Abstract

Background

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death among Latinos. Designing and delivering culturally appropriate interventions are critical for modifying behavioral and nutritional behavior among Latinos and preventing CVD.

Objective

This literature review provides information on evidence-based behavioral intervention strategies developed for and tested with at risk Latinos, which reported impacts on biological outcomes.

Methods

A literature search was performed in PubMed that identified 110 randomized controlled trials of behavioral interventions for CVD risk reduction with at risk Latinos (≥ 1 CVD risk factor, samples > 30% Latino), 4 of which met the inclusion criteria of reporting biological outcomes (BP, Cholesterol, LDL, HDL, and BMI).

Results

All the studies used promotoras(Hispanic/Latino community member with training that provides basic health education in the community without being a professional healthcare worker) to deliver culturally appropriate interventions that combined nutritional and physical activity classes, walking routes and/or support groups. One study reported statistically significant reductions in systolic blood pressure, and an increase in physical activity. One study reported reductions in cholesterol levels compared to the control group. Two studies did not have significant intervention effects. Most studies demonstrated no significant changes in LDL, HDL or BMI. Methodological limitations include issues related to sample sizes, study durations, and analytic methods.

Conclusion

Few studies met the inclusion criteria, but this review provides some evidence that culturally appropriate interventions such as using promotoras, bilingual materials/classes, and appropriate cultural diet and exercise modifications provides potentially efficacious strategies for cardiovascular risk improvement among Latinos.

Keywords: Latino/Hispanic, Cardiovascular Disease, Behavioral Intervention, Lay Health Workers, Review

Background

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death among Latinos.1According to statistics alone, Latinos with cancer and cardiovascular diseases have better outcomes compared to other racial/ethnic minority groups who have consistently worse health outcomes compared to whites even when controlling for socioeconomic status (SES).2–5This seemingly counter-intuitive trend can be explained by the “Hispanic Paradox” theory, which describes possible explanations for the lower morbidity and mortality among Latinos, including cardiovascular disease, compared to other minority racial-ethnic groups despite Latinos lower SES.3,5The “Hispanic Paradox” has been postulated to be due to various factors: 1) recent healthy immigrants to the U.S. or “healthy immigrant effect”, 2) lower reporting of illness to government agencies or data artifacts, or 3) when ill, Latinos decide to return to their country of origin or the “reverse migration”.5,6 A combination of these and other factors likely contribute to the better statistical indicators of the health of Latinos in the U.S.

Despite this “Hispanic Paradox,” the lack of healthcare coverage, low SES and language barriers of Latinos potentiate a future cardiovascular crisis.2Medical and behavioral interventions, with and without the assistance of promotoras, have been utilized to improve the outcomes of Latinos with cardiovascular disease.7,8 A promotora is a Hispanic/Latino community member with training who acts an advocator, educator, mentor and outreach worker to provide basic health education in the community without being a professional or licensed healthcare provider.3 Promotoras are key components of many behavioral interventions with Latinos as they share the community’s background and language, and understand the needs of the community. Designing and delivering culturally appropriate interventions are critical for behavioral and nutritional success of Latinos.4

Most behavioral interventions target people’s awareness of risk factors and their behaviors to improve exercise and eating habits. The use of promotoras, in conjunction with interpersonal and printed nutrition and exercise information can aid in healthy changes or self-care in Spanish speaking communities.9,10 Research has shown that healthy eating and exercising produces healthy outcomes in people, especially in those with chronic diseases.10,11This literature review will provide information on the evidence-base of behavioral intervention strategies developed for and tested with Latinos to inform clinician’s options for supporting improved cardiovascular outcomes among Latinos.

Methods

A literature search was performed in PubMed Medline using a combination of keywords and Medical subject heading [Mesh] terms (See Box 1). Search limits were set to randomized controlled trials (RCTs), peer-reviewed studies, articles published up to June 2015, and English-language studies conducted in the US.Inclusion criteria included publications with; 1) lifestyle behavioral interventions, 2) patients with no coronary heart disease but with 1 or more cardiovascular disease risk factor, 3) adults age 18 years and older, 4) more than 30% Latino sample (U.S. born and foreign born), and 5) biological outcomes reported. Relevant literature reviews were also reference mined to identify potential articles that met inclusion criteria.12–14

Box 1. Search strategy.

Database searched: PubMed Medline

Language: English

Dates: - June 2015

Search strategy: (“Latino/Hispanic” [tiab] OR “Hispanic Americans” [Mesh] OR “*Mexican Americans/psychology/statistics & numerical data” [Mesh] OR “*Mexican Americans” [Mesh]) AND (“Cardiac/Heart Disease/Cardiovascular Disease” OR “Blood Pressure” [Mesh] OR “Body Mass Index” [Mesh] OR “Cardiovascular Diseases/*ethnology/prevention & control” [Mesh] OR “Hypertension/*ethnology/prevention & control” [Mesh] OR “Coronary Disease/ethnology/*prevention & control” [Mesh] OR “Obesity/*ethnology/psychology/therapy ”[Mesh] OR “Risk Factors” [Mesh]) AND (“Community Health Workers” [Mesh] OR “Promotora” [tiab] OR “Intervention” OR “Health Behavior” [Mesh] OR “*Life Style” [Mesh] OR “*Health Behavior” [Mesh] OR “*Health Promotion” [Mesh])

The outcomes reported were blood pressure (BP), total cholesterol, low density lipoprotein (LDL), high density lipoprotein (HDL), body mass index (BMI). Secondary outcomes reported were serum triglycerides, participation in healthy eating and physical activity, 10-year coronary heart disease (CHD) Risk Score. The 10-year CHD Risk Score is a composite measure of CVD risks that estimates the probability of having a CHD event during the next 10 years.15We operationalized “at risk” by accepting and using the authors definitions because studies were heterogeneous with this respect and conducted at different time periods utilizing different biomarker thresholds. Studies that focused exclusively on patients with diabetes mellitus type 2 were excluded as they focus primarily on diabetes self-care tailored for hemoglobin A1C outcomes.

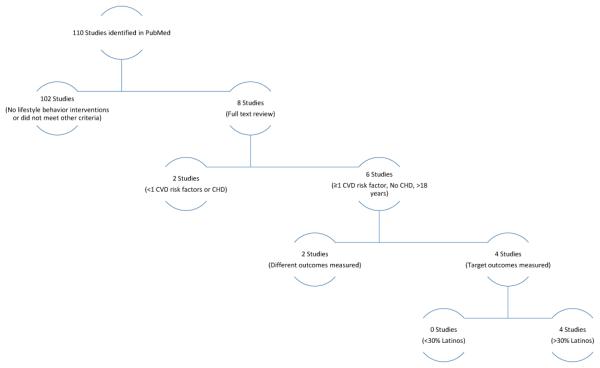

This literature search generated 917 initial studies and 807 were excluded after reviewing the title and abstract. After reviewing 110 full text articles, we were left with 5 studies which met the inclusion criteria after assessment for eligibility. After excluding one study because of small sample size (n=4) in the intervention and control groups (n=4),16 we were left with 4 studies that were included in the review. We used the PRISMA 2009 checklist as a guide for data collection.17We extracted the authors’names, year published, study design, study population characteristics, use of promotoras, intervention details, and outcomes for the 4 articles that met the inclusion criteria. The analyses also included risk of bias.18

Results

Four studies met the eligibility inclusion criteria and were randomized controlled trials.2–4,19 The studies had participants of variable ages (18-75 years), 2 studies had 100% female participants, and the 2 studies conducted by Balcazar et al had 70% - 88% female participants.2–4,19Hayashi et al and Balcazar et al, used promotoras as allied community health workers to promote and lead the behavioral interventions. Most behavioral interventions focused on educating patients on nutrition, physical activity and healthy habits, but also developed physical activity plans for patients (Table 1).

Table 1.

Study design characteristics

| Autho r, Date, Count ry |

Stud y Desi gn |

Sample | Setting | N control/ intervent ion |

Intervent ion |

Durati on |

Follo w Up |

Promotor as* |

Participat ion Rates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hayas hi et al, 2010, USA |

RCT | 100% Latinos, mean age 52, range 40-65 years 100% - Female Low income Underinsu red |

Los Angeles and San Diego, CA |

436/433 - | Promotora s delivered 3, 30 minute one-to- one sessions of nutritional and physical activity counselin g at 1, 2 and 6 months using the “New Leaf curriculu m” at doctor’s visits. |

6 months |

12 mont hs |

Yes | Control: 541➔436 (81%) Interventio n: 552➔433 (78%) |

|

| |||||||||

| Balcaz ar et al, 2010, USA |

RCT | 90% Latinos, 53% born in Mexico, mean age 54, range 30-75 years 70% - Female |

El Paso, Texas border region |

136/192 | Promotora s delivered 2 hours/wee k × 8 weeks “Su Corazon, Su Vida” sessions to small groups. |

2 months |

2 mont hs |

Yes | Control: 136➔126 (93%) Interventio n: 192➔158 (82%) |

|

| |||||||||

| Balcaz ar et al, 2009, USA |

RCT | 100% Latinos mean age 55 88% females |

El Paso, Texas border region |

40/58 | Promotora s delivered 2 hours/wee k sessions, total interventi on × 9 weeks using “Su Corazon, Su Vida” curriculu m. |

7 weeks |

4 mont hs |

Yes | Control: 40➔ 40 (100%) Interventio n: 58➔58 (100%) |

|

| |||||||||

| Poston et al, 2001, USA |

RCT | 100% Latinos of Mexican- American descent, mean age 40, range 18-65 years 100% - Female overweigh non- diabetic, 87% fluent in Spanish or bilingual, and 76% U.S. born |

Southern Texas communit ies along the US- Mexico border |

135/102 | Counselin g instructors in a clinical setting assigned participan ts to 30 minutes of brisk walking 5x/week. |

6 months | 6 mont hs |

Counselor | Control: 185➔ 135 (73%) Interventio n: 194➔ 102 (53%) |

--- not reported;

promotora = lay community health worker

Hayashi et al focused on low-income and underinsured patients.2Promotoras delivered three 30 minutes one-to-one sessions of nutritional and physical activity counseling at 1-, 2-, and 6-months using the “New Leaf” curriculum at doctors’ visits. The intervention lasted for 6 months and the participants were followed up after 12 months.2Women in the intervention group (n=433) had better eating habits and increased physical activity than the control group (n=436) over time (Table 2). There was no improvement in cholesterol. There were within group improvements in HDL but no between group improvements.2The intervention group also had a reduction in BMI over time (p<0.05) but between group differences were not significant. Within both control and intervention groups there was a reduced systolic blood pressure, and a statistically significant difference in reductions between groups (I: Δ-5.9 vs. C: Δ-3.7, p=0.038). Furthermore, there was a statistically significant improvement in the 10 year CHD Risk Score in the intervention group compared to the control group (I: Δ-0.009 vs. C: Δ-0.005, p=0.05).

Table 2.

Results for within and between groups

| Author, Date, Country |

Change in BP (mmHg) |

Change in Cholesterol (mg/dL) |

Change in LDL (mg/dL) |

Change in HDL (mg/dL) |

Change in BMI (kg/m2) |

Other outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hayashi et al, 2010, USA |

Diastolic C: 77➔74 I: 77➔73 Systolic C:125➔121* I:125➔119* |

C: 198➔199 I: 198➔200 |

--- | C: 45➔ 467 I: 45➔ 48 |

C: 32➔ 32 I: 32➔31 |

10 year CHD Risk Score: C: 0.071➔0.066 (− 0.005)* I: 0.069➔0.060 (− 0.009)* Improvement in eating habits C: 33.1%** I: 58.4%** Improvement in physical activity C: 42.3%** I: 57.3%** |

|

| ||||||

| Balcazar et al, 2010, USA |

Diastolic C: 141➔133** I: 137➔132** Systolic C: 89➔78** I: 80➔ 78** |

C: 191➔191 I: 198➔192 |

C: 120➔120 I: 128➔121 |

C: 43➔42 I: 41➔41 |

C: 31.1➔31.2 I: 31.7➔31.6 |

Triglyceride level (mg/dL) C: 139.1➔139.2 I: 134.7➔140.9 |

|

| ||||||

| Balcazar et al, 2009, USA |

Intervention with 27% decrease in the number of participants with a blood pressure of 120-139/80- 89 mmHg Control with 15% increase in the number of participants with a blood pressure of 120-139/80- 89 mmHg |

--- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

|

| ||||||

| Poston et al, 2001, USA |

Diastolic C: 73➔ 69 I: 73➔71 Systolic C118➔116 I: 116➔117 |

C: 202➔193 I:199➔188 |

--- | --- |

C: 34➔34 I: 34➔33 |

Triglycerides (mg/dL) C: 129➔149 I: 129➔140 Activity Levels (kcal/kg/day) C: 36➔37 I: 35➔36 Activity (Hours/week) C 11➔13 1: 8➔11 |

Notes:

The data presented from these 4 research studies are the changes from baseline to the end of the study. C= control group and I = intervention group

p<0.05

p<0.01

Balcazar et al focused on Latinos in El Paso, Texas, and tested the “Su Corazon, Su Vida” curriculum delivered by promotoras in one 2-hour session per week for 8 weeks.3Follow up assessment was done 2 months after the final 2 hour session. The intervention group (n=192) was given 8 health classes while the control group (n=136) was given only basic educational materials (i.e. pamphlets) at baseline. Both intervention and control groups had improved diastolic blood pressures (Table 2). The difference between both group’s blood pressure was statistically, but not clinically, significant. Participants in the intervention group had improved dietary and exercise habits (i.e. better weight control practices). Also, total cholesterol was 3% lower in the intervention group and LDL cholesterol levels were 5% lower in the interventional group at follow-up.

Poston et al focused on Latina women who were overweight without diabetes.4 The intervention was led by counseling instructors in a clinical setting and was based on social cognitive theory by encouraging participants to exercise more by managing personal and social pressures, including social reinforcement, in hopes of improving cardiovascular risk factors. Clinical instructors assisted participants in finding ways to increase physical activity in their daily routine (i.e. taking stairs). The control group participants (n=135) were given basic educational materials. Each participant in the intervention group (n=102) was assigned to 30 minutes of brisk walking 5 times a week for 6 months. Blood pressure, cholesterol, LDL, HDL, BMI and Triglycerides levels after 6 months were not statistically significant for differences between the control and intervention groups over time.4

Discussion

We found few randomized controlled behavioral interventions delivered by promotoras to reduce biological cardiovascular risk factors among Latinos. Considering the applicability of using these behavioral interventions to reduce cardiovascular disease in at risk Latinos we must consider both statistical and clinical significance. Hayashi et al showed that the use of promotoras delivering competent and culturally appropriate behavioral interventions may reduce blood pressure and the 10-year CHD Risk Scores in at risk Latinas.2Balcazar et al. showed that the difference between the intervention and control group blood pressure was statistically significant, however, they are likely not clinically significant (i.e., improvements were very small).3,4The study conducted by Poston et al., found that the intervention did not increase physical activity or improve CVD risk factors, although contamination of the control group may partially account for this outcome.4 Contamination resulted because randomization was done by street blocks rather than individually. The study was not completely randomized as individuals were randomized from pre-established social groups (i.e. neighbors, coworkers and family members), which can also account for the discrepancy in outcomes.

The differences in results reported by the 5 studies in Table 1 can be appreciated by looking at the intensity and duration of the interventions. Hayashi et al used 3, 30 minute one-to-one sessions of nutritional and physical activity counseling at 1, 2 and 6 months using the “New Leaf curriculum” and demonstrated evidence for efficacy of the intervention.2 Balcazar et al delivered the “Su Corazon, Su Vida” sessions with promotoras to small groups for 2 hours per week for 8 weeks and found statistically, but not clinically, significant group differences. Poston et al. used counseling instructions to assign participants to 30 minutes of brisk walking 5 times per week for 6 months, but did not find significant group differences due to a combination of external intervention contamination and imperfect randomization procedures.4

Across all the studies, only Hayashi et al had statistically significant intervention effects for reductions in systolic blood pressure. The reduction was by 6 points, making it clinically relevant to potential reduction in blood pressure. Hayashi et al also showed a significant reduction in the 10-year CHD Risk Score in the intervention group compared to the control group. Balcazar et al showed a statistical significant reduction in diastolic blood pressure but not a clinically significant reduction.3However, Balcazar demonstrated a reduction in the intervention group’s cholesterol levels compared to the control group. Most studies demonstrated no significant reduction in LDL, increase in HDL levels or changes in BMI between the control and intervention groups.

Overall, there are major limitations to these studies reviewed because most significant reductions were observed within groups but not between control and intervention groups. This was likely due to various factors such as the small sample size of the studies. Furthermore, the short term follow up, such as Balcazar et al’s 2 months, could have contributed to non-significant results between the control and intervention groups.3Thus, these and other factors limited the impact of the studies. Another limitation of the review is the possibility of publication bias and that we did not identify all studies that met the inclusion criteria. The generalizability of the studies is limited because these studies predominantly enrolled woman. Latino men are less likely to seek out health care services and participate in research. We acknowledge that diabetes is a risk factor for CVD, but we excluded these studies a prioribecause diabetes promotorainterventions focus on blood sugar control (e.g. reduction of A1C levels).20Finally, the studies included in the review did not use the same clinical guideline criteria to categorize their patient populations as an at risk population. Because of the heterogeneity and lack of information in the papers regarding this, we accepted the author’s definition of at risk population.

We did not include quasi experiments that could provide useful information on natural experiments with control groups. Our review yielded similar results to a recent systematic literature review that focused on multiple minority groups.13The investigatorsfrom that recent systematic literature review identified three RCT studies2,3,19that focused on Latino populations and validates our results.

This literature review provides initial evidence that culturally appropriate interventions that use promotoras, bilingual materials/classes, appropriate cultural diet, exercise modifications and establishing a social support network provide potentially efficacious strategies for improvement of cardiovascular risk factors among at risk Latinos. Further research must still be conducted to clarify the effectiveness of the different components included in behavioral interventions among at risk Latinos from different subgroups (e.g. Mexican American and Central Americans) and regions of the country. Overall, longer follow-up periods and additional controlled intervention trials need to be conducted to ascertain the optimal intervention strategies, cost-effectiveness, participant/system burden and health effects of behavioral and lifestyle interventions among at risk Latinos.

Figure 1.

Literature flow chart

Acknowledgements

Dr. Arab Lenore, Dr. Eryn Ujita Lee

Dr. Moreno received funding support from the NIA Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award (K23 AG042961-01), the American Federation for Aging Research (AFAR), NIA/NIH RCMAR/CHIME P30AG021684, and the content does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIA or the NIH.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: There is no financial conflict of interest for any authors with this manuscript

Omar Viramontes, Dallas Swendeman and Gerardo Moreno declare that they have no conflict of interest.

No animal or human studies were carried out by the authors for this article.

References

- 1.Dominguez K, Penman-Aguilar A, Chang MH. Vital signs: leading causes of death, prevalence of diseases and risk factors, and use of health services among Hispanics in the United States - 2009-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(17):496–478. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hayashi T, Farrell MA, Chaput LA, Rocha DA, Hernandez M. Lifestyle intervention, behavioral changes, and improvement in cardiovascular risk profiles in the California WISEWOMAN project. Journal of women's health. 2010;19(6):1129–1138. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balcazar HG, de Heer H, Rosenthal L, et al. A promotores de salud intervention to reduce cardiovascular disease risk in a high-risk Hispanic border population, 2005-2008. Preventing chronic disease. 2010;7(2):A28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poston WS, 2nd, Haddock CK, Olvera NE, et al. Evaluation of a culturally appropriate intervention to increase physical activity. Am J Health Behav. 2001;25(4):396–406. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.25.4.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sorlie PD, Backlund E, Johnson NJ, Rogot E. Mortality by Hispanic status in the United States. JAMA. 1993;270(20):2464–2468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aguila E, Escarce J, Leng M, Morales L. Health status and behavioral risk factors in older adult Mexicans and Mexican immigrants to the United States. J Aging Health. 2013;25(1):136–158. doi: 10.1177/0898264312468155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownstein JN, Bone LR, Dennison CR, Hill MN, Kim MT, Levine DM. Community health workers as interventionists in the prevention and control of heart disease and stroke. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29(5 Suppl 1):128–133. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eng E, Parker E, Harlan C. Lay health advisor intervention strategies: a continuum from natural helping to paraprofessional helping. Health education & behavior : the official publication of the Society for Public Health Education. 1997;24(4):413–417. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elder JP, Ayala GX, Campbell NR, et al. Interpersonal and print nutrition communication for a Spanish-dominant Latino population: Secretos de la Buena Vida. Health psychology: official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. 2005;24(1):49–57. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Staten LK, Scheu LL, Bronson D, Pena V, Elenes J. Pasos Adelante: the effectiveness of a community-based chronic disease prevention program. Preventing chronic disease. 2005;2(1):A18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Medina A, et al. Promotores de salud: educating Hispanic communities on heart-healthy living. Am J Health Educ. 2007;38(4):194–202. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verhagen I, Steunenberg B, de Wit NJ, Ros WJ. Community health worker interventions to improve access to health care services for older adults from ethnic minorities: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:497. doi: 10.1186/s12913-014-0497-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walton-Moss B, Samuel L, Nguyen TH, Commodore-Mensah Y, Hayat MJ, Szanton SL. Community-based cardiovascular health interventions in vulnerable populations: a systematic review. The Journal of cardiovascular nursing. 2014;29(4):293–307. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e31828e2995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uthman OA, Hartley L, Rees K, Taylor F, Ebrahim S, Clarke A. Multiple risk factor interventions for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in low- and middle- income countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;8:CD011163. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011163.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson KM, Wilson PW, Odell PM, Kannel WB. An updated coronary risk profile. A statement for health professionals. Circulation. 1991;83(1):356–362. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.1.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keller CS, Cantue A. Camina por Salud: walking in Mexican-American women. Applied nursing research : ANR. 2008;21(2):110–113. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lang TA, Seic M. How to Report Statistics in Medicine. 2nd ed. American College of Physicians; Philadelphia: 2006. Reporting systematic reviews and metanalyses. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Viswanathan M BN, Dryden DM, et al. Assessing the Risk of Bias of Individual Studies in Systematic Reviews of Health Care Interventions. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Methods Guide for Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. 2012 Mar; AHRQ Publication No.12-EHC047-EF. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balcazar HG, Byrd TL, Ortiz M, Tondapu SR, Chavez M. A randomized community intervention to improve hypertension control among Mexican Americans: using the promotoras de salud community outreach model. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2009;20(4):1079–1094. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moreno G, Mangione CM. Management of cardiovascular disease risk factors in older adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: 2002-2012 literature review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(11):2027–2037. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]