Abstract

To investigate the effects of posaconazole (POS) and amphotericin B (AMB) combination therapy in cryptococcal infection, we established an experimental model of systemic cryptococcosis in CD1 mice by intravenous injection of three distinct clinical isolates of Cryptococcus neoformans. Therapy was started 24 h after the infection and continued for 10 consecutive days. POS was given at 3 and 10 mg/kg of body weight/day, while AMB was given at 0.3 mg/kg/day. Combination therapy consisted of POS given at a low (combo 3) or at a high (combo 10) dose plus AMB. Survival studies showed that combo 3 was significantly more effective than POS at 3 mg/kg for two isolates tested (P value, ≤0.001), while combo 10 was significantly more effective than POS at 10 mg/kg for all three isolates (P values ranging from <0.001 to 0.005). However, neither combination regimen was more effective than AMB alone. For two isolates, combination therapy was significantly more effective than each single drug at reducing the fungal burden in the brain (P values ranging from 0.001 to 0.015) but not in the lungs. This study demonstrates that the major impact of POS and AMB combination therapy is on brain fungal burden rather than on survival.

Cryptococcus neoformans is the cause of the most common life-threatening opportunistic fungal infection in patients with AIDS (13). Although the occurrence of cryptococcosis among this group of patients has decreased in recent years due to the introduction of triple human immunodeficiency virus therapy, its incidence remains high, particularly in developing countries (6). The treatment of choice for cryptococcosis remains amphotericin B (AMB), with or without flucytosine. For suppression therapy, a triazole, such as fluconazole, is the agent of choice (20). The toxicity of AMB combined with flucytosine and the increasing isolation of fluconazole-resistant strains of C. neoformans underline the need for improved treatments and the use of combination strategies to overcome the emergence of resistance (1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 16). The combination of a polyene and an azole has always been questioned because of a potential for antagonism (10). However, recent experimental and clinical data have demonstrated that the effects of an azole antifungal agent on the efficacy of AMB are either drug or fungus specific (3, 12, 15, 17-19, 21-23). Little is known about the interactions between azoles and AMB against C. neoformans (3, 9, 12, 17, 18). Thus, in this study, we evaluated a combination of AMB and the new triazole posaconazole (POS) in a murine model of systemic cryptococcosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolates.

Three clinical isolates of C. neoformans obtained from AIDS patients were used in this study (Table 1). They had been previously tested in vitro for MIC determinations (3), and they were selected based on checkerboard test results (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of C. neoformans isolates used in this study

| Isolate | Serotypea | Source of isolation | MIC (μg/ml) of:

|

FIC indexb | Definition according to reference 10 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMB | POS | AMB-POS | |||||

| 486 | AD | Cerobrospinal fluid | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.125/0.06 | 0.31 | Synergy |

| 491 | D | Blood | 0.5 | 0.125 | 0.25/0.015 | 0.62 | Indifference |

| 2337 | D | Blood | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.03/0.25 | 1.06 | Indifference |

Serotyping was performed by a standard agglutination assay.

Fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) index; the FIC index is the sum of the FICs of each drug; the FIC is defined as the MIC of each drug when used in combination divided by the MIC of the drug when used alone.

Antifungal agents.

A stock solution of POS (Schering Plough Research Institute, Kenilworth, N.J.) was prepared with polyethylene glycol 200 (Janssen Chimica, Geel, Belgium). AMB was purchased as Fungizone from Bristol-Myers Squibb S.p.A. (Latina, Italy) and prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Animal studies.

A murine model of systemic cryptococcosis was established with CD1 male mice (weight, 25 g; Charles River Laboratories, Calco, Italy) by injection into the lateral tail vein of viable yeast cells grown overnight in brain heart infusion broth. Animal experiments were conducted with the approval of the University of Ancona ethics committee. AMB was given intraperitoneally at 0.3 mg/kg of body weight/day, while POS was administered by oral gavage at concentrations of 3 and 10 mg/kg/day. Two combination therapies were also used: AMB plus POS at 3 mg/kg/day (combo 3) and AMB plus POS at 10 mg/kg/day (combo 10). Drugs were administered 2 h apart. Therapy was started 24 h after infection and continued for 10 consecutive days.

For survival studies, the mice were observed through days 40 or 80, and deaths were recorded daily. Moribund mice were sacrificed, and their deaths were recorded as occurring on the next day. For tissue burden studies, the mice were sacrificed on days 1, 7, 14, and 21 after the end of therapy, and the number of CFU per gram of brain and lungs was determined by quantitative plating of organ homogenates on Sabouraud dextrose agar plates. There were 10 to 13 mice per group in survival studies and 7 mice per group in tissue burden studies.

Statistical analysis.

The log rank test was used to determine the difference between survival groups (statistical significance for multiple comparisons was set at a P value of ≤0.0125), while the Mann-Whitney U test was used to determine significance in tissue burden studies (statistical significance for multiple comparisons was set at a P value of ≤0.0160).

RESULTS

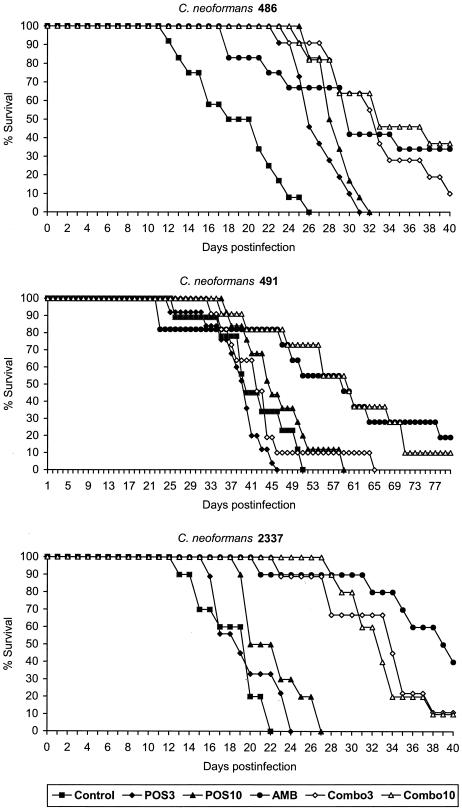

To investigate the effects of AMB combined with POS against C. neoformans, we performed in vivo experiments with three clinical isolates for which the in vitro interactions between these drugs were previously determined (3). According to the consensus terminology (10) for describing results of combination testing, synergy was observed for C. neoformans 486, while indifference (or Loewe additivity) characterized drug interactions against C. neoformans 491 and 2337. Survival results are shown in Fig. 1. Mice were infected with 1.7 × 105, 2.0 × 105, and 2.1 × 105 CFU/mouse in experiments with C. neoformans 486, 491, and 2337, respectively. For C. neoformans 486, all treatment regimens were effective in prolonging survival relative to the controls (P < 0.001). Both combo 3 and combo 10 were more effective than the respective monotherapies with POS (P = 0.001 and 0.005, respectively) but were not more effective than AMB alone. For C. neoformans 491, only AMB (P = 0.008) and combo 10 (P < 0.001) were effective in prolonging survival relative to the controls. No difference was observed between these two regimens. Of note, combo 3 abolished the efficacy of the polyene. For C. neoformans 2337, all treatment regimens, with the exception of POS at 3 mg/kg, were effective relative to the controls (P values ranging from <0.001 to 0.012). For this strain, both combo 3 and combo 10 were more effective than the respective monotherapies with POS (P < 0.001). Although the survival of mice treated with both combination therapies was not significantly different from that of mice treated with the polyene (for AMB versus combo 3, the P value was 0.070; for AMB versus combo 10, the P value was 0.039), there was a trend toward reduced activity of AMB in the combination therapies.

FIG. 1.

Survival of mice infected intravenously with cells of C. neoformans 486, 491, or 2337 and treated for 10 consecutive days with POS at 3 mg/kg, POS at 10 mg/kg, AMB at 3 mg/kg/day, combo 3, or combo 10.

The second set of experiments consisted of tissue burden studies. In these experiments, a total of four groups were considered: control, AMB at 0.3 mg/kg/day, POS at 10 mg/kg/day, and combination. Mice were infected with 1.7 × 105, 2.5 × 105, and 2.6 × 105 CFU/mouse in experiments with C. neoformans 486, 491, and 2337, respectively. The animals were treated for 10 days and sacrified 24 h after the end of therapy (early tissue burden). The results are shown in Table 2. For C. neoformans 486, all regimens were significantly superior to controls at reducing brain fungal burdens (P values ranging from 0.001 to 0.002), whereas only the triazole and the combination were similarly effective at reducing lung fungal burdens (P = 0.001). In the lungs, combination therapy and POS were also more effective than AMB alone (P = 0.002). For C. neoformans 491, all regimens, with the exception of AMB in the lungs, were effective at reducing fungal burdens relative to controls in both organs (P values ranging from 0.0006 to 0.009). Also, combination and POS treatments were more active than AMB in both organs (P values ranging from 0.001 to 0.009). Moreover, combination therapy was significantly more effective than each single drug at reducing fungal counts in the brain (P ≤ 0.002). For C. neoformans 2337, all drug regimens were significantly superior to controls in both organs (P values ranging from 0.001 to 0.002); the triazole was more effective than the polyene in brain tissue (P = 0.0002). Again, the combination therapy was more effective than both monotherapies at reducing brain fungal burdens (P = 0.015).

TABLE 2.

Effects of combination therapy on early tissue burden in mice infected with isolates of C. neoformansa

| Isolate | Therapy | Fungal burden (log10 CFU/g) in:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lungs

|

Brain

|

||||

| Mean | Range | Mean | Range | ||

| 486 | None | 7.9 | 6.4-8.4 | 8.9 | 8.3-9.2 |

| AMB | 6.9 | 5.2-7.3 | 7.9b | 7.0-8.1 | |

| POS | 5.0bc | 4.8-5.3 | 7.5b | 6.8-8.1 | |

| Combination | 4.8bc | 3.9-5.2 | 7.4b | 5.6-8.1 | |

| 491 | None | 6.7 | 5.1-7.1 | 7.3 | 7.1-7.6 |

| AMB | 5.9 | 5.4-6.3 | 6.7b | 6.3-6.9 | |

| POS | 3.7bc | 2.8-4.1 | 6.0bc | 5.7-6.2 | |

| Combination | 4.2bc | 2.1-5.0 | 5.2bcd | 4.1-5.6 | |

| 2337 | None | 8.9 | 8.2-9.5 | 8.4 | 7.9-8.7 |

| AMB | 5.4b | 4.0-6.1 | 7.2b | 6.3-7.4 | |

| POS | 4.6b | 3.4-5.1 | 6.0bc | 5.2-6.5 | |

| Combination | 3.7bc | 3.3-4.1 | 5.2bcd | 4.1-5.6 | |

See the text for details. There were seven mice in each treatment group.

For any treatment versus the control, the P value was ≤0.016.

For any treatment versus AMB, the P value was ≤ 0.016.

For any treatment versus POS, the P value was ≤0.016.

To investigate the effects of combination therapy along with the progression of infection, we performed additional tissue burden studies with C. neoformans 2337. The mice were infected with 2.5 × 103 CFU/mouse, treated for 10 days, and sacrificed on days 7, 14, and 21 after the end of therapy (late tissue burden). The results are shown in Table 3. The results on day 7 were similar to those on day 1 after the end of therapy. All regimens, with the exception of AMB in the brain (P = 0.019), were effective relative to controls at reducing the fungal counts in both organs (P values ranging from 0.002 to 0.009). Again, the combination therapy was significantly more active than each single therapy in the brain (P ≤ 0.009).

TABLE 3.

Effects of combination therapy on late tissue burden in mice infected with C. neoformans 2337a

| Days after the end of therapy | Therapy | Fungal burden (log10 CFU/g) in:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lungs

|

Brain

|

||||

| Mean | Range | Mean | Range | ||

| 7 | None | 5.3 | 3.4-5.9 | 6.4 | 5.9-6.7 |

| AMB | 3.0b | 2.0-3.4 | 5.8 | 5.3-6.0 | |

| POS | 2.9b | 1.4-3.5 | 5.1b | 3.8-5.5 | |

| Combination | 1.7b | 0.7-2.3 | 3.4bcd | 2.1-3.8 | |

| 14 | None | 5.0 | 3.9-5.2 | 7.3 | 4.9-6.9 |

| AMB | 4.6 | 3.7-4.8 | 6.7 | 5.6-7.0 | |

| POS | 4.5 | 3.9-5.0 | 6.4 | 4.3-6.6 | |

| Combination | 4.3 | 3.4-4.8 | 6.1 | 3.4-6.5 | |

See the text for details. There were seven mice in each treatment group.

For any treatment versus the control, the P value was ≤0.016.

For any treatment versus AMB, the P value was ≤0.016.

For any treatment versus POS, the P value was ≤0.016.

On day 14 after the end of therapy, none of the treatments was effective in both organs. Actually, the number of CFU per gram in the treatment groups reached those in the controls (Table 3). Similarly, no significant difference was detected in both organs on day 21 after the end of therapy (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we evaluated the effects of combination therapy with POS and AMB against C. neoformans in a murine model of systemic cryptococcosis. The effects of this combination therapy were previously investigated in vitro against a large number of clinical isolates of C. neoformans. In that study, the combination regimen yielded 33 and 67% synergistic and indifferent (Loewe additivity) interactions, respectively (3). Therefore, three clinical isolates of C. neoformans for which either synergistic or indifferent interactions were observed in vitro were selected for the present study.

Several observations can be made from this study. First, neither survival nor tissue burden data correlated with the previous results observed in vitro. This finding may be due to the fact that the checkerboard methodology measures drug effects at static concentrations only, while in vivo concentrations vary upon drug absorption and elimination rates and thereby influence the overall efficacy of the combination (11, 14).

Second, survival studies showed that combination therapy was generally more effective than the triazole alone but not more effective than the polyene alone. Although in this study we used a low dose of AMB to try to avoid its rapid fungicidal activity, the polyene given at 0.3 mg/kg/day was still effective at prolonging survival with all three isolates. It is important to note that the dose of the triazole can affect the efficacy of AMB. In fact, we found that POS given at 3 mg/kg/day abolished the efficacy of AMB in mice infected with C. neoformans 491. Since this phenomenon was observed only for one isolate, we speculate that these variable effects are more likely to be correlated with the strain itself rather than with pharmacokinetic parameters. Due to the considerable degree of variation among isolates of C. neoformans with respect to genetic background, the effects of such combination therapies may vary among the isolates. We hypothesize that a low dose of the triazole may cause subtle changes in sterol membrane composition for a given strain (e.g., changes in methylated sterol/demethylated sterol ratios) and thereby may reduce the efficacy of AMB. On the contrary, a high dose of the triazole may not allow the fungus to modify its membrane composition and thereby may conserve targets for AMB.

Third, our tissue burden data showed a reciprocal potentiation of the polyene and the azole drug in brain tissues. This finding was observed in mice infected with two isolates of C. neoformans (491 and 2337). Since the central nervous system is the target organ for cryptococcosis, this finding is of particular interest. This effect was mainly evident in the early phase of infection, as shown in studies conducted with C. neoformans 2337, in which the efficacy of therapy persisted until 7 days after the end of treatment. The residual burden analyzed on days 14 and 21 after the end of therapy showed a lack of effect of any of the regimens, including combination therapy. This finding can be easily explained by considering the possibility of complete drug clearance from the infected organs at these times. Overall, our data correlate with those reported by other investigators (9, 17). Early studies with a ketoconazole-AMB combination showed that the major impact of dual therapy was on fungal tissue burden rather than on survival (17). Similarly, Barchiesi et al. recently observed that a fluconazole-AMB combination was more effective than fluconazole alone but not more effective than AMB alone in prolonging survival, while a reciprocal potentiation was often detected for fungal burden (3).

In conclusion, a combination of the new triazole POS with AMB did not show significant antagonism in an experimental murine model of systemic cryptococcosis. Although this therapeutic approach does not seem to be more effective than AMB alone in terms of survival, it may have a theoretical advantage at the tissue level. It is clear that additional studies are warranted to further elucidate the potential benefits of this strategy before considering it suitable for clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a grant from Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Rome, Italy (IV AIDS project, grant no. 50D.29).

REFERENCES

- 1.Alves, S. H., J. O. Lopes, J. M. Costa, and C. Klock. 1997. Development of secondary resistance to fluconazole in Cryptococcus neoformans isolated from a patient with AIDS. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. São Paulo 39:359-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armengou, A., C. Porcar, J. Mascaro, and F. Garcia-Bragado. 1996. Possible development of resistance to fluconazole during suppressive therapy for AIDS-associated cryptococcal meningitis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 23:1337-1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barchiesi, F., A. M. Schimizzi, F. Caselli, A. Novelli, S. Fallani, D. Giannini, D. Arzeni, S. Di Cesare, L. F. Di Francesco, M. Fortuna, A. Giacometti, F. Carle, T. Mazzei, and G. Scalise. 2000. Interactions between triazoles and amphotericin B against Cryptococcus neoformans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2435-2441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barchiesi, F., A. M. Schimizzi, L. K. Najvar, R. Bocanegra, F. Caselli, S. Di Cesare, D. Giannini, L. F. Di Francesco, A. Giacometti, F. Carle, G. Scalise, and J. R. Graybill. 2001. Interactions of posaconazole and flucytosine against Cryptococcus neoformans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1355-1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bennett, J. E., W. E. Dismukes, R. J. Duma, G. Medoff, M. A. Sande, H. Gallis, J. L. Leonard, B. T. Fields, M. Bradshaw, H. Haywood, Z. A. McGee, T. R. Cate, C. G. Cobbs, J. F. Warner, and D. W. Alling. 1979. A comparison of amphotericin B alone and combined with flucytosine in the treatment of cryptococcal meningitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 301:126-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1997. Update: trends in AIDS incidence. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 46:165-173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Craven, P. C., and J. R. Graybill. 1984. Combination of oral flucytosine and ketoconazole as therapy for experimental cryptococcal meningitis. J. Infect. Dis. 149:584-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friese, G., T. Discher, R. Fussle, A. Schmalreck, and J. Lohmeyer. 2001. Development of azole resistance during fluconazole maintenance therapy for AIDS-associated cryptococcal disease. AIDS 15:2344-2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graybill, J. R., D. M. Williams, E. Van Cutsem, and D. J. Drutz. 1980. Combination therapy of experimental histoplasmosis and cryptococcosis with amphotericin B and ketoconazole. Rev. Infect. Dis. 2:551-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson, M. D., C. MacDougall, L. Ostrosky-Zeichner, J. R. Perfect, and J. H. Rex. 2004. Combination antifungal therapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:693-715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kontoyiannis, D. P., and R. E. Lewis. 2003. Combination chemotherapy for invasive fungal infections: what laboratory and clinical studies tell us so far. Drug Res. Updates 6:257-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larsen, R. A., M. Bauer, A. M. Thomas, and J. R. Graybill. 2004. Amphotericin B and fluconazole, a potent combination therapy for cryptococcal meningitis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:985-991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitchell, T. G., and J. R. Perfect. 1995. Cryptococcosis in the era of AIDS—100 years after the discovery of Cryptococcus neoformans. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 8:515-548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mouton, J. W., M. L. van Ogtrop, D. Andes, and W. A. Craig. 1999. Use of pharmacodynamic indices to predict efficacy of combination therapy in vivo. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:2473-2478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Najvar, L. K., A. Cacciapuoti, S. Hernandez, J. Halpern, R. Bocanegra, M. Gurnani, F. Menzel, D. Loebenberg, and J. R. Graybill. 2004. Activity of posaconazole combined with amphotericin B against Aspergillus flavus infection in mice: comparative studies in two laboratories. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:758-764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nguyen, M. H., L. K. Najvar, C. Y. Yu, and J. R. Graybill. 1997. Combination therapy with fluconazole and flucytosine in the murine model of cryptococcal meningitis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:1120-1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perfect, J. R., and D. T. Durak. 1982. Treatment of experimental cryptococcal meningitis with amphotericin B, 5-fluorocytosine and ketoconazole. J. Infect. Dis. 146:429-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Polak, A. 1987. Combination therapy of experimental candidiasis, cryptococcosis, aspergillosis and wangiellosis in mice. Chemotherapy (Basel) 33:381-395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rex, J. H., P. G. Pappas, A. W. Karchmer, J. Sobel, J. E. Edwards, S. Hadley, C. Brass, J. A. Vazquez, S. W. Chapman, H. W. Horowitz, M. Zervos, D. McKinsey, J. Lee, T. Babinchak, R. W. Bradsher, J. D. Cleary, D. M. Cohen, L. Danziger, M. Goldman, J. Goodman, E. Hilton, N. E. Hyslop, D. H. Kett, J. Lutz, R. H. Rubin, W. M. Scheld, M. Schuster, B. Simmons, D. K. Stein, R. G. Washburn, L. Mautner, T. C. Chu, H. Panzer, R. B. Rosenstein, J. Booth, et al. 2003. A randomized and blinded multicenter trial of high-dose fluconazole plus placebo versus fluconazole plus amphotericin B as therapy for candidemia and its consequences in nonneutropenic subjects. Clin. Infect. Dis. 36:1221-1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saag, M. S., R. J. Graybill, R. A. Larsen, P. G. Pappas, J. R. Perfect, W. G. Powderly, J. D. Sobel, W. E. Dismukes, et al. 2000. Practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease. Clin. Infect. Dis. 30:710-718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanati, H., C. F. Ramos, A. S. Bayer, and M. A. Ghannoum. 1997. Combination therapy with amphotericin B and fluconazole against invasive candidiasis in neutropenic mouse and infective endocarditis rabbit models. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:1345-1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sugar, A. M., and X. P. Liu. 1998. Interactions of itraconazole with amphotericin B in the treatment of murine invasive candidiasis. J. Infect. Dis. 177:1660-1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sugar, A. M., C. A. Hitchcock, P. F. Troke, and M. Picard. 1995. Combination therapy of murine invasive candidiasis with fluconazole and amphotericin B. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:598-601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]