Abstract

The enterocytes of the small intestine are occasionally exposed to pathogenic bacteria, such as Salmonella enteritidis 857, an etiologic agent of intestinal infections in humans. The expression of the heat shock response by enterocytes may be part of a protective mechanism developed against pathogenic bacteria in the intestinal lumen. We aimed at investigating whether S enteritidis 857 is able to induce a heat shock response in crypt- and villus-like Caco-2 cells and at establishing the extent of the induction. To establish whether S enteritidis 857 interfered with the integrity of the cell monolayer, the transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) of filter-grown, differentiated (villus-like) Caco-2 cells was measured. We clearly observed damage to the integrity of the cell monolayer by measuring the TEER. The stress response was screened in both crypt- and villus-like Caco-2 cells exposed to heat (40–43°C) or to graded numbers (101–108) of bacteria and in villus-like cells exposed to S enteritidis 857 endotoxin. Expression of the heat shock proteins Hsp70 and Hsp90 was analyzed by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting with monoclonal antibodies. Exposure to heat or Salmonella resulted in increased levels of Hsp70 and Hsp90 in a temperature-effect or Salmonella-dose relationship, respectively. Incubation of Caco-2 cells with S enteritidis 857 endotoxin did not induce heat shock gene expression. We conclude that S enteritidis 857 significantly increases the levels of stress proteins in enterocyte-like Caco-2 cells. However, our data on TEER clearly indicate that this increase is insufficient to protect the cells.

INTRODUCTION

Living cells exhibit a universal response to adverse changes in their environment, which is commonly known as the heat shock or stress response (Lindquist 1986; Welch 1992; Craig et al 1993). Apparently a defensive mechanism (Prohászka et al 2002), the transient heat shock response is a complex phenomenon that is rapidly induced and protects the cells from irreversible injury by stabilizing the synthetic and metabolic activities in the cell. The most obvious characteristics of the stress response are an enhanced synthesis of heat shock proteins (Hsps), commonly known as molecular chaperones, and a concomitant inhibition of overall protein synthesis (Lewis et al 1975; Koninkx 1976; Ovelgönne et al 1995). The Hsps were originally discovered in isolated heat-shocked Drosophila melanogaster salivary glands, where their appearance coincides with chromosomal puffs (Ritossa 1962). These chromosomal puffs represent specific transcription sites for synthesis of Hsps (Ritossa 1962; Lewis et al 1975; Koninkx 1976). In mammalian cells, induction of Hsps is considered to be regulated mainly at the transcriptional level by activity of a specific heat shock transcription factor (Morimoto 1993). In addition to transcriptional regulation, translational regulation has been described in insect cells (DiDomenico et al 1982), and there is also some evidence of this type of regulation in mammalian cells (Joshi-Barve et al 1992).

There is sufficient evidence to link the stress response to a consequent decrease in cellular sensitivity to stress. It has been clearly demonstrated that thermotolerance is conferred by increased levels of Hsps. This has been observed under conditions in which Hsps are induced by environmental stress (Li and Lazslo 1985) as well as by transfection of Hsp genes (Landry et al 1989; Parsell and Lindquist 1994).

A large and increasing body of information indicates that the heat shock response is elicited not only by hyperthermia but also by a wide variety of other stimuli (Hightower 1991; Welch 1992). Exposure of cells to such stressors, including oxidizing agents, anoxia, heavy metals, vitamin B6, sulfhydryl agents, and ethanol, results in a virtual shutdown of normal cellular protein synthesis, paralleled by a shift to high levels of Hsp synthesis (Koninkx 1976; Ovelgönne et al 1995). In the unstressed cells, constitutive levels of Hsps are involved in the restoration of unfolded or aggregated polypeptides to their native conformations, the proteolysis of proteins too damaged to refold, the assembly of proteins, and the translocation of proteins across membranes (Craig et al 1993; Wynn et al 1994). Because of these functions, Hsps are called molecular chaperones. This function of the Hsps enables the cell to survive during stress and promotes the resumption of normal cellular activities in the recovery period after stress. For a number of disease states, including tissue necrosis, viral infection, inflammation, and cancer, abnormally high expression levels of Hsps have been observed (Welch 1992; Wynn et al 1994). As a consequence of dietary intake, gut epithelial cells are regularly exposed to high levels of potentially harmful substances of dietary origin, such as lectins and bacteria.

Cell cultures displaying enterocyte-like differentiation are suitable models for studying the mechanisms underlying the proliferation and differentiation of intestinal epithelial cells at the cellular level (Hendriks et al 1991; Koninkx 1995; Ovelgönne et al 2000). The human colon carcinoma cell line Caco-2, which is phenotypically similar to human small intestinal enterocytes, is a particularly important in vitro model. At late confluency, these cells display differentiation characteristics of small intestinal enterocytes, both structurally and functionally (Pinto et al 1983; Koninkx 1995).

Through their adhesins, Salmonella species are capable of binding and invading mucosal barriers (Falkow 1991; Finlay and Falkow 1997). This behavior is also exhibited with mucosal models consisting of the polarized epithelial Caco-2 cell line (Finlay and Falkow 1990; van Asten et al 2000). Infection of this cell line with S typhimurium has been shown to cause structural lesions at the apical membrane of the cells and to elicit severe disruptions in the integrity of the epithelial monolayer (Jepson et al 1995, 1996). Because S enteritidis 857, a cause of food poisoning, is known as an etiologic agent of intestinal infections in humans, this strain (van Asten et al 2000) has been used in our experiments.

The experiments of this study were designed to investigate whether bacteria induce changes in the heat shock response of enterocyte-like Caco-2 cells. Both 5-day-old, undifferentiated Caco-2 cells, the in vitro counterpart of small intestinal crypt cells, and 19-day-old, differentiated ones, the in vitro counterpart of small intestinal villus cells, have been used in this investigation. In particular, we have examined the effect of S enteritidis 857 on the expression of Hsp70 and Hsp90 and established the extent of this expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

Caco-2 cells (American Type Culture Collection) were routinely grown and maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (Flow Laboratories, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) and cultured at 37°C in a humified atmosphere of 5% (v/v) CO2 in air. This medium was supplemented with 1% nonessential amino acids (Flow), 50 μg/mL gentamicin (Flow), 10 mM sodium bicarbonate, 25 mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethane-sulfonic acid (4-[2-hydroxyethyl]-1-piperazineethane-sulfonic acid), and 20% (v/v) fetal calf serum (FCS) (Ritmeester BV, Utrecht, The Netherlands). Supplemented DMEM devoid of gentamicin and FCS was referred to as plain DMEM. Cells were seeded at 40 000 cells/cm2 in tissue culture flasks (25 cm2) (Greiner, Alphen a/d Rijn, The Netherlands) and in 12-well tissue culture plates (4 cm2) (Greiner). Cells grown on Transwell, polycarbonate filter inserts of 12-well tissue culture plates (0.4-μm pore size) (Costar Europe Ltd, Badhoevedorp, The Netherlands), were seeded at 60 000 cells/cm2.

The Caco-2 cells were cultured for 5 days to achieve undifferentiated cells (the in vitro counterpart of crypt cells) or 19 days to achieve fully differentiated cell populations (the in vitro counterpart of villus cells). The cell culture medium was changed 3 times a week.

Heat shock

The duration of the heat shock (40°C, 41°C, and 42°C) was 1 hour, whereas the recovery period at 37°C lasted 6 hours. During the entire heat shock procedure, supplemented cell culture medium was used. Heat shocks were applied by placing the tissue culture flasks in water heated by a circulating thermostat DC10 (Haake, Karlsruhe, Germany). This thermostat maintained stable temperatures within 0.02°C. Under these conditions, temperature equilibration of the cell monolayers took about 30 seconds.

Exposure of Caco-2 cells to S enteritidis 857 and endotoxins

A single colony of S enteritidis 857 (van Asten et al 2000) grown on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar was inoculated into 10 mL of LB broth and grown overnight (16 hours) at 37°C with shaking (200 rpm). From this culture, 300 μL of the bacterial suspension was inoculated into 30 mL of LB broth and incubated with shaking (200 rpm) at 37°C for 2 hours to obtain logarithmically growing bacteria. Subsequently, bacteria were collected by centrifugation (10 minutes at 1500 × g; 22°C) and finally suspended in 30 mL of plain DMEM. The suspension was divided in 3 aliquots of 10 mL each. One of these aliquots was centrifuged (10 minutes at 1500 × g; 22°C), the supernatant was discarded, and bacteria were killed by suspending them in 96% ethanol for 30 minutes. They were then washed twice in plain DMEM and finally suspended in 10 mL of plain DMEM. To the second aliquot, chloramphenicol (20 μg/mL) was added just before infecting the cells. The Caco-2 cells were washed twice with 5 mL of plain DMEM before bacterial infection.

To establish whether bacteria themselves show a heat shock response, 20 μL of the bacterial suspension grown overnight was inoculated into 2 tubes containing 2 mL of LB broth and incubated at 37°C or 42°C for 60 minutes. After 2 washes with 5 mL of 0.01 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (0.01 M Na2HPO4, 0.01 M NaH2PO4, 0.9% [w/v] NaCl), pH 7.3, the bacterial pellets were boiled for 10 minutes in 1 mL of sample buffer (see Western blot analysis).

Because incubation of Caco-2 cells with S enteritidis 857 was done in plain DMEM, the amount of FCS was gradually reduced and replaced by Ultroser G, a serum substitute (GIBCO Europe, Hoofddorp, The Netherlands). This reduction was accomplished by replacing the cell culture medium containing 20% FCS with the medium containing 10% FCS and 1% Ultroser G on days 3 (for crypt-like Caco-2) and 17 (for villus-like Caco-2). This medium was then substituted by a medium containing 1% FCS and 2% Ultroser G 1 day later (days 4 and 18). On days 5 and 19, Caco-2 cells were incubated in quadruplicate with S enteritidis 857 (101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, and 108 bacteria/mL) for 1 hour at 37°C in 1 mL of plain DMEM. Monolayers of 19-day-old cells were also incubated with various amounts of S enteritidis (LPSSe) and Escherichia coli 0111:B4 (LPSEc) endotoxins (20 and 100 μg/mL) under the same conditions. After bacterial or endotoxin exposure, the cell monolayer was washed twice with 1 mL of gentamicin containing plain DMEM, and incubation was continued for a further 6 hours (recovery period) using the same medium.

Transepithelial electrical resistance of Caco-2 cell monolayers after exposure to bacteria

Mucosal integrity of Caco-2 cells seeded (60 000 cells/cm2) on polycarbonate, 0.4-μm–pore size tissue culture inserts in 12-well plates (insert growth area, 1 cm2) was verified by measuring the transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) with a Millicell-ERS V/Ω meter (Millipore Corporation, Bedford, MA, USA). This device contained a pair of chopstick electrodes, which facilitated the measurements. Cell monolayers were used for experiments 19 days after seeding, the mean TEER ± standard deviation for control cells being 205 ± 12 Ω/cm2 after subtracting the resistance of blank filters.

For exposure studies, filter-grown monolayers (apical volume, 600 μL; basolateral volume, 1500 μL) were first equilibrated with plain DMEM for 2 hours under cell culture conditions. Subsequently, 60 μL of apical DMEM was removed and replaced by the same volume of DMEM containing bacteria. After exposure to S enteritidis 857 (104, 105, 106, 107, and 108 bacteria/mL) for 1 hour in quadruplicate, monolayers were washed twice with 1 mL of gentamicin containing plain DMEM, and incubation was continued. Changes in TEER were measured 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 12, 24, and 48 hours after the washing step.

Western blot analysis

After the recovery period, the cells exposed to bacteria (4 cm2), as well as the heat-shocked cells (25 cm2), were washed twice at 4°C with 1 or 5 mL of PBS. Cells of 1 well or flask were scraped off into 1 or 5 mL of distilled water, and cell scrapings were sonicated at 0°C for 30 seconds at an amplitude of 24 μm with an MSE Soniprep 150 (Beun de Ronde BV, Abcoude, The Netherlands). The protein content of the resulting sonicates was determined (Smith et al 1985). An equal volume of sample buffer (twice the strength) was added to the protein samples, after which they were boiled for 10 minutes. Subsequently, the slots of the gel were loaded with equal amounts of proteins (12 μg) and the proteins separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on 10% gels. The sample buffer (normal strength) consisted of 125 mM Tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane-HCl, 4% SDS, 10% β-mercaptoethanol, 20% glycerol, and 0.0015% bromophenolblue, pH 6.8. Subsequently, proteins were transferred to Immobilon-P polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, according to the recommendations of the manufacturer (Millipore). Hsp70 (number SPA-810) and Hsp90 (number SPA-830) were detected using monoclonal antibodies purchased from Stressgen Biotechnologies Corporation (Victoria, British Columbia, Canada) and a peroxidase-coupled detection system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Quantification of the stained blots was performed on a Bio-Rad GS700 imaging densitometer.

To assess statistical significance between the quantified staining intensities of control Caco-2 cells and cells exposed to S enteritidis 857, an analysis of variance and comparison of means was used. Statistical significance was accepted at the P < 0.05 level.

RESULTS

S enteritidis 857 induced alterations in TEER

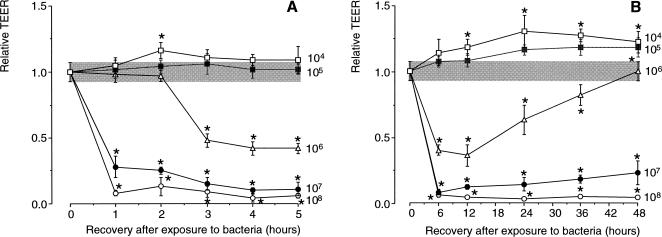

To investigate whether S enteritidis 857 interfered with the mucosal integrity of the Caco-2 cell monolayer, filter-grown, differentiated cells were incubated with graded numbers of bacteria in plain DMEM for 1 hour. Compared with control cells, S enteritidis 857–exposed, filter-grown, differentiated Caco-2 cells clearly showed changes in TEER. There was little (Fig 1B) or no change at all (Fig 1A) in TEER when cells were incubated with small numbers of bacteria (104 and 105). In contrast, exposure of the cells to further increasing numbers of bacteria (106, 107, and 108) revealed a significant decrease in TEER (Fig 1B). A full recovery of the TEER to control values, setting in 12 hours after the washing step with gentamicin, was observed when Caco-2 cells had been exposed to 106 bacteria. In contrast, there was no recovery at all after incubation with 107 and 108 bacteria. In this case, the values of the TEER were approaching the resistance of a blank filter (Fig 1B). Microscopic examination clearly showed that the cell monolayer with this low TEER value had been damaged severely.

Fig 1.

Dose dependency of Salmonella enteritidis 857 induced changes of the transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) in monolayers of differentiated Caco-2 cells after apical exposure. Caco-2 cells were grown on tissue culture inserts (pore size, 0.4 μm; growth area, 1 cm2). Before the experiments, filter-grown monolayers were first equilibrated with plain Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) for 2 hours and subsequently incubated at 37°C for 1 hour with S enteritidis 857 (104, 105, 106, 107, and 108 bacteria/mL). After 2 washes with 1 mL of gentamicin containing plain DMEM, the time course of the changes in TEER was measured. The results are expressed as the mean relative TEER ± standard deviation (SD). The dotted area represents the mean relative TEER ± SD of cell cultures not exposed to bacteria. Significant differences (P < 0.05) between the relative TEER levels of bacteria-exposed and control cells are indicated by an asterisk. The relative levels were established using 2 cell passages and triplicate cultures per passage. Figure 1A shows in detail the data for the initial 5 hours after exposure, whereas Figure 1B demonstrates the effect up to 48 hours

Heat shock induced synthesis of Hsp70 and Hsp90 in Caco-2 cells

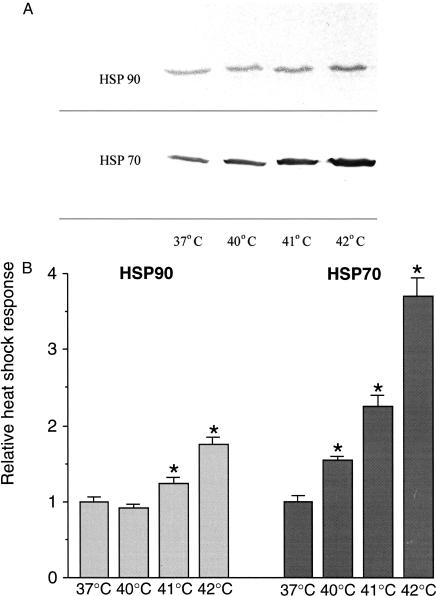

Before investigating the heat shock gene expression by bacteria in enterocyte-like Caco-2 cells, the capability of the cells to respond to heat shock was determined. Exposure of 19-day-old, fully differentiated Caco-2 cells to a temperature shock was found to induce the expression of Hsps. A temperature-effect relationship could be clearly observed for both Hsps (Fig 2 A,B). Compared with control cells maintained at 37°C, which expressed constitutive levels of Hsp70 and Hsp90, the levels of these Hsps at 42°C in 19-day-old, villus-like cells had increased significantly. A 1.8-fold increase was achieved in the level of expression for Hsp90, whereas the expression level for Hsp70 increased 3.7-fold. Cell cultures exposed to 43°C showed distinct indications of cell death, and the level of heat shock response was even lower than at 40°C (data not shown).

Fig 2.

Induction of Hsp70 and Hsp90 in differentiated Caco-2 cells. Hsp70 and Hsp90 were induced by exposure to 40°C, 41°C, and 43°C for 1 hour, followed by recovery at 37°C for 6 hours. (A) After these experimental procedures, the cells were processed for Western blotting and immunostaining. (B) Quantification of the Western blots revealed significant differences (P < 0.05) (indicated by an asterisk) between the relative levels of Hsps of heat shock–exposed and control cells for 2 sets of experiments, each done in triplicate

Also in 5-day-old, crypt-like cells, the level of expression for both Hsps increased significantly. Compared with 19-day-old cells, the levels in these cells had increased 1.6-fold for Hsp90 and 1.5-fold for Hsp70 (Fig 2 A,B). For comparison purposes, heat-shocked cells (1 hour exposure at 42°C; 6 hour recovery at 37°C) were used as positive controls and those maintained for 7 hours at 37°C as negative ones.

It was not possible to detect bacterial Hsp70 and Hsp90 by using the antibodies used in this study. This confirmed their suitability for the present experiments (data not shown).

Hsp response in S enteritidis 857 exposed crypt-like and villus-like Caco-2 cells

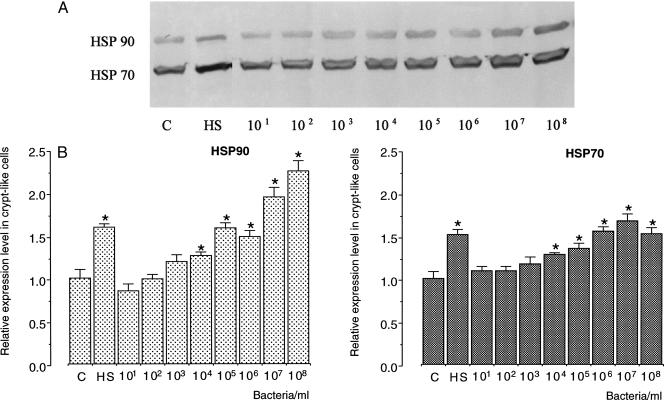

To investigate whether S enteritidis 857 was able to induce the heat shock response in enterocyte-like Caco-2 cells, cells were incubated with bacteria in plain DMEM for 1 hour at 37°C. When compared with control, 5-day-old, undifferentiated, crypt-like Caco-2 cells, a significant increase in the level of Hsp90 was achieved after exposure to bacteria. After incubation with 105, 106, 107, and 108 bacteria, the level of expression of Hsp90 approached the expression of this protein after heat shock at 42°C (Fig 3A). The expression level of Hsp70 in crypt-like Caco-2 cells also significantly increased after incubation with 104, 105, 106, 107, and 108 S enteritidis 857 bacteria. When cells were exposed to 107 or 108 bacteria, a 1.5-fold increase over the control level was observed. This level of Hsp70 after bacterial exposure matched the level in heat-shocked (42°C) cells (Fig 3B).

Fig 3.

Expression levels of Hsp70 and Hsp90 in 5-day-old, undifferentiated Caco-2 cells after exposure to Salmonella enteritidis 857. Cells were exposed for 1 hour to 101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, or 108 bacteria/mL of plain Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM). (A) After 6 hours of recovery in plain DMEM containing gentamicin, cells were processed for Western blotting and immunostaining. (B) Quantification of the Western blots revealed significant differences (P < 0.05) (indicated by an asterisk) between the relative levels of heat shock proteins (Hsps) of Salmonella enteritidis 857–exposed and control cells. The relative levels of Hsps were established using 2 cell passages and triplicate cultures per passage. The results are expressed as the relative amount of Hsp ± standard deviation. (C, levels of Hsp70 and Hsp90 in control Caco-2 cells; HS, levels of Hsp70 and Hsp90 in heat-shocked cells [1 hour exposure at 42°C; 6 hours recovery at 37°C])

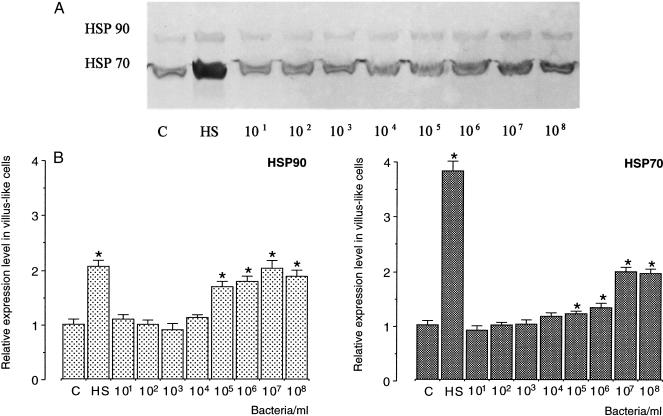

Exposure of 19-day-old, differentiated, villus-like Caco-2 cells to S enteritidis 857 was found to induce the expression of both Hsp70 and Hsp90 (Fig 4A). With respect to Hsp90, 107 or 108 S enteritidis 857 bacteria appeared to be needed to bring about the same 1.7-fold increase in the heat shock response, which is inducible at 42°C (Fig 4B). However, compared with the 3.7-fold increase in the level of expression of Hsp70 in heat-shocked (42°C) cells, the heat shock response of this protein after exposure to bacteria was only moderate. In this case, 107 or 108 bacteria were needed to achieve a 1.5-fold increase over the control levels in 19-day-old, villus-like Caco-2 cells (Fig 4B).

Fig 4.

Expression levels of Hsp70 and Hsp90 in 19-day-old, differentiated Caco-2 cells after exposure to Salmonella enteritidis 857. Cells were exposed for 1 hour to 101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, or 108 bacteria/mL of plain Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM). (A) After 6 hours of recovery in plain DMEM containing gentamicin, cells were processed for Western blotting and immunostaining. (B) Quantification of the Western blots revealed significant differences (P < 0.05) (indicated by an asterisk) between the relative levels of heat shock proteins (Hsps) of Salmonella enteritidis 857–exposed and control cells. The relative levels of Hsps were established using 2 cell passages and triplicate cultures per passage. The results are expressed as the relative amount of Hsp ± standard deviation. (C, levels of Hsp70 and Hsp90 in control Caco-2 cells; HS, levels of Hsp70 and Hsp90 in heat-shocked cells [1 hour exposure at 42°C; 6 hours recovery at 37°C])

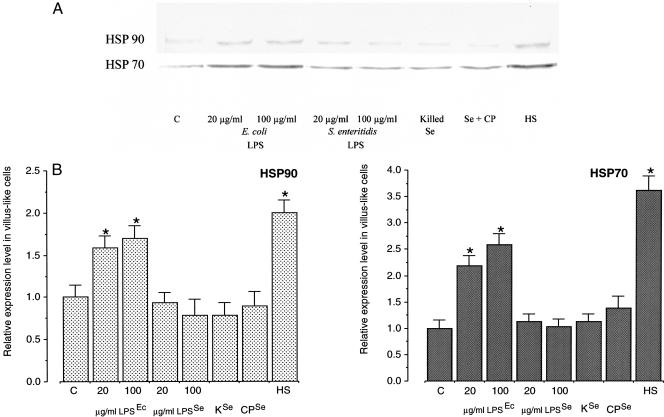

No induction at all of Hsp70 and Hsp90 was found in Caco-2 cells incubated with S enteritidis 857 (108) in the presence of chloramphenicol, killed bacteria, or its endotoxin (20 or 100 μg/mL). In these cases, the levels of expression of these proteins were similar to their expression in control cells. However, exposure to E coli 0111:B4 endotoxin (20 or 100 μg/mL) induced a significant expression of these proteins (Fig 5 A,B).

Fig 5.

Expression levels of Hsp70 and Hsp90 in 19-day-old, differentiated Caco-2 cells after exposure to Salmonella enteritidis 857 or Escherichia coli endotoxins, killed or S enteritidis incubated with chloramphenicol. Cells were exposed to S enteritidis 857 or E coli 0111:B4 lipopolysaccharides (LPS) at 20 or 100 μg/mL of plain Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) for 1 hour. In another experiment, cells were exposed to either killed or live S enteritidis incubated with 20 μg/mL of chloramphenicol at 108 bacteria/mL of plain DMEM for 1 hour. (A) After 6 hours of recovery in plain DMEM containing gentamicin, cells were processed for Western blotting and immunostaining. (B) Quantification of the Western blots revealed significant differences (P < 0.05) (indicated by an asterisk) between the relative levels of Hsps of heat shock or E coli lipopolysaccharide (LPS)–exposed cells and control cells. The relative levels of Hsps were established using 2 cell passages and triplicate cultures per passage. The results are expressed as the relative amount of Hsp ± standard deviation. (C, levels of Hsp70 and Hsp90 in control Caco-2 cells; HS, levels of Hsp70 and Hsp90 in heat-shocked cells (1 hour exposure at 42°C; 6 hours recovery at 37°C]; LPSEc/LPSSe, Escherichia coli/S enteritidis lipopolysaccharide; CPSe/Se+CP, S enteritidis incubated with chloramphenicol; KSe, killed S enteritidis)

DISCUSSION

The highly conserved set of stress proteins is involved in coping with chemical and physical stress in all living cells (Lindquist 1986; Welch 1992; Craig et al 1993). The data presented in this investigation clearly demonstrate that S enteritidis 857 increases the levels of Hsp70 and Hsp90 in these cells. In both crypt-like and villus-like cells, the Hsp content increases significantly on exposure to bacteria.

Binding of bacteria to cells lining the intestine induces a decrease in the number of microvilli covering the cells, and simultaneously with this change, ruffle formation takes place (Sanger et al 1996). Recent studies with Salmonella species have revealed that membrane ruffling, which is associated with the site of entry of the bacteria, occurs in the apical membrane during bacterial binding and invasion (Francis et al 1992; Galan 1994). At these sites, a rearrangement of actin filaments take place. Both Salmonella-induced ruffles and the subsequent entry of bacteria are sensitive to inhibitors of actin filament polymerization (Francis et al 1993). Actin disruption of polarized Caco-2 cells can augment internalization of bacteria, in which exposure of the lateral surface of the enterocytes appears to be involved (Wells et al 1998). Such a disruption distorts microvilli and decreases TEER. Our experiments with filter-grown cells, which clearly show dose-related changes in TEER (Fig 1), suggest loss of mucosal integrity. These changes are most pronounced after exposure of cells to 107 and 108 bacteria. On the basis of these findings, it is reasonable to suggest that actin filaments are recruited and remodeled by S enteritidis 857 so as to enter the Caco-2 cells. Like the lectin-induced depolymerization of the actin filaments in differentiated Caco-2 cells (Ovelgönne et al 2000), the Salmonella-induced cytoskeletal changes in Madin-Darby canine kidney cells occur within minutes of infection (Francis et al 1992; Koninkx 1995).

The potential of enterocyte-like Caco-2 cells to induce the synthesis of Hsp70 and Hsp90 has been investigated in cultures that were exposed to temperatures ranging between 40°C and 42°C. In Figure 2 A,B, it is clearly demonstrated that the levels of the Hsps in differentiated Caco-2 cells increase with increasing temperatures. Also, 5-day-old, undifferentiated cells showed a distinct heat shock response at 42°C. Whereas the levels of Hsp70 and Hsp90 in 5-day-old cells were very similar, the response in 19-day-old ones differed considerably.

The results of our investigations also show that after exposure of both crypt-like, undifferentiated and villus-like, differentiated Caco-2 cells to S enteritidis 857, a significant increase in the levels of Hsp70 and Hsp90 could be detected by Western blot analysis (Figs 3 A,B and 4 A,B). These Hsps were not of bacterial origin, considering that the monoclonal antibodies did not react with S enteritidis 857 Hsps in either control (37°C) or heat-shocked (42°C) bacteria (data not shown). Hsp synthesis has also been induced in Caco-2 cells after incubation with E coli C25 or its endotoxin (Deitch et al 1995). We were able to confirm the induction of Hsp70 and Hsp90 by E coli 0111:B4 endotoxin (Fig 5 A,B). However, our results clearly showed that S enteritidis 857 endotoxin did not induce the expression of Hsp70 and Hsp90. In addition, neither killed bacteria nor bacteria in the presence of cholamphenicol were able to induce Hsp70 and Hsp90 syntheses (Fig 5 A,B). This observation alludes to the fact that another aspect of this bacterium is responsible for these changes. It is tempting to suggest that the invasion process itself is involved. The observed stress response by enterocyte-like Caco-2 cells may be part of a mechanism of protection developed by intestinal epithelial cells in general to deal with potential pathogens in the intestine. The constitutive levels of Hsps in the cells (Figs 2 A,B, 3 A,B, and 4 A,B) are obviously insufficient to protect these cells from invasion by bacteria. Even the increase in Hsps induced by bacterial exposure did not protect the cells. However, such protection may be developed too late. To withstand tissue damage by bacteria and to immediately cope with this damage, cells would most likely benefit from previously induced high levels of Hsps.

Bacteria are known to interfere with the cytoskeleton of gut cells. After the onset of bacterial exposure, depolymerization of the actin filaments of the cytoskeleton takes place almost instantly (Francis et al 1992; Koninkx 1995). There is an increasing amount of evidence that emphasizes the relationship between Hsps and the cytoskeleton (Koyasu et al 1986; Lavoie et al 1993; Liang and MacRae 1997; Musch et al 1999; Xu et al 2002). Induction of Chinese hamster Hsp27 gene expression in mouse NIH/3T3 cells prevents actin depolymerization during acute exposure to cytochalasin (Lavoie et al 1993). In human colonic epithelial Caco-2/bbe cells, Hsp72 protects the integrity of the actin cytoskeleton against oxidant-induced injury (Musch et al 1999). Liang and MacRae (1997) concluded in their review that Hsp60, Hsp70, Hsp90, and Hsp100 have different but cooperative roles in the formation and function of the eukaryotic cell cytoskeleton. Studies on the function of Hsp70 and Hsp90 revealed the actin-binding activity of these proteins (Liang and MacRae 1997), which stabilizes the actin filaments by cross-linking (Koyasu et al 1986). With respect to Hsp90, this protein was found to bind to at most 10 actin molecules in the polymerized form (Nishida et al 1986), and its localization in membrane ruffles was revealed by immunofluorescence staining using specific antisera (Koyasu et al 1986). On the basis of these findings and our own results (Figs 3 A,B and 4 A,B), we suggest that high levels of Hsp70 and Hsp90 in Caco-2 cells, which are known to decrease the cellular sensitivity to stress, may be able to inhibit bacteria from adhering and invading through stabilization of the Caco-2 cytoskeleton. If previously induced high levels of Hsps are directed to the stabilization of the cytoskeleton, then bacteria might be unable to use the actin filaments for their own purposes. Further support for this working hypothesis must come from bacterial adherence and invasion experiments with heat-shocked, enterocyte-like Caco-2 cells.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Henk Halsema for drawing the figures and Harry Otter for the preparation of the photographs. The Commission of European Communities supported this collaborative work. It was a European COST Action 98 program coordinated by Dr A. Pusztai.

REFERENCES

- Craig EA, Gambill BD, Nelson RJ. Heat shock proteins: molecular chaperones of protein biogenesis. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:402–414. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.2.402-414.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deitch EA, Beck SC, Cruz NC, De Maio A. Induction of heat shock gene expression in colonic epithelial cells after incubation with Escherichia coli or endotoxin. Crit Care Med. 1995;23:1371–1376. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199508000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiDomenico BJ, Bugaisky GE, Lindquist S. Heat shock and recovery are mediated by different translational mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79:6181–6185. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.20.6181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkow S. Bacterial entry into eukaryotic cells. Cell. 1991;65:1099–1102. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90003-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay BB, Falkow S. Salmonella interacts with polarized human intestinal Caco-2 epithelial cells. J Infect Dis. 1990;162:1096–1106. doi: 10.1093/infdis/162.5.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay BB, Falkow S. Common themes in microbial pathogenicity revisited. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:136–169. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.2.136-169.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis CL, Ryan TA, Jones BD, Smith SJ, Falkow S. Ruffles induced by Salmonella and other stimuli direct macropinocytosis of bacteria. Nature. 1993;364:639–642. doi: 10.1038/364639a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis CL, Starnbach MN, Falkow S. Morphological and cytoskeletal changes in epithelial cells occur immediately upon interaction with Salmonella typhimurium grown under low-oxygen conditions. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:3077–3087. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galan JE. Salmonella entry into mammalian cells: different yet converging signal transduction pathways? Trends Cell Biol. 1994;4:196–199. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(94)90136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks HGCJM, Kik MJL, Koninkx JFJG, van den Ingh TS, Mouwen JM. Binding of kidney bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) isolectins to differentiated human colon carcinoma Caco-2 cells and their effect on cellular metabolism. Gut. 1991;32:196–201. doi: 10.1136/gut.32.2.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hightower LE. Heat shock, stress proteins, chaperones and proteotoxicity. Cell. 1991;66:191–197. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90611-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jepson MA, Colares-Buzato CB, Clark MA, Hirst BH, Simmons NL. Rapid disruption of epithelial barrier function by Salmonella typhimurium is associated with structural modification of intercellular junctions. Infect Immun. 1995;63:356–359. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.1.356-359.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jepson MA, Lang TF, Reed KA, Simmons NL. Evidence for a rapid, direct effect on epithelial monolayer integrity and transepithelial transport in response to Salmonella invasion. Eur J Physiol. 1996;432:225–233. doi: 10.1007/s004240050128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi-Barve S, De Benedetti A, Rhoads RE. Preferential translation of heat shock mRNAs in HeLa cells deficient in protein synthesis initiation factors eIF-4E and eIF-4g. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:21038–21043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koninkx JFJG. Protein synthesis in salivary glands of Drosophila hydei after experimental gene induction. Biochem J. 1976;158:623–628. doi: 10.1042/bj1580623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koninkx JFJG 1995 Enterocyte-like Caco-2 cells as a tool to study lectin interaction. In: Lectins: Biomedical Perspectives, ed Pusztai A, Bardocz S. Taylor & Francis, London, 81–101. [Google Scholar]

- Koyasu S, Nishida E, and Kadowaki T. et al. 1986 Two mammalian heat shock proteins, HSP90 and HSP100, are actin binding proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 83:8054–8058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry J, Chrétien P, Lambert H, Hickey E, Weber LA. Heat shock resistance conferred by expression of the human HSP27 gene in rodent cells. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:7–15. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie JN, Gingras-Breton G, Tanguy RM, Landry J. Induction of Chinese hamster HSP27 gene expression in mouse cells confers resistance to heat shock. HSP27 stabilization of the microfilament organization. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:3420–3429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M, Helmsing PJ, Ashburner M. Parallel changes in puffing activity and patterns of protein synthesis in salivary glands of Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1975;72:3604–3608. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.9.3604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li GC, Lazslo A 1985 Thermotolerance in mammalian cells: A possible role for HSPs. In: Changes in Eukaryotic Gene Expression in Response to Environmental Stress, ed Atkinson BG, Walden DB. Academic Press, New York, 227–254. [Google Scholar]

- Liang P, MacRae TH. Molecular chaperones and the cytoskeleton. J Cell Sci. 1997;110:1431–1440. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.13.1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist S. The heat shock response. Annu Rev Biochem. 1986;55:1151–1191. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.55.070186.005443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto RI. Cells in stress: transcriptional regulation of heat shock genes. Science. 1993;259:1409–1410. doi: 10.1126/science.8451637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musch MW, Sugi K, Straus D, Chang EB. Heat shock protein 72 protects against oxidant-induced injury of barrier function of human colonic epithelial Caco-2/bbe cells. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:115–122. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70557-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida E, Koyasu S, Sakai H, Yahara I. Calmodulin-regulated binding of the 90 kDa heat shock protein to actin filaments. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:16033–16036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ovelgönne H, Bitorina M, van Wijk R. Stressor specific activation of heat shock genes in H35 rat hepatoma cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1995;135:100–109. doi: 10.1006/taap.1995.1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ovelgönne JH, Koninkx JFJG, Pusztai A, Bardocz S, Kok W, Ewen SW, Hendriks HG, van Dijk JE. Decreased levels of heat shock proteins in gut epithelial cells after exposure to plant lectins. Gut. 2000;46:679–687. doi: 10.1136/gut.46.5.680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsell D, Lindquist S 1994 Heat shock proteins and stress tolerance. In The Biology of Heat Shock Proteins and Molecular Chaperones, ed Morimoto RI, Tissières A, Georgopoulos C. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, 457–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto M, Robine-Leon S, and Appay MD. et al. 1983 Enterocyte-like differentiation and polarization of the human colon carcinoma cell line Caco-2 in culture. Biol Cell. 47:323–330. [Google Scholar]

- Prohászka Z, Singh M, Nagy K, Kiss E, Lakos G, Duba J, Füst G. Heat shock protein 70 is a potent activator of the human complement system. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2002;7:17–22. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(2002)007<0017:hspiap>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritossa FM. A new puffing pattern induced by temperature shock and DNP in Drosophila. Experientia. 1962;18:571–573. [Google Scholar]

- Sanger JM, Chang R, Ashton F, Kaper JB, Sanger JW. Novel form of actin-based motility transports bacteria on the surfaces of infected cells. Cell Motil Cytoskelet. 1996;34:279–287. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0169(1996)34:4<279::AID-CM3>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PK, Krohn RI, and Hermanson GT. et al. 1985 Measurement of protein using bicinchoninic acid. Ann Biochem. 159:76–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Asten FJAM, Hendriks HGCJM, Koninkx JFJG, van der Zeijst BA, Gaastra W. Inactivation of the flagellin gene of Salmonella enterica serotype enteritidis strongly reduces invasion into differentiated Caco-2 cells. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2000;185:175–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch WJ. Mammalian stress response: cell physiology, structure/function of stress proteins, and implications for medicine and disease. Physiol Rev. 1992;72:1063–1081. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.4.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells CL, van de Westerlo EM, Jechorek RP, Haines HM, Erlandsen SL. Cytochalasin-induced actin disruption of polarized enterocytes can augment internalization of bacteria. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2410–2419. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2410-2419.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynn RM, Davie JR, Cox RP, Chuang DT. Molecular chaperones: heat-shock proteins, foldases, and matchmakers. J Lab Clin Med. 1994;124:31–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W, Mimnaugh EG, Kim JS, Trepel JB, Neckers LM. Hsp90, not Grp94, regulates the intracellular trafficking and stability of nascent ErbB2. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2002;7:91–96. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(2002)007<0091:hngrti>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]