Abstract

Borrelia burgdorferi, the causative agent of Lyme disease, is capable of forming biofilm in vivo and in vitro, a structure well known for its resistance to antimicrobial agents. For the formation of biofilm, signaling processes are required to communicate with the surrounding environment such as it was shown for the RpoN–RpoS alternative sigma factor and for the LuxS quorum-sensing pathways. Therefore, in this study, the wild-type B. burgdorferi and different mutant strains lacking RpoN, RpoS, and LuxS genes were studied for their growth characteristic and development of biofilm structures and markers as well as for their antibiotic sensitivity. Our results showed that all three mutants formed small, loosely formed aggregates, which expressed previously identified Borrelia biofilm markers such as alginate, extracellular DNA, and calcium. All three mutants had significantly different sensitivity to doxycyline in the early log phase spirochete cultures; however, in the biofilm rich stationary cultures, only LuxS mutant showed increased sensitivity to doxycyline compared to the wild-type strain. Our findings indicate that all three mutants have some effect on Borrelia biofilm, but the most dramatic effect was found with LuxS mutant, suggesting that the quorum-sensing pathway plays an important role of Borrelia biofilm formation and antibiotic sensitivity.

Keywords: Lyme disease, biofilm, sigma factor, quorum sensing, mucopolysaccharides, alginate, eDNA

Introduction

Lyme disease is the most common tick-borne illness caused by the species of bacteria belonging to the genus Borrelia [1]. According the Center of Disease Control within the United States, there are approximately 300,000 reported new Lyme disease cases every year while there are 65,000 people per year reported in Europe [2]. Patients diagnosed with Lyme disease are treated with certain antibiotics; however, recent studies demonstrated those antibiotics insufficient in eliminating certain forms of Borrelia in vitro [3–6]. Furthermore, several clinical [7–12] and in vivo studies [13–18] suggested that there are a potential resistant form which can withhold the antibiotic treatments and the attack of the immune system.

Numerous studies demonstrated that Borrelia burgdorferi can adopt diverse morphologies such as spirochete, round bodies (cysts and granules), and cell deficient forms depending on the condition of the environment they are exposed to [19–23]. These forms provide protective environment for Borrelia for adverse environmental conditions such as exposure to antibiotics, starvation, pH changes, or even high temperature [24–31]. In these defensive forms, B. burgdorferi becomes dormant and remains in this morphological state until it finds a more favorable condition when it returns to its spirochete form [27–31].

Recently, we provided evidences that B. burgdorferi sensu stricto and sensu lato stains are capable of forming another defensive form called biofilm both in vitro and in vivo [32, 34]. We also suggested that Borrelia biofilm formation could result in increased resistance to various antibiotics [3, 35]. Numerous studies showed that one of the most effective hiding places for a bacterial species is biofilm [36, 37]. Bacterial biofilms are organized communities of cells enclosed in a self-produced hydrated polymeric matrix called extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) which are complex mixtures of polysaccaharides, lipids proteins, nucleic acids, and other macromolecules [36–39]. Elimination of pathogenic bacteria in their biofilm form is very challenging because these sessile bacterial cells can endure not just the host immune responses but they are much less susceptible to antibiotics or any other industrial biocides than their individual planktonic counterparts [38, 39]. The biofilm resistance is based upon multiple mechanisms, such as incomplete penetration of certain antibiotics deep inside the matrix and/or inactivation of antibiotics by altered microenvironment within the biofilm and a highly protected resistant bacteria population called persisters [39].

When we evaluated the possibilities that observed Borrelia aggregates are indeed biofilm structures, its important biofilm traits like structural rearrangements and changes in development on different substrate matrices as well as the different components of the extracellular protective polymeric surface were studied [32, 33]. Our atomic force microscopic results provided evidence that, at various stages of aggregate development, rearrangements take place at multiple levels that lead to a continuously complex rearranging structure [32]. When the EPS of the aggregates was studied for potential exopolysaccharides, both sulfated and non-sulfated/carboxylated substrates were found; however, the majority was non-sulfated polymucosac-charide alginate. We provided evidence that the Borrelia EPS matrix also contains calcium and extracellular DNA [32, 33].

The important molecular pathways of Borrelia biofilm development are not known; therefore, to better understand the key components, the potential role of the several important signaling pathways was studied using wild-type and mutant B. burgdorferi sensu stricto strain 297.

The first pathway targeted was the RpoN–RpoS alternative sigma factor pathways, which can be found in many bacterial species, and they are involved in various cellular functions in response to different environmental stresses such as adverse temperature, high/low pH, high osmolarity, oxidative stress, high cell density, and carbon starvation [40]. They also control important virulence factors, and they are required for successful infection by many pathogenic bacteria [40]. The RpoN–RpoS pathway in B. burgdorferi has similar functions and responsible for sensing the environmental cues and activating RpoN encoded for σN which then regulates another alternative sigma factor, σS [41–45]. It was shown that this two-component RpoN–RpoS signal-transduction pathway controls the successful transmission of B. burgdorferi from the arthropod vector to the vertebrae host by regulating the expression of several known virulence factors such as outer surface proteins (OspA, OspB, OspC), decorin and fibronectin binding proteins as well as other proteins [44–46]. RpoS-mediated adaptive response is directly regulated by RpoN in B. burgdorferi, and together, they regulate over 100 different genes important in survival and stress responses as well as genes involved in the infectious cycles of B. burgdorferi [44–46].

Another important global regulatory pathway in bacteria is the quorum sensing bacterial intercommunication system that controls the expression of multiple genes in response to population density [47–50]. The system utilizing small signal molecules is called autoinducers. As the cell population density increases, autoinducers accumulate and cause a population-wide change in the expression of different genes involved in biofilm formation [49, 50]. It was previously demonstrated that B. burgdorferi utilizes the autoinducer-2 as one of its many ways of communication [51, 52]; however, one study challenged this observation [53]. The importance of this quorum-sensing pathway in biofilm development was shown for several pathogenic bacteria [54, 55]. For example, a luxS mutant of Streptococcus gordonii, a major component of dental plaque biofilm, was unable to form a mixed-species biofilm with another pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis [54]. Furthermore, the luxS mutant of Streptococcus spp. shows altered biofilm structure [55]. All these data suggest that LuxS quorum sensing system might play an important role in B. burgdorferi biofilm formation.

In this study, different B. burgdorferi strains including the wild-type 297 and several mutant strains such as RpoN, RpoS, and LuxS mutants were studied to evaluate the effect of the deletion of these genes on biofilm formations and biofilm specific markers as well as antibiotic sensitivity of B. burgdorferi in order to better understand the molecular pathways involved in biofilm formation and its antibiotic resistance. Several previously described Borrelia biofilm markers such as sulfated/non-sulfated poly-saccharides, alginate, extracellular DNA, and calcium were analyzed using immunohistochemistry and different staining techniques such as Spicer–Meyer, Alizarin, and extracellular DNA staining methods [32, 33]. The obtained results were visualized using various microscopic techniques such as dark and bright field, fluorescent, and differential interference contrast microscopy. In addition, the antibiotic sensitivity of the different forms (spirochete and biofilm) of the wild-type and mutant Borrelia strains was also evaluated.

In summary, the aim of this study to provide insight of the potential molecular pathways regulating biofilm formation in B. burgdorferi using different mutant cell lines with the final goal to better understand how B. burgdorferi forms biofilms. Data from this study might provide molecular targets in the future to the elimination of Borrelia biofilms for therapeutic use.

Materials and methods

Borrelia strains and culture conditions

Low passages (not more than three passages) of the wild-type 297 and mutant strains (RpoN, RpoS, and LuxS) of B. burgdorferi were generously provided by Michael V. Norgard’s research group (Department of Microbiology, University of Texas South-western Medical Center, Dallas, Texas). All strains were cultured in BSK-H (Barbour–Stoner–Kelly H) media with 6% rabbit serum (Peel-Freeze) by incubating at 33 °C and 5% CO2. For all the stock mutant strains, appropriate amounts of antibiotics were added to culture media, maintaining the mutation as described previously [41, 53]. To visualize biofilm formation, 1 × 106 cells/ml of wild-type and mutant strains of B. burgdorferi were inoculated in four-well chamber glass slides (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Lab-Tek II chamber glass slides) and were incubated for 7 days at 33 °C and 5% CO2. For biofilm quantitative assays, 1 × 106 cells/ml of wild-type and mutant strains of B. burgdorferi were inoculated in a 48-well tissue culture plates without any antibiotics and incubated for different times as described below.

Spicer & Meyer mucopolysaccharide staining

The wild-type 297, RpoN, RpoS, and LuxS mutant strains of B. burgdorferi were incubated as described above for 7 days. These aggregates were fixed on the slides with chilled (-20 °C) 1:1 mixture of acetone–methanol for 5 min. Aldehyde fuchsine solution (Sigma-Aldrich, 0.5% fuchsine dye, 6% acetaldehyde in 70% ethanol with 1% concentrated hydrochloric acid) was used to stain the biofilm for 20 min at room temperature (RT). The slides were dipped in 70% ethanol for 1 min and then rinsed with double distilled water for 1 min followed by staining with 1% Alcian blue 8GX (Sigma-Aldrich, dissolved in 3% acetic acid, pH 2.5) for 30 min at RT. Then, after rinsing the slides with double distilled water for 3 min, they were dehydrated with graded ethanol (50%, 70%, and 95%, 3 min each), then dipped in chilled xylene for 2 min, and were mounted with Permount media (Fisher Scientific).

Immunohistochemistry

Anti-alginate rabbit polyclonal IgG antibody (generous gift from G. Pier, Harvard University) was used to detect alginate expression by the aggregates of the wild-type 297, RpoN, RpoS, and LuxS mutant strains of B. burgdorferi. Biofilms were established and cultured as described above on four-well chamber slides for 7 days. The resulting structures were washed twice with PBS pH 7.4 and fixed in –20 °C using 100% methanol for 10 min and washed then twice with PBS pH 7.4 at RT. The specimens were then pre-incubated with 10% normal goat serum (Thermo Scientific) in PBS/0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA, Sigma) for 30 min at RT to block nonspecific binding of the secondary antibody. Then, the primary alginate antibody (1:100 dilution in dilution buffer: PBS pH 7.40 + 0.5% BSA) was applied and the slides were incubated overnight at 4 °C in a humidified chamber. After washing, specimens were incubated for ½ h with a 1:200 dilution of DyLight 594 conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Thermo Scientific) at RT. The slides were then washed thrice with PBS/0.5% BSA for 10 min, then incubated at 37 °C for 1 h with FITC-labeled Borrelia-specific polyclonal antibody (#73005 Thermo Scientific, diluted 1:50 in 1% BSA/1× PBS, pH 7.4). It was followed by further washing of slides thrice with PBS/0.5% BSA for 10 min at RT and counter-staining with 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for 10 min. Then, after washing it again with PBS pH 7.4 for 5 min at RT, the specimens were mounted using Perma-Fluor aqueous mounting medium and the obtained images were analyzed by fluorescent microscopy.

Alizarin calcium staining

In order to evaluate the presence of calcium on the surface of B. burgdorferi biofilms, 1 × 106 cells/ml of wild-type and mutant strains of Borrelia were grown in four-well chamber slides for 7 days, washed twice with PBS pH 7.4, fixed with ice-cold acetone for 5 min, and hydrated with graded alcohol and then stained with 2% Alizarin Red-S pH 4.2 (Sigma-Aldrich #A5533) (calcium-specific stain) for 4 min at RT and then were washed twice with double distilled water, dehydrated, and mounted with Permount media.

Extracellular DNA staining

To evaluate the extracellular DNA on the aggregates and individual spirochetes, 1 × 106 cells/ml of the wild-type 297 and RpoN, RpoS, and LuxS mutant strains of B. burg-dorferi were grown on four-well chamber slides for 7 days. The resulting aggregates washed twice with 1× TE buffer pH 8.0. The extracellular DNA was visualized by staining the biofilms with 1 μM DDAO [7-hydroxy-9H-(1,3-dichloro-9,9 dimethylacridin-2-one)] for 30 min at 37 °C in dark. The slides were then washed twice in 1× TE buffer pH 8.0 and mounted with PermaFluor aqueous mounting medium (Thermo Scientific).

Quantification of B. burgdorferi biofilms by crystal violet and total carbohydrate methods

The overall mass of the wild-type and mutant Borrelia biofilms was quantified by crystal violet methods described earlier [3, 34]. Briefly, seven-day-old aggregates (starting culture of 5 × 106 spirochetal cells) were scraped from the slides and collected by centrifugation method (5000g for 10 min at RT) and were stained with 0.01% (w/v) crystal violet 10 min at room temperature. The crystal violet stain was discarded by centrifugation method (5000g for 10 min at room temperature) and washed twice with sterile double-distilled water to remove all traces of crystal violet dye; then, 100 microliter 95% ethanol was added and incubated for 15 min at RT, and absorbance was measured at 595 nm using a BioTek spectrophotometer.

Total carbohydrate assay was also used to detect all forms of carbohydrates, including simple and complex saccharides, glycans, glycoproteins, and glycolipids as recent studies utilized successfully this method to measure and quantify the formation of extrapolysaccaharide layer of the biofilms as described earlier [32]. Briefly, seven-day-old aggregates (starting culture of 5 × 106 spirochetal cells) were scraped from the slides and collected by centrifugation method (5000g for 10 min at RT). After removing the supernatant, pellets were resuspended in double-distilled H20 (0.2 mL) followed by 5% aqueous phenol (wt/vol, Sigma) and 0.5 ml of concentrated sulfuric acid (H2SO4) and incubated for 30 min at RT. The developed yellow/orange color was measured at 485 nm using a BioTek spectrophotometer.

Baclight (Live/Dead) staining of Borrelia aggregates

To visualize live and dead cells for Borrelia aggregates, Baclight Live/Dead viability staining kit (Invitrogen) was used following manufacturer instructions. Briefly, a 1:1 mixture of SYTO9 and propidium iodide stain prepared above was added directly to the cultures in the four-chamber glass slides. The plate was then covered with aluminum foil and incubated for 15 min at RT. The four chambers were separated from the slide, washed, and mounted, and pictures were taken under the Leica microscope using fluorescent microscopy.

Spirochete growth inhibition assay

For all antimicrobial sensitivity assays, early log-phase spirochete cultures (5 × 105 cells/ml) from the wild-type and mutant strains were prepared in fresh medium without antibiotics and treated with different concentration of doxycyline for 48 h of treatment. Spirochete count was estimated by direct counting of live/motile spirochetes dark field microscopy. Six replicates were prepared for each treatment condition and three independent experiments were performed. Percentage of control was calculated by normalization of spirochete counts to the control treatment (no doxycycline) of the same strain.

Biofilm microbial sensitivity assay

Seven-day-old aggregates (starting culture of 5 × 106 spirochetal cells) in 1 mL suspension were treated with different concentration of doxycycline for 48 h days. Six replicates were prepared for each treatment condition, and three independent experiments were performed. After the treatment period, aggregates are quantified by crystal violet and sulfuric acid-phenol digestion total carbohydrate assay.

Statistical analysis

Each assay was carried out in three independent experiments with six replicates/condition, and numerical average was obtained for data presentation. Unpaired, two-tailed TTEST of unequal variance sample was performed to determine p values and statistical difference of two distinct sample sets. Differences were considered statistically significant when p values are <0.05.

Results

The growth pattern of B. burgdorferi wild-type and mutant strains

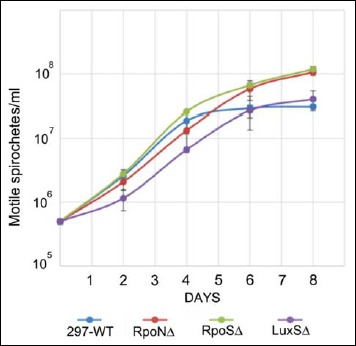

Evaluation of spirochete growth pattern in the wild-type and mutant B. burgdorferi 297 strains from day 0 to day 8 were performed by using 8 × 105/ml spirochetes and cultured as described in Materials and methods. The results of the obtained growth curves showed the standard three-phase growth: lag, exponential/log, and stationary growth (Fig. 1). Doubling time of all mutants (RpoNΔ, RpoSΔ, and LuxSΔ) was similar to that of the 297 wild-type strain. However, RpoN and RpoS mutants exhibited a delay in the transition from exponential/log phase to stationary growth, resulting in a higher maximum spirochete density: 1 × 108 compared to 5 × 107 in wild type. Figure 1 demonstrates that the RpoN mutant entered the stationary growth only on day 6, followed by RpoS mutant and wild-type 297 strains on day 4. On the other hand, LuxS mutant displayed a longer log phase compared to other strains but still had maximal spirochete density that was similar to wild-type strain on day 8.

Fig. 1.

The dynamic of the spirochetal growth of the wild-type and mutant B. burgdorferi 297 strains. Spirochetes at starting concentration at 8 × 105 cells/ml were cultured for 8 days as described in Materials and methods, and their cellular growth was evaluated by direct counting method of motile spirochetes using dark field microscopy. Each time point was carried out in three independent experiments with six replicates/condition

Analysis of aggregates formed by different mutant strains and wild type of B. burgdorferi strains

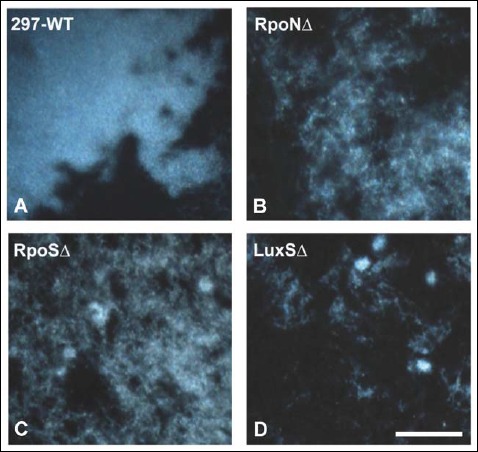

In the next experiments, the aggregates produced by the wild-type and mutant strains of B. burgdorferi were analyzed by dark field microscopy. Microscopic pictures of Borrelia strains on glass slides of the four-well chambers after 7 days of incubation of 5 × 106 cells/ml seeding concentration were compared for the presence of potential aggregate presence. The result showed that aggregates were formed in the 297 wild type as well as all three mutant cultures (Fig. 2). Morphologically, mutants seemed to exhibit a higher tendency to form loose, dispersed, and smaller aggregates than wild-type strain, especially LuxSΔ mutant strains, which showed a reticular mesh structure (Fig 2).

Fig. 2.

Representative images of aggregates for med by 297-WT (A), RpoNΔ (B), RpoSΔ (C), a nd LuxSΔ (D) strains of B. burgdorferi as depicted by dark field microscopy. 400× magnification, bar: 200 μm

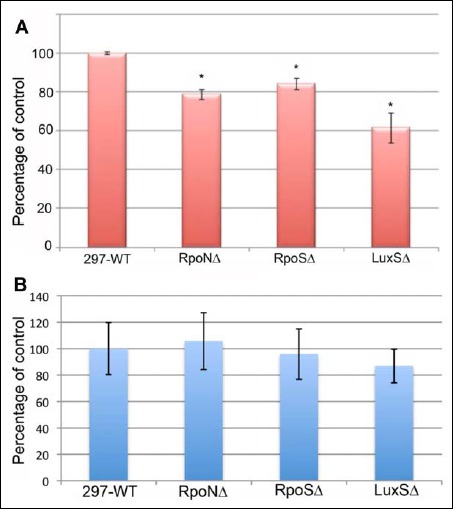

The quantification of aggregates formed by different mutant and wild-type strains was performed using crystal violet and total carbohydrate methods (Fig. 3A and B, respectively). When crystal violet method used to measure the total mass of the different aggregates, there was a significant reduction in the aggregate formation by RpoNΔ strain when compared to the wild-type 297 strain (22% reduction, p < 0.05). Comparing RpoSΔ and LuxSΔ aggregates to the wild-type strain, there was a 16% reduction and 39% in the total aggregate masses, respectively (p < 0.05). Interestingly, when total carbohydrate method was used to quantify the total carbohydrate component of the different aggregates, no significant difference could be found between the different mutant and wild-type strains (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Quantitative analysis of the total mass content of the aggregates formed by 297-WT, RpoNΔ, RpoSΔ, and LuxSΔ using crystal violet method (panel A) or total carbohydrate methods (panel B). Each assay was carried out in three independent experiments with six replicates/condition. *p values < 0.05 indicates statistical significance as related to the 297-WT control strain

Presence of specific biofilm markers on the surface of the aggregates of different B. burgdorferi strains

Wild-type 297 and various mutant strains of B. burgdorferi were tested for the presence of the previously described Borrelia biofilm specific markers such as sulfated/non-sulfated polysaccharides, alginate, calcium, and extracellular DNA.

1. Sulfated/non-sulfated mucins

Spicer & Meyer staining method was used to examine the presence of sulfated and non-sulfated/carboxylated mucins. Fuchsine stains the weakly acidic sulfomucins; purple coloration signifies strongly acidic sulfomucins, and alcian blue stain is specific for non-sulfated/carboxylated mucins. The aggregates formed by the wild-type and the different mutant strains (RpoNΔ, RpoSΔ, and LuxSΔ) of B. burgdorferi were stained as described in Materials and methods and imaged with dark field microscopy (Fig. 4). The colors developed in the center of the all three mutant strains showed some blue staining pattern (non-sulfated mucin), but contrary to wild-type 297, it was very dispersed. The periphery of the biofilms of all mutant strains studied stained mainly fuchsia purple color indicating sulfated mucins similar to the mucins found in the 297 wild-type strain.

Fig. 4.

Spicer & Meyer mucopolysaccharide staining by dark field microscopy of the wild-type 297 (A) and the mutant RpoN (B), RpoS (C), and LuxS (D) B. burgdorferi strains. Fuchsia color indicates weakly acidic sulfomucins; purple color indicates strongly acidic sulfomucins/sulfated proteoglycans; blue color indicates non-sulfated/carboxylated mucins. 400× magnification, bar: 200 μm

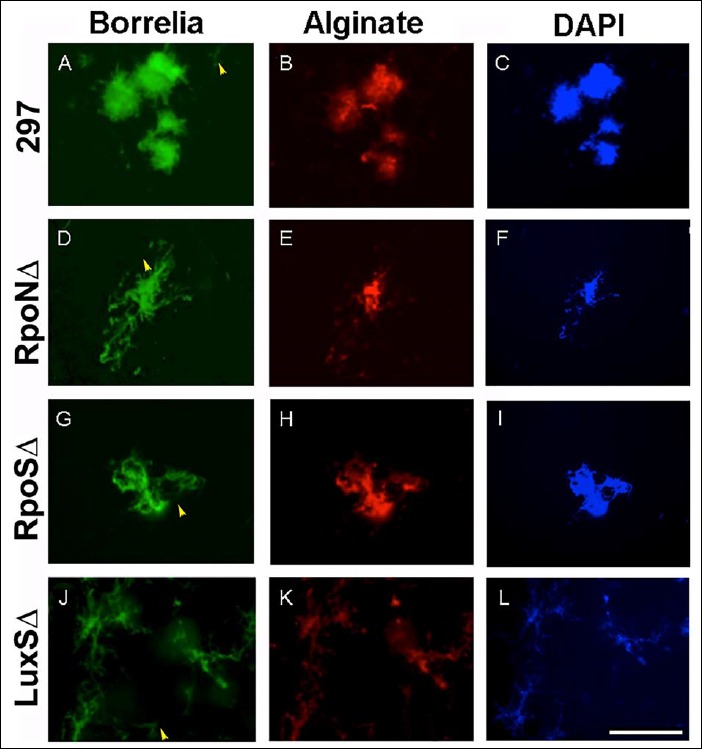

2. Alginate

Spicer & Meyer mucopolysaccharide staining results showed the presence of some non-sulfated mucins on all of the mutant strain biofilms. The non-sulfated mucins could indicate the presence of alginate as described previously for both B. burgdorferi B31 and 297 strains [32, 33]. The presence of alginate on the surface of the wild-type and the mutant strains of Borrelia species was confirmed by performing a previously published and validated method of double immunohistochemical staining with anti-alginate and anti-Borrelia antibodies (Fig. 5A–K). All mutant strains, RpoN, RpoS, and LuxS, were strongly stained with anti-Borrelia (Fig. 5D, G, and J) and anti-alginate antibodies (Fig. 5E, H, and K) similar to the wild-type 297 strains (Borrelia – green staining, Fig. 5A; alginate – red staining, Fig. 5B, respectively). Similarly to the wild-type strain, only the center of the aggregates stained with alginate antibody but not the surrounding spirochetes, indicating the specificity of the alginate staining technique as well as that fact that individual spirochetes do not express alginate (yellow arrow) as described in our previous reports [32, 34].

Fig. 5.

Immunohistochemical staining of wild-type 297, RpoN, RpoS, and LuxS mutant strains of B. burgdorferi with Borrelia-specific (green staining, panels A, D, G, and J) and alginate antibodies (red staining, panels B, E, H, and K) as described in Materials and methods. DAPI counterstain (blue staining, panels C, F, I, and L) indicates nuclear staining. Yellow arrowheads indicate spirochetes not stained with alginate. 400× magnification, bar: 200 μm

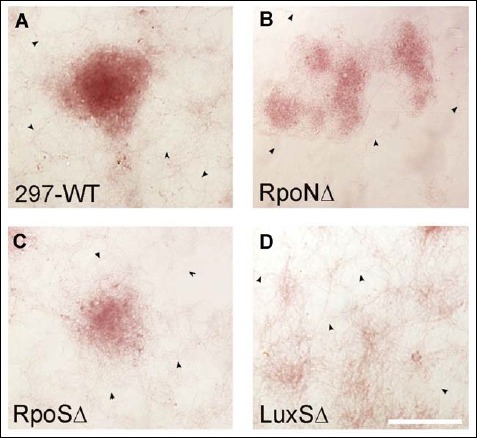

3. Presence of calcium

It was previously reported that alginate is associated with calcium to form insoluble calcium alginate and calcium was found on the surface of both B. burgdorferi B31 and 297 strains. The potential presence of calcium on the surface of different aggregates formed by the wild-type and the different mutant strains was tested by using Alizarin calcium staining method. The aggregates of all mutant strains RpoN, RpoS, and LuxS were stained red color with Alizarin Red-S stain similar to the wild-type 297 strain, indicating the presence of calcium in all strains studied (Fig. 6, panels A, B, C, and D). As previously reported for the wild-type 297 strain [32], the individual spirochetes were not stained with the calcium stain (indicated in Fig. 6 with black arrowheads), suggesting that calcium is specific to the surface of the aggregates formed by the wild-type and all mutants strains studied.

Fig. 6.

Aggregates of 297 (A), RpoN (B), RpoS (C), and LuxS (D) strains of B. burgdorferi stained with calcium specific stain, Alizarine, as described in Materials and methods. Red color indicates calcium analyzed by dark field microscopy. Black arrowheads indicate spirochetes not stained with Alizarine. 400× magnification, bar: 200 μm

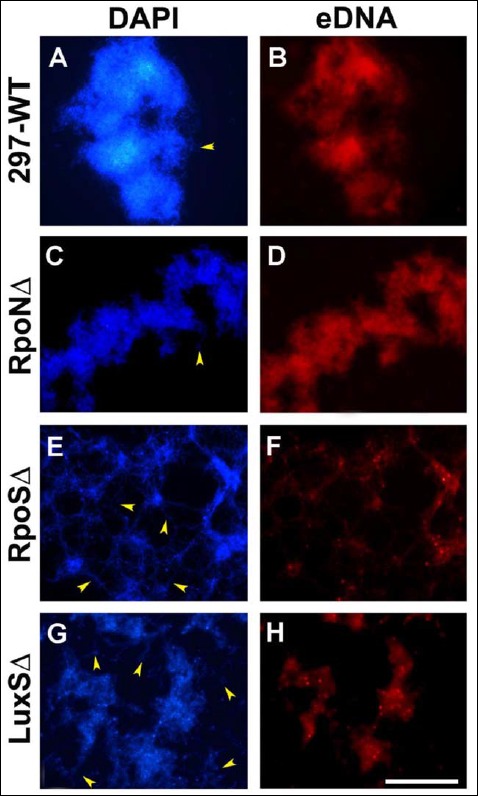

4. Extracellular DNA

Finally, the aggregates formed by the wild-type and mutant strains were examined for the presence of extracellular DNA (eDNA) as it was described for B. burgdorferi biofilm before [32]. For the detection of eDNA, a red fluo-rescent dye (7-hydroxy-9H-(1,3-dichloro-9,9-dimethylacridin-2-one (DDAO)) was used as reported previously [32]. The aggregate surfaces of the wild-type 297 and the RpoN, RpoS, and LuxS mutant strains were found to have significant amount of eDNA (Fig. 7, panels B, D, F, and H, respectively) whereas the surrounding individual spiro-chetes did not show staining for eDNA (indicated by yellow arrowheads). The DAPI nuclear counter stain images (Fig. 7, panels A, C, E, and G) depicted the size and morphology of the wild-type and mutant aggregates.

Fig. 7.

Aggregates of the wild-type 297, RpoN, RpoS, and LuxS strains of B. burgdorferi stained eDNA with DDAO fluorescent dye specific for extracellular DNA as described in Materials and methods (panels B, D, F, and H). DAPI nuclear counterstain was used to demonstrate the structure of the different aggregates (panels A, C, E, and G). Red fluorescent color indicates eDNA as depicted by fluorescent microscopy. Yellow arrowheads indicate spirochetes not stained with DDAO. 400× magnification, bar: 200 μm

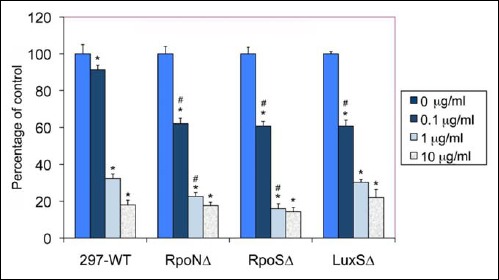

Effect of doxycyline on the wild-type and different mutant strains of B. burgdorferi

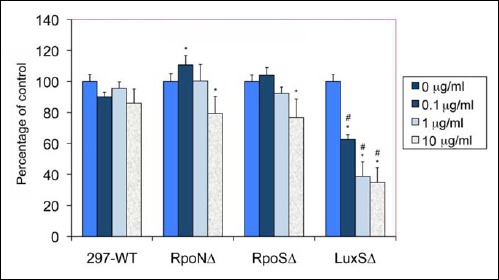

The goal of the next experiments is to compare the response of the early log phase spirochetal rich and stationary phase aggregate rich cultures of the wild-type and mutant strains to antibiotic stress. The effects of doxycycline on the spirochetal form of B. burgdorferi in the wild-type 297 and mutant strains (RpoNΔ, RpoSΔ, and LuxΔ) were studied using first early log phase spirochetes and direct counting of the live/motile cells with dark field microscope. Wild-type and mutant spirochetes were treated with various concentrations of doxycycline (ranging from published MIC and MBC concentrations) for 48 h, and the number of motile spirochetes in each treatment was counted. Spirochete numbers were normalized to their no antibiotic control of the same strains (0 μg/ml doxycycline) as depicted in Fig. 8. For all B. burgdorferi strains, doxycycline treatments that significantly reduced the live spirochete counts in every concentration were studied. More specifically, as doxycycline concentration increased from zero to 1 μg/ml, spirochetes decreased in number from 100% to 15–20% in every strain. Significant differences between the wild-type 297 and all mutant strains (RpoNΔ, RpoSΔ, and LuxΔ) were found (marked with #) when 0.1 μg/ml of concentration was used for treatment, while 1 μg/ml doxycyline concentration showed more significant results only in RpoNΔ and RpoSΔ strains but not in the LuxSΔ strain. Interestingly, however, 10 μg/ml doxycyline treatment did not produce significantly different results in any of the mutant strains compared to wild-type Borrelia strain.

Fig. 8.

Effect of different concentrations of doxycycline on the spirochetal form of wild-type 297 and RpoNΔ, RpoSΔ, and LuxSΔ strains of B. burgdorferi. The data analyzed by direct counting of the motile spirochetes using dark field microscopy. Each assay was carried out in three independent experiments with six sample replicates/condition, and the data were normalized to the no antibiotic treatment control for each strain. * indicates statistical significance as related to the corresponding no antibiotic control, and # indicates statistical significance as related to the 297-WT corresponding control sample

In the next step of experiments of the crystal violet, total carbohydrate assay and Baclight Live/Dead staining methods were used to study the effect of doxycycline on the viability of the stationary phase aggregates formed by the wild-type and mutant B. burgdorferi strains. Crystal violet measured the changes in total mass while total carbohydrate assay was used to detect changes in the extracellular polysaccharide layer of the aggregates before and after antibiotic treatment. Baclight Live/Dead staining method directly visualized the effect of the doxycycline by depicting the live (green) and dead (red) population in the aggregates of the different Borrelia strains. Seven-day-old aggregate rich cultures (starting culture of 5 × 106 spirochetal cells) in 1 mL suspension were treated with different concentration of doxycycline (ranging from 0 to 10 μg/ml concentration) for 48 h. Data from all antibiotic-treated samples were normalized to their no antibiotic control of the same strains (0 μg/ml doxycycline). When crystal violet method was used to evaluate doxycyline sensitivity of the wild-type and all three mutant strains, there were no significant differences found for any of the experimental condition for any strains studied (data not shown). However, when the total carbohydrate assay was used to assess doxycyline sensitivity, there were significant differences found in all three mutant strains compared to the wild-type control as depicted in Fig. 9. While doxycyline treatment of 297 wild-type strain did not reduce the extracellular polysaccharide layer significantly at any of the antibiotic concentrations, all there mutant strains (RpoNΔ, RpoSΔ, and LuxΔ) showed reduction of their extracellular poly-saccharide layer at 10 μg/ml (20–60%). The most dramatic effect, however, was found in the doxycyline sensitivity of the LuxSΔ strain, indicating that all three concentrations of doxycyline (0.1, 1, and 10 μg/ml) significantly reduced the extracellular polysaccharide layer (Fig. 9). The reduction was significant when it was compared to both the LuxSΔ control and 297 wild-type control (p value < 0.01). Furthermore, while the effect of 10 μg/ml of doxycyline was significant for the extracellular polysaccharide layer of the RpoNΔ and RpoSΔ strains when it compared to their no treatment controls (p value < 0.05), it was not significantly different than the wild-type control data with the same doxycyline treatment.

Fig. 9.

Effect of different concentrations of doxycycline 48 h treatment on the biofilm form of wild-type 297 and RpoNΔ, RpoSΔ, and LuxSΔ mutant strains of B. burgdorferi after 48 h treatment analyzed by total carbohydrate methods as described in Materials and methods. Each assay was carried out in three independent experiments with six sample replicates/condition, and the data were normalized to the no antibiotic treatment control for each strain. * indicates statistical significance as related to the corresponding no antibiotic control, and # indicates statistical significance as related to the 297-WT corresponding control sample

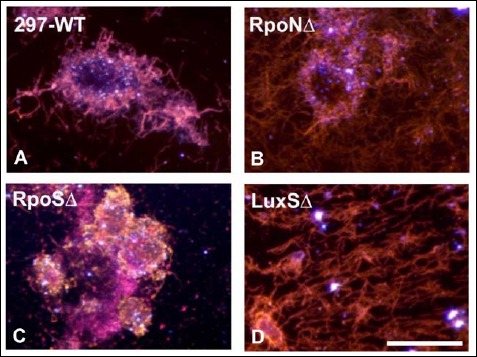

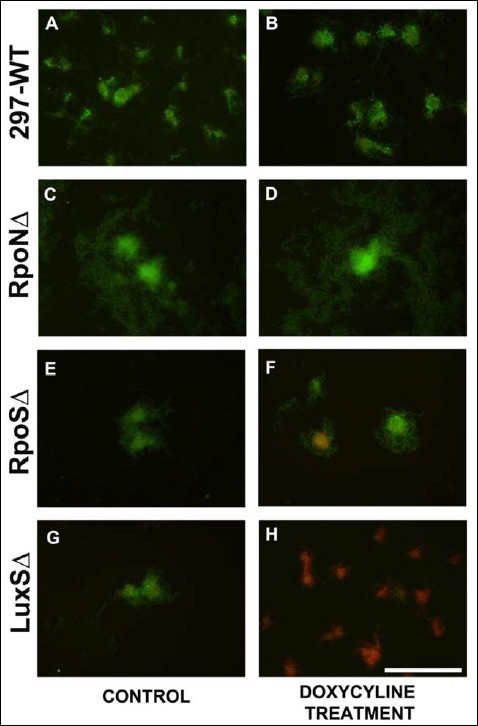

To further confirm the quantitative data of the doxy-cyline effect on the different strains, Baclight Live/Dead analyses were performed on the 10 μg/ml doxycyline-treated cultures after 48 h. Figure 10 shows representative microscopic images obtained from the untreated and doxycycline-treated wild-type 297 and mutant B. burgdorferi strains (RpoNΔ, RpoSΔ, and LuxΔ) strains depicting membrane-intact (live) cells in green and membrane-permeable (dead) cells in red. In all of the no treatment controls (Fig. 10, panels A, C, E, and G), majority of the cells show green staining indicating live cells with a small portion of the cells stained red indicating dead cells. In the doxycyline-treated cultures, the majority of the cells stained green for the wild-type 297 and the RpoNΔ mutant cells show no significant difference from their no treatment control cultures. For RpoSΔ strain, there were a portion of the aggregates (<10%) which showed higher numbers of dead cells, but overall, the difference from the no treatment control was not significant. On the other hand, majority (>95%) of the aggregates of the LuxS strains showed mainly red/dead cells after 48 h of antibiotic treatment, suggesting a greater sensitivity to doxycyline than the wild-type 297 or the Rpo gene mutant strains.

Fig. 10.

Representative Baclight Live/Dead images of the effect of doxycycline on the aggregate forms of wild-type 297 (panels A and B) and RpoNΔ (panels C and D), RpoSΔ (panels E and F), and LuxSΔ (panels G and H) strains of Borrelia burgdorferi after 48 h treatment with 0 (panels A, C, E, and G) or 10 μg/ml (panels B, D, F, and H) of doxycyline as analyzed using fluorescent microscopy. Green color = live cells, red color = dead cells, 400× magnification, bar: 200 μm

Discussion

In this study, the possible biofilm formation of several mutant strains of B. burgdorferi was investigated to better understand the roles of different genes–intracellular pathways in the development and characteristic of Borrelia biofilm.

Building a biofilm community requires intra- and extracellular communication processes and is considered a survival response in bacteria [36–38]. Rpo transcriptional factor genes are known to control bacterial changes in response to environment stimuli [40]; LuxS quorum-sensing roles in biofilm formation and antibiotic response have been established in some research with other organisms [47–50]. This study attempted to explore the possible roles of Rpo genetic regulation and LuxS quorum communication pathways in Borrelia biofilm formation and its antibiotic sensitivity.

Growth patterns of planktonic spirochetes were compared between the wild-type and the different mutant strains. The results showed that RpoN, RpoS, and LuxS mutant strains had some deviations from wild-type strains, including that mutants lacking Rpo genes had longer time to response to the inadequate nutrient environment, resulting in a longer exponential growth period and, ultimately, the higher maximum spirochete density. LuxS mutant reached the stationary phase later, suggesting that LuxS could also have a potential role in the growth of B. burgdorferi.

Furthermore, in spite of lacking important genes responsible for regulating bacterial environmental responses and quorum-sensing communication, all three mutants readily formed biofilm-like aggregates in the stationary phase of growth. Morphologically, all mutants but especially the LuxS mutant seemed to exhibit a higher tendency to form smaller and looser aggregates than the wild-type strain. This result is in good agreement with a previous study in which mutation in rpoS did not eliminate the biofilm formation in Escherichia coli during exponential phase of growth [54, 55].

The size of the aggregates was also quantified in this study using crystal violet staining as well as total carbohydrate quantitation methods. The obtained data indicated that mutant aggregates were significantly smaller than the wild-type ones; however, those smaller aggregates had similar amounts of total carbohydrate, suggesting that the mutants might produce higher amounts of protective mucopolysaccharide layers. This finding is in good agreement with a study, in which Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutant had increased matrix production [56].

Further investigation of specific biofilm markers in the mutant strains showed that all three mutant strains produce significant amounts of biofilm specific markers such as sulfated/non-sulfated polysaccharides, alginate, calcium, and eDNA, similar to what was found and reported previously to the wild-type B. burgdorferi strains [52, 53]. These results strongly suggest that the aggregates formed by the mutant strains studied are indeed biofilms.

It might be surprising at first that Borrelia strains lacking RpoN, RpoS, and LuxS genes still can form biofilms which could have most of the main phenotypes of the wild-type biofilm. However, in earlier studies, it was reported that mutant strains of RpoN in E. coli K12 and Enterococcus faecalis also formed biofilms [57, 58]. RpoS mutant strain was also observed to form biofilm in E. coli ZK126 stains as well as in P. aeroginosa [59, 60]. For LuxS mutant strain in Streptococccus sp., a report suggested that the mutant LuxS mutant could form biofilm; however, it depends on the in vitro culture condition [61, 62].

One of main differences found for the Borrelia mutant biofilms was the reduced size compared to wild-type 297. The RpoN mutant strain of B. burgdorferi formed a biofilm which was 22% less in size than the wild-type 297. Previously, it was reported that the deletion of RpoN gene in E. coli K12 strains increased the biofilm formation by 40–60%, and also in E. faecalis, the RpoN mutant strain was observed to form robust biofilms [57, 58]. In this study, we showed that RpoS mutant strain of B. burgdorferi had 16% reduction in the biofilm formation compared to wild-type similar to the deletion of RpoS gene in E. coli ZK126 which reduced the biofilm size by 50% [59]. LuxS mutant strain of B. burgdorferi formed biofilm which showed 39% significant reduction in size which agrees with the report on Streptococccus sp. LuxS mutants [61].

Also, there were slight morphological differences observed in the biofilms formed by the RpoN, RpoS, and LuxS Borrelia mutant strains compared to wild-type strain. The biofilm formed by the wild-type 297 strain shows a compact biofilm mass which resembles the biofilm of B31 strain of B. burgdorferi as described in our recently published paper [32, 33]. The biofilm formed by RpoN mutant was relatively less compact compared to wild-type biofilms while RpoS mutant strain formed many loose and dispersed small aggregates unlike the wild-type 297. Interestingly, the biofilm formed by RpoS mutant of P. aeroginosa was denser and thicker than the wild type [60]. The biofilm formed by LuxS mutant strain of Borrelia represents a very loose reticular mesh. Undifferentiated and loosely-connected biofilms were also found to form in LuxS mutant strain of Shewanella oneidensis covering the entire glass surface uniformly unlike the wild type which forms compact biofilms with significant amounts of spaces in between [63].

Biofilms were demonstrated to be responsible for the antibiotic resistance in many species [36–39]. Therefore, besides examining the growth dynamics and biofilm development of the different mutant strains of B. burgdorferi, this research attempted to compare the responses of wild-type and mutant strains to antibiotic stress. Early log phase spirochetes and stationary phase aggregate rich cultures were exposed to varying concentrations of doxycycline and compared among all strains studies. In a good agreement with several recent studies using wild-type B. burgdorferi 31 strain, only the early log phase spirochetes of the wild-type 297 strains were sensitive to doxycyline treatment but not the aggregate rich stationary phase cells [3–6]. When the doxycyline sensitivity of the early log phase spirochetes of the wild-type strain and all of the three mutant strains was compared, the obtained results indicated significantly higher sensitivity of all three mutant strains to low MIC dose of doxycyline (0.1 μg/ml) than the wild-type strain. Interestingly, however, there was no difference in the doxycyline sensitivity of the early log phase spirochetes among the strains at higher MBC level concentration.

Similarly, doxycyline sensitivity of the stationary aggregate rich cultures of wild-type and Rpo mutants was not significantly different at lower doses. In contrary, however, antibiotic sensitivity of the LuxS Borrelia mutant dramatically greater than the wild-type mutant at all concentrations was studied. These later results were also confirmed by microscopical analyses of the live and dead cells of the mutant strains as demonstrated by Baclight Live/Dead staining. In summary, the antibiotic sensitivity studies of the mutant strains confirmed that all three genes have some effect on antibiotic sensitivity in some extent but LuxS mutant has the most significant effect.

Involvement of LuxS signaling pathway in antibiotic sensitivity was proven for S. anginosus species, in which the mutant demonstrated increased susceptibility to erythromycin and ampicillin [64]. Furthermore, P. aeruginosa mutants defective in interspecies quorum sensing produced weaker biofilms that were more sensitive to detergents, while Streptococcus mutans mutants defective in interspecies cell signaling generated stronger biofilms that were more resistant to detergents [61, 65].

In our recent studies, we also investigate the potential biofilm formation of several other B. burgdorferi mutants such as the Hk1/Rrp1 and recA mutants that regulate the cyclic di-GMP and the recombination events, respectively [38, 66, 67]. Those two molecular pathways were already implicated to be important in biofilm formation for other bacterial species [38]; however, our preliminary findings show no differences from the wild-type strains in regards of different aspects of biofilm development and characteristic (data not shown).

In summary, our findings strongly suggest that several alternative pathways could regulate B. burgdorferi biofilm formation, a result that indicates that it is a very important survival mechanism for this bacterium. Findings for the potential importance of the LuxS quorum-sensing pathways for Borrelia biofilm development and antibiotic sensitivity merit further investigation of this pathway.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Michael V. Norgard’s research group (Department of Microbiology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas) for the Borrelia mutant strains and Dr. Gerald Pier (Harvard University) for the alginate antibody.

We also thank the Lymedisease.org and the Schwartz Research foundation for the donation of the Leica DM2500 microscope as well as the Hamamatsu ORCA Digital Camera.

Funding Statement

Funding sources: This work was supported by grants from the University of New Haven, Tom Crawford’s Leadership Children Foundation, National Philanthropic Trust, Alyssa Wartman Funds to ES, and postgraduate fellowship from NH Charitable Foundation to PAST.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: BSA, bovine serum albumin; BSK-H, Barbour–Stoner–Kelly H; DAPI, 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; DDAO, 7-hydroxy-9H-(1,3-dichloro-9,9 dimethylacridin-2-one; DIC, differential interference contract microscopy; EDTA, ethylenediami-netetraacetic acid; EPS, extracellular polymeric substances; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; RT, room temperature; TE, Tris–EDTA

References

- 1.Barbour AG, Hayes SF: Biology of Borrelia species. Microbiol Rev 50, 381–400 (1986) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mead PS: Epidemiology of Lyme disease. Infect Dis Clin North Am 29, 187–210 (2015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sapi E, Kaur N, Anyanwu S, Datar A, Patel S, Rossi JM, Stricker RB: Evaluation of in vitro antibiotic susceptibility of different morphological forms of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Drug Resist 4, 97–113 (2011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feng J, Wang T, Shi W, Zhang S, Sullivan D, Auwaerter PG, Zhang Y: Identification of novel activity against Borrelia burgdorferi persisters using an FDA approved drug library. Emerg Microbes Infect 3, 1–8 (2014) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feng J, Auwaerter PG, Zhang Y: Drug combinations against Borrelia burgdorferi persisters in vitro: eradication achieved by using daptomycin, cefoperazone and doxycycline. PLoS One 10, 1–15 (2015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feng J, Weitner M, Shi W, Zhang S, Zhang Y: Eradication of biofilm-like microcolony structures of Borrelia burgdorferi by daunomycin and daptomycin but not mitomycin C in combination with doxycycline and cefuroxime. Frontiers in Microbiol 7, 62 (2016) doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.00062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liegner KB, Shapiro JR, Ramsay D, Halperin AJ, Hogrefe W, Kong L: Recurrent erythema migrans despite extended antibiotic treatment with minocycline in a patient with persisting Borrelia burgdorferi infection. J Am Acad Dermatol 28, 312–314 (1993) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dumler JS: Molecular diagnosis of Lyme disease: review and meta-analysis. Mol Diagn 6, 1–11 (2001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steere AC, Angelis SM: Therapy for Lyme arthritis: strategies for the treatment of antibiotic-refractory arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 54, 3079–3086. (2006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stricker RB, Johnson L. Lyme disease: the next decade. Infect Drug Resist 4, 1–9 (2011) doi:10.2147/IDR.S15653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klempner MS, Baker PJ, Shapiro ED, Marques A, Dattwyler RJ, Halperin JJ, Wormser GP: Treatment trials for post-lyme disease symptoms revisited. Am J Med 126, 665–669 (2013) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berndtson K: Review of evidence for immune evasion and persistent infection in Lyme disease. Int J Gen Med 6, 291–306 (2013) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brorson Ø, Brorson S-H, Scythes J, MacAllister J, Wier A, Margulis L: Destruction of spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi round-body propagules (RBs) by the antibiotic tigecycline. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106, 18656–18661 (2009) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Straubinger RK, Summers BA, Chang YF, Appel MJ: Persistence of Borrelia burgdorferi in experimentally infected dogs after antibiotic treatment. J Clin Microbiol 35, 111–116 (1997) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hodzic E, Feng S, Holden K, Freet KJ, Barthold SW: Persistence of Borrelia burgdorferi following antibiotic treatment in mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52, 1728–1736 (2008) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barthold SW, Hodzic E, Imai DM, Feng S, Yang S, Luft BJ: Ineffectiveness of tigecycline against persistent Borrelia burgdorferi. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54, 643–651 (2010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Embers ME, Barthold SW, Borda JT, Bowers L, Doyle L, Hodzic E, Jacobs MB, Hasenkampf NR, Martin DS, Narasimhan S, Phillippi-Falkenstein KM, Purcell JE, Ratterree MS, Philipp M: Persistence of Borrelia burgdorferi in rhesus macaques following antibiotic treatment of disseminated infection. PLoS One 7, e29914 (2012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hodzic E, Imai D, Feng S, Barthold SW: Resurgence of persisting non-cultivable Borrelia burgdorferi following antibiotic treatment in mice. PLoS One 23, 1–11 (2014) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kurtti TJ, Munderloh UG, Johnson RC, Ahlstrand GG: Colony formation and morphology in Borrelia burgdorferi. J Clin Microbiol 25, 2054–2058 (1987) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hampp EG: Further studies on the significance of spirochetal granules. J Bacteriol 62, 347–349 (1951) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mursic VP, Wanner G, Reinhardt S, Wilske B, Busch U, Marget W: Formation and cultivation of Borrelia burgdorferi spheroplast-L-form variants. Infection 24, 218–226 (1996) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacDonald AB: Spirochetal cyst forms in neurodegenerative disorders, … hiding in plain sight. Med Hypotheses 67, 819–832 (2006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.MacDonald AB: Borrelia burgdorferi tissue morphologies and imaging methodologies. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 32, 1077–1082 doi: 10.1007/s10096-013-1853-5 (2013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alban PS, Johnson PW, Nelson DR: Serum-starvation-induced changes in protein synthesis and morphology of Borrelia burgdorferi. Microbiology 146, 119–127 (2000) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gruntar I, Malovrh T, Murgia R, Cinco M: Conversion of Borrelia garinii cystic forms to motile spirochetes in vivo. APMIS 109, 383–388 (2001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brorson O, Brorson SH. In vitro conversion of Borrelia burgdorferi to cystic forms in spinal fluid, and transformation to mobile spirochetes by incubation in BSK-H medium. Infection 26, 144–150 (1998) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murgia R, Cinco M: Induction of cystic forms by different stress conditions in Borrelia burgdorferi. APMIS 112, 57–62 (2004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brorson Ø, Brorson SH: An in vitro study of the susceptibility of mobile and cystic forms of Borrelia burgdorferi to tinidazole. Int Microbiol 7, 139–42 (2004) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miklossy J, Kasas S, Zurn AD, McCall S, Yu S, McGeer PL: Persisting atypical and cystic forms of Borrelia burgdorferi and local inflammation in Lyme neuroborreliosis. J Neuroinflammation 5, 1–18 (2008) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kersten A, Poitschek C, Rauch S, Aberer E: Effects of penicillin, ceftriaxone, and doxycycline on morphology of Borrelia burgdorferi. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 39, 1127–1133 (1995) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brorson Ø, Brorson S-H, Scythes J, MacAllister J, Wier A, Margulis L: Destruction of spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi round-body propagules (RBs) by the antibiotic tigecycline. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106, 18656–18661 (2009) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sapi E, Bastian SL, Mpoy CM, Scott S, Rattelle A, Pabbati N, Poruri A, Burugu D, Theophilus PA, Pham TV, Datar A, Dhaliwal NK, MacDonald A, Rossi MJ, Sinha SK, Luecke D: Characterization of biofilm formation by Borrelia burgdorferi in vitro. PLoS One 7, e48277 (2012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Timmaraju VA, Theophilus PAS, Balasubramanian K, Shakih S, Luecke DF, Sapi E: Biofilm formation by Borrelia sensu lato. FEMS Microbiol Lett 362, (2015) doi:10.1093/femsle/fnv120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sapi E, Balasubramanian K, Poruri A, Maghsoudlou JS, Theophilus PAS, Socarras KM, Timmaraju AV, Filush KR, Gupta K, Shaikh S, Luecke DF, MacDonald A, Zelger B: Evidence of in vivo existence of borrelia biofilm in borrelial lymphocytomas. Eur J Microbio Immunol 6, (2016) doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1556/1886.2015.00049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Theophilus PAS, Victoria MJ, Socarras KM, Filush KR, Gupta K, Luecke DF, Sapi E: Effectiveness of Stevia rebaudiana whole leaf extract against the various morphological forms of Borrelia burgdorferi in vitro. Eur J of Microbiol and Immunol 5, 268–280 (2015) doi: 10.1556/1886.2015.00031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Costerton JW, Stewart PS, Greenberg EP: Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science 284, 1318–1322 (1999) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Donlan RM, Costerton JW: Biofilms: survival mechanisms of clinically relevant microorganisms. Clin Microbiol Rev 15, 167–93 (2002) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Flemming H-C, Wingender J: The biofilm matrix. Nat Rev Micro 8, 623–633 (2010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Song T, Duperthuy M, Wai SN: Sub-optimal treatment of bacterial biofilms. Antibiotics 5, 23 (2016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kazmierczak MJ, Wiedmann M, Boor KJ: Alternative sigma factors and their roles in bacterial virulence. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 69, 527–543 (2005) doi:10.1128/MMBR.69.4.527-543.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hübner A, Yang X, Nolen DM, Popova TG, Cabello FC, Norgard MV: Expression of Borrelia burgdorferi OspC and DbpA is controlled by a RpoN–RpoS regulatory pathway. Proc Natl Acad of Sci USA 98, 12724–12729 (2001) doi: 10.1073/pnas.231442498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Caimano MJ, Eggers CH, Gonzalez CA, Radolf JD: Alternate sigma factor RpoS is required for the in vivo-specific repression of Borrelia burgdorferi plasmid lp54-borne ospA and lp6.6 genes. J Bacteriol 187, 7845–7852 (2005) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith AH, Blevins JS, Bachlani GN, Yang XF, Norgard MV: Evidence that RpoS (σS) in Borrelia burgdorferi is controlled directly by RpoN (σ54/σN). J Bacteriol 189, 2139–2144 (2007) doi:10.1128/JB.01653-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ouyang Z, Blevins GS, Norgard MV: Transcriptional interplay among the regulators Rrp2, RpoN and RpoS in Borrelia burgdorferi. Microbiol 154, 2641–2658 (2008) doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/019992-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ouyang Z, Narasimhan S, Neelakanta G, Kumar M, Pal U, Fikrig E, Norgard MV: Activation of the RpoN–RpoS regulatory pathway during the enzootic life cycle of Borrelia burgdorferi. BMC Microbiol 12, 44 (2012) doi:10.1186/1471-2180-12-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dunham-Ems SM, Caimano MJ, Eggers CH, Radolf JD: Borrelia burgdorferi requires the alternative sigma factor RpoS for dissemination within the vector during tick-to-mammal transmission. PLoS Pathog 8(2), e1002532 (2012) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Waters CM, Bassler BL: Quorum sensing: cell-to-cell communication in bacteria. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 21, 319–346 (2005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bassler BL: How bacteria talk to each other: regulation of gene expression by quorum sensing. Curr Op in Microbiol 2, 582–587 (1999) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schauder S, Shokat K, Surette MG, Bassler BL: The LuxS family of bacterial autoinducers: biosynthesis of a novel quorum-sensing signal molecule. Mol Microbiol 41, 463–476 (2001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.De Keersmaecker SCJ, Sonck K, Vanderleyden J: Let LuxS speak up in AI-2 signaling. Trends in Microbiol 14, 114–119 (2006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stevenson B, Babb K: LuxS-mediated quorum sensing in Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme disease spirochete. Infect Immun 70, 4099–4105 (2002) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Babb K, von Lackum K, Wattier RL, Riley SP, Stevenson B: Synthesis of autoinducer 2 by the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi. J Bacteriol 187, 30793–087 (2005) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hübner A, Revel AT, Nolen DM, Hagman KE, Norgard MV: Expression of a luxS gene is not required for Borrelia burgdorferi infection of mice via needle inoculation. Infect Immun 71(5), 2892–2896 (2003) doi:10.1128/IAI.71.5.2892-2896.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McNab R, Ford SK, El-Sabaeny A, Barbieri B, Cook GS, Lamont RJ: LuxS-based signaling in Streptococcus gordonii: autoinducer 2 controls carbohydrate metabolism and biofilm formation with Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Bacteriol 185, 274–284 (2003) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yoshida A, Ansai T, Takehara T, Kuramitsu HK: LuxS-based signaling affects Streptococcus mutans biofilm formation. Appl Environ Microbiol 71, 2372–2380 (2005) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Colvin KM, Irie Y, Tart CS, Urbano R, Whitney JC, Ryder C, Howell PL, Wozniak DJ, Parsek MR: The Pel and Psl polysaccharides provide Pseudomonas aeruginosa structural redundancy within the biofilm matrix. Environ Microbiol 14(8), (2012) doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02657.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Belik AS, Tarasova NN, Khmel IA: Regulation of biofilm formation in Escherichia coli K12: Effect of mutations in the genes HNS, STRA, LON, and RPON. Mol Gen, Microbiol Virol 23, 159 (2008) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vijayalakshmi S. Iyer, Lynn E. Hancock: Deletion of σ54 (rpoN) alters the rate of autolysis and biofilm formation in Enterococcus faecalis. J Bacteriol 94, 368375 (2012) doi:10.1128/JB.06046-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Adams JL, Mclean RJC: Impact of rpoS deletion on Escherichia coli biofilms. Appl Environ Microbiol 65, 4285–4287 (1999) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Irie Y, Starkey M, Edwards AN, Wozniak DJ, Romeo T, Parsek MR: Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm matrix polysaccharide Psl is regulated transcriptionally by RpoS and post-transcriptionally by RsmA. Mol Microbiol 78, 158–172 (2010) doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07320.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wen ZT, Burne RA: Functional genomics approach to identifying genes required for biofilm development by Streptococcus mutans. Appl Environ Microbiol 68, 1196–1203 (2002) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Merritt J, Qi F, Goodman SD, Anderson MH, Shi W: Mutation of LuxS affects biofilm formation in Streptococcus mutants. Infect Immun 71, 1972–1979 (2003) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bodor AM, Jansch L, Wissing J, Wagner-Dobler: The luxS mutation causes loosely-bound biofilms in Shewanella oneidensis. BMC Res Notes 4, 180 (2011) doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ahmed NAAM, Peterson FC, Scheie AA: AI-2 quorum sensing affects antibiotic susceptibility in Streptococcus anginosus. J Antimicron Ther 60, 49–53 (2007) doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Davies DG, Parsek MR, Pearson JP, Iglewski BH, Costerton JW, Greenberg EP: The involvement of cell-to-cell signals in the development of a bacterial biofilm. Science 280, 295–298 (1998) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Caimano MJ, Dunham-Ems S, Allard AM, Cassera MB, Kenedy M, Radolf JD: Cyclic di-GMP modulates gene expression in Lyme disease spirochetes at the tick-mammal interface to promote spirochete survival during the blood meal and tick-to-mammal transmission. Infect Immun 83, 3043–3060 (2015) doi:10.1128/IAI.00315-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liveris D, Mulay V, Schwartz I: Functional properties of Borrelia burgdorferi recA. J Bacteriol 186, 2275–2280 (2004) doi:10.1128/JB.186.8.2275-2280.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]