Abstract

The Hsp70 class of heat shock proteins (Hsps) has been implicated at multiple points in the immune response, including initiation of proinflammatory cytokine production, antigen recognition and processing, and phenotypic maturation of antigen-presenting cells (APCs). This class of chaperones is highly conserved in both sequence and structure, from prokaryotes to higher eukaryotes. In all cases, these chaperones function to bind short segments of either peptides or proteins through an adenosine triphosphate–dependent process. In addition to a possible role in antigen presentation, these chaperones have also been proposed to function as a potent adjuvant. We compared 4 evolutionary diverse Hsp70s, E. coli DnaK, wheat cytosolic Hsc70, plant chloroplastic CCS1, and human Hsp70, for their ability to prime and augment a primary immune response against herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV1). We discovered that all 4 Hsp70s were highly effective as adjuvants displaying similar ability to lipopolysaccharides in upregulating cytokine gene expression. In addition, they were all capable of inducing phenotypic maturation of APCs, as measured by the display of various costimulatory molecules. However, only the human Hsp70 was able to mediate sufficient cross-priming activity to afford a protective immune response to HSV1, as judged by protection from a lethal viral challenge, in vitro proliferation, cytotoxicity, and intracellular interferon-γ production. The difference in immune response generated by the various Hsp70s could possibly be due to their differential ability to interact productively with other coreceptors and different regulatory cochaperones.

INTRODUCTION

Recently, the mammalian heat shock proteins (Hsps), Hsp70 and Hsp90, have been shown to have great potential in generating potent immune responses in vaccine development against tumor- or viral-derived antigens (Udono et al 1993; Suzue et al 1996; Blachere et al 1997; Ciupitu et al 1998). This finding derives largely from the observation that these cellular chaperones are capable of eliciting a cross-priming event. Through cross-priming, Hsps have been implicated in the delivery-presentation of exogenous, class I–restricted antigens by antigen-presenting cells (APC), in turn priming CD8+ cytolytic T cells that can kill transformed tumor cells or the virus-infected cells (Srivastava et al 1994; Arnold et al 1995; Suto et al 1995; Ciupitu et al 1998). Classically, most antigen presentation models fail to invoke the endogenous pathway of antigen delivery, which is also accessible to antigens derived from an exogenous source. Antigen delivery through an Hsp-facilitated cross-priming process has forced us to reexamine these traditional views on antigen presentation. Moreover, several Hsps alone have been shown to possess a strong adjuvant property, ensuring that the antigen bound to the Hsp is recognized by CD8+ T cells, yielding an inflammatory type 1 response and thereby avoiding tolerance (Suzue et al 1996; Melcher et al 1998; Rico et al 1998; Chen et al 1999; Todryk et al 1999; Lehner et al 2000). This inflammatory response results in both the production of proinflammatory cytokines from interacting APCs and the maturation and upregulation of various costimulatory molecules, including B7.1, B7.2, and CD40, on the APC (Basu et al 2000; Singh-Jasuja et al 2000; Somersan et al 2001).

How Hsps influence and possibly modulate these 2 important, yet distinct, immune-inducing processes must be elucidated further. In addition, several prokaryotic Hsps have been implicated with cross-reactivity with autoantigens in rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease systems, which indicates that even the immune system is likely unable to discern differences in these proteins (Beech et al 1997; Steinhoff et al 1999). Evolutionarily, these processes may be linked to the extreme amino acid conservation found in Hsps from primitive prokaryotes to higher eukaryotes, such as plants and humans (Lindquist et al 1986). An assessment of conservation interpreted in evolutionary terms with respect to functional implications has been reviewed in detail by Karlin et al (1998). As a result of this extreme conservation, it may be possible to exploit the readily available Hsps from bacteria and plants to mimic some of the emerging immunological functions normally performed by mammalian Hsps.

Many of the in vivo functions carried out by the HSP70 family of chaperones are mediated by nucleotide-binding status of the N-terminal adenosine triphosphatase (ATPase) domain. A second and distinct C-terminal domain includes a peptide-binding domain, with broad peptide-binding capabilities permitting interaction with a massive array of peptides and proteins, including those of viral and tumor origin (Jindal et al 1992). Although not fully understood, these 2 domains reciprocally influence one another such that peptide binding stimulates adenosine triphosphate (ATP) hydrolysis and adenosine diphosphate (ADP) binding increases the peptide affinity. Analysis of 53 random proteins indicates that on average a protein will contain an Hsp70-binding domain for every 30 residues (Rudiger et al 1997). However, it is unclear if there is any mechanism for discrimination between self-derived and non–self-derived antigens. Perhaps, it is this lack of self-derived or non–self-derived antigen discrimination that belies how Hsp70s are able to facilitate the cross-priming of antigenic peptides.

Many recent reports (Suzue et al 1996; Robert et al 2001) have clearly demonstrated that chaperones, from a variety of sources, are able to cross-present foreign antigens to APCs, which in turn prime cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) to seek and destroy cells expressing the antigen. As has been well established, the APCs that prime these CTLs must also provide them with a secondary signal if the CTLs are to become fully functional. However, it is also possible that the stress proteins could simply provide the antigen without activating or stimulating the interacting APC, thereby resulting in tolerance of the CTLs for the antigen instead of yielding an effective cross-priming response. Therefore, in vivo, the chaperones may provide an additional immunological activity besides facilitating the delivery or cross-priming of the antigens to APCs.

Indeed, Hsp70s have been shown to convey 2 types of immunological information. The first is a general, innate signal, which is caused by Hsps binding to a receptor on the surface of the cell and leads to the induction of proinflammatory cytokines (Asea et al 2000). The second signal is derived from the protein or peptide that is bound to the peptide-binding domain, which somehow gains access to the endogenous pathway of antigen presentation (Srivastava et al 1994).

Consistent with the above discussion, mammalian Hsp70s, when used as adjuvants, have been shown to offer protection to mice challenged by many viruses (Ciupitu et al 1998; Kumaraguru et al 2002). In an extension of this work, we choose to evaluate whether Hsp70s, as a protein family, were able to display a conservation of immunological function. Therefore, we evaluated Hsp70 homologs from 4 evolutionarily diverse sources, including the bacteria Hsp70 (DnaK), a higher plant organellar Hsp70 (CSS1), the plant cytosolic Hsc70, and a recombinant human Hsp70 (rhHsp70), for their ability to function as adjuvants or to generate protective immunity against a lethal challenge with herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV1). This evaluation involved analyzing all immunological properties of the previously mentioned Hsp70s. The 4 Hsp70s were highly effective as adjuvants capable of inducing phenotypic maturation and cytokine secretion but differed in their cross-priming activity. We argue that their differential ability to interact productively with different regulatory cochaperones or coreceptors may be the possible reason.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Female 4-week-old to 5-week-old C57BL/6 (H-2b) mice were purchased from Harlan Sprague-Dawley (Indianapolis, IN, USA). On conducting the research described in this work, the investigators adhered to the guide for the care and use of laboratory animals, as proposed by the committee on Care of Laboratory Animal Resources Commission on Life Sciences, National Research Council. The facilities are fully accredited by the American Association of Laboratory Animal Care.

Antigens

Peptides

High-performance liquid chromatography–purified HSVgB (aa 498–505) peptide SSIEFARL and chicken ovalbumin (aa 257–264) peptide SIINFEKL were obtained from Research Genetics (Huntsville, AL, USA).

Virus

HSV1 kos strain and HSV1-17 were grown on Vero cell monolayers (American Type Culture Collection [Rockville, MD, USA] catalog no. CCL81), titrated, and stored in aliquots at −80°C until use.

Heat shock proteins

The recombinant human Hsp was purchased from Stressgen, Victoria, BC, Canada. CSS1 was purified from 14-day-old pea (Pisum sativum) cotyledons by an affinity chromatography method similar to that used to purify Bovine taurus Hsc70 (Schlossman 1984). Fractionated stroma from pea was prepared as described previously (Markwell 1992) and diluted 1:10 with buffer M (20 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid, pH 7.5, 20 mM NaCl, Mg(Oac)2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 0.1% [v/v] Triton X-100). Next, the entire sample was loaded onto an ATP-agarose column (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) pre-equilibrated with buffer M at 4°C. The column was washed exhaustively with buffer M, then buffer M containing 1 M NaCl, and finally buffer M again. CSS1 was then eluted with 10 mM ATP in buffer M titrated to pH 7.5. Authenticity of CSS1 was demonstrated by cross-reactivity on a Western blot with a polyclonal DnaK antibody serum (Ivey et al 2000a). Eluted fractions containing CSS1 were dialyzed exhaustively and concentrated in buffer M by ultrafiltration against a 30-kDa–molecular mass cutoff membrane, aliquoted, and stored at −85°C. The preparations were analyzed for their ATPase activity before use (Ivey et al 2000b).

Lipopolysaccharide contamination and removal

All the Hsp preparations were passed through an Endo-free column (purchased from Pierce, Rockford, IL) to minimize the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) contamination. The endotoxin level was then tested using Limulus amebocyte lysate assay (LAL kit). The media used in all these assays contained polymixin B sulfate. The highest amount of endotoxin (1 endotoxin unit [EU]) was found in the DnaK preparation, and the rest of the preparations had <0.5 EU. Hence, 1 EU of LPS was used in all the assays measuring the upregulation of activation markers and included in the figures. In addition, the preparations were either heat inactivated or protease treated and then tested for their ability to upregulate the activation marker. The results from these studies were less or comparable with the pattern observed with 1 EU of LPS; hence, the data have not been shown.

Cell lines

MC38 (colon adenocarcinoma), EL4 (C57BL/6, H-2kb lymphoma), EMT6 (BALB/c mammary adenocarcinoma cells, H-2d), and Vero (monkey kidney cells) were used. All cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin G, 100 μg/mL streptomycin sulfate, and 2 mM l-glutamine.

Antibodies

Fluorescent tagged antibodies for fluorescent activated cell sorter (FACS) staining (all purchased from Becton & Dickinson Co, San Diego, CA, USA) included the following: fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)– and phycoerythrin (PE)–labeled IgG1 isotype controls (catalog nos. 20604A, 20605A), FITC anti-INFγ (catalog no. 18114A), CD3e (catalog no. 01084A), CD4 (catalog no. 09425A), CD8a (catalog no. 01045A), CD11c (catalog no. 09705A), CD16/CD32 (catalog no. 01241A), CD154 (catalog no. 09025B/09022D), CD80 (catalog no. 01225A/01224D), and CD86 (catalog no. 01265B).

Hsp70 and peptide binding

Four previously described Hsps and the peptide SSIEFARL (HSVgB498–505) were used. The peptides were loaded onto Hsp70 by the procedure described by Ciupitu et al (1998). In brief, the peptides were incubated with the Hsps or bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) in binding buffer (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS] with 2 mM MgCl2) at 37°C for 60 minutes. Then, 0.5 mM ADP (Sigma) was added, and incubation was continued for an additional 60 minutes.

Immunizations

C57BL/6 mice were immunized with peptide alone (2.5 μg DnaK, 2.5 μg CSS1, 2.5 μg HSC70, and 2.5 μg human Hsp70), hsps loaded with peptide (2 μg of hsps + 2 μg of SSIEFARL), BSA loaded with peptide or buffer alone. The immunizations were done intraperitoneally on day 0 and day 21. The intraperitoneal route was chosen after experimenting with intramuscular and footpad injections.

Immunological assays

HSV-specific lymphoproliferation

Splenocytes from experimental mice were restimulated in vitro with X-ray–irradiated APCs that were infected with ultraviolet (UV)–inactivated HSV (1.5 m.o.i. before irradiation) or uninfected-unpulsed APCs and incubated for 5 days at 37°C. In some samples, Con A was used as a polyclonal-positive control and incubated for 3 days. Eighteen hours before harvesting, [3H]-thymidine was added to cultures. Proliferative responses were tested in quadruplicate wells, and the results were expressed as mean counts per minute (cpm) ± standard deviation.

Peptide-specific proliferation

The procedure is exactly as described above, except for the stimulators. The APCs for this experiment were from B6 mice, and these were pulsed with HSVgB498–505 for CD8+-specific stimulation. Fifty units per milliliter of interleukin-2 (IL-2) was added to the cultures stimulated for CD8+ T-cell proliferation. The incubation was carried out for 5 days, with the last 18 hours in the presence of [3H]-thymidine.

CTL assays

The CTL assay was performed as described earlier (Kumaraguru et al 2000). In brief, effector cells generated after in vitro expansion (with peptide or HSV) were analyzed for their ability to kill major histocompatibility complex–matched antigen-presenting targets. They were mixed with the targets at varying ratios and incubated for 4 hours. The targets included syngeneic cells plus antigen, syngeneic cells with irrelevant antigen, and allogeneic cells with antigen. The chromium release results were computed as described elsewhere (Kumaraguru et al 2000).

Cytokine enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

The culture supernatants from splenic adherent cells pulsed with indicated amounts of various Hsps, without the addition of any exogenous cytokine, were screened for the presence of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα), IL-12, and IL-6. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) plates were coated with capture antibodies for the individual cytokines mentioned previously and incubated at 4°C overnight. The plates were washed with PBS–Tween 20 and blocked with 3% BSA for 2 hours at room temperature. After washing, samples and serially diluted standards were added to the plate, incubated for 2–4 hours, and then washed before the addition of cytokine-specific detection antibodies for 2 hours. The plates were washed, and peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA, USA, catalog no. 016-030-084) was added. The color was developed by adding the substrate solution (11 mg of 2,2′-azino-bis-3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid in 25 mL of 0.1 M citric acid, 25 mL of 0.1 M sodium phosphate, and 10 μL of hydrogen peroxide). The concentrations were calculated with an automated ELISA reader (SpectraMAX 340, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

Cell labeling

FACS analysis

Cell suspensions containing 1 × 106 cells were incubated with 1 μg each of FITC- or PE-labeled antibodies. The cells were then incubated on ice for 45 minutes to 1 hour. Cells were washed again with FACS buffer (1× PBS containing 3% fetal calf serum and 0.1% sodium azide) and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Cells were analyzed on Becton Dickinson FACScan using CellQuest software.

Intracellular cytokine staining

To enumerate interferon-γ (IFNγ)–producing cells, intracellular cytokine staining was performed as described previously (Kumaraguru and Rouse 2000). In brief, 106 freshly expanded splenocytes were cultured in flat-bottomed 96-well plates. Cells were left untreated, stimulated with HSV peptide SSIEFARL (0.1 μg/mL), or treated with PMA (10 ng/mL) and ionomycin (500 ng/mL) and then incubated for 6 hours at 37°C in 5% CO2. Brefeldin A was added during the culture period to facilitate intracellular cytokine accumulation. After this period, cell surface staining was performed, followed by intracellular cytokine staining using the Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (PharMingen, San Diego, CA, USA), in accordance with the manufacturer's recommendations. All antibodies were purchased from PharMingen, and processed cells were analyzed with FACScan and the CellQuest software.

RESULTS

Variation in protection afforded by immunization with various Hsps

Hsp70s obtained from various species, as listed earlier, were loaded with the SSIEFARL peptide and used as immunogens in C57BL/6 mice to compare their chaperone and adjuvant functions. Groups of mice (10 mice/group) were immunized with a pretitrated dose of rhHsp70, DnaK, CSS1, and plant Hsc70 either alone or loaded with SSIEFARL and later analyzed for HSV-specific responses. SSIEFARL chemically coupled to BSA was used as a control.

The mice belonging to each group that was immunized on day 0 and day 21 were first assessed for their ability to resist challenge on day 28 by intracutaneous lethal infection with HSV1-17 strain. As is evident from Figure 1, the preparations varied in affording protection. All mice that received rhHsp70-peptide and uvHSV survived the challenge, whereas only 60% of the DnaK-peptide–, 30% of the CSS1-peptide–, and none of the Hsc70-peptide–immunized groups survived. The average score on day 10 was 2.5 in rhHsp70-peptide–, 3.7 in DnaK-peptide–, 4.4 in CSS1-peptide–, and 5 in Hsc70-peptide–immunized groups. Even though Hsp70 is considered highly conserved through evolution, such difference in affording protection was not anticipated. Hence, we proceeded to analyze the adjuvanticity and chaperone properties of these Hsp preparations in in vitro and in vivo assays.

Fig 1.

Zoster challenge of mice immunized with SSIEFARL-loaded chaperones. Five-week-old to 6-week-old C57BL/6 mice were scarified on their left flank after depilating with a hair clipper and a chemical depilator (Nair-Carter, Wallace, NY, USA). The mice were anesthetized using metofane (Pitman-Moore, Mundelein, IL, USA), and a total of 20 scarifications were made in an approximately 4-mm2 area. To such scarifications, 10 μL of PBS containing 106 plaque-forming units of herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV1) strain 17 was added and gently massaged. Animals were inspected daily for the development of zosteriform ipsilateral lesions, general behavioral changes, encephalitis, and mortality. The severity of the lesions was scored as follows: 1+ = vesicle formation; 2+ = local erosion and ulceration of the local lesion; 3+ = mild to moderate ulceration; 4+ = severe ulceration, hind limb paralysis, and encephalitis; 5 = moribund animals that were euthanized. Numbers in parentheses denote average scores. The figure shows individual scores for 10 mice in each group.

In vitro demonstration of the difference in adjuvant property

The Hsps were analyzed for their adjuvant properties by pulsing naive adherent splenocytes. The cells were pulsed with 10 nM concentrations of various preparations (10 nM was chosen as the dose after preliminary dose-response studies with rhHsp70) for 6 hours and stained for surface markers indicative of maturation status (CD80, CD86, and CD40). Although all the Hsps were able to upregulate the surface expression (Fig 2a), they differed in the intensity of staining, probably reflecting their dissimilarity in inducing maturation. A mixture of all the Hsps that were heat inactivated and added to the cell culture failed to upregulate the surface markers, thereby ruling out the role of contaminating LPS in the preparations contributing to upregulation.

Fig 2.

(a) Staining for activation marker. Splenocytes (106) were stained with labeled anti-CD80, anti-CD86, and anti-CD40 after stimulation in vitro with various heat shock proteins (Hsps). Unstimulated splenocytes were stained with the same antibodies to serve as background for histogram overlay. The cells were washed and analyzed using FACScan and CellQuest software. The highest amount of endotoxin found in the Hsp preparations (1 EU) was used as a control to show the contribution of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) contamination to upregulation of activation markers. Controls included were Hsps that were individually either heat inactivated or protease treated (data not shown). The figure represents 1 of 5 experiments with similar patterns of results. (b) Cytokine analysis by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The supernatants collected from adherent splenocyte cultures stimulated with various Hsps were collected and analyzed by ELISA. The concentrations of each cytokine were deduced from the standard curve obtained using recombinant cytokine. One EU of LPS, the contaminating amount found in one of the preparations, was used as control for background. Supernatants collected from unstimulated, heat-inactivated, and protease-treated cultures served as controls (data not shown). The figure represents 1 of 5 experiments with similar patterns of results

Alternatively, the adherent splenocytes were also stimulated with 10 nM concentrations of various Hsps for 36 hours. The supernatant collected from these cultures was analyzed for the presence of proinflammatory cytokines IL-6, TNFα, and IL-12. Figure 2b shows the amount of cytokine obtained as a consequence of stimulation with various preparations. rhHsp70 induced cytokines to the level seen with LPS stimulation in the case of all 3 cytokines analyzed. DnaK produced three-fourths the levels observed with LPS. CSS1 was comparable with DnaK in inducing TNFα and IL-12 but was way behind in its ability to induce IL-6.

Hsc70 had very minimal activity. As observed with activation markers, heat-inactivated preparations did not induce any proinflammatory cytokine, ruling out LPS contamination. The results from these studies indicate that there is some minimal difference in the adjuvanticity; hence, it may not be the contributing factor for the poor immunogenicity.

In vivo analyses

These results prompted us to investigate the possible peptide-chaperoning ability of the various Hsps we used. After similar immunization regimens, groups of mice were analyzed by 3 well-characterized assays that included proliferative and IFNγ responses to peptide stimulation and CTL assay. Accordingly, responders were stimulated with syngeneic peptide–pulsed or HSV-infected, X-ray–irradiated APCs to assess their in vitro proliferative ability. There was a distinct difference in the proliferation, as measured by the cpm in different groups. The splenocytes from the rhHsp70-immunized group showed (Fig 3) a robust proliferative ability (cpm = 2448 ± 340) in response to peptide-pulsed stimulators, whereas the DnaK-peptide–immunized group was only 50% of the rhHsp70-peptide–immunized group. The CSS1-peptide– and Hsc70-peptide–immunized mice were 38% and 27% of the rhHsp70-peptide–immunized group, respectively. A similar pattern of result was also observed with HSV-infected stimulators. Results accrued from these studies reflect the obvious difference in inducing peptide-specific responses.

Fig 3.

Hsp70 obtained from various species loaded in vitro with SSIEFARL also induces HSVgB498–505 SSIEFARL-specific CD8+ T cell proliferative response in mice. Five-week-old to 6-week-old C57BL/6 mice were immunized with SSIEFARL-loaded recombinant human Hsp70, DnaK, Hsc70, and CSS1, and SSIEFARL-conjugated bovine serum albumin and HSV1 kos (1 × 106 plaque-forming units) on day 0 and day 21. One week later, the splenocytes were harvested and nylon wool nonadherent T cells were assessed for in vitro proliferative response to SSIEFARL peptide–pulsed antigen-presenting cells (APCs). The responders (2 × 106) were serially double diluted, and the stimulators (1 × 105) were mixed at a ratio starting from 20:1 (responder-stimulator), with the addition of 50 U/mL of recombinant interleukin-2, and incubated for 5 days, with the last 18 hours in the presence of [3H]-thymidine. The cells were harvested and read with an Inotech automatic cell harvester and reader and the results expressed as counts per minute. The controls included and not shown are anti-CD3–stimulated responders, stimulators only, and responders with irrelevant peptide-pulsed APCs. The figure represents the average of 5 mice

Next, we analyzed the function and frequency of the peptide-specific CD8+ T cell by the peptide-stimulated intracellular IFNγ assay. Splenocytes obtained from various groups were stimulated for 6 hours with the peptide in the presence of brefeldin A and later stained for IFNγ intracellularly. The frequency of the CD8+ T cell (Fig 4) was about the same in HSV-peptide– and rhHsp70-peptide–immunized mice (8.2% and 8.3%, respectively). The frequency was much lesser in DnaK-peptide, CSS1-peptide, and Hsc70-peptide groups. There was absolutely no staining for IFNγ in the control groups (Fig 4).

Fig 4.

Immunization of B6 mice with Hsp70-SSIEFARL induces interferon-γ (IFNγ)–positive SSIEFARL-specific CD8+ T cells. Intracellular staining for IFNγ: 1 × 106 splenocytes obtained from immunized C57BL/6 mice were stimulated in vitro with the SSIEFARL peptide (1 μg/mL), with the addition of 50 U of recombinant interleukin-2 and 1 μg/mL of Brefeldin A for 6 hours. The cells were later washed and stained for CD8 with phycoerythrin-labeled anti-CD8 and then washed again, fixed, permeabilized, and stained intracellularly for IFNγ with fluorescein isothiocyanate–labeled anti-IFNγ. The controls included isotype antibody control. The stained cells were analyzed with a FACScan machine. The CD8+ IFNγ+ T cells are seen in the upper right quadrant. The experiment was repeated 3 times, which gave similar results. The figure represents one such experiment

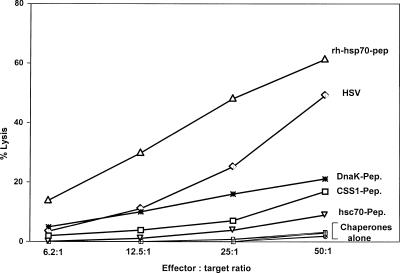

Although intracellular staining for IFNγ is a reliable assay, it is possible that not all intracellular IFNγ-positive cells can kill. To assess this possibility, splenocytes were in vitro expanded for 5 days, and 51Cr release assay was performed for assessing the cytotoxic ability. The effectors thus generated were tested for their ability to lyse chromium-loaded SSIEFARL-presenting syngeneic cells. The results, as shown in Figure 5, depict the percentage of lysis obtained with MC38-SSIEFARL targets at a 50:1 effector-target ratio. The rhHsp70-peptide immunization was very effective (62%) and excelled that of virus control (54%). Although the percentages of killing in DnaK-peptide–, CSS1-peptide–, and Hsc70-peptide–immunized mice were 21%, 16%, and 8%, respectively, the control that included only chaperones and BSA-SSIEFARL did not induce any cyotoxicity at all.

Fig 5.

In vivo immunization with Hsp70-peptide induces potent primary cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) responses. B6 mice were immunized with SSIEFARL-loaded recombinant human Hsp70, DnaK, Hsc70, and CSS1; SSIEFARL-conjugated bovine serum albumin and HSV1 kos (1 × 106 plaque-forming units); or buffer only intraperitoneally on day 0, boosted on day 21, and terminated on day 28 or day 60 after the second immunization for spleen cell collection. A portion of the single-cell suspension of the spleen was in vitro expanded for 5 days at 37°C and 5% CO2, with X-ray–irradiated (3000 rads), herpes simplex virus (HSV)–infected (1.5 moi), or SSIEFARL peptide–pulsed (5 μg/mL) B6 antigen-presenting cells. At the end of the incubation period, they were used as effectors in a chromium release CTL assay. 51Cr-pulsed, major histocompatibility complex (MHC)–matched, HSV-infected (MC38-HSV); MHC-matched, SSIEFARL-pulsed (MC38-SSIEFARL); MHC-mismatched, HSV-infected, and SSIEFARL-pulsed (EMT-6-HSV, EMT6-SSIEFARL); and MHC-matched, uninfected (MC38) targets were used. The figure shows the percentage of lysis for MC38-SSIEFARL targets only and the results of 3 different experiments

DISCUSSION

Both innate and adaptive immune responses are involved in the protective response after exposure to pathogens. One part of the innate response is the detection and response to one or more adjuvants that promote the release of immunostimulatory molecules. This adjuvant activity must also be considered in the design of an effective vaccine because a crucial part of vaccine construction must include a strong yet well-tolerated adjuvant. Currently, there are no broadly approved adjuvants for human therapeutic use. The results in this article suggest that Hsp70 may be a viable candidate for a well-tolerated adjuvant. Several studies have previously demonstrated that Hsp70 or gp96 preparations isolated from tumors have been shown to induce a specific CTL response and afford protection to the same tumors (Udono et al 1993; Castelli et al 2001; Ciupitu et al 2002). Stress proteins isolated from virus-infected cells can induce a virus-specific immune response when used as an immunogen (Srivastava et al 1994). It has also been shown that recombinant stress proteins loaded with peptide epitopes of viruses can also achieve immunogenicity. Our studies with Hsp70s loaded in vitro with the HSVgB peptide (Kumaraguru et al 2002) and that of Ciupitu et al using Hsp70s loaded with LCMV peptides (Ciupitu et al 1998) demonstrated the ability of the proteins to induce a virus-specific CTL response and to protect mice from lethal challenge with the respective virus.

Hsps are ubiquitous and highly conserved molecular chaperones. Evolutionarily, they represent an example of molecular “descent with modification” at the levels of gene sequence, genomic organization, regulation of gene expression, protein structure, and function (Feder et al 1999). In a comparative study using amphibian and mammalian systems, Robert et al (2001) made a striking observation that the amphibian Hsps can be recognized by a mouse APC, and the peptide chaperoned by it can be processed and presented. Given this, one may expect little or no difference among the Hsps obtained from diverse species in their ability to chaperone a peptide epitope and induce specific responses. In this report, we compared the efficacy of HSV-specific immune induction by 4 different Hsp70s (coupled with the SSIEFARL epitope) obtained from evolutionarily diverse sources (plant [Hsc70 and CSS1], E. coli [DnaK], and human recombinant Hsp70 [rhHsp70]).

One significant observation in our report is the production of proinflammatory cytokines by adherent spleen cells in response to the addition of the 4 Hsps studied. There was no significant difference between the individual chaperones. In addition, their ability to upregulate costimulatory molecules was also comparable. However, there was a slight increase in CD86 expression in rhHsp70-treated cells, partly explaining the better response achieved with it. This suggests that all these Hsps signal through a common receptor or pathway. The recently identified receptor, CD91, could be involved in this process, as reported by Srivastava and colleagues (Basu et al 2001).

In spite of the above findings, it was clear that the ability of the various Hsps to induce a protective response against HSV varied. The rhHsp70-peptide–immunized group was the only one that showed a survival rate comparable with uvHSV-infected control mice in a lethal challenge experiment. The remaining mice immunized with the other more evolutionarily distant chaperones belonging to other groups (Hsc70-CSS1-DnaK) coupled to SSIEFARL did not resist the viral challenge.

A similar finding could also be observed in the 3 in vitro assays performed to assess T-cell function in these mice. In all 3 assays (peptide-specific proliferation assay, peptide-induced intracellular IFNγ assay, and 51Cr release assay), each chaperone was near the control level, except for the rhHsp70-SSIEFARL group. Again, the differences in these assays could be explained by the variation in the receptor requirement of the Hsps studied. It is not surprising that the most favorable interactions were between the components from the most phylogenetically related organisms, ie, a murine cell and a human Hsp70.

Although mammalian Hsp70s have been shown to bind CD91 (Basu et al 2001), there may still be the involvement of other receptors or coreceptors. Thus, as suggested by Asea et al (2000), hHsp70 uses CD14 as a coreceptor to trigger cells. Hence, depending on both the cell type and the origin of Hsp70, different receptors may be involved in recognition. In addition, a recent finding (Wang et al 2001) suggests CD40 as a cellular receptor mediating Mycobacterium Hsp70-stimulated chemokine production. In the light of these reports, we suggest that the difference we observed among the Hsp70s tested may be due to the differential ability of a mouse APC to respond to the various Hsps. However, our results also suggest that the adjuvant properties of the Hsp are conserved, explaining the observed similarity in their ability to induce cytokine and chemokine production and upregulation of costimulatory molecules. Thus, these divergent activities in inducing peptide-specific responses could argue for 2 separate Hsp70 receptors, one broad-range receptor that results in signaling (activation and stimulation), thereby resulting in proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine production, and a second, more specific receptor, which is involved in the internalization of the Hsp70-peptide complex. The second receptor is specific for the human Hsp70 and can lead to the protective response that we observed in the viral challenge experiment. Compounding these interpretations is the possibility that the differences observed between the Hsps may also be attributed to the restricted involvement of cochaperones that affect their function. One such cochaperone is the Hsp40/DnaJ (Suh et al 1999). The availability of these cochaperones in mouse may limit the function of these Hsps from sources other than the mouse. A final possibility is that there could be other cell types (besides APCs) capable of interacting with and responding to Hsp70 in varying degrees depending on both the species of animal and the type of Hsp70, such as NK cells (Multhoff et al 1999) or even T cells (Lehner et al 2000).

The conclusion drawn from this study is that not all Hsps signal through the same pathway or receptor and that the receptor triggering the pathway resulting in activation and cytokine production may not be the receptor that is involved in internalization of the chaperone-peptide complex. Depending on one or more biochemical or structural differences of the chaperones tested, the extent of interaction with the receptor or coreceptor may vary, resulting in differential responses.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a National Institutes of Health Grant AI 46462 to B.T.R. and in part by a grant to B.D.B. (MCB-9604535) from the Cell Biology Program at the National Science Foundation.

REFERENCES

- Arnold D, Faath S, Rammensee H, Schild H. Cross-priming of minor histocompatibility antigen-specific cytotoxic T cells upon immunization with the heat shock protein gp96. J Exp Med. 1995;182:885–889. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.3.885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asea A, Kraeft SK, Kurt-Jones EA, Stevenson MA, Chen LB, Finberg RW, Koo GC, Calderwood SK. HSP70 stimulates cytokine production through a CD14-dependant pathway, demonstrating its dual role as a chaperone and cytokine. Nat Med. 2000;6:435–442. doi: 10.1038/74697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu S, Binder RJ, Ramalingam T, Srivastava PK. CD91 is a common receptor for heat shock proteins gp96, hsp90, hsp70, and calreticulin. Immunity. 2001;14:303–313. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00111-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu S, Binder RJ, Suto R, Anderson KM, Srivastava PK. Necrotic but not apoptotic cell death releases heat shock proteins, which deliver a partial maturation signal to dendritic cells and activate the NF-kappa B pathway. Int Immunol. 2000;12:1539–1546. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.11.1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beech JT, Siew LK, Ghoraishian M, Stasiuk LM, Elson CJ, Thompson SJ. CD4+ Th2 cells specific for mycobacterial 65-kilodalton heat shock protein protect against pristane-induced arthritis. J Immunol. 1997;159:3692–3697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blachere NE, Li Z, Chandawarkar RY, Suto R, Jaikaria NS, Basu S, Udono H, Srivastava PK. Heat shock protein-peptide complexes, reconstituted in vitro, elicit peptide-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte response and tumor immunity. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1315–1322. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.8.1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castelli C, Ciupitu AM, Rini F, Rivoltini L, Mazzocchi A, Kiessling R, Parmiani G. Human heat shock protein 70 peptide complexes specifically activate antimelanoma T cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:222–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Syldath U, Bellmann K, Burkart V, Kolb H. Human 60-kDa heat-shock protein: a danger signal to the innate immune system. J Immunol. 1999;162:3212–3219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciupitu AM, Petersson M, Kono K, Charo J, Kiessling R. Immunization with heat shock protein 70 from methylcholanthrene-induced sarcomas induces tumor protection correlating with in vitro T cell responses. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2002;51:163–170. doi: 10.1007/s00262-002-0263-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciupitu AM, Petersson M, O'Donnell CL, Williams K, Jindal S, Kiessling R, Welsh RM. Immunization with a lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus peptide mixed with heat shock protein 70 results in protective antiviral immunity and specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1998;187:685–691. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.5.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feder ME, Hofmann GE. Heat-shock proteins, molecular chaperones, and the stress response: evolutionary and ecological physiology. Annu Rev Physiol. 1999;61:243–282. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.61.1.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivey RA, Bruce BD. In vivo and in vitro interaction of DnaK and a chloroplast transit peptide. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2000;5:62–71. doi: 10.1043/1355-8145(2000)005<0062:IVAIVI>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivey RA, Subramanian C, Bruce BD. Identification of a Hsp70 recognition domain within the rubisco small subunit transit peptide. Plant Physiol. 2000;122:1289–1299. doi: 10.1104/pp.122.4.1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jindal S, Young RA. Vaccinia virus infection induces a stress response that leads to association of Hsp70 with viral proteins. J Virol. 1992;66:5357–5362. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.9.5357-5362.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlin S, Brocchieri L. Heat shock protein 70 family: multiple sequence comparisons, function and evolution. J Mol Evol. 1998;47:565–577. doi: 10.1007/pl00006413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumaraguru U, Gierynska M, Norman S, Bruce BD, Rouse BT. Immunization with chaperone-peptide complex induces low-avidity cytotoxic T lymphocytes providing transient protection against herpes simplex virus infection. J Virol. 2002;76:136–141. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.1.136-141.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumaraguru U, Rouse BT. Application of the intracellular gamma interferon assay to recalculate the potency of CD8(+) T-cell responses to herpes simplex virus. J Virol. 2000;74:5709–5711. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.12.5709-5711.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumaraguru U, Rouse RJ, Nair SK, Bruce BD, Rouse BT. Involvement of an ATP-dependent peptide chaperone in cross-presentation after DNA immunization. J Immunol. 2000;165:750–759. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehner T, Bergmeier LA, Wang Y, Tao L, Sing M, Spallek R, van der Zee R. Heat shock proteins generate beta-chemokines which function as innate adjuvants enhancing adaptive immunity. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:594–603. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200002)30:2<594::AID-IMMU594>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist S. The heat-shock response. Annu Rev Biochem. 1986;55:1151–1191. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.55.070186.005443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markwell J, Bruce BD, Keegstra K. Isolation of a carotenoid-containing sub-membrane particle from the chloroplastic envelope outer membrane of pea (Pisum sativum) J Biol Chem. 1992;267:13933–13937. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melcher A, Todryk S, Hardwick N, Ford M, Jacobson M, Vile RG. Tumor immunogenicity is determined by the mechanism of cell death via induction of heat shock protein expression. Nat Med. 1998;4:581–587. doi: 10.1038/nm0598-581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Multhoff G, Mizzen L, and Winchester CC. et al. 1999 Heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) stimulates proliferation and cytolytic activity of natural killer cells. Exp Hematol. 27:1627–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rico AI, Del Real G, Soto M, Quijada L, Martinez-A C, Alonso C, Requena JM. Characterization of the immunostimulatory properties of Leishmania infantum HSP70 by fusion to the Escherichia coli maltose-binding protein in normal and nu/nu BALB/c mice. Infect Immun. 1998;66:347–352. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.1.347-352.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert J, Menoret A, Basu S, Cohen N, Srivastava PR. Phylogenetic conservation of the molecular and immunological properties of the chaperones gp96 and hsp70. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:186–195. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200101)31:1<186::AID-IMMU186>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudiger S, Germeroth L, Schneider-Mergener J, Bukau B. Substrate specificity of the Dnak chaperone determined by screening cellulose-bound peptide libraries. EMBO J. 1997;16:1501–1507. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.7.1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlossman DM, Schmid SL, Braell WA, Rothman JE. An enzyme that removes clathrin coats: purification of an uncoating ATPase. J Cell Biol. 1984;99:723–733. doi: 10.1083/jcb.99.2.723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh-Jasuja H, Scherer HU, Hilf N, Arnold-Schild D, Rammensee HG, Toes RE, Schild H. The heat shock protein gp96 induces maturation of dendritic cells and down-regulation of its receptor. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:2211–2215. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(2000)30:8<2211::AID-IMMU2211>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somersan S, Larsson M, Fonteneau JF, Basu S, Srivastava P, Bhardwaj N. Primary tumor tissue lysates are enriched in heat shock proteins and induce the maturation of human dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2001;167:4844–4852. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.4844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava PK, Udono H, Blachere NE, Li Z. Heat shock proteins transfer peptides during antigen processing and CTL priming. Immunogenetics. 1994;39:93–98. doi: 10.1007/BF00188611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhoff U, Brinkmann V, and Klemm U. et al. 1999 Autoimmune intestinal pathology induced by hsp60-specific CD8 T cells. Immunity. 11:349–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh WC, Lu CZ, Gross CA. Structural features required for the interaction of the Hsp70 molecular chaperone DnaK with its cochaperone DnaJ. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:30534–30539. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.43.30534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suto R, Srivastava PK. A mechanism for the specific immunogenicity of heat shock protein-chaperoned peptides. Science. 1995;269:1585–1588. doi: 10.1126/science.7545313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzue K, Young RA. Adjuvant-free hsp70 fusion protein system elicits humoral and cellular immune responses to HIV-1 p24. J Immunol. 1996;156:873–879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todryk S, Melcher AA, Hardwick N, Linardakis E, Bateman A, Colombo MP, Stoppacciaro A, Vile RG. Heat shock protein 70 induced during tumor cell killing induces Th1 cytokines and targets immature dendritic cell precursors to enhance antigen uptake. J Immunol. 1999;163:1398–1408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udono H, Srivastava PK. Heat shock protein 70-associated peptides elicit specific cancer immunity. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1391–1396. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.4.1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Kelly CG, and Karttunen JT. et al. 2001 CD40 is a cellular receptor mediating mycobacterial heat shock protein 70 stimulation of CC-chemokines. Immunity. 15:971–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]