function of time. For most r-proteins, a clear lag was observed in the kinetics of 70S ribosome labeling relative to the cellular growth rate (Fig. 2E), consistent with a model in which the LSUbL17dep particle is part of the 70S precursor pool (Jomaa et al., 2013). As a control, bS21 labeling was monitored because this protein is known to exchange and label at the cellular growth rate irrespective of the precursor pool size (Chen et al., 2012), and the bS21 labeling was clearly distinct from that of other r-proteins (Fig. 2E). Fitting the bL20 labeling data to a quantitative model (Chen et al., 2012) revealed a precursor pool size of 1.9 relative to 70S ribosomes, suggesting that the majority of the LSUbL17dep particles were competent for maturation. Taken together, these experiments indicated that the LSUbL17dep particle could rapidly mature upon addition of bL17 and, further, that when limited for bL17, this particle underwent maturation but did so more slowly than under the permissive conditions.

LSUbL17dep particles bear incompletely processed rRNA

In bacteria, rRNA processing occurs during assembly and has been used as a marker of particle maturity (Stokes et al., 2014; Thurlow et al., 2016). To assess the rRNA processing status in the LSUbL17dep intermediates, next-generation sequencing libraries were generated from LSU intermediates and 70S particles isolated from either bL17-limited or wild-type cells (see Methods), and the ratio of sequencing reads corresponding to immature vs. mature rRNA was calculated for each sample at either the 5′ or 3′ termini. LSUbL17dep particles bore ~4-fold more incompletely processed 23S rRNA than 70S particles isolated from wild-type cells (Fig. S2B, C), consistent with a bL17-depletion induced processing defect. Additional processing occurred as the LSUbL17dep intermediates matured to 70S particles, as evidenced by the lower levels of unprocessed rRNA. The fact that the LSUbL17dep particles were under-processed relative to their 70S counterparts firmly placed LSUbL17dep upstream of the 70S. Notably, incomplete rRNA processing was observed even in the 70S particles isolated under bL17-limited conditions.

Depletion of bL17 reorders r-protein binding and particle assembly

To determine how loss of an essential, early binding r-protein like bL17 impacts ribosome assembly, the protein composition of particles accumulated during bL17 limitation was analyzed. Ribosomal particles from cells grown under either bL17-restrictive or permissive conditions were fractionated on a sucrose gradient, and the r-protein occupancy relative to a mature 70S particle was determined using qMS. After hierarchical clustering, proteins were assigned to four groups based on their binding profile, with groups I-IV exhibiting progressively delayed binding (Fig. 3A). The fact that group IV proteins were completely missing from the LSUbL17dep peak suggested that the binding of these proteins was dependent, directly or indirectly, on bL17, whereas the stoiochiometric binding of group I demonstrated that much of the protein binding in LSU assembly proceeded independently of bL17. Additionally, the partial occupancy observed for group II and III proteins through the 40S region of the gradient indicated that these fractions consisted of a heterogeneous mixture of particles in various stages of assembly. Finally, full occupancy of all r-proteins was observed in the 70S and polysome fractions, indicating that protein bL17 is fully bound in large subunit particles undergoing active translation (Fig. 3A, S3B), and these 70S particles were indistinguishable from those assembled under the permissive conditions. The LSUbL17dep occupancy patterns were absent in gradients analyzed from isogenic cells grown under permissive conditions (Fig. S3A).

Figure 3.

R-protein binding is re-routed upon bL17 depletion. (A) Heat map of LSU protein abundance relative to a purified 70S particle across a sucrose gradient purified from bL17-limited cells (JD321, 0.1 nM HSL). Occupancy patterns were hierarchically clustered to reveal 4 binding groups, which are marked with proteins labels from earliest (green, I) to latest binding (bold, red, IV). The trace of the sucrose density gradient analyzed is depicted above. (B) Re-routed Nierhaus assembly map. Proteins are located on the map according to the binding order defined by Chen et al. from earliest (top) to latest (bottom), and these binding groups are colored at the right side of the map (blue to red). In vitro protein binding cooperativities measured by the Nierhaus group are depicted with thick black (strong cooperativity), or thin gray (weak cooperativity) lines. Interactions that are dispensable for binding in vivo are highlighted purple, whereas those confirmed are colored red. Thick dashed orange lines mark newly measured binding dependencies that are absent from the in vitro map. The assembly map is colored according to the protein binding groups in (A), and bL17 is marked with italics.

In comparing this dataset to the wild-type r-protein binding previously determined (Chen and Williamson, 2013), some late-binding proteins were present in the LSUbL17dep particles (e.g. bL12, bL31), while other middle-binding proteins were absent (e.g. bL32). Indeed, coloring the Nierhaus assembly map by these groups (Fig. 3B) revealed proteins whose in vivo binding was dependent on bL17, and, furthermore, illustrated a strong reordering of the r-protein binding. This effect was also observed in comparing the r-protein occupancy of a single sucrose gradient fraction isolated either from WT or bL17-restricted cells (Fig. S3B). Additionally, the depletion approach allowed for the refinement of the Nierhaus assembly map under in vivo conditions, eliminating some predicted dependencies (blue arrows) and revealing novel direct or indirect binding requirements (red/orange dashed arrows).

The abundance of known ribosome assembly factors was measured through the gradient using qMS, revealing that fractions bearing the LSUbL17dep were strongly enriched for the known assembly co-factors, DeaD, YjgA, RluB, RhlE, and YhbY (Fig. S3C). We hypothesized that this specific set of factors, which was not enriched in the LSU fractions purified from cells grown under permissive conditions, was likely acting to aid in the assembly of the LSUbL17dep particles and remained associated with the particles due to the bL17-limitation induced assembly delay.

Native rRNA secondary structure is present in LSUbL17dep particles

To assess the status of rRNA folding in the LSUbL17dep particles, sequencing-based RNA chemical probing experiments were performed using the SHAPE-MaP approach (Siegfried et al., 2014). This method was applied to LSUbL17dep particles, 70S particles from wild-type cells, and protein-free rRNA, and, for each particle, a by-residue SHAPE modification value (SRparticle) was calculated to identify highly reactive residues (see Methods). SHAPE probing of the free 23S rRNA revealed that most residues were unreactive, with highly reactive residues found predominantly in loops and other unpaired structures, similar to that reported previously (Siegfried et al., 2014) (Fig. S3D). Calculation of SRbL17 – SR70SWT revealed that for most residues, the 70SWT and LSUbL17dep reactivity profiles were similar (Fig. S3E), suggesting that the vast majority of rRNA secondary structure was formed in the LSUbL17dep particle and is thus formed largely independent of bL17 association. Notably, significant reactivity differences were found near the rRNA termini, likely related to incomplete rRNA processing. More subtle effects were found in portions of the bL17 binding site and the peptidyl transferase center, consistent with altered local structure in these regions.

The LSUbL17dep peak is a heterogeneous ensemble of assembly intermediates

The LSUbL17dep particle bore differing sub-stoichiometric r-protein quantities, suggesting a heterogeneous population of co-purified particles whose average r-protein occupancy was measured by qMS. To determine the structure and composition of the underlying discrete assembly intermediates, we employed single-particle cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM). Briefly, the LSUbL17dep was isolated via sucrose gradient centrifugation, spin-concentrated, and vitrified over holey gold grids, and a cryo-EM dataset of the heterogeneous assembly mixture was collected. Notably, the spin-concentration had no effect on the ensemble r-protein occupancy, as measured by qMS (Fig. S3B).

Individual particles were subjected to an initial round of 3D classification and reconstruction, resulting in 6 different structural super-classes (A–F) ranging in average resolution between 3.7 and 7.9 Å (Table S1; Fig. 4A, S4B). Super-class A resembled a 70S particle missing protein components, and super-class F corresponded to an intact 30S subunit at intermediate resolution. The 30S particle was expected as a tail in the gradient, but the significance of the quasi-70S particle is unclear, and neither super-class A nor F was considered further. A second round of sub-classification and refinement of super-classes C, D, and E, resulted in a set of 12 sub-class LSUbL17dep EM density maps at average resolutions of ~4–5 Å. Further classification of these sub-classes or of super-class B did not reveal discernable differences among the resulting maps; however, the presence of residual heterogeneity in these classes could not be excluded.

Figure 4.

Cryo-EM 3D classification and refinement of LSUbL17dep particles. (A) Particles were classified and refined using a hierarchical scheme (Methods). Annotations indicate number of particles used at each stage of refinement and global map resolution (Res) of the resulting class. Super-classes (A–F), and sub-classes (C1–E5), which resulted from a second round of classification and refinement are depicted. (B) Side, front, and top views highlighting EM density missing from each super-class relative to a native 50S subunit. The latter is depicted as EM density using the LSU model from a mature ribosome (PDB: 4ybb). Structures are aligned relative to one another, allowing for direct comparison within each view, as guided by dotted lines.

This 3D classification approach effectively resolved most of the sample heterogeneity, as demonstrated by the 13 disparate maps and utilized ~80% of identifiable ribosomal particles, indicating that the majority of the underlying structures could be characterized. The maps revealed structures that varied from ~50% of the expected LSU density missing, to those that closely resembled fully mature LSUs. Interestingly, density for the solvent side of the LSU was present in all classes, whereas the central protuberance (CP), the inter-subunit interface, and base of the particle were lacking density to varying degrees among the observed classes, and these differences largely distinguished the super-classes B, C, D, E (Fig. 4B). In particular, Class B lacked extensive swaths of density in these regions and represents the least mature LSU intermediate structurally characterized to date. Superclass C bore additional density at the base of the particle, whereas superclass D was defined by the presence of the CP, but lacked significant density at the subunit interface along the particle’s midline, as well as the base of the particle. Finally, superclass E was notable for the presence of density for both the CP and the base of the particle and a variable amount of resolved density in the uL1 and uL10/11 stalks as well as the subunit interface.

rRNA and r-protein occupancy across the set of cryo-EM maps reveals distinct structures

In each class, most of the observed density could be accounted for using rigid body docking of a mature LSU (PDB: 4ybb). Although the bL17 binding site is apparently formed in all classes (Fig. 5A), regions lacking density are distributed over the entire inter-subunit interface, demonstrating wide-ranging effects of bL17 depletion. To facilitate quantitative comparison of the density among the 13 classes, the mature 50S structure was segmented into 109 rRNA helices and 30 r-proteins, and the fractional occupancy of each element was calculated for each class, as described in Methods (Fig. S6A). Numerous regions of rRNA structure were missing from the maps of most classes, and, given the formation of native secondary structure as measured by SHAPE-MaP, these helices were assumed to be folded but undocked, and thus sampling a variety of conformations within a given class. The EM density occupancy values for the ribosomal proteins were largely correlated with aggregate protein abundance levels measured by qMS (Fig. S6B), and the strongly uncorrelated proteins (bL9, uL10, uL11) were localized to the flexible LSU arms (Fig. S6C). Overall, the qMS results, which measure the average protein occupancy across all underlying structures irrespective of flexibility or orientation, were consistent with the occupancy results based on individual single-particle cryo-EM reconstructions that allow for a structure-by-structure assessment of proteins bound in their native conformation.

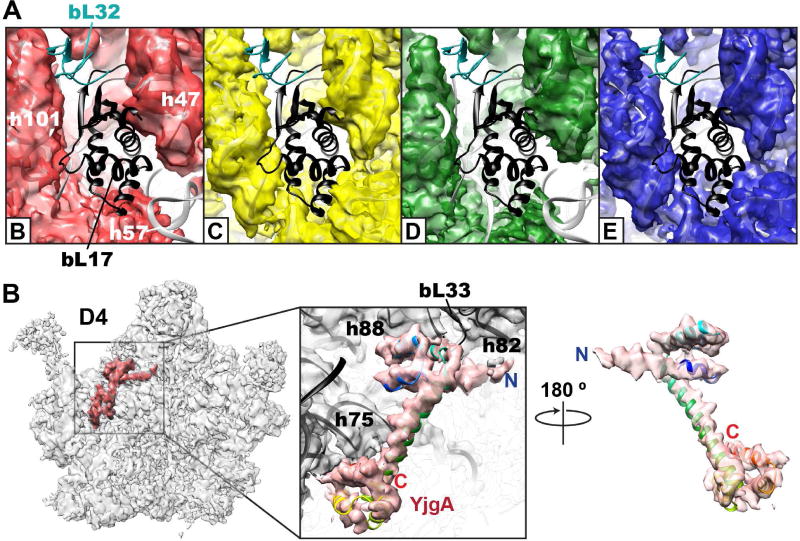

Figure 5.

Reconstructed maps of bL17-limited assembly intermediates. (A) A detailed view of the bL17 binding site. Each superclass (B,C,D,E) is shown as a colored semi-transparent surface using the color scheme in Figure 4. The docked 4ybb structure is shown as a gray cartoon model with bL17 and bL32 highlighted in black and cyan, respectively. (B) YjgA bound to the D4 intermediate. Two views of a homology model for the ribosomal cofactor YjgA (rainbow) docked into segmented density (red). Model was calculated using PDB model 2p0t as the seed on the SWISS-MODEL server. YjgA bears an N-terminal extension relative to the seed model. Proximal LSU elements noted.

Assembly factor YjgA is bound to a subset of the bL17-independent intermediates

Analyses of whole cell lysates (Fig. S1E) and purified particles (Fig. S3C) by qMS suggested that ribosome assembly in bL17-limited cells is, at least in part, reliant on assembly co-factors. Interestingly, a pronounced and well-ordered region of electron density was observed in class D4 that could be assigned as the putative assembly factor YjgA (Fig. 5B) (Jiang et al., 2006), which was upregulated upon bL17-limitation and was strongly enriched in the LSUbL17dep particles. Further global classification of each sub-class clearly revealed partial YjgA occupancy in classes D3 and E3 (~30%) and full occupancy in class D4.

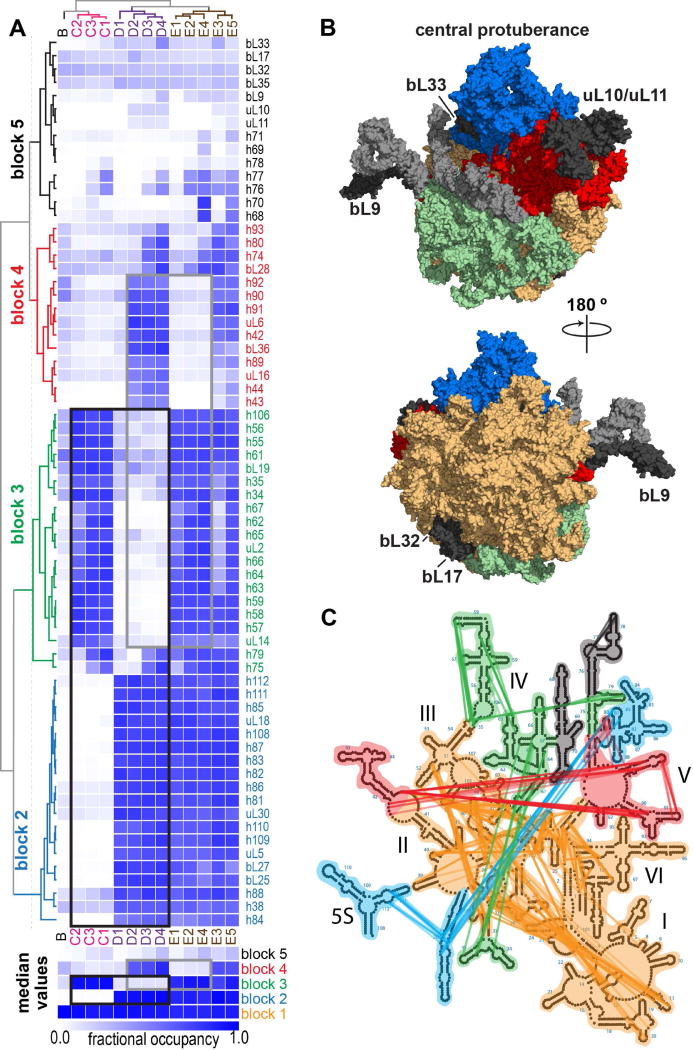

Large subunit assembly proceeds through ‘limited’ parallel pathways

Using the occupancy assignments calculated above, the set of structures resulting from EM refinement could be grouped into families of related structures. The quantitative assignment of the fraction of rRNA and proteins in their native conformation for each of the 13 structures allowed for a direct comparison of the ‘maturity’ between each of the classes. As shown in Figure 6A, hierarchical clustering of protein and rRNA helix occupancies identified groups of elements that formed a basis set for the structural differences, and grouped the structures according to common elements. The observed EM class groupings were completely consistent with the 3D classification of single-particle images, with each of the C, D, and E sub-classes grouping together. Additionally, the clustering of the rRNA and protein occupancies revealed 5 major blocks of structural elements (denoted b1–b5) that co-localized on the LSU 3D structure (Fig. 6B) and showed differential occupancy between classes. These blocks, which spanned rRNA secondary structure domains, were linked through RNA tertiary contacts (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6.

rRNA and r-protein cooperative folding blocks. (A) Hierarchically clustered heat map of calculated r-protein and rRNA helix occupancy in different intermediate structures. Values calculated as described in Methods. Blocks 1–5 with coordinated occupancy across different intermediate structures colored orange, blue, green, red, and black, respectively. This color scheme is unrelated to that in Figures 3, 4, or 5. Mutually exclusive blocks highlighted with black and gray rectangles. Occupancy heatmap for block 1 is omitted, as elements are largely present in all structures. For each block, the median occupancy value in each structure is displayed as a heat map below. (B) LSU model structure (PDB: 4ybb) with blocks colored according to (A). Block 5 rRNA helices are colored light gray, whereas block 5 proteins missing from all structures are labeled and colored dark gray. (C) 23S rRNA secondary structure map with rRNA helices colored according to blocks in (A). Colored edges represent tertiary contacts linking helices within blocks.

Critically, subtle variation within partially resolved regions distinguished the subclasses (e.g. [D1 vs D2], [E1 vs. E2]), supporting their distinct grouping by single-particle classification and leading to the hypothesis that these sub-classes were closely related assembly intermediates representing various stages of assembly progression. Indeed, comparison between classes D1–D4 revealed a monotonic increase in the total volume of the amplitude-scaled maps (Table S1), and a progression towards more native density, which was consistent with related and progressively more mature assembly intermediates.

Given the difference in the apparent maturity of the observed structures, it was logical to attempt to order them into a putative assembly pathway. By both total volume and fraction of native elements resolved, classes B and E5 represent the least and most complete structures, respectively, and they were chosen to represent the earliest and latest intermediates on a putative pathway. Since classes C and D exhibited mutually-exclusive association of blocks 2 and 3 (Fig. 6A; black box), conversion between any C class and D class would result in loss of native structure. A priori, there is no reason to believe that large amounts of native structure would be formed and lost during assembly, excluding sequential assembly of these classes, which necessarily introduces parallel branches into the general assembly mechanism. Similar mutually exclusive occupancy was found between classes D2–D4 and E1, E2, and E4 (Fig. 6A; grey box), introducing an additional branch in the pathway. Finally, occupancy in the C classes was largely a subset of that in the E classes, allowing for conversion of each C class to a cognate E class without the loss of native structure.

Using this information, the classes were assigned an assembly order beginning with the least mature map B and ending in the most mature map E5. For each transition, the number of new structural elements that were formed versus those that were lost were calculated, and the structures were ordered to minimize the number of elements lost during the transitions, to minimize the number of required parallel pathways, to minimize the number of classes that could not transition to the terminal E5 class, and to embody a principle of parsimony in the connections depicted (Fig. 7, S7A–D). This resulted in three parallel routes of assembly that consist of either the C classes, D classes (with E3) or E classes (without E3). This putative assembly pathway represents the first attempt at an assembly map for the 50S subunit with discrete RNA structural transitions.

Figure 7.

Parallel bL17-independent ribosome assembly pathways. Putative assembly paths from the least mature B class (top) to the most mature E5 class (bottom). Arrows mark allowed transitions, red lines highlight unfavorable transitions. Unresolved structure is highlighted yellow. Resolved elements are colored by block number as in Figure 6, and element formation is noted with *. Protein binding is shown at each transition. YjgA (black) occupancy percentage is indicated, as calculated by sub-classification in classes D3, D4, E3.

DISCUSSION

Ribosome biogenesis utilizes ‘limited parallel processing’ with ‘block’ assembly

The hybrid biochemical and structural approach to monitor macromolecular assembly described herein reveals several notable features of ribosome biogenesis process. First, assembly is highly flexible, and can be ‘re-routed’ and allowed to progress even in the absence of the early-binding protein, bL17. The existence of such parallel pathways may ensure that blockage of an assembly pathway, for example due to transient shortages in r-protein availability or rRNA misfolding, results in diversion of ribosome biogenesis flux to alternative pathways until the bottleneck can be relieved. Notably, some components of the 50S subunit are dependent on bL17, including other ribosomal proteins (i.e. bL28, bL32, bL33, bL35) and intersubunit rRNA bridges (e.g. h69, h71). These structures must form downstream of the most mature E5 intermediate class, and their assembly may be rate-limiting for overall ribosome biogenesis under the bL17-depletion condition. The fact that proteins ‘downstream’ of bL17 are missing implies that assembly is hierarchical in some regards. However, the presence of very mature rRNA structure and late-binding proteins in the bL17-deficient particles also demonstrates that assembly occurs in parallel, and that many portions of the particle can assembly independently. This behavior is denoted as ‘limited parallel processing’ and it has the benefit of affording the maximal flexibility given the thermodynamic constraints of cooperative rRNA folding and r-protein binding.

Second, the hierarchical clustering approach revealed groups of elements with highly correlated behavior across the intermediate structures suggesting that large ‘blocks’ of structure mature in concert as cooperative folding blocks (Fig. 6). Notably, these blocks span multiple rRNA secondary structure domains, which are connected through RNA tertiary contacts (Fig. 6C) and co-localized on the mature 50S tertiary structure (Fig. 6B). For example, block 1, which was present in all structures, consisted exclusively of elements found on the solvent face of the subunit, consistent with this region maturing early during the assembly pathway. The proteins found in block 1 include all of the ‘early-group’ primary binding proteins as defined by Chen et al. (with the exception of bL17), and the majority (9/11) of these proteins are defined as primary binding proteins in the in vitro assembly map (Herold and Nierhaus, 1987). These proteins are likely the first bound to 23S rRNA and can each bind independently of bL17. Notably, not all primary binding proteins are in this group, indicating that, in vivo, some proteins require additional components or specific conformations for rapid binding (e.g. uL16 and bL28). Finally, specific disruption of the bL17 binding site results in significant long-range structural defects, such as those observed at the peptidyl transferase center (PTC) (Fig. S5B), which is located ~90 Å away. This observation provides strong support for the existence of long-range allosteric connections in the ribosome that are important for assembly, just as they are crucial for the process of translation.

Block assembly reveals critical and dispensable tertiary rRNA folding contacts

Recognition of these independently-maturing blocks allowed for identification of tertiary rRNA contacts that span between distinct blocks (Fig. S6D), and therefore must be dispensable for folding of at least one of the individual blocks. In some instances, these contacts bridged blocks that exhibit mutually exclusive occupancy between classes, implying that the bridging contact is dispensable for the folding of both blocks (e.g. green/red lines connecting blocks 3 and 4). In other cases, contacts were observed that bridged between one occupied and one unoccupied block (e.g. orange lines emanating from block 1). These contacts must be dispensable for folding of the occupied block but may be important in the folding of the unoccupied block. Identification of which tertiary contacts are within a folding block and which are between folding blocks is impossible from inspection of either the secondary or tertiary structures of the mature 50S subunit and could only be identified by comparison of the set of newly determined assembly intermediate structures.

The existence of as-yet-unresolved bL17-dependent pathways

The bL17-independent assembly pathways describe formation of nearly 50% of the particle, but are reliant on addition incorporation of bL17 and bL17-dependent proteins downstream of class E5. Notably, based on the median r-protein pool size for intermediates, P = 0.91, the estimated assembly time through the bL17-independent pathways is ~46 mins (Chen et al., 2012), which is ~20-fold slower than under bL17-permissive conditions. This delay could result from slow assembly along the described pathways or from delayed assembly downstream of class E5 as a result of bL17-limitation. This result, and the fact that bL17 is normally an early-binding protein suggests that significant assembly flux progresses through as-yet-unobserved bL17-dependent assembly pathways under optimal growth conditions. Slow but viable assembly pathways, such as those described herein, may exist to allow the cell to cope with ribosome assembly stress brought on by diverse challenges encountered in the wild, such as non-optimal media, temperature, or transient fluctuations in r-proteins and assembly co-factor availability.

Extension of the Nierhaus large subunit assembly map in vivo

The structural analysis described here allows an extension of the Nierhaus in vitro assembly map to include the coordinated docking of rRNA helices that accompany binding of r-proteins during assembly in cells. The strong correlation in occupancy between sets of RNA helices and r-proteins in the set of 13 EM maps is consistent with positively cooperative interactions in discrete folding blocks. Using this information, the protein assembly map can be updated to reflect the observed assembly blocks, which include both proteins and rRNA helices (Fig. S7E–G). Moreover, this information can be used to prune the Nierhaus map of apparent r-protein binding dependencies that are not strictly necessary in vivo (Fig. S7E–G, pink arrows). It should be noted that these data simply show binding of these proteins is possible in the absence of the upstream partner and does not rule out the possibility that binding would be improved were its partner present. Taken together, this work provides a structural basis for the r-protein binding cooperativity initially observed by the Nierhaus group and provides insight into how folding of blocks of rRNA structure are coupled to r-protein binding.

The role of assembly factors in a parallel assembly pathway

In bacteria, many assembly co-factors are nonessential despite their role in facilitating maturation of the essential ribosome. The parallel pathways revealed herein may help to explain this apparent contradiction, as any given assembly pathway may only require a small subset factors. These parallel pathways provide a level of redundancy such that if a given pathway is blocked by deletion of a factor, greater flux can be shifted to alternative, albeit inherently less efficient pathways. Indeed, nonessential biogenesis co-factors may confer selective advantage by chaperoning a subset of more efficient folding pathways whereas essential co-factors may facilitate passage through key points of pathway constriction, where inefficiencies in assembly cannot be readily parallelized. Notably, we observe significant occupancy of the putative assembly co-factor YjgA only in a subset of the structures along the D pathway, suggesting that YjgA acts at a late stage of biogenesis and is stably bound exclusively to D-pathway intermediates. Additionally, we find that YjgA occupancy is mutually exclusive with a properly docked helix 68, which is one of the last rRNA elements to mature and forms critical inter-subunit bridges. This finding suggests that YjgA dissociation may act as a signal in the late stages of particle maturation, releasing the mature LSU to bind SSU particles.

Post-translational regulation of ribosomal protein levels

A subset of proteins (bL32, bL33, bL35) with low abundance in the LSUbL17dep particles were also depleted in whole cell lysates (Fig. S3B, S1D) implying that free, unincorporated copies of these proteins do not accumulate as would be expected from stoichiometric r-protein expression. Instead, either their synthesis or degradation must be tightly regulated under the restrictive conditions. To distinguish between these possibilities, bL17-limited cells were pulse-labeled under steady-state conditions, which revealed significantly slower synthesis of bL32 and bL35 relative to other r-proteins (Fig. S2D). In contrast, the synthesis of bL33 was rapid relative to the median LSU r-proteins, and degradation was observed (Fig. S2E). Interestingly, both bL32 and bL35 are transcribed using dedicated promoters, whereas bL33 is co-transcribed with bL28, suggesting that the synthesis of bL32 and bL35 is independently downregulated during restrictive conditions whereas the degradation of bL33 is upregulated to produce the appropriate r-protein levels.

The role of CP docking in large subunit biogenesis

The observed parallel assembly pathways diverged based in part on the presence or absence of the CP, with the C classes all lacking properly localized CP density. Interestingly, the relatively mature C1 class bore significant density resembling the CP, however it was rotated and docked adjacent to the uL1 stalk, resulting in a lack of native density for the CP rRNA (5S, helices 82–87), and helices 38 and 68 (Fig. S5C). This apparent rotation was not an artifact of errant rigid body docking as the peptide exit tunnel was observed in the expected location (Fig. S5A) and 2D class averages exhibited pronounced CP density in this rotated conformation (Fig. S5D). Interestingly, this orientation was reminiscent of that observed previously (Leidig et al., 2014) in eukaryotic pre-60S particles and may represent a common rRNA misfolding trap that spans the pro- and eukaryotic kingdoms. According to our proposed assembly pathway, this kinetic trap is overcome as the C1 class matures to the E2 class, resulting in a properly docked CP relatively late in assembly. In contrast, a properly docked CP is observed in the very immature D1 class, which is significantly less mature than class C1. This result argues that the CP can properly dock even in relatively immature intermediates such as D1 and suggests that this nonnative conformation is either nonobligatory or is populated very transiently in the B-to-D1 transition. While class D1 was generally less mature than C1, it did bear properly docked helices 38 and 81–88 whereas class C1 did not. This result is consistent with previous data reviewed in (Dontsova and Dinman, 2005) implicating these helices in cooperative docking of the 5S rRNA into the CP.

An evolving assembly pathway

A principle tenet of the RNA-world hypothesis is the existence of a primordial RNA-only ribosome bearing a functional peptidyl transferase center (PTC). Indeed, an elegant analysis of structural motifs found in modern ribosomes suggested that the PTC was the first ribosome element to evolve and that additional elements of the 23S were added to this PTC throughout evolution (Bokov and Steinberg, 2009). As PTC is one of the last elements to mature during assembly of a modern ribosome (Fig. S5B), the entire order of ribosome assembly must have undergone a drastic rearrangement during evolution and suggests that our understanding of ribosome evolution may be incomplete. Interestingly, the late maturation of the PTC has been observed in the distantly related B. subtilis previously (Jomaa et al., 2013), suggesting that this late timing is a conserved feature of the modern ribosome, potentially protecting the cell from peptidyl-transferase-active, yet incompletely matured ribosomes.

Hybrid approaches to understanding macromolecular complex assembly

The putative assembly pathways enumerated herein highlight how the relative order of ribosomal structure formation can differ depending on the particular kinetic traps encountered by each particle (Fig. S7). Identification of these parallel assembly pathways was not possible using bulk measurements such as qMS or SHAPE-MaP, and required the detailed 3D classification of single-particle EM datasets. The depletion strategy outlined herein can be readily extended to target other ribosomal proteins and should help to elucidate the bL17-dependent pathways. Furthermore, analysis of the relationships of the intermediates that accumulate and the blocks of structure that form under different limitations will allow a more complete understanding of the overall pathway of biogenesis. Additionally, the experimental framework and tools described here should be readily applicable to the study of the biogenesis of other critical macromolecular complexes. Indeed, putative assembly intermediates have been identified by perturbing assembly of various macromolecular complexes including the proteasome (Tomko and Hochstrasser, 2013) and the spliceosome (Matera and Wang, 2014). The described pulse-labeling and quantitative mass spectrometry techniques should be useful in determining whether the accumulating particles are competent for maturation and in assessing the average composition of the underlying intermediates. When atomic-scale models are available for the complex of interest, our approach to determine the course-grained structure and precise protein-by-protein composition of the vast majority of the particles present in a heterogeneous sample should be of great utility in assessing the degree to which assembly is parallelized, in determining the constituents of various cooperatively folded domains, and in determining the relative abundance of assembly intermediates.

METHODS AND RESOURCES

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for reagents may be directed to, and will be fulfilled by Dr. James R. Williamson.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

E. coli strains were grown supplemented M9 media [48mM Na2HPO4, 22mM KH2PO4, 8.5mM NaCl, 10mM MgCl2, 10mM MgSO4, 5.6mM glucose, 50μM Na3·EDTA, 25mM CaCl2, 50μM FeCl3, 0.5μM ZnSO4, 0.5μM CuSO4, 0.5μM MnSO4, 0.5μM CoCl2, 0.04μM d-biotin, 0.02μM folic acid, 0.08μM vitamin B1, 0.11μM calcium pantothenate, 0.4nM vitamin B12, 0.2μM nicotinamide, 0.07μM riboflavin, and 7.6mM (14NH4)2SO4] at 37°C in culture flasks ranging in volume from 5 mL test tubes to 2 L baffled flasks. Growth media was supplemented with antibiotics and HSL as noted in the methods section.

METHOD DETAILS

Strain construction

Recombineering plasmid pJD058 was generated from pKD46 (Datsenko and Wanner, 2000) by replacing the ampicillin resistance cassette with a kanamycin resistance gene using Gibson assembly with primers JDA146–149. Strain JD189, which is wild-type K-12 E. coli strain NCM3722, was transformed with plasmid pJD058 and this strain was then transformed with pCDSSara-L17 (Shoji et al., 2011) and selected for both plasmids by growing at 30°C on LB supplemented with kanamycin (50 μg/mL), spectinomycin (100 μg/mL) and glucose (0.4%), resulting in strain JD204. Cells were then made recombinogenic by the addition of 0.2% arabinose for 1 hour before preparing cells for electroporation. A bL17 knockout cassette was generated from genomic DNA isolated from the Shoji ΔrplQ strain via PCR with primers JDA144/145 followed by gel purification. This cassette was electroporated into strain JD204, which was recovered for 2 hours at 30°C on LB supplemented with spectinomycin and 1% arabinose before plating on LB supplemented with spectinomycin, 1% arabinose, and chloramphenicol (35 μg/mL) at 37°C. Colonies were restreaked as above and eventually checked for loss of pJD058 by testing their sensitivity to kanamycin and the correct insertion of the rplQ knockout by sequencing of a PCR product covering the altered region of the genome resulting in strain JD311.

The HSL-inducible bL17 plasmid was generated by Gibson cloning of the bL17 coding sequence in place of the GFP coding sequence in part T9002, which was in the plasmid backbone pSB3T5 (www.partsregistry.org), resulting in the plasmid pJD075. Primers JDA105/106/197/198 were used to generate the requisite PCR products. Strain JD311 was then made chemically competent using TSS [LB supplemented with 0.1 g/mL PEG-8000, 30 mM MgCl2, 5% DMSO] and transformed with pJD075 and recovered for 1 hour on LB supplemented with chloramphenicol, spectinomycin, and 1% arabinose before plating on the above media supplemented with tetracycline (10 μg/mL). Colonies were grown on LB supplemented with chloramphenicol, tetracycline, and 5 nM N-(β-Ketocaproyl)-L-homoserine lactone (HSL) to OD600 0.2 before addition of sucrose to 5%. Cells were grown to OD600 1.0 and plated on LB supplemented with chloramphenicol, tetracycline, HSL, and 5% sucrose. Individual colonies were then replica plated with or without spectinomycin to identify colonies lacking the Shoji plasmid and a single spectinomycin-sensitive strain was saved as JD321.

The GFP induction control strain (JD270) was generated by transforming pJD036 [T9002 in the pSB1A3 backbone] into TSS-competent NCM3722 E. coli (JD189), and selecting for ampicillin resistance.

Purification of ribosome biogenesis related proteins from the ASKA collection

Ribosome biogenesis-associated proteins (see Key Resource Table) were purified from the ASKA collection overexpression (Kitagawa et al., 2005) library as follows. Cells were grown in 24-well format in 5 mL of LB media supplemented with chloramphenicol (35 μg/mL) to OD ~0.5 before induction with 1 mM IPTG. Cells were harvested 4 hours post-induction by centrifugation at 5,000xg for 15 mins and the pellet was saved at −80°C. Each pellet was resuspended in 500μL B-PER (Thermo) supplemented with 1mM PMSF, 2μL benzonase nuclease (Sigma), 0.01mg/mL lysozyme, 5mM β-mercaptoethanol, and incubated for 10 mins at 4°C. After centrifugation, the supernatant was applied to 50μL of TALON resin (clonetech) in a 96-well fritted plate. This minicolumn was washed twice with 400μL PBS [10mM NaH2PO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4, 140mM NaCl, 3mM KCl; pH 7.4]. Pellet from lysis was washed with 500μL UB1 [10mM NaH2PO4, 500mM NaCl, 8M Urea, 5mM β-mercaptoethanol; pH 8.0] and incubated with shaking for 10 minutes. After centrifugation, the supernatant was added to the TALON resin and the resin was washed three times with 400μL buffer UB1 supplemented with 15mM imidazole. Samples were eluted with via histidine protonation using 500μL buffer EB1 [10 mM NaH2PO4, 500 mM NaCl, 8 M urea 10 mM BME; pH 4.5] and the eluent was neutralized using 50μL buffer NB1 [0.5 M NaH2PO4; pH 8.0]

Quantitation of growth rates, protein and RNA abundance as a function of HSL

Overnight cultures of JD321 or JD270 were grown in M9 supplemented with tetracycline (10 μg/mL), chloramphenicol (35 μg/mL), and HSL (2 nM) or ampicillin (100 μg/mL) and HSL (2 nM), respectively. Cultures were diluted 1:1,000 into 100 mL cultures with various levels of HSL and grown with aeration (200 rpm) at 37°C. Growth rates and GFP production was quantified via OD600 and fluorescence using an EnVision platereader (Perkin Elmer) or by flow cytometry. To determine bL17 levels, 1.5 mL samples were taken at mid-log phase (OD600 ~0.3), spiked with a 15N-labeled reference standard lysate and quantified via mass spectrometry as described below.

Cellular protein levels were measured following the Biuret method as follows. First, 1 mL of cell culture was collected at mid-log phase by centrifugation and washed twice with an equal volume of water before resuspension in 0.2 mL water. The sample was then flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. For analysis, the sample was thawed at room temperature before addition of 0.1 mL NaOH and heating to 100°C for 5 mins. Samples were then cooled to room temperature for 5 mins in a water bath before addition of 0.1 mL 1.6% CuSO4. After mixing at room temperature for 5 mins, samples were centrifuged and the absorbance at 555 nm of the supernatant was measured and compared to that of a standard curve prepared using known concentrations of BSA as described above. Protein concentration was normalized to the OD600 of the culture sampled.

Total cellular RNA levels were measured as follows. First, 1.5 mL of cell culture was collected by centrifugation and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. After thawing, the pellet was washed twice with 0.6 mL cold 0.1 M HClO4, followed by treatment with 0.3 mL 0.3 M KOH for 60 mins at 37°C with constant mixing. Samples were then treated with 0.1 mL 3 M HClO4, and centrifuged at 16,000xg for 10 mins. The supernatant was collected and the pellet was washed and collected twice with 0.5 mL 0.5 M HClO4. These supernatants were combined into 1.5 mL total volume and the absorbance at 260 nm was measured.

Cell growth and isolation of ribosomal particles

Strain JD321 was grown under either bL17 permissive (2.0 nM HSL) or non-permissive (0.1 nM HSL) conditions in 14N-labeled supplemented M9 media [48mM Na2HPO4, 22mM KH2PO4, 8.5mM NaCl, 10mM MgCl2, 10mM MgSO4, 5.6mM glucose, 50μM Na3·EDTA, 25mM CaCl2, 50μM FeCl3, 0.5μM ZnSO4, 0.5μM CuSO4, 0.5μM MnSO4, 0.5μM CoCl2, 0.04μM d-biotin, 0.02μM folic acid, 0.08μM vitamin B1, 0.11μM calcium pantothenate, 0.4nM vitamin B12, 0.2μM nicotinamide, 0.07μM riboflavin, and 7.6mM (14NH4)2SO4] supplemented with 10 μg/mL tetracycline and 35 μg/mL chloramphenicol. Cells were harvested at OD=0.5 and lysed in Buffer A [20mM Tris-HCl, 100mM NH4Cl, 10mM MgCl2, 0.5mM EDTA, 6mM β-mercaptoethanol; pH 7.5] using a mini bead beater. Clarified lysates (5mL) were fractionated on a 10–40 % w/v sucrose gradient [50mM Tris-HCl, 100mM NH4Cl, 10mM MgCl2, 0.5mM EDTA, 6mM β-mercaptoethanol; pH 7.5].

Preparation of sample for quantitative mass spectrometry

Individual 14N-labeled fractions were spiked with either a 15N-labeled reference cell lysate purified from JD189 (all fractions) or 70S particles (experimental LSU and 70S peak fractions from permissive and restrictive growth conditions) isolated from strain JD189 as above. Samples were precipitated with 13% TCA at 4°C overnight, pelleted by centrifugation and pellets were successively washed with cold 10 % TCA and acetone. Pellets were resuspended in buffer B [100mM NH4CO3, 5% acetonitrile, 5mM dithiotreitol]. After incubation for 10 minutes at 65°C, 10mM iodoacetamide was added, and samples were incubated at 30°C for 30 minutes. Samples were then digested using 0.2μg trypsin at 37°C overnight.

Quantitative mass spectrometry of ribosomal proteins and assembly factors

Peptides were analyzed on a Sciex 5600+ Triple TOF mass spectrometer coupled to an Eksigent nano-LC Ultra with a nanoflex cHiPLC system as outlined in supplemental workflow 1 (see Key Resource Table). Samples were loaded onto a 200μm x 0.5 mm ChromXP C18-CL 3 μm 120 Å Trap column. Peptides were resolved using a 120 minute convex 5%–45% acetonitrile gradient run over a 75 μm x 15 cm ChromXP C-18-CL 3 μm 120 Å analytical column (Gulati et al., 2014). Each sample was injected twice and first analyzed in a data-dependent acquisition mode using a cycle consisting of 250 ms MS1 followed by 30 successive 100 ms MS2 scans. Rolling collision energy was utilized. Second, samples were analyzed using a SWATH data independent acquisition scheme consisting of a 200 ms MS1 followed by 64 100 ms MS2 scans each isolating a 12.5 Th window ranging from 400 to 1200 Th. Using these datasets, as well as those obtained from whole cell lysates grown at various HSL concentrations (below) and a set of injections using assembly-related proteins purified from the ASKA collection (Kitagawa et al., 2005), data-dependent acquisitions were searched for 14N-labeled peptides against a proteome consisting of E. coli (Uniprot UP000000625), a set of common contaminants, and a decoy set of proteins consisting of each protein sequence reversed using Comet (Eng et al., 2013) and x!Tandem with the k-score plugin (MacLean et al., 2006) as outlined in supplemental workflow 2. Search parameters can be found in the Key Resource Table. Peptide probabilities were scored using PeptideProphet and search results were combined via iProphet (Shteynberg et al., 2011) using the Trans-proteomic pipeline. A consensus spectral library was then built using SpectraST (Lam et al., 2007) using a minimum iProb cutoff that corresponded to a protein false discovery rate of ~0.8%, as determined by the MAYU tool. Retention times were normalized using endogenous, high abundance iRT peptides identified previously (Stokes et al., 2014). Well ionized proteotypic peptides lacking spectral interference for ribosomal and assembly factor proteins were identified from the SWATH datasets using Skyline (MacLean et al., 2010), resulting in ~15,000 product ion transitions corresponding to ~3,600 precursor ions, with a light (14N) and heavy (15N) specie measured for each transition. Peptide abundance was calculated as the sum of 14N product ion transitions, divided by the sum of 15N product ion transitions. For ribosomal proteins, this abundance, which was relative to a cell lysate, was converted to that relative to a mature 70S particle using a correction factor determined using the 70S peak fraction from a WT cell analyzed relative to the reference lysate. Peptides analyzed were filtered for mass accuracy, retention time drift, dot product match to spectral library, and 14N/15N spectral dot product. The distribution of these values was inspected on a dataset-by-dataset basis and outliers consisting of ~10% of the total dataset were discarded. Resultant peptides were further filtered for spectral interference by hand. These quantitative workflows are outlined in workflows 3, 5, 5b, 6. Python scripts utilized in these analyses are available at www.github.com/williamsonlab/Davis_Tan_2016.

Whole cell proteomics

14N-labeled experimental cultures (1.5 mL) were mixed with a 15N-labeled reference culture composed of JD321 and JD270 cells grown with 0.1 or 2 nM HSL, pelleted and resuspended in 150 μL of 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0). Cultures were lysed by iterative freeze-thaw cycles, pelleted by centrifugation and the supernatant was precipitated with methanol/chloroform [4:1]. After drying, tryptic peptides were generated as described above substituting 0.5 μg of Trypsin/LysC (Pierce) for the described 0.2 μg of Trypsin. Chromatography, data-dependent and SWATH data-independent mass spectrometry, peptide identification, and quantitation were performed as described and are outlined in supplemental workflow 3.

Pulse-labeling proteomics

Samples were pulse-labeled after growing to mid-log phase in 14N-labeled media by the addition of 1 equivalent of 15N-labeled media, resulting in partially labeled peptides. Samples (lysate or purified particles) were then spiked with a 15N-labeled 70S particle as a reference. Data was acquired in data-dependent acquisition mode and searched for ribosomal proteins with Comet and scored with peptideProphet and iProphet. Spectrast was then used to generate a consensus library, which was used to guide the extraction of MS1 isotope distributions by Massacre (V. Patsalo, personal communication). Fits were filtered for isobaric interferences using a series of custom Python scripts. This workflow is outlined in supplemental workflow 4.

SHAPE-MaP based quantitation of rRNA secondary structure

Ribosomal particles were purified on sucrose gradients as described above, concentrations were determined using A260, and 10 pmols was incubated for 3 minutes at 37°C with either 20 mM 1m7 or an equal volume of DMSO in a 450 μL reaction. For each sample, rRNA was purified by Trizol extraction and isopropanol precipitation, and RNA was fragmented by incubation at 95°C in 2.5X 1st strand synthesis buffer (NEB) for 4 minutes. After fragmentation and purification on a G-50 microspin column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences), reverse transcription reactions were primed with 200 ng of random nonamer primers (NEB) in the presence of MnCl2-bearing RTB [0.7 mM dNTPs, 50 mM Tris-HCl, 75 mM KCl, 6 mM MnCl2, 14 mM DTT] to allow for read-through and introduction of mutations at modified bases. The resulting cDNA library was purified on a G-50 spin column and prepared for Illumina sequencing using NEBNext non-directional 2nd strand synthesis, EndRepair, dA tailing, and TruSeq-barcoded adapter ligation kits (NEB). Libraries were quality-checked for expected fragment sizes using a BioAnalyzer, before the samples were pooled and gel purified for fragments ~200–500 bp in length. Samples were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq with unpaired 1x75 bp reads, resulting in ~400 Mb per sample. After quality score and adapter trimming, reads were aligned to the rrnB P1 transcript sequence, and the per residue mutation rate was determined for each sample analyzed after treatment with either 1M7 (mutR1M7) or DMSO (mutRDMSO) using the SHAPE-Mapper toolset (Siegfried et al., 2014). For each particle analyzed, residue-specific SHAPE reactivity (SRparticle) was calculated as max([mutR1M7 - mutRDMSO]*1000, 0.0). For 23S rRNA, which was purified from 70SWT particles via Trizol extraction, the per-residue SHAPE reactivity was broken into the following ranges; [SR23S < 1.5] = 0; [1.5 ≤ SR23S ≤ 3.0] = 3.0; [3.0 < SR23S] = 6.0. SHAPE reactivity was plotted on the 23S structure using Mathematica.

Next-generation sequencing based quantitation of rRNA processing

DMSO-treated samples were prepared and sequenced as described above and the number of reads mapped to each residue was determined using SHAPE-Mapper. Reads mapping to immature (residues 2267–2274, 5′; 5179–5187, 3′) or mature termini (residues 2275–2282, 5′; 5170–5178, 3′) were summed and the ratio of immature to mature mapped reads was reported.

Electron microscopy data collection

The LSUbL17dep sample was isolated via sucrose gradient centrifugation (see above) and spin-concentrated using a 100 kDa MW filter (Amicon). 3 μl of this sample were added to plasma cleaned (Gatan, Solarus) 1.2μm hole, 1.3μm spacing holey gold grids (Russo and Passmore, 2014) and plunge frozen into liquid ethane using a Cryoplunge 3 system (Gatan) operating at > 80% humidity, 298K ambient temperature. Single-particle data was collected using the Leginon software package. Data was acquired over two sessions on a Titan Krios microscope (FEI) that is equipped with a K2 summit direct detector (Gatan) operating in counting mode, with a pixel size of 1.31 Å at 22,500x magnification. A dose of 33 to 35 e−/Å2 across 50 frames was used for a dose rate of ~5.8 e−/pix/sec. To compensate for highly preferred orientations, data was collected with tilts ranging from 0° to 60° at 10° increments (Tan et al., in preparation). A total of 2,479 micrographs were collected.

Electron microscopy micrograph pre-processing and particle stack cleaning

Data processing was performed using several packages incorporated into the Appion pipeline (New York Structural Biology Center). Frames were aligned using UCSF DRIFTCORR software (Li et al., 2013b), and initial CTF estimation on the aligned and summed frames was performed with CTFFind3 and CTFTilt (Mindell and Grigorieff, 2003). Micrographs were visually inspected, and aggregated proteins, regions containing gold substrate, and obvious contamination were masked out using the manual masker in Appion. A total of 84,028 particles from the first dataset were selected ab initio using DoG Picker (Voss et al., 2009), extracted and subjected to 2D classification using Xmipp CL2D (Sorzano et al., 2010) to exclude poorly resolved particles. Recognizable class averages, based on visual assessment, were selected and used as templates for a new round of particle selection using FindEM (Roseman, 2004) for both datasets to produce a stack of 447,017 particles. The resulting stack was then subjected to two more rounds of 2D classification using CL2D. The final “clean” stack composed of 131,899 particles resembling ribosomes or ribosomal subunits was exposure filtered (Grant and Grigorieff, 2015) and individual particle “movies” were aligned using local per-particle frame alignment (Rubinstein and Brubaker, 2015). CTF values were then re-estimated on a per-particle basis using GCTF (Zhang, 2016).

Electron microscopy density reconstruction, 3D classification, and refinement

An initial model for the 3D classification was generated using Optimod (Lyumkis et al., 2013b) using the class averages from the final round of CL2D classification from the first dataset. Euler angles and shifts for the particles were determined using Xmipp projection matching (Sorzano et al., 2004) using this initial model as a reference. Iterative 3D classification was then performed using Frealign (Lyumkis et al., 2013a). The initial iteration used 15 classes and ran for 100 rounds. The resulting models were visually examined and grouped according to their similarity; classes inconsistent with a large subunit particle were segregated for later analysis. A total of 5 major classes were identified based on differences in gross structural features. Further sub-classification of 100 iterations was performed on these major classes, targeting between 2 and 6 sub-classes. This number was varied, and a final value was selected such that the classification would produce at least 2 nearly identical models. This strategy indicated that the different 3D classes recovered from the data accurately represented the majority of the real heterogeneity present within the data, at least at the nominal resolution of the reconstructions and using our specific global classification strategy implemented within Frealign. This approach produced a total of 14 different cryo-EM density maps with global resolutions ranging between 4.0 Å to 6.5 Å, including a “70S-like” particle (Figure 3). Global resolutions were determined by masking the two half-maps, calculating the FSC between them using “proc3d” within EMAN and with a cutoff value of 0.143. Masks were generated using Relion by visualizing the map in UCSF Chimera, selecting a threshold for binarization at a contour level that begins to show high-resolution features, extending the mask by 3 pixels and finally appending a soft Gaussian edge of 3 pixels in order to reduce spurious correlations. YjgA densities in D3 and E3 classes were present but weak, indicating that the cofactor is likely to be partially occupied. Determination of the occupancy of YjgA in these classes was carried out using a 3 class multi-model global classification in Frealign (Grigorieff, 2016). For both intermediates, about 30% of the particles had YjgA bound, while 70% did not. Other than YjgA, the rest of the intermediates lacked discernable differences when compared in UCSF Chimera. A second round of 2D classification using Xmipp CL2D in Appion was performed on the excluded particles noted above and a new initial model of these class averages was generated using Optimod. Subsequently, Relion (Scheres, 2012) 5 class multi-model classification was performed on this stack and using the generated initial model, resulting in a single model of the 30S subunit, which was further refined using Frealign to a resolution of 7.9 Å.

B-factor sharpening was performed using bfactor program, which is distributed with Frealign. Classes C1, C2, C3, D1, D2, D3, D4, E1, E2, E3, E4 and E5 were amplitude scaled using diffmap program, also distributed with Frealign, to the lowest resolution 50S intermediate, class B, for subsequent comparison of protein occupancy. For visualization of the EM maps and generation of figures, UCSF Chimera was used. Local resolution was calculated using the ResMap software (Kucukelbir et al., 2014).

Quantitation of rRNA and protein occupancy in EM density maps

The E. coli 50S subunit from the PDB model 4ybb was segmented into 109 separate chains according to rRNA secondary structure maps with an additional chain for each protein (Petrov et al., 2014). Theoretical density was then calculated for each element (helix or protein) at 5 Å using the pdb2mrc command within EMAN (Ludtke et al., 1999). This surface was then binarized at the threshold value 0.026 to generate a mask that was applied to each amplitude-scaled map, and the resulting included volume was calculated using the “volume” command in EMAN (Ludtke et al., 1999). This value was normalized to the total volume of the mask and noted as vol(j,i)init for each class i, and each element j. For each element, final occupancy values, vol(j,i)final were calculated as vol(j,i)init/[max(max(vol(j,i)init for all classes), median(vol(j,i)init for all classes and all occupied elements]. This value, which scaled from 0 to 1 was also calculated for all threshold values from 0.020 to 0.030 and plotted for each element and each class as a function of threshold. This analysis revealed that the calculated occupancy observed between different classes was insensitive to the threshold used (Fig. S6), and the value of 0.026 was selected for all subsequent analyses. Additionally, the calculated occupancy corresponded well to that observed by manual inspection. Element occupancy values were hierarchically clustered across both rows (rRNA/protein elements) and columns (classes) using a euclidean distance metric and complete linkage method (Mathematica).

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Quantitation of mass spectrometry data detailed above. Statistical values, where calculated, can be found in the Figure legends.

DATA AND SOFTWARE AVAILABILITY

Novel software tools utilized in this manuscript have been deposited at www.github.com/williamsonlab/Davis_Tan_2016. All maps are deposited at EMDB as noted in the Key Resource Table. Processed data files from quantitative mass spectrometry experiments are available in the github repository above as noted in the Key Resource Table.

Supplementary Material

| (1) |

(C) Ratio of total cellular RNA to protein as a function of HSL concentration in JD321 (black) or control JD270 (gray) cells. (D) Ribosomal protein and (E) assembly factor or chaperone protein levels as measured by qMS, shown as a heat map, in bL17-limitation JD321 (left) or control JD270 (right) cells as a function of HSL concentration, which ranged from 1.25 nM to 0.039 nM using 2-fold dilutions. For each protein, abundance is normalized to that observed in the 1.25 nM condition and is reported as a fold induction (red) or repression (blue). Proteins individually plotted in Fig. 1 are shown in bold. Assembly factors with significant induction are highlighted in orange, and chaperones exhibiting significant repression are highlighted in cyan.

Figure S2. Related to Figure 2: LSUbL17dep particles are maturation-competent assembly intermediates. (A) Growth (OD600) of JD321 grown under restrictive conditions and pulsed to permissive conditions at time 0. Pre-pulse (red circles) and post-pulse (green triangles) growth were fit to growth rates of 0.0045 and 0.011 mins−1 respectively. A ~15–30 minute lag between these stable regimes (blue squares) is noted by black dotted lines. 23S rRNA maturation state at the 5′ (B) or 3′ (C) termini. LSU (solid) or 70S (outline) particles were isolated from bL17-limited (JD321, 0.1 nM HSL; red) or wild-type cells (JD189; black) and the ratio of next-generation sequencing reads mapping to rrnB-P1 immature residues (2267–2274, 5′; 5179–5187, 3′) versus those to mature residues (2275–2282, 5′; 5170–5178, 3′) are plotted. (D) Synthesis rate of ribosomal proteins. bL17-limited cells were pulsed with a stable isotope to quantify protein synthesis using qMS and a fixed reference standard composed of 15N-labeled 70S particles. Newly synthesized (normalized post-pulse isotope label) bL17, bL32, bL33, bL35, and the median LSU r-protein are plotted vs. time post-pulse. (E) Degradation of ribosomal proteins. Cells were grown and pulsed as in (D), however the normalized pre-pulse isotope level is plotted versus time. Curves labeled as in (D).

Figure S3. Related to Figure 3: R-protein binding is re-routed upon bL17 depletion. (A) Heat map of LSU protein abundance relative to a purified 70S particle across a sucrose gradient purified from cells grown under bL17-permissive conditions (JD321, 2.0 nM HSL). Occupancy patterns were hierarchically clustered, and protein labels are colored according to the bL17-limited groups from Figure 3A. (B) Heat map of LSU protein abundance relative to a 70S particle. Gradients run as in Figure 2A and samples collected at LSUbL17dep region (pre-50S, ~32% sucrose), or from the 70S peak (70S, ~37% sucrose) for either wild-type cells (JD189) or bL17-restricted cells (JD321, 0.1 nM HSL). Each fraction analyzed in duplicate (1,2). Pre-50S fractions were analyzed before (pre) and after (post) being subjected to concentration in a 100 kDa cutoff spin filter. Abundance in each column was normalized to that of bL24. (C) Heat map of ribosome associated protein abundance relative to a fixed cell lysate across sucrose gradients from cells grown under bL17-restrictive or bL17-permissive conditions. Assembly co-factors significantly enriched in the LSUbL17dep particle are in bold. Sucrose gradient profiles depicted above. (D) SHAPE reactivity profile resulting from chemical probing of protein-free rRNA mapped onto the 23S secondary structure. SHAPE values represent background corrected mutation rate in per-mille, which has been quantized according to the scale bar. Circles represent individual residues, and their size scales according to SHAPE reactivity. 23S rRNA domains noted (0, I, II, etc.). (E) SHAPE reactivity differences between LSUbL17dep and 70SWT mapped onto the 23S secondary structure. For each particle, SHAPE values calculated as in (D), and the absolute value of the difference is plotted. The 5′ and 3′ 23S termini, the peptidyl transferase center, and a portion of the bL17 binding site are outlined in red, orange, and blue, respectively.

Figure S4. Related to Figure 4: Cryo-EM 3D classification and refinement of LSUbL17dep particles. (A) Local resolution maps for each class generated using ResMap. A longitudinal slice, front view, and back view are shown for each map. (B) Plots of Fourier shell correlation versus spatial frequency, grouped by super-classes. Class F, the lowest resolution structure obtained, is plotted with each group for comparison. The FSC cutoff of 0.143 was used to report resolution is noted.

Figure S5. Related to Figure 5: Reconstructed maps of bL17-limited assembly intermediates. (A) View of the peptide exit channel with each super-class shown as a colored semi-transparent surface. Classes colored as in Figures 4/5. Proteins marking the exit tunnel are noted. (B) Detailed view of the peptidyl transferase center (PTC) disordered (class E4, top) or nearly-native (class E5, bottom) confirmation. A-site and P-site rRNA residues colored red. (C) Maps from classes C1 (orange and yellow) or D1 (green, right) with docked LSU model (PDB: 4ybb, blue). 5S and rRNA helices near the central protuberance (CP) colored red and purple, respectively. (D) 2D-class averages showing undocked CP (top) or properly-docked CP (bottom), which is noted with a white arrow.