Abstract

Background:

Association between perceived social support and quality of life in hemodialysis patients represents a new area of interest.

Aim:

The aim of this study was to explore the effect of social support on the quality of life of hemodialysis patients.

Material and Methods:

In this study 258 hemodialysis patients were enrolled. Data was collected using a questionnaire which consisted of three parts: a) the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) to assess perceived social support, b) the Missoula-VITAS Quality of Life Index (MVQOLI–15) to assess quality of patients’ life and c) the socio-demographic, clinical and other variables of patients. To test the existence of association between quality of life and social support the correlation coefficient of Spearman was used. Multiple linear regression was performed to estimate the effect of social support on quality of life (dependent variable), adjusted for potential confounders. The analysis was performed on SPSS v20.

Results:

Patients felt high support from significant others and family and less from friends (median 6, 6 and 4.5 respectively). Patients evaluated their quality of life in its entirety as moderate in the total and “overall quality of life” score (median 17.2 and 3 respectively). Regarding the association between social support and quality of life, results showed that the more support patients had from their significant others, family and friends, the better quality of life they had. (rho =0,395, rho =0,399 and rho=0,359, respectively).

Conclusions:

Understanding the relation between social support and quality of life should prompt health professionals to provide beneficial care to hemodialysis patients.

Keywords: celiac disease, gluten enteropathy, epidemiology, incidence, prevalence, Bosnia and Herzegovina, hemodialysis, social support, quality of life

1. INTRODUCTION

Globally, chronic kidney disease (CKD) consists a major public health problem, expanding at an alarming rate (1, 2). For instance, 1.500.000 individuals were undergoing hemodialysis in 2013, worldwide (1). The prevalence of disease is growing due to the increased incidence of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, obesity and aging of population (3). At the same time, there is noticed a geographical or cultural variety in disease prevalence (4). Hemodialysis as the most common treatment method for renal failure imposes a considerable burden not only on patients and their families but also on the National Health System of each country (1-4). During last decades, health related quality of life (HRQOL) has been held as a valuable measurement in daily clinical practice that may reflect the outcome of the disease or the effectiveness of therapy (5). More intriguing, measurement of HRQOL in patients with CKD is a strong predictor of mortality (6) or re-hospitalizations (7).

Strategies to improve the HRQOL of patients will markedly decrease the economic, medical, individual and social burden of the disease (8). A key element in achieving better quality of life is to support hemodialysis patients (9). Social support consist a modifiable psychosocial factor that is associated with hemodialysis patients’ perception of quality of life (10) and significantly more, with their survival (11).

According to patients’ reports, they mainly desire psychological, social, and spiritual support (1) while the needs for support are associated with age, education level, place of residence, difficulties in relations with family members and anxious personality (12). However, the needs for social support vary among patients undergoing hemodialysis that is mainly attributed either to the quality and quantity of their social network or to the severity of the disease (11).

The aim of the present study was to explore the effect of perceived social support on the quality of life of hemodialysis patients.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

The sample of the study consisted of 258 patients undergoing hemodialysis in dialysis centers from February 2015 to May 2015. This sample was a convenience sample. Criteria for inclusion of patients in the study were: a) diagnosis of End Stage Renal Disease, b) current hemodialysis, c) native language -Greek, and d) volunteer participation.

All subjects had been informed of their rights to refuse or discontinue participation in the study, according to the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki (1989) of the World Medical Association. Ethical permission for the study was obtained by the Medical Research Ethics Committee of each dialysis center. Data collection was performed by the method of the interview using a questionnaire developed by the researchers so as to fully serve the purposes of the study. The data collected for each patient included: socio-demographic characteristics (gender, age, education level, marital status), clinical characteristics (years from first hemodialysis session, other disease), therapy characteristics (adherence to treatment guidelines), and difficulties with environment (family, social). The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support questionnaire (MSPSS) was used to evaluate social support of the patients. This scale has been translated and culturally adapted to the Greek standards (13, 14). It assesses three dimensions of social support: support from significant others, family and friends. The questions of each dimension expressing “support” are rated at a 7-point Likert scale from 1 to 7. In order to calculate the final score of each dimension of social support, we add the scores of questions corresponding to each dimension and divide by the number of questions included in each dimension. These scores reflect the level of support felt by the patients. Higher levels indicate higher support.

To evaluate the quality of life of patients the scale Missoula-VITAS Quality of Life Index (MVQOLI-15) was used. This scale has been translated and culturally adapted to the Greek standards (15, 16). This scale assesses five dimensions of quality of life of patients: “symptoms”, “functionality”, “interpersonal relationships”, “well-being” and “transcendent”. For each dimension, three types of information are collected: (a) assessment (subjective measurement of the actual situation) (b) satisfaction (degree of acceptance of the actual situation) and (c) importance (the extent to which this aspect affects the actual quality of life). The questions of each dimension expressing the “assessment” are rated at a 5-point Likert scale from -2 to 2. The questions expressing “satisfaction” are rated from -4 to 4 and questions which express the “importance” are rated from 1 to 5. To calculate the total score for each dimension of quality of life, we add the scores of “assessment” and “satisfaction” and then multiply this sum by the degree of “importance” (assessment + satisfaction) x importance). The score of each dimension reflects the extent that this dimension affects patients’ quality of life. Higher total scores indicate better quality of life.

Categorical variables are presented by absolute and relative frequencies (percentages), and quantitative variables are presented by median and interquartile range since they do not follow the normal distribution (tested with kolmogorov- smirnof test). To test the existence of association between quality of life and social support the correlation coefficient of Spearman was used. Multiple linear regression was performed to estimate the effect of social support on quality of life (dependent variable), adjusted for potential confounders. The results are presented with beta coefficients and 95% confidence interval. The level of statistical significance was set to a=5%. The analysis was performed with the statistical package SPSS, version 20 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Il, USA).

The study sample was not representative of hemodialysis patients in Greece, but a convenience sample. The relevant sampling method limits the generalizability of results. Also, the study was cross-sectional thus not allowing the causal relation between quality of life and perceived social support.

3. RESULTS

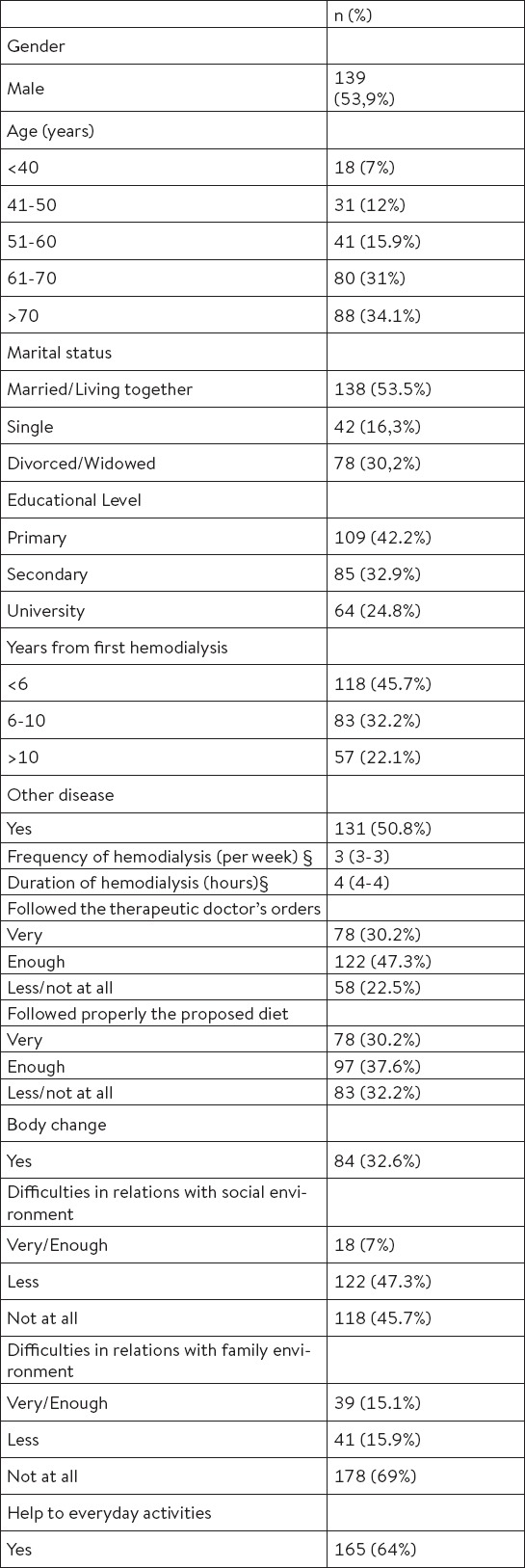

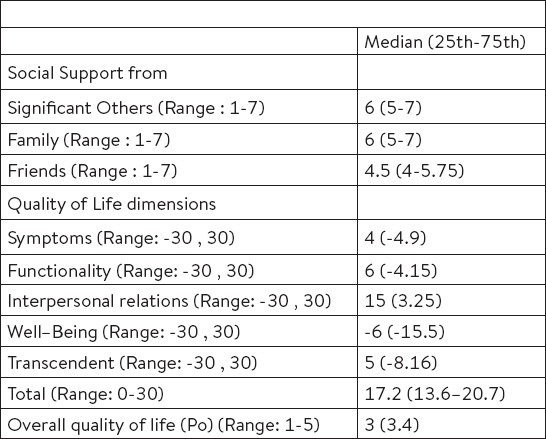

Characteristics of patients are shown in Table 1. From Table 2 we conclude that patients felt highly supported from their significant others and their family (median 6 for both subscales) and less from their friends (median 4.5, neutral support levels). Furthermore, patients had an increased score in “interpersonal relationships” meaning that did not face particular problems in this dimension (Median 15).

Table 1.

Patients characteristics (N=258)

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for social support and quality of life of patients undergoing hemodialysis (N=258)

They had moderate scores in the dimensions: “symptoms”, “functionality” and “transcendent” (median 4. 6 and 5 respectively) and a very low score in the dimension “well-being” (median -6) meaning that these dimensions are the most affected. Patients considered their quality of life in its entirety as moderate in the “total” and “overall quality of life” score (median 17.2 and 3, respectively) (Table 2).

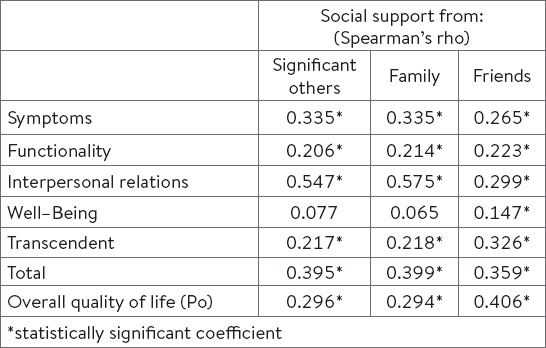

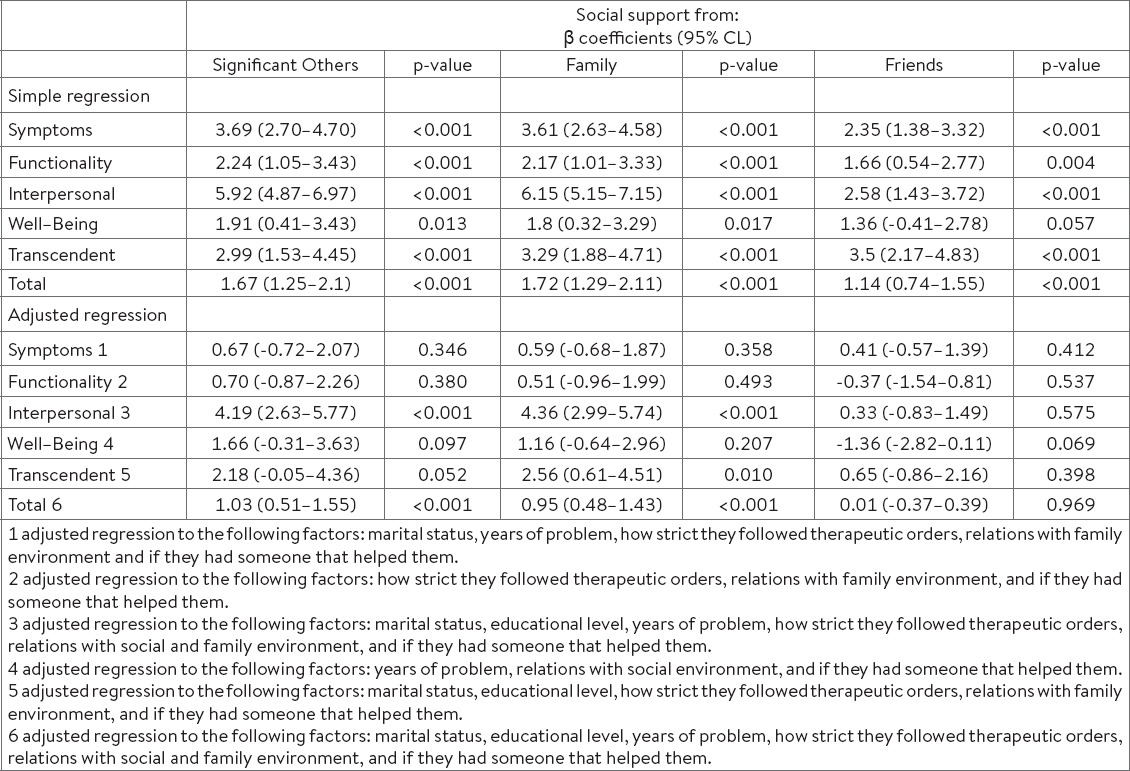

Almost all correlation coefficients were statistically significant, but none was high enough (Table 3). More specifically, high correlation coefficients were observed between dimension “symptoms” and social support from significant others and family (rho=0.335 and rho=0.335, respectively) as well as between the dimension “interpersonal relations” and social support from significant others and family (rho= 0.547 and rho=0.575, respectively). All four of these coefficients indicated a positive correlation, meaning that as support from significant others and family was increased then the levels of quality of life associated with “symptoms” and “interpersonal relationships” also were increased. Moreover, social support from friends was associated with the “transcendent” and the “overall quality of life” (rho=0.326 and rho=0.406, respectively). Specifically, when support from friends was increased, then the levels of quality of life associated with “transcendent” and the “overall quality” of life also increased. Finally, with regard to the “overall” score of quality of life, it was associated with all three subscales of social support (rho=0.395, rho=0.399 and rho=0.359, respectively). The more support the patients had from their significant others, family and friends, the better levels of quality of life they had. Multiple linear regression was performed in order to estimate the effect of social support on the quality of life (dependent variable), adjusted for potential confounders. From Table 4 we conclude that there was a statistically significant effect of social support on all subscales of quality of life and on the overall quality. Except for the effect of the support from friends in “well-being” (non significant effect). More specifically, one point increase of support (either from significant others, either from family or friends) entails increase of total quality of life levels by 1.67 1.72 and 1.14 points respectively, and better quality of life levels in all the sub-dimensions (see b coefficients in Table 4).

Table 3.

Association between Social Support and Quality of hemodialysis patients (N=258)

Table 4.

Effect of social support on quality of life of hemodialysis patients (N=258)

After adjustment for potential confounding factors in the effect of social support to quality of life (Table 4) we conclude that there were confounding factors in the relationship between social support and quality of life, since many of the coefficients did not remain significant. Specifically, statistically significant effect of social support from significant others and family after adjustment for confounders, we had on “interpersonal relationships” and “overall quality of life” (p=<0.001 and p=<0.001). More particularly, when the social support from significant others and family was increased by one point, then the quality of life levels associated with “interpersonal relationships” was also increased by 4.19 and 4.36 points, respectively and the “overall quality of life” was increased by 1.03 and 0.95 points, respectively. In addition, statistically significant effect of social support from the family we had on “transcendent” (p=0.010) and more particularly when social support from family was increased by one point, then the quality of life associated with “transcendent” was also increased by 2.56 points.

4. DISCUSSION

The results of the present study revealed that the more support patients had the better quality of life they had.

This association is well established in several other studies (17, 18, 19). On the contrary, poor social support is associated with higher mortality risk, lower adherence to treatment regimen and poor physical quality of life in End Stage Renal Disease (20). Poor support is attributed to nature and chronicity of the disease which limit social integration (21).

On the basis of the present findings, a key challenge confronting health care professionals is to deeply understand the relation between social support and quality of life in hemodialysis patients and consequently to provide care of high quality through applying individualized programs. Social support is linked directly and indirectly with improvements in hemodialysis patients’ quality of life.

Possibly in direct way, social support improves quality of life through various mechanisms such as increasing patients’ satisfaction from the provided care, enhancing adherence to the therapeutic regimen including diet and fluid restrictions, thus improving laboratory results (lower phosphorus and potassium) or leading to better clinical outcomes (24, 25). Also of importance is the acknowledgement that high social support is associated with approximately 15% decreased risk for hospital admission. Interestingly, many hospitalizations of hemodialysis patients could have been avoided or treated in clinical out settings if they were early recognized by a supportive social network that enhances treatment-seeking behavior. In the light of these results, increasing support is obviously one of the most effective ways to decrease hospitalization-associated costs (25). Another significant area related to this association is that a supportive environment provides a frame within patients may express their feelings and find solutions to the stressful treatment aspects. Indeed, an encouraging environment will help hemodialysis patients to adopt a more positive attitude towards the disease including improvement in their coping mechanisms (1.26). Positive coping strategy is essential when confronting with the prolonged duration of the disease and its’ accompanying problems (27). In accordance with the present study, family support is indicated as the most important one (28). Family members play an increasingly vital role in improving self-care behaviours and facilitating patients’ adjustment to illness (29). Support by spouses can be a source of strength whereas support from friends is significant to retired hemodialysis individuals (19). However, it is intriguing to ascertain the critical role of family since living within an extended family is associated with poor quality of life (30). Equally important, is the support provided by health care professionals since it improves the way hemodialysis patients perceive their health (31). Socio-demographic characteristics may partially explain the association between support and quality of life in hemodialysis patients. For instance, age seems to play an important role in this association as younger patients tend to be healthier thus enjoying higher levels of social support compared to those of advanced age who may perceive themselves as a burden to others (20). Furthermore, absence of difficulties within social and family environment or non-concealment of the disease are social characteristics that increase the average quality of life in hemodialysis patients (32). Though several theories may be suggested in an effort to explain this association, it seems that social support is up to some extent necessary for patients undergoing hemodialysis. It is widely accepted that these patients face with various needs (clinical or psychosocial) and difficulties in daily activities as well as with other co-morbidities. It is worth mentioning that in the present study 64% reported to have someone else helping with everyday activities while in 50.8% co-existed some other disease. Due to the progress of the disuse, in-depth knowledge of both social support and quality of life acquire evaluation on the onset of hemodialysis and regularly scheduled (7, 20).

However, discrepancies in levels of support or quality of life noticed in literature are attributed to several reasons such as variety in methodology including use of several instruments and small sample sizes as well as to disparities in the management of the disease. This observation creates the demand for a world-wide accepted standard to measure support and quality of life. Finally, it becomes apparent that focuses on strengthening support, is strongly recommended. This interesting possibility is supported by the finding that 69% and 45.7% of the participants reported having “not at all” difficulties in relations with family environment and social environment, respectively.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Hemodialysis is a time consuming procedure that imposes to patients a strict treatment schedule. Apart from medical treatment, the key factor in performing high-quality holistic caring programs to hemodialysis patients is assessing support and quality of life. It is a matter of crucial importance for health professionals to expand their understanding of promoting social support in hemodialysis patients. There is a paucity of research addressing the association between social support and quality of life in dialysis patients. Future directions for research are suggested in this important area.

Acknowledgments:

• We thank patients of the dialysis center: Iatriko Therapeutirio Iliou, Athens, Greece.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shahgholian N, Yousefi H. Supporting hemodialysis patients: A phenomenological study. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2015;20(5):626–33. doi: 10.4103/1735-9066.164514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Okpechi IG, Nthite T, Swanepoel CR. Health-related quality of life in patients on hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2013;24(3):519–26. doi: 10.4103/1319-2442.111036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ayodele OE, Alebiosu CO. Burden of chronic kidney disease: an international perspective. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2010;17(3):215–24. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alebiosu CO, Ayodele OE. The global burden of chronic kidney disease and the way forward. Ethn Dis. 2005;15:418–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rebollo P, Ortega F. New trends on health related quality of life assessment in end-stage renal disease patients. Int Urol Nephrol. 2002;33(1):195–202. doi: 10.1023/a:1014419122558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spiegel BM, Melmed G, Robbins S, Esrailian E. Biomarkers and health-related quality of life in end-stage renal disease: a systematic review. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(6):1759–68. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00820208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Avramovic M, Stefanovic V. Health-related quality of life in different stages of renal failure. Artif Organs. 2012;36(7):581–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2011.01429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finkelstein FO, Arsenault KL, Taveras A, Awuah K, Finkelstein SH. Assessing and improving the health-related quality of life of patients with ESRD. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2012;8(12):718–24. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2012.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Niu SF, Li IC. Quality of life of patients having renal replacement therapy. J Adv Nurs. 2005;51(1):15–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen SD, Sharma T, Acquaviva K, Peterson RA, Patel SS, Kimmel PL. Social support and chronic kidney disease: an update. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2007;14(4):335–44. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thong MS, Kaptein AA, Krediet RT, Boeschoten EW, Dekker FW. Social support predicts survival in dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:845–50. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xhulia D, Gerta J, Dajana Z, Koutelekos I, Vasilopoulou C, Skopelitou M, et al. Needs of hemodialysis patients and factors affecting them. Glob J Health Sci. 2015;8(5):51767. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v8n6p109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Theofilou P. The relation of social support to mental health and locus of control in chronic kidney disease. J Renal Nurs. 2012;4:18–22. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Theofilou P, Zyga S, Tzitzikos G, Malindretos P, Kotrotsiou E. Chronic kidney disease: signs/symptoms, management options and potential complications. New York: Nova Publishers; 2013. Assessing social support in Greek patients on maintenance hemodialysis: psychometric properties of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support”; pp. 265–279. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Theofilou P, Kapsalis F, Panagiotaki H. Greek version of MVQOLI–15: Translation and cultural adaptation. International Journal of Caring Sciences. 2012;5(3):289–294. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Theofilou P. Translation and cultural adaptation of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) for Greece. Health Psychology Research. 2015;3(1):45–7. doi: 10.4081/hpr.2015.1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rambod M, Rafii F. Perceived social support and quality of life in Iranian hemodialysis patients. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2010;42(3):242–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2010.01353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel SS, Peterson RA, Kimmel PL. The impact of social support on end stage renal disease. Semin Dial. 2005;18(2):98–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2005.18203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tel H, Tel H. Quality of life and social support in hemodialysis patients. Pak J Med Sci. 2011;27(1):64–7. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Untas A, Thumma J, Rascle N, Rayner H, Mapes D, Lopes AA, et al. The associations of social support and other psychosocial factors with mortality and quality of life in the dialysis outcomes and practice patterns study. Clinical Journal America Social Nephrology. 2010;5:11–21. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02340310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahrari S, Moshki M, Bahrami M. The relation between social support and adherence of dietary and fluids restrictions among hemodialysis patients in Iran. J Car Sci. 2014;3(1):11–9. doi: 10.5681/jcs.2014.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Helgeson VS. Social support and quality of life. Qual Life Res. 2003;12(Suppl 1):25–31. doi: 10.1023/a:1023509117524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kara B, Caglar K, Kilic S. Nonadherence with diet and fluid restrictions and perceived social support in patients receiving hemodialysis. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2007;39:243–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2007.00175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shahnaz Ahrari, Mahdi Moshki, Mahnaz Bahrami. The relationship between social support and adherence of dietary and fluids restrictions among hemodialysis patients in Iran. J Caring Sci. 2014;3(1):11–9. doi: 10.5681/jcs.2014.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Plantinga LC, Fink NE, Harrington-Levey R, et al. Association of Social Support with Outcomes in Incident Dialysis Patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(8):1480–8. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01240210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Al Nazly E, Ahmad M, Musil C, Nabolsi M. Hemodialysis stressors and coping strategies among Jordanian patients on hemodialysis: A qualitative study. Nephrol Nurs J. 2013;40:321–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahmad MM, Al Nazly EK. Hemodialysis: stressors and coping strategies. Psychol Health Med. 2015;20(4):477–87. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2014.952239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bayat A, Kazemi R, Toghiani A, Mohebi B, Tabatabaee MN, Adibi N. Psychological evaluation in hemodialysis patients. J Pak Med Assoc. 2012;62(3 Suppl 2):S1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alnazly E. Coping strategies and socio-demographic characteristics among Jordanian caregivers of patients receiving hemodialysis. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2016;27(1):101–6. doi: 10.4103/1319-2442.174088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tel H. Determining quality of life and sleep in hemodialysis patients. Dial Transplant. 2009;38(6):210–5. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neri L, Brancaccio D, Rocca Rey LA, Rossa F, Martini A, et al. Social support from health care providers is associated with reduced illness intrusiveness in hemodialysis patients. Clin Nephrol. 2011;75(2):125–34. doi: 10.5414/cnp75125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vasilopoulou C, Bourtsi E, Giaple S, Koutelekos I, Theofilou P, Polikandrioti M. The Impact of anxiety and depression on the quality of life of hemodialysis patients. Glob J Health Sci. 2015;8(1):45–55. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v8n1p45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]