Abstract

Setaria viridis is a C4 grass used as a model for bioenergy feedstocks. The elongating internodes in developing S. viridis stems grow from an intercalary meristem at the base, and progress acropetally toward fully expanded cells that store sugar. During stem development and maturation, water flow is a driver of cell expansion and sugar delivery. As aquaporin proteins are implicated in regulating water flow, we analyzed elongating and mature internode transcriptomes to identify putative aquaporin encoding genes that had particularly high transcript levels during the distinct stages of internode cell expansion and maturation. We observed that SvPIP2;1 was highly expressed in internode regions undergoing cell expansion, and SvNIP2;2 was highly expressed in mature sugar accumulating regions. Gene co-expression analysis revealed SvNIP2;2 expression was highly correlated with the expression of five putative sugar transporters expressed in the S. viridis internode. To explore the function of the proteins encoded by SvPIP2;1 and SvNIP2;2, we expressed them in Xenopus laevis oocytes and tested their permeability to water. SvPIP2;1 and SvNIP2;2 functioned as water channels in X. laevis oocytes and their permeability was gated by pH. Our results indicate that SvPIP2;1 may function as a water channel in developing stems undergoing cell expansion and SvNIP2;2 is a candidate for retrieving water and possibly a yet to be determined solute from mature internodes. Future research will investigate whether changing the function of these proteins influences stem growth and sugar yield in S. viridis.

Keywords: aquaporin, stem, water transport, sugar accumulation, grasses

Introduction

The panicoid grasses sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum), sorghum (Sorghum bicolor), switchgrass (Panicum virgatum), and miscanthus (Miscanthus X giganteum) provide the majority of soluble sugars and lignocellulosic biomass used for food and biofuel production worldwide (Somerville et al., 2010; Waclawovsky et al., 2010). A closely related grass with a smaller genome, Setaria viridis, is used as a model for these crops in photosynthesis research and for the study of biomass generation and sugar accumulation (Li and Brutnell, 2011; Bennetzen et al., 2012; Brutnell et al., 2015; Martin et al., 2016). The mechanisms that regulate cell expansion and photoassimilate delivery in the stems of these grasses are of interest because they influence the yields of soluble sugars and cell wall biomass produced (Byrt et al., 2011).

Grass stems have repeating units consisting of an internode positioned between two nodes that grow from intercalary meristems at the base; sugar, primarily sucrose, accumulates and is stored in mature cells at the top of the internode (Grof et al., 2013). Along this developmental gradient there is also a transition from synthesis and deposition of primary cell walls through to establishment of thicker secondary cell walls. Sucrose that is not used for growth and maintenance is primarily accumulated intracellularly in the vacuoles of storage parenchyma cells that surround the vasculature (Glasziou and Gayler, 1972; Hoffmann-Thoma et al., 1996; Rae et al., 2005) or in the apoplasm (Tarpley et al., 2007). The mature stems of grasses such as sugarcane can accumulate up to 1M sucrose, with up to 428 mM sucrose stored in the apoplasm (Hawker, 1985; Welbaum and Meinzer, 1990). In addition to a high capacity for soluble sugar storage, carbohydrates are also stored in cell walls of stem parenchyma cells (Botha and Black, 2000; Ermawar et al., 2015; Byrt et al., 2016a).

Historically, increases in sugar yields in the stems of panicoid grasses have been achieved by increasing sugar concentration in stem cells without increasing plant size (McCormick et al., 2009). Sugarcane and sorghum stem sugar content has been increased by years of selecting varieties with the highest culm sucrose content, but these gains have begun to plateau (Grof and Campbell, 2001; Pfeiffer et al., 2010). It may be that we are approaching a physiological ceiling that limits the potential maximum sucrose concentration in the stems of these grasses. Increasing the size of grass stems as a sink may be an effective strategy to increase stem biomass and the potential for greater soluble sugar yield as a relationship exists between stem size and capacity to import and accumulate photoassimilates (sink strength) as soluble sugars or cell wall carbohydrates. Hence, improved stem sugar yields have also been achieved in some sorghum hybrids by expanding stem volume through increased plant height and stem diameter (Pfeiffer et al., 2010; Slewinski, 2012).

In elongating stems, water and dissolved photoassimilates are imported from the phloem into the stem by bulk-flow, or translocation, to drive cell expansion or otherwise be used for growth, development and storage (Schmalstig and Cosgrove, 1990; Wood et al., 1994). In non-expanding storage sinks, water delivering sucrose is likely to be effluxed to the apoplasm and then recycled into the xylem transportation stream to be exported to other tissues (Lang and Thorpe, 1989; Lang, 1990). In addition to vacuolar accumulation of sugars delivered for storage, sugars may also accumulate in the apoplasm with apoplasmic barriers preventing leakage back into the vasculature (Moore, 1995; Patrick, 1997).

The flow of water from the phloem into growth and storage sinks involves the diffusion of water across plant cell membranes facilitated by aquaporins (Kaldenhoff and Fischer, 2006; Zhang et al., 2007). Aquaporins are a highly conserved family of transmembrane channel proteins that enable plants to rapidly and reversibly alter their membrane water permeability or permeability to other solutes depending on the isoform. In maize (Zea mays) and rice (Oryza sativa) genomes 30–70 aquaporin homologs have been identified, respectively (Chaumont et al., 2001; Sakurai et al., 2005). These large numbers of isoforms can be divided into five sub-families by sequence homology; plasma membrane intrinsic proteins (PIPs), tonoplast intrinsic proteins (TIPs), nodulin-like intrinsic proteins (NIPs), and small basic intrinsic proteins (SIPs; Johanson and Gustavsson, 2002). In dicotyledonous plants but not monocotyledonous plants there is also a group referred to as X intrinsic proteins (XIPs; Danielson and Johanson, 2008).

As aquaporins have important roles in controlling water potential, they are prospective targets for manipulating stem biomass and sugar yields (Maurel, 1997). The crucial role of aquaporins in water delivery to expanding tissues and water recycling in mature tissues is indicated by their high expression in these regions (Barrieu et al., 1998; Chaumont et al., 1998; Wei et al., 2007). Here, we explore the transcriptional regulation of aquaporins in meristematic, expanding, transitional and mature S. viridis internodal tissues to identify candidate water channels involved in cell expansion and water recycling after sugar delivery in mature internode tissues.

Materials and Methods

Phylogenetic Tree

Setaria viridis aquaporins were identified from S. italica (Azad et al., 2016), Arabidopsis (Johanson et al., 2001), rice (Sakurai et al., 2005), barley (Hove et al., 2015) and maize (Chaumont et al., 2001) aquaporins, and predicted S. viridis aquaporins from transcriptomic data (Martin et al., 2016) (Supplementary Table S1) using the online HMMER tool phmmer (Finn et al., 20151). Protein sequences used to generate the phylogenetic tree were obtained for S. viridis and Z. mays from Phytozome 11.0.5 (S. viridis v1.1, DOE-JGI2; last accessed July 19, 2016) (Supplementary Table S2). The phylogenetic tree was generated using the neighbor-joining method in the Geneious Tree Builder program (Geneious 9.0.2).

Elongating Internode Transcriptome Analysis and Aquaporin Candidate Selection

Expression data on identified S. viridis aquaporins was obtained from a transcriptome generated from S. viridis internode tissue (Martin et al., 2016). Protein sequences of selected putative aquaporin candidates expressed in the elongating S. viridis transcriptome were analyzed by HMMscan (Finn et al., 20151).

Plant Growth Conditions

Seeds of S. viridis (Accession-10; A10) were grown in 2 L pots, two plants per pot, in a soil mixture that contained one part coarse river sand, one part perlite, and one part coir peat. The temperatures in the glasshouse, located at the University of Newcastle (Callaghan, NSW, Australia) were 28°C during the day (16 h) and 20°C during the night (8 h). The photoperiod was artificially extended from 5 to 8 am and from 3 to 9 pm by illumination with 400 W metal halide lamps suspended ∼40 cm above the plant canopy. Water levels in pots were maintained with an automatic irrigation system that delivered water to each pot for 2 min once a day. Osmocote® exact slow release fertilizer (Scotts Australia Pty Ltd, Sydney, NSW, Australia) was applied at 20 g per pot, 2 weeks post-germination. Additional fertilization was applied using Wuxal® liquid foliar nutrient and Wuxal® calcium foliar nutrient (AgNova Technologies, Box Hill North, VIC, Australia) alternately each week.

Harvesting Plant Tissues, RNA Extraction, and cDNA Library Synthesis

Harvesting of plant material from a developing internode followed Martin et al. (2016). Total RNA was isolated from plant material ground with mortar and pestle cooled with liquid nitrogen, using Trizol® Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Scoresby, VIC, Australia) as per manufacturer’s instruction. Genomic DNA was removed using an Ambion TURBO DNase Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was synthesized from 230 ng of isolated RNA from the cell expansion, transitional, and maturing developmental zones as described in Martin et al. (2016) using the Superscript III cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with an oligo d(T) primer and an extension temperature of 50°C as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Reverse-Transcriptase Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

Reverse-transcriptase-qPCR was performed using a Rotor-Gene Q (QIAGEN, Venlo, Netherlands) and GoTaq® Green Master Mix 2x (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). A two-step cycling program was used following the manufacturer’s instructions. The green channel was used for data acquisition. Gene expression of the candidate genes was measured as relative to the housekeeper S. viridis PP2A (SvPP2A; accession no.: Sevir.2G128000). The PP2A gene was selected as a housekeeper gene because it is established as a robust reference gene in many plant species (Czechowski et al., 2005; Klie and Debener, 2011; Bennetzen et al., 2012) and it was consistently expressed across the developmental internode gradient in the transcriptome and cDNA libraries (Martin et al., 2016; Supplementary Figure S1). The forward (F) and reverse (R) primers used for RT-qPCR for were: SvPIP2;1-F (5′-CTCTACATCGTGGCGCAGT-3′) and SvPIP2;1-R (5′–ACGAAGGTGCCGATGATCT-3′), and SvNIP2;2-F (5′–AGTTCACGGGAGCGATGT- 3′) and SvNIP2;2-R (5′–CTAACCCGGCCAACTCAC-3′). SvPIP2;1 and SvNIP2;2 primer sets amplified 161 and 195 base pair fragments from the CDS, respectively. SvPP2A primer set sequences were SvPP2A-F (5′–GGCAACAAGAAGCTCACTCC-3′) and SvPP2A-R (5′-TTGCACATCAATGGAATCGT-3′) and amplified a 164 base pair fragment from the 3′UTR.

Gene Co-expression Network Analysis

Raw FPKM values of putative aquaporins and sugar transporters were extracted from the S. viridis elongating internode transcriptome (Martin et al., 2016). Putative S. viridis sugar transporters from the Sucrose Transporter (SUT), Sugar Will Eventually be Exported Transporter (SWEET), and Tonoplast Monosaccharide Transporter (TMT) families were identified by homology to rice SUT, SWEET, and TMT genes (Supplementary Table S3; Supplementary Figures S2–S4). FPKM values were normalized by Log2 transformation and Pearson’s correlation coefficients calculated by Metscape (Karnovsky et al., 2012). A gene network was generated for Pearson’s correlation coefficients between 0.8 and 1.0 and visualized with the Metscape app in Cytoscape v3.4.0. Significance of Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated using SPSS (IBM Corp. Released 2013. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY, USA) (Supplementary Table S4). The 1.5Kb 5′ promoter region, directly upstream of the transcriptional start site, of the two aquaporin candidates and the highly correlated putative sugar transporter genes were screened for the presence of cis-acting regulatory elements registered through the PlantCARE online database (Lescot et al., 20023) and cis-acting elements of Arabidopsis and rice SUT genes reported by Ibraheem et al. (2010).

Photometric Swelling Assay

Extracted consensus coding sequences for SvPIP2;1 and SvNIP2;2, from S. viridis transcriptome data (Martin et al., 2016), were synthesized commercially by GenScript (Piscataway, NJ, USA). SvPIP2;1 and SvNIP2;2 cDNA fragments were inserted into a gateway enabled pGEMHE vector. pGEMHE constructs were linearized using NheI (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) and purified using the MinElute PCR Purification Kit (QIAGEN). Complimentary RNA (cRNA) for SvPIP2;1 and SvNIP2;2 was transcribed using the Ambion mMessage mMachine Kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Xenopus laevis oocytes were injected with 46 ng of SvPIP2;1 or SvNIP2;2 cRNA in 46 μL of water, or 46 μL of water alone as a control. Injected oocytes were incubated for 72 h in Ca-Ringer’s solution. Prior to undertaking permeability assays oocytes were transferred into ND96 solution pH 7.4 (96 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 500 μg.mL-1 Streptomycin, 500 μg.mL-1 Tetracycline; 204 osmol/L) and allowed to acclimate for 30 min. Oocytes were then individually transferred into a 1:5 dilution of ND96 solution (42 osmol/L), pH 7.4, and swelling was measured for 1 min for SvPIP2;1 injected oocytes and 2 min for SvNIP2;2 injected oocytes. Oocytes were viewed under a dissecting microscope (Nikon SMZ800 light microscope, Japan) at 2× magnification. The changes in volume were captured with a Vicam color camera (Pacific Communications, Australia) at 2× magnification and recorded with IC Capture 2.0 software (The Imagine Source, US) as AVI format video files. Images were acquired every 2.5 s for 2 min measurements and every 2 s for 1 min measurements. The osmotic permeability (Pf) was calculated for water injected and cRNA injected oocytes from the initial rate of change in relative volume (dVrel/dt)I determined from the cross sectional area images captured assuming the oocytes were spherical:

Where Vi and Ai are the initial volume and area of the oocyte, respectively, Vw is the partial molar volume of water and ΔCo is the change in external osmolality. The osmolality of each solution was determined using a Fiske® 210 Micro-Sample freezing point osmometer (Fiske, Norwood, MA, USA). pH inhibition of oocyte osmotic permeability was determined as above where oocytes where bathed in 1:5 diluted ND96 solution with the addition of 50 mM Na-Acetate, pH 5.6. Topological prediction models of SvPIP2;1 and SvNIP2;2 were generated in TMHMM4 (Krogh et al., 2001) and TMRPres-2D (Spyropoulos et al., 2004) to assess potential mechanisms of pH gating.

Results

Identification of Putative Setaria viridis Aquaporins

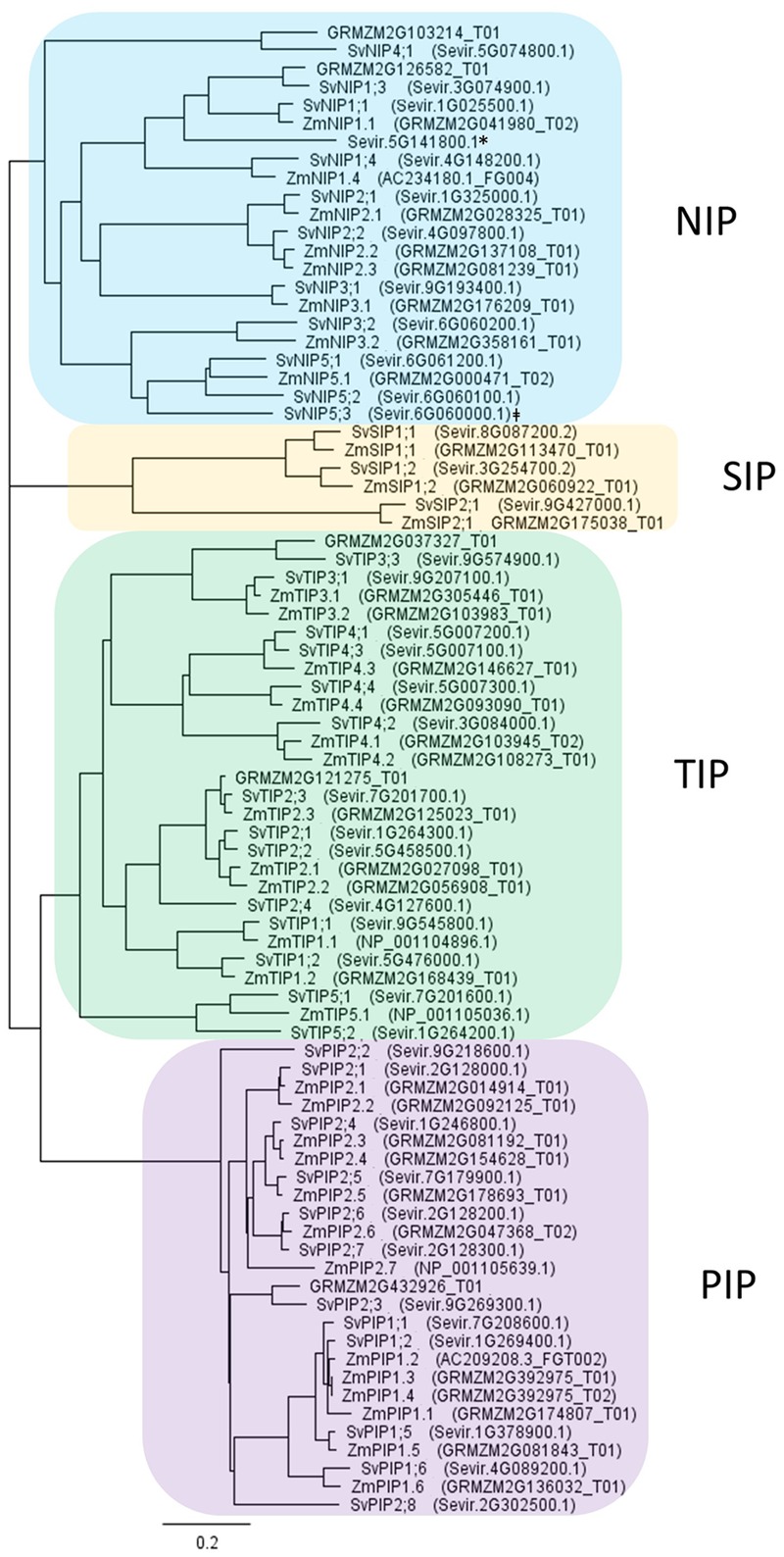

Previously published S. viridis elongating internode transcriptome data (Martin et al., 2016), and protein sequences of aquaporins identified in Arabidopsis, S. italica, barley, maize and rice were used to identify genes predicted to encode aquaporins that were highly expressed in stages of cell expansion and sugar accumulation. The nomenclature assigned to the putative aquaporins followed their relative homology to previously named maize aquaporins determined by phylogenetic analysis of protein sequences (Chaumont et al., 2001; Figure 1). S. viridis proteins separated as expected into the major aquaporin subfamilies referred to as PIPs, TIPs, NIPs, and SIPs. Within S. viridis 41 full length aquaporins were identified: 12 PIPs, 14 TIPs, 12 NIPs, and three SIPs. One predicted aquaporin identified in the genome, transcript Sevir.6G061300.1, has very high similarity to SvNIP5;3 (Sevir.6G06000.1) but may be a pseudogene as it has two large deletions in the transcript relative to SvNIP5;3. Sevir.6G061300.1 only encodes for two out of the typical six transmembrane domains characteristic of aquaporins, and no transcripts have been detected in any of the S. viridis RNA-seq libraries available through the Joint Genome Institute (JGI) Plant Gene Atlas Project (Grigoriev et al., 2011). Another truncated NIP-like transcript, Sevir.5G141800.1, was identified. It is predicted to encode a protein 112 amino acids in length with only two transmembrane domains. As it is unlikely to generate an individually functioning aquaporin it has not been named. However, unlike Sevir.6G061300.1, Sevir.5G141800.1 was included in the phylogenetic tree as it was shown to be highly expressed in several tissue types in S. viridis RNA-seq libraries available through the JGI Plant Gene Atlas Project (Grigoriev et al., 2011) and may be of interest to future studies of Setaria aquaporin-like genes.

FIGURE 1.

Phylogenetic tree based on protein sequences of aquaporins from Setaria viridis and Zea mays. S. viridis aquaporins were identified in the genome via HMMER search using aquaporins sequences from Arabidopsis, barley, maize, and rice. Maize aquaporins were included in the phylogenetic tree for ease of interpretation. The addition of aquaporin sequences from other grasses did not change the groupings. Tree was generated by neighbor-joining method using the Geneious Tree Builder program, Geneious 9.0.2. The scale bar indicates the evolutionary distance, expressed as changes per amino acid residue. Aquaporins can be grouped into four subfamilies: PIPs (plasma membrane intrinsic proteins), TIPs (tonoplast intrinsic proteins), NIPs (nodulin-like intrinsic proteins), and SIPs (small basic intrinsic proteins). ∗Sevir.5G141800.1 protein sequence is truncated, 112 amino acids in length. ‡SvNIP5;3 (Sevir.6G06000.1) may have a related pseudogene Sevir.6G061300.1.

Analysis of Setaria viridis Aquaporin Transcripts in Stem Regions

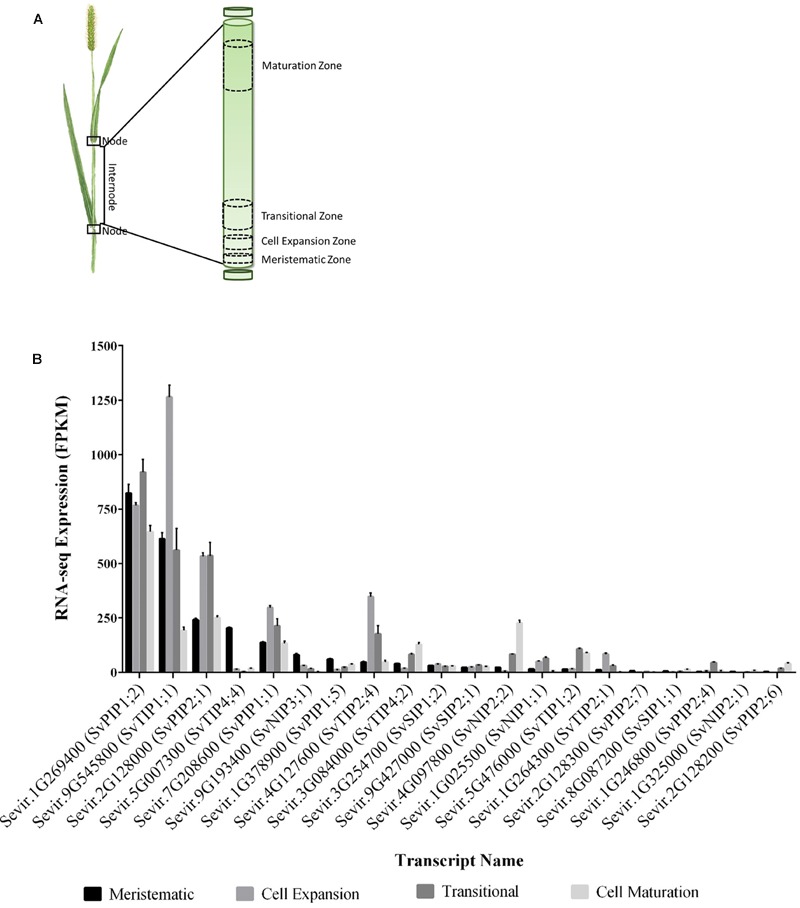

We compared the relative transcript levels of putative S. viridis aquaporin encoding genes in the different developmental regions of an elongating internode (Figure 2). We observed that SvPIP1;2 transcripts were abundant in all regions; and SvTIP1;1 transcripts were also abundant, particularly in cell expansion regions. SvPIP2;1, SvPIP1;1, SvTIP2;2, and SvTIP2;1 transcripts were detected in all regions with the highest transcript levels in cell expansion and transitional regions. Transcripts for SvTIP4;4, SvNIP3;1, and SvPIP1;5 were highest in the meristem relative to other regions; whereas SvTIP4;2, SvNIP2;2, and SvTIP1;2 transcripts were at their highest in transitional or mature regions. Low transcript levels were observed for SvSIP1;2, SvNIP1;1, and SvPIP2;4 in all regions, with maximum transcripts for SvNIP1;1 and SvPIP2;4 detected in the transitional region, and very low transcript levels were detected for SvPIP2;6, SvSIP1;1, and SvNIP2;1.

FIGURE 2.

Expression of putative aquaporins across the developmental zones of an elongating S. viridis internode. (A) Schematic of the developmental regions in an elongating internode of S. viridis as reported by Martin et al. (2016): meristematic zone, residing at the base of the internode, where cell division occurs; the cell expansion zone where cells undergo turgor driven expansion; transitional zone where cells begin to differentiate and synthesize secondary cell walls; and the maturation zone whereby expansion, differentiation and secondary cell wall synthesis cease and sugar is accumulated. (B) The expression profiles of putative S. viridis aquaporins, as identified by phylogeny to Z. mays aquaporins, were mined in the S. viridis elongating internode transcriptome (Martin et al., 2016). RNA-seq data is presented as mean FPKM ± SEM for four biological replicates from each developmental zone.

Overall the highest aquaporin transcript levels detected across the internode developmental zones were those of SvPIP1;2 (Figure 2). Previous research has indicated that the related ZmPIP1;2 interacts with PIP2 subgroup proteins targeting PIP2s to plasma membrane, and a number of PIP1 aquaporins are not associated with osmotic water permeability when expressed alone in oocytes (Fetter et al., 2004; Luu and Maurel, 2005; Zelazny et al., 2007). Our interest lay in identifying water permeable aquaporins that might be preferentially involved in delivering water to the growing stem cells and in sucrose accumulation in mature stem regions. As candidates SvPIP2;1 and SvNIP2;2 met these criteria we focussed on these two genes. SvPIP2;1 had the high transcript levels in the region of cell expansion and transcript levels of SvNIP2;2 were highest in mature stem regions (Figure 2B). The protein sequences of SvPIP2;1 and SvNIP2;2 were analyzed by the HMMER tool HMMscan which identified these candidates as belonging to the aquaporin (Major Intrinsic Protein) protein family.

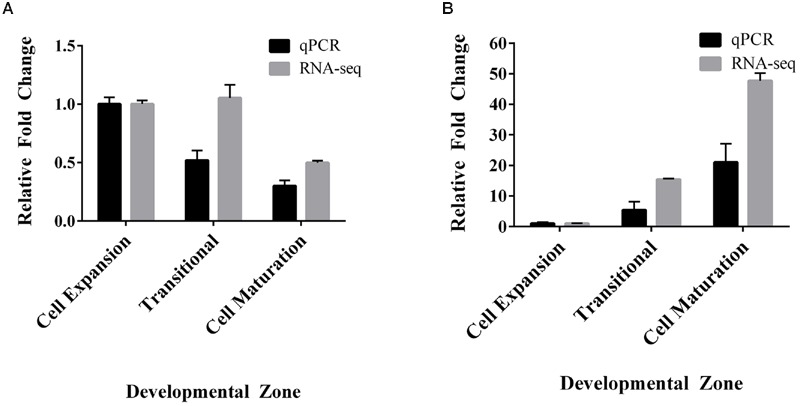

To confirm our RNA-seq expression profile observations, we measured the transcript levels of SvPIP2;1 and SvNIP2;2 in the S. viridis internode regions by RT-qPCR. Stem samples were harvested from S. viridis plants grown under glasshouse conditions with the light period artificially supplemented by use of metal halide lamps to replicate as closely as possible the conditions used by Martin et al. (2016) for the RNA-seq analysis. We assessed the relative fold change of gene expression normalized to the cell expansion zone and similar trends were observed for the RT-qPCR expression data compared to the RNA-seq transcriptome data (Figure 3). SvPIP2;1 transcript levels were high in the cell expansion region and decreased toward the maturation region and SvNIP2;2 transcript levels were highest in mature stem tissues.

FIGURE 3.

Comparison of relative fold changes between RNA-seq and RT-qPCR of SvPIP2;1 and SvNIP2;2 in an elongating internode of S. viridis. (A) SvPIP2;1. (B) SvNIP2;2. Data is mean relative fold change in expression ± SEM. Data for RNA-seq and RT-qPCR was normalized relative to the cell expansion zone expression level.

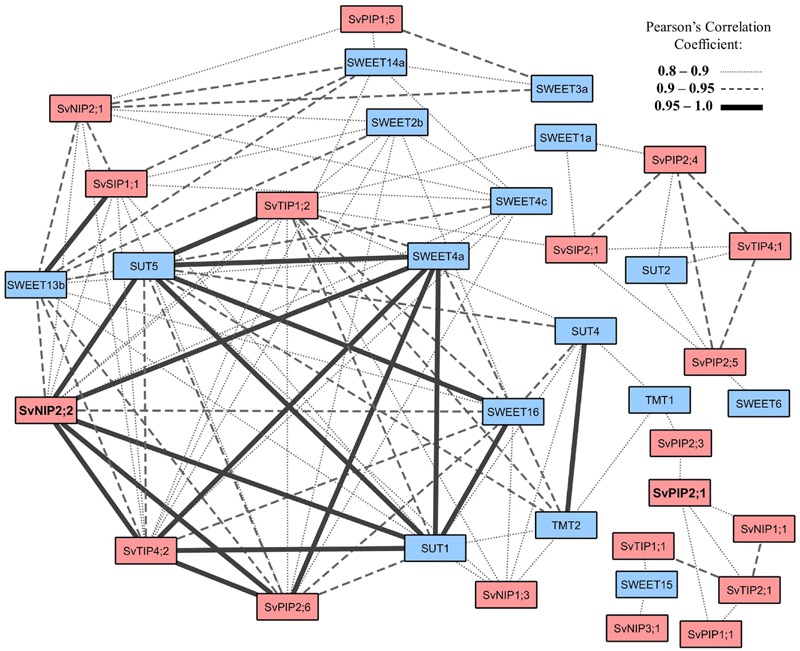

We are interested in the coordination of water and sugar transport related processes in developing grass stems. As a tool to investigate this, we further analyzed the stem transcriptome data to test whether any aquaporin and sugar transport related genes were co-expressed. Putative S. viridis sugar transporters were identified from the internode transcriptome (Martin et al., 2016) by homology to the rice sugar transporter families: SUTs, SWEETs, and TMTs (Supplementary Figures S2–S4). A co-expression gene network of the aquaporins and sugar transporters expressed in the S. viridis stem was generated in Cytoscape v3.4.0 using Pearson’s correlation coefficients calculated by MetScape (Karnovsky et al., 2012) (Figure 4). This analysis revealed that for a number of aquaporins and sugar transport related genes there was a high correlation in expression: SvPIP2;1 expression correlated with the expression of SvPIP2;3, SvTIP2;1, and SvNIP1;1 (0.8–0.9); and the correlation coefficients for co-expression of SvPIP2;1 with SvPIP2;5, SvTIP4;1, SvTIP1;2, and SWEET1a were in the range of 0.8–0.9. Most notable was the high correlation (0.95–1.0) of expression of SvNIP2;2 with sugar transport related genes SvSUT5, SvSUT1, SvSWEET4a and with SvTIP4;2 and SvPIP2;6. The correlation between expression of SvNIP2;2 and SvSWEET13b and SvSWEET16 was also high (0.9–0.95). The cis-acting regulatory elements of the promoter regions of the aquaporin candidates SvNIP2;2 and SvPIP2;1, and the putative sugar transporter genes SvSUT1, SvSUT5, and SvSWEET4a were analyzed (Supplementary Figure S5). There was no obvious relationship between the correlation of expression of SvNIP2;2 and SvSUT1, SvSUT5 and SvSWEET4a and their cis-acting regulatory elements.

FIGURE 4.

Co-expression network of putative S. viridis aquaporin and sugar transporter genes identified in an elongating internode. The co-expressed gene network was generated from the stem specific aquaporins (Figure 2) and sugar transporters identified in the S. viridis elongating internode transcriptome reported by Martin et al. (2016). Raw FPKM values were Log2 transformed and Pearson’s correlation coefficients (0.8–1.0) were calculated in the MetScape app in Cytoscape v3.4.0. Sugar transporters in the S. viridis elongating internode were identified by homology to rice sugar transporter genes (Supplementary Figures S2–S4). Sugar transport related genes are color filled with blue and aquaporin genes with orange. SvNIP2;2 and SvPIP2;1 are in bold font.

Characterisation of Setaria viridis PIP2;1 and NIP2;2 in Xenopus laevis Oocytes

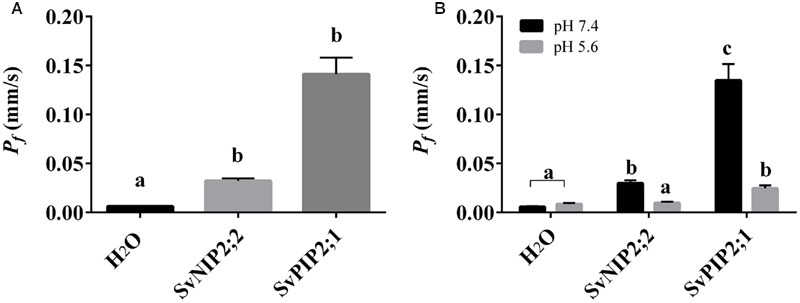

To explore whether the proteins encoded by SvPIP2;1 and SvNIP2;2 function as water channels they were expressed in the heterologous X. laevis oocytes system. Water with or without 46 ng of SvPIP2;1 and SvNIP2;2 cRNA was injected into oocytes and the swelling of these oocytes in response to bathing in a hypo-osmotic solution (pH 7.4) was measured (Figure 5A). The osmotic permeability (Pf) of cRNA injected oocytes was calculated and compared to the osmotic permeability of water injected oocytes. Water injected oocytes had a Pf of 0.60 ± 0.08 × 10-2 mm s-1. Relative to water injected control oocytes SvPIP2;1 and SvNIP2;2 cRNA injected oocytes had significantly higher Pf of 14.13 ± 1.66 × 10-2 mm s-1 and 3.22 ± 0.28 × 10-2 mm s-1, respectively (p < 0.05).

FIGURE 5.

Osmotic permeability (Pf) of Xenopus laevis oocytes injected with SvNIP2;2 and SvPIP2;1 cRNA. (A) Osmotic permeability (Pf) of water (H2O) injected and SvNIP2;2 and SvPIP2;1 cRNA (46 ng) injected oocytes. Oocytes were transferred into a hypo-osmotic solution, pH 7.4, and Pf was calculated by video monitoring of the rate of oocyte swelling. (B) Effect of lowering oocyte cytosolic pH on osmotic permeability (Pf) of H2O and SvNIP2;2 and SvPIP2;1 cRNA injected oocytes by bathing in hypo-osmotic solution supplemented with 50 mM Na-acetate, pH 5.6, n = 12–14; a = non-significant; b = p < 0.05; c = p < 0.005.

The effect of lowering oocyte cytosolic pH was determined by bathing oocytes in an external hypo-osmotic solution at pH 5.6 with the addition of Na-Acetate (Figure 5B). Reduced osmotic permeability of the cRNA injected oocyte membrane was observed in response to the low pH treatment. A reduction in Pf was observed for SvPIP2;1 and SvNIP2;2 cRNA injected oocytes bathed in an external hypo-osmotic solution at pH 5.6 relative to the pH 7.4 solution indicating that SvPIP2;1 and SvNIP2;2 have pH gating mechanisms (Figure 5B). Water injected oocytes in the pH 5.6 Na-Acetate solution had Pf of 0.84 ± 0.13 × 10-2 mm s-1. SvNIP2;2 and SvPIP2;1 cRNA injected oocytes in the pH 5.6 solution had significantly lower Pf of 2.46 ± 0.32 × 10-2 mm s-1 and 0.97 ± 0.13 × 10-2 mm s-1, respectively, compared to those in pH 7.4 solution (p < 0.05). SvPIP2;1 and SvNIP2;2 associated osmotic permeability and pH gating observations indicate that these proteins can function as water channels. The mechanism of pH gating for other plant aquaporins is the protonation of a Histidine residue in the Loop D structure; topological modeling of SvPIP2;1 and SvNIP2;2 predicted that the Loop D of SvPIP2;1 contains a Histidine residue while SvNIP2;2 Loop D does not contain a His residue (Supplementary Figure S6).

Discussion

Roles of Aquaporins in Grass Stem Development

On the basis of amino acid sequence comparison with known aquaporins in Arabidopsis, rice and maize, the genomes of sugarcane, sorghum and S. italica include 42, 41, and 42 predicted aquaporin encoding genes, respectively (da Silva et al., 2013; Reddy et al., 2015; Azad et al., 2016). In S. viridis 41 aquaporin encoding genes were identified that group into four clades corresponding to NIPs, TIPs, SIPs, and PIPs (Figure 1). We note that Azad et al. (2016) named the Setaria aquaporins in an order consecutive with where they are found in the genome. For ease of comparing related aquaporins in C4 grasses of interest, we named the Setaria aquaporins based on their homology to previously named maize aquaporins (Figure 1) (Chaumont et al., 2001), of course high homology and the same name does not infer the same function. In the S. viridis elongating internode transcriptome, we detected transcripts for 19 putative aquaporin encoding genes, including 5 NIPs, 6 TIPs, 2 SIPs, and 6 PIPs (Figures 2 and 3; Martin et al., 2016). In mature S. viridis internode tissues, the transcript levels of TIPs and NIPs was generally low with the exception of SvNIP2;2, SvTIP4;2, and SvTIP1;2. In a sorghum stem transcriptome report investigating SWEET gene involvement in sucrose accumulation, we note that transcripts for all 41 sorghum aquaporins were detected in pith and rind tissues in 60-day-old plants (Reddy et al., 2015; Mizuno et al., 2016). Of those 41 aquaporins the expression of 16, primarily NIPs and TIPs, was relatively low. However, PIP1;2, PIP2;1, and NIP2;2 homologs were all highly expressed in pith and rind of sorghum plants after heading, which is consistent with our findings for the S. viridis homologs of these genes (Figure 2; Mizuno et al., 2016). Comparisons with other gene expression studies for C4 grass stem tissues were not possible as in most studies the internode tissue has not been separated into different developmental zones or the study has not reported aquaporin expression (Carson and Botha, 2000, 2002; Casu et al., 2007).

Relationships between Sink Strength, Sink Size, Water Flow, and the Function of Aquaporins

The molecular and physiological mechanisms that determine stem cell number and cell size in turn determine the capacity of the stem as a sink (Ho, 1988; Herbers and Sonnewald, 1998). Examples have been reported in the literature where stem volume and sucrose concentration has been increased, in sugarcane and sorghum, by increasing cell size (Slewinski, 2012; Patrick et al., 2013). Larger cell size may improve sink strength by increasing membrane surface area available to sucrose transport (increasing import capacity), increasing single cell capacity to accumulate greater concentrations of sucrose in parenchyma cell vacuoles due to increased individual cell volume (increasing storage capacity), and increasing lignocellulosic biomass.

Cell expansion and growth are highly sensitive to water potential. This is because expansion requires a continuous influx of water into the cell to maintain turgor pressure (Hsiao and Acevedo, 1974; Cosgrove, 1986, 2005). The diffusion of water across a plant cell membrane is facilitated by aquaporins (Kaldenhoff and Fischer, 2006). Aquaporins function throughout all developmental stages, but several PIP aquaporins have been found to be particularly highly expressed in regions of cell expansion (Chaumont et al., 1998; Maurel et al., 2008; Besse et al., 2011). Here, we report that in the S. viridis internode, SvPIP2;1 was highly expressed in regions undergoing cell expansion (Figure 2). Positive correlations have been reported for the relationship between PIP mRNA and protein expression profiles of PIP isoforms in the expanding regions of embryos, roots, hypocotyls, leaves, and reproductive organs indicating that gene expression is a key mechanisms to regulate PIP function (Maurel et al., 2002; Hachez et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2008). Therefore, high expression of SvPIP2;1 in the expanding zone of S. viridis internodes indicates that this gene may be involved in the process of water influx in this tissue to maintain turgor pressure for growth.

The roles of a number of PIP proteins in hydraulic conductivity in plant roots and leaves have been reported but PIP function in stems is largely unexplored. The regulation of the hydraulic properties of expanding root tissues by PIP expression was analyzed by Péret et al. (2012) and they reported that auxin mediated reduction of Arabidopsis thaliana (At) PIP gene expression resulted in delayed lateral root emergence. Previously AtPIP2;2 anti-sense mutants were reported to have lower (25–30%) hydraulic conductivity of root cortex cells than control plants (Javot et al., 2003). PIP2 family aquaporins, involved in cellular water transport in roots have also been linked to water movement in leaves, seeds, and reproductive organs (Schuurmans et al., 2003; Bots et al., 2005). The roles of PIP proteins in maintenance of hydraulic conductivity and cell expansion in stems are likely to be equally as important as the roles reported for PIPs in the expanding tissues of roots and leaves. One study in rice reported OsPIP1;1 and OsPIP2;1 as being highly expressed in the zone of cell expansion in rapidly growing internodes (Malz and Sauter, 1999). Expression analysis of sugarcane genes associated with sucrose content identified that some unnamed PIP isoforms were highly expressed in immature internodes, and in high sugar yield cultivars (Papini-Terzi et al., 2009). Proteins from the PIP2 subfamily in particular in maize, spinach and Arabidopsis have been shown to be highly permeable to water (Johansson et al., 1998; Chaumont et al., 2000; Kaldenhoff and Fischer, 2006). Here, we demonstrate, by expression of SvPIP2;1 in Xenopus oocytes and analysis of water permeability, that this protein functions as a water channel (Figure 5A).

Aquaporin Function and Sugar Accumulation in Mature Grass Stems

The accumulation of sucrose to high concentrations in panicoid stems rapidly increases with the cessation of cell expansion, which is also associated with the deposition of secondary cell walls (Hoffmann-Thoma et al., 1996). In the mature regions of the stem internodes, imported sucrose is no longer required for growth, development, or as a necessary precursor to structural elements and it is stored in the vacuoles of ground parenchyma cells or the apoplasm (Rae et al., 2009). Phloem unloading and the delivery of sucrose to these storage cells may occur via an apoplasmic pathway as in sorghum or a symplasmic pathway as in sugarcane (Welbaum and Meinzer, 1990; Walsh et al., 2005). The degree of suberisation and/or lignification of cell walls surrounding the phloem may influence stem sucrose storage traits by restricting apoplasmic pathways of sucrose transport. In potato tubers and Arabidopsis ovules a switch between apoplasmic and symplasmic pathways of delivering sucrose to storage sites has been reported (Viola et al., 2001; Werner et al., 2011). Similarly, a switch from symplasmic to apoplasmic transport pathways has been proposed for sorghum as internodes approach maturity (Tarpley et al., 2007; Milne et al., 2015). Both apoplasmic and symplasmic mechanisms of phloem unloading require the maintenance of low sugar concentration in the cytoplasm of parenchymal storage cells. Control of hydrostatic pressure is facilitated by the sequestration of sucrose into the vacuole by tonoplast localized SUTs or into the apoplasm by plasma membrane localized SUTs (Slewinski, 2011). Members of the SUT and TMT families have been shown to function on the tonoplast to facilitate sucrose accumulation in the vacuole (Reinders et al., 2008; Wingenter et al., 2010; Bihmidine et al., 2016). In mature stem tissue plasma membrane localized SWEETs, SUTs, and possibly some NIPs may have a role in transporting sugar into the apoplasm (Milne et al., 2013; Chen, 2014).

The cell maturation zone is characterized by cells that have ceased expansion and differentiation and have realized their sugar accumulation capacity (Rohwer and Botha, 2001; McCormick et al., 2009). In mature sink tissues, the movement of water and dissolved photoassimilates from the phloem to storage parenchyma cells may be driven by differences in solute concentration and hydrostatic pressure (Turgeon, 2010; De Schepper et al., 2013). However, the movement of water and sucrose by diffusion or bulk-flow requires the continued maintenance of low cytosolic sucrose concentrations by accumulation of sucrose into the vacuole or efflux into the apoplasm for storage (Grof et al., 2013). Throughout internode development, the internal cell pressure of storage parenchyma cells in sugarcane remains relatively constant despite increasing solute concentrations toward maturation (Moore and Cosgrove, 1991). As mature cells tend to have heavily lignified cell walls that limit the ability of the protoplast to expand in response to water flux the equilibration of storage parenchyma cell turgor is likely to be achieved by the partitioning of sucrose into the vacuole and apoplasm, and efflux of water into the apoplasm (Moore and Cosgrove, 1991; Vogel, 2008; Keegstra, 2010; Moore and Botha, 2013). Phloem water effluxed into the apoplasm may then be recycled back to the vascular bundles (Welbaum et al., 1992).

Members of the NIPs are candidates for water and neutral solute permeation, and some NIPs could have a role in water and solute efflux to the apoplasm in mature stem cells (Takano et al., 2006; Kamiya et al., 2009; Li et al., 2009; Hanaoka et al., 2014). The NIP subfamily is divided into the subgroups NIP I, NIP II, and NIP III based on the composition of the ar/R selectivity filter (Liu and Zhu, 2010). NIP III subgroup homologs have reported permeability to water, urea, boric acid, and silicic acid (Bienert et al., 2008; Ma et al., 2008; Ma and Yamaji, 2008; Li et al., 2009). In grasses NIP2;2 homologs, from the NIP III subgroup, have been shown to localize to the plasma membrane (Ma et al., 2006).

In the S. viridis internode, SvNIP2;2 had relatively high transcript levels in mature stem tissue where sugar accumulates, and it can function as a water channel, although with a relatively low water permeability compared to SvPIP2;1 (Figures 2 and 5A). Our analysis of gene co-expression in stem tissues revealed high correlation between the expression of SvNIP2;2 and five putative S. viridis sugar transporter genes (Figure 4). Co-expression can indicate that genes are controlled by the same transcriptional regulatory program, may be functionally related, or be members of the same pathway or protein complex (Eisen et al., 1998; Yonekura-Sakakibara and Saito, 2013). The strong correlation between expression of SvNIP2;2 and key putative sugar transport related genes such as SvSUT5, SvSUT1, SvSWEET4a, SvSWEET13b, and SvSWEET16 indicates that they may be involved in a related biological process such as stem sugar accumulation. It is likely that one or more of the SWEETs have roles in transporting sugars out of the stem parenchyma cells into the apoplasm. SvNIP2;2 may be permeable to neutral solutes as well as water and the role of this protein in the mature stem could be in effluxing a solute to adjust osmotic pressure allowing for greater sugar storage capacity. The rice and soybean (Glycine max L.) NIP2;2 proteins are permeable to silicic acid and silicon, respectively (Ma et al., 2006; Zhao et al., 2010; Deshmukh et al., 2013). The deposition of silicic acid into the apoplasm, where it associates with the cell wall matrix as a polymer of hydrated amorphous silica (Epstein, 1994; Ma et al., 2004; Coskun et al., 2016), strengthens the culm to reduce lodging events, and increases plant resistance to pathogens and abiotic stress factors (Mitani, 2005).

SvNIP2;2 water permeability was gated by pH (Figure 5B). Gating of water channel activity has been reported for PIPs, including SvPIP2;1 (Figure 5B), and for the TIP2;1 isoform found in grapevine (Törnroth-Horsefield et al., 2006; Leitao et al., 2012; Frick et al., 2013). The mechanism of pH gating for these AQPs is the protonation of a Histidine residue located on the cytoplasmic Loop D where site-directed mutagenesis studies of the Loop D His residue results in a loss of pH dependent water permeability (Tournaire-Roux et al., 2002; Leitao et al., 2012; Frick et al., 2013). However, although SvNIP2;2 water permeability was pH dependent the predicted Loop D structure does not contain a His residue (Supplementary Figure S5), hence for SvNIP2;2 the mechanism for pH gating is not clear.

Conclusion

Our observations of high transcript levels of SvPIP2;1 in expanding S. viridis stem regions and high transcript levels of SvNIP2;2 in mature stems inspired us to test the function of the proteins encoded by these genes. We found that SvPIP2;1 and SvNIP2;2 can function as pH gated water channels. We hypothesize that in stem tissues SvPIP2;1 is involved in cell growth and that SvNIP2;2 may facilitate water movement and potentially the flow of other solutes into the apoplasm to sustain solute transportation by bulk-flow, and possibly ‘recycle’ water used for solute delivery back to the xylem. It is expected that SvPIP2;1 could have additional roles, as other PIP water channels have been shown to also be permeable to CO2, hydrogen peroxide, urea, sodium and arsenic (Siefritz et al., 2001; Uehlein et al., 2003; Mosa et al., 2012; Bienert and Chaumont, 2014; Byrt et al., 2016b). SvNIP2;2 could have roles such as transporting neutral solutes to the apoplasm, as previous studies report silicic acid, urea, and boric acid permeability for other NIPS (Bienert et al., 2008; Ma et al., 2008; Ma and Yamaji, 2008; Li et al., 2009; Deshmukh et al., 2013). Transporting solutes other than sucrose into the apoplasm in mature stem tissues may be an important part of the processes that supports high sucrose accumulation capacity in grass stem parenchyma cells. The next steps in establishing the respective functions of SvPIP2;1 and SvNIP2;2 in stem growth and sugar accumulation in S. viridis will require testing of the permeability of these proteins to a range of other solutes and modification of their function in planta.

Author Contributions

CG conceived and designed the work. SM, HO, LC, and JP acquired the data. SM, ST, CB, and CG analyzed and interpreted the data. SM and CB drafted and revised the work. All authors commented on the manuscript. SM, ST, RF, CB, and CG revised the work critically for intellectual content.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Wendy Sullivan for preparation of oocytes. We thank Kate Hutcheon for advice on qPCR and Antony Martin for comments on early planning documents and cloning plans.

Funding. This research was supported by The Australian Research Council (ARC) Centre of Excellence in Plant Energy Biology (CE140100008) and CB (ARC DE150100837).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2016.01815/full#supplementary-material

References

- Azad A. K., Ahmed J., Alum A., Hasan M., Ishikawa T., Sawa Y., et al. (2016). Genome-wide characterization of major intrinsic proteins in four grass plants and their non-aqua transport selectivity profiles with comparative perspective. PLoS ONE 11:e0157735 10.1371/journal.pone.0157735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrieu F., Chaumont F., Chrispeels M. J. (1998). High expression of the tonoplast aquaporin ZmTIP1 in epidermal and conducting tissues of maize. Plant Physiol. 117 1153–1163. 10.1104/pp.117.4.1153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennetzen J. L., Schmutz J., Wang H., Percifield R., Hawkins J., Pontaroli A. C., et al. (2012). Reference genome sequence of the model plant Setaria. Nat. Biotechnol. 30 555–564. 10.1038/nbt.2196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besse M., Knipfer T., Miller A. J., Verdeil J.-L., Jahn T. P., Fricke W. (2011). Developmental pattern of aquaporin expression in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) leaves. J. Exp. Bot. 62 4127–4142. 10.1093/jxb/err175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienert G. P., Chaumont F. (2014). Aquaporin-facilitated transmembrane diffusion of hydrogen peroxide. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1840 1596–1604. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienert G. P., Thorsen M., Schüssler M. D., Nilsson H. R., Wagner A., Tamás M. J., et al. (2008). A subgroup of plant aquaporins facilitate the bi-directional diffusion of As(OH)3 and Sb(OH)3 across membranes. BMC Biol. 6:26 10.1186/1741-7007-6-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bihmidine S., Julius B. T., Dweikat I., Braun D. M. (2016). Tonoplast sugar transporters (SbTSTs) putatively control sucrose accumulation in sweet sorghum stems. Plant Signal. Behav. 11:e1117721 10.1080/15592324.2015.1117721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botha F. C., Black K. G. (2000). Sucrose phosphate synthase and sucrose synthase activity during maturation of internodal tissue in sugarcane. Aust. J. Plant Physiol. 27 81–85. [Google Scholar]

- Bots M., Feron R., Uehlein N., Weterings K., Kaldenhoff R., Mariani T. (2005). PIP1 and PIP2 aquaporins are differentially expressed during tobacco anther and stigma development. J. Exp. Bot. 56 113–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brutnell T. P., Bennetzen J. L., Vogel J. P. (2015). Brachypodium distachyon and Setaria viridis: Model genetic systems for the grasses. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 66 465–485. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrt C. S., Betts N. S., Tan H.-T., Lim W. L., Ermawar R. A., Nguyen H. Y., et al. (2016a). Prospecting for energy-rich renewable raw materials: sorghum stem case study. PLoS ONE 11:e0156638 10.1371/journal.pone.0156638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrt C. S., Grof C. P. L., Furbank R. T. (2011). C4 plants as biofuel feedstocks: optimising biomass production and feedstock quality from a lignocellulosic perspective. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 53 120–135. 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2010.01023.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrt C. S., Zhao M., Kourghi M., Bose J., Henderson S. W., Qiu J., et al. (2016b). Non-selective cation channel activity of aquaporin AtPIP2;1 regulated by Ca2+ and pH. Plant Cell Environ. 10.1111/pce.12832 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson D., Botha F. (2002). Genes expressed in sugarcane maturing internodal tissue. Plant Cell Rep. 20 1075–1081. 10.1007/s00299-002-0444-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carson D. L., Botha F. C. (2000). Preliminary analysis of expressed sequence tags for sugarcane. Crop Sci. 40:1769 10.2135/cropsci2000.4061769x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Casu R. E., Jarmey J. M., Bonnett G. D., Manners J. M. (2007). Identification of transcripts associated with cell wall metabolism and development in the stem of sugarcane by Affymetrix GeneChip sugarcane genome array expression profiling. Funct. Integr. Genomics 7 153–167. 10.1007/s10142-006-0038-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaumont F., Barrieu F., Herman E. M., Chrispeels M. J. (1998). Characterization of a maize tonoplast aquaporin expressed in zones of cell division and elongation. Plant Physiol. 117 1143–1152. 10.1104/pp.117.4.1143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaumont F., Barrieu F., Jung R., Chrispeels M. J. (2000). Plasma membrane intrinsic proteins from Maize cluster in two sequence subgroups with differential aquaporin activity. Plant Physiol. 122 1025–1034. 10.1104/pp.122.4.1025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaumont F., Barrieu F., Wojcik E., Chrispeels M. J., Jung R. (2001). Aquaporins constitute a large and highly divergent protein family in Maize. Plant Physiol. 125 1206–1215. 10.1104/pp.125.3.1206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L.-Q. (2014). SWEET sugar transporters for phloem transport and pathogen nutrition. New Phytol. 201 1150–1155. 10.1111/nph.12445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove D. (1986). Biophysical control of plant growth. Ann. Rev. Plant Physiol. 37 377–405. 10.1146/annurev.pp.37.060186.002113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove D. J. (2005). Growth of the plant cell wall. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6 850–861. 10.1038/nrm1746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coskun D., Britto D. T., Huynh W. Q., Kronzucker H. J. (2016). The role of silicon in higher plants under salinity and drought stress. Front. Plant Sci. 7:1072 10.3389/fpls.2016.01072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czechowski T., Stitt M., Altmann T., Udvardi M. K., Scheible W.-R. (2005). Genome-wide identification and testing of superior reference genes for transcript normalization in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 139 5–17. 10.1104/pp.105.063743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva M. D., Silva R. L. D. O., Costa Ferreira Neto J. R., Guimarães A. C. R., Veiga D. T., Chabregas S. M., et al. (2013). Expression analysis of Sugarcane aquaporin genes under water deficit. J. Nucleic Acids 2013 1–14. 10.1155/2013/763945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielson J. Å, Johanson U. (2008). Unexpected complexity of the Aquaporin gene family in the moss Physcomitrella patens. BMC Plant Biol. 8:45 10.1186/1471-2229-8-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Schepper V., De Swaef T., Bauweraerts I., Steppe K. (2013). Phloem transport: a review of mechanisms and controls. J. Exp. Bot. 64 4839–4850. 10.1093/jxb/ert302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshmukh R. K., Vivancos J., Guerin V., Sonah H., Labbe C., Belzile F., et al. (2013). Identification and functional characterization of silicon transporters in soybean using comparative genomics of major intrinsic proteins in Arabidopsis and rice. Plant Mol. Biol. 83 303–315. 10.1007/s11103-013-0087-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen M. B., Spellman P. T., Brown P. O., Botstein D. (1998). Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Genetics 95 14863–14868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein E. (1994). The anomaly of silicon in plant biology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91 11–17. 10.1073/pnas.91.1.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ermawar R. A., Collins H. M., Byrt C. S., Henderson M., O’Donovan L. A., Shirley N. J., et al. (2015). Genetics and physiology of cell wall polysaccharides in the model C4 grass, Setaria viridis spp. BMC Plant Biol. 15:236 10.1186/s12870-015-0624-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetter K., Van Wilder V., Moshelion M., Chaumont F. (2004). Interactions between plasma membrane aquaporins modulate their water channel activity. Plant Cell 16 215–228. 10.1105/tpc.017194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn R. D., Clements J., Arndt W., Miller B. L., Wheeler T. J., Schreiber F., et al. (2015). HMMER web server: 2015 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 43 30–38. 10.1093/nar/gkv397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick A., Järvå M., Törnroth-Horsefield S. (2013). Structural basis for pH gating of plant aquaporins. FEBS Lett. 587 989–993. 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.02.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasziou K. T., Gayler K. R. (1972). Storage of sugars in stalks of sugar cane. Bot. Rev. 36 471–488. 10.1007/BF02859248 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grigoriev I. V., Nordberg H., Shabalov I., Aerts A., Cantor M., Goodstein D., et al. (2011). The genome portal of the department of energy joint genome institute. Nucleic Acids Res. 42 D26–D31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grof C. P. L., Byrt C. S., Patrick J. W. (2013). “Phloem transport of resources,” in Sugarcane: Physiology, Biochemistry, and Functional Biology eds Moore P., Botha F. (Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; ) 267–305. [Google Scholar]

- Grof C. P. L., Campbell J. A. (2001). Sugarcane sucrose metabolism: scope for molecular manipulation. Aust. J. Plant Physiol. 28 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hachez C., Heinen R. B., Draye X., Chaumont F. (2008). The expression pattern of plasma membrane aquaporins in maize leaf highlights their role in hydraulic regulation. Plant Mol. Biol. 68 337–353. 10.1007/s11103-008-9373-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanaoka H., Uraguchi S., Takano J., Tanaka M., Fujiwara T. (2014). OsNIP3;1, a rice boric acid channel, regulates boron distribution and is essential for growth under boron-deficient conditions. Plant J. 78 890–902. 10.1111/tpj.12511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawker J. S. (1985). “Sucrose,” in Biochemistry of Storage Carbohydrates in Green Plants eds Dey P., Dixon R. (New York, NY: Academic Press; ) 1–51. [Google Scholar]

- Herbers K., Sonnewald U. (1998). Molecular determinants of sink strength. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 1 207–216. 10.1016/S1369-5266(98)80106-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho L. C. (1988). Metabolism and compartmentation of imported sugars in sink organs in relation to sink strength. Ann. Rev. Plant Physiol. 39 355–378. 10.1146/annurev.pp.39.060188.002035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann-Thoma G., Hinkel K., Nicolay P., Willenbrink J. (1996). Sucrose accumulation in sweet sorghum stem internodes in relation to growth. Physiologia 97 277–284. 10.1034/j.1399-3054.1996.970210.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hove R. M., Ziemann M., Bhave M. (2015). Identification and expression analysis of the barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) aquaporin gene family. PLoS ONE 10:e0128025 10.1371/journal.pone.0128025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao T. C., Acevedo E. (1974). Plant responses to water deficits, water-use efficiency, and drought resistance. Agric. Meteorol. 14 59–84. 10.1016/0002-1571(74)90011-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ibraheem O., Botha C. E. J., Bradley G. (2010). In silico analysis of cis-acting regulatory elements in 5’ regulatory regions of sucrose transporter gene families in rice (Oryza sativa Japonica) and Arabidopsis thaliana. Comput. Biol. Chem. 34 268–283. 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2010.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javot H., Lauvergeat V., Santoni V., Martin-Laurent F., Güçlü J., Vinh J., et al. (2003). Role of a single aquaporin isoform in root water uptake. Plant Cell 15 509–522. 10.1105/tpc.008888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johanson U., Gustavsson S. (2002). A new subfamily of major intrinsic proteins in plants. Mol. Biol. Evol 19 456–461. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johanson U., Karlsson M., Johansson I., Gustavsson S., Sjö S., Fraysse L., et al. (2001). The complete set of genes encoding Major Intrinsic Proteins in Arabidopsis provides a framework for a new nomenclature for Major Intrinsic Proteins in plants. Plant Physiol. 126 1358–1369. 10.1104/pp.126.4.1358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson I., Karlsson M., Shukla V. K., Chrispeels M. J., Larsson C., Kjellbom P. (1998). Water transport activity of the plasma membrane aquaporin PM28A is regulated by phosphorylation. Plant Cell 10 451–459. 10.1105/tpc.10.3.451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaldenhoff R., Fischer M. (2006). Functional aquaporin diversity in plants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Biomembr. 1758 1134–1141. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya T., Tanaka M., Mitani N., Ma J. F., Maeshima M., Fujiwara T. (2009). NIP1; 1, an aquaporin homolog, determines the arsenite sensitivity of Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Biol. Chem. 284 2114–2120. 10.1074/jbc.M806881200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnovsky A., Weymouth T., Hull T., Tarcea V. G., Scardoni G., Laudanna C., et al. (2012). Metscape 2 bioinformatics tool for the analysis and visualization of metabolomics and gene expression data. Bioinforma. Orig. Pap. 28 373–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keegstra K. (2010). Plant cell walls. Plant Physiol. 154 483–486. 10.1104/pp.110.161240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klie M., Debener T. (2011). Identification of superior reference genes for data normalisation of expression studies via quantitative PCR in hybrid roses (Rosa hybrida). BMC Res. Notes 41:518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogh A., Larsson B., von Heijne G., Sonnhammer E. L. (2001). Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden markov model: application to complete genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 305 567–580. 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang A. (1990). Xylem, phloem and transpiration flows in developing Apple fruits. J. Exp. Bot. 41 645–651. 10.1093/jxb/41.6.645 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lang A., Thorpe M. R. (1989). Xylem, phloem and transpiration flows in a grape: application of a technique for measuring the volume of attached fruits to high resolution using archimedes’. Principle. J. Exp. Bot. 40 1069–1078. 10.1093/jxb/40.10.1069 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leitao L., Prista C., Moura T. F., Loureiro-Dias M. C., Soveral G. (2012). Grapevine aquaporins: gating of a tonoplast intrinsic protein (TIP2;1) by cytosolic pH. PLoS ONE 7:e33219 10.1371/journal.pone.0033219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lescot M., Déhais P., Thijs G., Marchal K., Moreau Y., Van De Peer Y., et al. (2002). PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 30 325–327. 10.1093/nar/30.1.325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P., Brutnell T. P. (2011). Setaria viridis and Setaria italica, model genetic systems for the Panicoid grasses. J. Exp. Bot. 62 3031–3037. 10.1093/jxb/err096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R. Y., Ago Y., Liu W. J., Mitani N., Feldmann J., McGrath S. P., et al. (2009). The rice aquaporin Lsi1 mediates uptake of methylated arsenic species. Plant Physiol. 150 2071–2080. 10.1104/pp.109.140350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D., Tu L., Wang L., Li Y., Zhu L., Zhang X. (2008). Characterization and expression of plasma and tonoplast membrane aquaporins in elongating cotton fibers. Plant Cell Rep. 27 1385–1394. 10.1007/s00299-008-0545-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q. P., Zhu Z. J. (2010). Functional divergence of the NIP III subgroup proteins involved altered selective constraints and positive selection. BMC Plant Biol. 10:256 10.1186/1471-2229-10-256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luu D. T., Maurel C. (2005). Aquaporins in a challenging environment: molecular gears for adjusting plant water status. Plant Cell Environ. 28 85–96. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2004.01295.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J. F., Mitani N., Nagao S., Konishi S., Tamai K., Iwashita T., et al. (2004). Characterization of the silicon uptake system and molecular mapping of the silicon transporter gene in rice. Plant Physiol. 136 3284–3289. 10.1104/pp.104.047365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J. F., Tamai K., Yamaji N., Mitani N., Konishi S., Katsuhara M., et al. (2006). A silicon transporter in rice. Nature 440 688–691. 10.1038/nature04590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J. F., Yamaji N. (2008). Functions and transport of silicon in plants. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65 3049–3057. 10.1007/s00018-008-7580-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J. F., Yamaji N., Mitani N., Xu X.-Y., Su Y.-H., Mcgrath S. P., et al. (2008). Transporters of arsenite in rice and their role in arsenic accumulation in rice grain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 9931–9935. 10.1073/pnas.0802361105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malz S., Sauter M. (1999). Expression of two PIP genes in rapidly growing internodes of rice is not primarily controlled by meristem activity or cell expansion. Plant Mol. Biol. 40 985–995. 10.1023/A:1006265528015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin A. P., Palmer W. M., Brown C., Abel C., Lunn J. E., Furbank R. T., et al. (2016). A developing Setaria viridis internode: an experimental system for the study of biomass generation in a C4 model species. Biotechnol. Biofuels 9 1–12. 10.1186/s13068-016-0457-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurel C. (1997). Aquaporins and water permeability of plant membranes. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 48 399–429. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.48.1.399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurel C., Javot H., Lauvergeat V., Gerbeau P., Tournaire C., Santoni V., et al. (2002). Molecular physiology of aquaporins in plants. Int. Rev. Cytol. 215 105–148. 10.1016/S0074-7696(02)15007-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurel C., Verdoucq L., Luu D.-T. T., Santoni V. (2008). Plant aquaporins: membrane channels with multiple integrated functions. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 59 595–624. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick A. J., Watt D. A., Cramer M. D. (2009). Supply and demand: sink regulation of sugar accumulation in sugarcane. J. Exp. Bot. 60 357–364. 10.1093/jxb/ern310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milne R. J., Byrt C. S., Patrick J. W., Grof C. P. L. (2013). Are sucrose transporter expression profiles linked with patterns of biomass partitioning in Sorghum phenotypes? Front. Plant Sci. 4:223 10.3389/fpls.2013.00223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milne R. J., Offler C. E., Patrick J. W., Grof C. P. L. (2015). Cellular pathways of source leaf phloem loading and phloem unloading in developing stems of Sorghum bicolor in relation to stem sucrose storage. Funct. Plant Biol. 42 957–970. 10.1071/FP15133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitani N. (2005). Uptake system of silicon in different plant species. J. Exp. Bot. 56 1255–1261. 10.1093/jxb/eri121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno H., Kasuga S., Kawahigashi H. (2016). The sorghum SWEET gene family: stem sucrose accumulation as revealed through transcriptome profiling. Biotechnol. Biofuels 9 1–12. 10.1186/s13068-016-0546-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore P. H. (1995). Temporal and spatial regulation of sucrose accumulation in the sugarcane stem. Aust. J. Plant Physiol 22 661–679. 10.1071/PP9950661 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moore P. H., Botha F. C. (2013). Sugarcane: Physiology, Biochemistry and Functional Biology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Moore P. H., Cosgrove D. J. (1991). Developmental changes in cell and tissue water relations parameters in storage parenchyma of sugarcane. Plant Physiol. 96 794–801. 10.1104/pp.96.3.794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosa K. A., Kumar K., Chhikara S., Mcdermott J., Liu Z. J., Musante C., et al. (2012). Members of rice plasma membrane intrinsic proteins subfamily are involved in arsenite permeability and tolerance in plants. Transgenic Res. 21 1265–1277. 10.1007/s11248-012-9600-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papini-Terzi F. F. S., Rocha F. R. F., Vencio R. R. Z., Felix J. J. M., Branco D. S., Waclawovsky A. J. A., et al. (2009). Sugarcane genes associated with sucrose content. BMC Genomics 10:120 10.1186/1471-2164-10-120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick J. W. (1997). Phloem unloading: Sieve element unloading and post-sieve element transport. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 48 191–222. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.48.1.191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick J. W., Botha F. C., Birch R. G. (2013). Metabolic engineering of sugars and simple sugar derivatives in plants. Plant Biotechnol. J. 11 142–156. 10.1111/pbi.12002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Péret B., Li G., Zhao J., Band L. R., Voß U., Postaire O., et al. (2012). Auxin regulates aquaporin function to facilitate lateral root emergence. Nat. Cell Biol. 14 991–998. 10.1038/ncb2573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer T. W., Bitzer M. J., Toy J. J., Pedersen J. F. (2010). Heterosis in sweet sorghum and selection of a new sweet sorghum hybrid for use in syrup production in appalachia. Crop Sci. 50 1788–1794. 10.2135/cropsci2009.09.0475 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rae A. L., Grof C. P. L., Casu R. E. (2005). Sucrose accumulation in the sugarcane stem: pathways and control points for transport and compartmentation. Field Crop. Res. 92 159–168. 10.1016/j.fcr.2005.01.027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rae A. L., Jackson M. A., Nguyen C. H., Bonnett G. D. (2009). Functional specialization of vacuoles in sugarcane leaf and stem. Trop. Plant Biol. 2 13–22. 10.1007/s12042-008-9019-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy P. S., Rao T. S. R. B., Sharma K. K., Vadez V. (2015). Genome-wide identification and characterization of the aquaporin gene family in Sorghum bicolor (L.). Plant Gene 1 18–28. 10.1016/j.plgene.2014.12.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reinders A., Sivitz A. B., Starker C. G., Gantt J. S., Ward J. M. (2008). Functional analysis of LjSUT4, a vacuolar sucrose transporter from Lotus japonicus. Plant Mol. Biol. 68 289–299. 10.1007/s11103-008-9370-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohwer J. M., Botha F. C. (2001). Analysis of sucrose accumulation in the sugar cane culm on the basis of in vitro kinetic data. Biochem. J. 358 437–445. 10.1042/bj3580437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai J., Ishikawa F., Yamaguchi T., Uemura M., Maeshima M. (2005). Identification of 33 rice aquaporin genes and analysis of their expression and function. Plant Cell Physiol. 46 1568–1577. 10.1093/pcp/pci172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmalstig J. G., Cosgrove D. J. (1990). Coupling of solute transport and cell expansion in pea stems. Plant Physiol. 94 1625–1633. 10.1104/pp.94.4.1625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuurmans J. A. M., van Dongen J. T., Rutjens B. P. W., Boonman A., Pieterse C. M. J., Borstlap A. C. (2003). Members of the aquaporin family in the developing pea seed coat include representatives of the PIP, TP and NIP subfamilies. Plant Mol. Biol. 53 655–667. 10.1023/B:PLAN.0000019070.60954.77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siefritz F., Biela A., Eckert M., Otto B., Uehlein N., Kaldenhoff R. (2001). The tobacco plasma membrane aquaporin NtAQP1. J. Exp. Bot. 52 1953–1957. 10.1093/jexbot/52.363.1953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slewinski T. L. (2011). Diverse functional roles of monosaccharide transporters and their homologs in vascular plants: a physiological perspective. Mol. Plant 4 641–662. 10.1093/mp/ssr051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slewinski T. L. (2012). Non-structural carbohydrate partitioning in grass stems: a target to increase yield stability, stress tolerance, and biofuel production. J. Exp. Bot. 63 4647–4670. 10.1093/jxb/ers124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somerville C., Youngs H., Taylor C., Davis S. C., Long S. P. (2010). Feedstocks for lignocellulosic biofuels. Science. 329 790–792. 10.1126/science.1189268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spyropoulos I. C., Liakopoulos T. D., Bagos P. G., Hamodrakas S. J. (2004). TMRPres2D: High quality visual representation of transmembrane protein models. Bioinformatics 20 3258–3260. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano J., Wada M., Ludewig U., Schaaf G., Von Wirén N., Fujiwara T. (2006). The Arabidopsis major intrinsic protein NIP5; 1 is essential for efficient boron uptake and plant development under boron limitation. Plant Cell 18 1498–1509. 10.1105/tpc.106.041640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarpley L., Vietor D. M., Tarpley L., Vietor D., Miller F., Guimarães C., et al. (2007). Compartmentation of sucrose during radial transfer in mature sorghum culm. BMC Plant Biol. 7:33 10.1186/1471-2229-7-33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Törnroth-Horsefield S., Wang Y., Hedfalk K., Johanson U., Karlsson M., Tajkhorshid E., et al. (2006). Structural mechanism of plant aquaporin gating. Nature 439 688–694. 10.1038/nature04316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tournaire-Roux C., Sutka M., Javot H. H., Gout E. E., Gerbeau P., Luu D.-T. T., et al. (2002). Cytosolic pH regulates root water transport during anoxic stress through gating of aquaporins. Nature 425 187–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turgeon R. (2010). The puzzle of phloem pressure. Plant Physiol. 154 578–581. 10.1104/pp.110.161679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uehlein N., Lovisolo C., Siefritz F., Kaldenhoff R. (2003). The tobacco aquaporin NtAQP1 is a membrane CO2 pore with physiological functions. Nature 425 734–737. 10.1038/nature02027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viola R., Roberts A. G., Haupt S., Gazzani S., Hancock R. D., Marmiroli N., et al. (2001). Tuberization in potato involves a switch from apoplastic to symplastic phloem unloading. Plant Cell 13 385–398. 10.1105/tpc.13.2.385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel J. (2008). Unique aspects of the grass cell wall. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 11 301–307. 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waclawovsky A. J., Sato P. M., Lembke C. G., Moore P. H., Souza G. M. (2010). Sugarcane for bioenergy production: an assessment of yield and regulation of sucrose content. Plant Biotechnol. J. 8 263–276. 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2009.00491.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh K. B., Sky R. C., Brown S. M. (2005). The anatomy of the pathway of sucrose unloading within the sugarcane stalk. Funct. Plant Biol. 32 367–374. 10.1071/FP04102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei W. X., Alexandersson E., Golldack D., Miller A. J., Kjellborn P. O., Fricke W. (2007). HvPIP1;6 a barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) plasma membrane water channel particularly expressed in growing compared with non-growing leaf tissues. Plant Cell Physiol. 48 1132–1147. 10.1093/pcp/pcm083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welbaum G. E., Meinzer F. C. (1990). Compartmentation of solutes and water in developing sugarcane stalk tissue. Plant Physiol. 93 1147–1153. 10.1104/pp.93.3.1147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welbaum G. E., Meinzer F. C., Grayson R. L., Thornham K. T. (1992). Evidence for the consequences of a barrier to solute diffusion between the apoplast and vascular bundles in sugarcane stalk tissue. Funct. Plant Biol. 19 611–623. [Google Scholar]

- Werner D., Gerlitz N., Stadler R. (2011). A dual switch in phloem unloading during ovule development in Arabidopsis. Protoplasma 248 225–235. 10.1007/s00709-010-0223-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingenter K., Schulz A., Wormit A., Wic S., Trentmann O., Hoermiller I. I., et al. (2010). Increased activity of the vacuolar monosaccharide transporter TMT1 alters cellular sugar partitioning, sugar signaling, and seed yield in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 154 665–677. 10.1104/pp.110.162040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood R., Patrick J. W., Offler C. E. (1994). The cellular pathway of short-distance transfer of photosynthates and potassium in the elongating stem of Phaseolus vulgaris L. Stem anatomy, solute transport and pool sizes. Ann. Bot. 73 151–160. 10.1006/anbo.1994.1018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yonekura-Sakakibara K., Saito K. (2013). Transcriptome coexpression analysis using ATTED-II for integrated transcriptomic/metabolomic analysis. Methods Mol. Biol. 1011 317–326. 10.1007/978-1-62703-414-2_25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelazny E., Borst J. W., Muylaert M., Batoko H., Hemminga M. A., Chaumont F. (2007). FRET imaging in living maize cells reveals that plasma membrane aquaporins interact to regulate their subcellular localization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 12359–12364. 10.1073/pnas.0701180104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W.-H., Zhou Y., Dibley K. E., Tyerman S. D., Furbank R. T., Patrick J. W., et al. (2007). Nutrient loading of developing seeds. Funct. Plant Biol. 34 314–331. 10.1071/FP06271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X. Q., Mitani N., Yamaji N., Shen R. F., Ma J. F. (2010). Involvement of silicon influx transporter OsNIP2;1 in selenite uptake in rice. Plant Physiol. 153 1871–1877. 10.1104/pp.110.157867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.