Abstract

Background:

Early in the global response to HIV, health communication was focused toward HIV prevention. More recently, the role of health communication along the entire HIV care continuum has been highlighted. We sought to describe how a strategy of interpersonal communication allows for precision health communication to influence behavior regarding care engagement.

Methods:

We analyzed 1 to 5 transcripts from clients participating in longitudinal counseling sessions from a communication strategy arm of a randomized trial to accelerate entry into care in South Africa. The counseling arm was selected because it increased verified entry into care by 40% compared with the standard of care. We used thematic analysis to identify key aspects of communication directed specifically toward a client's goals or concerns.

Results:

Of the participants, 18 of 28 were female and 21 entered HIV care within 90 days of diagnosis. Initiating a communication around client-perceived consequences of HIV was at times effective. However, counselors also probed around general topics of life disruption—such as potential for child bearing—as a technique to direct the conversation toward the participant's needs. Once individual concerns and needs were identified, counselors tried to introduce clinical care seeking and collaboratively discuss potential barriers and approaches to overcome to accessing that care.

Conclusions:

Through the use of interpersonal communication messages were focused on immediate needs and concerns of the client. When effectively delivered, it may be an important communication approach to improve care engagement.

Key Words: linkage to care, HIV, health communication, Africa, interpersonal

INTRODUCTION

Achieving the promise of antiretroviral therapy (ART) to reduce HIV-associated mortality and transmission in sub-Saharan Africa relies on increasing behavioral change toward earlier engagement and sustained retention in HIV care after HIV diagnosis.1–3 Health communication may be an important component of increasing care seeking during the period between testing HIV positive and entry into care.4–7 Such communication may take several forms, including interpersonal health communication (IPC). IPC can bring constructs of client autonomy and shared decision making to health communication. By being as relevant as possible using a “precision health communication” approach, the chance of behavior change may be maximized. Such precision communication may bring the client to move more rapidly from testing positive to accessing care and initiating ART.

Although the value of IPC is appreciated in HIV care,8–11 there has been a limited application of structured approaches of IPC for the step of the care continuum from testing positive to entry into care. Furthermore, much of the published literature describes the effect of communication strategies on specific outcomes without description or analysis of the communication itself. We explored how IPC using a structured, strength-based, and motivational counseling approach can assist clients in enunciating their goals, describe pathways to achieving those goals, and identify potential challenges to consider along those pathways. This may enable clients to consider specific barriers and embrace a specific care-seeking plan. Using data collected from a randomized entry-into-care study (Thol'impilo study), we analyzed the content of longitudinal counseling sessions to describe how structured IPC can provide precision health communication to encourage care seeking.

METHODS

Population

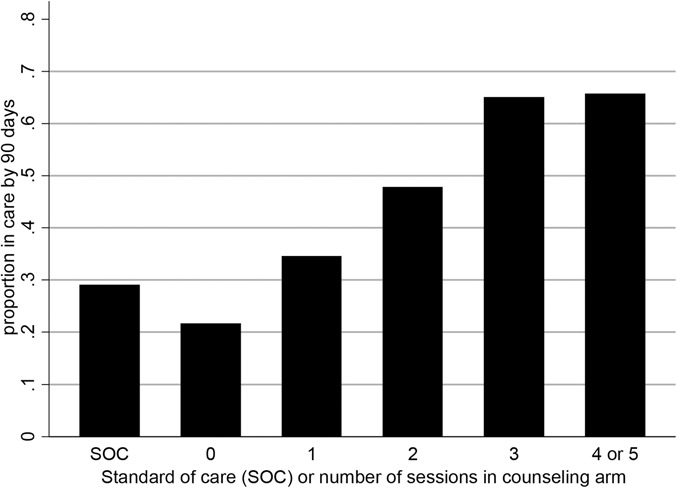

Thol'impilo was a randomized pragmatic trial of strategies to accelerate entry into care after testing HIV positive at mobile HIV counseling and testing (HCT) units in South Africa. Three strategies were compared with the standard of care of a referral letter: (1) point-of-care CD4 count testing and health staging, (2) point-of-care CD4 count testing and longitudinal counseling, and (3) point-of-care CD4 count testing and reimbursement for the cost of travel to clinics. Entry into care was 40% higher for clinic-verified entry into care in the counseling arm when compared with the standard of care12; in the counseling arm, entry into care appeared correlated with the number of sessions attended (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Proportion in care within 90 days from testing HIV positive and number of counseling sessions completed (χ2 P for difference between arms, 0.002).

Longitudinal Counseling Sessions

Counseling sessions were provided using a structured, strength-based, and motivational counseling approach.7 Participants received up to 5 counseling sessions up to 90 days from enrollment. Each session was designed to follow a structured curriculum progressing from identifying client goals to determining strengths and finally entry into care.

Through the use of IPC between the client and the counselor, we aimed to empower clients and influence their decisions by allowing them to critically assess their preferences and needed resources for managing their HIV diagnosis. As a starting point, counselors applied inquiry and reflective feedback techniques to identify a client's immediate concerns. Specific well-characterized barriers that counselors could use to initiate discussion were internalized stigma, lack of HIV and/or treatment-related knowledge, use of nonallopathic HIV care services, perceived value of seeking HIV clinical care, and context-specific costs associated with seeking HIV clinical care.13 The ultimate goal was to engage the participant in self-identifying barriers or facilitators. Counseling sessions were provided telephonically or in-person at a mutually convenient and safe location. Counselors had formal training as either a social worker or auxiliary social worker, and they received additional training on the South African guidelines for the management of HIV in adults, adherence counseling, disclosure counseling, strength-based approaches, and motivational interviewing.

Study participants tested HIV positive at a mobile HCT unit were ≥18 years old, capable of providing informed consent, reported not receiving HIV-related care at the time of diagnosis, and had been randomized to the longitudinal counseling arm.

For this substudy, 28 participants were randomly selected from the 384 participants in the longitudinal counseling strategy arm who had attended at least 1 counseling session. We replaced randomly selected participants until we included participants from each of the following categories: male/female, rural/urban residence, and ART eligibility at the time of diagnosis (CD4 count ≤ 350 and >350 cells/mm3). Audio-recorded sessions were transcribed and translated into English. A total of 50 sessions were reviewed, 30 in-person session transcripts and 20 telephonic transcripts.

This trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02271074) and the South African National Research Ethics Council DOH-27-0713-4480. Ethics approvals were provided by the University of the Witwatersrand Human Research Ethics Committee and the Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board. All participants provided written informed consent.

Analysis

Inductive thematic analysis was used to identify, analyze, and report on themes from the interaction between the counselor and client.14 Potential themes were collaboratively developed by 2 of the researchers (T.M. and C.J.H.), examining and reviewing the codes to identify patterned communication content and relational processes. NVivo 10 (version 10, 2012; QSR International Pty Ltd, Melborne, Australia) software was used for data management and coding.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

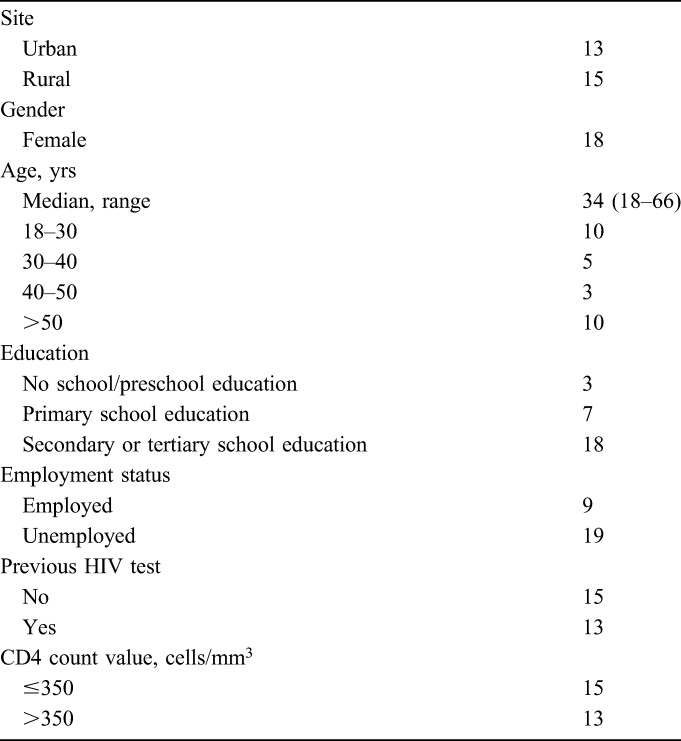

Of the participants, most were female (18/28) and age ranged from 18 to 66 years (Table 1). Seven participants had entered care before attending the first session, whereas 16 of the remaining 21 clients entered care during the course of the intervention period (90 days post diagnosis). Among those who failed to enter care, 1 client had reached the maximum number of sessions, whereas the remaining 4 did not attend all 5 sessions.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of 28 Participants Selected for Counselling Session Analysis

Delivery of Sessions

Face-to-face sessions had longer median duration (45 minutes; interquartile range, 30–50 minutes) compared with telephonic sessions (29 minutes; interquartile range, 25–46 minutes). Telephonic sessions were often affected by poor network connections. Participants exhibited frustrations in repeating themselves, especially when they were uncomfortable in their environment and wanted to be discrete. Another challenge with communication was the existence of language barriers. One client appointed a translator, whereas in other cases, attempts were made to converse using basic knowledge of the dominant language in the area—which all counselors were versant in. Some clients had minimal tolerance for these complexities. The example below is of a client who in her frustration, terminated the telephonic session and never answered any calls thereafter.

P: No. I have answered you already … I told you that my problems come from people who did this [witchcraft]. You asked and I answered.

CF: Sometimes, I don't get it clearly mama.

P: You don't understand Sepedi [local language with different dialects] well do you? Where do you come from? [female, 49 years, rural].

Content of the Sessions

Building the Foundation for Precision Health Communication

The counseling sessions started with questions to explore the practical consequences of the HIV diagnosis to the client's everyday life. This guided a mutual understanding of the client's primary goals and served as a foundation for further discussion. Although simple in concept, in practice, bringing a client to identify primary goals was often a challenge as illustrated by the following transcripts.

Client: I am beginning to think that my life might end any day from now. I might die any day. I will die and leave my children behind. I want to know what I need to do when things are like this. I want to know if I will get any treatment …. I am stressed now because I was not sleeping around. I don't understand how I got this virus! [female, 22 years, urban].

Client: It is very difficult my brother. I have not yet disclosed to my partner about my status. I am scared; I don't know how I am going to break the news to her. This is the challenge I am faced with. I am worried I might end up infecting her with HIV [male, 40 years, rural].

Client: I don't believe the results [HIV test results] … I am very confused, and I want to test again in order to prove that it is true. [female, 31 years, urban].

Counselors also turned to themes common among recently HIV-positive individuals to unearth underlying concerns. This included topics on the progression of disease, interpretation of disease symptoms, risk of transmission to loved ones, and conception of persons living with HIV. In one example, a 22-year-old female client was in a steady relationship and had no children. The counselor opened a discussion on safe pregnancy among persons living with HIV. The client then disclosed that she was 2 months pregnant and had been harboring anxiety on future steps. This was particularly salient regarding communication around ART, shifting the discussion from pre-ART care to the urgency and availability of ART.

The clients' active participation and articulation of their subjective values and goals during the foundation building phase appeared to be mediated by (1) the extent to which the client had internalized the meaning of the diagnosis and (2) the extent to which the client had progressed in planning or taking action to meet the desired goals. Acknowledging these dynamics facilitated pacing of sessions to allow clients to lead in their own care engagement processes.

Exploring and Promoting the Value of HIV Clinical Care

The tailoring of communication to client narratives provided an opportunity to (1) engage the client in reflection on the congruency of HIV treatment with their stated goals and (2) promote accessing HIV clinical care as a health-related value in relation to their illness and potential treatment. Additional educational messaging was also often important to cement HIV care as an important goal. Counselors mostly linked the value of HIV clinical care to client concerns over death, relief of symptoms, ability to remain functionally independent, or the ability to conceive. The promotion of value for clinical care was equally important for both clients who had not entered care or recently entered care within the first 90 days of diagnosis. For the latter, counselors compensated for health communication gaps between clients and health care providers such as those illustrated below.

Counselor: So when you got back to the clinic for the second time, did they show you your blood results? …

Client: They just talked amongst themselves [the nurses] and she said, “Here are the results”… So I don't know what they mean [female, 57 years, urban, public health care facility].

Counselor: He gave me the medication and he didn't want to give me the pamphlet that shows the side effects. He said people like complicating things by reading these things [pamphlets] … [female, 31 years, urban, private health care facility].

On the other hand, counselors faced difficulties when clients did not perceive value in HIV clinical care, especially among those who were not eligible for ART or those who had negative experiences from previous clinic visits. In sessions where clients exhibited signs of resistance to HIV clinical care (arguing, in-attention, side-tracking, or cutting off), counselors were trained to “roll with resistance” but often failed to shift focus and reframe the discussion to offer a new meaning or perspective for the client's consideration.

Collaborative Identification of Goal-Oriented Activities

Through open-ended questioning, counselors probed for specific plans to go to a clinic. Where clients failed to identify deficiencies in their plans, counselors used nonjudgmental critical questioning or paradoxical scenarios to challenge the proposed plan. In some cases, this exposed the underlying concerns that had not been communicated by the client.

Counselor: So, you are saying that you will not disclose to him…? How do you plan to take treatment when he is around?

Client: I don't know. It will not be easy because I want to take the treatment. I will also have a problem of having unprotected sex because I haven't told him about my status… I don't know where I'm coming from or going. I am confused…. My partner and I have not been faithful to each other. I have someone else that I am dating and he also has someone else [female, 51 years, rural].

Clients who experienced paternalistic treatment from their HIV clinical care providers appreciated the participatory and collaborative nature of the support provided by the counselors. In the example below, the client chose to seek private over public health care but felt that she was not afforded the opportunity to participate in the decision around starting ART. The counselor provided additional support, with a subsequent resolution to change the care provider.

Client: … He [private doctor] dealt with me as if I have already said yes to one, 2 and 3. He said “You are ready to start”, things like that. At least you had already explained the process which was to be conducted but he didn't tell me anything … When I got there he said “here is your medication, take and drink”… I was not expecting that, I expected to be counseled and be asked if I am ready to be initiated [female, 31 years, urban].

Identification of Barriers to Goal-Oriented Activities

The process of identifying barriers to the successful completion of activities also required the tactful use of questions to maintain mutual dialogue. Through highlighting potential barriers and working to identify approaches around those barriers, messaging was focused toward the client's needs and may have encouraged increased entry into care. In the example below, the elderly client had lived in a rural village that was serviced by a mobile clinic. However, the client had not accessed care from the mobile clinic.

Counselor: I can see that money is real issue for you in planning how you are going to reach the hospital…. What do you think is the way forward?

Client: I'm waiting to find money so that I can go to town. That is all I am waiting for…I don't know when or how I will find it.

Counselor: I understand that your challenge is money. So, is it possible that you go to the mobile clinic when it comes [to this area] next week?

Client: Yes it's possible. I will go because you don't pay you just walk [female, 56 years, rural].

The multiple session approach allowed for continued reflection on barriers, which may have been initially dismissed or not identified by both client and counselor.

Counselor: Since you were not able to complete the task of going to the clinic, let us talk about last week's conversation when you mentioned that you had no hindrances [going to the clinic]. Today do you have any concerns of hindrances that may prevent you going to the clinic?

Client: No, the only challenge I have is time.

Counselor: So, the main challenge you have is time?

Client: Yes that is the only problem. I only have time over the weekends [male, 40 years, urban].

Once barriers had been identified, counselors steered their clients to constructively reframe their perspective on the identified barriers, in terms of how they planned to overcome them.

Counselor: How do you think you can overcome this issue of the long queues and your thoughts of poor services at the clinic?

Client: I can go back, but not when I'm going to school because I don't want to disturb my studies.

Counselor: Oh ok. So you feel that you can overcome this by going to the clinic when you are not going to the school because you will be able to handle the long queues?

Client: Yes, even if I find the queues, I will not be rushing anywhere [female, 20 years, urban].

Some clients who presented themselves as possessing high levels of self-efficacy noted barriers faced by some people but insisted that they did not apply to them. Counselors applied “focusing” techniques to direct conversational flow back to the client. For a 51-year-old male client, the client refocused the session by noting, “Earlier you said that it is important that everything should start with ‘I’ [me] because this is about you ….” After this, it surfaced that behind the displayed levels of self-efficacy, the client had underlying challenges with accepting his status and had resorted to dissociation from the diagnosis as a form of coping.

Drawing Upon Client Strengths

Identification of strengths was conducted to provide clients with a self-awareness of their capacities and strengths to manage their own lives and illness. These internal resources were primarily identified by asking clients to provide narratives about past difficult life experiences and their coping mechanisms to these challenges. This also addressed issues of negative self-evaluation, low self-esteem, and a lack of self-efficacy to engage in HIV care. In the example below, the counselor amplified the client's strengths to increase their motivation toward care engagement.

Counselor: My brother as you were busy talking as I was listening to you. I saw a determined person. I see a person who doesn't lose hope in life. I also see a courageous person, because when you were met with life situations, you never turned back …?

Client: I don't know where it comes from myself [male, 30 years, urban].

Transitioning Out and Discontinuation of Sessions

At this stage, counselors summarized and reflected upon the content of previous sessions, with primary emphasis on the client's resources required to achieve or maintain HIV care engagement. Referrals were also made for 3 clients that required additional counseling, access to food parcels, and assistance with social grant applications.

In turn, clients were also asked to summarize any learning or experiential growth that had occurred during the sessions. Clients identified value in terms of redefining their self-worth, accessing social support, educational messaging, and entering care.

Client: … If I had not talked to you, maybe things have turned out differently. I never thought I would ever get HIV. After having lived a good life, I asked myself “Why me?” Obviously I had to reach this point and accept, but what helped me the most was you talking to me, and helping me realize issues about the disease and myself… I am thankful for things you have done … [female, 31 years, urban].

DISCUSSION

Through exploring specific themes from counseling sessions, we have demonstrated specific ways that IPC enabled a dialogue that could fit the immediate needs, concerns, or challenges of a client. In doing so, the precision health communication was able to provide communication that may have better met the needs of the client and better achieved behavior change. Through IPC, some clients enunciated goals and described challenges that they may not have previously been fully conscious of. In turn, this allowed the counselor to challenge the client to think through specific barriers and articulate solutions. In some of the sessions, the use of IPC may have been the only communication strategy able to bridge the gap from testing to planning on going to a clinic. A failure to lay this foundation may result in irrelevant messages or messages that are highly relevant but may not have penetrated through the client's more immediate concerns. Such off-target messaging—either via mass media or one-on-one—may lead the person living with HIV to tune out and fail to achieve behavior change.15–17

We also note challenges in providing precision health communication. Standard messaging as part of HCT, adherence counseling, and HIV care in South Africa is generally provided as informational outside of specific client context (eg, descriptions of HIV, warnings about the perils of missing doses of ART, instructions to use condoms, etc).18 Delivering precision health communication was not always easy for the counselors who both missed communication opportunities and, at times, reverted to proscriptive general messaging. Although not a common occurrence in this study, other studies have reported major challenges with counselors primarily relying on directing, moralizing, and health advising techniques.15,18 The consequences of such approaches can be client resistance or superficial therapeutic alliances that do not yield results.19 However, other researchers argue that some sub-Saharan African societies and cultures perceive value and favorably defer to paternalistic approaches with resulting positive HIV care engagement outcomes.20–22 Success with implementing precision health communication requires it being embraced by counselors and having ongoing oversight and mentoring to maintain and improve the quality of the counseling.16

This study has the strength of assessing real-world counseling sessions as part of a health communication arm of a trial to accelerate entry into care after testing HIV positive. Limitations include the small number of transcripts analyzed. In addition, we did not assess the proportion of client–counselor communication that led to tailored or precision communication compared with more general information provision. Furthermore, we did not assess whether specific communication sessions appeared more or less likely to lead to entry into care. HIV care seeking, continued engagement in care, and adherence to the treatment are all health behaviors. Health communication has an important role in positively influencing this behavior.23 This communication may take many forms—from mass media, peer support, health care workers providing education and reinforcement, and messages developed through discussion with a client—as we have illustrated here. We believe that such precision health communication has an important role and may contribute to improving the care continuum.

Footnotes

Supported by United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Cooperative Agreement AID-OAA-A-12-00028.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Govindasamy D, Ford N, Kranzer K. Risk factors, barriers and facilitators for linkage to antiretroviral therapy care: a systematic review. AIDS. 2012;26:2059–2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mugglin C, Estill J, Wandeler G, et al. Loss to programme between HIV diagnosis and initiation of antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review and meta-analysis. Trop Med Int Health. 2012;17:1509–1520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharma M, Ying R, Tarr G, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of community and facility-based HIV testing to address linkage to care gaps in sub-Saharan Africa. Nature. 2015;528:S77–S85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muhamadi L, Tumwesigye NM, Kadobera D, et al. A single-blind randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effect of extended counseling on uptake of pre-antiretroviral care in Eastern Uganda. Trials. 2011;12:184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wanyenze RK, Kamya MR, Fatch R, et al. Abbreviated HIV counselling and testing and enhanced referral to care in Uganda: a factorial randomised controlled trial. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1:e137–e145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flickinger TE, Saha S, Moore RD, et al. Higher quality communication and relationships are associated with improved patient engagement in HIV care. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63:362–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Craw JA, Gardner LI, Marks G, et al. Brief strengths-based case management promotes entry into hiv medical care: results antiretroviral treatment access study-ii. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47:597–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Health communication capacity collaborative. Global HIV experts convene to review evidence. 2014. Available at: http://www.healthcommcapacity.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/consult-factsheet11-22.pdf. Accessed May 24, 2016.

- 9.Vermund SH, Van Lith LM, Holtgrave D. Strategic roles for health communication in combination HIV prevention and care programs. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;66(suppl 3):S237–S240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borrell-Carrio F, Suchman AL, Epstein RM. The biopsychosocial model 25 years later: principles, practice, and scientific inquiry. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2:576–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duggan A. Understanding interpersonal communication processes across health contexts: advances in the last decade and challenges for the next decade. J Health Commun. 2006;11:93–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffmann CJ, M T, Ginindza S, Fielding KL, Kubeka G, Dowdy D, Churchyard GJ, Charalambous S. A randomized trial to accelerate HIV care and ART initiation following HIV diagnosis. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Illnesses; February 22-25, 2016; Boston, MA.

- 13.Hoffmann CJ, Mabuto T, McCarthy K, et al. A framework to inform strategies to improve the HIV care continuum in low- and middle-income countries. AIDS Educ Prev. 2016;28:351–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dewing S, Mathews C, Schaay N, et al. “It's important to take your medication everyday okay?” an evaluation of counselling by lay counsellors for ARV adherence support in the Western Cape, South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:203–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dewing S, Mathews C, Schaay N, et al. Improving the counselling skills of lay counsellors in antiretroviral adherence settings: a cluster randomised controlled trial in the Western Cape, South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2015;19:157–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Rooyen H, Rohleder P, Richter L, et al. HIV/AIDS in South Africa 25 years on: psychosocial perspectives. Springer Science and Business Media, New York, NY. 2009.

- 18.Mohlabane N, Peltzer K, Mwisingo A, et al. Quality of HIV counselling in South Africa. J Psychol. 2015;6:19–31. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahrer A, Murphy L, Gagnon R, et al. The counsellor as a cause and cure of client resistance. Can J Counselling Psychotherapy. 1994;28:125–135. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laungani P. Replacing client-centred counselling with culture- centred counselling. Couns Psychol Q. 1997;10:343–351. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wanyenze RK, Musinguzi G, Matovu JK, et al. “If You Tell People That You Had Sex with a Fellow Man, It Is Hard to Be Helped and Treated”: barriers and Opportunities for Increasing Access to HIV Services among Men Who Have Sex with Men in Uganda. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0147714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watt MH, Maman S, Earp JA, et al. “It's all the time in my mind”: facilitators of adherence to antiretroviral therapy in a Tanzanian setting. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68:1793–1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Babalola S, Van Lith LM, Mallalieu EC, et al. A framework for health communication across the HIV treatment continuum. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;74(suppl 1):S5–S14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]