Abstract

Although evidence from human studies has long indicated the crucial role of the frontal cortex in speech production, it has remained uncertain whether the frontal cortex in nonhuman primates plays a similar role in vocal communication. Previous studies of prefrontal and premotor cortices of macaque monkeys have found neural signals associated with cue- and reward-conditioned vocal production, but not with self-initiated or spontaneous vocalizations (Coudé et al., 2011; Hage and Nieder, 2013), which casts doubt on the role of the frontal cortex of the Old World monkeys in vocal communication. A recent study of marmoset frontal cortex observed modulated neural activities associated with self-initiated vocal production (Miller et al., 2015), but it did not delineate whether these neural activities were specifically attributed to vocal production or if they may result from other nonvocal motor activity such as orofacial motor movement. In the present study, we attempted to resolve these issues and examined single neuron activities in premotor cortex during natural vocal exchanges in the common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus), a highly vocal New World primate. Neural activation and suppression were observed both before and during self-initiated vocal production. Furthermore, by comparing neural activities between self-initiated vocal production and nonvocal orofacial motor movement, we identified a subpopulation of neurons in marmoset premotor cortex that was activated or suppressed by vocal production, but not by orofacial movement. These findings provide clear evidence of the premotor cortex's involvement in self-initiated vocal production in natural vocal behaviors of a New World primate.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT Human frontal cortex plays a crucial role in speech production. However, it has remained unclear whether the frontal cortex of nonhuman primates is involved in the production of self-initiated vocalizations during natural vocal communication. Using a wireless multichannel neural recording technique, we observed in the premotor cortex neural activation and suppression both before and during self-initiated vocalizations when marmosets, a highly vocal New World primate species, engaged in vocal exchanges with conspecifics. A novel finding of the present study is the discovery of a subpopulation of premotor cortex neurons that was activated by vocal production, but not by orofacial movement. These observations provide clear evidence of the premotor cortex's involvement in vocal production in a New World primate species.

Keywords: marmoset, premotor, vocalization, wireless

Introduction

The neural substrates of speech production are believed to lie in distributed circuits in the frontal cortex of humans (Penfield and Roberts, 1959; Korzeniewska et al., 2011; Hickok, 2012; Bouchard et al., 2013; Chang et al., 2013; Behroozmand et al., 2015). However, it has remained uncertain whether the frontal cortex plays a similar role as humans in vocal communication in nonhuman primates. The primary animal models that have been used to study questions related to vocal control and learning at the single neuron level are songbirds because of their rich vocal behaviors that are readily observable in laboratory conditions (Doupe and Kuhl, 1999). There has been a paucity of studies in nonhuman primates on vocal production mechanisms, which is in large part due to technical difficulties in studying single neuron activity in vocalizing monkeys. Unlike songbirds, commonly used nonhuman species such as macaque monkeys vocalize little in captivity, especially when their body is restrained (often required for neurophysiological recordings). In some previous experiments, the investigators choose to train monkeys to vocalize on foods and other rewards (Coudé et al., 2011; Hage and Nieder, 2013). Although such approaches may allow an experimenter to elicit vocalizations from an animal, it leaves open questions on how much the neural signals observed are related to communicative behaviors as opposed to a learned association with rewards, therefore making interpretation of the frontal cortex data difficult.

Studies in nonhuman primates in the past several decades have provided conflicting results. For example, early studies showed that electrical stimulation of squirrel monkey's frontal cortex did not elicit vocalizations (Jürgens and Ploog, 1970) and lesions in macaque monkey frontal cortex had no effects on conditioned vocalizations (Sutton et al., 1974). More recently, neural recording studies in macaque monkeys showed increased prevocal activities in prefrontal and premotor cortex before conditioned, but not animal-initiated, vocalizations (Coudé et al., 2011; Hage and Nieder, 2013). The reward and conditioning paradigm used in these experiments complicated interpretations of the observations because the neural activity in frontal cortex has been shown to be susceptible to behavioral modifications (Kalaska et al., 1997; Brasted and Wise, 2004).

In recent years, a highly vocal New World primate, the common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus), has emerged as a promising model for studying these questions. Marmosets have a rich vocal repertoire and maintain frequent vocal exchanges among conspecifics even in captivity (Epple, 1968; DiMattina and Wang, 2006; Miller and Wang, 2006; Agamaite et al., 2015). Studies of immediate early gene expression suggested frontal cortex activities in marmosets during vocal production (Miller et al., 2010a; Simões et al., 2010). A recent neurophysiological study of marmoset frontal cortex observed motor-related changes in neural activity when animals engaged in antiphonal calling behaviors (Miller et al., 2015), but this study did not attempt to delineate whether these neural activities were specific to vocal production or if they may result from other nonvocal motor movements that involve similar motor end organs (e.g., orofacial movement).

In the present study, we used chronically implanted multielectrode arrays (Eliades and Wang, 2008a) and a wireless neural recording system (Roy and Wang, 2012) developed in our laboratory to study single neuron activity in the frontal cortex of marmosets while they roamed freely in recording cages and engaged in the antiphonal calling behavior (see Materials and Methods). A substantial number of neurons in premotor cortex were found to have either increased or decreased activities before or during vocal production. Furthermore, by using a licking behavior as a control for nonvocal orofacial movements, we were able to identify a subset of those neurons with activities associated exclusively with vocalization but not orofacial movement, as well as neurons showing different levels of activities to vocalization and orofacial movement. Our results provide clear evidence of the premotor cortex's involvement in vocal production during natural vocal behaviors in marmosets and suggest possible roles of frontal cortex in natural vocal communication.

Materials and Methods

Study design.

The present study took advantages of behavioral and neural recording techniques that we have pioneered in the past two decades to study behavioral and neurophysiological mechanisms underlying perception, production, and vocal communication in marmosets, as well as the extensive knowledge that we have accumulated on the marmoset's vocal repertoire and behaviors (Miller and Wang, 2006; Pistorio et al., 2006; DiMattina and Wang, 2006; Roy et al., 2011; Agamaite et al., 2015). The animals used in this study were born and raised in a breeding colony that we have maintained at Johns University School of Medicine since 1996. This study overcame three technical challenges in this line of research: (1) the ability to induce and observe repeatable natural vocal behaviors without subjecting marmosets to behavioral training in tasks involving in nonvocal motor behaviors (e.g., limb movement) and food rewards, which was achieved by developing the antiphonal calling vocal behavior in the laboratory condition (Miller and Wang, 2006; Miller et al., 2009, 2010b); (2) the ability to record chronically single neuron activity over a long period of time and in populations of neurons in the premotor cortex (Eliades and Wang, 2008a, 2008b); and (3) the ability to conduct neural recordings in freely roaming and naturally vocalizing marmosets via wireless neural recording techniques (Roy and Wang, 2012). With these technical advancements, it became possible to investigate neural mechanisms underlying natural vocal behaviors in freely moving and vocalizing marmosets. Some of the above-mentioned techniques have been used in a recent study of the vocalization-related activity in the front cortex of marmosets by Miller et al. (2015). In the following sections, we explain details of the reported experiments.

Vocal production behavioral experiments.

Marmosets frequently exchange “phee” calls, a long-distance contact call, in the wild or in captive colonies to identify themselves and to maintain contact. This vocal behavior is known as antiphonal calling (Miller and Wang, 2006). In previous studies, we showed that this behavior can be induced and observed in laboratory conditions (Miller and Wang, 2006, Miller et al., 2010b). In these experiments, a pair of marmosets was placed in two cages located on the two sides of the recording chamber and visually occluded by a curtain in the middle (Fig. 1A). Under such a condition, marmosets displayed the antiphonal calling behavior (Miller and Wang, 2006). Alternatively, a “virtual conspecific” (a computer-controlled, automated playback program) was used to replace one of the two animals to induce the antiphonal calling behavior in the other animal (Fig. 1A,B; Miller et al., 2009). We have shown that this playback system can induce the antiphonal calling behavior similar to that observed when two marmosets are engaged in vocal exchanges (Miller et al., 2009). We used this method in the present study to allow a better experimental control of the vocal production while conducting neural recordings. No other types of behavioral conditioning and training nor any food rewards were used to evoke vocalizations in these experiments. On a typical recording session, a marmoset (chronically implanted with a multichannel electrode array coupled with a wireless transmitter) was brought to the recording chamber from the breeding colony, engaged in antiphonal calling behavior with the computer-controlled “virtual conspecific,” and returned to its home cage after the recording experiment completed.

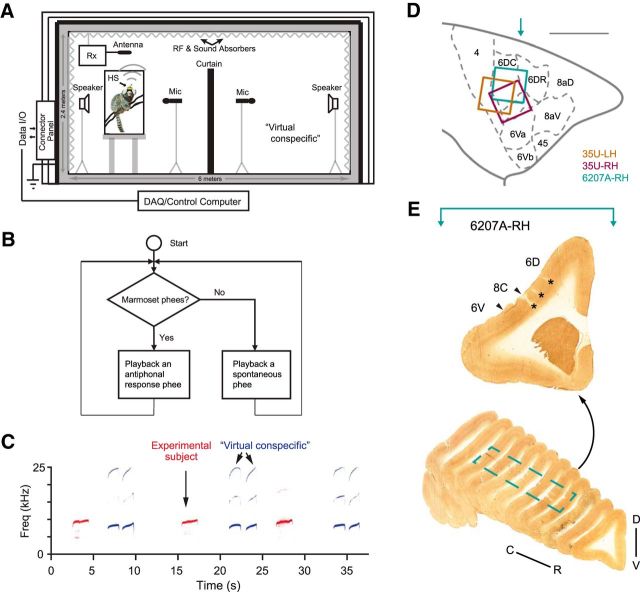

Figure 1.

Illustrations of the experimental setup and examples of recorded marmoset vocalizations. A, Schematic illustration of the recording chamber with acoustic and wireless neural recording systems. HS, Wireless head stage; Rx, receiver. The custom-built chamber was designed to isolate electromagnetic wave transmission and reflection, attenuate external sounds, and reduce internal sound reflection (Roy and Wang, 2012). In the vocal production condition, an experimental subject was placed in a plastic cage shown on the left side of the chamber. A wireless headstage (HS) was mounted on top of the subject's head and connected to an electrode array in the premotor cortex. A receiver (Rx) for the wireless system was placed above the cage. The subject's vocalizations were recorded by a microphone in front of the cage. During antiphonal calling behavior, a virtual conspecific was configured on the right side of the chamber. It replaced a real marmoset by a computer-controlled playback system and engaged the experimental subject in vocal exchanges (Miller et al., 2009). B, Computer algorithm controlling the virtual conspecific (Miller and Wang 2006; Miller et al., 2009). Once a phee call from the experimental subject was detected, a prerecorded phee of another marmoset in our colony was presented by the playback system with a delay (1–5 s, according to the statistics of antiphonal calling delays between pairs of marmosets). If there was no response from the experimental subject, another prerecorded phee was presented after a second delay (up to 60 s, according to the statistics of the time intervals between spontaneously produced phee calls). C, Spectrogram showing a series of antiphonal phee exchanges. In this example, the experimental subject made single-phrase phee calls and the virtual conspecific delivered two-phrase phee calls. D, Estimated electrode coverage areas for the three hemispheres (with Brodmann's areas marked accordingly). The area between 6DC and 6Va is 8C. The colored square is aligned with the outermost electrodes of the array. Locations of electrode arrays are estimated based on histology (6207A) and geometric measurements on the skull surface during implantation (with respect to the lateral sulcus) with a comparison with the marmoset brain atlas (Paxinos et al., 2012). Scale bar, 5 mm. The turquoise arrow indicates the approximate location of the example section in E. LH, left hemisphere; RH, Right hemisphere. E, Coronal sections from 6207A right hemisphere with cytochrome oxidase stain. Top, Example section marked with cortical regions (border indicated with arrowheads) and electrode locations (asterisks). The approximate location of the section with respect to the brain on the rostral–caudal axis is indicated by a turquoise arrow in D. Bottom, Series of sections from the frontal brain of 6207A with the border of the electrode coverage area marked (dashed line). D–V, Dorsal–ventral; C–R, caudal–rostral.

During a typical experiment session (∼45–90 min), after the experimental subject initiated a phee call, the virtual conspecific computer program played a phee call from a collection of prerecorded phees of another marmoset from our colony with a random delay between 1 and 5 s based on the statistics of the latency of natural antiphonal responses (Miller et al., 2010b). If the subject did not vocalize after a predetermined time period, the program would deliver another prerecorded phee call of that same marmoset with a certain delay based on the statistics of the time intervals between spontaneously produced phee calls (Miller et al., 2009). Playback vocalizations were delivered through a speaker amplifier (D-75A; Crown Audio) and a loudspeaker (M80; Cambridge Soundworks) located away from the subject and visually blocked by a cloth occluder.

In some of the experiment sessions, there was no virtual conspecific in the recording room and the subject spontaneously vocalized phee calls by itself. We refer to these sessions as “vocal alone” sessions and the antiphonal calling sessions described above as “vocal exchange” sessions. When the two sessions were recorded with same neurons, the vocal alone session was always conducted before the vocal exchange session. For the analysis in the vocal production condition, we grouped all calls (and corresponding neural responses) from the two types of sessions together (keeping their temporal order) and refer them as self-initiated calls. Prerecorded vocalizations used by the virtual conspecific computer program were used to evaluate the sensory responses of premotor neurons in the playback condition.

To control for motor movements generated by mouth and other organs in the absence of vocal production, we tested the experimental subject with a licking behavior in some sessions. For the licking behavior, a plastic feeding tube was inserted through a hole on the recording cage wall to deliver liquid food (a mixture of rice cereal, Similac, and strawberry flavor). The experimental subject (having ad libitum access to food within their home cages) came to the feeding tube spontaneously to receive liquid food. A custom-made lick detector was used to register the licking behavior when an infrared beam from the detector was interrupted by tongue and jaw movements (Remington et al., 2012). The duration of the liquid food delivery was controlled such that the licking behavior lasted approximately the average duration of a single-phrase phee call (1–2 s).

As described above, there were three experimental conditions in this study: (1) vocal production, in which a marmoset engaged in self-initiated calling; (2) playback, in which prerecorded marmoset phee calls were played to a marmoset (this is a control condition to test whether a neuron shows responses to the auditory input in the absence of vocal production); and (3) orofacial movement (licking), in which a marmoset licked liquid foods through a plastic feeding tube. This licking behavior was used as a control condition because it generated mouth movement but without vocal production. Licking involves similar musculature (e.g., jaw, tongue) that is used in vocal production. All three conditions were tested within a day for each neuron.

Marmoset vocalizations were recorded by directional microphones (ME66; Sennheiser) and synchronized with neural recordings. Acoustic signals were amplified (Model 302 dual microphone preamp; Symmetrix) and then digitized at 50 kHz with a data acquisition card (PCI-6052E; National Instruments) on the same computer used for neural recording.

Animal preparation and neural recording.

Two adult marmosets (35U and 6207A, both female) were implanted with 16-channel multielectrode arrays (Eliades and Wang, 2008a; Warp-16; Neuralynx), including both hemispheres of marmoset 35U and the right hemisphere of marmoset 6207A. Details about the array implantation and the recording techniques have been described previously (Eliades and Wang, 2008a; Roy and Wang, 2012). Briefly, marmosets were implanted with a head cap using standard surgical procedures (Lu et al., 2001). A craniotomy was performed above the premotor cortex of marmosets, identified by anatomical landmarks with respect to the lateral sulcus (Burish et al., 2008; Burman et al., 2008). The array was sealed by SILASTIC (QWIK-SIL; WPI) and fixed to the skull with dental acrylic. Each array housed 16 tungsten electrodes (impedances 2–5 MΩ; FHC), each of which was individually movable by a pushing device (Neuralynx; Eliades and Wang, 2008a). This movability helped to optimize recorded signals and allowed the search for single neurons in each electrode. All experimental procedures were approved by the Johns Hopkins University Animal Care and Use Committee in compliance with the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health.

Neural signals were transmitted by a wireless head stage (W16; Triangle Biosystems) connected to the electrode array, mounted on top of the marmoset's head, and protected by a polycarbonate cap (Roy and Wang, 2012). The array (∼1 g), wireless head stage (∼4 g), and protection cap (∼7 g) were relatively lightweight and did not interfere with marmosets' vocalizations or movements. Recordings were performed in a custom-built RF/EMI and acoustic shielded chambers (6 × 3.7 × 2.4 m; Fig. 1A), which reduces interference of the wireless recording and attenuates unwanted acoustic noises (Roy and Wang, 2012). The marmoset moved freely in a Plexiglas cage with nylon mesh walls (60 × 41 × 30 cm) with the receiver of the wireless neural recording system located above it.

Raw neural signals were band-pass filtered (300–6000 Hz) and amplified by the wireless head stage and preamplifiers (Lynx-8; Neuralynx) and then digitized at 20 kHz sampling rate with a data acquisition card (PCI-6071E; National Instruments) on a computer. A custom-written Matlab program was used to acquire, view, and store the data. To synchronize recordings of vocalizations and neural signals in the two data acquisition cards (PCI-6052E and PCI-6071E), a periodic pulse train (every 2 s) was sent to both cards and logged as an additional channel in both vocal and neural recording data files. After finishing all recording sessions at a particular recording depth(s), electrodes were advanced to deeper locations to search for new units.

At the end of all experiments, electrolytic lesions were made by passing a small current through a subset of the recording electrodes (10 μA, 10 s). The animals were anesthetized with ketamine and then killed by an injection of pentobarbital sodium. Perfusion was done transcardially with phosphate-buffered solution and 4% paraformaldehyde. Marmoset 6207A's brain was sectioned in coronal plane and stained for cytochrome oxidase. Images of the stained sections were acquired and processed by a Neurolucida system.

Data analysis.

Spikes were sorted offline based on a template matching method by a multichannel sorting program written in Matlab (Eliades and Wang, 2008a; Roy and Wang, 2012). In brief, the initial spike detection thresholds were set at least twice as large as the SD of the background noise. Spike templates were first created by two manually adjusted time–voltage windows and then calculated by averaging spike waveforms passing through these two windows to generate a 12-point template. The templates were then fixed and used to extract spike waveforms and timestamps. Single units were classified as those with signal-to-noise ratio >13 dB and a percentage of interspike interval <1 ms being smaller than 1%. Units on the same electrode from the same day's sessions were considered to be the same units.

Vocalizations were detected in the recording data files using a band-limited energy detection algorithm and verified manually. Timing of vocalizations and spikes were adjusted and synchronized according to the periodic pulse trains logged in both recording files to eliminate potential clock drift on the two data acquisition cards.

To analyze single unit activities in each experimental condition (vocal production, playback, and orofacial movement), spike timing was aligned with the onset of vocal production, the playback of vocalizations, or licking (i.e., event onset). Firing rates were calculated using 100 ms bins. Four analysis windows were used to characterize activities in different experimental conditions (time relative to event onset): [−2.5, −0.5] sec (spontaneous activity), [−0.5, 0] sec (pre-event activity), [0, 1.0] sec (activity after event onset), and [−0.3, 0.3] sec (activity around event onset), referred to as the spont-, pre-, post-, and peri-windows, respectively (Fig. 2B,D,F). Neurons are excluded from analysis if there were <10 events in any of the experimental conditions.

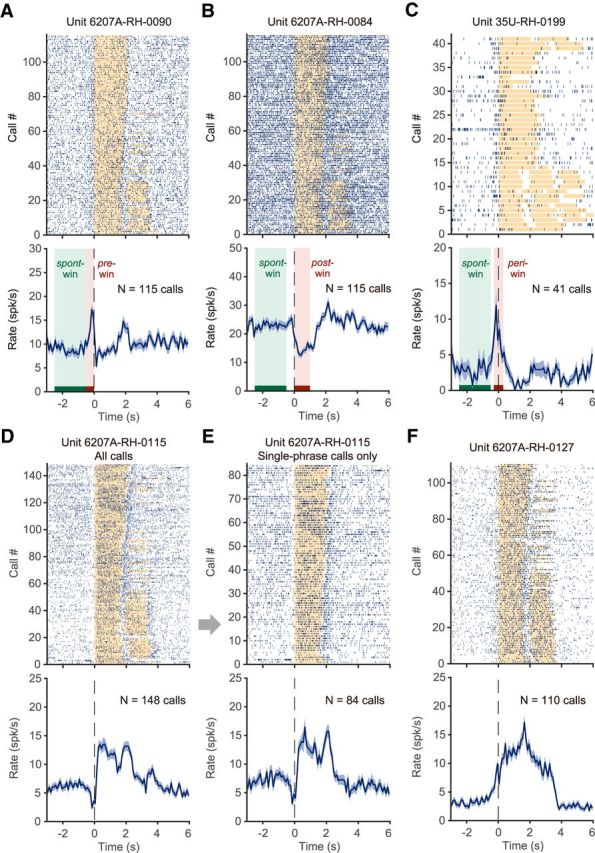

Figure 2.

Neural activity in the vocal production condition: examples of individual neurons for individual recording sessions. A, Neuron showing increased activity before vocal onset. Top, Each vertical line indicates a spike. Spike timing is aligned to the vocal onset. Orange bars indicate the duration of phee call phrases. Some of the calls had two phrases, which are shown as two bars in a row. In general, subjects tended to make multiphrase phee calls at the beginning of an experimental session and were more likely to produce single-phrase phee calls toward the end. Bottom, Firing rate shown as mean ± SEM. N indicates the number of calls. B, Neuron showing decreased activity during vocal production. This neuron was recorded in the same vocal production session as the neuron in A. C, Neuron showing increased activity near the vocal onset time. Three analysis windows are used to capture neuronal activities as in these examples: pre-, post-, and peri- windows, indicated by a red bar and a pink-shaded area (A–C). The spont-window used in analysis is indicated by a green bar and shaded area (A–C). D, Neuron showing decreased activity before vocal onset and increased activity during vocal production. E, Same neuron in D, with only single-phrase phee calls included. A clear activation is also seen after the end of the vocal production. F, Neuron showing strong activation both before and during vocal production.

For vocal production or orofacial movement, a neuron was determined to have vocalization- or orofacial-movement-related activities if firing rates were significantly different in one or more of the pre-, post-, and peri-windows compared with the spont-window. For playback of vocalizations, a neuron's response was compared between the post- and spont-windows. Wilcoxon's signed-rank test was used for comparison of neural activities between different analysis windows. Significance was determined if p < 0.05. For comparisons of each neuron's activity between experimental conditions, data used in analysis were collected within a single day.

We used z-scores to normalize firing rates and generate population average of neural activities. Firing rates were first subtracted by the mean firing rate in the spont-window and then divided by the SD of the firing rate in the spont-window. Using z-score enabled the comparison of neural responses under the three different experimental conditions across single neurons with different spontaneous firing rates. For population analysis regarding average activity across neurons, data were from multiple days.

Results

Characterization of neural activities in premotor cortex associated with vocal production

Neural activities in premotor cortex were studied in three hemispheres of two marmosets while the subjects produced self-initiated vocalizations (Fig. 1A,B; see Materials and Methods). Figure 1C shows the spectrogram of exemplar phee calls from one antiphonal calling session. Each phee vocalization is composed of 1–4 phrases. Phees from the experimental subject in Figure 1C had only one phrase and phees from the virtual conspecific (playback) had two phrases. In all cases, the animals vocalized voluntarily without any food or other rewards and were not conditioned by any motor tasks. The experimental subject was chronically implanted with a 16-channel, individually movable electrode array coupled with a wireless head stage (see details in the Materials and Methods). Neurophysiological recordings were made from the frontal cortex of marmosets while the animals vocalized within a custom-built RF/EMI and acoustic isolation chamber (Fig. 1A) using techniques developed in our laboratory (Eliades and Wang, 2008a; Roy and Wang, 2012).

To distinguish neural activities specifically or exclusively related to vocal production from those associated with sensory responses or orofacial movements (without vocal production), we also studied the activities of the same neuron in two control conditions: during playbacks of marmoset vocalizations and while animals were engaged in a licking behavior (to generate orofacial movements without vocal production). The three experimental conditions are referred to as vocal production, playback, and orofacial movement, respectively. In total, 606 single neurons were recorded in the vocal production condition. Table 1 lists the number of neurons from each hemisphere under each experimental condition during which multiple trials were recorded in each neuron. The recording sites most likely span the dorsal premotor area (BA6D) and also covered a small portion of the primary motor area (BA4) and part of area BA8C and BA6V (Fig. 1D,E; Burish et al., 2008; Burman et al., 2008, 2014a, 2014b, 2015; Paxinos et al., 2012; Hashikawa et al., 2015). Here, “premotor cortex” is used to refer to the general location of the neurons recorded in the reported experiments.

Table 1.

Number of recorded neurons in each hemisphere for each experimental condition

| Animal ID–hemisphere | Total | Tested vocal | Tested playback | Tested orofacial | Tested vocal, playback, and orofacial |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 35U-LH | 274 | 274 | 113 | 0 | 0 |

| 35U-RH | 205 | 205 | 193 | 178 | 178 |

| 6207A-RH | 127 | 127 | 89 | 89 | 89 |

| 35U-RH and 6207A-RH | 332 | 332 | 282 | 267 | 267 |

| All 3 hemispheres | 606 | 606 | 395 | 267 | 267 |

LH, left hemisphere; RH, Right hemisphere.

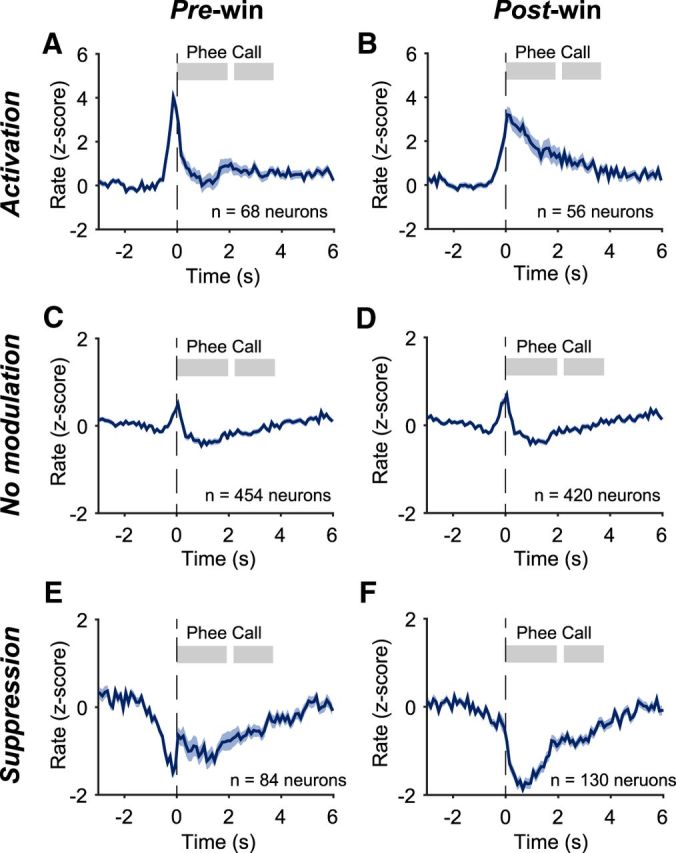

To analyze the neural activity before and during each vocalization, we aligned the recorded neural signals by the onset of each call. Figure 2 shows firing patterns of several example neurons recorded in the vocal production condition that had significant activity within any of the pre-, post-, and peri-windows (compared with spont-window, see Materials and Methods). For the neuron shown in Figure 2A, a total of 115 calls were made by the subject (6207A). In the early period of the session, the subject mostly made two-phrase phee calls and toward the end it made more single-phrase phees. More spikes occurred before vocal onset compared with those within the spont-window (Fig. 2A). Other examples show a variety of responses, including suppression in the post-window (Fig. 2B), activation in the peri-window (Fig. 2C), suppression in the pre-window plus activation in the post-window (Fig. 2D), and activation in both pre- and post-windows (Fig. 2F). Figure 2E shows a subset of data from Figure 2D with only single-phrase phee calls. Figure 3 shows population-averaged normalized firing rates of neurons with different types of modulations (activation, no modulation, or suppression) in the pre- and post-window. Of 606 neurons recorded in the vocal production condition, 43.6% (264/606) showed responses (activation or suppression) in the pre- and/or post-window (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p < 0.05, similarly hereafter). Before vocal onset (pre-window), 68 neurons showed activation (Fig. 3A) and 84 neurons showed suppression (Fig. 3E) regardless of modulation type after vocal onset (post-window). During vocal production (post-window), 56 neurons showed activation (Fig. 3B) and 130 neurons showed suppression (Fig. 3F) regardless of modulation type before vocal onset (pre-window). Of the entire population, ∼50.2% (304/606) showed vocalization-related activities (any modulation in one or more of the three analysis windows: pre-, post-, and peri-windows). A subset of these neurons (78/304 or 25.7%, including 37 for activation and 41 for suppression) showed modulation only in the pre-window, but not in the post-window.

Figure 3.

Neural activity in the vocal production condition: population average across neurons with different types of modulations in the pre-window and post-window. A, Population-averaged normalized firing rates of neurons showing activation in the pre-window regardless of modulation type in other windows (mean ± SEM). Firing rates are normalized as z-score for each neuron by the baseline firing rate in the spont-window and then averaged across the neurons. The number of neurons in the population is indicated by n. The shaded bars indicate the average durations of each phee call phrase. C, E, Same format as A for groups of neurons with no modulation (C) and suppression (E) in the pre-window. B, D, F, Same format as A for groups of neurons with activation (B), no modulation (D), and suppression (F) in the post-window.

A previous study reported sensory responses to acoustic stimulation in premotor cortex of macaque monkeys (Graziano et al., 1999). To sort out whether there was a sensory component in the neural activities that we observed during vocalizations, we recorded neural firing when a marmoset heard playbacks of phee calls from the virtual conspecific in a subset of neuron samples (395/606). Only 19 neurons showed significant activities during playback of vocalizations (comparing activities between the post- and spont-windows) regardless of whether they have activities in vocal production condition. We will exclude the neurons with playback activities in further analysis delineating motor-related activities.

Delineation of neuronal functions for vocal production and orofacial movement

A major question that we asked in the present study was whether the observed vocalization-related activities were associated exclusively with vocal production or if they were also involved in other nonvocal motor outputs as well. To investigate this, we engaged marmosets in a licking behavior in which they licked for food from a feeding tube because mouth movement was most directly linked to vocal production. Similar mouth, facial, and laryngeal muscles are presumably involved in the licking and swallowing movement as in vocal production. We recorded single neuron's responses during licking behavior (to be referred to as the orofacial movement condition) in two hemispheres (marmosets 35U right hemisphere, 6207A right hemisphere; Fig. 4, Table 1) and compared them with those recorded in vocal production condition. Orofacial-movement-related activities are defined as either activation or suppression or both in one or more of the three analysis windows (pre-, post-, or peri-windows) in the orofacial movement condition compared with the spont-window. When contrasted to orofacial movement, single neurons activities are expected to fall into one of the following types: (1) those modulated by vocal production only (referred to as “vocal-only” neurons), (2) those modulated by both vocal production and orofacial movement (referred to as “vocal-orofacial” neurons); (3) those modulated by orofacial movement only (referred to as “orofacial-only” neurons); and (4) those with no modulation in either condition. Indeed, we found subsets of neurons in all four categories and illustrate these scenarios in Figure 4A. Of the 267 neurons that we tested in the vocal production, playback, and orofacial movement conditions, 255 neurons (95.5%) had no playback activity (Fig. 4A). Among these 255 neurons, 23 neurons (9.0%) showed modulated activities only in the vocal production condition (vocal-only neurons), 138 neurons (54.1%) showed modulated activities in both vocal production and orofacial movement conditions (vocal-orofacial neurons), and 73 neurons (28.6%) showed modulated activities only in the orofacial movement condition (orofacial-only neurons). The rest of the 21 neurons (8.2%) showed no modulated activities. The firing patterns of the four neuronal categories are described below.

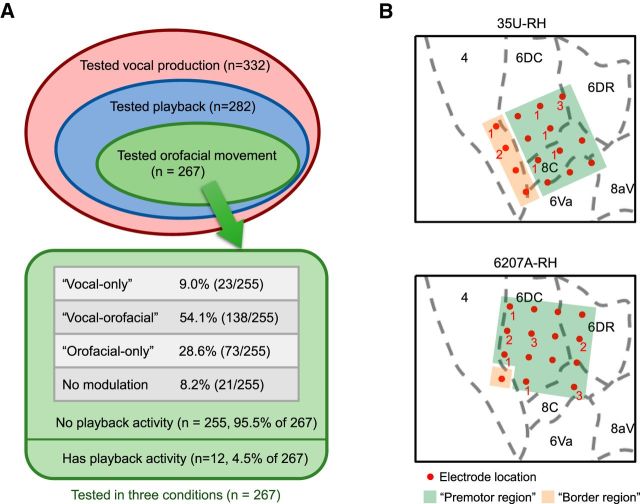

Figure 4.

Summary of neuron distributions in different experimental conditions and response categories. A, Total of 332 single neurons were tested in the vocal production condition from marmosets 35U right hemisphere and 6207A right hemisphere (Table 1). A subset of these neurons (282/332) were also tested in the playback condition. A further subset of those neurons (267/282) were tested in the orofacial movement condition (licking), as illustrated by the Venn diagram. A total of 255 of the 267 neurons tested in all three conditions showed no responses to the playback vocalizations and were classified into four categories (vocal-only, vocal-orofacial, orofacial-only, and no modulation). B, Estimated electrode locations (marked by red dots) of the arrays implanted on two hemispheres (top, 35U right hemisphere; bottom, 6207A right hemisphere) are overlaid on a published marmoset brain atlas (Paxinos et al., 2012). Recordings were made from 15 of 16 electrodes in each array (one electrode in each array was used as the reference and is not marked). The number next to each red dot indicates the number of vocal-only neurons found at that electrode location (no number shown if none was found). Recording locations in premotor region are marked by green-shaded area and those in the border region are marked by yellow-shaded area. Of 255 neurons recorded from both hemispheres, 213 were from the premotor region and 42 were from the border region. The number of neurons in each of the four categories (vocal-only, vocal-orofacial, orofacial-only, and no modulation) are 20 (9.4%), 116 (54.5%), 57 (26.8%), and 20 (9.4%) for the premotor region and 3 (7.1%), 22 (52.4%), 16 (38.1%), and 1 (2.4%) for the border region, respectively.

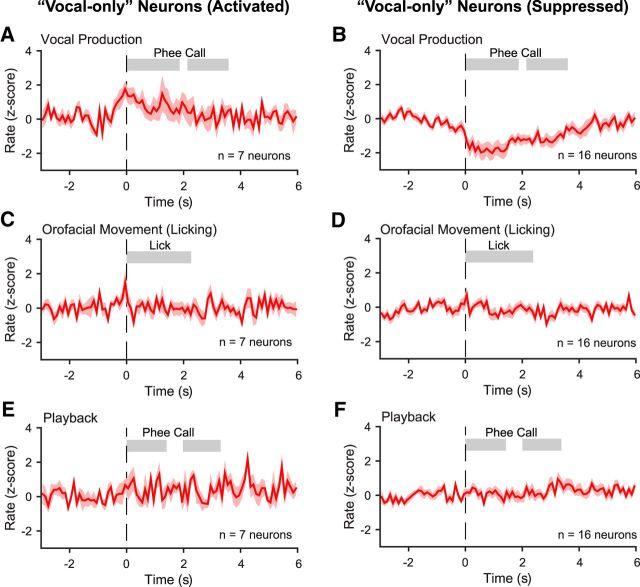

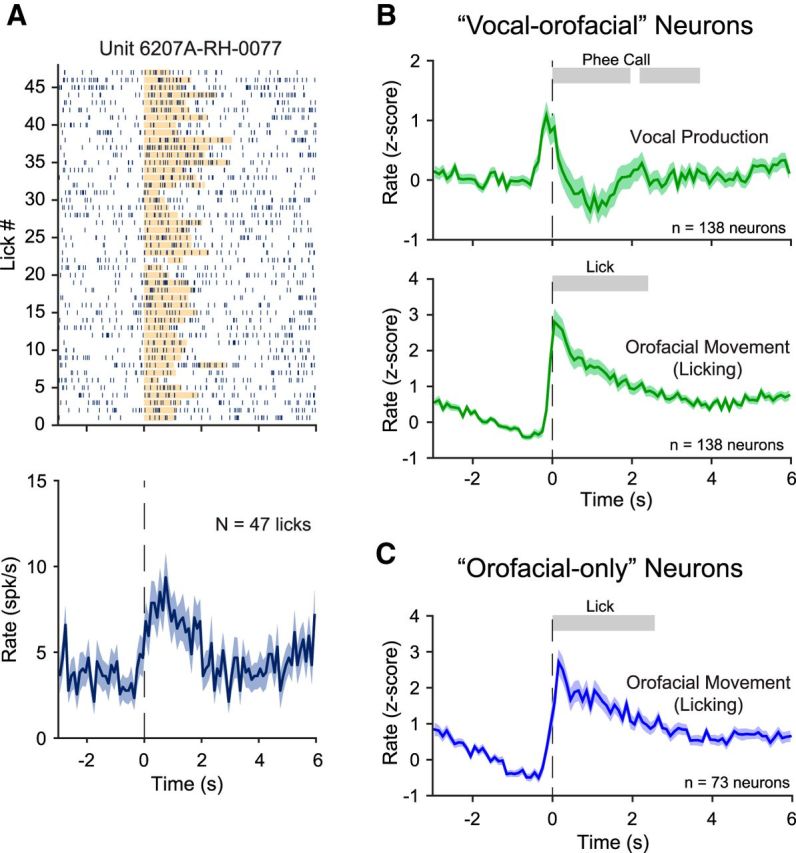

Vocal-only neurons may be considered as the candidate neurons responsible for initiating and controlling vocal productions because their activities are specific to vocal production. Figure 5 shows population-averaged normalized firing rates of the vocal-only neurons in each experimental condition. One-third of these neurons showed activation (Fig. 5A) and two-thirds showed suppression (Fig. 5B) in the vocal production condition, but they did not show modulated activities in the orofacial movement condition (Fig. 5C,D) or in the playback condition (Fig. 5E,F). Many more neurons showed modulated activities in both the vocal production and orofacial movement conditions. Figure 6A illustrates a neuron with significant orofacial-movement-related activities. This neuron showed increased firing while the animal was licking. Figure 6B shows population-averaged normalized firing rates of the vocal-orofacial neurons. Because this group of neurons showed modulated activities in both the vocal production (Fig. 6B, top) and orofacial movement (Fig. 6B, bottom) conditions, their role in vocal production cannot be specifically determined with these observations. Because the execution of vocal production and other orofacial movement engage similar musculature and the corresponding control signals likely arise from shared neural circuits, it is not surprising that a large proportion of neurons fell into this category. Finally, Figure 6C shows population-averaged normalized firing rates of the orofacial-only neurons, which are likely not involved in vocal production. The data shown in Figures 5 and 6 illustrate the importance of evaluating neural activity in both the vocal production and orofacial movement conditions, which has not been shown in previous studies.

Figure 5.

Population-averaged normalized firing rates (z-score, mean ± SEM) of the vocal-only neurons in each of the three experimental conditions. A, B, Vocal production. C, D, Orofacial movement (licking). E, F, Playback. The vocal-only neurons are separated into two groups, activated (A, C, E) and suppressed (B, D, F) in the vocal production condition. The shaded bars indicate the average durations of each phee call phrase (A, B, E, F) or averaged duration of the licking (C, D).

Figure 6.

Neural activities related to orofacial movement (licking). A, Example neuron showing increased activity during orofacial movement (licking). The orange bar in the raster plot indicates the duration of licking. B, Population-averaged normalized firing rates (z-score, mean ± SEM) of the vocal-orofacial neurons in two experimental conditions, vocal production (top) and orofacial movement (licking; bottom). The shaded bars indicate the average durations of each phee call phrase (top) or averaged duration of the licking (bottom). C, Population-averaged normalized firing rates (z-score, mean ± SEM) of the orofacial-only neurons in orofacial movement (licking) condition. The shaded bar indicates the average duration of the licking.

The vocal-orofacial neurons represent about half of neurons within the four categories (Fig. 4A), but they may not be a homogeneous population. To further delineate potential roles of vocal-orofacial neurons in vocal production, we compared the activities between vocal production and orofacial movement conditions for each neuron in this category (Fig. 7, green markers). Because whenever an animal vocalized, the action was always accompanied by orofacial movements, if the same network of neurons were responsible for generating vocalizations and orofacial movements, then one would expect that the activities of the vocal-orofacial neurons should be positively correlated between the vocal production and orofacial movement conditions (i.e., distributed on the upper right and lower left quadrants on the plots in Fig. 7). Because the exact muscles and their specific movements are likely different in these two behaviors, one would not expect a tight correlation along the diagonal line of these plots. However, if the vocal-orofacial neurons were sampled from more than one neuronal networks that play different roles in generating vocalizations and orofacial movements (and other motor functions), then their activities should not be correlated between the vocal production and orofacial movement conditions (these appear scattered in Fig. 7).

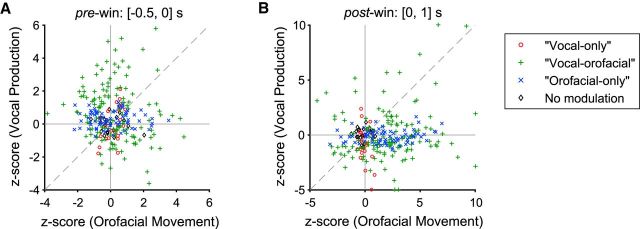

Figure 7.

Comparisons of the normalized firing rates (z-score) between vocal production and orofacial movement conditions. The comparisons are made for the four categories of neurons, respectively, as defined in Figure 4 in two analysis windows: pre-window (A) and post-window (B). y-axis is the vocal production condition; x-axis is the orofacial movement (licking) condition. A few data points with z-scores outside of the [−5,10] range are plotted on the border of the axes.

A close examination of Figure 7 shows that a subset of vocal-orofacial neurons exhibit correlated activities. However, as a whole (Fig. 7, green markers), the activity in the vocal production condition cannot be predicted by the activity in the orofacial movement condition (r2 = 0.015, p = 0.15 in Fig. 7A; r2 = 0.023, p = 0.07 in Fig. 7B). Interestingly, there is a trend of more vocal activation of the vocal-orofacial neurons in the pre-window (Fig. 7A, 81 of 138 neurons, sign test p = 0.050, Z = 1.96, median z-score: 0.45), but vocal suppression occurred for the majority of neurons in this category in the post-window (Fig. 7B, 87 of 138, sign test p = 0.0029, Z = −2.98, median z-score: −0.61). In addition, orofacial activity of the vocal-orofacial neurons in the post-window is strongly biased toward activation (Fig. 7B, 108 of 138, sign test p = 5.6 × 10−11, Z = 6.55, median z-score: 2.09). These data suggest that the premotor area of the marmosets is composed of multiple neuronal networks that are involved in generating various motor behaviors including vocal production. As expected, neurons categorized as vocal-only or orofacial-only only exhibit modulated activity along one axis when their activities in the vocal production and orofacial movement conditions are compared (Fig. 7).

In Figure 4B, we overlaid the estimated locations of recording electrodes locations on the marmoset brain atlas (Paxinos et al., 2012) for the two hemispheres in which all three conditions were tested. The majority of electrodes are located in the premotor region (Brodmann's areas 6D, 6V, and 8C). A small subset of electrodes on the caudal side of the array is possibly located in the primary motor cortex (Brodmann's area 4) near the border between primary motor and premotor cortices (referred to as the border region). Based on Figure 4B, we calculated distributions of neurons in four response categories for the premotor region and border region, respectively. Forty-two of 255 neurons were recorded from the border region. The majority of neurons (213 of 255) were recorded from the premotor region, including 20 of 23 vocal-only neurons. Therefore, the major conclusions of this study regarding the premotor cortex are well supported by the data. Interestingly, as detailed in the legend to Figure 4, there appear to be a noticeably greater proportion of orofacial-only neurons in the border region (38.1%, 16/42 neurons) than the premotor region (26.8%, 57/213 neurons) and a smaller proportion of “no modulation” neurons in the border region (2.4%, 1/42 neurons) than the premotor region (9.4%, 20/213 neurons).

Discussion

Comparison with previous studies

Earlier studies in nonhuman primates concluded that cingulate cortex and supplementary motor cortex played important roles in voluntary initiation of vocalization (usually conditioned by sensory cues; Kurata and Tanji, 1986; West and Larson, 1995), whereas midbrain structures such as periaqueductal gray are crucial for innate vocalizations (Jürgens and Ploog, 1970; Sutton et al., 1974; Jürgens, 2002). These studies suggested that the frontal cortex of nonhuman primates is dispensable or at least not critical for vocal production, which stands in sharp contrast to the well documented critical role of human frontal cortex in speech production. A recent study suggested a “Broca's area” analog in macaques (Petrides et al., 2005). Local field potential recordings suggested that premotor cortex of macaques is modulated during trained vocal production (Gemba et al., 1995, 1999). Two recent physiological studies in macaques showed vocalization-related activity (before or during vocal production) in the premotor and prefrontal cortices during conditioned but not self-initiated vocalizations (Coudé et al., 2011; Hage and Nieder, 2013). In the study by Coudé et al. (2011), vocalizations were elicited by food rewards, whereas in Hage and Nieder's (2013) study, macaques were trained to vocalize with a visual cue and rewarded with foods as well. The previous studies in Old World monkeys have provided useful information about possible roles of the prefrontal cortex in vocal production, but also raised questions as to whether the observed neural activity during conditioned or reward-elicited vocalizations was specifically associated with vocal communication. Because neural activity in the premotor areas is known to be plastic through adaptation and learning (Kalaska et al., 1997, 1998; Brasted and Wise, 2004; Schwartz et al., 2004), it is not clear whether the observed neural activities in the studies by Coudé et al. (2011) and Hage and Nieder (2013) were specifically attributed to vocal production or induced by the association with cues and rewards. In fact, previous studies have demonstrated that neural representation of muscle activities were different when monkeys was freely moving versus performing a trained motor task (Jackson et al., 2007).

To address these questions, one needs to study cortical activities in animals that vocalize naturally in a communicative context such as the present study and a recent study by Miller et al. (2015) in which neural activity in the frontal cortex of marmosets were studied during antiphonal calling natural behaviors. The recording locations of Miller et al. (2015) study appeared more anterior than those in our study (cf. our Fig. 1D and Fig. 1C of Miller et al. (2015)). The Miller et al. (2015) study reported 47.3% of 188 neurons of sampled neurons with activities related to vocal production (before or during vocalization). A similar proportion of neurons with such activities (modulation in the pre- or post-window) were found in our study (43.6% of 606 neurons, see Results and Fig. 3). A crucial step that we took in the present study was to compare a neuron's activities during natural vocal production and orofacial movements, which allowed us to delineate neural activities specifically associated with vocal production. We were able to identify 9.0% of neurons in our samples that were activated only by vocal production, but not by orofacial movements (Figs. 4, 5). Our study provides for the first time clear evidence of vocal-only neurons in the premotor cortex of nonhuman primates.

Although there could be species-specific differences in cortical organizations between New World and Old World monkeys, the different results between marmoset and macaque studies may result from fundamentally different behavior paradigms used in these studies. Due to technical difficulties in performing neural recordings from freely moving animals, the experiments in nonhuman primates conducted in the past ∼40 years have almost exclusively been performed on chair-restrained animals. Such an approach has prevented studying vocalization-related neural activity in a communicative context. As a result, experimenters either used electrical stimulation (Jürgens and Ploog, 1970; Jürgens, 1974; Jürgens, 1976; Jürgens and Zwirner, 2000) or behavioral training with food rewards (Coudé et al., 2011; Hage and Nieder, 2013) to induce vocalizations. Studies using small-bodied New World monkeys have overcome these obstacles by recording from freely moving animals during natural vocalizations (Grohrock et al., 1997; Eliades and Wang, 2008b; Roy and Wang, 2012; Miller et al., 2015). In addition to the difference in behavioral paradigms, the difference in cortical regions studied may also contribute to the discrepancy between the present marmoset study (dorsal premotor cortex) and previous macaque studies (ventrolateral premotor and prefrontal cortex) by Coudé et al. (2011) and Hage and Nieder (2013).

Although we have demonstrated neural activities associated with vocal production, their relationships with muscle activities, as measured by EMG of related vocal organs, during vocalizing or licking behaviors have yet to be established. In addition, in the playback condition, prerecorded phee calls from other marmosets in our colony were used to evaluate a neuron's sensory responses. Although the acoustics of these phee calls are quantitatively different from those of the experimental subject (Miller et al., 2010b; Miller and Wren Thomas, 2012; Agamaite et al., 2015), there has been no evidence to indicate that listening to an animal's own vocalization evokes significantly different neural responses than those evoked by other marmosets' vocalizations in auditory or frontal cortex other than the differences caused by the acoustics. In some other animal species, such as songbirds, playback of the animal's own songs evokes markedly different neural responses than those evoked by other animals' songs (Margoliash and Konishi, 1985). The playback condition in the present study leaves open the question of whether a marmoset's own vocalizations would evoke fundamentally different sensory responses in the premotor cortex than those by vocalizations of conspecifics.

Potential roles of vocal-only and vocal-orofacial neurons in vocal production

One of the most interesting findings in this study is the discovery of vocal-only neurons in the premotor cortex of marmosets, which provides crucial evidence for the involvement of this cortical area in voluntary vocal production. We propose two possible roles of the vocal-only neurons. First, the activity of these neurons may represent control signals for organs that are involved in vocal production, but not in other orofacial movements such as licking (e.g., particular muscles in the larynx). Second, their activity may represent upstream control signals for the initiation and production of vocalization instead of detailed motor plans for each end organ. One would expect that the neurons carrying detailed motor plans for generating vocalizations should be partially activated during licking because both behaviors are accompanied by mouth and tongue movements, among other muscles. It is possible that a higher (more upstream) center for vocal control would contain a higher proportion of vocal-only neurons than that found in premotor cortex.

We tested vocal production, playback, and orofacial movement conditions in recordings from two hemispheres. As shown in Figure 4B, the majority of electrodes were located within the premotor areas, but a small subset may fall into primary motor cortex. Because the four categories of neurons analyzed in our study were mostly from premotor areas (Fig. 4B), future experiments are needed to determine how these categories vary between the premotor and primary motor cortices. Conversely, within motor cortices, somatotopic representations of orofacial regions are located in the ventral area (Burish et al., 2008; Burman et al., 2008, 2015). Our observations of vocal-only and vocal-orofacial neurons in dorsal premotor cortex suggest that vocalization related motor control may not be limited to the orofacial regions identified by electrical stimulation in anesthetized marmosets (Burish et al., 2008; Burman et al., 2008). Future studies will further delineate functional differences between frontal regions.

The fact that the vocal-orofacial neurons represent a large proportion of sampled neurons suggests that the neuronal network in premotor or primary motor cortex controlling vocal production may be built upon or shared with neural structures controlling other orofacial movements engaging the same musculature. This finding has important implications for neural circuits underlying vocal control in the frontal cortex. Because it has been shown that motor control of individual muscles undergoes plasticity through development and adaptation, there is a potential of the flexibility in vocal control in marmosets. Furthermore, this finding suggests that vocal control is not directed by an exclusive or specialized circuit in the primate premotor cortex, unlike some brain structures for song production in songbirds (e.g., HVC, area X in zebra finch; Nottebohm and Arnold, 1976; Wade and Arnold, 2004). The vocal control by the primate frontal cortex may follow general principles found in other modalities of motor control. It has been shown that, in human motor cortex, phonations of different phonemes evoke activation of certain motor cortical regions that map to articulators needed for that phonation (Bouchard et al., 2013; Bouchard and Chang, 2014; Conant et al., 2014). Our findings suggest that neural foundation needed for flexible and precise vocal control may have a precursor in the brain of a New World primate, the common marmoset.

In contrast to motor cortex, recent human work suggested that Broca's area did not function directly for articulation but rather play a role in information transformation across cortical regions (Flinker et al., 2015). We also found that, of all neurons with vocalization-related activities, a subset (25.7% of 304) had activities only before vocal onset (not during vocal production, see Results), with a similar time scale as the activities in Broca's areas in the human study (peaked within 0.5 s before articulation onset). Whether this subset of neurons function to transform information across cortical regions remains to be determined. The modulation of premotor cortex reported in this study suggests the role of this cortical region in vocal production in marmosets during vocal communication. Future investigations using activation or inactivation methods (electrical, optical, or pharmacological techniques) can help to identify whether there exists a causal relationship between the premotor cortex and vocal production in marmosets. More experiments are also needed to determine whether activities of the premotor neurons encode different types of vocalizations or acoustic features of vocalizations.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grant DC 005808) and the Simons Foundation (Grant SFARI 346068). We thank N. Sotuyo for assistance with animal care and the Multiphoton Imaging Core of Johns Hopkins University Center for Neuroscience Research (under NIH Grant NS050274) for providing the facility to acquire histology images.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Agamaite JA, Chang CJ, Osmanski MS, Wang X. A quantitative acoustic analysis of the vocal repertoire of the common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus) J Acoust Soc Am. 2015;138:2906–2928. doi: 10.1121/1.4934268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behroozmand R, Shebek R, Hansen DR, Oya H, Robin DA, Howard MA, 3rd, Greenlee JD. Sensory-motor networks involved in speech production and motor control: an fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2015;109:418–428. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.01.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard KE, Chang EF. Control of spoken vowel acoustics and the influence of phonetic context in human speech sensorimotor cortex. J Neurosci. 2014;34:12662–12677. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1219-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard KE, Mesgarani N, Johnson K, Chang EF. Functional organization of human sensorimotor cortex for speech articulation. Nature. 2013;495:327–332. doi: 10.1038/nature11911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brasted PJ, Wise SP. Comparison of learning-related neuronal activity in the dorsal premotor cortex and striatum. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:721–740. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-816X.2003.03181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burish MJ, Stepniewska I, Kaas J. Microstimulation and architectonics of frontoparietal cortex in common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus) J Comp Neurol. 2008;507:1151–1168. doi: 10.1002/cne.21596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burman KJ, Palmer SM, Gamberini M, Spitzer MW, Rosa MG. Anatomical and physiological definition of the motor cortex of the marmoset monkey. J Comp Neurol. 2008;506:860–876. doi: 10.1002/cne.21580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burman KJ, Bakola S, Richardson KE, Reser DH, Rosa MG. Patterns of afferent input to the caudal and rostral areas of the dorsal premotor cortex (6DC and 6DR) in the marmoset monkey. J Comp Neurol. 2014a;522:3683–3716. doi: 10.1002/cne.23633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burman KJ, Bakola S, Richardson KE, Reser DH, Rosa MG. Patterns of cortical input to the primary motor area in the marmoset monkey. J Comp Neurol. 2014b;522:811–843. doi: 10.1002/cne.23447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burman KJ, Bakola S, Richardson KE, Yu HH, Reser DH, Rosa MG. Cortical and thalamic projections to cytoarchitectural areas 6Va and 8C of the marmoset monkey: connectionally distinct subdivisions of the lateral premotor cortex. J Comp Neurol. 2015;523:1222–1247. doi: 10.1002/cne.23734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang EF, Niziolek CA, Knight RT, Nagarajan SS, Houde JF. Human cortical sensorimotor network underlying feedback control of vocal pitch. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:2653–2658. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216827110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conant D, Bouchard KE, Chang EF. Speech map in the human ventral sensory-motor cortex. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2014;24:63–67. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2013.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coudé G, Ferrari PF, Rodà F, Maranesi M, Borelli E, Veroni V, Monti F, Rozzi S, Fogassi L. Neurons controlling voluntary vocalization in the macaque ventral premotor cortex. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26822. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMattina C, Wang X. Virtual vocalization stimuli for investigating neural representations of species-specific vocalizations. J Neurophysiol. 2006;95:1244–1262. doi: 10.1152/jn.00818.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doupe AJ, Kuhl PK. Birdsong and human speech: common themes and mechanisms. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1999;22:567–631. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.22.1.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliades SJ, Wang X. Chronic multi-electrode neural recording in free-roaming monkeys. J Neurosci Methods. 2008a;172:201–214. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliades SJ, Wang X. Neural substrates of vocalization feedback monitoring in primate auditory cortex. Nature. 2008b;453:1102–1106. doi: 10.1038/nature06910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epple G. Comparative studies on vocalization in marmoset monkeys (Hapalidae) Folia Primatol (Basel) 1968;8:1–40. doi: 10.1159/000155129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flinker A, Korzeniewska A, Shestyuk AY, Franaszczuk PJ, Dronkers NF, Knight RT, Crone NE. Redefining the role of Broca's area in speech. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:2871–2875. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1414491112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gemba H, Miki N, Sasaki K. Cortical field potentials preceding vocalization and influences of cerebellar hemispherectomy upon them in monkeys. Brain Res. 1995;697:143–151. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00797-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gemba H, Kyuhou S, Matsuzaki R, Amino Y. Cortical field potentials associated with audio-initiated vocalization in monkeys. Neurosci Lett. 1999;272:49–52. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(99)00570-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graziano MS, Reiss LA, Gross CG. A neuronal representation of the location of nearby sounds. Nature. 1999;397:428–430. doi: 10.1038/17115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grohrock P, Häusler U, Jürgens U. Dual-channel telemetry system for recording vocalization-correlated neuronal activity in freely moving squirrel monkeys. J Neurosci Methods. 1997;76:7–13. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0270(97)00068-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hage SR, Nieder A. Single neurons in monkey prefrontal cortex encode volitional initiation of vocalizations. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2409. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashikawa T, Nakatomi R, Iriki A. Current models of the marmoset brain. Neurosci Res. 2015;93:116–127. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickok G. Computational neuroanatomy of speech production. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:135–145. doi: 10.1038/nrg3118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson A, Mavoori J, Fetz EE. Correlations between the same motor cortex cells and arm muscles during a trained task, free behavior, and natural sleep in the macaque monkey. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97:360–374. doi: 10.1152/jn.00710.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jürgens U. On the elicitability of vocalization from the cortical larynx area. Brain Res. 1974;81:564–566. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(74)90853-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jürgens U. Reinforcing concomitants of electrically elicited vocalizations. Exp Brain Res. 1976;26:203–214. doi: 10.1007/BF00238284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jürgens U. Neural pathways underlying vocal control. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2002;26:235–258. doi: 10.1016/S0149-7634(01)00068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jürgens U, Ploog D. Cerebral representation of vocalization in the squirrel monkey. Exp Brain Res. 1970;10:532–554. doi: 10.1007/BF00234269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jürgens U, Zwirner P. Individual hemispheric asymmetry in vocal fold control of the squirrel monkey. Behav Brain Res. 2000;109:213–217. doi: 10.1016/S0166-4328(99)00176-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalaska JF, Scott SH, Cisek P, Sergio LE. Cortical control of reaching movements. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1997;7:849–859. doi: 10.1016/S0959-4388(97)80146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalaska JF, Sergio LE, Cisek P. Cortical control of whole-arm motor tasks. Novartis Found Symp. 1998;218:176–190. doi: 10.1002/9780470515563.ch10. discussion 190–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korzeniewska A, Franaszczuk PJ, Crainiceanu CM, Kuś R, Crone NE. Dynamics of large-scale cortical interactions at high gamma frequencies during word production: event related causality (ERC) analysis of human electrocorticography (ECoG) Neuroimage. 2011;56:2218–2237. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurata K, Tanji J. Premotor cortex neurons in macaques: activity before distal and proximal forelimb movements. J Neurosci. 1986;6:403–411. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-02-00403.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T, Liang L, Wang X. Neural representations of temporally asymmetric stimuli in the auditory cortex of awake primates. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:2364–2380. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.6.2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margoliash D, Konishi M. Auditory representation of autogenous song in the song system of white-crowned sparrows. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:5997–6000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.17.5997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CT, Wang X. Sensory-motor interactions modulate a primate vocal behavior: antiphonal calling in common marmosets. J Comp Physiol A Neuroethol Sens Neural Behav Physiol. 2006;192:27–38. doi: 10.1007/s00359-005-0043-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CT, Wren Thomas A. Individual recognition during bouts of antiphonal calling in common marmosets. J Comp Physiol A Neuroethol Sens Neural Behav Physiol. 2012;198:337–346. doi: 10.1007/s00359-012-0712-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CT, Beck K, Meade B, Wang X. Antiphonal call timing in marmosets is behaviorally significant: interactive playback experiments. J Comp Physiol A Neuroethol Sens Neural Behav Physiol. 2009;195:783–789. doi: 10.1007/s00359-009-0456-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CT, Dimauro A, Pistorio A, Hendry S, Wang X. Vocalization induced CFos expression in marmoset cortex. Front Integr Neurosci. 2010a;4:128. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2010.00128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CT, Mandel K, Wang X. The communicative content of the common marmoset phee call during antiphonal calling. Am J Primatol. 2010b;72:974–980. doi: 10.1002/ajp.20854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CT, Thomas AW, Nummela SU, de la Mothe LA. Responses of primate frontal cortex neurons during natural vocal communication. J Neurophysiol. 2015;114:1158–1171. doi: 10.1152/jn.01003.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nottebohm F, Arnold AP. Sexual dimorphism in vocal control areas of the songbird brain. Science. 1976;194:211–213. doi: 10.1126/science.959852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C, Petrides M, Rosa M, Hironobu T. The marmoset brain in stereotaxic coordinates. San Diego: Academic; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Penfield W, Roberts L. Speech and brain mechanisms. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Petrides M, Cadoret G, Mackey S. Orofacial somatomotor responses in the macaque monkey homologue of Broca's area. Nature. 2005;435:1235–1238. doi: 10.1038/nature03628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pistorio AL, Vintch B, Wang X. Acoustic analysis of vocal development in a New World primate, the common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus) J Acoust Soc Am. 2006;120:1655–1670. doi: 10.1121/1.2225899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remington ED, Osmanski MS, Wang X. An operant conditioning method for studying auditory behaviors in marmoset monkeys. PLoS One. 2012;7:e47895. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy S, Wang X. Wireless multi-channel single unit recording in freely moving and vocalizing primates. J Neurosci Methods. 2012;203:28–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy S, Miller CT, Gottsch D, Wang X. Vocal control by the common marmoset in the presence of interfering noise. J Exp Biol. 2011;214:3619–3629. doi: 10.1242/jeb.056101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz AB, Moran DW, Reina GA. Differential representation of perception and action in the frontal cortex. Science. 2004;303:380–383. doi: 10.1126/science.1087788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simões CS, Vianney PVR, de Moura MM, Freire M a M, Mello LE, Sameshima K, Araújo JF, Nicolelis M a L, Mello CV, Ribeiro S. Activation of frontal neocortical areas by vocal production in marmosets. Front Integr Neurosci. 2010;4:123. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2010.00123. pii. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton D, Larson C, Lindeman RC. Neocortical and limbic lesion effects on primate phonation. Brain Res. 1974;71:61–75. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(74)90191-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade J, Arnold AP. Sexual differentiation of the zebra finch song system. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1016:540–559. doi: 10.1196/annals.1298.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West RA, Larson CR. Neurons of the anterior mesial cortex related to faciovocal activity in the awake monkey. J Neurophysiol. 1995;74:1856–1869. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.5.1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]