Abstract

Gut microbiota mediate the nutritional metabolism and play important roles in human obesity. Diapausing insects accumulate large fat reserves and develop obese phenotypes in order to survive unfavorable conditions. However, the possibility of an association between gut microbiota and insect diapause has not been investigated. We used the Illumina MiSeq platform to compare gut bacterial community composition in nondiapause- (i.e. reproductive) and diapause-destined female cabbage beetles, Colaphellus bowringi, a serious pest of vegetables in Asia. Based on variation in the V3-V4 hypervariable region of 16S ribosomal RNA gene, we identified 99 operational taxonomic units and 17 core microbiota at the genus level. The relative abundance of the bacterial community differed between reproductive and diapause-destined female adults. Gut microbiota associated with human obesity, including Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, and Proteobacteria, showed a good correlation with diapause. This association between gut microbiota and diapause in the cabbage beetle may open a new avenue for studying insect diapause, as well as developing a natural insect obesity model with which to explore the mechanisms responsible for human obesity.

Many animals, such as nematodes, crustaceans, fish and insects, have evolved diapause (a programmed arrest of development during specific life stages) to adapt to seasonal changes and survive unfavorable environmental conditions1,2. Diapause-destined individuals generally store large fat reserves for diapause maintenance and post-diapause development1,3,4. However, it remains unclear how lipid is accumulated during diapause preparation, an important stage before diapause itself5.

Reproductive diapause in insects is restricted to the adult stage and is characterized by arrested ovary development in females, increased stress tolerance and lipid accumulation during diapause preparation6,7,8. Conversely, non-diapausing, reproductive insects store more proteins and carbohydrates in the ovary during the pre-oviposition period4. Interestingly, fat storage in diapausing insects seems to coincide with obese phenotypes9 suggesting that studies of animal obesity may help understand diapause.

In recent years a growing body of evidence has demonstrated the close relationship between gut microbiota and obesity in mammals10. The human gut contains an immense number of commensal bacteria that collectively comprise a special metabolic ‘organ’ and plays an important role in regulating nutrition11,12. For example, by upregulating de novo fatty acid biosynthetic gene expression, and increasing lipoprotein lipase activity, the gut microbiota of mice can induce triglyceride storage in adipocytes leading to an obese phenotype13. In insects, a large number of bacteria also colonize the gut and modulate nutritional metabolism by providing digestive enzymes and vitamins that improve digestive efficiency14. For example, the gut microbiota of Drosophila melanogaster produce bioactive metabolites that regulate lipid absorption and storage15. Therefore, gut microbiota play a key role in the regulation of lipid storage in both mammals and insects. The obese phenotypes of diapausing insects raises the question of whether gut microbiota also play a role in lipid accumulation during diapause preparation.

To address this question, we investigated the association between gut microbiota and reproductive diapause preparation in the cabbage beetle, Colaphellus bowringi, a serious pest of vegetables in Asia16. The 4 day period post-eclosion (PE) is the pre-oviposition period of reproductive female C. bowringi and the diapause preparation period of diapause-destined females. Both types of female feed intensively during this period. Nutrients in reproductive females are mainly stored in the ovary in the form of proteins, while nutrients in diapause-destined females are primarily channeled to the fat body (the adipose and metabolic tissue of insects) in the form of triglycerides4. These two different patterns of nutrient distribution make an important contribution to subsequent reproduction or diapause3,17. The observation that both diapausing C. bowringi and obese humans accumulate lipids led us to suspect that gut microbiota, which have been found to mediate obesity in mammals10, may be involved in the regulation of nutritional metabolism in diapause-destined female adults. To address this question, we compared the community composition of the gut bacteria of nondiapause-destined (hereafter reproductive), and diapause-destined, female adults by sequencing the V3-V4 hypervariable region of the 16S ribosomal RNA gene. Our discovery of an association between gut microbiota and insect diapause preparation may open a new avenue for the study of insect diapause.

Results and Discussion

Richness and diversity of gut microbiota

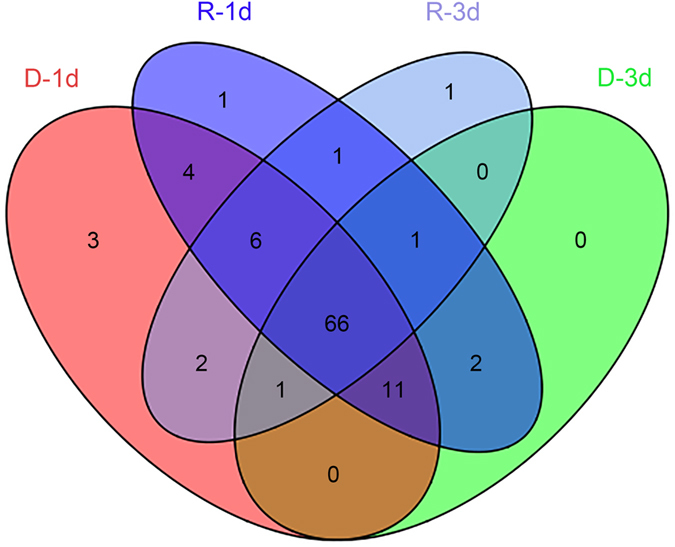

To ask whether gut microbiota is associated with diapause, we compared the composition and diversity of the gut microbiota of reproductive and diapause-destined female C. bowringi at 1 and 3 days PE (Fig. 1). By sequencing the V3-V4 hypervariable region of the 16S ribosomal RNA gene and removing chimeric sequences and mismatches, we obtained 259,308 effective reads from four independent biological replicates of samples collected from reproductive (R-1d and R-3d) and diapause preparation (D-1d and D-3d) females (Fig. 1). Ninety-eight operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were identified (see Supplementary Table S1), of which 66 appeared in all samples (Fig. 2). After excluding the same taxonomic groups from these 66 OTUs, 17 core microbiota at the genus level were confirmed (Table 1). From the 98 OTUs, we identified 6 phyla, 11 classes, 21 orders, 35 families, 37 genera and 12 species. In detail, the 12 species were from the 10 identified genera, and the other 27 genera had not been annotated to species due to the very similar sequences of near-neighbor species. Nonetheless, these results indicate a high diversity of gut microbiota in both reproductive and diapause-destined female C. bowringi.

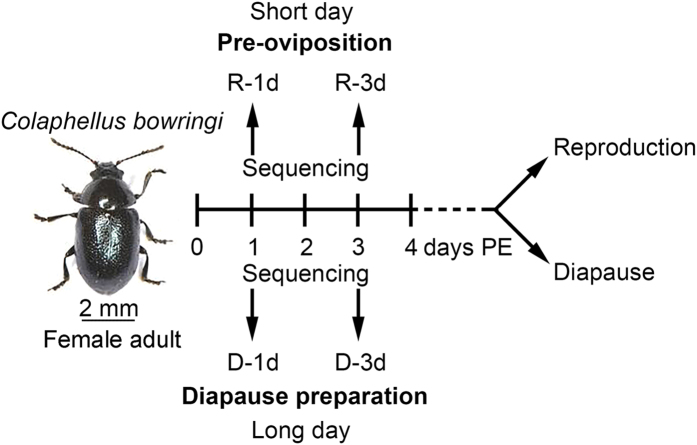

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of the experimental design used in this study.

Reproductive females were obtained by raising larvae at 25 °C under a 12:12 h light:dark (LD) photoperiod and diapause-destined females by raising larvae at 25 °C under 16:8 LD photoperiod. Reproductive and diapause-destined female adults store energy obtained from plant foods in the ovary and the fat body, respectively, during the 4 day post-eclosion (PE) period. Gut microbiota were collected for sequencing from reproductive (R) and diapause-destined (D) females at 1 and 3 days PE. R-1d, reproductive adult at 1 day PE; R-3d, reproductive adult at 3 days PE; D-1d, diapause-destined adult at 1 day PE; D-3d, diapause-destined adult at 3 days PE.

Figure 2. Venn diagram of OTU abundance in in reproductive (R) and diapause-destined (D) female cabbage beetles, Colaphellus bowringi, 1 and 3 days (d) post-eclosion.

Table 1. The 17 core microbiota at the genus level in the gut of nondiapause- and diapause-destined C. bowringi during the 4 days post-eclosion.

| OTUs | Genera |

|---|---|

| OTU2 | Acinetobacter |

| OTU3 | Wolbachia |

| OTU6 | Enterobacter |

| OTU7 | Delftia |

| OTU9 | Pseudomonas |

| OTU10 | Stenotrophomonas |

| OTU11 | Agrobacterium |

| OTU12 | Wautersiella |

| OTU13 | Sphingobacterium |

| OTU14 | Chryseobacterium |

| OTU17 | Serratia |

| OTU20 | Sphingomonas |

| OTU21 | Rhodoferax |

| OTU28 | Methylobacterium |

| OTU41 | Citrobacter |

| OTU42 | Arthrobacter |

| OTU45 | Vagococcus |

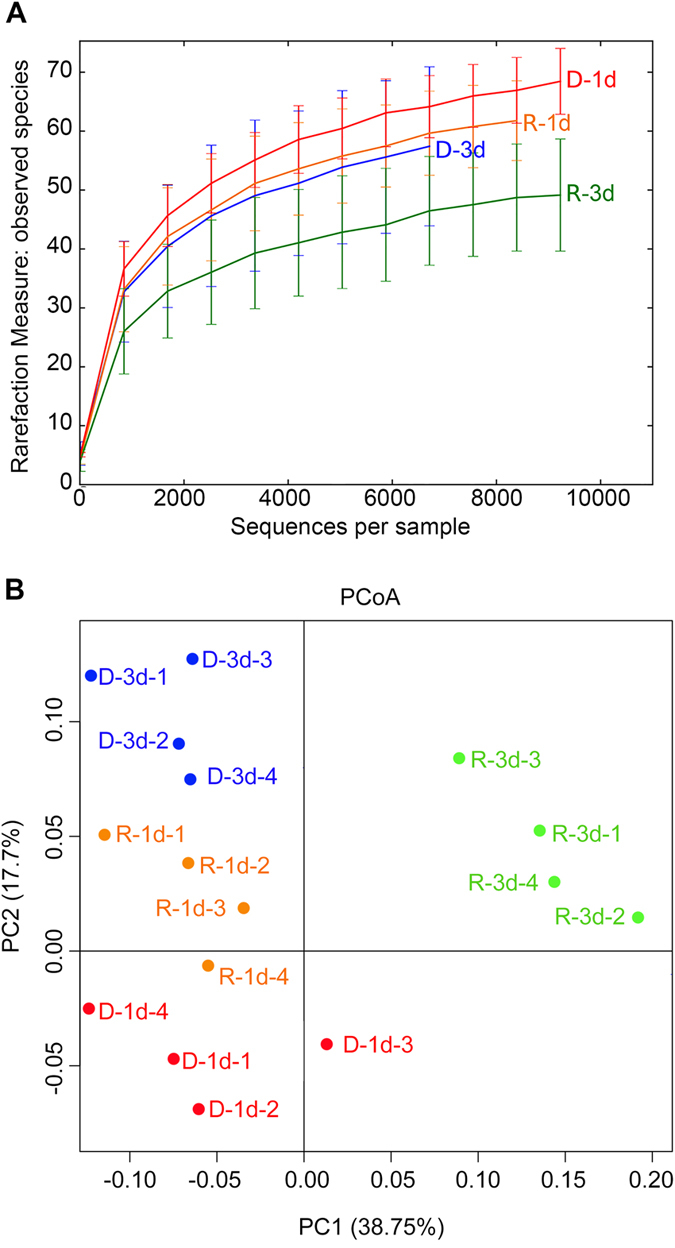

The number of microbiota species identified eventually plateaued, indicating that sufficient sequencing data had been obtained (Fig. 3A). After the normalization of data by referencing the minimum number of sequences (D-3d), the phase difference between D-1d and R-3d groups indicated an apparent difference (P = 0.032) in the diversity of gut microbiota between reproductive and diapause-destined females. In addition, the microbiota of both reproductive and diapause-destined females seem to have higher species diversity at 1d than at 3d PE although the differences were not significant (reproduction, P = 0.097; diapause, P = 0.362). Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA, weighted UniFrac) further indicated that the structure of gut microbiota in R-3d is different (ANOSIM P = 0.040) from D-1d (Fig. 3B). However, the structure of gut microbiota in reproductive (ANOSIM P = 0.090) or diapause (ANOSIM P = 0.100) individuals at 1d PE is similar to 3d PE. Hence, gut microbiota diversity and structure seems to be associated with reproductive status but not time PE. Therefore, it’s possible that the observed changes in the structure of the gut bacterial community of C. bowringi benefit either reproduction or diapause preparation.

Figure 3.

A rarefaction curve (A) and the Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) analysis (B). The rarefaction curve and PCoA analysis, were generated from sequencing four independent biological replicates from each treatment with QIIME, and shows the rationality of sequencing data and the species abundance in each treatment. R-1d-1 represents the first independent biological replicate of R-1d, the others are deduced by analogy.

Taxonomy-based comparisons of gut microbiota

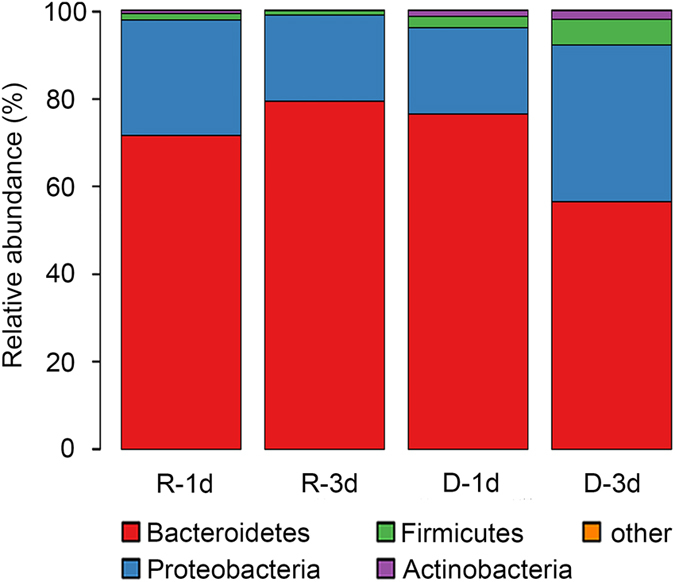

We analyzed the relative abundance of gut microbiota at different taxonomic levels in order to identify those that were reproductive and diapause-related. At the phylum level, Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria were predominant (>98%), followed by the Firmicutes and Actinobacteria (Fig. 4). In the vertebrate gut, 80–90% of resident bacteria are Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes, followed by Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria18,19. This similar community composition indicates the conserved function of gut microbiota from invertebrates to vertebrates.

Figure 4. The relative abundance of gut microbiobial phyla in reproductive (R) and diapause-destined (D) female cabbage beetles, Colaphellus bowringi, 1 and 3 days (d) post-eclosion.

The abundance of Bacteroidetes was higher in the R-3d than in the D-3d group (P = 0.045), but the abundance of Proteobacteria (P = 0.049) and Firmicutes (P = 0.048) was lower in the R-3d than in the D-3d group (Fig. 4). There were no significant differences of the abundance of these bacteria between R-1d and D-1d groups (P > 0.05). These results suggest a positive correlation between the Proteobacteria, Firmicutes and diapause preparation, and a negative correlation between the Bacteroidetes and diapause preparation. Interestingly, a similar pattern has been reported in a study of mammalian obesity; compared to lean mice, obese mice underwent a 50% increase in the abundance of Firmicutes and a proportional reduction in that of Bacteroidetes20. Therefore, the accumulation of lipids in diapause-destined C. bowringi4 may be associated with an increase in human obesity-associated gut microbiota, such as Firmicutes. Some studies of rodents and humans have reached the opposite conclusion regarding the function of Proteobacteria in obesity21,22,23, but most available evidence suggests that Proteobacteria can regulate host obesity24. Therefore, we think it possible that the higher abundance of Proteobacteria in diapause-destined C. bowringi may be related to fat storage during diapause preparation4.

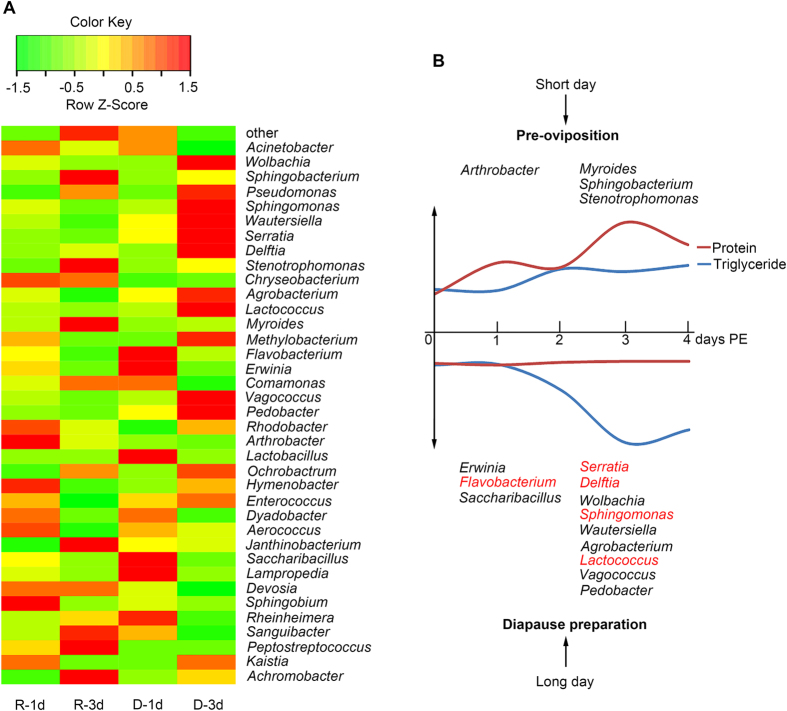

We next analyzed the distribution of gut bacteria communities at the genus level to infer the specific function of microbiota in reproduction and diapause (Fig. 5A). Arthrobacter (P = 0.045) was the dominant genus in the R-1d group. However, Myroides (P = 0.003), Sphingobacterium (P = 0.036), and Stenotrophomonas (P = 0.045) were the main genera in the R-3d group. These results suggest that these genera may be involved in the reproductive development of C. bowringi. There is evidence that an endocellular bacterial symbiont, Buchnera aphidicola, can influence the reproduction of aphids by regulating host amino acid biosynthesis25,26. Gut bacteria communities also are essential for insects’ reproduction27,28. Therefore, the specific gut microbiota associated with reproductive development in this study may contribute to reproduction in C. bowringi.

Figure 5. The distribution of gut microbiota at the genus level during the four day post- eclosion period in reproductive and diapause-destined female C. bowringi.

(A) Heatmap of the relative abundance of bacterial communities at the genus level in each treatment. (B) Model of genus differences (P < 0.05) in gut microbiota between reproductive and diapause-destined female C. bowringi at 25 °C. Red font denotes the gut microbiota associated with mammalian obesity and nutritional metabolism. Trends in various nutrients over the four day post-eclosion period were generated from data from previous work4.

The proportion of Flavobacterium (P = 0.002), Saccharibacillus (P = 0.006), and Erwinia (P = 0.004) were highest in the D-1d group (Fig. 5A). However, at the key stage for pre-diapause lipid accumulation (D-3d), Wautersiella (P = 0.018), Pedobacter (P = 0.031), Vagococcus (P = 0.041), Lactococcus (P = 0.020), Delftia (P = 0.036), Serratia (P = 0.044), Agrobacterium (P = 0.009), Sphingomonas (P = 0.041), and Wolbachia (P = 0.029) were the dominant genera. Although our results suggest that Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, and Proteobacteria are associated with diapause, at the genus level these microbiota seem to regulate both reproduction and diapause. Nonetheless, Flavobacterium, which has been identified as obesity-associated gut microbiota in mammals20,24, were associated with diapause (P < 0.05). In addition, obesity-related microbiota, including Lactococcus29 (P = 0.020), Delftia30 (P = 0.036), Serratia31 (P = 0.044), and Sphingomonas32 (P = 0.041), were also more abundant in diapause-destined female C. bowringi. In summary, most of the gut microbiota associated with diapause in C. bowringi are the same as those associated with obesity in mammals.

A schematic representation of the association between gut microbiota genera and the nutritional metabolism of reproductive and diapause-destined C. bowringi is shown in Fig. 5B. Based on previous studies of mammalian obesity and insect nutritional metabolism, we think that triglyceride accumulation in diapause-destined female adults is associated with specific genera of gut microbiota. Although further study is needed to verify the exact relationships between bacterial genera and lipid accumulation, we believe that the results presented in this paper may open a new avenue for studying insect diapause, and also allow the development of a natural insect obesity model with which to exploring the mechanisms of human obesity. In addition, given the fact that diapause is controlled by the endocrine system33, we speculate that gut microbiota may interact with hormone signaling pathways to regulate diapause. Further research on diapause, as well as that on human obesity and metabolic disorders, should take into account the possibility of such communication between the endocrine system and gut microbiota.

Methods

Insect rearing

C. bowringi were originally collected from Xiushui County (29°10 N, 114°40E), Jiangxi Province, China, and maintained in our laboratory on radish, Raphanus sativus L. var. longipinnatus (Brassicales: Brassicaceae)34. We obtained nondiapause-destined (reproductive) adults by rearing larvae at 25 °C under a 12:12 h light:dark photoperiod, and diapause-destined adults by rearing larvae at 25 °C under the 16:8 h light:dark photoperiod16. During the 4 day PE period, proteins and carbohydrates are stored in the ovary of reproductive females, while lipids (triglycerides) are accumulated in the fat body of diapause-destined females4. Hence, we hypothesized that different gut microbiota may be involved in each case, and collected samples from both reproductive and diapause-destined females at 1 and 3 days PE (Fig. 1A).

Gut microbiota collection, DNA extraction and sequencing

We set up four experimental treatments, including R-1d, R-3d, D-1d, and D-3d. Each treatment had four independent biological replicates, and each replicate required a mixture of gut samples from 20 adult females. To Prior to dissection, the females were soaked in 70% ethanol for 3 minutes, and rinsed three times in sterile phosphate-buffered saline. Gut samples were dissected from females with sterilized tweezers and eye scissors under a stereomicroscope. During dissection, we also observed ovarian development to confirm the reproductive, or pre-diapause, status of females as appropriate. Total metagenomic DNA were extracted and purified from gut samples with a Universal Genomic DNA Kit (CwBio, Inc., Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration of metagenomic DNA was measured using Qubit Platform (Life Technologies, CA, USA). The V3-V4 hypervariable region of 16S ribosomal RNA gene was amplified from 30 ng of each metagenomic DNA in triplicate polymerase chain reactions (PCR) with Pyrobest DNA polymerase (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) and the forward and reverse primers 5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3′ and 5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′35 (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Barcode sequences (see Supplementary Table S2) were attached to the amplification primers to distinguished the different samples. PCR products were viewed on 2% agarose electrophoresis gel and the respective amplicon libraries generated. Gut microbial DNA was then sequenced by Honortech (Beijing, China) using the Illumina MiSeq platform.

Bioinformatics statistics

Based on the raw data (The Sequence Read Archive accession: SRP078307), pair-end reads were spliced using the principle of 98% overlap of 19 bases using Connecting Overlapped Pair-End software36. Barcode and primer sequences were then filtered to obtain clean data. Operational Taxonomic Unit (OTU) generation and clustering were done with USEARCH37 on the basis of 97% identity. Singletons were not used for clustering, only for OTU quantification. Core microbiota was identified with QIIME38. UCLUST37 and GreenGenes39 were used to perform species annotation of OTUs under a similarity threshold of 90–100%. The same sequencing depth was used to compare the alpha-diversity, beta-diversity, and the abundance of 16S metagenome data. Species diversity was determined by drawing a rarefaction curve and PCoA analysis with QIIME38. The relative abundance of gut microbiota was calculated according to the species annotation and reads number. A heatmap of the relative abundance of gut microbiota at the genus level was generated using custom Perl scripts. The transformed data of relative abundance were based on the Z-scores, which were calculated by the following formula.

|

The x is a raw score, μ is the mean of the population, and σ is the standard deviation of the population. We analyized the significant difference between the two groups of samples with different taxonomic levels using metastats40. “P” value shows the test of significance, and P < 0.05 indicates the significant difference.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Liu, W. et al. Association between gut microbiota and diapause preparation in the cabbage beetle: a new perspective for studying insect diapause. Sci. Rep. 6, 38900; doi: 10.1038/srep38900 (2016).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Prof. Fang-Sen Xue (Jiangxi Agricultural University, China) for his assistance with insect collection. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 31272045 and 31501897, 31572009), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Program No. 2014BQ012).

Footnotes

Author Contributions X.-P.W. and W.L. designed the experiment, analyized the data and wrote the manuscript. H.Y. reared the insects. Y.L. and S.G. collected the gut samples. C.-L.L. directed the research. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Hand S. C., Denlinger D. L., Podrabsky J. E. & Roy R. Mechanisms of animal diapause: recent developments from nematodes, crustaceans, insects, and fish. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 310, R1193–1211, doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00250.2015 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salminen T. S. et al. Seasonal gene expression kinetics between diapause phases in Drosophila virilis group species and overwintering differences between diapausing and non-diapausing females. Sci. Rep. 5, 11197, doi: 10.1038/srep11197 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn D. A. & Denlinger D. L. Energetics of insect diapause. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 56, 103–121, doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-112408-085436 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan Q. Q. et al. Differences in the pre-diapause and pre-oviposition accumulation of critical nutrients in adult females of the beetle Colaphellus bowringi. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 160, 117–125, doi: 10.1111/eea.12464 (2016). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Denlinger D. L. Regulation of diapause. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 47, 93–122, doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.47.091201.145137 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds J. A., Poelchau M. F., Rahman Z., Armbruster P. A. & Denlinger D. L. Transcript profiling reveals mechanisms for lipid conservation during diapause in the mosquito, Aedes albopictus. J. Insect Physiol. 58, 966–973, doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2012.04.013 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denlinger D. L. & Armbruster P. A. Mosquito diapause. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 59, 73–93, doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-011613-162023 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajgar A., Jindra M. & Dolezel D. Autonomous regulation of the insect gut by circadian genes acting downstream of juvenile hormone signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 4416–4421, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217060110 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denlinger D. L. Why study diapause? Entomol. Res. 38, 1–9 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Musso G., Gambino R. & Cassader M. Interactions between gut microbiota and host metabolism predisposing to obesity and diabetes. Annu. Rev. Med. 62, 361–380, doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-012510-175505 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara A. M. & Shanahan F. The gut flora as a forgotten organ. EMBO Rep. 7, 688–693 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bäckhed F., Ley R. E., Sonnenburg J. L., Peterson D. A. & Gordon J. I. Host-bacterial mutualism in the human intestine. Science 307, 1915–1920 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bäckhed F. et al. The gut microbiota as an environmental factor that regulates fat storage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 15718–15723 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon R. J. & Dillon V. M. The gut bacteria of insects: nonpathogenic interactions. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 49, 71–92, doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.49.061802.123416 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong A. C., Vanhove A. S. & Watnick P. I. The interplay between intestinal bacteria and host metabolism in health and disease: lessons from Drosophila melanogaster. Dis. Model. Mech. 9, 271–281 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue F., Spieth H. R., Li A. Q. & Ai H. The role of photoperiod and temperature in determination of summer and winter diapause in the cabbage beetle, Colaphellus bowringi (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). J. Insect Physiol. 48, 279–286 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W. et al. Juvenile hormone facilitates the antagonism between adult reproduction and diapause through the methoprene-tolerant gene in the female Colaphellus bowringi. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 74, 50–60, doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2016.05.004. (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckburg P. B. et al. Diversity of the human intestinal microbial flora. Science 308, 1635–1638 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cani P. D. & Delzenne N. M. Interplay between obesity and associated metabolic disorders: new insights into the gut microbiota. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 9, 737–743 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley R. E. et al. Obesity alters gut microbial ecology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 11070–11075 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy E. et al. Composition and energy harvesting capacity of the gut microbiota: relationship to diet, obesity and time in mouse models. Gut 59, 1635–1642 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H. et al. Human gut microbiota in obesity and after gastric bypass. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 2365–2370 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everard A. et al. Responses of gut microbiota and glucose and lipid metabolism to prebiotics in genetic obese and diet-induced leptin-resistant mice. Diabetes 60, 2775–2786 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin N.-R., Whon T. W. & Bae J.-W. Proteobacteria: microbial signature of dysbiosis in gut microbiota. Trends Biotechnol. 33, 496–503 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai C.-Y., Baumann L. & Baumann P. Amplification of trpEG: adaptation of Buchnera aphidicola to an endosymbiotic association with aphids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 3819–3823 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigenobu S., Watanabe H., Hattori M., Sakaki Y. & Ishikawa H. Genome sequence of the endocellular bacterial symbiont of aphids Buchnera sp. APS. Nature 407, 81–86 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosokawa T., Kikuchi Y., Nikoh N., Shimada M. & Fukatsu T. Strict host-symbiont cospeciation and reductive genome evolution in insect gut bacteria. PLoS Biol. 4, e337 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel P. & Moran N. A. The gut microbiota of insects–diversity in structure and function. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 37, 699–735 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drouault S., Juste C., Marteau P., Renault P. & Corthier G. Oral treatment with Lactococcus lactis expressing Staphylococcus hyicus lipase enhances lipid digestion in pigs with induced pancreatic insufficiency. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68, 3166–3168 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whisner C. M. & Bruening M. Associations between physical activity and the intestinal microbiome of college freshmen. FASEB J. 30, 146.142–146.142 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Chiu C.-M. et al. Systematic analysis of the association between gut flora and obesity through high-throughput sequencing and bioinformatics approaches. Biomed Res. Int. 2014 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldram A. et al. Top-down systems biology modeling of host metabotype− microbiome associations in obese rodents. J. Proteome. Res. 8, 2361–2375 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denlinger D., Yocum G. & Rinehart J. 10 Hormonal Control of Diapause. 430–463 (Elsevier, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- Tan Q. Q. et al. A de novo transcriptome and valid reference renes for quantitative Real-Time PCR in Colaphellus bowringi. PLoS One 10, e0118693, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118693 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadrosh D. W. et al. An improved dual-indexing approach for multiplexed 16S rRNA gene sequencing on the Illumina MiSeq platform. Microbiome 2, 6, doi: 10.1186/2049-2618-2-6 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B. et al. COPE: an accurate k-mer-based pair-end reads connection tool to facilitate genome assembly. Bioinformatics 28, 2870–2874 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 26, 2460–2461 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso J. G. et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods 7, 335–336 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner J. J. et al. Impact of training sets on classification of high-throughput bacterial 16s rRNA gene surveys. ISME J. 6, 94–103 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White J. R., Nagarajan N. & Pop M. Statistical methods for detecting differentially abundant features in clinical metagenomic samples. PLoS Comput. Biol. 5, e1000352 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.