Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Hippocampal volume, cortical metabolism and thickness are decreased in mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Hippocampal metabolism studies comparing MCI and clinically normal (CN) elderly gave inconsistent results. As hippocampus is a key region in Alzheimer’s disease, we hypothesized that hippocampal metabolism is specifically decreased in high-amyloid MCI.

METHODS

250CN and 45MCI underwent 3D-MRI, FDG-PET, and PIB-PET. We investigated the interaction between clinical and amyloid status on hippocampal metabolism, hippocampal volume, cortical metabolism and thickness using linear models, covarying age, gender, and education. Analyses were conducted with and without correction for multiple comparisons and for partial volume effects.

RESULTS

Volume-adjusted hippocampal metabolism was decreased in high-amyloid MCI but close to normal in low-amyloid MCI and in high-amyloid CN. Both MCI groups had hippocampal atrophy, although less severe in low-amyloid MCI. High-amyloid CN and high-amyloid MCI had cortical hypometabolism.

DISCUSSION

Hippocampal metabolism is decreased when both cognitive impairment and amyloid are present.

Keywords: Hippocampus, association cortex, metabolism, FDG-PET, amyloid, mild cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease

BACKGROUND

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder defined pathologically by the presence of amyloid-beta (Aβ) plaques and tau neurofibrillary tangles [1, 2]. Over the past decade, PET imaging biomarkers have been developed that detect Aβ during life; and amyloid PET now supports a diagnosis of cognitive impairment specifically due to AD [3]. Elevated Aβ is commonly but not invariably detected with PET among mildly cognitively impaired (MCI), non-demented elderly, and when present, it confirms a diagnosis of prodromal MCI due to AD [4, 5]. Aβ is frequently detected with PET among clinically normal (CN) elderly individuals, in whom it confers increased risk of future cognitive decline [6, 7]. A second class of imaging biomarkers, which have evolved over many years, primarily detects later stage pathophysiologic changes that putatively result from the defining pathologies of AD. These include image measures of brain regions vulnerable to damage in AD, hippocampal volume (HV), thickness of the association cortex (ACT), and metabolism in the association cortex (ACM). These biomarkers, while much less specific for underlying pathology, have been useful to assess disease progression because they correlate with concurrent changes in cognitive and functional measures of clinical decline along the AD trajectory [8, 9]. Here we evaluated hippocampal metabolism (HM), after adjusting for hippocampal volume loss, to determine whether it was associated with both specificity of underlying molecular pathology, i.e., high levels of Aβ, and the cognitive phenotype that signified progression along the AD trajectory, i.e., MCI. We found that HM was decreased in MCI individuals with high Aβ, but not in low Aβ MCI or in CN.

METHODS

1. Participants: see Table 1

TABLE 1.

Demographic, cognitive and amyloid data for clinically normal (CN) older adults and patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), categorized by amyloid status (Aβ)

| Mean +/− standard deviation | Low-Aβ CN | High-Aβ CN | Low-Aβ MCI | High-Aβ MCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | 188 | 62 | 24 | 21 |

| Age (years) | 73.2 +/− 5.9 | 75.4 +/− 6.2* | 71.8 +/− 7.5 | 73.3 +/− 8.4 |

| Gender (% of male) | 39.3% | 41.9% | 62.5%* | 61.9%* |

| Education (years) | 15.8 +/− 3.0 | 16.2 +/− 2.8 | 15.8 +/− 3.3 | 16.9 +/− 2.4 |

| Clinical Dementia Rating | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Mini-Mental State Exam | 29.1 +/− 1.0 | 28.8 +/− 1.0 | 27.8 +/− 1.4** | 27.0 +/− 2.0** |

| Logical Memory delayed recall | 14.4 +/− 3.4 | 14.0 +/− 3.0 | 7.4 +/− 3.3** | 6.3 +/− 5.2** |

| Aβ (neocortical PIB DVR) | 1.08 +/− 0.05 | 1.42 +/− 0.15** | 1.08 +/− 0.06 | 1.60 +/− 0.17** |

Significantly different from low-Aβ CN (p<.050)

(p<.001)

Two hundred ninety-five non-demented participants from the Harvard Aging Brain Study and other ongoing studies on aging and AD were analyzed in the present report. We utilized criteria from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI2) to classify participants either as clinically normal (CN) older adults or as patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment (MCI), single- or multiple-domain. The Logical Memory (LM) IIa of the Wechsler Memory Scale–Revised (delayed recall) was used to assess objective memory, using an education adjusted cut-off, as described previously [6]. MCI patients and/or study partner reported a memory complaint, but had essentially intact activities of daily living, as assessed by the Functional Activities Questionnaire and Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR), and no evidence of dementia [10]. Criteria for MCI (n=45) included a global CDR score of 0.5, a Memory Box score ≥ 0.5 and an education-adjusted Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) ≥24. Criteria for CN (n=250) included a global CDR score of 0, an education-adjusted MMSE score ≥27 and an education-adjusted LM performance within the normal range (≥9 for ≥16y, ≥7 for 8–15y and ≥5 for <8y of education). All participants were medically stable and did not have confounding neurological or psychiatric conditions or substance or alcohol abuse within the past 2 years. All MCI patients had a Modified Hachinski Ischaemic Score ≤ 4 and a Geriatric Depression Scale (long form) ≤10. Written informed consent was obtained prior to experimental procedures and the study was approved, and conducted, in accordance with the Partners Human Research Committee at the Massachusetts General Hospital and Brigham and Women Hospital (Boston, MA).

2. Brain imaging procedures

Structural MRI, FDG-PET and PIB-PET images were acquired within one year for each subject. Median delay between imaging sessions was 39 days (min: 0 – max: 302).

MRI data were collected on a Siemens TrioTim 3 tesla scanner equipped with a 12-channel phased-array head coil. High-resolution T1-weighted anatomical images were acquired using an MPRAGE with the following parameters: repetition time =6400ms, echo time =2.8ms, inversion time =900ms, 8° flip angle, sagittal slides, voxel size=1.0×1.0×1.2mm. MRI data were analyzed in the native space using Freesurfer version 5.1 (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu), including estimation of HV and cortical thickness. Freesurfer output files (brainmask.mgz) were individually assessed and manual interventions included examination of the white and pial surface segmentation. In cases where dura or skull influenced the segmentation result, voxels were either manually edited or corrected by adjusting the watershed threshold. In cases where the grey matter ribbon clearly included white matter or clearly excluded grey matter; control points were added to the recon and/or white matter edits were made to the wm.mgz file. Autorecon2 and autorecon3 processing steps were re-run on the edited files. HV was collapsed across hemispheres and adjusted for total intracranial volume (ICV) using the following equation: Adjusted HV = Raw HV − b * (ICV − Mean ICV), where b indicates the regression coefficient when HV is regressed against ICV and mean ICV is the average ICV value of CN older adults.

FDG-PET data were acquired as described previously [11]. A bolus of 5 mCi of 18F-FDG was injected, in a quiet, dimly lit room, with subjects in the eyes-open state. FDG acquisition began 45 minutes (min) after injection and lasted 30 min. Each individual PET data set was rigidly co-registered to the subject’s MRI data. The cortical ribbon and subcortical Freesurfer ROIs defined by MRI as described above were transformed into the PET native space using SPM8. FDG was expressed as the standardized uptake value and normalized to the cerebellum gray matter for each ROI. A hippocampal ROI was compared to an association cortex ROI. Association cortex was defined as an aggregate of regions known to be affected in MCI [12]: bilateral precuneus, inferior parietal and inferior temporal cortices. We used two methods to take into account the impact of the underlying anatomy on FDG: First, the corresponding structural data (HV for HM and ACT for ACM) were used as covariates in the FDG analyzes. Second, we used a geometric transfer matrix method [13] to correct FDG data for partial volume effects (PVE), as shown in the supplementary graphs.

PIB was synthesized, and PIB-PET data were acquired as described previously [14]. A bolus of 10–15 mCi of 11C-PiB was injected and followed immediately by a 60-min dynamic acquisition, using a HR+ PET camera (3D mode; 63 image planes). PIB data were reconstructed with ordered set expectation maximization, corrected for attenuation. Each frame was evaluated to verify adequate count statistics and absence of head motion. Using Logan’s graphical analysis method [15], we calculated PIB retention expressed as the distribution volume ratio (DVR), using a gray matter cerebellum reference region. Aβ status was determined for each subject using a global DVR from a set of neocortical regions including frontal, lateral temporal, lateral parietal and retrospenial cortex (the FLR region). Participants were classified as either low- Aβ or high-Aβ, based on a threshold of 1.20, as described previously [6]. Four groups of interest were defined: low-Aβ CN (n=188), high-Aβ CN (n=62), low-Aβ MCI (n=24) and high-Aβ MCI (n=21).

3. Statistical analyses

For each variable of interest (HM, HV, ACM and ACT), we fit a linear model investigating the interaction between clinical and Aβ status, covarying age, gender, education, and structural data (HV for HM, ACT for ACM). We computed post-hoc tests (Table 2) to compare each pairwise group comparison, adjusting for multiple comparisons (family-wise error correction using Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference test). In order to avoid rejecting a difference that might be present, we also report uncorrected p-values from these models (Fischer’s Least Significant Difference test). We additionally analyzed the correlations between imaging and cognitive (MMSE) data and computed ROC curves to investigate sensitivity and specificity of each biomarker to detect (1) MCI among CN, and (2) elevated Aβ among MCI. Statistical analyses were conducted in Statistica version 13 (Statsoft, Dell). We report two-tailed p-values.

TABLE 2.

Post-hoc tests comparing clinically normal (CN) and mild cognitive impairment (MCI), categorized by amyloid status (Aβ) for four biomarkers: hippocampal metabolism (HM), hippocampal volume (HV), association cortex metabolism (ACM), and thickness (ACT)

| Biomarker | Group comparison | Estimate | Uncorrected p | Corrected p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HM | Low-Aβ CN - High-Aβ CN | −0.002 | 0.7161 | 0.9838 |

| HM | Low-Aβ CN - Low-Aβ MCI | −0.007 | 0.3608 | 0.7993 |

| HM | Low-Aβ CN - High-Aβ MCI | −0.058 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| HM | High-Aβ CN - Low-Aβ MCI | −0.005 | 0.5466 | 0.9320 |

| HM | High-Aβ CN - High-Aβ MCI | −0.056 | <0.0001 | 0.0003 |

| HM | Low-Aβ MCI - High-Aβ MCI | −0.051 | 0.0036 | 0.0180 |

| HV | Low-Aβ CN - High-Aβ CN | −84 | 0.0083 | 0.0375 |

| HV | Low-Aβ CN - Low-Aβ MCI | −248 | 0.0133 | 0.0577 |

| HV | Low-Aβ CN - High-Aβ MCI | −603 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| HV | High-Aβ CN - Low-Aβ MCI | −164 | 0.5887 | 0.9489 |

| HV | High-Aβ CN - High-Aβ MCI | −519 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| HV | Low-Aβ MCI - High-Aβ MCI | −355 | 0.0013 | 0.0063 |

| ACM | Low-Aβ CN - High-Aβ CN | −0.030 | 0.0021 | 0.0103 |

| ACM | Low-Aβ CN - Low-Aβ MCI | −0.007 | 0.4812 | 0.8950 |

| ACM | Low-Aβ CN - High-Aβ MCI | −0.103 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| ACM | High-Aβ CN - Low-Aβ MCI | 0.023 | 0.2105 | 0.5918 |

| ACM | High-Aβ CN - High-Aβ MCI | −0.073 | <0.0001 | 0.0009 |

| ACM | Low-Aβ MCI - High-Aβ MCI | −0.096 | <0.0001 | 0.0002 |

| ACT | Low-Aβ CN - High-Aβ CN | −0.028 | 0.0302 | 0.1293 |

| ACT | Low-Aβ CN - Low-Aβ MCI | −0.012 | 0.6783 | 0.9759 |

| ACT | Low-Aβ CN - High-Aβ MCI | −0.088 | 0.0004 | 0.0021 |

| ACT | High-Aβ CN - Low-Aβ MCI | 0.017 | 0.3417 | 0.7764 |

| ACT | High-Aβ CN - High-Aβ MCI | −0.060 | 0.0482 | 0.1938 |

| ACT | Low-Aβ MCI - High-Aβ MCI | −0.076 | 0.0152 | 0.0692 |

Color code: α=0.10 (blue) α=0.05 (orange) α=0.01 (red)

RESULTS

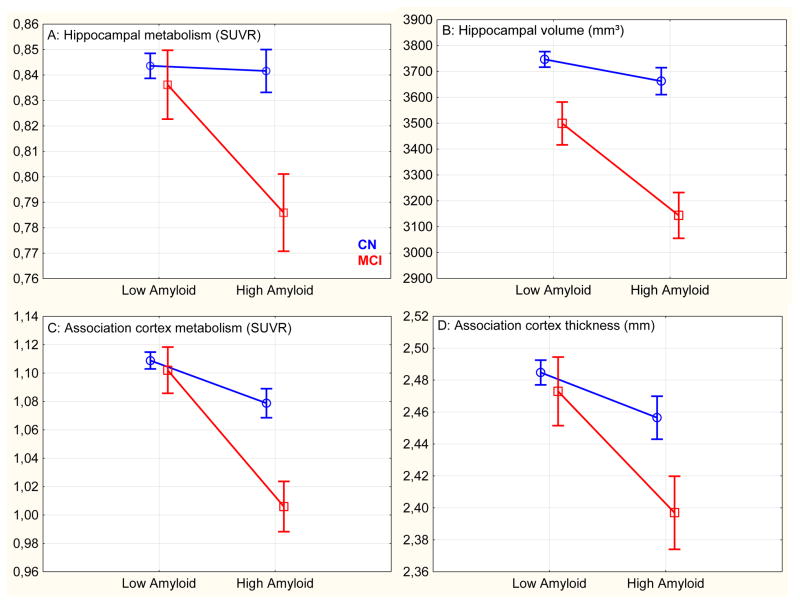

1. Hippocampal metabolism: (Graph 1.A, supplementary Graph S1 for PVE-corrected data)

Graph 1.

Imaging data in clinically normal (CN) and mild cognitive impairment (MCI), adjusted for covariates

The interaction between clinical diagnosis and Aβ was significant (unstandardized β-estimate =.16, p=.029). Age (β=.06, p=.322), gender (β=−.01, p=.811) and education (β=.01, p=.846) were not related to HM. Yet, HV was associated with HM (β=.15, p=.025). PVE-corrected data gave similar results although HM was negatively associated with HV (β=−.16, p=.013), possibly due to an over-correction. Post-hoc tests showed that high-Aβ MCI had significantly lower HM than any other group. Low-Aβ MCI and high-Aβ CN did not demonstrate reduction in HM, even using a liberal uncorrected threshold (see Table 2).

2. Hippocampal volume: (Graph 1.B)

The interaction between clinical diagnosis and Aβ was significant (β=.13, p=.045). Older ages (β=.37, p<.0001) were significantly associated with reduced HV while gender (β=.07, p=.180) and education (β=.04, p=.478) were not. Post-hoc tests showed that high-Aβ MCI had significantly lower HV than any other group but high-Aβ CN and low-Aβ MCI also had hippocampal atrophy, compared to low-Aβ CN.

3. Association cortex metabolism: (Graph 1.C, supplementary Graph S2 for PVE-corrected data)

The interaction between clinical diagnosis and Aβ was significant (β=.17, p=.013). Older ages (β=.15, p=.007) and male gender (β=.19, p=.0005) were significantly associated with lower ACM while education (β=.07, p=.195) and cortical thinning (β=.05, p=.373) were not. PVE-corrected data gave similar results although ACM was negatively associated with ACT (β=−.15, p=.006). Post-hoc tests showed that high-Aβ MCI had significantly lower ACM than any other group. High-Aβ CN also demonstrated reduced ACM compared to low-Aβ CN; however, ACM was not different in low-Aβ MCI and low-Aβ CN.

4. Association cortex thickness: (Graph 1.D)

The interaction between clinical diagnosis and Aβ failed to reach significance (β=.10, p=.171). Older ages (β=.17, p=.0004) were associated with lower ACT while gender (β=.03, p=.583) and education (β=.10, p=.076) were not. Post-hoc tests showed that high-Aβ MCI had significant cortical thinning compared to low-Aβ CN and, to a lower extent, compared to the other groups. High-Aβ CN had slight thinning, that did not survive after correction for multiple comparisons.

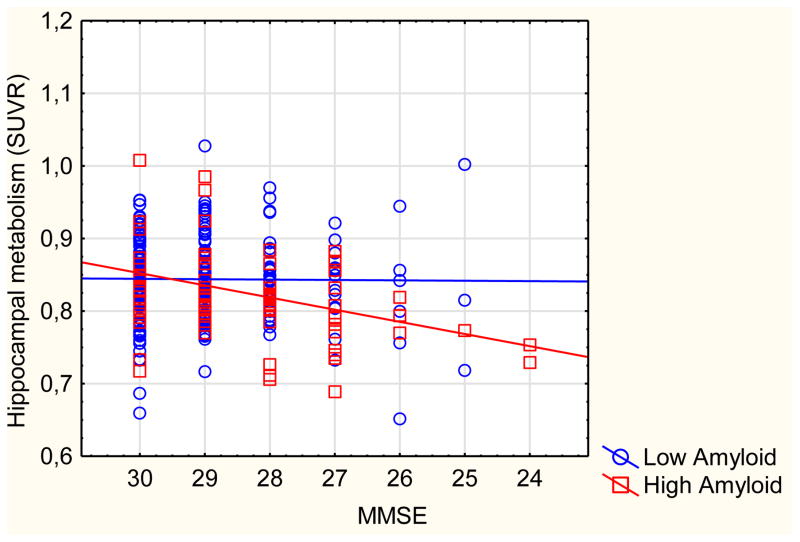

5. Correlations between cognition and imaging: (Graph 2) – adjusted for age, gender, education, and structural data for HM and ACM. CN and MCI are pooled for this analysis

Graph 2.

Scatterplot of hippocampal metabolism against MMSE, categorized by amyloid status

In low-Aβ subjects

MMSE correlated with HV (r=.14, p=.048) and with ACT (r=.26, p<.001). In contrast, MMSE did not correlate with HM (r=−.01, p=.860) nor with ACM (r=.04, p=.605). Similar results were found using PVE-corrected data (HM: r=.04, p=.527, ACM: r=.03, p=.622).

In high-Aβ subjects

MMSE correlated with HV (r=.29, p=.010), HM (r=.27, p=.015) and ACM (r=.30, p=.007). In contrast, ACT did not correlate with MMSE (r=.06, p=.619). Similar results were found using PVE-corrected data (HM: r=.31, p=.006, ACM: r=.29, p=.008).

Interactions

The interaction between Aβ status and MMSE in the model for HM was significant (p=.026) but not in the model for HV (p=.527), ACM (p=.104), or ACT (p=.067, in the opposite direction: MMSE predicts ACT in low- but not in high-Aβ). PVE-corrected data gave similar results (supplementary graph S3) but the interaction between MMSE and PiB status in the model for HM (p=.086) and ACM (p=.106) were both slightly above the threshold for significance.

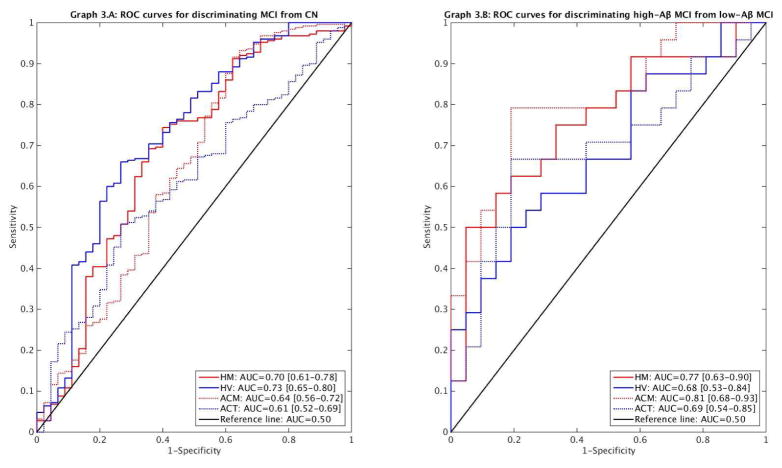

6. Sensitivity and specificity of imaging markers: Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves and area under the curve (AUC) analyses were adjusted for age, gender, and education

Hippocampal markers had higher AUC than cortical markers for discriminating MCI from CN (Graph 3.A), although the difference only reached statistical difference between HV and ACT (p=.009; HV-ACM: p=.169; HM-ACM: p=.304; HM-ACT: p=.212). In contrast, FDG markers had higher AUC than MRI markers for discriminating high-Aβ MCI from low-Aβ MCI (Graph 3.B), but without reaching statistical significance (all p>.200).

Graph 3.

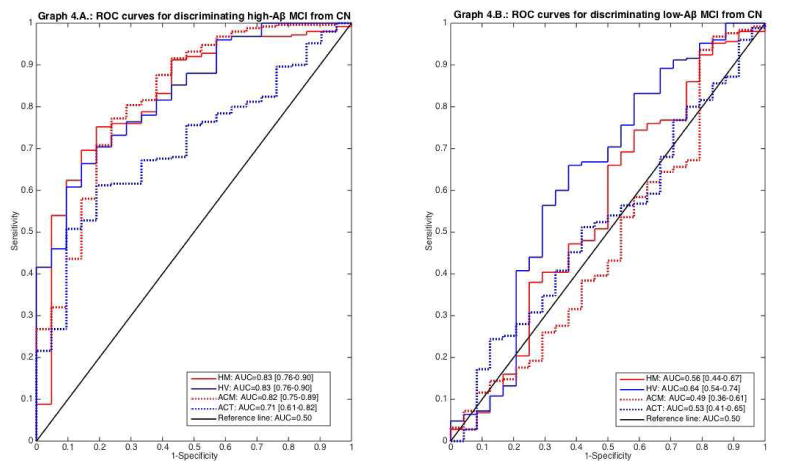

All biomarkers discriminated high-Aβ MCI from CN (Graph 4.A) and were significantly better for doing so than for discriminating low-Aβ MCI from CN (p<.050, DeLong test). Only HV significantly discriminated low-Aβ MCI from CN (Graph 4.B); the AUC for the other markers were not significantly greater than 0.5.

Graph 4.

DISCUSSION

This report investigated four AD biomarkers using two imaging modalities: structural MRI and FDG-PET and focused on two areas of interest: the hippocampal formation and the association cortex. The main finding is that hippocampal hypometabolism is only observed when cognitive impairment and Aβ are both present. Below we discuss the results in the context of other studies of volumetric and metabolic alterations occurring in MCI and high-Aβ CN.

1. Biomarkers in MCI

In this study, we found that HM was reduced in MCI compared to CN, in accordance with several previous reports [16–19]; but other studies did not find hippocampal hypometabolism in MCI [20–23]. However, previous studies focused on HM in MCI did not directly compare high- and low-Aβ MCI versus CN [24–26]. We observed that HM was only decreased in high-Aβ MCI, not in low-Aβ MCI. Aβ status may at least partially explain the discrepancies between previous studies, as these studies may differ in their relative number of low- and high-Aβ MCI. The present report confirms a previous one [17] highlighting “the crucial relevance of using reference-region-based scaling, and the higher sensitivity of PVE-corrected PET measures, to detect hippocampal hypometabolism in MCI” although we could also demonstrate reduced HM using FDG-PET data uncorrected for PVE. We found that HM correlated with HV, but the observed effects were still present after volume adjustment or partial volume correction (see supplementary graphs), showing that the hippocampal hypometabolism in high-Aβ MCI does not merely reflect gross hippocampal atrophy.

FDG values observed in low-Aβ MCI were close to normal, suggesting that metabolism is specifically decreased by Aβ, as shown in previous FDG work [26–28]. Other studies reported either decreased [29] or increased [30] ACM in low-Aβ MCI, indicating that this is likely a heterogeneous condition. Without further describing the pathological substrates observed in these patients, and looking more selectively at specific regions of interest according to the pathology, HM and ACM do not appear suitable to diagnose low-Aβ amnestic MCI. Other MTL pathologies, such as TDP-43 or hippocampal sclerosis, might differentially affect HV and HM [31], but in-vivo images of these pathologies are not yet available.

In the present results, ACM and HM were significantly associated with cognitive measures in the high-Aβ but not in the low-Aβ participants. In other words, FDG only decreases with cognition when cognitive impairment is due to Aβ. Noteworthy, HM did not correlate with any of the demographic data (and not with age in particular) unlike the other biomarkers we studied. This may contribute to the specificity of this biomarker for cognitive impairment and AD pathology. Previous studies showed that HM was lower in MCI that will subsequently decline than in non-decliners MCI [26, 32]. This is consistent with our results given the higher risk of decline among the MCI with elevated Aβ [33, 34] and is another argument for the high specificity of HM for symptomatic AD.

We observed that high-Aβ MCI had smaller HV than low-Aβ MCI, a finding consistent with other studies [35, 36] and the link between hippocampal atrophy with the risk of evolving to AD dementia [37, 38]. HM, ACM and HV all discriminated high-Aβ MCI from CN equally well, and more generally MCI from CN. But low-Aβ MCI also had hippocampal atrophy, although to a lower extent. Cognitive measures correlated with HV in participants with high-Aβ and with low-Aβ. HV also correlated with age. HV therefore appears to be less specific for AD pathology than HM or ACM but more sensitive to aging and potentially to other non-AD disorders. ROC curves confirmed that HV is highly discriminant for cognitive impairment but not as much for Aβ pathology. Cognitive follow-up of low-Aβ MCI with hippocampal atrophy is of particular interest as this may constitute an important risk for further cognitive decline [29].

As reported previously [39, 40], high-Aβ MCI have decreased ACT when compared to low-Aβ CN. However, ACT was less discriminant for high-Aβ MCI than the other biomarkers we studied. As it was shown for HV, ACT correlated with age, and with cognition in low-Aβ subjects, likely capturing decline related to non-AD pathology. We did not find decreased ACT in low-Aβ MCI although other groups have found cortical thinning in this population [41]. Of note, they found thinning in the left medial prefrontal and right anterior temporal cortices, regions that were not included in our ACT ROI that we choose to match the ACM ROI used in FDG-PET.

Overall, the four studied biomarkers proved to be more altered in high-Aβ MCI than in any other groups, arguing that this population is most probably at the prodromal stage of AD.

2. Biomarkers in high-Aβ CN

Both HV and ACM were significantly decreased in high-Aβ CN when compared to low-Aβ CN. In contrast, volume-adjusted HM was normal in high-Aβ CN, suggesting that decreased glucose metabolism in the medial temporal lobe may be a specific marker of cognitive impairment due to AD and not only a marker of Aβ. Unlike ACM, where associations with Aβ are observable in the preclinical stage of the disease [28], HM appears to be sensitive to the combination of Aβ and cognitive impairment. Similar observations have been made in functional MRI studies: alterations in hippocampal activity seem to arise in prodromal but not in preclinical AD [36]. The operationalization of the diagnostic criteria for preclinical AD proposes to use HV and ACM to define neurodegeneration (ND) [42]. Our data highlights an important limitation of this operationalization: the FDG signal in hippocampus may differ from that in neocortex, and from HV; thus indicating that not all ND has the same biological relevance, some ND is more specific for Aβ than other, and some ND is more specific for cognitive impairment. From this study, it appears that HM only decreased when both conditions are met. This might be interesting properties for tracking disease progression.

CONCLUSION

This study provides evidence of hippocampal hypometabolism in prodromal AD, together with other metabolic and structural alterations. Low-Aβ MCI demonstrated hippocampal atrophy, although to a lower extent. In contrast, FDG only decreased in the presence of Aβ: in the neocortex before; and in the hippocampus after cognitive impairment has occurred. HM could therefore be an interesting outcome for tracking disease progression. These cross-sectional results motivate a longitudinal study of HM in high-Aβ CN to determine whether this feature will predict progression to MCI due to AD.

Supplementary Material

Research in context.

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW

The authors reviewed the literature using PubMed and the keywords: “amyloid”, “hippocampus”, “FDG”, and “mild cognitive impairment (MCI)”. Hippocampal volume and association cortex metabolism are largely used as neurodegenerative markers in various AD stages. However, hippocampal metabolism in MCI is still a matter of debate. Hippocampal metabolism in low- and high-amyloid MCI still needs to be investigated. These relevant citations are appropriately cited.

INTERPRETATION

Our findings led to a decrease in hippocampal metabolism in high-amyloid MCI that is not present in low-amyloid MCI. Unlike cortical metabolism or hippocampal volume, hippocampal metabolism was normal in high-amyloid clinically normal elderly, making it a potential useful marker for tracking disease progression.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The manuscript discusses the findings in the context of other volumetric and metabolic studies. These cross-sectional results motivate a longitudinal study of hippocampal metabolism to determine whether this feature in normal elderly will predict progression to MCI.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS – FUNDING SOURCES

BJH received support from the Belgian American Education Foundation (BAEF, grant “Plateforme pour l’Education et le Talent”), from the Saint-Luc Foundation (grant “OEuvre du Calvaire-Malte”), and from the Belgian Neurological Society (BNS, RFYI 2013). RAS and KAJ have received support from National Institutes of Health/ National Institute on Aging (R01 AG046396, P01 AG036694, P50 AG00513421), Fidelity Biosciences, Harvard Neurodiscovery Center, and the Alzheimer’s Association. RAB received support from National Institutes of Health/ National Institute on Aging (P01 AG036694, P50 AG00513421) and the Harvard Neurodiscovery Center.

Abbreviations

- HM/HV

hippocampal metabolism/volume

- ACM/ACT

association cortex metabolism/thickness

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: none

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82(4):239–59. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hyman BT, et al. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klunk WE, et al. Imaging brain amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease with Pittsburgh Compound-B. Ann Neurol. 2004;55(3):306–19. doi: 10.1002/ana.20009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petersen RC, et al. Mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer disease in the community. Ann Neurol. 2013;74(2):199–208. doi: 10.1002/ana.23931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dubois B, et al. Advancing research diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s disease: the IWG-2 criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(6):614–29. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70090-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mormino EC, et al. Synergistic effect of beta-amyloid and neurodegeneration on cognitive decline in clinically normal individuals. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71(11):1379–85. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toledo JB, et al. Neuronal injury biomarkers and prognosis in ADNI subjects with normal cognition. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2014;2:26. doi: 10.1186/2051-5960-2-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bertens D, et al. Temporal evolution of biomarkers and cognitive markers in the asymptomatic, MCI, and dementia stage of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11(5):511–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.05.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jack CR, Jr, et al. Serial PIB and MRI in normal, mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: implications for sequence of pathological events in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2009;132(Pt 5):1355–65. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J Intern Med. 2004;256(3):183–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roy K, et al. Regional fluorodeoxyglucose metabolism and instrumental activities of daily living across the Alzheimer’s disease spectrum. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;42(1):291–300. doi: 10.3233/JAD-131796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herholz K. Cerebral glucose metabolism in preclinical and prodromal Alzheimer’s disease. Expert Rev Neurother. 2010;10(11):1667–73. doi: 10.1586/ern.10.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rousset E, Harel J, Dubreuil JD. Binding characteristics of Escherichia coli enterotoxin b (STb) to the pig jejunum and partial characterization of the molecule involved. Microb Pathog. 1998;24(5):277–88. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1997.0193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson KA, et al. Imaging of amyloid burden and distribution in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Ann Neurol. 2007;62(3):229–34. doi: 10.1002/ana.21164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Logan J, et al. Graphical analysis of reversible radioligand binding from time-activity measurements applied to [N-11C-methyl]-(−)-cocaine PET studies in human subjects. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1990;10(5):740–7. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1990.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nestor PJ, et al. Limbic hypometabolism in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Ann Neurol. 2003;54(3):343–51. doi: 10.1002/ana.10669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mevel K, et al. Detecting hippocampal hypometabolism in Mild Cognitive Impairment using automatic voxel-based approaches. Neuroimage. 2007;37(1):18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mosconi L, et al. Reduced hippocampal metabolism in MCI and AD: automated FDG-PET image analysis. Neurology. 2005;64(11):1860–7. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000163856.13524.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Santi S, et al. Hippocampal formation glucose metabolism and volume losses in MCI and AD. Neurobiol Aging. 2001;22(4):529–39. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(01)00230-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ishii K, et al. Relatively preserved hippocampal glucose metabolism in mild Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 1998;9(6):317–22. doi: 10.1159/000017083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ishii K, et al. Comparison of gray matter and metabolic reduction in mild Alzheimer’s disease using FDG-PET and voxel-based morphometric MR studies. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2005;32(8):959–63. doi: 10.1007/s00259-004-1740-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chetelat G, et al. Direct voxel-based comparison between grey matter hypometabolism and atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2008;131(Pt 1):60–71. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawachi T, et al. Comparison of the diagnostic performance of FDG-PET and VBM-MRI in very mild Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2006;33(7):801–9. doi: 10.1007/s00259-005-0050-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu L, et al. Dissociation between brain amyloid deposition and metabolism in early mild cognitive impairment. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e47905. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Y, et al. Regional analysis of FDG and PIB-PET images in normal aging, mild cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35(12):2169–81. doi: 10.1007/s00259-008-0833-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bruck A, et al. [11C]PIB, [18F]FDG and MR imaging in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013;40(10):1567–72. doi: 10.1007/s00259-013-2478-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen AD, Klunk WE. Early detection of Alzheimer’s disease using PiB and FDG PET. Neurobiol Dis. 2014;72(Pt A):117–22. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen AD, et al. Basal cerebral metabolism may modulate the cognitive effects of Abeta in mild cognitive impairment: an example of brain reserve. J Neurosci. 2009;29(47):14770–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3669-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caroli A, et al. Mild cognitive impairment with suspected nonamyloid pathology (SNAP): Prediction of progression. Neurology. 2015;84(5):508–15. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ashraf A, et al. Cortical hypermetabolism in MCI subjects: a compensatory mechanism? Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015;42(3):447–58. doi: 10.1007/s00259-014-2919-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toledo JB, et al. Clinical and multimodal biomarker correlates of ADNI neuropathological findings. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2013;1:65. doi: 10.1186/2051-5960-1-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pagani M, et al. MCI patients declining and not-declining at mid-term follow-up: FDG-PET findings. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2010;7(4):287–94. doi: 10.2174/156720510791162368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grimmer T, et al. The usefulness of amyloid imaging in predicting the clinical outcome after two years in subjects with mild cognitive impairment. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2013;10(1):82–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ma Y, et al. Predictive accuracy of amyloid imaging for progression from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer disease with different lengths of follow-up: a systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2014;93(27):e150. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wolk DA, et al. Amyloid imaging in mild cognitive impairment subtypes. Ann Neurol. 2009;65(5):557–68. doi: 10.1002/ana.21598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huijbers W, et al. Amyloid-beta deposition in mild cognitive impairment is associated with increased hippocampal activity, atrophy and clinical progression. Brain. 2015 doi: 10.1093/brain/awv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Landau SM, et al. Comparing predictors of conversion and decline in mild cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2010;75(3):230–8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e8e8b8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barnes J, et al. A meta-analysis of hippocampal atrophy rates in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30(11):1711–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tosun D, Joshi S, Weiner MW. Neuroimaging predictors of brain amyloidosis in mild cognitive impairment. Ann Neurol. 2013;74(2):188–98. doi: 10.1002/ana.23921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marshall GA, et al. Regional cortical thinning and cerebrospinal biomarkers predict worsening daily functioning across the Alzheimer’s disease spectrum. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;41(3):719–28. doi: 10.3233/JAD-132768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ye BS, et al. Hippocampal and cortical atrophy in amyloid-negative mild cognitive impairments: comparison with amyloid-positive mild cognitive impairment. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35(2):291–300. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jack CR, Jr, et al. An operational approach to National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association criteria for preclinical Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol. 2012;71(6):765–75. doi: 10.1002/ana.22628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.