Abstract

Previously we described an involvement of the C-type lectin receptor CD94 and the neuronal adhesion molecule CD56 in the interaction of natural killer (NK) cells with Hsp70-protein and Hsp70-peptide TKD. Therefore, differences in the cell surface density of these NK cell–specific markers were investigated comparatively in CD94-sorted, primary NK cells and in established NK cell lines NK-92, NKL, and YT after TKD stimulation. Initially, all NK cell types were positive for CD94; the CD56 expression varied. After stimulation with TKD, the mean fluorescence intensity (mfi) of CD94 and CD56 was upregulated selectively in primary NK cells but not in NK cell lines. Other cell surface markers including natural cytotoxicity receptors remained unaffected in all cell types. CD3-enriched T cells neither expressing CD94 nor CD56 served as a negative control. High receptor densities of CD94/CD56 were associated with an increased cytolytic response against Hsp70 membrane–positive tumor target cells. The major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I–negative, Hsp70-positive target cell line K562 was efficiently lysed by primary NK cells and to a lower extent by NK lines NK-92 and NKL. YT and CD3-positive T cells were unable to kill K562 cells. MHC class-I and Hsp70-positive, Cx+ tumor target cells were efficiently lysed only by CD94-sorted, TKD-stimulated NK cells with high CD94/CD56 mfi values. Hsp70-specificity was demonstrated by antibody blocking assays, comparative phenotyping of the tumor target cells, and by correlating the amount of membrane-bound Hsp70 with the sensitivity to lysis. Remarkably, a 14-mer peptide (LKD), exhibiting only 1 amino acid exchange at position 1 (T to L), neither stimulated Hsp70-reactivity nor resulted in an upregulated CD94 expression on primary NK cells. Taken together our findings indicate that an MHC class I–independent, Hsp70 reactivity could be associated with elevated cell surface densities of CD94 and CD56 after TKD stimulation.

INTRODUCTION

Natural killer (NK) cells are large granular lymphocytes comprising 5% to 20% of the peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMNCs) (Trinchieri 1989). In contrast to T cells, NK cells do neither express the multimolecular CD3 complex nor α/β and γ/δ T cell receptors. Almost all NK cells are positive for the neuronal adhesion molecule CD56, mediating homo- and heterophilic cell adhesion (Lanier et al 1986, 1989). With respect to the cell-surface density of CD56, 2 distinct NK cell subsets, the CD56dim and CD56bright could be distinguished (Cooper et al 2001). In the early host defense, NK cells secrete immunoregulatory cytokines including interferon-γ, interleukin (IL)–2, IL-12, tumor necrosis factor–α and granulocyte-macrophage colony–stimulating factor. NK cells also mediate natural cytotoxicity against virus-infected cells and tumor cells by release of apoptotic enzymes including granzymes and perforin or by antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity through the low affinity FcγRIII receptor CD16 (Lanier et al 1988). The cytolytic activity of NK cells is regulated by killer cell receptors, which are known to interact with self–major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class-I or class I–like molecules (Lanier 1998a, Borrego et al 2002). According to the missing-self theory, NK cells preferentially recognize and kill virus-infected or transformed cells with reduced, lost, or altered self-MHC class-I molecule expression (Ljunggren and Kärre 1990). In humans, 3 distinct killer cell receptor families have been identified (Lanier 1998a): killer cell immunoglobulin (Ig) receptors (KIRs), Ig-like transcripts (ILTs), and C-type lectin receptors. The KIRs are characterized by 2 or 3 extracellular localized Ig-like domains recognizing MHC class-I alleles including HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-C (Moretta et al 1993; Wagtmann et al 1995; Pende et al 1996). Depending on their cytoplasmic domain containing an immunoreceptor tyrosine–based inhibition motif or an immunoreceptor tyrosine–based activating motif, NK cells mediate inhibitory and activating signals (Colonna and Samaridis 1995; Biassoni et al 1996). ILTs also belong to the Ig-like superfamily (Colonna et al 1997; Cosman et al 1997). They are inhibitory receptors expressed predominantly on myeloid cells, dendritic cells, and B cells (Colonna et al 1997). ILT-2, which is expressed on some NK cells interacts directly with a broad spectrum of classical and nonclassical HLA molecules including HLA-G (Navarro et al 1999). Most C-type lectin receptors are heterodimers consisting of CD94 covalently bound to members of the NKG2 family (Lanier et al 1994; Lazetic et al 1996). These receptors interact with nonclassical HLA-E molecules, presenting leader peptides derived from HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-C, and HLA-G (Borrego et al 1998; Braud et al 1998; Lee et al 1998). CD94/NKG2A is an inhibitory receptor, whereas CD94/NKG2C, CD94/NKG2E, and CD94/NKG2F are activating receptors (Brooks et al 1997; Lanier 1998b). The activating receptor NKG2D also belongs to the C-type lectin family, but in contrast to other members it forms homodimers (Wu et al 1999). NKG2D is constitutively expressed on NK cells, γ/δ T cells, and CD8+ T cells and interacts with the MHC class I chain–related (MIC) antigens, MICA and MICB, and the UL16-binding proteins, which are induced by stress or neoplastic transformation (Bauer et al 1999; Cosman et al 2001). Recently, a new group of activatory receptors, termed natural cytotoxicity receptors (NCRs), consisting of NKp30 (Pende et al 1999), NKp44 (Vitale et al 1998; Cantoni et al 1999), and NKp46 (Pessino et al 1998) have been identified. Although NKp30 and NKp46 are constitutively expressed by almost all peripheral blood NK cells, the ligands regulating their expression and activatory function have not been defined yet.

By binding assays, an involvement of the C-type lectin receptor CD94 in the interaction of NK cells with Hsp70, the major stress-inducible member of the Hsp70 group could be demonstrated (Gross et al 2003). Tumor cells expressing the C terminal–localized Hsp70 sequence “TKDNNLLGRFELSG” (TKD, aa450–463) on their cell surface are preferentially recognized and lysed by NK cells (Multhoff et al 1999). Hsp70-protein and Hsp70-peptide TKD, both induce proliferative and cytolytic activity in NK cells (Multhoff et al 1999; 2001). Concomitantly, the expression of the C-type lectin receptor CD94 and the neuronal adhesion-molecule CD56 was found to be upregulated on CD3-negative NK cells (Multhoff et al 1999; Moser et al 2002). Other NK cell–specific receptors of the KIR family remained unaffected (Multhoff et al 1999). Because it is known that the cell surface density of CD56 (Cooper et al 2001) and CD94 (Voss et al 1998; Jacobs et al 2001; Lian et al 2002; Gunturi et al 2003) are associated with the cytolytic function, we aimed to study changes in the mean fluorescence intensity (mfi) of these 2 markers in CD94-positive NK cell lines in response to Hsp70-peptide TKD. These data were compared with the cytolytic capacity against classical MHC class I–negative NK target cells (K562) and MHC class I–positive but Hsp70-positive (Cx+) or Hsp70-negative (Cx−) tumor target cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tumor cell lines

The myelogenous cell line K562 was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (CCL 243, Rockville, MD, USA) and cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute-1640 medium (Gibco, Eggenstein, Germany) supplemented with heat-inactivated 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 2 mM L-glutamine, 1% penicillin-streptomycin (all supplements purchased from Life Technologies, Rockville, MD, USA) at 37°C and 5% CO2.

The colon carcinoma sublines Cx+ (Hsp70 membrane–positive) and Cx− (Hsp70 membrane–negative) derived by cell sorting (Multhoff et al 1997) from Cx2 colon carcinoma cells (Tumorzentrum Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany) differ with respect to their capacity to express Hsp70 on the plasma membrane. Cells were kept in culture under exponential growth conditions by regular cell passages. Every 3 days, cells were transferred after short-term (maximum, 1 minute) trypsinization using trypsin and ethylenediamine-tetraacetic acid solution (Gibco), and 0.5 × 106 cells were seeded in 5 mL fresh medium in T25 culture flasks.

In the cytotoxicity assay, K562 cells were used as a classical NK target, whereas Cx+ and Cx− cells were applied as MHC class I–positive tumor target cells.

NK cell lines

The human NK lymphoma cell line, NK-92 (Gong et al 1994) (ACC 488, DSMZ, Heidelberg, Germany), was grown in RPMI-1640 medium with 20% heat-inactivated FCS, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 2 mM L-glutamine, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and 100 IU/mL IL-2; doubling time was 40 to 50 hours at cell densities ranging from 0.2 to 0.6 × 106 cells/mL.

NKL cell line (Robertson et al 1996) was cultured in RPMI-1640 medium with 10% heat-inactivated FCS, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 2 mM L-glutamine, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and 100 IU/mL IL-2; doubling time was 40 hours at cell densities ranging from 0.5 to 1 × 106 cells/mL.

The IL-2 independent growing NK cell line YT (Yodoi et al 1985) (ACC 434, DSMZ) was cultivated in RPMI-1640 medium with 10% heat-inactivated FCS, 1 mM sodium-pyruvate, 2 mM L-glutamine, 1% penicillin-streptomycin; doubling time was 50 to 60 hours at a constant low cell density of 0.1 × 106 cells/mL.

Cytokine-induced killer cells

PBMNCs were isolated from buffy coats of healthy human volunteers by Ficoll separation followed by monocyte depletion. Peripheral blood lymphocytes were grown in RPMI-1640 medium with 10% heat-inactivated FCS, 25 mM Hepes (Invitrogen GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany), 2 mM L-glutamine, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol. A quantity of 1,000 IU/mL of human recombinant interferon-γ (Imukin, Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) was added on day 0. After a 24-hours incubation period, CD3 monoclonal antibody (mAb, Ortho Biotech, Neuss, Germany), 50 ng/mL (38.1; P. Martin, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA), 300 IU/mL IL-2 (Proleukin, Chiron Behring GmbH, Marburg, Germany), and 100 IU/mL rIL-1β (Roche Diagnostics GmbH) were added. Cells were incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 and subcultured every 3 days in fresh medium at a cell density of 0.4 × 106 cells/mL (Schmidt-Wolf et al 1991, 1997).

CD94-positive NK cells

PBMNCs were separated by positive selection using biotinylated CD94 mAb (HP3-D9, Ancell Immunology Research Products, Bayport, MN, USA) and a standard Miltenyi biotin separation method (Miltenyi, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). Briefly, 100 × 106 cells/mL were incubated with 5 μg biotin-conjugated CD94 mAb for 30 minutes at 4°C. After extensive washing with bovine serum albumin containing magnetic cell-sorting buffer (MACS-buffer, Miltenyi), cells were incubated with anti-biotin beads for 15 minutes at 4°C under gentle shaking. After washing, CD94-positive cells were separated using a LS/VS column (Miltenyi).

Sorted cells were incubated for 4 days in RPMI-1640 medium with 10% heat-inactivated FCS, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 2 mM L-glutamine, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 100 IU/mL IL-2, and 2 μg/mL Hsp70-peptide TKD (TKDNNLLGRFELSG, purity >96%; Bachem, Bubendorf, Switzerland) at 37°C. As a control, CD94-sorted NK cells were also incubated with the mutated peptide LKD (LKDNNLLGRFELSG, purity >96%; Bachem) under identical culture conditions. In long-term incubation experiments CD94-sorted NK cells were cultivated in fresh medium containing TKD (2 μg/mL) plus low-dose IL-2 (100 IU/mL) weekly for 5 weeks.

CD3-positive T cells (CD3)

CD3-positive T cells were separated by positive selection from PBMNC using the CD3-separation kit (Miltenyi) according to a protocol described above.

Sorted cells were incubated for 4 days in RPMI-1640 medium with 10% heat-inactivated FCS, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 2 mM L-glutamine, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 100 IU/mL IL-2, and 2 μg/mL Hsp70-peptide TKD (Bachem) at 37°C.

Treatment

Exponentially growing tumor cells were either heat shocked at a temperature of 42°C for 1 hour, followed by a recovery period of 12 hours or treated with 1 μM paclitaxel (Taxol-100, Bristol Arzneimittel, Munich, Germany) for 2 hours also followed by a recovery period of 12 hours. Previously published viability assays revealed that both treatment conditions were nonlethal for the tumor cells (Multhoff et al 1997; Gehrmann et al 2002). After treatment, cells were analyzed with respect to their MHC class-I, class-II, and Hsp70 membrane expression by flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry

The following mouse fluorescein-conjugated mAb, were used for phenotypic characterization of effector and target cells: isotype-matched controls (Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany), CD54 fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (Immunotech Coulter, Marseille, France), CD56 FITC (IgG2b, Becton Dickinson), CD57 phycoerythrin (PE) (IgM, Immunotech Coulter), CD94 PE (IgG1, HP-3D9, Ancell Immunology Research Products), CD3 FITC and CD16/CD56 PE (Simultest, IgG1, Becton Dickinson), NKp30 PE (IgG1, clone Z25, Beckmann Coulter, Krefeld, Germany), NKp46 (IgG1, clone BAB281, Beckmann Coulter), W6/32 PE (anti-MHC class-I, IgG2a, Cymbus Biotech, Eagle Close, UK), L243 PE (MHC DR, IgG2b, Immunotech Coulter), 87G (HLA-G, IgG2a, kindly provided by Dr D. Geraghty), TP25.99 (HLA-E, IgG1, kindly provided by Dr S. Ferrone), UIC2 (MDR-1, p glycoprotein, IgG2a, Immunotech Coulter), IMA310–0-C100 (MICA, IgG1, Immatics Biotech, Tübingen, Germany), and cmHsp70.1 FITC (Hsp70, IgG1, Multimmune GmbH, Regensburg, Germany).

Briefly, 0.5 × 106 cells were incubated with fluorescein-conjugated mAb at 4°C, for 30 minutes. After washing in phosphate-buffered saline supplemented either with 2% (NK-92, NKL, YT, K562, Cx+, Cx− cell lines) or 10% (CD94-positive, CD3-positive, cytokine-induced killer (CIK) primary cells) heat-inactivated FCS, the cells (200, 000) were analyzed on a FACS Calibur instrument (Becton Dickinson). The percentage of positively stained cells was calculated as the number of specifically stained cells minus the number of cells stained with an irrelevant isotype-matched control antibody.

Cell-mediated lympholysis assay

The cytolytic activity of primary effector cells and NK cell lines was monitored in a standard 51Cr cytotoxicity assay (MacDonald et al 1974). Different titrations (2:1, 1:1, 0.5:1 or 10:1, 5:1, 2:1 or 40:1, 20:1, 10:1) of effector and 51Cr-labeled (5 mCi of Na51CrO4, NEN-Dupont, Boston, MA, USA) tumor target cells (3 × 103 cells per well) were incubated in duplicate at a final volume of 200 μL (RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS) at 37°C in 96-well U-bottom plates (Greiner, Melsungen, Germany). For antibody blocking, tumor cells (0.5 × 106 cells) were incubated for 15 minutes with 5 μg/mL Hsp70-specific mAb (cmHsp70.1) after labeling and then used in the cytotoxicity assay without further washing. After a 4-hours incubation period, supernatants were collected and the radioactivity was quantified on a γ-counter (Canberra Packard Instruments, Dreieich, Germany). Spontaneous release was determined using the supernatants of target cells that had not been coincubated with effector cells. Maximum release was determined in the suspensions of 51Cr-labeled target cells. Specific lysis (%) was calculated according to the following equation: (experimental release − spontaneous release)/(maximum release − spontaneous release) × 100. The percentage of spontaneous release in all experiments was always less than 20% for each target cell line.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Separation of CD94-positive NK cells and CD3-positive T cells

We have shown previously that the C-type lectin receptor CD94 is involved in the interaction of NK cells with Hsp70, the major stress-inducible member of the Hsp70 family (Gross et al 2003). Tumor cells expressing the Hsp70 epitope “TKDNNLLGRFELSG” on their cell surface are recognized and lysed by CD3-negative, CD94-positive NK cells (Multhoff et al 1999). Incubation of primary human NK cells with Hsp70-peptide TKD plus low-dose IL-2 for 4 days results in an enhanced cytolytic activity against Hsp70-positive tumor cells (Multhoff et al 2001). Concomitantly, the percentage of CD94- and CD56-positive cells increased. Other NK cell markers including CD16 and KIRs (CD158a/b; CD158e1/e2; CD158k) remained unaffected. IL-2 alone increases the expression of CD94 and CD56 marginally, indicating that TKD might have a synergistic effect on the upregulation of these NK cell–specific markers (Multhoff et al 1999). In the present study, modulations in the protein density of CD56 and CD94 were compared in CD94-sorted, primary NK cells, and NK cell lines before and after stimulation with TKD. Concomitantly, the cytolytic capacity against the classical MHC class I–negative NK target cells (K562) and the MHC class I–positive, Hsp70 membrane–positive (Cx+) and membrane–negative (Cx−) tumor cells was tested.

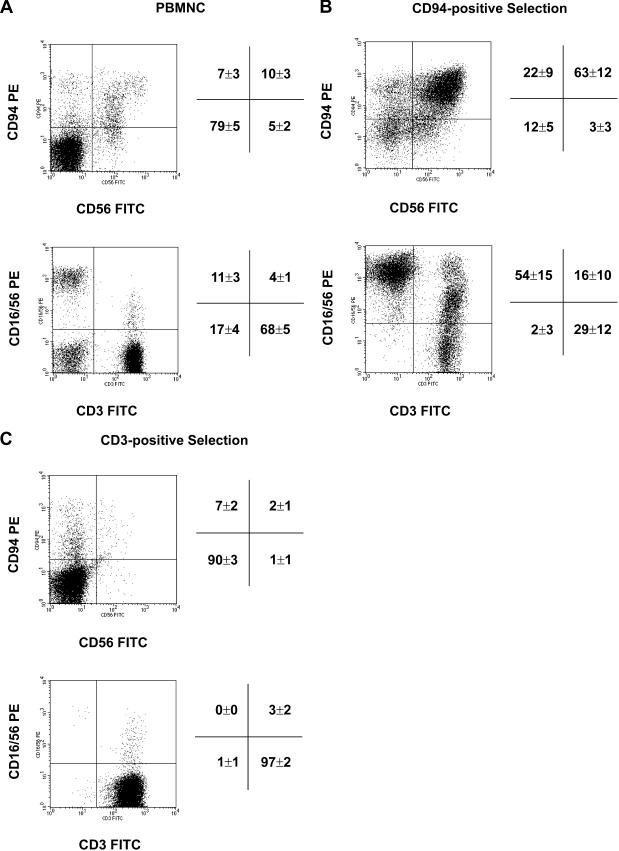

In the first set of experiments, CD94-positive NK cells were separated from PBMNCs of 8 healthy human volunteers by magnetic activated cell sorting (MACS). As a negative control, CD3-positive T cells were selected from 3 healthy human donors. Both positively enriched cell populations were cultured separately in the presence of low-dose IL-2 (100 IU/mL) and Hsp70-peptide TKD (2 μg/mL). The concentration of the supplements was identified as the optimal activating dose for human NK cells in kinetical studies (Multhoff et al 1999). The cell surface expression pattern of CD56, CD94, CD3, and CD16/56 in unstimulated PBMNC is illustrated in Fig. 1A. Freshly isolated cells were not phenotyped for CD94 and CD3 because antibody-coupled beads were still bound to the cell surface (data not shown). On day 4, after separation and stimulation a flow-cytometric analysis was performed. One representative result of the multiparameter flow cytometric analysis is illustrated in Fig. 1B, C. The mean percentages of positively stained cells ± standard deviation of all experiments are summarized and given on the right hand side of each individual graph. After positive selection for CD94 and stimulation with TKD, 63 ± 12% of the cells were found to be double positive for CD94 and CD56; 22 ± 9% were positive for CD94, only (upper panel). A minor part of cells (2 to 3 ± 3%) was found to be CD94- and CD3-negative. Because CD94 separation was not complete (purity >85%), on day 4 after stimulation, between 12% and 29% contaminating CD3-positive T cells were detected. With respect to the NK cell marker CD16/56 and the T cell marker CD3 this cell population contained 54% NK cells and 16% T cells (lower panel). A positive selection using a CD3-specific antibody followed by identical stimulation with TKD revealed that almost all cells (97%) were CD3-positive T cells; no CD16/56-positive NK cells (3%) were found. The percentage of CD94/CD56–positive cells was only 7%.

Fig 1.

CD94-positive NK cell and CD3-positive T cell selection. CD94-positive NK cells were selected from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMNC) derived from 8 healthy human donors using anti-CD94 biotin monoclonal antibody and anti-biotin magnetic microbeads. The phenotype of unseparated PBMNC (A) and CD94-positive NK cells (B) after stimulation with low-dose interleukin (IL)-2 (100 IU/mL) plus TKD (2 μg/mL) for 4 days was determined by flow cytometry using the following antibodies: CD3 fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), CD16/CD56 phycoerythrin (PE), CD56 FITC and CD94 PE. Dot-blot diagrams of 1 representative flow-cytometric analysis of CD94-positive NK cells on day 4 is shown. Mean values of the percentages of 8 experiments ± standard deviation are summarized on the right-hand side of each graph. CD3-positive T cells (C) were selected from PBMNC derived from 3 healthy human donors using anti-CD3 magnetic microbeads. Dot-blot analysis of 1 representative flow cytometry of CD3-positive cells after 4 days stimulation with low-dose IL-2 (100 IU/mL) plus TKD (2 μg/mL) and mean values of 3 experiments are shown.

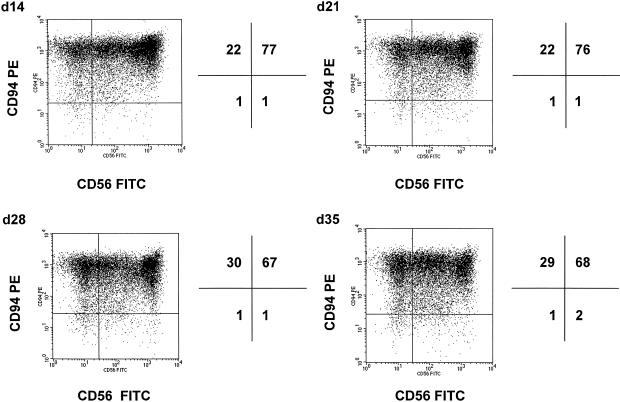

After long-term stimulation, the CD94/CD56–positive phenotype remained stable. Cells were incubated in fresh medium supplemented with TKD plus low-dose IL-2 once a week. Figure 2 shows representative dot-blot profiles of the CD94/CD56 staining of CD94-enriched NK cells on days 14, 21, 28, and 35. Although the percentages of CD94/CD56–positive cells remained constant, the mfi decreased during long-term culture (data not shown). The number of CD3-positive T cells did not increase; indicating that even repeated stimulation rounds with IL-2 plus TKD does not favor T cell growth. From these results, we conclude that it is possible to keep CD94/CD56–positive NK cells in culture for several weeks.

Fig 2.

CD94 and CD56 expression pattern on CD94-sorted, primary natural (NK) cells after long-term (5 weeks) stimulation with TKD. CD94-positive NK cells were cultured in medium containing low-dose interleukin (IL)-2 (100 IU/mL) plus TKD (2 μg/mL). Medium was completely renewed once a week. Cell density was kept at 2 × 106 cells/mL. Phenotypic characterization was performed by flow cytometry on days 14, 21, 28, and 35 using fluorescence-conjugated CD56 fluorescein isothiocyanate and CD94 phycoerythrin antibodies. The data represent 1 representative profile of 3 independent experiments

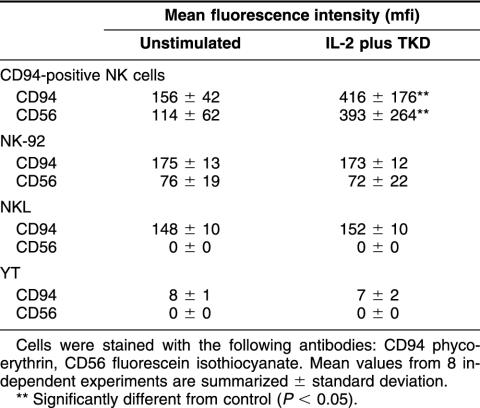

A comparison of the protein density, as determined by the mfi, of unstimulated and TKD-stimulated CD94-sorted NK cells and NK cell lines NK-92, NKL, and YT revealed that a significant increase in CD94 and CD56 expression was detected only with primary NK cells, within 4 days of stimulation (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of the mean fluorescence intensity (mfi) of unstimulated and interleukin (IL)-2 (100 IU/mL) plus TKD (2 μg/mL) stimulated CD94-positive, primary natural killer (NK) cells and NK cell lines NK-92, NKL, and YT

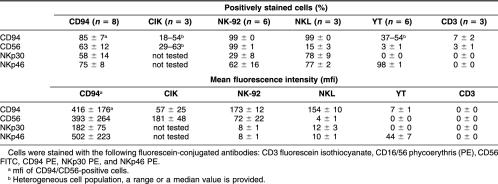

Comparative phenotypic characterization of the cell-surface markers CD94 and CD56 on primary NK, CIK, and T cells and on NK cell lines NK-92, NKL, and YT

In addition to the CD94 and CD56 expression, differences in the expression pattern of newly defined NCRs, NKp30 and NKp46 were tested in CD94-enriched NK cells, CD3-enriched T cells, and in NK cell lines NK-92, NKL, and YT after treatment with IL-2 plus TKD. In contrast to primary human NK cells, neither NK cell lines nor T cells showed any difference in their CD94, CD56, or NCR expression pattern after TKD stimulation. The percentages of positively stained cells and mfi values of all markers derived from 3 to 8 independent experiments after stimulation are summarized in Table 2. After cell sorting and TKD stimulation, 85% of the primary NK cells were positive for the C-type lectin receptor CD94; 63% of these cells also expressed the neuronal adhesion molecule CD56. NKp30 and NKp46 was found on 58% and 75% of the CD94-sorted cells, respectively, and on the NK lines NK-92 (29% and 62%) and NKL (78% and 77%) at variable percentages. These markers did not differ before and after stimulation with TKD. YT cells were negative for NKp30 (0%) but strongly positive for NKp46 (98%). CD3-sorted T cells were negative for all tested markers. Both NK cell lines, NK-92 and NKL, were found to express CD94 (99%). However, coexpression of CD56 was determined only on NK-92 cells (99%). In contrast, only a small subpopulation of 15% of the NKL cells did express CD56. As shown previously, the percentage of CD94-positive cells varied on YT cells between 13% and 52%, depending on the number of cells in culture; a negative correlation was consistently found with increasing cell densities (Gross et al 2003). With the culture conditions tested here, 37% to 54% of the YT cells were positive for CD94; CD56 was almost not detectable. CIK cells were also analyzed with respect to their CD94 and CD56 expression pattern. Because CIK cells are a heterogeneous cell population consisting of a mixture of T and NK cells, the percentages for CD94 and CD56 varied from 18% to 54% and from 29% to 67%, respectively. Because of this high variability, standard deviations were not provided for CIK cells.

Table 2.

Comparative phenotypic characterization of CD94-positive, primary natural killer (NK) cells, CD3-positive T cells, cytokine-induced killer cells, and NK cell lines NK-92, NKL, YT stimulated with low dose interleukin-2 plus TKD for 4 days

With respect to the mfi, again striking differences were found between primary NK cells and NK cell lines. Only primary NK cells reacted on TKD stimulation with a significantly upregulated mfi of CD94 from 156 to 416, and of CD56 from 114 to 393, between day 0 and day 4 (Table 1). The expression of NCRs remained unaffected by TKD stimulation (data not shown). In all other cell types, the mfi values of the tested markers remained unaltered. In comparison with NK cell lines, primary NK cells showed the highest expression levels of the cell surface markers CD94 and CD56 on day 4. The CD94 mfi values on CIK cells, NK-92, and NKL cells were 57, 170, and 193, respectively. Very low CD94 mfi levels were detectable in YT cells. With respect to CD56, the mfi values of CIK and NK-92 cells was 181 and 72, respectively; NKL cells showed low mfi values of 4. Positive mfi values for CD56 were not found in YT cells and CD3-positive T cells, lacking CD56 molecules on their cell surface. Significant mfi values of NKp30 and NKp46 were only found in CD94-sorted NK cells, after stimulation with TKD.

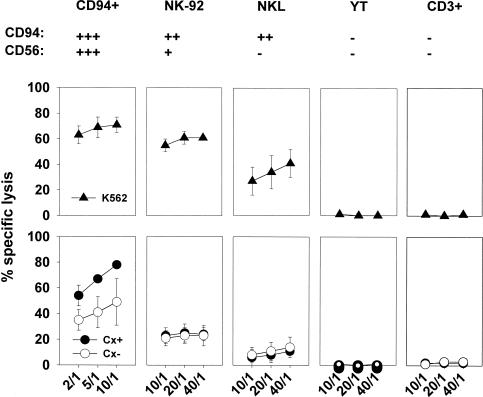

In summary, although the percentages of CD94-positive cells were comparably high in primary NK cells and NK cell lines NK-92 and NKL, striking differences were recorded with respect to the cell surface density of this receptor. Furthermore, only primary NK cells reacted with a significant upregulation in the cell surface density of CD94 after stimulation with TKD. All other tested markers remained unaltered. Similar results were seen for the neuronal adhesion molecule CD56. To distinguish the different NK cell types on the basis of their CD94/CD56 receptor density, the mfi values were marked in Figure 3 with + and − symbols as follows: mfi > 300, +++; mfi 150–300, ++; mfi 10–150, +; mfi < 10, −.

Fig 3.

Comparative cytolytic activity of CD94-positive, primary natural killer (NK) cells, NK-92, NKL, YT cell lines and CD3-positive, primary T cells. K562, Hsp70 membrane–positive Cx+ and negative Cx− cells were used as target cells in a 4-hours 51Cr cytotoxicity assay. The spontaneous release for each target cell was less than 20%. It is important to note that effector to target cell ratios ranged from 10:1 to 2:1 in case of CD94-positive, primary NK cells and from 40:1 to 10:1 in case of NK cell lines. Mean values of 3 independent experiments are shown

Association of the cell surface intensity of CD94/CD56 with Hsp70 reactivity

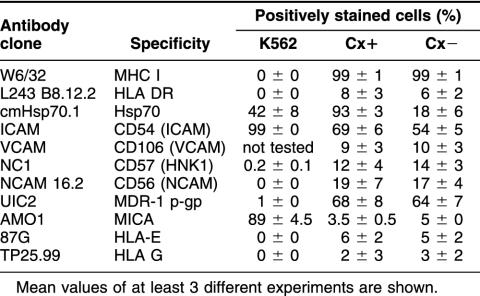

The cytolytic response of the different effector cells, prestimulated with TKD, was tested in a 4-hours cytotoxicity assay using the myeloid cell line K562 and the colon carcinoma sublines Cx+ and Cx− as target cells. A phenotypic characterization of the tumor cell lines is summarized in Table 3. Only Cx+ and Cx− colon carcinoma cells were found to be positive for MHC class-I molecules; the classical NK target cell line K562 was MHC class I–negative. With respect to the missing-self theory (Ljunggren and Kärre 1990), K562 cells are lysed because of a deficient MHC class-I expression associated with a lack of inhibitory signals for KIRs. On the other hand about 50% of the K562 cells do express Hsp70 on their cell surface and thus provide a recognition signal for the activating form of the C-type lectin receptor CD94. Therefore, we assumed that recognition of K562 cells is mediated by at least 2 receptor mechanisms: inactivating of inhibitory KIRs due to the missing MHC class-I expression and activating of the C-type lectin receptor due to the Hsp70 membrane expression. Because it is known that Cx+ and Cx− exhibit an identical MHC class-I and class-II expression pattern but differ significantly with respect to their Hsp70 membrane expression (Multhoff et al 1997), an involvement of KIR could be ruled out for the Hsp70 reactivity. In addition to MHC class-I, class-II, and Hsp70, the expression of several adhesion molecules including CD54 (intracellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)), CD106 (vascular adhesion molecule (VCAM)), CD57 and CD56 (neuronal adhesion molecule (NCAM)) were determined on the target cell lines. K562, Cx+ and Cx− tumor cells were strongly positive for CD54. With respect to the adhesion molecules CD106, CD57, and CD56, only Cx+ and Cx− tumor cells showed a comparable but weak expression; K562 cells were negative for these markers. Also, the multidrug resistance gene product MDR-1 was comparably expressed on Cx+ and Cx− tumor cells but not on K562 cells. With respect to the expression of the stress-inducible MHC-related molecule MICA, only K562 cells were found to be positive. HLA-E and HLA-G, as nonclassical MHC molecules mediating interaction with C-type lectin receptors (Borrego et al 1998), were not found on any of the tested tumor cell lines. A comparison of K562 and Cx+ and Cx− cell lines revealed differences in the MHC class-I, MDR-1, and MICA expression. In contrast, Cx+ and Cx− tumor sublines exhibited identity in all tested markers with 1 exception, the Hsp70 membrane expression.

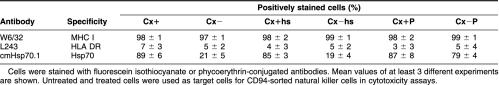

Table 3.

Phenotypic characterization of K562, Hsp70-positive Cx+ and Hsp70-negative Cx− target cells. Cells were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate or phycoerythrin-conjugated antibodies

The cytolytic response, mediated by different NK cell types was tested against all 3 target cell lines K562, Cx+ and Cx− cells. It is important to note that the effector to target cell ratios (E:T) ranged from 10:1 to 2:1 in the case of CD94-positive, primary NK cells and was 4-times higher (40:1 to 10:1) in all other effector cell lines. K562 cells were lysed by CD94-positive NK cells, NK-92, and NKL cells. At a defined E:T ratio of 10:1, CD94-positive cells showed the strongest cytolytic activity against K562 cells with 71%. In contrast only half of the K562 cells were killed by NK-92 cells at this E:T ratio. K562 cells were also killed by NKL cells but to a much lesser extent as compared with primary NK cells. YT cells and primary T cells did not lyse K562 cells at all. The MHC I-positive and Hsp70-positive Cx+ and Cx− tumor cell lines were only lysed by CD94-positive, primary NK cells; however, with respect to the differential Hsp70 membrane expression, lysis of Cx− cells was significantly weaker compared with that of Cx+ cells. Apart from primary NK cells, the NK cell lines were unable to kill Cx+ and Cx− target cells. This might be because of the inhibitory signal mediated by the MHC class-I expression. Only CIK cells exhibited a weak but indistinguishable lysis of Cx+ and Cx− cells, at an E:T ratio 4-times higher than that of primary NK cells (data not shown).

Because Cx+ and Cx− tumor cells differ only with respect to the Hsp70 membrane expression, we speculated that differences in lysis mediated by TKD-stimulated CD94-positive primary NK cells is due to Hsp70 that appears to function as an activating signal. CD94 has been found to be involved in the interaction of NK cells with Hsp70 protein (Gross et al 2003). Although all NK cell lines were positive for CD94, they showed different cytotoxicity against Hsp70-positive tumor target cells. Therefore, we suggest that the differences in cell kill might be associated with the cell surface density of CD94. Cells with high (+++, mfi > 300) expression levels of this receptor showed an increased kill of Hsp70-positive tumor cells. NK cells with moderate (++, mfi 150–300) or low (+, mfi < 10) expression levels in this marker did not show any Hsp70-specific kill, indicating an essential role of the protein density of CD94 for Hsp70 reactivity. Study of Michaelsson (2002) revealed that HLA-E, presenting leader peptides from Hsp60, results in increased sensitivity to lysis mediated by NK cells due to a loss of recognition by CD94/NKG2A inhibitory receptors. Because Cx+ and Cx− tumor cells both exhibited a comparable but very low HLA-E surface expression pattern and K562 cells completely lack expression of HLA-E, an involvement of HLA-E in the recognition by CD94-positive, primary NK cells was excluded. Similar to CD94, CD56 was upregulated in CD94-sorted, primary NK cells after stimulation with TKD. Because CD56 mediates homophilic cell adhesion, we speculated about a role of CD56 in the cytolytic response against Hsp70-positive tumor target cells. However, Cx+ and Cx− cells revealed identical CD56 expression levels (Multhoff et al 1997), whereas K562 cells lack CD56 expression (Table 3). In contrast to this finding, Cx+ and K562 cells, but not Cx− cells, were lysed by primary TKD-stimulated NK cells. Therefore, the involvement of CD56 in the cytolytic mechanism of Hsp70-positive tumor target cells remained to be elucidated. Concomitant with the finding that stimulation of NK cell lines NK-92, NKL, and YT with TKD did not increase the cell surface expression of CD94 and CD56, the cytolytic activity against Hsp70 membrane–positive tumor cells was also not enhanced.

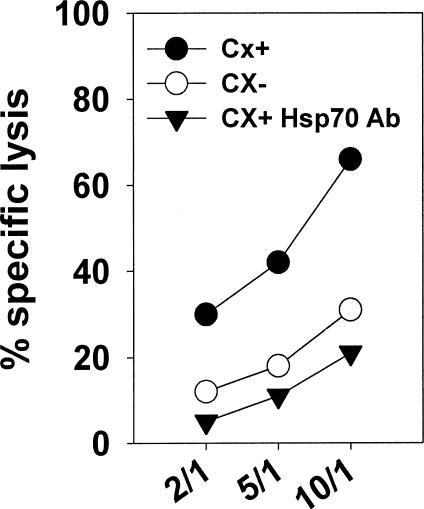

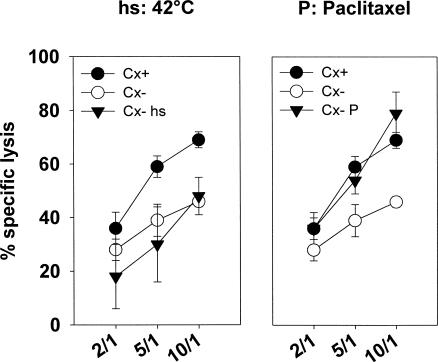

To prove that indeed Hsp70 provides the target structure for CD94-sorted, TKD-stimulated NK cells, antibody blocking studies were performed. As illustrated in Figure 4, the increased lysis of Cx+ tumor cells could be reduced to the degree of Cx− cell lysis by Hsp70-specific antibody. In contrast, lysis of Cx− cells remained unaffected after antibody incubation (data not shown). These findings were further supported by the fact that a paclitaxel-induced increase in membrane-bound Hsp70, especially on Cx− cells, correlated with an increased sensitivity toward lysis mediated by NK cells (Fig. 5). The Hsp70 phenotype together with the MHC class-I and II expression in Cx+ and Cx− tumor cells before and after nonlethal heat shock (42°C) or treatment with a nonlethal concentration of paclitaxel (1 μM) are summarized in Table 4. Heat was unable to induce an increased membrane expression of Hsp70 and thus lysis of Cx− cells remained unaltered (Fig. 5, left graph). However, after paclitaxel treatment (Fig. 5, right graph), Hsp70 expression was significantly upregulated in Cx− tumor cells. Concomitantly the percentage-specific lysis drastically increased. Because upregulation of membrane-bound Hsp70 in Cx+ cells was only marginal, no upregulated cytotoxicity of Cx+ cells was observed (data not shown). In summary, these findings clearly indicate that Hsp70 provides the target structure for TKD-stimulated, CD94-positive primary NK cells.

Fig 4.

Hsp70-specific antibody inhibits the increased lysis of Cx+ tumor cells. After labeling, Cx+ and Cx− tumor target cells were incubated for 15 minutes with Hsp70-specific monoclonal antibody (cmHsp70.1, 5 μg/mL) and used as targets for CD94-sorted natural killer cells. Lysis of Cx− cells remained unaffected after antibody treatment (data not shown). The spontaneous release for each target cell was less than 20%. Effector to target cell ratios were 10:1, 5:1, and 2:1

Fig 5.

Increased Hsp70 membrane expression after treatment with paclitaxel (P) increases lysis of Cx− tumor target cells. Cx+ and Cx− cells were either heat shocked at the nonlethal temperature of 42°C for 1 hour (hs) or incubated with a nonlethal dose of paclitaxel (1 μM) for 1 hour. The major histocompatibility complex class I, class II, and Hsp70 phenotype of the tumor target cells before and after treatment are summarized in Table 4. Cx− tumor cells exhibited an upregulated Hsp70 expression after P treatment that correlates with an increased sensitivity to lysis. Nonlethal heat shock neither increases Hsp70 membrane expression nor lysis of Cx− cells. The spontaneous release for each target cell was less than 20%. Effector to target cell ratios were 10:1, 5:1, and 2:1

Table 4.

Phenotypic characterization of viable Hsp70-positive Cx+ and Hsp70-negative Cx− target cells either untreated, after nonlethal heat shock (hs, 42°C for 1 h, 37°C for 12 h), or treatment with the nonlethal concentration of paclitaxel (P, 1 μM for 2 h, 37°C for 12 h; Gehrmann et al 2002)

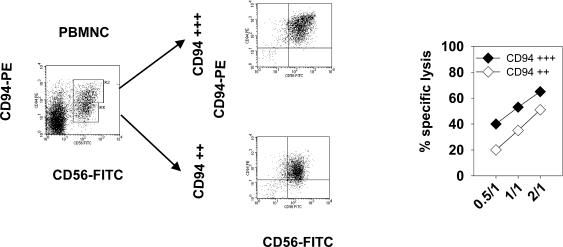

In an effort to further elucidate the role of CD94 in the cytolytic activity, more detailed additional cell-sorting experiments were performed. As demonstrated in Figure 6, primary NK cells consist of 2 subgroups that differ with respect to their CD94 mfi cell surface expression pattern. By cell sorting through CD94, 2 subpopulations with CD94 high (+++, mfi >300), and CD94 intermediate (++, mfi 150–300) mfi were generated. Both subpopulations were incubated separately with low-dose IL-2 and TKD for 4 days. A representative flow cytometric profile of both populations is illustrated in the middle panel of Figure 6. The CD94 high population was also strongly positive for CD56, whereas the CD94 intermediate population was weakly positive for CD56. Both subpopulations were tested as effector cells in a 4-hours cytotoxicity assay using MHC class-I and Hsp70-positive tumor cells as targets. As illustrated in Figure 6, the CD94 high population showed an increased killing activity of Hsp70-positive tumor cells compared with the CD94 intermediate population.

Fig 6.

Comparative cytolytic activity of CD94 high (+++) and CD94 low (++) expressing natural killer (NK) cells. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were separated in CD94 high (+++) and CD94 low (++) expressing NK cells by flow cytometry cell sorting. Both subpopulations were stimulated with low dose interleukin-2 (100 IU/mL) and TKD (2 μg/mL) for 4 days and used as effector cells in a 4-hours 51Cr cytotoxicity assay. Major histocompatibility complex class I- and Hsp70-positive tumor cells were used as target cells. The spontaneous release for each target cell was less than 20%. Effector to target cell ratios were only 2:1, 1:1, and 0.5:1

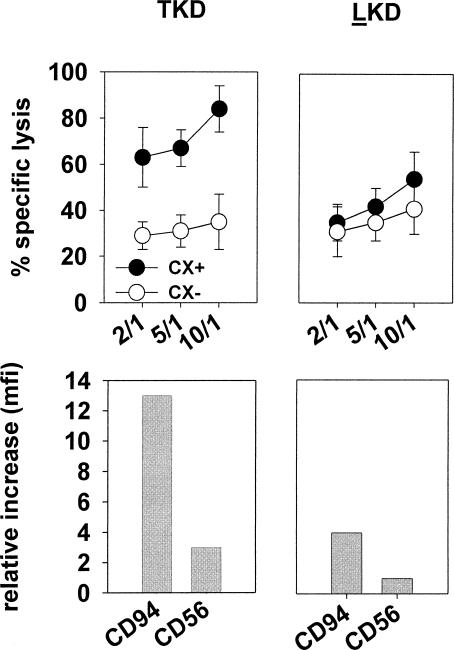

Finally, the role of the 14 amino acid peptide TKD, as a naturally occurring sequence of the Hsp70-protein, in the stimulation of the NK cell activity and CD94 expression was analyzed in comparison with a mutated 14-mer peptide that exhibits 1 amino acid sequence exchange at position 1 (T-L). Both peptides were tested under identical conditions (2 μg/mL for 4 days) with respect to their immunostimulatory efficacy on CD94-sorted, primary NK cells. Interestingly, only TKD but not LKD in combination with low-dose IL-2 (100 IU/mL) was able to induce Hsp70 reactivity toward Cx+ tumor cells. Furthermore, an increase in CD94 mfi was also only observed with TKD-stimulated NK cells (Fig. 7). Taken together, these findings support our hypothesis that indeed the mfi of the CD94 expression is a relevant marker for the Hsp70 reactivity.

Fig 7.

The 14-mer Hsp70-peptide TKD, but not the 14-mer LKD, exhibiting 1 amino acid exchange at position 1 (T to L), stimulates Hsp70 reactivity concomitant with an increase in the mean fluorescence intensity of CD94 on natural killer cells. Lysis of Cx+ tumor cells was significantly enhanced as compared with that of Cx− cells. The spontaneous release for each target cell was less than 20%. Effector to target cell ratios were 10:1, 5:1, and 2:1

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr M.J. Robertson for providing NKL cell line, Dr T. Whiteside for providing YT cell line, and Lydia Rossbacher and Gerald Thonigs for excellent technical assistance. The authors thank Dr M. Klouche (Department of Clinical Chemistry) for providing leukapheresis products. This study was supported by BMBF-grant (BioChance 0312338), by EU-grant TRANSEUROPE (QLRT 2001 01936), by multimmune GmbH, and Schering AG.

REFERENCES

- Bauer S, Groh V, Wu J, Steinle A, Philips JH, Lanier LL, Spies T. Activation of NK cells and T cells by NKG2D, a receptor for stress-inducible MICA. Science. 1999;285:727–729. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5428.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biassoni R, Cantoni C, and Falco M. et al. 1996 The human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-C-specific “activatory” or “inhibitory” natural killer cell receptors display highly homologous extracellular domains but differ in their transmembrane and intracytoplasmic portions. J Exp Med. 183:645–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrego F, Kabat J, Kim DK, Lieto L, Maasho K, Penta J, Solana R, Coligan JE. Structure and function of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I specific receptors expressed on human natural killer (NK) cells. Mol Immunol. 2002;38:637–60. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(01)00107-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrego F, Ulbrecht M, Weiss EH, Coligan JE, Brooks AG. Recognition of human histocompatibility leukocyte antigen (HLA)-E complexed with HLA class I signal sequence-derived peptides by CD94/NKG confers protection from natural killer cell-mediated lysis. J Exp Med. 1998;187:813–818. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.5.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braud VM, Allan DS, and O'Callaghan CA. et al. 1998 HLA-E binds to natural killer cell receptors CD94/NKG2A, B and C. Nature. 391:795–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks AG, Posch PE, Scorzelli CJ, Borrego F, Coligan JE. NKG2A complexed with CD94 defines a novel inhibitory natural killer cell receptor. J Exp Med. 1997;185:795–800. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.4.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantoni C, Bottino C, and Vitale M. et al. 1999 NKp44, a triggering receptor involved in tumor cell lysis by activated human natural killer cells, is a novel member of the immunoglobulin superfamily. J Exp Med. 189(5):787–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colonna M, Navarro F, and Bellon T. et al. 1997 A common inhibitory receptor for major histocompatibility complex class I molecules on human lymphoid and myelomonocytic cells. J Exp Med. 186:1809–1818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colonna M, Samaridis J. Cloning of immunoglobulin-superfamily members associated with HLA-C and HLA-B recognition by human natural killer cells. Science. 1995;268:405–408. doi: 10.1126/science.7716543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper MA, Fehniger TA, Turner SC, Chen KS, Ghaheri BA, Ghayur T, Carson WE, Caligiuri MA. Human natural killer cells: a unique innate immunoregulatory role for the CD56bright subset. Blood. 2001;97:3146–3151. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.10.3146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosman D, Fanger N, Borges L, Kubin M, Chin W, Peterson L, Hsu ML. A novel immunoglobulin superfamily receptor for cellular and viral MHC class I molecules. Immunity. 1997;7:273–282. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80529-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosman D, Mullberg J, Sutherland CL, Chin W, Armitage R, Fanslow W, Kubin M, Chalupny NJ. ULBPs, novel MHC class I-related molecules, bind to CMV glycoprotein UL16 and stimulate NK cytotoxicity through the NKG2D receptor. Immunity. 2001;14:123–133. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00095-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehrmann M, Pfister K, Hutzler P, Gastpar R, Margulis B, Multhoff G. Effects of antineoplastic agents on cytoplasmic and membrane-bound heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) levels. Biol Chem. 2002;383:1715–1725. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong JH, Maki G, Klingemann HG. Characterization of a human cell line (NK-92) with phenotypical and functional characteristics of activated natural killer cells. Leukemia. 1994;8:652–658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross C, Hansch D, Gastpar R, Multhoff G. Interaction of heat shock protein 70 peptide with NK cells involves the NK receptor CD94. Biol Chem. 2003;384:267–279. doi: 10.1515/BC.2003.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunturi A, Berg RE, Forman J. Preferential survival of CD8 T and NK cells expressing high levels of CD94. J Immunol. 2003;170:1737–1745. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.4.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs R, Hintzen G, Kemper A, Beul K, Kempf S, Behrens G, Sykora KW, Schmidt RE. CD56bright cells differ in their KIR repertoire and cytotoxic features from CD56dim NK cells. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:3121–3126. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(2001010)31:10<3121::aid-immu3121>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanier LL. NK cell receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998a;16:359–393. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanier LL. Activating and inhibitory NK cell receptors. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1998b;452:13–18. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-5355-7_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanier LL, Chang C, Philips JH. Human NKR-P1a. A disulphide-linked homodimer of the C-type lectin superfamily expressed by a subset of NK and T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1994;153:2317–2323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanier LL, Le AM, Civin CI, Loken MR, Phillips JH. The relationship of CD16 (Leu-11) and Leu-19 (NKH-1) antigen expression on human peripheral blood NK cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1986;136:4480–4486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanier LL, Ruitenberg JJ, Philips JH. Functional and biochemical analysis of CD16 antigen on NK cells and granulocytes. J Immunol. 1988;141:3478–3485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanier LL, Testi R, Bindl J, Phillips JH. Identity of Leu-19 (CD56) leukocyte differentiation antigen and neural cell adhesion molecule. J Exp Med. 1989;169:2233–2238. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.6.2233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazetic S, Chang C, Houchins JP, Lanier LL, Philips JH. Human natural killer cell receptors involved in MHC class I recognition are disulfide-linked heterodimers of CD94 and NKG2 subunits. J Immunol. 1996;157:4741–4745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee N, Llano M, Carretero A, Ishitani A, Navarro F, Lopez-Botet M, Geraghty DE. HLA-E is a major ligand for the natural killer inhibitory receptor CD94/NKG2A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:5199–5204. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian RH, Maeda M, Lohwasser S, Delcommenne M, Nakano T, Vance RE, Raulet DH, Takei F. Orderly and nonstochastic acquisition of CD94/NKG2 receptors by developing NK cells derived from embryonic stem cells in vitro. J Immunol. 2002;168:4980–4987. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.10.4980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ljunggren HG, Kärre K. In search of the missing self: MHC molecules and NK recognition. Immunol Today. 1990;11:237–244. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(90)90097-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald HR, Engers HD, Cerottini JC, Brunner KT. Generation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes in vitro. J Exp Med. 1974;140:718–730. doi: 10.1084/jem.140.3.718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelsson J, de Matos CT, Achour A, Lanier L, Kärre K, and Söderström K 2002 A signal peptide derived from hsp60 binds HLA-E and interferes with CD94/NKG2A recognition. J Exp Med 1403–1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moretta A, Vitale M, and Bottino C. et al. 1993 P58 molecules as putative receptors for major histocompatibilty complex (MHC) class I molecules in human natural killer (NK) cells. Anti-p58 antibodies reconstitute lysis of MHC class I-protected cells in NK clones displaying different specificities. J Exp Med. 178:597–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser C, Schmidbauer C, Gürtler U, Gross C, Gehrmann M, Thonigs G, Pfister K, Multhoff G. Inhibition of tumor growth in mice with severe combined immunodeficiency is mediated by heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70)-peptide-activated, CD94 positive natural killer cells. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2002;7(4):365–373. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(2002)007<0365:iotgim>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Multhoff G, Botzler C, Jennen L, Schmidt J, Ellwart J, Issels R. Heat shock protein 72 on tumor cells. A recognition structure for natural killer cells. J Immunol. 1997;158:4341–4350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Multhoff G, Mizzen L, Winchester CC, Milner CM, Wenk S, Kampinga HH, Laumbacher B, Johnson J. Heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) stimulates proliferation and cytolytic activity of NK cells. Exp Hematol. 1999;27:1627–1636. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(99)00104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Multhoff G, Pfister K, Gehrmann M, Hantschel M, Gross C, Hafner M, Hiddemann W. A 14-mer Hsp70 peptide stimulates natural killer (NK) cell activity. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2001;6(4):337–344. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(2001)006<0337:amhpsn>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pende D, Biassoni R, and Cantoni C. et al. 1996 The natural killer cell receptor specific for HLA-A allotypes: a novel member of the p58/p70 family of inhibitory receptors that is characterized by three immunoglobulin-like domains and is expressed as a 140–kDa disulphide-linked dimer. J Exp Med. 184:505–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pende D, Parolini S, and Pessino A. et al. 1999 Identification and molecular characterization of NKp30, a novel triggering receptor involved in natural cytotoxicity mediated by human natural killer cells. J Exp Med. 190(10):1505–1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessino A, Sivori S, Bottino C, Malaspina A, Morelli L, Moretta L, Biassoni R, Moretta A. Molecular cloning of NKp46: a novel member of the immunoglobulin superfamily involved in triggering of natural cytotoxicity. J Exp Med. 1998;188(5):953–960. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.5.953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson MJ, Cochran KJ, Cameron C, Le JM, Tantravahi R, Ritz J. Characterization of a cell line, NKL, derived from an aggressive human natural killer leukemia. Exp Hematol. 1996;24:410–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Wolf IGH, Negrin RS, Kiem HP, Blume KG, Weissman IL. Use of a SCID mouse/human lymphoma model to evaluate cytokine-induced killer cells with potent antitumor cell activity. J Exp Med. 1991;174:139–149. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.1.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Wolf GD, Negrin RS, Schmidt-Wolf IGH. Activated T cells and cytokine-induced CD3+ CD56+ killer cells. Ann Hematol. 1997;74:51–56. doi: 10.1007/s002770050257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinchieri G. Biology of natural killer cells. Adv Immunol. 1989;47:176–187. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(08)60664-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitale M, Bottino C, and Sivori S. et al. 1998 NKp44, a novel triggering surface molecule specifically expressed by activated natural killer cells, is involved in non-major histocompatibility complex-restricted tumor cell lysis. J Exp Med. 187(12):2065–2072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss SD, Daley J, Ritz J, Robertson MJ. Participation of the CD94 receptor complex in costimulation of human natural killer cells. J Immunol. 1998;160:1618–1626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagtmann N, Rajagopalan S, Winter CC, Peruzzi M, Long EO. Killer cell inhibitory receptors specific for HLA-C and HLA-B identified by direct binding and functional transfer. Immunity. 1995;3:801–809. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90069-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Song Y, Bakker AB, Bauer S, Spies T, Lanier LL, Philips JH. An activating immunoreceptor complex formed by NKG2D and DAP10. Science. 1999;285:730–732. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5428.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yodoi J, Teshigawara K, and Nikaido T. et al. 1985 TGGF (IL-2)-receptor inducing factor(s). I. Regulation of IL-2 receptor on natural killer-like cell line (YT cells). J Immunol. 143:1623–1630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]