Abstract

Wild-type and efflux pump-deficient cells of Candida albicans adhering to silicone were compared with planktonic cells by flow cytometry for their relative resistance to fluconazole (FCZ). Flow cytometry data on cells carrying a fusion of green fluorescent protein to efflux pump promoters confirmed that enhanced tolerance of attached cells to FCZ was due in part to increased expression of CaMDR1 and CDR1 promoters. Within 2 h of their attachment to silicone, the adherent cells demonstrated levels of FCZ tolerance shown by cells from 24-h biofilms. Following their mechanical detachment, this subset of cells retained a four- to eightfold increase in tolerance compared with the tolerance of planktonic cells for at least two generations. Enhanced efflux pump tolerance to FCZ appeared to be induced within the initial 15 min of attachment in a subset of cells that were firmly attached to the substrata.

Candida albicans is an adventitious pathogen commonly found as a commensal in healthy individuals (29). C. albicans produces a broad range of serious illnesses in immunocompromised hosts (21), being the fourth most common cause of nosocomial infections, usually arising from indwelling devices (3, 27). Medical implants provide adequate substrata for yeast attachment and biofilm formation and are associated with a high incidence of systemic candidiasis (3, 5, 7, 14).

Chandra et al. (3) reported that biofilms of C. albicans formed on polymethylmethacrylate and silicone elastomer disks had a highly heterogeneous architecture composed of cellular and noncellular elements. Antifungal resistance of the biofilm compared to that of planktonic cells increased in conjunction with three stages of biofilm formation, 0 to 11 h, 12 to 30 h, and ∼38 to 72 h. The progression in drug resistance was associated with a concomitant increase in metabolic activity (tetrazolium reduction) of the developing biofilm. Biofilm structure, particularly on polymethylmethacrylate, was biphasic, being composed of an adherent blastospore layer covered by more sparse hyphal elements. In the later biofilm stages on silicone elastomer disks, the hyphal elements pervaded the matrix.

Hawser and Douglas (12) reported that the MIC of amphotericin B was up to 200 times higher for biofilms of C. albicans than for those of planktonic cells. Similarly, Kalya and Ahearn (15) reported higher MICs and minimal fungicidal concentrations of amphotericin B, miconazole, ketoconazole, fluconazole (FCZ), and itraconazole for cells of C. albicans adhering to silicone for 2 h than for planktonic cells. The protective nature of the biofilm exopolymeric matrix has been proposed as a mechanism for biofilm resistance (2); nevertheless, cells of Candida spp. adhering to silicone or polyethylene for as little as 2 h show less susceptibility to antimicrobial agents than do planktonic cells (15, 17).

FCZ has been the antifungal agent of choice for the treatment of mucosal and systemic C. albicans infections. The wide use of FCZ for the treatment of C. albicans infections and other mycoses is now being hindered by the appearance of resistant strains. Approximately 15 to 30% of oral candidiasis infections in patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infections are produced by clinically resistant strains of C. albicans (31). The most prevalent group of resistance mechanisms found in C. albicans targets the reduction of FCZ accumulation through the increased transcription of the multiple drug resistance transport protein-encoding genes CDR1, CDR2, and CaMDR1 (4, 31).

Most studies of FCZ resistance have involved planktonic cells. Studies of fungal biofilms usually involve mature biofilms, and sparse information is available on the physiology and phenotype of fungal cells in the initial stages of biofilm formation. Both bacterial and fungal studies have revealed that attachment to a surface can either stimulate or repress the expression of genes directly involved in the attachment process (30). The goals here were to examine the initial stages of biofilm formation, i.e., firmly adherent cells of C. albicans (prior to cell division or pseudohypha formation), and to determine whether adhesion to a surface induces changes in the expression of genes that enhance survival in the presence of FCZ. Enhanced expression of multidrug efflux pumps has been reported for Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms (1, 6) and for Magnaporthe grisea adhering to plant tissue (28). Recently, Mukherjee et al. (20) extensively reviewed the mechanisms of FCZ resistance and reported that C. albicans expresses CDR and MDRI genes in all three stages of biofilm development, including analyses performed within 6 h.

The present study, with FCZ-susceptible strains of C. albicans, confirms that the capacity for increased FCZ tolerance in adherent cells is at least partially efflux pump related. Evidence is presented that this increased activity is induced upon attachment and is not necessarily a consequence of mature biofilm formation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, cell growth, and maintenance.

C. albicans CaI4 (Δura3:: imm434/Δura3::imm434), courtesy of B. Lasker, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga., served as the parental strain for the generation of strains containing yEGFP (yeast-optimized fluorescence-activated cell sorting-enhanced green fluorescent protein [GFP]). In addition, CaMDR1, CDR1, and CDR2 knockout strains were donated by D. Sanglard (Institut de Microbiologie, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois, Lausanne, Switzerland). C. albicans wild-type strain Ca30 (15) and clinical isolate JK21 (courtesy of A. Karlowsky, Department of Clinical Microbiology, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada) were used as FCZ-susceptible and FCZ-resistant controls, respectively. Table 1 shows a description of the strains used in this study.

TABLE 1.

Genotypes of C. albicans strains

| Strain | Genotype | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Ca30 | Wild type | 14 |

| CaI4 | Δura3::imm434/Δura3::imm434 | 9 |

| DSY449 | Δcdr1::hisG/Δcdr1::hisG | 25 |

| DSY465 | Δcamdr1::hisG-URA3-hisG/Δcamdr1::hisG Δcdr1::hisG/Δcdr1::hisG | 25 |

| DSY468 | Δcamdr1::hisG-URA3-hisG/Δcamdr1::hisG | 25 |

| DSY653 | Δcdr2::hisG-URA3-hisG/Δcdr2::hisG | 26 |

| DSY654 | Δcdr1::hisG/Δcdr1::hisG Δcdr2::hisG-URA3-hisG/Δcdr2::hisG | 26 |

| CaCMR4 | Δura3::imm434/Δura3::imm434 CDR4/Δcdr4::CaMDR1prom-GFP-ACT1t-URA3 | This study |

| CaCMR5 | Δura3::imm434/Δura3::imm434 CDR4/Δcdr4::ACT1prom-GFP-ACT1t-URA3 | This study |

| CaCMR7 | Δura3::imm434/Δura3::imm434 CDR4/Δcdr4::CDR1prom-GFP-ACT1t-URA3 | This study |

| CaCMR8 | Δura3::imm434/Δura3::imm434 CDR4/Δcdr4::CDR2prom-GFP-ACT1t-URA3 | This study |

Cultures were grown at 30°C and 130 rpm in glucose yeast nitrogen base medium (GYNB; Bio 101, Carlsbad, Calif.) without amino acids but supplemented with complete supplement mixture lacking uracil (Bio 101) and 2% glucose (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburg, Pa.), except for C. albicans CaI4, which required supplementation with 40 μg of uridine (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.)/ml. Starter cultures were subcultured to mid-logarithmic phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600], 1.0; equivalent to ∼107 cells/ml), and the subcultures in turn served as inocula for all experiments.

Strain design.

Primer sequences and annealing sites are shown in Table 2. yEGFP was used as a reporter of transcription from the CaMDR1, CDR1, and CDR2 promoters. A segment from plasmid pGFP41 (18) containing yEGFP, a 0.4-kb fragment of the 3′ untranslated region of the C. albicans actin gene (ACT1), and the regulatory and coding regions of the orotidine 5′-monophosphate decarboxylase gene (URA3) was PCR amplified with primers GFPf and URA3r. Plasmid pCMR1 was constructed by cloning this segment into pBluescript II KS(−) (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) by using the restriction enzymes ClaI and PstI. Two 2-kb segments of the CDR4 gene (bases −339 to +1778 and +2366 to +4471 from the origin) were PCR amplified with primers 5′CDR4f and 5′CDR4r, primers 3′CDR4f and 3′CDR4r, and C. albicans CaI4 genomic DNA as the template. The enzymes KpnI and XhoI were used to clone the 5′ CDR4 fragment (2.1 kb) upstream of the GFP gene in pCMR1, resulting in the generation of plasmid pCMR2 (7.3 kb). The enzymes HpaI and SacI were used to clone the 3′ CDR4 fragment (2.1 kb) downstream of the 3′ end of URA3 in pCMR2, resulting in plasmid pCMR3. The latter plasmid served as the vector backbone for cloning the promoter regions of the CaMDR1 (−980 to −1), CDR1 (−1200 to −1), CDR2 (−883 to −1), and ACT1 (−1027 to −1) genes. Each PCR product was digested with XhoI and ClaI and ligated to similarly digested plasmid pCMR3, resulting in the generation of plasmids pCMR4 (CaMDR1 promoter), pCMR5 (ACT1 promoter), pCMR7 (CDR1 promoter), and pCMR8 (CDR2 promoter).

TABLE 2.

Primer sequences

| Name | Sequencea | Annealing site | Restriction enzyme |

|---|---|---|---|

| GFPf | 5′-GGG ATCGAT ATGAGTAAAGGA-3′ | +1 (GFP) | ClaI |

| URA3r | 5′-AAA CTGCAG AAGGACCACCTTT-3′ | +924 (URA3) | PstI |

| 5′CDR4f | 5′-CCC GGTACC GGCTAGCAGTTTGAG-3′ | −325 (CDR4) | KpnI |

| 5′CDR4r | 5′-GG CTCGAG CGCATCTGCTGCAGG-3′ | +1764 (CDR4) | XhoI |

| 3′CDR4f | 5′-CACCTGCAGGGGTGCAATGCA-3′ | +2366 (CDR4) | None |

| 3′CDR4r | 5′-CCCG AGCTC CAACGTTTACGTCT-3′ | +4458 (CDR4) | SacI |

| MDR1pf | 5′-CAA CTCGAG CACACAGCCGTGAATCTTA-3′ | −5421 (CaMDR1) | XhoI |

| MDR1pr | 5′-CCC ATCGAT GTGAAGTTCTATGTAAGTAGATG-3′ | −1 (CaMDR1) | ClaI |

| CDR1pf | 5′-CC CTCGAG GTTACTCAATAAGTATTAA-3′ | −1182 (CDR1) | XhoI |

| CDR1pr | 5′-CC ATCGAT AATTTTTTTCTTTTTGACC-3′ | −1 (CDR1) | ClaI |

| CDR2pf | 5′-CC CTCGAG ACTAGAAGGTTATCAAGA-3′ | −866 (CDR2) | XhoI |

| CDR2pr | 5′-CCC ATCGAT ATGTTTTTATTGTATGTG-3′ | −1 (CDR2) | ClaI |

| ACT1pf | 5′-CC CTCGAG AGAGCTATTAAGATCACCAG-3′ | −1017 (ACT1) | XhoI |

| ACT1pr | 5′-CC ATCGAT TTTGAATGATTATATTTTTTT-3′ | −1 (ACT1) | ClaI |

| E | 5′CCACATCAGGAGATTATTCGAGCT-3′ | −399 (CDR4) | None |

| B | 5′-ACATCACCATCTAATTCAACAAG-3′ | +42 (GFP) | None |

| C′ | 5′-TTTCCTATGAATCCACTATTGAACC-3′ | +208 (URA3) | None |

| F | 5′-TCCCTGATAGCACTTGGCATTTAT-3′ | +4630 (CDR4) | None |

| G | 5′-GGAGTTCTTCGGAAATTGACCATAAAA-3′ | +1847 (CDR4) | None |

CaCl2-competent Escherichia coli DH5α was plated on Luria-Bertani medium supplemented with ampicillin (Sigma) to 100 μg/ml after the transformation procedure. The presence of the correct ligation product was confirmed through restriction enzyme analysis.

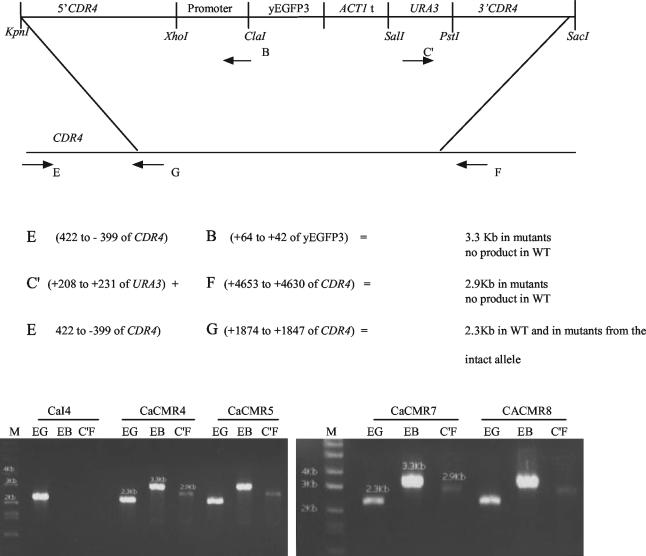

The promoter constructs present in pCMR4, pCMR5, pCMR7, and pCMR8 were PCR amplified with primers 5′CDR4for and 3′CDR4rev (Table 2) and inserted in one of the CDR4 alleles of C. albicans CaI4 cells through double homologous recombination. Cells were transformed by a modification (25) of the lithium acetate procedure described by Gietz and Woods (10) for Saccharomyces cerevisiae, plated on GYNB, and incubated for 4 days at 30°C. Accurate integration of promoter fusion constructs in only one allele of the CDR4 gene was accomplished by PCR (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Confirmation of chromosomal integration by PCR. Primers E, B, C′, and F were used to confirm the integration of the promoter fusion constructs into one of the CDR4 alleles of CaI4. A 10-μl volume of PCR mixture and a 10-μl volume of Hi-Lo DNA molecular weight marker (Minnesota Molecular Inc., Minneapolis, Minn.) (lanes M) were loaded on a 2% agarose gel and run at 80 V for 2 h. Strains, primer sets, and band sizes are indicated. WT, wild type.

The mean fluorescence intensity emitted by yEGFP (FL1) was analyzed for each strain by flow cytometry after chemical induction of the expression of each promoter. Cells grown overnight in GYNB to a final density of 107 cells/ml were incubated for 1 h at 30°C and 130 rpm in the presence of 10 μg of benomyl/ml, 1 mM β-estradiol, or 1 mg of fluphenazine (Sigma)/ml.

Adherence.

Cells were allowed to adhere to substrata with modifications of the “primary adhesion” test described by Ahearn et al. (1). Cells for inocula were grown in GYNB to mid-exponential phase and harvested by centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 10 min. The pellets were washed once in sterile 0.9% NaCl and suspended in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to a final density of 0.5 × 108 to 1 × 108 cells/ml. Flat sterile medical-grade silicone disks, with a total surface area of 312.5 mm2, were incubated in 3.0 ml of cell suspension for 2 h at 30°C and 100 rpm. After the prescribed adherence period, each silicone disk was rinsed by dipping five times in each of three changes of 180 ml of sterile saline (0.9% NaCl). Rinsed disks with adherent yeast cells then were used for subsequent experiments. The cells retained on the disks were singular, some with attached buds, but without germ tubes or hyphal forms, and always were present at <10% the initial density of cells per milliliter in the inoculum (per square millimeter).

The number of adherent cells per disk was determined by a modified radiolabeled-cell procedure (1, 18). In separate experiments with each strain, cell inocula prepared as described above and washed in PBS were inoculated into GYNB at a final concentration of 1 × 108 to 2 × 108 cells/ml and incubated for 1 h at 30°C and 130 rpm. Following incubation, the cells were radiolabeled with a final concentration of 2.5 μCi of l-[3,4,5-3H]leucine (NEN Research Products, Dupont Company, Wilmington, Del.)/ml for 30 min. Radiolabeled cells were washed three times in sterile saline, suspended in PBS to a final density of 108 cells/ml, and allowed to adhere for 2 h. Disks rinsed as described above and with firmly adherent cells were transferred to glass scintillation vials containing 10 ml of OptiFluor scintillation cocktail (Packard Instrument Co., Downers Grove, Ill.), and the disintegrations per minute were read in a liquid scintillation counter (LS-7500; Beckman Instruments, Inc., Fullerton, Calif.) for 1 min per disk. The number of adherent cells per disk was determined by extrapolation of the disintegrations per minute obtained from each silicone disk to a nomograph correlating disintegrations per minute produced by known cell numbers. The data were normalized for any nonspecific background radiation from the disks.

Biofilm formation.

Nonradiolabeled cells firmly adhering to silicone were transferred to fresh GYNB and incubated for an additional 24 to 48 h at 30°C and 100 rpm. A biofilm was observed on the silicone disks even when growth in the surrounding medium was sparse. Cells released from the biofilm and growing in surrounding GYNB are henceforth referred to as daughter cells, and cells retained on the disks are referred to as biofilm cells. Disks with biofilms were rinsed as described above for the preparation of adherent cells.

Detachment.

Silicone disks with adherent cells, rinsed in PBS for the removal of loosely associated cells as described above, were placed in 1.0 ml of sterile PBS and subjected to five cycles of a two-step process consisting of 1 min of sonication at 75 Hz (Bransonic Ultrasonic Cleaner 2210; Branson Ultrasonic Co., Danbury, Conn.) followed by 30 s of vigorous vortexing. Detachment efficiency was determined from the reduction in radioactivity from the disks after the detachment process.

FCZ susceptibility.

Mid-exponential-phase planktonic cells (106 cells/ml), adherent cells (about 106 cells/312.5 mm2), 24-h biofilm cells (1 × 106 to 2 × 106 cells/312.5 mm2), detached cells after adherence for 2 h (0.8 × 106 cells/ml), and biofilm daughter cells from 24- and 48-h biofilms were incubated in fresh medium at 30°C under static conditions for 4 h in the presence of FCZ. The FCZ concentrations ranged from 0.125 to 128 μg/ml in twofold increments. After FCZ challenge, the cells were harvested, suspended in sterile PBS, and stained for 1 min with 0.025 mg of propidium iodide (PI)/ml and 25 mM sodium deoxycholate. Exposure of cells to FCZ results in an increase in membrane permeability, which in turn allows for labeling of the cells with PI. Representative experiments by Ramani et al. (23) and Ramani and Chaturvedi (24) showed that cellular permeability to PI, as determined by flow cytometry, correlated with recoverable cell numbers and with the results of the NCCLS broth microdilution method. Based on similar experiments, we selected the lowest FCZ concentration at which at least 90% of the cells in the FCZ-exposed population fluoresced following exposure to PI (mean fluorescence intensity at 620 nm [FL2] above the 1,000 electronic peak channel) as the minimal permeation concentration (MPC). The MPCs coincided with the MICs of FCZ established for the wild-type strain by standard procedures. Different cell populations were compared on the basis of their MPCs. The FL2 emitted by 10,000 cells was recorded and analyzed with CELLQuest software on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany). Electronic gates were set up based on live and heat-killed cells, excluding cell debris. The instrument was calibrated before each experiment according to the manufacturer's instructions. Viable cells, heat-killed cells, cells after the detachment procedure, cells exposed to sodium deoxycholate, and cells exposed to both PI and sodium deoxycholate were used as controls.

In separate experiments, mid-exponential-phase planktonic cells (106 cells/ml) and adherent cells (106 cells/disk) of CaI4 were incubated at 30°C and 130 rpm for 30 min in fresh GYNB supplemented with 10.24 μM rhodamine 123 (Rh123; Sigma). After the incubation period, cells were washed twice in PBS, and the mean fluorescence emitted at 530 nm by intracellular Rh123 was read by flow cytometry.

Adhesion and yEGFP expression.

yEGFP expression in planktonic cultures of CaI4 (parental strain), CaCMR4, CaCMR7, and CaCMR8 was confirmed. Cells (106/ml) were incubated in the presence of 10 μg of benomyl/ml, 1 mM β-estradiol, or 1 mg of fluphenazine/ml for 1 h at 30°C and 130 rpm. The mean fluorescence intensity (FL1) emitted by 10,000 cells per sample was quantified by flow cytometry with CELLQuest software. Cultures incubated under the same conditions but without the drug served as a control.

The effect of adhesion on the expression of GFP from the different promoters was analyzed by flow cytometry and epifluorescence microscopy. For flow cytometric analysis, disks with adherent cells were incubated for 4 and 24 h at 30°C and 100 rpm and, after detachment, the mean fluorescence intensity emitted by 10,000 cells per sample was quantified by flow cytometry. Fluorescence was determined for planktonic cells prior to attachment and for daughter cells from 24- and 48-h biofilms.

For epifluorescence microscopy analysis, the cells were allowed to adhere to one side of glass coverslips (diameter, 12 mm; thickness, 0.17 mm), and the fluorescence emitted by cells at different time points after the onset of adherence (15 min, 30 min, 1 h, 2 h, 4 h, and 6 h) was analyzed and compared to that emitted by planktonic cells. The laser scanning confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM510) was equipped with a ×40 F Fluor oil immersion objective, a 100-W Hg vapor arc lamp as an excitation source, a B-2E/C fluorescein isothiocyanate filter block (excitation wavelength, 465 to 495 nm; barrier filter wavelength, 515 to 555 nm), and Zeiss LSM software.

Effect of growth stage on yEGFP expression.

Cells were grown in GYNB to late lag phase (OD600, 0.1); until stationary phase was reached, 3 samples of 1.0 ml each were taken from each culture, washed once with saline, suspended in PBS, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Progression through the different growth stages was determined by measuring changes in the OD600 with a Turner SP-830 spectrophotometer (Barnstead/Thermolyne, Dubuque, Iowa).

Statistical analyses.

All assays were performed at least in triplicate, and the standard error (SE) for each set of data was determined. Means were compared by using the Student t test (Microsoft Excel 2000) (P < 0.01).

RESULTS

Adherence of C. albicans to medical-grade silicone disks.

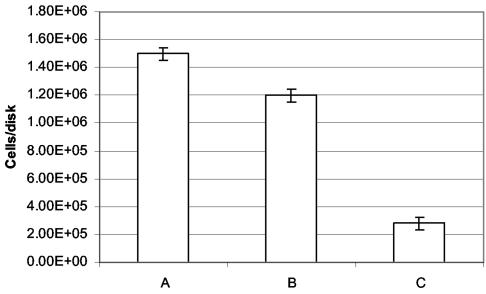

Maximal and consistent adherence of C. albicans to medical-grade silicone disks was obtained with 3 ml of cell suspension (108 cells/ml) after 2 h at 30°C with shaking at 100 rpm. The average number of adherent Ca30 cells was 1.5 × 106 cells/disk (4.8 × 103 cells/mm2) (Fig. 2). Mutant strains (CaI4, transport knockout mutants, and yEGFP mutants) (Table 1), except for JK21, which showed negligible adherence, achieved comparable adherence levels.

FIG. 2.

Quantification of C. albicans adherence and detachment. C. albicans Ca30 was allowed to adhere to medical-grade silicone disks (312.5 mm2) for 2 h at 30°C with shaking at 100 rpm. Bars denote the total numbers of adherent cells (A), detached cells (B), and cells retained on disks after detachment (C). Data are the average of three independent experiments. Error bars represent variations between those experiments (∼4.5 × 104 cells/disk).

More than 80% of the wild-type and mutant cells (i.e., ∼1.0 × 106 cells) were recovered after the detachment procedure. Microscopic examination confirmed that a sparse cell population was retained on the silicone disks after the detachment process. The average percentage of cells showing an FL2 value (permeation by PI) above the 1,000 electronic peak channel after the detachment procedure was 8.5% (n = 3, SE = 0.49); the corresponding FL2 value for nonsonicated planktonic cells in mid-exponential cultures was 8.9% (n = 3, SE = 0.58). Thus, the effect of sonication on cell membrane integrity was considered nonsignificant (P > 0.1).

FCZ susceptibility testing.

Over 90% of total planktonic cells of C. albicans Ca30 and CaI4 were susceptible to FCZ at 1 μg/ml. In contrast, only 11% of cells of the heterologous resistant control JK21 were permeated when incubated with FCZ at 128 μg/ml (Table 3). In only 6 h (i.e., 2 h of adherence and 4 h of FCZ challenge in an adherent state), Ca30 and CaI4 cells showed a 100-fold increase in tolerance to FCZ compared to planktonic cells. This increase in tolerance was not related to a decrease in drug diffusion into the cell. The difference between the intracellular levels of Rh123 in planktonic cells (2,216 ± 118) and adherent cells (2,434 ± 242), measured as the average fluorescence (arbitrary units; logarithmic scale) emitted at 530 nm by 10,000 cells in three independent experiments, was statistically nonsignificant (P > 0.1). C. albicans Ca30 biofilms (after 24 h of incubation) as well as CaI4 biofilms of the same age had the same relative levels of FCZ tolerance (P > 0.1) as adherent cells of the same strains (Table 3). After being allowed to adhere for 2 h, detached, and then kept in a planktonic state for 4 h, Ca30 and CaI4 cells showed significantly decreased tolerance to FCZ, but the tolerance was still four- to eightfold greater than that of the initial planktonic population (Table 3). Retained tolerance to FCZ was also observed by Ramage et al. (22) for cells mechanically detached from a mature (24-h) biofilm. The FCZ tolerance of daughter cells from 24- and 48-h biofilms was similar to that of planktonic cells of the same age and significantly less than that of cells firmly adhering to silicone disks for less than 6 h (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Effect of FCZ on permeation of C. albicans cells

| Populationa | MPC (μg of FCZ/ml) | % Permeated cellsb |

|---|---|---|

| Planktonic JK21 cells | 128 | 11 |

| Planktonic Ca30 cellsc | 1 | 95 |

| Planktonic CaI4 cellsc | 1 | 94 |

| Adherent Ca30 cellsc | 128 | 50 |

| Adherent CaI4 cellsc | 128 | 48 |

| 24-h Ca30 biofilmsc | 128 | 43 |

| 24-h CaI4 biofilmsc | 128 | 39 |

| Detached Ca30 cells | 4 | 91 |

| Detached CaI4 cells | 4-8 | 92 |

| 24-h daughter Ca30 cells | 2 | 98 |

| 24-h daughter CaI4 cells | 2 | 96 |

| 24-h planktonic Ca30 cells | 1-2 | 94 |

| 24-h planktonic CaI4 cells | 2 | 96 |

| 48-h daughter Ca30 cells | 1-2 | 96 |

| 48-h daughter CaI4 cells | 2-4 | 91 |

| 48-h planktonic Ca30 cells | 1-2 | 90 |

| 48-h planktonic CaI4 cells | 4 | 94 |

The permeation of C. albicans cells by FCZ was evaluated with planktonic cells, attached cells, mature biofilms, and biofilm daughter cells.

Percentage of cells with a mean fluorescence intensity at 620 nm (FL2) of greater than 1,000 at the indicated MPC.

Unlike planktonic cells, adherent and biofilm cells were subjected to mild sonication prior to flow cytometric analysis; nonetheless, adherent and biofilm cells showed less than 50% the permeation shown by plantonic cells.

Planktonic and adherent null mutant cells, except for those of DSY653, were significantly more susceptible to FCZ than wild-type cells (Ca30) (Table 4). Single and double mutations of the cdr1, cdr2, and mdr1 genes do not seem to affect the resistance to FCZ of mature biofilms (22). In contrast, a 16-fold decrease in the susceptibility of the Δcamdr1 strain and a greater than 500-fold decrease in the susceptibility of the Δcdr1 strain were observed for adherent cells versus planktonic cells. Adherent cells lacking the CaMDR1 gene were susceptible to FCZ at levels eightfold lower than those to which cells lacking the CDR1 gene were susceptible (64 and 8 μg/ml, respectively). The effect of the mutations was so extensive that cells of adherent double mutants (Δcamdr1 Δcdr1) showed susceptibility to FCZ similar to that of planktonic cells (CaI4). However, cells lacking the CDR2 gene were not affected in their ability to respond to FCZ challenge. The FCZ susceptibility of DSY653 and DSY654 cells resembled that of wild-type and DSY449 cells, respectively, in both the planktonic and the adherent states (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Concentration of FCZ necessary for permeation of 90% of adherent C. albicans cells

| Strain | FCZ concn, μg/ml, required for permeation of the following cellsa:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Planktonic | Primary adherent | |

| Ca30 (wild type) | 1 | 128 (59) |

| DSY465 (Δcamdr1) | 0.5 | 8 |

| DSY449 (Δcdr1) | 0.125 | 64 |

| DSY468 (Δcamdr1 Δcdr1) | 0.0625 | 1 |

| DSY653 (Δcdr2) | 1 | 128 (79) |

| DSY654 (Δcdr1 Δcdr2) | 0.125 | 64 |

When permeation of 90% of the cells was not achieved at the maximum FCZ concentration tested, the percentage of permeated cells achieved at that concentration is shown in parentheses.

Promoter expression.

Basal expression of the CaMDR1 promoter (CaCMR4 cells) was only 1.5 times higher than that in CaI4 cells (parental strain). After promoter expression was induced with benomyl, CaCMR4 cells emitted a mean fluorescence intensity (FL1) 11 times higher than that emitted by parental cells and 7 times higher than that emitted in the absence of benomyl induction. The difference in expression from the CaMDR1 promoter in the presence and in the absence of FCZ was statistically significant (P < 0.001). Basal CDR1 expression (CaCMR7 cells) was also 1.5-fold higher than the autofluorescence emitted by parental cells. After induction with β-estradiol, CDR1 expression increased up to 16-fold from its basal state and was 21-fold higher than that of parental cells. This increase was time dependent and, for up to 60 min, represented a linear increase in fluorescence yield per unit of time. The basal expression of CDR2 was 1.65-fold higher than the autofluorescence emitted by parental cells. After promoter induction with fluphenazine, the relative fluorescence emitted by CaCMR8 cells was 5.2-fold higher than that emitted in the absence of the inducing agent. This difference in expression was statistically significant (P < 0.001) (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Relative fluorescence of C. albicans cells before and after induction of efflux pump expression

| Strain | Mean ± SD fluorescence intensity (FL1)a (arbitrary units; logarithmic scale) for cells given the following treatment:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None (control) | Benomyl (10 μg/ml) | β-Estradiol (1 mM) | Fluphenazine (1 mg/ml) | |

| CaI4 | 30.27 ± 0.3 | 50.18 ± 7.35 | 35.09 ± 1.42 | 47.32 ± 2.22 |

| CaCMR4 | 76.94 ± 10.41 | 554.57 ± 22.73 | ||

| CaCMR7 | 44.27 ± 3.96 | 727.61 ± 52.05 | ||

| CaCMR8 | 50.07 ± 0.44 | 260.61 ± 17.37 | ||

Emitted by 10,000 cells per sample from three independent cultures.

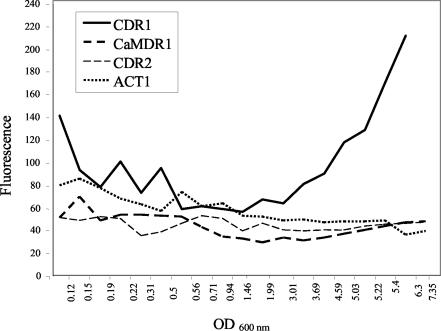

Growth stage and yEGFP expression.

As cells progressed through the different growth stages, the activity of the CaMDR1, ACT1, and CDR2 promoters remained stable (Fig. 3). Expression from the CDR1 promoter showed a higher degree of variation, decreasing as the culture progressed from lag to logarithmic phases and steeply increasing as the culture left logarithmic phase and entered stationary phase (Fig. 3). These results were consistent with those found by Harry et al. (11) and Krishnamurthy et al. (16) with RNA slot blots.

FIG. 3.

yEGFP expression during different growth stages. Relative fluorescence (FL1) emitted by CaCMR4 (CaMDR1 promoter), CaCMR5 (ACT1 promoter), CaCMR7 (CDR1 promoter), and CaCMR8 (CDR2 promoter) during late lag to logarithmic and stationary phases is shown.

Effect of adhesion on the expression of genes coding for efflux transport proteins.

Expression from the CaMDR1, CDR1, and CDR2 promoters was greater in adherent cells than in planktonic cells (Table 6). CaMDR1 and CDR2 expression was approximately twofold higher and CDR1 expression was fivefold higher in adherent cells versus planktonic cells. The fluorescence emitted by CaI4 (parental strain) and that emitted by CaCMR5 were similar for adherent cells and planktonic cells.

TABLE 6.

Effect of early adherence on gene expression

| Strain | Construct | Mean ± SD relative fluorescence (FL1)a (arbitrary units; logarithmic scale) of the following cells:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planktonic | Adherent | Adherent cell/planktonic cell ratio | ||

| CaI4 | Parental | 47.71 ± 0.62 | 51.89 ± 0.92 | 1 |

| CaCMR5 | CaMDR1 promoter-yEGFP | 98.89 ± 17 | 103.43 ± 11.3 | 0.95 |

| CaCMR4 | ACT1 promoter-yEGFP | 43.34 ± 0.33 | 93.56 ± 6.62 | 2.2 |

| CaCMR7 | CDR1 promoter-yEGFP | 42.29 ± 1.04 | 220.03 ± 3.34 | 5.2 |

| CaCMR8 | CDR2 promoter-yEGFP | 44.63 ± 0.45 | 73.9 ± 3.35 | 1.65 |

From three independent experiments. The Student t test reflected P values of 0.005 for CaCMR1, 0.0001 for CDR1, and 0.005 for CDR2, indicating 99% confidence.

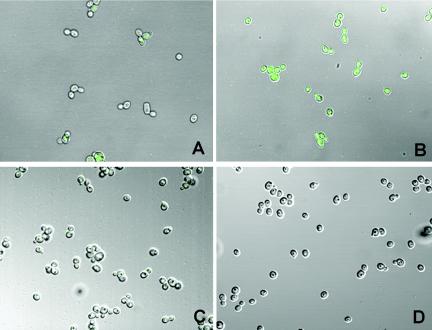

Additionally, epifluorescence microscopy analysis of C. albicans strains CaCMR4 and CaCMR7 adhering to glass microscope slides showed that upregulation of these efflux pump promoters occurred as early as 15 to 30 min after adhesion (Fig. 4). Planktonic cells of these strains and both planktonic cells and adherent cells of CaI4 did not fluoresce (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Epifluorescence micrographs of C. albicans CaCMR7 in the planktonic state (A) and 15 min after adherence (B) to glass slides, demonstrating increased expression from the CDR1 promoter after adherence. In contrast, CaI4 parental control cells in the planktonic (C) and adherent (D) states showed a lack of fluorescence.

The expression from the CaMDR1, CDR1, and CDR2 promoters in daughter cells of 24-h biofilms and in cells that were detached after an initial attachment period of 2 h and allowed to grow in a planktonic state for 24 h was statistically indistinguishable from the expression of these promoters in 24-h planktonic cultures (Table 7). After 48 h, the expression of CaMDR1 was twofold lower in daughter cells than in planktonic cells or detached cells. CDR1 expression in 48-h cultures (CaCMR7 cells) was up to 9.5-fold higher in planktonic cells and detached cells than in daughter cells (Table 7).

TABLE 7.

yEGFP expression in daughter cells

| Cell populationa | Mean ± SD relative fluorescence (FL1)b (arbitrary units; logarithmic scale) at:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| 24 h | 48 h | |

| CaCMR4 planktonic | 46 ± 7 | 83 ± 8c |

| CaCMR4 daughter | 50 ± 4.1 | 48 ± 8.8c |

| CaCMR4 detached | 49 ± 3.7 | 91.5 ± 13.7c |

| CaCMR7 planktonic | 141 ± 28 | 1,509 ± 93.2c |

| CaCMR7 daughter | 118 ± 9.8 | 160 ± 34.3c |

| CaCMR7 detached | 162.4 ± 6.6 | 1,765 ± 301c |

| CaCMR8 planktonic | 53 ± 6.5 | 94 ± 12 |

| CaCMR8 daughter | 50 ± 13.6 | 96 ± 5.2 |

| CaCMR8 detached | 50 ± 4.8 | 91.5 ± 14 |

Daughter, planktonic cells that were born from mature biofilms; detached, planktonic cells that were allowed to adhere to medical-grade silicone disks for 2 h prior to detachment.

From four independent experiments.

Results were statistically significantly different (P = 0.031 for CaCMR4 cells and P = 0.004 for CaCMR7 cells) between daughter cells and detached cells or planktonic cells of the same strain.

DISCUSSION

Both wild-type cells of C. albicans (Ca30) and CaI4 cells that adhered firmly to silicone disks within 2 h of attachment showed a 100-fold increase in tolerance to FCZ exposure over that of logarithmic-phase planktonic cells. Under microscopic examination, these cells were singular, without extracellular capsular material. Increased FCZ tolerance of adherent cells of Ca30 and CaI4 developed rapidly and was inherent to the bound cells.

Chandra et al. (3) found that C. albicans M-61 (clinical isolate) grown adherent to silicone disks did not develop a matrix (extracellular material) until after 12 to 24 h of incubation. We observed that adherent Ca30 and CaI4 cells achieved levels of FCZ tolerance similar to that of 24-h Ca30 and CaI4 biofilms, in which exopolymeric material and hyphal forms were visible upon microscopic observation. The similar percentages of permeation of firmly adherent and 24-h biofilm cells upon FCZ exposure suggest that the degree of adhesion selects for a resistance phenotype. All adherent cells, however, may not exhibit equivalent higher efflux pump activities. The numbers of cells with high efflux pump activities varied with the strain but always seemed to be much less than 10% the initial inoculum. We recorded comparable levels of uptake of Rh123 (a compound that is noninhibitory but is structurally similar to FCZ) in both adherent CaI4 cells and planktonic log-phase CaI4 cells, thus further excluding the presence of any physical barrier to FCZ surrounding adherent cells.

Moreover, cells detached from silicone after 2 h of adherence retained tolerance levels that were four- to eightfold higher than those seen in planktonic cells for up to 4 h after detachment. This retained tolerance was lower than that of adherent cells and could be attributed to the residual activity of transport proteins induced when the cells were firmly adherent to the substratum. These data further support earlier reports that biofilm structure is not required for the increased resistance to FCZ of surface-attached C. albicans (12, 13, 20, 31).

The significance of the CaMDR1p, Cdr1p, and Cdr2p transport proteins for FCZ resistance in both planktonic and adherent cells was evident in the detrimental effect that knockout of their genes had on the extent of FCZ tolerance acquired upon attachment. Strains lacking the CaMDR1 and CDR1 genes, both in the planktonic and in the adherent states, were significantly more susceptible to FCZ than parental strain CaI4. However, the contribution of CDR2 to the FCZ tolerance of planktonic and adherent C. albicans cells was minimal. These observations are in accordance with the results obtained by other investigators (4, 11, 20) studying the extent of the contribution of different genes to FCZ resistance in planktonic cultures.

From the study of knockout mutants, we were able to conclude that the impact of adhesion on FCZ tolerance correlated with the expression of CaMDR1 and particularly with that of CDR1 but not with the expression of CDR2. The expression of yEGFP from the CDR1 and CaMDR1 promoters was detected as early as 15 and 30 min after adhesion by epifluorescence microscopy, respectively, prior to cell replication on the substratum. We propose that either physical (i.e., direct contact with the substratum) or environmental signals encountered by adherent organisms induce the expression of at least two genes that contribute to the increased tolerance of adherent cells to FCZ.

Mukherjee et al. (20) reported that C. albicans biofilms expressed the CDR and MDRI genes in all developmental stages, as determined after 6, 12, and 48 h, and that biofilm sterol levels at 6 h were similar to those of planktonic cells but were decreased after 12 and 48 h. The authors observed that changes in sterol profiles coincided with apparent reduced pump activity and suggested that they may be a critical component in the azole resistance of biofilms. Similarly, we determined that the expression of the CaMDR1 and CDR1 genes was significantly lower in daughter cells from 48-h biofilms than in firmly adherent cells (2 h after attachment), suggesting that efflux pump expression in adherent cultures is transient.

From observations with knockout mutant cells, it appeared that CaMdr1p played a major role in the tolerance to FCZ of adherent cells. The absence of functional CaMdr1p in adherent DSY465 cells (Δcamdr1 CDR1) resulted in a lower resistance to FCZ, despite the existence of a functional CDR1 gene, than that recorded for adherent DSY449 cells (Δcdr1 CaMDR1). Nevertheless, it was expression from the CDR1 promoter that showed the greatest degree of upregulation after adhesion. A possible explanation for the higher level of expression of CDR1 than of CaMDR1 lies in the specificity of the two proteins. CaMdr1p is reportedly highly specific for FCZ transport (8), whereas Cdr1p has less substrate specificity (16). Consequently, CDR1 upregulation could provide the cell with a general defense mechanism.

In addition, the differences in yEGFP fluorescence levels were not due to the growth stage of the cells at the time of adhesion, since the expression of CaMDR1, CDR1, and CDR2 declined during mid-logarithmic phase, the time during which cells were adhering to the silicone disks. Also, all yEGFP fluorescence readings were taken from cells grown for 16 h from a very small inoculum (104 cells in 100 ml of medium). It is unlikely that pump expression was residual from any stationary-phase cells or a cellular response to fresh medium.

Our heterologous FCZ-resistant control strain produced negligible adhesion and biofilm formation under our test conditions and was unsuitable for direct comparisons with regard to adherence-induced tolerance. Nevertheless, cells with heterologous resistance could develop within a mature biofilm, thus adding to the complexity of mature biofilms. In summary, adherent cells deficient in drug efflux pump expression, were unable to achieve as high a level of tolerance to FCZ as adherent cells of wild-type strain Ca30 and parental strain CaI4. Expression from the CaMDR1 and CDR1 promoters was higher in adherent cells than in planktonic cells. These findings were generally similar to those of Mukherjee et al. (20). However, we were able to demonstrate that this change in FCZ tolerance as cells went from a planktonic state to a firmly adherent state was rapid, statistically significant, and remained for up to two generations after detachment from the initial firmly adherent state. The overall data indicated that the difference in FCZ susceptibility between planktonic and firmly adherent cells of the strains studied here was a consequence of the attachment process involving the expression of the CaMdr1p and Cdr1p efflux pumps.

We have performed extensive investigations to establish that the FCZ-susceptible strains of C. albicans studied here behave in a manner similar to that of well-studied strains in the literature with regard to FCZ resistance (13, 14, 20, 31). In general, FCZ resistance noted for cells in biofilms appears to be partially associated with surface-induced upregulation of drug efflux pumps (13). Our data from adhesion assays, flow cytometry, and epifluorescence microscopy suggest that this upregulation may be immediate upon attachment of a subset of cells with the capacity for firm adhesion to a substratum.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahearn, D. G., R. N. Borazjani, R. B. Simmons, and M. M. Gabriel. 1999. Primary adhesion of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to inanimate surfaces including biomaterials. Methods Enzymol. 310:551-557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baillie, G. S., and L. J. Douglas. 2000. Matrix polymers of Candida biofilms and their possible role in biofilm resistance to antifungal agents. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 46:397-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chandra, J., D. M. Kuhn, P. K. Mukherjee, L. L. Hoyer, T. McCormick, and M. A. Ghannoum. 2001. Biofilm formation by the fungal pathogen Candida albicans: development, architecture, and drug resistance. J. Bacteriol. 183:5385-5394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cowen, L. E., D. Sanglard, D. Calabrese, C. Sirjusinngh, J. Anderson, and L. M. Kohn. 2000. Evolution of drug resistance in experimental populations of Candida albicans. J. Bacteriol. 182:1515-1522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crump, J. A., and P. J. Collington. 2000. Intravascular catheter-associated infections. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 19:8-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Kievit, T., M. D. Parkins, R. J. Gillis, R. Srikumar, H. Ceri, K. Poole, B. H. Iglewski, and D. G. Storey. 2001. Multidrug efflux pumps: expression patterns and contribution to antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1761-1770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Douglas, L. J. 2003. Candida albicans biofilms and their role in infection. Trends Microbiol. 11:30-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fling, M. E., J. Kopf, A. Tamarkin, J. A. Gorman, H. A. Smith, and Y. Koltin. 1991. Analysis of a Candida albicans gene that encodes a novel mechanism for resistance to benomyl and methotrexate. Mol. Gen. Genet. 227:318-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fonzi, W. A., and M. Y. Irwin. 1993. Isogenic strain construction and gene mapping in Candida albicans. Genetics 134:717-728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gietz, R. D., and R. A. Woods. 2002. Transformation of yeast by the lithium acetate/single-stranded carrier DNA/PEG method. Methods Enzymol. 350:87-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harry, J. B., J. L. Song, C. N. Lyons, and T. C. White. 2002. Transcription initiation of genes associated with azole resistance to Candida albicans. Med. Mycol. 43:73-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hawser, S. P., and L. J. Douglas. 1995. Resistance of Candida albicans biofilms to antifungal agents in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:2128-2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jabra-Rizk, M. A., W. A. Falkler, and T. F. Meiller. 2004. Fungal biofilms and drug resistance. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 10:14-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jabra-Rizk, M. A., S. M. S. Ferreira, M. Sabet, W. A. Falkler, W. G. Merz, and T. F. Meiller. 2001. Recovery of Candida dubliniensis and other yeasts from human immunodeficiency virus-associated periodontal lesions. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:4520-4522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalya, A. V., and D. G. Ahearn. 1995. Increased resistance to antifungal antibiotics of Candida spp. adhered to silicone. J. Ind. Microbiol. 14:451-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krishnamurthy, S., V. Gupta, R. Prasad, S. L. Panwar, and R. Prasad. 1998. Expression of CDR1, a multidrug resistance gene of Candida albicans: transcriptional activation by heat shock, drugs and human steroid hormones. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 160:191-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.May, L. L., M. M. Gabriel, R. B. Simmons, L. A. Wilson, and D. G. Ahearn. 1995. Resistance of adhered bacteria to rigid gas permeable contact lens solutions. CLAO J. 21:242-246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller, M. J., and D. G. Ahearn. 1987. Adherence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to hydrophilic contact lenses and other substrata. J. Clin. Microbiol. 25:1392-1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morschhäuser, J., S. Michel, and J. Hacker. 1998. Expression of a chromosomally integrated, single-copy GFP gene in Candida albicans, and its use as a reporter of gene regulation. Mol. Gen. Genet. 257:412-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mukherjee, P. K., J. Chandra, D. M. Kuhn, and M. A. Ghannoum. 2003. Mechanism of fluconazole resistance in Candida albicans biofilms: phase-specific role of efflux pumps and membrane sterols. Infect. Immun. 71:4333-4340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pfaller, M. A., D. J. Diekema, R. N. Jones, H. S. Sader, A. C. Fluit, R. J. Hollis, and S. A. Messer. 2001. International surveillance of bloodstream infections due to Candida species: frequency of occurrence and in vitro susceptibility to fluconazole, ravuconazole, and voriconazole of isolates collected from 1997 through 1999 in the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3254-3259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramage, G., S. Bachmann, T. F. Patterson, B. L. Wickes, and J. L. López-Ribot. 2002. Investigation of multidrug efflux pumps in relation to fluconazole resistance in Candida albicans biofilms. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 49:973-980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramani, R., A. Ramani, and S. J. Wong. 1997. Rapid flow cytometric susceptibility testing of Candida albicans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:2320-2324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramani, R., and V. Chaturvedi. 2000. Flow cytometry antifungal susceptibility testing of pathogenic yeasts other than Candida albicans and comparison with the NCCLS broth microdilution test. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2752-2758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sanglard, D., F. Ischer, M. Monod, and J. Bille. 1996. Susceptibilities of Candida albicans multidrug transporter mutants to various antifungal agents and other metabolic inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2300-2305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanglard, D., F. Ischer, M. Monod, and J. Bille. 1997. Cloning of Candida albicans genes conferring resistance to azole antifungal agents: characterization of CDR2, a new multidrug ABC transporter gene. Microbiology 143:405-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tiraboschi, I. N., J. E. Bennett, C. A. Kauffman, J. H. Rex, C. Girmenia, J. D. Sobel, and F. Menichetti. 2000. Deep Candida infections in the neutropenic and non-neutropenic host: an ISHAM symposium. Med. Mycol. 38:199S-204S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Urban, M., T. Bhargava, and J. E. Hamer. 1999. An ATP-driven efflux pump is a novel pathogenicity factor in rice blast disease. EMBO J. 18:512-521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Warren, N. G., and K. C. Hazen. 1999. Candida, Cryptococcus and other yeasts of medical importance, p. 1184-1197. In P. R. Murray, E. J. Baron, M. A. Pfaller, F. C. Tenover, and R. H. Yolken (ed.), Manual of clinical microbiology, 8th ed. American Society for Microbiology, Washington D.C.

- 30.Watnik, P., and R. Kolter. 2000. Biofilm, city of microbes. J. Bacteriol. 182:2675-2679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.White, T. C. 2003. Mechanisms of resistance to antifungal agents, p. 1869-1879. In P. R. Murray, E. J. Baron, J. H. Jorgensen, M. A. Pfaller, and R. H. Yolken. (ed.), Manual of clinical microbiology, 8th ed. American Society for Microbiology, Washington D.C.