Abstract

The removal of miswired synapses is a fundamental prerequisite for normal circuit development, leading to clinical problems when aberrant. However, the underlying activity-dependent molecular mechanisms involved in synaptic pruning remain incompletely resolved. Here we examine the dynamic properties of intracellular calcium oscillations and test a role for cAMP signaling during synaptic refinement in intact Drosophila embryos using optogenetic tools. We provide in vivo evidence at the single gene level that the calcium-dependent adenylyl cyclase rutabaga, the phosphodiesterase dunce, the kinase PKA, and Protein Phosphatase 1 (PP1) all operate within a functional signaling pathway to modulate Sema2a-dependent chemorepulsion. We find that presynaptic cAMP levels are required to be dynamically maintained at an optimal level to suppress connectivity defects. We also propose that PP1 may serve as a molecular link between cAMP signaling and CaMKII in the pathway underlying refinement. Our results introduce an in vivo model where presynaptic cAMP levels, downstream of electrical activity and calcium influx, act via PKA and PP1 to modulate the neuron's response to chemorepulsion involved in the withdrawal of off-target synaptic contacts.

Keywords: pruning, chemorepulsion, activity-dependent, critical period, growth cone

INTRODUCTION

The guidance of axons toward their synaptic targets depends on multiple diffusible and surface-associated chemotropic signals (Kolodkin and Tessier-Lavigne, 2011). Early synaptic development is generally accompanied by the withdrawal of inappropriate contacts, a mechanism known as synaptic refinement or pruning. This form of error correction typically involves neural and/or synaptic activity (Kano and Hashimoto, 2009). Although neural activity was found to play a crucial role in neural network refinement over fifty years ago (Wiesel and Hubel, 1963), much remains to be learned about the underlying molecular pathways and their dynamics. Interest in the mechanisms governing synaptic pruning is motivated by its potential role in clinical disorders, including schizophrenia and autism (Tang et al., 2014; Sekar et al., 2016).

A remarkable feature of activity-dependent synaptic refinement is the role played by low frequency electrical oscillations, often in the range of 0.01 Hz. The oscillations may coordinate dynamic changes in the activity of second messenger systems, or be part of a homeostatic mechanism to maintain signaling molecules within an optimal range. Low frequency oscillatory activity is observed during the refinement of synaptic connections in the visual system and spinal cord of vertebrates, as well as at the embryonic and larval Drosophila NMJ (Meister et al., 1991; Wong, 1999; Zhang and Poo, 2001; Hanson and Landmesser, 2004; Nicol et al., 2007; Carrillo et al., 2010; Ackman et al., 2012).

Previous work showed that synaptic refinement of the Drosophila NMJ also depends on an early critical period of electrical excitability (Jarecki and Keshishian, 1995). A low frequency (0.01 Hz) oscillation of membrane potential activates presynaptic voltage-gated calcium (Ca2+) channels at the developing NMJ (Carrillo et al., 2010). Ca2+ levels modulate the motoneuron's response to the muscle-secreted transsynaptic chemorepellant Sema2a (Carrillo et al., 2010). Mutations that affect electrical excitability (such as the Na(v)1 channel paralytic and the Ca(v)2.1 channel cacophony), or of genes that encode Sema2a, its presynaptic receptor PlexinB, or CaMKII all share similar defects: ectopic neuromuscular contacts on up to 40% of bodywall muscles (Carrillo et al., 2010).

In addition to CaMKII, other Ca2+-dependent effectors may also influence the chemorepellant response to Sema2a, including the Ca2+-dependent adenylyl cyclase encoded by the rutabaga gene. A role for cyclic nucleotide signaling in growth cone chemotropic-dependent motility in vitro is well-established, but its role in vivo during synapse formation is not as well understood. Using molecular and optogenetic methods we monitored the intracellular Ca2+ signals at the developing neuromuscular boutons of intact embryos, and examined how the Ca2+-dependent adenylyl cyclase, cAMP phosphodiesterase, cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA), and protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) collectively regulate synaptic refinement. Our results indicate that the refinement of synaptic connections in vivo requires dynamically varying second messenger systems, including Ca2+ and cAMP, to engage multiple downstream effectors, including PKA and PP1, for the modulation of chemorepulsion and the refinement of synapses.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Fly stocks

Animals were reared on standard cornmeal medium at 25 °C, except where noted. The GeneSwitch (GS) GAL4 experiments used a molasses food with or without the steroid activator RU486 (Osterwalder et al., 2001). The wild-type control used throughout was the isogenic Canton S (CS5) line.

We thank the following organizations and individuals for providing stocks: Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center: rut1 (BL9404), rutDf (Df(1)ED7261, BL9218), dncDf (Df(1)BSC531, BL25059), elavC155-GAL4 (BL458), UAS-rut (isolated from BL9405), UAS-GFP (BL35786; control for TRiP RNAi lines), UAS-rut-RNAi (BL27035), UAS-dnc-RNAi (BL53344), UAS-PKAC1-RNAi (BL31599), UAS-PKAC2-RNAi (BL55859), UAS-PKAC3-RNAi (BL55860), UAS-PKAR2-RNAi (BL34983), pp1α96A2 (BL23698), pp1-8787Bg-3 pp1α96A2 (BL23699), UAS-pp1α96A2 (BL23700), UAS-pp187B-RNAi (BL32414), UAS-pp1α96A-RNAi (BL40906), UAS-TNT-E (BL28838), UAS-GCaMP5attP40 (BL42037), UAS-myr-TdTomato (BL32223). Vienna Drosophila Resource Center: UAS-PKARI-RNAi (VDRC 103720), UAS-PKAR2-RNAi (VDRC 101763), UAS-pp1-13C-RNAi (VDRC 107770), UAS-pp1α96A-RNAi (VDRC 105525), UAS-pp2A-RNAi (VDRC 35172). G Boulianne, University of Toronto: UAS-dnc (Cheung et al., 1999). A Kolodkin, Johns Hopkins Med. School: Sema2aB65(Wu et al., 2011), pka RIIEP(2)2162 (Park et al., 2000), UAS-PlexinB (Hu et al., 2001). R Ordway, Penn State, State College: cacS, cacL13/FM7i, UAS-cac1-eGFP-786C. P Garrity, Brandeis University: UAS-dTrpA1. T Littleton, MIT: cacNT27. M Schwaerzel, Freie Universitaet Berlin, Germany: UAS-bPAC (Stierl et al., 2011). S Sigrist, Freie Uniersitaet Berlin, Germany: GluRIIA-mRFP (Rasse et al., 2005). P Verstreken, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium: n-syb-GAL4 (Khuong et al., 2010). CF Wu, University of Iowa: y rut2 (Bellen et al., 1987), y dncM11 cv v/X^X y f/Y, y dncM14 cv/X^X y f/Y, (Byers et al., 1981), dnc1(Dudai et al., 1976), y dnc2 ec f (Bellen and Kiger, 1988). B White, NIH and D Kalderon, Columbia University: yw; UAS-PKAmC* (UAS-PKAact), yw;;UAS-BDK35 (UAS-PKAinh) (Li et al., 1995; Davis et al., 1998). S Bernstein, San Diego State University: Mhc1(Wells et al., 1996). A DiAntonio, Washington University: MHC-Sh-CD8-GFP (Zito et al., 1997; Zito et al., 1999). Other lines used were the pan-neuronal elav-GS-GAL4 driver (Osterwalder et al., 2001), and the pan-muscular MHC-GAL4 driver (Schuster et al., 1996). All RNAi experiments included a UAS-Dicer transgene.

For the conditional genetic rescue experiments using GeneSwitch (GS), the elav-GS-GAL4 driver was activated in embryos by feeding parental flies for at least four days with food containing 10 μg/ml RU486 (mifepristone) prior to collecting eggs. For the bPAC experiments, parental feeding was limited to 24, 48 or 96 hrs, as noted. Larvae with GS activation were also raised on media containing 10 μg/ml RU486. Control animals were raised under identical conditions, but with media lacking RU486. For the induced expression of UAS-PKAact, parental flies were fed RU486 for four days, and larvae were allowed to develop in RU486-containing food until late first instar stage, after which they were transferred to media lacking RU486.

Immunolabeling of larvae and analysis of ectopic contacts

Crawling third instar larvae were fillet dissected, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 1h at room temperature, and washed in PBS. Primary antibodies were diluted in a solution of 1% BSA diluted in PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100 and incubated at 4° C overnight, whereas secondary antibodies were diluted in PBS for a 4h incubation at room temperature. Primary antibodies and dilutions from stock concentrations were: 1:250 Goat anti-HRP (MP Biomedicals), 1:5000 Rabbit anti-GluRIIC (DiAntonio, Washington U.), 1:250 mouse anti-Brp NC82 Mab (Developmental Studies Hybridoma bank), 1:1000 Rabbit anti-Synaptotagmin (H. Bellen, Baylor College of Medicine). Fluorescent visualization was with Alexa-conjugated secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes) at a 1:1000 dilution. Rhodamine conjugated phallodin 1:100 (Molecular Probes) was used to label F-actin in muscle. Labeling of NMJs was with anti-HRP immunocytochemistry, using diaminobenzidine (DAB) visualization (Berke et al., 2013). Frequency of positive immunolabeled ectopic contacts is presented as mean ± the standard error of the mean, s.e.m.

Ectopic contacts were scored on muscle fibers 7 and 6 in the abdominal segments A2–A7 in 3rd instar larval fillet preparations. An ectopic contact was counted if (1) the native innervation was present, (2) the ectopic innervation was not localized to the native innervation site, and (3) the muscle fibers had no evident defects (tissue damage or mislocalization). Data were collected from 3rd instar larvae where at least 8 hemisegments could be scored. An ectopic contact frequency was determined for each larva, calculated as the percentage of hemisegments scored, in which at least one ectopic contact was observed on muscle fiber 7&6 pairs. These values were then averaged over the number (n) of larvae examined, and are presented as the mean ectopic contact frequency ± the standard error of the mean, s.e.m. To account for natural variability and independent biological replicates, data for each group was collected from at least three crosses that contained multiple parents (typically 5 females and 3 males) and were set at different time points with the corresponding controls, unless otherwise stated in the text. We defined one data point as the average frequency of ectopic contacts observed in one animal where at least 8 different hemisegments could be scored. This means, for n=10 animals, at least 80 different hemisegments were scored. All data points were included, no outliers were excluded. Data from females and males were pooled unless otherwise indicated. Power analysis for ectopic counts was calculated using GPower software 3.0.10 (University of Duesseldorf, (Faul et al., 2007)). For an alpha level of 0.05 and a power level of 0.8, a sample size of n=9 was calculated for the comparison of two independent means with typical values of 15±12% and 30±12% based on the current and previous studies (Jarecki and Keshishian, 1995; White et al., 2001; Carrillo et al., 2010). In this study, sample sizes range from 8 to 51 animals, with a median of 18 and a total average of 20.3 animals considering all analyzed data groups. Statistical significance was calculated using t-test or ANOVA, using Prism 6 Software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). * = p<0.05, ** = p<0.01, *** = p<0.001.

Live imaging of Mhc1 mutants

The UAS-GCaMP5-attP40 construct was recombined in a Mhc1 mutant background localized on the second chromosome (Wells et al., 1996). Homozygous Mhc1 mutant embryos are paralyzed (Mogami and Hotta, 1981) but show generally normal presynaptic terminals (Yoshihara et al., 2000). The panneural elavC155-GAL4 was used to express UAS-GCaMP5 and UAS-myr-TdTomato. Embryos from 1hr egg lays were incubated at 25 °C for 20hr, then manually dechorionated and mounted on a coverslip in #700 halocarbon oil (Halocarbon Products Corp., River Edge, NJ). Live imaging of GCaMP5 in intact embryos was performed using 488nm excitation on a ZEISS LSM 880 airyscan using a 40× W, 1.3 N/A, or a Biorad 1024 confocal microscope using a 16× oil, 0.5 N/A or a 40× oil, 1.3 N/A objective. Images were taken at 512×512 or 1024×1024 resolution using no averaging function at different imaging rates as noted in the text. 3D reconstruction of the RFP-tagged glutamate receptors was performed using the Airy-scan deconvolution algorithm of ZEN (black edition). For the suppression of synaptic transmission, the UAS-TNT-E (Sweeney et al., 1995) construct inserted on the 2nd chromosome was recombined in a Mhc1 mutant background. Data was collected from motoneuron terminals on muscles 7 and 6 of the abdominal segment A3. Unless noted otherwise, images were taken every 5 seconds, based on the duration of peristaltic waves (Pereanu et al., 2007). Fluorescence values were calculated using ImageJ. The baseline fluorescence (F) was defined as the lowest mean gray value of the ROI after background subtraction for every single image stack.

Optogenetic stimulation of bPAC

The photoactivatable adenylyl cyclase of the bacterium Beggiatoa (bPAC) is a second generation light-gated adenylyl cyclase, with low activity in the dark. It increases its activity up to 300-fold after stimulation with 455 nm blue light (Stierl et al., 2011; Efetova et al., 2013; Stierl et al., 2014). In flies, the panneural expression of bPAC strongly elevates brain cAMP levels (Stierl et al., 2011). We used the panneural RU486-inducible elav-GS-GAL4 driver to target bPAC expression to all neurons in a rut1 mutant background. Embryos of the same genotype and from the same parental crosses were collected for a control group reared with no RU486 (non-induced expression), and were compared to the experimental group where RU486 was fed to parents for 24h prior to egg collection (induced expression). Eggs were collected for two hours at 25°C on 3.5 cm yeasted apple juice agar egg-lay plates, and incubated in the dark at 18°C until stage 16. Embryos from both groups were placed in a light-tight illuminating chamber containing three 455nm high power LEDs (Philips Luxeon royal blue) at a distance of ~3 mm away, with a net output power of 4mW, as determined by a Newport 818-SL detector (Newport Instr., Irvine, CA). Photostimulation was for 24h at 22°C, starting at embryonic stage 16 until early larval stage L1, using various illumination protocols. The induction of bPAC activity thus occurred during the previously determined phenocritical period for activity-dependent synaptic refinement at the NMJ (Jarecki and Keshishian, 1995; White et al., 2001). Four oscillatory photostimulation protocols were tested: (1) 8 s illumination followed by 80 s of darkness; (2) 15 s illumination followed by 150 s of darkness; (3) 30 s illumination followed by 300 s darkness; and (4) 30 s illumination followed by 600 s darkness. The net illumination for the first three protocols is the same (1:10 ratio of light:dark), and matches the parameters previously tested for induced Ca2+ influx to rescue the miswiring phenotype of the cac mutation (Carrillo et al., 2010). In the experiments with continuous light stimulation, embryos were constantly illuminated at a specific light intensity for 24h. After bPAC photostimulation, both groups were kept in the dark until late (wandering) third instar stage, when the larvae were dissected and immunolabeled with anti-HRP. All of the animals analyzed were hemizygous males of the genotype rut1/>; UAS-bPAC/+; elav-GS-GAL4/+.

Analysis of embryonic motor activity

Embryos were collected as described above, and mounted in halocarbon oil in groups of 2–4 on cover slips. Embryonic movements were recorded at 1 frame per second for 15 minutes at room temperature (21 °C). The number of complete forward and backward peristaltic waves was calculated over the interval or until hatching. Statistical difference was calculated by ANOVA using Prism 6 Software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA).

RESULTS

Low frequency calcium oscillations are observed at growth cones and embryonic motoneuron terminals

During embryonic development Drosophila motoneuron growth cones extend processes over multiple muscle fibers, and initially make inappropriate muscle fiber contacts (Halpern et al., 1991; Sink and Whitington, 1991; Chiba et al., 1993). The off-target contacts must be pruned away during an early critical period (late embryo to early 1st instar), otherwise they mature into functional ectopic synapses that remain throughout larval life (Jarecki and Keshishian, 1995). Silencing electrical activity in the motoneuron during this critical period increases the frequency of ectopic motoneuron contacts throughout the bodywall (Jarecki and Keshishian, 1995; White et al., 2001; Carrillo et al., 2010). Given the importance of oscillatory calcium (Ca2+) signaling in the embryo to remove ectopic contacts (Carrillo et al., 2010), we first examined whether periodic Ca2+ pulses are indeed present at embryonic growth cones and developing synapses.

We live-imaged intracellular Ca2+ signals in growth cones and developing NMJs of intact late stage embryos by expressing the genetically encoded Ca2+ indicator GCaMP5, using the panneural driver elav-GAL4 (Fig. 1 A–D). Although robust GCaMP5 fluorescence signals were detected in the embryo at developing NMJs (not shown), the movement caused by associated muscle contractions made imaging challenging. Movement was suppressed using a mutation of the myosin heavy chain (Mhc1) gene (Mogami and Hotta, 1981; Mogami et al., 1986; Yoshihara et al., 2000). The Mhc protein is required for contractile function in muscle fibers (Wells et al., 1996), and the mutation permits prolonged time-lapse imaging throughout embryonic development (Fig. 1). Mhc1 embryos also show evidence of normal muscle development, innervation, and motor system maturation, albeit with fictive motor activity (Fig. 1 A–H; movie 1–3). The frequency of Ca2+ pulses detected using GCaMP was similar to the frequency of muscle contractions due to endogenous motoneuron activity, as previously reported. Figure 1G shows a thirty minute record of Ca2+ signals from the developing NMJ of a single motoneuron, RP3, on the ventral longitudinal muscle fibers 7 and 6. Intracellular Ca2+ signals are observed in the form of low frequency oscillations (Movie 3), where increases in Ca2+ levels are spaced every 2–3 minutes, a pattern similar to that observed in recordings of muscle contraction frequency (Pereanu et al., 2007; Crisp et al., 2008).

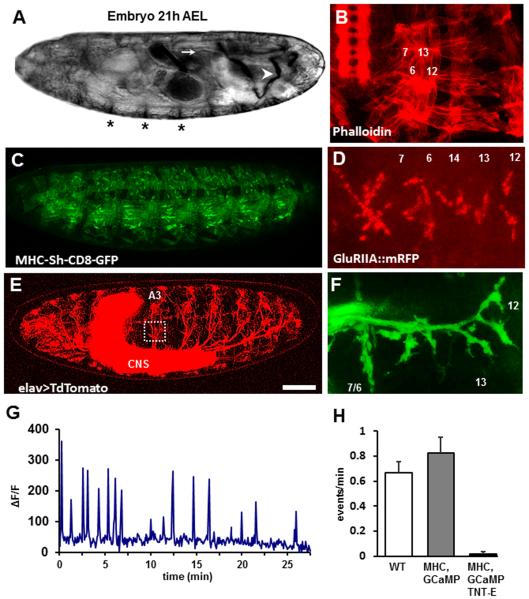

Figure 1. Low frequency calcium waves in motoneuron terminals require synaptic transmission during late embryogenesis.

A. A stage 17e Mhc1 embryo (21 hours after egg lay) shows the presence of morphological structures such as ventral dark denticles (asterisks), air-filled trachea (arrow), and uric acid crystals (arrowhead).

B. Bodywall musculature of a dissected Mhc1 embryo as revealed by phalloidin staining. Muscle fibers 7, 6, 13 and 12 are shown as orientation.

C–D. Localization of postsynaptic GFP-tagged potassium Shaker channels using the MHC-Sh-CD8-GFP construct (C) (Zito et al., 1997; Zito et al., 1999) and postsynaptic RFP-tagged glutamate receptor subunits IIA (D) (Rasse et al., 2005) in an intact Mhc1 embryo.

E. A stage 17e embryo (21 hours after egg lay (AEL)) expressing panneuronally the membrane-tagged red fluorescent protein Td-Tomato and the calcium indicator GCaMP5 in a homozygous Mhc1 mutant background. The central nervous system (CNS) is condensed, and all peripheral nerves and sensory cells are present in all segments. The white square depicts the area shown in B, where the SNb nerve innervates the internal ventral longitudinal muscles 7, 6, 12 and 13 in the abdominal segment A3.

F. Motoneuron terminals from the SNb nerve in segment A3 of a stage 17e embryo as revealed by the basal GCaMP5 fluorescence. Scale bar: 50μm for (A), 10μm for (B).

G. Example of oscillations of intracellular Ca2+ in boutons of a single motoneuron, RP3, innervating muscles 7 and 6 in segment A3 as measured by changes in GCaMP5 basal fluorescence (ΔF/F) imaged every 5 seconds. The pattern reveals short periods of activity followed by longer silent periods.

H. Frequency of activity events at the NMJ. For wildtype (white bar), the average frequency of peristaltic waves is shown. For the other two groups intracellular Ca2+ signals as measured by increases in GCaMP5 fluorescence (peaks) per minute recorded from a single motoneuron as described in C in embryos with a control genetic background (elav-GAL4, UAS-myr-TdTomato; Mhc1, UAS-GCaMP5. Gray bar) and in embryos expressing tetanus toxin in all neurons to block synaptic transmission (elav-GAL4, UAS-myr-TdTomato; Mhc1, UAS-GCamP5/ Mhc1, UAS-TNT-E. Black bar). Scale bar: 50μm for (A), (C), and (E); 30μm for (B); 7μm for (D) and (F).

Spontaneous wave-like Ca2+ activity propagates across the ganglion cells throughout the retina, activating both the superior colliculus and cortex of mice. This spontaneous activity is involved in synaptic refinement within the visual system (Wong, 1999; Ackman et al., 2012). We tested whether the patterned Ca2+ oscillations observed at the embryonic Drosophila NMJs were also due to spontaneous activity in the motoneurons, or were driven by a central pattern generator (CPG). We therefore blocked synaptic transmission throughout the CNS by expressing tetanus toxin (TNT-E) panneuronally to silence all network activity. Ca2+ oscillations at the NMJ were essentially abolished (Fig. 1D; movie 4), showing that they are not arising spontaneously in the growth cones or terminals. By contrast, we observed persistent and regular Ca2+ oscillations in a subset of embryonic sensory neurons, despite tetanus toxin expression and the suppression of movement (Movie 4). This suggests that for those sensory neurons there is an endogenous or pacemaker neural activity that results in oscillatory Ca2+ pulses.

The adenylyl cyclase rutabaga is required presynaptically for the withdrawal of off-target contacts

The Drosophila larval bodywall offers an anatomically stereotypic genetic model system for studying many aspects of neuronal connectivity (Fig. 2A,B) (Budnik, 1996). Errors in connectivity, including those involving activity-dependent refinement, are readily detected in the embryo and larva (Jarecki and Keshishian, 1995). A potential link between neural activity and downstream regulatory events involves Ca2+ entry through voltage-gated ion channels, where changes in intracellular Ca2+ would activate or inhibit various effectors (Flavell and Greenberg, 2008). In order to unravel the molecular mechanisms underlying activity-dependent synaptic refinement, we first examined the Ca2+-dependent adenylyl cyclase rutabaga (rut), which has multifaceted roles in the nervous system. These include the synaptic changes involved in long term memory (Dudai et al., 1976), growth cone motility (Kim and Wu, 1996; Berke and Wu, 2002), and in the size and complexity of the larval NMJ (Zhong et al., 1992; Lee et al., 2014). However, there have been no reports that mutations affecting cAMP levels affect either connectivity or synaptic refinement at the NMJ. We therefore examined whether mutations in rut would lead to miswired neuromuscular connections, as previously observed for manipulations affecting neuronal activity and Ca2+ influx.

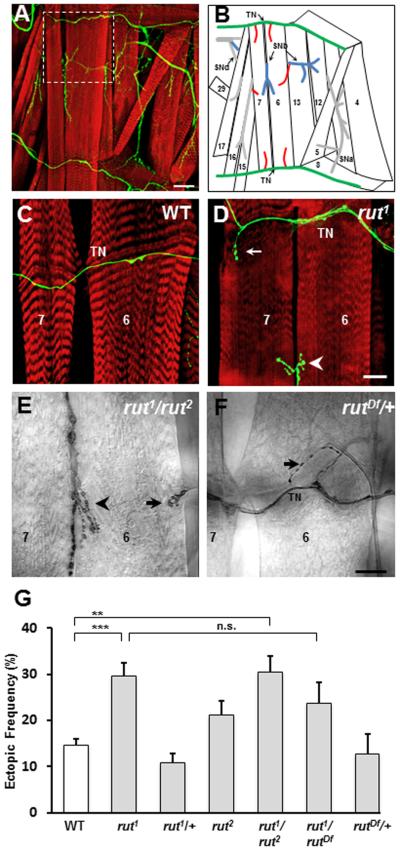

Figure 2. The Ca2+-dependent adenylyl cyclase is required for synaptic refinement.

A, B. (A) Musculature of the ventral portion of one abdominal hemisegment of a WT third instar larva with a corresponding schematic (B). In (A), the musculature is labeled with rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin (red), while nerves and neuromuscular junctions are labeled with anti-HRP antibodies (green). The white dashed square indicates the area that is shown in images of ectopic contacts in figures 2–6. In (B), the ectopic contacts (red) are shown in the typical locations in which they are observed. TN: Transverse Nerve (green). SNb: Segmental Nerve b (blue). SNd: Segmental Nerve d (gray). Scale bar: 50μm.

C,D. The transverse nerve (TN) of a wild type (WT) (C) and a rut1 mutant (D) third instar larva labeled as above. In (D) a type Ib ectopic contact is visible emerging from the transverse nerve onto muscle fiber 7 (arrow), which is distinct from the native innervation (arrowhead) of MF7 and 6. Scale bar: 20μm.

E, F. Ectopic contacts in the heteroallelic combination rut1/rut2 (E) and the heterozygous rut deficiency rutDf/+ (F). Arrowhead indicates the native innervation of MF 7 and 6. Scale bar: 20μm.

G. Frequency of ectopic contacts between WT and various rut alleles, calculated as the percentage of ectopic-containing hemisegments per animal, averaged over the number of animals (+ s.e.m.; n= 51, 33, 22, 19, 26, 13, and 12 animals, respectively).

The rut1 mutation leads to a strong reduction in basal adenylyl cyclase activity, and eliminates its Ca2+/calmodulin activation (Dudai and Zvi, 1984; Livingstone et al., 1984). We observed a significant increase in the frequency of ectopic contacts on bodywall muscles of rut1 mutants (Fig. 2D,G) as compared to wild type (WT, Fig. 2C,G; p< 0.001). Heterozygous rut1/+ mutants had no miswiring phenotype, and resembled the WT controls (Fig 2G). The weaker rut2 allele reduces basal adenylyl cyclase activity, but in contrast to rut1, retains its activation by Ca2+ (Feany, 1990). rut2 mutants showed no significant increase in the frequency of ectopic contacts (Fig. 2G). However, a significant phenotype was observed in the rut1/rut2 allelic combination (Fig. 2E,G). To test whether the observed phenotype was indeed due to mutations in the rut gene, rut1 mutants were crossed to flies bearing a chromosomal deficiency that spanned the entire rut locus (rutDf; Fig. 2H). The frequency of ectopic contacts observed in rut1/rutDf animals was comparable to rut1 mutants, showing that the synaptic refinement phenotype maps close to rut, and is unlikely due to a second site mutation.

We next examined whether the phenotype observed in rut mutants was due to the loss of function (LOF) of rut in neurons or in muscles. We expressed wild type Rut cDNA in either all neurons or all muscles in a rut1 mutant background, and tested for the suppression of the miswiring phenotype. Expression of Rut using the pan-muscular MHC-GAL4 driver showed no rescue of the rut1 phenotype (Fig. 3D). By contrast, expression of Rut using the RU486-inducible pan-neural elav-GSGAL4 driver significantly suppressed the rut1 ectopic phenotype when GAL4 activity was induced. A similar rescue was also observed using a second pan-neural driver, nsyb-GAL4 (17% ± 4%, n=17; versus rut1 30% ± 3%). We next tested whether knocking down Rut using RNAi in a tissue-specific manner would phenocopy the connectivity defects observed in rut1 mutants. As expected, panneural expression of Rut RNAi using elav-GAL4 (Fig 3C,E; p<0.01) or nsyb-GAL4 (21% ± 3%, n=24) significantly increased the frequency of ectopic contacts, whereas expression of Rut RNAi in all muscles using MHC-GAL4 (Fig. 3E) had no detectable effect.

Figure 3. The Ca2+-dependent adenylyl cyclase is required presynaptically for refinement.

A–C. The segmental border region of MF7 and 6 of a third instar larvae from WT (A), rut1 (B), and a larva expressing rut-RNAi in all neurons (C). Ectopic contacts in (B) and (C) are indicated by an arrow. The native innervation is indicated by an arrowhead. Scale bar: 40 μm for (A), 25μm for (B) and (C).

D. Frequency of ectopic-containing hemisegments per animal in the indicated genotypes (n=33, 13, 27, 45, and 20 animals, respectively). Rescue of the rut1 phenotype was scored in rut1/>hemizygous mutants bearing a copy of the UAS-rut construct in four different conditions: with no GAL4 driver present (rut1, UAS-rut control); with the panneural RU486 inducible elav-GeneSwitch-GAL4 (rut1, elavGS) in the uninduced (control) or induced condition; and with the panmuscle MHC-GAL4 driver.

E. Frequency of ectopic-containing hemisegments per animal + s.e.m. in larvae expressing GFP (as control), rut-RNAi, or UAS-rut either in all neurons (n= 12, 36, 29), or in all muscles (n= 19, 14, 14).

We next asked whether overexpression of Rut, which would presumably elevate cAMP production, would show effects opposite to those of Rut LOF, and possibly lead to a decreased ectopic frequency. Surprisingly, over-expression of Rut in neurons but not in muscles significantly increased the frequency of ectopic contacts (Fig. 3E). This suggests that experimentally forcing cAMP levels to remain high or low disrupts the normal withdrawal of off-target contacts. To further test this idea we examined a second enzyme known to regulate intracellular cAMP levels, the cAMP phosphodiesterase Dunce.

Mutations in the cAMP phosphodiesterase dunce lead to connectivity defects

The dunce (dnc) gene encodes a phosphodiesterase enzyme that degrades intracellular cAMP (Chen et al., 1986; Qiu et al., 1991), and dnc mutants have elevated intracellular cAMP levels (Byers et al., 1981; Davis and Kiger, 1981), and like rut mutations have previously been shown to influence the size and complexity of the larval NMJ (Zhong et al., 1992; Koon et al., 2011). We reasoned that dunce mutant animals would have defects similar to overexpressed Rut. Indeed, animals with dunce mutations that completely eliminate phosphodiesterase activity, such as dncM11 (Fig. 4A,C) and dncM14 (27.4% ± 3.2%, n=27), showed a significantly elevated ectopic frequency as compared to WT. The frequency of ectopic contacts was also elevated in the dnc alleles that only partially reduce phosphodiesterase activity, such as dnc2 (Fig. 4C) and dnc1 (25.2% ± 4.8%, n=11), as well as for heterozygotes of all dnc alleles tested. A high frequency of ectopic contacts was also observed in heterozygous animals for dncM11 and a deficiency spanning the dnc locus (dncM11/dncDf), confirming the genetic specificity of the dnc phenotype (Fig. 4C). The miswiring phenotype observed in dncM11 and dnc2 mutants was rescued by crossing them to rut1 mutants to generate double heterozygotes that showed WT levels of ectopics (Fig. 4C). This result suggests that rut and dnc may work in the same functional molecular pathway, presumably in regulating intracellular cAMP in motoneurons during synaptic development.

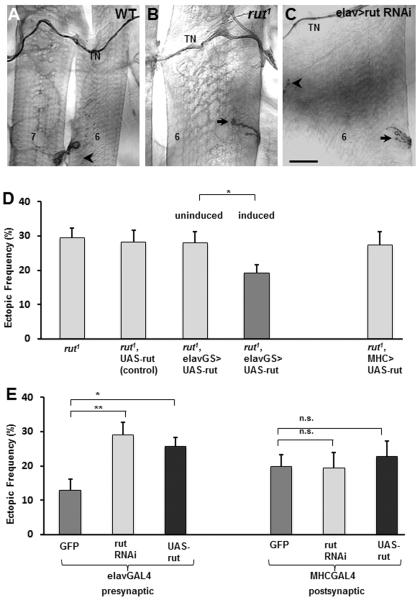

Figure 4. The cAMP phosphodiesterase is required presynaptically for synaptic refinement.

A,B. Ectopic contacts are observed in dncM11/> hemizygous mutants as well as in animals expressing UAS-dnc-RNAi in all neurons. Ectopic contacts are indicated by arrows. Arrowheads indicate the native innervations. Scale bar: 20μm.

C. Frequency of ectopic-containing hemisegments in the indicated genotypes (n= 51, 16, 14, 24, 14, 12, 15, 14). To test for statistical significance, all dnc groups were compared to WT.

D. Tissue-specific rescue of the dncM11 phenotype was assessed by scoring the indicated genetic conditions in a dncM11 heterozygous background (n= 14, 22, 20, 21, 15) in a similar way as described in Fig 3D.

E. Frequency of ectopic-containing hemisegments per animal in larvae expressing GFP (as control), dnc-RNAi, or UAS-dnc panneurally (n= 12, 28, 24), or in all muscles (n= 19, 15, 16).

We next tested whether the observed phenotype in dnc mutants was tissue specific. The connectivity phenotype observed in dncM11 mutants was rescued by introducing Dnc cDNA exclusively in neurons, whereas pan-muscular expression of Dnc showed no rescue (Fig. 4D). Similarly, expressing Dnc-RNAi panneurally using elav-GAL4 (Fig. 4B,E) or nsyb-GAL4 (28% ± 3%, n=8) phenocopied the miswiring defects observed in dnc mutants, whereas expression of dnc-RNAi in all muscles had no detectable effect (Fig. 4E). Overexpression of Dnc either in all neurons or all muscles did not lead to significant connectivity defects (Fig. 4E).

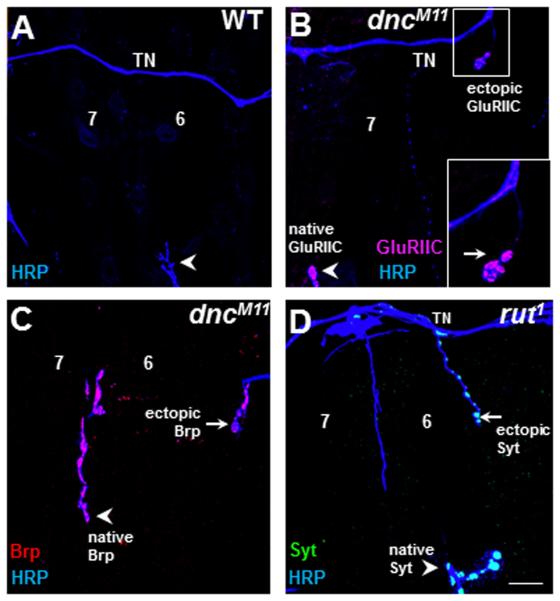

Ectopic contacts express key synaptic proteins

Several previous studies have shown that ectopic synapses are functional and express various synapse-specific markers (Chang and Keshishian, 1996; Carrillo et al., 2010). We also examined ectopic contacts for several key pre- and post-synaptic proteins that are typically found in functional NMJs (Fig. 5A–D). Larval NMJs fall into different groups according to their morphology and neurotransmitter type. These include glutamatergic type Ib and Is (Johansen et al., 1989), glutamate/octopamine type II (Monastirioti et al., 1995), and glutamate/peptidergic type III NMJs (Gorczyca et al., 1993). The presynaptic proteins Synaptotagmin (Syt) and Bruchpilot (Brp) were detected in over 90% of both type I and II ectopic contacts in both rut (90.2±1.8%, n=4) and dnc mutants (95.7±2.3%, n=3; Fig. 5C–D). In contrast to their seemingly normal presynaptic features, and consistent with an earlier study (Carrillo et al., 2010), postsynaptic molecular markers were less reliably observed. For example, robust GluRIIC staining was detected in only 20% of the type Ib ectopic contacts that arise in dnc mutants (Fig. 5B; 20.8±12.5%, n=3). These observations suggest that many ectopic contacts have aberrant postsynaptic features, or that some ectopic contacts are less stable and may start disassembling postsynaptically, before native synapses do, in preparation for metamorphosis.

Figure 5. Ectopic synaptic contacts express both pre and postsynaptic molecular markers.

A–D. The segmental border of MF 7 and 6 of third instar larvae stained with antibodies to HRP (blue) to reveal motoneuron endings from: wildtype WT (A), dncM11 (B,C) and rut1 mutants (D).

B. The postsynaptic dGluRIIC receptor subunit (magenta) is localized in a type Ib ectopic contact (arrow) emerging from the transverse nerve (TN) onto MF 7 in a dncM11/> hemizygous larva. The inset shows a higher-magnification image of the region shown at the top right.

C,D. Ectopic contacts observed in both cAMP mutants contained presynaptic markers such as the active-zone associated protein Bruchpilot (Brp, red) and the vesicular vSNARE protein Synaptotagmin (Syt, green). Ectopic contacts are indicated by arrows. Arrowheads indicate the native innervations. Scale bar: 20μm for A–D; 10μm for inset in B.

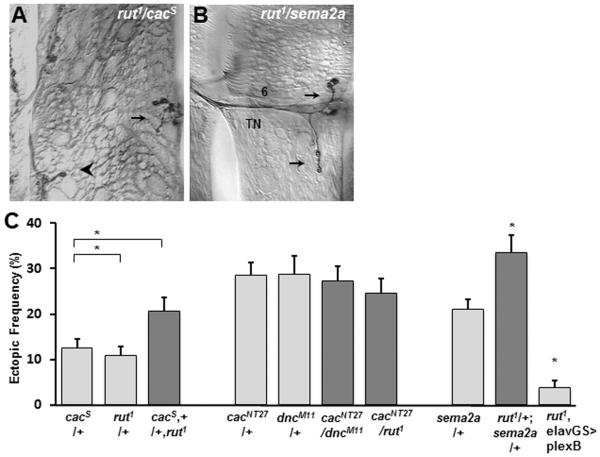

Intracellular cAMP levels function in the same molecular pathway downstream of neural activity and Ca2+ to regulate Sema2a-mediated chemorepulsion

The suppression of embryonic motoneuron activity, resulting in the cessation of peristaltic movement and paralysis, leads to extensive ectopic synaptic contacts (Jarecki and Keshishian, 1995; White et al., 2001; Carrillo et al., 2010). Therefore, we tested the possibility that the miswiring phenotypes of rut and dnc might also be due to aberrant peristaltic motor activity during embryonic development. For both the rut and dnc mutations we observed no aberrant motor activity, or any significant change in the frequency of peristaltic waves, as compared to wildtype embryos (rut1: 0.48 waves/min, n=9; dnc2: 0.46 waves/min, n=7; WT: 0.67 waves/min, n=11; p>0.05). In both mutations the peristaltic waves propagated in the same multisegmental fashion as wild type, suggesting that motor activity was not significantly impaired in either mutation. This is consistent with the hypothesis that cAMP signaling acts downstream of electrical activity and that the connectivity phenotype seen in rut or dnc is not due to reduced motoneuron excitability.

Elevated ectopic frequency has been observed in animals that bear mutations in the gene that codes for the Ca(v)2.1 channel cacophony (cac) (Carrillo et al., 2010). We therefore performed genetic interaction tests to determine whether rut participates in the same functional pathway as cac. We found that a genetic interaction exists between rut and the mild hypomorphic cacs allele, which shows an ectopic contact frequency similar to that of control larvae (Fig. 6A,C). One possibility is that in cac mutants, low Ca2+ levels lead to decreased activation of Rut, which causes cAMP levels to fall lower than normal. In order to increase cAMP levels in a cac mutant background, we crossed dncM11 mutant males that show elevated cAMP levels to the hypomorphic cacNT27 allele that shows increased ectopic frequency in cacNT27/+ heterozygotes, to generate cacNT27/dncM11 double heterozygotes. An elevated ectopic frequency was observed, that was no different than either dncM11/+ or cacNT27/+ heterozygotes. Thus, a genetic background that would elevate cAMP levels constitutively is not sufficient to rescue the cac mutant phenotype. Furthermore, in cacNT27/rut1 double heterozygotes the ectopic frequency was similar to cacNT27/+ heterozygotes and was not further increased (Fig. 6C). This observation argues that the effect may not be due to separate pathways yielding an additive effect. These results indicate that synaptic refinement requires functional cac, rut and dnc activity, and that chronic manipulations of these genes lead to connectivity defects.

Figure 6. Genetic interaction tests indicate that rut may function in a pathway that involves Ca2+ signaling and Sema2a-dependent chemorepulsion.

A–B. Ectopic contacts (arrows) on muscle fiber 6 in double heterozygotes cacs,+/ +,rut1 (A), and rut1/+; sema2a/+ (B).

C. Frequency of ectopic-containing hemisegments per animal in the indicated genotypes (n= 27, 22, 28, 16, 13, 16, 16, 34, 29, 18). Data from different groups were accordingly compared to rut1 heterozygous or homozygous animals.

The chemorepellant semaphorin Sema2a is also necessary for normal refinement of neuromuscular connections (Winberg et al., 1998; Carrillo et al., 2010). Therefore, we performed genetic interaction tests between rut and sema2a and observed an elevated ectopic frequency in the double heterozygotes rut1/+ sema2a/+ (Fig. 6B,C). To further test a relationship between rut and chemorepulsion, we asked whether the ectopic phenotype observed in rut1 homozygotes could be rescued by the panneural over-expression of the Sema2a receptor, PlexinB (Ayoob et al., 2006). Indeed, rut1 hemizygous animals over-expressing PlexinB significantly reduced the ectopic frequency (Fig. 6C).

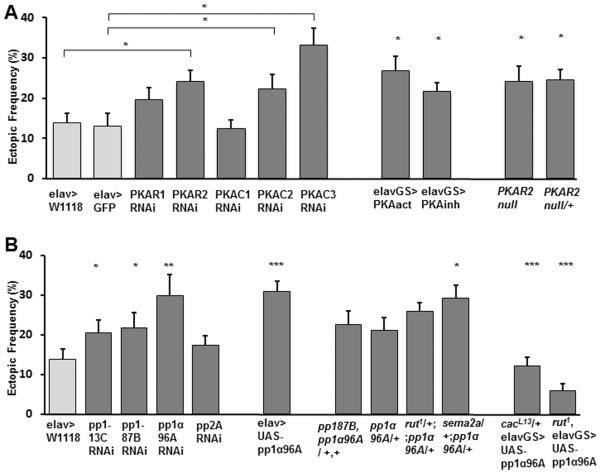

The molecular pathway underlying synaptic refinement includes Rut, PKA, and PP1 function

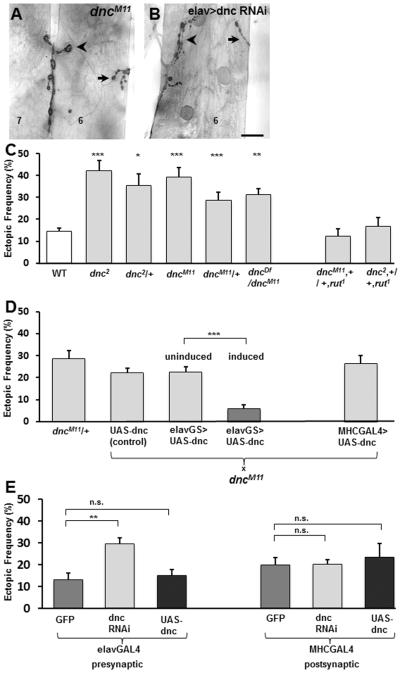

We next examined proteins downstream of cAMP signaling for their potential roles in synaptic refinement. A good candidate is the type II Protein Kinase A (PKA), a heterotetrameric holoenzyme activated by cAMP that is widely expressed in the Drosophila CNS (Kuo and Greengard, 1969; Müller, 1997). To test for a potential role of PKA in synaptic refinement, we expressed PKA-RNAi constructs panneurally to selectively knock down either of the two regulatory subunits (R1, R2) or the three catalytic subunits (C1, C2, C3). Intracellularly, the PKA complex consists of a dimer of two catalytic subunits and a second dimer of two regulatory subunits, which dissociates upon cAMP binding, activating the catalytic subunits. Therefore, increased PKA activity is observed by knocking down the regulatory subunits, whereas knock down of the catalytic subunits decreases PKA activity (Li et al., 1995). We observed a significant connectivity phenotype in knockdowns of either the R2, C2, or C3 subunits (Fig. 7A), which is consistent with our model suggesting that too high or too low cAMP levels both lead to connectivity defects. Knockdown of the R1 subunit yielded a slight but not significant increase in the frequency of ectopics, and the RNAi for the C1 subunit had no detectable effect (Fig. 7A). A similar miswiring defect was observed by both the panneural expression of a mutated mouse catalytic subunit that constitutively increases PKA activity (PKAact) or a mutant regulatory subunit that inhibits its activity (PKAinh; (Li et al., 1995; Davis et al., 1998)) (Fig. 7A). Using a second specific PKAR2-RNAi construct yielded similar defects (23% ± 3%, n=20) as well as the examination of PKA-R2null homozygous and heterozygous mutants (Fig. 7A). No significant change in the frequency of peristaltic waves was observed in PKA-R2null mutant embryos as compared to wild type (PKA LOF: 0.73 waves/min, n=6 vs. WT: 0.67 waves/min, n=11; p>0.05), suggesting that PKA activity likely acts downstream of activity for normal synaptic refinement.

Figure 7. Synaptic refinement likely requires protein kinase A and protein phosphatase 1 in a pathway that involves Sema2a-dependent chemorepulsion.

A. Frequency of ectopic-containing hemisegments in the indicated genotypes. RNAi constructs for the indicated subunits of PKA were panneurally expressed using the elav-GAL4 driver. To account for the different genetic backgrounds of the RNAi flies, control groups include elav-GAL4 flies crossed to either W1118 or UAS-GFP flies, and experimental lines were compared to their corresponding control for statistical significance. PKAact or PKAinh were panneurally expressed (n= 19, 12, 22, 21, 17, 17, 16, 14, 24). Data from pka RIIEP(2)2162 homozygous (n=18) and heterozygous mutants (n=10) were compared to WT.

B. Frequency of ectopic-containing hemisegments in larvae expressing RNAi for the indicated protein phosphatase genes using the elav-GAL4 driver. The control group includes elav-GAL4 flies crossed to W1118 (n= 19, 22, 16, 11, 22). Data from animals expressing pp1α96A panneuronally (n=18) were compared to the elav-GAL4/W1118 control group. Data from heterozygous animals bearing the single mutation pp1α96A2 or the double mutation pp1-87B87Bg-3 and pp1α96A2 were compared to WT (n=18, 22, 23, 30). Rescue of the miswiring phenotype in cacL13 heterozygotes and rut1 hemizygous by the panneural expression of pp1α96A was assessed by comparing the uninduced to the induced conditions (n=23, 23, for cacL13, and n=11, 15, for rut1, respectively).

The roles of CaMKII and chemorepulsion have been previously described to be required for normal refinement at the Drosophila NMJ (Carrillo et al., 2010). The protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) is a serine-threonine phosphatase that is known to interact with CaMKII and PKA to regulate chemorepulsion (Strack et al., 1997; Ceulemans and Bollen, 2004; Wen et al., 2004). Three fly genes code for the PP1 alpha subtype catalytic subunit, (Lin et al., 1999; Kirchner et al., 2007). Therefore, we tested for a potential role of PP1 in synaptic refinement by expressing RNAi constructs to selectively knock down the three catalytic PP1 genes, pp1-13C, pp1-87B, and pp1α96A (Kirchner et al., 2007). RNAi knockdown of each gene led to increased frequency of ectopic contacts, of which pp1α96A RNAi showed the highest frequency of ectopic contacts (Fig. 7B). A similar result was also observed by using a second specific pp1α96A RNAi construct (21% ± 3%, n=14). Pan-neural pp2A RNAi knock down did not show a detectable effect, suggesting that the miswiring phenotype is likely specific to reduced PP1 function, and not to knocking down any phosphatase. A miswiring phenotype was also observed in animals heterozygous for both null alleles pp1-8787Bg-3 and pp1α96A2, as well as in animals heterozygous for the null allele pp1α96A2 (Fig. 7B). Furthermore, over-expression of pp1α96A using elav-GAL4 also increases ectopic frequency (Fig. 7B). These results suggest an optimal range for cAMP levels as well as PKA and PP1 activity for normal refinement, where deviations in either direction lead to connectivity defects.

We next tested whether PP1 acts in the same signaling cascade as cAMP and chemorepulsion for synaptic refinement using genetic interaction tests. Crossing pp1α96A mutants to rut or sema2a mutants increases ectopic frequency (Fig. 7B). Interestingly, the elevated ectopic frequency observed in cacL13 heterozygotes and in rut1 homozygous could also be rescued by over-expressing pp1α96A (Fig. 7B), suggesting that PP1 function is decreased in these genetic backgrounds. These results indicate that cac, rut, pp1 and sema2a are likely to function within the same functional genetic pathway. The results are consistent with a model where presynaptic Ca2+ signaling regulates cAMP, which acts through PKA and PP1 activity, to modulate the motoneuron's response to muscle-derived chemorepulsion.

cAMP levels are required to be dynamically maintained in an optimal range in embryonic neurons to suppress ectopic contacts

Oscillatory electrical activity at the embryonic NMJ is revealed by low frequency periodic muscle contractions throughout the bodywall musculature (Pereanu et al., 2007; Crisp et al., 2008). This results in an oscillation in Ca2+ levels in all developing motoneuron synapses, as revealed using transgenic Ca2+ indicators imaged in vivo in the embryo (Fig. 1). This raises the possibility that cAMP levels may be regulated in response to dynamically changing levels of presynaptic Ca2+. One possibility is that presynaptic cAMP levels oscillate with a pattern similar to that for Ca2+ and the resulting dynamic changes in cAMP could be necessary for regulating the withdrawal of off-target contacts. Alternatively, the Ca2+ oscillations may be necessary for the homeostatic maintenance of cAMP levels within a specific range. To test whether cAMP levels must oscillate, we expressed a bacterial photoactivated adenylyl cyclase (bPAC) to optogenetically manipulate presynaptic cAMP levels in vivo during the critical embryonic period for synaptic refinement. bPAC is an adenylyl cyclase from the bacterium Beggiatoa that shows low cyclase activity in darkness, but increases its activity 300-fold in the presence of blue light (455 nm; Stierl et al., 2011; Efetova et al., 2013; Stierl et al., 2014). First, we tested whether baseline bPAC activity in the dark was sufficient to rescue the ectopic phenotype observed in rut1 homozygotes. We used the GeneSwitch GAL4 system to compare embryos with identical genotypes. In constant darkness, elevated ectopic frequency is observed in control animals without induced expression as well as in animals that were fed RU486 for 24h (Fig. 8C). Upon expressing bPAC panneurally in rut1 mutants, we used four different light activation protocols (Fig. 8A) to examine whether cAMP levels are required to oscillate with specific patterns for normal synaptic refinement.

Figure 8. An optimal range of dynamic cAMP levels downstream of Ca signaling are required for synaptic refinement during embryonic development.

A. The photoactivatable adenylyl cyclase bPAC was used for conditional light-dependent production of cAMP, expressed panneurally in rut1 mutants. Light intensity in mW/cm2 at the stimulation chamber is shown for two activation protocols: 15 s light followed by 150 s dark (upper trace), or 30 s light followed by 300 s dark (lower trace). Embryos were stimulated with cycles of light activation followed by periods of dark from stage 16 to early L1. Larvae were then allowed to develop in darkness until third instar.

B. Frequency of ectopic-containing hemisegments in rut1/>hemizygous larvae expressing bPAC using the panneural elav-GSGAL4 driver in the uninduced (control, light gray) and induced (after parental RU486 feeding, dark gray) condition (n= 45, 47, 41, 35, 29, 20, 12, 16). Embryos for both conditions had the same genotype: they were collected from the same parents with the only difference of RU486 induction of bPAC expression. Embryos were stimulated with a 1:10 duty cycle (either with 8 s light followed by 80 s dark, or with 15 s light followed by 150 s darkness, or with 30 s light followed by 300s dark) or with a 1:20 duty cycle (30 s light followed by 600 s dark).

C. Frequency of ectopic-containing hemisegments in rut1/>hemizygous larvae expressing bPAC. Left bars show data from embryos that were stimulated using continuous light with different intensities (0, 0.1, 0.5, 1, and 4.5 mW/cm2; n=30, 23, 16, 17, 31) following 24h of parental RU486 feeding. Right bars show data from embryos that were kept in constant darkness following the uninduced (control, light gray; n=31) and induced (after parental RU486 feeding, dark gray) condition during different RU486 feeding periods (24, 48, or 96 hours; n=30, 16, 23).

D. Frequency of ectopic-containing hemisegments in the indicated genotypes. Rescue of the rut1 phenotype was scored in rut1/>hemizygous larvae expressing cDNA of the voltage-gated Ca(v)2.1 Ca2+ channel Cacophony or the temperature sensitive Ca2+ permeable channel TrpA1 using the elav-GSGAL4 driver (n=33, 24, 14). Activation of TrpA1 occurred by shifting the temperature during a 1:10 duty cycle of 15 s at 28 °C followed by 150 s at 18 °C. Similarly, rescue of the cacNT27 phenotype was scored in cacNT27/>hemizygous larvae expressing a copy of UAS-rut or UAS-bPAC using the elav-GSGAL4 driver (n=12, 8, 8). bPAC was activated by a pattern of 15s light followed by 150s darkness as described in B.

The suppression of the rut1 ectopic phenotype was observed with periodic bPAC activation protocols that resembled the normal pattern of embryonic motor activity (a cycle of 15s light activation followed by a 150s darkness, 15:150 protocol; fig. 8A,B). By contrast, embryos that were stimulated with a cycle of 8s of light activation followed by a 80s dark interval (8:80 protocol), or of 30s of light activation followed by a 300s dark interval (30:300 protocol) both failed to suppress ectopic contacts (Fig. 8B). Note that the total time that bPAC was activated using the 8:80 and 30:300 protocol is identical to that of a 15:150 protocol. We also did not observe a rescue of the rut phenotype with a 30:600 protocol. Therefore, inducing adenylyl cyclase activity in embryonic and early larval neurons, at a low frequency that resembles the WT pattern of electrical activity, is sufficient to suppress the miswiring seen with loss of function of rut.

Although these experiments show that oscillations of cAMP at a specific frequency and pattern are sufficient to rescue miswiring, we next asked whether oscillations are also necessary. To test this, we performed two sets of experiments. First, we used constant light to stimulate embryos from parents that were fed RU486 for 24h, using different light intensities that would lead to different levels of constant bPAC activation. A rescue of the miswiring phenotype was observed only in animals that were continuously stimulated using moderate light intensity (0.5 mW/cm2; fig. 8C). By contrast, embryos stimulated using continuous light with low or high light intensities (0.1, 1 and 4 mW/cm2, respectively) showed increased ectopic frequency (Fig. 8C). We also tested whether the level of induced bPAC expression would lead to different degrees of baseline cyclase activity in darkness, and consequently, different degrees of rescue. Indeed, animals that were exposed to RU486 for prolonged time periods, such as 48h and 96h, and maintained in constant darkness, showed a significant decrease in the frequency of ectopic contacts. These results suggest that oscillatory cyclase activity is sufficient but not necessary for synaptic refinement.

Finally, we performed genetic tests to determine whether rut is positioned downstream of cac and thus Ca2+ influx. If so, then increasing Ca2+ influx in a rut1 mutant background would not be expected to rescue the rut1 phenotype. By contrast, increasing cAMP levels in a cac mutant would suppress the cac phenotype. First, we expressed Cac or the temperature sensitive Ca2+ permeable channel TrpA1 (Hamada et al., 2008; Pulver et al., 2009) using elav-GSGAL4 in hemizygous rut1animals. Expression of Cac only led to a slight, but significant decrease of the rut1 phenotype (Fig. 8D), whereas expression of TrpA1 showed no suppression of the phenotype (Fig. 8D), even though we used the same activation protocol of TrpA1 (15s ON: 150s OFF) known to rescue connectivity defects in cac mutants (Fig. 8D; Carrillo et al., 2010). By contrast, a complete rescue of the miswiring phenotype occurred after expression of Rut using elav-GSGAL4 in cacNT27 hemizygous mutants (Fig. 8D). Similarly, the miswiring phenotype was rescued by expression of bPAC followed by a 15s ON: 150s OFF activating light protocol or in constant darkness after 96h RU486 exposure (Fig. 8D). A similar rescue was observed in cacL13 heterozygous animals (cacL13/w,elavGS, 29.4% % ± 4.0%, n=17; cacL13/w;elavGS>rut, 13.3% ± 5.5%, n=8; cacL13/w; elavGS>bPAC dark, 5.0% ± 1.9%, n=8).

DISCUSSION

The pathway for activity-dependent refinement involves cAMP signaling

In Drosophila, motoneuron activity is required for the refinement of embryonic and larval bodywall NMJs (Jarecki and Keshishian, 1995; White et al., 2001; Carrillo et al., 2010). Our results support a model in which patterned electrical activity in motoneurons controls intracellular Ca2+-levels in developing synapses, to regulate the embryonic neuron's response to chemorepulsion (Carrillo et al., 2010). Withdrawal of off-target contacts depends on Sema2a, a chemorepellant molecule secreted by muscle that binds to PlexinB, the corresponding motoneuron receptor (Matthes et al., 1995; Winberg et al., 1998; Hu et al., 2001; Ayoob et al., 2006).

A role for cAMP at the developing NMJ was first demonstrated by Zhong et al. (1992), showing that size and complexity of the mature larval NMJ was increased in dunce mutants. By contrast, the results described in this study point to a distinct and earlier embryonic role for cyclic nucleotide signaling in the regulation of the developing synapse's response to muscle derived chemorepulsion. Central to this effect is the role of activity-dependent Ca2+-entry into the developing NMJ.

Our results show that pan-neural overexpression of Dnc did not increase ectopic frequency, although this manipulation should resemble decreased cAMP levels as in rut mutants. Overexpression of Dnc has been previously reported to only partially reproduce rut phenotypes, as in a study examining the formation of satellite synaptic boutons at the larval NMJ (Lee and Wu, 2010). One possibility involves homeostatic mechanisms by other genes, such as rut or PKA, to compensate for the phosphodiesterase gain of function. Compensatory changes in expression or activity levels of identified molecular components in different genetic backgrounds should be investigated in future studies. Our results are consistent with previous studies showing that similar phenotypes are observed in rut and dnc mutants caused by their opposite defects in cAMP synthesis or hydrolysis, which range from poor learning performance (Tully and Quinn, 1985), defects in growth cone behavior (Kim and Wu, 1996), and synaptic function and growth (Renger et al., 1999; Lee and Wu, 2010).

Our data indicate that PlexinB function and/or its downstream signaling pathway is likely regulated by Ca2+-entry through Cacophony, the Ca(v)2.1 voltage-gated channel, and by multiple Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent downstream targets, such as the adenylyl cyclase Rutabaga and CaMKII (Carrillo et al., 2010). Extensive molecular interactions exist among key signaling molecules downstream of the Ca2+-oscillations. The rise in cAMP levels due to the Ca2+-dependent activation of adenylyl cyclase would be countered by the cAMP phosphodiesterase, Dunce (Davis and Kiger, 1981; Dudai and Zvi, 1984). Cyclic AMP would also activate Protein Kinase A (PKA). PKA, in conjunction with Calcineurin, would activate Protein Phosphatase 1 (PP1) to dephosphorylate CaMKII, reducing its activity (Shields et al., 1985; Blitzer et al., 1998; Oliver and Shenolikar, 1998; Wen et al., 2004). Whether the activity or levels of these downstream signaling molecules also oscillate, phase-locked to the Ca2+ oscillation, remains to be determined.

A role for cAMP signaling in synaptic refinement observed here is consistent with in vitro studies of cyclic nucleotides and chemotropic signaling (Song et al., 1997; Song et al., 1998; Hopker et al., 1999; Chalasani et al., 2003; Nicol et al., 2011). For example, in the visual system ephrin-A-dependent retraction of cultured retinal axons requires AC1, the Ca2+-stimulated adenylyl cyclase (Nicol et al., 2006). Similarly, the calmodulin-activated adenylyl cyclase ADCY8 regulates slit-dependent repulsion in zebrafish retinal axons (Xu et al., 2010). While the focus of this study has been on cAMP and its downstream signaling, a balance between cAMP and cGMP levels is often a factor governing whether a response is chemoattractive or chemorepulsive in vitro (Song et al., 1997; Song et al., 1998; Nishiyama et al., 2003). A role for cGMP in activity-dependent synaptic refinement at the Drosophila NMJ remains untested.

Previous in vitro studies and mathematical models show that growth cones often display repulsive behavior when Ca2+ and cAMP levels are low, due in part to the roles of PKA and PP1 (Ming et al., 1997; Wen et al., 2004; Forbes et al., 2012). We have observed in vivo an increased frequency of ectopic synapses following genetic methods that decrease neural activity, Ca2+ channel function and cAMP levels, as well as PKA and PP1 function. However, we also observed similar miswiring phenotypes with manipulations that elevate cAMP. These results are consistent with a model where intracellular Ca2+-oscillations may serve to keep cAMP levels and the activity of the downstream effectors rising and falling within physiologically optimal ranges.

In other systems cAMP may also be a factor in modulating Ca2+ activity, through its influence on Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR) from internal stores (Gomez and Zheng, 2006; Zheng and Poo, 2007). Accordingly, Nicol et al. (2011) reported that the amplitude of Ca2+ transients in growth cones is modulated by cAMP, through the cAMP-dependent activation of the ryanodine receptor (Ooashi et al., 2005). We observed that expression of Rut or bPAC, to elevate cAMP in cac mutants led to a full rescue of the miswiring phenotype. Expression of TrpA1 to introduce a constitutive Ca2+-flux into the neurons, failed to rescue the rut1 phenotype. We observed a small but significant reduction of the phenotype when Cac was overexpressed. One possibility for this difference may be that additional Ca2+-dependent molecules in the pathway are distinctly activated by the overexpression of Cac than by the restricted, episodic activation of TrpA1. Although secondary effects on neural activity cannot be completely ruled out, our genetic results thus indicate that the Ca2+-dependent adenylyl cyclase rut may act downstream of the Ca2+-channel cac.

The major downstream targets of cAMP include PKA (Brandon et al., 1997), “exchange proteins directly activated by cAMP” (EPAC; Gloerich and Bos, 2010), or cAMP-gated ion channels (CNGs; Kaupp and Seifert, 2002) each with distinct activation kinetics or subcellular compartmentalization (Beene and Scott, 2007; Ponsioen et al., 2009). Pharmacological studies of cultured rat cells show that cAMP mediates growth cone attraction or repulsion, by independently activating either PKA or EPAC (Murray et al., 2009). PKA antagonizes chemotropic axonal repulsion in several systems, and its inhibition promotes the withdrawal of processes (Dontchev and Letourneau, 2002; Chalasani et al., 2003; Parra and Zou, 2010).

In Drosophila embryos PKA regulates interaxonal repulsion or defasciculation, mediated by the interaction of membrane-bound Sema1a and its receptor PlexinA (Ayoob et al., 2004). The interaction between cyclic nucleotide signaling and Plexins depends on the A kinase anchoring protein (AKAP) nervy (Terman and Kolodkin, 2004). Nervy binds and anchors PKA, and serves to reduce PlexinA chemorepulsion. In our study we find that PKA is required for synapse withdrawal, suggesting that it enhances chemorepulsion when it remains within a specific range of levels. Whether a link exists between AKAPs, PKA, and PlexinB to enhance Sema2a-dependent repulsion at the developing NMJ remains an open question.

A proposed link between cAMP signaling, CaMKII, and synaptic pruning

Our results point to a significant role for cyclic nucleotide-mediated signaling in the motoneuron's response to the retrograde chemorepellant Sema2a, leading to the pruning of off-target synaptic contacts. In a previous study (Carrillo et al, 2010), it was found that CaMKII is required for this form of refinement, where its inhibition resulted in the appearance of excess ectopic synapses. In that study and the present one the relevant molecular systems are regulated by Ca2+, entering the cell through the Cac channel. We hypothesize that the two signaling systems may be linked through the actions of cAMP and the protein phosphatase PP1.

PP1 has previously been shown to serve as a molecular link between cAMP signaling and CaMKII to promote growth cone repulsion (Wen et al., 2004; Forbes et al., 2012). In mammalian systems, PP1 directly dephosphorylates CaMKII to reduce its activity (Shields et al., 1985). In Drosophila, the mechanism underlying PP1-regulation and its modulation of chemorepulsion has not been explored in detail. Our results provide some insight as to how PP1 may be regulated at the developing synapse. Elevating PP1-expression in embryonic neurons rescues the miswiring phenotype due to the loss of function of either the Ca2+ channel Cac, or the Ca-activated adenylyl cyclase Rut (Fig. 7). This suggests that PP1 acts downstream of Ca2+ and cAMP signaling, and that its function is depressed when levels of either Ca2+ or cAMP are low. Driving PP1 activity well above wildtype levels also has deleterious effects, leading to an increased frequency of ectopic connections (Fig. 7). Assuming that PP1 suppresses CaMKII activity, then this result is consistent with the previous observation that the inhibition of CaMKII results in a miswiring phenotype (Carrillo et al., 2010). PP1 activity is also known to be regulated by the Ca2+-dependent phosphatase Calcineurin (Klee et al., 1998; Oliver and Shenolikar, 1998). Consistent with this, we have recently observed that Calcineurin loss of function mutations similarly disrupt synaptic refinement (Vonhoff and Keshishian, unpublished observations).

Finally, there is additional evidence from the literature linking Ca2+ and cAMP signaling with PP1 function. In mammalian neurons, PP1 activity is regulated by protein Inhibitor 1 (I1+), a phosphoprotein that is phosphorylated by PKA, and dephosphorylated by Calcineurin (Blitzer et al., 1998; Oliver and Shenolikar, 1998). While I1+ has no identified fly homologue (Ceulemans et al., 2002; Bennett et al., 2006), known Drosophila proteins that inhibit PP1 include Inhibitor-2 (I-2Dm) and Nuclear Inhibitor of PP1c (NIPP1Dm) (Bennett et al., 2003). Whether any of these molecules are regulated in a Ca2+ or cAMP dependent manner, like I1+, or whether they play a role in activity-dependent refinement, remains to be tested.

The role of oscillatory activity in synaptic refinement

Neural activity plays a fundamental role during early critical periods for network assembly, as it regulates a variety of cellular events, such as dendritic development (Cline, 2001; Vonhoff et al., 2013), synaptic development (Kelsch et al., 2009), synaptic scaling (Desai et al., 2002), and the proper refinement of synaptic connections (Wiesel and Hubel, 1963; Hubel and Wiesel, 1970; Kakizawa et al., 2000). In many cases, the necessary activity is oscillatory.

An intriguing hypothesis is that synaptic refinement at the NMJ involves the dynamic regulation of chemotropic signaling, orchestrated by Ca2+ rising and falling within a specific range during neuromuscular exploration and withdrawal in the embryo. By episodically modulating the response of the motoneuron to muscle-derived Sema2a in an oscillatory fashion, the developing contacts could preferentially explore membrane surfaces when Ca2+-levels are low, and then withdraw the less firmly-associated contacts when sensitivity to the Sema2a chemorepellant rises, during the bouts of Ca2+-entry.

In vitro studies indicate that intracellular cAMP levels also need to oscillate to modulate growth cone responses to ephrin-A5 (Nicol et al., 2007) and to in turn induce filopodial Ca2+-transients (Nicol et al., 2011). Using the photoactivated adenylyl cyclase bPAC we were able to suppress the miswiring phenotype observed in rut1 mutants when the cyclase was optogenetically oscillated at a frequency and pattern comparable to that for motor activity in the embryo. No rescue of the rut1 phenotype was observed when bPAC was activated using slow or fast activation protocols, or continuous light using either low or high intensities. However, we did find that a reduction in ectopic contacts occurred when bPAC-illumination was adjusted to a specific intermediate level. This suggests that the neuron must maintain an optimal range of cAMP levels for normal synaptic refinement, where levels that fall either too low or too high lead to miswiring defects.

Another possible role for Ca2+-oscillation is to keep levels of cAMP within a physiologically appropriate range. Thus, the episodic rise and fall of Ca2+ that regulates cyclase activity, would have a homeostatic function, to maintain cAMP levels within a specific range of values. These observations provide an impetus to determine whether the other downstream Ca2+-dependent signaling systems also oscillate, in a phase locked fashion to the Ca2+-oscillation, and whether oscillations are both necessary and sufficient for chemotropic signal processing.

Supplementary Material

Time lapse of an intact stage 17e embryo expressing UAS-GCaMP5 panneurally in a Mhc1 mutant background. Images were taken every 15 sec for 30 min using a 16x objective. Image size is 650 μm. Movie played back at 8 frames/s (sped up 120x). Anterior is to the top, ventral is to the right.

Three dimensional reconstruction of postsynaptic clusters of RFP-tagged glutamate receptor IIA subunits in an intact Mhc1 embryo. Shown are NMJs at muscle fibers 7 and 6 (far left), 14, 13, and 12 (far right).

Live imaging of Ca2+ signals at the motor terminals on the ventral longitudinal muscles 16, 15, 7, 6, 14, 13, and 12 (far right) of a A3 hemisegment in a stage 17e embryo expressing panneurally UAS-GCaMP5 in a Mhc1 mutant background. Images were taken every 5 sec for 33 min. Movie played back at 20 frames/s (sped up 10x). Anterior is to the top, ventral is to the left.

Live imaging of Ca2+ signals at the motor terminals in abdominal hemisegments A3–A4 in a stage 17e embryo expressing panneurally UAS-GCaMP5 and UAS-TNT-E in a Mhc1 mutant background. Whereas GCaMP flashes at the NMJs are virtually abolished, flashes are periodically observed in the cell body of the LBD neuron. Anterior is to the top, ventral is to the left. Images were taken every 5 sec for 33 min. Movie played back at 20 frames/s (sped up 10x).

Acknowledgments

We thank Brett Berke, William Leiserson, Damon Clark, and John Carlson for their advice and comments on the manuscript, and Douglas Olsen for his preliminary analysis of the rutabaga and dunce mutations. The research was supported by grants to HK from the NIH (5R01NS031651 and 1R21NS053807). Imaging data was partially collected at the MBL in Woods Hole, MA supported by the Grass Foundation Fellowship to FV.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions: FV and HK designed research and wrote the paper; FV performed research and analyzed data.

References

- Ackman JB, Burbridge TJ, Crair MC. Retinal waves coordinate patterned activity throughout the developing visual system. Nature. 2012;490:219–225. doi: 10.1038/nature11529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayoob JC, Terman JR, Kolodkin AL. Drosophila Plexin B is a Sema-2a receptor required for axon guidance. Development. 2006;133:2125–2135. doi: 10.1242/dev.02380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayoob JC, Yu HH, Terman JR, Kolodkin AL. The Drosophila receptor guanylyl cyclase Gyc76C is required for semaphorin-1a-plexin A-mediated axonal repulsion. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6639–6649. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1104-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beene DL, Scott JD. A-kinase anchoring proteins take shape. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2007;19:192–198. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellen H, Kiger J., Jr Maternal effects of general and regional specificity on embryos of Drosophila melanogaster caused by dunce and rutabaga mutant combinations. Roux's archives of developmental biology. 1988;197:258–268. doi: 10.1007/BF00380019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellen HJ, Gregory BK, Olsson CL, Kiger JA., Jr Two Drosophila learning mutants, dunce and rutabaga, provide evidence of a maternal role for cAMP on embryogenesis. Developmental Biology. 1987;121:432–444. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(87)90180-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett D, Lyulcheva E, Alphey L. Towards a Comprehensive Analysis of the Protein Phosphatase 1 Interactome in Drosophila. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2006;364:196–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.08.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett D, Szöőr B, Gross S, Vereshchagina N, Alphey L. Ectopic Expression of Inhibitors of Protein Phosphatase Type 1 (PP1) Can Be Used to Analyze Roles of PP1 in Drosophila Development. Genetics. 2003;164:235–245. doi: 10.1093/genetics/164.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berke B, Wittnam J, McNeill E, Van Vactor DL, Keshishian H. Retrograde BMP signaling at the synapse: a permissive signal for synapse maturation and activity-dependent plasticity. J Neurosci. 2013;33:17937–17950. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6075-11.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berke B, Wu C-F. Regional Calcium Regulation within CulturedDrosophila Neurons: Effects of Altered cAMP Metabolism by the Learning Mutations dunce andrutabaga. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2002;22:4437–4447. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-11-04437.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blitzer RD, Connor JH, Brown GP, Wong T, Shenolikar S, Iyengar R, Landau EM. Gating of CaMKII by cAMP-Regulated Protein Phosphatase Activity During LTP. Science. 1998;280:1940–1943. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5371.1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon EP, Idzerda RL, McKnight GS. PKA isoforms, neural pathways, and behaviour: making the connection. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1997;7:397–403. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(97)80069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budnik V. Synapse maturation and structural plasticity at Drosophila neuromuscular junctions. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1996;6:858–867. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(96)80038-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byers D, Davis RL, Kiger JA., Jr Defect in cAMP phosphodiesterase due to the dunce mutation of learning in Drosophila melanogaster. Nature. 1981;289:79–81. doi: 10.1038/289079a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo RA, Olsen DP, Yoon KS, Keshishian H. Presynaptic activity and CaMKII modulate retrograde semaphorin signaling and synaptic refinement. Neuron. 2010;68:32–44. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceulemans H, Bollen M. Functional diversity of protein phosphatase-1, a cellular economizer and reset button. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:1–39. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceulemans H, Stalmans W, Bollen M. Regulator-driven functional diversification of protein phosphatase-1 in eukaryotic evolution. Bioessays. 2002;24:371–381. doi: 10.1002/bies.10069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalasani SH, Sabelko KA, Sunshine MJ, Littman DR, Raper JA. A chemokine, SDF-1, reduces the effectiveness of multiple axonal repellents and is required for normal axon pathfinding. J Neurosci. 2003;23:1360–1371. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-04-01360.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang T, Keshishian H. Laser Ablation of Drosophila Embryonic Motoneurons Causes Ectopic Innervation of Target Muscle Fibers. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16:5715–5726. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-18-05715.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CN, Denome S, Davis RL. Molecular analysis of cDNA clones and the corresponding genomic coding sequences of the Drosophila dunce+ gene, the structural gene for cAMP phosphodiesterase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:9313–9317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.24.9313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung US, Shayan AJ, Boulianne GL, Atwood HL. Drosophila larval neuromuscular junction's responses to reduction of cAMP in the nervous system. Journal of Neurobiology. 1999;40:1–13. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(199907)40:1<1::aid-neu1>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiba A, Hing H, Cash S, Keshishian H. Growth cone choices of Drosophila motoneurons in response to muscle fiber mismatch. J Neurosci. 1993;13:714–732. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-02-00714.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cline HT. Dendritic arbor development and synaptogenesis. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2001;11:118–126. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00182-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisp S, Evers JF, Fiala A, Bate M. The development of motor coordination in Drosophila embryos. Development. 2008;135:3707–3717. doi: 10.1242/dev.026773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis GW, DiAntonio A, Petersen SA, Goodman CS. Postsynaptic PKA controls quantal size and reveals a retrograde signal that regulates presynaptic transmitter release in Drosophila. Neuron. 1998;20:305–315. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80458-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RL, Kiger JA. Dunce mutants of Drosophila melanogaster: mutants defective in the cyclic AMP phosphodiesterase enzyme system. The Journal of Cell Biology. 1981;90:101–107. doi: 10.1083/jcb.90.1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai NS, Cudmore RH, Nelson SB, Turrigiano GG. Critical periods for experience-dependent synaptic scaling in visual cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:783–789. doi: 10.1038/nn878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dontchev VD, Letourneau PC. Nerve growth factor and semaphorin 3A signaling pathways interact in regulating sensory neuronal growth cone motility. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6659–6669. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06659.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudai Y, Jan YN, Byers D, Quinn WG, Benzer S. dunce, a mutant of Drosophila deficient in learning. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1976;73:1684–1688. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.5.1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudai Y, Zvi S. Adenylate cyclase in the Drosophila memory mutant rutabaga displays an altered Ca2+ sensitivity. Neuroscience Letters. 1984;47:119–124. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(84)90416-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efetova M, Petereit L, Rosiewicz K, Overend G, Haussig F, Hovemann BT, Cabrero P, Dow JAT, Schwarzel M. Separate roles of PKA and EPAC in renal function unraveled by the optogenetic control of cAMP levels in vivo. Journal of Cell Science. 2013;126:778–788. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39:175–191. doi: 10.3758/bf03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feany MB. Rescue of the learning defect in dunce, a Drosophila learning mutant, by an allele of rutabaga, a second learning mutant. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1990;87:2795–2799. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.7.2795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flavell SW, Greenberg ME. Signaling Mechanisms Linking Neuronal Activity to Gene Expression and Plasticity of the Nervous System. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2008;31:563–590. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.31.060407.125631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes EM, Thompson AW, Yuan J, Goodhill GJ. Calcium and cAMP levels interact to determine attraction versus repulsion in axon guidance. Neuron. 2012;74:490–503. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloerich M, Bos JL. Epac: defining a new mechanism for cAMP action. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010;50:355–375. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.010909.105714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez TM, Zheng JQ. The molecular basis for calcium-dependent axon pathfinding. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:115–125. doi: 10.1038/nrn1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorczyca M, Augart C, Budnik V. Insulin-like receptor and insulin-like peptide are localized at neuromuscular junctions in Drosophila. J Neurosci. 1993;13:3692–3704. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-09-03692.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern ME, Chiba A, Johansen J, Keshishian H. Growth cone behavior underlying the development of stereotypic synaptic connections in Drosophila embryos. J Neurosci. 1991;11:3227–3238. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-10-03227.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada FN, Rosenzweig M, Kang K, Pulver SR, Ghezzi A, Jegla TJ, Garrity PA. An internal thermal sensor controlling temperature preference in Drosophila. Nature. 2008;454:217–220. doi: 10.1038/nature07001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson MG, Landmesser LT. Normal patterns of spontaneous activity are required for correct motor axon guidance and the expression of specific guidance molecules. Neuron. 2004;43:687–701. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopker VH, Shewan D, Tessier-Lavigne M, Poo M-m, Holt C. Growth-cone attraction to netrin-1 is converted to repulsion by laminin-1. Nature. 1999;401:69–73. doi: 10.1038/43441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H, Marton TF, Goodman CS. Plexin B Mediates Axon Guidance in Drosophila by Simultaneously Inhibiting Active Rac and Enhancing RhoA Signaling. Neuron. 2001;32:39–51. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00453-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubel DH, Wiesel TN. The period of susceptibility to the physiological effects of unilateral eye closure in kittens. J Physiol. 1970;206:419–436. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1970.sp009022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarecki J, Keshishian H. Role of neural activity during synaptogenesis in Drosophila. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15:8177–8190. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-12-08177.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen J, Halpern ME, Johansen KM, Keshishian H. Stereotypic morphology of glutamatergic synapses on identified muscle cells of Drosophila larvae. J Neurosci. 1989;9:710–725. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-02-00710.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakizawa S, Yamasaki M, Watanabe M, Kano M. Critical period for activity-dependent synapse elimination in developing cerebellum. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4954–4961. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-13-04954.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kano M, Hashimoto K. Synapse elimination in the central nervous system. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2009;19:154–161. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaupp UB, Seifert R. Cyclic Nucleotide-Gated Ion Channels. 2002. pp. 769–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]