Invasive aspergillosis (IA) is the most common filamentous fungal infection in immunocompromised patients (16, 51). However, not all Aspergillus species possess the same biologic attributes or even the same antifungal susceptibility patterns. Aspergillus fumigatus and A. flavus are the species most commonly associated with IA (67, 99), and the frequency of IA caused by A. terreus varies from 3 to 12.5% (40, 67, 99, 100). Present data from in vitro studies (90) and in vivo studies (101) and a retrospective analysis of contemporary clinical data (86) indicate that IA due to A. terreus may be resistant to amphotericin B and associated with a high rate of mortality. However, the optimal therapy for infections caused by this emerging pathogen is uncertain.

Our clinical understanding of this historically difficult to treat pathogen is meager. There are various individual reports of invasive A. terreus disease, but most appear as isolated clinical cases. Additionally, there are cases aggregated in larger clinical studies for which the details of the specific Aspergillus species were not reported. The only review devoted to invasive A. terreus infection was a 12-year retrospective analysis of 13 cases confined to a single medical center from 1985 to 1996 (36). We present a review of 60 clinical cases of invasive A. terreus infection, as well as 28 in vitro studies and 9 reports of animal models of A. terreus infection, that occurred or that were published from 1966 to 2003 to better understand the characteristics and therapy for this emerging non-A. fumigatus Aspergillus species.

We searched the English-language literature through the MEDLINE database from 1966 to December 2003 for in vitro and in vivo studies of A. terreus as well as clinical case reports using the keywords “Aspergillus terreus” and cross-references. Additionally, we also reviewed abstracts from worldwide infectious diseases conferences held from 1999 to 2003 (Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, Focus on Fungal Infections) for studies in which A. terreus was specifically analyzed. We excluded articles and abstracts in which A. terreus was one of several Aspergillus species tested yet in which the specific results or outcomes were not stratified by species to allow comparison. Inclusion criteria for the review of in vitro studies included antifungal susceptibility testing of A. terreus, including a specific stratification of results if multiple Aspergillus species were tested. Inclusion criteria for the review of clinical studies consisted of proven or probable IA caused by A. terreus, as proven by culture and as defined according to the joint guidelines of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and the Mycoses Study Group of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (4).

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF A. TERREUS

The previously largest review of A. terreus infections examined the microbiology records of one center from 1985 to 1996 and discovered 11 cases of primary invasive pulmonary aspergillosis and 2 cases of primary Aspergillus peritonitis (36). The authors compared the 11 cases of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis with the findings from 19 published studies from that 12-year time period. At the authors' institution A. terreus was the third most common Aspergillus species and accounted for 13 of 133 (9.8%) of cases of IA. A. terreus was the most frequent cause of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in patients with leukemia (54.5%) and the most common species in patients with neutropenia (63.6%) and patients with neutropenia for the longest duration (median, 27 days). A. terreus caused the greatest mortality from invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (10 of 11 patients died) and the largest percentage of cases of aspergillosis not diagnosed until postmortem examination (60%).

A review of 1,477 separate Aspergillus-positive cultures from 24 medical centers found that A. fumigatus was the most frequently isolated Aspergillus species, causing 67% of cases of IA (67). A. flavus accounted for 16% of the strains causing IA, followed by A. niger (5%) and A. terreus (3%). When presentations were stratified by disease distributions, although A. fumigatus was the leading pathogen causing IA, A. fumigatus was also the predominant cause of chronic necrotizing aspergillosis, aspergilloma, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, colonization, and contamination. In fact, only 19% of A. fumigatus isolates were involved in IA. In contrast, although A. terreus is an uncommon isolate, it was strongly associated with IA (8 of 8 positive cultures), while A. flavus was predominantly associated with IA (41 of 49 positive cultures [83%]).

One study used randomly amplified polymorphic DNA analysis-PCR to analyze 43 clinical A. terreus isolates from 28 patients from 1996 to 2001 at a major medical center and found great strain diversity (5). Another study used the same molecular biology-based techniques and concluded that patients with cystic fibrosis are likely colonized with A. terreus from the soil and air prior to hospitalization (12). A 3-year prospective study that sampled the air, environmental surfaces, and hospital water of a major medical center found A. terreus present in patient showerheads with the same frequency as A. fumigatus, and half of the hospital water storage tanks contained A. terreus or A. fumigatus (1). Volumetric air sampling of one military medical center revealed that A. niger was the most commonly found Aspergillus species (38%), followed by A. terreus (26%). However, only A. terreus was recovered from each of four sampling sites, and only A. terreus and A. niger were consistently recovered throughout the 4-month sampling period (44).

BIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF A. TERREUS

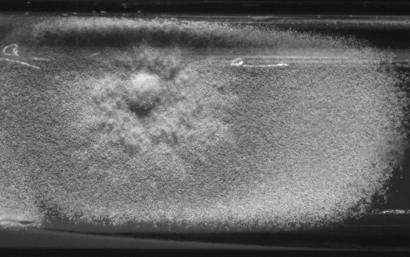

A. terreus is widespread in warm arable soils, especially in the southern and southwestern United States. It is generally less common in the forest than cultivated soils and is rarely found in the acidic forest soils from the colder temperate zone (75). A. terreus is distinguished from the more common Aspergillus species by its compactly columnar, cinnamon to tan (sometimes yellowish to orange-brown) conidial heads, and tan to yellow coloration on the colony reverse (Fig. 1) (75). A. terreus, A. carneus, A. flavipes, and A. niveus are unique among Aspergillus species, as they produce morphologically distinct lateral conidia (aleurioconidia) in infected tissue (71, 72). These conidia are usually attached directly to a very short lateral extension of the hyphae and are generally borne singly, although multiple conidia can be formed from a single locus (64, 95). In one study the metabolic and growth rates of a human A. terreus isolate were double those of two soil isolates when the isolates were grown at 37°C, and the human isolate was more than 1,000-fold more virulent than the soil isolates in a murine model (76), confirming earlier work on relative virulence in studies with animals (72).

FIG. 1.

A. terreus from a 3-week-old primary culture of a lung biopsy specimen on inhibitory mold agar.

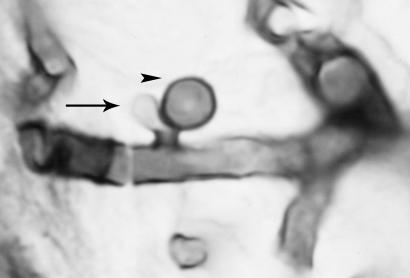

The diagnosis of aspergillosis by blood culture is rare, and one recent review concluded that only 32 cases of true Aspergillus fungemia have been correctly documented in patients with hematological disease (27). Disease caused by A. fumigatus is rarely documented by blood culture (19, 67). In general, the Aspergillus hyphal mass that develops in the lumen during angioinvasion remains in place until the force of blood flow causes hyphal breakage, which then allows the mass to circulate. The likelihood that a blood culture would capture these irregularly and infrequently discharged units is small. This difficulty in detection of A. fumigatus in blood cultures stands in contrast to the ease of detection of other angioinvasive filamentous fungi (e.g., Fusarium species, Paecilomyces lilacinus, Scedosporium prolificans, and Acremonium species) that have the ability to discharge a steady series of unicellular spores into the bloodstream, which are more likely to be captured in a blood sample. This ability to sporulate in tissue and blood has been termed adventitious sporulation (80). As A. terreus also displays adventitious sporulation, histopathology and KOH examination of these spores also can allow the rapid, presumptive identification of A. terreus (Fig. 2) (49, 72). Therefore, a blood culture positive for A. terreus or another fungus that demonstrates adventitious sporulation should not be ignored (81).

FIG. 2.

A mature conidium (arrowhead) displaced by the formation of a second conidium (arrow). The organism was grown from a biopsy specimen from a lip lesion from a neutropenic patient and stained with silver.

IN VITRO ANTIFUNGAL SUSCEPTIBILITY DATA

A total of 28 in vitro analyses testing 418 A. terreus isolates met our inclusion criteria (Table 1). In the largest in vitro study of 101 A. terreus clinical isolates (90), the 48-h amphotericin B MICs were ≤1 μg/ml for less than 2% of the isolates, and the mean MIC was 3.37 μg/ml. The minimum fungicidal concentrations (MFCs) were elevated beyond the levels of amphotericin B deoxycholate achievable in serum, with a mean 24-h MFC of 7.03 μg/ml and a mean 48-h MFC of 13.4 μg/ml. The 48-h MIC at which 90% of the isolates were inhibited (MIC90) was 4 μg/ml for amphotericin B, with an MFC at which 90% of isolates were inhibited of 16 μg/ml, implying that A. terreus was resistant to the fungicidal properties of amphotericin B in vitro. In one study (69) only 25% of A. terreus isolates were inhibited by amphotericin B (MIC ≤ 1 μg/ml), whereas 92% of other Aspergillus species isolates were inhibited by amphotericin B. In another study (24) the largest difference in MICs and MFCs seen for all Aspergillus species tested was for A. terreus, for which only 34% (10 of 29 pairs) of the MICs and MFCs were within 2 dilutions. An additional study (52) investigated the activity of amphotericin B against A. terreus suspended in tissue culture medium and showed that only the highest concentration tested (80 μg/ml) was fungistatic against A. terreus.

TABLE 1.

Mean 48-h MIC90s and MFCs for A. terreus from in vitro studiesa

| Reference | No. of isolates | Analysis method | MIC90 (μg/ml [MFC {μg/ml}])

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMB | ABLC | ABCD | L-AMB | L-Nys | ITZ | VCZ | PCZ | RCZ | ALB | CAS | AND | TER | |||

| 61 | 7 | Otherb | 8.8 (>16) | 0.07 | 0.05 | ||||||||||

| 22 | 2 | M27-Ab | ND (1.0) | ||||||||||||

| 45 | 9 | M27-P | ≥2 | ||||||||||||

| 90 | 101 | M27-Ab | 3.37 (13.4) | 0.22 (17.4c) | |||||||||||

| 14 | 20 | M38-P | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||

| 91 | 10 | M27-A | 2 | 0.25 | |||||||||||

| 60 | 8 | Otherb | 5.7 (32) | 32 (32) | 20.7 (32) | 32 (32) | 8.7 (32) | 0.1 (14.7) | |||||||

| 70 | 1 | M38-P | 0.5 | ||||||||||||

| Flattery et al.e | 3 | M38-Tb | 4 | 0.06 | 20.2 (0.2) | ||||||||||

| Gavalda et al.f | 3 | M38-P | >8 | ||||||||||||

| 24 | 29 | M38-P | 4 (>8) | 0.25 (2) | 1.0 (>8) | ||||||||||

| Sutton et al.g | 50 | M38-P | 32 | ||||||||||||

| 47 | 5 | M27-P | (1) | (0.5) | |||||||||||

| 53 | 1 | M38-P | 2-4 | 0.5-1 | |||||||||||

| 56 | 12 | Other | 4 | 0.5 | 0.25 | ||||||||||

| 2 | 9 | M38-Pb | 0.5 | ||||||||||||

| Troke et al.h | 14 | M38-P | 4 | 0.25 | 1.0 | ||||||||||

| 3 | 3 | M38-P1 | 0.06-0.125 | 1->16 | |||||||||||

| 58 | 2 | Other | 2-4 (32) | 0.125 (2) | 0.062-0.125 | ||||||||||

| 46 | 7 | Other | 1.25 | 0.78 | 0.39 | ||||||||||

| 66 | 10 | M38-P | 0.5-1 | 32-64 | |||||||||||

| 69 | 8 | M38-Pd | 2 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.25 | ||||||||

| Cuenca-Estrella et al.i | 20 | M38-Pb | 0.90 | ||||||||||||

| Espinell-Ingroff et al.j | 42 | M38-P | 4.0 | 0.25 | 0.50 | ||||||||||

| 23 | 15 | M38-A | 1.4b | 0.14b | 0.27b | ||||||||||

| 68 | 19 | M38-A | 0.5 | 0.5 | |||||||||||

| 6 | 7 | M38-P | 0.5-1 | 0.25-0.5 | |||||||||||

| Lewis et al.k | 1 | M38-A | 1 (2) | 1 (8) | 0.25 (4) | ||||||||||

Abbreviations: AMB, Amphotericin B; ABLC, amphotericin B lipid complex; ABCD, amphotericin B colloidal dispersion; L-AMB, liposomal amphotericin B; L-Nys, liposomal nystatin; ITZ, itraconazole; VCZ, voriconazole; PCZ, posaconazole; RCZ, ravuconazole; ALB, albendazole; CAS, caspofungin; AND, anidulafungin; TER, terbinafine; ND, not determined.; M27-A, M27-P, M38-P, M-38T, and M38-A, standard methods of the NCCLS.

Values are geometric means.

The voriconazole MICs for only 51 isolates were tested.

Values are MIC50s.

A. M. Flattery, P. S. Hicks, A. Wilcox, and H. Rosen, Abstr. 40th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. 936, 2000.

J. Gavalda, M. Martin, P. Lopez, M. Cuenca-Estrella, X. Gomis, J. Ramirez, J. Ramirez-Tudela, and A. Pahissa, Abstr. 41st Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. J-107, 2001.

D. A. Sutton, M. G. Rinaldi, and A. W. Fothergill, Abstr. 41st Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. J-113, 2001.

P. F. Troke, A. Espinel-Ingroff, E. M. Johnson, and H. Schlamm, Abstr. 41st Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. J-820, 2001.

M. Cuenca-Estrella, E. Mellado, A. Gomez-Lopez, A. Monzon, and J. L. Rodriguez-Tudela, Abstr. 42nd Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. M-1514, 2002.

A. Espinel-Ingroff, A., E. Johnson, and P. Troke, Abstr. 42nd Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. M-1518, 2002.

R. E. Lewis, N. P. Wiederhold, and M. E. Klepser, Abstr. 43rd Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. M-1255, 2003.

In another study (101), amphotericin B activity was assessed in vitro by MIC determination, a microbicidal time-kill assay, a colorimetric 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay of hyphal damage, and sterol composition analysis of the fungal cell membrane. Additionally, the monocyte-macrophage host response to two different Aspergillus species was analyzed. This in vitro work revealed a loss of concentration-dependent killing of A. terreus by amphotericin B in a time-kill assay, while killing continued for A. fumigatus. The MTT assay also showed that A. terreus is resistant to amphotericin B-induced hyphal damage after 6 h (101).

The newer agents showed greater in vitro activity than amphotericin B. For instance, in one study of 16 A. terreus isolates (17), voriconazole, posaconazole, ravuconazole, and caspofungin inhibited all isolates at ≤0.5 μg/ml. Of all Aspergillus species tested, A. terreus was the most susceptible to posaconazole, with an MIC range of 0.03 to 0.125 μg/ml. A. terreus was also the species most susceptible to itraconazole, with an MIC range of 0.06 to 0.125 μg/ml (61). In another study (22), the MICs for two A. terreus isolates were <0.03 to 0.5 μg/ml for posaconazole, 0.5 μg/ml for caspofungin, and <0.03 μg/ml for anidulafungin. In another study (90), the voriconazole 48-h mean MIC for A. terreus was within levels achievable in serum (0.22 μg/ml) and the 48-h MIC90 was 0.25 μg/ml. The mean MFCs at 24 and 48 h were 5.39 and 17.4 μg/ml, respectively (90), and thus, voriconazole was shown to be fungistatic only for this Aspergillus species, despite reports of fungicidal activity against other Aspergillus species. One large review (25) of the in vitro spectrum of activity of voriconazole included a compilation of 139 A. terreus isolates from previously published reports and reported that the drug had excellent antifungal activity.

Testing of the activities of antifungal combinations against A. terreus in vitro has shown some positive interactions. One in vitro study (66) showed that voriconazole and caspofungin have synergistic activity against Aspergillus spp., including 10 clinical isolates of A. terreus. Another study (58) revealed that terbinafine and itraconazole as well as terbinafine and fluconazole had synergistic activities against two isolates of A. terreus and that amphotericin B and caspofungin had indifferent or slightly additive interactions against three isolates of A. terreus (3). The activity of the combination of amphotericin B and anidulafungin against A. terreus was indifferent, and that of the combination of amphotericin B and micafungin was slightly additive (L. Ostrosky-Zeichner, M. Matar, V. L. Paetznick, J. R. Rodriguez, E. Chen, and J. H. Rex, Abstr. 42nd Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. M-1816, 2002). While synergy was observed with nikkomycin Z-micafungin against A. fumigatus, this combination showed indifference against A. terreus (11).

In summary, in vitro studies of the susceptibility of A. terreus to amphotericin B generally reveal high MICs without the potential for fungicidal activity at concentrations safely achievable in plasma. On the basis of these in vitro data, one would hypothesize that the polyene would also demonstrate failure in vivo (45). The limited testing with echinocandin antifungals, generally caspofungin (Table 1), and azole antifungals show that they clearly possess MICs lower than those of amphotericin B. Unfortunately, data with which to specifically compare the activities of the individual azoles against A. terreus on a larger scale were limited.

ANIMAL MODELS

There have been few animal models of A. terreus infections. An intracheal instillation model of murine and rabbit pulmonary aspergillosis showed the ability of A. terreus to produce disease (62). One murine aspergillosis model was used to study 14 different Aspergillus species and reported that the pathogenicity of A. terreus was average among those of the Aspergillus species tested (26). The aleurioconidia of A. terreus have been demonstrated in murine brain tissue after intravenous inoculation, demonstrating endogenous sporulation in nonnecrotic host tissue and its blood vessels. This finding is potentially clinically relevant, as in cases of human disseminated disease the aleurioconidia are not able to gain access to vessels in large numbers, but aleurioconidia were observed in blood vessels in this animal model. In fact, in one isolate the aleurioconidial preparation was approximately 10 times as infective as the conidial suspension (72).

In a model of disseminated A. terreus infection in immunocompetent mice, the mice were treated with amphotericin B (4.5 mg/kg of body weight once daily intraperitoneally) or itraconazole (50 or 100 mg/kg/day in two oral daily doses), and each drug was continued for 10 days beginning 2 h after infection. The MICs, according to the NCCLS M27-A standards, for the infecting A. terreus clinical isolate were 2 μg/ml for amphotericin B and 1 μg/ml for itraconazole. Treatment with itraconazole at 50 and 100 mg/kg/day resulted in survival rates of 70% (7 of 10) and 90% (9 of 10), respectively. All mice (10 of 10) receiving amphotericin B died within 12 days, which was the same as the death rate for controls receiving glucose injections. Itraconazole significantly reduced the fungal burdens in the kidneys and the brain in a dose-dependent fashion, but amphotericin B treatment was no better than no treatment at reducing the tissue fungal burden. Sterol analysis of the infecting isolate showed an ergosterol content of 85%, which is similar to what has been described for A. fumigatus isolates that are susceptible to amphotericin B in vivo. This finding suggests that the amphotericin B resistance observed in this murine model was not related to a lack of the ergosterol target in the cell membranes (13).

A model of A. terreus infection in temporarily neutropenic mice showed that treatment with either amphotericin B deoxycholate or liposomal amphotericin B was ineffective (102). However, treatment with itraconazole or micafungin prolonged the length of survival over that for the untreated controls. The colony counts in the lungs and livers of mice with this A. terreus infection were >100-fold higher than the colony counts in the lungs and livers of mice with A. fumigatus infections evaluated in parallel with identical treatment arms, highlighting the differences in the treatments for infections caused by the two species. Another model of systemic A. terreus infection in mice showed that the survival rate for mice treated with saperconazole was superior to that for the untreated controls, but this azole did not reduce the kidney fungal burden compared to that in the controls (32).

A model of systemic A. terreus infection in neutropenic mice compared therapy with posaconazole, caspofungin, or amphotericin B at various doses (J. R. Graybill, A. W. Fothergill, S. Hernandez, L. K. Najvar, and R. Bocanegra, Focus Fungal Infect. 13, abstr. P-62, 2003). In three studies amphotericin B was not effective when it was administered at 6 mg/kg intraperitoneally daily, and amphotericin B reduced the semiquantitative fungal burdens in the spleens to levels lower than those in the controls only when it was administered at 10 mg/kg every other day. Caspofungin (15 mg/kg/day) inconsistently prolonged survival and reduced the counts in the spleens to levels lower than those in the controls, but lower doses of caspofungin (0.5, 5, and 10 mg/kg daily) were completely ineffective. Posaconazole at 20 mg/kg, but not at 10 mg/kg, prolonged survival, while both doses reduced the fungal burdens in the lungs but not in the spleens. Another murine model with DBA2/J mice and a range of caspofungin doses showed that the drug achieved a 50% effective reduction in the fungal burden in the kidneys when it was administered at 0.05 mg/kg/day, a value higher than that required to achieve the same result against A. flavus or A. nidulans (E. J. Simmons, G. Abruzzo, J. Bowman, C. Douglas, A. M. Flattery, C. Gill, M. Hsu, A. Misura, B. Pikounis, and J. Kahn, Abstr. 43rd Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. M-1251, 2003).

The in vivo analysis with the most number of endpoints compared A. fumigatus and A. terreus invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in a persistently neutropenic rabbit model (101). Rabbits received amphotericin B deoxycholate (0.5 mg/kg/day), liposomal amphotericin B (5 mg/kg/day), itraconazole (6 or 20 mg/kg/day), or posaconazole (6 or 20 mg/kg/day). The histology of the lung tissues of rabbits infected with A. terreus and treated with amphotericin B were indistinguishable from that of the lung tissues of untreated controls; however, aleurioconidia were seen along the lateral walls of hyphal elements invading the lung tissue infected with A. terreus. There was also no difference in the galactomannan levels in the amphotericin B-treated rabbits compared to those in the controls. Survival was statistically improved by treatment with posaconazole or itraconazole at 20 mg/kg/day, while the rate of survival of rabbits treated with amphotericin B was similar to that of the untreated controls. The study observed that while A. terreus was more resistant to amphotericin B in vivo, it appeared to be less virulent than A. fumigatus in vivo, such that untreated rabbits infected with A. terreus survived longer than those infected with A. fumigatus. Sterol analysis demonstrated decreasing levels of membrane ergosterol content with increasing MICs for A. terreus isolates.

This collection of data from studies that have used animal models are concordant with the in vitro observations that amphotericin B is an ineffective clinical antifungal option. The limited testing of echinocandins in vivo reveals that this group of drugs has inconsistent activity in terms of decreasing mortality or fungal burden. However, the azoles appear to be the most active group of drugs against this particular Aspergillus species in experimental animal models, and this finding mirrors the data from in vitro studies.

CLINICAL REPORTS

A. terreus has been recognized as a cause of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (43, 98), aspergilloma (38, 39, 43), onychomycosis (63, 103), aural cavity disease (20, 31, 73, 89, 93), subcutaneous abscesses (9, 88), and keratitis (78, 84). Many factors influence the overall clinical efficacy of treatment for IA, including the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the antifungal agent used, the host's immune status, the site of infection, and the virulence of the pathogen. For example, a comparison of 20 patients with A. terreus infections and 23 patients with A. fumigatus infections revealed similar risk factors and overall responses (complete or partial) to antifungal therapy (15 and 17%, respectively). Only one of six patients reported to have persistent neutropenia and A. fumigatus infections responded to treatment, while none of four patients reported to have A. terreus infections responded to treatment (R. Hachem, D. Kontoyiannis, M. Boktour, C. Afif, C. Cooksley, I. Chatzinikolaou, and I. Raad, Program Abstr. 40th Annu. Meet. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am., abstr. 338, 2002).

We reviewed a total of 60 previously published clinical invasive A. terreus infections described in 39 reports published from 1968 to 2003 (Table 2). Interestingly, 75% (45 of 60) of those clinical cases were reported in the last 14 years (1990 to 2003). The ages of the patients ranged from 1 month to 80 years, and 23% (14 of 60) of the patients were reported to be neutropenic (absolute neutrophil counts, <500 cells/μl) at the time of diagnosis. While pulmonary disease makes up the vast majority of clinical presentations in other studies, only 45% (27 of 60) of these patients with A. terreus infections had pulmonary infections, while 18% (11 of 60) had endocarditis and 17% (10 of 60) had a bone or joint infection.

TABLE 2.

Previously published clinical reports of invasive A. terreus infectiona

| Reference | Yr | Age (yr)/sex | Underlying disease, condition, or characteristic | Neutropenic at diagnosis | Type of IA | Source of culture | Antifungal treatment | Patient outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 54 | 1968 | 15/M | Mitral valve regurgitation | No | Endocarditis | Autopsy specimen | None | Death |

| 50 | 1969 | 40/M | Immunocompetent | No | Disseminated | Cervical lymph node biopsy specimen | None | Death |

| 82 | 1977 | 42/F | Portal hepatofibrosis, IVDA | No | Vertebral osteomyelitis | Biopsy specimen | AMB | Improvement |

| 18 | 1980 | 65/M | Porcine valve replacement | No | Endocarditis | Surgical specimen | AMB + 5FC | Death |

| 28 | 1982 | 71/M | Aortofemoral bypass | No | Vertebral osteomyelitis, pseudoaneursym | Biopsy specimen | AMB, surgery | Death |

| 85 | 1982 | 24/F | Heroin addiction | No | Meningitis | CSF culture | AMB | Death |

| 43 | 1982 | 53/F | Rheumatic heart disease, valve replacement | No | Endocarditis | Autopsy | None | Death |

| 95 | 1983 | 23/M | AML | No | Disseminated | Lung biopsy specimen | AMB + 5FC | Death |

| 92 | 1983 | 24/F | VSD, right aortic sinus aneursym rupture | No | Endocarditis | Surgical specimen | AMB + 5FC, surgery | Death |

| 8 | 1986 | 60/M | AML | Yes | Pulmonary | Transbronchial biopsy specimen | AMB | Death |

| 57 | 1988 | 70/F | Lymphoma | No | Pulmonary | Transbronchial biopsy specimen | AMB | Death |

| 33 | 1989 | 80/F | Immune thrombocytopenia | No | Pulmonary | BAL specimen | AMB | Death |

| 33 | 1989 | 28/M | Myelodysplastic syndrome, BMT | Yes | Disseminated | Sputum, pericardial fluid, urine | AMB + ketoconazole | Death |

| 33 | 1989 | 65/F | CLL | Yes | Disseminated | NR | NR | Death |

| 7 | 1989 | 0/F | Truncus arteriosus | No | Endocarditis | Autopsy | None | Death |

| 41 | 1990 | 37/F | SLE | No | Pulmonary | Autopsy | None | Death |

| 79 | 1990 | 58/F | Aortic stenosis, valve replacement | No | Disseminated | Autopsy | AMB | Death |

| 37 | 1991 | 65/F | CLL | No | Disseminated | BAL specimen, skin specimen culture | AMB | Death |

| 55 | 1992 | 46/M | AIDS | No | Pulmonary | Autopsy | None | Death |

| 74 | 1992 | 41/M | AIDS, lymphoma | No | Pulmonary | Sputum, autopsy | AMB | Death |

| 64 | 1992 | 72/M | NIDDM | No | Septic bursitis | Joint fluid | Surgery | Improvement |

| 15 | 1993 | 50/M | Cataract extraction | No | Endophthalmitis | Vitrectomy biopsy specimen | Ketoconazole, intravitreal AMB | Improvement |

| 100 | 1993 | 2/F | Aplastic anemia, BMT | NR | Pulmonary, skin | Clinical evidence | AMB, Rifampin, surgery | Death |

| 100 | 1993 | 18/F | Aplastic anemia, BMT | NR | Skin | Clinical evidence | AMB, 5FC, surgery | Death |

| 100 | 1993 | 2/F | T-cell deficiency | NR | Liver | Autopsy | AMB, 5FC | Death |

| 29 | 1993 | 21/M | ALL, allogeneic BMT | No | Pulmonary | Biopsy | AMB + miconazole and then itraconazole | Improvement |

| 96 | 1993 | 36/M | Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, autologous BMT | No | Pulmonary | Tranchbronchial biopsy specimen | AMB + 5FC + aerosolized AMB | Death |

| 96 | 1993 | 23/M | ALL, allogeneic BMT | Yes | Disseminated | Autopsy | AMB | Death |

| 96 | 1993 | 27/M | CML, allogeneic BMT | No | Disseminated | BAL specimen | AMB | Death |

| 96 | 1993 | 41/M | AML, allogeneic BMT | No | Disseminated | Cerebral biopsy specimen, autopsy | AMB | Death |

| 35 | 1993 | NR | Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma | No | Pulmonary | NR | AMB | Death |

| 35 | 1993 | NR | Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma | No | Disseminated | Blood culture, BAL specimen | AMB | Death |

| 59 | 1994 | 5/F | Aplastic anemia | Yes | Pulmonary, sinus | Maxillary sinus puncture | AMB | Death |

| 42 | 1995 | 15/F | Aortic stenosis and valvotomy | No | Aortic abscess and pseudoaneurysm | Surgical specimen | AMB | Death |

| 77 | 1995 | 40/F | CML, allogeneic BMT | Yes | Pulmonary | Surgical specimen | AMB, itraconazole, surgery | Death |

| 77 | 1995 | 57/M | Cirrhosis, liver transplant | No | Pulmonary | Surgical specimen | AMB, itraconazole, surgery | Improvement |

| 87 | 1997 | 51/M | Hepatic cirrhosis | No | Septic arthritis | Joint fluid | Itraconazole, surgery | Improvement |

| 10 | 1998 | 33/M | CML, PSCT | No | Endocarditis, disseminated | Autopsy specimens | AMB | Death |

| 81 | 1998 | 60/F | ALL | No | Endocarditis, aortal embolization | Multiple blood cultures | AMB, surgery | Death |

| 36 | 1998 | 34/F | Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, autologous PSCT | Yes | Pulmonary | Autopsy | AMB | Death |

| 36 | 1998 | 72/M | AML | Yes | Pulmonary | Autopsy | None | Death |

| 36 | 1998 | 46/F | Chronic hepatitis B, liver transplant | No | Pulmonary | Autopsy | Fluconazole | Death |

| 36 | 1998 | 76/M | AML | Yes | Pulmonary, cutaneous | Skin specimen culture | AMB | Death |

| 36 | 1998 | 1/M | Liver-small bowel transplant | No | Disseminated | Multiple cultures | Fluconazole | Death |

| 13 | 2000 | 54/M | AML | Yes | Pulmonary | BAL specimen | AMB + itraconazole | Improvement |

| 48 | 2000 | NR | AML | No | Pulmonary | Lung biopsy specimen | AMB | Death |

| 48 | 2000 | NR | CLL | No | Disseminated | Tracheal secretion | AMB | Death |

| 48 | 2000 | NR | CLL | No | Pulmonary | Lung biopsy specimen | AMB | Death |

| 48 | 2000 | NR | AML | Yes | Pulmonary | BAL specimen | AMB | Death |

| 48 | 2000 | NR | CLL | No | Disseminated | Tracheal secretion, brain biopsy specimen | AMB | Death |

| 48 | 2000 | NR | AML | Yes | Pulmonary | BAL specimen | AMB | Death |

| 48 | 2000 | NR | Multiple myeloma | Yes | Pulmonary | Lung biopsy specimen | AMB | Death |

| 48 | 2000 | NR | Aplastic anemia | No | Pulmonary | BAL specimen | AMB | Death |

| 48 | 2000 | NR | ALL | Yes | Pulmonary | Lung biopsy specimen | AMB | Death |

| 36 | 2000 | 40/M | AML | No | Pulmonary, vertebral osteomyelitis | BAL and biopsy specimens | AMB + itraconazole, surgery | Improvement |

| 83 | 2000 | 11/M | AML | No | Pulmonary, mycotic aneursym | BAL and biopsy specimens | ABLC + rifampin + aerosolized | Improvement |

| AMB and then itraconazole, surgery | ||||||||

| 65 | 2000 | 37/M | ALL | No | Verterbral osteomyelitis | Biopsy specimen | AMB, surgery | Improvement |

| 97 | 2001 | 33/M | History of pulmonary aspergillosis | No | Sclerosing mediastinitis | Biopsy specimen | AMB | Death |

| 94 | 2001 | 13/M | Common variable immunodeficiency | No | Hepatic abscess | Biopsy | Liposomal AMB + GM-CSF + itraconazole | Improvement |

| 21 | 2002 | 19/F | Biliary atresia | No | Cholangitis | Biliary drainage | ABCD, then itraconazole, and then ABCD | Death |

Abbreviations: M, male; F, female; IVDA, intravenous drug abuser; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; AML, acute myelogenous leukemia; VSD, ventricular septal defect; BMT, bone marrow transplant; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CML, chronic myelogenous leukemia; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; PSCT, peripheral blood stem cell transplant; NIDDM, non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus; NR, not reported; BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage; AMB, amphotericin B; 5FC, flucytosine; ABLC, amphotericin B lipid complex; ABCD, amphotericin B colloidal dispersion.

Consistent with the overall reports of the treatments for IA, amphotericin B monotherapy was used to treat 52% (31 of 60) of cases; this was followed by 17% (10 of 60) of cases in which amphotericin B was administered concurrently with another antifungal and 10% (6 of 60) of cases in which amphotericin B treatment was followed by sequential therapy with another antifungal agent. No therapy was given to 12% (7 of 60) of cases due to postmortem diagnoses, and 10% (6 of 60) were treated with another antifungal agent. In 82% (49 of 60) of cases of A. terreus infection reported, the patient died. Of the 11 reported patients with clinical improvement, only 2 were treated with amphotericin B monotherapy. Eight of the remaining nine reported patients were treated with an azole; one was treated with ketoconazole, one was treated with itraconazole, three were treated with amphotericin-itraconazole, one was treated with amphotericin-miconazole, and two were treated with amphotericin B followed by treatment with itraconazole.

In another review (45) of 29 patients with hematological malignancies who developed IA and who were treated with amphotericin B monotherapy (1.5 mg/kg/day), 31% (9 of 29) had A. terreus infections. The overall rate of mortality from IA was 76% (22 of 29 patients), and all patients infected with isolates for which the amphotericin B MIC was <2 μg/ml survived, while 22 of 24 patients infected with isolates for which the amphotericin B MIC was ≥2 μg/ml died, including all A. terreus-infected patients. The rate of lethality from the A. fumigatus infections (63%) was lower than that from the A. terreus infections (100%). The characteristics of the patients infected with different Aspergillus species were similar; four of nine A. terreus-infected patients were neutropenic at the time of diagnosis, and the neutropenia resolved in two of four patients.

In a recent study analyzing voriconazole as primary therapy for IA (34), 6 cases of A. terreus infection were identified among the 110 infections in which the species were identified at the baseline. Of the total of 391 patients from 95 centers in 19 countries, successful outcomes were achieved for 31.6% of patients who received amphotericin B as primary therapy, whereas the rate of successful outcomes was 52.8% among the patients who received voriconazole as the initial therapy. Unfortunately, the outcomes for those six cases were not stratified, so there are no specific data on A. terreus therapy from the largest aspergillosis treatment trial ever completed. In a contemporary retrospective review (85) of 83 cases of A. terreus infection conducted from 1997 to 2002, patients who were treated with voriconazole at any time during therapy had a significantly lower overall mortality rate at 12 weeks (odds ratio, 0.38; 95% confidence interval, 0.14 to 0.99; P = 0.049) than patients who received other antifungals (chiefly amphotericin B). The patients who received voriconazole as their primary antifungal therapy also had a greater overall survival rate (64.7% [11 of 17 patients]; P = 0.008) than the patients who received amphotericin B.

With the advent of new therapeutic options, the ability to distinguish A. terreus from other Aspergillus species may be important in the development of an effective therapeutic strategy. The synthesis of data from in vitro and animal model studies as well as clinical observations suggests that amphotericin B therapy may not be effective against IA due to A. terreus. This review also describes the largest collection of previously reported A. terreus clinical cases and extends the concept of amphotericin B resistance into the clinical realm, as 7 of the 11 patients reported to have survived received an azole. While no randomized clinical trials specifically analyzing the outcomes of treatments for A. terreus infections have been conducted and only one cohort study has been able to offer conclusions, this review suggests that amphotericin B may not be effective against A. terreus infections and that clinicians should strongly consider using a triazole antifungal against this emerging non-A. fumigatus Aspergillus species.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anaissie, E. J., S. L. Stratton, C. Dignani, R. C. Summerbell, J. H. Rex, T. P. Monson, T. Spencer, M. Kasai, A. Francesconi, and T. J. Walsh. 2002. Pathogenic Aspergillus species recovered from a hospital water system: a 3-year prospective study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 34:780-789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arikan, S., M. Lozano-Chiu, V. Paetznick, and J. H. Rex. 2001. In vitro susceptibility testing methods for caspofungin against Aspergillus and Fusarium isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:327-330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arikan, S., M. Lozano-Chiu, V. Paetznick, and J. H. Rex. 2002. In vitro synergy of caspofungin and amphotericin B against Aspergillus and Fusarium spp. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:245-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ascioglu, S., J. H. Rex, B. de Pauw, J. E. Bennett, J. Bille, F. Crokaert, D. W. Denning, J. P. Donnelly, J. E. Edwards, Z. Erjavec, D. Fiere, O. Lortholary, J. Maertens, J. F. Meis, T. F. Patterson, J. Ritter, D. Selleslag, P. M. Shah, D. A. Stevens, and T. J. Walsh. 2002. Defining opportunistic invasive fungal infections in immunocompromised patients with cancer and hematopoietic stem cell transplants: an international consensus. Clin. Infect. Dis. 34:7-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baddley, J. W., P. G. Pappas, A. C. Smith, and S. A. Moser. 2003. Epidemiology of Aspergillus terreus at a university hospital. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:5525-5529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berthet, N., O. Faure, A. Bakri, P. Ambroise-Thomas, R. Grillot, and J.-F. Brugere. 2003. In vitro susceptibility of Aspergillus spp. clinical isolates to albendazole. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 51:1419-1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhatnagar, N. K., J. P. Dhasmana, G. A. Russell, and S. C. Jordan. 1989. Aspergillus ball thrombus occluding a homograft conduit. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 3:270-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang, S.-W., and T. E. King. 1986. Aspergillus terreus causing invasive pulmonary aspergillosis with air-crescent sign. J. Nat. Med. Assoc. 78:248-253. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheetham, H. D. 1964. Subcutaneous infection due to Aspergillus terreus. J. Clin. Pathol. 17:251-253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chim, C. S., P. L. Ho, S. T. Yuen, and K. Y. Yuen. 1998. Fungal endocarditis in bone marrow transplantation: case report and review of the literature. J. Infect. 37:287-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiou, C. C., N. Mavrogiorgos, E. Tillem, R. Hector, and T. J. Walsh. 2001. Synergy, pharmacodynamics, and time-sequenced ultrastructural changes of the interaction between nikkomycin Z and the echinocandin FK463 against Aspergillus fumigatus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:3310-3321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cimon, B., R. Zouhair, F. Symoens, J. Carrere, D. Chabasse, and J.-P. Bouchara. 2003. Aspergillus terreus in a cystic fibrosis clinic: environmental distribution and patient colonization pattern. J. Hosp. Infect. 53:81-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dannaoui, E., E. Borel, F. Persat, M. A. Piens, and S. Picot. 2000. Amphotericin B resistance of Aspergillus terreus in a murine model of disseminated aspergillosis. J. Med. Microbiol. 49:601-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dannaoui, E., F. Persat, M. F. Monier, E. Borel, M. A. Peins, and S. Picot. 1999. In-vitro susceptibility of Aspergillus spp. isolates to amphotericin B and itraconazole. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 44:553-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Das, T., P. Vyas, and S. Sharma. 1993. Aspergillus terreus postoperative endophthalmitis. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 77:386-387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Denning, D. W. 1994. Invasive aspergillosis in immunocompromised patients. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 7:456-462. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diekema, D. J., S. A. Messer, R. J. Hollis, R. N. Jones, and M. A. Pfaller. 2003. Activities of caspofungin, itraconazole, posaconazole, ravuconazole, voriconazole, and amphotericin B against 448 recent clinical isolates of filamentous fungi. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:3623-3626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drexler, L., M. Rytel, M. Keelan, L. I. Bonchek, and G. N. Olinger. 1980. Aspergillus terreus infective endocarditis on a porcine heterograft valve. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 79:269-274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duthie, R., and D. W. Denning. 1995. Aspergillus fungemia: report of 2 cases and review. Clin. Infect. Dis. 20:598-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.English, M. P., and G. A. Dalton. 1962. An outbreak of fungal infections of post-operative aural cavities. J. Laryngol. Otol. 76:1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Erdman, S. H., B. J. Barber, and L. L. Barton. 2002. Aspergillus cholangitis: a late complication after Kasai portoenterostomy. J. Pediatr. Surg. 37:923-925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Espinel-Ingroff, A. 1998. Comparison of in vitro activities of the new triazole SCH56592 and the echinocandins MK-0991 (L-743,872) and LY303366 against opportunistic filamentous and dimorphic fungi and yeasts. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:2950-2956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Espinel-Ingroff, A. 2003. Evaluation of broth microdilution testing parameters and agar diffusion Etest procedure for testing susceptibilities of Aspergillus spp. to caspofungin acetate (MK-0991). J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:403-409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Espinel-Ingroff, A. 2001. In vitro fungicidal activities of voriconazole, itraconazole, and amphotericin B against opportunistic moniliaceous and dermatiaceous fungi. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:954-958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Espinel-Ingroff, A., K. Boyle, and D. J. Sheehan. 2001. In vitro antifungal activities of voriconazole and reference agents as determined by NCCLS methods: review of the literature. Mycopathologica 150:101-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ford, S., and L. Friedman. 1967. Experimental study of the pathogenicity of aspergilli for mice. J. Bacteriol. 94:928-933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Girmenia, C., M. Nucci, and P. Martino. 2001. Clinical significance of Aspergillus fungaemia in patients with haematological malignancies and invasive aspergillosis. Br. J. Haematol. 114:93-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glotzbach, R. E. 1982. Aspergillus terreus infection of pseudoaneursym of aortofemoral vascular graft with contiguous vertebral osteomyelitis. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 77:224-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldberg, S. L., D. J. Geha, W. F. Marshall, D. J. Inwards, and H. C. Hoagland. 1993. Successful treatment of simultaneous pulmonary Pseudallescheria boydii and Aspergillus terreus infection with oral itraconazole. Clin. Infect. Dis. 16:803-805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grandiere-Perez, L., P. Asfar, C. Foussard, J.-M. Chennebault, P. Penn, and I. Degasne. 2000. Spondylodiscitis due to Aspergillus terreus during an efficient treatment against invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Intensive Care Med. 26:1010-1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gregson, A. E. W., and C. J. LaTouche. 1961. The significance of mycotic infection in the aetiology of otitis externa. J. Laryngol. Otol. 75:167-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hanson, L. H., K. V. Clemons, D. W. Denning, and D. A. Stevens. 1995. Efficacy of oral saperconazole in systemic murine aspergillosis. J. Med. Vet. Mycol. 33:311-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hara, K. S., J. H. Ryu, J. T. Lie, and G. D. Roberts. 1989. Disseminated Aspergillus terreus infection in immunocompromised hosts. Mayo Clin. Proc. 64:770-775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herbrecht, R., D. W. Denning, T. F. Patterson, J. E. Bennett, R. E. Greene, J. W. Oestmann, W. V. Kern, K. A. Marr, P. Ribaud, O. Lortholary, R. Sylvester, R. H. Rubin, J. R. Wingard, P. Stark, C. Durand, D. Caillot, E. Thiel, P. H. Chandrasekar, M. R. Hodges, H. T. Schlamm, P. F. Troke, and B. de Pauw. 2002. Voriconazole versus amphotericin B for primary therapy of invasive aspergillosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 347:408-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iwen, P. C., E. C. Reed, J. O. Armitage, P. J. Bierman, A. Kessinger, J. M. Vose, M. A. Arneson, B. A. Winfield, and G. L. Woods. 1993. Nosocomial invasive aspergillosis in lymphoma patients treated with bone marrow or peripheral stem cell transplants. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 14:131-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Iwen, P. C., M. E. Rupp, A. N. Langnas, E. C. Reed, and S. H. Hinrichs. 1998. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis due to Aspergillus terreus: 12-year experience and review of the literature. Clin. Infect. Dis. 26:1092-1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kalina, P. H., and J. Campbell. 1991. Aspergillus terreus endophthalmitis in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Arch. Ophthalmol. 109:102-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kennedy, W. P. U., L. J. R. Milne, W. Blyth, and G. K. Crompton. 1972. Two unusual organisms, Aspergillus terreus and Metschnikowia pulcherrima associated with the lung disease of ankylosing spondylitis. Thorax 27:604-610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khan, Z. U., M. Kortom, R. Marouf, R. Chandy, M. G. Rinaldi, and D. A. Sutton. 2000. Bilateral pulmonary aspergilloma caused by an atypical isolate of Aspergillus terreus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2010-2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khoo, S. H., and D. W. Denning. 1994. Invasive aspergillosis in patients with AIDS. Clin. Infect. Dis. 19:S41-S48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kimura, M., S.-I. Udagawa, A. Shoji, H. Kume, M. Iimori, T. Satou, and S. Hashimoto. 1990. Pulmonary aspergillosis due to Aspergillus terreus combined with staphylococcal pneumonia and hepatic candidiasis. Mycopathologica 111:47-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koshi, G., and K. M. Cherlan. 1995. Aspergillus terreus, an uncommon fungus causing aortic root abscess and pseudoaneurysm. Indian Heart J. 47:265-267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laham, M. N., and J. L. Carpenter. 1982. Aspergillus terreus, a pathogen capable of causing infective endocarditis, pulmonary mycetoma and allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 125:769-772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laham, M. N., B. Jeffery, and J. L. Carpenter. 1982. Frequency of clinical isolation and winter prevalence of different Aspergillus species at a large southwestern army medical center. Ann. Allergy 48:215-219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lass-Florl, C., G. Kofler, G. Kropshofer, J. Hermans, A. Kreczy, M. P. Dierich, and D. Niederwieser. 1998. In-vitro testing of susceptibility to amphotericin B is a reliable predictor of clinical outcome in invasive aspergillosis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 42:497-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lass-Florl, C., M. Nagl, E. Gunsilius, C. Speth, H. Ulmer, and R. Wurzner. 2002. In vitro studies on the activity of amphotericin B and lipid-based amphotericin B formulations against Aspergillus conidia and hyphae. Mycoses 45:166-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lass-Florl, C., M. Nagl, C. Speth, H. Ulmer, M. P. Dierich, and R. Wurzner. 2001. Studies of in vitro activities of voriconazole and itraconazole against Aspergillus hyphae using viability staining. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:124-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lass-Florl, C., P.-M. Rath, D. Niederwieser, G. Kofler, R. Wurzner, A. Krezy, and M. P. Dierich. 2000. Aspergillus terreus infections in haematological malignancies: molecular epidemiology suggests association with in-hospital plants. J. Hosp. Infect. 46:31-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu, K., D. N. Howell, J. R. Perfect, and W. A. Schell. 1998. Morphologic criteria for the preliminary identification of Fusarium, Paecilomyces and Acremonium species by histopathology. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 109:45-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mahgoub, E. S., S. A. Ismail, and A. M. El Hassan. 1969. Cervical lymphadenopathy caused by Aspergillus terreus. Br. Med. J. 1:689-690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marr, K. A., R. A. Carter, F. Crippa, A. Wald, and L. Corey. 2002. Epidemiology and outcome of mould infections in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 34:909-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mbakwem, C. E., and G. E. Mathison. 1979. Kinetics of inactivation of Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus terreus conidiospores by amphotericin B in the presence of serum. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 46:317-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meletiadis, J., J. W. Mouton, J. F. G. M. Meis, B. A. Bouman, J. P. Donnelly, and P. E. Verweij. 2001. Colorimetric assay for antifungal susceptibility testing of Aspergillus species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3402-3408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mershon, J. C., D. R. Samuelson, and T. E. Layman. 1968. Left ventricular “fibrous body” aneurysm caused by Aspergillus endocarditis. Am. J. Cardiol. 22:281-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Minamoto, G. Y., T. F. Barlam, and N. J. Vander Els. 1992. Invasive aspergillosis in patients with AIDS. Clin. Infect. Dis. 14:66-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moore, C. B., C. M. Walls, and D. W. Denning. 2001. In vitro activities of terbinafine against Aspergillus species in comparison with those of itraconazole and amphotericin B. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1882-1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moore, C. K., M. A. Hellreich, C. L. Coblentz, and V. L. Roggli. 1988. Aspergillus terreus as a cause of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Chest 94:889-891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mosquera, J., A. Sharp, C. B. Moore, P. A. Warn, and D. W. Denning. 2002. In vitro interaction of terbinafine with itraconazole, fluconazole, amphotericin B and 5-flucytosine against Aspergillus spp. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 50:189-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Neumeister, B., W. Hartmann, M. Oethinger, B. Heymer, and R. Marre. 1994. A fatal infecton with Alternaria alternata and Aspergillus terreus in a child with agranulocytosis of unknown origin. Mycoses 37:181-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Oakley, K. L., C. B. Moore, and D. W. Denning. 1999. Comparison of in vitro activity of liposomal nystatin against Aspergillus species with those of nystatin, amphotericin B (AB) deoxycholate, AB colloidal dispersion, liposomal AB, AB lipid complex, and itraconazole. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1264-1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Oakley, K. L., C. B. Moore, and D. W. Denning. 1997. In vitro activity of SCH-56592 and comparison with activities of amphotericin B and itraconazole against Aspergillus spp. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:1124-1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Olenchock, S. A., F. H. Y. Green, M. S. Mentnech, J. C. Mull, and W. G. Sorenson. 1983. In vivo pulmonary response to Aspergillus terreus spores. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 6:67-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Onsberg, P., D. Stahl, and N. K. Veien. 1978. Onychomycosis caused by Aspergillus terreus. Sabouraudia 16:39-46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ornvold, K., and J. Paepke. 1992. Aspergillus terreus as a cause of septic olecranon bursitis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 97:114-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Park, K. U., H. S. Lee, C. J. Kim, and E. C. Kim. 2000. Fungal discitis due to Aspergillus terreus in a patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J. Korean Med. Sci. 15:704-707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Perea, S., G. Gonzalez, A. W. Fothergill, W. R. Kirkpatrick, M. G. Rinaldi, and T. F. Patterson. 2002. In vitro interaction of caspofungin acetate with voriconazole against clinical isolates of Aspergillus spp. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:3039-3041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Perfect, J. R., G. M. Cox, J. Y. Lee, C. A. Kauffman, L. de Repentigny, S. W. Chapman, V. A. Morrison, P. Pappas, J. W. Hiemenz, D. A. Stevens, and Mycoses Study Group. 2001. The impact of culture isolation of Aspergillus species: a hospital-based survey of aspergillosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 33:1824-1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pfaller, J. B., S. A. Messer, R. J. Hollis, D. J. Diekema, and M. A. Pfaller. 2003. In vitro susceptibility testing of Aspergillus spp.: comparison of Etest and reference microdilution methods for determining voriconazole and itraconazole MICs. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:1126-1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pfaller, M. A., S. A. Messer, R. J. Hollis, R. N. Jones, and the SENTRY Participants Group. 2002. Antifungal activities of posaconazole, ravuconazole, and voriconazole compared to those of itraconazole and amphotericin B against 239 clinical isolates of Aspergillus spp. and other filamentous fungi: report from SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program, 2000. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1032-1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pfaller, M. A., S. A. Messer, K. Mills, and A. Bolmstrom. 2000. In vitro susceptibility testing of filamentous fungi: comparison of Etest and reference microdilution methods for determining itraconazole MICs. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3359-3361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pore, R. S., and H. W. Larsh. 1967. Aleuriospore formation in four related Aspergillus species. Mycologia 59:318-325. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pore, R. S., and H. W. Larsh. 1968. Experimental pathology of Aspergillus terreus-flavipes group species. Sabouraudia 6:89-93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Powell, D. E. B., M. P. English, and E. H. L. Duncan. 1962. Clinical, bacteriological and mycological findings in postoperative ear cavities. J. Laryngol. Otol. 76:12-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pursell, K. J., E. E. Telzak, and D. Armstrong. 1992. Aspergillus species colonization and invasive disease in patients with AIDS. Clin. Infect. Dis. 14:141-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Raper, K. B., and D. I. Fennel. 1965. Aspergillus terreus group. In K. B. Raper and D. I. Fennel (ed.), The genus Aspergillus. The Williams & Wilkins Co., Baltimore, Md.

- 76.Rippon, J. W., D. N. Anderson, and M. Soo Hoo. 1971. Aspergillosis: comparative virulence, metabolic rate, growth rate and ubiquinone content of soil and human isolates of Aspergillus terreus. Sabouraudia 12:157-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Robinson, L. A., E. C. Reed, T. A. Galbraith, A. Alonso, A. L. Moulton, and W. H. Fleming. 1995. Pulmonary resection for invasive Aspergillus infections in immunocompromised patients. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 109:1182-1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rosa, R. H., D. Miller, and E. C. Alfonso. 1994. The changing spectrum of fungal keratitis in South Florida. Ophthalmology 101:1005-1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Russack, V. 1990. Aspergillus terreus myocarditis: report of a case and review of the literature. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 3:275-279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schell, W. A. 1995. New aspects of emerging fungal pathogens: a multifaceted challenge. Clin. Lab. Med. 15:365-387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schett, G., B. Casati, B. Willinger, G. Weinlander, T. Binder, F. Grabenwoger, W. Sperr, K. Geissler, and U. Jager. 1998. Endocarditis and aortal embolization caused by Aspergillus terreus in a patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in remission: diagnosis by peripheral-blood culture. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:3347-3351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Seligsohn, R., J. W. Rippon, and S. A. Lerner. 1977. Aspergillus terreus osteomyelitis. Arch. Intern. Med. 137:918-920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Silva, M. E., M. H. Malogolowkin, T. R. Hall, A. M. Sadeghi, and P. Krogstad. 2000. Mycotic aneursym of the thoracic aorta due to Aspergillus terreus: case report and review. Clin. Infect. Dis. 31:1144-1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Singh, S. M., S. Sharma, and P. K. Chatterjee. 1990. Clinical and experimental mycotic keratitis caused by Aspergillus terreus and the effect of subconjunctival oxiconazole treatment in the animal model. Mycopathologica 112:127-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Stein, S. C., M. L. Corrado, M. Friedlander, and P. Farmer. 1982. Chronic mycotic meningitis with spinal involvement (arachnoiditis): a report of five cases. Ann. Neurol. 11:519-524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Steinbach, W. J., D. K. Benjamin, Jr., D. P. Kontoyiannis, J. R. Perfect, I. Lutsar, K. A. Marr, M. S. Lionakis, H. A. Torres, H. Jafri, and T. J. Walsh. 2004. Infections due to Aspergillus terreus: multicenter retrospective analysis of 80 cases. Clin. Infect. Dis. 39:192-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Steinfeld, S., P. Durez, J.-P. Hauzeur, S. Motte, and T. Appelboom. 1997. Articular aspergillosis: two case reports and review of the literature. Br. J. Rheumatol. 36:1331-1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sukroongreung, S., and K. Thakerngpol. 1985. Abnormal form of Aspergillus terreus isolated from mycotic abscesses. Mycopathologica 91:47-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Suseelan, A. V., H. C. Gugnani, and J. O. Ojukwu. 1976. Primary cutaneous aspergillosis due to Aspergillus terreus. Arch. Dermatol. 112:1468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sutton, D. A., S. E. Sanchie, S. G. Revankar, A. W. Fothergill, and M. G. Rinaldi. 1999. In vitro amphotericin B resistance in clinical isolates of Aspergillus terreus, with a head-to-head comparison to voriconazole. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2343-2345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Szekely, A., E. M. Johnson, and D. W. Warnock. 1999. Comparison of E-test and broth microdilution methods for antifungal drug susceptibility testing of molds. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1480-1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Thamlikitkul, V., K. Prachuabmoh, S. Sukroongreung, and S. Danchaivijtir. 1983. Aspergillus terreus endocarditis—a case report. J. Med. Assoc. Thailand 66:722-726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tiwari, S., S. M. Singh, and S. Jain. 1995. Chronic bilateral suppurative otitis media caused by Aspergillus terreus. Mycoses 38:297-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Trachana, M., E. Roilides, N. Gompakis, K. Kanellopoulou, M. Mpantouraki, and F. Kanakoudi-Tsakalidou. 2001. Case report. Hepatic abscesses due to Aspergillus terreus in an immunodeficient child. Mycoses 44:415-418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tracy, S. L., M. R. McGinnis, J. E. Peacock, M. S. Cohen, and D. H. Walker. 1983. Disseminated infection by Aspergillus terreus. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 80:728-733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tritz, D. M., and G. L. Woods. 1993. Fatal disseminated infection with Aspergillus terreus in immunocompromised hosts. Clin. Infect. Dis. 16:118-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Verghese, S., T. Methew, P. Padmaja, A. Mullasari, A. Sivaraman, and V. M. Kurien. 2001. Sclerosing mediastinitis caused by Aspergillus terreus. Indian J. Pathol. Microbiol. 44:141-143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Vincken, W., W. Schandevul, and P. Roels. 1983. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis caused by Aspergillus terreus. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 127:388-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wald, A., W. Leisenring, J. A. H. van Burik, and R. A. Bowden. 1997. Epidemiology of Aspergillus infection in a large cohort of patients undergoing bone marrow transplantation. J. Infect. Dis. 175:1459-1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Walmsley, S., S. Devi, S. King, R. Schneider, S. Richardson, and L. Ford-Jones. 1993. Invasive Aspergillus infections in a pediatric hospital: a ten year review. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 12:673-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Walsh, T. J., V. Petraitis, R. Petraitiene, A. Field-Ridley, D. Sutton, M. Ghannoum, T. Sein, R. Schaufele, J. Peter, J. Bacher, H. Casler, D. Armstrong, A. Espinel-Ingroff, M. G. Rinaldi, and C. A. Lyman. 2002. Experimental pulmonary aspergillosis due to Aspergillus terreus: pathogenesis and treatment of an emerging fungal pathogen resistant to amphotericin B. J. Infect. Dis. 188:305-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Warn, P. A., G. Morrissey, J. Morrissey, and D. W. Denning. 2003. Activity of micafungin (FK463) against an intraconazole-resistant strain of Aspergillus fumigatus and a strain of Aspergillus terreus demonstrating in vivo resistance to amphotericin B. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 51:913-919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zaias, N. 1972. Onychomycosis. Arch. Dermatol. 105:263-274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]