Abstract

The present study examined the association between cumulative exposure to suicide attempts and deaths and suicidal behavior in a sample of 61 professional firefighters. On average, firefighters reported 13.1 (SD=16.6) exposures over the course of their lifetime. Cumulative exposure to suicide attempts and deaths was positively correlated with suicidal behavior (r = 0.38, p = 0.004). Moreover, firefighters with 12+ exposures were more likely to screen positive for risk of suicidal behavior (OR = 7.885, p = 0.02). Additional research on the potential impact of cumulative exposure to suicide attempts and deaths on firefighters’ health and safety is needed.

Keywords: Suicide Contagion, Suicidal Behavior, Trauma

There are currently around 1.1 million firefighters in the United States (National Fire Protection Association, 2015). These brave men and women routinely respond to life-threatening situations, such as fires, motor-vehicle accidents, and medical emergencies, including suicide attempts and deaths (Corneil et al., 1999; Stanley et al., 2015). While the prevalence of death by suicide among firefighters is not currently known, there is growing concern that firefighters may be at increased risk for suicidal behavior due to: (1) multiple instances of suicide clustering among firefighters during the past five years (Finney et al., 2015); (2) recent survey findings indicating high rates of suicidal behavior among firefighters (Stanley et al., 2015); and (3) prior research suggesting that firefighters are at elevated risk for mental health conditions known to increase risk for suicide and suicidal behavior (e.g., Corneil et al., 1999; North et al., 2002).

An additional risk factor for suicidal behavior that has only recently begun to be explored among firefighters is exposure to suicide attempts and deaths (Stanley et al., 2015). The Interpersonal Theory of Suicide suggests that cumulative exposure to suicide attempts and death should increase firefighters’ risk for suicidal behavior by increasing their acquired capability for suicide (Joiner, 2005, Van Orden et al., 2010). Acquired capability can be defined as increased tolerance of physical pain as well as decreased fear of death and/or bodily harm (Joiner, 2005; Nock et al., 2006). Consistent with the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide, there is substantial evidence that repeated exposure to painful and provocative experiences (e.g., nonsuicidal self-injury, exposure to suicide) is associated with both acquired capability for suicide and suicidal behavior (e.g., Stanley et al., 2015; Van Orden et al., 2010; Willoughby et al., in press).

Prior research suggests that 7–47% of individuals in the general population have been exposed to at least one suicide death (e.g., Cerel et al., 2013, 2015; Crosby & Sacks, 2002; Leonard & Flinn, 1972) and that 19–64% have been exposed to at least one suicide threat or attempt (Cerel et al., 2013; Leonard & Flinn, 1972; Randall et al., 2015). Furthermore, multiple studies suggest that exposure to suicide attempts and deaths increases risk for suicidal behavior (Cerel et al., 2015; Pitman et al., 2014; Stanley et al., 2015; Van Orden et al., 2010). Cerel and colleagues (2015) found that 47% of veterans had known someone that had died by suicide at some point during their lifetime. Moreover, veterans that knew someone that had died by suicide were approximately twice as likely to have diagnosable depression (OR = 1.92) and anxiety (OR = 2.37). They were also significantly more likely to report suicidal ideation (9.9% vs. 4.3%).

Of most relevance to the current study, Stanley and colleagues (2015) recently examined the effects of exposure to suicide attempts and deaths on firefighters’ risk for suicidal behavior. This study found that 92% of firefighters had responded to a suicide attempt on the job, and that 88% of firefighters had responded to a suicide death on the job. In addition, having ever responded to a suicide attempt (OR = 2.73) and having ever responded to a suicide death (OR = 1.71) were both associated with suicidal ideation. History of responding to a suicide death was also associated with increased risk for suicide attempts (OR = 2.00). Thus, Stanley et al.’s important study demonstrated for the first time that a single occupational exposure to a suicide attempt or death is associated with increased risk for suicidal behavior among firefighters.

Objective and Hypothesis

To date, the association between exposure to suicide attempts and deaths and risk for suicidal behavior among firefighters identified by Stanley and colleagues (2015) has not been independently replicated. In addition, several other important questions concerning the relationship between exposure to suicide attempts and death and risk for suicidal behavior among firefighters remain unanswered. For example, it is not currently known if firefighters’ cumulative exposure to suicide attempts and deaths (i.e., their total “dose” of exposure to suicide attempts and deaths) is associated with suicidal behavior, as Stanley et al. (2015) only reported if participants had “ever” responded to a suicide attempt or death (i.e., suicide exposure was dichotomized as present/absent). However, given the high rates of endorsement of occupational exposure to suicide attempts (92%) and deaths (88%) reported by Stanley et al. (2015), it seems likely that many firefighters (especially those that provide emergency medical services) have likely been exposed to numerous suicide attempts and deaths; however, the potential impact of cumulative exposure to suicide attempts and deaths on firefighters’ risk for suicidal behavior has not yet been assessed. Consistent with the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide (Joiner, 2005, Van Orden et al., 2010), we hypothesized that greater cumulative lifetime exposure to suicide attempts and deaths would be associated with greater risk for suicidal behavior in firefighters.

Another key question that has not yet been studied among firefighters is whether cumulative exposure to suicide attempts and deaths is predictive of suicidal behavior above and beyond perceived closeness to the victim, as prior research suggests that perceived closeness to victims of death by suicide is associated with depression, anxiety, prolonged grief, and self-identified survivor status (Cerel et al., 2013, 2015). Thus, it is possible that exposure to suicide attempts and deaths among individuals that firefighters are psychologically close with (e.g., family members, friends, co-workers) might have a greater impact on their risk for suicidal behavior than occupational exposures to suicide attempts and deaths from individuals that firefighters have never met before. The only prior study to examine suicide exposure among firefighters (i.e., Stanley et al., 2015) did not consider the potential impact of non-work related suicide exposures (e.g., exposure to suicide attempts or deaths by family members, friends, or colleagues). Consistent with the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide, which suggests that overall cumulative exposure to suicide attempts and deaths is critical for the development of acquired capability (e.g., Joiner, 2005), we hypothesized that cumulative exposure to suicide attempts and deaths would predict suicidal behavior above and beyond perceived psychological closeness to the victim. Notably, this hypothesis is consistent with a recent study of suicide contagion in adolescents that found that personally knowing victims did not substantially alter the impact of suicide exposure on adolescents’ risk for suicidal behavior (Swanson & Colman, 2013).

Methods

Study Design

The data for the current study were collected as part of a study aimed at developing a standard operating procedure (SOP) for suicide postvention in fire service (Gulliver et al., in press). Specifically, as part of the SOP development and refinement process, we recruited 61 firefighters to participate in focus groups aimed at providing us with feedback concerning potential barriers to implementing the proposed SOP we had developed in order to further refine and improve this product (Gulliver et al., in press). Six focus groups were conducted in three large U.S. fire departments (two focus groups per department) that had strong peer support programs, but did not yet have a suicide postvention SOP in place. Prior to participating in the focus groups, participants were asked to complete a brief battery of questionnaires that included the measures used in the current study.

Participants

A total of 61 firefighters were recruited from three different U.S. fire departments to participate in the current study. To be included in the study, participants had to have been a firefighter at some point during their life and willing to learn about suicide postvention procedures and practices. Exclusion criteria included: (1) inability to complete the study procedures as required; (2) impairment or distress at the time of the assessment due to psychosis, intoxication, organic impairment, or suicidal behavior that required immediate clinical attention; or (3) current involvement in litigation related to occupational exposure to traumatic events in relation to their years of fire service (Gulliver et al., in press).

Approximately 75% of the sample was male. In addition, 23% of the sample was Hispanic/Latino, 10% of the sample was Black/African American, and 72% of the sample was Caucasian. For comparison, approximately 6% of all U.S. firefighters are female, 10% are Hispanic/Latino, and 10% are Black/African American (U.S. Bureau of Labor, 2015). On average, participants were 47 years of age (SD = 7.0). Firefighters from a variety of different ranks participated in the study, including Line Duty Firefighters (54%), Lieutenants (16%), Captains (10%), Battalion Chiefs (7%), Staff Chiefs (2%), Fire Marshals (7%), and Administrators (5%).

Measures

Suicidal behavior was assessed with the Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R; Osman et al., 2001), a brief and reliable measure of suicidal behavior (i.e., suicidal ideation, plans, and attempts) that has demonstrated excellent sensitivity (93%) and specificity (95%) in prior research (Osman et al., 2001). Consistent with Osman and colleagues (2001), scores of 7 or higher were used to classify participants as screening positive for suicide risk.

Exposure to suicide attempts and deaths was assessed with the following question: “Approximately how many times in your lifetime have you witnessed or learned about a suicide attempt or completion?” If participants indicated that they had been exposed to one or more suicide attempts or deaths, they were asked to provide additional details about their exposures (up to 4), including the nature of their relationship with the victim (e.g., “patient/on call responded to,” “relative,” “friend,” “firefighter coworker,” “acquaintance”), how close they were to the victim (0 = “distant,” 3 = “very close”), and whether they had sought treatment after the exposure. Participants were also asked to briefly describe the exposure had affected them most.

Results

Suicidal Behavior

Consistent with the findings reported by Stanley et al. (2015), rates of suicidal behavior were elevated in this sample of firefighters. Specifically, 41% of firefighters in this sample endorsed lifetime suicidal ideation; 11% endorsed suicidal ideation during the past year; 8% endorsed a lifetime suicide plan; and 12% screened positive for being at significant risk for suicide (SBQ-R ≥ 7; Osman et al., 2001). Scores on the SBQ-R were skewed (2.479) and kurtotic (4.284). Accordingly, continuous SBQ-R scores were log transformed prior to analysis. Log transformation improved both skewness (.952) and kurtosis (.006) values for SBQ-R scores.

Types of Exposure to Suicide Attempts and Deaths

Among the four exposures that firefighters provided additional details about, 34.8% (n = 87) of these exposures were occupational exposures to suicide attempts and deaths that occurred while firefighters were responding to calls; 34.4% (n = 86) were exposures to suicide attempts and deaths that involved firefighter co-workers; 13.6% (n = 34) were exposures to suicide attempts and deaths that involved friends; 10% (n = 25) were exposures to suicide attempts and deaths that involved relatives; and 7.2% (n = 18) were exposures to suicide attempts and deaths that involved acquaintances (categories were not mutually exclusive). A stepwise logistic regression model was conducted to examine if cumulative exposure to these different types of suicide exposure (scores ranged from 0–4) was predictive of screening positive on the SBQ-R; however, none of the exposure types were found to be significantly associated with suicide risk in this model (all p’s > .05). A follow-up analysis in which each type of suicide exposure was dichotomized (i.e., present/absent) was also non-significant (all p’s > .05).

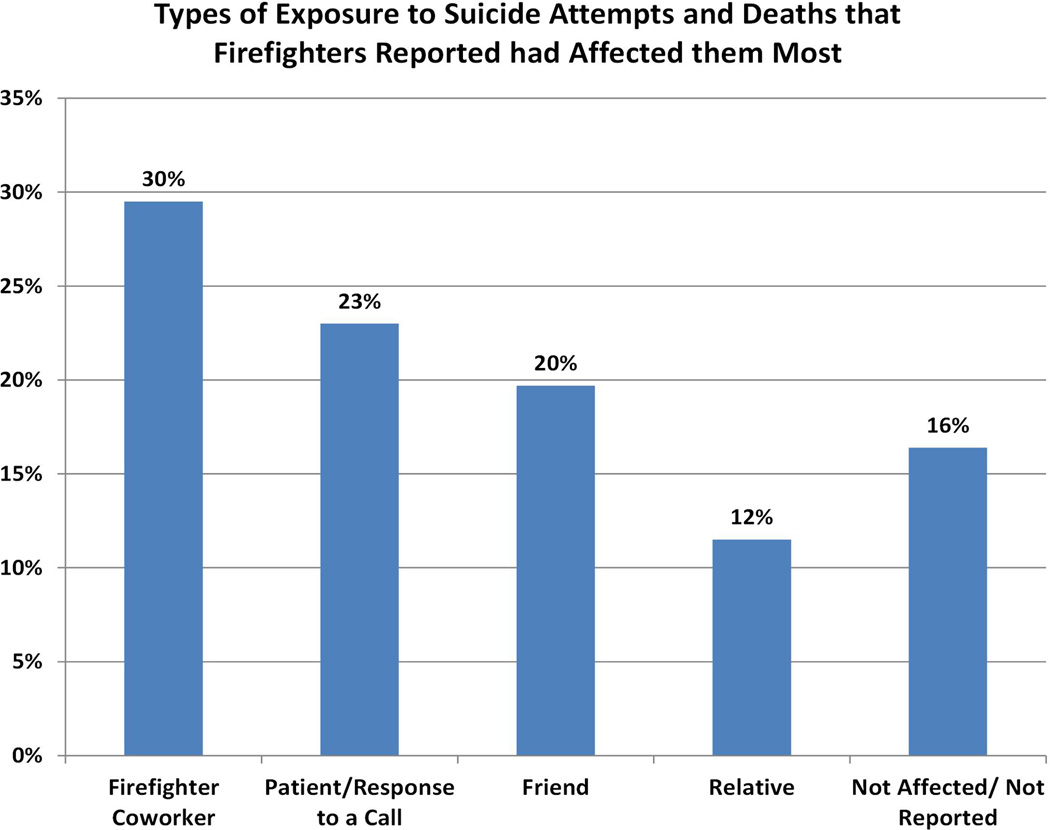

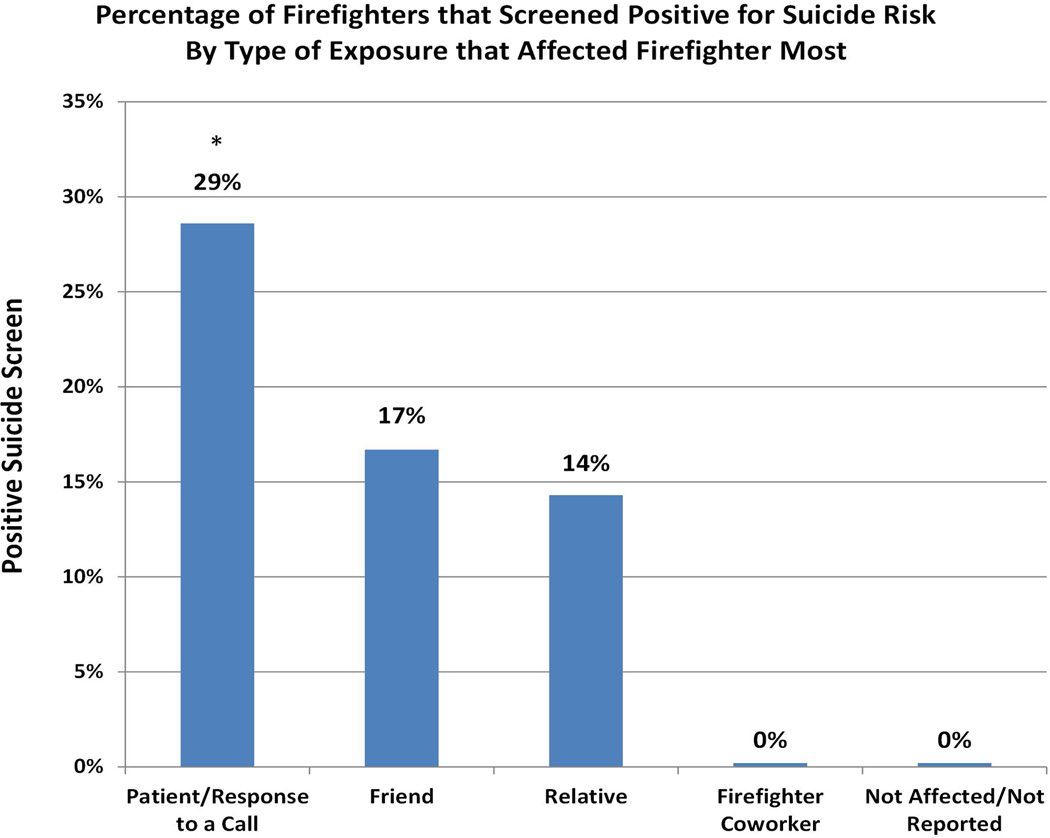

Firefighters were also asked to describe the exposure that had affected them most. As can be seen in Figure 1, firefighters reported that they had been most affected by suicide attempts and deaths by fellow firefighters (30%), followed by suicide attempts and deaths during occupational calls (23%), suicide attempts and deaths by friends (20%), and suicide attempts and deaths by relatives (12%). Approximately 16% of firefighters indicated that they had not been significantly affected by suicide exposures and did not complete this part of the assessment. A stepwise logistic regression model revealed that occupational exposure to suicide attempts and deaths while on duty was the only type of exposure that was associated with increased risk for suicidal behavior (OR = 5.867, p = .04; Nagelkerke R2 = .14; “not affected/not reported” was the referent category in this model). As can be seen in Figure 2, approximately, 29% of firefighters who reported that they had been most strongly affected by an occupational exposure to a suicide attempt or death while on the job screened positive for suicide risk on the SBQ-R.

Figure 1.

The Different Types of Exposures to Suicide Attempts and Deaths that Firefighters Reported Had Affected Them the Most

Figure 2.

The Percentage of Firefighters that Screened Positive for Suicide Risk by Type of Exposure that Affected Them Most.

*p < .05.

Perceived Closeness to Victim

Perceived closeness to the victims was indexed in two ways for the purposes of the current analyses: maximum closeness (i.e., the highest closeness score reported across the four reported incidents) and average closeness (i.e., the average closeness score across the four reported incidents). In contrast with expectations, neither maximum closeness (r = −0.04, p = .78), nor average closeness to the victim (r = −0.02, p = .91) was associated with SBQ-R scores.

Cumulative Exposure to Suicide Attempts and Deaths

All firefighters examined (i.e., 100%) reported exposure to at least one suicide attempt or death. On average, firefighters reported 13.1 (SD=16.6) exposures to suicide attempts and deaths over the course of their lifetime. Because cumulative exposure to suicide attempts and deaths was positively skewed (3.38) and kurtotic (13.951), we transformed this variable by recoding scores of 21 or higher (n = 7) as 21 prior to conducting the correlation analyses. Following this transformation, the exposure to suicide attempts and deaths scores variable was normalized (M = 9.61; SD = 6.18; range = 1–21; skewness = 0.627; kurtosis = −0.668). As expected, exposure to suicide attempts and deaths was positively correlated with SBQ-R scores (r = 0.38, p = 0.004).

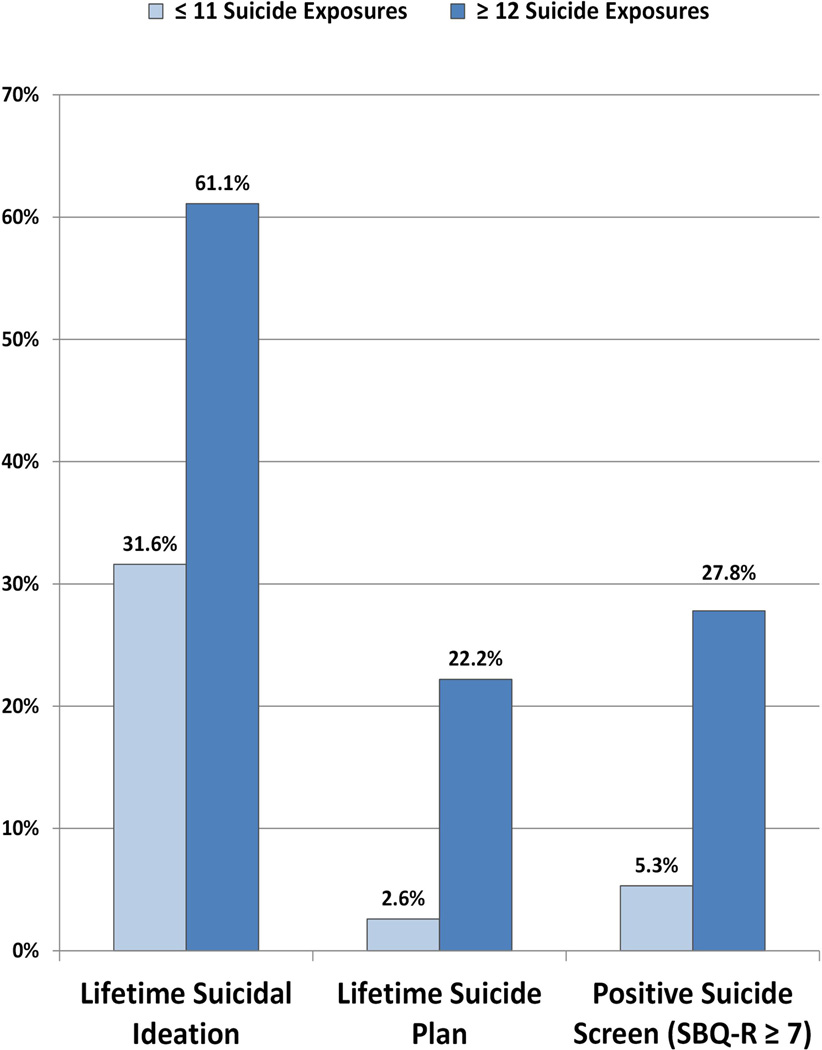

A receiver operator characteristic (ROC) analysis identified a cut-off score of 12 or higher as the optimal cut-score for predicting positive screens (≥7) on the SBQ-R (AUC = 0.723). As can be seen in Figure 3, firefighters with 12 or more exposures were significantly more likely to endorse lifetime suicidal ideation [61.1% vs 31.6%; χ2 = 4.401(1), p = 0.036], lifetime suicide planning [22.2% vs 2.6%; χ2 = 5.765(1), p = 0.016], and to screen positive for suicide risk on the SBQ-R [27.8% vs 5.3%; χ2=5.661(1), p = 0.017]. A logistic regression confirmed that 12 or more exposures had a robust effect on screening positive for suicide risk on the SBQ-R (OR = 7.885, p = 0.02; Nagelkerke R2 = .19). Moreover, this effect remained statistically significant (OR = 8.030, p = 0.04) when “having been most affected by an occupational exposure to a suicide attempt or death on the job” (OR = 7.829, p = 0.03) and “average perceived closeness to the victim” (OR = 1.526, p = 0.62) were included in the model. The latter model accounted for 31% of the variance in screening positive on the SBQ-R.

Figure 3.

The Cumulative Effects of Exposure to Suicide Attempts and Deaths on Firefighters’ Risk for Suicidal Behavior.

Treatment Utilization

Despite the high rate of exposure to suicide attempts and completions observed in the current study (i.e., 100% of firefighters examined), only 13% of firefighters reported that they had ever sought treatment following an exposure to a suicide attempt or completion, and only 5% of firefighters reported that they had sought out treatment more than once following exposure to a suicide attempt or completion.

Discussion

The present study confirms an earlier report by Stanley and colleagues (2015) that rates of exposure to suicide attempts and deaths appear to be substantially elevated among firefighters relative to the general population. Specifically, 92% of firefighters in Stanley et al.’s study reported exposure to suicide attempts and 88% reported exposure to suicide deaths. Similarly, the present study found that 100% of the firefighters examined reported exposure to suicide attempts and/or suicide deaths. While the present study and the study by Stanley et al. (2015) did not include any non-firefighters for comparative purposes, it is clear that the rates of exposure reported by firefighters are substantially higher than those observed among non-firefighter samples, where rates have generally ranged from 7–64% (e.g., Cerel et al., 2013, 2015; Crosby & Sacks, 2002; Leonard & Flinn, 1972; Randall et al., 2015).

The present study also provides the first direct evidence that firefighters are exposed to a very high number of suicide attempts and deaths (M = 13.1) over the course of their lifetimes, and that cumulative exposure to suicide attempts and deaths is associated with increased risk for suicidal behavior among firefighters. This finding is highly consistent with both the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide (Van Orden et al., 2010) and recent work demonstrating an association between exposure to suicide attempts and deaths (examined categorically) and suicidal behavior in other trauma-exposed populations (e.g., Cerel et al., 2015), including firefighters (e.g., Stanley et al., 2015). Unfortunately, the current study was not large enough to enable us to examine which specific types of occupational exposures to suicide attempts and deaths might be most strongly associated with suicidal behavior. However, anecdotal evidence collected from this study as well as through our clinical work with firefighters suggests that occupational exposures involving personally witnessing deaths by suicide, having direct or extended contact with bodies of victims that have died by suicide, and witnessing adolescents or children that have died by suicide are likely to be particularly challenging incidents for firefighters to cope with.

Given the high rate of exposure to suicide identified among firefighters in the present study as well as the strong association observed between cumulative exposure to suicide attempts and suicidal behavior, additional research on the impact of exposure to suicide attempts and deaths on firefighters’ health and safety is clearly warranted. In particular, the findings from the present study suggest that large, prospective research studies are needed to quantify the specific types of occupational exposures that are most likely to impact firefighters’ risk for suicidal behavior in order to facilitate future screening and prevention efforts.

Contrary to expectations, the current study found that perceived closeness to victims of suicide attempts and deaths was unrelated to risk for suicidal behavior in the current study. This finding contrasts with prior research that suggests that perceived closeness to victims of death by suicide is associated with depression, anxiety, prolonged grief, and self-identified survivor status (Cerel et al., 2013, 2015). Our findings are, however, consistent with findings from a prospective study of suicide contagion in adolescents that found that personally knowing victims of death by suicide did not significantly alter the impact of suicide exposure on suicidality (Swanson & Colman, 2013).

Limitations

The present findings should be considered within the context of several limitations, including small sample size, reliance on self-report, and cross-sectional design. Thus, while these findings suggest that cumulative exposure to suicide attempts and deaths may be an important risk factor for future suicidal behavior in firefighters, the cross-sectional design of the current study precludes us from being able to draw such causal inferences. Furthermore, given that the present study is the first to demonstrate an association between cumulative exposure to suicide attempts and deaths and suicidal behavior in firefighters, these findings should be considered preliminary until they are independently replicated, preferably using a longitudinal design.

Summary and Implications

The findings from the present study indicate that, despite the high rates of exposure to suicide attempts and deaths that were observed in the present study, remarkably few of the firefighters that we studied had ever sought out treatment following exposure to a suicide attempt or death. Given the robust association observed between cumulative exposure to suicide attempts and deaths and risk for suicidal behavior observed in this study, recent efforts to develop guidelines for suicide postvention in fire service (Gulliver et al., in press) and to increase firefighters’ utilization of behavioral health treatments are clearly warranted. The findings from the present study further suggest that additional research aimed at better understanding the potential impact of cumulative exposure to suicide attempts and deaths on firefighters’ health and safety is warranted. The finding that firefighters who were most strongly affected by occupational exposures to suicide attempts and deaths were at greatest risk for suicidal behavior appears to be a particularly important finding to study further.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Award (EMW2012FP00243) to Dr. Gulliver entitled “Developing Standard Operating Procedures for Suicide in Fire Service.” Dr. Kimbrel was supported by a Career Development Award (IK2 CX000525) from the Clinical Science Research and Development Service of the Department of Veterans Affairs’ (VA) Office of Research and Development. Special thanks to Grace Carpenter, Elisa Flynn, Amruta Mardikar, Cindy Zavodny, the International Association of Fire Fighters (IAFF), and to our firefighter participants for their assistance in helping us to conduct this research project. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the VA, FEMA, or the United States government.

References

- Swanson SA, Colman I. Association between exposure to suicide and suicidality outcomes in youth. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2013;185:870–877. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.121377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerel J, van de Venne JG, Moore MM, Maple MJ, Flaherty C, Brown MM. Veteran exposure to suicide: Prevalence and correlates. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2015;179:82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerel J, Maple M, Aldrich R, van de Venne J. Exposure to suicide and identification as survivor: Results from a random-digit dial survey. Crisis. 2013;34:413–419. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corneil W, Beaton R, Murphy S, Johnson C, Pike K. Exposure to traumatic incidents and prevalence of posttraumatic stress symptomatology in urban firefighters in two countries. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 1999;4:131–141. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.4.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosby AE, Sacks JJ. Exposure to suicide: Incidence and association with suicidal ideation and behavior. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2002;32:321–328. doi: 10.1521/suli.32.3.321.22170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finney EJ, Buser SJ, Schwartz J, Archibald L, Swanson R. Suicide prevention in fire service. The Houston Fire Department model. Aggression & Violent Behavior. 2015;21:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Gulliver SB, Pennington ML, Leto F, Cammarata C, Ostiguy W, Zavodny C, Flynn EJ, Kimbrel NA. Death Studies. In the wake of suicide: Developing guidelines for suicide postvention in fire service. (in press, a) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard CV, Flinn DE. Suicidal ideation and behavior in youthful nonpsychiatric populations. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1972;38:366–372. doi: 10.1037/h0032916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE. Why people die by suicide. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- National Fire Protection Association. The United States Fire Service Fact Sheet. 2015. [Accessed June 8, 2015]. http://www.nfpa.org/research/reports-and-statistics/the-fire-service. [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Joiner TE, Jr, Gordon KH, Lloyd-Richardson E, Prinstein MJ. Non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents: Diagnostic correlates and relation to suicide attempts. Psychiatry Research. 2006;144(1):65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North CS, Tivis L, McMillen JC, Pfefferhaum B, Spitznagel EL, Cox J, Nixon S, Bunch KP, Smith EM. Psychiatric disorders in rescue workers after the Oklahoma City bombing. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:857–859. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.5.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman A, Bagge CL, Gutierrez PM, Konick LC, Kopper BA, Barrios FX. The Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R): Validation with clinical and non-clinical samples. Assessment. 2001;8:443–454. doi: 10.1177/107319110100800409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitman A, Osborn D, King M, Erlangsen A. Effects of suicide bereavement on mental health and suicide risk. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1:86–94. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70224-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall JR, Nickel NC, Colman I. Contagion from peer suicidal behavior in a representative sample of American adolescents. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2015;186:219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley IH, Hom MA, Hagan CR, Joiner TE., Jr Career prevalence and correlates of suicidal thoughts and behaviors among firefighters. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2015;187:163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor. [Accessed June 8, 2015];Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey. http://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat11.htm.

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, Joiner TE., Jr The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychological Review. 2010;117:575–600. doi: 10.1037/a0018697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willoughby T, Heffer T, Hamza CA. The link between nonsuicidal self-injury and acquired capability for suicide: A longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. doi: 10.1037/abn0000104. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]