Abstract

Cytokines play a major role in regulating both humoral and cell-mediated immune responses. Recent advances in our understanding of cell-mediated immune responses have focused on the antigen presentation machinery and the proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). These proteins help the formation and stabilization of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC)–peptide interaction. A 96-kDa, ER-resident glycoprotein (gp96) is being evaluated as a therapeutic agent in cancer because of its ability to associate with a vast number of cellular peptides irrespective of size or sequence. Because the antigen presentation complex is assembled in the ER and a number of ER-resident proteins are modulated by cytokines, it is important to examine the regulation of gp96 in response to immune cytokines interferon γ (IFN-γ), and interleukin 2 (IL-2). Defects in signaling pathway in either of the cytokines can result in suboptimal immune response. We examined the effect of the cytokines IFN-γ and IL-2 on the induction of gp96 in different cancer cell lines and examined the induction of DNA-binding proteins that recognize gamma interferon–activating sequence (GAS), present in the promoter region of gp96. The induction of GAS binding protein correlated with the induction of STAT 1 protein, a transcriptional regulator and mediator of IFN-γ–mediated gene expression. The use of cytokines in inducing gp96 levels may have significance in maintaining high levels of gp96 for a sustained immune response.

INTRODUCTION

Cytokines play a central role in differentiation and proliferation of both B- and T-lymphocytes that mediate humoral and cellular immunity. Cytokine therapy can alter the type of immune response, eg, administration of IL-12 can shift a TH2 response to a TH1 response (Kaplan 1993; Kobayashi et al 1998; Cousins et al 2002) and, in some cases, allow effective elimination of the pathogen. The success of a cellular immune response in response to a foreign pathogen or to cancer is dependent, in part, on the initial recognition of peptides complexed with the major histocompatibility antigens (MHC) by the T-cell receptor on mature T cells. Degradation of cancer-associated proteins would generate peptides, which when presented in the context of MHC can activate a cancer-specific T-cell response (Cresswell et al 1999; Cresswell and Lanzavecchia 2001). Cancers evade immune detection and elimination by inhibiting antigen presentation processes (Seliger et al 2000, 2002) such as downregulation of the MHC, inducing tolerance to cancer antigens (Zheng et al 1999; Makrigiannis et al 2001), and cancer-induced immune suppression (Costello et al 1999; Gilboa 1999; Greten and Jaffee 1999).

The heat shock protein (Hsp) gp96, present in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) binds to cellular peptides (Spee and Neefjes 1997; Sastry and Linderoth 1999; Linderoth et al 2001). This property of gp96 has been exploited for cancer therapy because purified gp96 from tumor tissues has associated cancer-specific peptides. Gp96-mediated cancer-specific immune response and tumor regression were observed in several animal models and human clinical trials (Suto and Srivastava 1995; Yedavelli et al 1999; Janetzki et al 2000; Caudill and Li 2001). This anticancer effect was mediated specifically by autologous tumor-derived gp96–peptide complexes. Neither the peptides alone nor gp96 alone could elicit the tumor protective effect (Srivastava et al 1998). The immunogen was the gp96-peptide complex, with specificity being imparted by the cancer-associated peptides. The use of tumor-derived gp96-peptide complexes affords a novel method of introduction and presentation of cancer antigens that can induce an effective T-cell response. Internalization of exogenous-administered gp96–peptide complexes by interaction with CD91, a putative receptor to gp96 (Binder et al 2000a, 2000b), affords a mechanism of re-presentation of antigens and induction of a cytotoxic T-cell (CTL) response. Gp96 plays a crucial role in the association of peptides in the ER, and because most of the proteins involved in antigen processing and presentation are modulated by cytokines, we examined whether gp96 can be modulated by the immune cytokines, IFN-γ and IL-2, and whether the signal transduction pathway used by some of these cytokines is intact in cancer cells.

The biological action of both IFN-γ and IL-2 is initiated by the binding of cytokine to its receptor and the activation of the Janus kinase (JAK) and the signal transducer–associated with signal transduction (STAT), the JAK-STAT pathway (Darnell 1997; Stark et al 1998; Bromberg and Darnell 1999). Two JAKs and 7 different STAT proteins that mediate the action of the various cytokines have been discovered (Bromberg and Darnell 2000; Shuai 2000). The use of these small numbers of proteins to mediate the effect of a very large group of cytokines is accomplished by the heteromeric and dimeric combinations (Shuai 2000) of the STAT proteins and the auto- and transphosphorylation action of the JAKs. These biochemical transformations can catalyze activation and translocation of transcriptional factors capable of inducing a large number of genes whose protein products mitigate cell differentiation and proliferation. Cancer cells during the course of their evolution use these signal transduction processes for both proliferation and resistance to apoptosis (Shuai 2000; Swannie and Kaye 2002).

The maintenance of T cells and the polarization of specific T cells will, in part, be dependent on the level of the T-cell–polarization cytokine IFN-γ and the T-cell–proliferating cytokine IL-2. In this article, we report the inducibility of gp96 by IFN-γ and IL-2 in a B-lymphoid cell line LG-2, lymphoblastoid cells T-2, and an epithelial cell line MCF-7.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

Cell lines used in this study, T-2 and LG-2, were grown in Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium 1640 (Mediatech, Herndon, VA, USA), whereas MCF-7 was grown in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (Mediatech, Herndon, VA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gemini, Calabasas, CA, USA), 50 IU/mL of penicillin (Mediatech), 50 μg/mL of streptomycin (Mediatech), and 2 mM of l-glutamine (Mediatech). The cytokines used were interferon gamma (IFN-γ) and interleukin 2 (IL-2). Antibodies used in this study were grp94 (Clone 9G10.F8.2) (Neomarkers, Fremont, CA, USA) and STAT 1 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA).

Western blot

Cells were treated with IFN-γ (1, 2, and 4 ng/mL) and IL-2 (2.5 and 5 Units/mL) for 3, 6, and 12 hours. At the end of the incubation period, the cells were harvested and washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The cells were lysed (1 × 106 cells/100 μL of lysis buffer) using RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.2% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 0.5% NP-40, and 1 μM Pefabloc), by incubating on ice for 30 minutes followed by sonication for 1 minute. The lysate was centrifuged at 14 000 rpm for 30 minutes, and the supernatant was collected. Cell lysates were subjected to 12.5% SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) (Laemmli 1970) under reducing conditions (presence of β-mercaptoethanol). The proteins were transferred to Immobilon-P membranes (Ashok et al 2001) at 200 mA for 2 hours, and the membranes were blocked with 5% milk–PBS-T (PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20) for 3 hours at room temperature on a shaker. Subsequently, the membrane was incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-gp96 antibody and anti-STAT 1 antibody on a shaker. Membranes were washed 3 times with 5% milk–PBS-T and incubated with anti-rabbit–horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugate (for STAT 1 antibody) and anti-rat–HRP conjugate (for grp94) for 1 hour at room temperature on a shaker. After 4 washes with milk–PBS-T and 1 wash with PBS, membranes were developed by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ, USA) and detected on X-ray film.

Gel shift assay

Gel shift assay was performed essentially as described earlier (Ashok et al 2002). For cytosolic extracts, the cells were suspended in 1 mL of buffer A (10 mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid [HEPES]–KOH, pH 7.9, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, and 10% glycerol) containing 0.5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.02% NP-40, and 0.01 mM protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) (added freshly before use) and incubated for 20 minutes on ice, vortexed for 5 seconds, and subsequently centrifuged for 10 minutes at 1800 rpm at 4°C. The supernatant [cytosolic extract] was collected, and to the nuclear pellet was added 200 μL of buffer C (20 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.9, 420 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid [EDTA], 25% glycerol) containing 0.5 mM DTT, 0.02% NP-40 and 0.01 mM protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma) per milliliter of buffer C were added (freshly before use) and incubated for 20 minutes on ice and then homogenized (10–15 strokes) for 5 seconds. The lysate was centrifuged at 10 000 rpm for 5 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant [nuclear extract] was collected and stored at −20°C until further use.

The gamma interferon–activation sequence (GAS) deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA)–binding element (binding site for interferon-γ–activation factor) was 5′-end labeled with [γ-32P]adenosine triphosphate using T4 polynucleotide kinase and was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (catalog # sc2537). The sequence is as follows: 5′-AAG TAC TTT CAG TTT CAT ATT ACT CTA-3′, 3′-TTC ATG AAA GTC AAA GTA TAA TGA GAT-5′.

The reaction mixture was incubated for 10 minutes at 37°C, and the reaction was stopped using 1 μL of 0.5 M EDTA, pH 8.0. To this was added 89 μL of TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA). An aliquot was used to determine the percentage of 32P incorporation. Two microliters of lysate (cytosolic or nuclear) were incubated in 2 μL of 5× binding buffer and 5 μL of nuclease-free water for 5–10 minutes, followed by the addition of 1 μL of 32P-labeled oligonucleotide (50 000–200 000 cpm) for 20 minutes at room temperature. Subsequently, 1 μL of 10× gel–loading buffer was added and subjected to 4% PAGE using 0.5× 45 mM Tris-borate and 1 mM EDTA (TBE) at 70 V for 3–4 hours. Gel was wrapped in saran wrap and exposed to X-ray film at −70°C overnight, and the film was developed.

RESULTS

Induction of gp96 by IFN-γ and IL-2 in LG-2 and T-2 cells

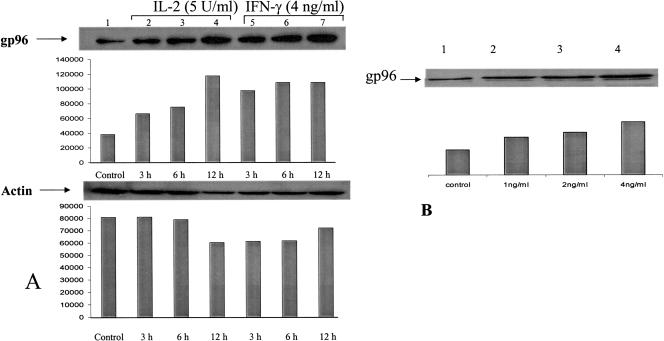

Both LG-2 and T-2 cells are responsive to IFN-γ and IL-2–mediated induction of gp96 in a dose-dependent manner (Fig 1 A,B), although the increase is not linear at 2 and 4 ng/mL of IFN-γ and 2.5 and 5 units of IL-2 in T-2 cells. The degree of induction of gp96 is 3–4 times higher in T-2 cells than in LG-2 cells. It is possible that almost saturable levels are reached at 2 ng of IFN-γ and 2.5 units of IL-2 in T-2 cells and not in LG-2 cells at similar concentrations. LG-2 cells when exposed to either 2.5 or 5 units of IL-2 had equivalent levels of induced gp96, whereas almost a linear responsiveness to IFN-γ is observed at 2 and 4 ng/mL. Quantitation of the protein level was done by normalization to protein content of cell extract and to actin levels. The induction level was also dependent on the constitutive level of gp96, which showed some variation and was presumed to be dependent on cell growth and passage level of the LG-2 cell line. In the case of IFN-γ–mediated induction of gp96 in LG-2 cells, there appears a threshold concentration below which no induction was observed.

Fig. 1.

(A) Detection of gp96 in LG-2 cells by Western blot. Cells were either untreated (lane 1) or treated with 2 and 4 ng/mL interferon gamma (IFN-γ) for 12 hours (lanes 2, 3) and 2.5 and 5 Units/mL interleukin 2 (IL-2) for 12 hours (lanes 4, 5), and lysates were separated by 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane for Western blot analysis. Gp96 was detected using anti-grp94 monoclonal antibody (Neomarkers) and developed using enhanced chemiluminescence. (B) Detection of gp96 in T-2 cells by Western blot. Cells were either untreated (lane 1) or treated with 2 and 4 ng/mL IFN-γ for 12 hours (lanes 2, 3) and 5 and 2.5 Units/mL IL-2 for 12 hours (lanes 4, 5) and gp96 detected in lysates as above

Gp96 levels are inducible by IFN-γ in MCF-7

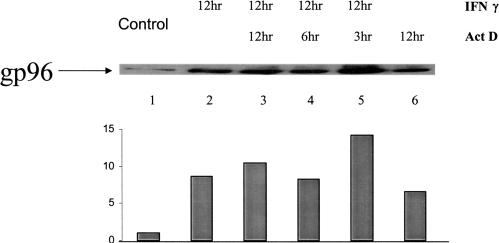

IL-2–mediated induction of gp96 in MCF-7 was observed (Fig 2A, lanes 2–4), although the induction kinetics was different. At 3 hours, no significant induction was observed with a steady increase at the 6- and 12-hour time points, suggesting an optimal increase in gp96 protein level between 3 and 6 hours with a plateau at 12 hours. Figure 2A,B shows a time- and dose-dependent increasing level of gp96 in MCF-7 cells in the presence of IFN-γ. At a concentration of 4 ng/mL, the induction was about 3- to 4-fold, which was comparable to the effects seen in LG-2 and unlike that in T-2, where the induction level was considerably higher than in either MCF-7 or LG-2. The steady time-course increase suggests that in MCF-7 cells, gp96 induction starts early and by 3 hours has doubled, with a consistent increase up to 12 hours, the highest time point represented in Figure 2. Steady levels of gp96 were seen up to 48 hours of continuous exposure to IFN-γ (data not shown). Figure 3 shows the effect of IFN-γ on the level of gp96 when actinomycin D, an inhibitor of ribonucleic acid (RNA) synthesis, is included in cell culture medium. Exposure to actinomycin D for 12 hours without IFN-γ (Fig 3, lane 6) showed an increase in the level of gp96 in the cytoplasm, suggesting that inhibition of RNA synthesis may stabilize the steady-state cytoplasmic protein level of gp96. When actinomycin D is added along with IFN-γ (Fig 3, lane 3), the level of induction is not the sum of lanes 2 (IFN-γ alone) and 6 (actinomycin D alone), suggesting that the 2 agents that induce gp96 levels individually do not have additive effects. Inhibition of overall RNA synthesis by actinomycin D also affects gp96 RNA synthesis. Inhibition of gp96 messenger RNA (mRNA) synthesis stabilizes cytosolic gp96 protein levels. The requirement of ongoing protein synthesis for the transcriptional activity and stabilization of gp96 protein remains to be examined.

Fig. 2.

Detection of gp96 in MCF-7 cells by Western blot. (A) Cells were either untreated (lane 1) or treated with interleukin 2 (IL-2) (5 Units/mL) for 3, 6, and 12 hours (lanes 2–4) and with interferon gamma (IFN-γ) (4 ng/mL) for 3, 6, and 12 hours (lanes 5–7), and lysates were separated by 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane for Western blot analysis. Gp96 was detected using anti-grp94 monoclonal antibody (Neomarkers) and developed using enhanced chemiluminescence. Actin was used as protein-loading control, and gp96 induction levels were normalized to actin levels. (B) Cells were either untreated (lane 1) or treated with 1, 2, and 4 ng/mL IFN-γ (lanes 2–4) for 12 hours and gp96 detected in lysates as above

Fig. 3.

Detection of gp96 in MCF-7 cells by Western blot. Cells were either untreated (lane 1) or treated with interferon gamma (IFN-γ) (4 ng/mL) for 12 hours (lane 2), IFN-γ and actinomycin D (1 μg/mL) for 12 hours (lane 3), IFN-γ and actinomycin D for 6 hours (lane 4), IFN-γ and actinomycin D for 3 hours (lane 5), or actinomycin D alone for 12 hours (lane 6), and lysates were separated by 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane for Western blot analysis. Gp96 was detected using anti-grp94 monoclonal antibody (Neomarkers) and developed using enhanced chemiluminescence

Induction of gp96 by IFN-γ is accompanied by enhanced levels of transcriptional inducers

STAT 1 homodimers have been implicated as the transcriptional factors that bind to GAS. Figures 4 and 5 show the level of STAT 1 and its binding to GAS elements in response to IFN-γ. A steady increase in the level of STAT 1 was noted in MCF-7 exposed to interferon for up to 12 hours of treatment mirrored the enhancement of gp96 level at a similar time point (Fig 4). Gel shift analysis with a consensus oligonucleotide containing GAS and interferon-stimulated response element (ISRE) as detailed in Materials and Methods was used to determine whether IFN-γ–induced cytoplasmic proteins bind to the DNA response element. GAS-like sequences TTC CAA CGA AA (accession no. M26596) occur at positions 102–112 in gp96 upstream of the AP2-binding site, which corresponds to the sequence TTN CNN NAA required for interferon-γ–mediated gene transcription. Figure 5 shows a 3- to 4-fold increase in the GAS-binding proteins. The presence of GAS in the regulatory region of gp96 suggests that induction of interferon-mediated gp96 follows the use of STAT 1 homodimers and presumably their binding to responsive GAS sequences in gp96.

Fig. 4.

Detection of STAT 1 in MCF-7 cells by Western blot. Cells were either untreated (lane 1) or treated with interferon gamma (4 ng/mL) for 3, 6, and 12 hours (lanes 2–4), and lysates were separated by 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane for Western blot analysis. STAT 1 was detected using anti-STAT 1 polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and developed using enhanced chemiluminescence

Fig. 5.

Detection of gamma interferon–activating sequence (GAS)–binding proteins by gel shift assay. MCF-7 cells were either untreated (lane 1) or treated with interferon gamma (4 ng/mL) for 3, 6, and 12 hours (lanes 2–4) and nuclear extracts made. The extracts were incubated with 32P-labeled GAS deoxyribonucleic acid element for 20 minutes at room temperature and run on 4% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The bands were detected by autoradiography

DISCUSSION

Active specific immunotherapy for human cancers, although challenging, is a viable option (Przepiorka and Srivastava 1998; Velders et al 1998; Greten and Jaffee 1999; Rosenberg 2001). The use of cancer-associated antigens specifically with the use of tumor-derived chaperone protein–peptide complexes is unique, yet the full potential cannot be attained until the regulatory components for a sustained immune response are defined. Among the regulatory components are cell surface receptor proteins that help in stabilizing cell-cell interaction and soluble factors, the cytokines (Bader and Weitzerbin 1994; Flores et al 1996; Forni et al 1997; Przepiorka and Srivastava 1998; Overwijk et al 2000) that are determinants of cell proliferation and differentiation. Cell-cell interaction in most part is confined to the interacting T cell with the antigen-presenting cells. Even if this interaction proceeds optimally, the presence of cytokines that can help polarization, differentiation, and proliferation of a subset of immunocompetent cells is obligatory. Cytokine functions are generally governed by specific cell surface receptors and a signal transduction pathway that can transmit membrane signals to the nucleus (Bader and Weitzerbin 1994; Flores et al 1996; Ramana et al 2000a, 2000b). The constant endeavor of a cancer cell would be to evade detection and downregulate all mechanisms that help the immunocompetent cells to eradicate tumor cells. It is in this context that the functioning of the parameters of cytokine signaling needs examination in cancer cells. With this in mind, we undertook this study to examine the cytokine-mediated up-regulation of gp96 in cancer cells of lymphoid and epithelial origins.

The Hsp gp96 is inducible by both IFN-γ and IL-2 in lymphoid (T-2 and LG-2) and epithelial (MCF-7) cells. The higher inducibility in T-2 cells that lack the transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP) is relevant. Both TAP and gp96 are ER proteins that bind peptides; TAP proteins are involved in shuttling peptides coming from the proteasomes into the ER, gp96 binds peptides indiscriminately (Arnold et al 1997; Lammert et al 1997; Spee and Neefjes 1997; Srivastava 2002a). Peptides bound to TAP also bind gp96, which suggests that there may be some protein-peptide binding hierarchy, and in the event that one protein is absent, as in the case of TAP in T-2, its biological function can be replaced by another protein such as gp96 (Srivastava 2001, 2002a, 2002b). Because we did not observe a higher constitutive level of gp96 between T-2 and LG-2, but the inducibility of gp96 was higher in T-2, we hypothesize that inducible gp96 may have protein-substitutive function. In the absence of cytokines, the normal cellular function, even if it requires replacement of TAP function, does not need elevated levels of gp96.

The protein gp96 is inducible by both IFN-γ and IL-2. Regulation of gp96 levels at the transcriptional and translational levels by both types I and II was reported earlier in 2 cancer cell lines, HeLa and Daudi cell lines (Anderson et al 1994). The response to both type I (IFN-α) and type II interferons (IFN-γ) is mediated by distinct receptors and signal-transducing proteins, and because gp96 is induced by both types of interferon, it would suggest overlapping domains of signal transduction molecules that can induce gp96. Similarly, it was also reported that gp96 is differentially expressed in activated lymphocytes in response to IL-2 (Damiani et al 1998). The presence of DNA response sequences conducive to the binding of STAT 1 homodimers that mediate IFN-γ induction and nuclear factor of activated T cells, NFAT, that mediate IL-2 induction suggests a biological role of gp96 that may be involved in T-cell polarization and T-cell proliferation (Banerjee et al 2002; Srivastava 2002a) in response to cytokines. Furthermore, the cytokine-mediated induction of gp96 is time and dose dependent, but a minimum threshold concentration is necessary. Because the extent of gp96 induction is variable in different cancer cells, it is possible that its contribution in peptide segregation and organization of the antigen presentation machinery in the ER is variable. This will depend partly on the presence of other obligatory proteins involved in the assembly of the MHC-peptide complex and if absent or deleted can promptly be replaced by gp96 under demand by a particular immune cytokine. Our results provide correlative evidence that in the case of IFN-γ, presence of the authentic STAT 1 dimers is involved, and the results of the induction of STAT 1 dimers, though expected, suggest that the authentic signal transducers are present and participate in the induction of gp96 and that continued induction of STAT 1 for 12 hours may be a significant requirement for concomitant enhancement of gp96 protein.

Stabilization of protein by inhibition of its RNA synthesis has been observed for other cytokine-inducible proteins (Ohh and Takei 1996; Guo et al 1997). The increase in the cytosolic protein level in response to actinomycin D treatment may be due to inhibition of degradation of already synthesized gp96 or to enhanced translational efficiency of the already translocated mRNA. The experimental results presented in this study are unable to distinguish between either of these possibilities except to show that inhibition of RNA synthesis enhances the cytosolic gp96 levels. Whether ongoing protein synthesis is required to stabilize gp96 is another important question that arises but one that is not addressed here. Experiments using protein synthesis inhibitors such as cycloheximide together with a detailed nascent and cytoplasmic RNA analysis will clarify the issue. Nevertheless, these results are indicative of the nature of gp96 induction in response to specific cytokine receptor–mediated signaling that levels off with the withdrawal of the inducer.

Further studies are required to delineate the precise role of gp96 in the ER in the organization of the MHC-peptide complex, but it is clear that this protein level can be modulated by immune cytokines similar to TAP, MHC, LMP2, and LMP7 (Arnold et al 1992; Yewdell et al 1994; Kang et al 2000). Cytokines secreted during immune response help maintain adequate levels of not only the immunocompetent cells but also of proteins that process antigens. Maintenance and prolongation of a good clinical response with the use of IFN-γ or IL-2 (or both) would be desirable in gp96-peptide complex–mediated active immunotherapy.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by US ARMY DAMD 17-98-1-8534 (R.K.T.), Granoff Foundation, and the Zita Spiss Foundation (R.K.T.).

REFERENCES

- Anderson SL, Shen T, Lou J, Xing L, Blachere NE, Srivastava PK, Rubin BY. The endoplasmic reticular heat shock protein gp96 is transcriptionally upregulated in interferon-treated cells. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1565–1569. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.4.1565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold D, Driscoll J, Androlewicz M, Hughes E, Cresswell P, Spies T. Proteasome subunits encoded in the MHC are not generally required for the processing of peptides bound by MHC class I molecules. Nature. 1992;360:171–174. doi: 10.1038/360171a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold D, Wahl C, Faath S, Rammensee HG, Schild H. Influences of transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP) on the repertoire of peptides associated with the endoplasmic reticulum-resident stress protein gp96. J Exp Med. 1997;186:461–466. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.3.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashok BT, Chen YG, and Liu X. et al. 2002 Multiple molecular targets of indole-3-carbinol, a chemopreventive anti-estrogen in breast cancer. Eur J Cancer Prev. 11:S86–S93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashok BT, Kim E, Mittelman A, Tiwari RK. Proteasome inhibitors differentially affect heat shock protein response in cancer cells. Int J Mol Med. 2001;8:385–390. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.8.4.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader T, Weitzerbin J. Nuclear accumulation of interferon gamma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:11831–11835. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.11831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee PP, Vinay DS, and Mathew A. et al. 2002 Evidence that glycoprotein 96 (b2), a stress protein, functions as a Th2-specific costimulatory molecule. J Immunol. 169:3507–3518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder RJ, Han DK, Srivastava PK. CD91: a receptor for heat shock protein gp96. Nat Immunol. 2000a;1:151–155. doi: 10.1038/77835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder RJ, Harris ML, Menoret A, Srivastava PK. Saturation, competition, and specificity in interaction of heat shock proteins (hsp) gp96, hsp90, and hsp70 with CD11b+ cells. J Immunol. 2000b;165:2582–2587. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.5.2582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromberg J, Darnell JE Jr.. The role of STATs in transcriptional control and their impact on cellular function. Oncogene. 2000;19:2468–2473. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromberg JF, Darnell JE Jr.. Potential roles of Stat1 and Stat3 in cellular transformation. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1999;64:425–428. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1999.64.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caudill MM, Li Z. HSPPC-96: a personalised cancer vaccine. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2001;1:539–547. doi: 10.1517/14712598.1.3.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello RT, Gastaut JA, Olive D. Mechanisms of tumor escape from immunologic response. Rev Med Interne. 1999;20:579–588. doi: 10.1016/s0248-8663(99)80107-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousins DJ, Lee TH, Staynov DZ. Cytokine coexpression during human Th1/Th2 cell differentiation: direct evidence for coordinated expression of Th2 cytokines. J Immunol. 2002;169:2498–2506. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.5.2498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell P, Bangia N, Dick T, Diedrich G. The nature of the MHC class I peptide loading complex. Immunol Rev. 1999;172:21–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1999.tb01353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell P, Lanzavecchia A. Antigen processing and recognition. Curr Opin Immunol. 2001;13:11–12. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(00)00174-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damiani G, Capelli E, Comincini S, Mori E, Panelli S, Cuccia M. Identification of mRNAs differentially expressed in lymphocytes following interleukin-2 activation. Exp Cell Res. 1998;245:27–33. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnell JE Jr.. STATs and gene regulation. Science. 1997;277:1630–1635. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5332.1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores I, Casaseca T, Martinez A, Kanoh H, Merida I. Phosphatidic acid generation through interleukin 2 (IL-2)-induced alpha-diacylglycerol kinase activation is an essential step in IL-2-mediated lymphocyte proliferation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:10334–10340. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.17.10334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forni G, Boggio K, Giovarelli M, Cavallo F. The dream of effective cytokine-based tumor vaccines. Eur Cytokine Netw. 1997;8:324–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilboa E. How tumors escape immune destruction and what we can do about it. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1999;48:382–385. doi: 10.1007/s002620050590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greten TF, Jaffee EM. Cancer vaccines. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1047–1060. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.3.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo FH, Uetani K, Haque SJ, Williams BR, Dweik RA, Thunnissen FB, Calhoun W, Erzurum SC. Interferon gamma and interleukin 4 stimulate prolonged expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase in human airway epithelium through synthesis of soluble mediators. J Clin Investig. 1997;100:829–838. doi: 10.1172/JCI119598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janetzki S, Palla D, Rosenhauer V, Lochs H, Lewis JJ, Srivastava PK. Immunization of cancer patients with autologous cancer-derived heat shock protein gp96 preparations: a pilot study. Int J Cancer. 2000;88:232–238. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20001015)88:2<232::aid-ijc14>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang JK, Yoon SJ, Kim NK, Heo DS. The expression of MHC class I, TAP1/2, and LMP2/7 gene in human gastric cancer cell lines. Int J Oncol. 2000;16:1159–1163. doi: 10.3892/ijo.16.6.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan G 1993 Recent advances in cytokine therapy in leprosy. J Infect Dis. 167(Suppl 1). S18–S22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K, Kai M, Gidoh M, Nakata N, Endoh M, Singh RP, Kasama T, Saito H. The possible role of interleukin (IL)-12 and interferon-gamma-inducing factor/IL-18 in protection against experimental Mycobacterium leprae infection in mice. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1998;88:226–231. doi: 10.1006/clin.1998.4533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammert E, Arnold D, and Nijenhuis M. et al. 1997 The endoplasmic reticulum-resident stress protein gp96 binds peptides translocated by TAP. Eur J Immunol. 27:923–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linderoth NA, Simon MN, Hainfeld JF, Sastry S. Binding of antigenic peptide to the endoplasmic reticulum-resident protein gp96/GRP94 heat shock chaperone occurs in higher order complexes. Essential role of some aromatic amino acid residues in the peptide-binding site. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:11049–11054. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010059200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makrigiannis AP, Pau AT, Saleh A, Winkler-Pickett R, Ortaldo JR, Anderson SK. Class I MHC-binding characteristics of the 129/J Ly49 repertoire. J Immunol. 2001;166:5034–5043. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.8.5034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohh M, Takei F. New insights into the regulation of ICAM-1 gene expression. Leuk Lymphoma. 1996;20:223–228. doi: 10.3109/10428199609051611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overwijk WW, Theoret MR, and Restifo NP 2000 The future of interleukin-2: enhancing therapeutic anticancer vaccines. Cancer J Sci Am. 6(Suppl 1). S76–S80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przepiorka D, Srivastava PK. Heat shock protein–peptide complexes as immunotherapy for human cancer. Mol Med Today. 1998;4:478–484. doi: 10.1016/s1357-4310(98)01345-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramana CV, Chatterjee-Kishore M, Nguyen H, Stark GR. Complex roles of Stat1 in regulating gene expression. Oncogene. 2000a;19:2619–2627. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramana CV, Grammatikakis N, Chernov M, Nguyen H, Goh KC, Williams BR, Stark GR. Regulation of c-myc expression by IFN-gamma through Stat1-dependent and -independent pathways. EMBO J. 2000b;19:263–272. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.2.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg SA. Progress in human tumour immunology and immunotherapy. Nature. 2001;411:380–384. doi: 10.1038/35077246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sastry S, Linderoth N. Molecular mechanisms of peptide loading by the tumor rejection antigen/heat shock chaperone gp96 (GRP94) J Biol Chem. 1999;274:12023–12035. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.12023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seliger B, Cabrera T, Garrido F, Ferrone S. HLA class I antigen abnormalities and immune escape by malignant cells. Semin Cancer Biol. 2002;12:3–13. doi: 10.1006/scbi.2001.0404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seliger B, Maeurer MJ, Ferrone S. Antigen-processing machinery breakdown and tumor growth. Immunol Today. 2000;21:455–464. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(00)01692-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuai K. Modulation of STAT signaling by STAT-interacting proteins. Oncogene. 2000;19:2638–2644. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spee P, Neefjes J. TAP-translocated peptides specifically bind proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum, including gp96, protein disulfide isomerase and calreticulin. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:2441–2449. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava P. Interaction of heat shock proteins with peptides and antigen presenting cells: chaperoning of the innate and adaptive immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002a;20:395–425. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.100301.064801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava P. Roles of heat-shock proteins in innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002b;2:185–194. doi: 10.1038/nri749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava PK. A central role for heat shock proteins in host deficiency. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2001;495:121–126. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0685-0_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava PK, Menoret A, Basu S, Binder RJ, McQuade KL. Heat shock proteins come of age: primitive functions acquire new roles in an adaptive world. Immunity. 1998;8:657–665. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80570-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark GR, Kerr IM, Williams BR, Silverman RH, Schreiber RD. How cells respond to interferons. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:227–264. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suto R, Srivastava PK. A mechanism for the specific immunogenicity of heat shock protein-chaperoned peptides. Science. 1995;269:1585–1588. doi: 10.1126/science.7545313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swannie HC, Kaye SB. Protein kinase C inhibitors. Curr Oncol Rep. 2002;4:37–46. doi: 10.1007/s11912-002-0046-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velders MP, Schreiber H, Kast WM. Active immunization against cancer cells: impediments and advances. Semin Oncol. 1998;25:697–706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yedavelli SP, Guo L, Daou ME, Srivastava PK, Mittelman A, Tiwari RK. Preventive and therapeutic effect of tumor derived heat shock protein, gp96, in an experimental prostate cancer model. Int J Mol Med. 1999;4:243–248. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.4.3.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yewdell J, Lapham C, Bacik I, Spies T, Bennink J. MHC-encoded proteasome subunits LMP2 and LMP7 are not required for efficient antigen presentation. J Immunol. 1994;152:1163–1170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng P, Sarma S, Guo Y, Liu Y. Two mechanisms for tumor evasion of preexisting cytotoxic T-cell responses: lessons from recurrent tumors. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3461–3467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]