Abstract

Purpose of review

Atherosclerosis is the leading cause of death globally. The pathophysiology of atherosclerosis is not fully understood. Recent studies suggest dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP4), a regulator of inflammation and metabolism, may be involved in the development of atherosclerotic diseases. Recent advances in the understanding of DPP4 function in atherosclerosis will be discussed in this review.

Recent findings

Multiple pre-clinical and clinical studies suggest DPP4/GLP-1 axis is involved in the development of atherosclerotic disease. However, several recent trials assessing the cardiovascular effects of DPP4 inhibition indicate enzymatic inhibition of DPP4 lacks beneficial effects on cardiovascular disease.

Summary

Catalytic inhibition of DPP4 with DPP4i alters pathways that could favor cardioprotection. GLP-1R-independent aspects of DPP4 function may contribute to the overall neutral effects on cardiovascular outcome seen in the outcome trials.

Keywords: Dipeptidyl peptidase, incretin, atherosclerosis, glucagon-like peptide-1, diabetes

Introduction

Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP4, also known as CD26) is a membrane glycoprotein that has recently gained attention owing to its role in the catalytic degradation of incretins. In this review, we will summarize the structure and function of DPP4 and its known roles in cardiovascular physiology and atherosclerosis. We will provide perspectives on clinical trials of DPP4 inhibition and review recent data from both mechanistic studies and outcome driven trials.

DPP4 Structure, Function and Regulation

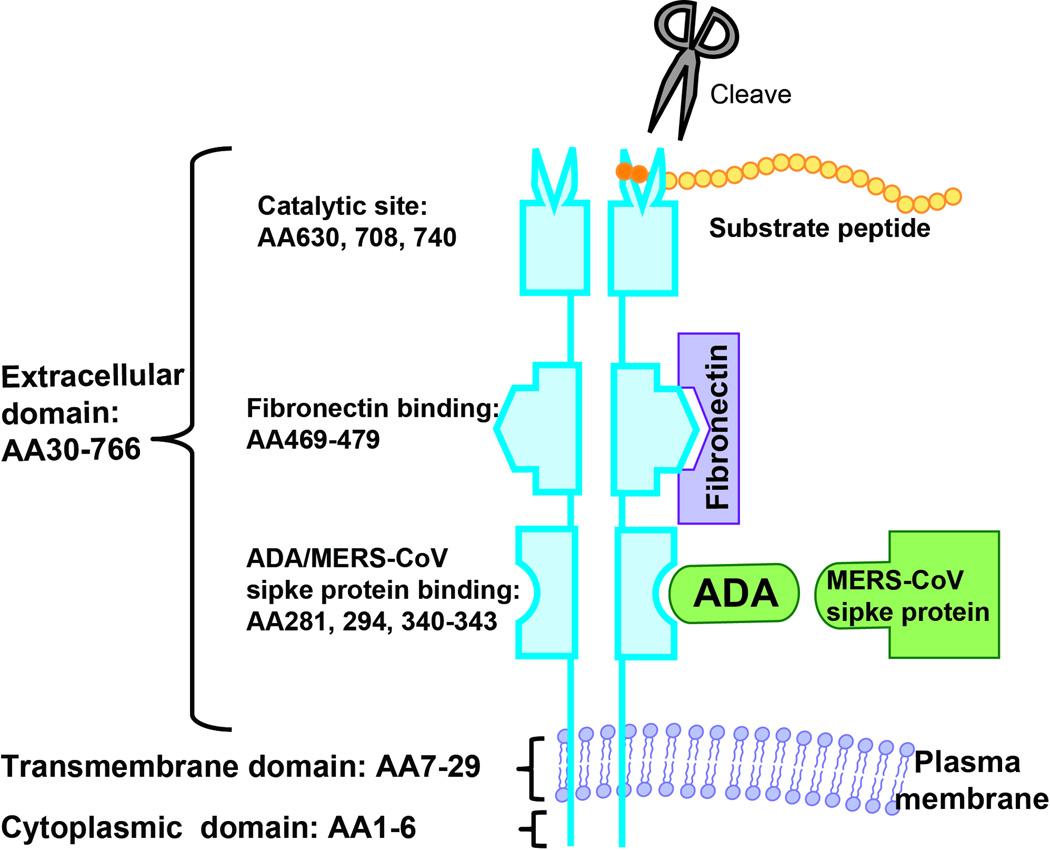

DPP4 is a transmembrane glycoprotein dipeptidase that cleaves N-terminal dipeptides from proteins with proline or alanine as the penultimate position. DPP4 is highly conserved among species and forms a homodimer or tetramer on the plasma membrane. DPP4 has a 6-amino-acid N-terminal cytoplasmic domain (AA1-6), a 22-residue transmembrane domain (AA7-29) and a large C-terminal extracellular domain (Figure 1). The extracellular domain contains an α/β-hydrolase domain, an eight-blade β-propeller domain and is responsible for its dipeptidase function and binding to proteins such as adenosine deaminase (ADA) and fibronectin. DPP4 is widely expressed particularly on endothelium, epithelium, and immune cell populations. The extracellular domain of DPP4 may be cleaved and circulate in the plasma where it contributes to the most of plasma DPP4 activity. DPP4 activity and concentration correlates with Type 2 diabetes (T2DM) and atherosclerosis[1,2]. The bone marrow contribution to soluble DPP4 is substantial with nearly 43% of soluble DPP4 originating from the bone marrow in experimental models[3].

Figure 1. DPP4 molecular structure and interaction with other molecules.

DPP4 consists of a short cytoplasmic domain, a transmembrane domain, and a large extracellular domain which is responsible for its catalytic activity and binding to a number of ligands. It usually forms a dimer on the cell membrane. AA, amino acid; ADA, adenosine deaminase; MERS-CoV, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus.

While the regulation of DPP4 expression is not fully understood, there is definite evidence for its regulation by inflammatory mediators. DPP4 promoter region also contains a GAS (interferon gamma-activated sequence) motif which is a binding site of STAT1α. STAT1α activation by interferons and retinoic acid leads to the binding of STAT1α to the GAS motif and DPP4 transcription[4]. IL-12 enhances the translation but not transcription of DPP4 in activated lymphocytes, while TNFα decreases expression of DPP4, suggesting that DPP4 translation and translocation is regulated by cytokines such as IL-12 and TNFα[5]. IL-1α has also been shown to upregulates the expression of DPP4[6,7].

Dipeptidase Activity of DPP4

Incretin peptides such as glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) are responsible for the modulation of postprandial blood glucose by promoting insulin secretion from pancreatic β cells and via glucagonostatic effects. GLP-1 and GIP are rapidly inactivated by DPP4, leading to a short half-life (minutes for both GLP-1 and GIP). Mice lacking DPP4 are protected from the development of diet-induced obesity and demonstrate improved postprandial glucose control[8,9]. Pharmacological inhibition of DPP4 enzymatic activity improved glucose tolerance in wild-type, but not in Dpp4−/− mice. inhibition also improved glycemic control in Glp1r−/− mice, suggesting additional mechanisms for DPP4 inhibition-mediated anti-hyperglycemic effect[9]. In addition to incretin peptides, DPP4 also cleaves a number of other proteins. The physiologic targets include GLP1, GLP2, Brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), Peptide YY, stromal-cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1), Erythropoietin, Granulocyte Colony Stimulating Factor (G-CSF) and Substance P(3–11). The catalytic activity of DPP4 has been extensively reviewed and will not be discuss it in detail here[10].

Stromal derived factor-1 (SDF-1) is a physiologic target that serves as a chemoattractant for bone marrow stem cells [such as hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell, endothelial progenitor cell (EPC), and mesenchymal stem cell] and endogenous cardiac stem cells through its cognate receptor CXCR4. Preservation of SDF-1 by DPP4 inhibition has been shown to promote stem cell repopulation and homing to ischemic tissues. SDF-1 levels increase in plasma and in ischemic tissue shortly after ischemic injury, in response to hypoxia, which in turn up regulates HIF-1α[11]. HIF-1α up-regulates SDF-1 by binding to the promoter of SDF-1[12]. Disease states such as diabetes associated with up-regulation of DPP4, may represent conditions associated with defective homing and integration of EPCs owing to rapid degradation of SDF-1 in both plasma and ischemic heart tissue[13,14]. An improvement in EPC number and endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression after DPP4 inhibition has been previously demonstrated[15]. Thus DPP4 inhibitors (DPP4i) may have the ability to enhance SDF-1/CXCR4 responsiveness and may improve the SDF-1 mediated stem cell homing post-myocardial infarction. This however remains to be tested in humans[16*]. A significant correlation between DPP4 and HbA1c has been observed in type 2 diabetic subjects who also demonstrated higher DPP4 activity than controls or those with impaired glucose tolerance[17].

Non-Catalytic Function of DPP4 and Role in Inflammation and Atherosclerosis

DPP4 has been known to play a role in T-cell activation and functional modulation of antigen presenting cell function. Activation of DPP4 by anti-DPP4 antibodies and recognition of ADA-binding epitopes enhances T cell activation, proliferation, and cytokine production. Cross-linking by anti-DPP4 antibody induces tyrosine phosphorylation of signaling molecules downstream of T cell receptor/CD3. Upon binding to DPP4, caveolin-1, a plasma membrane protein is phosphorylated, resulting in the phosphorylation of IRAK-1 and activation of NF-kappa B (NFκB)[10**]. The interaction between DPP4 and caveolin-1 has been reported to be involved in the pathogenesis of arthritis but could be important in atherosclerosis[18]. DPP4 can bind components of extracellular matrix such as collagen and fibronectin, with these interactions potentially playing a role in sequestration of DPP4 and matrix remodeling. sDPP4 has also been shown to independently modulate inflammation via the activation of ERK1/2 and NFκB. The effects could be inhibited via silencing of protease activated receptor-2 (PAR2) suggesting a novel role pro-inflammatory role for the soluble fraction[19]. Interaction between DPP4 and ADA may facilitate T cell activation by providing a suitable microenvironment for T cell proliferation. By anchoring ADA on cell surface, DPP4 modulates peri-cellular adenosine and thus regulates T cell activation. We have recently demonstrated that DPP4 expressed on adipose tissue macrophages is also involved in adipose inflammation and insulin resistance by interacting with ADA[2]. Expression of DPP4 on adipose tissue macrophages was higher than that in circulation and was increased in obese and insulin resistant patients. DPP4 on antigen presenting cells including macrophages and dendritic cells facilitated T cell proliferation and activation through its non-catalytic activity, as catalytic inhibition of DPP4 or addition of exogenous sDPP4 did not affect their capability to stimulate T cell. Antigen presenting cell-expressing DPP4 was able to bind ADA and promote T cell activation via removal of suppressive effect of adenosine[2]. In a very early study, DPP4 was found to be expressed in atherosclerotic plaque, associated with T cells and the levels of expression correlated with acute coronary syndrome presentation. Circulating DPP4 activity has been reported to be increased in patients with obesity and T2DM, positively correlating with HbA1c levels, degree of obesity and measures of insulin resistance and inflammation[17,20].

Effects of DPP4 Inhibition in Cardiovascular Disease

There are currently four DPP4i (“gliptins”) approved by the FDA and several others available in Europe/Japan/Korea (Table 1), which may be broadly divided into two classes based on structure: DPP4 peptide mimetics and non-peptidomimetics. Gliptins selectively inhibit the enzymatic activity of DPP4 (IC50: 19 nM for sitagliptin, 62 nM for vildagliptin, 50 nM for saxagliptin , 24 nM for alogliptin, and 1 nM for linagliptin) and do not interfere with other member of the DPP family including DPP8 and DPP9. Continued inhibition of >70% plasma DPP4 activity is noted with most approved agents even after 24 hours. The once weekly DPP4 inhibitors provide durable control of HBA1c although their effects appear to be modest but could be important from diabetes prevention stand-point with potential utility in the pre-diabetic. The glycemia lowering efficacy of all DPP4i is roughly comparable and may range from a decrease of 0.4–1.0% in HbA1c. Substantial differences in individual responses have been noted[21*].

Table 1.

DPP4 inhibitors in the market or under development/approval for the treatment of type 2 diabetes

| Pharmacological Agent |

Manufacturer | Long Acting/ Short Acting |

Half-life (t ½) |

Dosage | Dosing Frequency | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Approved DPP4i | ||||||

| Sitagliptin | Merck | Short-acting | 8–24 hours |

100 mg | Once Daily | FDA-approved |

| Alogliptin | Takeda | Short-acting | 12–21 hours |

25–50 mg |

Once Daily | FDA-approved |

| Linagliptin | Boehringer Ingelheim |

10–40 hours |

5 mg | Once daily | FDA-approved | |

| Saxagliptin | BMS & Astra Zeneca |

2–4 hours | 2.5–5 mg | Once daily | FDA-approved | |

| Vildagliptin | Novartis | 1.5–4.5 hours |

50 mg | Twice daily | Approved in European |

|

| Omarigliptin (MK-3102) |

Merck | Long-acting | 68 hours | 25 mg | Once Weekly | Approved in Japan |

| Gemigliptin | LG Life Sciences NOBEL |

Short-acting | 16.6 – 20.1 hours |

50 mg | Once Daily | Approved in Korea |

| Trelagliptin (SYR- 472) |

Furiex Pharmaceuticals and Takeda |

Long-acting (once weekly) |

38–52 hours |

25–100 mg |

Once Weekly | Approved in Japan |

| Anagliptin | Sanwa Kagaku Kenkyusho |

Short-acting | 4.37 hours | 100 mg | Once Daily | Approved in Japan |

| Teneligliptin | Mitsubishi Tanabe |

Short-acting | 24.8 hours | 20 – 40 mg |

Once Daily | Approved in Japan and Korea |

| DPP4i under development or approval | ||||||

| Dutogliptin | Phenomix Corp | Short-acting | 10 – 13 hours |

200 – 400 mg |

Once Daily | Phase 3 |

| Gosogliptin | Pfizer | Short-acting | - | 5 – 20 mg |

Once Daily | Phase 3 |

| Evogliptin (DA-1229) |

Dong-A | Short-acting | 33 – 39 hours |

5 mg | Once Daily | Phase 2 |

Direct cardiac effects of DPP4 inhibition

There is good evidence that DPP4 inhibition mediates cardiovascular protective effects in models of myocardial infarction, atherosclerosis and heart failure. DPP4 is expressed in the post infarct heart at higher levels particularly in the border zone as well as the failing heart. DPP4 expression and activity is positively associated with body weight in adult dog and significantly higher with the degree of heart failure[22]. Survival rate and infarct size significantly improved in Dpp4−/− mice after LAD ligation, accompanied by enhanced expression of pro-survival signal pathways such as pAKT, pGSK3β, and atrial natriuretic peptide in cardiac tissue[23]. Pharmacologic inhibition with sitagliptin enhances expression of cardioprotective proteins and improved functional recovery after ischemia-reperfusion injury in the murine heart[23]. Both pharmacological and genetic DPP4 inhibition reversed diabetic diastolic left ventricular dysfunction and fibrosis but not pressure-overload-induced left ventricular dysfunction in mice[24]. A number of effects such as induction of pro-survival pathways seen in response to DPP4 inhibition have been postulated to occur via activation of GLP-1R signaling[25]. The engagement of GLP-1R (a G protein–coupled receptor) leads to the activation of adenylate cyclase through stimulatory Gs subunit, and subsequent accumulation of cAMP at least in classical organs such as the beta cell[25]. However a GLP-1R-independent mechanism, via the GLP-1(9–36) degradation product has also been suggested. In Glp1r−/− mice, GLP-1 (9–36) limits infarct size and promotes cardiomyocyte survival after ischaemia–reperfusion injury, by activating PI3 K and MAPK1/2 signaling pathways, suggesting the existence of different receptor(s) able to bind the cleaved form of GLP-1. Mulvihill et al. recently reported substantial differences between genetic deficiency of DPP4 which results in a cardioprotective phenotype characterized by reduction in LVH, improved LV ejection fraction and functional indices of improved exercise tolerance in mice following transverse aortic constriction. This was associated with reduced fibrosis but with paradoxic upregulation of markers of inflammation. In contrast pharmacologic inhibition of DPP4 by MK-0626 resulted in impaired cardiac function and cardiac hypertrophy, suggesting that the enzymatic inhibition of DPP4 alone may not be sufficient to reduce cardiac fibrosis. Additionally drug-related non-specific effects cannot be ruled out [26**]. These results are also different from results from an papers where pharmacologic inhibition of DPP4 with sitagliptin or alogliptin was shown to be protective[23][27*]. While some of the studies may reflect differences in models of diabetes, strain susceptibility and differential impact of diet, it is important to consider that DPP4−/− mice are models of global DPP4 deficiency and do not represent catalytic inactivation of DPP4 that occurs with pharmacologic models of DPP4 inhibition. Further, there are differences in DPP4 structure between mouse and humans that may result in differences such as ADA binding that may have substantial implications for translating findings from animal models to humans[10**]. In open label studies of patients with T2DM and existing coronary artery disease undergoing dobutamine stress echocardiography, protection against ischemia induced alterations in left ventricular function and peak systolic velocity have been observed in humans with DPP4 inhibition suggesting acute cardioprotection against ischemia induced contractile dysfunction presumagbly related to GLP-1 elevation (sitagliptin, single dose or 4 weeks of treatment)[28,29]. In a double blind long term study of Vildagliptin in Ventricular Dysfunction Diabetes (VIVIDD), in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, although there were no differences in left ventricular ejection fraction following 1 year of treatment, an increase in left ventricular end-diastolic volume was reported for patients randomized to vildagliptin[25]. Interestingly, improvement was noted in NT-BNP levels in the study. These studies collectively indicate complex effects of catalytic inhibition that are difficult to reconcile readily. Certainly the possibility of substantial differences between individual DPP4 inhibitors needs to be entertained.

Effects of DPP4 inhibition on vascular function and blood pressure

The results of DPP4 inhibition on endothelial function have been inconsistent. Part of the variability may reflect differences in protocol, including methodologies to measure endothelial function which are notoriously difficult to replicate and often differ from patient to patient. Treatment with vildagliptin for 4 weeks in patients with type 2 diabetes improved forearm blood vasodilator responses to intra-arterially administered acetylcholine, but not to sodium nitroprusside[30]. Sitagliptin treatment for 12 weeks significantly improved flow-mediated dilatation in diabetic patients uncontrolled on sulfonylurea, metformin or pioglitazone treatment[31]. In contrast, another study demonstrated that the flow-mediated dilation was suppressed by both sitagliptin and alogliptin[32]. In a recent study acute DPP4 inhibition did not potentiate vasodilatory responses to infused GLP-1 and BNP in healthy subjects[33]. The significance of these findings and how applicable these are to the diabetic on long term DPP4 inhibitors remain questionable. DPP4 inhibitors unlike GLP-1 agonists do not appear to have blood pressure lowering effects. The blood pressure lowering effects of GLP-1 agonists have been attributed to direct vasorelaxant effects of GLP-1, natriuretic mechanisms and central nervous system mechanisms[34]. The reason for the lack of BP lowering effects with DPP4 inhibition may simply relate to the magnitude of GLP-1 elevation compared to pharmacologic strategies of GLP-1 agonism. Another mechanism that has been raised is that under conditions of high DPP4, peptide YY (1–36) is converted to peptide YY (3–36). PYY1-36 through activation of Y-1 receptor may potentiate angiotensin II signaling. Definite data to support this in humans is however lacking.

Effects of DPP4 inhibition on lipoprotein metabolism

The lipoprotein effects of GLP-1R agonists and DPP4i, have also been reviewed in detail in prior reviews[16*]. Although prior small studies that have examined effects on post-prandial lipids, have shown reductions in VLDL and remnant lipoproteins by DPP4, these effects are thought to largely occur via GLP-1 mediated reduction in absorption of triglycerides and synthesis of Apo48 lipoproteins. There have been only limited studies (one double blind) conducted for >12 weeks[35–37]. The double blind study showed a 43% and 50% reduction in post-prandial triglycerides and chylomicrons respectively[35]. The remaining studies have all been short-term, with the effects of DPP4i and GLP-1Ra having been noted to occur even with a single dose independent of weight loss[38–40].

DPP4 inhibition on atherosclerosis

There have been multiple studies demonstrating the efficacy of DPP4i in reducing atherosclerosis in animals including rodents and rabbits[41*,42]. In a long-term study involving DPP4 inhibition with Alogliptin, reduced atherosclerotic plaque and vascular inflammation was noted in high-fat fed atherosclerosis prone Ldlr−/− mice. The reduction in plaque was associated with reduction in inflammation (monocyte/macrophage activation and chemotaxis)[42]. Reduced macrophage foam cell formation[43], smooth muscle proliferation[44], and macrophage polarization towards an M2 phenotype[45**], have been suggested as a mechanism for DPP4 inhibition-induced improvement of atherosclerosis. In a recent human study, alogliptin was shown to reduce carotid intima-media thickness in T2DM patients free of a history of apparent cardiovascular diseases[46**]. To what extent these findings help explain findings in clinical trials will only be determined by appropriate long term duration studies in humans, longer than the current 2–4 year trial horizon of cardiovascular safety trials noted below.

Results from Large Scale Clinical Trials of DPP4 Inhibitors

CV outcome trials with DPP4 inhibitors

There have been three large randomized double-blinded placebo controlled clinical trials evaluating hard cardiovascular end-points with DPP4i (Table 2). The primary motivation for these trials has been safety of DPP4i based on a prior FDA directive to provide safety data prior to and in certain instances following regulatory approval. All three of the completed trials, met the primary objective to exclude an unacceptable level of ischemic cardiovascular risk as defined in the FDA guidance. In 2 of these trials (SAVOR-TIMI 53 and EXAMINE) the efficacy end-point was the composite of CV death, non-fatal myocardial infarction and non-fatal stroke while the efficacy end-point in the other (TECOS) also included hospitalization for unstable angina. SAVOR-TIMI 53 tested Saxagliptin (5 mg qd, 2.5 mg if GFR≤ 50 ml/min) versus placebo (n=16,492) in patients with established CV disease (79% of patients) or major risk factors, over approximately 25 months[47]. The study was designed as a superiority trial, with a pre-specified non-inferiority comparison. Saxagliptin was not superior to placebo (HR, 1.00; 95% confidence interval, 0.89–1.12; P = 0.99) but met the non-inferiority criterion. EXAMINE was a randomized, double blind placebo-controlled non-inferiority study of alogliptin (25 mg qd or 6.25–12.5 if GFR <60 ml/min) versus placebo in diabetics with acute coronary syndrome[48]. The major composite end-point was similar in alogliptin and placebo (HR, 0.96; upper boundary of the one-sided repeated confidence interval, 1.16; P<0.001 for non-inferiority)[48]. TECOS assessed the effect of sitagliptin (100 mg, or 50 mg if GFR 30–50 ml/min, once daily) in diabetics with a history of CV disease[49]. The primary end-point was identical in the two groups with the trial meeting the criterion for non-inferiority (9.6% vs. 9.6%; HR, 0.98; 95% confidence interval, 0.88–1.09; P <0.0001 for noninferiority) [49**]. While an important consideration for anti-diabetic agents is their cardiovascular benefit, CV benefit has not been seen within the duration (2–4 years) of currently designed studies. It is however possible that more delayed benefits may still occur with DPP4i. Besides cardiovascular benefits, cost, treatment burden and adverse effects of therapies in diabetes are overarching considerations. Treatment burden and adverse effects can have an appreciable negative impact on patient quality of life with prior studies showing that interventions with a high treatment burden for treating glucose (“glycemic disutility”) may substantially attenuate benefit as measured by quality adjusted life years. Health economic analyses have suggested that while DPP4i may incur a significant cost upfront, their improved side-effect profile compared to conventional therapies in diabetes may be substantial. For instance, relative to glyburide as second-line therapy, the use of incretin agents is associated with an additional 0.09–0.12 quality-adjusted life years per patient, a result comparable to benefits accrued by a number of highly-effective preventive and treatment strategies[50].

Table 2.

CV outcome trials of DPP4i therapies

| Study | Agent | Manufacturer | Type of Trials |

Background Therapy | Intervention Arms & Dosage | Outcome Parameters/ Expected Completion Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Completed Trials | ||||||

| SAVOR-TIMI 53 | Saxagliptin | BMS & Astra Zeneca |

superiority trial |

MET, Insulin, SU alone or in combination |

Saxagliptin 5mg or 2.5 mg Placebo |

Hazard Ratio [95% CI] (pvalue) 1.00 [0.89 – 1.12] (p= 0.99) |

| EXAMINE | Alogliptin | Tarkeda | noninferiority trial |

MET, SU, Insulin or TZD alone or in combination |

Alogliptin 25/12.5/6.25 mg Placebo |

Hazard Ratio [95% CI] (pvalue) 0.96 [1.16*] (0.32) |

| TECOS | Sitagliptin | Merck | noninferiority trial |

MET, SU, Insulin or TZD alone or in combination |

Sitagliptin 100 mg or 50 mg Placebo |

Hazard Ratio [95% CI] (pvalue) 0.98 [0.88–1.09] (p<0.0001) |

| Ongoing Trials | ||||||

| CAROLINA (NCT01243424) |

Linagliptin | Boehringer Ingelheim |

noninferiority trial |

treatment naïve or mono-/dual therapy with metformin and/or an alpha- glucosidase inhibitor |

Linagliptin 5 mg or glimepiride placebo glimepiride 1–4 mg or linagliptin placebo |

September 2018 |

| CARMELINA (NCT01897532) |

Linagliptin | Boehringer Ingelheim |

noninferiority trial |

any antidiabetic background medication, excluding treatment with GLP-1 receptor agonists, DPP4 inhibitors or SGLT-2 inhibitors |

Linagliptin 5 mg Placebo 5 mg |

January 2018 |

MET, metformin; SU, sulfonylurea; TZD, thiazolidinediones

DPP4i and heart failure

An unexpected finding in SAVOR-TIMI 53 was an increased incidence of heart failure (HF) hospitalization (a pre-specified end-point) in saxagliptin compared with placebo (3.5 vs. 2.8%; HR, 1.27; 95% confidence interval, 1.07–1.51), without excess heart failure related mortality. Previous HF, eGFR<60 ml/m, elevated BNP and albumin/creatinine ratio were the strongest predictors of heart failure hospitalization. This excess heart failure risk was not noted with alogliptin or lixisenatide, both of which were in a high-risk ACS patient population assuaging concerns. In EXAMINE, first occurrence of hospitalization for HF occurred in 3.1 and 2.9% of alogliptin and placebo groups respectively (1.07; 95% confidence interval 0.79–1.46, p=0.68). There was no excess of cardiovascular death. In TECOS, the hospitalization rate for HF was identical in sitagliptin and placebo (3.1 vs. 3.1%; HR, 1.00, 0.83–1.20; P=0.98) [49**].

Conclusion

The development of specific DPP4i has highlighted the pathophysiologic importance of DPP4 in atherosclerosis and cardiac remodeling associated with diabetes and diabetic heart failure. Although catalytic inhibition of DPP4 with DPP4i clearly alters pathways that could favor cardioprotection, many questions remain regarding the role of DPP4 in pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. The GLP-1R-independent aspects of DPP4 function may help reconcile differences in results noted between pharmacologic inhibition of DPP4 and DPP4 deficiency (in knock out models). Mulvihill et al. recently reported that treatment of DPP4 inhibitor MK-0626 results in modest cardiac hypertrophy and impaired cardiac function in diabetic mice, while both GLP-1R agonist and DPP4 deficiency improve cardiac function [26]. These results suggest either GLP-1-independent actions of DPP4 inhibition or drug-related unspecific effect may contribute to cardiac dysfunction. In humans short term and long term use of DPP4i are safe from a cardiovascular perspective. The lack of efficacy from a CV perspective has been raised as an important deficiency of these agents but must be contextualized by the fact that the durations of large outcome trials with DPP4i have all been shorter than 5 years.

KEY POINTS.

DPP4 inhibitors are safe from a cardiovascular standpoint.

DPP4 inhibitors do not improve cardiovascular outcomes in patients with T2DM in a duration of less than 5 years.

Multiple studies suggest catalytic inhibition of DPP4 alters pathways that could favor cardioprotection.

Saxagliptin increased hospitalization rate of heart failure compared to placebo, while other DPP4 inhibitors including alogliptin and sitagliptin do not affect heart failure hospitalization rate.

GLP-1R-independent aspects of DPP4 function may contribute to the overall neutral effects on cardiovascular outcome seen in the outcome trials.

Acknowledgments

Financial support and sponsorship:

This work was supported by grants from NIH (K01 DK105108), AHA (15SDG25700381), Boehringer Ingelheim (IIS2015-10485), and Mid-Atlantic Nutrition Obesity Research Center (NORC) under NIH award number P30DK072488.

JZ is currently receiving a grant (IIS2015-10485) from Boehringer Ingelheim.

Acknowledgements: None

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Zheng TP, Yang F, Gao Y, Baskota A, Chen T, Tian HM, Ran XW. Increased plasma DPP4 activities predict new-onset atherosclerosis in association with its proinflammatory effects in Chinese over a four year period: A prospective study. Atherosclerosis. 2014;235:619–624. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.05.956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhong J, Rao X, Deiuliis J, Braunstein Z, Narula V, Hazey J, Mikami D, Needleman B, Satoskar AR, Rajagopalan S. A potential role for dendritic cell/macrophage-expressing DPP4 in obesity-induced visceral inflammation. Diabetes. 2013;62:149–157. doi: 10.2337/db12-0230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Z, Grigo C, Steinbeck J, Von Hörsten S, Amann K, Daniel C. Soluble DPP4 originates in part from bone marrow cells and not from the kidney. Peptides. 2014;57:109–117. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauvois B, Djavaheri-Mergny M, Rouillard D, Dumont J, Wietzerbin J. Regulation of CD26/DPPIV gene expression by interferons and retinoic acid in tumor B cells. Oncogene. 2000;19:265–272. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salgado FJ, Vela E, Martin M, Franco R, Nogueira M, Cordero OJ. Mechanisms of CD26/dipeptidyl peptidase IV cytokine-dependent regulation on human activated lymphocytes. Cytokine. 2000;12:1136–1141. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1999.0643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nemoto E, Sugawara S, Takada H, Shoji S, Horiuch H. Increase of CD26/dipeptidyl peptidase IV expression on human gingival fibroblasts upon stimulation with cytokines and bacterial components. Infect Immun. 1999;67:6225–6233. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.12.6225-6233.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arwert EN, Mentink RA, Driskell RR, Hoste E, Goldie SJ, Quist S, Watt FM. Upregulation of CD26 expression in epithelial cells and stromal cells during wound-induced skin tumour formation. Oncogene. 2011;31:992–1000. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conarello SL, Li Z, Ronan J, Roy RS, Zhu L, Jiang G, Liu F, Woods J, Zycband E, Moller DE, et al. Mice lacking dipeptidyl peptidase IV are protected against obesity and insulin resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6825–6830. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0631828100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marguet D, Baggio L, Kobayashi T, Bernard AM, Pierres M, Nielsen PF, Ribel U, Watanabe T, Drucker DJ, Wagtmann N. Enhanced insulin secretion and improved glucose tolerance in mice lacking CD26. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:6874–6879. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120069197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhong J, Maiseyeu A, Davis SN, Rajagopalan S. DPP4 in Cardiometabolic Disease: Recent Insights From the Laboratory and Clinical Trials of DPP4 Inhibition. Circ. Res. 2015;116:1491–1504. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.305665. A review summarizing the cardiovascular effect of DPP4 inhibition.

- 11.De Falco E, Porcelli D, Torella AR, Straino S, Iachininoto MG, Orlandi A, Truffa S, Biglioli P, Napolitano M, Capogrossi MC, et al. SDF-1 involvement in endothelial phenotype and ischemia-induced recruitment of bone marrow progenitor cells. Blood. 2004;104:3472–3482. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Youn SW, Lee SW, Lee J, Jeong HK, Suh JW, Yoon CH, Kang HJ, Kim HZ, Koh GY, Oh BH, et al. COMP-Ang1 stimulates HIF-1α-mediated SDF-1 overexpression and recovers ischemic injury through BM-derived progenitor cell recruitment. Blood. 2011;117:4376–4386. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-295964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Segal MS, Shah R, Afzal A, Perrault CM, Chang K, Schuler A, Beem E, Shaw LC, Calzi SL, Harrison JK, et al. Nitric oxide cytoskeletal-induced alterations reverse the endothelial progenitor cell migratory defect associated with diabetes. Diabetes. 2006;55:102–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanki S, Segers VFM, Wu W, Kakkar R, Gannon J, Sys SU, Sandrasagra A, Lee RT. Stromal cell-derived factor-1 retention and cardioprotection for ischemic myocardium. Circ. Heart Fail. 2011;4:509–518. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.110.960302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shih C-M, Chen Y-H, Yi W-L, Tsao N-W, Wu S-C, Kao Y-T, Chiang K-H, Li C-Y, Chang N-C, Lin C-Y, et al. MK-0626, A Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Inhibitor, Improves Neovascularization by Increasing Both the Number of Circulating Endothelial Progenitor Cells and Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthetase Expression. Curr. Med. Chem. 2014;21:2012–2022. doi: 10.2174/09298673113206660273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhong J, Rajagopalan S. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 regulation of SDF-1/CXCR4 axis: Implications for cardiovascular disease. Front. Immunol. 2015;6 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00477. A review discussing the implication of SDF-1-dependent effect of DPP4 inhibition in cardiovascular disease.

- 17.Mannucci E, Pala L, Ciani S, Bardini G, Pezzatini A, Sposato I, Cremasco F, Ognibene A, Rotella CM. Hyperglycaemia increases dipeptidyl peptidase IV activity in diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 2005;48:1168–1172. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1749-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohnuma K, Inoue H, Uchiyama M, Yamochi T, Hosono O, Dang NH, Morimoto C. T-cell activation via CD26 and caveolin-1 in rheumatoid synovium [Internet] Mod Rheumatol. 2006;16:3–13. doi: 10.1007/s10165-005-0452-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wronkowitz N, Görgens SW, Romacho T, Villalobos LA, Sánchez-Ferrer CF, Peiró C, Sell H, Eckel J. Soluble DPP4 induces inflammation and proliferation of human smooth muscle cells via protease-activated receptor 2. BBA - Mol. Basis Dis. 2014;1842:1613–1621. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ryskjaer J, Deacon CF, Carr RD, Krarup T, Madsbad S, Holst J, Vilsboll T. Plasma dipeptidyl peptidase-IV activity in patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus correlates positively with HbAlc levels, but is not acutely affected by food intake [Internet] Eur J Endocrinol. 2006;155:485–493. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Waldrop G, Zhong J, Peters M, Rajagopalan S. Incretin-Based Therapy for Diabetes: What a Cardiologist Needs to Know. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016;67:1488–1496. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.12.058. A review summarizes the recent advances in incretin-based treatment from a clinical standpoint.

- 22.Gomez N, Matheeussen V, Damoiseaux C, Tamborini A, Merveille AC, Jespers P, Michaux C, Clercx C, De Meester I, McEntee K. Effect of Heart Failure on Dipeptidyl Peptidase IV Activity in Plasma of Dogs. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2012;26:929–934. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2012.00942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sauvé M, Ban K, Abdul Momen M, Zhou YQ, Henkelman RM, Husain M, Drucker DJ. Genetic deletion or pharmacological inhibition of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 improves cardiovascular outcomes after myocardial infarction in mice. Diabetes. 2010;59:1063–1073. doi: 10.2337/db09-0955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shigeta T, Aoyama M, Bando YK, Monji A, Mitsui T, Takatsu M, Cheng XW, Okumura T, Hirashiki A, Nagata K, et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 modulates left ventricular dysfunction in chronic heart failure via angiogenesis-dependent and -independent actions. Circulation. 2012;126:1838–1851. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.096479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mulvihill EE, Drucker DJ. Pharmacology, physiology, and mechanisms of action of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors. Endocr. Rev. 2014;35:992–1019. doi: 10.1210/er.2014-1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mulvihill EE, Varin EM, Ussher JR, Campbell JE, Bang KWA, Abdullah T, Baggio LL, Drucker DJ. Inhibition of Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 impairs ventricular function and promotes cardiac fibrosis in high fat-fed diabetic mice. Diabetes. 2016;65:742–754. doi: 10.2337/db15-1224. A study shows DPP4 enzymatic inhibitor may have opposite effects on cardiac function compared with GLP-1R agonist and DPP4 deficiency.

- 27. Aoyama M, Kawase H, Bando YK, Monji A, Murohara T. Dipeptidyl Peptidase 4 Inhibition Alleviates Shortage of Circulating Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 in Heart Failure and Mitigates Myocardial Remodeling and Apoptosis via the Exchange Protein Directly Activated by Cyclic AMP 1/Ras-Related Protein 1 Axis. Circ. Hear. Fail. 2016;9:e002081. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.115.002081. The investigators show DPP4 inhibition restores cardiac remodeling and apoptosis resulted from declined GLP-1 and pressure overload.

- 28.McCormick LM, Kydd AC, Read PA, Ring LS, Bond SJ, Hoole SP, Dutka DP. Chronic dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibition with sitagliptin is associated with sustained protection against ischemic left ventricular dysfunction in a pilot study of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and coronary artery disease. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2014;7:274–281. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.113.000785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Read PA, Khan FZ, Heck PM, Hoole SP, Dutka DP. DPP-4 inhibition by sitagliptin improves the myocardial response to dobutamine stress and mitigates stunning in a pilot study of patients with coronary artery disease. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3:195–201. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.109.899377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Poppel PCM, Netea MG, Smits P, Tack CJ. Vildagliptin improves endothelium-dependent vasodilatation in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:2072–2077. doi: 10.2337/dc10-2421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakamura K, Oe H, Kihara H, Shimada K, Fukuda S, Watanabe K, Takagi T, Yunoki K, Miyoshi T, Hirata K, et al. DPP-4 inhibitor and alpha-glucosidase inhibitor equally improve endothelial function in patients with type 2 diabetes: EDGE study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2014;13:110. doi: 10.1186/s12933-014-0110-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ayaori M, Iwakami N, Uto-Kondo H, Sato H, Sasaki M, Komatsu T, Iizuka M, Takiguchi S, Yakushiji E, Nakaya K, et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors attenuate endothelial function as evaluated by flow-mediated vasodilatation in type 2 diabetic patients. J. Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e003277. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.112.003277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Devin JK, Pretorius M, Nian H, Yu C, Billings FT, Brown NJ. Dipeptidyl-peptidase 4 inhibition and the vascular effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 and brain natriuretic peptide in the human forearm. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e001075. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goud A, Zhong J, Peters M, Brook RD, Rajagopalan S. GLP-1 Agonists and Blood Pressure: A Review of the Evidence. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2016;18:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s11906-015-0621-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eliasson B, Moller-Goede D, Eeg-Olofsson K, Wilson C, Cederholm J, Fleck P, Diamant M, Taskinen M-RR, Smith U, Möller-Goede D. Lowering of postprandial lipids in individuals with type 2 diabetes treated with alogliptin and/or pioglitazone: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled study. Diabetologia. 2012;55:915–925. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2447-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bunck MC, Corner A, Eliasson B, Heine RJ, Shaginian RM, Wu Y, Yan P, Smith U, Yki-Jarvinen H, Diamant M, et al. One-year treatment with exenatide vs. Insulin Glargine: Effects on postprandial glycemia, lipid profiles, and oxidative stress. Atherosclerosis. 2010;212:223–229. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matikainen N, Mänttäri S, Schweizer A, Ulvestad A, Mills D, Dunning BE, Foley JE, Taskinen M-R. Vildagliptin therapy reduces postprandial intestinal triglyceride-rich lipoprotein particles in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2006;49:2049–2057. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0340-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xiao C, Bandsma RHJ, Dash S, Szeto L, Lewis GF. Exenatide, a glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist, acutely inhibits intestinal lipoprotein production in healthy humans. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2012;32:1513–1519. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.246207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xiao C, Dash S, Morgantini C, Patterson BW, Lewis GF. Sitagliptin, a DPP-4 inhibitor, acutely inhibits intestinal lipoprotein particle secretion in healthy humans. Diabetes. 2014;63:2394–2401. doi: 10.2337/db13-1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schwartz EA, Koska J, Mullin MP, Syoufi I, Schwenke DC, Reaven PD. Exenatide suppresses postprandial elevations in lipids and lipoproteins in individuals with impaired glucose tolerance and recent onset type 2 diabetes mellitus. Atherosclerosis. 2010;212:217–222. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hirano T, Yamashita S, Takahashi M, Hashimoto H, Mori Y, Goto M. Anagliptin, a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor, decreases macrophage infiltration and suppresses atherosclerosis in aortic and coronary arteries in cholesterol-fed rabbits. Metabolism. 2016;65:893–903. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2016.03.010. This investigation reported that DPP-4 inhibition by anagliptin suppresses plaque formation and reduces macrophage infiltration in coronary arteries with a marked reduction in macrophage accumulation in a high cholesterol diet-fed rabbit model.

- 42.Shah Z, Kampfrath T, Deiuliis JA, Zhong J, Pineda C, Ying Z, Xu X, Lu B, Moffatt-Bruce S, Durairaj R, et al. Long-term dipeptidyl-peptidase 4 inhibition reduces atherosclerosis and inflammation via effects on monocyte recruitment and chemotaxis. Circulation. 2011;124:2338–2349. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.041418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Terasaki M, Nagashima M, Watanabe T, Nohtomi K, Mori Y, Miyazaki A, Hirano T. Effects of PKF275-055, a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor, on the development of atherosclerotic lesions in apolipoprotein E-null mice. Metabolism. 2012;61:974–977. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2011.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ervinna N, Mita T, Yasunari E, Azuma K, Tanaka R, Fujimura S, Sukmawati D, Nomiyama T, Kanazawa A, Kawamori R, et al. Anagliptin, a DPP-4 inhibitor, suppresses proliferation of vascular smooth muscles and monocyte inflammatory reaction and attenuates atherosclerosis in male apo e-deficient mice. Endocrinology. 2013;154:1260–1270. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Brenner C, Franz WM, Kühlenthal S, Kuschnerus K, Remm F, Gross L, Theiss HD, Landmesser U, Krankel N. DPP-4 inhibition ameliorates atherosclerosis by priming monocytes into M2 macrophages. Int. J. Cardiol. 2015;199:163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.07.044. A study reporting SDF-1 mediates the sitagliptin-induced M2 polarization and modulation of early atherosclerosis.

- 46. Mita T, Katakami N, Yoshii H, Onuma T, Kaneto H, Osonoi T, Shiraiwa T, Kosugi K, Umayahara Y, Yamamoto T, et al. Alogliptin, a Dipeptidyl Peptidase 4 Inhibitor, Prevents the Progression of Carotid Atherosclerosis in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: The Study of Preventive Effects of Alogliptin on Diabetic Atherosclerosis (SPEAD-A) Diabetes Care. 2016;39:139–148. doi: 10.2337/dc15-0781. This open-labeled randomized comparative study reported that DPP4 inhibitor alogliptin treatment reduced the progression of carotid intima-media thickness in patients with T2DM free of apparent cardiovascular disease.

- 47.Scirica BM, Bhatt DL, Braunwald E, Steg PG, Davidson J, Hirshberg B, Ohman P, Frederich R, Wiviott SD, Hoffman EB, et al. Saxagliptin and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369:1317–1326. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1307684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.White WBB, Cannon CPP, Heller SRR, Nissen SEE, Bergenstal RMM, Bakris GLL, Perez ATT, Fleck PRR, Mehta CRR, Kupfer S, et al. Alogliptin after acute coronary syndrome in patients with type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369:1327–1335. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Green JB, Bethel MA, Armstrong PW, Buse JB, Engel SS, Garg J, Josse R, Kaufman KD, Koglin J, Korn S, et al. Effect of Sitagliptin on Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501352. A large scale clinical trial assessing the cardiovascular effect of sitagliptin in patients with T2DM. The results indicate sitagliptin neither harm nor protect cardiovascular outcomes in patients with T2DM.

- 50.Sinha A, Rajan M, Hoerger T, Pogach L, Sinha a, Rajan M, Hoerger T, Pogach L. Costs and Consequences Associated With Newer Medications for Glycemic Control in Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:695–700. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]