THE CASE: In late March 2002 a private vehicle with 3 passengers was involved in a rollover accident on a highway in a small northern BC town. The vehicle occupants were transported to the nearest medical facility by the provincial ambulance service. The only passenger with significant injuries was a 10-year-old girl. She had an unclear history of loss of consciousness, was found to be “stable” overall, but had a significant scalp laceration and was “restless.” Despite a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 15, a head CT scan was considered necessary, and arrangements were made to transfer the child to a facility with CT capability, which was about 1 hour away by road. En route, the patient experienced a profound decrease in consciousness, and she arrived in the emergency department with a GCS score of 3. Her blood pressure was 60/28 mm Hg, her pulse was 123 beats/min, and her pupils were fixed and dilated. Mechanical ventilation was started immediately, and the patient was given vigorous fluid resuscitation intravenously and sent for a head CT scan. An abdominal CT was not performed. The general surgeon on call, the only surgeon in this community, was immediately involved in her care. Upon viewing the CT, he activated the telemedicine pager, reached one of the emergency physicians on call at the Vancouver General Hospital and described the case. The consulting telemedicine emergency physician then contacted the neurosurgeon on call. Fortunately, the on-call neurosurgeon was in the Vancouver General Hospital's emergency department seeing a patient. He came immediately to the telemedicine communication room, and real-time video contact was established with the general surgeon in the rural community. The CT scan was reviewed, and the neurosurgeon confirmed the diagnosis of an epidural hematoma. It was determined that the patient required an emergency craniotomy. The air travel time from the rural location to Vancouver — about 2 hours — made transport to the centre unfeasible. There is at least 1 centre with neurosurgery capabilities less than 1 hour away from the rural location, but a snowstorm had moved into the area and made any air travel and most road travel impossible.

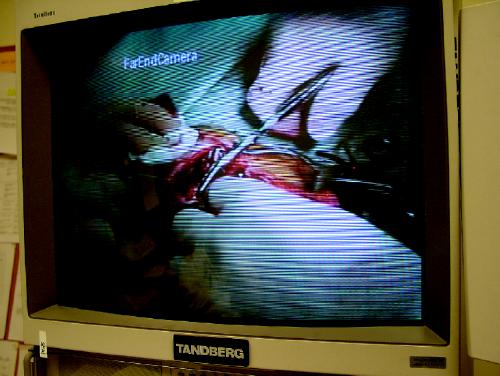

It was decided that an emergency craniotomy would be performed in the rural emergency department. The 2 cameras at the rural site were optimally positioned, and lighting was arranged while the patient was prepped and draped, all of which took less than 5 minutes. Under guidance from the consulting neurosurgeon, a frontotemporal craniectomy was performed, and the hematoma was identified and drained. Small vessels were tied off prophylactically, and no major bleeders were found. The surgeon at the rural site and the neurosurgeon in Vancouver were satisfied with the operation, and the wound was closed and dressed. There was no change in the status of the patient immediately after the procedure, with her pupils staying fixed and dilated and her systolic blood pressure now hovering in the 90–100 mm Hg range. The 3 physicians agreed that a conference including the patient's family, the surgeon and the neurosurgeon would be useful. The family was brought into the emergency area at the rural site and were able to talk “directly” to the Vancouver neurosurgeon about the operation. The videoconferencing technology allowed visual and voice communication for all parties involved in the discussion.

The patient remained in the local intensive care unit for the next several hours. No seizure activity occurred, and no anticonvulsants were used. Unfortunately, she had no recovery of central nervous system function overnight, with her pupils remaining fixed and dilated and a GCS score of 3. Arrangements were made for air transfer by fixed-wing aircraft to Vancouver as soon as the weather cleared. She arrived the next day, was pronounced brain dead by the critical care physician in conjunction with a neurologist and became a multiple organ donor.

COMMENTS FROM THE PARTICIPANTS:

The telemedicine emergency physician: The role of the consulting telemedicine physician in a case like this is, from a medical viewpoint, peripheral at best. The main role here was two-fold: first, as a facilitator in getting the surgeon at the rural site in contact with the Vancouver neurosurgeon; and second, as a technical resource person with regard to the telemedicine equipment.

In almost all cases in the BC Telehealth Program, all consultations were handled by the consulting emergency physician on call. Rarely was any additional expertise required. In this case, after confirming that the initial general trauma workup and stabilization had been completed, the required intervention clearly exceeded the skills of an emergency physician, and fortunately the necessary expertise was immediately available. This case demonstrated the need for the consultant site to have access to the wealth of resources available at most tertiary and quaternary care facilities to assist emergency physicians when specialized consultations and procedures are required.

The rural surgeon: The most striking, comforting and exhilarating aspect was the fact that the neurosurgeon was able to make eye contact with the little girl's family and the fact that they could see that he could see the patient and was therefore in a position that he could provide us with his expert opinion. I would believe that the encounter between the patient's family and the neurosurgeon (i.e., face to face) and the sincerity and warmth and empathy conveyed was the single unsurpassable aspect or moment. The family had an extremely difficult decision to make — the interview certainly helped to facilitate that decision.

The Vancouver neurosurgeon: The telemedicine link with the [remote] hospital allowed me to see the patient, the CT scan and the patient's parents. Both the audio and visual components were excellent, including allowing me to see the details of the procedure performed. Although the patient's brain injury was too severe to allow the emergency procedure to prevent her death, this technology has great promise and should be expanded in the province.

The patient's mother: Was it helpful to you to know that the neurosurgeon was actually able to see and help with your daughter's care? I can't tell you how glad I was to know that there was someone who could help out our doctors here who are not trained in that field. It was nice knowing that you could see exactly what the doctors here had done and were about to do, so that when (had things worked out for my daughter) she arrived in Vancouver your team would have been able to finish off whatever needed to be done.

Was it helpful to you to be able to see and talk with the neurosurgeon in Vancouver? Yes, it was so nice to be able to see and talk to him. To me I felt more relaxed talking to someone I could see. It was more like the doctors were in the same room as me, not trying to explain things to me over the phone. I felt like I could understand what they were saying to me when I could see them. I am so glad there is new technology out there now to help out in small remote communities. Knowing that there is hope to save someone else's life with videoconferencing, I would recommend that every hospital get this system in as soon as they can, starting with the remote communities. I would like to say thank you again for all your help.

Telemedicine is evolving in Canada, and over the last 10 years, information and communication technologies have been developed to a level sufficient to allow high-speed transmission of information and images to remote areas.1

Other countries have reported positive telemedicine experiences. In the United States, a telemedicine pilot project for trauma showed that “more than 80% of referring providers thought the telemedicine consults improved patient care.”2 Australia and South Africa are both large countries with many remote outposts that have little or no specialist support because most skilled specialists are concentrated in the urban centres. Telemedicine in countries like these extends sophisticated care to relatively unserviced areas.1

Canada, by nature of its vast area and often challenging topography, is an ideal environment for telemedicine.3 With most specialists available only in urban centres, travel and access to more specialized care is limited by time, finances and weather. For personnel and economic reasons, it is difficult to justify taking an urban specialist out of service for a day or more to see 1 patient in a remote area, let alone having that specialist be available on demand should an emergency arise. Conversely, moving a patient, and often his or her family or other caregivers, from a remote area to an urban centre is costly to the patient and the health care system. The concept of telemedicine, bringing in a “virtual” specialist, has protean implications for the practice of medicine in Canada.

There are obstacles to be overcome, as with any new program. These include, but are not limited to, finding qualified physicians willing to be on call; funding for the program; physical space for the program's administration; willingness on the part of the referring physicians to participate in the program; avoiding interference with existing referral patterns; and dealing with the inevitable problems that occur when patients are transferred between different health authorities.

In the case we have described, although the patient ultimately did not survive, the telemedicine system provided some unexpected benefits. Above and beyond the transfer of knowledge and expertise was the reassurance to the family that a higher level of care was given to the patient. Even more important was the fact that family members were able to talk “face to face” with the neurosurgeon who was involved with the care of the patient. Ironically, the use of technology may enable a more human and personal aspect to remote patient care, and that interpersonal element may play more of a role in the future of telemedicine than has been anticipated.

It is important that health care professionals, administrators and policy-makers create a system in which on-demand telemedicine services can optimally serve patients living in rural and remote areas with reasonable cost-effectiveness. If such a system can be constructed, access to care and improved coverage of emergencies anywhere, anytime will become a practical reality.

Bruce A. Campana Sandra Jarvis-Selinger Kendall Ho Warwick L. Evans Thomas J. Zwimpfer Department of Emergency Medicine Vancouver General Hospital Vancouver, BC

Figure. View of the patient's head with scalp defect.

Figure. View of the procedure.

Figure. Neurosurgeon Tom Zwimpfer discusses the case with the rural general surgeon. The central main screen shows the image seen in Vancouver. The smaller screen to the right shows the image seen at the remote site.

References

- 1.Watanabe M, Jennett P, Watson M. The effect of information technology on the physician workforce and health care in isolated communities: the Canadian picture, J Telemed Telcare 1999; 5 (Suppl 2):S2:11-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Rogers FB, Ricci M, Caputo M, Shackford S, Sartorelli K, Callas P, et al. The use of telemedicine for real-time video consultation between trauma center and community hospital in a rural setting improves early trauma care: preliminary results. J Trauma 2001;51(6):1037-41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Jennett PA, Andruchuk K. Telehealth: “real life” implementation issues. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 2001;64(3):169-74. [DOI] [PubMed]