Abstract

Background:

Cathepsin L (CatL) is a cysteine protease with strong matrix degradation activity that contributes to photoaging. Mannose phosphate-independent sorting pathways mediate ultraviolet A (UVA)-induced alternate trafficking of CatL. Little is known about signaling pathways involved in the regulation of UVA-induced CatL expression and activity. This study aims to investigate whether a single UVA irradiation affects CatL expression and activity and whether mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/activator protein-1 (AP-1) pathway is involved in the regulation of UVA-induced CatL expression and activity in human dermal fibroblasts (HDFs).

Methods:

Primary HDFs were exposed to UVA. Cell proliferation was determined by a cell counting kit. UVA-induced CatL production and activity were studied with quantitative real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), Western blotting, and fluorimetric assay in cell lysates collected on three consecutive days after irradiation. Time courses of UVA-activated JNK and p38MAPK signaling were examined by Western blotting. Effects of MAPK inhibitors and knockdown of Jun and Fos on UVA-induced CatL expression and activity were investigated by RT-PCR, Western blotting, and fluorimetric assay. Data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance.

Results:

UVA significantly increased CatL gene expression, protein abundance, and enzymatic activity for three consecutive days after irradiation (F = 83.11, 56.14, and 71.19, respectively; all P < 0.05). Further investigation demonstrated phosphorylation of JNK and p38MAPK activated by UVA. Importantly, inactivation of JNK pathway significantly decreased UVA-induced CatL expression and activity, which were not affected by p38MAPK inhibition. Moreover, knockdown of Jun and Fos significantly attenuated basal and UVA-induced CatL expression and activity.

Conclusions:

UVA enhances CatL production and activity in HDFs, probably by activating JNK and downstreaming AP-1. These findings provide a new possible molecular approach for antiphotoaging therapy.

Keywords: Cathepsin L, JNK Pathway, Photoaging, Ultraviolet A

Introduction

Photoaging is characterized by structural changes in dermal extracellular matrix, including solar elastosis and collagen degradation.[1] Proteases capable of degrading extracellular matrix participate in photoaging. Four classes of such proteases are found in mammalian cells: Metalloproteases, aspartic, serine, and cysteine proteases. Metalloproteases and cysteine proteases are believed to be particularly important in extracellular matrix turnover.[2] Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), commonly studied enzymes related to photoaging, degrade most of the dermal extracellular matrices. Their expression and activity are increased by ultraviolet (UV) radiation, resulting in reduced Type I collagen.[3] However, MMPs are secreted extracellularly and work at neutral pH,[4] while cysteine proteases degrade matrix proteins in lysosomes or extracellularly under acidic conditions.[5] UV increases the production and release of inflammatory factors, leading to local inflammation.[6] Inflammation tends to cause local changes in pH that may result in acidic environments. Local acidic environments may increase the activity of cathepsins (Cats) rather than that of MMPs. Moreover, cysteine proteases can activate MMPs.[7] Therefore, the role of cysteine proteases in photoaging has been investigated recently.[8]

CatL is a cysteine protease abundant in fibroblasts, which is involved in skin structure and functions, including hair follicle morphogenesis, epidermal differentiation, wound healing, and antigen presentation.[9,10] The balanced expression of CatL and its inhibitor hurpin is of great importance for normal skin function in mice.[11] Further, CatL is a prominent protease involved in photoaging because of its potent matrix degrading and protease-activating abilities.[12] Recent research shows that CatL activity in fibroblasts is significantly suppressed 1 h after four consecutive daily exposures to 9.9 J/cm2 UVA, whereas its gene expression level remains unchanged.[13] However, repetitive UVA irradiation elevates CatL protein synthesis through increased transcript levels in fibroblasts.[12] Little is known about the molecular mechanisms, whereby UVA induces CatL expression and activity.

Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway regulates CatL expression in several cultured cell types.[14,15,16] In human gingival fibroblasts, interleukin (IL)-6/sIL-6R enhances CatL expression through the caveolin-1-mediated activator protein-1 (AP-1) pathway.[15] In articular chondrocytes, CatL is enhanced by the N-terminal telopeptide of collagen Type II through the activation of p38MAP kinase.[16] Since UVA activates MAPK/AP-1 pathway,[1] we examined whether MAPK/AP-1 pathway regulates UVA-induced CatL expression and activity in human dermal fibroblasts (HDFs).

Here, we evaluated CatL expression and activity following a single UVA irradiation in HDFs. Pharmacologic inhibitors and Jun and Fos knockdown were utilized to determine the role of MAPK/AP-1 pathway in mediating UVA-induced CatL expression and activity.

Methods

Ethics statement

Parents signed an informed consent form on behalf of their enrolled children. The parents were informed of our research objectives and their privacy and anonymity were protected. The consent procedure was conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki. Both the consent procedure and our study were approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou, China (No: [2010]2-22).

Cell culture

HDFs were isolated from circumcised foreskins of children aged 5–9 years. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's media (DMEM, Gibco, USA) supplemented with penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, USA).

Ultraviolet A irradiation and cell counting kit-8 assay

Cells were seeded in dishes and incubated overnight at 37°C prior to UVA exposure. Dishes with cells were placed under the irradiation device (SS-03A, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) at a distance of 365 mm from the UVA source. The UVA source was TL10RS lamps (Philips, Netherlands), with an emission spectrum between 320 and 400 nm. Before each irradiation, cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). PBS was discarded and fresh culture medium was added after irradiation. Mock-irradiated control cells in PBS were covered with foil and incubated inside a clean bench.

Cell viability was determined using a cell counting kit (CCK-8, Dojindo, Japan). In brief, cells were incubated in 96-well culture plates overnight and then treated with UVA irradiation, chemical inhibitors, or small interfering RNA (siRNA). After treatment, 10 μl CCK-8 solution was added. Cells were incubated at 37°C for 4 h. Absorbance was analyzed at 450 nm using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay reader (Bio-Rad, USA).

Mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitor treatment

SP600125 and SB203580 (Calbiochem, USA) were chosen to block the activation of JNK and p38, respectively.[17] The inhibitors were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide to make 10 mmol/L stock solutions. Working concentrations of 800 nmol/L SP600125 and 10 μmol/L SB203580 were chosen as described previously.[1] Cells were pretreated with inhibitors for 1 h before UVA irradiation and incubated with inhibitors again after irradiation until harvesting.

Jun and Fos siRNA transient transfection

Conditions for the efficient transfection were optimized in preliminary experiments. Fibroblasts at 50–70% confluence were transfected with either 100 nmol/L nontargeting siRNA (Sigma-Aldrich) or 50 nmol/L Jun siRNA (SASI_HsO2_00333461, sense strand 5’-GAUGGAAACGACCUUCUAUdTdT-3’, anti-sense strand 5’-AUAGAAGGUCGUUUCCAUC dTdT-3’, Sigma-Aldrich) and 50 nmol/L Fos siRNA (SASI_HsO1_00115496, sense strand 5’-CACACAUGAUGUUUGACGAdTdT-3’, anti-sense strand 5’-UCGUCAAACAUCAUGUGUGdTdT-3’, Sigma-Aldrich) in serum-free Opti-MEM medium (Gibco, USA) using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX transfection reagent (Invitrogen, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The efficiencies of Jun and Fos gene silencing were determined by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and Western blotting analysis 24 h after transfection. Cells were then irradiated with 10 J/cm2 UVA or mock treated before being transferred into fresh culture medium.

Quantitative real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was extracted using Trizol (Invitrogen, Germany) and quantified spectrophotometrically. Sequences of primers (Takara Bio Inc., China) for the amplification of each gene were as follows: CTSL, 5’-GCATGGGTGGCTACGTAAAG-3’ (forward) and 5’-TCCCCAGTCAAGTCCTTCCT-3’ (reverse) with a product size of 120 bp; Jun, 5’-GAAGTGTCCGAGAACTAAAG-3’ (forward) and 5’-AAAAGTCCAACGTTCCGTTC-3’ (reverse) with a product size of 189 bp; Fos, 5’-TCTCCAGTGCCAACTTCATT-3’ (forward) and 5’-GTGTATCAGTCAGCTCCCTC-3’ (reverse) with a product size of 330 bp; and GAPDH, 5’-GCACCGTCAAGGCTGAGAAC-3’ (forward) and 5’-TGGTGAAGACGCCAGTGGA-3’ (reverse) with a product size of 138 bp. One microgram of RNA was subjected to first-strand cDNA synthesis using a PrimeScript RT reagent kit (Takara Bio Inc.) at 37°C for 15 min and 85°C for 5 s. Real-time PCR amplifications were performed on an ABI PRISM 7500 Sequence Detection System with SYBR Premix Ex Taq™ (Takara Bio Inc.). The PCR program was as follows: 95°C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 s and 60°C for 20 s. Relative expression levels of target genes were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method and determined as the fold increase over the expression in controls.[1]

Immunoblotting analysis

Cells were harvested and total protein concentrations were measured by a BCA protein assay kit (Key-Gen Biotech, China). After heat denaturation, the samples were electrophoresed and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% skim milk in tris-buffered saline with Tween for 1 h at room temperature and then incubated with primary antihuman antibodies such as phospho-JNK (P-JNK), JNK, phospho-p38 (P-p38), p38 and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (Cell Signaling Technology, USA), and CatL antibody (Abcam, USA). After washing, the membrane was incubated with secondary antibody (Cell Signaling Technology) for 1 h at room temperature. Blots were detected by chemiluminescence (Millipore, USA). Band intensity was quantified with Quantity One software (Bio-Rad). All values were normalized to the corresponding GAPDH results.

Cathepsin L enzymatic activity measurement

CatL activity was measured using fluorimetric CatL activity assay kit (BioVision, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were lysed in lysis buffer. Cell lysate (50 μl) was incubated with 50 μl reaction buffer containing 1 μmol/L Ca074 (a CatB enzymatic activity-specific inhibitor, Calbiochem, USA) for 15 min to irreversibly inhibit CatB.[18] CatL substrate (Ac-Phe-Arg- amino-4-trifluoromethylcoumarin [AFC], 200 μmol/L final concentration) was then added and the mixture was incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Release of free AFC was measured at λex 400 nm and λem 505 nm using a fluorescence plate reader SpectraMax Gemini (Molecular Devices, USA). Fold increases in CatL activity were determined by comparing the relative fluorescence units against the levels of the controls.

Statistical analysis

Results are representative of at least three independent experiments. All values have been expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical significance was determined by one-way analysis of variance, followed by the least significant difference test. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Effect of ultraviolet A, signaling inhibitors, and siRNA on fibroblast viability and morphology

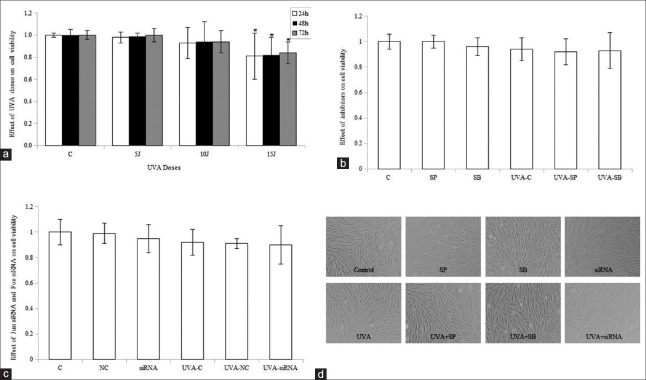

To clarify the effect of UVA, signaling inhibitors, and Jun and Fos siRNA on CatL expression and enzymatic activity, we established an appropriate experimental culture system to exclude their cell cytotoxicity. Cell viability was determined using the CCK-8 assay. First, HDFs were irradiated with sham, 5, 10, and 15 J/cm2 UVA and harvested at 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h after irradiation. Doses of up to 10 J/cm2 UVA did not impair cell viability significantly for 3 days, while 15 J/cm2 UVA remarkably reduced cell viability [Figure 1a]. Therefore, 10 J/cm2 UVA was selected for the study.

Figure 1.

Effect of ultraviolet A, signaling inhibitors, and siRNA on cell viability and morphology. Cellular viability was detected after treatment with ultraviolet A (a), or ultraviolet A and inhibitors (b), or ultraviolet A and siRNA transfection (c), and fibroblasts were photographed (original magnification, ×10) (d). Means ± standard deviations are from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 versus control. UVA: Ultraviolet A; C: Control; SP: SP600125; SB: SB203580; NC: Nontargeting control siRNA; siRNA: Small interfering RNA.

Then, we examined the cytotoxicity of MAPK inhibitors on fibroblasts. Cells were mock irradiated or irradiated with 10 J/cm2 UVA after incubation with 800 mmol/L SP600125 or 10 μmol/L SB203580 for 1 h, and then retreated with or without MAPK inhibitors for 48 h. Viability was measured in control cells (C), SP600125-treated cells (SP), and SB203580-treated cells (SB), without irradiation or with 10 J/cm2 UVA irradiation (UVA-C, UVA-SP, and UVA-SB). We demonstrated that SP600125 and SB203580 neither significantly decreased viability nor altered the morphology of control or UVA-treated cells [Figure 1b and 1d].

Finally, the effect of siRNA on cellular viability was detected. Cells were irradiated with sham or 10 J/cm2 UVA 24 h after transfection with 50 nM Jun siRNA and 50 nmol/L Fos siRNA (siRNA group) or with 100 nmol/L nontargeting control siRNA (NC group) and recultured in fresh complete medium for an additional 48 h. No significant differences in cell viability or morphology were observed between control cells and cells treated with Jun and Fos siRNA, or UVA, or a combination of siRNA and UVA [Figure 1c and 1d].

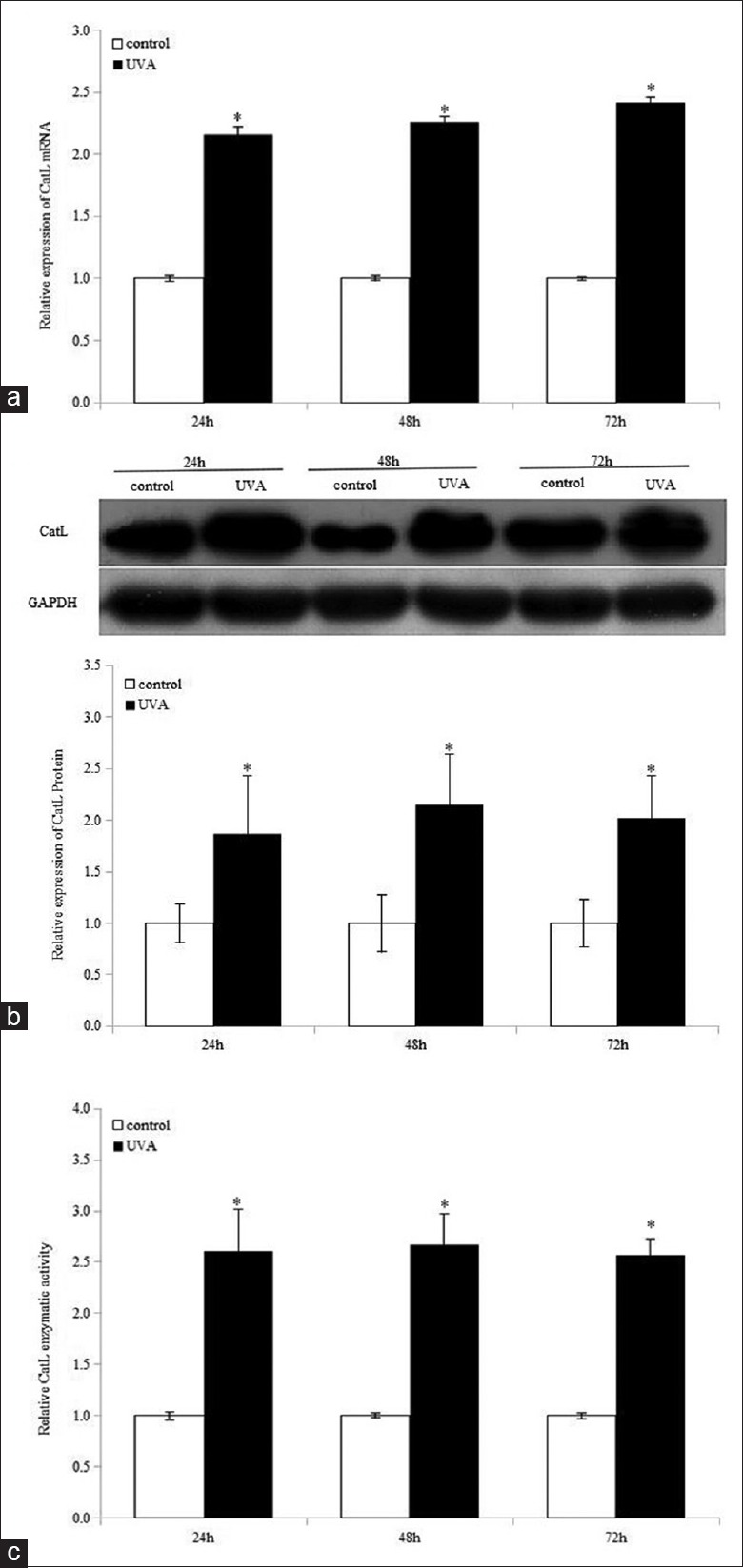

Ultraviolet A enhances cathepsin L expression and enzymatic activity

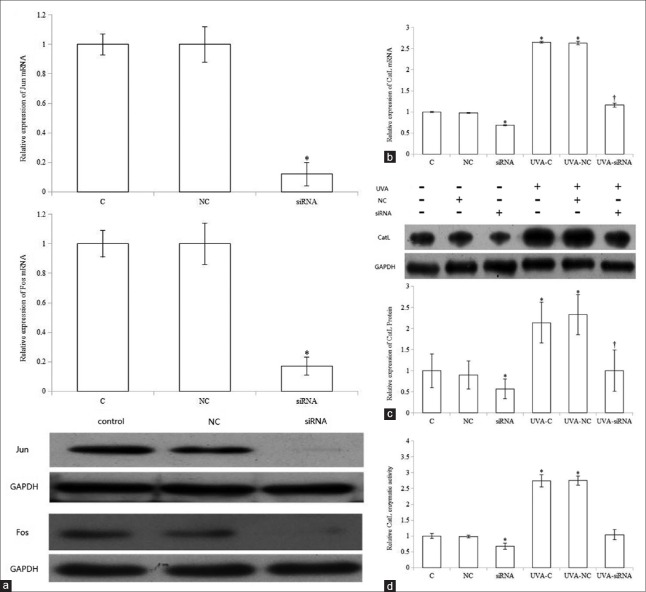

To investigate whether single UVA irradiation affects CatL expression and enzymatic activity, HDFs were exposed to a single dose of UVA. Cell lysates were collected for three consecutive days after UVA exposure. As demonstrated in Figure 2a–2c, UVA irradiation significantly enhanced both CatL expression and activity for three days. There was no significant difference of either CatL expression or activity in UVA-irradiated cells among three days after irradiation.

Figure 2.

Ultraviolet A improves cathepsin L expression and enzymatic activity for three consecutive days in human dermal fibroblasts. Cathepsin L gene expression (a), protein expression (b), and activity (c) were examined after ultraviolet A irradiation. Means ± standard deviations are from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 versus control. UVA: Ultraviolet A; CatL: Cathepsin L; GAPDH: Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

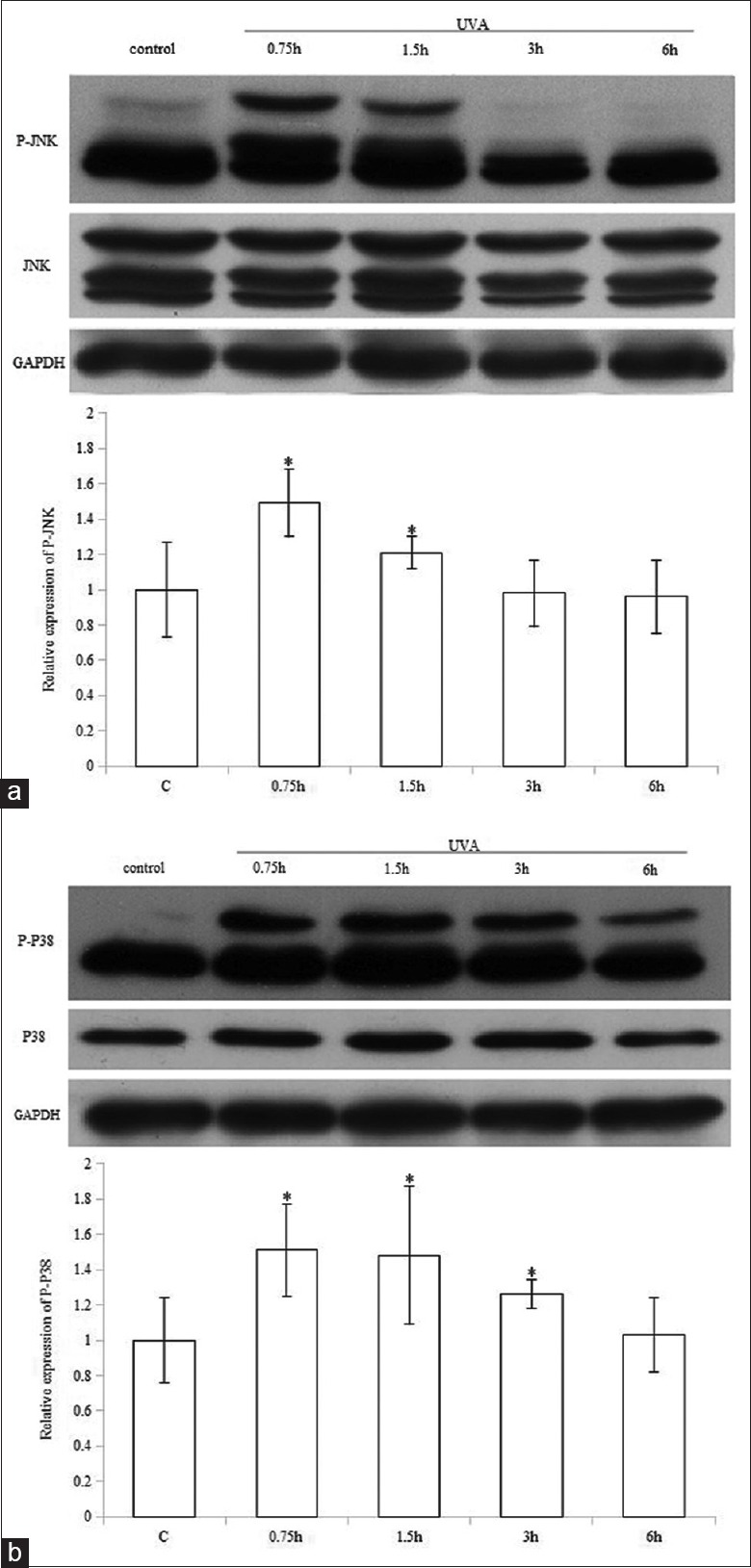

Effect of ultraviolet A on the activation of JNK and p38MAPK pathways

Cells were irradiated with UVA and harvested at 0.75, 1.5, 3, and 6 h after treatment. Phospho-JNK and P-p38 were detected by Western blotting analysis. We demonstrated that JNK phosphorylation was significantly induced between 0.75 and 1.5 h, while P-p38 was remarkably enhanced between 0.75 and 3 h [Figure 3]. Total JNK and p38MAPK levels were unaffected.

Figure 3.

Ultraviolet A activates JNK and p38MAPK pathways. Western blotting analysis was performed to detect the activation of JNK (a) and p38 (b). The representative data of three independent experiments are shown. *P < 0.05 versus control. UVA: Ultraviolet A; P-: Phospho-; GAPDH: Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; MAPK:Mitogen-activated protein kinase.

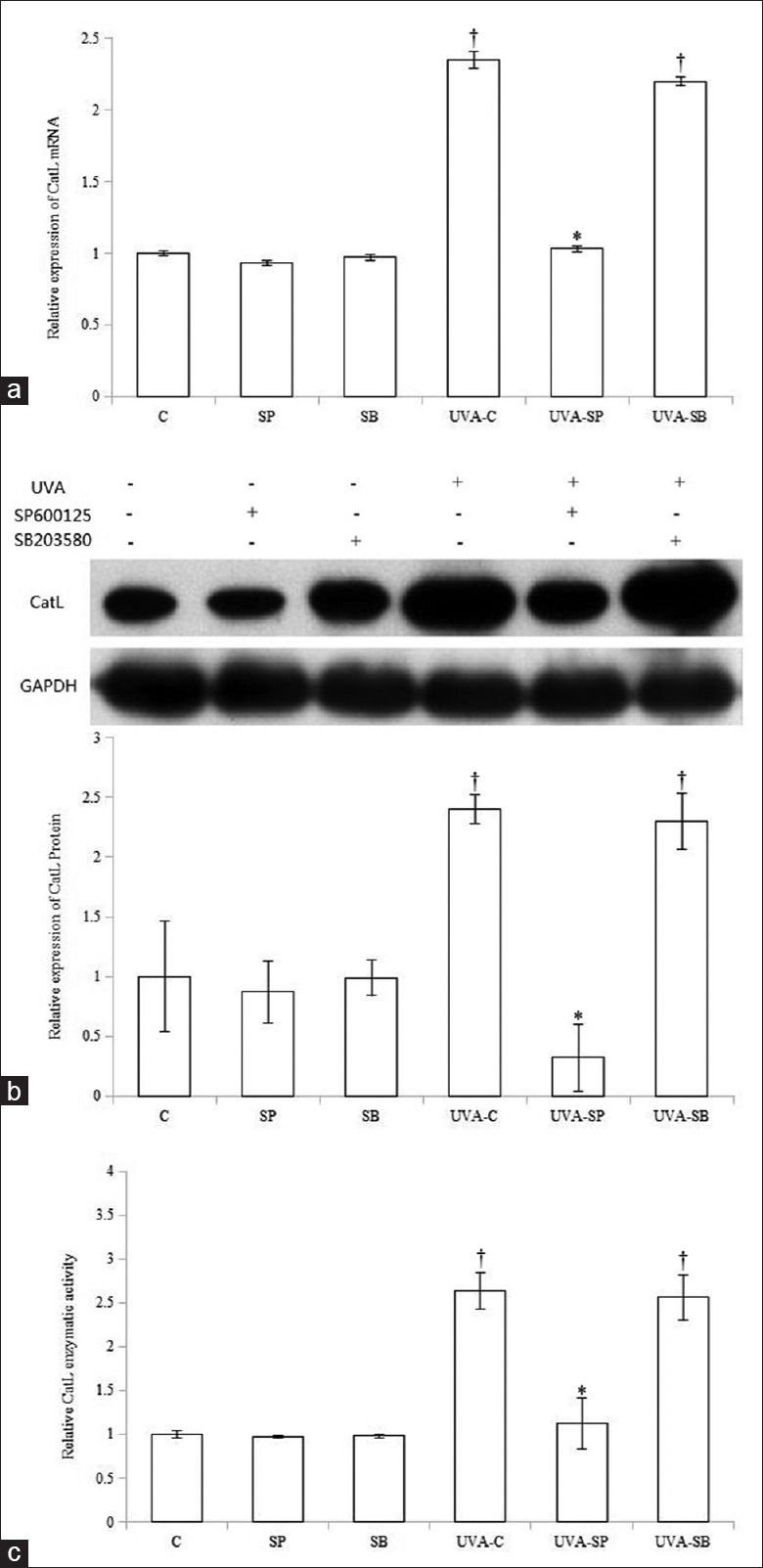

Inhibition of JNK pathway impairs ultraviolet A-induced cathepsin L expression and enzymatic activity

To determine whether MAPKs play roles in UVA-induced CatL expression and enzymatic activity, fibroblasts were pretreated with 800 nmol/L SP600125 (SP) or 10 μmol/L SB203580 (SB) for 1 h before 10 J/cm2 UVA irradiation and retreated with inhibitors after irradiation for 48 h. We previously confirmed that 800 nmol/L SP600125 and 10 μmol/L SB203580 specifically inhibited UVA-stimulated activation of JNK and p38MAPK pathways, respectively.[1] SP600125 treatment significantly attenuated UVA-induced CatL messenger RNA (mRNA) and protein expression compared with UVA-treated controls (UVA-Cs) (P < 0.05) [Figure 4a and 4b]. In contrast, inhibition of p38MAPK pathway did not alter UVA-induced CatL mRNA and protein expression. In addition, basal CatL mRNA and protein expression were not affected by either inhibition of JNK pathway or p38MAPK inactivation.

Figure 4.

Effect of SP600125 and SB203580 on ultraviolet A-induced cathepsin L expression and enzymatic activity. SP600125 decreased ultraviolet A-induced cathepsin L messenger RNA (a), protein (b), and activity (c). All bar graphs represent data as means ± standard deviation (n = 3). *P < 0.05 versus ultraviolet A-treated control or ultraviolet A-SB; †P < 0.05 versus control. UVA: Ultraviolet A; CatL: Cathepsin L; GAPDH: Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; C: Control; SP: SP600125; SB: SB203580.

Finally, we examined the effects of MAPK inhibitors on UVA-induced CatL activity. CatL activity in cells cotreated with SP600125 and UVA was remarkably impaired compared with UVA-C cells (P < 0.05), while p38MAPK inhibition did not significantly suppress UVA-induced CatL activity (P > 0.05) [Figure 4c].

Jun and Fos knockdown reduces ultraviolet A-induced cathepsin L expression and activity

Since AP-1 transactivation is induced by MAPK pathway, we further studied whether UVA-induced CatL expression and activity were also mediated by AP-1. Jun and Fos siRNAs were cotransfected in fibroblasts to decrease AP-1 expression. First, we confirmed that the expression of Jun and Fos in transfected cells was significantly reduced compared with control (P < 0.05). Cells were then exposed to 10 J/cm2 UVA 24 h after transfection and reincubated in fresh medium for 48 h. We observed that cotransfection significantly diminished UVA-stimulated CatL mRNA and protein expression compared with UVA-C (P < 0.05) [Figure 5b and 5c].

Figure 5.

Effect of siRNA-mediated knockdown of activator protein-1 on ultraviolet A-induced cathepsin L expression and enzymatic activity. siRNA transfection knocked down activator protein-1 expression (a), which reduced ultraviolet A-induced cathepsin L messenger RNA (b), protein (c), and activity (d). Data are from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 versus control; †P < 0.05 versus ultraviolet A-treated control or ultraviolet A-nontargeting control. UVA: Ultraviolet A; CatL:Cathepsin L; GAPDH: Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; C:Control; SP: SP600125; SB: SB203580; NC: Nontargeting control siRNA; siRNA:Small interfering RNA.

As protease protein expression is closely associated with activity, we investigated the role of AP-1 on UVA-stimulated CatL activity. Jun and Fos knockdown significantly decreased UVA-induced CatL enzymatic activity compared with UVA-C [Figure 5d]. In addition, cotransfection remarkably reduced basal CatL expression and activity. In contrast, CatL expression and activity in UVA-treated or non-UVA-treated fibroblasts were not significantly changed by nontargeting siRNA.

Discussion

CatL, a member of cysteine Cat family, exhibits strong extracellular matrix degradation activity and participates in photoaging.[12] We demonstrated that a single UVA irradiation increased CatL expression and activity in fibroblasts for three consecutive days. Similar to our results, Klose et al.[12] reported that consecutive daily UVA irradiation (each 20 J/cm2) increased CatL expression and enhanced the extracellular release of gelatinolytic active CatL in fibroblasts. In contrast, CatL activity in fibroblasts was significantly suppressed 1 h after four consecutive daily exposures to 9.9 J/cm2 UVA, whereas its mRNA level was unchanged.[13] The discrepancy between their results and our research may be a consequence of different UVA treatment regimens. Furthermore, covalent adduction and modification of amino acid residues have been shown to be involved in the inactivation of cysteine Cats in response to electrophilic stressors (including singlet oxygen, nitroxyl, and reactive carbonyl species).[19] CatL activity is also inhibited by singlet oxygen.[20] Moreover, CatL inactivation can be antagonized by the thiol antioxidant N-acetyl-l-cysteine.[13] Based on these observations, it is possible that photooxidative stress increased by a single UVA irradiation could damage CatL activity. However, enhancement of CatL production by UVA may counteract this photooxidative inhibition and lead to enhanced enzymatic activity for three consecutive days. Enhanced CatL expression and activity contribute to extracellular matrix degradation and play roles in photodamage.

The mechanisms underlying UVA-induced CatL expression and activity are not well understood. Earlier research illustrated that mannose phosphate-independent sorting pathways were involved in mediating UVA-induced alternate trafficking of CatL.[12] Less is known about signaling pathways involved in the regulation of UVA-induced CatL expression and activity. As UVA activates MAPK pathways,[1] we further studied whether this signaling pathway plays a role in regulating UVA-induced CatL expression and activity. As shown in Figure 3a and 3b, we demonstrated that 10 J/cm2 UVA could activate JNK and p38MAPK pathways. We had previously confirmed that 800 nmol/L SP600125 and 10 μmol/L SB203580 specifically inhibited UVA-stimulated activation of JNK and p38MAPK pathways, respectively.[1] We then clarified the effect of inhibition of JNK and p38MAPK pathways on UVA-induced CatL expression and activity. Interestingly, we found that UVA-induced CatL expression and activity were significantly decreased by the inactivation of JNK pathway, but were not affected by p38MAPK inhibition [Figure 4a-4c]. These results indicate that UVA-induced CatL expression and activity are regulated by JNK signaling, but not by the p38MAPK pathway. Consistent with our results, CatL expression and activity were elevated by IL-6/sIL-6R stimulation through the caveolin-1-mediated JNK pathway, but not by the p44/42 MAPK pathway in human gingival fibroblasts.[14] However, CatL expression appears to be modulated by a complex interplay between p38 and p44/42 MAPK pathways in human fibroblasts.[15] In addition, Ruettger et al.[16] observed that both CatL and CatK expression in articular chondrocytes was enhanced by the N-terminal telopeptide of collagen Type II through p38MAPK pathway, but not through JNK pathway. Moreover, our earlier research showed that UVA-induced CatK expression correlated more with JNK activation than with p38MAPK activation.[1] Taken together, we hypothesize that UVA-induced CatL and CatK expression might be mainly regulated by JNK pathway.

Since UVA enhances AP-1 transactivation through activating MAPK pathways,[21] we hypothesize that AP-1 may play a role in the mediation of UVA-induced CatL expression and activity. As shown in Figure 5b-5d, Jun and Fos knockdown significantly decreased both basal and UVA-induced CatL expression and activity, suggesting that AP-1 is essential for UVA-induced CatL expression and activity. Similar to our findings, AP-1 has been found to regulate IL-6/sIL-6R-induced CatL expression and activity in human gingival fibroblasts.[14] Moreover, the promoter of CatL gene contains a binding site for AP-1.[14] These results support our finding that UVA activates JNK and its downstream transcript factor AP-1, leading to elevated CatL expression and activity.

It is well known that MAPK/AP-1 pathway is essential for UV-increased MMP expression.[22] We hypothesize that UV-induced expression of MMPs and CatL might be modulated by some common molecular mechanisms. The exact mechanisms need further study. CatL not only directly degrades Type I collagen, but also converts pro-urokinase into urokinase.[23] Urokinase activates plasminogen to plasmin and plasmin activates MMPs.[7] We thus postulate that MMPs and CatL may enhance each other's expression and activity during photoaging, which then increases dermis matrix degradation and photoaging. The limitation of the present study is that we did not investigate CatL expression and activity in photoaged dermal fibroblasts or skin and whether they were also regulated by JNK pathway.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that UVA enhances CatL production and activity through JNK pathway in HDFs. Knowledge regarding these molecular mechanisms will be useful in investigating the decrease in dermal collagen in photoaging. Our finding provides a new possible molecular basis for antiphotoaging therapy.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81171523 and No. 81201241), Provincial Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong (No. 2016A030313236).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by: Li-Min Chen

References

- 1.Xu Q, Hou W, Zheng Y, Liu C, Gong Z, Lu C, et al. Ultraviolet A-induced cathepsin K expression is mediated via MAPK/AP-1 pathway in human dermal fibroblasts. PLoS One. 2014;9:e102732. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102732. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chakraborti S, Mandal M, Das S, Mandal A, Chakraborti T. Regulation of matrix metalloproteinases: An overview. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;253:269–85. doi: 10.1023/a:1026028303196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quan T, Qin Z, Xia W, Shao Y, Voorhees JJ, Fisher GJ. Matrix-degrading metalloproteinases in photoaging. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2009;14:20–4. doi: 10.1038/jidsymp.2009.8. doi: 10.1038/jidsymp.2009.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malemud CJ. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) in health and disease: An overview. Front Biosci. 2006;11:1696–701. doi: 10.2741/1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chapman HA, Riese RJ, Shi GP. Emerging roles for cysteine proteases in human biology. Annu Rev Physiol. 1997;59:63–88. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.59.1.63. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.59.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park HS, Jin SP, Lee Y, Oh IG, Lee S, Kim JH, et al. Toll-like receptor 2 mediates a cutaneous reaction induced by repetitive ultraviolet B irradiation in C57/BL6 mice in vivo. Exp Dermatol. 2014;23:591–5. doi: 10.1111/exd.12477. doi: 10.1111/exd.12477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fleetwood AJ, Achuthan A, Schultz H, Nansen A, Almholt K, Usher P, et al. Urokinase plasminogen activator is a central regulator of macrophage three-dimensional invasion, matrix degradation, and adhesion. J Immunol. 2014;192:3540–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302864. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lai W, Zheng Y, Ye ZZ, Su XY, Wan MJ, Gong ZJ, et al. Changes of cathepsin B in human photoaging skin both in vivo and in vitro. Chin Med J. 2010;123:527–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vasiljeva O, Reinheckel T, Peters C, Turk D, Turk V, Turk B. Emerging roles of cysteine cathepsins in disease and their potential as drug targets. Curr Pharm Des. 2007;13:387–403. doi: 10.2174/138161207780162962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bylaite M, Moussali H, Marciukaitiene I, Ruzicka T, Walz M. Expression of cathepsin L and its inhibitor hurpin in inflammatory and neoplastic skin diseases. Exp Dermatol. 2006;15:110–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2005.00389.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2005.00389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walz M, Kellermann S, Bylaite M, Andrée B, Rüther U, Paus R, et al. Expression of the human cathepsin L inhibitor hurpin in mice: Skin alterations and increased carcinogenesis. Exp Dermatol. 2007;16:715–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2007.00579.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2007.00579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klose A, Wilbrand-Hennes A, Brinckmann J, Hunzelmann N. Alternate trafficking of cathepsin L in dermal fibroblasts induced by UVA radiation. Exp Dermatol. 2010;19:e117–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2009.01014.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2009.01014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lamore SD, Wondrak GT. UVA causes dual inactivation of cathepsin B and L underlying lysosomal dysfunction in human dermal fibroblasts. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2013;123:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2013.03.007. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamaguchi T, Naruishi K, Arai H, Nishimura F, Takashiba S. IL-6/sIL-6R enhances cathepsin B and L production via caveolin-1-mediated JNK-AP-1 pathway in human gingival fibroblasts. J Cell Physiol. 2008;217:423–32. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21517. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Urbanelli L, Trivelli F, Ercolani L, Sementino E, Magini A, Tancini B, et al. Cathepsin L increased level upon Ras mutants expression: The role of p38 and p44/42 MAPK signaling pathways. Mol Cell Biochem. 2010;343:49–57. doi: 10.1007/s11010-010-0497-3. doi: 10.1007/s11010-010-0497-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruettger A, Schueler S, Mollenhauer JA, Wiederanders B. Cathepsins B, K, and L are regulated by a defined collagen type II peptide via activation of classical protein kinase C and p38 MAP kinase in articular chondrocytes. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:1043–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704915200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704915200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silvers AL, Bachelor MA, Bowden GT. The role of JNK and p38 MAPK activities in UVA-induced signaling pathways leading to AP-1 activation and c-Fos expression. Neoplasia. 2003;5:319–29. doi: 10.1016/S1476-5586(03)80025-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levicar N, Dewey RA, Daley E, Bates TE, Davies D, Kos J, et al. Selective suppression of cathepsin L by antisense cDNA impairs human brain tumor cell invasion in vitro and promotes apoptosis. Cancer Gene Ther. 2003;10:141–51. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700546. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krohne TU, Kaemmerer E, Holz FG, Kopitz J. Lipid peroxidation products reduce lysosomal protease activities in human retinal pigment epithelial cells via two different mechanisms of action. Exp Eye Res. 2010;90:261–6. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2009.10.014. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagaoka Y, Otsu K, Okada F, Sato K, Ohba Y, Kotani N, et al. Specific inactivation of cysteine protease-type cathepsin by singlet oxygen generated from naphthalene endoperoxides. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;331:215–23. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.146. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fisher GJ, Voorhees JJ. Molecular mechanisms of photoaging and its prevention by retinoic acid: Ultraviolet irradiation induces MAP kinase signal transduction cascades that induce Ap-1-regulated matrix metalloproteinases that degrade human skin in vivo. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 1998;3:61–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim SR, Jung YR, An HJ, Kim DH, Jang EJ, Choi YJ, et al. Anti-wrinkle and anti-inflammatory effects of active garlic components and the inhibition of MMPs via NF-κB signaling. PLoS One. 2013;8:e73877. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073877. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ikeda Y, Ikata T, Mishiro T, Nakano S, Ikebe M, Yasuoka S. Cathepsins B and L in synovial fluids from patients with rheumatoid arthritis and the effect of cathepsin B on the activation of pro-urokinase. J Med Invest. 2000;47:61–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]