Abstract

Background

The attempt to induce oral tolerance as a treatment for food allergy has been hampered by a lack of sustained clinical protection. Immunotherapy by non-oral routes, such as the skin, may be more effective for the development of maintained tolerance to food allergens.

Objective

To determine the efficacy and mechanism of tolerance induced by epicutaneous immunotherapy in a model of food-induced anaphylaxis.

Methods

C3H/HeJ mice were sensitized to ovalbumin (OVA) orally or through the skin and treated with EPIT using OVA-Viaskin® patches or OIT using OVA. Mice were orally challenged with OVA to induce anaphylaxis. Antigen-specific Treg induction was assessed by flow cytometry using a transgenic T cell transfer model.

Results

Using an adjuvant-free model of food allergy generated by epicutaneous sensitization and reactions triggered by oral allergen challenge, we found that epicutaneous immunotherapy induced sustained protection against anaphylaxis. We show that the gastrointestinal tract is deficient in de novo generation of Tregs in allergic mice. This defect was tissue-specific, and epicutaneous application of antigen generated a population of gastrointestinal-homing LAP+Foxp3− Tregs. The mechanism of protection was found to be a novel pathway of direct TGF-β-dependent Treg suppression of mast cell activation, in the absence of modulation of T or B cell responses.

Conclusions

Our data highlights the immune communication between skin and gastrointestinal tract, and identifies novel mechanisms by which epicutaneous tolerance can suppress food-induced anaphylaxis.

Keywords: Epicutaneous immunotherapy, oral immunotherapy, food allergy, regulatory T cells, mast cells

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Food allergies are increasing in Western countries and are currently estimated to affect 3–6% of the population1. There is no cure, and the standard of care is allergen avoidance, which is difficult to maintain and accidental exposures leading to reactions are a common experience for those with food allergies2. Subcutaneous allergen immunotherapy has been extensively used for venom allergy and some respiratory allergies. However, its use in food allergy has not been pursued due to the high risk of anaphylactic shock3. Allergen immunotherapy delivered by the oral route (oral immunotherapy, OIT) has been the focus of several recent trials 4, 5. It was thought that the oral route, in addition to being safer than subcutaneous immunotherapy, would facilitate sustained immune tolerance due to the regulatory tone of the mucosal immune system. While OIT successfully induces a desensitized state, defined as protection while on therapy, permanent tolerance induction after OIT has been more elusive 4, 6–8.

Oral tolerance is a state of systemic unresponsiveness induced by antigens delivered by oral route. It is an active process mediated by antigen-specific regulatory T cells 9, 10. The therapeutic potential of oral tolerance has been studied for multiple sclerosis 11, arthritis 12, diabetes 13 and colitis 14. The translation of oral tolerance from prevention to treatment strategy has been limited, suggesting that prior immunity may impair the development of regulatory responses. This is consistent with the lack of sustained tolerance in response to OIT in human trials 4, 6, 8 and in mouse models of OIT 15, 16.

We hypothesized that an altered gastrointestinal immune milieu in food allergy was preventing the generation of Tregs, and that provision of antigen by an alternative route could bypass this defective regulatory response. The skin is a highly active immune site capable of generating tolerance or immunity. We investigated the epicutaneous route through the use of Viaskin® patches that have been shown to suppress inflammation in experimental models of asthma and eosinophilic esophagitis through the generation of regulatory T cells 17–21. We show for the first time that the epicutaneous route of antigen delivery protected mice from food-induced anaphylaxis and supported the selective expansion of a population of unique gut-homing LAP+ Tregs. These Tregs did not function by suppressing IgE antibodies, but instead directly suppressed mast cell activation, leading to sustained clinical protection against food-induced anaphylaxis. These data show that the unique immune communication between skin and gastrointestinal tract can be used to generate long term tolerance in food allergy.

Methods

Mice

C3H/HeJ and Balb/c mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) and NCI (Frederick, MD), respectively. DO11.10 mice (Jackson Laboratories) were maintained as breeding colonies at Mount Sinai. All procedures were approved by the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Sensitization of mice

Mice were sensitized once a week for 6 weeks with ovalbumin (OVA, grade V; Sigma, St Louis, MO) or peanut by epicutaneous or oral exposure. For skin sensitization, abdominal fur was removed with depilatory cream (Veet; Reckitt Benckiser, Parsippany, NJ), immediately followed by application of 100ug OVA or 1mg of peanut extract in 50ul of PBS spread on the skin to dry. Epicutaneous sensitization was performed in the absence of adjuvant or tape stripping. Mice were orally sensitized with 1mg of OVA or 10mg of ground peanut + 10ug of cholera toxin (CT) (List Biologicals, Campbell, CA) by gavage. Mice were passively sensitized by injection with 100ul of pooled serum from actively sensitized mice. Oral challenge was performed as previously described 15. See Supplemental Materials for additional information.

Immunotherapy treatment

After sensitization, mice received epicutaneous or oral immunotherapy. Epicutaneous immunotherapy was performed using EDS Viaskin® patches (DBV Technologies, Paris, France) loaded with 100ug OVA, as previously described 18. Briefly, mice were anesthetized, the back shaved with an electric clipper, depilatory cream applied, and 24h later the patch was placed on the back for 48h. This was repeated once per week for 8 weeks. Oral immunotherapy was performed by the administration of 1mg of OVA per day, in drinking water, daily, for 8 weeks.

Adoptive cell transfer experiments

CD4+ T cells from DO11.10 mice were purified by negative selection (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada), labeled with CFSE (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) and 3–5 × 106 CD4+ Tcells transferred i.v. into naïve, OVA-sensitized, or peanut-sensitized Balb/c recipients. Twenty-four hours later, mice were exposed to OVA by OVA-Viaskin® for 48h, or by daily gavage for 5 days. One week after first exposure, tissues were harvested for assessment by flow cytometry.

TGFβ blockade

EPIT-treated mice were injected intraperitoneally with neutralizing anti-TFGβ (1D11) (1mg) or isotype control (both from BioXCell, West Lebanon, NH) 24h before challenge.

In vivo Treg transfer

LAP+CD25− or LAP−CD25− T cells were sorted from DO11.10 mice and transferred (105 cells/mouse) into passively sensitized Balb/c mice. After 24h, recipient mice were orally challenged with OVA. Symptoms were monitored and blood samples were obtained 30 min after challenge. In some experiments, 1mg of anti-TGFβ antibody was injected at the same time as the cells.

Serum MCPT-7 ELISA

For detection of MCPT-7, serum was incubated on plates covered with anti-mTryptase β-1/MCPT7 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), followed by detection with biotinylated anti-mTryptase β-1 (R&D systems), HRP-labeled avidin (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) and TMB substrate (eBioscience).

Statistics

Differences between groups were analyzed by Mann-Whitney U test, ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis test followed by post-hoc analysis with the Dunn’s, Sidak’s or Tukey’s multiple comparisons test or by multiple t test with Sidak-Bonferroni method for correction of multiple comparisons when appropriate. Data analysis was done by using Prism software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. A value of p<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Epicutaneous immunotherapy induces sustained clinical protection in a model of food-induced anaphylaxis

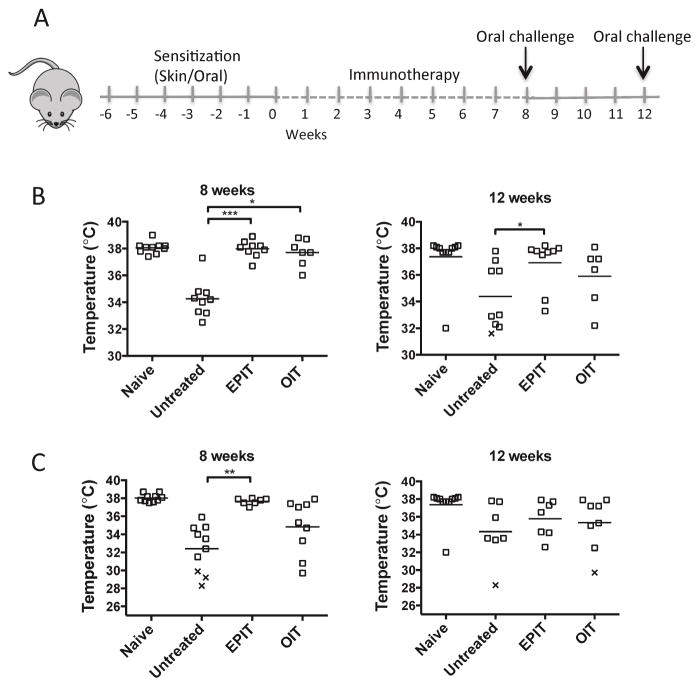

A lack of permanent tolerance to foods after OIT has been described in both mouse and human studies. We studied the outcome of EPIT and OIT in a model of oral OVA-induced anaphylaxis. To determine if the route of primary sensitization was a factor in the outcome of immunotherapy, we used mice that had been sensitized to OVA through either epicutaneous or oral routes, followed by 8 weeks of EPIT or OIT (Fig 1, A). At the end of the treatment, mice were orally challenged with OVA and anaphylaxis measured by drop in body temperature. Mice sensitized by the epicutaneous route developed anaphylaxis upon oral challenge with OVA, while mice subjected to EPIT or OIT were completely protected (Fig 1, B). When mice were challenged again to test sustained protection after 4 weeks without treatment, mice treated with EPIT were still significantly protected against anaphylaxis while mice treated with OIT regained clinical reactivity. However, there was no statistical difference between OIT and EPIT treated groups at the 12 week time-point. In mice orally sensitized to OVA using cholera toxin adjuvant, mice treated with EPIT were completely protected from anaphylaxis (Fig 1, C) but mice treated with OIT were not protected. However, 4 weeks later, even EPIT-treated mice lost protection against anaphylaxis (Fig 1, C). We hypothesized that this difference in outcome between mice sensitized by the oral or epicutaneous routes could be due to exogenous adjuvant (cholera toxin) needed during oral sensitization. To test that, mice were sensitized by the epicutaneous route using cholera toxin adjuvant and then subjected to EPIT. Similar to the response to EPIT in orally sensitized mice, mice sensitized by the epicutaneous route with exogenous adjuvant were protected from anaphylaxis while on EPIT therapy but not after termination of EPIT (Fig E1). Our results show that independent of the primary route of sensitization, EPIT led to a robust clinical protection against food-induced anaphylaxis.

Figure 1. EPIT induces sustained protection against food-induced anaphylaxis.

(A) Experimental schematic. (B) Oral challenge with OVA in skin-sensitized mice at weeks 8 and 12. Body temperature 30 min after challenge is shown. (C) Oral challenge with OVA in orally-sensitized mice at weeks 8 and 12. Data are individual mice from 2 independent experiments. x = death. * p < 0.05, **p<0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Blood samples were taken to quantify specific immunoglobulins and basophil activation. There was a significant increase in OVA-specific IgG1 and IgG2a after 8 weeks of EPIT (Fig 2, A), that persisted in skin-sensitized mice at week 12. IgE levels also increased during the treatment but remained stable after 12 weeks. Despite these changes in immunoglobulin levels, functional assays did not support a role for antibodies in clinical protection after EPIT. Basophil activation tests showed no significant difference between untreated and EPIT-treated mice (Fig 2, B). Secondly, passive sensitization of naïve mice with sera from untreated or EPIT-treated mice generated similar degrees of anaphylaxis after recipient mice were orally challenged (Fig 2, C). These results suggest that although EPIT modified the humoral response to OVA, the protection against anaphylaxis was likely mediated by a mechanism other than blocking antibodies.

Figure 2. OVA-specific IgG1 and IgG2a generated during EPIT do not modify basophil reactivity or protect against anaphylaxis.

(A) IgE, IgG1 and IgG2a levels in serum prior to oral challenge from skin- or orally-sensitized mice at week 8 and 12 after EPIT or OIT. Data are mean ± SEM. (B) OVA-induced basophil activation measured by upregulation of CD200R. (C) Oral challenge of mice were passively sensitized with sera from naïve, untreated or EPIT-treated mice. Data show individual mice from 2 independent experiments. *p < 0.05 vs untreated mice.

Expansion of Tregs by oral antigen is impaired in allergic mice

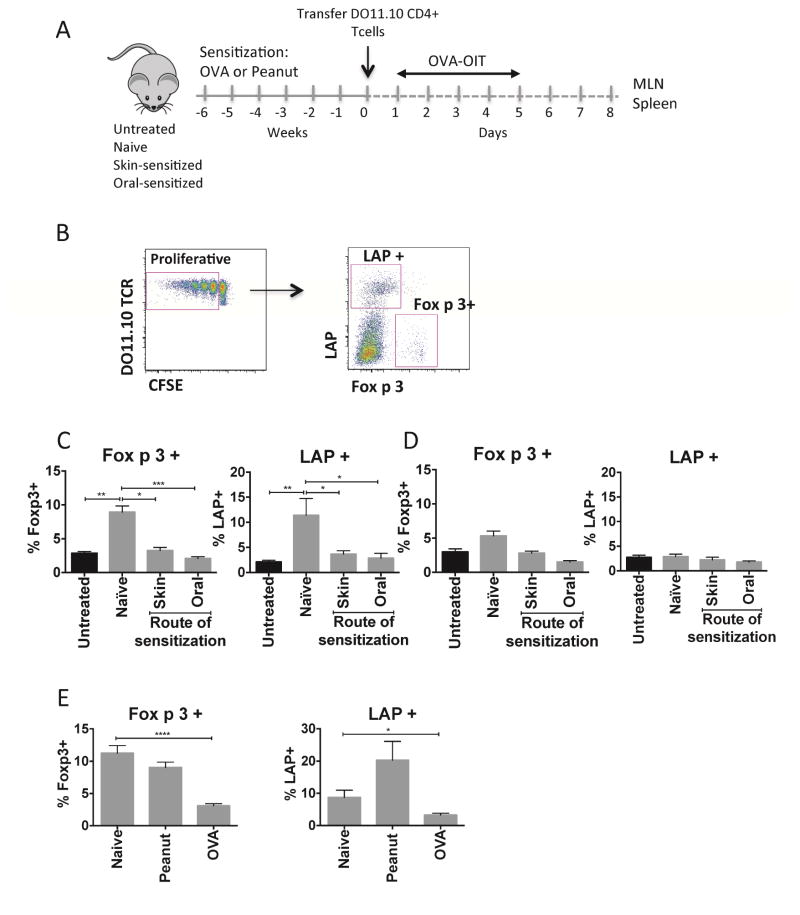

We hypothesized that the altered gut immune environment in food allergy is poorly tolerogenic and the lack of maintained clinical tolerance after oral immunotherapy is related with defect in Treg generation in the gut when antigen is applied orally. To study the response to immunotherapy of antigen-specific Tregs in the gastrointestinal tract of allergic mice, we used an adoptive transfer model. CFSE-labeled CD4+ T cells from DO11.10 transgenic mice (recognizing the 323–339 epitope of the egg allergen ovalbumin (OVA)) were transferred to naïve or OVA-sensitized recipient mice prior to repeated low-dose feeding with OVA (Fig 3, A). We quantified the expansion of Foxp3+ cells and LAP+ cells within proliferating cells (Fig 3, B). After 5 days of oral antigen, there was an expansion of both Foxp3+ and LAP+ antigen-specific Treg populations in MLN of naïve mice (Fig 3, C), consistent with induction of a tolerance response. LAP+ T cells in the proliferating compartment did not express CD25, while non-transgenic LAP+ T cells found within the MLN were found to be either negative or positive for CD25. We confirmed in suppression assays that LAP+ T cells had regulatory activity similar to LAP−CD25+ Tregs independent of the expression of CD25 (Fig E2). The expansion of Tregs after oral antigen was observed in MLN but not in distal sites such as spleen (Fig 3, D). By contrast, in mice that were OVA-sensitized prior to T cell transfer and OVA feeding, the expansion of Foxp3+ and LAP+ Tregs was completely abrogated (Fig 3, C). The defect in Treg generation after oral antigen feeding was observed in mice sensitized by either the oral or the epicutaneous routes and therefore is a feature of the allergic state. When mice were sensitized to a bystander antigen (peanut), the generation of OVA-specific Tregs was not impaired, demonstrating the antigen specificity of this Treg defect (Fig 3, E).

Figure 3. Impact of sensitization on Treg generation by oral antigen.

(A) Experimental schematic. (B) Gating strategy of OVA-specific Tregs. (C,D) Foxp3+ and LAP+ T cells generated in MLN (C) and spleen (D) of mice sensitized to OVA by the oral or skin route versus naive. (E) Foxp3+ and LAP+ T cells in MLN from naïve, OVA-sensitized mice or peanut-sensitized mice. Data are mean + SEM of at least 5 mice/group in 2 independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p<0.0001.

Epicutaneous immunotherapy expands LAP+ Tregs in the gastrointestinal tract of allergic mice

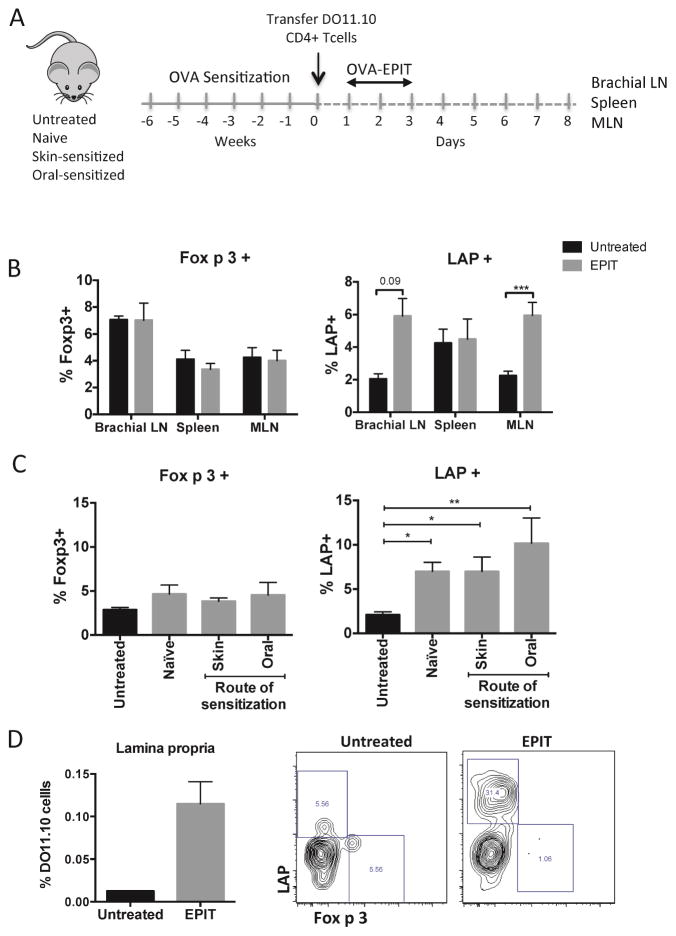

Based on the results of the anaphylaxis model, we hypothesized that antigen delivered via the skin could induce Tregs in sensitized mice. We first examined the induction of antigen-specific Tregs in the skin-draining lymph nodes. There was an increase in proliferating LAP+ but not Foxp3+ Tregs in comparison with untreated mice in brachial lymph nodes 1 week after applying antigen (Fig 4, B). As with oral exposure, there was no selective expansion of Tregs in the spleen after epicutaneous OVA. Unexpectedly, there was a significant expansion of LAP+ Tregs in the MLN of mice after epicutaneous OVA (Fig 4, B). Furthermore, this expansion of LAP+ Tregs in the MLN was not impaired in mice sensitized by either the oral or skin routes (Fig 4, C). There was also an increased frequency of DO11.10 cells in the small intestinal lamina propria after epicutaneous OVA, which were highly enriched in LAP+ Tregs (Fig 4, D). This was selective to the gastrointestinal tissues, as other non-draining lymph nodes (inguinal lymph nodes) demonstrated no expansion of LAP+ Tregs (data not shown). These data demonstrate that epicutaneous antigen exposure can result in the appearance of Tregs in the gastrointestinal tract, and this is observed in naïve mice and also allergic mice that have impaired Treg generation in response to oral antigen exposure.

Figure 4. Epicutaneous antigen expands LAP+ T cells in skin and gastrointestinal lymph nodes.

(A) Experimental schematic. (B) Foxp3+ and LAP+ T cells in skin-draining lymph nodes, MLN and spleen of naïve mice. (C) Foxp3+ and LAP+ T cells in MLN of mice sensitized by the oral or skin route versus naive. (D) OVA-specific cells in lamina propria after EPIT. Data are mean + SEM of at least 6 mice/group (3 mice/group for lamina propria) in two independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

LAP+ T cells are primed for gut homing in skin-draining lymph nodes

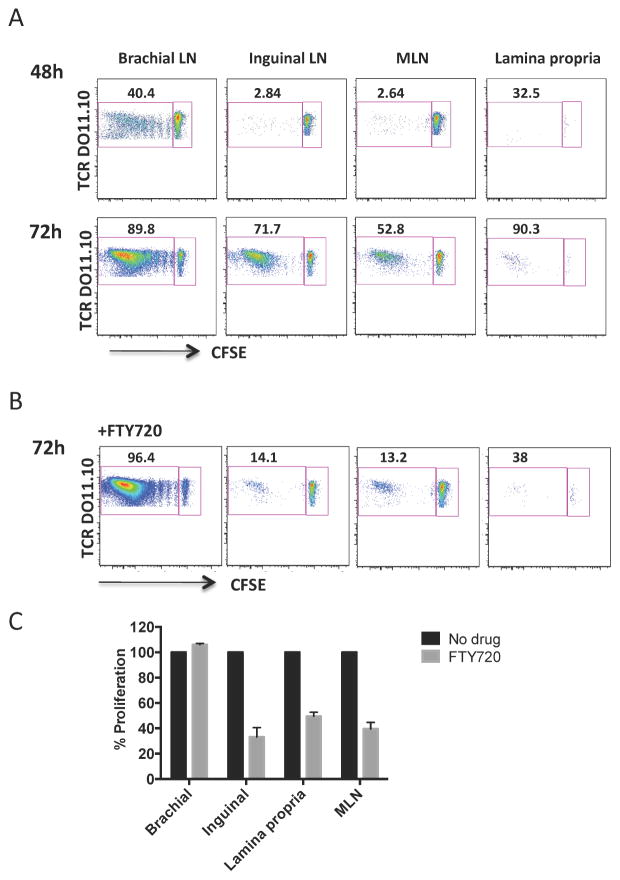

Tissue homing normally reflects the site of priming, such that T cells primed in skin-draining lymph nodes home back to the skin, and T cells primed in the mesenteric lymph nodes home back to the lamina propria. We therefore asked how epicutaneous antigen could induce LAP+ T cells to appear selectively in the MLN. We first examined kinetics of cell proliferation at different sites. Two days after patch placement only brachial lymph nodes showed evidence of T cell proliferation (Fig 5, A). After 3 days, CFSE-low cells began to appear in inguinal and mesenteric lymph nodes and in the small intestinal lamina propria. Mice that had received DO11.10 T cells but did not received antigen stimulation had a low frequency of CFSE-high cells in the absence of CFSE-low cells at each of the sites examined. To determine if the appearance of CFSE-low T cells at distal sites was due to migration of cells primed in brachial lymph nodes or due to transport of antigen to distal sites, we treated mice with FTY720, a sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor agonist that prevents exit of T cells from lymph nodes. Cells were recovered 3 days after patch application. The percentage of CFSE-low cells was decreased by FTY720 treatment in inguinal and mesenteric lymph nodes and the small intestinal lamina propria (Fig 5, B and 5, C), while proliferation of cells in the brachial lymph node was unaffected. These data indicate that T cells are primed with antigen within the brachial lymph node and subsequently migrate to gastrointestinal tissues.

Figure 5. T cells are primed by epicutaneous antigen in brachial lymph nodes prior to migration to other tissues.

(A) Proliferation of DO11.10 T cells recovered from brachial, inguinal and mesenteric lymph nodes and lamina propria 48h and 72h after application of antigen. (B) Proliferation of DO11.10 T cells in mice treated with FTY720. (C) Summary data showing the impact of FTY720 on proliferation at different sites. Data are mean + SEM of 3 mice/group.

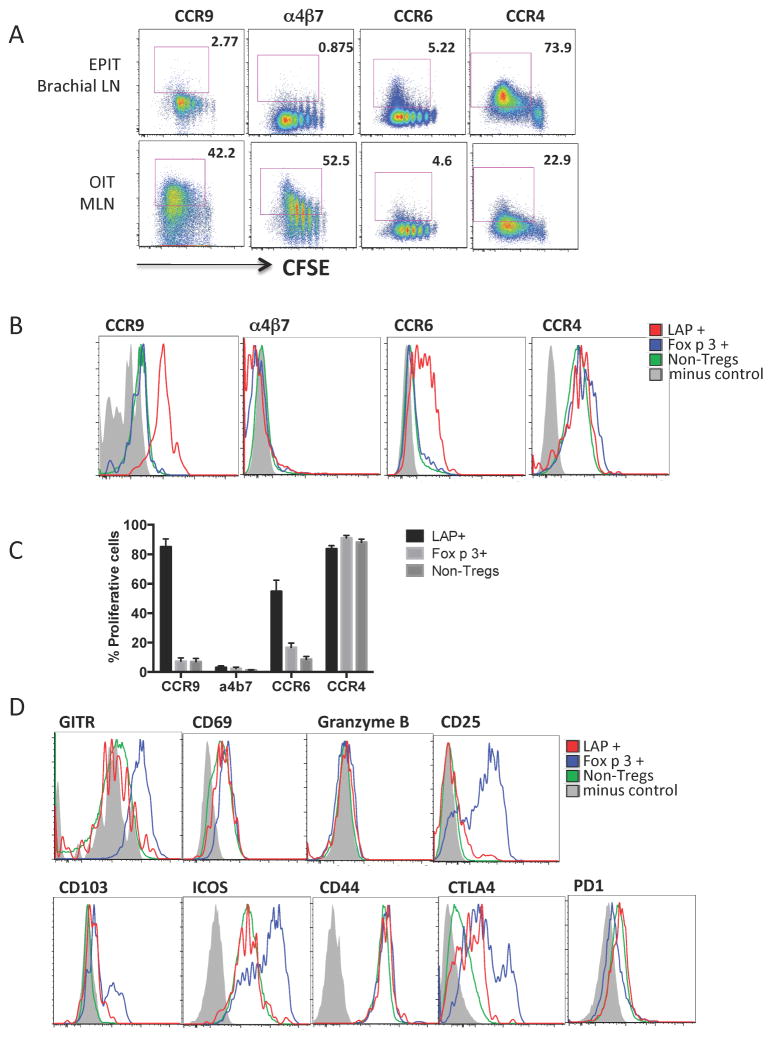

We next studied the expression of tissue-homing markers by T cells primed in skin-draining lymph nodes. After epicutaneous OVA exposure, there was a high expression of the skin-homing marker CCR422 in all CFSE-low cells and also some induction of the pan-mucosal homing marker CCR623, while the gut-homing marker CCR924 was only slightly increased and α4β725 was not expressed (Fig 6, A). By contrast, during oral OVA exposure, proliferating cells in MLN showed high levels of CCR9 and α4β7. Focusing on the expression of tissue-homing markers in different subsets of T cells, we observed that more than 80% of LAP+Foxp3− T cells expressed CCR9 and more than 50% expressed CCR6 in skin-draining lymph nodes after epicutaneous OVA (Figure 6, B and 6, C). This was cell-type specific, as neither Foxp3+ nor non-Tregs expressed CCR6 or CCR9 after epicutaneous antigen exposure. LAP+ cells did not express the gut-homing marker α4β7. All of the different subsets of T cells expressed high levels of CCR4, which is in agreement with priming through the skin. This data shows that there was a unique imprinting of gut homing capacity upon the LAP+ Treg subset.

Figure 6. LAP+ T cells express CCR9 and CCR6 after activation in skin-draining lymph nodes.

(A) Expression of tissue-homing markers in DO11.10 T cells from brachial or mesenteric lymph nodes after epicutaneous or oral antigen, respectively. (B) Representative plots of the expression of tissue-homing markers by T cell subsets activated by epicutaneous antigen. (C) Summary data of chemokine receptor expression in sub-populations. Data are mean + SEM of 5 mice/group in 2 independent experiments. (D) Representative plots showing Treg surface markers. Minus control is staining control.

The surface phenotype of LAP+ cells was more similar to non-Tregs than to the Foxp3+ Treg population. There was no expression of conventional Treg markers such as GITR, CD25 and CD103, and lower levels of ICOS than seen in the Foxp3+ population (Figure 6, D). The LAP+ cells expressed intermediate levels of CTLA-4. The different populations showed similar levels of CD69, CD44 and PD1, and did not express granzyme B.

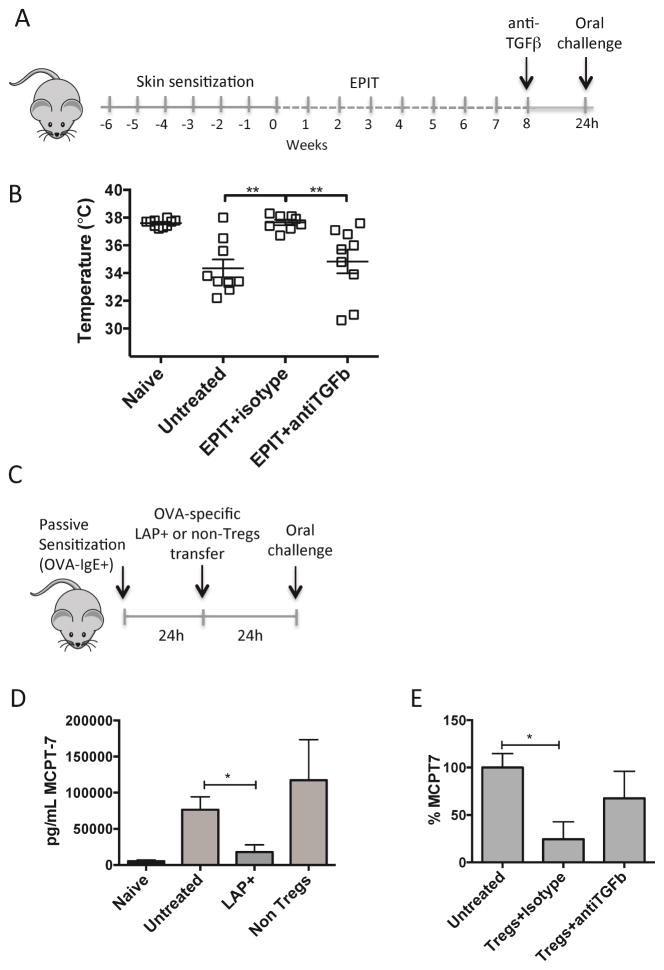

Clinical protection induced by EPIT occurs through a TGFβ-dependent mechanism

We hypothesized that Tregs induced during EPIT could be acting directly on allergic effector cells to suppress hypersensitivity reactions during anaphylaxis without affecting T and B cell responses. Because TGFβ has been related to the suppression capacity of LAP+ T cells, mice treated with EPIT were injected with neutralizing anti-TGFβ antibody or isotype control 24h before challenge (Fig 7, A). Acute suppression of TGFβ completely abrogated the protection induced by EPIT (Fig 7, B). The acute time frame of this neutralization would be too short for modification of B cell responses, and supports the hypothesis that Tregs may directly suppress mast cells. To test this hypothesis, OVA-specific DO11.10 LAP+ Tregs or non-Tregs as control were transferred into Balb/c mice that had been passively sensitized with serum containing high levels of OVA-specific IgE. The next day, mice were orally challenged with OVA and the mast cell protease MCPT-7 was measured in sera obtained 30min after challenge (Fig 7, C). Passively sensitized mice responded to oral OVA challenge with an increase in circulating MCPT-7 (Fig 7, D). Mice receiving OVA-specific LAP+ cells, but not non-Tregs (LAP−,CD257minus;), had decreased MCPT-7 in the serum after oral challenge as well as a trend toward reduced onset of allergic symptoms (7/10 untreated mice versus 2 of 6 mice receiving LAP+ Tregs). Transfer of LAP+ Tregs without antigen specificity (purified from naive Balb/c mice) did not suppress mast cell activation in vivo (data not shown). When mice were injected with anti-TGFβ antibody at the moment of the transfer, the levels of MCPT-7 were partially restored (Fig 7, E), indicating that the suppression of mast cell activation by Tregs is dependent, at least in part, on TGFβ. Although LAP+ Tregs showed the potential to release IL-10 (Fig E3, A), degranulation of bone-marrow derived mast cells stimulated with IL-10 for 24h was in fact enhanced, while TGFβ suppressed degranulation (Fig E3, B). In summary, we show that antigen-specific LAP+ Tregs are induced by epicutaneous immunotherapy, and can directly suppress mast cell activation and downstream type-I hypersensitivity reactions.

Figure 7. Tregs can directly suppress mast cell activation.

(A) Experimental schematic. (B) Temperature measured 30 min after oral OVA challenge. (C) Experimental schematic. (D) MCPT-7 levels in serum obtained 30 min after challenge. (E) Levels of MCPT-7 in serum from mice injected with anti-TGFβ or isotype control calculated as % with respect to untreated mice.. Data are mean ± SEM of at least 6 mice/group in 3 independent experiments. * p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Discussion

Oral tolerance is a state of antigen-specific systemic unresponsiveness that is mediated by Tregs educated in the mesenteric lymph nodes by CD103+ DCs 26. To restore immune tolerance in food-allergic patients, immunotherapy given through the oral route has emerged as a promising treatment 4, 5. Although desensitization, defined as protection from reactions while on therapy, has been achieved in the majority of subjects treated with OIT, a lack of permanent tolerance and recurrence of reactions to foods has been found after OIT is discontinued 4, 6, 8. Our data suggest that an impaired generation of Tregs in the food allergic gastrointestinal tract underlies this resistance to oral tolerance induction, and we identify skin-gut immune communication as a novel means to induce tolerance. Previous studies have documented the efficacy of this approach in suppression of allergic inflammation17–21, and for the first time we demonstrate efficacy in food-induced systemic anaphylaxis.

Allergen-specific immunotherapy has been described as a sequential response, with an early decrease in mast cell and basophil activity associated with a rise in allergen-specific IgG4 antibodies, and a subsequent generation of allergen-specific Tregs that is essential for the development of sustained tolerance. Treg development is believed to be necessary to suppress Th2 responses, and reduce allergen specific IgE and effector cell activation 27. Our data show that the intestine of food allergic mice is not capable of supporting Treg generation in response to fed antigens. This is in agreement with recently reported results 16, and provides an explanation for the lack of sustained efficacy of OIT in the treatment of food allergy in humans 28 and mice 15. Our data show that this Treg defect is limited to the sensitizing allergen, which may be due to the suppressive effect of mast cell activation on Treg generation 16. Mast cell degranulation can induce maturation and migration of DCs to lymph nodes 29 and mast cell activators have been shown to function as adjuvants 30. Our data show that this defect in Treg generation was tissue-specific, and the skin could support Treg generation in sensitized mice. This Treg generation in skin was paralleled by a trend of increased efficacy of epicutaneous immunotherapy compared to oral immunotherapy in preventing anaphylaxis. Therefore site of immunotherapy is a critical factor in clinical efficacy.

Oral tolerance is mediated by antigen-specific Foxp3+ Tregs induced in the periphery 9. Th3 regulatory cells, characterized by the expression of LAP on their surface, were also originally described as key players in the development of oral tolerance. Feeding of self-antigens including myelin basic protein induces an expansion of Th3 cells in mice and humans 11, 31. These previously described Th3 cells are consistent with the phenotype of gastrointestinal T cells induced by epicutaneous antigen exposure in our study. Th3 cells induced by feeding can suppress experimental models of colitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, multiple sclerosis and diabetes 32–36. Although not specifically termed Th3 cells, LAP+Foxp3− cells induced by inhaled antigen can suppress allergic eosinophilia in the lung 37. In humans, Th3 cells have been found in blood 38 and in tumors, with higher immunosuppressive activity than Foxp3+ Tregs 39, 40. In addition, children with food allergy have reduced numbers of Th3 cells in the duodenal mucosa 41, 42. The suppressive effects of Th3 cells are mediated by secreted TGFβ and IL10 34, 38, 40 and also by contact through membrane-bound TGFβ1 43. The LAP+Foxp3− cells have been described as CD69+CTLA-4+, with variable reported CD25 expression between studies, possibly indicating differences in the level of activation 34, 37, 38, 40, 43–45. In our study, we observed that LAP+Foxp3− cells induced by epicutaneous antigen were CD69+CD25−CTLA-4low. However, they did not express markers associated with Foxp3+ Tregs, such as GITR or CD103. We confirmed the regulatory role of these LAP+ Tregs in standard suppression assays, and more relevant to food allergy, showed that they could directly suppress mast cell activation triggered by oral food challenge. Our results emphasize a key role of this overlooked population of Tregs in the protection against food allergy and anaphylaxis.

The selective induction of gastrointestinal homing of LAP+ Tregs by epicutaneous antigen was a novel and unexpected finding. The gastrointestinal tract and skin provide tissue-specific T cell imprinting, such that T cells home back to the initial site of priming 46, 47,48, 49. When we examined antigen-specific proliferating T cells as a whole, these paradigms were true. However, when LAP+ T cells were examined in skin-draining lymph nodes, CCR9 and CCR6 were highly expressed on LAP+ T cells together with CCR4, conferring a phenotype capable of homing to multiple tissues including the gastrointestinal tract. This was unique to this population and not observed on Foxp3+ Tregs or non-Tregs. Intranasal vaccination has also been described to elicit migration of antigen-specific T cells to the MLN that can protect against intestinal pathogens 50, 51, indicating that tissue-specific imprinting is a flexible and cell-type specific process. Understanding how to manipulate this homing potential has major implications for vaccine and immunotherapy design.

The mechanism by which immunotherapy leads to clinical protection has primarily been thought to be due to changes in the antibody repertoire, with sustained protection requiring a loss of allergen-specific IgE. However, in human immunotherapy trials allergen-specific IgE and basophil activation have not been able to discriminate between those with transient desensitization versus sustained tolerance 4, 8. Regulatory T cells are thought to participate in this process by suppressing Th2 responses necessary for the maintenance of IgE. The suppression of Th2 responses would also be expected to reduce local tissue inflammation. EPIT has previously been described to suppress airway hyperreactivity and allergic esophago-gastro-enteropathy 17–19 through the generation of CD25+ Tregs 21. We show that TGFβ is critical for protection against anaphylaxis, but through a novel mechanism involving a direct suppression of mast cell activation by Tregs rather than through modulation of antibody levels. It has been reported that CD25+ Tregs can inhibit mast cell degranulation directly through a contact-dependent manner 52 and that transfer of Tregs can suppress anaphylaxis 53. In vitro studies identify the suppressive mechanisms as OX40-OX40L interactions 54 and soluble and surface-bound TGFβ 53, 55, 56. In addition, CD25+ Tregs reduce FcεRI surface expression on mast cells, reducing antigen sensitivity 52. Our in vitro studies support a role for TGFβ, but not IL-10, in suppression of mast cells. However, neutralization experiments in vivo suggest additional mechanisms beyond TGFβ contribute to mast cell suppression. Although our data focus on LAP+ Tregs due to our finding that they are the main Treg cells induced early in EPIT, our data do not rule out a role for Foxp3+CD25+ Tregs in clinical protection. Neutralization of TGFβ would also be expected to suppress the activity of Foxp3+ induced Tregs. Th3 cells promote the development of Foxp3+ Tregs 57 and therefore there may be a contribution by both Treg subsets after prolonged immunotherapy.

Our data show for the first time that epicutaneous immunotherapy generates gut-homing antigen-specific LAP+ Tregs that can directly suppress systemic anaphylaxis without upstream modification of humoral or cellular immunity. This changes the paradigm by which Tregs are thought to contribute to tolerance to allergens. Optimization of antigen delivery and Treg generation by the epicutaneous route may be the most effective means for the generation a safe and effective treatment for food allergy leading to sustained immune tolerance.

Supplementary Material

Key Messages.

Epicutaneous immunotherapy protects against food-induced anaphylaxis independent of the initial route of sensitization

Treg generation by the oral route is impaired in allergic mice, while epicutaneous antigen delivery induces gut-homing LAP+ Foxp3-Tregs

EPIT prevents food-induced anaphylaxis by a TGFβ-dependent mechanism

Tregs directly suppress mast cell activation in response to a food challenge

Acknowledgments

We thank the Flow Cytometry Core at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai for assistance with cell sorting, Dr. Wing-hong Kwan for useful experimental advice and Dr. Sara Benede for providing bone-marrow derived mast cells.

Supported by AI093577 from the NIH (to MCB), David H. and Julia Koch Research Program in Food Allergy Therapeutics (to HAS) and Robin Chemers Neustein Fellowship (to LT).

Abbreviations

- EPIT

Epicutaneous immunotherapy

- LAP

Latency-associated peptide

- MLN

Mesenteric lymph node

- OIT

Oral immunotherapy

Footnotes

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest: LT received travel support from DBV Technologies (the developer and owner of the Viaskin® patch) to present this work in part at the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. LM is an employee of DBV Technologies, HAS is the Chief Scientific Officer of DVB Technologies and PHB is CEO of DBV Technologies. MCB has no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sicherer SH. Epidemiology of food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:594–602. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fleischer DM, Perry TT, Atkins D, Wood RA, Burks AW, Jones SM, et al. Allergic reactions to foods in preschool-aged children in a prospective observational food allergy study. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e25–32. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson HS, Lahr J, Rule R, Bock A, Leung D. Treatment of anaphylactic sensitivity to peanuts by immunotherapy with injections of aqueous peanut extract. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;99:744–51. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(97)80006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burks AW, Jones SM, Wood RA, Fleischer DM, Sicherer SH, Lindblad RW, et al. Oral immunotherapy for treatment of egg allergy in children. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:233–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Varshney P, Jones SM, Scurlock AM, Perry TT, Kemper A, Steele P, et al. A randomized controlled study of peanut oral immunotherapy: clinical desensitization and modulation of the allergic response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:654–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.12.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keet CA, Seopaul S, Knorr S, Narisety S, Skripak J, Wood RA. Long-term follow-up of oral immunotherapy for cow’s milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:737–9. e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Syed A, Garcia MA, Lyu SC, Bucayu R, Kohli A, Ishida S, et al. Peanut oral immunotherapy results in increased antigen-induced regulatory T-cell function and hypomethylation of forkhead box protein 3 (FOXP3) J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:500–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.12.1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vickery BP, Scurlock AM, Kulis M, Steele PH, Kamilaris J, Berglund JP, et al. Sustained unresponsiveness to peanut in subjects who have completed peanut oral immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:468–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hadis U, Wahl B, Schulz O, Hardtke-Wolenski M, Schippers A, Wagner N, et al. Intestinal tolerance requires gut homing and expansion of FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in the lamina propria. Immunity. 2011;34:237–46. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mucida D, Kutchukhidze N, Erazo A, Russo M, Lafaille JJ, Curotto de Lafaille MA. Oral tolerance in the absence of naturally occurring Tregs. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1923–33. doi: 10.1172/JCI24487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fukaura H, Kent SC, Pietrusewicz MJ, Khoury SJ, Weiner HL, Hafler DA. Induction of circulating myelin basic protein and proteolipid protein-specific transforming growth factor-beta1-secreting Th3 T cells by oral administration of myelin in multiple sclerosis patients. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:70–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI118779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trentham DE, Dynesius-Trentham RA, Orav EJ, Combitchi D, Lorenzo C, Sewell KL, et al. Effects of oral administration of type II collagen on rheumatoid arthritis. Science. 1993;261:1727–30. doi: 10.1126/science.8378772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chaillous L, Lefevre H, Thivolet C, Boitard C, Lahlou N, Atlan-Gepner C, et al. Oral insulin administration and residual beta-cell function in recent-onset type 1 diabetes: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Diabete Insuline Orale group. Lancet. 2000;356:545–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02579-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neurath MF, Fuss I, Kelsall BL, Presky DH, Waegell W, Strober W. Experimental granulomatous colitis in mice is abrogated by induction of TGF-beta-mediated oral tolerance. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2605–16. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.6.2605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leonard SA, Martos G, Wang W, Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Berin MC. Oral immunotherapy induces local protective mechanisms in the gastrointestinal mucosa. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:1579–87. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burton OT, Noval Rivas M, Zhou JS, Logsdon SL, Darling AR, Koleoglou KJ, et al. Immunoglobulin E signal inhibition during allergen ingestion leads to reversal of established food allergy and induction of regulatory T cells. Immunity. 2014;41:141–51. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mondoulet L, Dioszeghy V, Ligouis M, Dhelft V, Dupont C, Benhamou PH. Epicutaneous immunotherapy on intact skin using a new delivery system in a murine model of allergy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2010;40:659–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2009.03430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mondoulet L, Dioszeghy V, Vanoirbeek JA, Nemery B, Dupont C, Benhamou PH. Epicutaneous immunotherapy using a new epicutaneous delivery system in mice sensitized to peanuts. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2011;154:299–309. doi: 10.1159/000321822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mondoulet L, Dioszeghy V, Larcher T, Ligouis M, Dhelft V, Puteaux E, et al. Epicutaneous immunotherapy (EPIT) blocks the allergic esophago-gastro-enteropathy induced by sustained oral exposure to peanuts in sensitized mice. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31967. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dioszeghy V, Mondoulet L, Dhelft V, Ligouis M, Puteaux E, Benhamou PH, et al. Epicutaneous immunotherapy results in rapid allergen uptake by dendritic cells through intact skin and downregulates the allergen-specific response in sensitized mice. J Immunol. 2011;186:5629–37. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dioszeghy V, Mondoulet L, Dhelft V, Ligouis M, Puteaux E, Dupont C, et al. The regulatory T cells induction by epicutaneous immunotherapy is sustained and mediates long-term protection from eosinophilic disorders in peanut-sensitized mice. Clin Exp Allergy. 2014;44:867–81. doi: 10.1111/cea.12312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soler D, Humphreys TL, Spinola SM, Campbell JJ. CCR4 versus CCR10 in human cutaneous TH lymphocyte trafficking. Blood. 2003;101:1677–82. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ito T, Carson WFt, Cavassani KA, Connett JM, Kunkel SL. CCR6 as a mediator of immunity in the lung and gut. Exp Cell Res. 2011;317:613–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zabel BA, Agace WW, Campbell JJ, Heath HM, Parent D, Roberts AI, et al. Human G protein-coupled receptor GPR-9-6/CC chemokine receptor 9 is selectively expressed on intestinal homing T lymphocytes, mucosal lymphocytes, and thymocytes and is required for thymus-expressed chemokine-mediated chemotaxis. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1241–56. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.9.1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berlin C, Berg EL, Briskin MJ, Andrew DP, Kilshaw PJ, Holzmann B, et al. Alpha 4 beta 7 integrin mediates lymphocyte binding to the mucosal vascular addressin MAdCAM-1. Cell. 1993;74:185–95. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90305-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pabst O, Mowat AM. Oral tolerance to food protein. Mucosal Immunol. 2012;5:232–9. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akdis CA, Akdis M. Mechanisms of allergen-specific immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.11.030. quiz 8–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berin MC, Mayer L. Can we produce true tolerance in patients with food allergy? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:14–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.10.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jawdat DM, Albert EJ, Rowden G, Haidl ID, Marshall JS. IgE-mediated mast cell activation induces Langerhans cell migration in vivo. J Immunol. 2004;173:5275–82. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.8.5275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McLachlan JB, Shelburne CP, Hart JP, Pizzo SV, Goyal R, Brooking-Dixon R, et al. Mast cell activators: a new class of highly effective vaccine adjuvants. Nat Med. 2008;14:536–41. doi: 10.1038/nm1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen Y, Kuchroo VK, Inobe J, Hafler DA, Weiner HL. Regulatory T cell clones induced by oral tolerance: suppression of autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Science. 1994;265:1237–40. doi: 10.1126/science.7520605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen ML, Yan BS, Bando Y, Kuchroo VK, Weiner HL. Latency-associated peptide identifies a novel CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cell subset with TGFbeta-mediated function and enhanced suppression of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2008;180:7327–37. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ishikawa H, Ochi H, Chen ML, Frenkel D, Maron R, Weiner HL. Inhibition of autoimmune diabetes by oral administration of anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody. Diabetes. 2007;56:2103–9. doi: 10.2337/db06-1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ochi H, Abraham M, Ishikawa H, Frenkel D, Yang K, Basso AS, et al. Oral CD3-specific antibody suppresses autoimmune encephalomyelitis by inducing CD4+ CD25− LAP+ T cells. Nat Med. 2006;12:627–35. doi: 10.1038/nm1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oida T, Zhang X, Goto M, Hachimura S, Totsuka M, Kaminogawa S, et al. CD4+CD25− T cells that express latency-associated peptide on the surface suppress CD4+CD45RBhigh-induced colitis by a TGF-beta-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 2003;170:2516–22. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.5.2516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu HY, Quintana FJ, Weiner HL. Nasal anti-CD3 antibody ameliorates lupus by inducing an IL-10-secreting CD4+ CD25− LAP+ regulatory T cell and is associated with down-regulation of IL-17+ CD4+ ICOS+ CXCR5+ follicular helper T cells. J Immunol. 2008;181:6038–50. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.6038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duan W, So T, Mehta AK, Choi H, Croft M. Inducible CD4+LAP+Foxp3- regulatory T cells suppress allergic inflammation. J Immunol. 2011;187:6499–507. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gandhi R, Farez MF, Wang Y, Kozoriz D, Quintana FJ, Weiner HL. Cutting edge: human latency-associated peptide+ T cells: a novel regulatory T cell subset. J Immunol. 2010;184:4620–4. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mahalingam J, Lin YC, Chiang JM, Su PJ, Fang JH, Chu YY, et al. LAP+CD4+ T cells are suppressors accumulated in the tumor sites and associated with the progression of colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:5224–33. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scurr M, Ladell K, Besneux M, Christian A, Hockey T, Smart K, et al. Highly prevalent colorectal cancer-infiltrating LAP(+) Foxp3(−) T cells exhibit more potent immunosuppressive activity than Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells. Mucosal Immunol. 2014;7:428–39. doi: 10.1038/mi.2013.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perez-Machado MA, Ashwood P, Thomson MA, Latcham F, Sim R, Walker-Smith JA, et al. Reduced transforming growth factor-beta1-producing T cells in the duodenal mucosa of children with food allergy. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:2307–15. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beyer K, Castro R, Birnbaum A, Benkov K, Pittman N, Sampson HA. Human milk-specific mucosal lymphocytes of the gastrointestinal tract display a TH2 cytokine profile. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109:707–13. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.122503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Han Y, Guo Q, Zhang M, Chen Z, Cao X. CD69+ CD4+ CD25− T cells, a new subset of regulatory T cells, suppress T cell proliferation through membrane-bound TGF-beta 1. J Immunol. 2009;182:111–20. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boswell S, Pathan AA, Pereira SP, Williams R, Behboudi S. Induction of CD152 (CTLA-4) and LAP (TGF-beta1) in human Foxp3- CD4+ CD25− T cells modulates TLR-4 induced TNF-alpha production. Immunobiology. 2013;218:427–34. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2012.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zheng SG, Gray JD, Ohtsuka K, Yamagiwa S, Horwitz DA. Generation ex vivo of TGF-beta-producing regulatory T cells from CD4+CD25− precursors. J Immunol. 2002;169:4183–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mora JR, Bono MR, Manjunath N, Weninger W, Cavanagh LL, Rosemblatt M, et al. Selective imprinting of gut-homing T cells by Peyer’s patch dendritic cells. Nature. 2003;424:88–93. doi: 10.1038/nature01726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stagg AJ, Kamm MA, Knight SC. Intestinal dendritic cells increase T cell expression of alpha4beta7 integrin. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:1445–54. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200205)32:5<1445::AID-IMMU1445>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Campbell DJ, Butcher EC. Rapid acquisition of tissue-specific homing phenotypes by CD4(+) T cells activated in cutaneous or mucosal lymphoid tissues. J Exp Med. 2002;195:135–41. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dudda JC, Simon JC, Martin S. Dendritic cell immunization route determines CD8+ T cell trafficking to inflamed skin: role for tissue microenvironment and dendritic cells in establishment of T cell-homing subsets. J Immunol. 2004;172:857–63. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.2.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ciabattini A, Pettini E, Fiorino F, Prota G, Pozzi G, Medaglini D. Distribution of primed T cells and antigen-loaded antigen presenting cells following intranasal immunization in mice. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19346. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ruane D, Brane L, Reis BS, Cheong C, Poles J, Do Y, et al. Lung dendritic cells induce migration of protective T cells to the gastrointestinal tract. J Exp Med. 2013;210:1871–88. doi: 10.1084/jem.20122762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kashyap M, Thornton AM, Norton SK, Barnstein B, Macey M, Brenzovich J, et al. Cutting edge: CD4 T cell-mast cell interactions alter IgE receptor expression and signaling. J Immunol. 2008;180:2039–43. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ganeshan K, Bryce PJ. Regulatory T cells enhance mast cell production of IL-6 via surface-bound TGF-beta. J Immunol. 2012;188:594–603. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gri G, Piconese S, Frossi B, Manfroi V, Merluzzi S, Tripodo C, et al. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells suppress mast cell degranulation and allergic responses through OX40-OX40L interaction. Immunity. 2008;29:771–81. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gomez G, Ramirez CD, Rivera J, Patel M, Norozian F, Wright HV, et al. TGF-beta 1 inhibits mast cell Fc epsilon RI expression. J Immunol. 2005;174:5987–93. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.5987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhao W, Gomez G, Yu SH, Ryan JJ, Schwartz LB. TGF-beta1 attenuates mediator release and de novo Kit expression by human skin mast cells through a Smad-dependent pathway. J Immunol. 2008;181:7263–72. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.10.7263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Carrier Y, Yuan J, Kuchroo VK, Weiner HL. Th3 cells in peripheral tolerance. I. Induction of Foxp3-positive regulatory T cells by Th3 cells derived from TGF-beta T cell-transgenic mice. J Immunol. 2007;178:179–85. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.