Abstract

Liver cancer stem cells (CSCs) may contribute to the high rate of recurrence and heterogeneity of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). However, the biology of hepatic CSCs remains largely undefined. Through analysis of transcriptome microarray data, we identify a long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) called lncBRM, which is highly expressed in liver CSCs and HCC tumours. LncBRM is required for the self-renewal maintenance of liver CSCs and tumour initiation. In liver CSCs, lncBRM associates with BRM to initiate the BRG1/BRM switch and the BRG1-embedded BAF complex triggers activation of YAP1 signalling. Moreover, expression levels of lncBRM together with YAP1 signalling targets are positively correlated with tumour severity of HCC patients. Therefore, lncBRM and YAP1 signalling may serve as biomarkers for diagnosis and potential drug targets for HCC.

Liver cancer stem cells (CSCs) may contribute to the high rate of recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma. Here, the authors show that the long coding RNA, LcnBRM, regulates the self-renewal of liver CSCs and tumour initiation through binding to BAF complex thereby activating YAP1.

Liver cancer stem cells (CSCs) may contribute to the high rate of recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma. Here, the authors show that the long coding RNA, LcnBRM, regulates the self-renewal of liver CSCs and tumour initiation through binding to BAF complex thereby activating YAP1.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most prevalent subtype of liver cancer and ranks the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths1. Liver transplantation and surgical resection are the first-line treatment for HCC. Even after surgical resection, the 5-year survival rate of HCC patients remains poor, owing to high recurrence rates. The high rate of recurrence and heterogeneity are the two major features of HCC2. Cancer stem cells (CSCs) have been defined to be a small subset of cancer cells within the tumour bulk, exhibiting self-renewal and differentiation capacities3. CSCs may well contribute to tumour initiation, metastasis, recurrence, as well as drug resistance3,4,5. Liver CSCs can be enriched by some defined surface markers6,7,8. Several recent studies reported that Wnt/β-Catenin, Notch, Hedgehog, transforming growth factor-β, and phosphatase and tensin homologue signalling pathways are implicated in the regulation of liver CSC self-renewal9,10,11. However, the biology of liver CSCs remains largely elusive.

Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) are transcripts longer than 200 nucleotides without protein-coding potentials12. Accumulating evidence shows that lncRNAs are involved in physiological and pathological progresses, including embryonic development, organ formation, X chromatin inactivation, tumorigenesis and so on refs 12, 13, 14, 15. LncRNAs can recruit transcription factors and remodelling complexes to modulate gene expression11 and they can also interact with messenger RNAs and regulate the stability of mRNAs. Several recent studies demonstrated that lncRNAs can associate with some important proteins and modulate their functions16,17,18. LncRNAs have been reported to be implicated in tumour formation and metastasis16,17,19. However, how lncRNAs regulate the self-renewal of liver CSCs remains largely unknown.

Yes-associated protein (Yap) and transcriptional co-activator with PDZ-binding domain motif (Taz) are transcriptional cofactors that shuttle between the cytoplasm to the nucleus where they interact with TEAD (TEA domain family member) transcription factors to activate downstream gene expression20,21. Accumulating evidence links the activity of Yap and Taz to tumorigenesis and chemoresistance22,23,24. However, how YAP1 signalling is activated in liver CSCs remains unknown.

Here we define a highly transcribed lncRNA in liver CSCs that we call lncBRM (lncRNA for association with Brahma (BRM), gene symbol LINCR-0003), which associates with BRM and modulates the BRG1/BRM switch in the BRG1-associated factor (BAF) complex, leading to activation of YAP1 signalling and promotion of liver CSC self-renewal.

Results

LncBRM is highly expressed in HCC tumours and liver CSCs

Surface markers CD133 (ref. 25) and CD13 (ref. 6) have been widely used as liver CSC markers, respectively. We recently sorted a small subpopulation from HCC cell lines and HCC samples with these two combined makers and defined this subset of CD13+CD133+ cells as liver CSCs11,25. We performed transcriptome microarray analysis of CD13+CD133+ (liver CSCs) and CD13−CD133− (non-CSCs) cells and identified 286 differentially expressed lncRNAs in liver CSCs compared with that in non-CSCs11. We previously showed that an uncharacterized lncRNA lncTCF7 regulates the maintenance of liver CSCs through recruitment of the SWI/SNF complex to activate Wnt signalling. Among the differentially expressed lncRNAs in liver CSCs, we chose top ten highly expressed lncRNAs and silenced these lncRNAs in HCC cell lines for in vitro oncosphere formation assays. We noticed that lncBRM depletion most dramatically inhibited oncosphere formation (Fig. 1a). This result was further validated by serial sphere formation assays (Supplementary Fig. 1A,B). In addition, we deleted lncBRM in Hep3B and Huh7 cells by CRISPR/Cas9 technology and found that lncBRM knockout (KO) surely impaired serial sphere formation (Supplementary Fig. 1C,D). Notably, lncBRM knockdown did not affect the expression of its nearby genes (Supplementary Fig. 1E,F), suggesting that lncBRM exerts its function in trans.

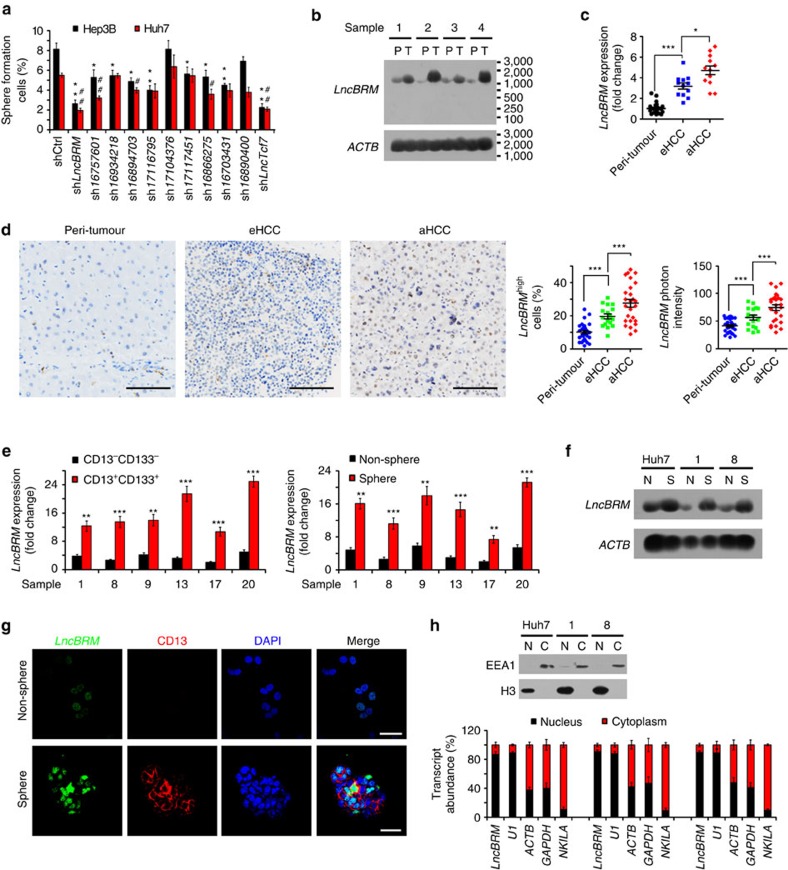

Figure 1. LncBRM is highly expressed in HCC tumours and liver CSCs.

(a) The indicated lncRNAs were silenced using pSiCoR lentivirus, followed by sphere formation assays. *, **, for Hep3B cells, Hep3B shlncBRM versus Hep3B shCtrl; #, ##, for Huh7 cells, Huh7 shlncBRM versus Huh7 shCtrl. (b) Total RNAs were extracted from peri-tumour (P) and tumour (T) tissues, followed by northern blotting. ACTB served as a loading control. (c) Primary HCC samples were prepared for examination of lncBRM expression using RT–qPCR. aHCC, advanced HCC; eHCC, early HCC. (d) LncBRM was detected by in situ hybridization. LncBRM highly expressed cells (middle panel) and lncBRM photon intensity (right panel) were calculated by Image-Pro Plus 6 and shown as scatter plot (means±s.e.m.). Scale bars, 100 μm. (e) Liver CSCs (CD13+CD133+) and non-CSCs (CD13−CD133−) were sorted from HCC samples, followed by detection of lncBRM using RT–qPCR (left panel). Oncospheres and non-spheres derived from HCC primary tumour cells were analysed similarly. Expression levels of lncBRM were normalized to that of non-tumour sample 17 as a baseline level. (f) lncBRM was examined in oncospheres and non-spheres with northern blotting. N, non-sphere; S, sphere. (g) Non-spheres and spheres were stained with lncBRM probes and CD13 antibody for confocal microscopy. Scale bars, 20 μm. (h) Nucleocytoplasmic fractionation of oncosphere cells was performed and followed by immunoblotting (upper panel) and RT–qPCR (lower panel). U1 RNA served as a nuclear location control and NKILA was used as a cytoplasmic location control. Data are shown as means±s.d. Two tailed Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments.

LncBRM located on human chromosome 5 between the ACTBL2 and PLK2 genes (Supplementary Fig. 1G). LncBRM consisted of six exons, containing 1,321 nucleotides with a modestly conserved locus according to Phylop analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1G). The full length of lncBRM was further amplified by rapid-amplification of complementary DNA ends approaches and validated by sequencing (Supplementary Fig. 1H). In addition, lncBRM had no protein-coding potential (Supplementary Fig. 1I,J). LncBRM was highly expressed in HCC primary tumour tissues through northern blotting (Fig. 1b) and it was also highly transcribed in advanced HCC samples through quantitative reverse transcriptase–PCR (RT–qPCR; Fig. 1c), further validated by in situ hybridization (Fig. 1d). These results indicate that lncBRM is highly expressed in HCC tumour tissues.

Considering high expression levels of lncBRM in liver CSCs based on transcriptome data, we next wanted to confirm lncBRM expression in liver CSCs from HCC primary samples. We observed that lncBRM was indeed highly expressed in liver CSCs derived from six HCC primary samples (Fig. 1e). Of 33 primary samples we tested, we selected out these 6 HCC samples with high expression levels of lncBRM (1, 8, 9, 13, 17 and 20; Supplementary Table 1) and used these 6 HCC samples for our following studies. We then incubated HCC primary cells and cell lines for sphere formation, followed by enrichment of oncosphere cells (Sphere) and non-sphere cells (Non-sphere) for further examination. We found that lncBRM was also highly expressed in oncosphere cells derived from HCC primary samples and cell lines (Fig. 1e,f), which was further validated by RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (RNA-FISH; Fig. 1g). In addition, lncBRM was mainly located in the nucleus (Fig. 1g). Similar observations were obtained by nucleocytoplasmic fractionation of HCC cells (Fig. 1h). Altogether, lncBRM is highly expressed in HCC tumour tissues and liver CSCs.

LncBRM is required for the self-renewal of liver CSCs

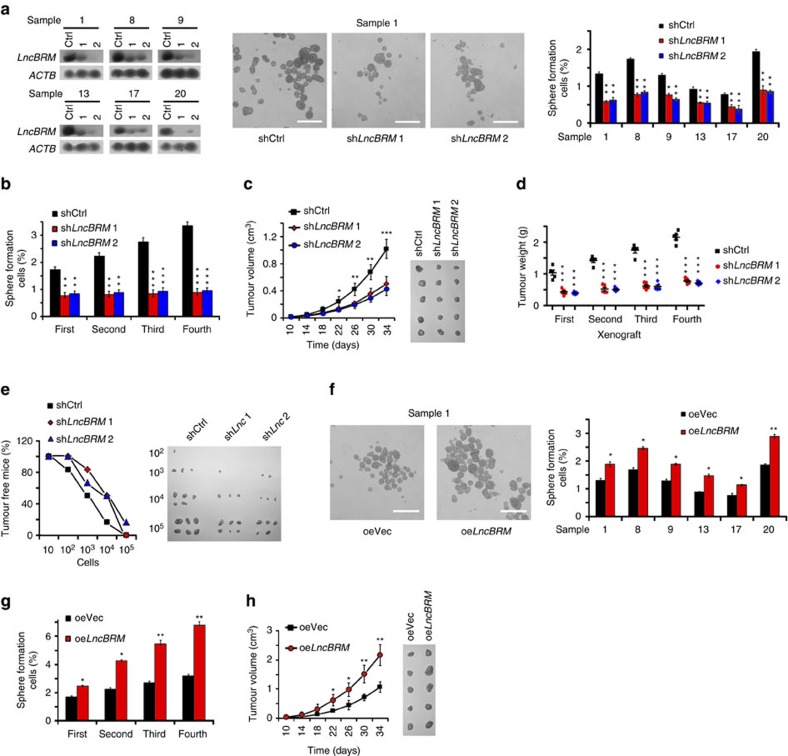

We next wanted to determine the role of lncBRM in the self-renewal maintenance of liver CSCs. We silenced lncBRM in 6 HCC primary tumour cells (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 2A), followed by sphere formation assays. For short hairpin RNA (shRNA) designs, we searched for 12 shRNA candidates against lncBRM and selected out 2 most efficient silencing shRNAs (termed shLncBRM1 and shLncBRM2) for our following studies. We noticed that lncBRM depletion markedly repressed sphere formation (Fig. 2a). Reduced self-renewal capacity was further verified in lncBRM-silenced cells through serial sphere formation assays (Fig. 2b). We established stably silenced lncBRM and scrambled RNA (shCtrl)-treated HCC primary tumour cells and injected 1 × 106 lncBRM-silenced and shCtrl cells into BALB/c nude mice, followed by measurement of tumour volumes every 4 days. LncBRM-depleted cells significantly reduced tumour propagation compared with shCtrl-treated cells (Fig. 2c), which was further validated by in vivo serial xenograft passage assays (Fig. 2d). Furthermore, lncBRM silencing displayed much weaker tumour initiation and tumorigenic cell frequency as measured by a limiting dilution xenograft analysis (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Table 2A). To validate the results by lncBRM knockdown, we also established lncBRM KO cells by using a CRISPR/Cas9 approach. LncBRM KO displayed impaired self-renewal capacities of liver CSCs (Supplementary Fig. 2B,C), which were really in agreement with those of lncBRM knockdown results. Therefore, these results indicate that lncBRM depletion abrogates the stemness of liver CSCs.

Figure 2. LncBRM is required for the self-renewal maintenance of liver CSCs.

(a) LncBRM-silenced cells from HCC samples were established and examined by northern blotting (left panel), followed by sphere formation assays. Representative sphere images were shown in the middle panel and statistic ratios were shown in the right panel. (b) Declined self-renewal capacities of lncBRM-depleted cells were detected by serial sphere formation assays. (c) LncBRM-depleted and control cells (1 × 106) were injected into BALB/c nude mice, followed by measurement of tumour volumes. n=5 for each group. (d) LncBRM-silenced primary cells were established with pSiCoR lentivirus and used for subcutaneous injection. Xenograft tumours were used for serial tumour implantation. n=5 for each group. (e) LncBrm silenced and shCtrl cells (10, 102, 103, 104 and 105) were subcutaneously injected into BALB/c nude mice for observation of tumour growth. Tumour-free mice ratios and tumour sizes are shown. (f) LncBRM-overexpressing primary cells were established and used for sphere formation assays. (g) LncBRM-overexpressing cells were examined by serial sphere formation assays. (h) LncBRM-overexpressing cells were injected into BALB/c nude mice for observation of tumour growth and measurement of tumour volume every 4 days. n=5 for each group. Scale bars, 500 μm (a,f). Data are shown as means±s.d. Two tailed Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis; *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. Data are representative of four independent experiments.

We then generated lncBRM stably overexpressed HCC primary tumour cells using lentivirus (Supplementary Fig. 2D), followed by examination of sphere formation and self-renewal capacities. We observed that lncBRM overexpression augmented in vitro oncosphere formation and self-renewal (Fig. 2f,g), as well as promoted xenograft tumour propagation and tumorigenic cell frequency (Fig. 2h, Supplementary Fig. 2E,F and Supplementary Table 2B). Collectively, lncBRM promotes the self-renewal of liver CSCs and in vivo tumour propagation.

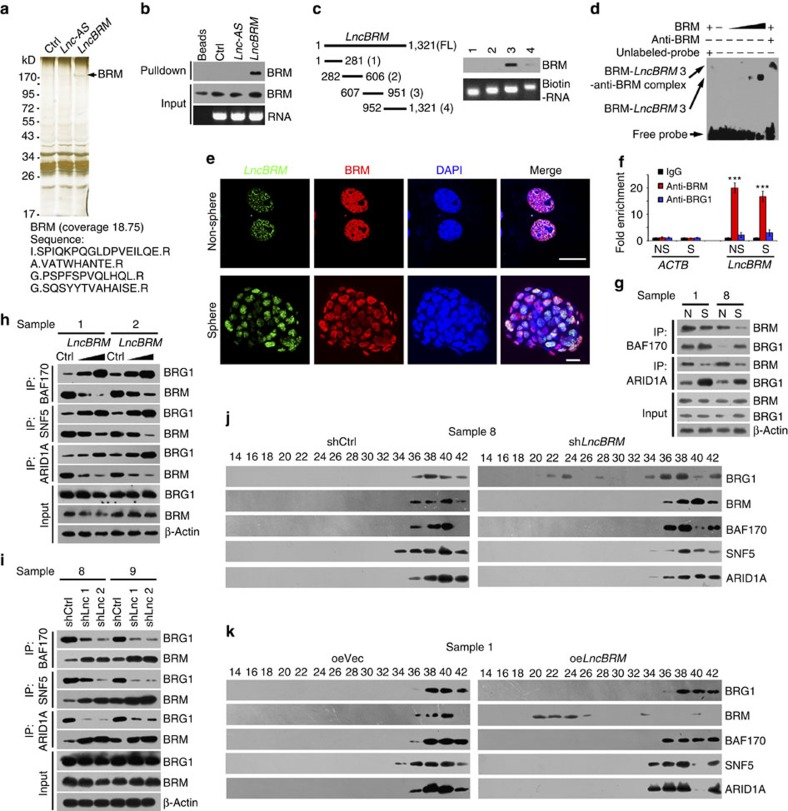

LncBRM modulates the BRG1/BRM switch

To determine associated proteins of lncBRM, we performed RNA pulldown assays in oncosphere cell lysates with biotin-labelled lncBRM. One overtly differential band around 170 kDa appeared by silver staining (Fig. 3a) and identified to be BRM by mass spectrometry (Supplementary Fig. 3A). In fact, lncBRM could precipitate BRM in liver oncosphere cell lysates by RNA immunoprecipitation, but not other BAF complex components (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 3B). Through domain mapping, we defined that 3 segment (607∼951) of lncBRM interacted with BRM (Fig. 3c). In addition, stable stem-loop structure of the binding fragment was predicted by RNA folding analysis (Supplementary Fig. 3C). The interaction of lncBRM with BRM was further validated by an RNA electrical mobility shift assay (EMSA; Fig. 3d). The co-localization of lncBRM and BRM in non-sphere and oncosphere cells was visualized by immunofluorescence staining (Fig. 3e) and mainly distributed in the nucleus. These data indicate that lncBRM associates with BRM in the nuclei of liver CSCs.

Figure 3. LncBRM associates with BRM to initiate the BRG1/BRM switch.

(a) LncBRM intron sequence (Ctrl), lncBRM antisense (Lnc-AS) and lncBRM transcripts were labelled with biotin and incubated with oncosphere lysates, followed by silver staining and mass spectrometry. Black arrow denotes BRM. (b) RNA pulldown was conducted using lncBRM transcript, followed by immunoblotting. (c) Domain mapping of lncBRM transcript. (d) LncBRM was incubated with increased doses of BRM, followed by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA). The 3 segment of lncBRM was labelled with biotin for probing. (e) Non-spheres and spheres were visualized by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). Scale bar, 10 μm. (f) Antibodies against BRM or BRG1 were used for RNA immunoprecipitation, followed by RT–qPCR. ACTB served as a negative control. (g) Spheres (S) and non-sphere cells (N) were lysed and followed by immunoprecipitation with BAF170 and ARID1A antibodies. BRG1 and BRM enrichment was analysed with western blotting. (h) Different doses of lncBRM transcripts were incubated with oncosphere lysates and followed by co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP). (i) LncBRM-depleted HCC primary spheres were lysed for co-IP as in h. (j,k) The indicated oncosphere lysates were fractionated and followed by size fractionation with glycerol gradient ultracentrifugation. Elute gradients were used for western blotting. Data are shown as means±s.d. Two tailed Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis, ***P<0.001. Data represent at least three independent experiments.

The SWI/SNF complex is an evolutionally conserved multi-subunit chromatin remodelling complex, which uses ATPase subunit BRM or BRG1 to provide ATP for remodelling nucleosomes26,27. Mammals contain two yeast BRM homologues BRM and BRG1, which are widely expressed and amino acid sequences are 75% identical. Nonetheless, these subunits are mutually exclusive, as each SWI/SNF complex possesses BRM or BRG1, forming a BRM-embedded or BRG1-embedded BAF complex. However, the physiological roles of the BRM-embedded or BRG1-embedded BAF complex have not been defined yet. We noticed that anti-BRM antibody but not anti-BRG1 antibody could precipitate lncBRM in oncosphere cell lysates (Fig. 3f), validating the interaction between BRM and lncBRM. We observed that BRM-embedded BAF complex was dramatically declined in oncosphere cells (Fig. 3g), but BRG1-embedded BAF complex predominantly existed in these cells, suggesting a BRG1/BRM switch in liver CSCs. The anti-BRM (catalogue number 11966) and anti-BRG1 (catalogue number 21634-1-AP) were specifically recognized their respective proteins.

We then incubated lncBRM transcripts with oncosphere lysates for co-immunoprecipitation assays. We observed that lncBRM increased assembled BRG1-embedded BAF complex (Fig. 3h), but not BRM-embedded complex. Moreover, lncBRM depletion impaired the BRG1-embedded BAF complex in oncosphere cells (Fig. 3i). To further verify this result, we used lncBRM-silenced sphere lysates to conduct size fractionation assays as previously described25. BRG1 and BRM constitute the BRG1- and BRM-embedded BAF complex, respectively, which can be detected by sucrose density gradient centrifugation. We noticed that lncBRM depletion indeed caused more free BRG1 in oncespheres (Fig. 3j), suggesting impaired assembly of the BRG1-biased BAF complex. In contrast, lncBRM overexpression led to more free BRM in oncespheres (Fig. 3k), suggesting impaired assembly of the BRM-biased BAF complex. Finally, we found that lncBRM depletion did not significantly impact BRM stability or ATPase activity (Supplementary Fig. 3D,E). Collectively, lncBRM associates with BRM to sequester BRM away, to initiate assembly of BRG1-biased BAF complex in liver CSCs, resulting in the BRG1/BRM switch.

BRG1 initiates activation of YAP1 signalling in liver CSCs

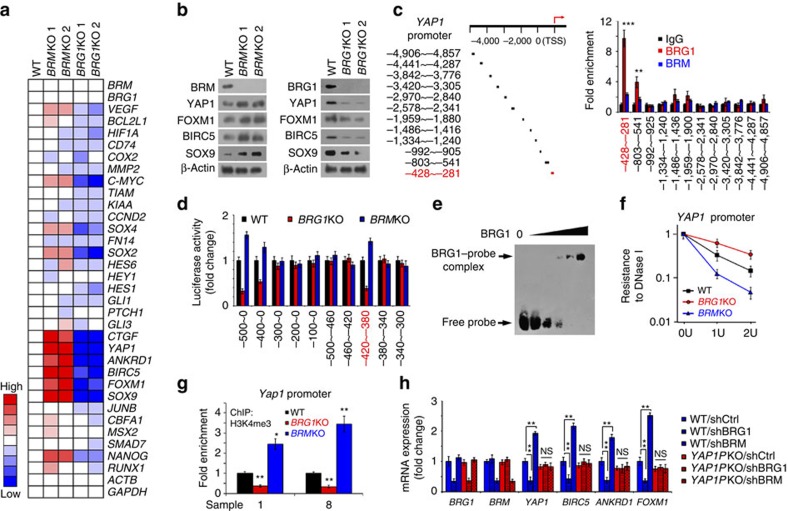

We next wanted to explore the function of BRG1-embedded BAF complex in the self-renewal maintenance of liver CSCs. We generated BRG1 and BRM KO cells using CRISPR/Cas9 approaches as previously described25. We detected expression levels of major self-renewal-related pathways in BRG1 KO and BRM KO spheres. We found that BRG1 deletion dramatically abrogated YAP1 signalling (Fig. 4a). By contrast, BRM KO remarkably activated YAP1 signalling. These results were further validated by immunoblotting (Fig. 4b), suggesting that BRG1-embedded BAF complex could be involved in the activation of YAP1 signalling.

Figure 4. BRG1-embedded BAF complex initiates YAP1 signalling in liver CSCs.

(a) BRG1 and BRM KO cells were established by CRISPR/Cas9 approaches, followed by examination of main self-renewal pathway target genes. Gene fold changes were determined by RT–qPCR. CRISPR/Cas9 caused frameshift mutations with no changes in mRNA levels. (b) YAP1 targets were tested by immunoblotting in BRM KO spheres (left panel) or BRG1 KO spheres (right panel). (c) Schematic diagram of YAP1 promoter (left panel) and domain mapping (right panel). HCC primary spheres were collected for ChIP assay with BRG1, BRM antibodies. TSS, transcription start site. (d) The binding region of YAP1 promoter to BRG1 was validated by luciferase assay. (e) Biotin-labelled YAP1 promoter region (−420∼−380 bp) was used for EMSA assay. BRG1 was immunoprecipitated from Huh7 spheres using BRG1-specific antibody. (f) Oncosphere nuclear lysates of the indicated cells were treated with DNase I, followed by real-time PCR. (g) BRG1 KO or BRM KO spheres were used for ChIP assays using H3K4me3 antibody. (h) BRG1-binding region of YAP1 promoter was deleted in HCC primary tumour cells using CRISPR/Cas9 technology, followed by depletion of BRG1 or BRM. Total RNA was extracted for PCR assay. YAP1PKO, YAP1 promoter KO. Data are shown as means±s.d. Two tailed Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis; *P<0.05 and **P<0.01; NS, not significant. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

Through domain mapping, we observed that BRG1 bound to YAP1 promoter (Fig. 4c) and validated by luciferase assays (Fig. 4d). However, BRM had no such binding activity. The interaction of BRG1 with YAP1 promoter was further verified by EMSA assays (Fig. 4e). We noticed that BRG1 deletion significantly suppressed YAP1 promoter activation by DNase I sensitivity assays (Fig. 4f). By contrast, BRM deletion enhanced YAP1 promoter activation. In parallel, H3K4me3 antibody did not enriched at YAP1 promoter regions in BRG1 KO oncospheres (Fig. 4g). By contrast, it could precipitate the YAP1 promoter regions in BRM KO cells, suggesting the activation of YAP1 promoter. We next deleted the BRG1-binding region of YAP1 promoter (YAP1PKO) using a CRISPR/Cas9 approach. In YAP1PKO cells, BRG1 depletion has no effect on activation of YAP1 signalling (Fig. 4h). However, BRG1 depletion did suppress the YAP1 signalling in wild-type cells. These data indicate that BRG1 induces the activation of YAP1 signalling via binding its promoter.

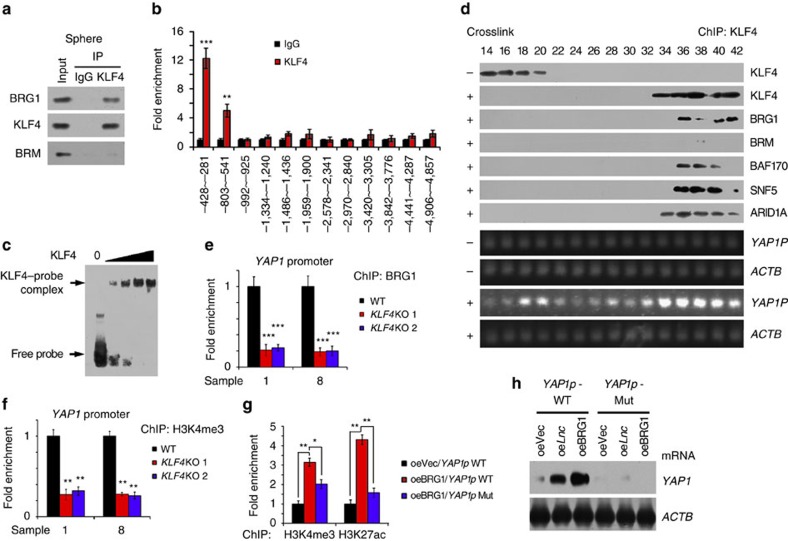

BRG1 drives YAP1 expression through a KLF4-dependent manner

To further determine how YAP1 expression was activated by BRG1-embedded BAF complex, we analysed the BRG1-binding regions of YAP1 promoter. We noticed that the BRG1-binding region of YAP1 promoter contained a specific KLF4 binding sequence. KLF4, together with other three Yamanaka pluripotency factors, is able to reprogramme adult fibroblasts into induced pluripotent cells28,29. KLF4 can inhibit somatic genes in an early phase and subsequently initiate pluripotency genes in a late phase during cellular reprogramming30,31. Of note, KLF4 interacted with BRG1 but not BRM in oncospheres (Fig. 5a). Furthermore, KLF4 bound to the same BRG1-binding region of YAP1 promoter (Fig. 5b), which was verified by EMSA assays (Fig. 5c). We next performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) with anti-KLF4 antibody through oncosphere lysates, followed by size fractionation with detection by immunoblotting. We observed that KLF4 co-eluted with BRG1-embedded BAF complex components and Yap1 promoter (Fig. 5d), suggesting KLF4 recruits the BRG1-embedded BAF complex to Yap1 promoter. In addition, KLF4 deletion abolished the binding of BRG1 with YAP1 promoter (Fig. 5e) and subsequently impaired YAP1 transcription (Fig. 5f). Importantly, KLF4 rescue in KLF4-depleted HCC cells could restore YAP1 activation (Supplementary Fig. 4A). These results indicate that KLF4 is involved in the YAP1 activation.

Figure 5. KLF4 binds YAP1 promoter and recruits the BRG1-embedded BAF complex to initiate YAP1 expression.

(a) HCC primary spheres were collected for co-IP assays with KLF4 antibody. (b) ChIP assay was performed using Klf4 antibody. (c) The interaction of KLF4 with YAP1 promoter was verified by EMSA assay. (d) HCC primary sphere cells were crosslinked with formaldehyde for ChIP assay with KLF4 antibody, followed by glycerol gradient ultracentrifugation. Elution gradients were concentrated for western blotting (upper panels) and PCR (lower panels) analyses. (e,f) KLF4 KO cells were established using CRISPR/Cas9 technology and allowed for sphere formation, followed by ChIP assay using BRG1 (e) and H3K4me3 (f) antibodies. (g) BRG1 was overexpressed in YAP1 promoter mutant (YAP1p Mut) and wild-type (WT) cells, followed by sphere formation. Oncosphere cells were used for ChIP assays with H3K4me3 and H3K27ac antibodies, followed by examination for YAP1 promoter enrichment with real-time PCR. (h) LncBRM or BRG1 was overexpressed in YAP1 promoter mutant and WT cells and collected for RNA extraction. YAP1 mRNA expression was detected with northern blotting. ACTB served as a loading control. Data are shown as means±s.d. Two-tailed Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis; *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

We next established YAP1 promoter mutant (Mut) cells by replacement of the KLF4-binding region of YAP1 promoter with a CRISPR/Cas9 approach. We observed that the YAP1 promoter mutant abrogated the interaction of KLF4 with YAP1 promoter (Supplementary Fig. 4B). H3K4me3 and H3K27Ac enrichment at gene promoters denotes the activation of genes. Consistently, the YAP1 promoter mutant reduced enrichment of BRG1 and H3K4me3 (Supplementary Fig. 4B). Moreover, overexpression of BRG1 in wild-type cells promoted YAP1 promoter activation, whereas BRG1 overexpression in YAP1 promoter mutant cells failed to initiate YAP1 promoter activation (Fig. 5g). In parallel, overexpression of lncBRM achieved similar results (Fig. 5h). We also showed that lncBRM recruited the BRG1-embedded BAF complex to YAP1 promoter (Supplementary Fig. 4C,D). These observations were further validated by luciferase assay (Supplementary Fig. 4E), ChIP assay (Supplementary Fig. 4F) and western blotting (Supplementary Fig. 4G). These data indicate that lncBRM and BRG1 induces YAP1 expression in a KLF4-dependent manner. Collectively, YAP1 promoter enriches KLF4 and KLF4 recruits the BRG1-embedded BAF complex, to initiate the activation of YAP1 transcription.

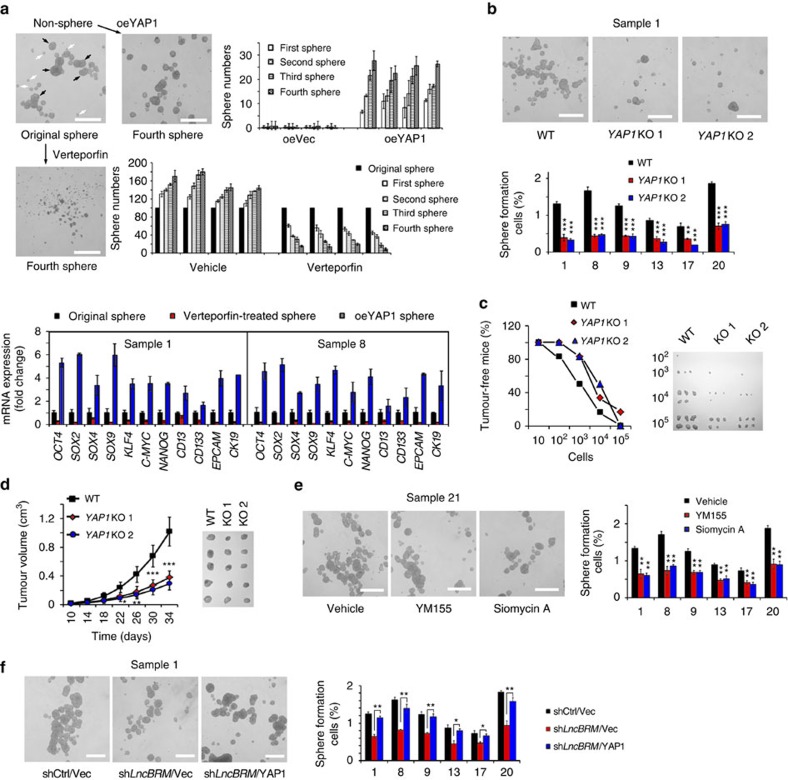

YAP1 is required for the self-renewal of liver CSCs

We further determined the physiological role of YAP1 signalling in the regulation of liver CSCs. Of note, YAP1 overexpression in non-sphere cells significantly restored sphere formation and enhanced self-renewal potential by serial passage assays (Fig. 6a). Conversely, the YAP1-specific inhibitor Verteporfin treatment in non-sphere cells abrogated sphere formation and impaired self-renewal capacity (Fig. 6a). Consequently, YAP1 overexpression in non-CSC cells augmented expression levels of stemness surface markers and pluripotency factors (Supplementary Fig. 5A). By contrast, Verteporfin treatment showed opposite results. Therefore, YAP1 signalling is required for the self-renewal maintenance of liver CSCs.

Figure 6. LncBRM-mediated YAP1 signalling is required for self-renewal of liver CSCs and tumour propagation.

(a) YAP1 was activated (overexpression) or inactivated (Verteporfin treatment) in non-sphere cells or sphere cells, followed by measurement of self-renewal by serial sphere formation assays. Fourth passage spheres and sphere numbers were shown (upper two panels). Two weeks later, original spheres, Verteportin-treated spheres and YAP1-overexpressing spheres were collected for mRNA detection (lower panels). (b) YAP1 KO cells (YAP1KO) were used for sphere formation assays. (c) Wild-type (WT) and Yap1-deficient cells (10, 102, 103, 104 and 105) were injected into BALB/c nude mice for measurement of tumour formation. Tumour-free mice and established tumours were shown. n=6 for each group. (d) 1 × 106 YAP1 KO and control cells were injected into BALB/c nude mice for tumour growth. Tumour volume was calculated every 4 days. n=5 for each group. (e) HCC primary tumour cells were treated with YM155 and Siomycin A for sphere formation assay. (f) YAP1 was rescued in lncBRM-depleted cells using pBPLV lentivirus and followed by sphere formation assay. Scale bars, 500 μm (a,b,e,f). Data are shown as means±s.d.; *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. Data are representative of four independent experiments.

We next deleted YAP1 gene in HCC primary tumour cells using CRISPR/Cas9 technology (Supplementary Fig. 5B). We found that YAP1 KO displayed impaired sphere formation (Fig. 6b) and reduced tumour-initiating capacity (Fig. 6c and Supplementary Table 2C). Consequently, YAP1-deficient cells decreased xenograft propagation (Fig. 6d). Conversely, YAP1-overexpressing cells enhanced sphere formation and xenograft propagation (Supplementary Fig. 5C and data not shown). Thus, YAP1 is essential for the self-renewal maintenance of liver CSCs and tumour initiation.

We next examined the role of YAP1 signalling target genes in liver CSCs. YM155 has been reported to be an inhibitor of BIRC5 expression32, whereas Siomycin A is a specific inhibitor against FOXM1. Of note, YM155 or Siomycin A treatment significantly suppressed oncosphere formation (Fig. 6e). Similarly, BIRC5 or FOXM1 depletion also reduced sphere formation (Supplementary Fig. 5D,E), indicating YAP1 signalling is required for promoting self-renewal of liver CSCs. Finally, Verteporfin treatment abolished enhanced sphere formation induced by lncBRM overexpression (Supplementary Fig. 5F). Consistently, YAP1 could rescue sphere formation reduced by lncBRM knockdown (Fig. 6f). Altogether, lncBRM-mediated YAP1 signalling is required for the self-renewal of liver CSCs and tumour propagation.

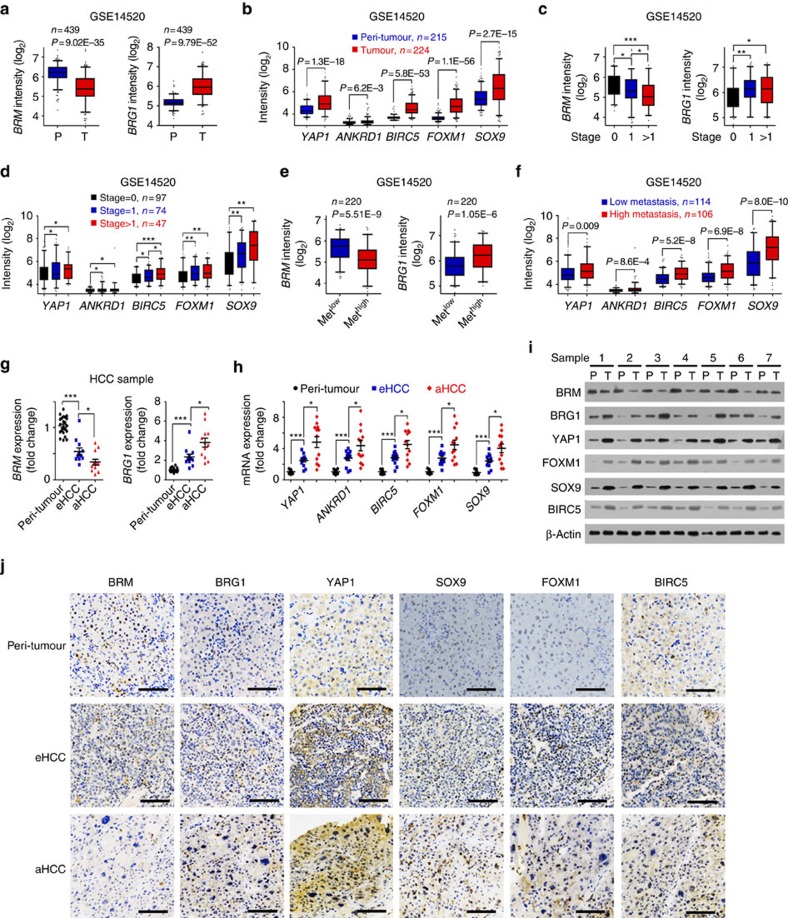

BRG1 and YAP1 targets are positively related to HCC severity

We analysed the expression levels of BRG1/BRM and Yap signalling target genes using online available data sets. We noticed that BRG1 was highly expressed in HCC tumours (Fig. 7a), whereas BRM was lowly expressed in HCC tumour tissues derived from Wang's cohort (GSE14520; ref. 33). In addition, YAP1 signalling target genes were also highly expressed in HCC tumours (Fig. 7b). Moreover, increased BRG1 levels and decreased BRM levels were positively correlated with severity of HCC patients (GSE14520; Fig. 7c). In parallel, expression levels of YAP1 signalling targets were also related to HCC severity (Fig. 7d). Of note, increased BRG1 levels and decreased BRM levels were also positively related to metastasis of HCC patients (Fig. 7e) and expression levels of YAP1 targets showed the same trend as BRG1 (Fig. 7f). We validated these observations by examination of HCC samples with RT–qPCR (Fig. 7g,h), immunoblotting (Fig. 7i) and immunohistochemical staining (Fig. 7j). Similar observations were also achieved by analysis of other two cohorts (Zhang's cohort (GSE25097) and Wang's cohort (GSE54238); Supplementary Fig. 6A–E). However, for tumour stage, metastasis and survival analyses, Wang's cohort (GSE54238) and Zhang's cohort (GSE25097) were not suitable for these analyses because of limited clinical information (GSE25097) or sample numbers (GSE54238). In addition, several Yap1 target genes we focused on (Ankrd1, Birc5 and so on) were not available in Wang's cohort (GSE54238) and Zhang's cohort (GSE25097) due to microarray platforms. More importantly, expression levels of YAP1 target genes were consistent with clinical prognosis of HCC patients (GSE14520; Supplementary Fig. 6F). Collectively, expression levels of BRG1 and YAP1 target genes are well related to cancer severity and prognosis of HCC patients.

Figure 7. Expression levels of BRG1 and YAP1 targets are positively correlated with severity and prognosis of HCC patients.

(a) Decreased BRM expression (left panels) and increased BRG1 expression (right panels) in HCC tumour tissues derived from Wang's cohort (GSE14520). R language was used for gene expression analysis. P, peri-tumour; T, tumour. (b) Expression levels of YAP1 and its target genes in peri-tumour and tumour tissues were analysed using R language and Bioconductor, and shown as box and whisker plot. (c) Increased BRG1 expression (left panel) and decreased BRM expression (right panel) in advanced HCC patients according to Wang's cohort (GSE14520). (d) High expression levels of YAP1 and its target genes in high metastasis samples derived from Wang's cohort (GSE14520). (e,f) Decreased BRM, increased BRG1 (e) and elevated YAP1 target genes (f) exhibited in high metastasis HCC patients according to Wang's cohort (GSE14520). (g) Expression levels of BRG1 and BRM were examined in HCC primary samples using RT–qPCR. aHCC, advanced HCC patients; eHCC, early HCC patients; P, peri-tumour. (h) Expression levels of YAP1 and its target genes were examined in HCC primary samples. Twenty-four peri-tumour, 12 eHCC and 12 aHCC were analysed. (i,j) HCC primary samples were lyzed for immunoblotting (i) and immunohistochemical staining (j). Scale bars, 100 μm. For a–f, data are shown as box and whisker plot. Box: interquartile range (IQR); horizontal line within box: median; whiskers: 5–95 percentile. For g,h, data are shown as means±s.d. Two tailed Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis; *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments.

Discussion

CSCs may contribute to cancer relapse and metastasis due to their invasive and drug-resistant capacities34. Recently, several surface markers have been identified to enrich liver CSCs6,8,11, whose heterogeneous markers may represent different cellular origins. However, the biology of liver CSCs remains largely unknown. We previously isolated a rare subset of CD13+CD133+ cells from most HCC cell lines and primary samples11,25, and showed that the CD13+CD133+ subpopulation harbours robust self-renewal and differentiation abilities, serving as liver CSCs. Based on our transcriptome microarray analysis of liver CSCs, we identified an uncharacterized lncRNA termed lncBRM, which maintains the stemness of liver CSCs in trans. LncBRM associates with BRM to initiate the BRG1/BRM switch and the BRG1-embedded BAF complex triggers activation of YAP1 signalling.

LncRNAs, as a new class, exhibit a wide range of expression levels and distinct cellular localizations, reflecting a large and diverse class of regulators12,35. LncRNAs can exert their functions through diverse modes, including cotranscriptional regulation, modulation of gene expression, scaffolding of nuclear or cytoplasmic complexes, as well as pairing with other RNAs36. Collectively, lncRNAs can function in cis to regulate expression of neighbouring genes or in trans to carry out many roles by various modes35. Several recent studies reported that lncRNAs are implicated in tumour initiation, invasion and metastasis16,17,19,37,38. However, the exact role of lncRNAs in liver CSCs remains largely undefined. Here we showed that lncBRM is highly expressed in HCC tumours and liver CSCs. LncBRM associates with BRM to make the BRG1/BRM switch and BRG1-embedded BAF complex initiates the activation of YAP1 signalling to sustain the self-renewal of liver CSCs. Of note, lncBRM deletion failed to impact asymmetric division ratios and differentiation tendency. Surely, lncBRM and lncTCF7 had their unique predicted tertiary structures. Of note, lncBRM KO did not affect the expression levels of lncTCF7 and its target gene TCF7 in liver CSCs (Supplementary Fig. 7A). Conversely, lncTCF7 deletion did not have an impact on the expression levels of lncBRM and YAP1 either (Supplementary Fig. 7B). These data suggest that lncBRM and lncTCF7 regulate the stemness of liver CSCs by using different pathways. In addition, we observed that depletion of both lncTCF7 and lncBRM more significantly impaired oncosphere formation than lncTCF7 or lncBRM depletion alone (Supplementary Fig. 7C), suggesting that targeting both lncTCF7 and lncBRM may be better than lncBRM or lncTCF7 alone for potential therapy of HCC patients. Liver CSCs are really heterogeneous and many different types of liver CSCs have been reported by the expression of different CSC markers such as CD90, EpCAM, CD24, CD44 and so on. We found that lncBRM was also highly expressed in CD90+, EpCAM+, CD24+ or CD44+ CSCs isolated from HCC primary samples (Supplementary Fig. 7D). In addition, lncBRM silencing in CD90+, EpCAM+, CD24+ or CD44+ CSCs indeed impaired CSC self-renewal and oncosphere formation (Supplementary Fig. 7E). These observations were consistent with those of CD13+CD133+ cells11. In our tested liver CSCs, lncBRM was highly expressed in these CSC cells and required for their self-renewal maintenance. In addition, we observed that the ratios of CD13+CD133+ populations in HCC primary samples were around 3∼12% and over 90% population percentage in HCC patients (Supplementary Fig. 7F). However, there was no significant relationship between the lncBRM expression levels and the ratios of CD13+CD133+ populations. Moreover, lncBRM deletion failed to affect asymmetric division ratios and differentiation tendency (Supplementary Fig. 7G,H), suggesting that lncBRM mainly regulates the self-renewal of liver CSCs through lncBRM-mediated YAP1 activation.

Chromatin structure is modulated by two general classes of complexes: those that covalently modify histone tails and those that remodel nucleosomes in an ATP-dependent manner27,39. SWI/SNF remodelling complexes use the energy of ATP hydrolysis to remodel nucleosomes and to regulate gene transcription. Of note, inactivating mutations of several SWI/SNF subunits have been found in various human tumours26,40,41; thus, the SWI/SNF complexes have been considered to be tumour suppressors. However, the role of SWI/SNF complexes in cancer remains controversial. In mammals, BAF-containing complexes were termed BAF complexes, which encompass one of two mutually exclusive catalytic ATPase subunits, either BRM (also known as SMARCA2) or BRG1 (also called SMARCA4). Although BRM may have some redundancy with BRG1, these two types of complexes could be largely distinct42. BRG1-deficient mice die in early embryonic development, whereas BRM-deficient mice are live and heavier than normal mice43,44. BRG1 tends to interact with Zinc finger proteins through its unique amino-terminal domain, whereas BRM associates with proteins containing two ankyrin repeats45. Herein we showed that BRG1 promotes the self-renewal of liver CSCs, but BRM exerts an opposite effect (data not shown). Mechanistically, lncBRM binds to BRM that is replaced by its homologue BRG1 to form the BRG1-biased BAF complex, which triggers the activation of YAP1 signalling. BRM binding with lncBRM may undergo conformational changes to abolish its binding capacity to the BAF complex. Another possibility is that lncBRM may bind to the domain of BRM that is critical for the assembly of BRM-biased BAF complex. In fact, increased BRG1 with decreased BRM appears in HCC tumours and this trend is related to severity of HCC patients. We show that the BRG1/BRM switch plays a critical role in the regulation of liver CSC self-renewal and HCC oncogenesis. A recent report showed that the interaction of Yki/Yap1 and Brm, the Drosophila homologue of mammalian BRG1, promotes Yki-dependent transcription and tissue growth in Drosophila46. Here we demonstrate the specific interaction of KLF4 and BRG1 (but not BRM) in liver CSCs to initiate YAP1 signalling activation.

Physical properties of the extracellular matrix (ECM) and mechanical forces are integral to defining tissue architecture and driving specific cell differentiation programmes in embryonic development47. In adulthood, tissue homeostasis remains dependent on physical cues, such that perturbations of ECM stiffness are causal to pathological conditions of multiple organs, contributing to ageing and malignant transformation48. Mechanotransduction enables cells to perceive and adapt to external forces and physical constraints. YAP1 and Taz can perceive mechanical signals exerted by ECM rigidity and cell shape as mechanotransducers49, which requires Rho GTPase activity and reorganization of cytoskeleton, but is independent of the Hippo/Lats cascade. We found that Lats1 is undetectable and in liver CSCs following mechanical train (data not shown). Moreover, we noticed that BRG1 KO or BRM KO did not have an impact on phosphorylation signals of MST1/2 and LATS1 in liver CSCs. Therefore, lncBRM-mediated YAP1 signalling is independent of the Hippo/Lats cascade in the progression of HCC. As for tumorigenesis, inflammation, changes of microenvironments and stiffness of ECM confine the cell's adhesive area and result in mechanical strain21. We added Matrigel, collagen I or methyl-cellulose in sphere formation media followed by oncosphere formation assays. Addition of these three reagents dramatically promoted HCC primary oncosphere formation and augmented expression of pluripotency factors (data not shown), suggesting mechanical strain enhances the initiation of liver CSC self-renewal. However, how mechanical strain modulates the activation of lncBRM-mediated YAP1 signalling in liver CSCs needs to be further investigated.

In summary, lncBRM is highly expressed in HCC tumours and liver CSCs, which triggers YAP1 signalling to promote self-renewal of liver CSCs and initiate tumour propagation (Supplementary Fig. 7I). Therefore, lncBRM, along with YAP1 signalling targets might be used in diagnosis and prognosis, as well as in the development of novel therapeutic drugs against HCC.

Methods

Cells lines

HCC cell lines Huh7, Hep3B and PLC were obtained from Dr Zeguang Han (Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China). HCC cell lines were maintained in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 μg ml−1 penicillin and 100 U ml−1 streptomycin. All cell lines were verified by PCR (SV40gp6 for 293 T cells; HBVgp2 for PLC cells; AFP, ALB, HBVgp2 and A2M for Hep3B; and AFP for Huh7 cells). These cell lines were not contaminated by mycoplasma.

For preparation of HCC primary cells, HCC samples were immediately obtained after resection. Tumour bulk was cut into 1 mm3 with scissors, followed by 40 min digestion at 37 °C with collagenase IV (0.05% collagenase IV, 0.05% proteinase, 0.01% DNase and 5 mM CaCl2 in HBS), with shaking every 10 min. Next, the medium were passed through a 70 μm cell strainer and centrifuged at 50 g for 1 min. Supernatant fractions were collected and further centrifuged at 150 g for 8 min and HCC cells were enriched in pellets. After treatment with Red Blood Cell Lysis Buffer for red cell elimination, the HCC primary cells were obtained, followed by FACS, sphere formation and other experiments.

Antibodies and regents

Anti-β-actin (catalogue number A1978, 1:5,000), anti-Flag (catalogue number F1804, 1:5,000) and anti-YAP1 (catalogue number Y4770, 1:500) antibodies were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Anti-BRG1 (catalogue number 21634-1-AP, 1:500), anti-FOXM1 (catalogue number 13147-1-AP, 1:1,000) and anti-KLF4 (catalogue number 11880-1-AP, 1:500) antibodies were obtained from Proteintech Group. Anti-BRM (catalogue number 11966, 1:1,000), anti-BAF170 (catalogue number 12760, 1:1,000), anti-SNF5 (catalogue number 8745, 1:1,000), anti-ARID1A (catalogue number 12354, 1:1,000), anti-Baf155 (catalogue number 11956, 1:1,000), anti-Histone H3 (catalog 4499, 1:2,000) and anti-Oct4 (catalogue number 2750, 1:5,000) antibodies were from Cell signalling technology. Anti-SOX9 antibody (catalogue number AB5535, 1:500) was obtained from Millipore. Anti-BIRC5 antibody (catalogue number sc-8807, 1:1,000) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (catalogue number sc-2004, sc-2005, 1:500) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Phycoerythrin-conjugated CD133 antibody (catalogue number 130-098-826, 1:200) was from Miltenyi Biotec. Fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated CD13 antibody (catalogue number 11-0138, 1:500) was from eBioscience. Alexa488-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG (catalogue number R37114, 1:500), Alexa594-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (catalogue number R37119, 1:500) and Alexa594-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG (catalogue number R37115, 1:500) antibodies were from Molecular Probes Life Technologies. Epidermal growth factor (catalogue number E5036-200UG), PEG5000 (catalogue number 175233-46-2) and 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (catalogue number 28718-90-3) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich; N2 supplement (catalogue number 17502-048) and B27 (catalogue number 17504-044) were from Life Technologies; basic fibroblast growth factor (catalogue number GF446-50UG) was from Millpore. LightShift Chemiluminescent RNA EMSA Kit (catalogue number 20158) and Chemiluminescent Nucleic Acid Detection Module (catalogue number 89880) were from Thermo Scientific. T7 RNA polymerase (catalogue number 10881767001) and Biotin RNA Labeling Mix (catalogue number 11685597910) were from Roche.

EMSA and RNA EMSA assays

BRG1 and KLF4 EMSA assays were performed using standardized EMSA procedure, and KLF4 and BRG1 were obtained using immunoprecipitation from oncospheres50. Biotin-labelled YAP1 promoter (−420∼−380) was purchased from Sangon Company (Shanghai, China) and labelled with [r-32P] dATP according to standard protocol. Probes and precipitated proteins were incubated in EMSA binding buffer and mobility shift assay was performed using gel electrophoresis.

For RNA EMSA, human BRM plasmid was transfected into Huh7 cells, then cell nuclear extracts were isolated from BRM-overexpressed oncospheres. LncBRM-specific probes were labelled with Biotin using Biotin RNA Labeling Mix (Roche). BRM nuclear extracts and biotin-labelled probe were incubated in 1 × REMSA binding buffer supplementing with Glycerol, transfer RNA and dithiothreitol for 30 min according to LightShift Chemiluminescent RNA EMSA Kit (Thermo Scientific). Native PAGE was performed for separating components followed by transferring onto positively charged NC film (Beyotime Biotechnology). After ultraviolet cross-linking, HRP-conjugated streptavidin was added to detect the biotin signalling according to Chemiluminescent Nucleic Acid Detection Module (Thermo Scientific).

RNA pulldown assay

For RNA pulldown assays, biotin-labelled lncBRM transcripts, lncBRM intron sequence and its antisense were obtained using in vitro transcription with T7 RNA polymerase and Biotin RNA Labeling Mix (Roche), followed by 4 h incubation at 37 °C with oncosphere cell lysates. Then streptavidin-conjugated agarose beads were used for centrifugal enrichment. Precipitated components were separated using SDS–PAGE, followed by silver staining51. Differential bands were cut for mass spectrometry (LTQ Orbitrap XL).

RNA immunoprecipitation

Primary spheres were treated with 1% formaldehyde for 15 min, then dissolved with modified RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.2% SDS, 1% NP40, 1%Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA and 50 mM Tris pH 8.0), supplementing with Protector RNase inhibitor and protease inhibitors (Roche). Samples were sonicated three times on ice, followed by 13,800 g centrifugation for 10 min. Supernatants were incubated with protein A/G beads for 1 h, followed by 4 h incubation with indicted antibodies and subsequent 2 h incubation with protein A/G beads. LncBRM enrichment was examined using RT–qPCR, IgG enrichment served as controls52. Primer sequences are shown in the Supplementary Table 3.

Northern blotting

Total RNA was extracted from HCC samples or oncospheres using standard TRIZOL methods, followed by electrophoresis with formaldehyde denaturing agarose gel. Samples were transferred to positively charged NC film (Beyotime Biotechnology) using 20 × SSC buffer (3.0 M NaCl, 0.3 M sodium citrate, pH 7.0). After ultraviolet cross-linking, membrane was incubated with hybrid buffer for 2 h prehybridization, followed by incubation with Biotin-labelled RNA probes generated by in vitro transcription at 65 °C for 20 h. Biotin signals were detected with HRP-conjugated streptavidin according to the introduction of Chemiluminescent Nucleic Acid Detection Module (Thermo Scientific).

RNA–FISH assay

Fluorescence-conjugated lncBRM probes for RNA–FISH were generated according to protocols of Biosearch Technologies. HCC samples or spheres were treated in a non-denaturing condition, followed by hybridization with DNA probe sets. Then primary antibodies were added after RNA hybridization for co-localization of RNA and indicated proteins. All experiments were performed as described in manuals of Biosearch Technologies11. Treated samples were visualized by confocal microscopy (FV1000, Olympus).

Lentivirus generation and infection

For lncBRM and other lncRNA knockdown, we constructed pSiCoR shRNA system. Sequences of shRNAs were designed according to online tools of Clontech Company and cloned into pSiCoR vector. For virus generation, we transfected 293T cells with pSiCoR along with package plasmids (4 mg pSiCoR vector, 1 mg VSVG, 1 mg pMDL g/p RRE and 2 mg RSV-REV were used for 10 cm dish). Hep3B, Huh7 and HCC primary cells were infected by virus supernatants or PEG5000 (Sigma)-enriched precipitates. After purified with puro or green fluorescent protein (GFP), stable cell lines were established. For overexpression, similar strategy was used. shRNA sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 4.

Western blotting

Primary cells and spheres were crushed with RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1% NP40, 1 mM EDTA and 50 mM Tris pH 8.0), followed by separation with SDS–PAGE. Then samples were transferred to NC membrane and incubated with primary antibody in 5% milk. After washing with TBST three times, membranes were blotted with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies for visualization53. The uncropped blots were shown in Supplementary Fig. 8.

Sphere formation assay

One thousand PLC or Hep3B cells were grown in sphere formation medium (DMEM supplemented with 20 ng ml−1 basic fibroblast growth factor, 20 ng ml−1 epidermal growth factor, N2 and B27). Two weeks later, spheres larger than 100 μm were counted and photographs were taken. For HCC samples, 5,000 primary cells were used for sphere formation.

Diluted xenograft tumour formation

For tumour propagation analysis, lncBRM or YAP1 silenced tumour cells (1 × 106) were subcutaneously injected into BALB/c mice. Tumour volumes were measured every 4 days. For tumour-initiating capacity assay, 10, 102, 103, 104 and 105 cells were injected into BALB/c nude mice, respectively. Three months later, tumour formation was counted, followed by calculation of ratios of tumour-free mice and tumour-initiating cells9.

ChIP immunobloting assay

ChIP immunobloting assay and size fractionation were performed using oncospheres25. For ChIP assays, oncospheres were treated with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min for crosslinking (+crosslink), crashed with SDS lysis buffer and followed by ultrasonication. Standard ChIP assay was performed using KLF4 antibody. The eluate (500 μl) was layered onto 35 ml 5–30% (V/V) glycerol gradients followed by ultracentrifugation. S Beckman SW28 rotor was used for ultracentrifugation at 55,200 g for 30 h. Then, fractions were carefully collected and the elution gradients were concentrated to 50 μl using centrifugal concentration tubes. Finally, the samples were analysed using western blotting and PCR assays. For BRG1/BRM switch, spheres were crushed with RIPA buffer, followed by glycerol gradient ultracentrifugation.

CRISPR/Cas9 KO system

BRG1, BRM, KLF4, YAP1 and YAP1 promoter-deficient and YAP1 promoter mutant HCC primary cells were established using a CRISPR/Cas9 system8,25. Briefly, single guide RNA (sgRNA) was designed by online CRISPR Design Tool (http://tools.genome-engineering.org) and cloned into lenti Cas9-EGFPvector (Addgene catalogue number 63592). After confirming the cutting efficiency of sgRNA, lenti Cas9 was transfected into 293T cells with pVSVg (Addgene catalogue number 8454) and psPAX2 (Addgene catalogue number 12260) for 48 h. Supernatants were collected and concentrated with PEG5000 (Sigma Aldrich), then infected primary cells for 5 days. GFP-positive cells (usually >80%) were enriched, followed by KO efficiency examination using western blotting. For YAP1 promoter KO, a pair of sgRNAs that were derived from the left locus and the right locus of BRG1/KLF4-binding region on YAP1 promoter were cloned into puro lentiCRISPRv2 and GFP lentiCRISPRv2. Two a lentivirus were co-transfected and the KO efficiency was confirmed by DNA sequencing. For YAP1 promoter mutation, sgRNA and template DNA were transfected into Huh7 cells, followed by selection and monoclonalization. Genome DNA was extracted and YAP1 promoter established clones were examined by T7 endonuclease I cleavage, and confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Statistical methods

R language and Bioconductor were used to analyse online available data sets and results were shown as box and whisker plot54. For CSC ratio analysis, extreme limiting dilution analysis was performed using tumour-free mouse numbers of 10, 102, 103, 104 and 105 cells55. For most trials, two tailed Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis. P<0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Study approval

Human HCC samples were obtained from the Department of Hepatobiliary Surgery, PLA General Hospital (Beijing, China) with informed consents from all human participants, according to the Institutional Review Board approval. We numbered HCC primary samples according to receiving date and used the samples without artificial bias. Six-week-old female BALB/c nude mice were purchased from the Animal Center of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (Beijing, China). All experiments involving mice were approved by the institutional committee of Institute of Biophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Studies were conducted in a blinded manner. Animals were randomly assigned to groups. No sample-size estimates were used and no animals or samples were excluded from analyses.

Data availability

The microarray data used in the study (GSE66529, GSE14520, GSE25097 and GSE54238) are available in a public repository from EBI (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/) or NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds/?term). All relevant data are available from the authors.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Zhu, P. et al. LncBRM initiates YAP1 signalling activation to drive self-renewal of liver cancer stem cells. Nat. Commun. 7, 13608 doi: 10.1038/ncomms13608 (2016).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures 1-8 and Supplementary Tables 1-4.

Acknowledgments

We thank Junying Jia for technical support. We thank Jing Li (Cnkingbio Company Ltd, Beijing, China) for technical support. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (91419308, 91640203, 81330047, 31530093, 81272270, 81402459 and 81101531); 973 Program of the MOST of China (2015CB553705); the State Projects of Essential Drug Research and development (2012ZX09103301-041); the Strategic Priority Research Programs of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA01010407 and XDA01020203); Postdoctoral innovation programme of China Postdoctoral Science Foundation.

Footnotes

Author contributions P.Z. designed and performed experiments, analysed the data and wrote the paper. Y.W. performed experiments and analysed data. J.W., G.H., B.L., B.Y., Y.D., S.W., G.G. and Y.T. analysed the data. L.H. provided HCC samples and analysed the data. Z.F. initiated the study, organized, designed and wrote the paper.

References

- Bruix J., Gores G. J. & Mazzaferro V. Hepatocellular carcinoma: clinical frontiers and perspectives. Gut. 63, 844–855 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visvader J. E. Cells of origin in cancer. Nature 469, 314–322 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visvader J. E. & Lindeman G. J. Cancer stem cells: current status and evolving complexities. Cell Stem Cell 10, 717–728 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreso A. & Dick J. E. Evolution of the cancer stem cell model. Cell Stem Cell 14, 275–291 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z. et al. Enhanced sensitivity of cancer stem cells to chemotherapy using functionalized mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Mol. Pharm. 13, 2749–2759 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haraguchi N. et al. CD13 is a therapeutic target in human liver cancer stem cells. J. Clin. Invest. 120, 3326–3339 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita T. & Wang X. W. Cancer stem cells in the development of liver cancer. J. Clin. Invest. 123, 1911–1918 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W. et al. 1B50-1, a mAb raised against recurrent tumor cells, targets liver tumor-initiating cells by binding to the calcium channel alpha 2 delta 1 subunit. Cancer Cell 23, 541–556 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu P. P. et al. C8orf4 negatively regulates self-renewal of liver cancer stem cells via suppression of NOTCH2 signalling. Nat. Commun. 6, 7122 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takebe N. et al. Targeting Notch, Hedgehog, and Wnt pathways in cancer stem cells: clinical update. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 12, 445–464 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. Y. et al. The long noncoding RNA IncTCF7 promotes self-renewal of human liver cancer stem cells through activation of Wnt signalling. Cell Stem Cell 16, 413–425 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batista P. J. & Chang H. Y. Long noncoding RNAs: cellular address codes in development and disease. Cell 152, 1298–1307 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh C. A. et al. The Xist lncRNA interacts directly with SHARP to silence transcription through HDAC3. Nature 521, 232–236 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T. et al. Role of MYC-regulated long noncoding RNAs in cell cycle regulation and tumorigenesis. J. Natl Cancer I 107, dju505 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatica A. & Bozzoni I. Long non-coding RNAs: new players in cell differentiation and development. Nat. Rev. Genet. 15, 7–21 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng Y. Y. et al. PVT1 dependence in cancer with MYC copy-number increase. Nature 512, 82–86 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B. et al. A cytoplasmic NF-kappaB interacting long noncoding RNA blocks IkappaB phosphorylation and suppresses breast cancer metastasis. Cancer Cell 27, 370–381 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P. et al. The STAT3-binding long noncoding RNA lnc-DC controls human dendritic cell differentiation. Science 344, 310–313 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan J. H. et al. A long noncoding RNA activated by TGF-beta promotes the invasion-metastasis cascade in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell 25, 666–681 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan D. J. The Hippo signalling pathway in development and cancer. Dev. Cell 19, 491–505 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benham-Pyle B. W., Pruitt B. L. & Nelson W. J. Cell adhesion. Mechanical strain induces E-cadherin-dependent Yap1 and beta-catenin activation to drive cell cycle entry. Science 348, 1024–1027 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori M. et al. Hippo signalling regulates microprocessor and links cell-density-dependent miRNA biogenesis to cancer. Cell 156, 893–906 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moroishi T., Hansen C. G. & Guan K. L. The emerging roles of YAP and TAZ in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 15, 73–79 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao D. D. et al. KRAS and YAP1 converge to regulate EMT and tumor survival. Cell 158, 171–184 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu P. et al. ZIC2-dependent OCT4 activation drives self-renewal of human liver cancer stem cells. J. Clin. Invest. 125, 3795–3808 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts C. W. & Orkin S. H. The SWI/SNF complex--chromatin and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 4, 133–142 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson B. G. & Roberts C. W. SWI/SNF nucleosome remodellers and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 11, 481–492 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K. & Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell 126, 663–676 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J. Y. et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science 318, 1917–1920 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polo J. M. et al. A molecular roadmap of reprogramming somatic cells into iPS cells. Cell 151, 1617–1632 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L. Q. et al. Transcriptional pause release is a rate-limiting step for somatic cell reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell 15, 574–588 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch A. et al. Survivin and YM155: how faithful is the liaison? Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1845, 202–220 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roessler S. et al. Integrative genomic identification of genes on 8p associated with hepatocellular carcinoma progression and patient survival. Gastroenterology 142, 957–966 e912 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta P. B., Chaffer C. L. & Weinberg R. A. Cancer stem cells: mirage or reality? Nat. Med. 15, 1010–1012 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinn J. L. & Chang H. Y. Genome regulation by long noncoding RNAs. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 81, 145–166 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulitsky I. & Bartel D. P. lincRNAs: genomics, evolution, and mechanisms. Cell 154, 26–46 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R. A. et al. Long non-coding RNA HOTAIR reprograms chromatin state to promote cancer metastasis. Nature 464, 1071–1076 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F., Zhang H., Mei Y. & Wu M. Reciprocal regulation of HIF-1alpha and lincRNA-p21 modulates the Warburg effect. Mol. Cell 53, 88–100 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helming K. C. & Wang X. F. Roberts CWM. Vulnerabilities of Mutant SWI/SNF Complexes in Cancer. Cancer Cell 26, 309–317 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atala A. Exome sequencing identifies frequent mutation of the SWI/SNF complex gene pbrm1 in renal carcinoma editorial comment. J. Urol. 186, 1150–1150 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S. et al. Frequent mutations of chromatin remodeling gene ARID1A in ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Science 330, 228–231 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan M. L., Sif S., Narlikar G. J. & Kingston R. E. Reconstitution of a core chromatin remodeling complex from SWI/SNF subunits. Mol. Cell 3, 247–253 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bultman S. et al. A Brg1 null mutation in the mouse reveals functional differences among mammalian SWI/SNF complexes. Mol. Cell 6, 1287–1295 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes J. C. et al. Altered control of cellular proliferation in the absence of mammalian brahma (SNF2alpha). EMBO J. 17, 6979–6991 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadam S. & Emerson B. M. Transcriptional specificity of human SWI/SNF BRG1 and BRM chromatin remodeling complexes. Mol. Cell 11, 377–389 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y. et al. Brahma regulates the Hippo pathway activity through forming complex with Yki-Sd and regulating the transcription of Crumbs. Cell Signal. 27, 606–613 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mammoto T. & Ingber D. E. Mechanical control of tissue and organ development. Development 137, 1407–1420 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaalouk D. E. & Lammerding J. Mechanotransduction gone awry. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 63–73 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont S. et al. Role of YAP/TAZ in mechanotransduction. Nature 474, 179–U212 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L., Zhu P., Xia P. & Fan Z. WASH has a critical role in NK cell cytotoxicity through Lck-mediated phosphorylation. Cell Death Dis. 7, e2301 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu P. et al. lnc-beta-Catm elicits EZH2-dependent beta-catenin stabilization and sustains liver CSC self-renewal. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 23, 631–639 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S. et al. Transient Activation of Autophagy via Sox2-Mediated Suppression of mTOR Is an Important Early Step in Reprogramming to Pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell 13, 617–625 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia P. et al. WASH is required for the differentiation commitment of hematopoietic stem cells in a c-Myc-dependent manner. J. Exp. Med. 211, 2119–2134 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Team RC. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (2014).

- Hu Y. & Smyth G. K. ELDA: extreme limiting dilution analysis for comparing depleted and enriched populations in stem cell and other assays. J. Immunol. Methods 347, 70–78 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures 1-8 and Supplementary Tables 1-4.

Data Availability Statement

The microarray data used in the study (GSE66529, GSE14520, GSE25097 and GSE54238) are available in a public repository from EBI (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/) or NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds/?term). All relevant data are available from the authors.