Abstract

Brain imaging and protein expression, from both cerebrospinal fluid and blood plasma, have been found to provide complementary information in predicting the clinical outcomes of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). But the underlying associations that contribute to such a complementary relationship have not been previously studied yet. In this work, we will perform an imaging proteomics association analysis to explore how they are related with each other. While traditional association models, such as Sparse Canonical Correlation Analysis (SCCA), can not guarantee the selection of only disease-relevant biomarkers and associations, we propose a novel discriminative SCCA (denoted as DSCCA) model with new penalty terms to account for the disease status information. Given brain imaging, proteomic and diagnostic data, the proposed model can perform a joint association and multi-class discrimination analysis, such that we can not only identify disease-relevant multimodal biomarkers, but also reveal strong associations between them. Based on a real imaging proteomic data set, the empirical results show that DSCCA and traditional SCCA have comparable association performances. But in a further classification analysis, canonical variables of imaging and proteomic data obtained in DSCCA demonstrate much more discrimination power toward multiple pairs of diagnosis groups than those obtained in SCCA.

Keywords: Imaging genomics, Alzheimer’s disease, Proteomics, Canonical correlation analysis, Multi-class discrimination

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) has been well known as one of the most common brain dementia, a major neurodegenerative disorder that has been characterized by gradual memory loss and brain behavior impairment. According to the latest report,1 more than 5 million Americans are living with Alzheimer’s and it has been officially listed as the 6th leading cause of death. Also, due to the significant decline of self-care capabilities during disease, it is not only the patients who suffer, but also the family members, friends, communities and the whole society considering the time-consuming daily care and high health care expenditures needed. In the past decade, deaths attributed to Alzheimer’s disease has increased 68 percent, while deaths attributed to the number one cause, heart disease, has decreased 16 percent. And all of these situations will continue to deteriorate as the population ages during the next several decades. To prevent such health care crisis, substantial efforts have been made to help cure, slow or stop the progression of the disease.

In the last few years, many efforts have been dedicated to explore whether the combination of multi-modal measures, e.g. brain atrophy measured by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), hypometabolism measured by functional imaging and quantification of proteins, can better predict the clinical outcomes of AD, such as disease status and cognitive outcomes.19 In many of these works, it has been found that brain imaging and protein expression, from both cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and blood plasma, hold some complementary information.12,18 But how they are related with each other still remains elusive.

In this work, we will explore the relationships between brain imaging and protein expression using bi-multivariate association models. Sparse Canonical Correlation Analysis (SCCA)11,16 is a typical example that has been widely used for associative analysis in both real8,15 and simulated3 -omics data sets.2,11,17 But it can not guarantee the selection of disease-relevant biomarkers and therefore the associations generated in SCCA are not necessarily related to a specific disease either, unless the input features are already prefiltered disease-related biomarkers.5 On the other hand, most existing SCCA algorithms use the soft threshold strategy for solving the Lasso11,16 regularization terms, which assumes the independence structure of data features. Unfortunately, this independence assumption does not hold in neither imaging nor proteomics data, and will inevitably limit the capability of yielding optimal solutions.

To overcome these limitations, we propose a novel discriminative SCCA (DSCCA) model, coupled with a new algorithm to eliminate the independence assumption, to explore the imaging and proteomic associations. Given imaging, proteomic and diagnostic data, the proposed model can perform a joint association and multi-class discrimination analysis. As such, we can not only identify disease-relevant multimodal biomarkers, but also reveal strong association between them. We perform an empirical comparison between the proposed DSCCA algorithm and a widely used SCCA implementation in the PMA software package (http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/PMA/).16 The results show that DSCCA and SCCA have comparable association performances. But in a further classification analysis, canonical variables of imaging and proteomic data obtained in DSCCA demonstrate much more discrimination power toward diagnosis groups than those obtained in SCCA.

2. Discriminative SCCA (DSCCA)

Throughout this section, we denote vectors as boldface lowercase letters and matrices as boldface uppercase ones. For a given matrix M = (mij), we denote its i-th row and j-th column to mi and mj respectively. Let X = {x1, …, xn} ⊆ ℜp be the imaging data and Y = {y1, …, yn} ⊆ ℜq be the protein data, where n is the number of participants, p and q are the number of brain regions and proteins respectively.

Canonical correlation analysis (CCA) is a bi-multivariate method that explores the linear transformations of variables X and Y to achieve the maximal correlation between Xu and Yv, which can be formulated as:

| (1) |

where u and v are canonical loadings or weights, reflecting the significance of each feature in identified associations.

However, the power of CCA in biomedical applications is quite limited due to 1) its requirement on the relatively large number of observations n which is expected to exceed the combined dimension of X and Y, and 2) its nonsparse outputs u and v which make the ultimate pattern hard to interpret. To address this concerns, sparse CCA (SCCA) method was later proposed, where two penalty terms on both weight vectors P1(u) ≤ c1 and P2(v) ≤ c2 were introduced to help generate sparse results.

A widely used SCCA implementation, PMA package,16 applied L1 norm penalty for both P1 and P2. But without diagnosis information, its capability in identifying disease-relevant biomarkers is quite limited. Thus the ultimate association relationships are not necessarily related to a specific disease either. Another limitation of PMA is that it takes the soft threshold strategy in the solution, which requires the input data to have an linear independence design XTX = I and YTY = I (see Section 10 in14). Unfortunately, this independence assumption does not hold in both imaging and proteomics data (e.g., correlated voxels in an ROI, correlated protein expressions), and will inevitably limit the capability of identifying meaningful imaging proteomics associations.

To overcome these limitations, we propose a novel discriminative SCCA (denoted as DSCCA) algorithm to not only take into account the diagnosis information but also eliminate the independence assumption. Inspired by the application of locality preserving projection (LPP) in linear discriminative analysis,10 we add two new constraints as P1 and P2 for multi-class discrimination.

| (2) |

Here, we construct two graphs Gw and Gb to account for the diagnosis groups, where each vertex indicates one subject (Fig. 1). In Gw, only subjects within the same diagnosis group have connections to each other. In other words, we build a complete graph for all the subjects belonging to the same diagnosis group. In Gb, only subjects from different diagnosis groups have connections. Lw and Lb are the Laplacian graphs of Gw and Gb respectively. While the traiditonal L1 norm helps ascertain the sparsity of selected imaging and protein biomarkers, the new penalty term ‖ · ‖D encourages the closeness between subjects within the same diagnosis groups and distance between subjects from different diagnosis groups after projection. α is a trade off parameter that help balance the within- and between-group constraints. Since canonical variables Xu and Yv have the exact same length, we use the same α for both penalties P1 and P2.

Fig. 1.

Illustration of within- and between-group graphs Gw and Gb. Each circle indicates one subject and subjects from the same diagnosis group are colored the same.

The final objective function of DSCCA can be written as follows:

| (3) |

Using Lagrange multipliers, Eq. (3) can be reformulated as follows:

| (4) |

Eq. (4) is known as a bi-convex problem, which can be easily solved using an alternating algorithm as discussed in.16 By fixing u and v respectively, we will have the following two minimization problems shown in Eq. (5) and (6).

| (5) |

| (6) |

Both objective functions can be efficiently solved using the Nesterovs accelerated proximal gradient optimization algorithm.9 Algorithm 2.1 summarizes the optimization procedure. The convergence is based on the value changes of the objective function and we use 10−6 as stop criteria. Five-fold nested cross-validation was applied to automatically tune the parameters β1, β2, λ1 and λ2. According to,2 the learned pattern and performance are insensitive to γ1 and γ2 settings. Therefore in this paper we set both of them to 1 for simplicity. The optimization method used in steps 3 and 4 is similar to that proposed in.9

Algorithm 2.1.

Discriminative SCCA (DSCCA)

| Require: | |

| X = {x1, …, xn}, Y = {y1, …, yn}, Lw ⊆ ℜn×n, Lb ⊆ ℜn×n | |

| Ensure: | |

| Canonical vectors u and v. | |

| 1: | t = 1, Initialize ut ∈ ℜp×1, vt ∈ ℜq×1; |

| 2: | while not converge do |

| 3: | Solve Eq. (5) using Nesterov’s method and obtain u; |

| 4: | Solve Eq. (6) using Nesterov’s method and obtain v; |

| 5: | Scale u so that uTu = 1 |

| 6: | Scale v so that vTv = 1 |

| 7: | t = t + 1. |

| 8: | end while |

3. Results

3.1. Data and Experimental Setting

The MRI data, quantification of proteins in CSF and blood plasma were downloaded from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database. The primary goal of ADNI has been to test whether serial MRI, PET, other biological markers, and clinical and neuropsychological assessment can be combined to measure the progression of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and early AD. For up-to-date information, see adni.loni.usc.edu.

We totally extracted 246 subjects with all MRI, CSF and plasma proteomic data available. To balance the diagnostic groups, we randomly removed some mild cognitive impairment (MCI) participants. Finally, 176 subjects (67 AD, 67 MCI and 42 healthy control (HC)), were included in this study (Table 1). For each baseline MRI scan, FreeSurfer (FS) V4 was employed to extract 73 cortical thickness measures and 26 volume measures, as well as to extract the intracranial volume (ICV). CSF and blood plasma samples were evaluated by Rules Based Medicine, Inc. (RBM) proteomic panel and 229 proteomic analytes survived the quality control process, with 83 from CSF and 146 from plasma. Using the regression weights from HC participants, all the MRI, CSF and blood plasma proteomic measures were pre-adjusted for the baseline age, gender, education, and handedness, with ICV as an additional covariate for MRI only.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| HC | MCI | AD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 67 | 67 | 42 |

| Gender(M/F) | 38/29 | 45/22 | 22/20 |

| Handedness(R/L) | 64/3 | 64/3 | 38/4 |

| Age(mean±std) | 75.15±7.68 | 74.28±7.25 | 75.93±5.82 |

| Education(mean±std) | 15.12±3.01 | 15.96±2.92 | 15.88±2.77 |

3.2. Experimental Results

Both DSCCA and PMA were performed on the normalized FS and proteomic measures. To avoid the over-fitting problem, 5-fold nested cross-validation was applied, which also helped to optimally tune the parameters. Table 2 shows 5-fold cross-validation canonical correlation results. It is observed that proposed DSCCA and PMA have comparable performances in identifying imaging proteomic associations, whereas DSCCA is slightly better in performance stability.

Table 2.

Five-fold cross validation canonical correlation results

| f1 | f2 | f3 | f4 | f5 | mean | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DSCCA | Train | 0.796 | 0.670 | 0.820 | 0.680 | 0.636 | 0.720 |

| Test | 0.424 | 0.476 | 0.281 | 0.392 | 0.312 | 0.377 | |

| PMA | Train | 0.529 | 0.629 | 0.505 | 0.524 | 0.504 | 0.538 |

| Test | 0.410 | 0.095 | 0.324 | 0.201 | 0.460 | 0.298 | |

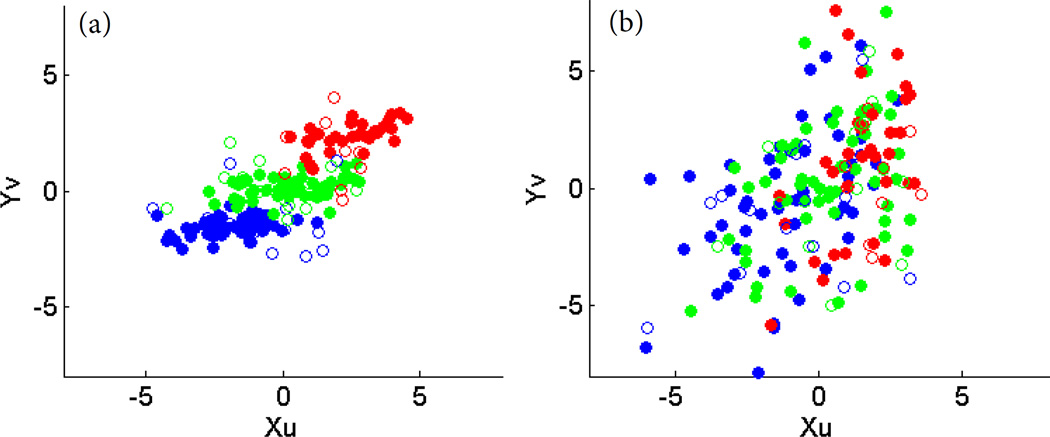

Next, we examined the discriminative power of canonical variables Xu and Yv generated by DSCCA and PMA. Area under ROC curve (AUC) was calculated for each single canonical variable of five folds. Both imaging and proteomic canonical variables of PMA and imaging canonical variable of DSCCA were found to have little discrimination power in all HC vs MCI, HC vs AD and MCI vs AD cases. Proteomic canonical variable Yv of DSCCA has the best performance, with an averaged AUC around 0.7 for all three cases. Shown in Fig. 2 is an example plot of Xu against Yv in one fold. Dot colors represent different diagnostic groups. Compared to one single canonical variable, we observe that combination of two canonical variables generated in DSCCA demonstrated much more discrimination power than PMA. In Fig. 2(a) three diagnosis groups are all very well separated, whereas in Fig. 2(b) subjects are mixing together.

Fig. 2.

Plot of canonical variables Xu and Yv. Left: DSCCA; Right: PMA; Red: AD; Green: MCI; Blue: HC; Solid: Training; Circle: Test.

To further validate our results, a follow up classification analysis was performed using both imaging and proteomic canonical variables as predictors. Canonical loadings learned in the training data set are applied to both training and test data to calculate the training and test canonical variables respectively. The LIBSVM toolbox was employed to implement the SVM using a linear kernel under default settings. Three pair-wise binary classification analyses were performed between HC vs MCI, HC vs AD, and MCI vs AD respectively. Shown in Table. 3 are the classification performance comparison between DSCCA and PMA. The results are very encouraging. Canonical variables of DSCCA significantly outperformed those of PMA in terms of the overall accuracy in almost all the cases. The resulting best prediction rates for HC vs AD (92.1%), HC vs MCI (75.3%) and MCI vs AD (70.3%) were competitive with prior multi-modal studies,6,19 especially considering that it is under default parameter settings.

Table 3.

Five-fold cross validation classification performances (%) using canonical variables Xu and Yv. HC vs MCI, MCI vs AD, and HC vs AD are performed as three tasks separately.

| Train | Test | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HC vs MCI | HC vs AD | MCI vs AD | HC vs MCI | HC vs AD | MCI vs AD | ||

| DSCC | f1 | 97.17 | 100.00 | 94.19 | 75.00 | 91.30 | 60.87 |

| f2 | 86.79 | 96.51 | 84.88 | 85.71 | 95.65 | 60.87 | |

| f3 | 96.23 | 100.00 | 94.19 | 85.71 | 91.30 | 86.96 | |

| f4 | 93.40 | 95.35 | 75.58 | 57.14 | 100.00 | 78.26 | |

| f5 | 72.32 | 82.61 | 69.57 | 72.73 | 82.35 | 64.71 | |

| mean | 89.18 | 94.89 | 83.68 | 75.26 | 92.12 | 70.33 | |

| PMA | f1 | 60.38 | 77.91 | 65.12 | 71.43 | 86.96 | 73.91 |

| f2 | 66.98 | 84.88 | 74.42 | 71.43 | 95.65 | 60.87 | |

| f3 | 66.04 | 80.23 | 63.95 | 50.00 | 86.96 | 60.87 | |

| f4 | 68.87 | 80.23 | 59.30 | 42.86 | 82.61 | 78.26 | |

| f5 | 65.18 | 77.17 | 60.87 | 31.82 | 64.71 | 64.71 | |

| mean | 65.49 | 80.09 | 64.73 | 53.51 | 83.38 | 67.72 | |

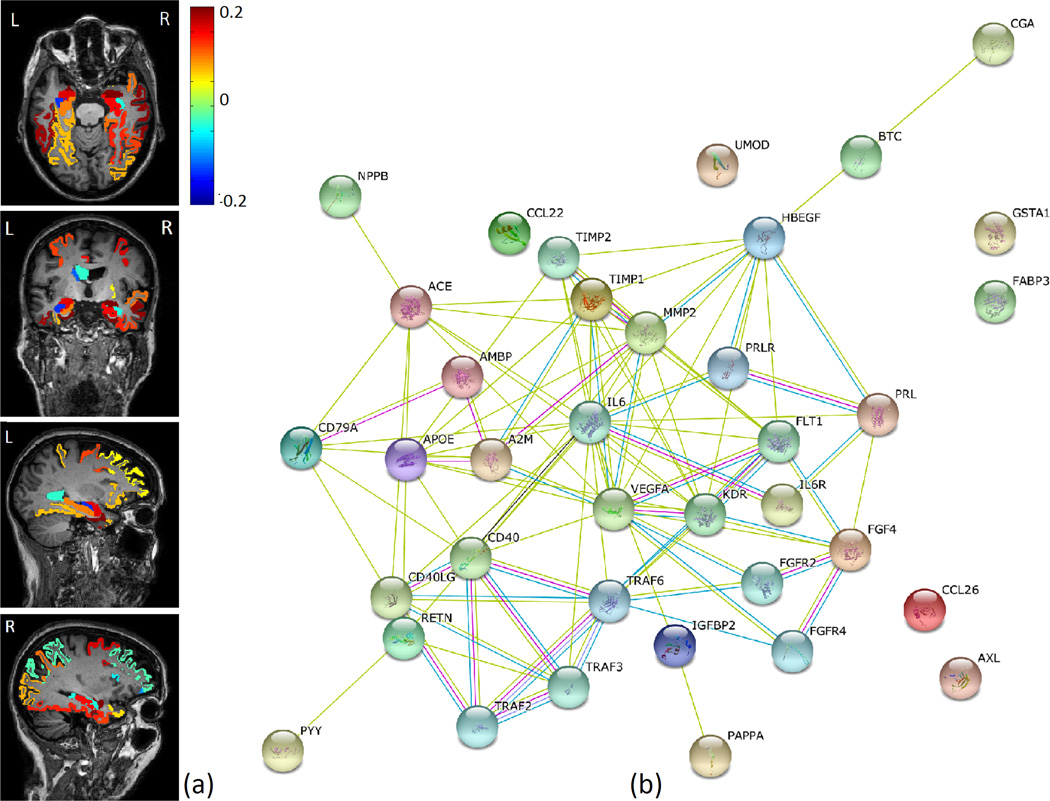

All five-fold experiments generated similar sparse results in terms of selection of imaging and proteomic markers. Fig. 3 shows the imaging and proteomic markers commonly identified across all folds using DSCCA, where the color represents the weights of corresponding brain regions. Top brain regions identified include entorhinal cortex, amygdala volume, hippocampal volume, etc. (Fig. 3(a)), which are all aligned with previous AD findings.12,19 In terms of proteomic markers, expression levels of 12 proteins from CSF and 19 proteins from blood plasma were found to be strongly associated with those brain regions. According to the STRING database (http://string-db.org/), these proteins are highly interconnected with each other, as shown in Fig. 3(b). Edges are colored based on the evidence of the connection, such as experimental interaction, co-expression or co-occurrence in the literature. The more edges two proteins have, the more confident their connection will be.

Fig. 3.

Common imaging and proteomic markers across 5-fold cross-validation. (a): Mapping of imaging canonical loadings onto the brain; (b): Known interactions between identified protein biomarkers from STRING database.

In particular, four proteins, apolipoprotein E (APOE), AXL receptor tyrosine kinase(AXL), interleukin 6 receptor (IL6R) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), were identified in both CSF and blood plasma. APOE is the top risk gene of AD. AXL is a member of the Tyro3-Axl-Mer (TAM) receptor tyrosine kinase subfamily, which has been previously reported to be involved in Amyloidogenic APP Processing and β-Amyloid Deposition in AD.20 For growth factor VEGF, both its variants and expression changes are found to be associated with AD.4,13 IL6R is less explored in terms of its relationship with dementia. But in a recent study it was reported to have significant associations with proteins involved in amyloid processing and inammation.7 These findings suggest the existence of certain connections between brain and blood biomarkers. Thus, more accessible fluid biomarkers from blood should have potential to provide extra insights of AD and guidance for future therapeutic intervention activities.

4. Discussion

We performed an integrative analysis of brain imaging and protein expression data to jointly identify AD related biomarkers and their associations using a new sparse learning model DSCCA. The overall association performance of DSCCA is better than SCCA. the combination of its two canonical variables are much more powerful in discriminating multiple diagnostic groups simultaneously. Using both imaging and proteomic canonical variables in DSCCA as predictors, we obtained very promising prediction performances: HC vs AD (92.1%), HC vs MCI (75.3%) and MCI vs AD (70.3%), which were competitive with prior multi-modal studies. Since the classification was done under default parameter settings and the sample size is very limited, we expect improved performances with more advanced parameter optimization strategies and/or larger sample sizes.

In real applications, many identified proteomic markers are found to be interconnected, but the underlying mechanisms still warrant further investigation. Replication in independent large samples will be important to confirm these findings. Further pathway enrichment analysis could be performed as a future direction to identify underlying biological pathways of relevant genes and proteins. Considering the ever increasing data volume and diversity in many complex diseases, another potential future topic is to investigate whether DSCCA can help identify valuable complementary information between new -omics features and further improve the classification performance.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH R01 EB022574, R01 LM011360, U01 AG024904, R01 AG19771, P30 AG10133, UL1 TR001108, K01 AG049050 and R00 LM011384; DOD W81XWH-14-2-0151, W81XWH-13-1-0259, and W81XWH-12-2-0012; and NCAA 14132004 at Indiana University.

Data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: Abbott; Alzheimer’s Association; Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation; Amorfix Life Sciences Ltd.; AstraZeneca; Bayer HealthCare; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen Idec Inc.; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; GE Healthcare; Innogenetics, N.V.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC.; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC.; Medpace, Inc.; Merck & Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC.; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc.; Servier; Synarc Inc.; and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study at the University of California, San Diego. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California.

Contributor Information

Jingwen Yan, Email: jingyan@iupui.edu, Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University, Center for Computational Biology and Bioinformatics, School of Medicine, Indiana University, Indianapolis, 46202, USA.

Shannon L. Risacher, Email: srisache@iupui.edu, Department of Radiology and Imaging Sciences, School of Medicine, Indiana University, Indianapolis, 46202, USA.

Kwangsik Nho, Email: knho@iupui.edu, Department of Radiology and Imaging Sciences, School of Medicine, Indiana University, Indianapolis, 46202, USA.

Andrew J. Saykin, Email: asaykin@iupui.edu, Department of Radiology and Imaging Sciences, School of Medicine, Indiana University, Indianapolis, 46202, USA.

Li Shen, Email: shenli@iu.edu, Department of Radiology and Imaging Sciences, School of Medicine, Indiana University, Center for Computational Biology and Bioinformatics, School of Medicine, Indiana University, Indianapolis, 46202, USA.

References

- 1.Alzheimers-Association: Alzheimers disease facts and figures. Alzheimers and Dementia. 2016;12:4. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen X, Liu H, Carbonell JG. Structured sparse canonical correlation analysis; International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chi E, Allen G, et al. Imaging genetics via sparse canonical correlation analysis; Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), 2013 IEEE 10th Int Sym on; 2013. pp. 740–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Del Bo R, Ghezzi S, Scarpini E, Bresolin N, Comi G. Vegf genetic variability is associated with increased risk of developing alzheimer’s disease. Journal of the neurological sciences. 2009;283(1):66–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2009.02.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Du L, Yan JW, Kim S, Risacher SL, Huang H, Inlow M, Moore JH, Saykin AJ, Shen L, Initia ADN. A novel structure-aware sparse learning algorithm for brain imaging genetics. Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention - Miccai 2014, Pt Iii. 2014;8675:329–336. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-10443-0_42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hinrichs C, Singh V, Xu G, Johnson SC. Predictive markers for ad in a multi-modality framework: an analysis of mci progression in the adni population. Neuroimage. 2011;55(2):574–589. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.10.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kauwe J, Bailey M, Ridge P, Perry R, Wadsworth M, Hoyt K, Ainscough B. Genome-wide association study of csf levels of 59 alzheimer’s disease candidate proteins: significant associations with proteins involved in amyloid processing and inammation. Plos Genetics. 2014;10(10):e1004758. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin D, Calhoun VD, Wang YP. Correspondence between fMRI and SNP data by group sparse canonical correlation analysis. Med Image Anal. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.media.2013.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu J, Ji S, Ye J. Proceedings of the twenty-fifth conference on uncertainty in artificial intelligence. AUAI Press; 2009. Multi-task feature learning via efficient l2,1-norm minimization; p. 339. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu K, Ding ZM, Ge S. Sparse-representation-based graph embedding for traffic sign recognition. Ieee Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems. 2012;13(4):1515–1524. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parkhomenko E, Tritchler D, Beyene J. Sparse canonical correlation analysis with application to genomic data integration. Statistical Applications in Genetics and Molecular Biology. 2009;8:1–34. doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shen L, Kim S, Qi Y, Inlow M, Swaminathan S, Nho K, Wan J, Risacher SL, Shaw LM, Trojanowski JQ, Weiner MW, Saykin AJ, Adni Identifying neuroimaging and proteomic biomarkers for mci and ad via the elastic net. Multimodal Brain Image Analysis. 2011;7012:27–34. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-24446-9_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tarkowski E, Issa R, Sjgren M, Wallin A, Blennow K, Tarkowski A, Kumar P. Increased intrathecal levels of the angiogenic factors vegf and tgf- in alzheimers disease and vascular dementia. Neurobiology of aging. 2002;23(2):237–243. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(01)00285-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tibshirani R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological) 1996;58(1):267–288. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wan J, Kim S, et al. Hippocampal surface mapping of genetic risk factors in AD via sparse learning models. MICCAI. 2011;14(Pt 2):376–383. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-23629-7_46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Witten DM, Tibshirani R, Hastie T. A penalized matrix decomposition, with applications to sparse principal components and canonical correlation analysis. Biostatistics. 2009;10(3):515–534. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxp008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yan J, Du L, Kim S, Risacher SL, Huang H, Moore JH, Saykin AJ, Shen L. Transcriptome-guided amyloid imaging genetic analysis via a novel structured sparse learning algorithm. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(17):i564–i571. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yan J, H H, Kim S, Moore J, Saykin A, Shen L, Initia ADN. Proceedings of the twenty-fifth conference on uncertainty in artificial intelligence. IEEE; 2014. Joint identification of imaging and proteomics biomarkers of alzheimer’s disease using network-guided sparse learning; pp. 665–668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang DQ, Wang YP, Zhou LP, Yuan H, Shen DG, Initia ADN. Multimodal classification of alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Neuroimage. 2011;55(3):856–867. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zheng Y, Wang Q, Xiao B, Lu Q, Wang Y, Wang X. Involvement of receptor tyrosine kinase tyro3 in amyloidogenic app processing and -amyloid deposition in alzheimer’s disease models. Plos One. 2012;7(6):e39035. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]