SUMMARY

SDM in emergency medicine has the potential to improve the quality, safety, and outcomes of ED patients. Given that the ED is the gateway to care for patients with a variety of illnesses and injuries, SDM in the ED is relevant to numerous healthcare disciplines. We conducted a patient-centered one-day conference to define and develop a high-priority, timely research agenda. Participants included researchers, patients, stakeholder organizations, and content experts across many areas of medicine, health policy agencies, and federal and foundation funding organizations. The results of this conference published in this issue of Academic Emergency Medicine will provide an essential summary of the future research priorities for SDM to increase quality of care and patient-centered outcomes.

Case Vignette

A 6-year-old otherwise healthy girl is brought to the emergency department (ED) by her parents after waking up at 3 a.m. saying that her tummy hurts. She had not eaten dinner the evening before because of stomach pain, but seemed better after being given acetaminophen and falling asleep in her bed. She has not vomited and has had no diarrhea, though when asked where she hurts she points to her periumbilical region. On examination, she is interactive and appears well, has normal vital signs, and is afebrile. She is mildly tender in the periumbilical region and right lower quadrant without guarding or rebound tenderness and otherwise has a normal examination. The clinician communicates her concern for appendicitis with the parents and patient and orders ibuprofen and a focused right lower quadrant ultrasound. Approximately 1 hour later, imaging results are available and indicate that the appendix was not visualized. The patient is re-examined. She says she feels better, her abdominal pain is nearly gone, and there is only mild residual tenderness to deep palpation in the periumbilical region and both lower quadrants.

Case discussion

The primary clinical decision that needs to be made here is one of diagnostic testing: does this patient need an abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan or further observation to determine if the pain resolves on its own or recurs and worsens? The physician could make this decision unilaterally without taking into account the patient’s or parent’s wishes. Alternatively, the physician could allow the patient/parent’s voice to be heard by intentionally employing shared decision making (SDM). A SDM conversation could begin by acknowledging that a clinical decision, with more than one reasonable option, needs to be made. The available management options, the pros and cons of each, and the factors influencing the decision could be explained to the parents. In this case, the equivocal nature of the repeat abdominal examination, the child’s improving symptoms over time, and the probability of the pain resolving on its own could be discussed, along with the logistics of a CT scan, the small but relevant risk of radiation in a young child, the potential for incidental findings, and the feasibility of a return ED visit within 24 hours if her pain recurs or worsens. Critical throughout this process is for the clinician to create an environment that is conducive to safe and open dialogue, question-asking, and deliberation with the family, as well as a willingness to make the decision on behalf of the parents, if they wish. This SDM process can be done informally, via unstructured dialogue, or more formally, using a patient decision aid. The focus of the consensus conference on SDM was to develop a research agenda around scenarios such as this, to explore conditions under which clinicians can and should engage patients and surrogates in SDM in the ED, approaches and tools to facilitate the creation and measurement of a SDM conversation, and health policy to support implementation of evidence that supports patient centered approaches to care in the ED setting.

CURRENT STATE OF SHARED DECISION MAKING

Quality Healthcare is Patient-Centered

In 1988, at a meeting of the Picker Institute, the term “patient-centered care” was first used to emphasize the need for providers and healthcare systems to shift their focus away from disease and back to patients and their families.1 The term refocuses care away from the medical model of disease and back to understanding the experience of illness, addressing patients’ needs and matching treatments to their values. In its landmark report in 2001, “Crossing the Quality Chasm,” the Institute of Medicine called for all healthcare providers to commit to a shared vision of improving care across six domains. In this model, quality healthcare is safe, effective, patient-centered, timely, efficient, and equitable.2 In this same report, patient-centered care is defined as “respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values, and care that ensures that patient values guide all clinical decisions.”

Patient-Centered Care Involves Shared Decision Making

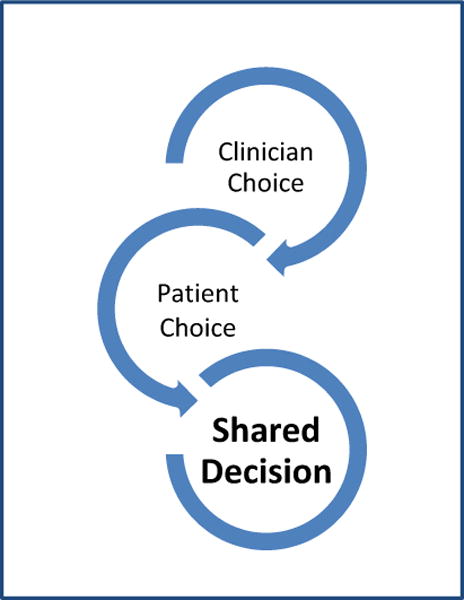

The process by which the optimal decision may be reached with a patient at a diagnostic or therapeutic crossroads is SDM. It involves, at minimum, a clinician and the patient, although other members of the healthcare team or friends and family members may be invited to participate (Figure 1). In SDM, both parties share information: the clinician offers options and describes the potential harms and benefits of each choice, and the patient expresses his or her preferences and values (Table 1). Each participant is thus armed with a better understanding of the relevant factors and shares responsibility for deciding how to proceed. According to the Informed Medical Decisions Foundation, SDM is “a collaborative process that allows patients and their providers to make healthcare decisions together, taking into account the best scientific evidence available, as well as the patient’s values and preferences.”3 SDM incorporates both providers’ expert knowledge and patients’ rights to be fully informed of the potential benefits and harms of all care options. The process empowers patients to make individualized care decisions, while allowing providers to feel confident in the care they are prescribing.4 Although there are some clinical pathways or scenarios in which there is clearly a single effective and appropriate decision pathway, for many management decisions there are multiple options equally supported by the weight of evidence. SDM enables patients and care providers to define the best possible options for the particular case at hand.

Figure 1.

Shared Decision Making as Collaborative Process

Table 1.

Clinician’s versus Patient’s Expertise

| Clinician Expertise | Patient Expertise |

|---|---|

| Diagnosis | Experience of illness |

| Disease etiology | Social circumstances |

| Prognosis | Attitude to risk |

| Treatment options | Values |

| Outcome possibilities | Preferences |

Patient-centered tools that facilitate SDM, known as decision aids, now exist for a variety of clinical scenarios; in addition, scales have been developed to measure patient involvement in decision making and the effects of many of these decision aids have been tested in practice.5–7 A 2014 Cochrane Review of decision aids showed that explicit values clarification exercises improve informed values-based choices.8 While the effect size of decision aids varies across studies, their use has clearly been shown to increase patient involvement and patient-provider communication and improve knowledge and realistic perceptions of outcomes. There do not appear to be adverse effects on health or patient satisfaction. Despite the obvious benefits of this approach, the majority of medical decisions remained uninformed.9,10

Shared Decision Making is Understudied in the Emergency Department (ED)

Despite a wealth of endorsements and research on decision aids in the outpatient setting, little work has been done specific to SDM in the ED. A recently published systematic review of SDM in emergency medicine suggests that patients may benefit from the use of decision aids in this environment.11 Moreover, two recent surveys of emergency physicians revealed there to be substantial support for SDM, with physicians believing there to be more than one reasonable management option for over 50% of their patients.12,13 Moreover, 92% thought that engaging patients in SDM would reduce medically unnecessary testing. While SDM has become the standard of care for many medical treatments, the ED is unique in many ways14; accordingly, SDM in this setting needs to consider many contextual factors. One of the few trials of a decision aid in the ED focused on cardiac stress testing in patients at low risk for acute coronary syndrome because it is associated with high false-positive test results, unnecessary downstream procedures, and increased cost. Use of a decision aid in ED patients with chest pain increased patients’ knowledge and engagement in decision making and decreased the rate of observation unit admission for stress testing.15 In addition to the unique environmental challenges and time pressures of the ED, engaging patients in SDM when they are unstable or critically ill presents its own challenges.

CONFERENCE PLANNING

Academic Emergency Medicine (AEM) has supported 16 Consensus Conferences since 2000 to define and prioritize research agendas across a range of topics pertinent to clinical emergency medicine resulting in a median of 22 topic-related projects and a median project-related grant award of $20 million per Consensus Conference.16 The AEM Editorial Board selects a proposal 2 to 3 years before the Consensus Conference occurs. In May 2013, the topic of SDM was selected for the 2016 AEM Consensus Conference. The first year of planning was focused on identifying essential subtopics and key opinion leaders for those foci, as well as potential funding mechanisms to support the Consensus Conference. The second year of planning focused on fund-raising and grant writing, while the third year was devoted to monthly breakout group meetings, development of key research questions for each subgroup, engagement of keynote speakers and panels, and production of the initial manuscript drafts and discussion points for the conference day. A key distinguishing feature of the 2016 AEM Consensus Conference compared with prior years was the concerted engagement of patient representatives in the monthly teleconference meetings in the year prior to the conference and on the conference day.

Annual meetings of organizations centered on SDM, including the International Patient Decision Aid Standard (IPDAS) Collaboration, the Society for Participatory Medicine, the Society for Medical Decision Making, as well as the International Shared Decision Making Conference, have focused primarily on outpatient or preventive health conditions. To our knowledge, the 2016 AEM Consensus Conference was the first meeting that focused on the role of SDM in acute emergency conditions. The goal of the AEM consensus conference also differs from these annual academic meetings as the primary objective is to develop a research agenda around shared decision making in emergency medicine, as opposed to presenting the latest research. To achieve this goal, we engaged participants in real-time, face-to-face small group discussions to create a roadmap to achieve these objectives.

The 2016 AEM consensus conference, “Shared Decision Making in the Emergency Department: Development of a Policy-Relevant Patient-Centered Research Agenda,” was designed to fill this void and to stimulate researchers and educators in emergency medicine to recognize, investigate, and translate the impact of SDM on patient-oriented outcomes in the ED. The executive and steering committee consisted of international experts including physicians, nurses, and social scientists (Table 1) who jointly planned the conference via regular teleconference calls and multiple in-person planning meetings.

The executive committee identified six core ED SDM themes that required further research: 1) diagnostic testing; 2) policy, 3) dissemination/implementation and education, 4) development and testing of SDM approaches and tools in practice, 5) palliative care and geriatrics, and 6) vulnerable populations and limited health literacy (Table 2). Each breakout group drafted a research agenda using existing literature, content expertise, and input from the executive committee. The conference included internationally recognized keynote speakers, interactive breakout sessions led by content experts, as well as an audience that included key stakeholders from federal funding agencies, patient organizations, and national and international foundations that support SDM. We funded scholarships for patients, advocacy organizations, and trainees from underrepresented groups to ensure access to the conference for these specific groups.

Table 2.

2016 AEM Consensus Conference Organizers

| Name | Institution | Role |

|---|---|---|

| Corita R. Grudzen, MD, MSHS | New York University | Chair |

| Erik P. Hess, MD, MSc | Mayo Clinic | Co-Chair |

| Christopher R. Carpenter, MD, MSc | Washington University in St. Louis | Co-Chair |

| Jennifer Kryworuchko, PhD, RN, CNCC | University of British Columbia | Executive Committee |

| Annie LeBlanc, PhD | Executive Committee | |

| Ali S. Raja, MD, MBA, MPH | Harvard University | Executive Committee |

| Richard Thomson, BM, BCh | Executive Committee | |

| Jeffrey A. Kline, MD | Indiana University | Editor-in-Chief, Academic Emergency Medicine |

| Timothy Jang, MD | University of California-Los Angeles | Guest Editor, Consensus Conference Proceedings |

| Manish N. Shah, MD | University of Wisconsin | Guest Editor, Original Contributions |

| Stacey Roseen | Academic Emergency Medicine | Journal Manager |

| Taylor Bowen | Academic Emergency Medicine | Technical Editor and Peer-Review Coordinator |

| Melissa McMillian, CNP | Society for Academic Emergency Medicine | Grants and Foundation Manager |

| Senem Suzek | New York University | Grant Manager |

Role of Trainees

There were 6 trainees who were selected on a competitive basis for participation in and travel to the consensus conference. Each trainee was provided the opportunity to participate in the consensus process in 1 of the 6 breakout sessions prior to the conference via monthly teleconference calls. On the day of the conference, the trainees facilitated the logistics of the consensus process for each of the breakout sessions, recorded the consensus discussions, and ensured that descriptive data were collected on each of the participants at the conference.

Role of Patient Representatives

This was the first AEM consensus conference to engage patient and caregiver representatives in developing the research agenda in each of the 6 SDM themes requiring further research. The goal of engaging patient and caregiver representatives was to have the voice of the patient guide and influence the research agenda to ensure that the needs of the patient, a (and arguably the primary) stakeholder of an emergency department visit, are taken into consideration in future investigations. Our goal was to have at least 1 patient or caregiver representative meaningfully participate in each breakout session both prior to and on the day of the conference and be included in a breakout session manuscript as co-author. In prior experience, we had observed that having a patient representative with experience participating in a consensus process or, if less experienced, an advocate who could facilitate communication of the patient’s perspective on an as needed basis was critical.17 As such, we identified a diverse group of patient representatives who had prior experience participating in a consensus process, experience representing the perspective of a particular community or people group in the context of research, or who had participated in prior ED research as a patient or caregiver representative. Each of the manuscripts in this issue of AEM that outline high priority research topics for each breakout session includes a patient or caregiver representative as co-author.

CONFERENCE AIMS

We convened a comprehensive, one-day consensus conference to develop a research agenda for SDM in emergency medicine. The specific objectives of the conference were to: 1) critically examine the state of the science on SDM in emergency medicine, and to identify opportunities, limitations, and gaps in knowledge and methodology; 2) develop a consensus statement that prioritizes emergency conditions for research in SDM that will change practice and identify the most effective methodological approaches; and 3) identify and build collaborative research networks among patients, investigators, and other key stakeholders to study the use of SDM in emergency medicine using a patient-centered model of care that will be competitive for federal funding.

To examine the state of the science and identify gaps (Aim 1), our steering committee reviewed the current literature on decision aids for emergency conditions, identified state of the art research methodologies to translate clinical decision rules and develop decision aids for emergency medicine providers and patients, identified key emergency conditions and/or sub-populations where SDM is likely to be effective, applied contemporary theories of implementation science to identify and overcome SDM barriers, and formulated strategies for increasing SDM in vulnerable populations (e.g., lower health literacy, limited English proficiency, older adults).

To develop a consensus statement (Aim 2), the breakout group leaders developed a group of priority emergency conditions and populations for SDM, identified contextual barriers to the use of decision aids in the ED environment, as well as potential facilitators, and identified methodological standards for SDM research in emergency medicine.

To build collaborative research networks competitive for future funding (Aim 3), we identified already existing collaborations to study the use of SDM in emergency medicine using a patient-centered model of care, built upon these collaborative networks to be competitive for National Institutes of Health (NIH), Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), as well as foundation and international funding, and used the conference breakout groups to foster long-term collaborative and mentor-mentee relationships to generate scholarship in SDM research.

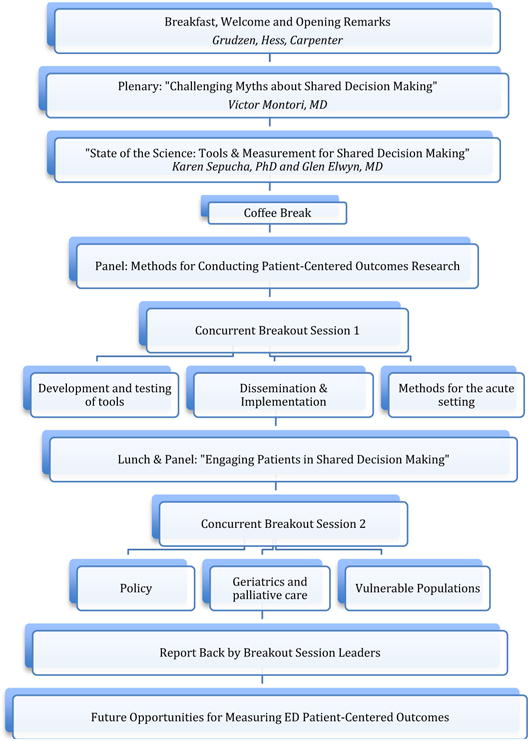

CONFERENCE AGENDA (Figure 1)

The conference occurred on May 10, 2016 immediately prior to the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine annual meeting in New Orleans LA. Dr. Jeff Kline, AEM editor-in-chief delivered a welcome address reviewing the overriding objective of AEM to elevate the human condition in times of emergency. The conference co-chairs Drs. Corita Grudzen, Christopher Carpenter, and Erik Hess summarized existing knowledge of ED SDM, introduced the conference planning committee, and summarized the day’s agenda. Victor Montori, MD Professor of Internal Medicine at Mayo Clinic delivered the first keynote address. A world-renowned opinion leader in favor of pragmatic, meaningful SDM, Dr. Montori elaborated on the potential of SDM to improve both the experience and the outcomes for patients during an episode of emergency care.18 Karen Sepucha, PhD and Maggie Breslin delivered the second keynote address reviewing contemporary understanding of shared decision making measurement and adaptation of medical information to patient-friendly decision aids.19 Following the morning breakout sessions, Patty and David Skolnik showed their documentary film “From Tears to Transparency” about the medical miscommunications and tragic outcome that occurred with their son Michael.20 Following the afternoon breakout sessions, diverse federal and foundation representatives reviewed future funding opportunities. The funding panel included Marcus Escobedo, MPA from the John A. Hartford Foundation, Jeremy Brown, MD from the NIH Office of Emergency Care Research, Brendan Carr, MD from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Patrick Dunn, PhD from the American Heart Association, and Christopher Gayer, PhD from the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute.21

Figure 2.

Conference Day Agenda

Table 3.

Breakout Groups

| Group Number | Group Title | Group Leaders | Institutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Shared decisions in diagnostic testing | Tyler Barrett, MD | Vanderbilt University |

| 2 | Policy implications for shared decision making | Brandon Maughan, MD | University of Pennsylvania |

| 3 | Dissemination/Implementation of and Education for shared decision making | Hemal Kanzaria, MD Esther Chen, MD |

University of California San Francisco |

| 4 | Testing Shared Decision Making in Practice | Edward Melnick, MD | Yale University |

| 5 | Palliative care and Geriatric emergency shared decision making | Jennifer Kryworuchko, PhD, RN, CNCC Timothy Platts-Mills, MD, MSc |

University of British Columbia University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill |

| 6 | Vulnerable populations and limited health literacy shared decision making | Lynne Richardson, MD Richard Griffey, MD, MPH |

Icahn School of Medicine New York Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine |

Table 4.

2016 AEM Consensus Conference Patient Representatives

| Name | Home |

|---|---|

| Amy Berman, BS, RN | New York City, NY |

| Rebecca Blackwell, PhD, RN, BSc | New York City, NY |

| Juanita Booker-Vaughns EdD, MaEd | Los Angeles, CA |

| Hiwber Flores | New York City, NY |

| Constance Kizzie-Gillett MA | Los Angeles, CA |

| Bill Vaughan | Falls Church, VA |

| Cheryl Walsh | Stockbridge, GA |

| Gail Weingarten, MA BA | Villanova, PA |

| Pluscedia (“Ms. Plus”) Williams | Los Angeles, CA |

| Angela Young-Brinn MBA | Los Angeles, CA |

Acknowledgments

Funding for the conference was made possible [in part] by grant number 1R13HS024172-01 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ); grant number 1R13MD010171-01 from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities and contract #0876 from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). The views expressed in written conference materials or publications and by speakers and moderators do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the Department of Health and Human Services or PCORI; nor does mention of trade names, commercial practices, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

References

- 1.Gerteis M. Picker/Commonwealth Program for Patient-Centered Care Through the patient’s eyes: understanding and promoting patient-centered care. 1st. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making–pinnacle of patient-centered care. New Engl J Med. 2012;366:780–1. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1109283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mulley AG, Trimble C, Elwyn G. Stop the silent misdiagnosis: patients’ preferences matter. BMJ. 2012;345:e6572. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e6572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edwards A, Elwyn G. Shared Decision-Making in Health Care: Achieving Evidence-Based Patient Choice. 2nd. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harter M, van der Weijden T, Elwyn G. Policy and practice developments in the implementation of shared decision making: an international perspective. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes. 2011;105:229–33. doi: 10.1016/j.zefq.2011.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elwyn G, O’Connor A, Stacey D, et al. Developing a quality criteria framework for patient decision aids: online international Delphi consensus process. BMJ. 2006;333:417. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38926.629329.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stacey D, Legare F, Col NF, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;1:CD001431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braddock CH, 3rd, Edwards KA, Hasenberg NM, Laidley TL, Levinson W. Informed decision making in outpatient practice: time to get back to basics. JAMA. 1999;282:2313–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.24.2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Covinsky KE, Fuller JD, Yaffe K, et al. Communication and decision-making in seriously ill patients: findings of the SUPPORT project. The Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:S187–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flynn D, Knoedler MA, Hess EP, et al. Engaging patients in health care decisions in the emergency department through shared decision-making: a systematic review. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19:959–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2012.01414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanzaria HK, Brook RH, Probst MA, Harris D, Berry SH, Hoffman JR. Emergency physician perceptions of shared decision-making. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22:399–405. doi: 10.1111/acem.12627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Probst MA, Kanzaria HK, Frosch DL, et al. Perceived Appropriateness of Shared Decision-making in the Emergency Department: A Survey Study. Acad Emerg Med. 2016;23:375–81. doi: 10.1111/acem.12904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hess EP, Grudzen CR, Thomson R, Raja AS, Carpenter CR. Shared Decision-making in the Emergency Department: Respecting Patient Autonomy When Seconds Count. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22:856–64. doi: 10.1111/acem.12703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hess EP, Knoedler MA, Shah ND, et al. The chest pain choice decision aid: a randomized trial. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5:251–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.964791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishijima DK, Dinh T, May L, Yadav K, Gaddis GM, Cone DC. Quantifying federal funding and scholarly output related to the academic emergency medicine consensus conferences. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;89:176–81. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanzaria HK, McCabe AM, Meisel ZM, et al. Advancing Patient-centered Outcomes in Emergency Diagnostic Imaging: A Research Agenda. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22:1435–46. doi: 10.1111/acem.12832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kunneman M, Montori VM, Castaneda-Guarderas A, Hess EP. What Is Shared Decision Making (And What Is It Not)? Acad Emerg Med. 2016 doi: 10.1111/acem.13065. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Graffeo C, Carpenter CR, Breslin M, Sepucha K. State of the Science: Tools and Measurement for Shared Decision Making in the Emergency Department. Acad Emerg Med. 2016 doi: 10.1111/acem.13071. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alliance for Patient Safety. 2016 (Accessed May 26, 2016 at http://www.allianceforpatientsafety.org/skolnik.php.)

- 21.Dodd KW, Berman A, Brown J, et al. Funding research in emergency department shared decision making: a summary of the 2016 Academic Emergency Medicine Consensus Conference Discussion. Acad Emerg Med. 2016 doi: 10.1111/acem.13063. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]