Abstract

Purpose:

To develop directional fractal signature methods for the analysis of trabecular bone (TB) texture in hand radiographs. Problems associated with the small size of hand bones and the orientation of fingers were addressed.

Methods:

An augmented variance orientation transform (AVOT) and a quadrant rotating grid (QRG) methods were developed. The methods calculate fractal signatures (FSs) in different directions. Unlike other methods they have the search region adjusted according to the size of bone region of interest (ROI) to be analyzed and they produce FSs defined with respect to any chosen reference direction, i.e., they work for arbitrary orientation of fingers. Five parameters at scales ranging from 2 to 14 pixels (depending on image size and method) were derived from rose plots of Hurst coefficients, i.e., FS in dominating roughness (FSSta), vertical (FSV) and horizontal (FSH) directions, aspect ratio (StrS), and direction signatures (StdS), respectively. The accuracy in measuring surface roughness and isotropy/anisotropy was evaluated using 3600 isotropic and 800 anisotropic fractal surface images of sizes between 20 × 20 and 64 × 64 pixels. The isotropic surfaces had FDs ranging from 2.1 to 2.9 in steps of 0.1, and the anisotropic surfaces had two dominating directions of 30° and 120°. The methods were used to find differences in hand TB textures between 20 matched pairs of subjects with (cases: approximate Kellgren-Lawrence (KL) grade ≥2) and without (controls: approximate KL grade <2) radiographic hand osteoarthritis (OA). The OA Initiative public database was used and 20 × 20 pixel bone ROIs were selected on 5th distal and middle phalanges. The performance of the AVOT and QRG methods was compared against a variance orientation transform (VOT) method developed earlier [M. Wolski, P. Podsiadlo, and G. W. Stachowiak, “Directional fractal signature analysis of trabecular bone: evaluation of different methods to detect early osteoarthritis in knee radiographs,” Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng., Part H 223, 211–236 (2009)].

Results:

The AVOT method correctly quantified the isotropic and anisotropic surfaces for all image sizes and scales. Values of FSSta were significantly different (P < 0.05) between the isotropic surfaces. Using the VOT and QRG methods no differences were found at large scales for the isotropic surfaces that are smaller than 64 × 64 and 48 × 48 pixels, respectively, and at some scales for the anisotropic surfaces with size 48 × 48 pixels. Compared to controls, using the AVOT and QRG methods the authors found that OA TB textures were less rough (P < 0.05) in the dominating and horizontal directions (i.e., lower FSSta and FSH), rougher in the vertical direction (i.e., higher FSV) and less anisotropic (i.e., higher StrS) than controls. No differences were found using the VOT method.

Conclusions:

The AVOT method is well suited for the analysis of bone texture in hand radiographs and it could be potentially useful for early detection and prediction of hand OA.

Keywords: trabecular bone, fractal signature, radiographs, hand osteoarthritis

I. INTRODUCTION

The most common form of arthritis in hand is osteoarthritis (OA),1 which is also a risk factor for developing the disease in other joints, especially in knees and hips.2,3 Hand OA is characterised by slow degenerative changes of articular cartilage and bones in finger joints. The changes are currently assessed primarily by visual grading of joint space narrowing and osteophytes on radiographs using hand radiograph atlases.4 However, the visual assessment of hand radiographs is often inaccurate because the change of cartilage volume in the joints is small and the grading requires experienced observers in order to be reproducible and also, it is not sensitive to early OA changes.5,6 Thus, there is an urgent need to develop methods that would allow a reliable assessment of hand radiographs for the prognosis and diagnosis of early OA.7,8

Such method could be based on the analysis of trabecular bone (TB) texture selected on hand radiographs. Previous studies showed that: (i) the structure of TB changes at early stages of OA,9–11 (ii) it exhibits fractal properties, i.e., the self-similarity over a range of scales,12 and (iii) radiographic technique produces 2D projections of TB, called TB texture images, which are related to the underlying 3D bone structure.13 Several methods have been used to quantify hand TB texture images. They include statistical methods such as second-order histogram statistics of gray-scale level values14 and co-occurrence and run-length matrices.15,16 However, their usefulness is limited by not accounting for the fractal properties of TB texture. Studies showed that the fractals are related to 3D bone structure.13,17 Therefore, a fractal approach, called a maximum likelihood estimator (MLE) was used.15,16 In this approach, fractal dimensions (FDs) are estimated in different directions. The dimensions are a measure of the roughness of bone texture on radiographs, i.e., higher dimension values correspond to higher roughness. Although the MLE yields useful results it does not quantify TB at individual scales in each direction. Studies showed that OA TB texture changes occur at individual scales and in different directions.18 These changes in texture could be quantified using a directional fractal signature (DFS) method, called a variance orientation transform (VOT) method.19 The method has the ability to produce fractal signatures (FSs) in many different directions. FS is a set of FDs calculated at individual trabecular image sizes (i.e., scales). The VOT method calculates Hurst coefficients (H) at nine scales in different directions through fitting lines to log–log plots of variances of absolute differences of gray-scale level values of pixel pairs against distances between the pixels. Having the gray-scale level as the third dimension in addition to the x-y coordinates, H is related to FD as FD = 3-H. The differences and distances are calculated in directions containing at least four pixels within a circular search region of predefined size (i.e., a ring with inner and outer radii of 4 and 16 pixels, respectively) that moves across the entire image. The directions are measured with respect to the image horizontal axis.

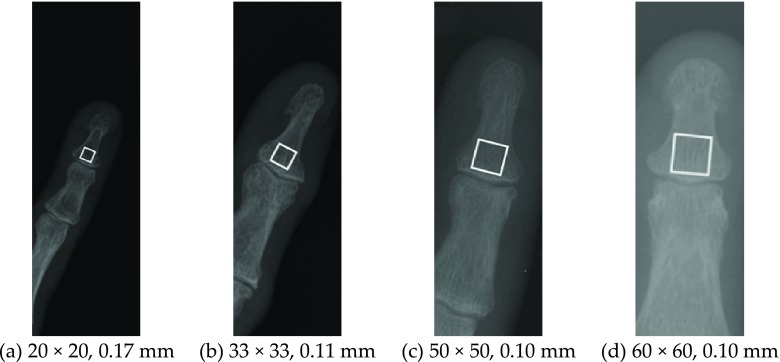

Previous studies showed that the VOT method can be a valuable tool in early detection and prediction of knee OA.20,21 However, its suitability for the analysis of hand OA is not yet known. There are two main reasons for this. The first reason is that hand bones are much smaller than the tibia and femur. Bone texture regions selected on hand radiographs can have a size of 20 × 20 pixels (Fig. 1), which can be almost 13 times smaller than those selected on knee radiographs (e.g., 256 × 256 pixels). We conducted a preliminary study on small images (unpublished results). Fifty 20 × 20 pixel computer generated images of isotropic fractal surfaces with known theoretical fractal dimension FDt = 2.1, 2.3, 2.5, 2.7, and 2.9 (10 images per FDt) were generated and the VOT method was applied to these images. We found that the FDs calculated by the VOT method do not increase in parallel with the FDt. Based on this preliminary study we concluded that the search region used in the method is too large for such small images (small number of pairs of pixels separated by large distances), Hurst coefficients are not calculated for the lowest and highest distances and for the directions containing less than four pixels. The second reason is that the longitudinal direction of hand bones is often not perpendicular to the horizontal axis of x-ray images (fingers are oriented in different directions). Consequently, FSs calculated by the VOT method in the horizontal and vertical directions have no interpretation, i.e., the orientation of these two directions with respect to the finger longitudinal direction is not known. Previous studies suggest that analyzing bone texture along these directions is important in the study of OA.18,22,23 The problems associated with the size of hand bones and the orientation of fingers are addressed in this paper.

FIG. 1.

Examples of x-ray images of (a–c) 5th and (d) 3th distal phalanges with marked bone texture regions (white squares). The images have pixel resolutions and regions ranging from 0.17 to 0.10 mm and from 20 × 20 to 60 × 60 pixels, respectively.

In the present study, first, two new DFS methods are developed for hand bones, i.e., an augmented VOT (AVOT) and a quadrant rotating grid (QRG) methods. Unlike the VOT method, the new methods have the search region adjusted according to the size of TB texture region selected, produce FSs that can be defined with respect to any chosen reference direction (not necessary the horizontal direction) and use directions with any number of pixels. These were achieved through the development of a new selection algorithm for directions and pixels within the search region, called a recursive multidirectional pixel selection (RMPS) algorithm. Also, in the AVOT method, the size of the two marginal log–log data subsets is reduced from five to three. In the QRG method, Hurst coefficients are calculated at individual scales using an ergodic quadrant estimator instead of the line fittings. The reduction in subsets and the estimator allow for the calculation of Hurst coefficients at lower and higher scales than those used in the VOT method. Second, the accuracy of newly developed methods is evaluated against the VOT method on computer-generated isotropic and anisotropic fractal surface images with known both theoretical FDs and dominating directions. The images had sizes ranging from 20 × 20 to 64 × 64 pixels. The range covers sizes of small regions that can be selected on hand radiographs (Fig. 1). Finally, the ability of the methods to detect OA differences in hand TB textures is tested. For this purpose, TB texture regions were selected on hand radiographs of subjects with (approximate Kellgren-Lawrence (KL) grade ≥2) and without (approximate KL grade <2) radiographic hand OA. The radiographs were obtained from the Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI) database which is available for public access at http://www.oai.ucsf.edu.

II. METHODS AND MATERIALS

Since the VOT method is a base on which the new AVOT method is built, it is described first. Details of the VOT method are given in Ref. 19.

II.A. Texture representation

Texture data is represented as Nx × Ny pixels digital image, where Nx and Ny are the number of pixels in the horizontal and vertical directions, respectively. Let Lx = {1, 2, …, Nx}, Ly = {1, 2, …, Ny} and Lz = {−1, 0, 1, …, Nz} be spatial domains X, Y and gray-scale level domain Z, respectively. Lz = −1 denotes an “empty” pixel, i.e., the pixel that is not used in calculations. Then the image can be defined as a function zij = I(xi, yj) which assigns a gray-scale level value zij ∈ Lz to a pixel located at (xi, yj) ∈ Lx × Ly, where xi and yj are integer numbers representing coordinates of pixels in X and Y domains, i = 1, 2, …, Nx, j = 1, 2, …, Ny, and Nz = 255 is the total number of gray-scale level values.

II.B. VOT method

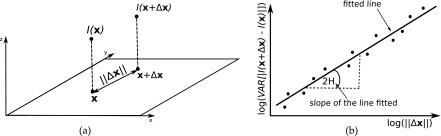

Assuming that z = I(x, y) is generated by a fractal Brownian function, the variance of differences I(x + Δx) − I(Δ) can be given by24,25

| (1) |

where x = (x, y) is the coordinate vector, ‖Δx‖ is the distance between a pair of points [Fig. 2(a)] and H is the Hurst coefficient. By plotting variances against distances (for all x and Δx) in log–log coordinates and fitting a line to the plot, H can be calculated as a half of the slope of the line fitted [Fig. 2(b)].25 The coefficient is related to the fractal dimension as FD = 3 − H.

FIG. 2.

Schematic illustration of (a) the difference I(x + Δx) − I(x) and the distance Δx, and (b) the log–log plot of variances against distances with the line fitted and the Hurst coefficient H.

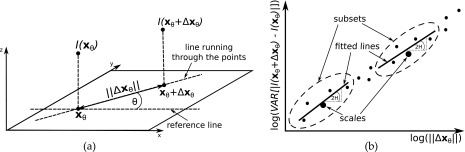

The Hurst coefficients can be calculated at different scales and directions. The direction is defined as an angle θ between the line running through a pair of points and the reference line (e.g., the horizontal axis) [Fig. 3(a)]. For each direction, a log–log plot of variances against distances (for x and Δx along the direction) is constructed and then, divided into overlapping subsets. A line is fitted to each subset and a set of Hurst coefficients are then calculated at individual scales using slopes of the subset lines fitted. The scale is the distance corresponding to the middle point of the subset [Fig. 3(b)].

FIG. 3.

Schematic illustration of (a) the difference I(xθ + Δxθ) − I(xθ) and the distance Δxθ in direction θ and (b) the log-log plot of variances against distances for θ with the lines fitted to subsets and the Hurst coefficients. Scales are distances associated with the middle points of subsets.

The VOT method calculates the Hurst coefficients in the following steps:19

-

1.

Let j = 1.

-

2.

Let i = 1.

-

3.

Circular search region Lxy with the inner and outer radii of r1 = 4 and r2 = 16 pixels is centred at pixel (xi, yj).

-

4.

Within the search region Lxy, absolute differences of gray-scale level values of all pairs of pixels (xi, yj) and (xnm, ynm) are calculated, where n = 1, 2, …, Nθ, m = 1, 2, …, Ndn and Nθ is the number of directions containing at least four pixels and Ndn is the number of pixels in the direction θn. The differences together with corresponding directions θn and Euclidean distances dnm between (xi, yj) and (xnm, ynm) are saved in a set R. The direction θn is defined as an angle between a line running through the pair of pixels and the image horizontal axis.

-

5.

Number of pixels in directions other than the vertical and horizontal is increased to Nd1 = 13 (r2 − r1 + 1 = 16 − 4 + 1), i.e., the number of pixels in the horizontal direction θ1. This increase is achieved in such a way that there are no overlapping pixels between directions.19 For the new pixels, the absolute differences between gray-scale values along with the distances from (xi, yj) are calculated and then added to R.

-

6.

If i < Nx then i = i + 1 and go to step 3.

-

7.

If j < Ny then j = j + 1 and go to step 2.

-

8.

For each direction θn, variances of the differences stored in R are calculated and plotted against the corresponding distances dnm in log-log coordinates. The log–log data points are divided into overlapping subsets of five points shifted by one data point, and a line is fitted to each subset. The distance dnm associated with the middle point of each subset represents an individual scale (i.e., trabecular image size), and the slope β of the line relates to H at this scale as H = β/2.

II.C. AVOT method

The VOT method has a fixed size search region, calculates FDs in directions defined with respect to the image horizontal axis, does not calculate FDs for directions containing less than four pixels and for scales associated with two lowest and two highest distances. Because of these, the method is not suited for characterization of small bone texture regions and for bone fingers which longitudinal direction is not perpendicular to the image horizontal axis. To overcome these limitations, a special algorithm for the selection of directions and pixels within a search region, called a RMPS algorithm, was developed, and the number of points in the marginal log–log data subsets was reduced from five to three.

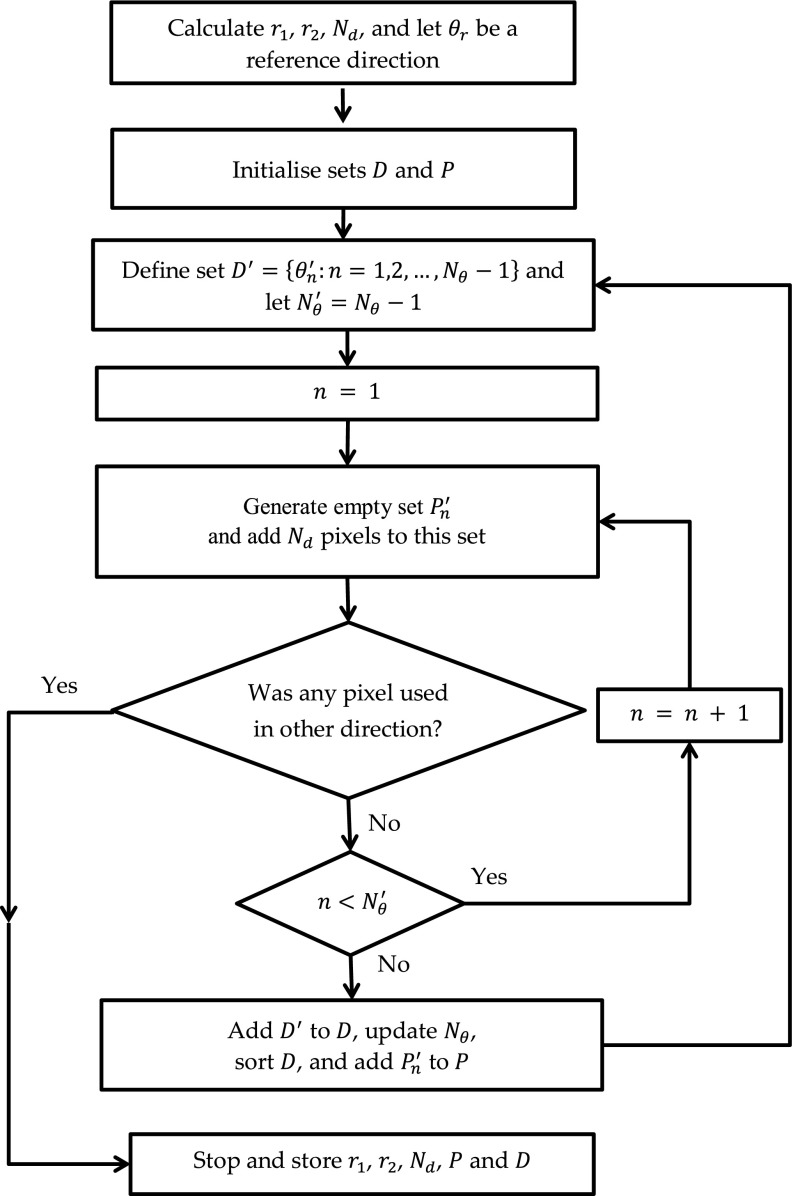

The RMPS algorithm selects recursively directions and pixels within a search region in the following steps (Fig. 4):

-

1.

The outer r2 and inner r1 radii of a search region are calculated as and floor (r2/4) pixels, respectively, where Rw and Rh are the width and height of a texture region to be analyzed, i.e., the region of interest (ROI). To each direction Nd = r2 − r1 + 1 pixels are added. The pixels are selected from the search region and details are given in Ref. 19. Let θr be a reference direction defined with respect to the image horizontal axis.

-

2.

A set D of directions within a search region is initialised with two coterminal angles, i.e., D = {θ1, θ2} where θ1 = θr and θ2 = θr + 2π. Also, a set P of pixels within the region is initialised with Nd pixels belonging to direction θ1, i.e., P = {P1}.

-

3.New directions are added to D as follows:

-

a.Define Nθ − 1} that takes values between consecutive directions in D. Let be the number of directions in D′.

-

b.Let n = 1.

-

c.Generate an empty set (i.e., a set of pixels belonging to ) and add Nd pixels to this set as defined in the VOT method. If any of the pixels added was used in other direction, then go to step 4.

-

d.If then n = n + 1 and go to step c.

-

e.Add D′ to D, set Nθ to the current number of directions in D and then, sort D in such a way that . Also, add all sets to P and go to step a.

-

a.

-

4.

Algorithm finishes and r1, r2, Nd, P, and D are stored.

FIG. 4.

Flow chart of the RMPS algorithm.

The AVOT method with the selection RMPS algorithm is executed as follows:

-

1.

Let j = 1.

-

2.

Let i = 1.

-

3.

A search region Lxy centred at pixel (xi, yj), a set of directions D, and a set of pixels P are obtained using the RMPS.

-

4.

For each pixel (xnm, ynm) ∈ Pn, where Pn is a set of pixels belonging to θn, Pn ∈ P, and each direction θn ∈ D, absolute differences of gray-scale level values of all pairs of pixels (xi, yj) and (xnm, ynm), and the Euclidean distances dnm between the pixels are calculated and then, added to R.

-

5.

If i < Nx then i = i + 1 and go to step 3.

-

6.

If j < Ny then j = j + 1 and go to step 2.

-

7.

For each direction θn, Hurst coefficients are calculated at individual scales as in the VOT method. The exception is that the two marginal subsets of log–log data points contain the first and last three points, respectively, instead of the five points. The reduction in points used allows for the calculation of the Hurst coefficients for small search regions for which the five-point subsets cannot be constructed, e.g., r1 = 1 and r2 = 4 pixels, in the VOT method.

II.D. QRG method

In the VOT and AVOT methods, Hurst coefficients at individual scales are obtained by fitting lines to subsets of log–log plot data points and individual scales are defined as distances associated with the middle points of the subsets. Because of these, the coefficients are not calculated for the lowest and highest distances. In the QRG method, this limitation was overcome by calculating Hurst coefficients using an ergodic quadrant estimator for gray-scale level values selected from the image by means of a rotating grid, i.e.:

-

1.

A set of directions D and values of r1, r2, and Nd are obtained using the RMPS.

-

2.

Let n = 1.

-

3.A square grid of Ng × Nh pixels is generated and then superimposed on the image. For 0° ⩽ θn < 90° and 180° ⩽ θn < 270°, the Ng and Nh sizes are:26

(2)

For other values of θn, the negative θn (i.e., −θn) is used.(3) -

4.

A matrix K of size Ng × Nh is generated and initialised with all values set to −1.

-

5.

The grid is rotated by an angle θn around its center. The grid's x-y coordinates are rounded off to the nearest integer values and the gray-scale level values of the pixels having the rounded off coordinates are copied into K. This process ensures that the original image data are used, not interpolated (i.e., gray-scale values obtained at noninteger coordinates using interpolation). Illustrations and description of the rotating grid algorithm can be found in Ref. 27. For directions other than horizontal and vertical directions, the size of K is larger than the image size. Thus, some values in K are −1.

-

6.The gray-scale level values are selected from rows of matrix K at distances dm = r1 + m − 1 where m = 1, 2, …, Nd and are stored into a new set Bnm. Since the matrix was obtained by means of the rotating grid, its rows contain gray-scale level values of image pixels located along direction θn on the image. This selection is performed as follows:

-

6.1.Let m = 1.

-

A.Let j = 1.

-

a.Let i = 1.

-

b.If Kji ≠ −1, then value Kji is added to Bnm.

-

c.If i < Nh − dm then i = i + dm and go to step b.

-

a.

-

B.If j < Ng then j = j + 1 and go to step a.

-

A.

-

6.2If m < Nd then m = m + 1 and go to step A.

-

6.1.

-

7.

If n < Nθ then n = n + 1 and go to step 3.

-

8.Let gray-scale level values in Bnm be represented as br where r = 1, 2, …, Nr and Nr is the total number. Also, let the differences between two consecutive values br be represented as (i.e., ). Then, for each set Bnm, Hurst coefficients are calculated using the ergodic quadrant estimator.28 This allows calculating Hurst coefficients at lowest and highest distances. Specifically, H is calculated using the following formulas:

where(4) (5) (6)

II.E. Texture parameters

For each scale, the Hurst coefficients obtained are plotted in polar coordinates as a function of direction and ellipses are fitted to the resulting rose plots. Using the ellipses fitted, three texture parameters are calculated at each scale:19

-

•

Texture minor axis Sta: It measures the dominating roughness component (i.e., FD = 3 − Sta) and is defined as half the minor axis length of the ellipse fitted.

-

•

Texture aspect ratio Str: This is a measure of the surface anisotropy/isotropy and is defined as the ratio of the minor to major axes of the ellipse fitted. For ideal isotropic surfaces (i.e., surfaces exhibiting the same roughness in all directions) Str is equal to one. For other surfaces, Str is less than one.

-

•

Texture direction Std: It indicates the dominating surface direction. In the VOT method, this is the angle between the major axis of the ellipse fitted and the reference image horizontal axis. The AVOT and QRG methods can have other directions as the reference.

Sets of Sta, Str and Std parameters calculated at individual scales are called fractal signature Sta (FSSta), texture aspect ratio signature (StrS) and texture direction signature (StdS), respectively.

II.F. Example application

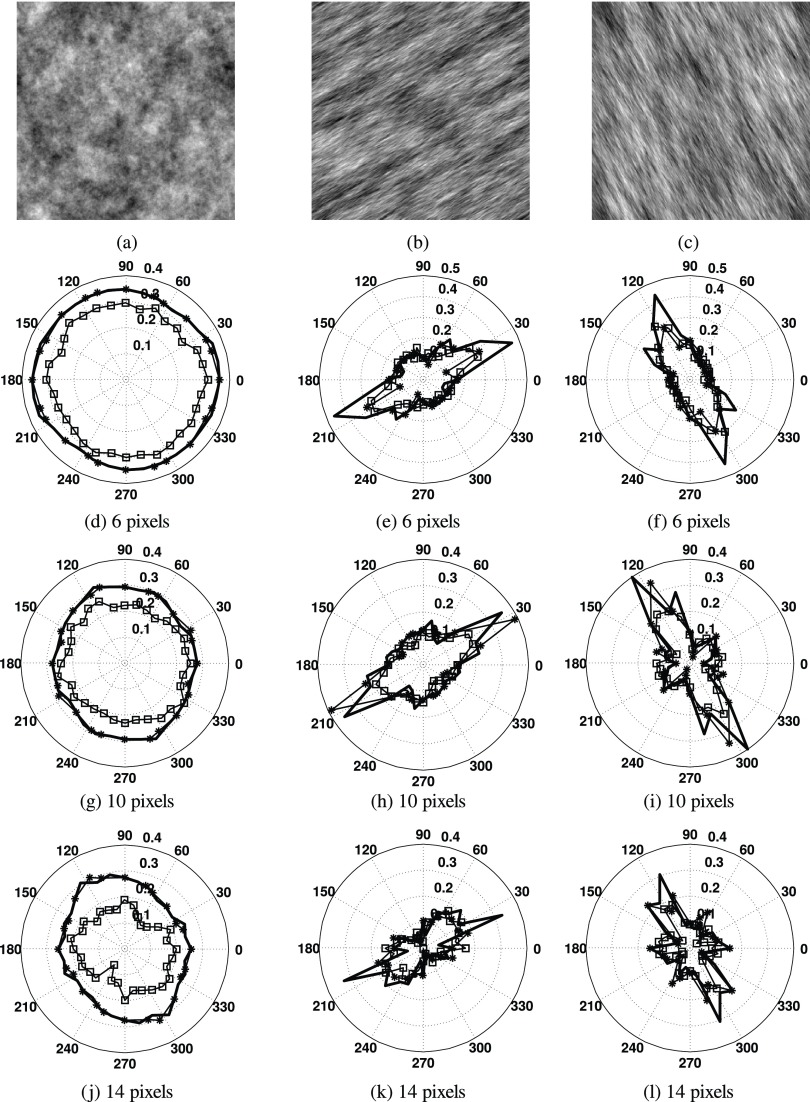

Examples are provided to illustrate the performance of the VOT, AVOT, and QRG methods in the analysis of three fractal surface images of size 256 × 256 pixels. The first surface is isotropic and has FDt = 2.7 [Fig. 5(a)]; computer generated using an interpolation method.29 The second and third surfaces are anisotropic and have the dominating direction of 30° and 120°, respectively [Figs. 5(b) and 5(c)]. An inverse Fourier transform method with FDt = 2.6 in 120° and FDt = 2.2 in 30°, and with FDt = 2.6 in 30° and FDt = 2.2 in 120°, was used to generate the surfaces.30

FIG. 5.

Images of (a) isotropic fractal surface with FDt = 2.7 and anisotropic fractal surfaces with the dominating direction of (b) 30° and (c) 120°. (d)–(l) Corresponding rose plots of Hurst coefficients calculated at scales of (d-f) 6, (g-i) 10 and (j-l) 14 pixels using the VOT (asterisk), AVOT (thick line), and QRG (square) methods. Each surface image is 256 × 256 pixels.

For the AVOT and QRG methods θr was set to 0°. The rose plots of Hurst coefficients were obtained and their examples at scales 6, 10, and 14 pixels are shown in Figs. 5(d)–5(l). The shapes of the rose plots indicate correctly the type of surfaces analyzed. For the isotropic surface the plots are approximately of a circular shape (almost the same in all directions) [Figs. 5(d), 5(g), and 5(j)]. The rose plots take an elliptical shape with the major axis aligned along the direction of 30° [Figs. 5(e), 5(h), and 5(k)] and 120° [Figs. 5(f), 5(i), and 5(l)] for the anisotropic surfaces. For the isotropic and anisotropic surfaces, the VOT method produced Hurst coefficients at nine scales (from 6 to 14 pixels) in 24 directions. The AVOT and QRG methods produced the coefficients at more scales, i.e., 11 (from 5 to 15 pixels) and 13 (from 4 to 16 pixels), respectively, and in more directions (i.e., 32).

Texture parameters FSSta, StrS, and StdS were also obtained for the surfaces (Table I). The table shows that the means of FSSta calculated for the isotropic surface are close to FDt = 2.7. Also, StrS values are about two times lower for the anisotropic surfaces than for the isotropic surface. This indicates that the anisotropic surface exhibits large changes in roughness with direction. The StdS parameter took values around 30° and 120° for the anisotropic surfaces; showing correctly the dominating directions.

TABLE I.

Mean ± standard deviation of FSSta, StrS and StdS parameters calculated by the VOT, AVOT, and QRG methods for the isotropic fractal surface with FDt = 2.7 and the anisotropic fractal surfaces with dominating directions of 30° and 120°.

| Anisotropic | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Texture parameter | Method | Isotropic | 30° | 120° |

| VOT | 2.726 ± 0.038 | 2.906 ± 0.013 | 2.922 ± 0.007 | |

| FSSta | AVOT | 2.727 ± 0.045 | 2.917 ± 0.017 | 2.923 ± 0.009 |

| QRG | 2.778 ± 0.064 | 2.916 ± 0.017 | 2.925 ± 0.015 | |

| VOT | 0.885 ± 0.059 | 0.415 ± 0.084 | 0.317 ± 0.084 | |

| StrS | AVOT | 0.865 ± 0.068 | 0.315 ± 0.123 | 0.285 ± 0.119 |

| QRG | 0.872 ± 0.080 | 0.411 ± 0.057 | 0.368 ± 0.074 | |

| VOT | 113.8 ± 17.8 | 29.7 ± 4.9 | 119.4 ± 4.1 | |

| StdS (°) | AVOT | 105.8 ± 38.7 | 30.6 ± 4.9 | 120.2 ± 3.9 |

| QRG | 134.3 ± 40.5 | 30.4 ± 3.1 | 119.2 ± 2.3 | |

II.G. Image databases

For the evaluation of the AVOT and QRG methods, three image databases were constructed. The first two databases contained isotropic and anisotropic computer-generated fractal surfaces of different sizes with known FDs and dominating directions. They were used to evaluate the accuracy in measuring the texture roughness and isotropy/anisotropy. The third database contained TB texture regions of size 20 × 20 pixels selected on subchondral bone on each side of the 5th distal interphalangeal joint on hand radiographs. Using this database, the ability of the methods to detect differences in TB between hands with and without OA was assessed.

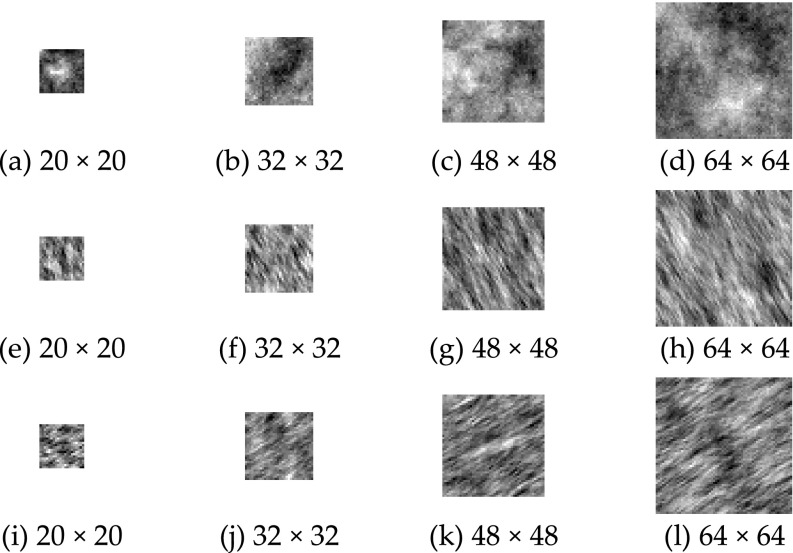

II.G.1. Measurement of surface roughness

Isotropic fractal surfaces with FDt = 2.1, …, 2.9 in steps of 0.1 and in four image sizes, i.e., 20 × 20, 32 × 32, 48 × 48, and 64 × 64 pixels were generated using an interpolation method.29 In total there were 3600 images, i.e., 100 images × 9 values of FDt × 4 image sizes. Examples of the isotropic surfaces which have FDt = 2.7 in four sizes are shown in Figs. 6(a)–6(d).

FIG. 6.

Examples of (a–d) the isotropic and (e–l) anisotropic fractal surface images. The isotropic surfaces has FDt = 2.7. The anisotropic surfaces (e–h) have FDt = 2.6 in 30° and FDt = 2.2 in 120°, and (i–l) have FDt = 2.6 in 120° and FDt = 2.2 in 30°. The dominating directions of surfaces (e–h) and (i–l) are 120° and 30°, respectively. The image sizes are in pixels.

II.G.2. Measurement of surface isotropy and anisotropy

In addition to the isotropic surfaces, two sets of anisotropic fractal surfaces were used. The first set have FDt = 2.6 in 30° and FDt = 2.2 in 120°. For the second set, the fractal dimensions were exchanged with the directions, i.e., FDt = 2.6 in 120° and FDt = 2.2 in 30°. The dominating directions of the surfaces in the sets are 120° and 30°, respectively. For each set and image size, 100 surface images were generated using an inverse Fourier transform method.30 This resulted in 800 anisotropic surface images, i.e., 100 images × 2 sets × 4 image sizes. Examples of anisotropic surfaces from each set are shown in Figs. 6(e)–6(l).

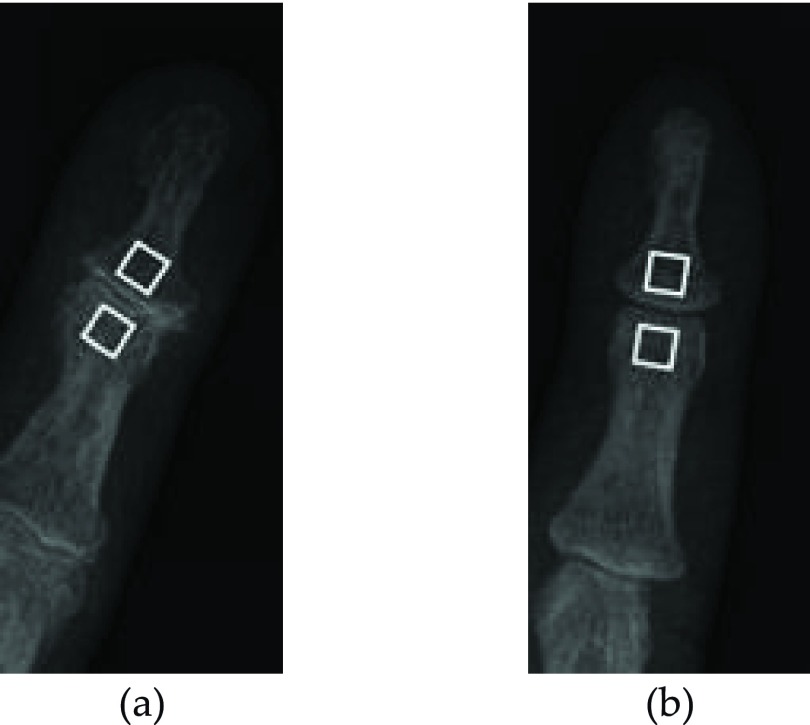

II.G.3. Detection of differences between OA and non-OA hand TB texture images

A matched case-control study design was used to test the DFS methods in the detection of differences in TB texture between subjects with (cases) and without (controls) hand OA. From each subject a posteroanterior radiograph of one hand was used. On each hand, distal interphalangeal (DIP), proximal interphalangeal (PIP), and interphalangeal (IP), and first carpometacarpal (CMC) joints were graded for joint space narrowing (JSN) and osteophytes on a scale from 0 to 3 points. The grading was performed in accordance with the atlas from OA Research Society International (OARSI)4 by a Perth radiologist with over 15 years of experience (Imaging Central, Claremont, Western Australia). A joint was considered as having OA if it exhibited any of the following: (i) JSN grade 2 or worse, (ii) osteophyte grade 2 or worse, or (iii) JSN grade 1 with an osteophyte grade 1. These criteria approximate KL grade 2 or worse.7 Pairs of subjects were taken from the first half of the baseline OAI cohort. They were manually and individually matched by sex, age, body mass index (BMI) and race. OAI is a multicenter prospective observational cohort study with the objective of improving public health through the prevention or alleviation of pain and disability from OA. Versions of clinical and image datasets used were 0.2.2 and 0.C.1, respectively. Cases (n = 20, gender: 14 women, race: 15 white) were subjects with OA in the 5th DIP (DIP5) joint. Controls did not have OA. Mean ± SD values of age and BMI for cases (controls) were 63.0 ± 7.6 (63.0 ± 7.6) and 27.5 ± 4.7 (27.9 ± 4.6), respectively. DIP5 was chosen since this joint is often affected by OA.7 The radiographs for cases and controls were selected from those acquired at clinical centre A. This centre has the smallest size hand radiographs (150 DPI, i.e., pixel resolution of 0.17 mm) amongst the five participating centres in the OAI. Other centres have radiographs with 223 DPI (i.e., pixel resolution of 0.11 mm) and more. The small resolution of the images allows evaluating the methods in “the worst scenario,” i.e., small bone regions of 20 × 20 pixels.

On each hand radiograph, two TB texture ROIs of size of 20 × 20 pixels were manually selected on subchondral bone on 5th distal and proximal phalanges in the following steps:

-

1.

A square of size 20 × 20 pixels with a border parallel to the x-ray image horizontal axis is superimposed on the distal phalanx.

-

2.

The square is rotated, if necessary, around its centre so that its top and bottom borders are parallel to the distal joint surface tangent. The angle of rotation with respect to the x-ray image horizontal axis is stored and later used as a reference direction θr in the AVOT and QRG methods.

-

3.

Position of the rotated square is shifted horizontally or/and vertically to be located immediately above the cortical plate of the distal phalanx in the centre of the bone epiphysis.

-

4.

A new square, with a border parallel to the x-ray image horizontal axis, of size 29 × 29 pixels (i.e., × pixels) is superimposed on the x-ray image. This square is called a bounding square. The rotated and bounding squares are concentric.

-

5.

The x-ray image is cropped to the bounding square and pixels with coordinates outside the rotated square are set to −1.

-

6.

The cropped x-ray image is stored.

For the middle phalanx the ROI selection was similar. The ROIs cover the area of OA bone activities detected in hands using isotope-labelled bone-seeking compounds.6 Mean ± standard deviation of ROIs rotation was 31° ± 7.5°. Examples of ROIs located on OA and non-OA hand radiographs are shown in Fig. 7. Each region has a bone area of 3.4 × 3.4 mm.

FIG. 7.

Examples of TB texture ROIs (white squares) located on subchondral bone on each side of (a) OA and (b) non-OA 5th DIP joints. Each ROI is 20 × 20 pixels.

II.H. Statistical analysis

The following statistical analysis of texture parameters was performed:

-

•

Shapiro-Wilk tests were used to check normality in texture parameters. P < 0.01 was considered significant.

-

•

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tuckey's Honest Significant Difference (HSD), Games-Howell if appropriate, post hoc tests were performed to compare mean values of texture parameters calculated for surfaces with different FDt and dominating directions. If necessary, Kruskal-Wallis tests with Mann-Whitney U-test post hoc tests and Bonferroni adjustments were performed in place of the ANOVA. Levene's tests were used to check homogeneity of variances in texture parameters. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

-

•

Paired samples t-tests (Wilcoxon signed-rank tests if appropriate) were used to compare values of texture parameters calculated for OA and non-OA TB selected in the 5th distal and middle phalanges. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics 21 (IBM Corporation, Somers, NY).

III. RESULTS

III.A. Measurement of surface roughness

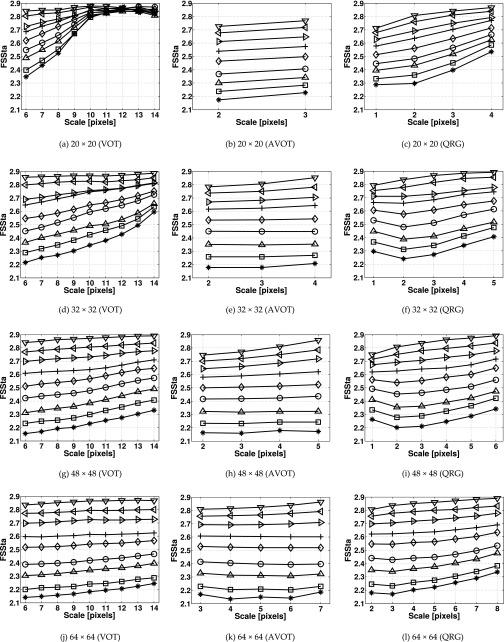

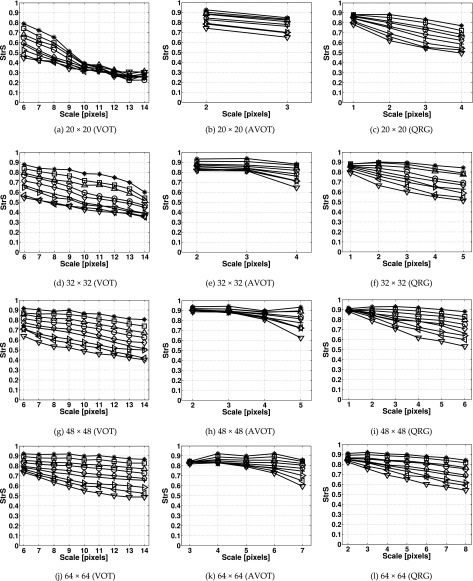

For each FDt and image size, the mean ± SDs values of FSSta were calculated at individual scales, and then, plotted in Fig. 8. The figure shows that at scales 10–14 pixels for 20 × 20 pixel images the mean values of FSSta calculated by the VOT method do not increase monotonically with FDt [Fig. 8(a)] and for 32 × 32 pixel images there is virtually no difference in FSSta between images with FDt = 2.6 and 2.7 [Fig. 8(d)]. In contrast, the AVOT and QRG methods had a monotonic increase with FDt for all image sizes. The AVOT method had the smallest SD values, followed by the QRG and VOT methods. The maximum SDs obtained were 0.149 (VOT), 0.089 (AVOT), and 0.112 (QRG).

FIG. 8.

FSSta calculated for the isotropic fractal surface images of different sizes using the (a, d, g, j) VOT, (b, e, h, k) AVOT, and (c, f, i, l) QRG methods. Markers denote mean values of FSSta calculated for the fractal surfaces with FDt = 2.1 (asterisks), 2.2 (square), 2.3 (upward-pointing triangle), 2.4 (circle), 2.5 (diamond), 2.6 (plus), 2.7 (right-pointing triangle), 2.8 (left-pointing triangle), and 2.9 (downward-pointing triangle). 100 images were used per FDt. The image sizes are in pixels.

For the AVOT method, significant differences (P < 0.05) in FSSta were found between surfaces exhibiting different values of FDt for all image sizes and at all scales. For the VOT method, there were no significant differences at all scales for 20 × 20, at scales 7–14 for 32 × 32, and at scale of 12 pixels for 48 × 48 pixel images. For the QRG method, no differences were found at the two highest scales for images smaller than 48 × 48 pixels.

III.B. Measurement of surface isotropy and anisotropy

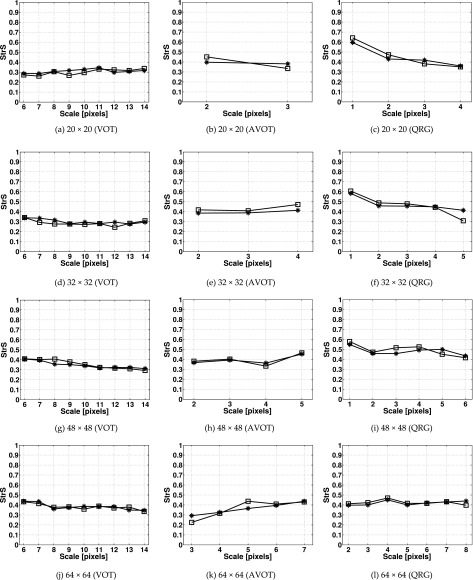

III.B.1. Isotropy

For each FDt and image size, the mean ± SD values of StrS were calculated for the isotropic fractal surfaces and then, plotted against the scales (Fig. 9). The means of StrS calculated by the QRG method took values between those calculated by the VOT and AVOT methods. The VOT and QRG methods yielded higher SDs than the AVOT method. The maximum SDs obtained were 0.205 (VOT), 0.147 (AVOT), and 0.181 (QRG). Statistical differences (P < 0.05) were found in StrS for all isotropic surfaces, expect the VOT method at scales 11–14 pixels for 20 × 20 pixel images.

FIG. 9.

StrS calculated for the isotropic fractal surface images of different sizes using the (a, d, g, j) VOT, (b, e, h, k) AVOT, and (c, f, i, l) QRG methods. Markers denote mean values of StrS calculated for the fractal surfaces with FDt = 2.1 (asterisks), 2.2 (square), 2.3 (upward-pointing triangle), 2.4 (circle), 2.5 (diamond), 2.6 (plus), 2.7 (right-pointing triangle), 2.8 (left-pointing triangle), and 2.9 (downward-pointing triangle). 100 images were used per FDt. The image sizes are in pixels.

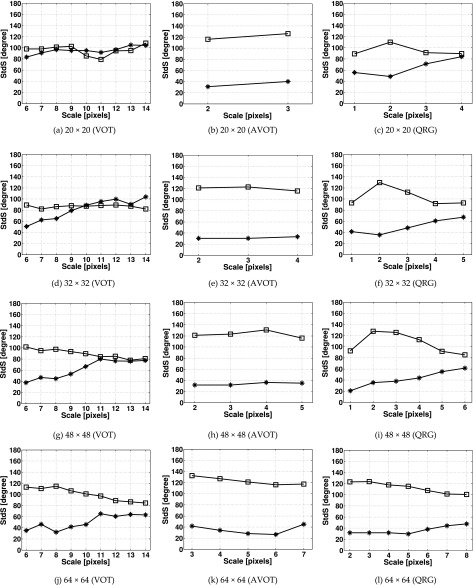

III.B.2. Anisotropy

For each set of anisotropic surfaces the mean values of StrS and StdS are shown in Figs. 10 and 11. The mean values of StrS calculated using the VOT method for 20 × 20 and 32 × 32 images were lower than those obtained using the AVOT and QRG methods [Figs. 10(a) and 10(d)]. For larger images, all methods produced similar results. Figure 11 shows that for all images the values of StdS calculated using the AVOT method were closer to the known directions (i.e., 30° and 120°) than in the other methods. For 20 × 20 pixel images at all scales [Fig. 11(a)], and for 32 × 32 and 48 × 48 pixel images at scales 8–13 and 11–14 pixels [Figs. 11(d) and 11(g)], the StdS calculated using the VOT method virtually did not change with the dominating directions. For the QRG method, this was observed at only 4 pixel scale and for 20 × 20 pixel images [Fig. 11(c)]. The maximum SDs obtained for StrS (StdS) were 0.194 (57°) (VOT), 0.184 (38°) (AVOT), and 0.199 (71°) (QRG).

FIG. 10.

StrS calculated for the anisotropic fractal surface images of different sizes using the (a, d, g, j) VOT, (b, e, h, k) AVOT, and (c, f, i, l) QRG methods. Markers denote mean values of StrS calculated for the fractal images with dominating directions of 30° (asterisk) and 120° (square). 100 images were used per direction. The image sizes are in pixels.

FIG. 11.

StdS calculated for the anisotropic fractal surface images of different sizes using the (a, d, g, j) VOT, (b, e, h, k) AVOT, and (c, f, i, l) QRG methods. Markers denote mean values of StdS calculated for the fractal images with dominating directions of 30° (asterisk) and 120° (square). 100 images were used per direction. The image sizes are in pixels.

For all image sizes and scales, the AVOT method produces statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) in StdS between surfaces with dominating directions of 30° and 120°. Non-significant differences were obtained for the VOT method at all scales for 20 × 20, at scales 10 – 13 pixels for 32 × 32 and at scales 10–14 pixels for 48 × 48 pixel images. For the QRG method, there was non-significant difference at only 4 pixel scale and for 20 × 20 pixel images.

III.C. Detection of differences between OA and non-OA TB texture images

FSSta and StrS were calculated for TB texture ROIs selected on hand radiographs of case and control subjects. Using the AVOT and QRG methods, StdS and FS in the horizontal (FSH) and vertical (FSV) directions, i.e., the directions parallel and perpendicular to top and bottom borders of the ROIs, were also calculated. Trabecular image sizes were: 1.02–2.20 in steps of 0.17 (VOT), 0.34 and 0.51 (AVOT), and 0.17–0.68 mm in steps of 0.17 mm (QRG).

Results obtained showed that the AVOT method detects more statistically significant differences (eight differences; P < 0.044) in texture parameters between cases and controls as compared to the QRG method (seven differences; P < 0.049) (Table II). For the VOT no statistically significant differences were found.

TABLE II.

Mean ± standard deviation (P value) of differences of FSSta, FSV, FSH, StrS parameters between cases and controls in the 5th distal and middle phalanges calculated by the AVOT and QRG methods. Statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) are in bold font.

| Distal phalanx | Middle phalanx | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Texture parameter | Trabecular image size (mm) | AVOT | QRG | AVOT | QRG |

| 0.17 | – | −0.027 ± 0.059 (0.053) | – | −0.023 ± 0.048 (0.049) | |

| FSSta | 0.34 | −0.042 ± 0.088 (0.044) | −0.016 ± 0.012 (0.181) | −0.051 ± 0.089 (0.018) | −0.060 ± 0.080 (0.003) |

| 0.51 | −0.020 ± 0.100 (0.392) | 0.002 ± 0.057 (0.868) | −0.048 ± 0.085 (0.021) | 0.010 ± 0.062 (0.481) | |

| 0.68 | – | 0.000 ± 0.077 (0.982) | – | −0.003 ± 0.086 (0.868) | |

| 0.17 | – | −0.007 ± 0.079 (0.686) | – | −0.026 ± 0.093 (0.234) | |

| FSV | 0.34 | −0.029 ± 0.132 (0.330) | −0.039 ± 0.105 (0.114) | 0.020 ± 0.122 (0.481) | −0.005 ± 0.121 (0.852) |

| 0.51 | −0.041 ± 0.156 (0.225) | 0.015 ± 0.167 (0.688) | 0.076 ± 0.132 (0.019) | 0.130 ± 0.163 (0.002) | |

| 0.68 | – | −0.009 ± 0.208 (0.846) | – | 0.065 ± 0.066 (0.337) | |

| 0.17 | – | −0.025 ± 0.089 (0.231) | – | −0.026 ± 0.076 (0.139) | |

| FSH | 0.34 | −0.054 ± 0.147 (0.118) | −0.010 ± 0.164 (0.792) | −0.068 ± 0.121 (0.022) | −0.135 ± 0.225 (0.015) |

| 0.51 | −0.028 ± 0.192 (0.521) | −0.032 ± 0.218 (0.514) | −0.101 ± 0.156 (0.010) | 0.022 ± 0.201 (0.632) | |

| 0.68 | – | −0.114 ± 0.226 (0.037) | – | −0.047 ± 0.226 (0.362) | |

| 0.17 | – | +0.52 ± 0.103 (0.036) | – | 0.001 ± 0.077 (0.934) | |

| StrS | 0.34 | 0.061 ± 0.190 (0.640) | 0.056 ± 0.184 (0.193) | 0.101 ± 0.169 (0.015) | 0.116 ± 0.246 (0.049) |

| 0.51 | 0.000 ± 0.260 (0.996) | −0.014 ± 0.232 (0.792) | 0.179 ± 0.217 (0.002) | −0.051 ± 0.203 (0.277) | |

| 0.68 | – | 0.009 ± 0.324 (0.907) | – | 0.063 ± 0.282 (0.385) | |

As compared to controls, the distal phalanx bone texture in cases had lower roughness along the dominating roughness and the horizontal directions (AVOT: FSSta at 0.34 mm; QRG: FSH at 0.68 mm) and lower anisotropy (QRG: StrS at 0.17 mm). In the middle phalanx, the lower roughness was also obtained along these two directions [AVOT (QRG): FSSta at 0.34 (0.17) and 0.51 (0.34) mm; FSH at 0.34 (0.34) and 0.51 mm]. In the vertical direction, the bone texture roughness was higher [AVOT (QRG): FSV at 0.51 (0.51) mm]. The anisotropy was lower [AVOT (QRG): StrS at 0.34 (0.34) mm and 0.51] for cases than for controls. For example, using the AVOT method the mean ± SD values of FSSta (FSH, StrS) at size 0.34 mm obtained for control and case subjects in the middle phalanx were 2.691 ± 0.061 (2.670 ± 0.113, 0.657 ± 0.124) and 2.640 ± 0.062 (2.602 ± 0.090, 0.758 ± 0.136). For the QRG method, the mean ± SD values were 2.875 ± 0.041 (2.921 ± 0.172, 0.443 ± 0.175) and 2.815 ± 0.068 (2.786 ± 0.139, 0.559 ± 0.152), respectively.

No significant differences were found for StdS parameter.

IV. DISCUSSION

In this work, two new DFS methods were developed, i.e., the AVOT and QRG methods, for the analysis of TB texture on hand radiographs. Unlike other methods, they can calculate FSs in many directions for small images (i.e., as small as 20 × 20 pixel bone regions) with respect to any chosen reference direction (i.e., they work for any orientation of fingers). For these methods, a special algorithm allowing for the adjustment of the search region was developed. Also, the number of points in the marginal log–log data subsets was reduced, and the directions containing less than four pixels and the ergodic quadrant estimator instead of the line fitting were used for the calculation of the Hurst coefficients.

The accuracy of the newly developed methods in measuring texture roughness was evaluated using small images (ranging from 20 × 20 to 64 × 64 pixels) of isotropic fractal surfaces with nine known FDt. The AVOT method produced FSSta that increased monotonically with FDt and were statistically significantly different between surfaces with different FDt for all image sizes and at all scales. For the QRG and VOT methods, FSSta were not statistically significant at large scales. The reason could be that the methods have less pairs of pixels separated by large distances than those separated by small distances. For example, in case of the VOT method and for 20 × 20 pixel images, there are four times more pairs of pixels in the horizontal direction separated by 4 pixels than those separated by 16 pixels.

The accuracy of the newly developed methods in measuring surface isotropy and anisotropy was also evaluated. For isotropic surfaces, all methods had values of StrS that were less than 1 and were statistically significantly different between FDt. This indicates that FDs calculated change with direction. For ideal isotropic surfaces FD is constant in all directions. The change in FD could be explained by the fact that computer-generated images are discrete samples of continuous fractals and, consequently, they have FDs varying with directions. We found that StrS values were lower for anisotropic surfaces as compared to isotropic surfaces, except StrS at scales 11–14 pixels calculated using the VOT method for 20 × 20 pixel images. For the AVOT method, differences between the isotropic and anisotropic were largest and StdS values calculated were closest to the known dominating directions. For the VOT and QRG method, no differences in StdS values were found at some scales between surfaces with different dominating directions. The results indicate that the AVOT method quantifies correctly changes in the surface isotropy/anisotropy.

We tested the ability of the DFS methods to detect differences in TB texture between OA and non-OA hand radiographs. The highest number of statistically significant differences was found using the AVOT method. Specifically, OA TB textures were less rough in the dominating roughness and horizontal directions (i.e., lower FSSta and FSH, respectively), rougher in the vertical direction (i.e., higher FSV) and more isotropic (i.e., higher StrS) than controls. These differences could reflect on OA changes occurring in bone hands, for example, such as those found in OA knees, e.g., thickening and realignment of trabeculae.20,31 Whether this is the case for hand OA is currently unknown. However, there are on-going studies aiming to understand the relationships between bone structure and OA in hands. For example, a study using microradiographs showed that OA hand joints exhibit greater zone of calcified cartilage than controls which could lead to vascular canals perforation of cortical plate, and subsequently, to bone ischemia and repair.32 In high-resolution magnetic resonance images (MRIs) of OA hands, subchondral bone sclerosis, bone edema, degradation of collateral ligaments and bone central and marginal erosions were found.33,34 Other study showed a positive relationship between hand OA and low bone mineral density.35,36

In our study, the QRG method has the ergodic quadrant estimator. We tested the VOT and AVOT methods with the estimator to check how it affects our results. For the VOT method, values of FSSta were not statistically different between 20 × 20 pixel isotropic fractal surface images with increasing FDt. For the AVOT method, the differences were significant with P < 0.036. When the AVOT method was used with its original line-fitting estimator we get P < 0.001. Results obtained for the dominating directions and the degree of anisotropy were not satisfactory. Also, we tested the QRG method, but with the line-fitting estimator and non-significant differences were found.

The interpolation method applied in our study produces approximate isotropic fractal surfaces. However, we could generate the exact isotropic surfaces using the Stein method.37 Therefore, we checked whether our results would change when the exact method is used (not shown in this work). We found that values of FSSta calculated by the AVOT method were statistically significantly different between surfaces with increasing values of FDt at all scales and for all images sizes. For the VOT and QRG methods, differences were found at some scales and image sizes. For example, for 20 × 20 pixel images, values of FSSta were not different at all scales for the VOT method, and at the last two scales for the QRG method. This agrees with the results obtained for the surfaces generated using the interpolation method. Unlike for the isotropic surfaces, there is no exact method for the generation of anisotropic surfaces.38

Our results suggest that the AVOT method has the potential to be useful in the analysis of hand radiographs for early OA detection and prediction. The method could be also useful in other applications in medicine and in engineering. In medicine, it could be used in the analysis of rheumatoid arthritis and bone mineral density using hand radiographs,14,16 analysis of occlusal forces and detection of osteoporosis using dental radiographs,39,40 detection of lung nodules in chest radiographs,41 or classification of skin lesions on dermoscopic images.42 Also, the method could be extended to work on 3D images such as MRI and used, for example, in the characterisation of brain tumors.43 Possible applications in engineering could be found in determination of the condition status of a mechanical system and prediction of machine failure,44–46 determination of a relationship between surface texture and coefficient of friction,47 and multiscale characterisation of 3D engineering surfaces.48

However, there is a limitation in use of our methods. The reference direction θr needs to be set manually for each ROI analyzed. This could be addressed through the development of an automated selection of ROIs on hand radiographs. For this, further work is warranted.

V. CONCLUSIONS

The following conclusions can be drawn from this study:

-

•

Two new DFS methods were developed, i.e., the AVOT and QRG methods. Unlike other methods, they use the search region adjusted according to image size, and produce FSs defined with respect to any reference direction. These allow for an analysis of hand radiographs with small bone texture regions and arbitrarily oriented fingers.

-

•

The newly developed methods were first evaluated using computer-generated images of isotropic and anisotropic fractal surfaces with known FDs and dominating directions. The image sizes were ranging from 20 × 20 to 64 × 64 pixels. The AVOT method was the most accurate and reliable in measuring the roughness and isotropy/anisotropy of the surfaces.

-

•

The methods were then evaluated on radiographs of OA and non-OA hands. For this purpose, TB texture ROIs were selected on 5th distal and middle phalanges. The AVOT method was most sensitive to OA changes in the hand radiographs.

-

•

We plan to assess the full potential of the AVOT method in the study of bone texture changes in OA hand initiation and progression by prospective, long-term studies on patient groups at high risk of OA development.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported under Australian Research Council's Discovery Early Carrier Research Award funding scheme (Project No. DE130100771). The authors wish to thank Dr. Mark Hamlin from Imaging Central (Claremont, Western Australia) for grading hand radiographs. The authors also wish to thank the Curtin University, Department of Mechanical Engineering and the School of Civil and Mechanical Engineering for their support during preparation of the manuscript. The OAI is a public-private partnership comprised of five contracts (N01-AR-2–2258; N01-AR-2–2259; N01-AR-2–2260; N01-AR-2–2261; N01-AR-2–2262) funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), a branch of the Department of Health and Human Services, and conducted by the OAI Study Investigators. Private funding partners include Merck Research Laboratories; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, GlaxoSmithKline; and Pfizer, Inc. Private sector funding for the OAI is managed by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health. This manuscript was prepared using an OAI public use data set and does not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of the OAI investigators, the NIH, or the private funding partners.

NOMENCLATURE

- Abbreviation

Description

- 2D

Two-dimensional

- 3D

Three-dimensional

- abs

Absolute value function

- AVOT

Augmented variance orientation transform

- ANOVA

One-way analysis of variance

- br

Gray-scale level value in set Bnm

Difference between gray-scale level values

- Bnm

Set of image pixels

- BMI

Body mass index (kg/m2)

- ceil

Ceiling function

- CMC

Carpometacarpal

- dn, dnm

Euclidean distances

- D, D′

Sets of directions

- DFS

Directional fractal signature

- DIP

Distal interphalangeal

- DPI

Dots per inch

- FD

Fractal dimension

- FDt

Theoretical FD

- floor

Floor function

- FS

Fractal signature

- FSH, FSV

Horizontal and vertical FSs

- FSSta

Fractal signature Sta (dominating roughness direction)

- HSD

Honest significant difference

- H

Hurst coefficient

- i, j

Indices of pixel coordinates in image and K

- I

Image function

- IP

Interphalangeal

- JSN

Joint space narrowing

- K

Matrix used to store image pixels

- KL

Kellgren-Lawrence

- Lx, Ly

Spatial domains

- Lxy

Search region

- Lz

Gray-scale level domain

- OA

Osteoarthritis

- OAI

Osteoarthritis Initiative

- OARSI

Osteoarthritis Research Society International

- MLE

Maximum likelihood estimator

- MRI

Magnetic resonance image

- n, m

Indices of directions and distances

- Ng, Nh

Dimensions of a square grid (pixel)

- Nr

Number of gray-scale level values in Bnm

- Nx, Ny

Number of pixels in horizontal and vertical directions

- Nz

Number of gray-scale level values

- Nθ, Nd

Number of directions and pixels

- Ndn

Number of pixels in direction θn

Number of directions in set D′

- P

Set of pixels

- PIP

Proximal interphalangeal

- QRG

Quadrant rotating grid

Set of pixels belonging to directions θn and

- r

Index of pixels belonging to Bnm

- r1, r2

Inner and outer radii of search region (pixel)

- Rw,Rh

Width and height of texture region (pixel)

- R

Set of differences, distances and directions

- RMPS

Recursive multidirectional pixel selection

- ROI

Region of interest

- SD

Standard deviation

- sgn

Sign function

- Sta

Texture minor axis

- Std

Texture direction (°)

- StdS

Texture direction signature (°)

- Str

Texture aspect ratio

- StrS

Texture aspect ratio signature

- T

Statistics of differences of gray-scale level values

- TB

Trabecular bone

- VAR

Variance

- VOT

Variance orientation transform

- x, Δx

Coordinate vectors

- xθ, Δxθ

Coordinate vectors in direction θ

- xi, yj, xnm, ynm

Coordinates of image pixels

- zij

Gray-scale level value of pixel located at (xi, yj)

- ρ

Correlation of normals

- β

Slope of a line

- θ, θn,

Directions in which FDs are calculated (°)

- θr

Reference direction (°)

REFERENCES

- 1. Dziedzic K., “Hand OA: a disease in need of treatment,” Osteoarthritis Cartilage 19(S1), S3 (2011). 10.1016/S1063-4584(11)60015-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dahaghin S., Bierma-Zeinstra S. M. A., Reijman M., Pols H. A. P., Hazes J. M. W., and Koes B. W., “Does hand osteoarthritis predict future hip or knee osteoarthritis?,” Arthritis Rheum. 52, 3520–3527 (2005). 10.1002/art.21375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Englund M., Paradowski P. T., and Lohmander L. S., “Association of radiographic hand osteoarthritis with radiographic knee osteoarthritis after meniscectomy,” Arthritis Rheum. 50, 469–475 (2004). 10.1002/art.20035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Altman R. D. and Gold G. E., “Atlas of individual radiographic features in osteoarthritis, revised,” Osteoarthritis Cartilage 15, A1–A56 (2007). 10.1016/j.joca.2006.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Maheu E., Cadet C., Gueneugues S., Ravaud P., and Dougados M., “Reproducibility and sensitivity to change of four scoring methods for the radiological assessment of osteoarthritis of the hand,” Ann. Rheum. Dis. 66, 464–469 (2007). 10.1136/ard.2006.060277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hutton C. W., Higgs E. R., Jackson P. C., Watt I., and Dieppe P. A., “99mTc HMDP bone scanning in generalised nodal osteoarthritis. II. The four hour bone scan image predicts radiographic change,” Ann. Rheum. Dis. 45, 622–626 (1986). 10.1136/ard.45.8.622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Paradowski P. T., Lohmander L. S., and Englund M., “Natural history of radiographic features of hand osteoarthritis over 10 years,” Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 18, 917–922 (2010). 10.1016/j.joca.2010.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Saltzherr M. S., Selles R. W., Bierma-Zeinstra S. M. A., Muradin G. S. R., Coert J. H., van Neck J. W., and Luime J. J., “Metric properties of advanced imaging methods in osteoarthritis of the hand: a systematic review,” Ann. Rheum. Dis. 73, 365–375 (2014). 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brandt K. D., Radin E. L., Dieppe P. A., and van de Putte L., “Yet more evidence that osteoarthritis is not a cartilage disease,” Ann. Rheum. Dis. 65, 1261–1264 (2006). 10.1136/ard.2006.058347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Buckland-Wright C., “Subchondral bone changes in hand and knee osteoarthritis detected by radiography,” Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 12(Suppl. A), S10–S19 (2004). 10.1016/j.joca.2003.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Baker-Lepain J. C. and Lane N. E., “Role of bone architecture and anatomy in osteoarthritis,” Bone. 51, 197–203 (2012). 10.1016/j.bone.2012.01.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Parkinson I. H. and Fazzalari N. L., “Methodological principles for fractal analysis of trabecular bone,” J. Microsc. 198, 134–142 (2000). 10.1046/j.1365-2818.2000.00684.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pothuaud L., Benhamou C. L., Porion P., Lespessailles E., Harba R., and Levitz P., “Fractal dimension of trabecular bone projection texture is related to three-dimensional microarchitecture,” J. Bone Miner. Res. 15, 691–699 (2000). 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.4.691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Klifa C., Lin J., Augat P., Fuerst T., Jiang Y., Majumdar S., and Genant H. K., “Texture analysis of hand radiographs to assess bone structure,” Proc. SPIE, Med. Imaging 3338, 1096–1105 (1998). 10.1117/12.310836 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fouque-Aubert A., Boutroy S., Marotte H., Vilayphiou N., Lespessailles E., Benhamou C. L., Miossec P., and Chapurlat R., “Assessment of hand trabecular bone texture with high resolution direct digital radiograph in rheumatoid arthritis: A case control study,” Joint Bone Spine 79, 379–383 (2012). 10.1016/j.jbspin.2011.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sparsa L., Kolta S., Briot K., Paternotte S., Masri R., Loeuille D., Geusens P., and Roux C., “Prospective assessment of bone texture parameters at the hand in rheumatoid arthritis,” Joint Bone Spine 80, 499–502 (2013). 10.1016/j.jbspin.2012.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jennane R., Harba R., Lemineur G., Bretteil S., Estrade A., and Benhamou C. L., “Estimation of the 3D self-similarity parameter of trabecular bone from its 2D projection,” Med. Image Anal. 11, 91–98 (2007). 10.1016/j.media.2006.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lynch J. A., Hawkes D. J., and Buckland-Wright J. C., “Analysis of texture in macroradiographs of osteoarthritic knees using the fractal signature,” Phys. Med. Biol. 36, 709–722 (1991). 10.1088/0031-9155/36/6/001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wolski M., Podsiadlo P., and Stachowiak G. W., “Directional fractal signature analysis of trabecular bone: evaluation of different methods to detect early osteoarthritis in knee radiographs,” Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng., Part H 223, 211–236 (2009). 10.1243/09544119JEIM436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wolski M., Podsiadlo P., Stachowiak G. W., Lohmander L. S., and Englund M., “Differences in trabecular bone texture between knees with and without radiographic osteoarthritis detected by directional fractal signature method,” Osteoarthritis Cartilage 18, 684–690 (2010). 10.1016/j.joca.2010.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wolski M., Stachowiak G. W., Dempsey A. R., Mills P. M., Cicuttini F. M., Wang Y., Stoffel K. K., Lloyd D. G., and Podsiadlo P., “Trabecular bone texture detected by plain radiography and variance orientation transform method is different between knees with and without cartilage defects,” J. Orthop. Res. 29, 1161–1167 (2011). 10.1002/jor.21396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Messent E. A., Buckland-Wright J. C., and Blake G. M., “Fractal analysis of trabecular bone in knee osteoarthritis (OA) is a more sensitive marker of disease status than bone mineral density (BMD),” Calcif. Tissue Int. 76, 419–425 (2005). 10.1007/s00223-004-0160-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kraus V. B., Feng S., Wang S., White S., Ainslie M., Brett A., Holmes A., and Charles H. C., “Trabecular morphometry by fractal signature analysis is a novel marker of osteoarthritis progression,” Arthritis Rheum. 60, 3711–3722 (2009). 10.1002/art.25012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pentland A., “Fractal-based description of natural scenes,” IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. PAMI-6, 661–674 (1984). 10.1109/TPAMI.1984.4767591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Veenland J. F., Grashius J. L., van der Meer F., Beckers A. L., and Gelsema E. S., “Estimation of fractal dimension in radiographs,” Med. Phys. 23, 585–594 (1996). 10.1118/1.597816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wolski M., Podsiadlo P., and Stachowiak G. W., “Directional fractal signature analysis of self-structured surface textures,” Tribol. Lett. 47, 323–340 (2012). 10.1007/s11249-012-9988-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Geraets W. G. M., “Comparison of two methods for measuring orientation,” Bone 23, 383–388 (1998). 10.1016/S8756-3282(98)00117-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Storer R. H., Dobric V., and Scansaroli D., “New estimators of the Hurst index for fractional Brownian motion,” Industrial and Systems Engineering Report 11T-004 (Lehigh University, 2010), pp. 1–31.

- 29. Fisher Y., McGuire M., Peitgen H. O., Saupe D., Voss R. F., Barnsley M. F., Devaney R. L., and Mandelbrot B. B., The Science of Fractal Images (Springer-Verlag, New York, 1988). [Google Scholar]

- 30. Russ J. C., Fractal Surfaces (Plenum, New York, 1994). [Google Scholar]

- 31. Messent E. A., Ward R. J., Tonkin C. J., and Buckland-Wright C. J., “Differences in trabecular structure between knees with and without osteoarthritis quantified by macro and standard radiography, respectively,” Osteoarthritis Cartilage 14, 1302–1305 (2006). 10.1016/j.joca.2006.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Buckland-Wright C. and Patel N., “Pattern of advancement in the zone of calcified cartilage detected in hand osteoarthritis,” Osteoarthritis Cartilage 8(Suppl. A), S41–S44 (2000). 10.1053/joca.2000.0336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tan A. L., Grainger A. J., Tanner S. F., Shelley D. M., Pease C., Emery P., and McGonagle D., “High-resolution magnetic resonance imaging for the assessment of hand osteoarthritis,” Arthritis Rheum. 52, 2355–2365 (2005). 10.1002/art.21210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Grainger A. J., Farrant J. M., O’Connor P. J., Tan A. L., Tanner S., Emery P., and McGonagle D., “MR imaging of erosions in interphalangeal joint osteoarthritis: is all osteoarthritis erosive?,” Skeletal Radiol. 36, 737–745 (2007). 10.1007/s00256-007-0287-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. El-Sherif H. E., Kamal R., and Moawyah O., “Hand osteoarthritis and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women: clinical relevance to hand function, pain and disability,” Osteoarthritis Cartilage 16, 12–17 (2008). 10.1016/j.joca.2007.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Haara M. M., Arokoski J. P., Kroger H., Karkkainen A., Manninen P., Knekt P., Impivaara O., and Heliovaara M., “Association of radiological hand osteoarthritis with bone mineral mass: a population study,” Rheumatology (Oxford) 44, 1549–1554 (2005). 10.1093/rheumatology/kei084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Stein M. L., “Fast and exact simulation of fractional Brownian surfaces,” J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 11, 587–599 (2002). 10.1198/106186002466 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bierme H. and Richard F., “Analysis of texture anisotropy based on some gaussian fields with spectral density,” Math. Image Proc. 5, 59–73 (2011). 10.1007/978-3-642-19604-1_3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yasar F. and Akgünlü F., “Fractal dimension and lacunarity analysis of dental radiographs,” Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 34, 261–267 (2005). 10.1259/dmfr/85149245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Law A. N., Bollen A. M., and Chen S. K., “Detecting osteoporosis using dental radiographs: a comparison of four methods,” J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 127, 1734–1742 (1996). 10.14219/jada.archive.1996.0134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schilham A. M. R., van Ginneken B., and Loog M., “A computer-aided diagnosis system for detection of lung nodules in chest radiographs with an evaluation on a public database,” Med. Image Anal. 10, 247–258 (2006). 10.1016/j.media.2005.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Elbaum M., Kopf A. W., Rabinovitz H. S., Langley R. G., Kamino H., Mihm M. C. Jr., Sober A. J., Peck G. L., Bogdan A., Gutkowicz-Krusin D., Greenebaum M., Keem S., Oliviero M., and Wang S., “Automatic differentiation of melanoma from melanocytic nevi with multispectral digital dermoscopy: a feasibility study,” J. Am. Acad. Derm. 44, 207–218 (2001). 10.1067/mjd.2001.110395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mahmoud-Ghoneim D., Toussaint G., Constans J. M., and de Certaines J. D., “Three dimensional texture analysis in MRI: a preliminary evaluation in gliomas,” Magn. Reson. Imaging 21, 983–987 (2003). 10.1016/S0730-725X(03)00201-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Raadnui S., “Wear particle analysis—utilization of quantitative computer image analysis: A review,” Tribol. Int. 38, 871–878 (2005). 10.1016/j.triboint.2005.03.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Stachowiak G. P., Podsiadlo P., and Stachowiak G. W., “Shape and texture features in the automated classification of adhesive and abrasive wear particles,” Tribol. Lett. 24, 15–26 (2006). 10.1007/s11249-006-9117-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Stachowiak G. P., Stachowiak G. W., and Podsiadlo P., “Automated classification of wear particles based on their surface texture and shape features,” Tribol. Int. 41, 34–43 (2008). 10.1016/j.triboint.2007.04.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Menezes P. L., Kishore, and Kailas S. V., “Influence of surface texture and roughness parameters on friction and transfer layer formation during sliding of aluminium pin on steel plate,” Wear 267, 1534–1549 (2009). 10.1016/j.wear.2009.06.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Podsiadlo P. and Stachowiak G. W., “Directional multiscale analysis and optimization for surface textures,” Tribol. Lett. 49, 179–191 (2013). 10.1007/s11249-012-0054-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]