Abstract

Heme oxygenase 1 (HMOX1) degrades heme into biliverdin, which is subsequently converted to bilirubin by biliverdin reductase (BVRa or BVRb) in a manner analogous to the classic anti-oxidant glutathione-recycling pathway. To gain a better understanding of the potential antioxidant roles the BVR enzymes may play during development, the spatiotemporal expression and transcriptional regulation of zebrafish hmox1a, bvra and bvrb were characterized under basal conditions and in response to pro-oxidant exposure. All three genes displayed spatiotemporal expression patterns consistent with classic hematopoietic progenitors during development. Transient knockdown of Nrf2a did not attenuate the ability to detect bvra or bvrb by ISH, or alter spatial expression patterns in response to cadmium exposure. While hmox1a:mCherry fluorescence was documented within the intermediate cell mass, a transient location of primitive erythrocyte differentiation, expression was not fully attenuated in Nrf2a morphants, but real-time RT-PCR demonstrated a significant reduction in hmox1a expression. Furthermore, Gata-1 knockdown did not attenuate hmox1a:mCherry fluorescence. However, while there was a complete loss of detection of bvrb expression by ISH at 24 hpf, bvra expression was greatly attenuated but still detectable in Gata-1 morphants. In contrast, 96 hpf Gata-1 morphants displayed increased bvra and bvrb expression within hematopoietic tissues. Finally, temporal expression patterns of enzymes involved in the generation and maintenance of NADPH were consistent with known changes in the cellular redox state during early zebrafish development. Together, these data suggest that Gata-1 and Nrf2a play differential roles in regulating the heme degradation enzymes during an early developmental period of heightened cellular stress.

Keywords: biliverdin reductase, heme oxygenase, hematopoiesis, GATA-1, NRF2, cadmium, oxidative stress

1. Introduction

Oxidative stress results from an over-abundance of reactive oxygen species (ROS) which can damage major cellular macromolecules and ultimately lead to a disruption in cellular homeostasis. Efficient cellular responses to oxidative stress are crucial for proper development, survival, and proliferation. Accordingly, multiple mechanisms exist to protect cells from oxidative stress. Glutathione (GSH), a potent anti-oxidant that effectively quenches ROS, is often considered to be the frontline defense against cellular oxidative stress. Reduced GSH is maintained by the classic GSH recycling pathway via the action of NADPH-dependent glutathione reductase (GRX). However, in more recent years an analogous enzyme pathway, the biliverdin/bilirubin-recycling pathway, has been suggested to be an important anti-oxidant defense mechanism that plays an important role in protecting lipid-rich regions of the cell (Baranano et al., 2002; Stocker et al., 1987a, 1987b). Either of two isoforms of the heme-degrading enzyme, heme oxygenase (HMOX1 or HMOX2), is responsible for the first step in the catabolism of heme into carbon monoxide (CO), free iron, and the bile pigment biliverdin (Abraham and Kappas, 2008; Tenhunen et al., 1969). Biliverdin reductase (BVR) enzymes mediate the second step in which biliverdin is further reduced to bilirubin, which can function as an anti-oxidant through a recycling reaction mediated by BVR (Baranano et al., 2002; Stocker et al., 1987a, 1987b). Continuous regeneration of reduced GSH or bilirubin is dependent on the availability of reducing power in the form of NADPH, which is generated via the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) (Wu et al., 2011) as well as by other cytosolic and mitochondrial enzymes including isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) (Jennings and Stevenson, 1991; Jo et al., 2001), malate dehydrogenase (ME) (Pongratz et al., 2007), and the membrane bound nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase (NNT) (Kirsch and De Groot, 2001; Rydstrom, 2006; Yin et al., 2012).

While BVRb also utilizes NADPH as a cofactor, BVRa’s reductase domain has dual cofactor (NADH and NADPH) dual pH specificity (Kutty and Maines, 1981). BVRa is also further differentiated by the presence of multiple functional domains, such as a leucine zipper DNA-binding domain (Ahmad et al., 2002) that allows it to function as a transcription factor, as well as a serine/threonine/tyrosine kinase domain by which it has been demonstrated to participate in cellular signal transduction cascades via interaction with MAP kinases (Kutty and Maines, 1981; Lerner-Marmarosh et al., 2005; Salim et al., 2001). Furthermore, both CO and biliverdin can serve as signaling molecules and have been demonstrated to mediate anti-apoptotic and anti-inflammatory signaling processes (Bellner et al., 2011; Brouard et al., 2000; Otterbein et al., 2000; Petrache et al., 2000). Thus the various components of the HMOX/BVR enzymatic pathway have the potential to participate in cellular stress responses through a variety of different mechanisms.

We have previously characterized the sex-specific differences in basal expression of all four hmox zebrafish paralogs and both bvr genes, as well as differences in induction by cadmium (Cd) exposure in adult zebrafish tissues (Holowiecki et al., 2016). Furthermore, we have also characterized the basal expression of all six hmox and bvr genes during zebrafish development and in response to multiple pro-oxidant exposures (Cd, tert-butylhydroquinone, and hemin) (Holowiecki et al, 2016). To expand this characterization, we sought to investigate any changes in the spatial and temporal expression of bvra and bvrb during early zebrafish development under both basal conditions and in response to pro-oxidant exposure. Cd was chosen as the pro-oxidant since we have previously demonstrated that the Cd-inducibility of hmox1a and bvrb during zebrafish development is regulated in part by Nrf2a (Holowiecki et al., 2016). hmox1a expression was also characterized to add greater context to the observed changes in bvra and bvrb expression.

We also wanted to investigate the transcriptional regulation of these genes during development and in response to Cd exposure to determine how transcriptional regulation may influence spatial and temporal expression patterns. A previous study has demonstrated that hmox1a is expressed within the posterior blood island (PBI), an intermediate location of blood cell differentiation, at ~36 hours post fertilization (hpf) (Craven et al., 2005). Similarly, bvrb has been shown to be expressed within the intermediate cell mass (ICM), the site of embryonic erythrocyte formation during early zebrafish development, and this expression appears to be dependent on the erythroid specific transcription factor GATA-binding factor 1 (Gata-1) (Galloway et al., 2005), which is also known as nuclear factor erythroid 1 (Nf-e1). Furthermore, it is well established that HMOX1 is regulated by nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2), the master regulator of the oxidative stress response (Alam et al., 1999), and previous studies have provided evidence of a role for NRF2 in regulating BVR expression (Moon et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2011; Holowiecki et al., 2016). Interestingly, recent studies have suggested a novel developmental role for NRF2 as a regulator of hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) homeostasis (Merchant et al., 2011; Tsai et al., 2013). Therefore, we also characterized the changes in spatial expression of hmox1a, bvra, and bvrb during early zebrafish development in response to Cd exposure and after transient knockdown of Nrf2a via morpholino, as well as basal changes in spatial expression after Gata-1 knockdown. Finally, we also documented the developmental expression profiles of several cytoplasmic and mitochondrial enzymes that participate in the generation of NADPH, which is required for BVR function. These assessments were accomplished by using a combination of whole mount in situ hybridization (WISH), in vivo promoter analysis and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). The results of these experiments provide novel insights regarding the spatial and temporal expression patterns and the differential regulation of these heme degradation genes during zebrafish development. Collectively, these results suggest novel roles for the heme degradation genes in mediating erythropoiesis during developmental periods of heightened oxidative stress and raise new questions regarding the potential in vivo antioxidant function of this enzymatic pathway.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Fish husbandry

The TL (Tupfel/Long fin mutations) wild-type strain of zebrafish was used for all experiments. Fertilized eggs were obtained from multiple group breedings from a Mass Embryo Production System (MEPS; Aquatic Habitats, Apopka, FL) with ~200 fish at a ratio of 2 female per 1 male fish. Procedures used in these experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, Alabama, USA.

2.2 hmox1a in vivo promoter construct cloning

To create a hmox1a promoter construct, a 5.4 kb DNA region upstream of HO-1a exon 2 was amplified from zebrafish bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) DKEY-69E1 using Kapa HiFi DNA Polymerase (Kapa Biosystems, Inc., Boston, MA) and gene specific primers flanked by attB4 and attB1 sites. Entry clones and destination vectors for Tol2 transgenesis were kindly provided by the Chien lab (Kwan et al., 2007). To create a 5′ entry vector, the PCR product was recombined with donor vector #219 pDONRP4-P1R using Gateway® BP Clonase™. The transgenic construct was created by performing a 3-way recombination reaction using Gateway® LR Clonase II ™ Enzyme to combine the HO-1a promoter 5′ entry vector with middle vector #386 (containing mCherry) and 3′ entry vector #302 (containing the SV40 late polyA signal) into destination vector #395 (containing Tol2 inverted repeats and the cardiac myosin light-chain (cmlc2:eGFP) “heart marker” gene) to create pDestTol2CG2;hmox1a:pME-mCherry-p3EpolyA (Supplementary Figure 1). All Gateway® reactions were performed according to manufacturer’s instructions. One Shot® Top 10 cells (Invitrogen, Life Technologies™ Corporation, Carlsbad, CA) were used for transformation of the transgenic DNA construct and an EndoFree Plasmid Maxi Kit (QIAGEN Inc, Valencia, CA) was used for purification and removal of any potential endotoxins.

2.3 Generation of hmox1a stable transgenic lines and in vivo promoter analysis

To generate the stable transgenic line Tg(hmox1a:mCherry;cmlc2-eGFP)mjj1, embryos at the 1–2 cell stage were co-injected with 50 pg of the HO-1a promoter construct (pDestTol2CG2; hmox1a:pME-mCherry-p3EpolyA) and 5 pg of in vitro transcribed transposase mRNA in a 2.1 nL volume using a Narishige IM-300 microinjector. Injection volumes were calibrated by injecting solutions into mineral oil and measuring the diameter of the sphere with a stage micrometer (volume = 4/3πr3; 160 μm diameter is equivalent to 2.1 nl). Embryos were screened for expression of the cmlc2:eGFP heart marker at 24–48 hpf and subsequently screened for mCherry expression daily from 1 to 5 days past fertilization (dpf). Embryos strongly expressing the mCherry transgene were raised to adulthood and crossed with wild-type TL fish to create F1 heterozygous progeny as described by(Kawakami, 2007; Kawakami et al., 2000). F1 progeny were subsequently raised to adulthood and crossed with wild-type TL fish to create F2 Tg(hmox1a:mCherry;cmlc2-eGFP)mjj1.

We initially documented hmox1a:mCherry fluorescence in Tg(hmox1a:mCherry;cmlc2-eGFP)mjj1 embryos starting at ~20–24 hpf, and continued to do so every 24 hours for up to 14 days. To more specifically identify timepoints of expression during early development, embryos were collected from a mating between one F2 male HO-1a transgenic fish and two wild type TL females. Changes in hmox1a driven mCherry fluorescence were documented in embryos every 3 hours starting at ~22 hpf and continuing through 72 hpf. All fluorescent imaging was performed using a Photometrics CoolSNAP ES2 camera attached to a Nikon AZ100M microscope. To ensure that the observed fluorescence was real and not auto-fluorescence, wild-type embryos were imaged at comparable timepoints.

2.4 Gata-1 and Nrf2a transient knockdown via morpholino

The previously described Nrf2a MO (5′CATTTCAATCTCCATCATGTCTCAG-3′) was obtained from Gene Tools, LLC (Philomath, OR)(Kobayashi et al., 2002; Timme-Laragy et al., 2012). The Gata-1 MO (5′-CTGCAAGTGTAGTATTGAAGATGTC-3′) was a generous gift from Dr. Leonard I. Zon (Harvard Medical School). The standard control morpholino (5′-CCTCTTACCTCAGTTACAATTTATA-3′) from Gene Tools was used to account for any nonspecific effects associated with microinjection. The control and Nrf2a MOs are fluorescein tagged for screening purposes to guarantee that only successfully injected embryos were used for the subsequent experiments. The Nrf2a MO was diluted to 0.18 mM and the Gata-1 MO was diluted to 0.5 mM in nuclease-free water. The control MO was diluted to 0.18 mM and 0.5 mM to serve as injection controls for both gene-specific MOs. A Narishige IM-300 microinjector was used to inject 2.1 nl of morpholino into embryos at the two- to four-cell stage. Injection volume calibrations were performed as described in the transgenic section above. At 3 hpf, embryos were sorted to remove unfertilized eggs or abnormally developed embryos. MO injection studies utilized wild-type TL embryos for the WISH studies. Additionally, embryos were obtained from hmox1a transgenic fish as described in the previous section for in vivo promoter analysis after MO injection.

2.5 Whole mount in situ hybridization

bvra, bvrb, and hmox1a sense and antisense digoxigenin (DIG) labeled RNA probes were synthesized using the Roche Dig RNA Labeling Kit (SP6/T7) from cDNA subcloned into pGEM®-T Easy Vector (Promega, Madison, WI). The bvra probe is 413 bp in length and includes the first 83 bp of the 3′ UTR. The bvrb probe is located within the coding sequence and is 460 bp in length. Finally, the hmox1a probe is 398 bp in length, of which 314 bp are located within the 3′ UTR. Primers used for probe generation are listed in the Table 1. Wild-type TL zebrafish embryos were collected at 20, 24, 28, 36, 48, 72, 96, and 120 hpf. Embryos between 20–48 hpf were manually dechorionated. All embryos were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), stored methanol at 4 °C and rehydrated in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) as needed for WISH. A 3% hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)/0.5% potassium hydroxide (KOH) solution was used to remove pigmentation at later timepoints (≥ 48 hpf) as described by Thisse and Thisse (Thisse and Thisse, 2008). Procedures for WISH were performed essentially as described by (Thisse and Thisse, 2008). Fixed embryos were rehydrated and permeabilized in a 10 μg/ml solution of proteinase K (Roche Diagnostics) to allow for probe entry. Prior to the addition of probes, embryos were subjected to a pre-hybridization solution which contained yeast tRNA (2 μg/ml), heparin (50 μg/ml), 50% deionized formamide, 5x SSC, 0.1% Tween 20, and 1 M citric acid between 2–4 hours at 70°C. Sense or antisense probes (~7.5 ng) suspended in pre-hybridization solution were added and allowed to incubate overnight at 70 °C. To determine if any observed staining was the result of endogenous phosphatase activity, embryos at each time point were processed under the same conditions without the addition of a probe (Images of no probe controls are available in the Supplementary Figures). The next day, embryos were washed and incubated with blocking buffer for 4 hours. After 4 hours the blocking buffer was removed and replaced with Anti-Digoxigenin-AP, Fab fragments (Roche Diagnostics) made up in blocking buffer (1:10,000) and incubated overnight at 4 °C. The following day the antibody was removed and the embryos were washed 6 times in PBS with 0.1% tween (PBST). To eliminate background staining at later timepoints a pre-adsorbed antibody was prepared by processing a group of embryos in parallel until the pre-hybridization step, at which point a 1:1000 dilution of the antibody was added to the embryos and rocked at room temperature for 2 hours prior to storage overnight at 4°C (Chitramuthu and Bennett, 2013). This pre-adsorbed antibody was then further diluted to a final ratio of 1:10,000 in blocking buffer the next day and added to the embryos which were incubated overnight at 4 °C. Following antibody removal and PBST washes, embryos were further washed in fresh alkaline Tris buffer consisting of 1M Tris-HCl (pH=9.5),1 M MgCl2, 5M NaCl, and 20% Tween 20, stained with BM-Purple AP Substrate, and allowed to develop at room temperature in the dark (Roche Diagnostics). Zebrafish embryos were visualized with a Nikon AZ100M microscope and photographed using a Nikon Digital Sight DS-F-1 camera.

Table 1.

Real-Time RT-PCR and Cloning Primers

| Gene | Real-Time RT-PCR | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| hmox1a | Forward | 5′-GCTTCTGCTGTGCTCTCTATACG-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-CAATCTCTCTCAGTCTCTGTGC-3′ | |

| bvra | Forward | 5′-CAGGCAGTTTCTGGAGGCAGG-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-CCAGACCCTTCTGTTGAGC-3′ | |

| bvrb | Forward | 5′-GCATGTCAGCATTCCTCTTGTGG-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-CACCAGCAATATGTGGAGG-3′ | |

| g6pd | Forward | 5′-ATGATGTGCGGGATGAGAAGGTAAA-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-TGCTGTGGCAAATGTAGCCTGAGT-3′ | |

| pgd | Forward | 5′-GGCTGTACAGGATTGTCAGGACT-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-CGTCATAGAAGGACAGTGCGGT-3′ | |

| idh cyto | Forward | 5′-ATGGGAGCTCATAAAAGAGAAACTCAT-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-CCTCAACTGTTACCTTATCATCGGTG-3′ | |

| idh mito | Forward | 5′-ATCTGGGAGTTCATTAAAGAAAAGCTT-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-GTAATAGTGGCGCATTTGACAGCAACG-3′ | |

| me cyto | Forward | 5′-GACCTTCAGGAGACCGAGGG-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-AGGCCCAGAATCCTCTCTCCAT-3′ | |

| me mito | Forward | 5′-ACGCAGTAATCCTCTCGACAAATAC-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-GTGTAGACGATAGGCATGAATTCTTC-3′ | |

| nnt | Forward | 5′-GCGCTGAAGGCTTCCTGCTGAAT-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-AGGGATCGGTTCATGGCCACACA-3′ | |

| Gene | Gateway Cloning | Sequence |

| hmox1a | Forward | 5′GGGGACAACTTTGTATAGAAAAGTTGTGCACTTATCAGGCATAGTAAATGGGCA-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-GGGGACTGCTTTTTTGTACAAACTTGCTCTAAAAAAACAGATTGCCCTATTTG-3′ | |

| Gene | WISH Cloning | Sequence |

| bvra | Forward | 5′-TAAGAAAACCACATCAAAGGCTG-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-GCACTTCAGTTATCTGTCTCTATA-3′ | |

| bvrb | Forward | 5′-TGTGGCGATATTTGGCTGCACGG-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-ACCATCAGTACCAACCTGTTATTTTCGC-3′ | |

| hmox1a | Forward | 5′-ATTGATATCCTACAGCACAAAGATGGAC-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-TATGGATCCAGTAAAAAAAACTAATCTG-3′ |

2.6 Developmental time series

A large batch (>3000) of embryos was generated by active breeding of the fish in a MEPS system (Aquatic Habitats) for 60 minutes. After 60 minutes embryos were collected and transferred to large Petri dishes (150 mm diameter) at a density of 100 embryos per 100 ml of 0.3x Danieau’s solution at 28.5 °C. Embryos were screened within 4 hours of fertilization for normal development and subsequently separated into 100 mm Petri dishes at a density of 20 embryos per dish in 25 ml of 0.3x Danieau’s solution at 28.5 °C under a 14 hour light/10 hour dark cycle with water changes every 24 hours. Three biological replicates of 20 pooled embryos were collected at several developmental timepoints (24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 hpf). Embryos were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until RNA isolation.

2.7 Cd exposure experiment

Non-injected, control MO-injected and Nrf2a MO-injected embryos were exposed to 50 μM Cd for 8 hours starting at 96 hpf. Cd dosing experiments were performed in 100 mm plastic petri dishes as a ratio of 1 embryo per 1 mL 0.3X Danieau’s alone or with 50 μM Cd. After the 8 hour exposure, larvae were collected for both targeted gene expression profiling and WISH. 20 embryos from a single petri dish were pooled together and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen to produce a single biological replicate for the real-time RT-PCR analysis (total of 3 biological replicates). The remaining embryos were fixed in 4% PFA overnight before being transferred to methanol for storage until spatiotemporal gene expression analysis by WISH. Each WISH analysis utilized a minimum of 20 individual embryo-larvae for either the sense or anti-sense probes, as well as the no-probe controls.

2.8 Gene expression assessment by real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA was prepared from embryos using the TRIzol® reagent (Life Technologies, Invitrogen) protocol. The qScript™ cDNA Synthesis Kit (Quanta Biosciences, Gaithersburg, MD) was used to generate cDNA from 1 μg total RNA per manufacturer’s instructions. PerfeCTa® SYBR® Green Supermix for iQ™ (Quanta Biosciences, Gaithersburg, MD) was used for real-time RT-PCR experiments in a MyiQ2 Two-Color Real-Time PCR Detection system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) under the following conditions: 95°C for 3 min, 95°C for 15s/60°C for 30 sec (40 cycles). To ensure that only a single product was amplified, all real-time RT-PCR experiments were followed with a melt curve analysis. 18S ribosomal RNA was used as the house-keeping gene for normalization between individual samples. Gene expression for the developmental time series was quantified by generating a standard curve using serially diluted plasmids containing full length copies of the transcripts. Relative fold change in the morpholino experiments was calculated using the delta Ct formula and normalized to non-injected controls (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001).

2.9 Promoter enhancer motif identification

The 8 kb promoter regions upstream of the transcription start site (exon 1) in the zebrafish bvra, and bvrb genes, and the 4.5 kb promoter region upstream of the transcription start site (exon 1) in the zebrafish hmox1a gene were searched for consensus antioxidant-response element (ARE) NRF2 binding motif (RTGAYNNNGC) (Venugopal and Jaiswal, 1998), GATA binding motif (WGATAR), GATA-1,2 & 3 erythroid high affinity binding motif (AGATAA) and GATA-2 & 3 binding motif (AGATCTTA) (Ko and Engel, 1993), as well as the PU.1 binding motif (GAGGAA) (Solomon et al., 2015) and NF-E2 binding motif (TGCTGASTCATY) (Pratt et al., 2002) using ApE software (http://biologylabs.utah.edu/jorgensen/wayned/ape/).

2.10 Statistical analysis of gene expression profiling

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism 5 software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). For the developmental time series, statistical significance in transcript expression compared to 24 hpf embryos was determined using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a Dunnett’s post hoc test. For the real-time RT-PCR analysis on Cd-exposure 96 hpf larvae, statistical significance in transcript expression was determined using a Student’s t-test (*p-value < 0.05). For the morpholino experiments, statistical significance in transcript expression compared to non-injected embryos was determined using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a Bonferroni’s post hoc test.

3. Results

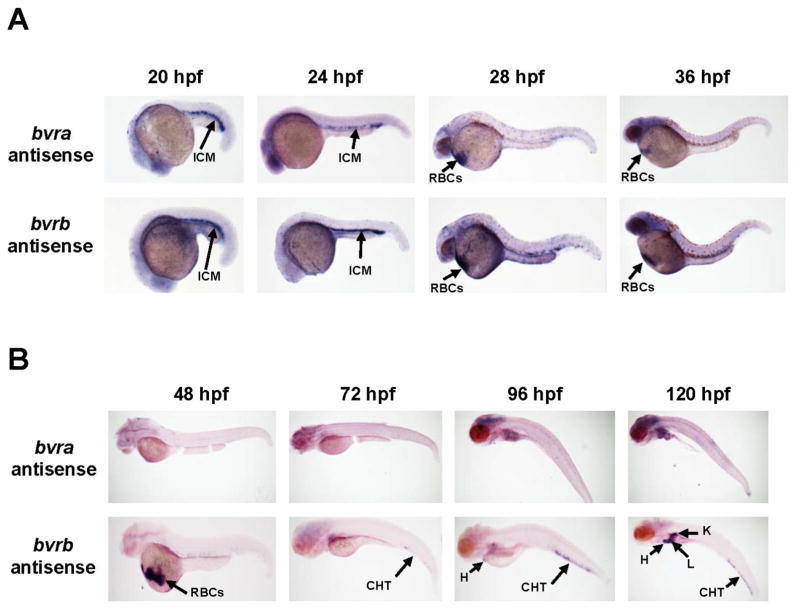

3.1 Spatial and temporal expression of bvra and bvrb

To determine the spatial and temporal expression patterns of bvra and bvrb, WISH was performed at timepoints from early development thru later larval stages. Between 20–24 hpf, both bvra and bvrb were strongly expressed within the intermediate cell mass (ICM) (Figure 1A), the embryonic site of erythropoiesis (Detrich et al., 1995) While bvrb expression remained strongly detected throughout the ICM at 28 hpf, bvra expression became restricted to the posterior blood island (PBI). Furthermore, both transcripts were detectable within circulating blood cells in the Ducts of Cuvier at 28 hpf (Figure 1A). By 32 hpf bvra transcripts were no longer detectable within the PBI and remained confined to circulating erythrocytes (Figure 1A). In contrast, bvrb transcripts were expressed in both the PBI and in circulating blood cells. However, by 36 hpf neither isoform was detectable within the PBI, but both bvra and bvrb expression persisted within circulating erythrocytes (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Changes in bvr expression during primitive and definitive hematopoiesis.

(A) bvra and bvrb have overlapping expression patterns during primitive hematopoiesis within the ICM and within primitive RBC’s. (B) During definitive hematopoiesis bvra was not detected using WISH. bvrb was expressed within circulating RBC’s, as well as the CHT, heart, liver, and kidney (96 and 120 hpf). Sense probe and no probe controls showed little background staining (Supplementary Figures 2 and 3). Abbreviations: CHT = caudal hematopoietic tissue; H = heart; hpf = hours past fertilization; ICM = intermediate cell mass; K = kidney; PBI= posterior blood island; RBC’s = red blood cells.

At 48 hpf, Bbvra expression was no longer detectable while bvrb expression remained strong within circulating blood cells visible around the yolk sac (Figure 1B). At the later timepoints (72, 96 and 120 hpf), bvrb progressed from being faintly detected in the PBI to strongly expressed within the caudal hematopoietic tissue (CHT), a transient location of further blood cell differentiation (Figure 1B). Furthermore, at the later timepoints (100 and 124 hpf), bvrb was also detectable in visceral tissues (heart, liver, and kidney). In contrast, bvra expression was not detectable at any of these later timepoints (Figure 1B).

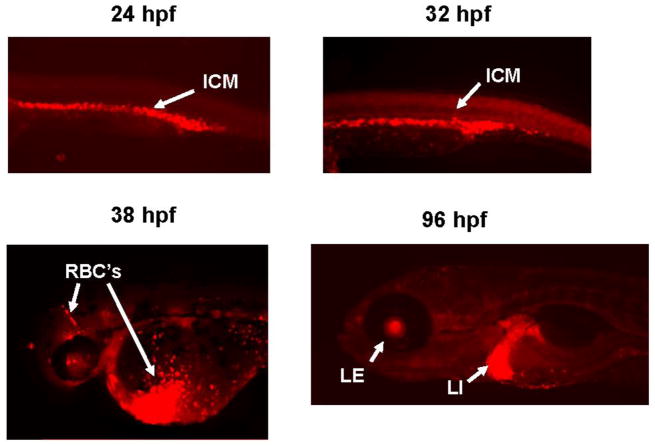

3.2 hmox1a in vivo expression during zebrafish development

Although previous studies have demonstrated hmox1a expression patterns consistent with erythropoiesis (Thisse et al., 2004; Craven et al., 2005) as seen with bvra and bvrb (Figure 1), we wanted to confirm this expression with a more thorough temporal assessment and look for any novel tissue-specific expression patterns. Therefore, a stable transgenic line in which the promoter region of hmox1a drives expression of the mCherry fluorescent protein was created to further characterize hmox1a transcriptional regulation and increase the sensitivity of detection. Within this transgenic line, we observed mCherry fluorescence within the ICM between 24–32 hpf (Figure 2). By ~ 38 hpf we observed mCherry fluorescence within circulating erythrocytes. Consistent with other reports showing hmox1a expression within zebrafish liver tissue (Nakajima et al., 2011), hmox1a-driven mCherry expression was observed in liver tissues at 96 hpf, as well as novel observation of expression in the lens region of the eye (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Changes in hmox1a-driven mCherry spatial expression during zebrafish development.

Strong mCherry expression driven by a zebrafish hmox1a promoter construct is visible within the ICM at 24 and 32 hpf. By 38 hpf, mCherry expression was detected within circulating RBC’s. By 96 hpf, mCherry expression was observed in the liver and lens region of the eye. ICM = intermediate cell mass, RBC’s= red blood cells, LE – Eye lens, LI - Liver.

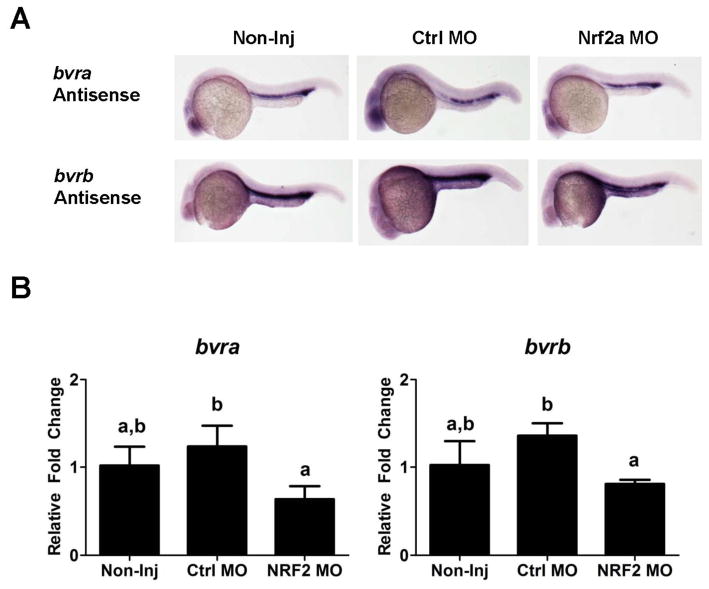

3.3 Effects of Nrf2a knockdown on zebrafish heme degradation genes within hematopoietic tissues

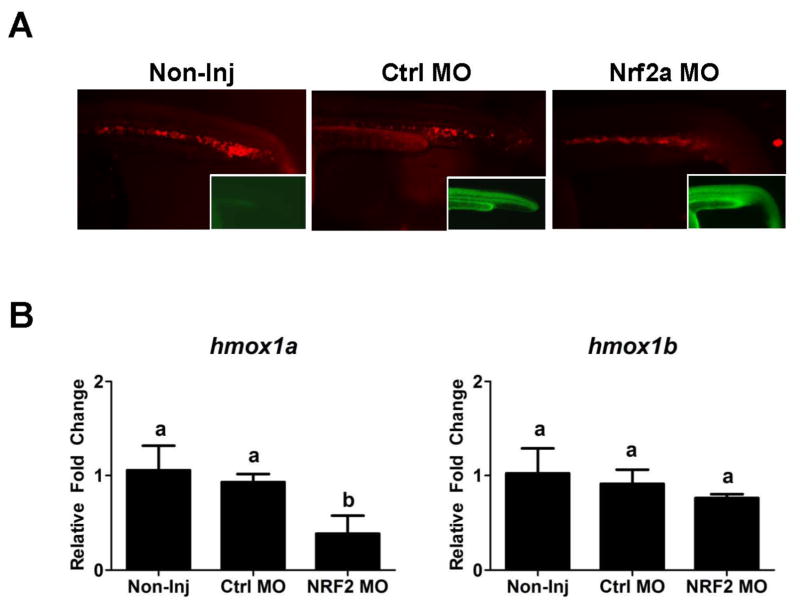

Since NRF2 is a known transcriptional regulator of HO-1 (Alam et al., 1999) and has been implicated in the regulation of HSC’s (Merchant et al., 2011; Tsai et al., 2013), Nrf2a knockdown experiments were performed to determine if it played a role in the regulation of hmox1a, bvra or bvrb during erythropoiesis. There were no observable differences in our ability to detect bvra or bvrb expression within the ICM of the Nrf2a morphants at 24 hpf by WISH (Figure 3A). While there was also no statistically significant difference between non-injected controls and control morphants (Ctrl MO), the slightly higher expression of both genes in the control morphants did result in a statistically significant difference in quantitative expression between the control morphants and Nrf2a morphants as assessed by real-time RT-PCR (Figure 3B). However, all changes were less than 1.5-fold compared to the non-injected controls, suggesting that Nrf2a was not playing a major role in the regulation of either bvra or bvrb during erythropoiesis. Nrf2a morphants also had observable hmox1a-driven mCherry expression within the ICM (Figure 4A). However, Nrf2a knockdown resulted in a statistically significant reduction (~60%) in hmox1a expression between the non-injected controls and control morphants at 24 hpf based on real-time RT-PCR (Figure 4B). In contrast, there was no statistically significant change in hmox1b expression in the NRF2a morphants.

Figure 3. Effects of Nrf2a MO knockdown on bvr expression during primitive hematopoiesis.

(A) bvra and bvrb expression in non-injected, control, and Nrf2a morphants at 24 hpf. Sense probe and no probe controls showed little background staining (Supplementary Figure 4). (B) Relative transcript abundance of bvra and bvrb in non-injected, control MO, and Nrf2a MO injected embryos at 24 hpf was determined via qPCR. Presented is the relative fold change in expression compared to non-injected (Non-inj) control embryos. Statistical significance in transcript expression in comparison to 24 hpf embryos was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test (*p-value < 0.05). All values are normalized to 18S ribosomal RNA. n = 3 biological replicates of 20 pooled embryos. hpf = hours past fertilization; MO = morpholino

Figure 4. Effects of Nrf2a knockdown on ho-1a:mCherry expression.

(A) Fluorescent images of Tg(hmox1a:mCherry) embryos at 24 hpf demonstrate the NRF2a knockdown has no effect on ho-1a:mCherry expression within the ICM. The control MO and NRF2a MOs are fluorescein tagged for screening purposes (images provided bottom right corner). (B) Relative transcript abundance of hmox1a and hmox1b in non-injected, control MO, and Nrf2a MO injected embryos at 24 hpf was determined via qPCR. Presented is the relative fold change in expression compared to non-injected (Non-inj) control embryos. Statistical significance in transcript expression in comparison to 24 hpf embryos was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test (*p-value < 0.05). All values are normalized to 18S ribosomal RNA. n = 3 biological replicates of 20 pooled embryos. hpf = hours past fertilization.

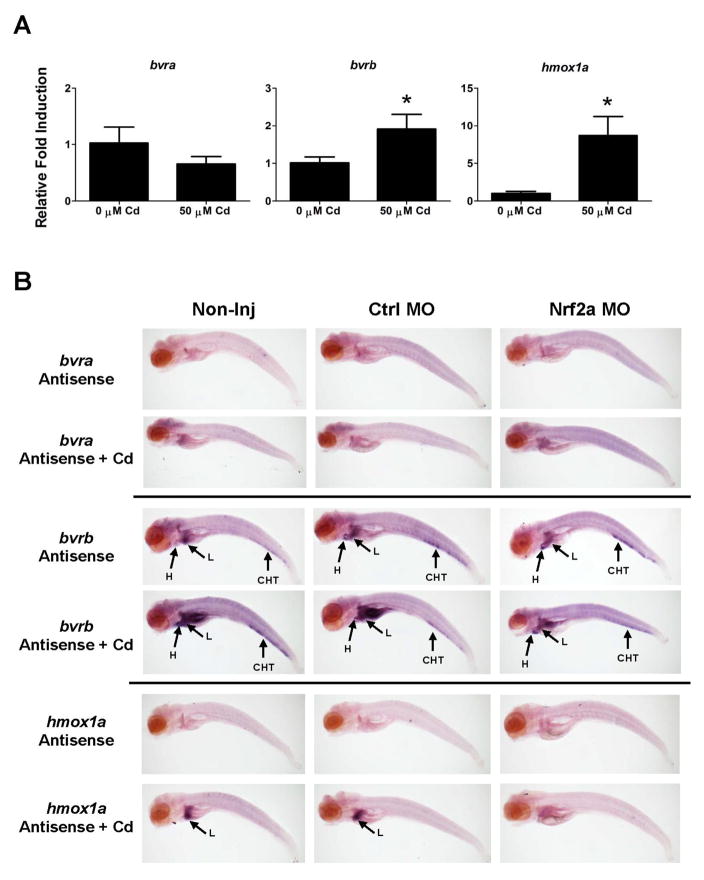

3.4 Evaluation of the role of Nrf2a in regulating the Bvr stress response

To assess any changes in the spatial expression of bvra or bvrb in response to pro-oxidant exposure, we performed WISH on Cd-treated 96 hpf embryos. Furthermore, since we have previously demonstrated a role for Nrf2a in regulating the induction of bvrb in older zebrafish eleutheroembryos in response to Cd exposure (Holowiecki et al, 2016), we also investigated any changes in spatial expression of bvra and bvrb in Nrf2a morphants after Cd-treatment. Finally, although spatial expression of hmox1a has been well characterized in older zebrafish eleutheroembryos in response to pro-oxidant exposures, we included an assessment of hmox1a expression for greater context and to demonstrate successful Nrf2a knockdown. All WISH results were further supported by real-time RT-PCR. Both hmox1a and bvrb were significantly upregulated following exposure to Cd while bvra transcripts slightly decreased (Figure 5A). Similarly, at 96 hpf, bvra expression remained undetectable as assessed using WISH in non-treated and Cd-treated eleutheroembryos (Figure 5B). bvrb remained easily detectable within the liver, heart, kidney, and CHT of Nrf2a morphants compared to non-injected embryos and those injected with the standard control MO (Figure 5B). While Cd-treatment appeared to increase bvrb staining intensity within the visceral tissues (Figure 5B), spatial expression remained consistent. In addition, Cd-exposed Nrf2a morphants did not appear to have as strong of a bvrb signal within the CHT, heart, liver, kidney and intestines in comparison to non-injected and control morphants, but the spatial expression remained consistent. As expected, Nrf2a knockdown resulted in a loss of WISH hmox1a staining in Cd-challenged Nrf2a morphants (Figure 5B).

Figure 5. Nrf2a Knockdown Results in a Decrease in bvrb Expression in Cd Challenged Embryos at 96 hpf.

(A) Real-time RT-PCR was used to quantify changes in hmox1a, bvra and bvrb expression following exposure to Cd. Embryos were challenged for 8 hours with 50 μM Cd starting at 96 hpf. Presented is the relative fold change in expression compared to 0 μM Cd control embryos. Statistical significance in comparison to control embryos was determined using a standard Student’s t-test (*p-value < 0.05). All values are normalized to 18S ribosomal RNA. n = 3 biological replicates of 20 pooled embryos. (B) bvra and bvrb expression in non-injected embryos (left), control morphants (middle), and NRF2a morphants (right) in control embryos or embryos challenged with 50 μM Cd starting at 96 hpf. Sense probe and no probe controls showed little background staining (Supplementary Figure 5). Abbreviations: CHT = caudal hematopoietic tissue, H = heart, I = intestines, L = liver, K = kidney, MO = morpholino.

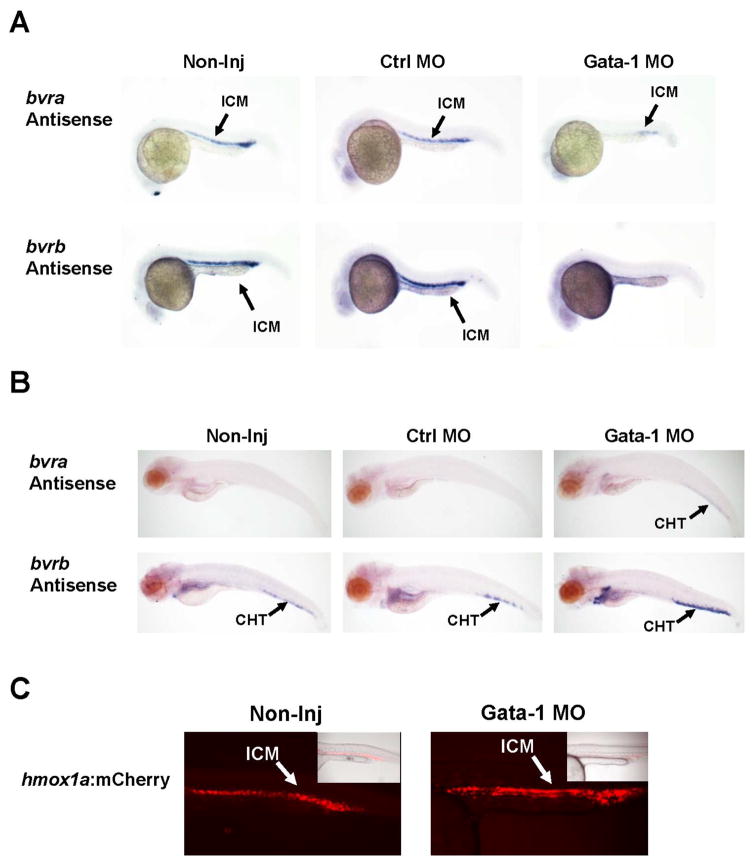

3.5 Effects of Gata-1 knockdown on heme degradation genes during primitive and definitive hematopoiesis

Since a previous study demonstrated a potential role for Gata-1 in the regulation bvrb within the ICM (Galloway et al., 2005) and there was no major change in the spatial expression in Nrf2a morphants (Figures 3 and 5), we performed in situ hybridization to determine if Gata-1 played a role in regulating both bvra and bvrb at 24 and 96 hpf, timepoints which span the “primitive” and “definitive” waves of hematopoiesis. Gata-1 morphants displayed a complete loss of detection of bvrb expression within the ICM at 24 hpf (Figure 6A). However, while bvra expression was significantly diminished in Gata-1 morphants, some detectable expression persisted within the posterior region of the ICM at 24 hpf. By 96 hpf, the Gata-1 morphants displayed strong staining for bvrb in the CHT, heart, liver, and kidney compared to non-injected and control MO-injected embryos (Figure 6B). Although bvra expression was not detected in non-injected or control MO fish at 96 hpf, Gata-1 morphants displayed modest staining within the CHT at this timepoint (Figure 6B). Finally, mCherry expression within the ICM of the hmox1a:mCherry transgenic line was not attenuated in Gata-1 morphants at 24 hpf (Figure 6C).

Figure 6. Effects of Gata-1 knockdown on zebrafish heme degradation genes within hematopoietic tissues.

(A) In situ hybridization at 24 hpf in non-injected embryos, control morphants, and Gata-1 morphants. Embryos were injected with a Gata-1 MO and the standard control MO. Sense probe controls showed no background staining (Supplementary Figure 6). (B) In situ hybridization at 96 hpf in non-injected embryos, control morphants, and Gata-1 morphants. bvra was not detected at 96 hpf in non-injected embryos. However, bvra expression was faintly detected within the CHT of Gata-1 morphants. Conversely, while bvrb expression was detected in the CHT of non-injected embryos, Gata-1 morphants showed stronger staining within the CHT as well as the heart, kidney, and liver. (C) Fluorescent images of wild type and Gata-1 MO injected Tg(ho-1a:mCherry) at 24 hpf. Merged images (mCherry and brightfield) are displayed in the top right corners of wild-type zebrafish to help illustrate anatomical location of focus. Abbreviations used are as follows: ICM = intermediate cell mass, MO = morpholino, CHT= caudal hematopoietic tissue, H= heart, L= liver, K= kidney, hpf = hours past fertilization, WT = wild-type.

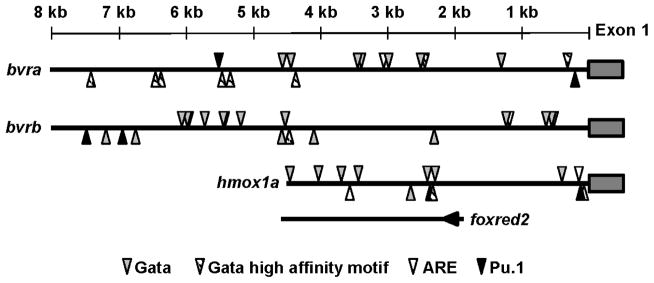

3.6 Transcription factor binding motifs in the bvr and hmox1a gene promoter regions

To gain further insight into the potential transcriptional regulation of bvra, bvrb and hmox1a during zebrafish development, the 8 kb region upstream of exon 1 for both bvra and bvrb, and the 4.5 kb region upstream of hmox1a were searched for binding motifs consistent with factors related to hematopoiesis and with spatio-temporal expression similar to that observed for bvra, bvrb and hmox1a. In addition to the previously documented ARE motifs in the promoter regions of all three genes (Holowiecki et al., 2016), all three promoter regions contained multiple motifs consistent with the GATA consensus binding motif (WGATAR) (Ko and Engel, 1993) (Figure 7). Furthermore, all three genes contained the GATA erythroid consensus motif (AGATAA) that has a high affinity for all three GATA factors (GATA-1, -2, and -3) (Ko and Engel, 1993), with the bvra promoter region being particularly enriched in this motif (Figure 7). All three gene promoters also contained multiple copies of the PU.1 binding motif (GAGGAA) (Solomon et al., 2015), while none of the gene promoters contained motifs consistent with an NF-E2 binding motif (TGCTGASTCATY) (Pratt et al., 2002) or the binding motif (AGATCTTA) preferentially targeted by GATA-2 and GATA-3 (Ko and Engel, 1993). Finally, the current annotation of the zebrafish genome (GRCz10) demonstrates that hmox1a shares a promoter region (approximately 1.8 kb) with the foxred2 (FAD-dependent oxidoreductase domain containing 2) gene which consists of ten exons, is ~14 kb in length and located on the opposite strand in an inverted orientation compared to hmox1a (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Schematic of transcription factor binding motifs in hmox1a and bvr gene promoters.

Position and orientation of the antioxidant-responsive element (ARE), Gata factor binding motifs, and the Pu.1 binding motif. Arrowheads above the line represent motifs on the sense DNA strand, while arrowheads below the line represent motifs on the antisense DNA strand. The bottom line with an arrowhead demonstrates the start of the foxred2 gene that shares a promoter region with hmox1a and is in the opposite orientation compared to hmox1a.

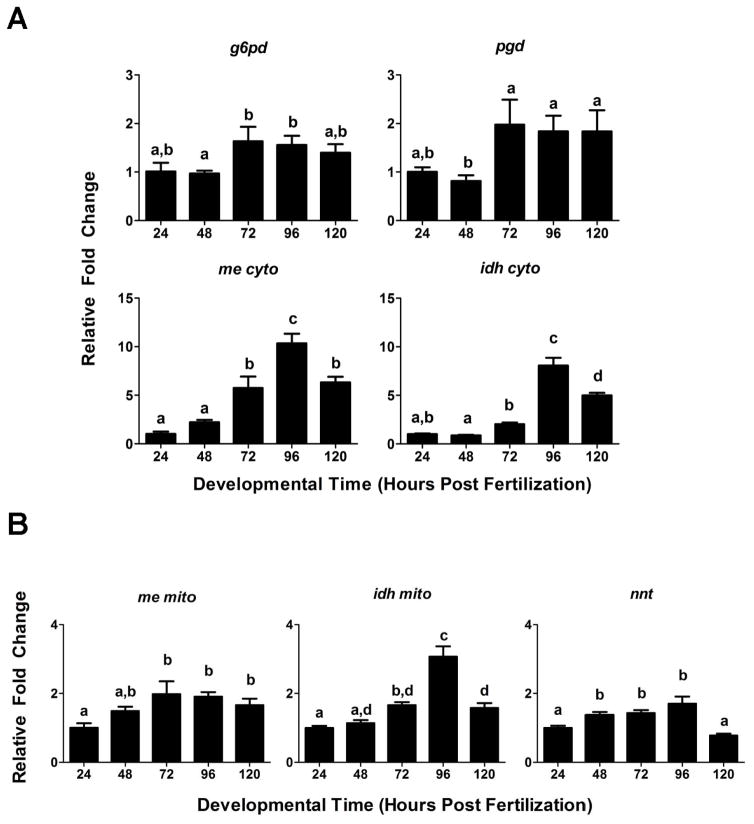

3.7 Developmental expression of genes involved in maintaining cellular NADPH levels

A favorable redox environment is necessary for the continued maintenance of cellular anti-oxidants. NADPH maintains cellular homeostasis by serving as the preferred electron donor in cytosolic redox reactions associated with the amelioration of oxidative stress and is utilized by BVR to regenerate bilirubin from biliverdin, as well as by glutathione reductase to regenerate reduced GSH. Accordingly, we evaluated changes in expression of major producers of NADPH between 24–120 hpf, e.g., mitochondrial nnt, cytosolic and mitochondrial idh (idh cyto and dh mito), cytosolic and mitochondrial me (me cyto and me mito), phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (pgd), and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (g6pd) (Jennings and Stevenson, 1991; Seung Hee Jo et al., 2001; Kirsch and de Groot, 2001; Rydstrom, 2006; Agledal et al., 2010, Gorrini et al., 2013) (Figure 8). Interestingly, all of these genes displayed a statistically significant increase in expression by 72 hpf (Figure 8). Furthermore, me cito, idh cito and idh mito demonstrated even greater peaks in expression by 96 hpf that were moderately reduced by 120 hpf (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Developmental expression of cytosolic and mitochondrial genes responsible for producing NADPH.

Developmental changes in expression of (A) cytosolic and (B) mitochondrial NADPH producing genes. Presented is the relative fold change in expression compared to 24 hpf embryos. Statistical significance in expression in comparison to 24 hpf embryos was determined using one-way ANOVA (*p-value < 0.05) followed by a Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test (*p-value < 0.05). All values are normalized to 18S ribosomal RNA. n = 3 biological replicates of 20 pooled embryos. g6pd = glcose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, idhc = cytosolic isocitrate dehydrogenase, idhm = mitochondrial isocitrate dehydrogenase, me cyto = cytosolic malic enzyme, me mito = mitochondrial malic enzyme, nnt = nicatinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase, pgd = phosphogluconate dehydrogenase.

4. Discussion

The heme degradation pathway facilitates the metabolism of heme into excretable byproducts that may also have significant biological functions. Specifically, heme oxygenase enzymes (HMOX1, HMOX2) catalyze the breakdown of heme into CO, free iron, and the bile pigment biliverdin. Subsequently, a reputed anti-oxidant cycling pathway catalyzed by biliverdin reductase enzymes (BVRa or BVRb) utilizes cytosolic NADPH to reduce biliverdin to bilirubin (Doré et al., 1999; Barañano and Snyder, 2001; Barañano et al., 2002). This pathway is thought to confer protection against oxidative stress through the protective benefits of bilirubin in a manner analogous to the classic GSH recycling pathway (Baranano et al., 2002). Very little is known regarding the functional role, expression patterns or transcriptional regulation of these enzymes during embryonic development. We report here the results from a combination of real-time RT-PCR, in situ hybridization and in vivo promoter analysis techniques used to evaluate changes in the spatial and temporal patterns of hmox1a, bvra and bvrb basal expression during zebrafish development, and in response to Cd exposure. We also provide functional evidence for the differential roles of Gata-1, the master regulator of erythropoiesis, and Nrf2a, the master regulator of the oxidative stress response in zebrafish, in the regulation of these heme degradation genes during zebrafish development.

4.1 Potential significance of hmox1a and bvr expression during zebrafish erythropoiesis

Hematopoiesis is a highly conserved process that is dependent on the spatial and temporal expression of multiple transcription factors that regulate the developmental progression of hematopoietic stem cells into differing blood cell lineages. In zebrafish, hematopoiesis occurs in three waves, a primitive wave, a pro-definitive wave and a definitive wave (Ciau-Uitz et al., 2014). Early in development (~14 hpf), transcription factors necessary for blood and endothelial cell formation are expressed within the blood islands of the anterior lateral mesoderm (ALM) and the posterior lateral mesoderm (PLM), which produce myeloid and erythroid cells, respectively (Amigo et al., 2009; Bennett et al., 2001; Davidson et al., 2003; Dooley et al., 2008). These primitive blood cells arise within a region termed the intermediate cell mass (ICM) (Detrich et al., 1995) and begin to actively circulate at ~24 hpf, marking the onset of the primitive wave. The second wave, the pro-definitive wave, begins with the production of multipotent erytho-myeloid progenitors (EMPs) from the posterior blood island (PBI) (Bertrand et al., 2007). These EMPs subsequently migrate to the caudal hematopoietic tissue (CHT), a transient location in which they differentiate into erytho-myeloid and lymphoid lineages (Jin et al., 2007; Murayama et al., 2006). Although controversial, a subset of these EMPs from the PBI is thought to directly seed the kidney marrow, effectively by-passing the transient stage within the CHT (Bertrand et al., 2008).

In the definitive wave, true HSCs arise from the hemogenic endothelium localized in the ventral wall of the dorsal aorta (DA) of the aorta/gonad/mesonephros region (AGM) in a process termed the “endothelial-to-hematopoietic transition” (EHT) (Bertrand et al., 2010; Kissa and Herbomel, 2010; Lam et al., 2010). While HSCs involved in the EHT arise from the DA, they do not begin to further differentiate until they enter into circulation and seed the CHT, where they will differentiate into erythroid and myeloid lineages (Chen et al., 1995; Ciau-Uitz et al., 2014; Jin et al., 2009; Medvinsky et al., 2011; Murayama et al., 2006). Finally, HSCs from the CHT will migrate and seed the kidney marrow, the adult hematopoietic organ (Jin et al., 2007; Kissa et al., 2008).

Both bvra and bvrb, as well as hmox1a, display spatial and temporal expression patterns consistent with the developmental progression of differentiating HSCs. All three genes displayed strong expression within the ICM and were later detected within circulating primitive erythrocytes (Figures 1 and 2), consistent with the expression patterns of gata-1 (Galloway et al., 2005; Lam et al., 2009). However, bvra in situ expression was not detected between 48–120 hpf. In contrast, bvrb transcripts were detected within circulating erythrocytes at 48 hpf, as well as within the CHT, heart, liver, and kidney at 96 and 120 hpf (Figure 1B). These fluctuations in bvra and bvrb expression within the ICM and the CHT are consistent with known expression patterns of zebrafish embryonic globin genes (Brownlie et al., 2003; Ganis et al., 2012). During vertebrate development a process known as globin switching occurs in which there is a change in production from embryonic to adult globins. This is thought to allow for tolerance towards fluctuating oxygen levels as embryonic globin genes produce hemoglobin molecules that have a higher oxygen binding affinity in comparison to their adult counterparts (Iuchi, 1973). Around 24 hpf, developing zebrafish express a specific set of embryonic globins within the ICM (Brownlie et al., 2003), the same location in which bvra and bvrb show overlapping expression patterns (Figure 1A). However, by 72 hpf most embryonic globin genes cannot be detected via in situ hybridization (Brownlie et al., 2003), as was observed for bvra and bvrb (Figure 1B). Embryonic globin expression reinitiates between 72–120 hpf as the definitive wave of hematopoeisis progresses (Ganis et al., 2012). Likewise, bvrb expression becomes strong within the CHT during this same time period (Figure 1B).

Although both BVR enzymes contain a reductase domain, it is important to note that BVRa has several functional domains not found in BVRb, such as a serine/threonine/tyrosine kinase (S/T/Y) domain (Kutty and Maines, 1981; Lerner-Marmarosh et al., 2005; Salim et al., 2001), a leucine zipper DNA-binding domain (Ahmad et al., 2002) and adenine-binding motifs (Komuro et al., 1996), as well as nuclear export and localization signals (Lerner-Marmarosh et al., 2008; Maines et al., 2001). Thus, the overlapping expression of both bvra and bvrb during early zebrafish development raises an interesting question; namely, is there a physiological reason necessitating the need for two biliverdin reducing enzymes within hematopoietic tissues during early zebrafish development, or does one or more of these enzymes function in a role not related to biliverdin reduction? During this time period in zebrafish development there is a transition from anoxia tolerance (<24 hpf) to declining survivability due to anoxia sensitivity (~24–48 hpf), with anoxia becoming lethal at approximately 52 hpf (Padilla and Roth, 2001). One explanation for this transition in anoxia sensitivity is the occurrence of a highly coordinated change in metabolism from an anaerobic to an aerobic form of energy production that is more conducive to generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Mendelsohn and Gitlin, 2008; Mendelsohn et al., 2008). Furthermore, while GSH recycling typically represents the frontline defense against oxidative stress, oscillating levels of GSH and fluctuations in cytosolic redox environment have been reported between 0–48 hpf in developing zebrafish embryos (Timme-Laragy et al., 2013). Specifically, the cytoplasmic redox environment during early development is highly oxidized (~ 3–24 hpf) but starts transitioning to a reduced environment by ~48 hpf. Thus, it is not until ~72 hpf that embryos have a favorable redox environment conducive to conferring protection against oxidative stress, i.e., the maintenance of high levels of reduced GSH. The expression profiles of the NADPH-generating enzymes (Figure 8) provide a potential explanation for the alteration of the cytoplasmic redox environment during zebrafish development. The significant increase in expression of these NADPH-generating enzymes at 72 hpf corresponds to the developmental timepoint at which zebrafish embryos can maintain a stable redox environment that allows for the continued maintenance of a large ratio of reduced GSH to oxidized GSH (GSSG) (Timme-Laragy et al., 2013). Interestingly, a previous zebrafsih study has demonstrated a reduction of red blood cell staining and an increase in oxidative stress in 72 hpf G6pd morphants exposed to the pro-oxidant 1-naphthol (Patrinostro et al., 2013), highlighting the important role of NADPH maintenance in protection against oxidative stress. Furthermore, the cellular redox environment of early embryos and the expression profiles of many of the NADPH-producing enzymes raise some interesting questions regarding tissue-specific production levels of NADPH during early zebrafish development.

A highly oxidized redox environment during earlier development (< 48 hpf) would favor the formation of methemoglobin, an oxidized form of hemoglobin with a reduced ability to release oxygen to tissues. Although the spatial expression of bvrb is consistent with the location of HSCs during both primitive and definitive erythropoiesis, bvrb is only strongly detectable in circulating RBCs during earlier developmental timepoints that experience a more oxidized cellular environment (Figure 1). Therefore, high expression levels of bvrb, also known as methemoglobin reductase (Xu et al., 1992), may represent a cellular need to maintain reduced hemoglobin levels during this time period. Conversely, in the absence of reduced GSH during early zebrafish development, Bvra may be functioning to provide protection against oxidative stress via an anti-oxidant pathway by recycling bilirubin. Furthermore, since BVRa has been shown to have dual cofactor (NADH and NADPH) dual pH specificity (Kutty and Maines, 1981), co-factor selectivity between the two BVR enzymes and potential limitations in NADPH levels during these early developmental timeperiods warrants further investigation. Finally, BVRa has also been shown to activate HMOX1 transcription by transporting cytoplasmic heme into the nucleus (Tudor et al., 2008). Thus, despite their overlapping expression patterns, the potential for these two Bvr genes to play very different roles during early zebrafish development is of significant interest and warrants further attention in future studies.

HMOX1 has been demonstrated to be extremely important for embryonic survival as the majority of Hmox1−/− mice die in utero (Poss and Tonegawa, 1997). Hmox1 has been shown to be expressed in macrophages in rat fetal liver (Watanabe et al., 2004), the yolk syncytial layer and blood cells of zebrafish (Thisse et al., 2004), and developing mouse erythroid cells (Garcia-Santos et al., 2014). Furthermore, Hmox1−/− mice have an increased number of circulating RBCs with an abnormally long lifespan due to decreases in macrophages which are usually responsible for the removal of aged erythrocytes (Fraser et al., 2015). Collectively, Hmox1 expression in differentiating erythroid cells (Garcia-Santos et al., 2014) and the increased lifespan of RBCs in Hmox1−/− mice (Fraser et al., 2015) suggests a role for HMOX1 in maintaining RBC turnover, a putative function that may also be conserved in zebrafish.

4.2 Differential regulation of hmox1a, bvra and bvrb expression by Gata-1 and Nrf2

In agreement with published reports, Gata-1 knockdown resulted in a loss of bvrb expression within the ICM (Figure 6A) (Galloway et al., 2005). Although GATA-1 null mice and GATA-1 deficient cell lines show numerous genes with only reduced transcript levels (Pevny et al., 1995; Weiss and Orkin, 1995) the continued expression of bvra within the PBI in Gata-1 morphants at 24 hpf (Figure 6A) could suggest regulation by transcription factors other than Gata-1, such as Pu.1 or Gata-2. Pu.1 serves as the main transcriptional regulator of myeloid and lymphoid lineages (Hromas et al., 1993; Klemsz et al., 1990; Scott et al., 1994) and has been shown to physically interact with Gata-1. It is through this interaction that Pu.1 and Gata-1 antagonize each other (Cantor and Orkin, 2002), with loss of Gata-1 expression resulting in an increase in pu.1 expression and subsequent coercion of ICM progenitors towards a myeloid lineage (Galloway et al., 2005; Lyons et al., 2002; Rhodes et al., 2005). Interestingly, Gata-2 has been shown to be able to regulate some erythroid genes in Gata-1 mutant mice during embryonic hematopoiesis (Takahashi et al., 2000); thus, bvra may potentially be co-regulated by Gata-1 and -2. Although all three genes contained GATA and PU.1 binding motifs, the promoter region of bvra is enriched in the AGATAA motif that has a high affinity for all three GATA factors (Ko and Engel, 1993) (Figure 7). Interestingly, the proximal promoter region (within 500 bp of the transcription start site) of the bvra gene contain both the AGATAA motif, as well as a PU.1 binding motif (Figure 7). Future functional studies are needed to confirm whether Pu.1 or Gata-2 are capable of regulating bvra expression patterns during primitive hematopoiesis.

Further investigation of this potential relationship between Gata-1 and bvra or bvrb expression at 96 hpf provides additional evidence that Gata-1 may be regulating one or both bvr isoforms (Figure 6B). In contrast to the loss of bvra and bvrb expression in Gata-1 morphants at 24 hpf, both bvr isoforms appeared to be expressed at greater levels in Gata-1 morphants at 96 hpf (Figure 6B). One potential explanation for this observation would be that as the effects of Gata-1 knockdown diminish, the hematopoietic program reinitiates resulting in the increased expression of genes involved in hematopoiesis. Alternatively, while it is known that Gata-1 and Pu.1 can antagonize one another, it has been demonstrated that their feedback loops and interactions are modulated by Tif1γ and are dependent on their spatial and temporal contexts (Monteiro et al., 2011). In this regard, the model proposed by Monteiro et al. (2011) states that Gata-1 positively regulates itself within the ICM during primitive hematopoiesis but negatively regulates itself within the CHT during definitive hematopoiesis (Monteiro et al., 2011). Thus, the unexpected increase in bvra and bvrb expression at 96 hpf in Gata-1 morphants is consistent with the increase in Gata-1 within the CHT reported in Gata-1 morphants (Monteiro et al., 2011) and may be the result of an increase in Gata-1 levels resulting from disruption of the normal auto-inhibitory role of Gata-1 within the CHT (Figure 6B). Therefore, future studies should address if Tif-1λ may be involved in the transcriptional regulation of bvra and bvrb and if the expression of these genes is relegated to a specific time period during hematopoiesis.

In contrast to the changes in bvra and bvrb expression, Gata-1 knockdown did not appear to attenuate hmox1a:mCherry fluorescence (Figure 6C). However, Nrf2 is a known HMOX1 regulator (Alam et al., 1999) and NRF2 has recently been shown to play a role in HSC homoeostasis (Merchant et al., 2011; Tsai et al., 2013). Specifically, loss of NRF2 has been demonstrated to result in hematopoietic expansion of HSC and progenitor cell compartments, suggesting that NRF2 acts as a negative regulator of HSC entry into the cell cycle (Tsai et al., 2013). The two paralogs of Nrf2 in zebrafish resulting from the teleost-specific genome duplication event have undergone subfunction partitioning, with Nrf2a thought to act primarily as a transcriptional activator and Nrf2b acting as a transcriptional repressor (Timme-Laragy et al., 2012). Since Nrf2a has been demonstrated to positively regulate hmox1a (Fuse et al., 2015; Nakajima et al., 2011; So et al., 2014) and bvrb in response to Cd exposure (Holowiecki et al., 2016), we sought to determine its putative role in regulating hmox1a, bvra and bvrb during the early stages hematopoiesis. There was no substantial decrease in bvra or bvrb expression within primitive erythrocytes or hematopoietic tissues in Nrf2a morphants (Figures 3 and 5). However, although Cd exposure did not appear to alter the spatial expression of bvrb in 96 hpf zebrafish, the increased in situ staining intensity was diminished to levels more consistent with non-exposed zebrafish (Figure 5). As expected Nrf2a knockdown resulted in a significant decrease in hmox1a expression in Cd-treated eleutheroembryos at 96 hpf (Figure 5), confirming the effectiveness of the Nrf2a MO. So, despite a putative role in regulating bvrb expression in response to oxidative stress, Nrf2a does not appear to be playing a significant role in regulating basal bvr expression during zebrafish development.

In our previous study, we demonstrated that hmox1a was expressed at a significantly higher level throughout zebrafish development compared to hmox1b, with a significant spike in hmox1a expression at 24 hpf (Holowiecki et al., 2016). Interestingly, the Nrf2a knockdown did not fully attenuate our ability to detect hmox1a:mCherry expression in hematopoietic tissues at 24 hpf (Figure 4). However, real-time RT-PCR data did provide more quantitative data in support of a role for Nrf2a in regulating basal hmox1a expression, which is contrasted by the minimal effect of the Nrf2a knockdown on hmox1b (Figure 4). It should be noted that hmox1a and foxred2 genes appear to share a promoter region, and a significant portion of the hmox1a promoter in the mCherry in vivo construct includes a partial 5′ region of the exon/intron sequence of the foxred2 gene that is in the opposite orientation of the hmox1a gene (Figure 7). Thus, some of the observed mCherry fluorescence could be partially related to foxred2 regulation. However, the spatial expression of hmox1a during hematopoiesis is supported by several previous studies (Craven et al., 2005; Thisse et al., 2004; Garcia-Santos et al., 2014). Furthermore, the proximal promoter region of the hmox1a gene contains both a GATA and a PU.1 binding motif (Figure 7), which could potentially play a role in co-regulating hmox1a during hematopoiesis. Since Nrf2a appears to be playing a role in the positive basal regulation of hmox1a during primitive erythropoiesis, the minimal expression of hmox1b and lack of any significant change in hmox1b expression in Nrf2a morphants at 24 hpf raises some interesting questions regarding the potential role for Nrf2b in the inhibition of hmox1b during this early timepoint. The Nrf2a morphant results presented here provide further support for the proposed subfunction partitioning of the zebrafish hmox1 paralogs (Holowiecki et al., 2016). Furthermore, these data suggest that Nrf2a has a conserved role in hematopoiesis in zebrafish.

5. Conclusions

We have presented a thorough characterization of hmox1a, bvra and bvrb expression during zebrafish development and presented distinct spatial and temporal expression patterns Gata-1 and Nrf2a play differential roles in regulating the heme degradation enzymes during hematopoiesis. Furthermore, the research presented here highlights some important goals for future research, including the functional characterization of the roles of Bvra and Bvrb during zebrafish hematopoiesis, as well as the potential for subfunction partitioning of the Hmox1 paralogs in hematopoiesis. Finally, we provide evidence suggesting that one factor contributing to the developmental changes in sensitivity towards oxidative stress in zebrafish may be related to the availability of cytosolic and mitochondrial NADPH which is used for detoxification and reducing reactions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Pathway to Independence grant [R00ES017044] awarded to M.J. Jenny. This work was also partially supported by a Grant-in-Aid of Research from Sigma Xi, The Scientific Research Society, awarded to A. Holowiecki. The authors would like to thank Dr. Leonard I. Zon (Harvard Medical School) for providing the GATA-1 MO. The U.S. Government is authorized to produce and distribute reprints for governmental purposes notwithstanding any copyright notation that may appear hereon. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abraham NG, Kappas A. Pharmacological and clinical aspects of heme oxygenase. Pharmacol Rev. 2008;60:79–127. doi: 10.1124/pr.107.07104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agledal L, Niere M, Ziegler M. The phosphate makes a difference: cellular functions of NADP. Redox Rep. 2010;15:2–10. doi: 10.1179/174329210X12650506623122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad Z, Salim M, Maines MD. Human biliverdin reductase is a leucine zipper-like DNA-binding protein and functions in transcriptional activation of heme oxygenase-1 by oxidative stress. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:9226–9232. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108239200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam J, Stewart D, Touchard C, Boinapally S, Choi AMK, Cook JL. Nrf2, a Cap ‘ n ‘ Collar Transcription Factor, Regulates Induction of the Heme Oxygenase-1 Gene. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:26071–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.37.26071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amigo JD, Ackermann GE, Cope JJ, Yu M, Cooney JD, Ma D, Langer NB, Shafizadeh E, Shaw GC, Horsely W, Trede NS, Davidson AJ, Barut BA, Zhou Y, Wojiski SA, Traver D, Moran TB, Kourkoulis G, Hsu K, Kanki JP, Shah DI, Lin HF, Handin RI, Cantor AB, Paw BH. The role and regulation of friend of GATA-1 (FOG-1) during blood development in the zebrafish. Blood. 2009;114:4654–4663. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-189910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barañano DE, Rao M, Ferris CD, Snyder SH. Biliverdin reductase: a major physiologic cytoprotectant. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16093–16098. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252626999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barañano DE, Snyder SH. Neural roles for heme oxygenase: contrasts to nitric oxide synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:10996–11002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191351298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellner L, Wolstein J, Patil KA, Dunn MW, Laniado-Schwartzman M. Biliverdin rescues the HO-2 null mouse phenotype of unresolved chronic inflammation following corneal epithelial injury. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:3246–3253. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett CM, Kanki JP, Rhodes J, Liu TX, Paw BH, Kieran MW, Langenau DM, Delahaye-Brown A, Zon LI, Fleming MD, Thomas Look A. Myelopoiesis in the zebrafish, Danio rerio. Blood. 2001;98:643–651. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.3.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand JY, Cisson JL, Stachura DL, Traver D. Notch signaling distinguishes 2 waves of definitive hematopoiesis in the zebrafish embryo. Blood. 2010;115:2777–2783. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-244590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand JY, Kim AD, Teng S, Traver D. CD41+ cmyb+ precursors colonize the zebrafish pronephros by a novel migration route to initiate adult hematopoiesis. Development. 2008;135:1853–1862. doi: 10.1242/dev.015297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand JY, Kim AD, Violette EP, Stachura DL, Cisson JL, Traver D. Definitive hematopoiesis initiates through a committed erythromyeloid progenitor in the zebrafish embryo. Development. 2007;134:4147–4156. doi: 10.1242/dev.012385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouard S, Otterbein LE, Anrather J, Tobiasch E, Bach FH, Choi AM, Soares MP. Carbon monoxide generated by heme oxygenase 1 suppresses endothelial cell apoptosis. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1015–1026. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.7.1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownlie A, Hersey C, Oates AC, Paw BH, Falick AM, Witkowska HE, Flint J, Higgs D, Jessen J, Bahary N, Zhu H, Lin S, Zon L. Characterization of embryonic globin genes of the zebrafish. Dev Biol. 2003;255:48–61. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(02)00041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor AB, Orkin SH. Transcriptional regulation of erythropoiesis: an affair involving multiple partners. Oncogene. 2002;21:3368–3376. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XD, Turpen JB, Cantor AB, Orkin SH, Hahn ME, Timme-Laragy AR, Karchner SI, Stegeman JJ, Hromas R, Orazi A, Neiman RS, Maki RA, Van Beveran C, Moore J, Klemsz MJ, McKercher SR, Celada A, Van Beveren C, Maki RA, Kutty RK, Maines MD, Ewing JF, Huang TJ, Panahian N, Mendelsohn BA, Gitlin JD, Kassebaum BL, Gitlin JD, Padilla PA, Roth MB, Rhodes J, Hagen A, Hsu K, Deng M, Liu TX, Look AT, Kanki JP, Scott EW, Simon MC, Anastasi J, Singh H, So JH, Kim JD, Yoo KW, Kim HT, Jung SH, Choi JH, Lee MS, Jin SW, Kim CH, Takahashi S, Shimizu R, Suwabe N, Kuroha T, Yoh K, Ohta J, Nishimura S, Lim KC, Engel JD, Yamamoto M, Timme-Laragy AR, Goldstone JV, Imhoff BR, Stegeman JJ, Hahn ME, Hansen JM, Weiss MJ, Orkin SH. The zebrafish embryo as a dynamic model of anoxia tolerance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;237:1573–1577. [Google Scholar]

- Chitramuthu BP, Bennett HPJ. High resolution whole mount in situ hybridization within zebrafish embryos to study gene expression and function. J Vis Exp. 2013:e50644. doi: 10.3791/50644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciau-Uitz A, Monteiro R, Kirmizitas A, Patient R. Developmental hematopoiesis: ontogeny, genetic programming and conservation. Exp Hematol. 2014;42:669–683. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craven SE, French D, Ye W, de Sauvage F, Rosenthal A. Loss of Hspa9b in zebrafish recapitulates the ineffective hematopoiesis of the myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood. 2005;105:3528–3534. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson AJ, Ernst P, Wang Y, Dekens MP, Kingsley PD, Palis J, Korsmeyer SJ, Daley GQ, Zon LI. cdx4 mutants fail to specify blood progenitors and can be rescued by multiple hox genes. Nature. 2003;425:300–306. doi: 10.1038/nature01973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detrich HW, Kierant MW, Chant FYEE, Baronett LM, Yeet K, Rundstadlert JONA, Prat S, Ransomtt D, Zont LI. Intraembryonic hematopoietic cell migration during vertebrate development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:10713–10717. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooley KA, Fraenkel PG, Langer NB, Schmid B, Davidson AJ, Weber G, Chiang K, Foott H, Dwyer C, Wingert RA, Zhou Y, Paw BH, Zon LI, Bebber van F, Busch-Nentwich E, Dahm R, Frohnhöfer HG, Geiger H, Gilmour D, Holley S, Hooge J, Jülich D, Knaut H, Maderspacher F, Neumann C, Nicolson T, Nüsslein-Volhard C, Roehl H, Schönberger U, Seiler C, Söllner C, Sonawane M, Wehner A, Weiler C, Schmid B, Hagner U, Hennen E, Kaps C, Kirchner A, Koblizek TI, Langheinrich U, Metzger C, Nordin R, Pezzuti M, Schlombs K, deSantana-Stamm J, Trowe T, Vacun G, Walker A, Weiler C. Montalcino, A zebrafish model for variegate porphyria. Exp Hematol. 2008;36:1132–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doré S, Takahashi M, Ferris CD, Zakhary R, Hester LD, Guastella D, Snyder SH. Bilirubin, formed by activation of heme oxygenase-2, protects neurons against oxidative stress injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:2445–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser ST, Midwinter RG, Coupland LA, Kong S, Berger BS, Yeo JH, Andrade OC, Cromer D, Suarna C, Lam M, Maghzal GJ, Chong BH, Parish CR, Stocker R. Heme oxygenase-1 deficiency alters erythroblastic island formation, steady-state erythropoiesis and red blood cell lifespan in mice. Haematologica. 2015;100:601–610. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2014.116368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuse Y, Nakajima H, Nakajima-Takagi Y, Nakajima O, Kobayashi M. Heme-mediated inhibition of Bach1 regulates the liver specificity and transience of the Nrf2-dependent induction of zebrafish heme oxygenase 1. Genes to Cells. 2015:590–600. doi: 10.1111/gtc.12249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galloway JL, Wingert RA, Thisse C, Thisse B, Zon LI. Loss of Gata1 but not Gata2 converts erythropoiesis to myelopoiesis in zebrafish embryos. Dev Cell. 2005;8:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganis JJ, Hsia N, Trompouki E, de Jong JLO, DiBiase A, Lambert JS, Jia Z, Sabo PJ, Weaver M, Sandstrom R, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, Zhou Y, Zon LI. Zebrafish globin switching occurs in two developmental stages and is controlled by the LCR. Dev Biol. 2012;366:185–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Santos D, Schranzhofer M, Horvathova M, Jaberi MM, Bogo Chies JA, Sheftel AD, Ponka P. Heme oxygenase 1 is expressed in murine erythroid cells where it controls the level of regulatory heme. Blood. 2014;123:2269–2277. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-496760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs PEM, Tudor C, Maines MD. Biliverdin reductase: More than a namesake-the reductase, its peptide fragments, and biliverdin regulate activity of the three classes of protein kinase C. Front Pharmacol. 2012;3:1–10. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2012.00031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorrini C, Harris IS, Mal TW. Modulaton of oxidative stress as an anticancer strategy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12:931–947. doi: 10.1038/nrd4002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holowiecki A, O’Shields B, Jenny MJ. Characterization of heme oxygenase and biiverdin reductase gene expression in zebrafish (Danio rerio): basal expression and response to pro-oxidant exposures. Tox Appl Pharmacol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2016.09.022. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.taap.2016.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hromas R, Orazi A, Neiman RS, Maki R, Van Beveran C, Moore J, Klemsz M. Hematopoietic lineage- and stage-restricted expression of the ETS oncogene family member PU. 1. Blood. 1993;82:2998–3004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iuchi I. Chemical and physiological properties of the larval and the adult hemoglobins in rainbow trout, Salmo gairdnerii irideus. Comp Biochem Physiol B. 1973;44:1087–1101. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(73)90262-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings GT, Stevenson PM. A study of the control of NADP(+) -dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase activity during gonadotropin-induced development of the rat ovary. Eur J Biochem. 1991;625:621–625. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H, Sood R, Xu J, Zhen F, English MA, Liu PP, Wen Z. Definitive hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells manifest distinct differentiation output in the zebrafish VDA and PBI. Development. 2009;136:647–654. doi: 10.1242/dev.029637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H, Xu J, Wen Z. Migratory path of definitive hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells during zebrafish development. Blood. 2007;109:5208–5214. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-069005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo SH, Son MK, Koh HJ, Lee SM, Song IH, Kim YO, Lee YS, Jeong KS, Kim WB, Park JW, Song BJ, Huhe TL. Control of Mitochondrial Redox Balance and Cellular Defense against Oxidative Damage by Mitochondrial NADP+-dependent Isocitrate Dehydrogenase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:16168–16176. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010120200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami K. Tol2: a versatile gene transfer vector in vertebrates. Genome Biol. 2007;8(Suppl 1):S7. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-s1-s7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami K, Shima A, Kawakami N. Identification of a functional transposase of the Tol2 element, an Ac-like element from the Japanese medaka fish, and its transposition in the zebrafish germ lineage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:11403–11408. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.21.11403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch M, De Groot H. NAD(P)H, a directly operating antioxidant? FASEB J. 2001;15:1569–1574. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0823hyp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissa K, Herbomel P. Blood stem cells emerge from aortic endothelium by a novel type of cell transition. Nature. 2010;464:112–115. doi: 10.1038/nature08761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissa K, Murayama E, Zapata A, Cortes A, Perret E, Machu C, Herbomel P. Live imaging of emerging hematopoietic stem cells and early thymus colonization. Blood. 2008;111:1147–1156. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-099499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klemsz MJ, McKercher SR, Celada A, Van Beveren C, Maki RA. The macrophage and B cell-specific transcription factor PU. 1 is related to the ets oncogene. Cell. 1990;61:113–124. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90219-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko LJ, Engel JD. DNA-binding specificities of the GATA transcription factor family. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:4011–4022. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.7.4011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi M, Itoh K, Suzuki T, Osanai H, Nishikawa K, Katoh Y, Takagi Y, Yamamoto M. Identification of the interactive interface and phylogenic conservation of the Nrf2-Keap1 system. Genes Cells. 2002;7:807–820. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2002.00561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komuro A, Tobe T, Nakano Y, Yamaguchi T, Tomita M. Cloning and characterization of the cDNA encoding human biliverdin-IX alpha reductase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1309:89–99. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(96)00099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutty RK, Maines MD. Purification and characterization of biliverdin reductase from rat liver. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:3956–3962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan KM, Fujimoto E, Grabher C, Mangum BD, Hardy ME, Campbell DS, Parant JM, Yost HJ, Kanki JP, Chien CB. The Tol2kit: a multisite gateway-based construction kit for Tol2 transposon transgenesis constructs. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:3088–3099. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam EYN, Chau JYM, Kalev-Zylinska ML, Fountaine TM, Mead RS, Hall CJ, Crosier PS, Crosier KE, Flores MV. Zebrafish runx1 promoter-EGFP transgenics mark discrete sites of definitive blood progenitors. Blood. 2009;113:1241–1249. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-149898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam EYN, Hall CJ, Crosier PS, Crosier KE, Flores MV. Live imaging of Runx1 expression in the dorsal aorta tracks the emergence of blood progenitors from endothelial cells. Blood. 2010;116:909–914. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-264382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner-Marmarosh N, Miralem T, Gibbs PEM, Maines MD. Human biliverdin reductase is an ERK activator; hBVR is an ERK nuclear transporter and is required for MAPK signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:6870–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800750105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner-Marmarosh N, Shen J, Torno MD, Kravets A, Hu Z, Maines MD. Human biliverdin reductase: a member of the insulin receptor substrate family with serine/threonine/tyrosine kinase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:7109–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502173102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons SE, Lawson ND, Lei L, Bennett PE, Weinstein BM, Liu PP. A nonsense mutation in zebrafish gata1 causes the bloodless phenotype in vlad tepes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:5454–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082695299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maines MD, Ewing JF, Huang TJ, Panahian N. Nuclear localization of biliverdin reductase in the rat kidney: response to nephrotoxins that induce heme oxygenase-1. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;296:1091–1097. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medvinsky A, Rybtsov S, Taoudi S. Embryonic origin of the adult hematopoietic system: advances and questions. Development. 2011;138:1017–1031. doi: 10.1242/dev.040998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelsohn BA, Gitlin JD. Coordination of development and metabolism in the pre-midblastula transition zebrafish embryo. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:1789–1798. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelsohn BA, Kassebaum BL, Gitlin JD. The zebrafish embryo as a dynamic model of anoxia tolerance. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:1780–1788. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merchant AA, Singh A, Matsui W, Biswal S. The redox-sensitive transcription factor Nrf2 regulates murine hematopoietic stem cell survival independently of ROS levels. Blood. 2011;118:6572–6579. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-05-355362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro R, Pouget C, Patient R. The gata1/pu. 1 lineage fate paradigm varies between blood populations and is modulated by tif1gamma. EMBO J. 2011;30:1093–1103. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon MS, McDevitt EI, Zhu J, Stanley B, Krzeminski J, Amin S, Aliaga C, Miller TG, Isom HC. Elevated hepatic iron activates NF-E2-related factor 2-regulated pathway in a dietary iron overload mouse model. Toxicol Sci. 2012;129:74–85. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfs193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murayama E, Kissa K, Zapata A, Mordelet E, Briolat V, Lin HF, Handin RI, Herbomel P. Tracing hematopoietic precursor migration to successive hematopoietic organs during zebrafish development. Immunity. 2006;25:963–975. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima H, Nakajima-Takagi Y, Tsujita T, Akiyama SI, Wakasa T, Mukaigasa K, Kaneko H, Tamaru Y, Yamamoto M, Kobayashi M. Tissue-restricted expression of Nrf2 and its target genes in zebrafish with gene-specific variations in the induction profiles. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26884. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otterbein LE, Bach FH, Alam J, Soares M, Tao Lu H, Wysk M, Davis RJ, Flavell RA, Choi AM. Carbon monoxide has anti-inflammatory effects involving the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Nat Med. 2000;6:422–428. doi: 10.1038/74680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla PA, Roth MB. Oxygen deprivation causes suspended animation in the zebrafish embryo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:7331–7335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.131213198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]