Abstract

BACKGROUND

Bevacizumab has recently been demonstrated to prolong overall survival when added to carboplatin and paclitaxel for chemotherapy-naïve patients with nonsquamous nonsmall-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). However, the effects of combining bevacizumab with other standard, front-line, platinum-based doublets have not been extensively explored. We designed this single treatment arm, phase 2 trial to determine whether the combination of carboplatin, docetaxel, and bevacizumab is tolerable and prolongs progression-free survival of chemotherapy-naïve patients with advanced, nonsquamous NSCLC.

METHODS

Forty patients were treated with up to 6 cycles of carboplatin (AUC 6), docetaxel (75 mg/m2), and bevacizumab (15 mg/kg) on Day 1 every 21 days. Patients with an objective response or stable disease received maintenance bevacizumab (15 mg/kg) every 21 days until disease progression. The primary endpoint was median progression-free survival. Secondary endpoints included safety, response rates, and overall survival.

RESULTS

The median number of chemotherapy and maintenance bevacizumab cycles/patient was 6 and 2, respectively. Grades 3–5 adverse events included febrile granulocytopenia (10%), infections (13%), bleeding (13%), thrombotic events (13%), hypertension (5%), bowel perforation (5%), and proteinuria (3%). Median progression-free survival was 7.9 months and median overall survival was 16.5 months. Partial responses were observed in 21 patients (53%), and stable disease ≥6 weeks occurred in another 17 patients (43%), for a disease control rate of 95%.

CONCLUSIONS

Carboplatin, docetaxel, and bevacizumab were feasible and effective for front-line treatment of advanced, nonsquamous NSCLC. These data provide further evidence that bevacizumab may be used in combination with multiple standard, platinum-based doublets in this setting.

Keywords: nonsmall-cell lung cancer, docetaxel, carboplatin, bevacizumab, front-line

Angiogenesis plays a central role in nonsmall-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) carcinogenesis, through 1 of its key mediators, the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Merrick et al demonstrated that VEGF expression levels in bronchial epithelial cells of smokers progressively increase in low to high grade dysplasia.1 In patients with established lung tumors, there is an association between high circulating levels or intratumoral overexpression of VEGF and poor prognosis.2–6 VEGF may also facilitate pleural dissemination of lung cancers.7 In preclinical models of NSCLC, VEGF blockade has been shown to inhibit angiogenesis,8 decrease tumor growth,9 stimulate apoptosis of cancer cells,9 and enhance antineoplastic chemotherapy effects.10 Taken together, these data support the evaluation of anti-VEGF therapies in patients with NSCLC.

Bevacizumab is a monoclonal, recombinant, humanized murine antibody targeted at vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). In 2005, the Eastern Oncology Cooperative Group (ECOG) reported the results of the first randomized, phase 3 trial of carboplatin and paclitaxel ± bevacizumab in patients with chemotherapy-naïve, recurrent or metastatic, nonsquamous NSCLC (E4599). Median progression-free survival and overall survival increased from 4.5 and 10.3 months in the chemotherapy alone treatment arm, respectively, to 6.2 and 12.3 months in the chemotherapy plus bevacizumab treatment arm (P < .05).11 These results led to approval of the carboplatin, paclitaxel, and bevacizumab combination in this setting.

Although carboplatin and paclitaxel are commonly used in the United States for front-line treatment of patients with NSCLC (and have been considered the standard backbone chemotherapy regimen in ECOG trials), several large, randomized, phase 3 trials have demonstrated similar efficacy of other chemotherapy agents (ie, gemcitabine, docetaxel, and vinorelbine) combined with a platinum salt.12–15 Fossella et al, for example demonstrated that carboplatin and docetaxel elicited a median overall survival of 9.4 months compared with 9.9 months for cisplatin and vinorelbine (P = .657) in the randomized phase 3 TAX 326 study, with a superior quality of life for the docetaxel-treated patients.15 The median progression-free survival was 4.7 and 5.1 months for carboplatin and docetaxel versus cisplatin and vinorelbine, respectively (P = .235).15 These results established platinum-docetaxel as a valid treatment option for chemotherapy-naïve, metastatic NSCLC.

Despite the similar outcomes observed with the use of front-line combinations of platinum with paclitaxel, gemcitabine, vinorelbine, or docetaxel, it was unknown whether addition of bevacizumab to standard-of-care doublets other than carboplatin and paclitaxel would result in improved efficacy. Hence, we designed a single treatment arm, phase 2 trial to determine whether the combination of carboplatin, docetaxel, and bevacizumab is tolerable and prolongs progression-free survival of chemotherapy-naïve patients with advanced, nonsquamous NSCLC, compared with historical controls.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was an open-label, single treatment arm, phase 2 trial conducted at The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center. The study was approved by the institutional review board and was conducted in accordance with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. All subjects signed a written informed consent statement before participation in this study.

Patient Eligibility

Patients included in this study had a histologically confirmed advanced stage IIIB or IV nonsquamous NSCLC, for whom no curative options existed, were eligible for front-line cytotoxic treatment, age ≥18 years, at least one measurable lesion as defined by the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST),16 and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) of 0 or 1. Patients were excluded based on the following criteria: if they had previous exposure to full-dose chemotherapy for NSCLC in the neoadjuvant, adjuvant, or metastatic setting within 6 months; absolute neutrophil count <1500/µL, platelet count of <75,000/µL; hemoglobin of <9 g/dL; prothrombin time international normalized ratio (INR) >1.5; total bilirubin >upper normal limit (UNL); aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), or alkaline phosphatase >5 times the UNL for subjects with documented liver metastases, or >2.5 times the UNL for subjects without evidence of liver metastases; serum creatinine of >2.0 mg/dL; prior exposure to anti-VEGF therapy; blood pressure of >140 of 90 mm Hg as documented in 2 consecutive blood pressure readings within 4 hours; any prior history of hypertensive crisis or hypertensive encephalopathy; New York Heart Association (NYHA) grade ≥2 heart failure; history of myocardial infarction or unstable angina within 6months; history of stroke or transient ischemic attack within 6 months; significant vascular disease (eg, aortic aneurysm, aortic dissection); clinically significant peripheral vascular disease (ie, symptoms of claudication that interfere with patients overall activity); evidence of bleeding diathesis or coagulopathy; presence of central nervous system or brain metastases at any time; major surgical procedure, open biopsy, or significant traumatic injury within 28 days before treatment, or anticipation of need for major surgical procedure during the course of the study; minor surgical procedures, such as fine-needle aspirations or core biopsies, within 7 days before treatment; pregnancy or lactating; proteinuria at screening, as demonstrated by either a urine protein-creatinine ratio ≥1.0, or urine dipstick for proteinuria ≥2+ (patients discovered to have ≥2+ proteinuria on dipstick urinalysis at baseline underwent a 24 hour urine collection and must have demonstrated ≤2 g of protein in 24 hours to be eligible); history of abdominal fistula, gastrointestinal perforation, or intra-abdominal abscess within 6 months; serious, nonhealing wound, ulcer, or bone fracture; history of hemoptysis (bright red blood of 1 to 2 teaspoons or more); full-dose anticoagulation; chronic use of aspirin (> 325 mg/day) or nonsteroidal antiinflammatories; or presence of other medical condition that would contraindicate the use of the investigational drug(s) or render the subject at high risk from treatment complications.

Treatment Plan

Baseline evaluation included a complete history and physical examination, serum chemistry and hematologic tests, and imaging studies for assessment of evaluable lesions. If all eligibility criteria were met, patients initiated treatment with carboplatin (area under the curve [AUC] of 6) intravenously (IV) on Day 1, docetaxel (75 mg/m2) IV on Day 1, and bevacizumab (15 mg/kg) IV on Day 1. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) support use was not mandatory but was allowed for primary prophylaxis of febrile neutropenia at the discretion of the treating physician. Cycles were repeated every 21 days until disease progression, death, or intolerable toxicity. Blood count, electrolytes, and liver function tests were obtained before each cycle. Proteinuria (urine protein-creatinine ratio or dipstick urinalysis) was monitored every 2 cycles. Imaging studies for assessment of treatment response were also obtained every 2 cycles. Chemotherapy (ie, carboplatin and docetaxel) delays, dose reductions, and discontinuation were implemented according to standard criteria prespecified in the protocol. Bevacizumab dose reductions were not allowed. Bevacizumab administration was delayed if patients experienced grade 3 nonpulmonary and noncentral nervous system hemorrhage (until resolution of the bleeding), grade 3 congestive heart failure (until resolution to grade ≤1), grade 3 proteinuria (until resolution to grade ≤2), and grade ≥2 bowel obstruction (until resolution of the obstruction). Bevacizumab was permanently discontinued in the following cases: grade 3 hypertension not controlled by medication or grade 4 hypertension; grade ≥2 pulmonary or central nervous system hemorrhage or grade 4 hemorrhage at any site; symptomatic grade 4 venous thromboembolism; arterial thromboembolic event (any grade); grade 4 congestive heart failure; grade 4 proteinuria, gastrointestinal perforation (any grade); and wound dehiscence (any grade). Patients who required a treatment delay ≥2 months (regardless of the reason) were not permitted to restart bevacizumab. Six cycles of chemotherapy plus bevacizumab were planned. Patients who demonstrated stable disease (SD), partial response (PR), or complete response (CR) to treatment continued on single-agent bevacizumab 15 mg/kg every 21 days until disease progression or intolerable toxicity. Patients who discontinued chemotherapy before 6 cycles of treatment were also allowed to continue on single-agent bevacizumab in the absence of progressive disease (PD).

Study Endpoints and Statistical Analysis

The primary endpoint of the study was progression-free survival, defined as the time from treatment initiation to disease progression or death. We estimated the historical median progression-free survival as approximately 4.5 months in patients treated with docetaxel and carboplatin, based on the randomized phase 3 TAX 326 study.15 An increase in median progression-free survival to 6.3 months with the addition of bevacizumab would be considered significant. Assuming a 1-sided type I error rate of 10% and exponential progression-free survival, a study with 50 patients would have at least 81% power to detect the aforementioned treatment effect. No interim analyses were planned.

Secondary endpoints of the study included the assessment of overall survival, disease control rate (CR + PR + SD, defined by RECIST16), and evaluation of the safety profile of this triple-agent regimen.

All patients who received at least 1 dose of the study drug were analyzed for efficacy and toxicity endpoints. Continuous variables are presented using median (range). Categorical variables are summarized in frequency tables. Time-to-event endpoints were computed using the method of Kaplan and Meier.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Between December 2005 and February 2009, 40 patients were enrolled in the study. Their baseline characteristics are described in Table 1. The trial was interrupted before the planned 50 patients were enrolled because of slow accrual after bevacizumab became commercially available in the United States for NSCLC treatment.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Eligible Patients (N=40)

| Characteristic | No. (%) of Patients |

|---|---|

| Median age, y [range] | 63 [29–77] |

| Performance status | |

| 0 | 11 (28) |

| 1 | 29 (73) |

| Sex | |

| Women | 22 (55) |

| Men | 18 (45) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Caucasian | 34 (85) |

| African American | 2 (5) |

| Asian | 2 (5) |

| Hispanic | 2 (5) |

| Smoking status | |

| Never smoker | 9 (23) |

| Former/current smoker | 31 (78) |

| Histology | |

| Nonsmall-cell carcinoma, NOS | 15 (38) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 25 (63) |

| Stage | |

| IIIB | 2 (5) |

| IV | 38 (95) |

| Previous radiotherapy | |

| No | 38 (95) |

| Yes | 2 (5) |

NOS indicates not otherwise specified.

Treatment Characteristics

A total of 363 cycles of treatment were delivered to all enrolled patients and dose reductions were uncommon (≤15% of the patients for docetaxel and/or carboplatin). The median number of chemotherapy + bevacizumab cycles was 6 and the median number of maintenance bevacizumab cycles was 2 (Table 2). G-CSF support was used in 11 patients (28%) as primary prophylaxis. The majority of patients (50%) discontinued the study drugs because of disease progression; however, 12 patients (30%) required treatment discontinuation because of toxicities (5 patients with thrombotic events, 2 patients with bowel perforation, 2 patients with hemoptysis, and 1 patient each with hypertension, allergic reaction, and infection). Five patients are still on treatment (Table 2).

Table 2.

Treatment Characteristics for 40 Patients

| Treatment Characteristics | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Total no. of cycles | 363 |

| Median no. of cycles per patient [range] | |

| Chemotherapy+bevacizumab | 6 [1–6] |

| Maintenance bevacizumab | 2 [0–40] |

| Patients with carboplatin dose reductions | |

| No dose reductions | 35 (88) |

| 1 Level (carboplatin AUC 5) | 5 (13) |

| 2 Levels (carboplatin AUC 4) | 0 |

| Patients with docetaxel dose reductions | |

| No dose reductions | 34 (85) |

| 1 Level (docetaxel 60 mg/m2) | 6 (15) |

| 2 Levels (docetaxel 50 mg/m2) | 0 |

| Median time on treatment, wka | 21 |

| Patients who discontinued treatment because of | |

| Disease progression | 20 (50) |

| Toxicities | 12 (30) |

| Achieved maximal benefit | 1 (3) |

| Need for radiotherapy | 1 (3) |

| Death | 1 (3) |

| Still on study | 5 (13) |

AUC indicates area under curve.

Calculated from the date of the first chemotherapy administration until the date of the last chemotherapy administration on study.

Toxicity

Hematologic toxicities were common with grades 3–4 anemia, thrombocytopenia, and granulocytopenia occurring in 10%, 15%, and 33% of the patients, respectively. Four patients (10%) had febrile granulocytopenia (Table 3). The most common grades 3–5 nonhematologic toxicities were infection (13%), hemorrhagic events (13%: 2 patients with hemoptysis, 2 patients with epistaxis, and 1 patient with pleural bleeding), and thrombotic events (13%: 2 patients with deep vein thrombosis, 2 patients with pulmonary embolism, and 1 patient with an ischemic cerebrovascular accident). Other grades 3–5 bevacizumab-related adverse events were seen at lower frequencies, such as hypertension (5%), bowel perforation (5%), and proteinuria (3%) (Table 3). Two patients had possible treatment-related deaths: 1 patient died suddenly on Day 10, cycle 1 (no autopsy), and 1 patient died from an infection in a necrotic lung mass after 12 cycles of treatment (at which point in time the patient also had disease progression).

Table 3.

Selected Grades 3–5 Adverse Events, Incidence per Patient (N=40)

| Adverse event | Grade | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 No. (%) |

4 No. (%) |

5 No. (%) |

No. (%) | |

| Hematologic toxicities | ||||

| Thrombocytopenia | 2 (5) | 2 (5) | — | 4 (10) |

| Anemia | 6 (15) | — | — | 6 (15) |

| Granulocytopenia | 4 (10) | 9 (23) | — | 13 (33) |

| Febrile granulocytopenia | 3 (8) | 1 (3) | — | 4 (10) |

| Nonhematologic toxicities | ||||

| Infection | 4 (10) | — | 1 (3) | 5 (13) |

| Hemoptysis | 2 (5) | — | — | 2 (5) |

| Epistaxis | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | — | 2 (5) |

| Hemorrhage, pleura | 1 (3) | — | — | 1 (3) |

| Hypertension | 2 (5) | — | — | 2 (5) |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 2 (5) | — | — | 2 (5) |

| Pulmonary embolism | — | 2 (5) | — | 2 (5) |

| Ischemic cerebrovascular event |

— | 1 (3) | — | 1 (3) |

| Sudden death | — | — | 1 (3) | 1 (3) |

| Bowel perforation | — | 2 (5) | — | 2 (5) |

| Allergic reaction | 1 (3) | — | — | 1 (3) |

| Proteinuria | 1 (3) | — | — | 1 (3) |

| Peripheral neuropathy, sensitive |

1 (3) | — | — | 1 (3) |

| Nausea/vomiting | 3 (8) | — | — | 3 (8) |

| Dehydration | 2 (5) | — | — | 2 (5) |

| Hypokalemia | 1 (3) | — | — | 1 (3) |

| Hyponatremia | 1 (3) | — | — | 1 (3) |

| Elevated AST | 1 (3) | — | — | 1 (3) |

| Fatigue | 1 (3) | — | — | 1 (3) |

AST indicates aspartate aminotransferase.

In regards to the 2 grade 3 hemoptysis events, the first patient was found to have treatment-induced cavitation of a lung lesion after 2 cycles of chemotherapy; the second patient had had prior episodes of blood mixed with sputum before study entry, not meeting the protocol’s exclusion criterion of bright red blood of 1 to 2 teaspoons or more. The hemoptysis, however, was exacerbated after 6 doses of bevacizumab. Both patients were adequately treated with radiation therapy and discontinuation of bevacizumab.

Efficacy

Thirty-eight patients have completed more than 2 cycles of treatment and are evaluable for response (2 patients discontinued treatment prematurely after 1 cycle of treatment because of sudden death and an episode of deep venous thrombosis). A PR was observed in 21 patients (53%, 95% confidence interval [CI], 37%–68%), of which 20 were confirmed. SD ≥6 weeks occurred in another 17 patients (43%), for an overall disease control rate (CR + PR + SD) of 95% (95% CI, 88%–100%) (Table 4). Median duration of response was 7.2 months and median duration of stable disease was 6.0 months.

Table 4.

Best Response to Treatment for 40 Patients

| Response | No. (%) of Patients |

|---|---|

| Complete response | 0 |

| Partial response | 21 (53) |

| Stable disease ≥12 wk | 17 (43) |

| Progressive disease | 0 |

| Nonevaluable | 2 (5) |

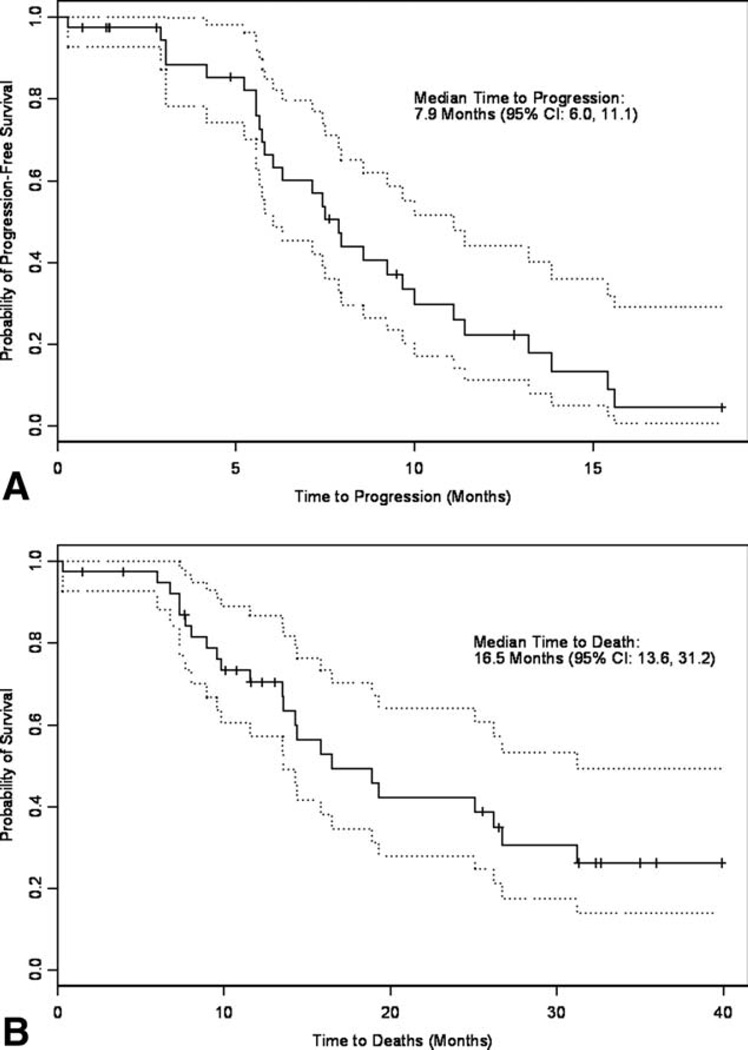

To date, 27 patients (68%) have had documented disease progression and 23 patients (58%) have died. Five patients (13%) are still on active treatment. The median progression-free survival was 7.9 months (95% CI, 6.0–11.1) (Fig. 1), indicating a statistically significant improvement over the historical control (evidenced by the lower boundary of the confidence interval above the historical median progression-free survival mark of 4.5 months). Median overall survival was 16.5 months (95% CI, 13.6–31.2) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

(A) Progression-free survival and (B) overall survival are shown. Dotted lines indicate 95% confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrated that treatment with the combination of carboplatin, docetaxel, and bevacizumab in chemotherapy-naïve patients with advanced nonsquamous NSCLC was associated with a median progression-free survival of 7.9 months and median overall survival of 16.5 months, which compares favorably to historical controls. Bevacizumab-related toxicities were observed and included bleeding, thrombosis, hypertension, bowel perforation, and proteinuria, as well as an increased risk of granulocytopenic fever.

Since the initiation of this study, in addition to E4599, the results of other trials exploring the incorporation of bevacizumab to first-line platinum-based doublets have been presented, including the randomized phase 3 AVAiL trial (cisplatin and gemcitabine ± bevacizumab),17 as well as the single treatment arm phase 2 studies of bevacizumab combined with carboplatin + pemetrexed,18 oxaliplatin + pemetrexed,19 and carboplatin + nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel.20 Hence, in addition to E4599 and TAX 326, these trials provide additional toxicity and efficacy data with which our results may be compared and contrasted.

Bleeding (including hemoptysis) has been associated with bevacizumab treatment for NSCLC, even in patients with nonsquamous histology. In E4599, grade ≥3 bleeding occurred in 22 of 427 bevacizumab-treated patients (5.2%), with hemoptysis occurring in 8 patients (1.9%).11 In AVAiL, grade ≥3 bleeding occurred in 28 of the 659 bevacizumab-treated patients (4.2%), with hemoptysis in 8 patients (1.2%).17 The incidence of bleeding in our study was 13% (including hemoptysis in 5% of the patients), which may seem somewhat higher than the previously reported experiences. However, the small number of patients could have overestimated the incidence of adverse events and precludes definitive conclusions on an increased bleeding risk with the carboplatin-docetaxel combination. Bleeding did not appear to be secondary to low platelet counts, because only 1 episode (epistaxis) occurred during grade 3 thrombocytopenia. The rate of venous thromboembolic events (10%), arterial thrombotic events (3%), hypertension (5%), bowel perforation (5%), and proteinuria (3%) were similar as previously observed in bevacizumab-treated groups in the E459911 and/or AVAiL17 trials.

Bevacizumab has also been shown to modestly increase the risk of chemotherapy-induced (febrile) granulocytopenia. In our study, 4 patients (10%) had febrile granulocytopenia, compared with 5.2% and 2% of bevacizumab- treated patients in the E4599 and AVAiL trials, respectively.11,17 The febrile granulocytopenia incidence in the TAX-326 study was 3.7% in the docetaxel-carboplatin treatment arm.15 Despite the higher incidence of febrile granulocytopenia, no fatal events were observed in this trial, possibly attributed to the frequent use of optional prophylactic G-CSF support (28%). This is in contrast with 5 and 1 granulocytopenic fever-related deaths in E4599 and AVAiL.11,17 Five patients (13%) in our study developed grade ≥3 infections with the rates comparable to the incidence of infection associated with carboplatin and docetaxel alone in TAX 326 (11%).15

The toxicity profile outlined above highlights the importance of adequate patient selection for bevacizumab treatment. In our study, we observed 2 possible treatment- related deaths (in E4599, 15 of 417 bevacizumab-treated patients had treatment-related deaths).11 The impact of bevacizumab on the incidence of adverse events is further illustrated by a 30% rate of toxicity-related treatment discontinuation (in AVAiL, 26%–30% of bevacizumab-treated patients discontinued treatment because of adverse events, compared with 23% of patients in the placebo treatment arm).17 Nonetheless, despite treatment-related complications, outcome measures overall were still favorable in our study.

The present trial met its primary endpoint of improving median progression-free survival compared with the carboplatin-docetaxel treatment arm in the TAX 326 study (from 4.7 to 7.9 months).15 Moreover, the median progression-free survival in our study compares favorably to E4599 (6.2 months)11 and AVAiL (6.5 months for the bevacizumab 7.5 mg/kg arm, and 6.7 months for the bevacizumab 15 mg/kg arm).17 The median overall survival (16.5 months) was also higher than carboplatin and docetaxel alone (9.4 months in TAX 326),15 and 1 of the highest observed among other platinum- based regimens plus bevacizumab: 12.3 months (for the carboplatin, paclitaxel, and bevacizumab treatment arm in E4599),11 13.4–13.6 (for the cisplatin, gemcitabine, and bevacizumab treatment arms in AVAiL),17 14.1 months (for carboplatin, pemetrexed and bevacizumab, phase 2),18 15.8 months (for carboplatin, nanoparticle albumin- bound paclitaxel, and bevacizumab, phase 2),20 and 16.7 months (for oxaliplatin, pemetrexed, and bevacizumab, phase 2).19

The greatest limitation of our study is that it is a single institution, single treatment arm, phase 2 trial with only 40 patients. As such, comparison of efficacy endpoints achieved with other regimens may be highly biased by patient selection. However, the promising progression-free survival and overall survival observed in our cohort of patients (especially when compared with E4599 and AVAiL) may lead us to speculate whether there is a preferred platinum-based regimen to which bevacizumab should be combined.

Docetaxel has been shown to inhibit endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and capillary formation, thus serving as an antiangiogenic agent by itself. VEGF confers resistance of endothelial cells to docetaxel, which is overcome by the addition of an anti-VEGF recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody to docetaxel, both in vitro and in vivo.21 Paclitaxel has also been demonstrated to have antiangiogenic properties (reviewed elsewhere).22 The antiangiogenic activities of docetaxel and paclitaxel have been compared in preclinical models: Hotchkiss et al demonstrated that human umbilical endothelial cells (HUVECs) were more sensitive to docetaxel than paclitaxel in chemokinetic or chemotactic migration assays in vitro23; Vacca et al demonstrated an enhanced inhibitory effect of docetaxel compared with paclitaxel in the angiogenic phenotype of HUVECs in vitro (proliferation, chemotaxis, vessel morphogenesis) and in vessel formation in the chick embryo chorioallantoic membrane angiogenesis model in vivo24; and Grant et al demonstrated that compared with paclitaxel, docetaxel is approximately 10 times more potent in inhibiting endothelial cell proliferation and differentiation into tubes and in promoting endothelial cell death in vitro.25 Taken together, these results suggest that docetaxel might be a more effective antiangiogenic agent than paclitaxel. When combined with bevacizumab in the clinical setting, regimens containing docetaxel might achieve highest antivascular effects and lead to enhanced response rates, progression-free survival and overall survival than paclitaxel-based regimens, thus possibly explaining the favorable results observed in this study when compared with E4599. Future exploratory analysis of 2 large-scale studies may further support this observation: ARIES is an observational treatment cohort study of first-line bevacizumab use for NSCLC in the community. A preliminary report demonstrated that of the first 621 patients, 61% received carboplatin plus paclitaxel, and 12% received carboplatin and docetaxel.26 ATLAS is a randomized study of maintenance erlotinib and bevacizumab versus bevacizumab alone after first-line chemotherapy with bevacizumab.27 Subgroup analysis comparing the efficacy of the different chemotherapies used in these studies might provide further evidence on what could be the preferential backbone cytotoxic regimen to be used with bevacizumab. Although strengthened by a large sample size, these analyses would still be exploratory and would have to be tested in a randomized setting, if appropriate.

In conclusion, this is the first reported study to use the carboplatin, docetaxel, and bevacizumab combination. Our study demonstrated that the regimen is feasible and effective as a first-line treatment for advanced, nonsquamous NSCLC cancer. Our data provide further evidence that bevacizumab may be used in combination with multiple standard platinum-based doublets in this setting.

Acknowledgments

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

This work was supported in part by a grant from Genentech. Drs. Scott M. Lippman and Edward S. Kim are members of the speaker’s bureau for both Genentech and Sanofi-Aventis.

Footnotes

The authors are indebted to the assistance provided by the research nurses and data managers. This study was conducted under the auspices of the Lung Cancer Program of The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center.

REFERENCES

- 1.Merrick DT, Haney J, Petrunich S, et al. Overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptors in bronchial dypslasia demonstrated by quantitative RT-PCR analysis. Lung Cancer. 2005;48:31–45. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2004.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yuan A, Yu CJ, Kuo SH, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor 189 mRNA isoform expression specifically correlates with tumor angiogenesis, patient survival, and postoperative relapse in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:432–441. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.2.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shimanuki Y, Takahashi K, Cui R, et al. Role of serum vascular endothelial growth factor in the prediction of angiogenesis and prognosis for non-small cell lung cancer. Lung. 2005;183:29–42. doi: 10.1007/s00408-004-2521-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaya A, Ciledag A, Gulbay BE, et al. The prognostic significance of vascular endothelial growth factor levels in sera of non-small cell lung cancer patients. Respir Med. 2004;98:632–636. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2003.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han H, Silverman JF, Santucci TS, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression in stage I non-small cell lung cancer correlates with neoangiogenesis and a poor prognosis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2001;8:72–79. doi: 10.1007/s10434-001-0072-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fontanini G, Faviana P, Lucchi M, et al. A high vascular count and overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor are associated with unfavourable prognosis in operated small cell lung carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:558–563. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ishii H, Yazawa T, Sato H, et al. Enhancement of pleural dissemination and lymph node metastasis of intrathoracic lung cancer cells by vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGFs) Lung Cancer. 2004;45:325–337. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2004.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Savai R, Langheinrich AC, Schermuly RT, et al. Evaluation of angiogenesis using micro-computed tomography in a xenograft mouse model of lung cancer. Neoplasia. 2009;11:48–56. doi: 10.1593/neo.81036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takayama K, Ueno H, Nakanishi Y, et al. Suppression of tumor angiogenesis and growth by gene transfer of a soluble form of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor into a remote organ. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2169–2177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kabbinavar FF, Wong JT, Ayala RE, et al. The effect of antibody to vascular endothelial growth factor and cisplatin on the growth of lung tumors in nude mice [abstract] Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res. 1995;36:488. Abstract 2906. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sandler A, Gray R, Perry MC, et al. Paclitaxel-carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2542–2550. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schiller JH, Harrington D, Belani CP, et al. Comparison of 4 chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:92–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelly K, Crowley J, Bunn PA, Jr, et al. Randomized phase III trial of paclitaxel plus carboplatin versus vinorelbine plus cisplatin in the treatment of patients with advanced non– small-cell lung cancer: a Southwest Oncology Group trial. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3210–3218. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.13.3210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scagliotti GV, De Marinis F, Rinaldi M, et al. Phase III randomized trial comparing 3 platinum-based doublets in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4285–4291. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.02.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fossella F, Pereira JR, von Pawel J, et al. Randomized, multinational, phase III study of docetaxel plus platinum combinations versus vinorelbine plus cisplatin for advanced nonsmall- cell lung cancer: the TAX 326 study group. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3016–3024. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reck M, von Pawel J, Zatloukal P, et al. Phase III trial of cisplatin plus gemcitabine with either placebo or bevacizumab as first-line therapy for nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer: AVAil. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1227–1234. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.5466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel JD, Hensing TA, Rademaker A, et al. Phase II study of pemetrexed and carboplatin plus bevacizumab with maintenance pemetrexed and bevacizumab as first-line therapy for nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waples JM, Auerbach M, Steis R, Boccia RV, Wiggans RG. A phase II study of oxaliplatin and pemetrexed plus bevacizumab in advanced non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer (An International Oncology Network study, #I-04-015) [abstract] J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(suppl):19018. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reynolds C, Barrera D, Vu DQ, et al. An open-label, phase II trial of nanoparticle albumin bound paclitaxel (nab-paclitaxel), carboplatin, and bevacizumab in first-line patients with advanced non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [abstract] J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(suppl):7610. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sweeney CJ, Miller KD, Sissons SE, et al. The antiangiogenic property of docetaxel is synergistic with a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody against vascular endothelial growth factor or 2-methoxyestradiol but antagonized by endothelial growth factors. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3369–3372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pasquier E, Andre N, Braguer D. Targeting microtubules to inhibit angiogenesis and disrupt tumour vasculature: implications for cancer treatment. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2007;7:566–581. doi: 10.2174/156800907781662266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hotchkiss KA, Ashton AW, Mahmood R, Russell RG, Sparano JA, Schwartz EL. Inhibition of endothelial cell function in vitro and angiogenesis in vivo by docetaxel (Taxotere): association with impaired repositioning of the microtubule organizing center. Mol Cancer Ther. 2002;1:1191–1200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vacca A, Ribatti D, Iurlaro M, et al. Docetaxel versus paclitaxel for antiangiogenesis. J Hematother Stem Cell Res. 2002;11:103–118. doi: 10.1089/152581602753448577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grant DS, Williams TL, Zahaczewsky M, Dicker AP. Comparison of antiangiogenic activities using paclitaxel (taxol) and docetaxel (taxotere) Int J Cancer. 2003;104:121–129. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lynch TJ, Brahmer J, Fischbach N, et al. Preliminary treatment patterns and safety outcomes for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) from ARIES, a bevacizumab treatment observational cohort study (OCS) [abstract] J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:8077. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller VA, O’Connor P, Soh C, Kabbinavar F. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase IIIb trial (ATLAS) comparing bevacizumab (B) therapy with or without erlotinib (E) after completion of chemotherapy with B for first-line treatment of locally advanced, recurrent, or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [abstract] J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(18S):LBA8002. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.3983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]