Summary

Background

Global HIV programs continue to experience challenges achieving the high rates of HIV testing and treatment needed to optimize health and reduce transmission. Botswana represents a useful “demonstration case” in assessing the feasibility of achieving the new UNAIDS targets for 2020: 90% of all persons living with HIV knowing their status, 90% of these individuals receiving sustained antiretroviral treatment (ART), and 90% of those on ART having virologic suppression (“90–90–90”).

Methods

A population-based random sample of individuals was recruited and interviewed in 30 rural and peri-urban communities from October 2013 to November 2015 in Botswana as part of a large, ongoing PEPFAR-funded community-randomized trial designed to evaluate the impact of a combination prevention package on HIV incidence. A random sample of approximately 20% of households in each of these 30 communities was selected. Consenting household residents aged 16–64 years who were Botswana citizens or spouses of citizens responded to a questionnaire and had blood drawn for HIV testing in absence of documentation of positive HIV status. HIV-1 RNA testing was performed in all HIV-infected participants, regardless of treatment status.

Findings

Eighty-one percent of enumerated eligible household members took part in the survey (10% refused and 9% were absent). Among 12,610 participants surveyed, 3,596 (29%) were HIV infected; 2,995 (83·3%) of these individuals already knew their HIV status. Among those who knew their HIV status, 2,617 (87·4%) were currently receiving ART (this represented 95% of those eligible for ART by current Botswana national guidelines, and 73% of all HIV-infected persons). We obtained an HIV-1 RNA result in 99·7% of HIV-infected participants. Of the 2,609 individuals currently receiving ART with a viral load measurement, 2,517 (96·5%) had HIV-1 RNA ≤400 copies/mL. Overall, 70·2% of HIV-infected persons had virologic suppression, close to the UNAIDS target of 73%. Results of three sensitivity analyses to account for possible uncertainty due to non-participation and under-representation of urban areas, revealed somewhat lower, but nevertheless remarkably high 90–90–90 coverage.

Interpretation

Botswana, a resource-constrained setting with high HIV prevalence, appears to have achieved very high rates of HIV testing, treatment coverage, and virologic suppression for those on ART in this population-based survey, despite the Botswana ART initiation threshold of ≤350 cells/mm3. These findings provide evidence that the UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets, while ambitious, are achievable even in resource-constrained settings with high HIV burden.

Funding

The United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Background

In 2014, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) proposed new targets directed at ending the AIDS epidemic, namely that, by 2020, 90% of all HIV-infected people will know their HIV status; 90% of those diagnosed with HIV infection will receive sustained combination antiretroviral therapy (ART); and 90% of all people receiving ART will have viral suppression.1 The rationale underpinning these targets is related both to the health benefit of ART to infected individuals,2,3 and to the potent effect of ART on reducing sexual4-6 and perinatal7,8 HIV transmission.

However, uncertainty remains as to whether these ambitious UNAIDS targets are achievable, particularly in high-HIV-burden, resource-constrained settings such as sub-Saharan Africa. According to UNAIDS, in sub-Saharan Africa in 2013, only 45% of HIV-infected adults knew their HIV status; however, 86% of diagnosed persons were on ART, and an estimated 76% of persons on ART achieved virologic suppression.9 This translates to 29% of all HIV-positive persons in sub-Saharan Africa having virologic suppression, compared with the overall UNAIDS target of 73%. Recent estimates of progress toward reaching this target range from 68% in Switzerland,10 62% in Australia,11 and 30% in the United States,12 down to 9% in Russia.13

Botswana is a middle-income country with a stable democracy, high HIV prevalence (25·2% of persons 15–49 years),14 and a mature public ART program that started in 2002. Per current Botswana guidelines, HIV-infected citizens receive free 3-drug ART from decentralized health clinics if they have a CD4 count ≤350 cells/mm3, a WHO stage III or IV illness (including recent tuberculosis diagnosis), a history of cancer, or are pregnant or breastfeeding (regardless of CD4 count). We have a unique opportunity to assess population-level coverage of HIV testing, ART, and virologic suppression in the context of a large, ongoing cluster-randomized combination prevention study that is underway in 30 communities across Botswana.

Methods

Overall BCPP study design and procedures

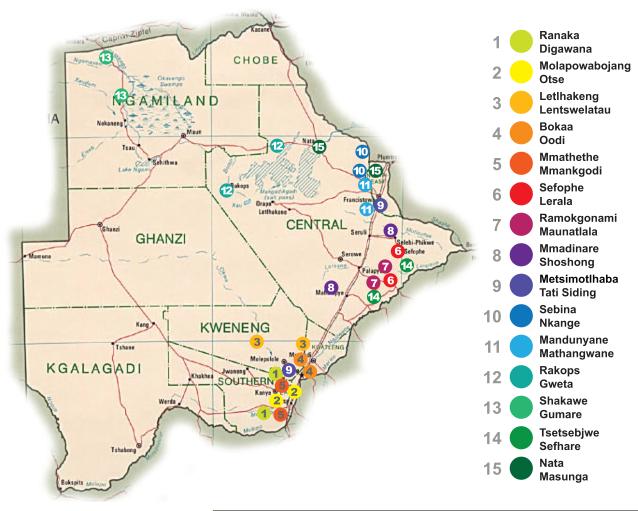

The Botswana Combination Prevention Project (BCPP), also known as the “Ya Tsie” study, is a pair-matched, cluster-randomized trial funded by PEPFAR that is designed to test whether a package of combination prevention interventions reduces population-level cumulative 3-year HIV incidence. Another primary objective of the study includes evaluation of population-level uptake of HIV testing and ART at baseline and over time; the baseline cross-sectional results are presented in this manuscript. The trial is being conducted in 30 communities in Botswana (15 pairs matched according to size, pre-existing health services, population age structure, and geographic location, including proximity to urban areas), with a total population of approximately 180,000 persons (Figure 1), representing nearly 10% of Botswana’s estimated population. Fifteen communities were randomized to a combination prevention arm, and 15 to a non-intervention arm. Interventions in the combination prevention arm include home-based and mobile HIV testing and counseling; point-of-care CD4 testing; linkage to care support; expanded ART (for CD4 351–500 cells/mm3 or CD4 >500 with HIV-1 RNA≥10,000 copies/mL, in addition to local criteria); and enhanced male circumcision services. The protocol has been amended to offer universal treatment (regardless of disease stage) in the intervention communities, and the Botswana Ministry of Health (MoH) plans to provide universal ART in 2016 (a change that will also apply to non-intervention communities). ART and other services are provided at or above the evolving local standard of care, throughout the study.

Figure 1.

Map of the 15 matched community pairs participating in the Botswana Combination Prevention Project study, Botswana.

Study population

Survey participants were recruited using a household-based probabilistic sampling strategy at the community level. Within each of the 30 communities, the sampling strategy began with identifying and geocoding every plot with a household-like structure using satellite imagery captured between 2012 and 2015 (Google Earth, Mountain View, California) overlaid with enumeration boundaries used in the 2011 Botswana Census.15 A simple random 20% sample was then selected from the list of geocoded plots. For each household on the selected plots, a household representative (aged 18 years or older) was asked to list each household member with their age, gender, time spent in the household and relationship to the household head. Based on this information, research staff identified potentially eligible household members and invited them to provide written consent to participate, complete a questionnaire and undergo HIV testing. Eligibility criteria included age 16–64 years; spending on average at least three nights per month in the household; documentation of Botswana citizenship or marriage to a Botswana citizen; and ability to provide informed consent. Participants received a BWP20 (approximately USD$2) cellular telephone prepaid voucher as compensation for their time. Plots were visited up to three times to enumerate household members; up to three additional attempts were made to enroll each enumerated household member.

Data collection

The baseline household survey included questions about sociodemographics, health, and HIV risk behavior. Persons who self-reported a positive HIV status and who were able to provide corresponding documentation (e.g. written test result, ART prescription) were not re-tested for HIV. All other participants were offered counseling and rapid HIV testing according to the Botswana-government– approved algorithm including KHB (KHB, Shanghai Kehua Bio-Engineering Co Ltd, China) and Unigold (Trinity Biotech Plc, Ireland) parallel HIV rapid tests. Documentation of ART receipt was sought for all persons who reported that they were currently on ART (e.g. prescriptions; clinical notes indicating ART receipt; or pills). HIV-1 RNA was tested in all HIV-infected persons, regardless of ART status. HIV-1 RNA was performed using the Abbott RealTime HIV-1 assay on the automated m2000 system (Abbott Laboratories, Wiesbaden, Germany) (range 40–10,000,000 copies/mL) in the Botswana–Harvard HIV Reference Laboratory, which participates in Virology Quality Assurance and is accredited to ISO 17025. Point-of-care CD4 count (Pima, Alere Inc., Waltham, Massachusetts) was obtained on HIV-positive persons who were not currently taking ART. CD4 count and HIV-1 RNA results were shared with participants. Research assistants participated in the point-of-care CD4 and HIV testing external quality assurance program and were assessed for competence using blinded testing.

HIV-infected participants not yet on ART were referred to their local clinic for prompt ART initiation if their CD4 count was ≤350 cells/mm3 or if pregnant. HIV-infected participants with a CD4 count >350 cells/mm3 were referred to their local clinic for evaluation for possible ART initiation, and for other services as needed, including evaluation for tuberculosis.

After completion of the baseline survey, community-wide HIV testing and counseling, linkage to care, expanded ART, and expanded male circumcision interventions are started in the combination prevention communities. All participants in the baseline survey will be re-contacted annually for three years, for HIV testing (if previously negative) and for re-interview, with ongoing interventions in the combination prevention arm during this period.

Ethics

The study protocol, informed consent, and other materials are approved by the Botswana Health Research Development Committee (IRB of the Botswana MoH) and the United States CDC IRB. All participants provided written informed consent. Participants aged 16–18 years provided written assent (with parents/guardians providing written permission). The study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01965470).

Statistical analysis

We restricted the present analysis to data collected from the baseline household survey of all 30 study communities, prior to the roll-out of any intervention activities.

The 90–90–90 targets were calculated as follows:

We used modified Poisson generalized estimating equations to obtain prevalence ratios (PR), corresponding Huber robust standard errors and 95% Wald confidence intervals (CI) to examine associations between individual sociodemographic factors and a binary outcome indicating achievement of the three individual and combined overall 90–90–90 targets.16 All analyses were conducted using SAS software version 9·4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

We conducted three additional analyses to assess the extent to which our results might be sensitive to selection bias due to non-participation. First, complete-case inverse-probability weighting was used to re-estimate each 90–90–90 target, adjusting for non-participation by accounting for fully observed potential predictors common to non-participation and the 90–90–90 targets.17,18 Inverse-probability weighting adjusts for non-participation by empirically breaking the association between observed predictors and non-participation, allowing for unbiased estimation in the weighted sample provided a regression for non-participation is correctly specified, and no unobserved correlates of non-participation and outcomes defining the 90–90–90 targets exist. Inverse-probability weights for participation were constructed using the predicted probabilities from a multivariable logistic regression model containing the following fully observed covariates and their two-way interactions: age, gender, relationship to household head, community, and presence of household member during enumeration. We then conducted a weighted, complete-case crude analysis using modified Poisson generalized estimating equations to estimate the marginal probability of each 90–90–90 target.

Although inverse-probability weighting adjusts for observed differences between enrolled and unenrolled enumerated persons found to be eligible, the enumerated population itself may systematically differ from the general population. Therefore, in a second sensitivity analysis, we standardized our observed 90–90–90 estimates to the age and gender distribution of HIV-positive persons in Botswana using the 2011 Botswana Census15 and the 2013 Botswana AIDS Indicator Survey.19

Finally, we performed a third sensitivity analysis which entailed re-estimating the 90–90–90 targets by combining complete-case outcomes observed among enrolled participants with potential outcomes of un-enrolled, eligible household members, assuming a hypothetical scenario in which non-participating residents had substantially lower rates of HIV testing, ART coverage, and virologic suppression. Programming code is available upon request by contacting the corresponding author.

Role of the funding source

The funders played no role in study design; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of this report; or in the decision to submit it for publication. The corresponding author, M. Essex, had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

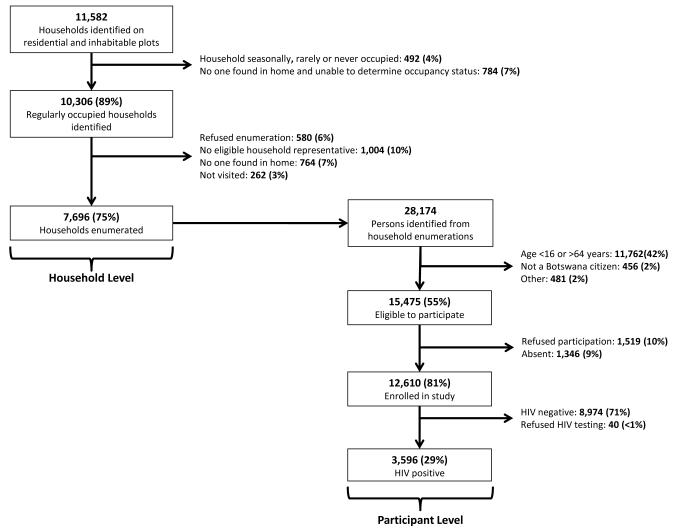

The baseline household survey was conducted in 30 communities from October 2013-November 2015. Research staff visited 13,135 randomly-selected plots identified on satellite imagery and categorized 9,940 (76%) as residential and habitable. On these plots, 11,582 households were identified, 10,306 (89%) were found to be regularly occupied, and 7,696 (75%) were enumerated (Figure 2). Reasons for non-enumeration included absence of an eligible household informant (10%), absence of any persons (7%), and refusal (6%). A total of 28,174 residents were enumerated; 15,475 (55%) were eligible for participation and of these, 12,610 (81%) completed the baseline survey. Among the 15,475 enumerated, eligible household members, 9,286 (60%) were women and 6,189 (40%) were men. Reasons for non-participation among eligible persons included refusal (10%) and absence (9%).

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of recruitment, eligibility and enrollment of participants for the Botswana Combination Prevention Project at the household and participant level.

Of the 12,610 participants, 2,995 (24%) had documentation of prior positive HIV test, 9,575 (76%) underwent HIV testing, and 40 (0·3%) refused testing. Overall, 3,596 participants (including individuals known to be HIV-infected and those newly testing positive for HIV) were HIV infected for an overall HIV prevalence of 29%. HIV-1 RNA testing was completed in 99·7% of HIV-infected participants.

Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of HIV-infected enrollees. Seventy-three percent were female (median age 40 years, IQR 33–48 years). Eighty-seven percent (8,050 of 9,268) of women residing in participating households enrolled, compared to 74% (4,560 of 6,189) of men residing in these households. The majority of participants reported being single and nearly one-half had a primary school education or less. Approximately one-third were employed and 56% reported no monthly income. More than two-thirds of participants spent <1 week outside the community during the previous 12 months.

Table 1.

Summary of baseline characteristics of N=3,596 HIV-infected individuals enrolled in the Botswana Combination Prevention Project from 30 communities in Botswana.

| Characteristic (total n with data) | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender (n=3,596) | |

| Male | 962 (27%) |

| Female | 2,634 (73%) |

|

| |

| Age, in years (n=3,596) | |

| 16 to 19 years | 47 (1%) |

| 20 to 29 years | 460 (13%) |

| 30 to 39 years | 1,222 (34%) |

| 40 to 49 years | 1,069 (30%) |

| 50 to 59 years | 631 (18%) |

| 60 years and older | 167 (5%) |

| Median (Q1, Q3)a | 40 (33, 48) |

|

| |

| Relationship status (n=3,593) | |

| Single or never married | 2,799 (78%) |

| Married | 539 (15%) |

| Widowed, divorced or separated | 255 (7%) |

|

| |

| Education (n=3,572) | |

| Non-formal | 531 (15%) |

| Primary | 1,072 (30%) |

| Junior secondary | 1,412 (40%) |

| Senior secondary | 311 (9%) |

| Higher than senior secondary | 246 (7%) |

|

| |

| Employment status (n=3,594) | |

| Employed | 1,173 (33%) |

| Unemployed and looking for work | 1,766 (49%) |

| Unemployed but not looking for workb | 655 (18%) |

|

| |

| Monthly income (n=3,572)c | |

| None | 1,999 (56%) |

| <$96 per month | 647 (18%) |

| $96 to $477 per month | 795 (22%) |

| >$447 per month | 131 (4%) |

|

| |

| Time spent away from community, past year (n=3,594) | |

| None | 1,838 (51%) |

| Less than 1 week | 736 (20%) |

| 1 to 2 weeks | 303 (8%) |

| 3 to 4 weeks | 325 (9%) |

| 5 to 12 weeks | 296 (8%) |

| More than 12 weeks | 96 (3%) |

25th and 75th percentiles.

Unemployed and not looking for work includes participants reporting housewife, student and retired as the primary reason for unemployment.

Botswana pula (BWP) were converted to US dollars (USD) based on a rate of BWP10·49 per USD$1.

Coverage of 90–90–90 targets

Among the 3,596 HIV-infected persons identified, 2,995 (83·3%; 95% CI: 81·4%, 85·2%) already knew their positive status and provided supporting documentation. A total of 466 participants newly tested HIV-positive and 135 self-reported being HIV-positive but could not provide documentation. Although these individuals were retested and found to be positive, to be conservative, they were not included in the numerator of the first 90–90–90 target.

Among the 2,995 HIV-infected persons who knew their positive status, 2,617 (87·4%; 95% CI: 85·8%, 89·0%) were receiving ART; an additional 26 participants reported taking ART previously, but were not currently on ART. The 2,617 participants currently receiving ART represented 95% of the 2,754 persons eligible for ART per Botswana guidelines.

Finally, 2,517 (96·5%; 95% CI: 96·0%, 97·0%) of the 2,609 participants currently on ART with a viral load measurement had HIV-1 RNA ≤400 copies/mL; 2,428 (93·1%; 95% CI: 92·1%, 94·0%) had HIV-1 RNA ≤40 copies/mL. Among the 2,635 persons who reported ever starting ART for their health (including defaulters) with a viral load measurement, 95·6% (95% CI: 95·0%, 96·3%) had HIV-1 RNA ≤400 copies/mL.

Overall, among all HIV-infected persons, 83·3% (95% CI: 81·4%, 85·2%) knew their status, 72·8% (95% CI: 70·1%, 75·5%) were currently receiving ART, and 70·2% (95% CI: 67·5%, 73·0%) were currently on ART and had virologic suppression (HIV-1 RNA ≤400 copies/mL) (Figure 3). Interestingly, 136 participants reported that they were not currently receiving ART but had an HIV-1 RNA ≤400 copies/mL. To confirm the ART status, we queried the Botswana MoH electronic medical records systems for evidence of recent receipt of ART services. We were able to retrieve records for 96 (71%) of these individuals and 40 (42%) were found to have initiated ART prior to the survey. If we include these 40 additional participants with HIV-1 RNA ≤400 copies/mL, the coverage estimates for diagnosis, treatment and virologic suppression would increase to 83·3%, 88·7% and 96·5%, respectively (and 71·3% would have achieved the overall 90–90–90 target).

Figure 3.

Proportions of HIV-infected individuals enrolled in the Botswana Combination Prevention Project meeting the UNAIDS 90–90–90 targets at baseline.

Sensitivity analyses

Table 2 presents the results of three sensitivity analyses undertaken to examine the potential impact of selection bias due to either non-participation among enumerated eligible residents and/or differences between our enumerated sample and Botswana’s general population. Adjustment by inverse probability weighting and standardization resulted in an overall target estimate of 69·8% (95% CI: 67·1%, 72·6%) and 63·4% (95% CI: 61·6%, 65·1%), respectively (Table 2). Finally, when we assumed that HIV prevalence was 50% higher and knowledge of HIV status, ART coverage and virologic suppression were each 25% lower in non-participants than what was observed among enrolled participants, the overall target estimate was 63·8%.

Table 2.

Summary of sensitivity analyses conducted to assess the potential impact of non-participation on the observed estimates of achievement of 90–90–90 targets.

| Proportion (95% Confidence Interval) | Hypothetical assumptions

for unenrolled, eligible household members compared to enrolled participantsa |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | Inverse probability weighting to adjust for non-participation by unenrolled, eligible household membersb |

Direct standardization of observed estimates to Botswana Census age and gender distribution |

HIV prevalence: 50%

higher Knowledge of status: 25% lower ART coverage: 25% lower Viral suppression: 25% lower |

|

|

First 90: Knowledge of HIV

status (among HIV-positive persons) |

83·1% (81·4%, 85·2%) |

82·8% (80·9%, 84·7%) |

77·8% (76·2%, 79·4%) |

77·8% |

|

| ||||

|

Second 90: Currently receiving

ART (among HIV-positive persons who know their status) |

87·4% (85·8%, 89·0%) |

87·4% (85·8%, 89·1%) |

85·0% (83·3%, 86·8%) |

83·0% |

|

| ||||

|

Third 90: Virologically

suppressedc,d (among HIV-positive persons who know their status and currently receiving ART) |

96·5% (96·0%, 97·0%) |

96·5% (96·0%, 97·0%) |

93·8% (92·4%, 95·3%) |

92·6% |

|

| ||||

|

Overall: Knows HIV status, on

ART and virologically suppressed (among HIV-positive persons) |

70·2% (67·5%, 73·0%) |

69·8% (67·1%, 72·6%) |

63·4% (61·6%, 65·1%) |

63·8% |

Abbreviations: Antiretroviral therapy, ART.

HIV prevalence among unenrolled, eligible persons set to 42·8%. Proportion of assumed HIV-positive unenrolled, eligible persons who know their status set to 62·3%. ART coverage among assumed HIV-positive unenrolled, eligible persons who know their status set to 65·6%. Viral suppression among assumed HIV-positive unenrolled, eligible person who know their status and on ART set to 72·4%.

Estimated from weighted modified Poisson generalized estimating equations model with weights constructed to adjust for non-participation with the following fully observed covariates: age, gender, relationship to head of household, community, and whether the household member was present at the time of enumeration.

Virologically suppressed defined as HIV viral load ≤400 copies/ml.

HIV viral load not available for N=8 participants currently on ART and N=2 ART-naïve participants due to missing specimens.

Predictors of achieving 90–90–90 targets

Table 3 presents the univariable associations between baseline characteristics and achievement of each individual and overall 90–90–90 target. Male gender, younger age, being single or never married, increased time spent outside the community, and higher levels of education were significantly associated with lower levels of coverage for the overall target. For example, HIV-infected participants aged <30 years were nearly one-half as likely to know their status, be on ART and achieve viral suppression compared to those aged ≥60 years. Similarly, spending >12 weeks outside the community and having higher than senior secondary education were each associated with an approximate 20% decreased likelihood of meeting the overall target (Table 3).

Table 3.

Univariable prevalence ratios (PR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the association between baseline sociodemographic characteristics and achievement of the UNAIDS 90–90–90 goals individually and overall.

| First 90: Knowledge of HIV status (among HIV-positive persons) |

Second 90: Currently receiving ART (among HIV-positive persons who know their status) |

Third 90: Virologically suppresseda,b (among HIV-positive persons who know their status and currently receiving ART) |

Overall: Knows HIV status, on ART and virologically suppressed (among HIV-positive persons) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| PR (95% CI) | PR (95% CI) | PR (95% CI) | PR (95% CI) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 0·90 (0·87, 0·94) | 1·04 (1·01, 1·07) | 0·99 (0·97, 1·01) | 0·92 (0·87, 0·98) |

| Female | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

|

| ||||

| Age | ||||

| 16 to 19 years | 0·74 (0·60, 0·92) | 0·80 (0·66, 0·97) | 0·70 (0·56, 0·87) | 0·41 (0·29, 0·59) |

| 20 to 29 years | 0·74 (0·68, 0·81) | 0·79 (0·73, 0·86) | 0·91 (0·88, 0·94) | 0·53 (0·47, 0·60) |

| 30 to 39 years | 0·92 (0·87, 0·98) | 0·93 (0·88, 0·99) | 0·96 (0·95, 0·97) | 0·82 (0·75, 0·91) |

| 40 to 49 years | 1·00 (0·95, 1·06) | 0·97 (0·92, 1·02) | 0·97 (0·96, 0·99) | 0·94 (0·86, 1·03) |

| 50 to 59 years | 1·01 (0·96, 1·06) | 1·00 (0·94, 1·07) | 0·99 (0·98, 1·00) | 1·00 (0·92, 1·09) |

| ≥60 years | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

|

| ||||

| Relationship status | ||||

| Married | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Single or never married | 0·92 (0·89, 0·95) | 0·93 (0·89, 0·96) | 0·97 (0·95, 0·98) | 0·83 (0·78, 0·87) |

| Widowed, divorced or separated | 1·01 (0·97, 1·06) | 1·00 (0·95, 1·05) | 1·00 (0·98, 1·02) | 1·01 (0·93, 1·10) |

|

| ||||

| Time spent away from community past 12 months |

||||

| None | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Less than 1 week | 0·96 (0·93, 0·99) | 0·97 (0·94, 1·00) | 0·99 (0·97, 1·01) | 0·92 (0·87, 0·97) |

| 1 to 2 weeks | 0·98 (0·92, 1·03) | 0·94 (0·89, 1·00) | 0·99 (0·96, 1·02) | 0·91 (0·84, 0·97) |

| 3 to 4 weeks | 0·94 (0·90, 0·99) | 0·99 (0·95, 1·03) | 0·99 (0·97, 1·02) | 0·93 (0·86, 1·00) |

| 5 to 12 weeks | 0·95 (0·88, 1·02) | 0·98 (0·92, 1·04) | 0·97 (0·93, 1·00) | 0·90 (0·81, 0·99) |

| More than 12 weeks | 0·83 (0·71, 0·97) | 0·98 (0·88, 1·09) | 0·96 (0·90, 1·03) | 0·78 (0·64, 0·95) |

|

| ||||

| Education | ||||

| Non-formal | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Primary | 0·99 (0·95, 1·03) | 0·96 (0·93, 1·00) | 1·00 (0·99, 1·01) | 0·95 (0·90, 1·01) |

| Junior secondary | 0·95 (0·92, 0·98) | 0·93 (0·90, 0·96) | 0·97 (0·96, 0·99) | 0·86 (0·81, 0·91) |

| Senior secondary | 0·83 (0·76, 0·90) | 0·91 (0·85, 0·97) | 0·94 (0·90, 0·99) | 0·71 (0·63, 0·79) |

| Higher than senior secondary | 0·88 (0·83, 0·94) | 0·95 (0·90, 1·00) | 0·97 (0·94, 1·00) | 0·81 (0·73, 0·89) |

|

| ||||

| Employment status | ||||

| Employed | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Unemployed, looking for work | 1·05 (1·01, 1·09) | 0·99 (0·96, 1·01) | 1·00 (0·98, 1·01) | 1·03 (0·96, 1·09) |

| Unemployed, not looking for workb | 1·04 (1·00, 1·08) | 1·03 (0·99, 1·06) | 0·99 (0·97, 1·01) | 1·06 (1·00, 1·12) |

|

| ||||

| Monthly incomec | ||||

| None | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| <$96 per month | 0·99 (0·96, 1·02) | 1·00 (0·96, 1·03) | 1·00 (0·98, 1·02) | 0·99 (0·93, 1·05) |

| $96 to $477 per month | 0·96 (0·93, 0·99) | 1·02 (0·99, 1·06) | 1·01 (1·00, 1·03) | 1·00 (0·94, 1·05) |

| >$447 per month | 0·90 (0·83, 0·97) | 1·06 (0·99, 1·13) | 0·94 (0·88, 1·01) | 0·88 (0·75, 1·03) |

Abbreviations: Antiretroviral therapy, ART; Prevalence ratio, PR; Confidence interval, CI.

Virologically suppressed defined as HIV viral load ≤400 copies/ml.

HIV viral load not available for N=10 participants.

Unemployed and not looking for work includes participants reporting housewife, student and retired as the primary reason for unemployment.

Botswana pula (BWP) were converted to US dollars (USD) based on a rate of BWP10·49 per USD$1.

Discussion

We found very high levels of diagnosis, treatment and viral suppression among HIV-infected individuals in our study population: 83·3% of HIV-infected persons knew their positive status, 87·4% of these individuals were receiving ART, and 96·5% of persons receiving ART had virologic suppression. Overall, 70·2% of all HIV-infected persons had virologic suppression, compared with the UNAIDS goal of 73%. Younger age was the strongest predictor of being undiagnosed, not on ART and not virologically suppressed in our population, followed by more time spent outside the community (>12 weeks/year). Women were more likely to know their positive HIV status than men, potentially due to near universal testing of pregnant women in Botswana.20

Very few countries, including those in North America and Europe, have achieved similarly high coverage levels. In recent national-level analysis of HIV treatment cascades by Levi et al, no country met the overall UNAIDS goal of 73% virologic suppression among persons living with HIV.21 It may be informative for countries and programs to evaluate their success in reaching the 90–90–90 targets, even if they have not yet moved to universal testing and treatment.

Several factors likely contribute to Botswana's successful HIV treatment program. Botswana was among the first high-HIV-burden countries to make prevention of mother-to-child transmission services (starting in 2000) and ART (starting in 2002 with expansion nationwide by 2006) available to citizens for free. There has been a strong political will to speak openly about HIV in public forums and destigmatize HIV testing. In 2004, former Botswana President Festus Mogae introduced routine “opt-out” HIV testing and counseling in healthcare settings. According to UNAIDS, the lack of widely available testing may constitute the major impediment to achieving high ART coverage, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa.1 With a widely dispersed population, Botswana prioritized early decentralization of HIV treatment: ART is available from more than 600 clinics nationwide alongside other health services. Distance to services is correlated with retention in care22 and an estimated 95% of the Botswana population resides within 10km of an ART-dispensing facility. Furthermore, the program has included virologic monitoring for patients on ART since inception, enabling adherence assessment and interventions. Many of these approaches could be adopted by other countries/programs.

High rates of treatment coverage and virologic suppression should help reduce HIV incidence. However, the most recent estimate of annual adjusted HIV incidence in Botswana (1·35% in 2013) indicates substantial ongoing transmission.19 This is presumably due to ongoing transmission from the 30% of HIV-infected persons who remain untreated in this setting of high HIV prevalence; furthermore, these data (and the 90–90–90 targets) do not capture the complexities of sexual networks, risk behavior patterns, and biologic factors that also contribute to ongoing HIV transmission. Nevertheless, in totality, evidence from this and other studies suggests that universal ART (regardless of CD4 count), as recently recommended by the World Health Organization,23 will be important in decreasing new infections.

The main strength of this analysis is that it draws upon a large population-based random sample of household residents from 30 geographically and ethnically diverse communities across Botswana. Routinely collected programmatic data cannot provide the actual number of persons living with HIV. Rather, this figure is usually estimated indirectly from population distributions and HIV prevalence figures. Similarly, programmatic data generally cannot directly estimate the numbers of HIV-infected individuals who have been diagnosed with HIV. We were able to collect data on both of these indicators, and to test for virologic suppression in >99% of HIV-infected participants; viral load information is infrequently available in resource-constrained settings.

Our study is subject to several limitations. First, approximately 25% of potentially inhabited households were not enumerated, and nearly 20% of age- and residency-eligible members of enumerated households were not enrolled. Botswana has a highly mobile population, and the most common reasons for non-participation were absenteeism and refusal. It is possible that persons not found in the household may differ from enrolled participants with respect to diagnosis, treatment and virologic suppression as defined by the 90–90–90 targets. For example, nearly three quarters of our participants were female compared to 60% of household residents. A weighted sensitivity analysis accounting for differences between enumerated, unenrolled eligible household members and enrolled participants did not substantially change our findings. Additionally, our estimates were derived from smaller rural/peri-urban communities. It is not possible to know whether individuals residing in other areas (including urban settings) would have similar HIV testing, treatment and adherence rates. However, given earlier and more widespread availability of HIV testing and treatment facilities, we anticipate coverage to be higher in urban areas. Furthermore, according to Botswana national treatment and UNAIDS14 statistics, approximately 270,000 (~70%) of people believed to be living with HIV in Botswana are on ART, which is similar to the 72·8% estimate in our study population. According to the 2013 Botswana AIDS Indicator Survey, the estimated HIV prevalence was slightly lower in rural/peri-urban villages such as those taking part in BCPP (17·4%-18·7%) compared with prevalence in cities or towns (19·5%-21·6%); HIV prevalence varies more dramatically by region (11·1%-27·5%).19 A sensitivity analysis that standardized estimates of 90–90–90 targets to Botswana’s national HIV-infected population did not substantially alter our findings. The overall target estimate after standardization was 63·4% (95% CI: 61·6%, 65·1%), compared with our observed estimate of 70·2% (95% CI: 67·5%, 73·0%). Lastly, our eligibility criteria excluded several key populations, including adolescents and children less than 16 years old, adults 65 years and older, and non-citizens. Given our home-based recruitment approach (which may reach somewhat different populations compared with those reached by other HIV testing strategies),24 our study also did not attempt to enroll other key populations such as commercial sex workers. We estimate that approximately 2% of enumerated residents were not Botswana citizens. This may be important, because non-citizens are ineligible to receive ART free of charge in the country.

Despite these limitations, our data represent among the most complete, population-level estimates available from the region, and indicate very high rates of coverage related to HIV testing, ART initiation, and virologic suppression. It is particularly remarkable that Botswana has achieved such high rates of ART coverage and virologic suppression given that the national CD4 threshold for ART eligibility has been ≤350 cells/mm3; this could indicate a more “mature” epidemic, and may differ in other settings. We found that 95% of HIV-infected persons eligible for ART by current guidelines are already on ART. These findings suggest that Botswana should reach and exceed the UNAIDS 90–90–90 targets sooner than 2020, if treatment eligibility changes to include ART to all persons living with HIV irrespective of their CD4 count, assuming the health system is able to test and treat those not yet on ART, and that persons starting ART with higher CD4 count will exhibit reasonably high levels of adherence.

Although Botswana is a middle-income country with a total population of approximately 2 million, it has suffered from a very significant burden of HIV disease. The high rates of HIV testing, ART, and virologic suppression in Botswana provide good evidence that the UNAIDS targets are achievable elsewhere.

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

In light of accumulating evidence that providing antiretroviral treatment to all people living with HIV (regardless of disease stage) optimizes their health and will help end the global HIV epidemic, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) has proposed new HIV testing and treatment targets: that 90% of all people living with HIV will know their HIV status, 90% of all people with diagnosed HIV infection will be on antiretroviral treatment, and 90% of all people receiving treatment will have virologic suppression by 2020. However, considerable uncertainty remains as to whether these ambitious UNAIDS targets are achievable, especially in resource-constrained settings where the burden of HIV is the largest. The vast majority of publicly available figures (in PubMed, UNAIDS reports, and meetings proceedings) that describe global progress toward achieving these targets are derived indirectly using model-based estimates of the relevant numerators and denominators rather than directly measured data. Moreover, estimates of virologic suppression among HIV-positive persons receiving treatment are largely restricted to Western nations; only limited data on this key component of the HIV treatment cascade are available from high-HIV-burden, resource-constrained settings. (Databases searched: PubMed; UNAIDS, WHO, and US CDC websites; Google search engine (for conference proceedings); search terms used: “HIV testing coverage,” “antiretroviral treatment coverage,” “national antiretroviral treatment”; date of search: 22 February 2016.)

Added value of this study

Botswana is a middle-income country in sub-Saharan Africa with a very high prevalence of HIV (25.2% among persons 15–49 years) and a national treatment program that offers antiretrovirals to HIV-infected adults with CD4 count of 350 cells/mm3 or below. We directly measured population-level coverage of HIV testing, antiretroviral treatment, and virologic suppression (the three UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets) in the context of a cluster-randomized HIV combination prevention study that is underway in 30 communities across Botswana. A pre-intervention survey was administered to more than 12,000 adult residents recruited from a 20% simple random sample of all households in the communities. We found one of the highest overall coverage levels of the UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets that has been described to date globally—a level that nearly achieves the overall UNAIDS target.

Implications of all the available evidence

Our findings provide current evidence that the UNAIDS targets, while ambitious, are achievable even in resource-constrained settings with high HIV burden.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by The United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) under the terms of cooperative agreement U01 GH000447. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of CDC.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests

VDG reports personal fees from Gilead Sciences for service on Data Monitoring Committees, outside the submitted work. SDP reports royalties from UpToDate, Inc, for an article on ART in LMICs. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Author Contributions

TG, KEW, MPH, ME, and SL prepared the first draft; KEW, MPH, SM, EK, VN, EvW, KMP, HB, SDP, LAM, TM, and ETT reviewed the manuscript and provided comments; KEW, MPH, ME, and SL finalized the report based on feedback from other authors; TG, SM, UC, EK, QL, MM, LO, EvW, KMP, NK, KB, HB, RW, and ETT collected or prepared the data; KEW, QL, RW, ETT, and VDG analyzed and interpreted the data; TG, MPH, JM, MM, LO, KMP, SDP, RL, SeH, ETT, VDG, ME, and SL helped provide overall guidance to the conduct of the study; and JM, MM, VN, ETT, VDG, ME, and SL were involved in the origination and development of the concept of the study.

References

- 1.UNAIDS . 90-90-90: An ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS); Geneva, Switzerland: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Danel C, Moh R, Gabillard D, et al. A trial of early antiretrovirals and isoniazid preventive therapy in Africa. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:808–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lundgren JD, Babiker AG, Gordin F, et al. Initiation of antiretroviral therapy in early asymptomatic HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:795–807. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donnell D, Baeten JM, Kiarie J, et al. Heterosexual HIV-1 transmission after initiation of antiretroviral therapy: a prospective cohort analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:2092–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60705-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanser F, Barnighausen T, Grapsa E, Zaidi J, Newell ML. High coverage of ART associated with decline in risk of HIV acquisition in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Science. 2013;339:966–71. doi: 10.1126/science.1228160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shapiro RL, Hughes MD, Ogwu A, et al. Antiretroviral regimens in pregnancy and breast-feeding in Botswana. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2282–94. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Townsend CL, Byrne L, Cortina-Borja M, et al. Earlier initiation of ART and further decline in mother-to-child HIV transmission rates, 2000-2011. AIDS. 2014;28:1049–57. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.UNAIDS . The gap report. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS); Geneva, Switzerland: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kohler P, Schmidt AJ, Cavassini M, et al. The HIV care cascade in Switzerland: reaching the UNAIDS/WHO targets for patients diagnosed with HIV. AIDS. 2015;29:2509–15. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Kirby Institute . HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmissible infections in Australia: annual surveillance report, 2014. The Kirby Institute for Infection and Immunity in Society; Sydney, Australia: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bradley H, Hall HI, Wolitski RJ, et al. Vital signs: HIV diagnosis, care, and treatment among persons living with HIV--United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:1113–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pokrovskaya A, Popova A, Ladnaya N, Yurin O. The cascade of HIV care in Russia, 2011-2013. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17:19506. doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.4.19506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.UNAIDS . Botswana: HIV and AIDS estimates (2014) Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS); Geneva, Switzerland: [accessed 18 Dec 2015]. http://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/botswana. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Botswana Central Statistics Office . Botswana 2011 population and housing census. Botswana Central Statistics Office; Gaborone, Botswana: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yelland LN, Salter AB, Ryan P. Performance of the modified Poisson regression approach for estimating relative risks from clustered prospective data. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174:984–92. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horvitz DT,DJ. A generalization of sampling without replacement from a finite universe. J Am Stat Assoc. 1952;41:663–85. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robins JR,A, Zhao LP. Estimation of regression coefficients when some regressors are not always observed. J Am Stat Assoc. 1994;89:846–66. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Statistics Botswana . Botswana AIDS impact survey (BAIS) IV. Statistics Botswana; Gaborone, Botswana: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dryden-Peterson S, Lockman S, Zash R, et al. Initial programmatic implementation of WHO option B in Botswana associated with increased projected MTCT. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;68:245–9. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levi JRA, Pozniak A, Vernazza P, Kohler P, Hill A. Can the UNAIDS 90-90-90 target be achieved? Analysis of 12 national level HIV treatment cascades. 8th IAS Conference on HIV Pathogenesis, Treatment and Prevention; Vancouver, Canada. 2015; Abstract no. MOAD0102. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siedner MJ, Lankowski A, Tsai AC, et al. GPS-measured distance to clinic, but not self-reported transportation factors, are associated with missed HIV clinic visits in rural Uganda. AIDS. 2013;27:1503–8. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835fd873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.WHO . Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection: what's new. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: Nov, 2015. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharma M, Ying R, Tarr G, Barnabas R. Systematic review and meta-analysis of community and facility-based HIV testing to address linkage to care gaps in sub-Saharan Africa. Nature. 2015;528:S77–85. doi: 10.1038/nature16044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]