Abstract

Background:

Community empowerment approaches have been found to be effective in responding to HIV among female sex workers (FSWs) in South Asia and Latin America. To date, limited rigorous evaluations of these approaches have been conducted in sub-Saharan Africa.

Methods:

A phase II community randomized controlled trial is being conducted in Iringa, Tanzania, to evaluate the effectiveness of a community empowerment–based combination HIV prevention model (Project Shikamana) among a stratified sample of HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected FSWs. Cohort members were recruited from entertainment venues across 2 communities in the region using time-location sampling. All study participants gave consent, and were surveyed and screened for HIV at baseline. Primary biological study outcomes are viral suppression among the HIV-infected and remaining free of HIV among HIV-uninfected women.

Results:

A cohort of 496 FSWs was established and is currently under follow-up. Baseline HIV prevalence was 40.9% (203/496). Among HIV-infected FSWs, 30.5% (62/203) were previously aware of their HIV status; among those who were aware, 69.4% were on antiretroviral therapy (43/62); and for those on antiretroviral therapy, 69.8% (30/43) were virally suppressed. Factors associated with both HIV infection and viral suppression at baseline included community, age, number of clients, and substance use. Amount of money charged per client and having tested for sexually transmitted infection in the past 6 months were protective for HIV infection. Social cohesion among FSWs was protective for viral suppression.

Conclusions:

Significant gaps exist in HIV service coverage and progress toward reaching the 90-90-90 goals among FSWs in Iringa, Tanzania. Community empowerment approaches hold promise given the high HIV prevalence, limited services and stigma, discrimination, and violence.

Key Words: HIV, female sex workers, viral suppression, community empowerment, combination prevention, Tanzania

INTRODUCTION

The heightened risk of HIV infection among female sex workers (FSWs) has been clearly established across settings.1 In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), FSWs have an estimated HIV prevalence of 36.9% as compared to 7.4% in the general adult female population.2,3 In the Iringa region of Tanzania, a recently integrated biobehavioral surveillance survey found that 32.9% of FSWs were living with HIV.4 Previous formative research conducted in Iringa documented the negative impact of stigma, discrimination, and violence among FSWs.5–7 Such social and structural factors have been shown to inhibit engagement in HIV services among FSWs in SSA8–10 contributing to their disproportionate risk and onward transmission.

Comprehensive, community empowerment–based approaches that address the sociostructural vulnerabilities of FSWs to HIV infection, and ensure equitable access to prevention interventions, have been shown to be effective in South Asia and Latin America.11 We recently conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of community empowerment on HIV outcomes among FSWs that included 22 studies among >30,000 women. We found that community empowerment–based HIV prevention approaches were associated with a 32% reduction in the odds of HIV infection among FSWs [odds ratio (OR): 0.68; 95% CI: 0.52 to 0.89] and a 3-fold increase in consistent condom use with clients (OR: 3.27; 95% CI: 2.32 to 4.62).12 In addition, mathematical modeling suggests that community-led responses to HIV among FSWs which include scaling up equitable access to antiretroviral therapy (ART) for FSWs, can reduce HIV incidence among both FSWs and the general population.13,14 There have been limited efforts to implement and evaluate the effects of community-based combination prevention among FSWs in SSA.

By way of response, we are conducting a phase II trial of a community-based model of combination HIV prevention among FSWs in Iringa, Tanzania. Project Shikamana (Stick Together) includes a package of biomedical, behavioral, and structural intervention elements set within a larger rights-based framework.15 The package has been tailored to the needs of FSWs in this setting based on input from formative research and ongoing consultation with an FSWs’ community advisory board. Elements include (1) community-led peer education, condom distribution, and HIV counseling and testing in entertainment venues; (2) peer navigation to facilitate linkage to and retention in care and ART; (3) sensitivity training for HIV clinical care providers; (4) texts to promote awareness, solidarity, and adherence to care and ART; and (5) a community-led drop-in center for activities to promote social cohesion and community mobilization to address issues such as stigma, discrimination, violence prevention, and financial insecurity.

This study design being used to test the feasibility and initial effectiveness of this model is a community-randomized controlled trial conducted in 2 Iringa communities matched on demographics and HIV risk. The intervention arm is receiving the combination prevention package described above, whereas the control arm is receiving the local standard of care. The Iringa region is characterized by high prevalence of HIV (9% in Iringa vs. 5% in Tanzania overall)16 that is thought to be the product of its location along the TanZam highway, a major trucking route, and large numbers of migrant seasonal workers, both of which create the demand for sex work.17 Consistent with phase II trials, our goals are to establish base rates of key outcomes including viral suppression and HIV incidence among a cohort of HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected FSWs; document intervention feasibility and acceptance; and establish its preliminary effectiveness. This study will be the first assessment of how to strategically tailor18 community-based combination HIV prevention among FSWs in SSA. Here, we present baseline findings from Project Shikamana.

METHODS

Overview

Participants were recruited from entertainment venues, which is the primary modality of sex work in Iringa,4 where sex work is known to occur including modern bars, traditional bars, guesthouses and hotels, groceries/mini-bars/pubs, and clubs in 2 communities matched on size (approximately 25,000 each) and overall HIV prevalence (∼7%). We updated a previous mapping exercise to identify a total of 164 venues across the 2 communities (Ilula and Mafinga). Venues ranged in size in numbers of women working on the premises at any given time, from 1 woman in the context of small local bars to 40 women in larger entertainment venues. We used time-location sampling (TLS) to enroll a cohort that included 203 HIV-infected and 293 HIV-uninfected women. Inclusion criteria included women 18 years and over who reported exchanging sex for money in the last month. Participants were screened for HIV at baseline, surveyed at this same initial visit, and are currently being followed. Viral load (VL) was assessed among all HIV-infected women.

Sampling and Sample Size

TLS entailed identifying days and times when the target population gathered at sex work venues, constructing comprehensive sampling frames of venues and daytime units, then randomly selecting and visiting venues and daytime units, and systematically collecting information from eligible members of the target population during those periods. Recruitment ended when the target of 100 HIV-positive women was reached in each community. The TLS process and baseline recruitment period ran from October 2015 to April 2016. Participants were approached and screened for eligibility in a private place at or near the venue. For HIV-infected participants, we have power to estimate the difference in the proportions virally suppressed between intervention and control communities with a precision of ±0.162 assuming a comparison proportion of 0.50, delta of 0.15, up to 30% loss to follow-up and 95% confidence interval. For the HIV uninfected, we have 95% power to detect a relative risk of 1.2 or greater, assuming that 75% are retained and remain free of HIV after 1 year in the control community.

Data Collection Procedures

Before the survey and blood draw, informed consent was obtained from all study participants. The survey assessed demographic, behavioral, and sociostructural factors such as stigma, social cohesion and gender-based violence (GBV) experience, as well as exposure to and use of HIV programs and services. All consenting participants (including those self-reporting to be HIV positive) were counseled and tested for HIV following Tanzanian national guidelines, using a dual parallel algorithm of the Uni-Gold and Determine rapid HIV-1 antibody tests in the field at the time of the survey, followed by a repeat dual parallel algorithm of these same tests after 2 weeks in the case of discordant results. VL analyses from specimens of all HIV-infected women were performed at the Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences (MUHAS) laboratory in Dar es Salaam, using polymerase chain reaction technology with the Roche Amplicor HIV-1 Monitor Test. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, and MUHAS and the National Institute of Medical Research (NIMR) in Tanzania. Participants were compensated 5000 Tanzanian shillings (Tsh) (US $2.50) for the baseline visit.

Variables and Outcomes

Sociodemographic and behavioral variables measured included participants' age, education, residence, migration (duration of residence in the region), mobility (travel outside region) over the last 6 months, marital status, number of children, number of paying and nonpaying sexual partners during the past month, consistent condom use per each partner type, drug use and alcohol use ever and during the past month, including type, frequency and number of alcoholic drinks, total income per month and percentage of income derived from sex work, and age of initiation, and length of time in sex work. Categories of types of sex work venues were defined based on formative research,5 and women were classified by venue type based on self-report.

Primary study outcomes to be assessed after 1 year are remaining HIV uninfected among participants who are HIV uninfected at baseline, and viral suppression among those who are HIV infected at baseline. We will compare each outcome per arm between baseline and 12-month follow-up. Secondary prevention outcomes include HIV protective behaviors such as consistent condom use with clients and nonpaying sexual partners during the last month. Secondary treatment outcomes include engagement in care, and adherence to ART, assessed using the AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG) measures.19

Aggregate Measures

Aggregate measures include sex work stigma and social cohesion. Sex work stigma (α = 0.86) was assessed with a 13-item 4-point Likert scale. This stigma measure was developed based on previous work on HIV stigma (Berger,20 Zelaya21), and was modified to reflect perceptions and experiences related to sex work stigma. This adapted measure was validated by our team among FSWs in the Dominican Republic.22 Social cohesion (α = 0.77) was assessed using a reliable 9-item aggregate measure originally developed by the first author among FSWs in Brazil and later validated among FSWs in Swaziland.23,24 Participants rated their agreement on a 4-point Likert scale with statements related to mutual aid, support, and trust among their FSW colleagues. GBV experiences were assessed using measures adapted from the World Health Organization and Decker et al.25 The assessment consisted of a series of yes/no questions regarding whether physical violence or sexual violence had been perpetrated by clients, nonclients, and others such as police officers. These questions were later categorized into having experienced any of these events across perpetrators, ever and in the last 6 months.

We also explored intervention and service exposure and uptake including HIV testing, treatment and care, peer education, condom access, and participation in community mobilization.

Data Analysis

The data were checked using descriptive statistics methods. For stigma and social cohesion scales, we calculated the average score over all items in the scale and multiplied by the total number of items. The HIV status outcome was based on the results of the rapid HIV test performed at study enrollment for each participant. The viral suppression outcome included only women who reported their positive status because this is the group that could potentially be on ART. Viral suppression was defined as a VL value ≤400 copies per milliliter or undetectable. Univariate and multivariate associations with each outcome were assessed using logistic regression models with robust variance estimation taking into account possible intraclass clustering by venue. All factors with a P value ≤0.3 were included in initial models, and backward selection was used to produce final multivariate models.

RESULTS

Demographic Characteristics

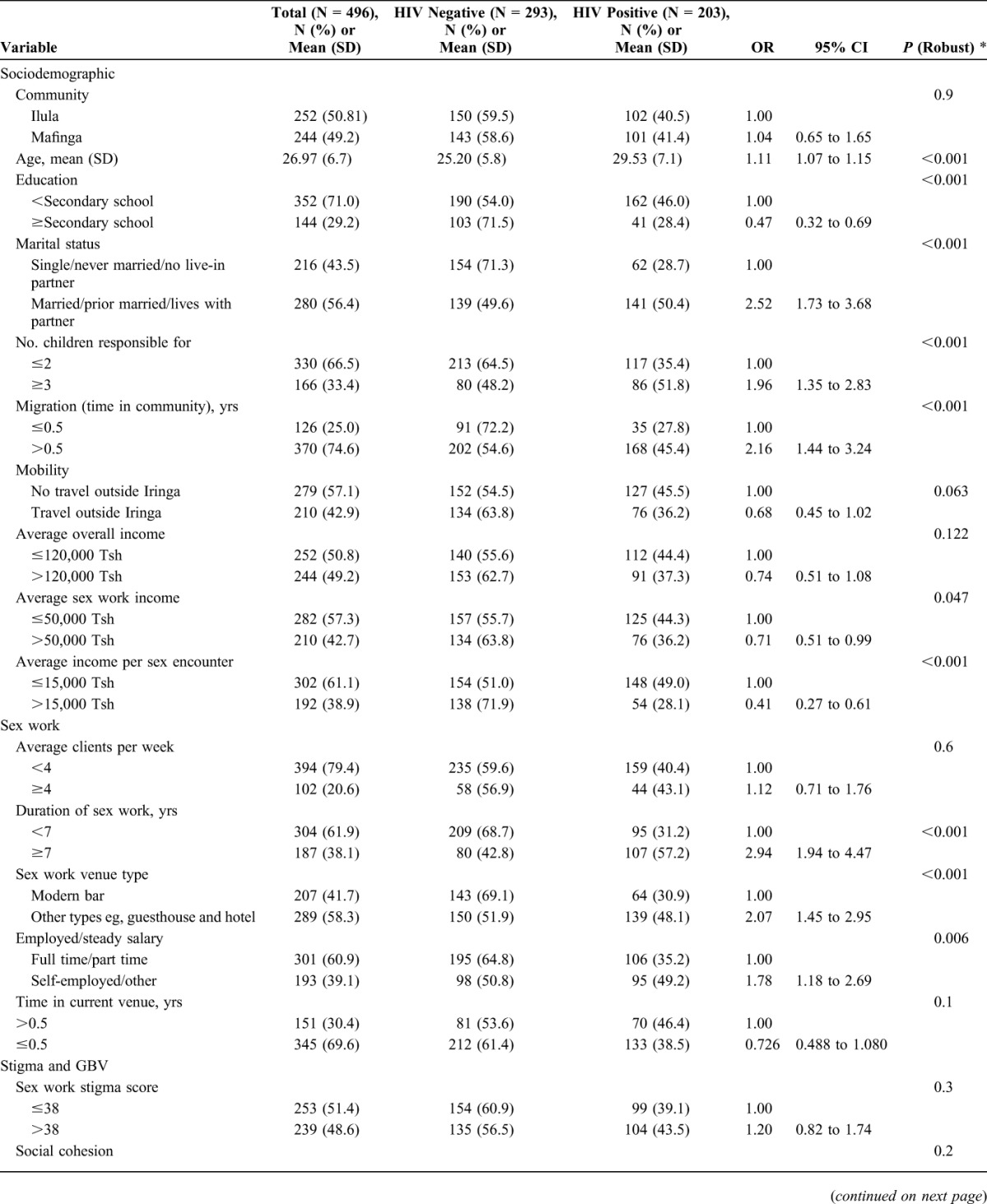

As shown in Table 1, the median age of women in the Shikamana cohort was 27 years (SD 6.7). Most participants (71.0%) reported not having attended any secondary school. Slightly over half of them (56.5%) had been married, or were married, or were living with a partner. Almost all (83.8%) had at least 1 child that they were financially responsible for supporting. The majority (74.6%) lived and worked in the Iringa region for at least 6 months before recruitment, yet mobility was prevalent, with 42.9% having traveled outside Iringa during the past 6 months. Most (69.6%) women had spent less than 6 months working in the venue from where they were recruited. Median overall monthly income was 120,000 Tsh (US$ 55), with approximately half of the participants' monthly income coming from sex work (US$ 23). The median length of time engaged in sex work among participants was 5.0 years, with a median number of 2.0 clients per week. Most reported charging less than 15,000 Tsh (US$ 7) per sexual encounter with a client. Regarding types of venues, 41.7% worked in “modern bars,” with the rest in “traditional bars,” guesthouses, and hotels. Most participants (60.9%) reported earning income from either full- or part-time employment at the establishment itself, eg, being paid for working as a barmaid, in addition to money made from sex work.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Shikamana Cohort Characteristics and Factors Associated With HIV Status at Baseline (n = 496)

Sociostructural and Behavioral Factors

Stigma, discrimination, and violence were prevalent. For example, nearly half (48.6%) of our cohort had experienced at least 1 form of stigma associated with being an FSW. The median level of reported sex work stigma was 39 (18–52 range) at baseline. Half had ever experienced either physical or sexual GBV (50.8%). Substance use was also common, including in the venue (71.2%) and during sex work transactions (42.0%). Most of this was alcohol use with 49.2% reporting drinking on 4 or more days per week. Only 6.9% reported any previous illicit drug use and 3.0% in the last 6 months. Despite a high baseline prevalence of HIV (40.9%), less than half of the women reported consistent (past month) condom use, with 40.4% reporting consistently using condoms with new clients, 34.3% with regular clients, and 21.1% with nonpaying steady partners. For access to interventions and services, 12% reported having had contact with a peer educator who provided HIV prevention education or facilitated access to services. Approximately one-quarter (26.6%) reported having been tested for sexually transmitted infection (STI) (beyond HIV) in the last 6 months. The median level of reported social cohesion or perceived sense of solidarity and mutual aid with other FSWs with whom they worked was 21.0 (9–35 range) at baseline.

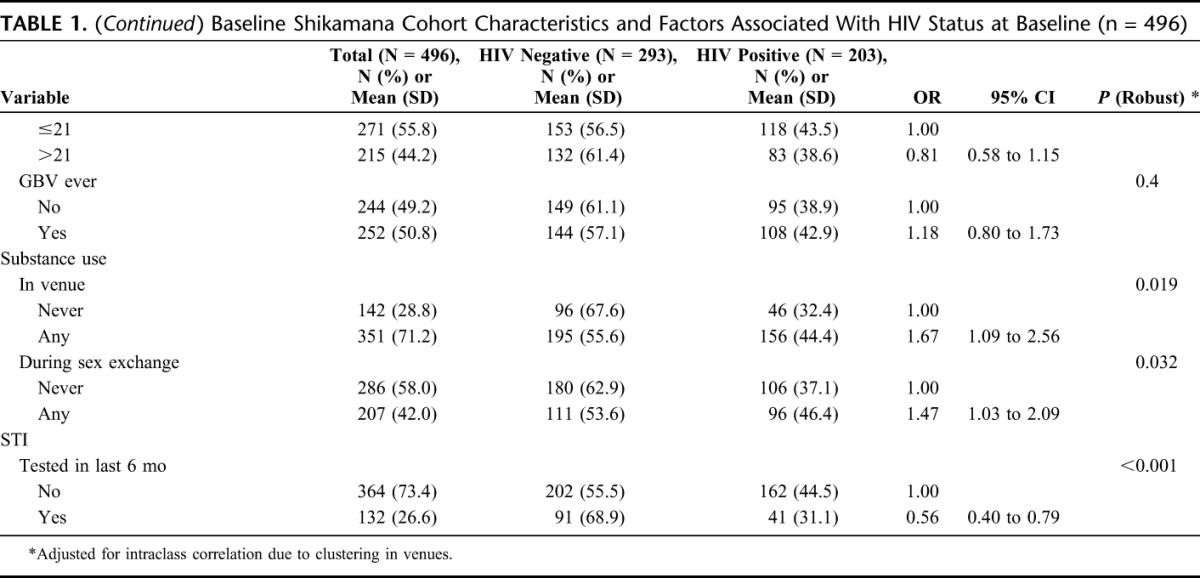

HIV Care and Treatment Dynamics: Reaching the 90-90-90s

As seen in Figure 1, there was a significant difference between the 90-90-90 goals26 and the experiences of FSWs participating in the Shikamana cohort. The majority reported having had a previous HIV test (92%), with almost half (47.7%) having been tested in the last 6 months. However, among those 40.9% who tested positive at baseline (203/496), only 30.5% (62/203) were previously aware of their HIV status. Among those who were aware of their HIV status, 69.4% self-reported being on ART (43/62). Of those aware of their status, 48.4% (30/62) were virally suppressed with 30/43 (69.8%) among those who reported currently being on ART. Self-reported adherence to ART was suboptimal, with 56.4% (35) reporting perfect adherence in the last 4 days. In duration of infection, 43.5% reported having been diagnosed with HIV <2 years ago.

FIGURE 1.

Comparison with the “90-90-90” targets among the Shikamana cohort at baseline. Definitions: known HIV status out of those testing positive; currently receiving ART among those aware of positive status; and VL <400 copies per milliliter among those currently on ART.

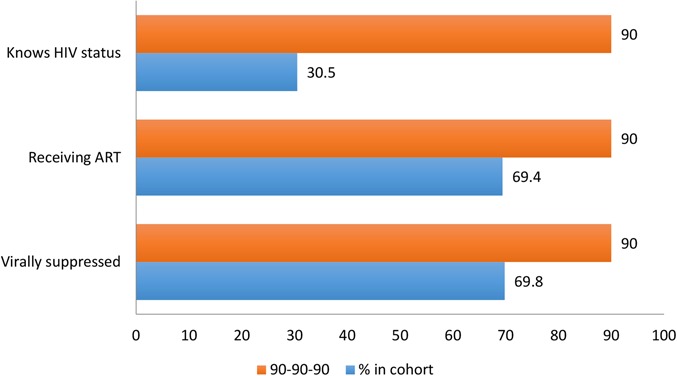

Factors Associated With HIV Status

As seen in Table 2, a number of factors were found to be associated with HIV infection in univariate analyses, including older age, lower education, being married or living with a partner, 3 or more children that the woman is responsible for, lower mobility (not traveling outside the region over the past 6 months) and lesser migration (living in the community for over 6 months), lower income (overall and from sex work), 7 or more years in sex work, not being employed by the venue, working in a traditional type of establishment (eg, guesthouse or hotel), substance use in the venues and during sex work (alcohol or drugs), and not being tested for STI in the last 6 months. In multivariate analyses, variables that remained significant included community, older age, lesser migration, being married or living with a partner, lower income charged per sex work encounter, higher average number of clients, substance use, and not having previous STI testing. Specifically, we found that women from Mafinga had a 1.69 higher adjusted odds of being HIV infected (95% CI: 1.05 to 2.72). Older FSWs had higher odds of HIV infection per year of age (OR 1.08; 1.04 to 1.12), as did those who had been in the Iringa region for more than 6 months (OR 1.62; 1.04 to 2.50). FSWs who were married, or had been married, or had a live-in partner, had a marginally significant higher risk of HIV (OR 1.53; 0.99 to 2.35), as did those with 4 or more clients per week (OR 1.55; 0.94 to 2.53). A greater amount of money (in the upper tertile) charged per sexual encounter with clients was protective in relation to HIV status (OR 0.56; 0.33 to 0.96), as was having tested for other STIs in the past 6 months (OR 0.61; 0.42 to 0.88).

TABLE 2.

Multivariate Model for Factors Associated With HIV Status at Baseline (N = 491)

Factors Associated With Viral Suppression

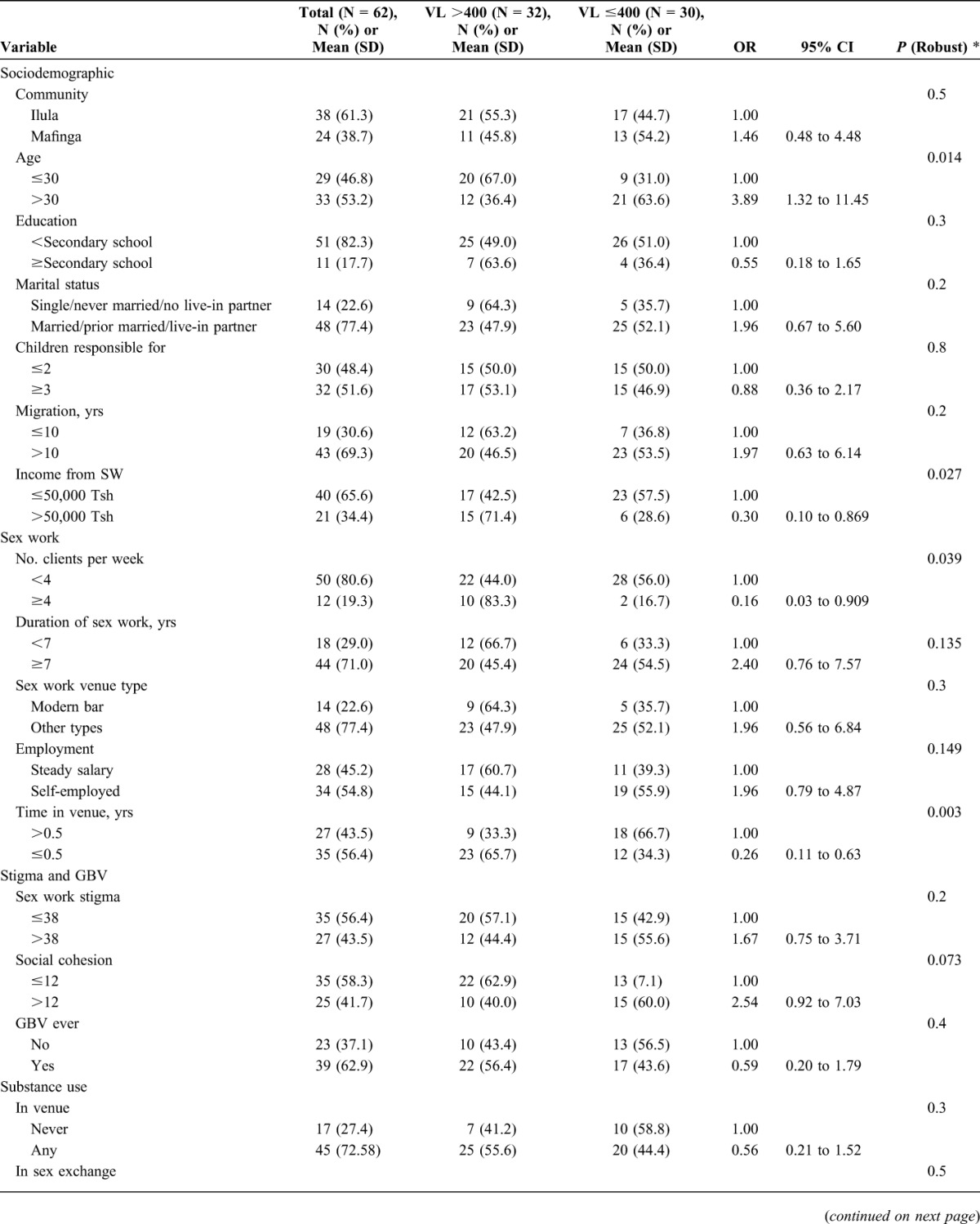

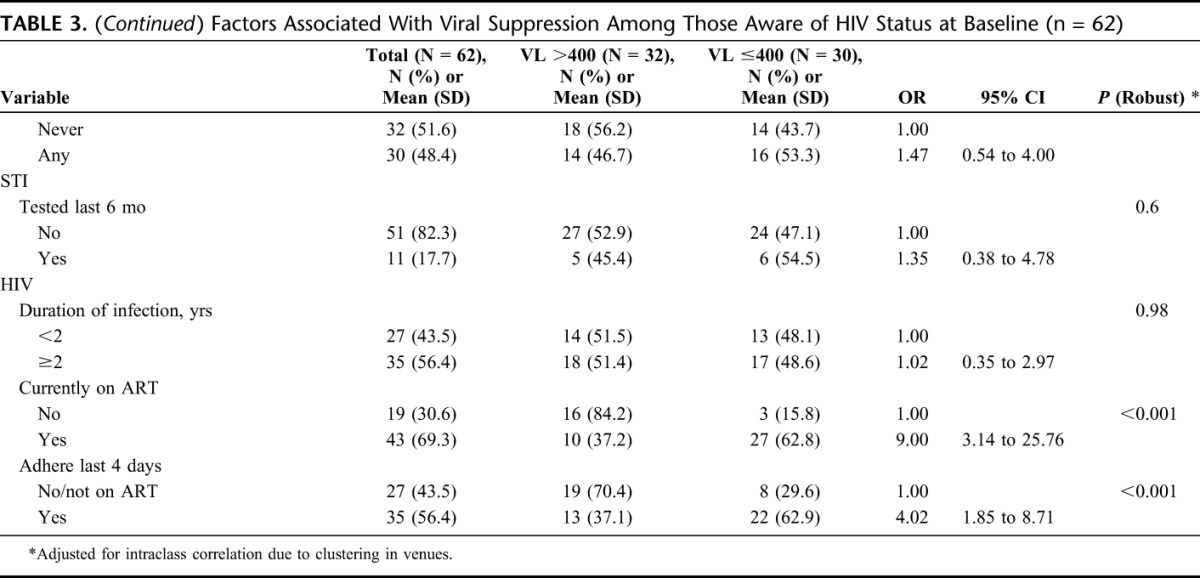

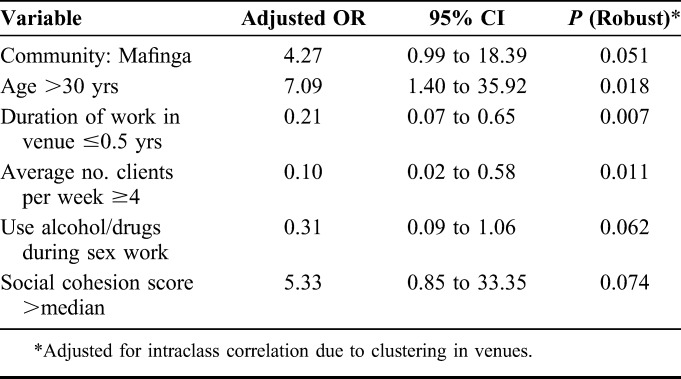

Univariate analyses for viral suppression among women aware of being HIV infected at baseline also revealed a number of significant demographic and sociobehavioral factors, including older age, smaller income from sex work, lower number of clients per week, being self-employed, and with a higher social cohesion among FSW colleagues (Table 3). Self-reported use of ART and adherence in the last 4 days were both strongly associated with viral suppression. These 2 treatment variables were not included in the multivariate model because these are necessary intermediate steps for viral suppression and would overwhelm the effect of other variables. In multivariate analyses (Table 4), significant variables included community (OR 4.27; 0.99 to 18.39), age (>30) (OR 7.09) (95% CI: 1.40 to 35.92), shorter duration of time working at venue (OR 0.21; 95% CI: 0.07 to 0.65), higher number of clients per week (OR 0.10; 95% CI: 0.02 to 0.58), substance use during sex work (OR 0.31; 95% CI: 0.09 to 1.06), and social cohesion (OR 5.33; 95% CI: 0.85 to 33.35).

TABLE 3.

Factors Associated With Viral Suppression Among Those Aware of HIV Status at Baseline (n = 62)

TABLE 4.

Multivariate Model for Factors Associated With Viral Suppression at Baseline (n = 62)

DISCUSSION

Project Shikamana is one of the first initiatives to implement and evaluate a community empowerment–based approach to combination HIV prevention among FSWs in SSA. At baseline, major gaps in access to HIV services and progress toward the 90-90-90 goals were identified.27 Less than one-third of HIV-infected women enrolled were previously aware of their status, highlighting the need for intensified HIV counseling and testing services that are acceptable and accessible to this population, such as the venue-based HIV counseling and testing now offered in our study. The percentage of FSWs who had accessed ART and were virally suppressed also demonstrate gaps in access to care and treatment. Peer navigation is another element of our intervention whereby FSW leaders work to link and retain FSWs living with HIV into care and onto ART. These efforts promote peer-led health communication and social support which have been effective in facilitating treatment-seeking behaviors in other settings,28 including among FSWs in the Abriendo Puertas (Opening Doors) project in the Dominican Republic.11

Multivariate analysis of baseline data demonstrated several key factors that were associated with both HIV infection and viral suppression including community, age, employment dynamics, and substance use. After adjustment for important confounders, FSWs from Mafinga were found to be more likely to be infected with HIV and, in the case of those who were aware of their HIV-positive status, virally suppressed. Older age was also associated with greater HIV prevalence and greater viral suppression. Alcohol and/or drug use during sex work was negatively associated with both HIV infection and viral suppression. Employment dynamics, including number of clients per week, was negatively associated with both HIV status and viral suppression although greater income charged per client was protective for HIV status, and length of time working in the venue was significantly associated with viral suppression. We also found that having tested for STI was significantly associated with not being HIV infected at baseline, although greater social cohesion was borderline significantly associated with viral suppression.

Although the 2 communities were matched on size and overall HIV prevalence and had similar baseline HIV prevalence among FSWs, community did affect HIV status and viral suppression. Preliminary field reports suggest that differential access to services may be a key factor underlying this finding. Indeed, integrating screening and treatment for other STIs may have a valuable impact given that recent STI testing (past 6 months) was significantly protective for HIV infection in our research. Previous research among FSWs in Tanzania and other settings have shown similar findings.29

Factors found to be associated with HIV status and VL illuminate structural issues for consideration in the implementation and scale-up of community-based combination HIV prevention models for FSWs in this setting and beyond. We found that substance use, particularly alcohol use, in the context of sex work venues and exchange, is highly relevant to prevention and treatment of HIV and care outcomes. We are currently conducting qualitative research to better understand the social context of alcohol use in sex work venues in this setting. In previous formative work, we found many FSWs understood, possibly from providers, that they could not take ART on a day when they had been drinking.30 Addressing misinformation through ongoing dialog and communication between FSWs and providers on the role of alcohol use in ART adherence has been integrated with our ongoing sensitivity training for clinicians serving FSWs living with HIV.

Lastly, the finding that social cohesion was positively related to viral suppression is also important to highlight. The number of women who knew their HIV status at baseline was small, potentially limiting our ability to detect a stronger statistical relationship between social cohesion and viral suppression. Previous work, including in other SSA countries,31 has demonstrated the critical32 importance of social cohesion as a component of community empowerment–based HIV prevention approaches among FSWs,12 and found significant associations with HIV status. Limited work, however, has been conducted on how social cohesion and community empowerment approaches can target HIV care and treatment outcomes that are critical to both the health and human rights of FSWs and curbing ongoing transmission.33 Because we continue to promote, facilitate, and support opportunities for solidarity and mobilization among FSWs in Iringa, we will be looking closely at how these factors influence the impact of intervention over time.

The analysis presented here has several limitations. As a baseline analysis of a larger trial, the findings are cross-sectional in nature and inferences of causality are not possible. In addition, several of the treatment outcomes rely on self-reported behaviors including awareness of HIV status and engagement in and adherence to ART. However, triangulation of findings with both biological outcomes such as viral suppression, and sociostructural factors such as stigma, discrimination, and violence, strengthens the current characterization of what has been a previously understudied population, FSWs living with HIV, in SSA.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would would like to extend our sincere thanks to the study participants, the community and study advisory boards of Project Shikamana, MUHAS staff, peer navigators, HIV providers, Justin Beckham, Lauren Barnet and Dr. Said Aboud.

Footnotes

Supported by the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health through R01MH104044 and facilitated by the infrastructure and resources of the Johns Hopkins University Center for AIDS Research, a U.S. NIH-funded program (1P30AI094189), supported by the following NIH Institutes and Centers: NIAID, NCI, NICHD, NHLBI, NIDA, NIMH, NIA, FIC, NIGMS, NIDDK, and OAR. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Aspects of the data presented in this paper were presented at the 21st International AIDS Society (IAS) meeting, in July 21, 2016, in Durban, South Africa.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kerrigan D, Kennedy C, Morgan T, et al. Female, male and transgender sex workers, epidemiology of HIV/AIDS. Encylopedia of AIDS 2015:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kerrigan D, Wirtz A, Baral S, et al. The Global HIV Epidemics Among Sex Workers. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baral S, Beyrer C, Muessig K, et al. Burden of HIV among female sex workers in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:538–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tanzania National AIDS Control Program, PSI Tanzania. HIV Biological and Behavioral Surveys: Tanzania 2013. Female Sex Workers in Seven Regions. Dar es Salaam, Iringa, Mbeya, Mwanza, Tabora, Shinyanga and Mara: United Republic of Tanzania, Ministry of Health and Social Welfare, National AIDS Control Programme; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beckham S, Kennedy C, Brahmbhatt H, et al. Strategic Assessment to Define a Comprehensive Response to HIV in Iringa, Tanzania. Research Brief. Baltimore, MD: Female Sex Workers; USAID Project Search; Research to Prevention: 2013. Available at: http://www.jhsph.edu/research/centers-and-institutes/research-to-prevention/publications-resources/iringa-briefs.html. Accessed January 10, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beckham SW, Shembilu CR, Winch PJ, et al. Female sex workers' experiences with intended pregnancy and antenatal care services in southern Tanzania. Stud Fam Plann. 2015;46:55–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beckham SW, Shembilu CR, Winch PJ, et al. “If you have children, you have responsibilities”: Motherhood, sex work, and HIV in southern Tanzania. Cult Health Sex. 2015;17:165–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adu-Oppong A, Grimes RM, Ross MW, et al. Social and behavioral determinants of consistent condom use among female commercial sex workers in Ghana. AIDS Education Prev. 2007;19:160–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell C, M Z. Grassroots participation, peer education, and HIV prevention by sex workers in South Africa. Am J Public Health 2001;91:1978–1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scorgie FND, Harper E, et al. “We are despised in the hospitals”: sex workers' experiences of accessing health care in four African countries. Cult Health Sex. 2013;15:450–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kerrigan D, Barrington C, Donastorg Y, et al. Abriendo Puertas: feasibility and effectiveness a multi-level intervention to improve HIV outcomes among female sex workers living with HIV in the Dominican Republic. AIDS Behav. 2016;20:1919–1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kerrigan D, Kennedy CE, Morgan-Thomas R, et al. A community empowerment approach to the HIV response among sex workers: effectiveness, challenges, and considerations for implementation and scale-up. Lancet. 2015;385:172–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wirtz AL, Pretorius C, Beyrer C, et al. Epidemic impacts of a community empowerment intervention for HIV prevention among female sex workers in generalized and concentrated epidemics. PLoS One. 2014;9:e88047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shannon K, Strathdee SA, Goldenberg SM, et al. Global epidemiology of HIV among female sex workers: Influence of structural determinants. Lancet. 2015;385:55–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.WHO UNFPA, UNAIDS Global. Implementing comprehensive HIV/STI programmes with sex workers: practical approaches from collaborative interventions. In: Network of Sex Work Projects. Geneva: The World Bank; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tanzania Commission for AIDS (TACAIDS), Zanzibar AIDS Commission (ZAC), National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), Office of Chief Government Statistician (OCGS), ICF International. Tanzania HIV/AIDS and Malaria Indicator Survey 2011–2012. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: United Republic of Tanzania, Ministry of Health and Social Welfare, National AIDS Control Programme; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17.USAID Project Search. Strategic assessment to define a comprehensive response to HIV in Iringa, Tanzania. In: Research Brief: Summary of Findings. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18.UNAIDS. Combination HIV Prevention: Tailoring and Coordinating Biomedical, Behavioural and Structural Strategies to Reduce New HIV Infections. Geneva, Switzerland: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chesney MA. Factors affecting adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:S171–S176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berger BE, Ferrans CE, Lashley FR. Measuring stigma in people with HIV: psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Res Nurs Health. 2001;24:518–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zelaya CE, Sivaram S, Johnson SC, et al. Measurement of self, experienced, and perceived HIV/AIDS stigma using parallel scales in Chennai, India. AIDS Care. 2012;24:846–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zulliger R, Maulsby C, Barrington C, et al. Retention in HIV care among female sex workers in the Dominican Republic: Implications for research, policy and programming. AIDS Behav. 2015;19:715–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lippman SA, Donini A, Diaz J, et al. Social-environmental factors and protective sexual behavior among sex workers: the Encontros intervention in Brazil. Am J Public Health 2010;100(suppl 1):S216–S223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kerrigan D, Telles P, Torres H, et al. Community development and HIV/STI-related vulnerability among female sex workers in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Health Education Res. 2008;23:137–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Decker MR, McCauley HL, Phuengsamran D, et al. Violence victimisation, sexual risk and sexually transmitted infection symptoms among female sex workers in Thailand. Sex Transm Infect. 2010;86:236–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.UNAIDS. 90-90-90 an Ambitious Treatment Target to Help End the AIDS Epidemic. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 27.UNAIDS. 90-90-90. An ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. Geneva, Switzerland: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Babalola S, Van Lith LM, Mallalieu EC, et al. A framework for health communication across the HIV treatment continuum. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;74(suppl 1):S5–S14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Riedner G, Rusizoka M, Hoffmann O, et al. Baseline survey of sexually transmitted infections in a cohort of female bar workers in Mbeya Region, Tanzania. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79:382–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.USAID Project Search. Multi-level factors affecting entry into and engagement in care the HIV continuum of care in Iringa. In: Tanzania, Baltimore: Final Report; 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fonner VA, Kerrigan D, Mnisi Z, et al. S B. Social cohesion, social participation, and HIV related risk among female sex workers in Swaziland. PLoS One. 2014;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beyrer C, Crago AL, Bekker LG, et al. An action agenda for HIV and sex workers. Lancet. 2015;385:287–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lippman SA, Chinaglia M, Donini AA, et al. Findings from Encontros: a multilevel STI/HIV intervention to increase condom use, reduce STI, and change the social environment among sex workers in Brazil. Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39:209–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]