Abstract

The colony stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) functions as the major receptor for macrophage colony stimulating factor (CSF1) with crucial roles in regulating myelopoeisis. CSF1R can be proteolytically released from the cell surface by A disintegrin and metalloprotease 17 (ADAM17). Here we identified CSF1R as a major substrate of ADAM17 in an unbiased degradomics screen. We explored the impact of CSF1R shedding by ADAM17 and its upstream regulator, inactive rhomboid protein 2 (iRhom2, gene name Rhbdf2), on homeostatic development of mouse myeloid cells. In iRhom2−/− mice, we found constitutive accumulation of membrane-bound CSF1R on myeloid cells at steady state, although cell numbers of these populations were not altered. However, in the context of mixed bone marrow (BM) chimera, under competitive pressure, iRhom2−/− BM progenitor-derived monocytes, tissue macrophages and lung DCs showed a repopulation advantage over those derived from wild type (WT) BM progenitors, suggesting enhanced CSF1R signaling in the absence of iRhom2. In vitro experiments indicate that iRhom2−/− Lin−SCA-1+c-Kit+ (LSKs) cells, but not granulocyte-macrophage progenitors (GMPs), had faster growth rates than WT cells in response to CSF1. Our results shed light on an important role of iRhom2/ADAM17 pathway in regulation of CSF1R shedding and repopulation of monocytes, macrophages and DCs.

Keywords: iRhom2, ADAM17, metalloprotease, CSF1R, myelopoiesis

INTRODUCTION

A disintegrin and metalloprotease 17 (ADAM17, also referred to TNFα convertase, TACE), is a membrane-anchored metalloprotease that cleaves membrane-bound proteins, including tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), CD62L, and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) ligands, into their soluble forms [1]. Inactive rhomboid protein 2 (iRhom2, gene name Rhbdf2) is a newly identified regulator of ADAM17 that controls the maturation and function of ADAM17 [2-4]. Mice lacking iRhom2 resemble mice conditionally lacking ADAM17 in myeloid cells in that they have no evident developmental abnormalities, but are protected from the activities of soluble TNFα in mouse models of endotoxin shock lethality and inflammatory arthritis [5;6]. Interestingly, in iRhom2−/− mice, loss of ADAM17-dependent shedding activity is limited to the immune sytem, such as BM and lymph nodes, because the related iRhom1 can support the essential functions of ADAM17 in most other non-immune cells and tissues [5;7;8].

ADAM17 substrates on the cell surface [9] include the receptor for colony stimulating factor 1, CSF1R (also referred to as CD115 or MCSFR) [10], which has restricted expression in the mononuclear phagocyte system [11]. The CSF1R is activated by macrophage colony stimulating factor (CSF1) and IL-34 [12], and is essential for differentiation, proliferation and survival of monocytes, macrophages and their progenitors [11]. Recently, it was reported that CSF1 also directly induces differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) towards granulocyte-monocyte progenitors (GMPs) by upregulating PU.1, the master transcription factor for myeloid cell differentiation [13]. Mice deficient in CSF1 or CSF1R lack tissue resident macrophages, indicating that the CSF1/CSF1R system has an essential role in the development of these cell types [14;15].

In the current study, we performed a proteomic-based degradomics screen for substrates of ADAM17 in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (mEFs), and CSF1R emerged as a major substrate. Our main subsequent goal was, therefore, to determine the impact of iRhom2/ADAM17 pathway on CSF1R shedding and the development and homeostasis of mouse myeloid cell populations. For this purpose, we focused on iRhom2−/− mice, as these animals lack functional ADAM17 in immune cells. Our data indicate that the iRhom2/ADAM17 pathway plays an important role in regulating CSF1R expression in the myeloid cell compartment at steady state, and in modulating development of monocytes/macrophages during their repopulation.

RESULTS

Proteomic identification of CSF1R as a high confidence substrate of ADAM17

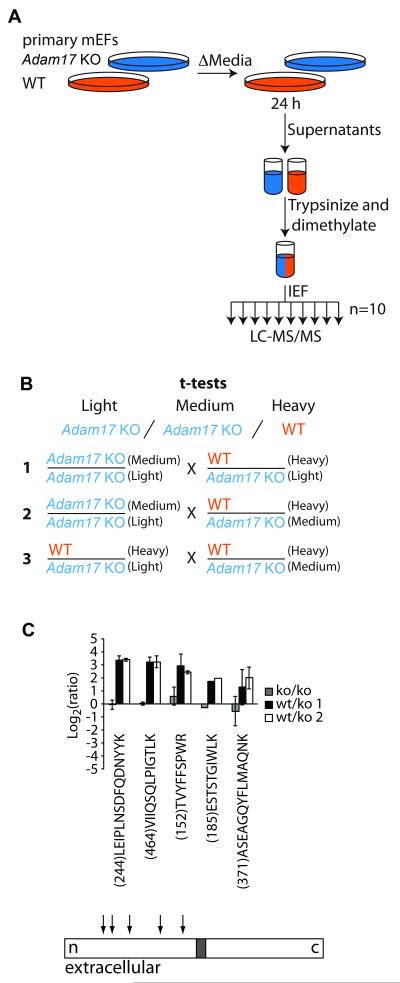

In order to identify substrates for ADAM17 with an unbiased approach, we compared primary mEFs lacking Adam17 to wild type cells. Cell culture supernatants were collected following 24 h serum starvation. Samples were reduced, alkylated and trypsinized and primary amines were dimethylated for quantitation. Supernatants from fibroblasts lacking Adam17 were labeled with both light and medium formaldehyde, while those from wild type cells were labeled with heavy formaldehyde. Samples were fractionated offline by in-solution isoelectric focusing and subsequently analyzed by LC-MS/MS (Figure 1A-B). Among 346 transmembrane proteins identified from the assay, CSF1R showed the highest fold change between Adam17 wild type (WT) and knockout (KO) samples. Peptides identified from CSF1R are all in the extracellular domain, corroborating the proteolytic release from the membrane (Figure 1C). Our screen identified a total of four membrane-anchored proteins with a ratio of >2 between the Adam17 WT and KO mEFs in both the heavy/medium (H/M) and heavy/light (H/L) samples, which we chose as our threshold. The H/M ratio for CSF1R was 11.011 (18.5% variability) and the H/L ratio was 9.927 (43% variability). The other 3 membrane proteins were Monocyte Differentiation antigen CD14 (H/M ratio 2.604, variability 16.3%, H/L ratio 2.459, variability 38.3%), the isoform 2 of the vascular adhesion protein 1 (VCAM1, H/M ratio 2.530, variability 36.9%, H/L ratio 2.361, 43.2% variability). Finally the C-type Mannose receptor 2 (MRC2, H/M ratio 1.539, variability 17.3%, H/L ratio 1.946, variability 18.3%) was close to our 2.0-fold cutoff and would therefore require orthogonal validation to validate it is shed by ADAM17. The functional relevance of the processing of the three other candidates of ADAM17 substrates (CD14, VCAM1, and MRC2) will be explored separately in the future.

Figure 1. Proteomics study identified CSF1R as a high confidence substrate of ADAM17.

(A) Flow diagram outlining the proteomics method. Culture supernatants from Adam17 WT (+/+) and KO (−/−) primary mEFs were collected, proteins in culture supernatants were concentrated, reduced and alkylated. Tryptic peptides were dimethylated for quantitation and fractionated by IEF prior to LC-MS/MS (see materials and methods for details). (B) Overview of quantitation and statistical analysis. Within each replicate (n=5), peptides from Adam17 KO supernatants were labeled light and medium, and peptides from WT supernatants were labeled heavy by dimethylation. Peptides corresponding to equal protein amounts were mixed from each label. T-tests were performed between the indicated ratios (1, 2 and 3) to identify peptides with statistically different abundance between the two cell populations at FDR<0.02. (C) Peptides identified from CSF1R are illustrated. Error bars represent one standard deviation from the mean. Peptide sequence is given below each bar. A schematic of a type I transmembrane protein like CSF1R is shown below. Peptide positions are indicated by arrows. N- (n) and C- (c) termini, transmembrane (grey boxes) and extracellular regions are shown.

iRhom2 deficiency leads to accumulation of cell surface CSF1R in myeloid compartment

Since the major function of the CSF1R is to control the differentiation of myeloid cells into monocytes and macrophages, we determined how absence of ADAM17 function in the immune system affects the development of monocytes and macrophages in vivo. For this purpose, we chose to study iRhom2−/− mice, as these animals lack ADAM17 in immune cells and therefore represent an efficient approach to examine the function of ADAM17 in these cell types. Flow-cytometry analysis of immune cell populations in iRhom2−/− mice showed increased levels of CSF1R on the cell surface compared to WT mice at steady state in all CSF1-responsive immune cell types, including blood and BM monocytes, conventional dendritic cells (cDCs), plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs), residential tissue macrophages, myeloid progenitor and precursors (LSKs, common myeloid progenitor CMPs, GMPs, common dendritic progenitors CDPs and monocyte/macrophage precursors MDPs) (Figure 2, supplemental Figure S1). Moreover, myeloid cells, such as neutrophils and their precursor GMPs, that normally only express CSF1R transcript [14;16] (www.biogps.org) also had elevated cell surface expression of CSF1R protein in iRhom2−/− mice. As expected, lymphocytes, including T, B and natural killer (NK) cells do not express CSF1R in the iRhom2−/− or WT mice (Figure 2). Similar results were obtained in ADAM17fl/flLysMCre mice, which lack ADAM17 only in the myeloid cell compartment (supplemental Figure S2), corroborating the results in iRhom2−/− mice. This pattern of CSF1R expression and accumulation on the cell surface in the absence of iRhom2/ADAM17 corresponds to the expression pattern of CSF1R transcript in the immune system [16] (www.biogps.org).

Figure 2. CSF1R accumulates on the cell surface of myeloid cell populations in the absence of iRhom2.

Expression of CSF1R (CD115) was analyzed by FACS in various immune cell populations including blood and BM monocytes and neutrophils, splenic neutrophils, NK, CD4+ and CD8+ T, B, cells cDCs and pDCs, tissue resident macrophages from spleen, peritoneum, brain, liver, lung and kidney, and BM progenitors (LSKs, CMPs, GMPs, CDPs, and MDPs). in iRhom2 WT (+/+) and KO (−/−) mice. Gating strategy is provided in supplemental Figure S1). Histogram (A) and mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CD115 (B) are illustrated. Means ± s.e.m, n=4 mice / group. * P<0.05, ** P<0.005, *** P<0.0005, **** P<0.0001. unpaired two-tailed Student t test. Data shown are representative of 6-10 independent experiments with similar results.

Numbers of myeloid cell populations are unaffected in naïve iRhom2−/− mice

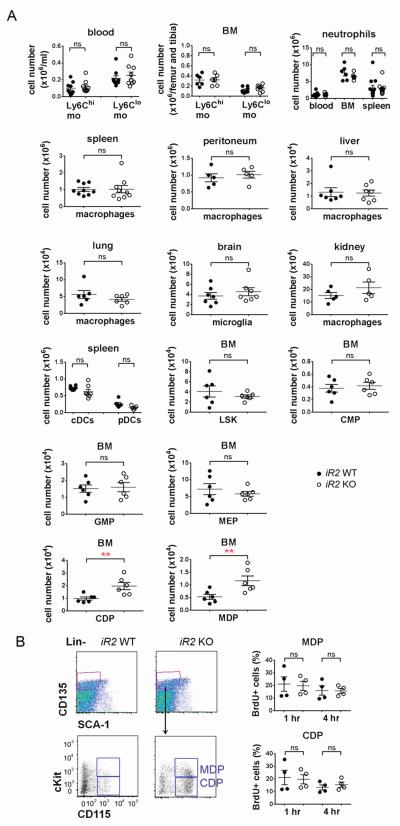

Signaling through CSF1R drives differentiation, proliferation and survival of monocytes, macrophages, and their precursor and progenitor cells. Given the increased cell surface accumulation of CSF1R in the myeloid cell compartment of iRhom2−/− mice, we determined whether these high-CSF1R-expressing cells are expanded in iRhom2−/− mice at steady state. Flow-cytometry analysis showed that there was no detectable difference between iRhom2−/− and WT mice in the percentage or numbers of the following cell populations: blood and BM monocytes, neutrophils, spleen cDCs and pDCs, lung DCs, tissue resident macrophages, and BM progenitor cells (LSKs, CMPs, GMPs, and megakaryocyte/erythrocyte progenitor MEPs) (Figure 3A). There was a ~2-3 fold increase in CDPs and MDPs in iRhom2−/− BM compared to WT mice. However, BrdU incorporation assays failed to detect any increase in cell proliferation of CDPs or MDPs from iRhom2−/− mice (Figure 3B). Given that none the mature myeloid cell populations were altered by iRhom2 deficiency, this increase in CDPs and MDPs might be due to a shift of the gating marker, CSF1R, which was used to identify these cells and is up-regulated in the iRhom2−/− cells, rather than a true increase in their cell numbers. CSF1 can also be cleaved by ADAM17 [17], raising the possibility that the apparently normal numbers of myeloid cell populations in iRhom2−/− mice was due to decreased levels of circulating CSF1 that could counterbalance the effects by elevated cell surface CSF1R in these mice. This is not likely the case, because we did not detect a difference in the serum levels of CSF1 between iRhom2−/− and WT mice (supplemental Figure S3). Taken together, these data indicate that accumulation of CSF1R on the cell surface has minimal impact on myeloid cell homeostasis in iRhom2−/− mice at steady state.

Figure 3. iRhom2 deficiency does not alter myeloid cell numbers at steady state.

(A) Blood and BM monocytes, neutrophils, tissue macrophages, DCs and BM myeloid progenitor cells are enumerated by FACS. Data shown are means ± s.e.m, n=6-8 mice/group. ** P<0.005, ns, not significant. Student t test. (B) Proliferation of MDPs (Lin−SCA-1−CD135+CD115+c-Kithi), and CDPs (Lin−SCA-1−CD135+CD115+c-Kitlo) was measured in the BM of mice intraperitoneally injected with 1 mg of BrdU after 1 and 4 hs. Percentages of BrdU-positive cells were illustrated. Means ± s.e.m, n=4 mice / group. ns, not significant. unpaired two-tailed Student t test.

Repopulation advantage of iRhom2-deficient myeloid cells

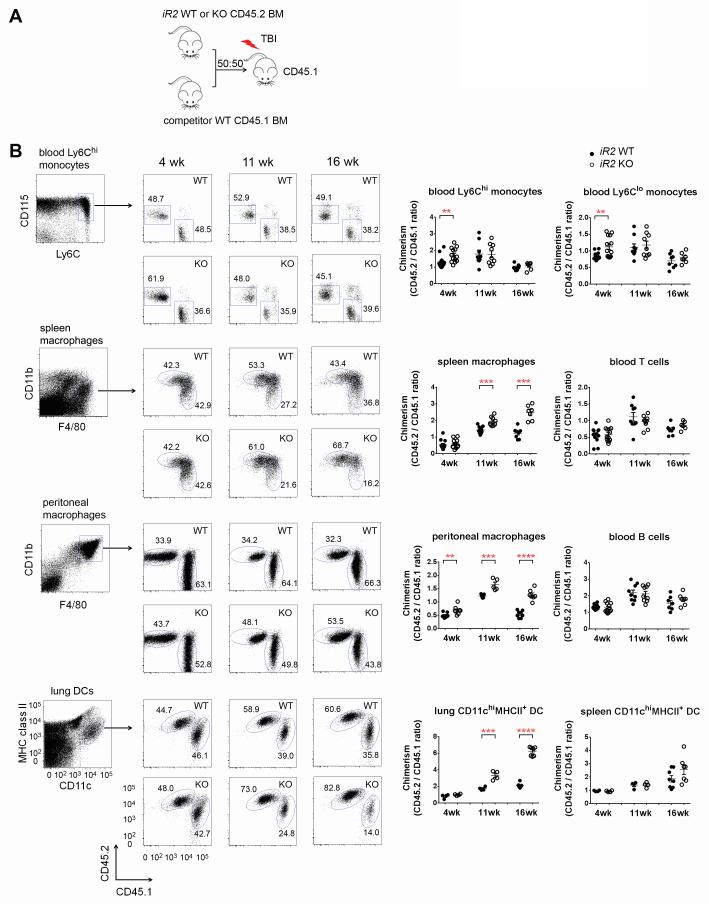

During homeostasis, basal turn-over of monocytes/macrophages is maintained by low levels of CSF1 generated by somatic tissues [11;18;19]. In conditions such as BM transplantation, however, irradiation triggers secretion of CSF1 [20], which drives proliferation and differentiation of transplanted myeloid progenitor cells to become mature monocytes/macrophages/DCs. To determine whether iRhom2−/− myeloid cells have a repopulation advantage when competing with WT cells, we performed mixed BM chimera experiments. iRhom2−/− or WT CD45.2 BM donor cells were mixed with WT CD45.1 competitor cells at 1:1 ratio, and injected into lethally irradiated WT CD45.1 mice, as illustrated in Figure 4A. As early as 4 wks after reconstitution, the donor-to-competitor ratio (CD45.2/CD45.1) in blood monocytes was increased in mice receiving iRhom2−/− donor cells compared to those receiving WT donor cells. After 11 weeks, WT donor-derived monocytes reached a similar donor-to-competitor ratio as iRhom2−/− donor-derived blood monocytes, indicating that the repopulation advantage of iRhom2−/− donor-derived monocytes was transient (Figure 4B and supplemental Figure S4A, B). To rule out the possibility that the increased donor-to-competitor ratio of blood monocytes in mice receiving iRhom2−/− donor cells is due to shift of gating marker CSF1R (CD115) in the absence of iRhom2, blood monocytes were also gated using F4/80 instead of CSF1R (CD115) in the gating strategy, and similar results were obtained (supplemental Figure S4C). In contrast, iRhom2−/− donor-derived spleen and peritoneal macrophages, as well as lung DCs, showed a gradual and persistent increase over WT donor-derived cells beginning between 4-11 weeks and continuing to 16 wks (Figure 4B and supplemental Figure S4). No significant difference between iRhom2−/− and WT spleen cDCs (Figure 4B), neutrophil, or myeloid progenitor cells (HSCs, GMPs, MDPs or CDPs) (data not shown) was observed. Furthermore, the repopulation advantage was restricted to the myeloid CSF1R-dependent lineage, as donor-to-competitor ratios in lymphoid T and B cells were similar in mice receiving WT and iRhom2−/− donor cells (Figure 4B). In the mixed BM chimera, elevated cell surface CSF1R levels were present only in myeloid cells derived from iRhom2−/− donor cells (supplemental Figure S5) demonstrating that this is a cell intrinsic effect.

Figure 4. Repopulation advantage of myeloid cells derived from iRhom2−/− BM progenitor cells in vivo.

(A) BM cells from WT CD45.1 mice (competitor) and iRhom2 WT (+/+) CD45.2 or iRhom2 KO (−/−) CD45.2 mice (donor) were mixed at 1:1 ratio and injected to lethally irradiated (TBI: total body irradiation) WT CD45.1 mice. (B) Repopulation of immune cells at 4, 11 and 16 wks was assessed by FACS. Dot plots of representative cell populations were shown (left column). Blood Ly6Chi and Ly6Clo monocytes were identified as SSCloCD11b+CD115+Ly6Chi and SSCloCD11b+CD115+Ly6Clo cells respectively; spleen macrophages as F4/80hiCD11blo cells; peritoneal macrophages as F4/80hiCD11bhicells; lung DCs as CD11chiMHCclass II+ cells. Gating strategy of other cell types is provided in the supplemental Figure S1. Donor-to-competitor ratios (CD45.2/CD45.1 chimerism) were calculated and illustrated (right two columns) in each cell population. Data shown are means ± s.e.m. n=6-10 mice / group. Data represent 3 independent experiments with similar results. * P<0.05, ** P<0.005, *** P<0.0005, **** P<0.0001. unpaired two-tailed Student t test.

To further evaluate the impact of iRhom2 deficiency on the response of BM progenitor cells to CSF1, we performed an in vitro competition assay. When cultured in the presence of CSF1, iRhom2−/− BM cells show a competitive advantage over WT BM cells in their capacity to differentiate into F4/80hiCD11b+ BM-derived macrophages which is time and dose-dependent (supplemental Figure S6). In contrast, the CD45.2-to-CD45.1 ratios in F4/80−CD11b− non-myeloid control population remain unchanged over time in both WT and iRhom2−/− cell mixtures. The in vivo results described above, along with these in vitro data, suggest that iRhom2−/− BM myeloid progenitors have a competitive advantage over WT counterparts in the context of BM reconstitution, possibly because they express higher levels of the CSF1R and, thus, show increased CSF1R-mediated differentiation of macrophages.

Increased proliferation of iRhom2−/− LSK cells in response to CSF1

CSF1 can promote differentiation and proliferation of myeloid progenitor cells from HSC to CMP, GMP, then CDP and MDP [13]. Given the elevated expression of surface CSF1R and repopulation advantage of iRhom2−/− BM cells, we next evaluated the direct influence of CSF1 on iRhom2−/− myeloid progenitor cells. LSKs and GMPs were isolated from BM and cultured in the presence of increasing concentrations of CSF1 in vitro (Figure 5A, B). Surprisingly, only the more primitive LSKs (Figure 5A, D), but not GMPs (Figure 5B, E), from iRhom2−/− mice grew significantly faster than their WT counterparts. Like GMPs, iRhom2−/− monocytes and peritoneal macrophages demonstrated no difference in proliferation or survival from WT cells when cultured with CSF1 in vitro (supplemental Figure S7).

Figure 5. Increased proliferation of iRhom2−/− LSK cells in response to CSF1.

BM LSKs (Lin−SCA-1+c-Kit+) (A, D) and GMPs (Lin−SCA-1−c-Kit+CD34+FcR+) (B, E) sorted from iRhom2 WT (+/+) or KO (−/−) mice were cultured in the presence of absence of 1 or 10 ng/ml of CSF1 (A, B, D, E), or in combination with 2 or 20 ng/ml of SCF (C). Cell numbers and colonies were assessed from day 0 to 7. Phase contrast original magnification: x200 for (D) LSK day 1,2,5 and (E) GMP day 1-2; x40 for (D) LSK day 7 and (E) GMP day 5-7. Scale bar: 100 μm. Means ± s.d. n=4. Data represents 3 independent experiments with similar results. # P<0.05, * P<0.01. Student t test.

The accelerated growth of iRhom2−/− LSKs began after cells were cultured in CSF1 for 2 days and continued for 7 days, evident in both cell numbers and colony size (Figure 5A, D). To avoid the effects of c-kit, another substrate of ADAM17 that supports survival of LSKs [21], only CSF1 was added to the culture medium. There was no difference in cell survival or apoptosis between iRhom2−/− and WT LSKs cultured in CSF1 alone (data not shown). By day 2 in culture in the presence of CSF1, LSKs differentiate into GMPs, and start to proliferate [22]. When SCF was added to the culture medium, iRhom2−/− LSKs still grew faster than those from WT mice (Figure 5C), while there was no difference in growth rate between WT and iRhom2−/− LSKs in the presence of SCF alone (Figure 5C). Furthermore, we did not detect any change in cell surface expression of c-kit on iRhom2−/− LSKs compared to WT cells at steady state (supplemental Figure S8). Thus, it appears unlikely that c-kit is directly involved in the increased growth of iRhom2−/− LSKs in response to CSF1 treatment. Finally, expression of csf1r and iRhom2 (Rhbdf2) mRNA in LSKs was confirmed by real-time RT-PCR (supplemental Figure S9). Taken together, these results suggest that in the absence of iRhom2, primitive hematopoietic progenitor cells showed enhanced differentiation and proliferation in response to CSF1, possibly due to accumulation of CSF1R on their cell surface.

DISCUSSION

ADAM17 controls ectodomain shedding of a wide spectrum of membrane-anchored substrates, yet much remains to be learned about the consequences of shedding events for specific substrates. In the current study, we identified the CSF1R, a known substrate of ADAM17 [10] as one of the top membrane-anchored shedding substrates of ADAM17 in steady-state mEFs. Since CSF1R is known to be required for differentiation of cells of the myeloid lineage, including macrophages and monocytes, we analyzed how inactivation of ADAM17 in immune cells affects cell surface expression of the CSF1R and the development/differentiation of cells in the myeloid lineage. To address this question, we mainly focused on myeloid cells from iRhom2−/− mice, because iRhom2 is required for the function of ADAM17 in these cells, and we corroborated key findings in ADAM17fl/flLysMCre mice. In mice lacking functional ADAM17 in immune cells, but with normal function of other ADAMs [23], we found that CSF1R accumulated on the cell surface of all cell types known to express CSF1R transcript, including myeloid progenitors (CMP, GMP, MDP and CDP), monocytes, tissue macrophages and DCs, as well as populations on which cell surface CSF1R is usually too low to be detected by flow-cytometry in WT mice, such as LSKs and neutrophils. These results indicate that iRhom2/ADAM17-mediated shedding has a key role in regulating the cell surface levels of the CSF1R in the myeloid cell compartment at steady state.

Given the essential role of the CSF1R in driving differentiation, proliferation and survival of the mononuclear phagocyte system, we examined the composition of myeloid cell populations in iRhom2−/− mice. Unexpectedly, despite increased cell surface expression of the CSF1R in the myeloid cell compartment, there was no significant expansion in any of these cell populations in naïve iRhom2−/− mice at steady state. The possibility of insufficient availability of the major CSF1R ligand, CSF1, appears unlikely because iRhom2−/− and WT mice had similar low, but detectable, CSF1 levels in the blood, and because GMP, monocytes and peritoneal macrophages isolated from iRhom2−/− and WT mice showed no difference in proliferation or survival when cultured in CSF1 in vitro. Hence, shedding of CSF1R may not be key to regulation of homeostatic proliferation or survival of myeloid cells under normal conditions; there may be other mechanism(s) that maintains myeloid lineage homeostasis, even in the face of increased expression of surface CSF1R in iRhom2−/− mice.

In contrast to the absence of changes in myeloid cell populations in iRhom2−/− mice at steady state, iRhom2−/− BM progenitors showed a repopulation advantage in the mixed BM chimera experiments in vivo and in vitro when competing with WT progenitors. Among cell types dependent on CSF1R signaling for differentiation/proliferation [11], there were more iRhom2−/− BM progenitor-derived monocytes, tissue macrophages and lung DCs compared to those derived from WT BM progenitors, with different repopulation kinetics. Interestingly, the repopulation advantage of iRhom2−/− monocytes was transient and most pronounced at early stages (4 wk) after BM reconstitution, whereas iRhom2−/− BM-derived tissue macrophages showed an advantage over WT cells relatively late (mostly after 2 months), which increased over time. These findings may reflect differences in CSF1R-dependent expansion and longevity between monocytes and macrophages; monocytes turn over rapidly (half-life ~20 h), while tissue macrophages proliferate slowly (half-life ranging from several days to several months) [24;25]. Recent reports have shown that following BM-transplantation in mice, BM progenitor-derived macrophages acquire similar epigenetic patterns of enhancer/promoter landscapes to yolk sac-derived tissue resident macrophages under the influence of local micro-environment [26], suggesting plasticity of macrophage populations from different origins[24;27;28]. Although in the current study we did not directly evaluate repopulation capacity of yolk sac-derived tissue resident macrophages in iRhom2−/− mice, based on the results from the BM-derived tissue macrophages in the BM chimera experiments, we predict that yolk sac-derived tissue resident macrophages in iRhom2−/− mice may also have enhanced repopulation capacity over WT cells.

In vitro experiments using purified BM progenitor cells indicate that an increased response to CSF1 in the absence of iRhom2 occurs at the more primitive LSK stage, but disappears in GMPs, even though GMPs express more CSF1R than LSKs. These findings suggest that LSKs are more sensitive to change in CSF1R expression levels than GMPs, or a secondary signal from the niche or elsewhere is required for GMP proliferation along with CSF1. Our results corroborate previous reports that CSF1 drives differentiation of HSC [13]. An earlier study using mice with conditional knock out of ADAM17 in the all lymphoid progenitor (ALP) (ADAM17fl/flVav1-iCre mice) showed that Adam17−/− ALPs have increased CSF1R expression but fail to give rise to monocytes or macrophages in transplantation studies [29], consistent with the fact that CSF1R signaling is active only in the myeloid compartment. In the current study, we did not detect CSF1R expression in mature lymphocytes or lymphoid progenitors in the iRhom2−/− mice, or any change in repopulation of iRhom2−/− progenitor-derived T or B cells in the mixed BM chimera experiments.

CSF1R was initially identified as an ADAM17 shedding substrate in PMA and LPS activated monocytes [10], while the trigger(s) for constitutive shedding of CSF1R demonstrated by our current study in naive mice are unclear. Previous studies suggest interaction between TLR and CSF1R signaling pathways; some LPS-induced genes were inhibited by CSF1R signaling in macrophages [30]. Mice deficient in iRhom2 will be useful in future studies to address the interplay between iRhom2/ADAM17 with TLR pathway.

Taken together, our results demonstrate that the CSF1R is a major cell membrane target of the iRhom2/ADAM17 sheddase in myeloid cells. Shedding of CSF1R on the cell surface does not appear to be required for steady-state myeloid cell homeostasis. However, our results demonstrate that iRhom2−/− BM progenitors have an increased capacity to repopulate monocyte and tissue macrophage lineages, presumably due to the increased expression of CSF1R, although we cannot rule out a contribution of other iRhom2/ADAM17 substrates to this process. However, given that CSF1R is critical for development of macrophages/monocytes and was identified as the top membrane-bound shedding substrate for ADAM17 in mEFs, an increase in this receptor provides the most likely explanation for the repopulation advantage of myeloid cells lacking iRhom2. In conclusion, our results suggest that the iRhom2/ADAM17 pathway play a role in non-steady state repopulation of monocytes, tissue macrophages and lung DCs. Therefore, the iRhom2/ADAM17 pathway could be a potential new target to enhance myeloid differentiation and proliferation in conditions such as bone marrow transplantation, trauma and infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

Adult female mice (6-12 wk old) were used in all experiments. C57BL/6 (CD45.2 and CD45.1) mice were bred in-house or purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. iRhom2−/− mice (also referred as iR2−/− mice) were on C57BL6 background [4]. Mice were housed in the animal facility of the Hospital for Special Surgery in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines, and the studies were approved by the Institute of Animal Care and Use Committee.

Proteomics

Primary mEFs were isolated as described before [7;31]. Briefly, the head and viscera of E13.5 embryos from Adam17 WT (+/+) and KO (−/−) mice were removed, and the remaining tissues were minced and digested with 0.25% trypsin for 15 min at 37 °C. Cells were released through mechanical trituration and cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with containing 10% v/v fetal bovine serum and 0.1 U/L penicillin and 0.1 U/L streptomycin for 5-6 passages. Cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) 24 h prior to collection and media was replaced with serum-free, phenol red-free DMEM. Culture supernatants were collected and centrifuged for 10 min at 4 °C before adding EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) (1 mM final), PMSF (phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) (0.5 mM final) and E-64 (N-(trans-Epoxysuccinyl)-L-leucine 4-guanidinobutylamide) (5 μM final). Supernatants were then centrifuged 20 min at 4 °C and passed through a 0.2 μM syringe filter. Each supernatant was concentrated in a 15 mL 3K Amicon Ultra-15 Centrifugal Filter Unit (EMD Millipore), washed with 100 mM HEPES (N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N'-2-ethanesulfonic acid) pH 8 and brought to a final protein concentration of 2 mg/ml.

Sample preparation for liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS): 10 μg Adam17 KO supernatant and 5 μg WT supernatant was used, generating two Adam17 KO samples and one WT sample per replicate. Volume was adjusted to 20 μL using 100 mM HEPES, pH 8 and 10 μL 3% w/v sodium deoxycholate in 100 mM HEPES, pH 8 was then added to each sample. Samples were heated to 99 °C for 5 min and subsequently cooled to room temperature. Dithiothreitol was added to a final concentration of 5 mM and incubated 30 min at 37 °C. Iodoacetamide was added to a final concentration of 15 mM and incubated 20 min at room temperature in the dark. Trypsin (Promega) was added at a protein:protease ratio of 50:1 and incubated at 37 °C for at least 16 h. Samples were diluted in 0.5% acetic acid to pH <2.5 and clarified by centrifugation at 14,000 rcf for 10 min at room temperature. Samples were desalted using C18-Stage Tips [32] and completely dried in a speed vac. Samples were re-suspended in 10 μL 500 mM sodium acetate and 20 μL 200 mM formaldehyde was added to each. CH2O was added to one Adam17 KO sample (light labeled sample), CD2O was added to the other Adam17 KO sample (medium labeled sample), and 13CD2O was added to the WT sample (heavy labeled sample). Immediately following, 3μL 1 M sodium cyanoborohydride was added to the light and medium labeled samples and 3 μL 1M sodium cyanoborodeuteride was added to the heavy labeled sample. Samples were incubated at room temperature in the dark for 60 min before adding 10 μL 3M ammonium chloride and incubating an additional 10 min. 50 μL 10% v/v acetic acid was added and samples were incubated at room temperature in the dark for ≥1h to ensure pH<3. Samples were mixed and desalted by C18-Stage Tips. Samples were eluted from tips, dried in a speed vac and reconstituted in 5% v/v glycerol and 1% v/v ampholytes pH 3-10 (Bio-Rad) and separated on the MicroRotofor Cell as per manufacturer’s instructions (Bio-Rad).

LC-MS/MS and data analysis: Samples were analyzed on a nano-HPLC system (Thermo Scientific) coupled to a LTQ-Orbitrap LX (Thermo Scientific) or QExactive (Thermo Scientific) as previously described[33]. Data were analyzed with MaxQuant software (v1.4.1.2) using default settings against the murine UniProt protein database (July 2012). Light labels were ‘DimethLys0’ and ‘DimethNter0’, medium labels were ‘DimethLys4’ and ‘DimethNter4’, and heavy labels were ‘DimethLys8’ and ‘DimethNter8’. Welche’s t-tests were used to assign statistically significant ratios at FDR <0.02 using Perseus software (v1.4.1.3).

Cell preparation

Single cell suspensions were prepared from blood, bone marrow (BM), spleen, peritoneal lavage, lung, liver, brain and kidney. Briefly, mice were perfused with PBS, then BM was harvested by flushing out cells from the femur and tibia. Peritoneal cells were harvested by lavage of the peritoneal cavity. Spleen, lung, liver, brain, and kidney were digested with collagenase D (Roche) for 45 minutes at 37°C. Cells were forced through a 100 μm strainer and red blood cells were lysed with Ammonium-Chloride-Potassium (ACK) lysis buffer.

Antibodies used for flow cytometry

Fluorochrome conjugated anti-mouse antibodies for flow cytometry (FACS) were purchased from Biolegend or eBioscience: anti-F4/80 (clone BM8), anti-CD11b (M1/70), anti-CD115 (AFS98), anti-Ly6C (HK1.4), anti-Ly6G (1A8), anti-CD3ε (145-2C11), anti-B220 (RA3-6B2), anti-NKp46 (29A1.4), anti-CD11c (N418), anti-MHC class II I-A/I-E (M5/114.15.2), anti-PDCA-1 (927), anti-Gr-1 (RB6-8C5), anti-CD45 (30-F11), anti-CD45.1 (A20), anti-CD45.2 (104), anti-c-Kit (2B8), anti-Sca-1 (D7), anti-CD135 (A2F10), anti-CD34 (MEC14.7), anti-Fc receptor CD16/32 (93). For BrdU (5-Bromo-2'-deoxyuridine) staining, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 1 mg of BrdU (BD Bioscience), and BM cells were isolated later. Cells were first stained for surface markers, and then stained for BrdU using a BrdU staining kit (BD Bioscience) following the manufacturer’s instruction. Data was acquired on an upgraded 11-color FACS Calibur cytometer (Becton Dickinson/Cytex). FACS data was analyzed using Flowjo software.

Mixed bone marrow chimera

WT CD45.1 mice were irradiated (950 cGy) on a RS 2000 X-ray irradiator, then intravenously infused with 5 × 106 BM cells from iRhom2 WT (+/+) or KO (−/−) CD45.2 mice mixed at 1 : 1 ratio with 5 × 106 BM cells from WT CD45.1 mice. Mouse organs were harvested for analysis of cell populations at various time points.

Hematopoietic progenitor cell culture

BM cells were enriched with a mouse hematopoietic progenitor isolation kit (Stemcell), stained with progenitor cell markers, then sorted for LSKs (Lin−SCA-1+c-Kit+) and granulocyte-macrophage progenitors (GMPs) (Lin−SCA-1−c-Kit+CD16/32+CD34+) on a Becton-Dickinson Vantage cell sorter (Becton Dickinson), with >95% cell purity. Purified LSKs and GMPs were cultured in 96-well plate in the presence of various concentrations of CSF1 in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and penicillin/streptomycin for up to 7 days. Cells were counted and visualized under phase-contrast light microscope at various time points.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± s.d. or mean ± s.e.m, as indicated. Normal distribution of data was tested by Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Student’s t-test was used for statistic analysis of FACS. P<0.05 was assigned to reject null hypothesis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is supported in part by NIH grant GM64750 (CPB) and the Lupus Research Institute (JES).

Abbreviation used

- BM

bone marrow

- CSF1R

colony stimulating factor 1 receptor

- ADAM17

A disintegrin and metalloprotease 17

- iRhom2

inactive rhomboid protein 2

- mEF

mouse embryonic fibroblasts

- LSK

Lin−SCA-1+c-Kit+ cells

- GMP

granulocyte-macrophage progenitors

- CMP

common myeloid progenitor

- CDP

common dendritic progenitors

- MDP

monocyte/macrophage precursors

- cDC

conventional dendritic cells

- pDC

plasmacytoid dendritic cells

- WT

wild type

- KO

knockout

Footnotes

The supplemental material includes: supplemental methods and Supplemental Figures S1-9.

AUTHORSIHP

Contribution: X.Q. designed and performed research, collected data, analyzed and interpreted data, performed statistical analysis, and wrote the manuscript. L.R. performed research, collected data, analyzed and interpreted data, performed statistical analysis, and wrote the manuscript; A.M., Y. L, performed research and collected data; P.R., P.I., T.M., M.M., C.M.O. performed research; D.M. and T.W.M. contributed vital mouse strains; C.B. and J.E.S. designed studies, reviewed data and wrote manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Blobel CP. ADAMs: key components in EGFR signalling and development. Nat.Rev.Mol.Cell Biol. 2005;6:32–43. doi: 10.1038/nrm1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adrain C, Zettl M, Christova Y, Taylor N, Freeman M. Tumor necrosis factor signaling requires iRhom2 to promote trafficking and activation of TACE. Science. 2012;335:225–228. doi: 10.1126/science.1214400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maretzky T, McIlwain DR, Issuree PD, Li X, Malapeira J, Amin S, Lang PA, Mak TW, Blobel CP. iRhom2 controls the substrate selectivity of stimulated ADAM17-dependent ectodomain shedding. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2013;110:11433–11438. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302553110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McIlwain DR, Lang PA, Maretzky T, Hamada K, Ohishi K, Maney SK, Berger T, Murthy A, Duncan G, Xu HC, Lang KS, Haussinger D, Wakeham A, Itie-Youten A, Khokha R, Ohashi PS, Blobel CP, Mak TW. iRhom2 regulation of TACE controls TNF-mediated protection against Listeria and responses to LPS. Science. 2012;335:229–232. doi: 10.1126/science.1214448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Issuree PD, Maretzky T, McIlwain DR, Monette S, Qing X, Lang PA, Swendeman SL, Park-Min KH, Binder N, Kalliolias GD, Yarilina A, Horiuchi K, Ivashkiv LB, Mak TW, Salmon JE, Blobel CP. iRHOM2 is a critical pathogenic mediator of inflammatory arthritis. J.Clin.Invest. 2013;123:928–932. doi: 10.1172/JCI66168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horiuchi K, Kimura T, Miyamoto T, Takaishi H, Okada Y, Toyama Y, Blobel CP. Cutting edge: TNF-alpha-converting enzyme (TACE/ADAM17) inactivation in mouse myeloid cells prevents lethality from endotoxin shock. J.Immunol. 2007;179:2686–2689. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.5.2686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li X, Maretzky T, Weskamp G, Monette S, Qing X, Issuree PD, Crawford HC, McIlwain DR, Mak TW, Salmon JE, Blobel CP. iRhoms 1 and 2 are essential upstream regulators of ADAM17-dependent EGFR signaling. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2015;112:6080–6085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1505649112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peschon JJ, Slack JL, Reddy P, Stocking KL, Sunnarborg SW, Lee DC, Russell WE, Castner BJ, Johnson RS, Fitzner JN, Boyce RW, Nelson N, Kozlosky CJ, Wolfson MF, Rauch CT, Cerretti DP, Paxton RJ, March CJ, Black RA. An essential role for ectodomain shedding in mammalian development. Science. 1998;282:1281–1284. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5392.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gooz M. ADAM-17: the enzyme that does it all. Crit Rev.Biochem.Mol.Biol. 2010;45:146–169. doi: 10.3109/10409231003628015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rovida E, Paccagnini A, Del Rosso M, Peschon J, Dello Sbarba P. TNF-alpha-converting enzyme cleaves the macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor in macrophages undergoing activation. J.Immunol. 2001;166:1583–1589. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.3.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hume DA, MacDonald KP. Therapeutic applications of macrophage colony-stimulating factor-1 (CSF-1) and antagonists of CSF-1 receptor (CSF-1R) signaling. Blood. 2012;119:1810–1820. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-379214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin H, Lee E, Hestir K, Leo C, Huang M, Bosch E, Halenbeck R, Wu G, Zhou A, Behrens D, Hollenbaugh D, Linnemann T, Qin M, Wong J, Chu K, Doberstein SK, Williams LT. Discovery of a cytokine and its receptor by functional screening of the extracellular proteome. Science. 2008;320:807–811. doi: 10.1126/science.1154370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mossadegh-Keller N, Sarrazin S, Kandalla PK, Espinosa L, Stanley ER, Nutt SL, Moore J, Sieweke MH. M-CSF instructs myeloid lineage fate in single haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2013;497:239–243. doi: 10.1038/nature12026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dai XM, Ryan GR, Hapel AJ, Dominguez MG, Russell RG, Kapp S, Sylvestre V, Stanley ER. Targeted disruption of the mouse colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor gene results in osteopetrosis, mononuclear phagocyte deficiency, increased primitive progenitor cell frequencies, and reproductive defects. Blood. 2002;99:111–120. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li J, Chen K, Zhu L, Pollard JW. Conditional deletion of the colony stimulating factor-1 receptor (c-fms proto-oncogene) in mice. Genesis. 2006;44:328–335. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sasmono RT, Oceandy D, Pollard JW, Tong W, Pavli P, Wainwright BJ, Ostrowski MC, Himes SR, Hume DA. A macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor-green fluorescent protein transgene is expressed throughout the mononuclear phagocyte system of the mouse. Blood. 2003;101:1155–1163. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-02-0569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Biswas SK, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and interaction with lymphocyte subsets: cancer as a paradigm. Nat.Immunol. 2010;11:889–896. doi: 10.1038/ni.1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pollard JW. Trophic macrophages in development and disease. Nat.Rev.Immunol. 2009;9:259–270. doi: 10.1038/nri2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chitu V, Stanley ER. Colony-stimulating factor-1 in immunity and inflammation. Curr.Opin.Immunol. 2006;18:39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haran-Ghera N, Krautghamer R, Lapidot T, Peled A, Dominguez MG, Stanley ER. Increased circulating colony-stimulating factor-1 (CSF-1) in SJL/J mice with radiation-induced acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is associated with autocrine regulation of AML cells by CSF-1. Blood. 1997;89:2537–2545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cruz AC, Frank BT, Edwards ST, Dazin PF, Peschon JJ, Fang KC. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha-converting enzyme controls surface expression of c-Kit and survival of embryonic stem cell-derived mast cells. J.Biol.Chem. 2004;279:5612–5620. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312323200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rieger MA, Hoppe PS, Smejkal BM, Eitelhuber AC, Schroeder T. Hematopoietic cytokines can instruct lineage choice. Science. 2009;325:217–218. doi: 10.1126/science.1171461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Christova Y, Adrain C, Bambrough P, Ibrahim A, Freeman M. Mammalian iRhoms have distinct physiological functions including an essential role in TACE regulation. EMBO Rep. 2013;14:884–890. doi: 10.1038/embor.2013.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hashimoto D, Chow A, Noizat C, Teo P, Beasley MB, Leboeuf M, Becker CD, See P, Price J, Lucas D, Greter M, Mortha A, Boyer SW, Forsberg EC, Tanaka M, van RN, Garcia-Sastre A, Stanley ER, Ginhoux F, Frenette PS, Merad M. Tissue-resident macrophages self-maintain locally throughout adult life with minimal contribution from circulating monocytes. Immunity. 2013;38:792–804. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yona S, Kim KW, Wolf Y, Mildner A, Varol D, Breker M, Strauss-Ayali D, Viukov S, Guilliams M, Misharin A, Hume DA, Perlman H, Malissen B, Zelzer E, Jung S. Fate mapping reveals origins and dynamics of monocytes and tissue macrophages under homeostasis. Immunity. 2013;38:79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lavin Y, Winter D, Blecher-Gonen R, David E, Keren-Shaul H, Merad M, Jung S, Amit I. Tissue-resident macrophage enhancer landscapes are shaped by the local microenvironment. Cell. 2014;159:1312–1326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schulz C, Gomez PE, Chorro L, Szabo-Rogers H, Cagnard N, Kierdorf K, Prinz M, Wu B, Jacobsen SE, Pollard JW, Frampton J, Liu KJ, Geissmann F. A lineage of myeloid cells independent of Myb and hematopoietic stem cells. Science. 2012;336:86–90. doi: 10.1126/science.1219179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gomez PE, Klapproth K, Schulz C, Busch K, Azzoni E, Crozet L, Garner H, Trouillet C, de Bruijn MF, Geissmann F, Rodewald HR. Tissue-resident macrophages originate from yolk-sac-derived erythro-myeloid progenitors. Nature. 2015;518:547–551. doi: 10.1038/nature13989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Becker AM, Walcheck B, Bhattacharya D. ADAM17 limits the expression of CSF1R on murine hematopoietic progenitors. Exp.Hematol. 2015;43:44–52. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sester DP, Trieu A, Brion K, Schroder K, Ravasi T, Robinson JA, McDonald RC, Ripoll V, Wells CA, Suzuki H, Hayashizaki Y, Stacey KJ, Hume DA, Sweet MJ. LPS regulates a set of genes in primary murine macrophages by antagonising CSF-1 action. Immunobiology. 2005;210:97–107. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sahin U, Weskamp G, Zheng Y, Chesneau V, Horiuchi K, Blobel CP. A sensitive method to monitor ectodomain shedding of ligands of the epidermal growth factor receptor. Methods Mol.Biol. 2006;327:99–113. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-012-X:99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rappsilber J, Ishihama Y, Mann M. Stop and go extraction tips for matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization, nanoelectrospray, and LC/MS sample pretreatment in proteomics. Anal.Chem. 2003;75:663–670. doi: 10.1021/ac026117i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huesgen PF, Lange PF, Rogers LD, Solis N, Eckhard U, Kleifeld O, Goulas T, Gomis-Ruth FX, Overall CM. LysargiNase mirrors trypsin for protein C-terminal and methylation-site identification. Nat.Methods. 2015;12:55–58. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.