Abstract

This is a study of neuroAIDS in sub-Saharan Africa, involving 266 Zambian adults infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), clade C. All HIV+ participants were receiving combination antiretroviral therapy (CART), and were administered a comprehensive neuropsychological (NP) test battery covering seven ability domains that are frequently affected by neuroAIDS. The battery was developed in the U.S. but has been validated in other international settings and has demographically-corrected normative standards based upon 324 healthy Zambian adults. Compared to the healthy Zambian controls, the HIV+ sample performed worse on the NP battery with a medium effect size (Cohen's d = 0.64). 34.6 % of the HIV+ individuals had global NP impairment and met criteria for HIV associated neurocognitive disorder (HAND). The results indicate that the Western-developed NP test battery is appropriate for use in Zambia and can serve as a viable HIV and AIDS management tool.

Keywords: HIV, HAND, Neuropsychological performance, Zambia

Palabras Clave: VIH, HAND, Rendimiento neuropsicologico, Zambia

Introduction

HIV infection affects the Central Nervous System (CNS) leading to a decline in the neuropsychological (NP) performance of many people infected with HIV [1–4]. HIV induced cognitive and behavioural abnormalities detected by neuropsychological tests are collectively referred to as HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND). HAND has three main subdivisions relative to the degree of cognitive impairment and associated changes in everyday life: Asymptomatic Neurocognitive Impairment, Mild Neurocognitive Disorder, and HIV-Associated Dementia. Asymptomatic Neurocognitive Impairment is diagnosed by at least 1 standard deviation (SD) below the mean of demographically adjusted scores in at least two cognitive areas (attention-working memory, speed of information processing, language, abstraction-executive functioning, complex perceptual motor skills, memory, including learning and recall, complex motor skills), but without any apparent changes in activities of daily living. Mild Neurocognitive Disorder features the same criteria as outlined for Asymptomatic Neurocognitive Impairment, but with at least mild changes in activities of daily living. HIV-Associated Dementia is diagnosed when an HIV patient performs at least 2 SD below the demographically corrected normative means in at least two cognitive areas, as well as having marked difficulty in activities of daily living due to cognitive impairment resulting from HIV infection. The milder forms of HAND do not, however, typically progress to HIV-Associated Dementia. In fact, there has been a decline in the prevalence of HIV associated Dementia (HAD) owing to the introduction of combination antiretroviral therapy (CART). This phenomenon was first recognised in the developed world in the mid-1990s [5–8].

Understanding HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders is vital in managing HIV and AIDS because they impact on the clinical management and every day functioning of the HIV+ individuals [5, 6, 9]. The impact of HAND may vary depending on sociodemographic and biological factors such as the geographic specific HIV subtypes, or clades, although the influence of subtypes on neuropathology is subject to further research [9–13].

About 6.2 million people in sub-Saharan Africa are on CART, and Zambia is listed among the five countries providing universal access to CART in this region [14–16]. Therefore, investigating the manifestations of the HIV and AIDS pandemic in this region in the era of CART is essential. Zambia has HIV-1 clade C subtype similar to half of all the HIV infections worldwide, including Central, East and Southern Africa [17]. About 1,100,000 people are infected with HIV in Zambia. It is estimated that 13 percent of adults in Zambia aged 15–49 are infected with HIV [18, 19].

Neuropsychological assessments are important in diagnosing and categorizing the effects of HIV on CNS malfunctioning, especially because milder forms of CNS disturbances may not show in neuroimaging techniques such as Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). Moreover, in resource limited settings, neuroimaging technology is not readily available, thus making NP tests that are affordable and easy to administer, a more viable option [6]. However, the lack of normative data and culturally appropriate NP tests, have hampered this vital area of research in sub-Saharan Africa [5, 8, 14, 20]. Another common difficulty is related to ascertaining how HIV patients' levels of competence in everyday life can be ascertained. This information is important because changes in everyday functions are required in diagnosing symptomatic HAND [21]. Traditional NP instruments used for detecting such changes are based on self- report questionnaires and checklists such as the Activities of Daily Living (ADL) questionnaire and the Patients Assessment of Own Functioning (PAOFI) questionnaire. It has been noted that at best such measures used in identifying functional impairment have some face validity as measures of everyday functions. This has led to some scholars proposing the use of laboratory-based measures of functional ability [22]. It is argued that functional measures such as Medication Management Test are more accurate than self-report measures [23]. The Medication Management Test measures an individual's ability to dispense and adhere to medication instructions based on a hypothetical prescription that is similar to therapies that are used in HIV treatment. However, this approach has raised concerns based on lack of normative data and long administration times.

Although sub-Saharan Africa accounts for 23 million of the 34 million people living with HIV and AIDS globally, numerous empirical studies investigating the effects of HAND have mainly been carried out in developed countries with HIV-1 subtype B [6, 13, 14, 16, 24].

Attempts at establishing patterns of HAND in sub-Saharan Africa, have frequently employed brief neuropsychological test batteries and instruments such as the International HIV dementia Scale which are less sensitive tools [12, 24–27]. Comprehensive NP batteries are more sensitive, hence necessitating the standardization of multi-domain test batteries such as the HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center, University of California San-Diego (HNRC) battery which was used in this study. Zambia does not have specific tests to measure HAND but has adapted the HNRC neuropsychological test battery and developed norms corrected for age, education, and gender [28].

Objectives

The aim of this study was to determine the sensitivity of the above mentioned NP test battery, using Zambian norms, in distinguishing a large cohort of HIV positive adult participants on CART, relative to healthy HIV− control participants in urban Zambia. Furthermore, we sought to examine NP impairment levels and to detect the impact of HIV related disease characteristics on NP performance. Factors associated with everyday functioning, employment status, and activities of daily living are also considered.

We hypothesised that the Western developed NP test battery with Zambian norms would show that clade C HIV infection negatively affects neurocognitive functioning, and that HIV associated disease characteristics and everyday functioning of the HIV+ would be associated with neurocognitive impairment similar to that observed in Western countries with predominantly clade B HIV.

The current study is important for southern Africa because it utilizes a comprehensive neuropsychological test battery that has been normed for the Zambian population and it examines a large CART experienced HIV+ sample.

The HNRC developed test battery that was employed for the current study has been well tested in various cultures and was further found appropriate for the Zambian culture when it was used in a pilot study and when it was used for developing norms for Zambia [28].

Methods

Participants

The HIV+ sample was drawn from six urban clinics under the Management of the Lusaka District Health Management team clinics in the Zambian capital city of Lusaka: Chilenje, Chipata, Kabwata, Kalingalinga, Matero Main, and Matero Referal clinics. These clinics were chosen as they provide HIV testing services and CART free of charge which allowed for an unobtrusive recruitment of confirmed HIV+ participants.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion

HIV status-All study participants were HIV positive and on CART. Information about HIV and treatment status was based on the participant's medical files.

Education Level- Eligible participants were required to have a minimum of 5 years of formal education. English is the primary language of instruction in the Zambian school system and the NP testing process was performed in English. To screen for the participants' ability to speak and understand English the Zambia Achievement Test was used (ZAT) [29].

Age range- All the participants were required to be between 18 and 65 years of age (conforming to the age range of the HIV− controls who participated in the NP test norming study).

Exclusion

History of Neurological disorders—Individuals with a history of non-HIV related neurological problems such as epilepsy, closed head injury and coma for any reason were excluded from the study. This information was obtained by means of the Neurobehavioural Medical Screen Form which assesses past medical and neurological histories [30].

History of drug abuse—Individuals with a history of drug abuse were excluded from the study. This information was obtained using a structured Substance Use form [31, 32].

Physical disabilities—Individuals with obvious physical disabilities were excluded from the study to minimize on the possibility of test performance requiring motor dexterity being impaired due to the handicap.

The control group for the current study was from previously published Zambia normative study; it comprised 324, healthy Zambian adults who were recruited to provide data for making demographically corrected normative standards adjusted for sex, age and education. Detailed procedures and results of the norming study are reported elsewhere [28].

Procedure

Recruitment of HIV+ participants was carried out with the assistance of nurses at each clinic who identified participants meeting the inclusion criteria. Although no viral sequencing was carried out for the current study, we presume the HIV+ participants' had clade C HIV, which is dominant in Zambia [17]. Once informed consent was obtained, the participants were referred to one of ten Master of Science Neuropsychology students from University of Zambia, for an individual NP examination. These NP test administrators had received extensive training in interviewing, administration and scoring of the test battery used in the study.

The testing process for each participant was about 2 h 30 min. The first part of the testing process involved obtaining the participants' demographic characteristics, medical and psychiatric information based on self-report as well as from the patients' medical records. Administration of the test battery was carried out in a standardized manner for all participants, and they were compensated with Zambian Kwacha Fifty (equivalent to 8 USD) at the end of the NP testing process, as reimbursement for transport and refreshment.

Measures

Cognitive Functioning

Cognitive functioning was measured by means of a comprehensive neuropsychological test battery assessing the seven domains of: Executive Functioning, Working Memory/Attention, Speed of Information Processing, Verbal fluency, Learning, Delayed recall and Motor Function (see Table 1 for listing of individual tests). The test battery is a well-recognized neurocognitive assessment tool, translated into multiple languages and used in various neurobehavioural studies around the world [2, 31, 33, 34] and has been adapted and normed for use in the Zambian adult population. In the adaptation process, some test items such as those on the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised (HVLT-R) were changed to make them more culturally appropriate for Zambia. For instance, all the precious stones in the learning trial of the test were changed to metals that are common in Zambia (copper, iron, lead and zinc). In the recognition trial, steel and bronze were added. The norming process was similar to that used for U.S. normative data. The raw scores were converted to normally distributed scaled scores with a mean of 10 and standard deviation of 3, and then statistically corrected for age, education, gender and rural/urban background. The results of the regression models were then rescaled into demographically corrected T-scores with a mean of 50 and 10 standard deviations [28].

Table 1. T scores based results on HIV− versus the HIV+ on Neuropsychological tests.

| Ability Domain/NP test | HIV− (n = 324) Mean SD) | HIV+ (n = 266) Mean (SD) | Degrees of freedom | t | P | Cohen's d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verbal fluency | ||||||

| Letter fluency | 49.72(9.95) | 45.67(10.86) | 588 | 4.722 | <.001 | 0.39 |

| Animal fluency | 49.37(10.14) | 48.53(10.68) | 588 | .970 | .333 | 0.08 |

| Action fluency | 49.64(9.85) | 44.99(10.77) | 588 | 5.413 | <.001 | 0.50 |

| Fluency mean | 49.56(6.95) | 46.38(7.57) | 588 | 5.302 | <.001 | 0.44 |

| Executive functions | ||||||

| Stroop-color word | 49.49(9.70) | 48.61(10.47) | 578 | 1.059 | .290 | 0.08 |

| Category test errors | 50.02(9.79) | 44.20(8.69) | 587 | 7.642 | <.001 | 0.63 |

| WCST-64 total errors | 50.02(9.84) | 44.56(10.02) | 580 | 6.605 | <.001 | 0.60 |

| Colour trails 2 | 49.63(9.93) | 47.89(9.94) | 588 | 2.111 | .035 | 0.17 |

| Executive mean | 49.84(6.29) | 46.29(6.35) | 588 | 6.785 | <.001 | 0.56 |

| Working memory | ||||||

| PASAT | 50.04(9.71) | 45.88(10.59) | 588 | 4.968 | <.001 | 0.41 |

| WMS-III spatial span | 49.52(9.80) | 42.95(11.69) | 588 | 7.509 | <.001 | 0.61 |

| Working memory mean | 49.78(7.52) | 44.41(8.39) | 588 | 8.189 | <.001 | 0.67 |

| Speed of information processing | ||||||

| WAIS-III Digit symbol | 49.74(9.99) | 43.12(10.35) | 588 | 7.876 | <.001 | 0.66 |

| WAIS-III symbol search | 49.91(10.11) | 43.39(10.74) | 588 | 7.574 | <.001 | 0.62 |

| Trails A | 49.90(9.93) | 46.82(9.42) | 588 | 3.840 | <.001 | 0.32 |

| Color trails 1 | 49.59(10.18) | 48.97(9.14) | 588 | .773 | .440 | 0.06 |

| Stroop color naming | 49.57(10.01) | 47.53(11.04) | 588 | 2.359 | .019 | 0.19 |

| Stroop word naming | 49.57(9.96) | 46.34(10.82) | 587 | 3.767 | <.001 | 0.31 |

| Speed of information processing mean | 49.74(7.03) | 45.96(7.26) | 588 | 6.398 | <.001 | 0.53 |

| Learning | ||||||

| HVLT-R learning | 49.95(10.00) | 44.91(9.21) | 588 | 6.313 | <.001 | 0.52 |

| BVMT-R learning | 50.02(10.22) | 43.49(10.34) | 588 | 7.675 | <.001 | 0.63 |

| Learning mean | 50.00(7.72) | 44.22(8.15) | 587 | 8.816 | <.001 | 0.73 |

| Delayed recall | ||||||

| HVLT—R delay | 49.64(9.99) | 45.88(9.69) | 588 | 4.606 | <.001 | 0.38 |

| BVMT delay | 49.96(10.24) | 44.21(10.17) | 588 | 6.798 | <.001 | 0.56 |

| Delayed recall mean | 50.02(7.83) | 45.01(8.08) | 587 | 7.611 | <.001 | 0.63 |

| Motor function | ||||||

| Grooved Pegboard dominant hand | 49.83(9.99) | 52.53(10.83) | 588 | −3.138 | .002 | −0.26 |

| Grooved Pegboard non-dominant hand | 49.93(10.11) | 51.48(11.70) | 525 | −1.706 | .089 | −0.14 |

| Motor function summary | 49.87(9.20) | 51.95(10.57) | 529 | −2.513 | .012 | −0.21 |

| Global mean | 49.77(5.14) | 46.28(5.66) | 588 | 7.826 | <.001 | 0.64 |

WCST-64 Wisconsin Card Sorting Test-64 card version; PASAT Paced auditory serial addition Test; WMS-III Wechsler Memory Test, Third Edition; WAIS-III Wechsler adult intelligence scale, Third Edition; HVLT-R Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised; BVMT-R Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-Revised. Stroop-Color Word Stroop-Color-Word interference trial

Disease Characteristics

The clinical evaluation and staging of disease development was adopted from the World Health Organization, which classifies HIV based on disease manifestations. This classification is used in many countries with limited resources to determine eligibility for antiretroviral therapy, and does not require a CD4 count. Clinical stages are categorized from 1 through to 4, progressing from primary HIV infection to advanced HIV/AIDS [14, 35]. In this paper, the initial WHO stage was determined at the stage at which antiretroviral therapy was introduced and the current WHO stage is the stage determined at the time of data collection for the current study. AIDS status constituted participants with AIDS and those without AIDS.

Nadir CD4 was taken at the point of the participant's eligibility for CART and Current CD4 taken at the time of data collection for the current study.

Viral load was categorized as “detected” and “undetected”. Viral load was detected at 50 copies/ml.

CART regimen and especially the Efavirenz (EFV)-based regimens have been reported to affect NP performance. Efavirenz (EFV) is a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) approved for treatment of HIV disease. It is potent, generally well tolerated, and can be administered once a day, making it an attractive component of antiretroviral therapy. The most commonly reported adverse experience with EFV is central nervous system (CNS) toxicity, with more than 50 % of HIV patients reporting at least temporary symptoms [36]. In the current study categories were created for those with a regimen including EFV, and those whose regimen did not include EFV.

To compute body mass index (BMI), the height and weight of the HIV+ participants were obtained at the time of data collection for this study by the medical officers in the recruitment clinics.

Activities of Daily Living and Patients Assessment of Own Functioning

Activities of Daily Living (ADL) questionnaire was used to obtain participants' self-reported day-to-day functioning. The Patients Assessment of Own Functioning (PAOFI) questionnaire was used to obtain information of the participants' presence or absence of perceived impairments in performing everyday tasks and activities [27, 37–40].

Ethical Consideration

The study was approved by The University of Zambia Biomedical Research Ethics Committee and also formally approved by Zambia's Ministry of Health and the Lusaka District Health Management Team, which oversees clinics in Lusaka.

Informed consent was obtained from all research participants. Participants had the right to take breaks or withdraw from the study at any time with no penalty incurred. All the data that was recorded was anonymous and arbitrary codes were used for analysis purposes.

Data Management

The raw data obtained from the neuropsychological tests were converted into normalized and demographically corrected T Scores based on data previously collected from 324 healthy Zambians. T-Scores in the normal population have a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10 and were corrected for age, gender, education and urban/rural background. T-Scores were used for analysis in order to correct for known effects of demographic variables on NP performance and thus allowing for comparable analysis across groups based purely on the effects of HIV infection and comorbid infections.

Global Deficit Scores (GDS) were used to determine the neurocognitive impairment levels of the participants. GDS is a means of constructing impairment ratings which uses demographically corrected T scores on a five point scale from normal to severely impaired. A deficit score of 0 is normal performance (T score ≥40), whereas a deficit score of 1 is mild impairment (T score = 35–39), 2 is mild to moderate impairment (T score = 30–34), 3 is moderate impairment (T score = 25–29), 4 is moderate to severe impairment (T score = 20–24), and 5 is severe impairment (T score < 20). Participants were classified as impaired if the average of their deficit scores was ≥0.5 on a particular cognitive domain called Domain Deficit Score (DDS). They were further classified as having Global Impairment if they had an average deficit score ≥0.5 across all tests in the battery [41–43].

Data Analysis

All the data in this study were analyzed using The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20. SPSS was used to summarize participants' demographics and disease characteristics as well as to generate independent sample t-tests for group comparisons, as well as linear and logistic regression analyses of neuropsychological performance of the HIV+ participants and control group.

Results

The current study comprised 40.2 % HIV+ males and 59.8 % HIV+ females. The proportion of males and females was consistent with reports for the general HIV+ population in Zambia (i.e., 40 % males and 60 % females) [19]. All the participants were on CART and their age range was between 21 and 65 years (Mean = 40.67, SD = 8.74). The HIV+ participants had an education range between 5 and 20 years (Mean = 9.9, SD = 2.24). They were slightly older Mean = 40.67(SD = 0.73) than the total HIV− control group Mean = 38.48 (12.80), p = .014 and had less years of formal education compared to the HIV− controls, Mean = 11.02(SD = 2.58) p < .001. However, “normal” age, education and gender effects on the NP tests were controlled by using demographically corrected standard scores (T scores) generated with the large HIV− normative sample.

HIV Status and NP Performance

Summary NP Functioning of the HIV− Controls and HIV+ Participants

Table 1 presents independent t test analyses comparing the NP performance of HIV+ participants and HIV− controls on all the tests individually, and averaged for the seven domains. T scores were used for these analyses.

Results shown in Table 1 indicate that the HIV+ participants performed significantly worse than the HIV− on Executive Functioning, Speed of Information Processing, Working Memory, Learning, Delayed Recall, and Global mean with medium Cohen's d effect sizes, except Motor functioning, where the HIV+ participants were unexpectedly somewhat better (well within the normal range for both groups).

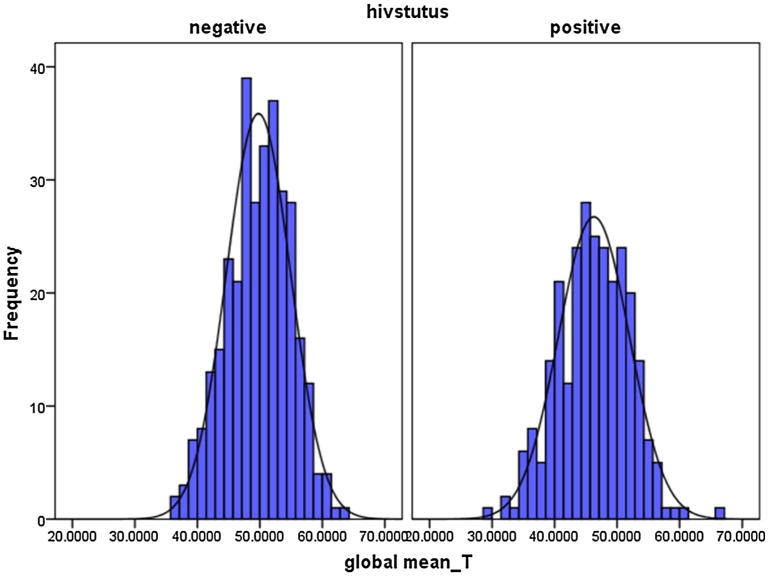

Figure 1 shows the global mean T score on tests across all the seven domains measured by the NP test battery. On average the HIV+ participants performed worse than the HIV− participants with a medium Cohen's d effect size of 0.64.

Fig. 1.

T scores based graphical representation of Global mean T scores HIV− versus the HIV+ on the Neuropsychological Battery

An independent sample t-test using GDS showed that the HIV+ were more impaired (Mean = .460, SD = .50) compared to the HIV− (Mean = .249, SD = .27; t (392.03) = −6.15, p < .001. with a medium effect size of .52 Cohen's d.

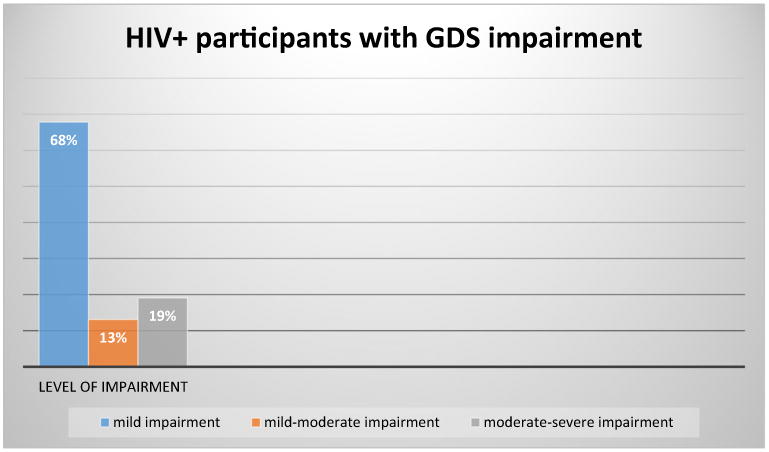

The percentage of HIV+ participants who were impaired (GDS ≥ 0.50) was 34.6 %.

Figure 2 shows the distribution of GDS impairment levels in the HIV+ participants.

Fig. 2.

GDS impairment levels in the HIV+ sample

The majority (68 %) of the impaired HIV+ participants were mildly impaired [GDS = 0.50–0.90]. There were 13 % in the mild to moderate impairment level [GDS = 1.00–1.39] and 19 % of the impaired participants (6.6 % of the total sample) were moderately to severely impaired [GDS ≥ 1.40, consistent with HIV associated Dementia].

Logistic regression analyses were performed to determine if the variables (Table 2); viral load detected/viral load not detected, Current WHO stage, Initial WHO stage, PAOFI scores, ADL scores and employment status could be predicted by GDS impairment or non-impairment status. Independent sample t-test analyses were also carried out for the dichotomous variables (viral load detected/viral load not detected, and With AIDS/Without AIDS) with regard to NP performance. Furthermore, Linear Regression analyses were applied for the continuous variables and those with more than two levels (Current CD4, Nadir CD4, BMI, Current WHO stage and Initial WHO stage). T scores, and GDS impaired or not impaired categorizations were used for these analyses. Linear and logistic regression analyses carried out using T scores and GDS did not yield any statistically significant results. To determine whether CART regimen affected NP performance, a comparison of participants on Efavirenz (EFV) with those whose regimen did not include EFV showed that there were no differences between those on EFV and those that were on regimens that did not include EFV.

Table 2. Outlines the HIV+ participants' disease and treatment characteristics.

| Disease characteristic | Percentage | Mean (SD) | Median |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current CD4 | – | 480.28(242.60) | 461.00 |

| Nadir CD4 | – | 200.45(148.56) | 161.00 |

| Viral load detected | 19.4 | – | – |

| Undetectable Viral load | 80.6 | – | – |

| Current WHO clinical stage | |||

| 1. | 27.14 | – | – |

| 2. | 20.48 | ||

| 3. | 46.18 | ||

| 4. | 6.20 | ||

| Initial WHO clinical stage | |||

| 1. | 78.95 | ||

| 2. | 1.91 | ||

| 3. | 16.27 | – | – |

| 4. | 2.87 | ||

| With AIDS | 52.38 | – | – |

| Without AIDS | 47.62 | – | – |

| CART regimen | |||

| With EFV | 36.3 | – | – |

| Without EFV | 63.7 | – | – |

| BMI | – | 23.3(4.49) | 22.31 |

Independent sample t-tests showed significant differences on T score but not on GDS. Differences observed were in the viral load detected group on Verbal Fluency (Mean = 43.88, SD = 7.30) compared to viral load not detected, Mean = 46.90, SD = 7.45; t (245) = 2.59, p = .012; effect size (.41), as well as on Speed of Information processing mean performance, viral load detected (Mean = 44.09, SD = 7.11), compared to viral load not detected Mean = 46.48, SD = 7.13; t (245) = 2.088, p = .038 effect size (.34). Global mean T scores differences were also statistically significant, Viral load detected (Mean = 44.78, SD = 5.42) compared to Viral load not detected Mean = 46.64, SD = 5.58; t (245) = 2.126, p = .034, effect size (.34). Participants with AIDS also performed worse on Recall mean T (Mean = 43.77, SD = 7.46) than those without AIDS Mean = 46.01, SD = 8.59; t (208) = 2.021, p = .045, effect size (.30).

Discussion

The current study found that clade C HIV infection in Zambia is associated with deficits in neurocognitive functioning. This is consistent with has been found by studies in the Western World where Clade B is predominant. Similar results have also been obtained in other regions inflicted with clade C HIV [1, 12, 34, 44].

Although the 266 participants in the current study were all on CART, they still showed signs of HAND. This could be explained partly by the fact that our sample was comprised of individuals who initiated CART treatment with a relatively low CD4 count. In the current study, the nadir CD4 count of almost all participants was within a low threshold (< 200 cells/ml), which previously has been associated with NP impairment [2, 45].

Sensitivity of the HNRC Western Developed NP Test Battery in Detecting HIV Associated Cognitive Decline

The results suggest that the Western developed NP test battery is a sensitive tool for detecting HAND in HIV+ individuals. The HIV+ were observed to have performed worse than the HIV− on all the domains except Motor functioning.

Negative effects of HIV infection on NP performance were observed on the domains of Executive Functioning, Speed of Information Processing, Working Memory, Learning, Delayed Recall, and Global mean with medium Cohen's d effect sizes. These findings are consistent with that of Gupta et al. [44] in India who reported that in a clade C HIV+ sample, NP domains of Fluency, Learning, Working Memory and Episodic Memory were impaired compared to the HIV− controls. Lawler [46] also reported NP impairments for a clade C HIV+ sample in Botswana in the areas of verbal learning and delayed free recall. Uganda, which has HIV clades A and D, similarly yielded findings that the HIV+ were impaired in Learning, Memory, Speed of Information Processing, Attention and Executive Functioning compared to the HIV− group [14].

Results obtained regarding Motor Functioning were surprising because the HIV+ performed slightly better than the HIV negatives. This finding was somewhat consistent with prior studies which found that performances on the Grooved Pegboard did not show an HIV effect in other African countries of Ethiopia and Uganda [14, 47]. Also in the U.S., reduced HIV effects on the Pegboard task have been found in the CART era, compared to pre-CART era [48]. It is necessary to carry out further research to establish the varying results being obtained in studies pertaining Motor Functioning in the HIV+ population.

Prior research has shown that about 30–50 % of people living with HIV and AIDS are likely to have some neuropsychological decline during the course of their illness [1, 49]. Similarly, our study found that 34.6 % of the HIV infected in Zambia were impaired on the Global Deficit Score. This result is comparable to other studies carried out in sub-Saharan Africa which showed neurocognitive impairment in 38 % of HIV population in Botswana [12], 24 % in South Africa [50, 51], and 31 % in Uganda [10]. In China, 34.2 % of HIV+ subjects were reported to have neuropsychological impairment [30].

NP Performance of the HIV+ Participants in Relation to Disease Characteristics

We predicted that HIV related disease characteristics would be related to cognitive functioning. However, results showed that only viral load was associated with NP performance in the domains of Fluency, Speed of Information Processing and the Global Mean Score where the viral load detected group performed worse than the viral load not detected group. Furthermore, the AIDS group performed worse than the HIV+ without AIDS group on the Recall Mean T score results. Similar to Vance et al., [37] and Lawler et al., [46], nadir and current CD4 count, BMI and initial and current WHO stages were not related to NP performance, possibly because our HIV+ sample all had similarly low nadir CD4, and were on CART with improved CD4 counts and WHO staging; additionally, their BMI levels were not categorically low.The fact that almost everyone in our sample had a similar low nadir CD4 of <200 cells/ml is because, until recently, CART in Zambia was typically initiated for patients who had a CD4 of <200 cells/ml in WHO stage three or four [52, 53]. Consequently, our sample was comprised of individuals with lower nadir CD4 than is reported in other studies, especially those in the West where nadir CD4 has been found to be a consistent predictor of NP functioning. Normally these studies compare those with CD4 of <200 cells/ml to those who had a nadir CD4 of ≥ 200 cells/ml which was not feasible in our study [2, 45].

Relationship Between GDS Impairment Levels, Every Day Functioning and Employment Status

Unlike most Western studies, [31, 37, 54] as well as the results obtained in a study from China [30] that showed strong associations between NP performance and reported everyday functioning, our study showed no such relationship. Our results however, corresponded with a study carried out in Botswana [46], which yielded no significant relationship between NP impairment and self-reports of everyday functioning. It is hypothesized that this could be at least partially a reflection of some culturally irrelevant items on the ADL and PAOFI questionnaires for the Zambian population [46, 55]. It is therefore suggested that more appropriate questionnaires should be developed to measure everyday functioning that is consistent with Zambian cultural roles. Furthermore, other avenues such as the use of the SF-36 test could be explored. Although this test is not targeted at the HIV population it has been used extensively around the world and may be preferred over other measures of self- report such as the Medical Outcomes Study HIV survey (MOS-HIV) in the absence of appropriate norms. Laboratory performance-based measures also could be explored to assess their feasibility in the Zambian context. It has been proposed that where possible, asking a third party who has witnessed the patient performing tasks under specific conditions, could be explored. The challenge of relating neuropsychological performance to real world functioning remains, although some progress has been made [22, 56–58].

The present study has shown that the HNRC comprehensive Western developed neuropsychological test battery with Zambian norms is a relevant tool for measuring neurocognitive deficits in the adult population of Zambia. This is because it was able to correctly distinguish the HIV+ group from the HIV− group in all the domains except Motor functioning. These results are consistent with those previously obtained [28, 33] which showed that the HNRC developed test battery is a sensitive tool regarding detecting NP deficits in HIV positive individuals in Zambia.

Especially given the non-availability of neuroimaging techniques in this resource limited country, we believe it is feasible to administer well normed neuropsychological tests on a selective basis. Measures have been put in place to ensure that provision of this service is sustainable. With the help of NORAD Master Programme, The Norwegian University of Science and Technology, and HNRC at University of California as San Diego, a Master of Science programme in Clinical Neuropsychology was introduced in Zambia. The programme is under the department of Psychiatry and the department of Psychology of the University of Zambia. This has made it possible to continue training neuropsychologists who will be capable of administering and interpreting the results from the test battery.

Conclusion

The study suggests that the comprehensive Western developed NP test battery with Zambian norms is a valid tool for measuring NP performance in Zambia to detect cognitive deficits in HIV+ adults. However, further adaptations and investigations addressing the cultural relevance of the Western Patients Assessment on Own Functioning inventory and Activities of Daily Living questionnaire are required.

Acknowledgments

Gratitude is extended to the staff and patients of the participating clinics for their contributions. The authors also thank the first and second cohort Masters students in clinical neuropsychology at The University of Zambia for their contribution in collecting the data of the healthy sample and the seropositive sample respectively. The study was financially supported by the NOMA funds from The Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD).

Funding The study was financially supported by the NOMA funds from The Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD). Project title: Master of Science in Clinical Neuropsychology—Building expertise to deal with the Neuropsychological challenges of HIV-infection. (Grant No NOMAPRO-2007/10046).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest Norma Kabuba declares that she has no conflict of interest. J. Anitha Menon declares that she has no conflict of interest. Donald R. Franklin Jr. declares that he has no conflict of interest. Robert K. Heaton declares that he has no conflict of interest. Knut A. Hestad declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethical Standards: Ethical Approval All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- 1.Heaton R, Grant I, Butters N, White DA, Kirson D, Atkinson HJ, McCuthchan JA, Taylor M, Kelly MD, Ellis RJ, Wolfson T, Velin RA, Marcotte TD, Hesselink JR, Jernigan TL, Chandler J, Wallace M, Abramason I. The HNRC 500-Neuropsychology of HIV infection at different disease stages. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 1995;1(231):251. doi: 10.1017/s1355617700000230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heaton RK, Clifford DB, Franklin DR, Jr, Woods SP, Ake C, Vaida F, Ellis RJ, Letendre SL, Marcotte TD, Atkinson JH, Rivera-Mindt M, Vigil OR, Taylor MJ, Collier AC, Marra CM, Gelman BB, McArthur JC, Morgello S, Simpson DM, McCutchan JA, Abramson I, Gamst A, Fennema-Notestine C, Jernigan TL, Wong J, Grant I the CHARTER Group. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(3):473–80. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu862. Epub2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reger MA, Martin DJ, Sherwood LC, Strauss G. The relationship between viral load and neuropsychological functioning in HIV-1 infection. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2005;20:137–43. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garrido JM, Alvarez M, Lopez MA. Neuropsychological impairment and gender differences in HIV-1 infection. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008;62:494–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2008.01841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Durvasula RS, Norman LR, Malow R. Current perspectioves on neuropsychology of HIV. In: Pope C, White CRT, Malow R, editors. HIV/AIDS global frontiers in prevention/intervention. New York: Tylor and Francis; 2009. pp. 177–190. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robertson K, Liner J, Heaton R. Neuropsychological assessment of HIV-Infected populations in international settings. Neuropsychol Rev. 2009;19:232–49. doi: 10.1007/s11065-009-9096-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parsons TD, Braaten AJ, Hall CD, Robertson KR. Better quality of life with neuropsychological improvement on HAART. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:11. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sacktor N. The epidemiology of human immunodeficiency virus-associated neurological disease in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Neurovirol. 2002;8(Suppl 2):115–21. doi: 10.1080/13502802901094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gorman AA, Foley JM, Ettenhofer ML, Hinkin CH, Van Gorp WG. Functional consequences of HIV-associated neuropsychological impairment. Neuropsychol Rev. 2009;19(2):186–203. doi: 10.1007/s11065-009-9095-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sacktor N, Wong M, Nakasujja N, Skolasky R, Selnes O, Musisi S, Roberston K, McArthur J, Ronald A, Katabira E. The international HIV dementia scale: a new rapid screening test for HIV dementia. AIDS. 2005;19:1367–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sacktor N, Nakasujja N, Robertson K, Clifford DB. HIV-associated cognitive impairment in sub-Saharan Africa–the potential effect of clade diversity. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2007;3(8):436–43. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lawler K, Mosepele M, Ratcliffe S, Seloilwe E, Nthobatsang R, Steenhoff A. Neurocognitive impairment among HIV-positive individuals in Botswana: a pilot study. J Int AIDS Soc. 2010;13:15 h. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-13-15. www.jiasociety.org/content/13/1/15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maj M, D'Elia L, Satz P, Janssen R, Zaudig M, Uchiyama C, Starace F, Galderisi S, Chervinsky A. Evaluation of two new neuropsychological tests designed to minimize cultural bias in the assessment of HIV-1 seropositive persons: a WHO study. Arch Clin Neuropsych. 1993;8:123–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robertson KR, Nakasujja N, Wong M, Musisi S, Katabira E, Parsons TD, Ronald A, Sacktor N. Pattern of neuropsychological performance among HIV patients in Uganda. BMC Neurol. 2007;7:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-7-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stringer JSA, Zulu I, Stringer EM, Mwango A, Chi BH, Mtonga V, Reid S, Cantrell RA, Bulterys M, Saag MS, Marlink RG, Mwinga A, Ellerbrock TV, Sinkala M. Rapid scale-up of antiretrovial therapy at primary care sites in Zambia-feasibility and early outcomes. JAMA. 2006;296:782–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.7.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meyers A. Neuroloy and the global HIV epidemic. Semin Neurol. 2014;34:70–7. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1372344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jackson H. AIDS Africa—continent in crisis. Harare: SAfAIDS; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 18.UNAIDS. Global Report 2012: AIDSinfo. 2012 http://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/zambia/retrieved 30/04/15.

- 19.Zambia Demographic and Health Survey [ZDHS] 2013–14 https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR304/FR304.pdf retrieved 28/07/15.

- 20.Cysique LA, Brew BJ. Neuropsychological functioning and antiretroviral treatment in HIV/AIDS: a review. neuropsychol Review. 2009;19:169–85. doi: 10.1007/s11065-009-9092-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Antinori A, Arendt G, Becker JT, Brew BJ, Byrd DA, et al. Updated research nosology for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neurology. 2007;69:1789–99. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000287431.88658.8b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heaton RK, Marcotte TD, Mindt MR, Sadek J, Moore DJ, Bentley H, Grant I. The impact of HIV-associated neuropsychological impairment on everyday functioning. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2004;10(03):317–31. doi: 10.1017/S1355617704102130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blackstone K, Moore DJ, Heaton RK, Franklin DR, Woods SP, Clifford DB, Morgello S. Diagnosing symptomatic HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders: self-report versus performance-based assessment of everyday functioning. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2012;18(01):79–88. doi: 10.1017/S135561771100141X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Habib AG, Yakasai AM, Owolabi LF, Ibrahim A, Habib ZG, Gudaji M, Karaye KM, Ibrahim DA, Nashabaru I. Neurocognitive impairment in HIV-1- infected adults in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systemtic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2013;17:e820–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2013.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robertson K, Kumwenda J, Supparatpinyo K, Jiang H, Evans S, Campbell TB, Price RW, Murphy R, Hall C, Marra CM, Marcus C, Berzins B, Masih R, Santos B, Silva MT, Kumarasamy N, Walawander A, Nair A, Tripathy S, Kanyama C, Hosseirnipour M, Montano S, La Rosa A, Amod F, Sanne I, Firnhaber C, Hakim J, Brouwers P the AIDS Clinical Trials Group. A multinational study of neurological performance in antiretroviral Therapy-Naïve HIV-1 infected persons in diverse resource-constrained settings. J Neurovirol. 2011;18(5):438–47. doi: 10.1007/s13365-011-0044-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holguin A, Banda M, Willen EJ, Malama C, Chiyenu KO, Mudenda VC, Wood C. HIV-1 effects on neuropsychological performance in a resource—limited country, Zambia. AIDS Behav. 2011;15:1895–1901. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9988-9. doi:10.10071510461-011-9988-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Potchen MJ, Siddiqi OK, Elafros MA, Theodore WH, Sikazwe I, Kalungwana L, Bositis CM, Birbeck GL. Neuroimaging abnormalities and seizure recurrence in a prospective cohort study of Zambians with human immunodeficiency virus and first seizure. Neurol Int. 2014;6:5547. doi: 10.4081/ni.2014.5547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hestad KA, Menon JA, Serpell R, Kalungwana L, Kabuba N, Mwaba S, Franklin D, Jr, Heaton RK. Demographically corrected neuropsychological test norms from Zambia, Africa. Psychol Assess. 2015 doi: 10.1037/pas0000147. http://dxdoi.org11o.1037/pas0000147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Stemler SE, Chamvu FC, Chart H, et al. Assessing competencies in reading and mathematics in Zambian children. In: Grigorenko E, editor. Multicultural Psyhoeducational Assessment. New York: Springer Publishing company; 2008. pp. 157–85. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heaton RK, Cysique LA, Jin H, Shi C, Yu X, Letendre S, Franklin DR, Jr, Ake C, Vigil O, Atkinson JH, et al. Neurobehavioral effects of human immunodeficiency virus infection among former plasma donors in rural China. J Neurovirol. 2008;14(6):536–49. doi: 10.1080/13550280802378880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heaton RK, Miller SW, Taylor MJ, Grant I. Revised comprehensive Norms for an expanded Halstead Reitan Battery: demographically adjusted neuropsychological norms for African American and Causasian Adults. Luitz FL: Psychol Assess Res Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kabuba N, Menon JA, Hestad K. Moderate alcohol consumption and cognitive functioning in a Zambian population. MJZ. 2011;38:2. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hestad AK, Menon JA, Ngoma M, Franklin DR, Imasiku MI, Kalima K, Heaton RK. Sex differences in the Neuropsycholgical performance as an effect of Human Immunodeficiency Virus infection-A pilot study in Zambia, Africa. Acta Scandinavia. 2012;200(4) doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31824cc225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kanmogne GD, Kuate CT, Cysique LA, Fonsah JY, Eta S, Doh R, Njamnishi DM, Nchindap E, Franklin DR, Jr, Ellis RJ, McCutchan JA, Binam F, Mbanya D, Heaton RK, Njamnshi AK. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders in sub-Saharan Africa: a pilot study in Cameroon. BMC Neurology. 2010;10:60 h. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-10-60. ttp:// www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2377/10/60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.WHO (2013) 2013 www.who.int/gho/hiv/en/Retrieved.

- 36.Clifford DB, Evans S, Yang Y, Acosta EP, Ribaudo H, Gulick RM. Long-term impact of Efavirenz on neuropsychological performance and symptoms in HIV-infected individuals (ACTG5097s) HIV Clin Trials. 2009;10(6):343–55. doi: 10.1310/hct1006-343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vance DE, Fazeli PL, Gakumo CA. The impact of Neuropsychological performance on everyday functioning between older and younger Adults with and without HIV. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2013;24(2):112–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bell MJ, Terhorst L, Bender CM. Psychometric analysis of the patient assessment of own functioning inventory in women with breast cancer. J Nurs Meas. 2013;21(2):320–34. doi: 10.1891/1061-3749.21.2.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rourke SB, Halman MH, Bassel C. Neuropsychiatric correlates of memory-metamemory dissociations in HIV-infection. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1999;21(6):757–68. doi: 10.1076/jcen.21.6.757.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chelune GJ, Lehman RAW. Neuropsychological and personality correlates of patients complaints of disability. In: Goldstein G, Tarter RE, editors. Advances in clinical neuropsychology. New York: Plenum Press; 1986. pp. 95–118. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blackstone K, Moore DJ, Franklin DR, Jr, Clifford DB, Collier AC, Marra CM, Gelman BB, McArthu JC, Morgello SD, Simpson M, Ellis RJ, Atkinson JH, Grant I, Heaton RK for the CHARTER Group. Defining Neurocognitive Impairment in HIV: Deficit Scores versus Clinical Ratings. Clin Neuropsychol. 2012;26(6) doi: 10.1080/13854046.2012.694479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carey C, Woods SP, Gonzalez R, Conover E, Marcotte TD, Heaton RK. Predictive validity of Global Deficit Scores in detecting neuropsychological impairment in HIV infection. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2004;26(3):307–19. doi: 10.1080/13803390490510031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ettenhofer ML, Hinkin CH, Castellon SA, Durvasula R, Ullman J, Lam M, Foley J. Aging, neurocognition, and medication adherence in HIV infection. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17(4):281–90. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31819431bd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gupta JD, Satishchandra P, Gopukumar K, Wilkie F, Waldrop-Valverde D, Ellis R, Ownby R, Subbakrishna DK, Desai A, Kamat A, et al. Neuropsychological deficits in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 clade C-seropositive adults from South India. J Neurovirol. 2007;13(3):195–202. doi: 10.1080/13550280701258407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Muñoz-Moreno JA, Fumaz CR, Ferrer MJ, Prats A, Negredo E, Garolera M, Núria Pérez-Álvarez N, Moltó J, Gómez G, Clotet B. Nadir CD4 cell count predicts neurocognitive impairment in HIV-infected patients. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2008;24(10):1301–7. doi: 10.1089/aid.2007.0310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lawler K, Kealeboga J, Mosepele M, Ratcliffe SJ, Cherry C, Seloilwe E, Steenhoff AP. Neurobehavioral Effects in HIV-Positive Individuals Receiving Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART)in Gaborone, Botswana. PLoS One. 2011;6(2):e17233. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Clifford DB, Mitike MT, Mekonnen Y, Zhang J, Zenebe G, Melaku Z, Zewde A, Gessesse N, Wolday D, Messele T, et al. Neurological evaluation of untreated human immunodeficiency virus infected adults in Ethiopia. J Neurovirol. 2007;13(1):67–72. doi: 10.1080/13550280601169837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heaton RK, Franklin DR, Ellis RJ, Mc Cutchan JA, Letendre SL, Le Blanc S, Collier AC. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders before and during the era of combination antiretroviral therapy: differences in rates, nature, and predictors. J Neurovirol. 2011;17(1):3–16. doi: 10.1007/s13365-010-0006-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thames AD, Foley JM, Panos SE, Singer EJ, El-Saden S, Hinkin CH. Cognitive reserve masks neurobehavioral expression of human immodeficiency virus-associated neurological disorder in older patients. Neurobehav HIV Med. 2011;3:87–93. doi: 10.2147/NBHIVS25203retrieved25/09/2013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ganasen KA, Fineham D, Smit TK, Seedat S, Stein D. Utility of the HIV Dementia Scale (HDS) in identifying HIV dementia in a South African sample. J Neurol Sci. 2008;269:62–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Joska JA, Westgarth-Taylor J, Myer L, et al. Characterization of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders among individuals starting antiretroviral therapy in South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9744-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zambia Ministry of Health. Adult and Adolescent Antiretroviral Therapy Protocols 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zambian National AIDS Council. National guidelines for management and care of patients with HIV/AIDS. Lusaka: Printech Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marcotte TD, Lazzaretto D, Scott JC, Roberts E, Woods SP, Letendre S. Visual attention deficits are associated with driving accidents in cognitively-impaired HIV-infected individuals. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2006;28(13):28. doi: 10.1080/13803390490918048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Raper JL. The medical management of HIV disease. In: Durham JD, Lashley FR, editors. The person with HIV/AIDS. 4th. New York: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Albert SM, Weber CM, Todak G, Polanco C, Clouse R, McElhiney M, Marder K. An observed performance test of medication management ability in HIV: relation to neuropsychological status and medication adherence outcomes. AIDS Behav. 1999;3(2):121–8. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shahriar J, Delate T, Hays RD, Coons SJ. Commentary on using the SF-36 or MOS-HIV in studies of persons with HIV disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marcotttee TD, Scott JC, Kamat R, Heaton RK. Neuropsychology and the prediction of everyday functioning. In: Marcottee TD, Grant I, editors. Neuropsychology of everyday functioning. Guilford Press; New York: 2010. pp. 5–38. [Google Scholar]