Abstract

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a common and potentially disabling disorder that develops in 1/5 to 1/3 of people exposed to severe trauma. Twin studies indicate that genetic factors account for at least one third of the variance in the risk for developing PTSD, however, the specific role for genetic factors in the pathogenesis of PTSD is not well understood. We studied genome-wide gene expression and DNA methylation profiles in 12 participants with PTSD and 12 participants who were resilient to similar severity trauma exposure. Close to 4,000 genes were differentially expressed with adjusted p < 0.05, fold-change > 2, with all but 3 upregulated with PTSD. Eight odorant/olfactory receptor related genes were up-regulated with PTSD as well as genes related to immune activation, the Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid A (GABAA) receptor, and vitamin D synthesis. No differences with adjusted significance for DNA methylation were found. We conclude that increased gene expression may play an important role in PTSD and this expression may not be a consequence of DNA methylation. The role of odorant receptor expression warrants independent replication.

Keywords: Microarray, Biomarker, Epigenetic, odorant receptor, GABAA receptor, Vitamin D Synthesis

1. Introduction

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder or PTSD develops in approximately one fifth to one third of those exposed to a traumatic event and can feature considerable distress and dysfunction. Among those who end up meeting diagnostic criteria for PTSD, approximately one third will go on to develop a chronic and persisting course and are at high risk for both psychiatric and medical comorbid conditions (Kessler et al., 1995). It is therefore critical to understand mechanisms that confer vulnerability and resilience to the development of PTSD and conditions that are commonly associated with the disorder. Twin studies implicate an important role for genetic factors which have been estimated to account for at least one third of the variance in the risk for developing PTSD (Koenen et al., 2008, True et al., 1993). Candidate gene studies have provided some evidence for the involvement of specific genes including those with products involved in serotonin and cortisol transport and adrenergic neurotransmission; however, this evidence is limited and often not consistent (Andero et al., 2014, Koenen et al., 2011, Liberzon et al., 2014, Xie et al., 2009). Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) provide a more comprehensive approach to identifying relationships between diseases and specific genes as well as novel regions of the genome. Results for four GWAS of PTSD have implicated several genes that are involved in neuro transmission, plasticity, and protection. They provide only limited support for previous findings associating candidate genes with PTSD and have also not produced consistent findings. Two of these studies featured European Americans, another African Americans, and the largest study which was multiethnic, featured only males (Guffanti et al., 2013, Logue et al., 2013, Nievergelt et al., 2015, Xie et al., 2013).

Environmental factors, including trauma exposure, can alter gene expression in part as a consequence of DNA methylation. For example, people with PTSD who experienced child abuse were found to have up-regulated expression of genes mainly involved in central nervous system development and tolerance induction pathways, while in the PTSD group without a history of child abuse, the up-regulated genes were more likely to be involved in apoptosis and growth rate networks. Overall, genes were more heavily methylated in PTSD subjects with child abuse histories compared to those without (Mehta et al., 2013). Consistent with studies suggesting compromised regulation of inflammatory activity with PTSD (Hoge et al., 2009), chronic PTSD has been associated with hyper-methylation of inflammatory initiator genes and demethylation of inflammatory regulatory genes (Hollifield et al., 2013). Involvement of genes regulating immune products with PTSD has also been suggested by prospective findings from pre - and post - deployment samples of military personnel (Rusiecki et al., 2012).

It is possible that gene expression and methylation patterns associations with PTSD could be related to the degree of trauma exposure. A recent analyses of PTSD versus non-PTSD or resilient outcomes in deployed military personnel implicated degrees of trauma exposure as a factor determining PTSD (Boasso et al., 2015). Thus the degree of trauma exposure could confound case control studies of PTSD even when controls are defined as trauma exposed. In the present study we attempted to address this concern via recruitment of a resilient control group with similar severity of trauma exposure as the cases with PTSD. This study also provides data from an African American sample and examined both genome-wide methylation and gene expression differences between trauma-exposed young adults with and without PTSD.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Twenty four participants were selected from a larger study of PTSD, sleep, and cardiovascular risk markers. Healthy African Americans age 18 – 35 were recruited via flyers in strategic community settings and referrals from previous participants. The protocol was approved by the Howard University Institutional Review Board. Potential participants were screened and excluded if they were found to have a body mass index ≥ 40, medical disorder requiring continuous medication, severe mental disorders (psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder, severe recurrent depression), ongoing hazardous drinking (i.e. > 14 alcoholic drinks/week in men or > 7 drinks/week in women) and heavy caffeine consumption or smoking and unconventional sleep/wake schedules. Eligible participants were then invited to the Howard University Clinical Research Unit where they signed informed consent forms after receiving detailed description of the study and completed the self-report surveys which included a demographic questionnaire, a checklist of traumatic experiences, and a measure of PTSD symptom severity. Consideration for invitation to the laboratory phase of the study included over-sampling of probable PTSD and balancing representation of males and females. One hundred thirty six participants completed a clinical interview, a morning blood draw, and urine toxicology screening. Participants with positive drug tests were excluded.

Eighty three percent (n = 78) of the 94 participants who were recruited to the laboratory phase and consented to blood sampling had experienced a lifetime trauma meeting DSM-IV PTSD criterion A for based on the Clinician Assessed PTSD Scale (CAPS) (Blake et al., 1995); 12 (12.8 % of the total) met full current PTSD criteria, an additional 14 (14.9%) had current sub-threshold symptoms (at least 2 but not 3 of the symptom cluster criteria); an additional 19 (20.2%) met criteria for PTSD during their lifetime and had recovered, and 49 (52.1% of the study group), 433 of whom were trauma exposed, never developed PTSD. From these participants we selected the 12 with full current criteria for PTSD and 12 of the trauma exposed, PTSD negative group with exposure to high impact traumas (trauma categories with high risk for developing PTSD in population studies, e.g. physical and sexual assault) who also never developed PTSD or subthreshold PTSD during their lifetime. Participant characteristics for this study are presented in Table I. Blood samples were processed immediately after they were drawn. Serum, plasma, buffycoat, and blood clot were stored at −70°C.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| PTSD (n = 12) | Control (n = 12) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | t | |

| Age | 23.0 (4.3) | 22.1 (3.3) | 0.58 |

| No. of trauma types exposed | 7.4 (2.9) | 4.7 (1.7) | 2.84** |

| n | n | ||

| Sex (Female) | 6 | 5 | |

| Types of index trauma | |||

| Non-sexual violent crime | 3 | 6 | |

| Sexual assault | 2 | 1 | |

| Childhood abuse (physical and/or sexual) | 3 | 5 | |

| Intimate partner violence | 2 | 0 | |

| Violent death of someone close | 2 | 0 | |

Note.

p< .01

2.2. RNA isolation and mRNA (exon) expression profiling

Manufacturers’ instructions for commercial reagent kits were strictly followed when applicable. Total RNA was isolated from frozen blood clots and extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). After the extraction, RNA concentration and purity (OD260/280) were measured using the NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA), and the RNA integrity number (RIN) was determined using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer Instrument (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA). Expression profiles were determined using Affymetrix Gene Chip Human Exon 1.0 ST Arrays (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The Ovation Pico WTA System (NuGEN Technologies, San Carlos, CA, USA) was used to generate single-stranded cDNA from the entire expressed genome (50ng total RNA). The WT-Ovation Exon Module (NuGEN Technologies, San Carlos, CA, USA) was used to convert the cDNA into sense target cDNA (ST-cDNA), which was fragmented and labeled using the Encore Biotin Module (NuGEN Technologies, San Carlos, CA, USA). The Affymetrix Hybridization Wash Stain (HWS) kit was used for the Array hybridization, washing, and staining. Arrays were hybridized by rotating them at 60 rpm in the Affymetrix GeneChip hybridization oven at 45 °C for 16 h. After hybridization, the arrays were washed in the Affymetrix GeneChip Fluidics station FS 450 and then scanned using the Affymetrix GeneChip scanner 3000 7G system. Gene- and exon-level expression signal estimates were derived from cell intensity files (CEL) generated from Affymetrix GeneChip Exon 1.0 ST arrays.

2.3. DNA isolation and global methylation analysis

Total DNA was isolated from clotted blood samples using a clotspin basket (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) to disperse the clot followed by extraction using the MasterPure Complete DNA & RNA Purification Kit (Epicentre, cat#MC85200). After the extraction, DNA concentration and purity (OD260/280) were measured using the NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). A minimum of 500ng DNA was used for bisulfite conversion using the EZ DNA Methylation kit (Zymo Research Corp (Irvine, CA, USA) and a GeneAmp PCR system 9700 (Applied Biosystems, Grand Island, NY, USA). To confirm successful bisulfite modification, the DNA was subjected to PCR using methylation-specific primers. Methylation analysis was performed using the Illumina Infinium Human Methylation450 Beadchip platform (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Bisulfite-modified DNA was fragmented into 300–600 bp fragments, purified by isopropanol precipitation, and resuspended in hybridization buffer. The sample was then hybridized to an Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 Beadchip. The BeadChips were then washed, stained and dried. The BeadChips were then scanned using a HiScanSQ System (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Methylation data were processed through Illumina Genome Studio (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) and analyzed in Partek.

2.4. Data analysis

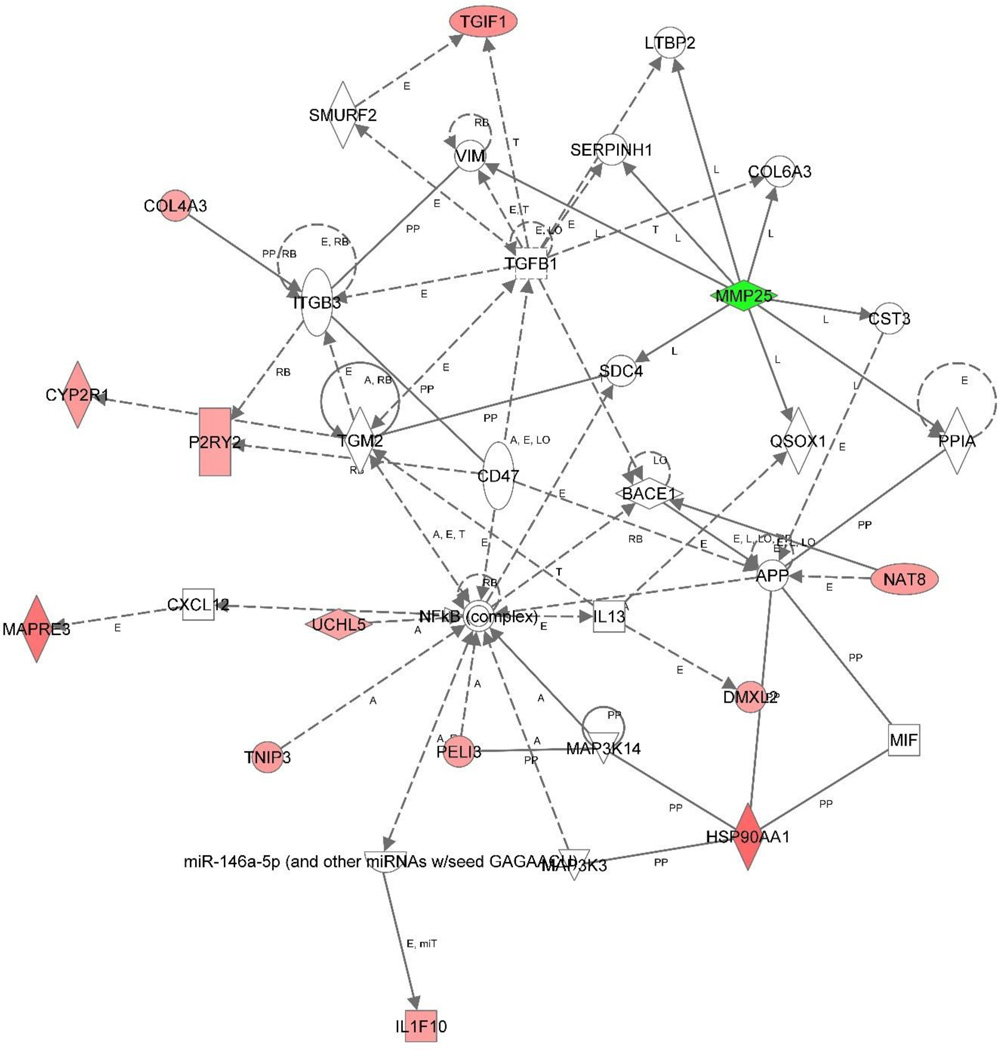

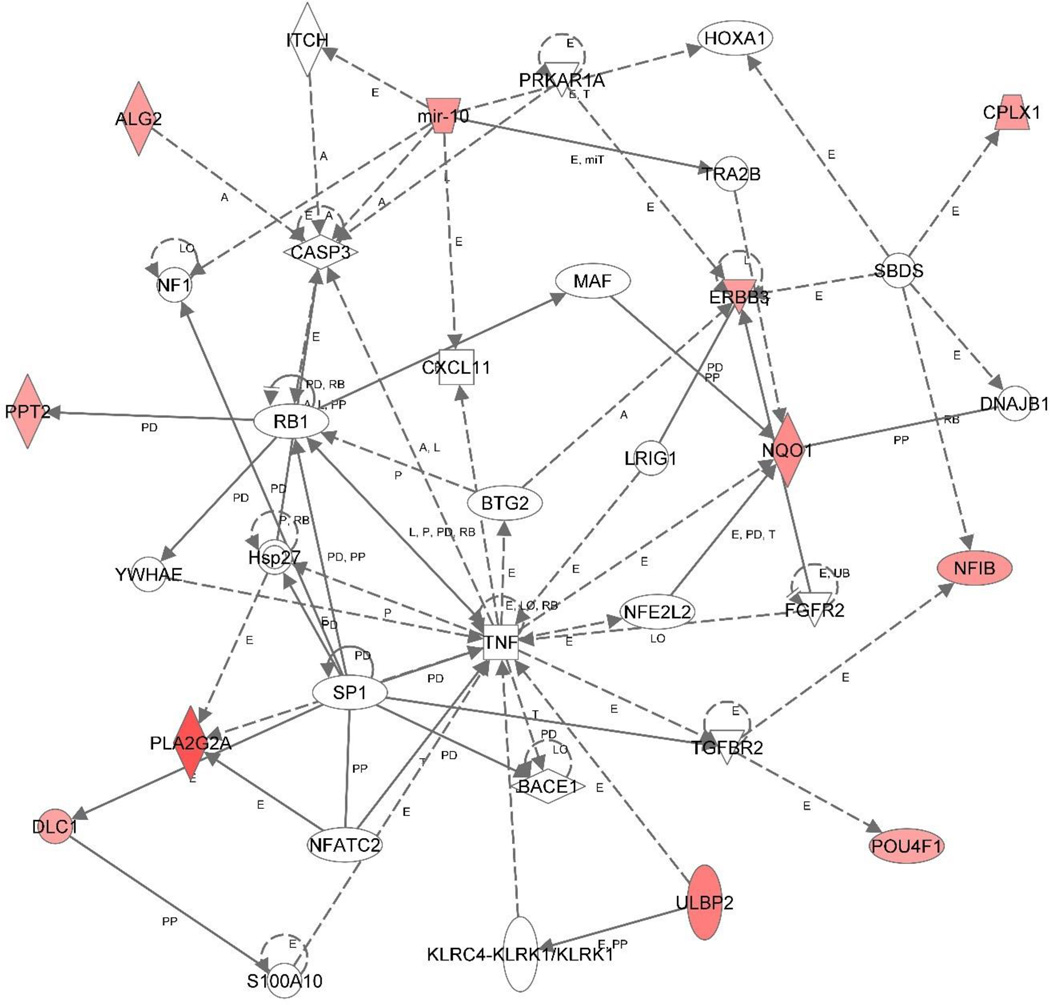

Genes with significant differences in expression or methylation were identified by applying paired t-tests on each gene separately using the cutoff combination of Benjamini Hochberg multi-test adjusted p ≤ 0.05 and also p ≤ 0.01 and absolute fold change ≥ 2.0. Ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA) (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) was used to analyze pathways of genes that were significantly up or down regulated. Based on the context of molecular mechanisms stored in the Ingenuity database, networks are generated for differentially expressed groups of genes. On the pathway/network figures, nodes represent genes and straight lines with arrows indicate the known biological relationship between two nodes. Nodes are displayed using various shapes that represent the functional classes of the gene product. The nature of the relationship between two different nodes is displayed by the edges. Edges are supported by scientific publications that are stored within the Ingenuity Pathways Knowledge Base. Nodes are color coded for up-regulation (red) and down-regulation (green) and the intensity of the color demonstrate the degree of up- and down-regulation when compared to the resilient controls.

The hierarchical clustering method was then applied to cluster genes (rows) as well as samples (columns) provided from the significant gene list by the threshold of Benjamini Hochberg multi-test-adjusted p value p ≤ 0.01 and fold change ≥ 2.0. Log base 2 transformed intensity values were standardized. Last the average linkage was applied to the gene clusters and sample clusters.

Canonical pathway analysis was also performed with the most significant 103 up- and down-regulated genes in a dataset using the Ingenuity pathways analysis (IPA) software package. The canonical pathway analysis took into account all canonical pathways that had integrations with the significant genes. Fischer’s exact test was used to calculate p values and to determine the probability of association between the genes in the dataset. The ratio was computed as the number of given genes in one canonical pathway divided by the total number of genes in that pathway. The functional pathway analysis represented all possible biological functions that were the most significant in the dataset. Fischer’s exact test was used to calculate a p value and to determine the probability that each biological function and/or disease assigned to that network was not due to chance.

3. Results

3.1. Gene Expression

A total of 3,992 genes were differentially expressed with adjusted p < 0.05, fold-change > 2, comparing PTSD cases and resilient controls. All gene expressions were up-regulated except three, which were down-regulated. With narrowing the statistical stringency to p < 0.01, fold-change > 2, the total number of differentially expressed genes were 591, all of which were up-regulated.

3.2. Hierarchical Clustering Analysis

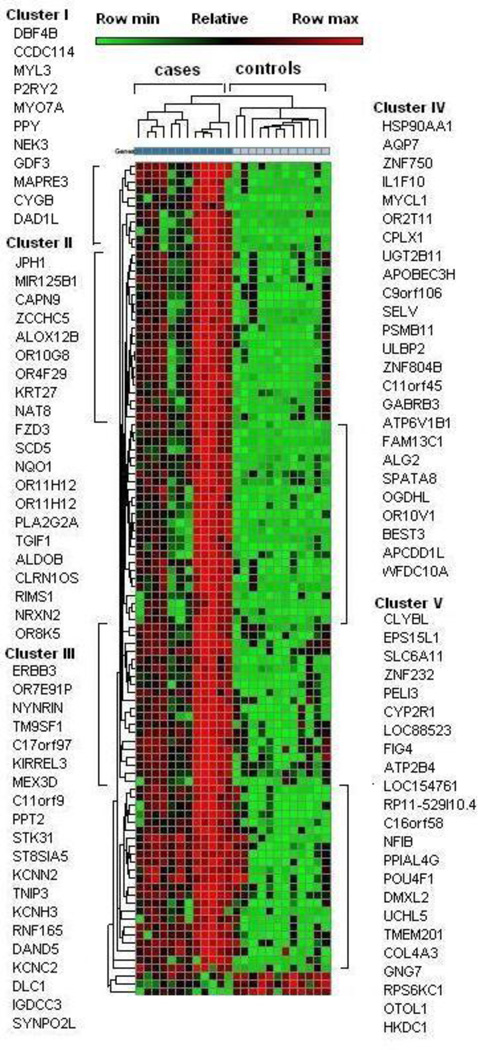

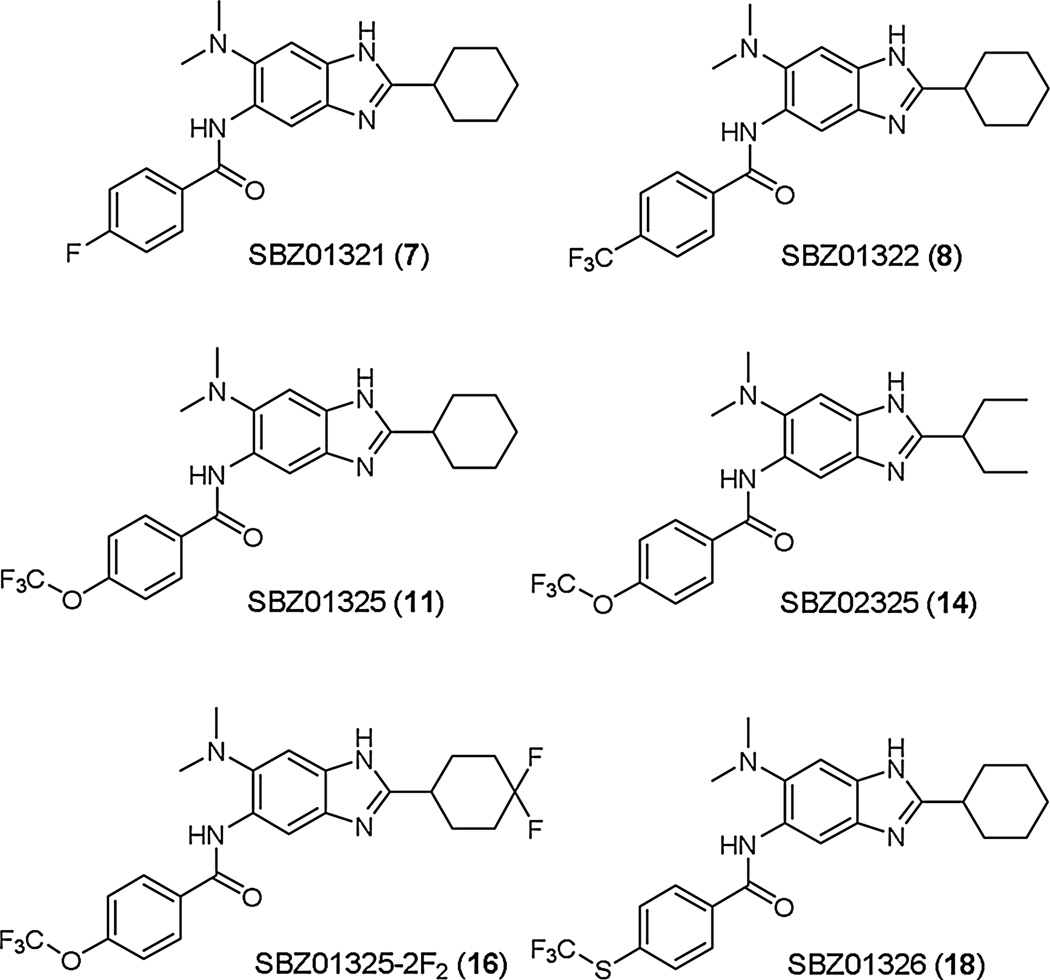

Hierarchical clustering of the 100 most significantly differentially expressed genes was conducted as well as to the three down-regulated genes (p<0.05, fold-change >2). The heatmap (Figure 1) shows a significant difference of the gene expression between the cases and controls (p<0.05, right-tailed Fisher’s exact test). Five main clusters of genes were derived based on the differential expression pattern of the 103 genes as shown in Figure 1. The complete list of all genes in each cluster along with fold change and respective p value is given in Supplementary Table-1.

Figure 1.

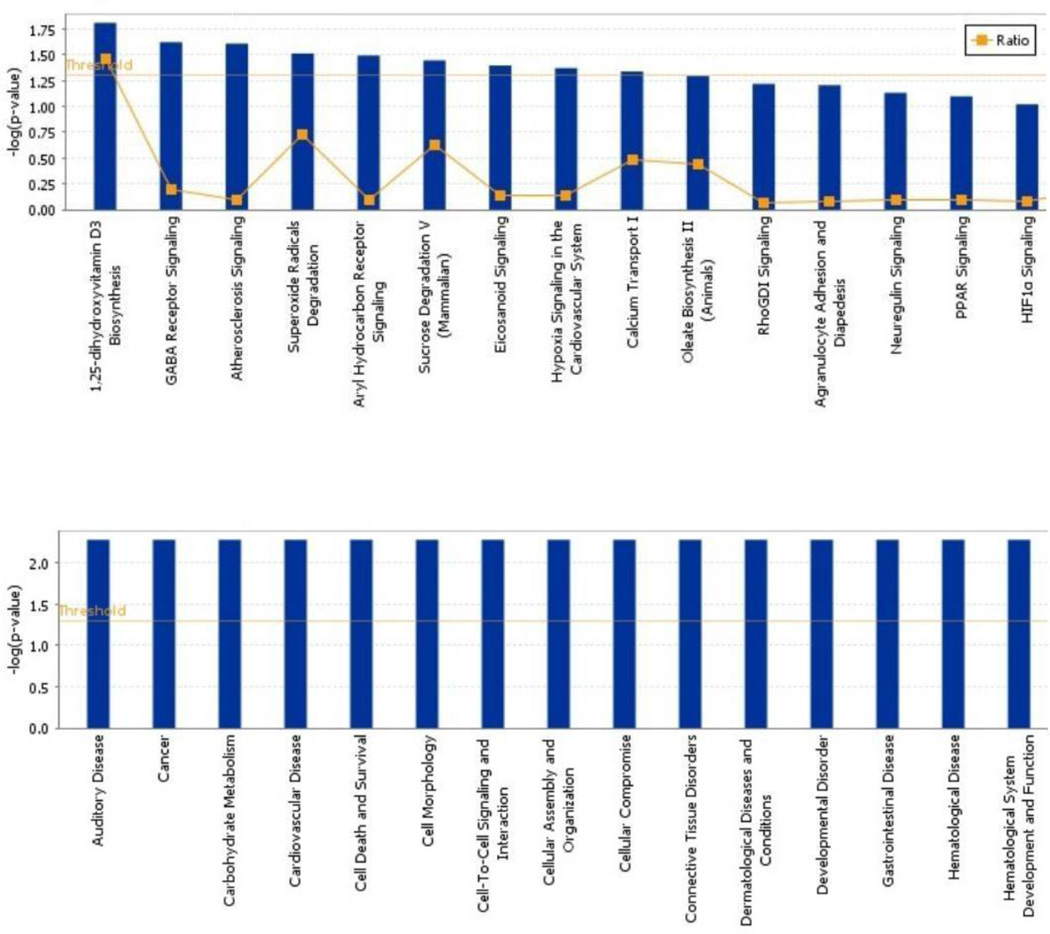

Canonical and functional pathway analysis. A. Global canonical pathway analysis were performed using Ingenuity Pathway Knowledge Base to deduce the upregulation and downregulation of the cellular pathways. The dataset contains all the genes differentially expressed (p<0.05, fold change >2). The ratio is computed as the number of given genes in one canonical pathway divided by the total number of genes in that pathway. B. Global functional pathway analysis was conducted using Ingenuity Pathway Knowledge Base to extrapolate the cellular functions comparing cases and controls. In all the panels above, p value (p<0.05) indicating the statistical significance was calculated using the right-tailed Fischer’s exact test.

Cluster I contains 11 genes, five of which code for structural proteins such as actin or microtubules related to ciliated cells, including CCDC114, MYL3, MYO7A, NEK3, and MAPRE3. One gene, CYGB is involved in signal transduction. Cluster II had 19 genes, five of which are related to signal transduction including JPH1, ZCCHC5, FZD3, TGIF1, RIMS1 and NRXN2. Five genes related to odorant/olfactory receptors including OR10G8, OR4F29, OR11H12, and OR8K5. Cluster III had a total of 25 genes, ten of which are involved in signal transduction (HSP90AA1, ZNF750, CPLX1, APOBEC3H, ULBP2, ZNF804B, GABRB3, ATP6V1B1, BEST3, APCDD1L, two genes related to odorant/olfactory receptor, OR2T11 and OR10V1. Cluster IV had 19 genes, ten of which are related to signal transduction (ERBB3, NYNRIN, KIRREL3, MEX3D, C11orf9, KCNN2, TNIP3, KCNH3, RNF165, KCNC2), and one gene, OR7E9P, related to odorant/olfactory receptor. Cluster V had 21 genes, twelve of which are involved in signal transduction (ATP2B4, EPS15L1, SLC6A11, ZNF232, PELI3, CYP2R1, NFIB, POU4F1, DMXL2, UCHL5, GNG7, RPS6KC1).

3.3. Canonical and functional pathway analysis

Canonical pathways were explored using Ingenuity Pathway Knowledge Base by comparing PTSD cases and resilient controls for the differential expression of the top 103 genes (figure 2A). In the figure, the ratio indicates the number of genes participating in the deduction of the canonical pathways divided by the total number of genes in that pathway. The threshold for the canonical analysis was set to the default of p<0.05. Affected pathways includes 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 Biosynthesis, the only pathway with the ratio over the set threshold and reportedly linked to PTSD (Ji et al., 2014). Gene in this pathway includes CYP2R1 (fold change 14.2486, p=0.0000199). Among other affected pathways, the GABA Receptor Signaling pathway has been widely reported being related to PTSD. Genes in this pathway include GABRB3 (fold-change 14, p=0.0038) and SLC6A11 (fold-change19, p=0.0033).

Figure 2.

Hierarchical clustering of the top 103 genes (p<0.05, fold change > 2) generated from Ingenuity Pathway Knowledge Base. Hierarchical gene clustering showed significant changes in gene expression comparing PTSD cases and the resilient controls. Five major clusters of functional genes were created from the heat map. Complete gene list of each cluster along with its fold change and p value is given in Supplementary Table 1.

Global functional pathway analysis was also performed using Ingenuity Pathway Knowledge Base to evaluate the function of 103-gene dataset. Olfaction is among the highest differentially expressed functions in our comparison of PTSD cases and controls. A total of eight genes related to odorant/olfactory receptors that were up-regulated in the overall dataset: OR10G8 (fold-change14.4, p=0.0055), OR4F29 (fold-change 14.6 p=0.0079), OR11H12 (fold-change 29, P=0.0022), OR11H2 (fold-change 18.0784, P=0.0022), OR8K5 (fold-change 12.8, p=0.0019), OR2T11 (fold-change 13.6, p=0.00013), OR10V1 (fold-change14.3, p=0.0059), OR7E91P (fold-change13, p=0.0094).

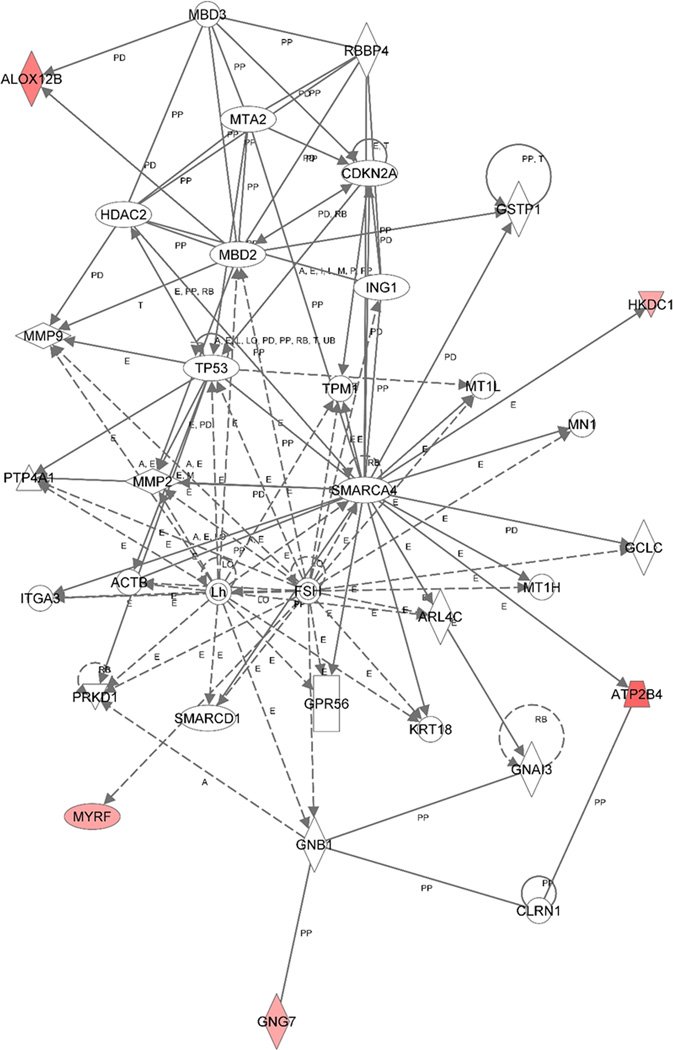

3.4. Gene Network Analysis

Three gene networks were identified. Gene network 1 (Figure 3) was centered at NFkB complex, which is a protein complex that controls transcription of DNA in all human cell types. Thirteen genes which were differentially expressed comparing PTSD patient and resilient controls were found in this gene network including seven genes involved in signal transduction directly or indirectly as a transcription factor, TGIF1 (fold change 16, p=0.0022), HSP90AA1 (fold change 21, p=0.00007), TNIP3 (fold change 14, p=0.0069), PELI3 (fold change 14, p=0.0022), DMXL2 (fold change 13, p=0.0078), UCHL5 (fold change 13, p=0.0178), CYP2R1 (fold change 14, p=0.0038). Gene network 2 (Figure 4) was centered at TNF, a well-known multifunction cytokine. Ten genes from our list were found in this gene network including five genes involving in signal transduction, CPLX (fold change 14, p=0.0020), ULBP2 (fold change 18, p=0.0068), ERBB3 (fold change 14, p=0.0066), NFIB (fold change 15, p=0.0066), Pou4F1 (fold change 13, p=0.0107). Gene network 3 (Figure 5) has less clear functional links and included only four genes that have mixed functions.

Figure 3.

Gene networks generated from the selected 103 genes using Ingenuity Pathway Knowledge Base. A. Gene network centered at NF-κB, a transcription regulator that is activated by various intra- and extra-cellular stimuli such as cytokines, oxidant-free radicals, ultraviolet irradiation, and bacterial or viral products. B. Gene network centered at TNF, a multifunctional proinflammatory cytokine.

Figure 4.

Figure 5.

3.5. DNA methylation profiling

No methylation site reached p < 0.05 after multiple test correction. Among the top 100 up-regulated genes with highest fold change in gene expression study, 14 had an unadjusted p < 0.05 (data not presented) in methylation comparing PTSD cases and resilient controls. All of these 14 genes were up-regulated in gene expression with PTSD, six (42%) showed higher methylation levels with PTSD.

4. Discussion

We conducted whole genome gene expression and DNA methylation of samples from participants with PTSD and resilient controls with similar levels of trauma exposure. Numerous genes were differentially expressed, almost all of which were elevated with PTSD. However, none of the methylation findings met whole genome significance and none of the methylation profiles with unadjusted significance of p < .05 corresponded with the genes that were upregulated.

Generally, methylation is correlated to inhibition of gene expression and demethylation is associated with increased gene expression (see review by Van Panhuys et al., 2008). However, using the same biological samples, we found significantly up-regulated gene expression ranging from 12–29 fold with very few genes down-regulated, but no significant methylation was found comparing the same cases and controls. While methylation is considered an important regulator of gene expression other studies have also not found gene expression profiles to not correspond with methylation profiles (Uddin et al., 2011). Differential gene methylation has been reported with PTSD in some previous studies. Uddin et al. (2010) found several genes related to immune function to be differentially methylated in subjects with PTSD. The same group reported later (Uddin et al., 2011) that among the 33 genes previously shown to differ in whole genome expression, only the methylation level of one gene, MAN2C1, modified cumulative traumatic burden on the risk of PTSD. Smith et al. (2011) reported that CpG sites in five genes (TPR, CLEC9A, APC5, ANXA2, and TLR8) were differentially methylated in subjects with PTSD in a genome wide methylation study in African Americans. Rusiecki et al. (2013) explored changes in DNA methylation of immune-related genes in US military service members with a PTSD diagnosis and found differential patterns of methylation pre- versus post-deployment. In our study the differentially expressed genes in PTSD do not appear to be a consequence of corresponding DNA methylation in the genome, though we cannot exclude that the study’s small sample size as a reason for the failed detection of methylation sites.

Some of the findings for up-regulated gene expression are consistent with previous findings in the literature including the representation of genes related to inflammatory processes. Segman et al. (2005) first reported expression signatures for transcripts involved in immune activation in people with PTSD four months after trauma exposure and Zieker et al. (2007) also demonstrated differential expression of several immune-related genes with PTSD. Uddin et al. (2010) demonstrated reduced methylation levels of immune-related genes with PTSD which could influence increased expression. Differentially expressed genes involved in immune cell activity, along with HPA axis function and signal transduction were also reported by Yehuda et al. (2009). Immune dysregulation more generally has been linked to PTSD and its comorbidity (Hoge et al., 2009, Baker et al., 2012, Neylan et al., 2011). Multiple genes related to intracellular or extracelluar structures (actin, microtubule, myosin, dynein keratin etc.) and genes related to signal transduction pathways were also up-regulated in our study. It may be reasonable to explain that genes related to signal transduction are up-regulated due to the stimulation and subsequent reactive body response to traumatic stress. However, we are not aware of other reports linking structural genes to PTSD and other psychiatric conditions, so this warrants scrutiny in future studies. Other top genes for which we found up-regulated expression are involved in other systems implicated in PTSD and/or other psychiatric disorders including two Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid A (GABAA) receptor related genes (GABRB3, SLC6A11) (Meyerhoff et al., 2014) and one is involved in Vitamin D synthesis (Lee et al., 2011).

Finally, eight of the top 100 genes we found to be up-regulated are odorant/olfactory receptor or related genes with fold-changes ranging 12–28 (p < 0.01). Differences in olfactory functioning and odorant identification or sensitivity with PTSD have been reported (Croy et al., 2010, Dileo et al., 2008, Hinton et al., 2004, Vermetten et al., 2007). Olfactory stimuli can trigger highly emotional memories and flashbacks (Chu and Downes, 2002, Kline and Rausch, 1985, Masaoka et al., 2012, Vermetten and Bremner, 2003, Willander and Larsson, 2006). Predator odors can induce long-lasting behavioral and physiological effects in rodents (Apfelbach et al., 2005, Fendt et al., 2003, Figueiredo et al., 2003, Takahashi, 2014). To the best of our knowledge these results are the first to demonstrate over-expression of odorant/olfactory receptor related genes with PTSD compared to resilience. Due to the sample size, however, independent replication is needed before concluding that odorant receptor genes are implicated in the pathogenesis of PTSD.

The small sample size is a significant limitation of this study. In addition, while similar, our groups were not perfectly balanced for gender and type of trauma. Other limitations include that we used blood cell gene expression status to explore possible molecular biology changes in PTSD patients where pathogenesis likely primarily involves disturbances of brain function. While studies have shown that peripheral blood expression levels of many genes were moderately correlated with expression levels of those genes in other tissues, including postmortem brain (Kohane and Valtchinov, 2012,Rollins et al., 2010,Sullivan et al., 2006,Woelk et al., 2011), caution is warranted in making conclusions. The absence of differences in methylation between PTSD and resilient controls is not consistent with some prior reports (Smith et al., 2011, Uddin et al., 2010). Mehta et al. (2013) reported methylation differences limited to a subgroup with child abuse which was not common in our participants and in fact was more common in the resilient group. However, it is possible that our failure to detect any DNA methylation differences may be due to the size of our samples.

In summary, we found that a number of genes including subsets related to immune function, brain and olfactory functioning to be significantly up-regulated in participants with PTSD compared to those who were resilient to similar levels of trauma, whereas, no significant differences in methylation were found. Presently the molecular basis of the structural and functional brain abnormalities and elevated risk for other psychiatric and medical conditions that have been observed with PTSD is not well understood. Converging results from studies including ours will continue to provide clues and further investigation is indicated.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Genome-wide gene expression study demonstrated eight odorant/olfactory receptor related genes were up-regulated with PTSD comparing to resilient controls.

Other up-regulated genes include those related to immune activation, the Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid A (GABAA) receptor, and vitamin D synthesis.

The up- or down-regulated gene expression appears not related to DNA methylation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the pilot program of Translational Technologies and Resources of Georgetown-Howard Universities Center of Clinical and Translational Sciences, NIH/NCATS UL1TR000101.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Andero R, Dias B, Ressler K. A Role for Tac2, NkB, and Nk3 Receptor in Normal and Dysregulated Fear Memory Consolidation. Neuron. 2014;83:444–454. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apfelbach R, Blanchard CD, Blanchard RJ, Hayes RA, McGregor IS. The effects of predator odors in mammalian prey species: a review of field and laboratory studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2005;29:1123–1144. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker DG, Nievergelt CM, O'Connor DT. Biomarkers of PTSD: Neuropeptides and immune signaling. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62:663–673. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Gusman FD, Charney DS. The development of a clinician-administered PTSD scale. J. Trauma. Stress. 1995;8:75–90. doi: 10.1007/BF02105408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boasso AM, Steenkamp MM, Nash WP, Larson JL, Litz BT. The Relationship Between Course of PTSD Symptoms in Deployed US Marines and Degree of Combat Exposure. J. Trauma. Stress. 2015;28:73–78. doi: 10.1002/jts.21988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu S, Downes JJ. Proust nose best: Odors are better cues of autobiographical memory. Mem. Cognit. 2002;30:511–518. doi: 10.3758/bf03194952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croy I, Schellong J, Joraschky P, Hummel T. PTSD, but not childhood maltreatment, modifies responses to unpleasant odors. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2010;75:326–331. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dileo J, Brewer W, Hopwood M, Anderson V, Creamer M. Olfactory identification dysfunction, aggression and impulsivity in war veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychol. Med. 2008;38:523–531. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fendt M, Endres T, Apfelbach R. Temporary inactivation of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis but not of the amygdala blocks freezing induced by trimethylthiazoline, a component of fox feces. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:23–28. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-01-00023.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo HF, Bodie BL, Tauchi M, Dolgas CM, Herman JP. Stress integration after acute and chronic predator stress: differential activation of central stress circuitry and sensitization of the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical axis. Endocrinology. 2003;144:5249–5258. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guffanti G, Galea S, Yan L, Roberts AL, Solovieff N, Aiello AE, Smoller JW, De Vivo I, Ranu H, Uddin M, Wildman DE, Purcell S, Koenen KC. Genome-wide association study implicates a novel RNA gene, the lincRNA AC068718.1, as a risk factor for post-traumatic stress disorder in women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38:3029–3038. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton DE, Pich V, Chhean D, Pollack M, Barlow DH. Olfactory-triggered panic attacks among Cambodian refugees attending a psychiatric clinic. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 2004;26:390–397. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge E, Brandstetter K, Moshier S, Pollack M, Wong K, Simon N. Broad spectrum of cytokine abnormalities in panic disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. Depress. Anxiety. 2009;26:447–455. doi: 10.1002/da.20564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollifield M, Moore D, Yount G. Gene expression analysis in combat veterans with and without post-traumatic stress disorder. Mol. Med. Rep. 2013;8:238–244. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2013.1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the national comorbidity survey. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1995;52:1048–1060. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline NA, Rausch JL. Olfactory precipitants of flashbacks in posttraumatic stress disorder: case reports. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 1985 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenen KC, Fu QJ, Ertel K, Lyons MJ, Eisen SA, True WR, Goldberg J, Tsuang MT. Common genetic liability to major depression and posttraumatic stress disorder in men. J. Affect. Disord. 2008;105:109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenen KC, Uddin M, Chang S, Aiello AE, Wildman DE, Goldmann E, Galea S. SLC6A4 methylation modifies the effect of the number of traumatic events on risk for posttraumatic stress disorder. Depress. Anxiety. 2011;28:639–647. doi: 10.1002/da.20825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohane IS, Valtchinov VI. Quantifying the white blood cell transcriptome as an accessible window to the multiorgan transcriptome. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:538–545. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DM, Tajar A, O'Neill TW, O'Connor DB, Bartfai G, Boonen S, Bouillon R, Casanueva FF, Finn JD, Forti G, Giwercman A, Han TS, Huhtaniemi IT, Kula K, Lean ME, Punab M, Silman AJ, Vanderschueren D, Wu FC, Pendleton N EMAS study group. Lower vitamin D levels are associated with depression among community-dwelling European men. J. Psychopharmacol. 2011;25:1320–1328. doi: 10.1177/0269881110379287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberzon I, King AP, Ressler KJ, Almli LM, Zhang P, Ma ST, Cohen GH, Tamburrino MB, Calabrese JR, Galea S. Interaction of the ADRB2 gene polymorphism with childhood trauma in predicting adult symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder. JAMA psychiatry. 2014;71:1174–1182. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logue MW, Baldwin C, Guffanti G, Melista E, Wolf EJ, Reardon AF, Uddin M, Wildman D, Galea S, Koenen KC. A genome-wide association study of post-traumatic stress disorder identifies the retinoid-related orphan receptor alpha (RORA) gene as a significant risk locus. Mol. Psychiatry. 2013;18:937–942. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masaoka Y, Sugiyama H, Katayama A, Kashiwagi M, Homma I. Slow breathing and emotions associated with odor-induced autobiographical memories. Chem. Senses. 2012;37:379–388. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjr120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta D, Klengel T, Conneely KN, Smith AK, Altmann A, Pace TW, Rex-Haffner M, Loeschner A, Gonik M, Mercer KB, Bradley B, Muller-Myhsok B, Ressler KJ, Binder EB. Childhood maltreatment is associated with distinct genomic and epigenetic profiles in posttraumatic stress disorder. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013;110:8302–8307. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217750110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyerhoff DJ, Mon A, Metzler T, Neylan TC. Cortical gamma-aminobutyric acid and glutamate in posttraumatic stress disorder and their relationships to self-reported sleep quality. Sleep. 2014;37:893–900. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neylan TC, Sun B, Rempel H, Ross J, Lenoci M, O’Donovan A, Pulliam L. Suppressed monocyte gene expression profile in men versus women with PTSD. Brain Behav. Immun. 2011;25:524–531. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nievergelt CM, Maihofer AX, Mustapic M, Yurgil KA, Schork NJ, Miller MW, Logue MW, Geyer MA, Risbrough VB, O’Connor DT, Baker DG. Genomic predictors of combat stress vulnerability and resilience in U.S. Marines: A genome-wide association study across multiple ancestries implicates PRTFDC1 as a potential PTSD gene. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;51:459–471. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollins B, Martin MV, Morgan L, Vawter MP. Analysis of whole genome biomarker expression in blood and brain. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2010;153:919–936. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusiecki JA, Byrne C, Galdzicki Z, Srikantan V, Chen L, Poulin M, Yan L, Baccarelli A. PTSD and DNA methylation in select immune function gene promoter regions: a repeated measures case-control study of US military service members. Front. Psychiatry. 2013;4 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusiecki JA, Chen L, Srikantan V, Zhang L, Yan L, Polin ML, Baccarelli A. DNA methylation in repetitive elements and post-traumatic stress disorder: a case-control study of US military service members. Epigenomics. 2012;4:29–40. doi: 10.2217/epi.11.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segman RH, Shefi N, Goltser-Dubner T, Friedman N, Kaminski N, Shalev AY. Peripheral blood mononuclear cell gene expression profiles identify emergent post-traumatic stress disorder among trauma survivors. Mol. Psychiatry. 2005;10:500–513. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AK, Conneely KN, Kilaru V, Mercer KB, Weiss TE, Bradley B, Tang Y, Gillespie CF, Cubells JF, Ressler KJ. Differential immune system DNA methylation and cytokine regulation in post-traumatic stress disorder. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2011;156:700–708. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan PF, Fan C, Perou CM. Evaluating the comparability of gene expression in blood and brain. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2006;141:261–268. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi LK. Olfactory systems and neural circuits that modulate predator odor fear. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2014;8 doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- True WR, Rice J, Eisen SA, Heath AC, Goldberg J, Lyons MJ, Nowak J. A twin study of genetic and environmental contributions to liability for posttraumatic stress symptoms. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1993;50:257–264. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820160019002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uddin M, Galea S, Chang SC, Aiello AE, Wildman DE, de los Santos R, Koenen KC. Gene expression and methylation signatures of MAN2C1 are associated with PTSD. Dis. Markers. 2011;30:111–121. doi: 10.3233/DMA-2011-0750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uddin M, Aiello AE, Wildman DE, Koenen KC, Pawelec G, de los Santos R, Goldmann E, Galea S. Epigenetic and immune function profiles associated with posttraumatic stress disorder. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:9470–9475. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910794107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Panhuys N, Le Gros G, McConnell M. Epigenetic regulation of Th2 cytokine expression in atopic diseases. Tissue Antigens. 2008;72:91–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2008.01068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermetten E, Bremner JD. Olfaction as a traumatic reminder in posttraumatic stress disorder: case reports and review. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2003 doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n0214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermetten E, Schmahl C, Southwick SM, Bremner JD. Positron tomographic emission study of olfactory induced emotional recall in veterans with and without combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 2007;40:8–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willander J, Larsson M. Smell your way back to childhood: Autobiographical odor memory. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2006;13:240–244. doi: 10.3758/bf03193837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woelk CH, Singhania A, Perez-Santiago J, Glatt SJ, Tsuang MT. The utility of gene expression in blood cells for diagnosing neuropsychiatric disorders. Int Rev. Neurobiol. 2011;101:41–63. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-387718-5.00003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie P, Kranzler HR, Poling J, Stein MB, Anton RF, Brady K, Weiss RD, Farrer L, Gelernter J. Interactive effect of stressful life events and the serotonin transporter 5-HTTLPR genotype on posttraumatic stress disorder diagnosis in 2 independent populations. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2009;66:1201–1209. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie P, Kranzler HR, Yang C, Zhao H, Farrer LA, Gelernter J. Genome-wide Association Study Identifies New Susceptibility Loci for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Biol. Psychiatry. 2013;74:656–663. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yehuda R, Cai G, Golier JA, Sarapas C, Galea S, Ising M, Rein T, Schmeidler J, Müller-Myhsok B, Holsboer F. Gene expression patterns associated with posttraumatic stress disorder following exposure to the World Trade Center attacks. Biol. Psychiatry. 2009;66:708–711. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zieker J, Zieker D, Jatzko A, Dietzsch J, Nieselt K, Schmitt A, Bertsch T, Fassbender K, Spanagel R, Northoff H. Differential gene expression in peripheral blood of patients suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. Mol. Psychiatry. 2007;12:116–118. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.