Abstract

Background: Decreased concentrations of amyloid-β 1-42 (Aβ42) in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and increased retention of Aβ tracers in the brain on positron emission tomography (PET) are considered the earliest biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). However, a proportion of cases show discrepancies between the results of the two biomarker modalities which may reflect inter-individual differences in Aβ metabolism. The CSF Aβ42/40 ratio seems to be a more accurate biomarker of clinical AD than CSF Aβ42 alone.

Objective: We tested whether CSF Aβ42 alone or the Aβ42/40 ratio corresponds better with amyloid PET status and analyzed the distribution of cases with discordant CSF-PET results.

Methods: CSF obtained from a mixed cohort (n = 200) of cognitively normal and abnormal research participants who had undergone amyloid PET within 12 months (n = 150 PET-negative, n = 50 PET-positive according to a previously published cut-off) was assayed for Aβ42 and Aβ40 using two recently developed immunoassays. Optimal CSF cut-offs for amyloid positivity were calculated, and concordance was tested by comparison of the areas under receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves (AUC) and McNemar’s test for paired proportions.

Results: CSF Aβ42/40 corresponded better than Aβ42 with PET results, with a larger proportion of concordant cases (89.4% versus 74.9%, respectively, p < 0.0001) and a larger AUC (0.936 versus 0.814, respectively, p < 0.0001) associated with the ratio. For both CSF biomarkers, the percentage of CSF-abnormal/PET-normal cases was larger than that of CSF-normal/PET-abnormal cases.

Conclusion: The CSF Aβ42/40 ratio is superior to Aβ42 alone as a marker of amyloid-positivity by PET. We hypothesize that this increase in performance reflects the ratio compensating for general between-individual variations in CSF total Aβ.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, amyloid-β, biomarker, cerebrospinal fluid, positron emission tomography

INTRODUCTION

Reduced concentrations of amyloid-β (Aβ) 1-42 in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) are associated with increased retention of Aβ tracers in the brain via positron emission tomography (PET) [1–5] and both are considered the earliest biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [6–10]. However, several published studies show that results of the two measures are discordant in a proportion of individuals in the cohorts evaluated to date, most notably as CSF Aβ42-abnormal/amyloid PET-normal (reviewed in [11]). Such discordance may reflect assay methodological variability and/or imprecision, or these biomarker modalities may reflect partly different pathophysiologic events [12].

Results from several groups demonstrate that normalization of the CSF Aβ42 concentration to the level of total Aβ peptides (or the most abundant isoform, Aβ 1-40 [Aβ40]) in the CSF by means of an Aβ42/40 ratio improves the accuracy of clinical AD diagnosis [13–17] by “controlling for” inter-individual differences in overall levels of CSF Aβ. This led us to hypothesize that the CSF concentration of Aβ42 depends not only on the pathophysiological status of a given individual, hence suggesting the presence or absence of AD pathology, but also on the total amount of Aβ peptides in the CSF, i.e., the total production of Aβ in the brain. At least two additional arguments, derived from experience regarding pre-analytical sample handling and data interpretation, further support the application of the Aβ42/40 ratio for AD diagnostic purposes: (a) Aβ42/40 is less prone to the error of misinterpretation when inappropriate test tubes to collect CSF are used [18] (likely due to the similar amount of absorption of both Aβ species); and (b) in two studies that applied the Aβ42/40 ratio measured with the same ELISA assays to predict AD in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) subjects [15] or in early symptomatic AD [19], virtually identical Aβ42/40 cut-offs were obtained despite differences in absolute Aβ42 concentrations.

Considering these data, we hypothesized that the CSF Aβ42/40 ratio might reflect amyloid PET status (positive versus negative) better than the Aβ42 concentration alone. To test this hypothesis, we used dichotomized PET results to calculate the optimal cut-offs for Aβ42 concentrations and Aβ42/40 ratios measured with two novel, recently validated ELISAs [14], and then compared the concordance of each of the two CSF biomarkers with the results of the amyloid PET. We also compared the distribution of the discordant results, i.e., the percentage of cases with pathologic CSF findings and normal PET results versus the percentage with normal CSF and pathologic PET results. We proposed that the results from these analyses might provide insight into the possible mechanism(s) for the observed known discordance between amyloid imaging and levels of CSF Aβ42 and, thus, may be informative for pathologic disease staging.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board and the Washington University Human Research Protection Office, and written informed consent was obtained from each participant. Participants were community-dwelling volunteers enrolled in studies of normal aging and dementia at the Knight Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC) at Washington University in St. Louis. Participants were 45–83 years of age at baseline and had no neurological, psychiatric or systemic medical illness that might compromise longitudinal study participation, nor medical contraindication to lumbar puncture (LP) or PET. All participants underwent cognitive assessments (including the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [20]), neurological evaluations and clinical assessments that included the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) [21].

To be included in the present analysis, baseline clinical and cognitive assessment, and LP and amyloid PET (via Pittsburgh Compound B, PiB) within 12 months of each other had to be available (mean±SD, 67±78 days). Two-hundred CSF samples were selected a priori based on cortical amyloid load via PET (25% amyloid PET-positive and 75% amyloid PET-negative, see below), independent of and blinded to participant demographics and clinical status. Given published reports of greater CSF-PET discordance in amyloid PET-negative individuals, greater numbers of amyloid-negative participant samples were evaluated so to enrich for possible and more common discordant (PiB-negative/Aβ42-positive) cases. APOE genotype was obtained from the Knight ADRC Genetics Core [22].

CSF collection, processing, and analysis

CSF was collected and processed according to standardized protocols. Samples (20–30 mL) were collected using LP procedures (22 G×3 1/2 inch atraumatic Sprotte spinal needle, Pajunk, #001151-30 C) via gravity drip into a 50 mL conical polypropylene tube (Corning #430829) at 8 : 00am after overnight fasting, gently inverted to avoid possible rostro-caudal gradient effects and immediately put on wet ice. Within 1 h of collection, samples were briefly centrifuged at low speed (2000×g, 5 min at 4°C) to pellet any cellular debris. All but the bottom 500 μL was transferred to a new 50 mL polypropylene tube, aliquoted (500 μL) into sterile 2 mL polypropylene screw-cap tubes with O-rings (Corning #430915), and immediately frozen at –80°C until analysis. The interval between sample collection and batch analysis varied from 1–9 years, with equal representation of storage intervals among the different amyloid PET groups (PiB+ versus PiB-). Samples underwent a single freeze-thaw cycle prior to assay, were thawed on wet ice (∼3 h) followed by vortexing prior to blinded analysis, and were run in duplicate. Aβ42 and Aβ40 concentrations were measured with immunoassays from IBL International (Hamburg, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. To be included in the statistical analyses, the results had to pass quality control (QC) criteria consistent with the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) study [23], including coefficients of variability (CV) of duplicates≤25% and the results of the kit’s run validation samples (“kit controls”) within the acceptable range as defined by the manufacturer. Samples also had data available for Aβ42, Tau, and pTau181 using INNOTEST ELISA kits (Fujirebio, Ghent, Belgium).

In vivo amyloid imaging

Participants received a single intravenous bolus injection of 11[C] PiB (between 4.7 and 19.0 mCi). PET imaging [24] was conducted with a Siemens 962 HR+ ECAT PET or Biograph 40 scanner (Siemens/CTI, Knoxville KY), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) using MPRAGE T1-weighted images (1 mm×1 mm×1.25 mm) was obtained for anatomic reference as described previously [25, 26]. Participants underwent a 60-min dynamic scan with 11[C] PiB, and PET data was processed using regions of interest (ROIs) derived from structural MRIs using Freesurfer [25, 26]. Regional time-activity curves were extracted for each ROI, and binding potentials were calculated using Logan graphical analysis [27] with cerebellar gray matter as the reference region. The mean cortical binding potential (MCBP) was calculated based on a set of selected cortical regions known to have high levels of deposition in AD [28], including precuneus, rostral middle frontal cortex, superior frontal cortex, superior temporal cortex, middle temporal cortex, lateral orbitofrontal cortex, and medial orbitofrontal cortex [25]. A MCBP cutoff of >0.18 for positivity was chosen to be consistent with prior studies [9, 28–30].

Statistical analyses

Sample size was calculated with the negative/positive ratio, power, and significance set to 3 : 1, 0.9, and 0.05, respectively, and the areas under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves (AUCs) of 0.974 (Aβ42/40) and 0.827 (Aβ42) [14]. Unless otherwise stated, results are presented as means±standard deviations (SD) or 95% confidence intervals (CI). CSF Aβ42 and Aβ42/40 cut-offs, and the corresponding sensitivities and specificities for PiB PET-positivity, were calculated based on the dichotomous PET grouping at the maximal Youden Indices, using a cut-off for PiB positivity of 0.18 [28]. Comparisons of continuous variables were performed with Student’s t-test or Welch test in cases of unequal variances; dichotomous variables were compared with chi-squared test. AUCs of the ROC curves were compared with DeLong test [32]. McNemar’s test for paired proportions was used for testing differences between the proportions of CSF-PiB concordant cases, and sensitivities and specificities. All tests were two-tailed. Logistic regression models were applied with logit of probability of PET-positivity (logit (πPET +)) as the outcome, and the CSF biomarkers and age as continuous, and APOE ɛ4 status (presence of ɛ4 allele = 1) and sex (males = 1) as dichotomous predictors. Covariates were selected either for epidemiological reasons (age, sex, APOE) or due to observed significances between PET+ and PET- groups (Aβ40 concentrations). Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare LP/PET intervals between “CSF/PET concordant” and “CSF/PET discordant” groups separately for Aβ42 and Aβ42/40. MedCalc 13.1 (MedCalc Software bvba, Ostend, Belgium) and Stata 14.1 (StatCorp, College Station, TX) were used for statistical analyses. Significance was defined as p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Demographic data and CSF biomarkers

As expected given the 3 : 1 (PiB-:PiB+) selection criterion based on amyloid PET positivity, the cohort was comprised of 88% cognitively normal (CDR 0) and 12% cognitively abnormal (CDR >0; n = 19 CDR 0.5, n = 3 CDR 1, n = 1 CDR 2) individuals. The cohort demographics and biomarker data are shown in Table 1. One sample did not pass QC so was excluded from statistical analysis. Not unexpectedly, the amyloid-positive (PiB+) group was older than the amyloid-negative (PiB–) group (p < 0.001), contained a higher percentage of APOE ɛ4 carriers (p < 0.01), and had a lower mean score on the MMSE (p = 0.02). The PiB- group contained a greater percentage of women than the PiB+ group (65% versus 43%, respectively), but there were no differences in the years of education (p = 0.28). Median absolute intervals between the time of CSF collection and PiB PET scan did not differ significantly between the two groups (24 versus 33 days, U = 3408, p = 0.45), and in both groups PET was performed before LP in similar proportions of the cases (36.7% and 38.7% of PET+ and PET- participants, respectively, χ2(1) = 0.058, p = 0.81).

Table 1.

Demographic and biomarker data

| Characteristic | PiB+ | PiB– | p |

| N | 49 | 150 | NA |

| Female, % | 43% | 65% | <0.01* |

| Age at LP, y | 72.4±7.3 | 64.2±9.6 | <0.001 |

| % APOE ɛ4 carriers | 58% | 31% | <0.01* |

| Education, y | 15.4±2.9 | 15.9±2.5 | 0.283 |

| MMSE | 28.00±3.03 | 29.07±1.21 | 0.02 |

| Median LP-PiB PET interval (IQR), days | 24 (16 –64) | 33 (12–94) | 0.45† |

| PiB MCBP | 0.5275±0.2454 | 0.0473±0.0502 | <0.001 |

| CSF Aβ40, pg/mL | 15 280±4 160 | 13 890±4 260 | 0.047 |

| CSF Aβ42, pg/mL | 577±184 | 887±292 | <0.001 |

| CSF Aβ42/40 | 0.038±0.009 | 0.065±0.013 | <0.001 |

| CSF Tau, pg/mL | 492±392 | 234±125 | <0.001 |

| CSF pTau181, pg/mL | 75.8±35.3 | 47.2±19.1 | <0.001 |

*χ2 test. †Mann-Whitney test. APOE, apolipoprotein E; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; IQR, interquartile range; LP, lumbar puncture; MCBP, mean cortical binding potential; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination (0–30, with 30 a perfect score) at clinical assessment closest in time to LP; NA, not applicable; PET, positron emission tomography; PiB, Pittsburgh Compound B. Unless otherwise indicated, values represent the mean±SD.

Inter-assay CVs, tested with two kit control samples, were 2.2% and 7.1% for Aβ40, and 2.3% and 6.5% for Aβ42. Median range-to-averages of the duplicate CSF samples measurements (expressing intra-assay variation) were 2.3% for Aβ40 and 2.5% for Aβ42.

By definition, the amount of cortical amyloid deposition (MCBP, mean±SD) was higher in the PiB+ compared to the PiB–group (p < 0.001). As expected, PiB+ participants had significantly lower concentrations of CSF Aβ42 (p < 0.001) and a lower mean Aβ42/40 ratio (p < 0.001), as well as significantly higher concentrations of CSF Tau (p < 0.001) and pTau181 (p < 0.001). Interestingly, the PiB+ group exhibited a modest but significantly higher mean concentration of CSF Aβ40 compared to the PiB- group (p = 0.047). Differences in LP/PET intervals between “CSF/PET concordant” and “CSF/PET discordant” groups were not significant (p > 0.1 for both CSF biomarkers).

Concordance between amyloid PET and CSF biomarkers

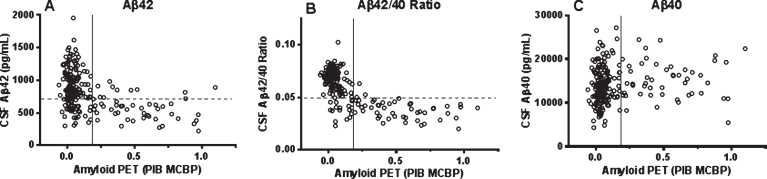

The relationships between CSF analyte values and cortical amyloid load (PiB MCBP) are shown in Fig. 1. The optimal CSF cut-offs that best differentiated the dichotomized PiB+ and PiB- groups were 735 pg/mL for Aβ42, 11,600 pg/mL for Aβ40, and 0.05 for the Aβ42/40 ratio. At these cut-offs, the Aβ40, Aβ42 concentrations and the Aβ42/40 ratio yielded sensitivities (with dichotomized PiB PET status defined as the reference) of 85.7% (CI: 72.8–94.1), 81.6% (CI: 68.0–91.2) and 95.9% (CI: 86.0–99.5), respectively, with the corresponding specificities of 34.0% (CI: 26.5–42.2), 72.0% (CI: 64.8–79.6), and 88.0% (CI: 81.7–92.7), corresponding to accuracies of 46.7% for Aβ40, 74.9% for Aβ42, and 89.4% for the Aβ42/40 ratio.

Fig.1.

Scatterplots of cortical amyloid PET load using [11C] PiB and concentrations of CSF Aβ42 (A), the Aβ42/40 ratio (B), and Aβ40 (C). Solid vertical line represents the a priori dichotomous cut-off for PiB positivity as published previously [28]. Dashed horizontal lines on panels A and B represent the best-performing cut-offs of the respective CSF biomarkers calculated in the present study.

For both Aβ42 and Aβ42/40, the percentage of cases with abnormal CSF findings but normal PET results (false positives: 20.6% and 9.0% for Aβ42 and Aβ42/40, respectively), clustering in the lower left quadrant of Fig. 1, was larger than the percentage of cases with normal CSF findings and abnormal PET (false negatives: 4.5% and 1.5% for Aβ42 and Aβ42/40, respectively), clustering in the upper right quadrant of Fig. 1. Detailed results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Analyses of concordance of CSF Aβ42 and the Aβ42/40 ratio with amyloid PET status

| Parameter | Aβ42 | Aβ42/40 |

| Cut-off at the max. YI | 735 pg/mL | 0.05 |

| Sensitivity at the max. YI (95% CI) | 81.6% (68.0–91.2) | 95.9% (86.0–99.5) |

| Specificity at the max. YI (95% CI) | 72.7% (64.8–79.6) | 88.0% (81.7–92.7) |

| Positive PV (95% CI) | 49.4% (38.1–60.7) | 72.3% (59.8–82.7) |

| Negative PV (95% CI) | 92.4% (86.0–96.5) | 98.5% (94.7–99.8) |

| Accuracy (concordance proportion) | 74.9% | 89.4% * |

| % False Pos. (N)/% False Neg. (N) | 20.6% (41)/4.5% (9) | 9.0% (18)/1.5% (3) |

| Area Under the ROC curve (95% CI) | 0.814 (0.752–0.865) | 0.936† (0.892–0.966) |

*p < 0.001 compared to the Aβ42 concentrations (McNemar test for paired proportions); †p < 0.001 compared to the Aβ42 concentrations (DeLong test for differences in AUC’s); False positive, abnormal CSF/normal PET; false negative, normal CSF/abnormal PET; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; PET, positron emission tomography; PV, predictive value; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; YI, Youden index.

McNemar test for paired proportions revealed a highly significantly larger proportion of Aβ42/40-PET concordant cases compared to Aβ42-PET concordant cases (χ2(1) = 19.56, p < 0.001), with an odds ratio of discordant cases of 5.14 (CI: 2.26 to 13.69).

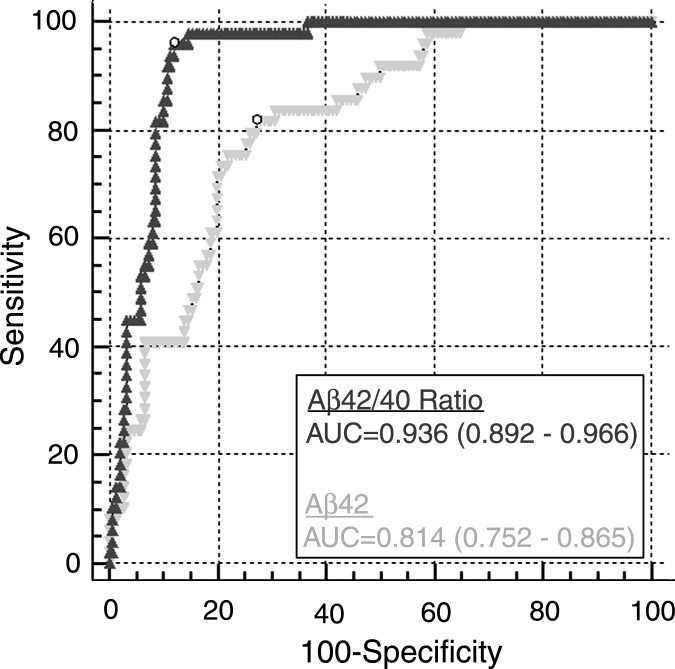

ROC curves yielded AUC’s of 0.599 for Aβ40, 0.814 for Aβ42 and 0.936 for the Aβ42/40 ratio (Fig. 2), with the Aβ42/40 ratio demonstrating significantly higher correspondence with PiB status compared to the concentrations of Aβ42 (p < 0.001) and Aβ40 (p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Fig.2.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of the CSF Aβ42 concentration and Aβ42/40 ratio. Values for areas under the ROC curves (AUC) correspond to mean±95% CI. Open circles represent the combinations of the sensitivities and the specificities at the maximal Youden Indices.

Logistic regression models

Logistic regression models are presented in Supplementary Table 1. In both models (with Aβ42 and Aβ42/40, respectively), when adjusted for Aβ40, age, APOE ɛ4 status, and sex, the effects of Aβ42 and Aβ42/40 remained highly significant (p < 0.001). Consistent with increased Aβ40 in the PiB+ group, the effect of Aβ40 was positive and significant (p < 0.001) in the Aβ42 model, but became non-significant in the Aβ42/40 model (p = 0.36). In both models, the effects of age were positive and significant. Male sex was a positive predictor but only with borderline significance, and presence of at least one APOE ɛ4 allele was a non-significant covariate in both models (p > 0.05).

DISCUSSION

The main finding in this study is significantly better concordance of the CSF Aβ42/40 ratio, compared to CSF Aβ42 alone, with cortical Aβ deposition as measured by [11C] PiB PET. This finding is consistent with our [14] and others’ [16, 17] reports of better diagnostic accuracy of the Aβ42/40 ratio compared to Aβ42 in early AD, as well as with CSF biomarkers of neurodegeneration, Tau and pTau181 [13]. We hypothesize that the concentration of Aβ42 in the CSF depends not only on the physiological amyloid status of a given individual (presence or absence of amyloid pathology) but also on the total amount of Aβ peptides that are present. By normalizing to the concentration of Aβ40, the most abundant Aβ species in the CSF, the ratio removes the potential confound of differences in overall Aβ concentration and provides a better index of underlying amyloid-related pathology. Two experimental observations further support the application of the Aβ42/40 ratio for AD diagnostics: (a) Aβ42/40 is less prone to the error of misinterpretation when non-polypropylene test tubes (as are often found in standard clinical LP trays) are used to collect CSF [18] likely due to the fact that both Aβ isoforms seem to absorb to the tube surface to a similar extent; and (b) two studies using a different set of ELISAs (produced by a currently non-existing vendor and based on N-terminally non-specific antibodies) that have applied the Aβ42/40 ratio to predict AD in MCI subjects [15] and discriminate early symptomatic AD from controls [19] reported almost identical Aβ42/40 cut-offs (0.095 and 0.098, respectively), whereas the corresponding cut-offs for Aβ42 alone differed by more than 15% (640 pg/mL and 550 pg/mL, respectively).

The analyses of CSF Aβ isoforms in the current study were performed with two novel assays that were validated recently by our group and approved for human in vitro diagnostic (IVD) use in Europe [14]. The assays exhibit very good analytical performance, both apply the same protocol for sample dilution, incubation, and washing steps, and require only a small volume (25 μL) of CSF for both biomarkers measured in duplicate. Interestingly, we observed small but significantly (p = 0.047) elevated levels of CSF Aβ40 in the PiB+ group compared to the PiB- group. This is consistent with similarly slight, but significant, increases observed in the MCI/AD group compared to controls when measured with the same assay [14]. Also, in a recent study by Dorey et al. [33] investigating the performance of these markers for correspondence with clinical diagnosis, CSF Aβ40 concentrations were higher in AD than non-AD patients, and inclusion of CSF Aβ40 as an Aβ42/40 ratio corrected 76.2% of misinterpreted cases in AD patients with normal CSF Aβ42 concentrations and 94.7% of cases when Aβ40 was used alone. When we adjusted for the Aβ42/40 ratio, but not for Aβ42 alone, the Aβ40 concentration became insignificant as a predictor of amyloid PET status in the logistic regression models, whereas both Aβ42 and the Aβ42/40 ratio remained highly significant as predictors of amyloid PET after adjustment for Aβ40, age, APOE ɛ4 carriage, and sex. After adjustment for other covariates, older age remained a significant predictor of cortical amyloid-PET positivity, consistent with age being the strongest risk factor for AD. Odds ratio of Aβ42-PET versus Aβ42/40-PET discordant cases, resulting from McNemar test, indicates that the odds to falsely predict the PET outcome is five-fold lower with the Aβ42/40 ratio compared to Aβ42 alone.

Both biomarker modalities (CSF analysis and amyloid PET) have their practical advantages and disadvantages in terms of cost (actual and reimbursable), perceived invasiveness, and availability in clinical as well as research settings [34], and our results do not endorse one or the other as a “gold standard” for amyloid biomarker positivity. From a scientific point of view, the discordance between CSF Aβ42 and amyloid PET (typically observed as false positives, i.e., abnormal/low CSF Aβ42 in the absence of amyloid-PET positivity) has been hypothesized to be due to possible methodological variability/limitations in the CSF assays, differences in the temporal trajectories of processes identified by the two biomarker modalities (e.g., CSF levels of soluble Aβ42 becoming abnormal prior to aggregated Aβ42 [amyloid] becoming detectable by PET), and/or inter-individual differences in overall levels of Aβ peptides [9, 12]. These possible scenarios are not mutually exclusive. Our use of well-performing assays that utilize the same dilution factor for both Aβ42 and Aβ40 minimizes methodological variability as a source of discordance between CSF Aβ42 and amyloid PET results and increases the confidence of the ratio as being an accurate measure of the proportion of each of these species in CSF. In so doing, the increase in concordance that we observe for the Aβ42/40 ratio suggests much of the “false positives” as defined by CSF Aβ42 is due to lower overall levels of Aβ in these individuals, whereas the “false negatives” can be attributed in large part to higher overall CSF Aβ levels. Indeed, the negative predictive value of the Aβ42/40 ratio in this study (98%) approached 100%, thus supporting its use for ruling out the presence of underlying amyloid pathology. While use of the ratio also significantly increased the positive predictive value for cortical amyloid PET positivity, 9% of individuals in this cohort were still classified as amyloid-positive by CSF Aβ42/40 but amyloid-negative by PET (false negative), consistent with CSF Aβ42 levels dropping prior to cortical amyloid being detectable by PiB PET. That all but one participant in this discordant group (whether CSF abnormality was defined by Aβ42 alone or the Aβ42/40 ratio) were cognitively normal is consistent with findings from a recent study in which low CSF Aβ42 but normal amyloid PET was much more frequent in cognitively normal individuals and early MCI cases than in the late MCI stage or AD dementia [12]. Longitudinal CSF and amyloid PET biomarker evaluation will be required to test whether levels of CSF Aβ42 indeed become abnormal (drop) before amyloid-positivity is detected with PET as has been suggested by a recent study by Vlassenko and colleagues [30]. That study, however, did not assess CSF Aβ40 so comparison of the two CSF measures was not possible. Results of a recent study by Palmqvist et al. also suggest that decreases in CSF Aβ42 precede alterations in amyloid PET [35]. Interestingly, another recent study using different ELISAs also reported better correspondence of the Aβ42/40 ratio with Aβ PET, however, with a higher proportion of Aβ–/PET+ individuals compared to the present study [36]. This discrepancy is likely due to the differences in the cohorts (higher numbers of cognitively normal individuals expected to be in the preclinical period in the current cohort) and/or different methodological issues. Another study reported no significant differences in concordances between Aβ42/40 and Aβ42 with amyloid PET, although the AUC for Aβ42/40 was slightly larger than that for Aβ42 alone [37]. This lack of significance might be attributed to the lower statistical power (a much smaller cohort, n = 38) and/or the use of different ELISAs and PET tracer (18F-flutemetamol) in that study. Similarly, another smaller study concluded that the Aβ42/40 ratio had a “large” effect size (defined as Cohen’s f2 = 0.35), compared to a “medium” effect size (defined as Cohen’s f2 = 0.15), for Aβ42, in predicting concurrent PiB burden [38]. Aggregation of soluble Aβ into diffuse, non-fibrillar plaques that are not identifiable by amyloid PET imaging may also contribute to the “false negative” discordant cases [39]. If confirmed, a finding of CSF alterations preceding those in PET would support the CSF Aβ42/40 ratio (and perhaps even Aβ42 alone, albeit with less accuracy) as the earliest detectable marker of β-amyloidosis.

Our study is not without limitations. Although amyloid PET in this study is considered to be the reference to define the presence of amyloid, positivity was defined according to dichotomous, research-based thresholds in a defined set of cortical regions. Also, since samples were specifically selected to over-represent possible CSF/PET discordance (by evaluating 25% PET-positive and 75% PET-negative cases), the cohort does not reflect the general distribution of amyloid PET positivity in the general population. Furthermore, because of this strategy, the cohort was significantly skewed toward cognitively normal individuals (88% cognitively normal, 12% cognitively abnormal). Additional study is needed in larger cohorts comprised of greater numbers of cognitively abnormal individuals, as well as those clinically diagnosed with non-AD dementias in order to better evaluate the CSF/PET concordance in non-AD populations. Finally, we performed statistical analyses of concordance after calculating optimal cut-off values for both CSF biomarkers. As this was designed to be a biomarker concordance study, independent of clinical status, the diagnostic value of any of the biomarkers and modalities studied here remains to be evaluated.

In summary, the CSF Aβ42/40 ratio performs better, compared to CSF Aβ42 alone, in identifying individuals with versus without underlying cortical amyloid as defined by PiB PET. The ratio outperforms the single Aβ42 measure in all metrics, including sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values, and overall accuracy. Of special note is its better concordance in individuals classified as amyloid-negative by PET, suggesting that the higher discordance between CSF Aβ42 alone and amyloid PET-positivity may reflect overall lower levels of Aβ42 in some individuals as opposed to its aggregation into plaques (or oligomeric forms that are likely not detected with the current assays [40]. The CSF Aβ42/40 ratio may, therefore, be useful as a proxy for amyloid status in AD clinical trials and eventually in clinical care settings.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by IBL International GmbH, Hamburg, Germany, and grants P50 AG05681, P01 AG03991 and P01 AG026276 from the National Institute on Aging/National Institute of Health (NIA/NIH) (JC Morris, PI). The sponsor and all coauthors participated in the design of the study, and in the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data; the sponsor had no influence on the decision to submit the paper for publication. The research leading to these results has received support from the Innovative Medicines Initiative Joint Undertaking under grant agreement nr. 115372, resources of which are composed of financial contribution from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) and EFPIA companies’ in kind contribution. PL was supported by the German Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (grant 01ED1203D) within the BiomarkAPD Project of the JPND. We cordially thank Michael Habig and Oliver Schmidt of IBL International for the development of the assays and extremely helpful discussions. We thank the research participants at the Knight Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC) and their families, as well as the members of the Knight ADRC Clinical, Biomarker, Genetics and Imaging Cores for providing data.

Authors’ disclosures available online (http://j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/16-0722r1).

Appendix

The supplementary material is available in the electronic version of this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/JAD-160722.

REFERENCES

- [1]. Fagan AM, Mintun MA, Mach RH, Lee SY, Dence CS, Shah AR, LaRossa GN, Spinner ML, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, DeKosky ST, Morris JC, Holtzman DM (2006) Inverse relation between in vivo amyloid imaging load and cerebrospinal fluid Abeta42 in humans. Ann Neurol 59, 512–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2]. Forsberg A, Engler H, Almkvist O, Blomquist G, Hagman G, Wall A, Ringheim A, Langstrom B, Nordberg A (2008) PET imaging of amyloid deposition in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Neurobiol Aging 29, 1456–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3]. Grimmer T, Riemenschneider M, Forstl H, Henriksen G, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, Shiga T, Wester HJ, Kurz A, Drzezga A (2009) Beta amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease: Increased deposition in brain is reflected in reduced concentration in cerebrospinal fluid. Biol Psychiatry 65, 927–934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4]. Tolboom N, van der Flier WM, Yaqub M, Boellaard R, Verwey NA, Blankenstein MA, Windhorst AD, Scheltens P, Lammertsma AA, van Berckel BN (2009) Relationship of cerebrospinal fluid markers to 11C-PiB and 18F-FDDNP binding. J Nucl Med 50, 1464–1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5]. Jagust WJ, Landau SM, Shaw LM, Trojanowski JQ, Koeppe RA, Reiman EM, Foster NL, Petersen RC, Weiner MW, Price JC, Mathis CA (2009) Relationships between biomarkers in aging and dementia. Neurology 73, 1193–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6]. Bateman RJ, Xiong C, Benzinger TL, Fagan AM, Goate A, Fox NC, Marcus DS, Cairns NJ, Xie X, Blazey TM, Holtzman DM, Santacruz A, Buckles V, Oliver A, Moulder K, Aisen PS, Ghetti B, Klunk WE, McDade E, Martins RN, Masters CL, Mayeux R, Ringman JM, Rossor MN, Schofield PR, Sperling RA, Salloway S, Morris JC (2012) Clinical and biomarker changes in dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med 367, 795–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7]. Buchhave P, Minthon L, Zetterberg H, Wallin AK, Blennow K, Hansson O (2012) Cerebrospinal fluid levels of beta-amyloid 1-42, but not of tau, are fully changed already 5 to 10 years before the onset of Alzheimer dementia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 69, 98–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8]. Sutphen CL, Jasielec MS, Shah AR, Macy EM, Xiong C, Vlassenko AG, Benzinger TL, Stoops EE, Vanderstichele HM, Brix B, Darby HD, Vandijck ML, Ladenson JH, Morris JC, Holtzman DM, Fagan AM (2015) Longitudinal cerebrospinal fluid biomarker changes in preclinical Alzheimer disease during middle age. JAMA Neurol 72, 1029–1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9]. Fagan AM, Mintun MA, Shah AR, Aldea P, Roe CM, Mach RH, Marcus D, Morris JC, Holtzman DM (2009) Cerebrospinal fluid tau and ptau(181) increase with cortical amyloid deposition in cognitively normal individuals: Implications for future clinical trials of Alzheimer’s disease. EMBO Mol Med 1, 371–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10]. Morris JC, Roe CM, Xiong C, Fagan AM, Goate AM, Holtzman DM, Mintun MA (2010) APOE predicts amyloid-beta but not tau Alzheimer pathology in cognitively normal aging. Ann Neurol 67, 122–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11]. Blennow K, Mattsson N, Scholl M, Hansson O, Zetterberg H (2015) Amyloid biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci 36, 297–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12]. Mattsson N, Insel PS, Donohue M, Landau S, Jagust WJ, Shaw LM, Trojanowski JQ, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Weiner MW, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (2015) Independent information from cerebrospinal fluid amyloid-beta and florbetapir imaging in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 138, 772–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13]. Wiltfang J, Esselmann H, Bibl M, Hüll M, Hampel H, Kessler H, Frölich L, Schröder J, Peters O, Jessen F, Luckhaus C, Perneczky R, Jahn H, Fiszer M, Maler JM, Zimmermann R, Bruckmoser R, Kornhuber J, Lewczuk P (2007) Amyloid beta peptide ratio 42/40 but not A beta 42 correlates with phospho-Tau in patients with low- and high-CSF A beta 40 load. J Neurochem 101, 1053–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14]. Lewczuk P, Lelental N, Spitzer P, Maler JM, Kornhuber J (2015) Amyloid β 42/40 CSF concentration ratio in the diagnostics of Alzheimer’s disease: Validation of two novel assays. J Alzheimers Dis 43, 183–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15]. Hansson O, Zetterberg H, Buchhave P, Andreasson U, Londos E, Minthon L, Blennow K (2007) Prediction of Alzheimer’s disease using the CSF Abeta42/Abeta40 ratio in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 23, 316–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16]. Slaets S, Le Bastard N, Martin JJ, Sleegers K, Van Broeckhoven C, De Deyn PP, Engelborghs S (2013) Cerebrospinal fluid Abeta1-40 improves differential dementia diagnosis in patients with intermediate P-tau181P levels. J Alzheimers Dis 36, 759–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17]. Beaufils E, Dufour-Rainfray D, Hommet C, Brault F, Cottier JP, Ribeiro MJ, Mondon K, Guilloteau D (2013) Confirmation of the amyloidogenic process in posterior cortical atrophy: Value of the Abeta42/Abeta40 ratio. J Alzheimers Dis 33, 775–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18]. Lewczuk P, Beck G, Esselmann H, Bruckmoser R, Zimmermann R, Fiszer M, Bibl M, Maler JM, Kornhuber J, Wiltfang J (2006) Effect of sample collection tubes on cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of tau proteins and amyloid beta peptides. Clin Chem 52, 332–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19]. Lewczuk P, Esselmann H, Otto M, Maler JM, Henkel AW, Henkel MK, Eikenberg O, Antz C, Krause WR, Reulbach U, Kornhuber J, Wiltfang J (2004) Neurochemical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s dementia by CSF Aβ42, Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio and total tau. Neurobiol Aging 25, 273–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20]. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR (1975) “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12, 189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21]. Morris JC (1993) The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): Current version and scoring rules. Neurology 43, 2412–2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22]. Pastor P, Roe CM, Villegas A, Bedoya G, Chakraverty S, Garcia G, Tirado V, Norton J, Rios S, Martinez M, Kosik KS, Lopera F, Goate AM (2003) Apolipoprotein Eepsilon4 modifies Alzheimer’s disease onset in an E280A PS1 kindred. Ann Neurol 54, 163–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23]. Shaw LM, Vanderstichele H, Knapik-Czajka M, Figurski M, Coart E, Blennow K, Soares H, Simon AJ, Lewczuk P, Dean RA, Siemers E, Potter W, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ (2011) Qualification of the analytical and clinical performance of CSF biomarker analyses in ADNI. Acta Neuropathol 121, 597–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24]. Klunk WE, Engler H, Nordberg A, Wang Y, Blomqvist G, Holt DP, Bergstrom M, Savitcheva I, Huang GF, Estrada S, Ausen B, Debnath ML, Barletta J, Price JC, Sandell J, Lopresti BJ, Wall A, Koivisto P, Antoni G, Mathis CA, Langstrom B (2004) Imaging brain amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease with Pittsburgh Compound-B. Ann Neurol 55, 306–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25]. Su Y, D’Angelo GM, Vlassenko AG, Zhou G, Snyder AZ, Marcus DS, Blazey TM, Christensen JJ, Vora S, Morris JC, Mintun MA, Benzinger TL (2013) Quantitative analysis of PiB-PET with FreeSurfer ROIs. PLoS One 8, e73377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26]. Su Y, Blazey TM, Snyder AZ, Raichle ME, Marcus DS, Ances BM, Bateman RJ, Cairns NJ, Aldea P, Cash L, Christensen JJ, Friedrichsen K, Hornbeck RC, Farrar AM, Owen CJ, Mayeux R, Brickman AM, Klunk W, Price JC, Thompson PM, Ghetti B, Saykin AJ, Sperling RA, Johnson KA, Schofield PR, Buckles V, Morris JC, Benzinger TL, Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer N (2015) Partial volume correction in quantitative amyloid imaging. Neuroimage 107, 55–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27]. Logan J, Fowler JS, Volkow ND, Wolf AP, Dewey SL, Schlyer DJ, MacGregor RR, Hitzemann R, Bendriem B, Gatley SJ, et al. (1990) Graphical analysis of reversible radioligand binding from time-activity measurements applied to [N-11C-methyl]-(-)-cocaine PET studies in human subjects. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 10, 740–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28]. Mintun MA, Larossa GN, Sheline YI, Dence CS, Lee SY, Mach RH, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, DeKosky ST, Morris JC (2006) [11C]PIB in a nondemented population: Potential antecedent marker of Alzheimer disease. Neurology 67, 446–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29]. Vlassenko AG, Mintun MA, Xiong C, Sheline YI, Goate AM, Benzinger TL, Morris JC (2011) Amyloid-beta plaque growth in cognitively normal adults: Longitudinal [11C]Pittsburgh compound B data. Ann Neurol 70, 857–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30]. Vlassenko AG, McCue L, Jasielec MS, Su Y, Gordon BA, Xiong C, Holtzman DM, Benzinger TL, Morris JC, Fagan AM (2016) Imaging and cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in early preclinical alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol 80, 379–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31]. Fischl B, van der Kouwe A, Destrieux C, Halgren E, Segonne F, Salat DH, Busa E, Seidman LJ, Goldstein J, Kennedy D, Caviness V, Makris N, Rosen B, Dale AM (2004) Automatically parcellating the human cerebral cortex. Cereb Cortex 14, 11–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32]. DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL (1988) Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: A nonparametric approach. Biometrics 44, 837–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33]. Dorey A, Perret-Liaudet A, Tholance Y, Fourier A, Quadrio I (2015) Cerebrospinal fluid Abeta40 improves the interpretation of Abeta42 concentration for diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease. Front Neurol 6, 247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34]. Lewczuk P, Kornhuber J (2016) Do we still need positron emission tomography for early Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis? Brain, doi: 10.1093/brain/aww168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35]. Palmqvist S, Mattsson N, Hansson O, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (2016) Cerebrospinal fluid analysis detects cerebral amyloid-beta accumulation earlier than positron emission tomography. Brain 139(Pt 4), 1226–1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36]. Janelidze S, Zetterberg H, Mattsson N, Palmqvist S, Vanderstichele H, Lindberg O, van Westen D, Stomrud E, Minthon L, Blennow K, Swedish BioFINDER study group, Hansson O (2016) CSF Abeta42/Abeta40 and Abeta42/Abeta38 ratios: Better diagnostic markers of Alzheimer disease. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 3, 154–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37]. Adamczuk K, Schaeverbeke J, Vanderstichele HM, Lilja J, Nelissen N, Van Laere K, Dupont P, Hilven K, Poesen K, Vandenberghe R (2015) Diagnostic value of cerebrospinal fluid Abeta ratios in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther 7, 75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38]. Racine AM, Koscik RL, Nicholas CR, Clark LR, Okonkwo OC, Oh JM, Hillmer AT, Murali D, Barnhart TE, Betthauser TJ, Gallagher CL, Rowley HA, Dowling NM, Asthana S, Bendlin BB, Blennow K, Zetterberg H, Carlsson CM, Christian BT, Johnson SC (2016) Cerebrospinal fluid ratios with Abeta42 predict preclinical brain beta-amyloid accumulation. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2, 27–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39]. Cairns NJ, Ikonomovic MD, Benzinger T, Storandt M, Fagan AM, Shah AR, Reinwald LT, Carter D, Felton A, Holtzman DM, Mintun MA, Klunk WE, Morris JC (2009) Absence of Pittsburgh compound B detection of cerebral amyloid beta in a patient with clinical, cognitive, and cerebrospinal fluid markers of Alzheimer disease: A case report. Arch Neurol 66, 1557–1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40]. Englund H, Degerman Gunnarsson M, Brundin RM, Hedlund M, Kilander L, Lannfelt L, Pettersson FE (2009) Oligomerization partially explains the lowering of Abeta42 in Alzheimer’s disease cerebrospinal fluid. Neurodegener Dis 6, 139–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The supplementary material is available in the electronic version of this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/JAD-160722.