Abstract

A protocol is presented for the calculation of monitor units (MU) for photon and electron beams, delivered with and without beam modifiers, for constant source-surface distance (SSD) and source-axis distance (SAD) setups. This protocol was written by Task Group 71 of the Therapy Physics Committee of the American Association of Physicists in Medicine (AAPM) and has been formally approved by the AAPM for clinical use. The protocol defines the nomenclature for the dosimetric quantities used in these calculations, along with instructions for their determination and measurement. Calculations are made using the dose per MU under normalization conditions, , that is determined for each user's photon and electron beams. For electron beams, the depth of normalization is taken to be the depth of maximum dose along the central axis for the same field incident on a water phantom at the same SSD, where = 1 cGy/MU. For photon beams, this task group recommends that a normalization depth of 10 cm be selected, where an energy-dependent ≤ 1 cGy/MU is required. This recommendation differs from the more common approach of a normalization depth of dm, with = 1 cGy/MU, although both systems are acceptable within the current protocol. For photon beams, the formalism includes the use of blocked fields, physical or dynamic wedges, and (static) multileaf collimation. No formalism is provided for intensity modulated radiation therapy calculations, although some general considerations and a review of current calculation techniques are included. For electron beams, the formalism provides for calculations at the standard and extended SSDs using either an effective SSD or an air-gap correction factor. Example tables and problems are included to illustrate the basic concepts within the presented formalism.

Keywords: monitor unit, dose calculation, photon beams, electron beams

I. INTRODUCTION

On the basis of clinical dose-response data, the International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurement (ICRU) states that dosimetry systems must be capable of delivering dose to an accuracy of 5%.1 Furthermore, improvements in this level of accuracy are warranted to improve the modeling and prediction of dose-volume effects in radiation therapy.2 Many factors contribute to both random and systematic deviations in dose delivery, including daily patient setup, target delineation, and dose calculation. It is apparent that the errors associated with each step of the treatment process must be substantially less than the overall tolerance. Thus, as improvements are made in immobilization techniques, patient setup, and image quality, similar improvements are necessary in dose calculations to obtain greater accuracy in overall dose delivery. The accurate determination of dose per monitor unit (MU) at a single calculation point is an essential part of this process.

The calculation of MUs has evolved over the past several years as treatment planning has increased in accuracy and complexity. Historically, MUs were determined using a manual calculation process, where the calculations were based on water phantom data gathered at time of machine commissioning. Over time, manual calculations have become more accurate due to more detailed characterizations of dosimetric functions. Nevertheless, these calculations are based on machine data, which are typically gathered with a flat, homogeneous water phantom.

Additional improvements in dose-calculation accuracy within computer treatment-planning systems have been made possible with the incorporation of patient-specific anatomical information. Early computer algorithms calculated the two-dimensional scatter characteristics based on patient-specific external contour information.3 The advent of image-based treatment planning has allowed incorporation of patient-specific internal heterogeneity information into the calculation of dose. The use of this information to determine the dose through a complex two- or three-dimensional algorithm is limited to a “computer calculation,” although a subset of this information may be used to improve the accuracy of a manual calculation (e.g., the use of an effective or radiological depth).

Despite the improvements possible with current and future computer-calculated MUs, manual calculations will be still required for several reasons. First, some patients may not require a computerized treatment plan and it may be most efficient to calculate the MU for their treatments manually. This is especially common in the palliative or emergent setting. Second, although the computer calculation may incorporate additional information, there is no assurance that the computer-calculated MUs are more accurate for all conditions. There are a number of different commercial treatment-planning systems available, each of which has a different technique for determining dose. For example, with some computer algorithms, it may be difficult to model a particular clinical setup or accessory. Finally, both Task Group (TG)-40 and TG-114 of the American Association of Physicists in Medicine (AAPM) recommend4,5 that the output of a computer calculation be independently verified with an alternative calculation method. This check becomes more important as the sophistication of the planning algorithm increases.

Many manual methods are currently being used to determine MUs. The use of many different approaches increases the probability of calculational errors, either in the misunderstanding of varying nomenclatures or in the absence or misuse of important parameters within the calculation formalism. Furthermore, using multiple approaches results in reduced clinical workflow efficiency. In addition to the time required for each clinic to develop inhouse MU calculation protocols, the retraining of personnel who move between clinics or the interpretation of clinical data from other clinics is made more difficult when different calculational approaches are used. The clinical application of the formalism presented within is the subject of another AAPM report.5

This task group report presents a consistent formalism for the determination of MUs for photons and electrons. For photons, the report describes MU calculations for fields with and without beam modifiers for both isocentric and source-surface distance (SSD) setups. The protocol includes the use of dynamic or virtual wedges (VW) and static multileaf collimation. Although intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) calculations are beyond the scope of this report, a brief review of current algorithms is made, along with general recommendations of this task group. The current protocol is applicable for megavoltage linear accelerators or Co-60 teletherapy units. For electrons, calculations for standard or irregularly shaped fields at standard or extended SSDs are described.

The protocol's calculations are referenced to , the dose per MU or dose rate of the user's beam under normalization conditions. At the time of calibration, the output of each beam is adjusted to deliver a specific that is determined by the user. Under normalization conditions, although many of the dosimetric functions within this protocol have a value of unity, is not necessarily 1 cGy/MU, and may vary between beams.

Here we differentiate normalization conditions from reference conditions, the latter of which represents the measurement conditions for the determination of absorbed dose to water within the AAPM TG-51 protocol.6 For example, TG-51 specifies that the reference depth, dref, be equal to 10 cm for photon beam calibration. In this report, the photon beam normalization depth, d0, is distinct from but may be equal to dref (10 cm), or to any other depth at or beyond the maximum depth of dm. For electron beams, the normalization depth for a given field is taken to be the depth of maximum dose along the central axis for the same field incident on a water phantom at the same SSD.7,8

The choice of the normalization depth(s) for photon beams should be made after considering several issues. If d0 is different from dref, it is necessary to convert the calibration dose per MU at dref to the dose per MU at d0. This conversion introduces a potential source of error if the percentage depth dose data used for this conversion are inaccurate and/or different from the data used elsewhere in the MU calculation. Additional uncertainty arises if d0 is set equal to dm, where it has been noted that electron contamination within the photon beam makes the determination of dose in this region more difficult.9 Furthermore, other studies have shown that for higher energy beams, electron contamination penetrates much farther than dm.10,11 Choosing d0 = 10 cm for photon beams eliminates the uncertainty associated with converting the calibrated output to the dose rate at other depths, particularly at dm.

Choosing a normalization depth of 10 cm has additional advantages. Different machines of the same energy will be matched at a more clinically relevant depth, which may decrease the differences in programmed MU when moving patients from one machine to another. Some of the field-size dosimetric quantities vary less significantly at depths greater than dm, making dosimetric measurements less susceptible to setup error. Some treatment-planning systems require measured output factors at a depth of 10 cm, thus requiring users to measure these data anyway. Choosing a normalization depth of 10 cm eliminates the duplication of effort, either at time of commissioning or during annual inspections.

Thus, this task group recommends that the normalization depth be set to 10 cm for photon beams. However, the formalism presented within this protocol is valid for any choice of d0. If another depth is chosen for d0, at a minimum this depth shall be greater than or equal to the maximum dm depth, determined from percent depth dose measurements for the smallest field size and greatest SSD used clinically.

It is recognized that a 10-cm normalization depth represents a change for most clinics. To aid the clinician in the development of data tables, we have included a set of example tables which have been normalized at this depth. A set of example problems have also been included in Sec. VIII of this report.

II. CALCULATION FORMALISM

II.A. Photons

MU calculations for photon beams may be performed using either a TPR (isocentric) or PDD (nonisocentric) formalism.

II.A.1. Monitor unit equations

II.A.1.a. Photon calculations using tissue phantom ratio

For calculations using TPR, the equation for MU is given by

| (1) |

In the case where dose is calculated at the isocenter point, Eq. (1) reduces to

| (2) |

II.A.1.b. Photon calculations using percentage depth dose

Although Eq. (1) may be used to determine MUs for any setup, including nonisocentric cases, it may be preferable to use normalized percentage depth doses in some circumstances. In this case, the MU equation is given by

| (3) |

II.A.2. Field-size determination

Many of the dosimetric functions in Eqs. (1)–(3) are field-size dependent due to the variation in scattered radiation originating from the collimator head or the phantom. Dosimetric functions are usually tabulated as a function of square field size. In general, values for irregular fields may be approximated by using the equivalent field size, defined as the square field that has the same depth-dose characteristics as the irregular field.12 In many cases, the treatment-planning system will report the equivalent square of the photon beam. In this case, users should understand the methodology by which this equivalent square is determined, including whether the effects of blocking and/or tissue heterogeneities are included. The equivalent square may also be estimated by approximating the irregular field as a rectangle, and then determining the rectangle's equivalent square either with a calculated table12 or with the method of Sterling et al.,13 which sets the side of the equivalent square to four times the area divided by the perimeter of the rectangular field. This “4A/P” formula works well in most clinical circumstances but should be verified for highly elongated fields (e.g., 5 × 40 cm2) and for in-air output ratios.

This Section (II A 2) describes the determination of field size for use in Eqs. (1)–(3).

II.A.2.a. Determination of field size for Sc

The function Sc models the change in incident fluence as the collimation in the treatment head is varied. The change in incident fluence can be modeled by the collimation of a primary source at the target and a radially symmetric planar extended scattered-radiation source close to the target.14–20 The volumes of these two sources that are not blocked by the jaws and the field shaping collimator (e.g., blocks and MLC) from the point of view of the point of calculation (point's-eye-view or PEV) determine Sc. Because this exposed region from PEV depends on both the jaw settings and the field-shaping collimator that are at different distances from the sources, an accurate formalism will involve a method to combine the effects of different collimators into an equivalent field size. There are three different methods to calculate an equivalent square field size for Sc in order of increasing accuracy: equivalent square of jaw settings, PEV model of collimating jaws, and PEV model of all collimators. Unless the treatment field is highly irregular (e.g., heavily blocked or highly elongated), the equivalent square method predicts Sc reasonably well21 and will be described in this section. A description of the PEV models is included in Appendix B of this report.

Additionally, backscattered radiation from the adjustable jaws to the monitor chamber will affect the collimator scatter factor. Modern accelerators either have a retractable foil between the monitor chamber and the adjustable jaws to attenuate the backscattered radiation, or the collimators are far enough from the monitor chamber so that the significance of monitor backscatter is reduced.21 For further details, the reader is referred to the AAPM TG 74 report.10

II.A.2.ai. Open or externally-blocked fields

The upper and lower jaws are the collimators closest to the target. Thus these collimators are the main factors determining Sc. Although these two sets of collimators are at different distances from the source, the difference in the distances is much smaller than the distance from the source to the isocenter. If one makes the approximation that the upper and lower jaws are at the same distance from the sources and they are the only collimators that are shaping the exposed region of the sources from PEV, the equivalent square for Sc can be modeled as the equivalent square of the rectangle formed by the jaws at isocenter. Using the 4A/P formula, the equivalent square used for determining Sc will be:13

| (4) |

where rjU is the upper jaw setting and rjL is the lower jaw setting, defined at the machine isocenter.

Equation (4) is used to determine the equivalent square for open fields or those using externally mounted blocks. In the latter case, the blocks are placed farther away from the target than the collimators, so that little if any of the source is obscured from the PEV of the calculation point.

The difference in distances from the target of the upper and lower collimator jaws results in deviations from the equivalent square model. The “collimator exchange effect” describes the differences in output when the upper and lower field-size settings are reversed.10 The collimator exchange effect is not modeled using 4A/P; for example, this approximation will predict the same Sc for a 5-cm wide 40-cm long field and a 40-cm wide 5-cm long field. The error introduced by this approximation is typically small (<2%),21 but is dependent on the accelerator design and should be measured for evaluation. The collimator exchange effect is accounted for in the PEV models described in Appendix B.

II.A.2.aii. MLC-blocked fields

Currently, almost all linear accelerators come equipped with some form of multileaf collimator, or MLC. Figures 1–3 show examples of commercially available MLCs categorized as a total or partial replacement of the upper or lower jaws or as tertiary collimation configurations. Because of the different position of each of these configurations with respect to the target, each system will have a different amount of scattered photons reaching the point of calculation for the same incident field size.

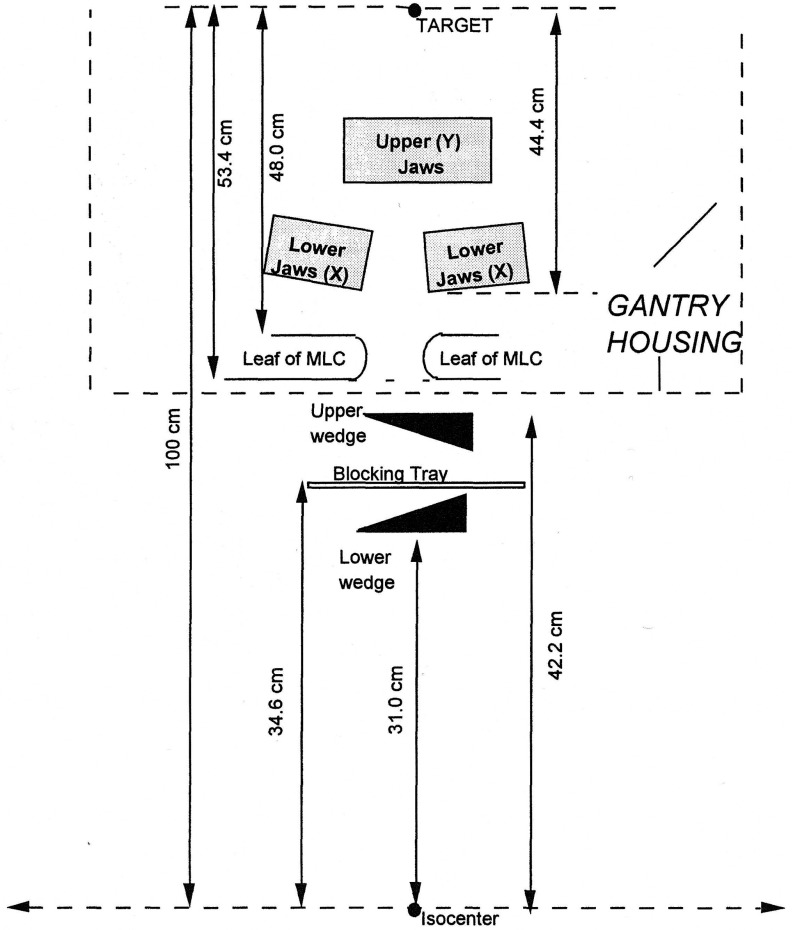

FIG. 1.

Cross-sectional view of Elekta MLC head. The leaf banks are mounted in place of the upper collimator in order to fit in the standard head cover. Each of the 80 tungsten leaves is of 7.5 cm thickness, equivalent to approximately two tenth value layers. A leaf has a width of 1 cm and a range of movement 20 cm away from the central axis to 12.5 cm across it. The 3-cm thick Y back-up diaphragm is intended to reduce any leakage through the gaps between the leaves (Ref. 22).

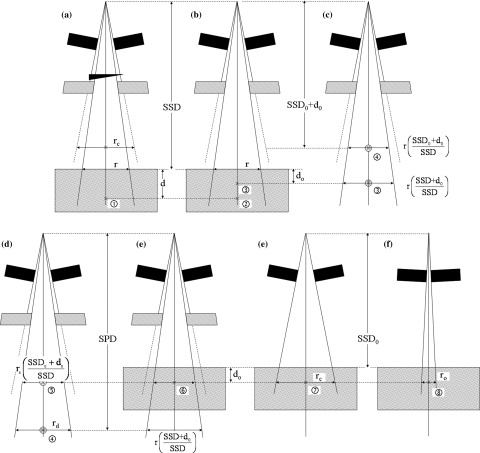

FIG. 2.

Schematic diagram of the Siemens MLC head. In this design, the double-focused bank of 54 leaves is mounted in place of the lower collimator. Each of the tungsten leaves is 7.6-cm thick and projects to a 1.0-cm wide radiation field at isocenter. All leaves can be independently moved to an overtravel of 10 cm past the central axis (Ref. 24).

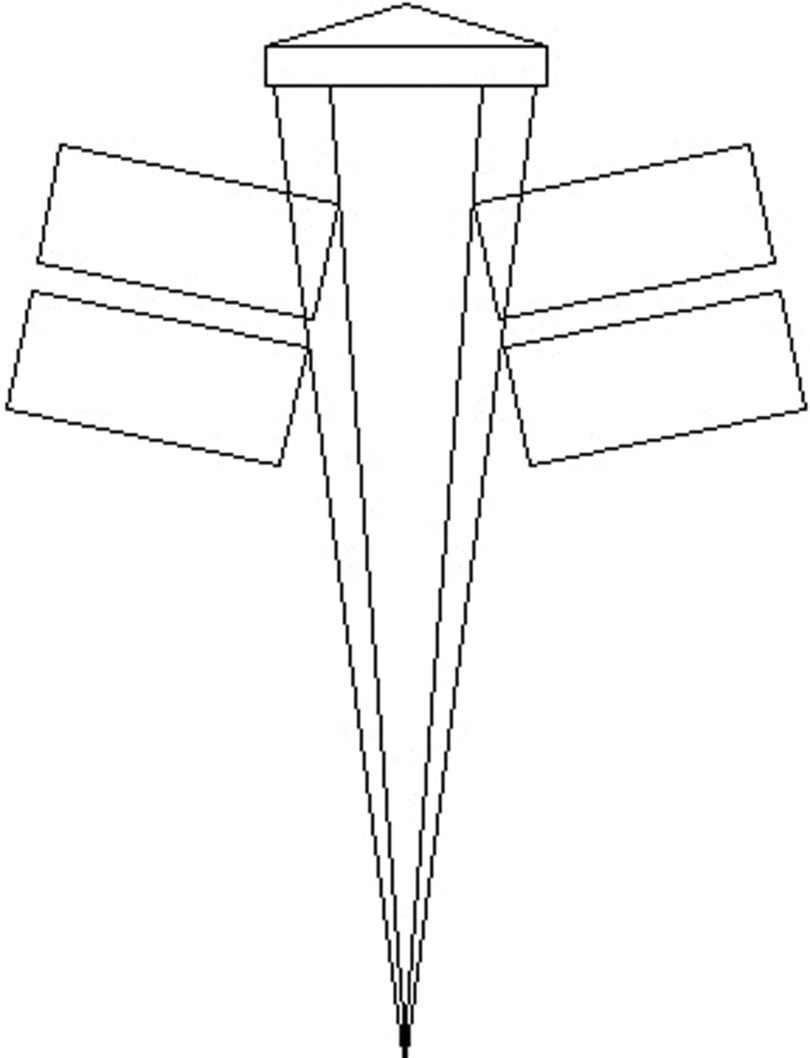

FIG. 3.

Cross-sectional view of Varian MLC head for a 2100C accelerator (Ref. 26). In this design, the leaf banks are mounted in carriages placed below the lower collimator, with leaf widths of 0.5- or 1.0-cm projected at SAD, depending on MLC model.

Currently, the Elekta/Philips MLC is designed as an upper-jaw replacement.22 Backup diaphragms located beneath the leaves augment the attenuation provided by the individual leaves. Figure 1 shows a cross-section of the Elekta head design. Measurements by Palta et al.,23 have demonstrated Sc for the upper-jaw replacement system can be accurately calculated by using the equivalent square of the MLC blocked field area.

The Siemens MLC is designed as a lower-jaw replacement. The upper jaws are strategically placed at the upper and lower borders of the field. Figure 2 displays the Siemens MLC head. Das et al.,24 characterize Sc for the Siemens system in the same fashion as the upper jaw replacement system by using the equivalent square of the MLC blocked field area for the argument of Sc.

The Varian MLC is an example of a tertiary collimator system. This device is positioned just below the level of the standard upper and lower adjustable jaws. The y-jaws are strategically placed at the upper and lower borders of the field. Figure 3 describes the Varian MLC head design. Boyer et al.25 and Klein et al.26 found that the tertiary MLC design is best treated as a block. That is, the equivalent square of the collimator field size is used.

II.A.2.b. Determination of field size for Sp

For Sp, the field size is proportional to that incident on the patient. This may be smaller than the collimator field size if the scatter volume is reduced by either tertiary blocking or patient limits or larger in the case of extended SSD.

The field-size argument rd of Sp in Eqs. (1) and (2) is the equivalent square of the field size incident on the patient, projected to the depth of the point of calculation. Thus, unlike Sc, the argument for Sp will change with a change of source-point distance (SPD).

The field-size argument of Sp in Eq. (3) is the equivalent square of the field size incident on the patient, projected to the normalization depth. In some texts, the argument is written using the field size defined at the patient surface.27 For a normalization depth at or near dm, only a negligible difference is found using the equivalent field size on the surface of the patient. However, for greater d0's (e.g., d0 = 10 cm), this approximation cannot be made. In this case, the projected field size is relatively larger and the field-size dependence of Sp is greater.

II.A.2.c. Determination of field size for TPR or PDDN

As with Sp, the field size argument for these quantities is proportional to that incident on the patient, which will be affected by either tertiary blocking or patient limits.

For isocentric calculations, the field size argument for TPR is the equivalent square of the field size incident on the patient, projected to the depth of the point of calculation. For SSD calculations, the field-size argument for PDDN is the equivalent square of the field size incident on the patient.

II.A.2.d. Determination of field size for wedge factor (WF)

II.A.2.di. Physical wedges

Physical wedges may be classified into two types, distinguished by their placement relative to the secondary collimating jaws. Internal wedges (sometimes called motorized wedges or universal wedges), located above the collimating jaws are designed using a single wedge with a large wedge angle (60°). The internal wedge is inserted into the field using a motorized drive within the accelerator. Wedged isodose distributions with smaller wedge angles are produced by combining the internal wedge field with a corresponding open field with appropriate relative weighting. In contrast, external wedges are placed below the collimating jaws. External wedges are manually inserted into the collimator assembly, and are located much closer to the patient, with source-wedge distances ranging from 40% to 70% of the SAD.

The field size dependency of physical wedges appears to originate from a wedge-induced increase in head scatter.28 Investigations have determined that the WF for rectangular fields is closely approximated by the WF of the equivalent square for both external29,30 and internal31 wedges, regardless of orientation. For wedged fields with blocks or MLCs, it is recommended to use the equivalent square of the irregular field for the argument of WF.32

II.A.2.dii. Nonphysical wedges

Wedge factors for nonphysical, or filterless wedges represent the fractional change in dose per MU at the calculation depth after the treatment field is completed. This protocol will discuss two current vendor implementations of this technology.

The first step by commercial vendors to intensity modulate a beam was the application of the Varian dynamic wedge (DW).33 Both DW and its successor, the enhanced dynamic wedge (EDW) takes advantage of a collimation jaw moving in conjunction with adjustment of the dose rate over the course of one treatment. The variation of jaw position and dose rate is driven by a segmented treatment table (STT), which is unique for each energy, wedge angle, and field size. The basis for the EDW generation is a “golden” STT (GSTT) for a 60°, 30-cm wedge, from which the treatment STTs for other wedge angles are calculated.

In contrast to physical wedges, Varian dynamic wedges have very steep field-size dependencies. Thus, it is critical that the input field size be correct for the calculation. The WF for EDW is primarily dependent on the position of the fixed Y jaw, and is virtually independent of the X collimator setting, the initial moving Y jaw position, and the MLC or blocked field size.

Siemens introduced a dynamic jaw wedging system entitled the VW. The VW operates similar to the Varian EDW, with capabilities for additional intermediate wedge angles and operation with the lower jaws, with limited range.

The most notable difference between the EDW and VW is how the energy fluence pattern is generated. As the VW attempts to deliver the same dose on central axis as the open field with the same field size, the WF is designed to be unity for a standard range of field sizes and wedge angles. The user should verify the field-size dependency (or lack thereof) for all field sizes to be used clinically.

II.A.3. Radiological depth determination

Equations (2) and (3) assume dose is to be delivered to a flat, homogeneous water phantom. To correct for internal heterogeneities within the patient, the calculated homogeneous dose per MU, D′(Homogeneous), is multiplied by a correction factor (CF) defined as

| (5) |

Methods of varying levels of complexity exist in the literature for determining CF.34 Many of these are impractical for application in a manual calculation. Two methods that may be employed are detailed below.

Each of these simple methods relies on attenuation data, typically measured under conditions of electronic equilibrium. Unfortunately, data in nonequilibrium conditions (e.g., d < dm) are suspect and often not even measured. Physicists must use caution with these solutions and not, for example, try to calculation CF in locations near heterogeneity interfaces.

II.A.3.a. Method 1

This method represents the simplest technique for determining the heterogeneity correction factor. It is used in the simplest heterogeneity correction methods that examine only the path of primary radiation.35 Often called the ratio of TAR method, or RTAR, the correction factor uses a water-equivalent or radiological depth, deff, calculated along the line from the source to the point of calculation:

| (6) |

where di and ρe,i are the distance and relative electron density (respectively) for the ith element along the line. For calculations based on CT-based treatment planning, this scaled depth is often reported by the treatment-planning system. In this case, the correction factor is given by

| (7) |

II.A.3.b. Method 2

The method, known as the power law TAR or the Batho method,36 determines the dose for calculation points beneath a heterogeneity. In this method, the correction factor is given by

| (8) |

where ρe is the electron density of the inhomogeneity relative to water and d1 and d2 are the distances from the calculation point to the proximal and distal limits of the heterogeneity. This method has also been extended to cases of multiple heterogeneities.37

II.B. Electrons

The AAPM Task Group 70 (TG70) (Ref. 38) defined the electron output factor, Se, as

| (9) |

where D/MU is the dose per MU (TG70 notation, D′ in this report), dm(ra) is the depth of maximum dose for the treatment field size, ra, and dm(r0) is the depth of maximum dose for the reference field size, r0. As defined above, the output factor includes applicator, insert, and treatment distance effects.

II.B.1. Monitor unit equations

II.B.1.a. Electron calculations at standard SSDs

The equation for MUs for electron beams at the nominal SSD is given by

| (10) |

where the PDD is normalized to the depth of maximum dose for the treatment field size, and Se is the dose output for a field size (combination of applicator and insert) of ra. The percentage depth dose term is included to allow for the common practice of prescribing the dose to a point other than the depth of maximum dose along the central axis. Shiu et al.39 found that the PDD is dependent on the insert size, rather than the applicator size, so we can consider it to be a function of insert size only if needed. In cases where skin collimation is used, the output is primarily determined by the applicator and insert sizes; however, the PDD is primarily determined by the skin collimation field size.7 Therefore, if skin collimation is used, the field size used for the PDD term in Eq. (10) should be the skin collimation field size, rather than the insert and applicator.

II.B.1.b. Electron calculations at extended SSDs

The definition of the output factor includes treatment distance effects; therefore, monitor units can be calculated using Eq. (10) replacing SSD0 with SSD. However, a more common practice is to separate field size effects from treatment distance effects. In other words, the output factor is usually tabulated as a function of applicator and insert size, ra, at the standard SSD. The effect of treatment distance not equal to the standard SSD can be accounted for in two ways, as described in the AAPM Task Group 25 report.7

II.B.1.bi. Effective SSD technique

| (11) |

where g is the difference between the treatment SSD and the calibration SSD, and SSDeff is the effective source to surface distance for the given field size.

II.B.1.bii. Air-gap technique

| (12) |

where g is the difference between the treatment SSD and the calibration SSD, and fair is the air-gap correction factor for the given field size and SSD.

II.B.2. Field-size determination

We follow the AAPM TG70 notation in that ra represents the applicator and insert size for the electron beam under consideration. The vendor-stated applicator size is typically used, which may be defined at either the isocenter or at the applicator base. In this report, the insert size represents the size of the electron field incident on the patient, projected to the isocenter.

For rectangular electron fields, where the insert size is L × W, the square root (geometric mean) method of Mills et al.,40 should be utilized

| (13) |

where the same applicator size for all field sizes is implicit. Shiu et al.,39 found this method to be more accurate than the equivalent square method of Meyer et al.41

It is also recommended that the square root method be used to determine PDD for rectangular fields. Shiu et al.39 found that the square root method determines rectangular field PDD to within 1%. When applying this method, the depths of maximum dose may not be the same for each field size, so a final renormalization of the geometric mean calculation may be required.

There are many methods of determining the output factor for an irregularly shaped electron field. Many centers measure the output for each irregular field, especially if their use is infrequent. If the physicist keeps track of the results, then previously measured data may be used if the energy is the same and the field shape and size are similar.

A second method of determining the dose output is through the use of an analytical algorithm, such as the method described by Khan et al.,42,43 or a Monte Carlo code. An example of the latter is given by Kapur et al.44 These types of systems are not in widespread clinical use, but may become more prevalent in the future. Details of these approaches are also discussed in the AAPM TG 70 report.38

A third method is to approximate the irregular field by a rectangle and then use Eq. (13) to calculate the output of the field. Fundamental principles for determining equivalent rectangles have been provided by Hogstrom et al.:45

-

(a)

The equivalent rectangle for the dose output is determined for the field shape defined by the applicator insert, not by the skin collimator.

-

(b)

The maximum dose output usually occurs in the broadest region of the field, i.e., at the point surrounded by the greatest diameter circle that is enclosed by the field.

-

(c)

The dose output usually varies little beyond some minimum square field size. Hence, areas of the field located greater than one-half of that distance can be assumed to contribute insignificantly to the dose output. [According to Khan et al.42 the minimum radius for lateral scatter equilibrium is . For example, at 9 MeV, areas of the field greater than 2.6 cm from the estimated location for which dose output is being estimated are insignificant].

-

(d)

The rectangle should be constructed to minimize the difference in area between it and the irregular field less any regions ignored. Rotations about the beam central axis should be used.

-

(e)

The method may not be sufficiently accurate to be used for highly irregular fields. In such cases, measurement or other means of calculation are recommended.45

Figure 4 shows a few clinical examples that illustrate how the equivalent rectangular field is estimated.

FIG. 4.

Electron equivalent field sizes. Examples of constructing rectangular fields whose output approximates that of the irregular field for: (a) a posterior cervical strip; (b) a posterior cervical strip plus submandibular nodes; and (c) an internal mammary chain. The irregular field is delineated by the irregularly shaped curve. The beam axes are delineated by orthogonal 10 cm line segments. The constructed rectangle is delineated by the four intersecting lines, the center delineated by “x.” The arcs are a distance 3 cm from the center of the rectangle (Ref. 45).

Corrections for rectangular fields that are centered away from the central axis are rarely needed, especially if beam flatness is well controlled. In cases where such a correction is desired, a multiplicative factor (off-axis ratios; OAR) can be used to account for beam nonuniformity. A major axis scan measured at a depth near dm for each energy-applicator combination should be sufficient to estimate OAR values under most conditions. The radial distance from the central axis should be used, because the scattering foil system is radially symmetric.

In cases where skin collimation is used, although the electron percent depth dose is determined by the skin collimation size,7 the output factor is primarily determined by the applicator and insert sizes.

III. DETERMINATION OF DOSIMETRIC QUANTITIES

In this section, we outline a set of measurements for generating data sufficient to perform calculations according to this protocol. The guidelines for relative dosimetry measurements made in the AAPM TG-70 (Ref. 38) and AAPM TG-106 (Ref. 46) reports should be followed as well.

III.A. Dosimetry equipment

Ionometric measurements are recommended for the majority of measurements described in this protocol. An ionometric dosimeter system for radiation therapy includes one or more ionization chamber assemblies, a measuring assembly (electrometer), one or more phantoms with waterproof sleeves, and one or more stability check devices.47–49

III.A.1. Ionization chambers

Procedures involved in the use of ionization chambers have been described by a number of reports.7,47,48,50–54 At a minimum, the chambers should meet the minimum requirements described for gathering data necessary for commissioning the treatment-planning system. These characteristics include, but are not limited to low leakage (<10 pA), low stem effect (<0.5%), low angular and polarity dependence (<0.5%), and high collection efficiency. Details on chamber construction are available from their respective data sheets provided by vendors. For cylindrical chambers, the chamber cavity volume should be less than 1 cm3. The size is a compromise between the need for sufficient sensitivity and the ability to measure dose at a point. For most field sizes, cylindrical chambers with internal cavity diameter of less than 7 mm and internal cavity length of less than 25 mm meet these requirements.48 For small field measurements (e.g., ⩽3 × 3 cm2), smaller chambers may be required. Users are referred to the upcoming Task Group 155 report on small field dosimetry.55 During measurements the chambers should be aligned in such a way that the radiation fluence is uniform over the cross-section of the air cavity. For the scanning measurements made to determine percent depth dose and/or off-axis profiles, it is important that the chambers be as small as practicable.

Plane-parallel chambers having collection-volume heights and diameters not exceeding 2 mm and 2.0 cm, respectively, can be used for relative dose measurements in both photon and electron beams. Following the recommendation of the AAPM TG-51 protocol, the point of measurement of a cylindrical chamber is taken to lie on the central axis of the cavity at the center of the active volume of the cavity. For a plane-parallel chamber, the point of measurement is at the inner surface of the entrance window, at the center of the window, for all beam qualities and depth. The effective point of measurement for a cylindrical chamber is upstream of the chamber center (i.e., closer to the radiation source) due to the predominantly forward direction of the secondary electrons (because the primary beam enters the chamber at various distances upstream). Plane-parallel chambers may be designed so that the chamber samples the electron fluence incident through the front window, with the contribution of the electrons entering through the side walls being negligible. This design justifies taking the effective point of measurement of the chamber to be at the inner surface of the entrance window, at the center of the window.7,48,54

III.A.2. Phantoms

It is the recommendation of this task group that water be used as the standard phantom material for the dosimetric measurements of all quantities outlined in this report. The size of the phantom must be large enough so that there is at least 5 cm of phantom material beyond each side of the radiation field employed at the depth of measurement and a margin of at least 10 cm beyond the maximum depth of measurement.

In some cases it is necessary to use solid, nonwater phantoms. For example, Sc measurements can be made using a solid mini-phantom that is thick enough (in the beam direction) to eliminate electron contamination and small enough (perpendicular to the beam) to keep the amount of phantom-scattered photons constant for all measured field sizes. Van Gasteren et al.,56 described the use of a mini-phantom that was constructed to best meet these requirements. Ideally, the solid phantom material should be water equivalent, i.e., it should have the same electron density and effective atomic number as water.7 In the event these conditions are not met, it should be verified that the measured values agree with those obtained using water or water equivalent solid mini-phantoms.

III.B. Measurements of dosimetric quantities

In Secs. III B 1 and III B 2, we describe recommended techniques for determining the dependencies (e.g., field size, depth, SSD) of dosimetric parameters required by this protocol. Typically, users will generate tables of dosimetric quantities produced based on measured set of data for the users beam. A set of sample data tables are included at the end of this report.

In general, it is recommended that data be measured such that variation between any two data points is less than 2%. Linear or nearest neighbor interpolation may be used to determine data located between measured results. More advanced interpolation methods may be used as well, provided the results are bounded by the neighboring measured data. Extrapolation of data beyond that measured is not allowed. If the field parameters used for the calculation are outside those tabulated, the output should be directly measured by the user.

Additional guidelines for these measurements may be found in AAPM TG-106 (Ref. 46) and AAPM TG-70 (Ref. 38) reports.

III.B.1. Measurements of dosimetric quantities: Photon beams

In Secs. III B 1 and III B 2, we outline a set of commissioning measurements that may be used to generate the required data for this protocol.

III.B.1.a. Dose per MU under normalization conditions ()

This protocol requires the knowledge of the linear accelerator's dose rate or dose per MU, , under normalization conditions. The normalization conditions are not necessarily equal to the reference conditions under which the linear accelerator is calibrated. For example, although the AAPM TG-51 report6 specifies that the reference depth for photon calibration is 10 cm, data from the RPC indicates that currently over 90% of monitored clinics perform calculations using a normalization dose rate of 1 cGy/MU at a depth of dm. As stated in the Introduction, this difference is acceptable within the current protocol, as long as the normalization depth d0 is at or beyond the maximum depth of dm.

For a given set of normalization conditions, the choice of will be limited to the output range of the linear accelerator. A linear accelerator calibrated to deliver 1 cGy/MU at dm may require to be less than 1 cGy/MU at a normalization depth of 10 cm. For clinics that transition from a normalization depth of dm to 10 cm, it may be preferable to select a value that has a minimal impact on their current linear accelerator output. This selection would minimize the change in calculated MUs for patients currently under treatment. Furthermore, it would allow direct comparison between the old and new MU calculation systems to verify that the new calculation methodology was implemented correctly.

As an example consider the transition from a nonisocentric system that defines to be 1 cGy/MU at 100 cm SSD and a depth of dm, to an isocentric system that defines at 100 cm SAD (isocentric), and a depth of 10 cm. In the nonisocentric system, the dose per MU at the normalization point of the isocentric system is given by TMR(10, 10 × 10) · ((100 + dm)/100)2. This value will change depending on the energy of the photon beam. Table I shows the calculated dose per MU at d0 = 10 cm for a number of different energy photon beams using data taken from British Journal of Radiology Supplement 25.57 In the last column of the table, has been set to this value rounded to the nearest 0.01 cGy/MU, keeping the difference in beam output less than 1%. If users have multiple machines of the same nominal energy, could also be selected to match the average calculated dose per MU of each of these machines.

TABLE I.

Determination of for photon beams using 10-cm normalization depth. For a nonisocentric system with 1 MU defined to deliver 1 cGy at 100 cm SSD and depth = dm, the dose/MU is calculated at the suggested normalization conditions of d = 10 cm, 100 cm SAD, using depth of dm and TMR data taken from Ref. 57. The suggested maintains the definition 1 MU under a new, 10-cm normalization condition.

| Energy | d m | TMR | Dose/MU | Suggested | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (MV) | (cm) | (10, 10×10) | (cGy/MU) | (cGy/MU) | |

| 4 | 1 | 0.738 | 1.020 | 0.753 | 0.750 |

| 5 | 1.25 | 0.759 | 1.025 | 0.778 | 0.780 |

| 6 | 1.5 | 0.786 | 1.030 | 0.810 | 0.810 |

| 8 | 2 | 0.820 | 1.040 | 0.853 | 0.850 |

| 10 | 2.3 | 0.839 | 1.047 | 0.878 | 0.880 |

| 12 | 2.6 | 0.858 | 1.053 | 0.903 | 0.900 |

| 15 | 2.9 | 0.877 | 1.059 | 0.929 | 0.930 |

| 18 | 3.2 | 0.896 | 1.065 | 0.954 | 0.950 |

| 21 | 3.5 | 0.914 | 1.071 | 0.979 | 0.980 |

| 25 | 3.8 | 0.933 | 1.077 | 1.005 | 1.000 |

III.B.1.b. Normalized percent depth dose

The normalized percent depth dose, PDDN, is defined as the percentage ratio of the dose rate at depth to the dose rate at the normalization depth in a water phantom. The definition of PDDN is equivalent to the reference percent depth dose defined in the European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology (ESTRO) report9 and differs from the traditional definition in that the normalization depth is not necessarily at or near dm. PDDN is dependent on depth, SSD, and field size on the phantom surface.

The recommendations of the AAPM TG-51 protocol should be followed for the measurement of depth dose curves for photon beams.6 If a cylindrical or spherical ionization chamber is used, the effective point of measurement of the chamber must be taken into account. This requires that the complete depth ionization curve be shifted to shallower depths (i.e., upstream) by a distance proportional to rcav, where rcav is the radius of the ionization chamber cavity. For photon beams, the shift is taken as 0.6 rcav.48 On the other hand, no shift in depth-ionization curves is needed if well-guarded plane-parallel ionization chambers are used for the measurement of photon- or electron-beam depth-ionization curves.

For photon beams the variation in electron spectra are small past dm, such that the stopping-power ratio between water and air is negligible;58 furthermore, the perturbation effects of the air cavity can be assumed to a reasonable accuracy to be independent of depth for a given beam quality and field size. The depth-ionization curve can thus be treated as depth dose curve for photon beams.

PPDN data should be acquired for a series of field sizes ranging from the smallest to the largest field to be used clinically. If TPRs are to be calculated from PDDN, the minimum measured field size for PDDN must be smaller than the minimum field size tabulated for TPRs. The number of measurements should be sufficient such that PDDN varies by less than 3% between any two measured field sizes. This will require data more closely spaced for smaller field sizes. Sample PDDN data (d0 = 10 cm) for a 6 MV beam are given in Table II.

TABLE II.

Normalized percent depth doses (PDDN) (d0 = 10 cm) for 6-MV x-rays, SSD = 100 cm.

| Field size | 3 × 3 | 4 × 4 | 5 × 5 | 6 × 6 | 7 × 7 | 8 × 8 | 9 × 9 | 10 × 10 | 11 × 11 | 12 × 12 | 13 × 13 | 14 × 14 | 15 × 15 | 16 × 16 | 17 × 17 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depth | |||||||||||||||

| 1.5 | 164.5 | 161.8 | 158.6 | 155.8 | 154.0 | 152.6 | 151.3 | 150.1 | 149.0 | 148.1 | 147.4 | 146.8 | 146.2 | 145.6 | 145.0 |

| 2.0 | 162.0 | 159.3 | 156.6 | 153.7 | 151.8 | 150.5 | 149.2 | 148.1 | 146.9 | 145.9 | 145.2 | 144.7 | 144.2 | 143.6 | 143.0 |

| 2.5 | 157.7 | 155.3 | 152.6 | 150.7 | 148.9 | 147.3 | 146.0 | 144.9 | 143.9 | 143.1 | 142.4 | 141.8 | 141.2 | 140.6 | 140.1 |

| 3.0 | 153.3 | 151.1 | 148.9 | 146.6 | 145.1 | 143.9 | 142.7 | 141.6 | 140.7 | 139.9 | 139.3 | 138.8 | 138.3 | 137.8 | 137.3 |

| 3.5 | 148.6 | 147.0 | 145.1 | 143.1 | 141.8 | 140.7 | 139.5 | 138.4 | 137.5 | 136.8 | 136.3 | 135.9 | 135.5 | 135.0 | 134.5 |

| 4.0 | 144.6 | 142.9 | 141.5 | 139.3 | 138.0 | 137.2 | 136.3 | 135.4 | 134.7 | 134.0 | 133.5 | 133.0 | 132.6 | 132.2 | 131.8 |

| 4.5 | 140.4 | 139.0 | 137.7 | 135.9 | 134.8 | 134.0 | 133.1 | 132.3 | 131.7 | 131.1 | 130.6 | 130.2 | 129.8 | 129.4 | 129.0 |

| 5.0 | 136.4 | 135.3 | 134.0 | 132.5 | 131.5 | 130.7 | 130.0 | 129.3 | 128.7 | 128.2 | 127.8 | 127.5 | 127.2 | 126.8 | 126.4 |

| 5.5 | 132.2 | 131.5 | 130.3 | 129.0 | 128.2 | 127.6 | 126.9 | 126.3 | 125.7 | 125.1 | 124.8 | 124.5 | 124.3 | 124.0 | 123.6 |

| 6.0 | 128.3 | 127.7 | 126.6 | 125.5 | 124.9 | 124.4 | 123.8 | 123.2 | 122.7 | 122.3 | 122.0 | 121.8 | 121.6 | 121.3 | 121.0 |

| 6.5 | 124.4 | 124.0 | 123.1 | 122.1 | 121.6 | 121.3 | 120.6 | 120.0 | 119.6 | 119.3 | 119.1 | 118.9 | 118.8 | 118.6 | 118.3 |

| 7.0 | 120.5 | 120.3 | 119.3 | 118.7 | 118.3 | 118.0 | 117.5 | 117.0 | 116.7 | 116.5 | 116.2 | 116.0 | 115.7 | 115.5 | 115.3 |

| 7.5 | 116.8 | 116.8 | 115.8 | 115.3 | 114.9 | 114.5 | 114.2 | 113.9 | 113.7 | 113.5 | 113.3 | 113.2 | 113.0 | 112.9 | 112.7 |

| 8.0 | 113.4 | 113.2 | 112.5 | 112.1 | 111.8 | 111.6 | 111.2 | 110.9 | 110.7 | 110.5 | 110.4 | 110.3 | 110.3 | 110.2 | 110.1 |

| 8.5 | 109.6 | 110.0 | 109.1 | 108.9 | 108.8 | 108.7 | 108.4 | 108.0 | 107.9 | 107.8 | 107.8 | 107.7 | 107.7 | 107.6 | 107.5 |

| 9.0 | 106.1 | 106.6 | 106.0 | 105.8 | 105.7 | 105.7 | 105.5 | 105.3 | 105.3 | 105.3 | 105.2 | 105.2 | 105.1 | 105.1 | 105.0 |

| 9.5 | 102.9 | 103.2 | 102.7 | 102.9 | 102.9 | 102.8 | 102.6 | 102.5 | 102.5 | 102.6 | 102.6 | 102.5 | 102.5 | 102.5 | 102.5 |

| 10.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| 10.5 | 96.9 | 97.2 | 97.0 | 97.2 | 97.3 | 97.4 | 97.4 | 97.4 | 97.5 | 97.6 | 97.7 | 97.7 | 97.7 | 97.7 | 97.7 |

| 11.0 | 94.0 | 94.4 | 94.2 | 94.4 | 94.6 | 94.7 | 94.8 | 94.8 | 94.8 | 94.9 | 95.0 | 95.2 | 95.3 | 95.4 | 95.4 |

| 11.5 | 91.1 | 91.6 | 91.5 | 91.7 | 91.9 | 92.1 | 92.2 | 92.3 | 92.4 | 92.6 | 92.7 | 92.8 | 92.9 | 93.0 | 93.0 |

| 12.0 | 88.4 | 88.9 | 88.7 | 89.0 | 89.2 | 89.4 | 89.6 | 89.8 | 90.0 | 90.2 | 90.4 | 90.5 | 90.6 | 90.7 | 90.7 |

| 12.5 | 85.5 | 86.0 | 85.9 | 86.3 | 86.6 | 86.9 | 87.0 | 87.2 | 87.5 | 87.8 | 87.9 | 88.0 | 88.0 | 88.1 | 88.3 |

| 13.0 | 83.4 | 83.3 | 83.3 | 83.7 | 84.1 | 84.4 | 84.5 | 84.7 | 85.0 | 85.4 | 85.6 | 85.7 | 85.8 | 85.9 | 86.1 |

| 13.5 | 80.4 | 80.8 | 80.7 | 81.3 | 81.8 | 82.1 | 82.3 | 82.5 | 82.8 | 83.1 | 83.3 | 83.5 | 83.7 | 83.9 | 84.0 |

| 14.0 | 77.8 | 78.5 | 78.4 | 79.0 | 79.5 | 79.8 | 79.9 | 80.1 | 80.5 | 80.9 | 81.2 | 81.5 | 81.7 | 81.9 | 82.0 |

| 14.5 | 75.4 | 76.1 | 76.2 | 76.7 | 77.1 | 77.5 | 77.8 | 78.1 | 78.5 | 78.9 | 79.2 | 79.5 | 79.7 | 79.9 | 80.0 |

| 15.0 | 73.3 | 73.8 | 74.0 | 74.5 | 75.0 | 75.4 | 75.6 | 75.9 | 76.3 | 76.8 | 77.1 | 77.4 | 77.6 | 77.8 | 78.0 |

| 16.0 | 69.1 | 69.7 | 69.8 | 70.6 | 71.1 | 71.4 | 71.6 | 71.9 | 72.4 | 72.9 | 73.2 | 73.4 | 73.6 | 73.9 | 74.1 |

| 17.0 | 64.9 | 65.5 | 65.7 | 66.4 | 67.0 | 67.5 | 67.8 | 68.0 | 68.5 | 69.0 | 69.3 | 69.6 | 69.9 | 70.2 | 70.4 |

| 18.0 | 61.1 | 61.6 | 61.8 | 62.6 | 63.2 | 63.6 | 63.9 | 64.2 | 64.8 | 65.4 | 65.8 | 66.1 | 66.3 | 66.6 | 66.8 |

| 19.0 | 57.5 | 58.1 | 58.2 | 59.0 | 59.5 | 59.9 | 60.3 | 60.8 | 61.4 | 61.9 | 62.3 | 62.6 | 62.9 | 63.2 | 63.5 |

| 20.0 | 54.1 | 54.8 | 55.0 | 55.8 | 56.4 | 56.9 | 57.2 | 57.6 | 58.2 | 58.8 | 59.1 | 59.4 | 59.6 | 59.9 | 60.2 |

| 21.0 | 51.2 | 51.6 | 51.9 | 52.8 | 53.4 | 53.9 | 54.2 | 54.5 | 55.0 | 55.6 | 56.0 | 56.4 | 56.7 | 57.0 | 57.3 |

| 22.0 | 48.2 | 48.7 | 48.8 | 49.9 | 50.5 | 50.9 | 51.2 | 51.5 | 52.2 | 52.9 | 53.3 | 53.5 | 53.7 | 54.0 | 54.2 |

| 23.0 | 45.4 | 46.1 | 46.0 | 46.9 | 47.6 | 48.2 | 48.4 | 48.6 | 49.3 | 50.0 | 50.4 | 50.7 | 50.9 | 51.2 | 51.5 |

| 24.0 | 42.8 | 43.5 | 43.4 | 44.2 | 44.9 | 45.4 | 45.7 | 46.0 | 46.6 | 47.3 | 47.7 | 48.0 | 48.2 | 48.5 | 48.8 |

| 25.0 | 40.3 | 41.1 | 41.0 | 42.0 | 42.6 | 43.0 | 43.2 | 43.5 | 44.2 | 44.9 | 45.3 | 45.6 | 45.8 | 46.1 | 46.4 |

| Field size | 18 × 18 | 19 × 19 | 20 × 20 | 21 × 21 | 22 × 22 | 24 × 24 | 26 × 26 | 28 × 28 | 30 × 30 | 32 × 32 | 34 × 34 | 36 × 36 | 38 × 38 | 40 × 40 | |

| Depth | |||||||||||||||

| 1.5 | 144.4 | 143.9 | 143.4 | 143.0 | 142.5 | 141.8 | 141.2 | 140.8 | 140.4 | 140.0 | 139.6 | 139.3 | 139.0 | 138.7 | |

| 2.0 | 142.4 | 141.8 | 141.3 | 140.8 | 140.4 | 139.7 | 139.2 | 138.8 | 138.5 | 138.1 | 137.8 | 137.5 | 137.1 | 136.8 | |

| 2.5 | 139.6 | 139.1 | 138.7 | 138.3 | 137.8 | 137.1 | 136.6 | 136.3 | 136.0 | 135.7 | 135.4 | 135.1 | 134.8 | 134.5 | |

| 3.0 | 136.9 | 136.4 | 136.0 | 135.6 | 135.2 | 134.6 | 134.1 | 133.6 | 133.3 | 133.0 | 132.7 | 132.5 | 132.3 | 132.1 | |

| 3.5 | 134.1 | 133.6 | 133.2 | 132.8 | 132.5 | 131.9 | 131.5 | 131.2 | 130.9 | 130.6 | 130.4 | 130.1 | 129.9 | 129.7 | |

| 4.0 | 131.4 | 131.0 | 130.7 | 130.4 | 130.1 | 129.5 | 129.1 | 128.8 | 128.5 | 128.2 | 128.0 | 127.8 | 127.6 | 127.5 | |

| 4.5 | 128.7 | 128.3 | 128.0 | 127.7 | 127.4 | 126.9 | 126.6 | 126.3 | 126.1 | 125.9 | 125.6 | 125.4 | 125.2 | 125.0 | |

| 5.0 | 126.1 | 125.7 | 125.4 | 125.1 | 124.9 | 124.5 | 124.2 | 124.0 | 123.8 | 123.6 | 123.4 | 123.1 | 122.9 | 122.6 | |

| 5.5 | 123.3 | 123.0 | 122.7 | 122.5 | 122.3 | 122.0 | 121.7 | 121.5 | 121.2 | 121.0 | 120.8 | 120.6 | 120.5 | 120.4 | |

| 6.0 | 120.8 | 120.5 | 120.2 | 120.0 | 119.7 | 119.4 | 119.1 | 118.9 | 118.8 | 118.6 | 118.5 | 118.3 | 118.2 | 118.0 | |

| 6.5 | 118.1 | 117.8 | 117.6 | 117.4 | 117.2 | 116.9 | 116.7 | 116.5 | 116.3 | 116.1 | 116.0 | 115.9 | 115.8 | 115.7 | |

| 7.0 | 115.2 | 115.0 | 114.9 | 114.8 | 114.6 | 114.4 | 114.2 | 114.1 | 114.0 | 113.9 | 113.8 | 113.6 | 113.5 | 113.4 | |

| 7.5 | 112.6 | 112.4 | 112.3 | 112.1 | 112.0 | 111.7 | 111.5 | 111.4 | 111.3 | 111.2 | 111.1 | 111.1 | 111.0 | 111.0 | |

| 8.0 | 109.9 | 109.8 | 109.7 | 109.6 | 109.5 | 109.4 | 109.2 | 109.0 | 108.8 | 108.7 | 108.6 | 108.6 | 108.6 | 108.7 | |

| 8.5 | 107.4 | 107.2 | 107.1 | 107.0 | 107.0 | 106.8 | 106.8 | 106.7 | 106.6 | 106.5 | 106.5 | 106.4 | 106.4 | 106.4 | |

| 9.0 | 105.0 | 104.9 | 104.9 | 104.8 | 104.7 | 104.6 | 104.5 | 104.4 | 104.4 | 104.4 | 104.3 | 104.3 | 104.2 | 104.2 | |

| 9.5 | 102.4 | 102.4 | 102.4 | 102.4 | 102.3 | 102.2 | 102.2 | 102.2 | 102.3 | 102.3 | 102.3 | 102.2 | 102.2 | 102.1 | |

| 10.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

| 10.5 | 97.7 | 97.7 | 97.7 | 97.7 | 97.7 | 97.7 | 97.7 | 97.8 | 97.8 | 97.8 | 97.9 | 97.9 | 98.0 | 98.0 | |

| 11.0 | 95.5 | 95.5 | 95.5 | 95.5 | 95.5 | 95.5 | 95.5 | 95.6 | 95.7 | 95.8 | 95.8 | 95.8 | 95.8 | 95.8 | |

| 11.5 | 93.1 | 93.1 | 93.2 | 93.3 | 93.3 | 93.5 | 93.5 | 93.5 | 93.5 | 93.5 | 93.6 | 93.6 | 93.7 | 93.8 | |

| 12.0 | 90.7 | 90.8 | 90.8 | 90.9 | 91.0 | 91.2 | 91.3 | 91.3 | 91.3 | 91.3 | 91.4 | 91.4 | 91.5 | 91.6 | |

| 12.5 | 88.4 | 88.5 | 88.7 | 88.8 | 88.9 | 89.1 | 89.2 | 89.3 | 89.3 | 89.3 | 89.4 | 89.5 | 89.5 | 89.6 | |

| 13.0 | 86.2 | 86.3 | 86.4 | 86.5 | 86.6 | 86.8 | 87.0 | 87.1 | 87.2 | 87.3 | 87.4 | 87.5 | 87.5 | 87.6 | |

| 13.5 | 84.1 | 84.3 | 84.4 | 84.6 | 84.7 | 85.0 | 85.1 | 85.2 | 85.2 | 85.3 | 85.4 | 85.5 | 85.6 | 85.7 | |

| 14.0 | 82.2 | 82.3 | 82.4 | 82.5 | 82.6 | 82.8 | 83.0 | 83.2 | 83.3 | 83.4 | 83.6 | 83.7 | 83.8 | 83.9 | |

| 14.5 | 80.2 | 80.3 | 80.4 | 80.5 | 80.7 | 80.9 | 81.1 | 81.2 | 81.3 | 81.4 | 81.6 | 81.7 | 81.8 | 82.0 | |

| 15.0 | 78.2 | 78.3 | 78.5 | 78.7 | 78.8 | 79.1 | 79.3 | 79.5 | 79.6 | 79.7 | 79.9 | 80.0 | 80.1 | 80.2 | |

| 16.0 | 74.3 | 74.6 | 74.8 | 75.0 | 75.2 | 75.6 | 75.8 | 75.9 | 76.0 | 76.1 | 76.3 | 76.4 | 76.6 | 76.8 | |

| 17.0 | 70.7 | 70.9 | 71.1 | 71.3 | 71.6 | 71.9 | 72.2 | 72.3 | 72.4 | 72.5 | 72.7 | 72.8 | 73.0 | 73.2 | |

| 18.0 | 67.0 | 67.3 | 67.5 | 67.8 | 68.0 | 68.4 | 68.7 | 68.9 | 69.0 | 69.2 | 69.3 | 69.5 | 69.7 | 69.9 | |

| 19.0 | 63.7 | 64.0 | 64.2 | 64.5 | 64.7 | 65.1 | 65.4 | 65.6 | 65.8 | 66.0 | 66.2 | 66.4 | 66.6 | 66.8 | |

| 20.0 | 60.5 | 60.8 | 61.1 | 61.4 | 61.6 | 62.1 | 62.4 | 62.7 | 62.9 | 63.1 | 63.3 | 63.5 | 63.7 | 63.8 | |

| 21.0 | 57.5 | 57.8 | 58.0 | 58.3 | 58.6 | 59.2 | 59.5 | 59.8 | 59.9 | 60.1 | 60.3 | 60.5 | 60.7 | 60.9 | |

| 22.0 | 54.5 | 54.8 | 55.1 | 55.4 | 55.8 | 56.3 | 56.7 | 56.9 | 57.0 | 57.2 | 57.4 | 57.6 | 57.8 | 58.1 | |

| 23.0 | 51.7 | 52.0 | 52.3 | 52.6 | 53.0 | 53.5 | 53.9 | 54.1 | 54.2 | 54.4 | 54.6 | 54.9 | 55.1 | 55.4 | |

| 24.0 | 49.1 | 49.4 | 49.7 | 50.0 | 50.4 | 50.9 | 51.3 | 51.5 | 51.6 | 51.8 | 52.0 | 52.2 | 52.4 | 52.7 | |

| 25.0 | 46.7 | 47.0 | 47.3 | 47.7 | 48.0 | 48.6 | 49.0 | 49.1 | 49.2 | 49.4 | 49.6 | 49.8 | 50.1 | 50.4 | |

One could calculate PDDN at different SSDs assuming that the TPR is independent of the source to point distance.

Substituting fi(d) ≡ (SSDi + d)/SSDi, the following relationship holds:

| (14) |

where F is the Mayneord F factor59 given by

| (15) |

Although the magnitude of the term in the brackets in Eq. (14) increases with depth,60 it is typically small (e.g., <0.5%) for all practical clinical setups and can usually be ignored.

III.B.1.c. Tissue phantom ratios

The TPR is defined as the ratio of the dose rate at a given point in a water phantom to the dose rate at the same point at the normalization depth. TPRs can be measured directly, but may also be calculated using the following equation:

| (16) |

TPR is dependent on both the depth and field size at the depth of measurement. If a reference depth is not beyond the range of electron contamination, then TPR may also vary with SSD. If Eq. (16) is used to compute TPRs, spot-check measurements should be made to confirm agreement. In regions of electronic disequilibrium, Eq. (16) is only approximate,60 although differences between measured and calculated values are small.

Table III gives sample TPR data (d0 = 10 cm) for a 6 MV photon beam, calculated using Eq. (16), and the data from Tables II and IV.

TABLE III.

Tissue phantom ratios (TPRs) for 6-MV photons (d0 = 10 cm).

| Field size | 4 × 4 | 5 × 5 | 6 × 6 | 7 × 7 | 8 × 8 | 9 × 9 | 10 × 10 | 11 × 11 | 12 × 12 | 13 × 13 | 14 × 14 | 15 × 15 | 16 × 16 | 17 × 17 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depth | ||||||||||||||

| 1.5 | 1.390 | 1.364 | 1.340 | 1.323 | 1.313 | 1.302 | 1.291 | 1.281 | 1.273 | 1.267 | 1.261 | 1.256 | 1.251 | 1.246 |

| 2.0 | 1.381 | 1.360 | 1.336 | 1.317 | 1.307 | 1.296 | 1.286 | 1.275 | 1.267 | 1.260 | 1.255 | 1.251 | 1.246 | 1.241 |

| 2.5 | 1.360 | 1.338 | 1.321 | 1.305 | 1.292 | 1.281 | 1.270 | 1.261 | 1.254 | 1.247 | 1.241 | 1.237 | 1.232 | 1.228 |

| 3.0 | 1.335 | 1.318 | 1.298 | 1.283 | 1.273 | 1.263 | 1.253 | 1.244 | 1.238 | 1.232 | 1.227 | 1.223 | 1.219 | 1.214 |

| 3.5 | 1.311 | 1.296 | 1.279 | 1.266 | 1.257 | 1.247 | 1.237 | 1.228 | 1.221 | 1.216 | 1.212 | 1.209 | 1.205 | 1.201 |

| 4.0 | 1.286 | 1.275 | 1.258 | 1.244 | 1.236 | 1.229 | 1.221 | 1.213 | 1.208 | 1.202 | 1.198 | 1.194 | 1.191 | 1.187 |

| 4.5 | 1.263 | 1.252 | 1.238 | 1.226 | 1.219 | 1.212 | 1.204 | 1.197 | 1.192 | 1.188 | 1.183 | 1.180 | 1.177 | 1.173 |

| 5.0 | 1.240 | 1.230 | 1.217 | 1.207 | 1.200 | 1.193 | 1.187 | 1.181 | 1.177 | 1.172 | 1.169 | 1.167 | 1.164 | 1.161 |

| 5.5 | 1.216 | 1.207 | 1.196 | 1.187 | 1.181 | 1.176 | 1.170 | 1.164 | 1.159 | 1.155 | 1.152 | 1.150 | 1.148 | 1.145 |

| 6.0 | 1.192 | 1.183 | 1.174 | 1.166 | 1.162 | 1.157 | 1.152 | 1.147 | 1.143 | 1.139 | 1.137 | 1.135 | 1.133 | 1.131 |

| 6.5 | 1.167 | 1.161 | 1.152 | 1.146 | 1.143 | 1.139 | 1.133 | 1.127 | 1.124 | 1.122 | 1.120 | 1.119 | 1.117 | 1.115 |

| 7.0 | 1.142 | 1.135 | 1.129 | 1.125 | 1.122 | 1.118 | 1.114 | 1.110 | 1.107 | 1.105 | 1.103 | 1.100 | 1.098 | 1.096 |

| 7.5 | 1.119 | 1.112 | 1.106 | 1.102 | 1.098 | 1.095 | 1.092 | 1.090 | 1.088 | 1.086 | 1.085 | 1.083 | 1.082 | 1.081 |

| 8.0 | 1.094 | 1.089 | 1.084 | 1.082 | 1.079 | 1.077 | 1.074 | 1.071 | 1.069 | 1.067 | 1.066 | 1.066 | 1.065 | 1.065 |

| 8.5 | 1.072 | 1.067 | 1.062 | 1.061 | 1.060 | 1.058 | 1.055 | 1.052 | 1.051 | 1.050 | 1.050 | 1.050 | 1.049 | 1.049 |

| 9.0 | 1.047 | 1.045 | 1.041 | 1.040 | 1.039 | 1.038 | 1.037 | 1.035 | 1.035 | 1.035 | 1.034 | 1.034 | 1.033 | 1.033 |

| 9.5 | 1.023 | 1.020 | 1.019 | 1.020 | 1.020 | 1.019 | 1.017 | 1.016 | 1.017 | 1.017 | 1.017 | 1.017 | 1.016 | 1.016 |

| 10.0 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| 10.5 | 0.980 | 0.979 | 0.979 | 0.981 | 0.982 | 0.982 | 0.982 | 0.982 | 0.983 | 0.984 | 0.985 | 0.985 | 0.985 | 0.985 |

| 11.0 | 0.960 | 0.959 | 0.959 | 0.961 | 0.962 | 0.963 | 0.964 | 0.964 | 0.965 | 0.965 | 0.966 | 0.967 | 0.969 | 0.970 |

| 11.5 | 0.939 | 0.940 | 0.939 | 0.941 | 0.943 | 0.945 | 0.946 | 0.947 | 0.948 | 0.950 | 0.951 | 0.952 | 0.953 | 0.953 |

| 12.0 | 0.919 | 0.919 | 0.918 | 0.921 | 0.923 | 0.925 | 0.927 | 0.929 | 0.931 | 0.933 | 0.934 | 0.936 | 0.937 | 0.938 |

| 12.5 | 0.896 | 0.897 | 0.897 | 0.901 | 0.904 | 0.906 | 0.908 | 0.909 | 0.912 | 0.915 | 0.917 | 0.918 | 0.918 | 0.918 |

| 13.0 | 0.877 | 0.876 | 0.877 | 0.882 | 0.885 | 0.888 | 0.889 | 0.891 | 0.893 | 0.897 | 0.900 | 0.901 | 0.902 | 0.903 |

| 13.5 | 0.856 | 0.857 | 0.858 | 0.863 | 0.868 | 0.870 | 0.873 | 0.875 | 0.877 | 0.880 | 0.883 | 0.885 | 0.887 | 0.888 |

| 14.0 | 0.838 | 0.840 | 0.840 | 0.846 | 0.850 | 0.853 | 0.855 | 0.856 | 0.859 | 0.863 | 0.867 | 0.870 | 0.872 | 0.874 |

| 14.5 | 0.818 | 0.822 | 0.823 | 0.828 | 0.832 | 0.835 | 0.838 | 0.841 | 0.845 | 0.848 | 0.852 | 0.855 | 0.857 | 0.860 |

| 15.0 | 0.801 | 0.804 | 0.806 | 0.811 | 0.815 | 0.819 | 0.822 | 0.824 | 0.828 | 0.832 | 0.836 | 0.839 | 0.842 | 0.844 |

| 16.0 | 0.768 | 0.771 | 0.773 | 0.781 | 0.785 | 0.788 | 0.791 | 0.793 | 0.797 | 0.802 | 0.806 | 0.809 | 0.811 | 0.813 |

| 17.0 | 0.733 | 0.737 | 0.739 | 0.746 | 0.752 | 0.756 | 0.760 | 0.762 | 0.766 | 0.770 | 0.775 | 0.779 | 0.782 | 0.784 |

| 18.0 | 0.701 | 0.704 | 0.706 | 0.714 | 0.720 | 0.724 | 0.727 | 0.731 | 0.735 | 0.740 | 0.746 | 0.750 | 0.753 | 0.756 |

| 19.0 | 0.671 | 0.675 | 0.675 | 0.683 | 0.689 | 0.693 | 0.697 | 0.701 | 0.706 | 0.712 | 0.717 | 0.722 | 0.725 | 0.728 |

| 20.0 | 0.642 | 0.647 | 0.648 | 0.656 | 0.663 | 0.667 | 0.672 | 0.675 | 0.679 | 0.685 | 0.691 | 0.696 | 0.698 | 0.701 |

| 21.0 | 0.616 | 0.619 | 0.621 | 0.630 | 0.637 | 0.642 | 0.646 | 0.649 | 0.653 | 0.657 | 0.663 | 0.668 | 0.672 | 0.676 |

| 22.0 | 0.590 | 0.593 | 0.593 | 0.603 | 0.612 | 0.616 | 0.619 | 0.622 | 0.626 | 0.632 | 0.639 | 0.645 | 0.648 | 0.651 |

| 23.0 | 0.565 | 0.570 | 0.568 | 0.575 | 0.585 | 0.590 | 0.595 | 0.597 | 0.600 | 0.605 | 0.612 | 0.619 | 0.623 | 0.626 |

| 24.0 | 0.541 | 0.546 | 0.544 | 0.550 | 0.559 | 0.564 | 0.569 | 0.572 | 0.576 | 0.581 | 0.588 | 0.594 | 0.598 | 0.601 |

| 25.0 | 0.517 | 0.524 | 0.522 | 0.529 | 0.539 | 0.543 | 0.547 | 0.550 | 0.553 | 0.558 | 0.565 | 0.572 | 0.576 | 0.579 |

| Field size | 18 × 18 | 19 × 19 | 20 × 20 | 21 × 21 | 22 × 22 | 24 × 24 | 26 × 26 | 28 × 28 | 30 × 30 | 32 × 32 | 34 × 34 | 36 × 36 | 38 × 38 | 40 × 40 |

| Depth | ||||||||||||||

| 1.5 | 1.241 | 1.237 | 1.232 | 1.228 | 1.224 | 1.218 | 1.212 | 1.207 | 1.204 | 1.200 | 1.196 | 1.192 | 1.189 | 1.186 |

| 2.0 | 1.236 | 1.231 | 1.226 | 1.222 | 1.218 | 1.211 | 1.205 | 1.201 | 1.199 | 1.195 | 1.192 | 1.188 | 1.185 | 1.181 |

| 2.5 | 1.223 | 1.219 | 1.215 | 1.211 | 1.207 | 1.200 | 1.194 | 1.190 | 1.188 | 1.185 | 1.182 | 1.179 | 1.176 | 1.173 |

| 3.0 | 1.210 | 1.206 | 1.203 | 1.199 | 1.195 | 1.189 | 1.184 | 1.179 | 1.176 | 1.173 | 1.170 | 1.167 | 1.164 | 1.162 |

| 3.5 | 1.197 | 1.193 | 1.189 | 1.186 | 1.182 | 1.177 | 1.172 | 1.168 | 1.166 | 1.163 | 1.160 | 1.157 | 1.155 | 1.152 |

| 4.0 | 1.184 | 1.181 | 1.177 | 1.174 | 1.171 | 1.166 | 1.161 | 1.158 | 1.155 | 1.152 | 1.150 | 1.148 | 1.145 | 1.143 |

| 4.5 | 1.170 | 1.167 | 1.164 | 1.161 | 1.158 | 1.153 | 1.149 | 1.146 | 1.144 | 1.142 | 1.139 | 1.137 | 1.135 | 1.132 |

| 5.0 | 1.157 | 1.154 | 1.151 | 1.148 | 1.145 | 1.141 | 1.138 | 1.135 | 1.133 | 1.131 | 1.129 | 1.127 | 1.124 | 1.122 |

| 5.5 | 1.142 | 1.139 | 1.136 | 1.134 | 1.132 | 1.129 | 1.126 | 1.123 | 1.120 | 1.118 | 1.116 | 1.114 | 1.112 | 1.111 |

| 6.0 | 1.128 | 1.126 | 1.123 | 1.121 | 1.118 | 1.115 | 1.111 | 1.109 | 1.107 | 1.106 | 1.104 | 1.103 | 1.101 | 1.099 |

| 6.5 | 1.113 | 1.111 | 1.109 | 1.107 | 1.105 | 1.102 | 1.099 | 1.096 | 1.094 | 1.093 | 1.091 | 1.090 | 1.088 | 1.087 |

| 7.0 | 1.094 | 1.093 | 1.092 | 1.091 | 1.089 | 1.087 | 1.085 | 1.083 | 1.082 | 1.081 | 1.080 | 1.078 | 1.077 | 1.076 |

| 7.5 | 1.079 | 1.078 | 1.077 | 1.076 | 1.074 | 1.072 | 1.069 | 1.067 | 1.066 | 1.065 | 1.064 | 1.063 | 1.062 | 1.062 |

| 8.0 | 1.063 | 1.062 | 1.061 | 1.060 | 1.059 | 1.058 | 1.056 | 1.054 | 1.052 | 1.051 | 1.049 | 1.048 | 1.048 | 1.048 |

| 8.5 | 1.048 | 1.047 | 1.045 | 1.044 | 1.043 | 1.042 | 1.041 | 1.040 | 1.039 | 1.038 | 1.038 | 1.037 | 1.037 | 1.036 |

| 9.0 | 1.032 | 1.032 | 1.032 | 1.031 | 1.031 | 1.029 | 1.028 | 1.027 | 1.026 | 1.026 | 1.026 | 1.025 | 1.025 | 1.024 |

| 9.5 | 1.016 | 1.016 | 1.016 | 1.015 | 1.015 | 1.014 | 1.014 | 1.013 | 1.013 | 1.014 | 1.014 | 1.014 | 1.014 | 1.013 |

| 10.0 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| 10.5 | 0.986 | 0.986 | 0.986 | 0.986 | 0.985 | 0.985 | 0.985 | 0.986 | 0.986 | 0.986 | 0.987 | 0.987 | 0.988 | 0.988 |

| 11.0 | 0.970 | 0.971 | 0.971 | 0.971 | 0.972 | 0.972 | 0.972 | 0.972 | 0.973 | 0.973 | 0.974 | 0.975 | 0.975 | 0.975 |

| 11.5 | 0.954 | 0.955 | 0.955 | 0.956 | 0.956 | 0.957 | 0.959 | 0.960 | 0.960 | 0.960 | 0.960 | 0.960 | 0.961 | 0.961 |

| 12.0 | 0.938 | 0.938 | 0.939 | 0.939 | 0.940 | 0.941 | 0.943 | 0.945 | 0.945 | 0.945 | 0.945 | 0.946 | 0.946 | 0.947 |

| 12.5 | 0.920 | 0.921 | 0.922 | 0.924 | 0.925 | 0.927 | 0.929 | 0.931 | 0.932 | 0.932 | 0.933 | 0.933 | 0.934 | 0.935 |

| 13.0 | 0.904 | 0.905 | 0.906 | 0.908 | 0.909 | 0.911 | 0.913 | 0.915 | 0.916 | 0.917 | 0.918 | 0.920 | 0.921 | 0.922 |

| 13.5 | 0.890 | 0.891 | 0.892 | 0.894 | 0.895 | 0.898 | 0.901 | 0.903 | 0.904 | 0.905 | 0.905 | 0.906 | 0.907 | 0.908 |

| 14.0 | 0.876 | 0.877 | 0.879 | 0.880 | 0.881 | 0.883 | 0.885 | 0.887 | 0.889 | 0.891 | 0.892 | 0.894 | 0.895 | 0.897 |

| 14.5 | 0.861 | 0.863 | 0.864 | 0.866 | 0.867 | 0.869 | 0.872 | 0.874 | 0.876 | 0.877 | 0.878 | 0.880 | 0.881 | 0.883 |

| 15.0 | 0.846 | 0.848 | 0.849 | 0.851 | 0.853 | 0.856 | 0.859 | 0.862 | 0.864 | 0.865 | 0.867 | 0.868 | 0.870 | 0.871 |

| 16.0 | 0.815 | 0.818 | 0.820 | 0.822 | 0.825 | 0.829 | 0.833 | 0.837 | 0.839 | 0.840 | 0.842 | 0.843 | 0.845 | 0.846 |

| 17.0 | 0.787 | 0.789 | 0.792 | 0.794 | 0.796 | 0.801 | 0.805 | 0.809 | 0.812 | 0.814 | 0.815 | 0.816 | 0.818 | 0.820 |

| 18.0 | 0.758 | 0.761 | 0.763 | 0.765 | 0.768 | 0.773 | 0.777 | 0.782 | 0.786 | 0.787 | 0.789 | 0.791 | 0.793 | 0.795 |

| 19.0 | 0.730 | 0.733 | 0.736 | 0.739 | 0.741 | 0.746 | 0.751 | 0.756 | 0.760 | 0.762 | 0.764 | 0.766 | 0.769 | 0.771 |

| 20.0 | 0.703 | 0.706 | 0.709 | 0.712 | 0.715 | 0.721 | 0.727 | 0.732 | 0.736 | 0.739 | 0.742 | 0.744 | 0.747 | 0.749 |

| 21.0 | 0.679 | 0.682 | 0.685 | 0.687 | 0.690 | 0.695 | 0.701 | 0.707 | 0.713 | 0.716 | 0.718 | 0.720 | 0.722 | 0.725 |

| 22.0 | 0.653 | 0.655 | 0.658 | 0.661 | 0.664 | 0.670 | 0.677 | 0.683 | 0.689 | 0.692 | 0.694 | 0.696 | 0.698 | 0.700 |

| 23.0 | 0.628 | 0.631 | 0.634 | 0.636 | 0.639 | 0.645 | 0.652 | 0.659 | 0.665 | 0.668 | 0.670 | 0.672 | 0.674 | 0.676 |

| 24.0 | 0.603 | 0.606 | 0.609 | 0.612 | 0.615 | 0.622 | 0.629 | 0.636 | 0.642 | 0.646 | 0.648 | 0.650 | 0.651 | 0.654 |

| 25.0 | 0.582 | 0.584 | 0.587 | 0.591 | 0.594 | 0.600 | 0.607 | 0.615 | 0.621 | 0.626 | 0.628 | 0.629 | 0.630 | 0.633 |

TABLE IV.

Scatter correction factors for 6-MV x-rays (d0 = 10 cm).

| Field size | Total scatter | In-air output | Phantom scatter | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equivalent | correction factor | ratio | factor | |

| square | A/P | S c,p | S c | S p |

| 4.0 | 1.0 | 0.866 | 0.957 | 0.905 |

| 5.0 | 1.25 | 0.895 | 0.968 | 0.925 |

| 6.0 | 1.5 | 0.922 | 0.977 | 0.944 |

| 8.0 | 2.0 | 0.964 | 0.990 | 0.974 |

| 10.0 | 2.5 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| 12.0 | 3.0 | 1.028 | 1.008 | 1.020 |

| 14.0 | 3.5 | 1.051 | 1.014 | 1.037 |

| 16.0 | 4.0 | 1.070 | 1.018 | 1.051 |

| 20.0 | 5.0 | 1.102 | 1.024 | 1.076 |

| 24.0 | 6.0 | 1.127 | 1.029 | 1.096 |

| 28.0 | 7.0 | 1.149 | 1.034 | 1.111 |

| 32.0 | 8.0 | 1.167 | 1.040 | 1.123 |

| 40.0 | 10.0 | 1.194 | 1.048 | 1.139 |

III.B.1.d. Sc

Sc is the ratio of in-air radiation output for a given collimator setting to that for a collimator setting of 10 × 10 cm2.10 Figure 5 diagrams a typical measurement setup, for a ion chamber placed in a mini-phantom at the isocenter. Sc is measured for different square collimator settings ranging over all clinically used field sizes. It is recommended that a sufficient number of field sizes be measured such that Sc changes by less than ∼1% between consecutive measured collimator settings. The magnitude of the collimator exchange effect for large, clinically relevant aspect ratios (e.g., 5 × 40 and 40 × 5 cm2) should be determined and the accuracy of the algorithm in predicting the output for these field shapes should be verified. For these field sizes, users should account for the stem effect in the measurement results.

FIG. 5.

Diagram illustrating measurement setup for Sc. The cylindrical mini-phantom is aligned coaxially with the central axis of the beam, with the ion chamber positioned at the source-detector distance corresponding to the chosen normalization conditions. The field size is maintained large enough to ensure coverage of the mini-phantom, and other scattering materials are removed from the treatment field.

The effective thickness of buildup material along the direction of the radiation beam has been discussed in several reports.10,61–64 The thickness of material perpendicular to the beam direction should provide enough lateral scatter65 so that the accuracy of the measured Sc is maintained. This task group recommends a 4-cm diameter cylindrical mini-phantom56 coaxial with the central axis of the beam with the detector at 10-cm depth for the measurement of Sc independent of the normalization depth. It is pointed out in the report of the AAPM Therapy Physics Committee TG 74 (Ref. 10) that it is more accurate for calculations beyond the range of contamination electrons to use Sc measured at 10 cm. Water-equivalent materials are recommended for the construction of the mini-phantom, given reports of some variation in results using high Z build-up materials.65 However, for field sizes between 1 and 5 cm, a high Z mini-phantom can be used as long as the Sc is renormalized so that the Sc measured at 5 cm field size matches that measured with a water equivalent mini-phantom, as described in the TG-74 report.10

Sc should be measured with the detector at the isocenter unless the field size for the measurement does not encompass the whole phantom. Care should be taken to minimize the amount of scattered radiation from structures close to the detector, such as support stands, the floor, the wall, or the table. A Styrofoam stand can be used to support the detector away from any backscattering material. It is recommended that the measurements be made with the beam pointing at the wall instead of the floor to reduce scattered radiation. This irradiation configuration also allows the alignment of the axis of the mini-phantom with the central axis of the beam using lasers and crosshair. The detector should be checked for stem and cable effects, especially for fields with large aspect ratios.

In order to commission the calculation algorithm based on the point's-eye-view of the treatment head, the distances of the proximal surface of all collimators from the target along the direction of the central axis should be either obtained from the manufacturer or measured.

Table IV gives Sc data for a 6-MV photon beam with a normalization depth of 10 cm.

III.B.1.e. Sp

Sp is defined as the ratio of the dose rate at the normalization depth for a given field size in a water phantom to that of the reference field size for the same incident energy fluence. Sp can be computed as a function of the field size at the irradiated volume from the measured quantities Scp and Sc,

| (17) |

Scp is measured in a water phantom at SSD0 with the detector at d0 for different collimator settings. For the same d0, Sp should display little to no variation between linear accelerators with the same beam quality, so that comparisons between different machines and/or with published results66 may be useful in verifying results of a specific machine.

Table IV displays sample Sp data for a 6 MV photon beam for a normalization depth of 10 cm. In contrast to the data for Sc, these data exhibit a much greater dependence on the depth of normalization.

III.B.1.f. Off-axis ratios

In this protocol, MU calculations to off-axis points are made using central axis dosimetric quantities (e.g., Scp, TPR), with an open-field off-axis ratio, OAR. Although there are circumstances where off-axis calculations are preferred (e.g., when the central axis is blocked or in regions of electronic disequilibrium), this task group recommends that every attempt be made to keep this calculation on the central axis to avoid the complications associated with off-axis calculations.

Several methods have been proposed for the determination of OAR for MU calculation. Early recommendations were to equate OAR with large field central axis profile data.67,68 However, measured profile data inherently contain changes in the relative scatter contribution within the phantom which are not accounted for in the current formalism.69 Although good agreement is obtained for points close to the central axis,67,70 errors greater than 5% can be obtained using profile data close to the edge of the field (e.g., x > 10 cm). Although calculations to points this far off-axis are unlikely to be seen in the clinic with any frequency, caution should be used when using these data for OAR.

Better agreement has been found equating OAR to the primary off-axis ratio, POAR. This quantity represents the ratio of doses due only to primary (unscattered) photons. POARs may be obtained either by extraction from large-field central axis profiles or by direct measurement. Unlike large-field profile data, POARs will not decrease near the field edge due to reduced scatter. Chui et al.71 proposed determining POAR by measuring profiles at extended distances, where the scatter contributions to the projected off-axis points have equilibrated. In their work, profile data were measured at various depths on the floor using film dosimetry.

Gibbons and Khan70 measured transmitted dose profiles through different thicknesses of absorbers under “good geometry” conditions (narrow beam and large detector-to-absorber distance). In this method, the beam is collimated using asymmetric fields or MLCs to define small fields (e.g., 2 × 2 cm2) on-axis and at off-axis positions. POARs are calculated using the ratio of in-air ion chamber readings (with appropriate buildup) at large distances from the source to minimize scatter. Plastic absorbers are placed near the collimating jaws to determine the depth dependence of these ratios.

Finally, there are independent analytic formalisms that remove the scatter component from measured commissioning data.70,72–74 Additionally, depending on the planning system it may be possible to extract the primary energy fluence transmitted through a flat water phantom to determine POAR. In either case, it is recommended that a few sample measurements be made to confirm these data. This can be easily performed by measuring the dose per MU for some simple off-axis fields.

It is the recommendation of the task group that primary off-axis profiles be used for OARs. Typically, these data do not change rapidly with off-axis distance or depth, and interpolation between a few points will provide sufficient accuracy. An example dataset is shown in Table V, which displays sample POAR data for a 6-MV photon beam. These OAR data were taken from the “primary profile” data of the Theraplan treatment-planning system, originating from measured large field profiles.75 The radial distance from the central axis should be used, because the flattening filter is radially symmetric.

TABLE V.

Open field off-axis ratios for 6-MV x-rays. Sample data from a Varian Clinac 2100C accelerator.

| OADa | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (cm) | 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 15 | 18 |

| Depth (cm) 1.5 | 1.000 | 1.006 | 1.022 | 1.030 | 1.034 | 1.043 | 1.055 | 1.058 |

| 3.0 | 1.000 | 1.011 | 1.027 | 1.033 | 1.040 | 1.045 | 1.056 | 1.058 |

| 5 | 1.000 | 1.017 | 1.033 | 1.041 | 1.046 | 1.048 | 1.058 | 1.057 |

| 8 | 1.000 | 1.011 | 1.030 | 1.036 | 1.040 | 1.043 | 1.050 | 1.051 |

| 10 | 1.000 | 1.006 | 1.028 | 1.030 | 1.031 | 1.031 | 1.033 | 1.032 |

| 12 | 1.000 | 1.006 | 1.023 | 1.028 | 1.029 | 1.026 | 1.026 | 1.026 |

| 15 | 1.000 | 1.007 | 1.016 | 1.025 | 1.025 | 1.018 | 1.016 | 1.016 |

Radial off axis distances projected on a plane at 100 cm from source.

III.B.1.g. Tray factors (TF)

TF is defined as the ratio of the dose rate at the point of calculation for a given field with and without a blocking tray in place. TF is almost independent of field size, depth, and SSD, and a constant value is sufficient in most cases. The presence of the tray will affect the dose in the build-up region through the production of secondary electrons as well as the absorption of secondary electrons produced upstream of the tray. Thus, it is recommended that this factor be measured at a depth well beyond the maximum range of electron contamination. The TF may also be used to account for attenuation due to other devices, such as additional trays, beam spoilers, or special patient support devices.

III.B.1.h. Compensators

Unlike blocking trays, compensators are specifically designed to affect the dose per MU within the field and often have a more significant impact on the MU calculation. In addition, the presence of a compensator mounting tray must be included in the calculation. The calculation is most significantly affected by the thickness of the compensating filter placed directly over the point of calculation.

Ideally, compensators are designed such that no compensating material is placed directly over the point of calculation and no correction is required. Otherwise, compensators may be included within the calculation in a couple of ways. First, the compensator may be included in the TF, which represents the ratio of doses to the point of calculation with and without the compensator for a given number of monitor units. For a compensator of a given thickness, the amount of attenuation depends on a variety of parameters including beam energy, compensator-to-patient surface distance, field size, and depth.76 These dependencies are usually slowly varying, although larger variations have been noted for regions near highly sloped surfaces or within or near the buildup region.77 For a given geometry and beam quality, however, the compensator effect can be approximated as being dependent only on the amount of compensating material placed directly above the point of calculation. The net effect can be determined either by direct measurement, or approximated by effective (broad-beam) linear attenuation coefficients. If simple step-wedge compensators are fabricated using a combination of a number of individually positioned sheets, one may create a table of attenuation factors as a function of the number of sheets. As in the case of blocking trays, the attenuation factors should be measured at a depth beyond the range of contaminant electrons, e.g., at the normalization depth.

An alternative approach is to treat the compensator as replacing tissue deficit.27 In this approach, there is no modification of the attenuation factor, and the beam attenuation is accounted for by the increased effective depth of the point of calculation. The amount of missing tissue “replaced” by the compensator is determined by scaling the tissue deficit by the ratio τ/ρe, where τ is a unitless factor that accounts for the resulting loss of scatter due to the compensator's placement in the collimator head, and ρe is the electron density (relative to water) of the compensating filter material. Details of this approach have been published in Ref. 27.

III.B.1.i. Wedge factors