Abstract

Quorum sensing auto-inducers of the N-acyl homoserine lactone (AHL) type produced by Gram-negative bacteria have different effects on plants including stimulation on root growth and/or priming or acquirement of systemic resistance in plants. In this communication the influence of AHL production of the plant growth promoting endophytic rhizosphere bacterium Acidovorax radicis N35 on barley seedlings was investigated. A. radicis N35 produces 3-hydroxy-C10-homoserine lactone (3-OH-C10-HSL) as the major AHL compound. To study the influence of this QS autoinducer on the interaction with barley, the araI-biosynthesis gene was deleted. The comparison of inoculation effects of the A. radicis N35 wild type and the araI mutant resulted in remarkable differences. While the N35 wild type colonized plant roots effectively in microcolonies, the araI mutant occurred at the root surface as single cells. Furthermore, in a mixed inoculum the wild type was much more prevalent in colonization than the araI mutant documenting that the araI mutation affected root colonization. Nevertheless, a significant plant growth promoting effect could be shown after inoculation of barley with the wild type and the araI mutant in soil after 2 months cultivation. While A. radicis N35 wild type showed only a very weak induction of early defense responses in plant RNA expression analysis, the araI mutant caused increased expression of flavonoid biosynthesis genes. This was corroborated by the accumulation of several flavonoid compounds such as saponarin and lutonarin in leaves of root inoculated barley seedlings. Thus, although the exact role of the flavonoids in this plant response is not clear yet, it can be concluded, that the synthesis of AHLs by A. radicis has implications on the perception by the host plant barley and thereby contributes to the establishment and function of the bacteria-plant interaction.

Keywords: Acidovorax radicis, 3-OH-C10-homoserine lactone, plant growth promoting bacteria (PGPB), systemic plant responses, flavonoids, endophytes

Introduction

In the rhizosphere, microbes are selectively enriched as compared to the surrounding bulk soil due to the availability of plant root exudates. Plant growth promoting bacteria (PGPB) are part of this microbial community exhibiting beneficial effects on plants, like biocontrol activity toward plant pathogenic organisms and promotion of plant growth due to enhanced supply of limiting nutrients like phosphate, nitrogen and essential trace elements like ferric iron. Induced systemic resistance (ISR) caused by root associated bacteria enhances the defense even in foliar tissues for later pathogen attack (Lugtenberg and Kamilova, 2009). Many molecules, so-called MAMPS (microbial associated molecular patterns) including lipopolysaccharide (LPS), exopolysaccharide (EPS), and microbial flagella elicit ISR-responses (Berendsen et al., 2012). In addition, small secondary metabolites such as the siderophore pyoverdin, the antibiotics 2,4-DAPG and lipopeptides, pseudobactins, pyocyanin, and certain biosurfactants belong to the complex spectrum of elicitors of plant responses upon contact with microbes (De Vleesschauwer et al., 2008; De Vleesschauwer and Höfte, 2009; Guillaume et al., 2012; Chowdhury et al., 2015). Also volatile organic compounds, for instance 2R, 3R-butanediol, were shown to induce plant resistance (Cortes-Barco et al., 2010). PGPB cause ISR because they initiate a priming of specific initial plant responses, upon surface or endophytic colonization. The priming status includes no upregulation of pathogen related (PR) genes, which is required in systemic acquired resistance (SAR), known to be induced by plant pathogens. Upon additional specific stress situations, PR proteins were potentially activated (Pieterse et al., 1996; Ahn et al., 2007). Quorum sensing (QS) compounds of Gram-negative bacteria, like N-acyl homoserine lactones (AHL), were also found to cause systemic ISR-like responses in different plants (De Vleesschauwer et al., 2008; De Vleesschauwer and Höfte, 2009; Cortes-Barco et al., 2010). Compared to the already advanced knowledge on the responses of plants to a large number of systemic defense elicitors, details about the perception of plants regarding these QS signal molecules are still scarce, despite the importance these bacterial messenger molecules must have considering their presence throughout the entire plant evolution.

In many Gram-negative bacteria, luxI-luxR type quorum sensing (QS) systems use N-acyl-homoserine lactones (AHLs) as auto-inducing signals (Fuqua and Greenberg, 2002). The length of the acyl-residues of AHLs produced by the I-gene, varies from 4 to 18 carbon atoms and hydroxyl- or carbonyl-group substitutions are found at the C3-position. Most of these AHL signal compounds are able to diffuse through bacterial membranes freely, while specific transporters were found for AHLs with long chain fatty acid residues (Krol and Becker, 2014). Specific luxR-type receptors or transcription factors bind AHL signal molecules at elevated intracellular concentrations leading to increased expression of the luxI-gene. Subsequently, specific gene expression is activated or suppressed by binding and releasing the AHL-LuxR transcription factor from specific gene promoter regions. AHLs dependent QS circuits are global regulons; they control a wide range of biological functions including swarming motility, bioluminescence, plasmid conjugative transfer, biofilm formation, antibiotic biosynthesis, and the production of virulence factors in plant and animal pathogens (Eberl, 1999; Waters and Bassler, 2005). Since these AHL autoinducers also convey information about the surrounding and habitat quality of the cells, AHLs play a central role in optimizing the expression of their genetic repertoire and thus have an important efficiency optimizing function (Hense et al., 2007). It turned out that AHLs not only allow bacterial populations to interact with each other but are also recognized as signals by their eukaryotic hosts. C12- and C16- side chain AHL molecules are able to induce a specific and extensive proteome response in Medicago truncatula (Mathesius et al., 2003). Using in situ bioreporter bacteria for AHLs, a production of AHLs by Serratia liquefaciens MG1 and Pseudomonas putida IsoF colonizing the rhizoplane of tomato roots were demonstrated (Gantner et al., 2006). These strains exert beneficial effects on tomato plants when inoculated to roots, since it could be shown, that the ISR-like response toward the leaf attacking fungus Alternaria alternata was dependent on the production of C6-and C8-side chain AHLs by S. liquefaciens MG1 (Schuhegger et al., 2006). In contrast, in Arabidopsis thaliana, short side chain AHLs induced phytohormonal changes in the plants and an enhancement of root growth, but no priming of pathogen response (von Rad et al., 2008). In recent years, a series of specific perception responses in different plants were reported toward the addition of long-side chain AHLs and AHL producing bacteria to roots, as summarized by Schikora et al. (2016). While most of the effects of AHLs on plants were documented when AHLs were applied as pure compounds to the medium at the roots, much less is known about how AHL production by PGPB located on or inside the root contributes to the plant's perception of these bacteria. This is not only because root colonizers produce many other substances besides AHLs the plant will respond to, but also because due to the variable bacterial colonization pattern on the root surface, which ranges from microcolonies to dense biofilms. Therefore the AHL concentration will vary quite a lot locally, which is not well-reflected by the application of an average AHL concentration to the plant growth medium.

In plant response toward bacteria flavonoids play an important role. A high diversity of flavonoids are known in different plants (Hassan and Mathesius, 2012). In barley, the most abundant flavonoids are saponarin and lutonarin (Kamiyama and Shibamoto, 2012). Flavonoids contribute to biotic or abiotic stress resistance toward oxidative damage. They are known for their antioxidant, fungicide, bactericide, and anti-pest properties (Treutter, 2005; Cushnie and Lamb, 2011; Hassan and Mathesius, 2012). Flavonoid biosynthesis genes are expressed in a tightly regulated manner and include early flavonoid biosynthesis genes (EBG) like chalcone synthase (CHS; Hassett et al., 1999), chalcone-flavonone isomerase (CFI), 4-coumarate-CoA ligase (4-CL), and UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT; Besseau et al., 2007). The AHLs 3-oxo-C12-HSL and 3-oxo-C14-HSL were found to induce several of these flavonoid synthesis genes (Mathesius et al., 2003; Schenk et al., 2014).

The model organism used in this study was the type strain N35 of Acidovorax radicis, an endophytic Gram-negative bacterium originally isolated from wheat roots (Li et al., 2011). In the genus Acidovorax, pathogenic as well as saprophytic or beneficial species are known. The majority of the Acidovorax spp. are phytopathogenic for diverse plants, but there are also ubiquitously distributed saprophytic environmental Acidovorax spp. in rhizosphere and water habitats, like A. delafieldii, A. defluvii, A. temperans, and A. soli which are more closely related to A. radicis. A. radicis N35 can colonize the surface and endosphere of barley roots and shows the ability to promote barley growth in soil under certain conditions. In its genome, a homologous luxI-luxR type gene pair was identified (Li et al., 2011). The N-acyl-homoserine lactone produced by A. radicis N35 was identified as N-(3-OH-C10)-homoserine lactone using high performance liquid chromatography and FT-ICR-mass spectrometry (Fekete et al., 2007).

The objective of this study was to investigate the effect of AHL production of A. radicis on root colonization and the perception by barley plants. Therefore, we compared the wild type strain N35 and an AHL negative mutant with disrupted araI gene in their influence on barley seedlings using RNA-sequencing of leaves of inoculated barley plants and q-PCR. The analysis was focused on the flavonoid biosynthesis as part of the defense response. The results indicated that the AHLs produced by A. radicis N35 reduced systemic defense responses like flavonoid accumulation in response to the colonization by this endophytic bacterium.

Materials and methods

Strains, culture media, and growth conditions

All strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. A. radicis N35 was isolated from surface sterilized wheat roots (Li et al., 2011). It was grown in NB complex medium at 30°C at 180 rpm. Kanamycin (Km, 50 μg/ml) was supplemented to growth media of YFP-labeled A. radicis N35. The A. radicis N35 araI mutant was grown in NB medium containing 20 μg/ml tetracycline (Tc); for the GFP-labeled A. radicis N35 araI mutant, Km 50 μg/ml and Tc 20 μg/ml was added. Agrobacterium tumefaciens A136 (with plasmids pCF218 and pCF372) was cultured in NB medium with Tc 5 μg/ml.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids.

| Strains and plasmids | Relevant characteristics | Source |

|---|---|---|

| A. radicis N35 | Wild type | Li et al., 2011 |

| A. radicis N35 YFP | Wild type, labeled with YFP, KmR | Li et al., 2012 |

| A. radicis N35 araI::tet | AHL− mutant, TcR | This study |

| A. radicis N35 araI::tet C | AHL− mutant, complemented with plasmid pBBR1MCS-2-AraI, TcR, KmR | This study |

| A. radicis N35 araI::tet GFP | AHL− mutant, GFP labeled with plasmid pBBR1MCS-2-GFP, TcR, KmR | This study |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens A136 | AHL biosensor with pCF218, pCF372 | Stickler et al., 1998 |

| pBBR1MCS-2-GFP | GFP expression vector, KmR | Li et al., 2012 |

| pBBR1MCS-2-YFP | YFP expression vector, KmR | This study |

| pBBR1MCS-2-AraI | araI gene expression vector, KmR | This study |

For the inoculation of barley plants, 50 ml overnight culture of A. radicis N35 wild type and araI mutant strains were harvested using 4000 g by centrifugation (Eppendorf 5417R, Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) for 10 min at room temperature, and the supernatant was discarded. The cells were washed twice with 50 ml of 1x PBS and thereafter the cell concentration was adjusted to an optical density (OD435nm) of 1.5 (equal to 108 cfu/ml) in 20 ml 1x PBS solution measured using a spectral photometer (CE3021, Cecil, Cambridge, England).

Characterization of AHL production using AHL biosensor strain

AHL production of A. radicis N35 and its AHL deficient araI mutant were examined via a traI-lacZ fusion sensor plasmids in A. tumefaciens A136, which lacks the Ti plasmid and harbors the two plasmids pCF218 and pCF372. These two plasmids encode the traR and traI-lacZ fusion genes, respectively. These bio-reporter constructs allow highly efficient detection of AHLs (Stickler et al., 1998). The sensor strain was streaked to the center of an LB or NB agar plate containing 40 μg/ml X-gal, and the test bacterial strains were cross-streaked close to the biosensor. The culture plates were incubated at 30°C in the dark for 24–48 h. AHL production was detected via the activation of the reporter fusion traI-lacZ. In the presence of AHLs, beta-galactosidase activity was induced at the contact area of test and sensor strain. The metabolization of X-gal to the insoluble blue colored 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-hydroxyindole dimer indicates the presence of AHL molecules.

Construction of an araI mutant strain

For knock-out mutagenesis in A. radicis N35, the sacB based gene replacement vector pEX18Gm described by Hoang et al. (1998) was used. First, a DNA cassette was constructed, which carried the araI target gene (amplified with primer pair AHLsyn-s2 GCCAGCTTGTCATAGGACTC and AHLsyn-as2 ATGCACCTCCAGAAAACG) disrupted by a Tc antibiotic marker (tet gene amplified with primer pair TcR-s AAAGTCTACTCAGGTCGAGG and TcR-as3 AAAGTAGACGACGAAAGGC). This cassette was cloned into the gene replacement vector pEX18Gm. Subsequently this constructed gene replacement plasmid was transferred into electrocompetent A. radicis N35 cells by electroporation. In the target cell a homologous recombination event occurred after pairing of the constructed DNA cassette with the homologous region in the genome of A. radicis N35, which led to an insertion of the whole constructed pEX18 plasmid into the genome of N35. The cells with integrated plasmid were selected on NB medium containing antibiotics. These merodiploids were resolved by plating on NB medium containing 5% sucrose, which led to cell death if the sacB gene was expressed. Only cells where the sacB gene together with the gentamycin selective marker was eliminated from the genome by a second homologous recombination could survive on sucrose containing medium. The resulting insertion mutants A. radicis N35 araI::tet carried a disrupted dysfunctional araI gene (Figure S1). The success of the knock-out mutagenesis was verified with PCR using the araI specific primers and by sequencing of the PCR products (ABI Prism, Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA). AHL production was then visualized by the A. tumefaciens A136 AHL biosensor as described above.

Construction of fluorescence labeled A. radicis N35 and araI mutant strains

For YFP-labeling of A. radicis N35 araI::tet, plasmid pBBR1MCS-2-YFP, a YFP expressing broad-host range vector, and for GFP-labeling of the N35 wild type, plasmid pBBR1MCS-2-GFP were used. After isolation using a NucleoSpin plasmid kit (Macherey & Nagel, Düren, Germany) the plasmid was transferred to electro-competent cells of A. radicis N35 as described by Dower et al. (1988). Electroporation was performed with a Gene Pulser instrument (Bio-Rad, Munich, Germany) using a voltage of 2.5 kV for 4.5–5.5 ms. The resulting transformants were selected on Km containing NB plates and examined for specific fluorescence with an epifluorescence microscope at an excitation wavelength of 488 nm.

Inoculation and growth of barley seedlings in axenic system

Before germination, seeds of barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) cultivar Barke were surface sterilized to eliminate microbial contaminations using the method described by Rothballer et al. (2008). The method was slightly modified by using antibiotics (streptomycin 250 μg/ml and penicillin 600 μg/ml) for 20 min before testing the seeds on NB plates for 2 days at 30°C in the dark for contaminations. After washing at least three times in sterilized water, 2 days old axenic barley seedlings with comparable root lengths of about 2 cm were selected for inoculation according to Li et al. (2012). Seeds were immersed in suspensions of A. radicis N35 and its derivative strains for 1 h before planting. For the inoculation with single bacterial strains or a bacterial mixture (v/v 1:1), the 2 days old barley seedlings were incubated in the bacterial suspension for 1 h at room temperature. Axenic cultivation of barley was performed in sealed and autoclaved glass tubes (3 cm width, 50 cm length, AG, Mainz, Germany) filled with 50 g autoclaved glass beads and 10 ml of sterile Murashige and Skoog mineral salt medium (Duchefa Biochemie, Haarlem, The Netherlands). The barley seedlings were grown at a 12 h photoperiod (metal halide lamps of 400 W) under a 23°C / 18°C day/night cycle for 10 days maximum until three-leaf stage in a growth chamber. The roots were harvested by taking the whole plant out of the glass tube, and rinsing off the adhering material with sterile 1x PBS.

Visualization of fluorescence protein labeled bacteria

To visualize the GFP or YFP tagged A. radicis N35 colonizing barley roots, freshly harvested roots of barley were embedded in Citifluor and placed on glass slides. For each inoculation 6 root pieces of about 1 cm were observed. The fluorescence was detected using a confocal laser scanning microscope, CLSM 510 Meta (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). The excitation wavelength at 488 nm was produced by an argon ion laser, the others at 543 and 633 nm by helium/neon lasers. Barley roots show auto-fluorescence which allows the visualization of the root structure. In the CLSM-images, roots were shown in magenta, GFP- labeled bacteria in green, and YFP-labeled bacteria in red color. CLSM lambda mode was used to discriminate between the very similar emission wavelengths of 510 nm for GFP and 530 nm for YFP (excitation for both 488 nm).

Visualization of bacteria using fluorescence in situ hybridization

The FISH-method as described in Manz et al. (1992) and Amann et al. (1991) was applied modified for root samples as described in Rothballer et al. (2015). For A. radicis N35 the specific probe ACISP 145 (TTTCGCTCCGTTATCCCC), combined with an equimolar mixture of the universal bacterial probes EUB 338 I (GCTGCCTCCCGTAGGA), EUB 338 II (GCAGCCACCCGTAGGTGT), and EUB 338 III (GCTGCCACCCGTAGGTGT) were used. The specific fluorescence label was visualized by a CLSM using appropriate excitation wavelengths.

Soil cultivation of barley and sample preparation

For the cultivation of barley in soil, commercial “Graberde” (nutrient limited substrate, Alpenflor, Weilheim, Germany) was mixed with sand (v/v 1:1). Each pot (10 cm height, 8 cm diameter) was filled with the same volume of soil substrate. One liter of tap water was added to initially water the pots. Barley seeds were germinated on paper towel by incubation at room temperature for 3 days (non-sterile conditions). Seedlings without inoculation were used as control. For bacterial inoculation, seeds were treated with cell suspensions of A. radicis N35 or the A. radicis N35 araI mutant (108 cells ml−1 per seedling) for 1 h, as described above. In the plant growth promotion experiment for each treatment 15 pots with only one plant per pot were cultivated for 2 weeks or 2 months. The plants were watered twice a week. Throughout the experiment, the plants were fertilized once each week with Hoagland solution (10 ml 50x stock, diluted in 1 l water). Barley plants were grown under greenhouse conditions at temperatures of 15–25°C during the day and 10–15°C during the night.

For RNA-sequencing, q-PCR and HPLC analysis for each treatment four leaves of 2 weeks old barley seedlings, inoculated 10 days prior to harvest were pooled. At this time point under these cultivation conditions plants were in the three leave developmental stage and their height was <20 cm excluding roots. Always the second leaves were harvested. The leaves were shock frozen in liquid nitrogen and ground in a mortar resulting in about 150 mg of sample material. Fifty milligrams of this homogenate was transferred to a 2 ml Eppendorf tube and used for RNA or flavonoid extraction.

RNA-sequencing

Total RNA was isolated from the prepared barley leave samples using RNeasy plant mini kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instruction. For each sample cDNA was generated using high capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA). cDNA-libraries were sequenced by the KFB Regensburg (Regensburg, Germany) using a HiSeq 2500 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) in single-read mode running 100 cycles. Bioinformatic analysis was performed as described by Dugar et al. (2013). To ensure high sequence quality, Illumina reads in FASTQ format were trimmed with a cutoff phred score of 20 by the program fastq_quality_trimmer from FASTX-Toolkit version 0.0.13. The alignment of reads, coverage calculation, genewise read quantification, and differential gene expression were performed with READ emption which was relying on segemehl and DEseq version X (Hoffmann et al., 2009). Visual inspection of the coverages was performed using the integrated genome browser (IGB, http://bioviz.org/igb/index.html).

q-PCR

Isolation of total RNA and generation of cDNA were performed as described above. Quantitative PCR (q-PCR) was performed using the primers as listed in Table 2 and the SYBR green kit (PeQSTAR) of the real-time PCR system (PeQSTAR SEQ, VWR, Darmstadt, Germany). All primer pairs were verified by melting curves showing only one peak and a slope value close to −3.33. Transcript accumulation was analyzed using relative quantification with the software sigma plot. The q-PCR results are the average of three technical repetitions per sample and five independent plant inoculation experiments.

Table 2.

Primer used in qPCR-analysis.

| Genes | Primer name | Slope value | Primer sequence | Gene name |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MLOC_67149 | Q1 | −3.48 | AAGGCATGGGAGATGGTTGG | F-Box family-3(fb-3) |

| TATCATGGCGTCCCACACG | ||||

| MLOC_10956 | Q20 | −3.62 | GCCAGAAGCCATATCTGCAC | UDP-glycosyltransferase-like protein (UGT) |

| GCAGAAAAACTCACCGGAGC | ||||

| MLOC_58764 | Q29 | −3.35 | TGACACCCCTGCTTCGTTAG | 4-coumarate:CoA ligase (4-CL) |

| ACGACAGCGACCTGTGTTAG | ||||

| MLOC_5324 | Q30 | −3.74 | CTTCGACGCACTTGTCTCGG | Chalcone-flavonone isomerase (CFI) |

| ACTGCGACCCCTTGATCTCC | ||||

| MLOC_74116 | Q32 | −3.87 | CCGACTACCCGGACTACTAC | Chalcone synthase (CHS) |

| TGTACCTCTTCCTGATCTGCG | ||||

| MLOC_72837 | Q24 | −3.33 | TGCTGCACAACTTTCACTCC | Chaperone protein (DnaJ) |

| ACTGAAACTCCCATCCCAGC | ||||

| MLOC_59602 | Q13 | −3.25 | ACTGAAACTCCCATCCCAGC | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase (PRT1) |

| TAGACCCTCCGCTGGTATCC |

HPLC quantification of flavone glycosides in barley leaves

Ten microliters of methanol (HPLC-grade) was added for every mg of frozen sample material prepared as described above. The samples were then vortexed for 1 h on a lab shaker at 700 rpm in the dark. Samples were then centrifuged for 10 min at 11,000 rpm. The supernatants were transferred to a new cap and stored until HPLC-measurement at −80°C. For HPLC analysis, a reversed-phase HPLC system was applied. A linear gradient over 45 min was applied with 100% solution A (2% formic acid containing 0.1% ammonium formate) to 100% solution B (0.1% ammonium formate in 88% methanol) and maintained for another 5 min. Finally, the absorbance of the eluent was measured at 280 nm (Yin et al., 2012).

Results

Construction of AHL synthase mutant and araI complemented strain

To investigate the QS function in A. radicis N35, an AHL deficient mutant was constructed by disrupting the AI synthase gene araI with a tetracycline resistance gene (1.5 Kb). A complementary strain was produced by cloning the A. radicis wild type araI gene into the broad host range vector pBBR1MCS-2 and transferring this construct into the araI knock-out strain. PCR amplification with araI specific primers using as a template a complete DNA extract (containing genomic and plasmid DNA) from the araI mutant and complemented mutant resulted in the expected band sizes (Figure 1A). Subsequent sequencing verified the identity of the PCR amplificates and correct construction of the knock-out cassette and complementary plasmid. To test the AHL production, the AHL biosensor A. tumefaciens A136 (carrying pCF218 or pCF372) was applied. This strain can detect various types of AHLs, especially C10-HSL including the hydroxyl- or oxy-derivative at position C3 (Stickler et al., 1998). Figure 1B shows AHL production indicated by the blue color only for the wild type and the complemented araI mutant, and not for the uncomplemented mutant, which proves the successful knock-out of the araI gene.

Figure 1.

PCR verification (A) and a galactosidase biosensor plate assay detecting AHL production (B) of the A. radicis N35 wildtype, araI knock-out mutant (araI::tet), and complemented araI knock-out mutant (araI::tet C).

Colonization of roots using differentially fluorescence labeled wild type and araI mutant strains

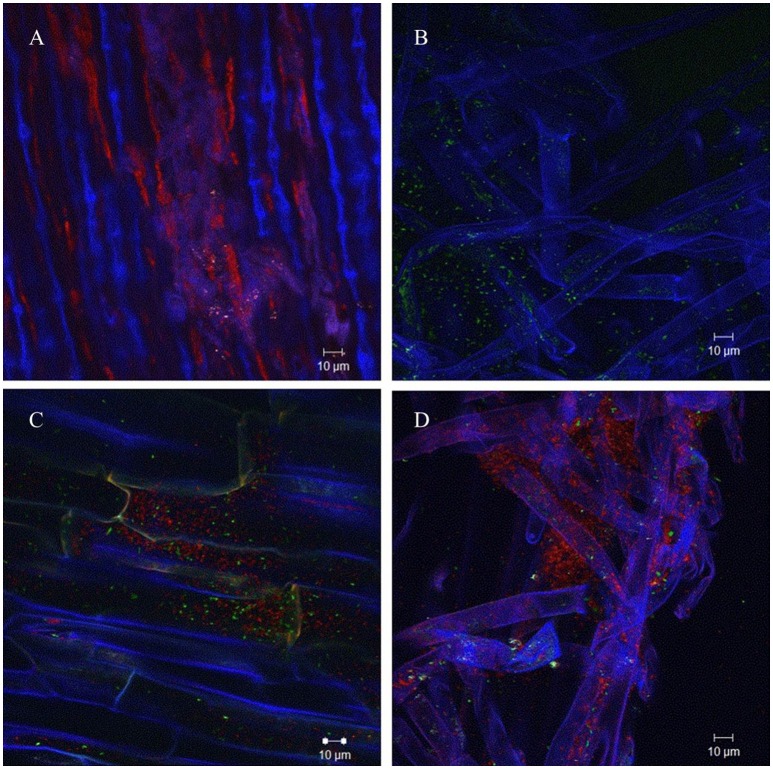

In order to analyze if AHL production of A. radicis N35 had an influence on the colonization ability on barley roots, differentially GFP/YFP-labeled wild type and araI mutant strains were applied. The differentially fluorescence labeled bacteria were applied to barley roots separately as well as in equal mixtures, and the barley seedlings were cultivated under axenic conditions for 1 week. After harvesting and washing the roots, the colonization behavior of wild type and araI mutant on the roots was examined using a CLSM in lambda mode, which allows to distinguish the fluorescence of GFP and YFP based on their specific emission spectrum. Both wild type and araI mutant colonized barley roots well when applied separately, although the araI mutant showed more of a single cell colonization pattern and less microcolony formation than the wild type. In general, most bacteria were found to colonize the basal parts of roots especially in the root hairs and the branching sites of side roots. When the A. radicis N35 wild type and araI mutant were applied in a 1:1 mixed inoculum, the wild type clearly dominated in colonization over the AHL negative strain (Figure 2). This indicates that AHL production by A. radicis N35 is important for its competitive colonization ability on barley roots.

Figure 2.

Colonization of barley roots by fluorescence labeled A. radicis N35 wild type and araI mutant detected using CLSM lambda mode. Blue color represent barley roots, red color represent the YFP-labeled A. radicis N35 wild type and green color represents the GFP labeled A. radicis N35 araI::tet AHL mutant. (A) YFP-labeled A. radicis N35 forms biofilm in the main root part and root hair part. (B) GFP-labeled A. radicis N35 araI::tet. (C,D) Inoculation with GFP-labeled A. radicis N35 araI::tet mutant mixed 1:1 with YFP-labeled A. radicis N35 wild type.

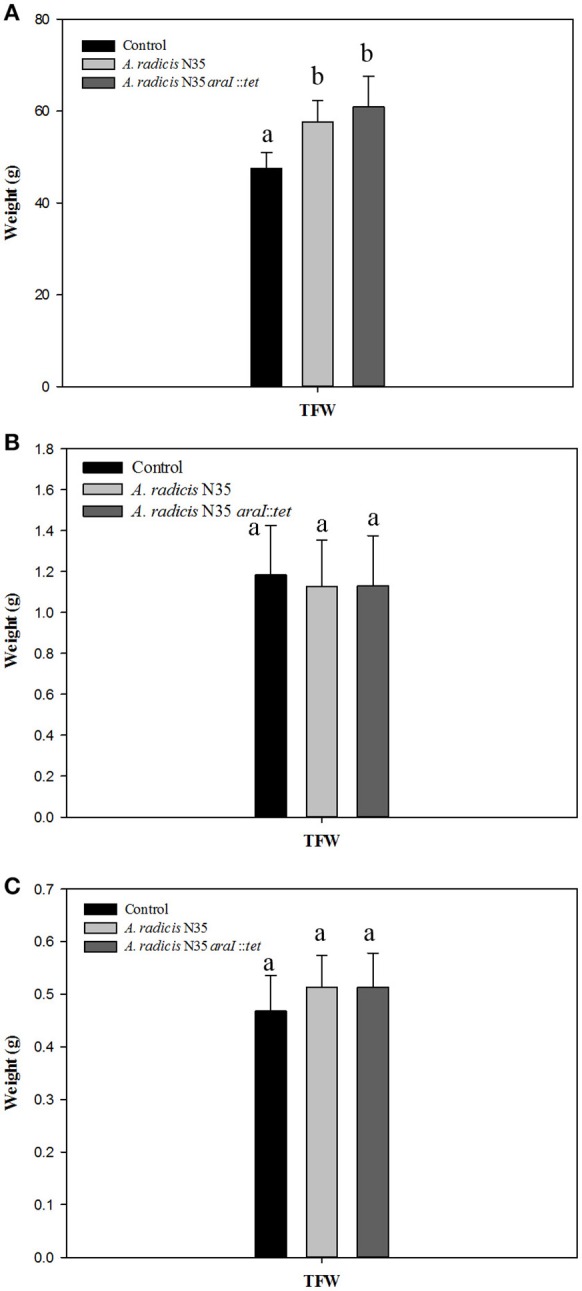

Plant growth promotion effect

To assess whether a growth promoting effect of A. radicis was possibly dependent on AHL production, seedlings were inoculated with N35 wild type and the araI mutant strains or not inoculated as control and grown under axenic conditions in the growth chamber or in non-sterile soil in the greenhouse. After 2 weeks or 2 months in the soil system and 2 weeks in the axenic system, barley plants were harvested and total fresh weight of the plants was measured (Figure 3). In the soil system, a significant growth promotion effect in response to inoculation with A. radicis N35 and the araI mutant on total plant fresh weight was found after 2 months (Figure 3A). In the axenic system no significant stimulation of growth was detectable after 2 weeks upon inoculation (Figure 3C). When the colonization of roots was analyzed using FISH, only a few cells of A. radicis N35 could be detected after 2 weeks, and it was not detectable anymore after 2 months in the soil system (not shown). In the axenic system, the colonization by A. radicis N35 was very well detectable with FISH (not shown) and GFP labeled cells during the whole growth period of 2 weeks (Figure 2 and Figure S2).

Figure 3.

(A,B) Total fresh weights (TFW) of barley seedlings grown in soil after inoculation with A. radicis N35 wild type or the araI mutant after 2 months and 2 weeks, respectively. (C) Total fresh weight of barley seedlings 2 weeks after inoculation with A. radicis N35 wild type or the araI mutant, respectively, under axenic growth condition. Different letters indicate significant differences among treatment groups (p < 0.05).

Barley transcriptome analysis

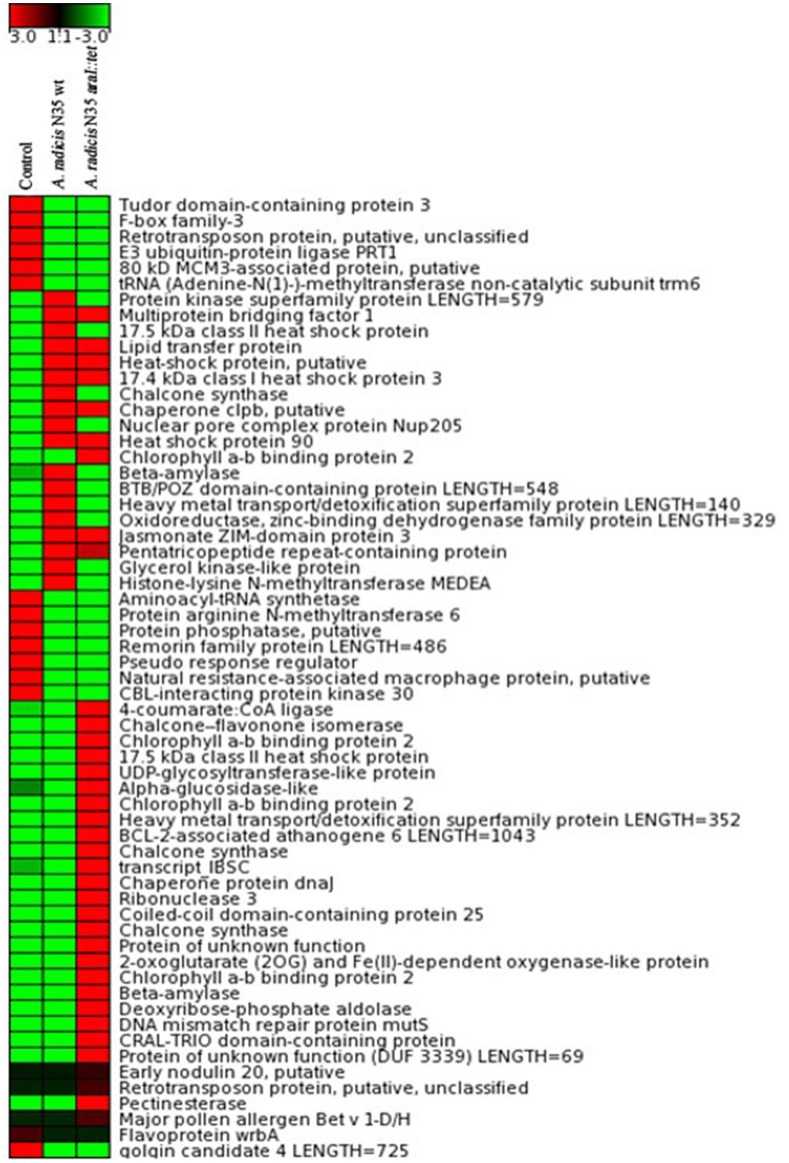

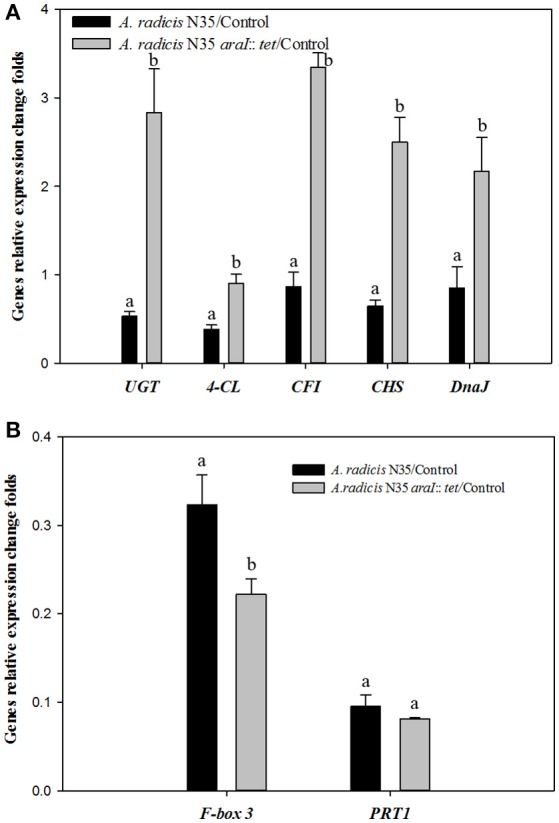

To investigate which plant genes were differentially regulated in barley leaves after inoculation in response to colonization by AHL producing and non-producing A. radicis N35 compared to the un-inoculated control plants, the plant transcriptome was analyzed via next generation sequencing alongside with a series of specific qPCR assays for verification of the sequencing results. In the barley leaf transcriptome sequencing analysis a number of gene transcripts were found to be significantly enhanced or suppressed by A. radicis N35 and/or the araI mutant at 10 days post inoculation (dpi) compared to the un-inoculated control plant (Figure 4). These plant transcripts can be classified into two groups: (1) AHL independent transcripts, correlated to the presence or absence of A. radicis N35, regardless if wild type or mutant were inoculated, and (2) AHL dependent transcripts, correlated to whether or not inoculated A. radicis N35 was able to produce AHL. Interestingly, transcript sequencing results from leaves after 10 dpi indicated that the transcription of several flavonoid synthesis genes (Besseau et al., 2007) was upregulated when plants were inoculated with the araI mutant (transcript group 2), including UDP-glycosyltransferase-like protein (UGT), CFI, chalcone synthase (CS), 4-coumarate-CoA ligase (4-CL) and chaperone protein (DnaJ). Thus, these five transcripts were selected for verifying the results by qPCR. Additionally, two genes of transcript group 1 were also selected, namely F-box family-3 gene (fb-3, 1) and the E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase PRT1 gene (PRT1), which were downregulated in response to inoculation with A. radicis N35 compared to the uninoculated control. Primers were designed for each of these seven genes (Table 2) and tested based on the standard and melting curve (Figure S4). The q-PCR assays (Figure 5) confirmed the transcriptomic sequencing data for the five group 2 transcripts related to the flavonoid pathway. The expression of these genes was between two- and four-fold higher with the A. radicis N35 araI mutant than with the AHL producing wild type. The downregulation of the two group 1 genes by both mutant and wild type could also be confirmed.

Figure 4.

Transcriptome analysis by RNA sequencing from 4 pooled leaves of barley plants grown in parallel. Total RNA was isolated from barley leaves 10 days after root inoculation with A. radicis N35 wild type and the araI mutant, respectively. Red (upregulated) and green (downregulated) colors represent an at least three-fold difference in the amount of detected gene transcripts for the respective gene between the analyzed samples. Black color means no change between the expression levels of the found transcripts.

Figure 5.

q-PCR analysis of the expression of genes under the influence of A. radicis N35 wild type and the araI mutant. Barley seedlings were not inoculated (control, CK) or inoculated with A. radicis N35 wild type or the araI mutant, respectively. Cultivation was performed monoxenically for 10 days (see MM). Then one leaf was taken at the three leaves stage, RNA was isolated, q-PCR from transcribed cDNA was performed. Statistical analysis was performed using one way ANOVA (p ≤ 0.05). Different letters indicate significant differences among treatment groups. (A) Flavonoid biosynthesis pathway genes: 4-coumarate CoA ligase (4-CL), chalcone-flavonone isomerase (CFI), chalcone synthase (CHS), UDP-glycosyltransferase-like protein (UGT); and chaperone protein (DnaJ). (B) Fb-3, F-Box family-3 and E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase (PRT1).

Content of saponarin and lutonarin in barley leaves

The HPLC-analysis revealed that in the leaves of the tested barley cultivar Barke the concentration of saponarin was generally higher than of lutonarin. In plants inoculated with the A. radicis N35 araI mutant, the contents of saponarin and lutonarin were ~two-fold compared to plants inoculated with the wild type or non-inoculated controls (Figure 6 and Figure S3). In addition the amount of lutonarin methylether in araI mutant inoculated plants reached almost twice the level detectable in wild type inoculated and non-inoculated control plants. These results corroborate the data from the gene transcriptome profiling by sequencing and q-PCR, which leads toward the conclusion that AHL signaling by barley root colonizing A. radicis N35 impacts flavonoid production in barley leaves.

Figure 6.

Accumulation of flavonoids in barley leaves measured by HPLC. The flavonoid components are (A) lutonarin, (B) saponarin, (C) lutonarin-4-methylester, (D) an unidentified flavonoid derivative. Different letters indicate significant differences among treatment groups (p < 0.05).

Discussion

Influence of AHLs on the root colonization of A. radicis N35

AHL production by A. radicis N35 has a positive effect on the colonization of roots, since an AHL defective mutant was less successful in root colonization (Figure 3). The QS-deficient araI mutant strain showed colonization mostly by single cells spread randomly over the root surface, while the N35 wild type cells grew more aggregated in microcolonies. This result corroborates the observation by Li (2010), who showed in a 1:1-mixture of GFP-labeled N35 wild type cells and the SYTO orange labeled araI mutant that only a few mutants colonized the roots, while wild type cells showed dense colonization. Even though the mutants were colonized together with the wild type in these experiments, the AHL deficient cells could obviously not profit from the produced AHL by the wild type in their vicinity. However, it has been shown previously (Hense et al., 2007), that quorum sensing on the rhizoplane must be considered as a strictly localized phenomenon, mainly taking place in microcolonies forming in small niches on the root surface confined by diffusion limitation. Here, the signaling substances can locally reach very high concentrations far above the average values which are measurable by taking e.g., liquid samples from the rhizosphere. Thus, although some mutant cells might profit from AHL producing neighboring wild type cells, the overall AHL concentration these mutants were exposed to, was probably below the threshold levels required for the autoinduction process. Consequently, QS regulated genes were not activated which might have led to the observed low competitive colonization phenotype.

In A. radicis N35, also phenotypic variants showed reduced root colonization. However, in contrast to araI mutants these variants had much reduced ability of plant growth promotion (Li et al., 2012). The reduced colonization of the araI mutant could be caused by a reduced tolerance toward reactive oxygen species (ROS) released by barley roots upon first contact with microbes as has been found in the case of the endophyte Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus during colonization of rice roots (Alquéres et al., 2013). In this case, ROS-quenching enzymes catalase and superoxide dismutase of the endophyte have a major role in the degradation of ROS released by the host plants during early host defense. In P. aeruginosa, QS was found to be involved in the stress tolerance, and luxI-type QS-deficient mutants (lasI, rhlI, and lasI rhlI) have defective expression of catalase (CAT) and superoxide dismutase activities (SOD). These mutants were more sensitive to oxidative stress than the parental strain (Hassett et al., 1999). Another study showed that the QS based stress tolerance can make it more difficult to quench quorum sensing activities and help to prevent social cheating (García-Contreras et al., 2015). In the co-inoculation experiment, the quorum sensing araI mutant may behave even as such a quorum sensing cheater, because it does not produce any AHL. The positive influence of QS on biofilm formation was shown in several studies. For instance, in the Pseudomonas fluorescence 2p24, the pcoI coded AHL synthase mutant resulted in seriously decreased biofilm formation, leading to less root colonization ability (Wei and Zhang, 2006). In P. aeruginosa, a quorum sensing lasI mutant formed flat undifferentiated biofilms which are more sensitive to the biocide sodium dodecyl sulfate than the wild type. These flat biofilm types of AHL defective mutants could be restored by exogenous addition of AHLs (Davies et al., 1998). Also in Sinorhizobium fredii SMH12, micro-colony biofilm formation was found regulated by QS and in Rhizobium spp., the biofilm formation is dependent on the production of AHLs (Davies et al., 1998; Rinaudi and Giordano, 2010; Pérez-Montaño et al., 2014). It could be shown, that exogenous addition of AHLs could promote the biofilm formation by Acidovorax sp. strain MR-S7 (Kusada et al., 2014). The importance of QS for the biofilm formation could be due to secretion of important compounds like extracellular DNA, the biosurfactant rhamnolipid and the secretion of the BapA-protein as shown in P. aeruginosa (Tolker-Nielsen, 2015). Furthermore, QS-compounds play an important role in P. fluorescence 2p24 for its colonization on wheat roots and development of biocontrol ability toward the take-all disease fungus (Wei and Zhang, 2006). In Burkholderia phytofirmans PsJN QS was also found to be important for its competitive biofilm formation and efficient colonization of roots and beneficial interaction with A. thaliana as plant host (Zúñiga et al., 2013). Thus, there is an increasing knowledge about the important role of AHLs in plant beneficial rhizosphere bacteria and endophytes in different plant systems and their involvement in different mechanisms of plant growth promotion. It could be even shown, that the exopolysaccharide production in S. fredii NGR234 was modified by AHL production (Krysciak et al., 2014).

Influence of AHL producing A. radicis on the biosynthesis and content of flavonoids in barley leaves

Compared with A. radicis N35 wild type bacteria, the colonization of roots by the AHL deficient araI mutant caused an accumulation of saponarin and lutonarin in barley leaves (Figure 6). This indicates that AHLs themselves or bacterial components induced by AHLs are involved in the regulation / induction of flavonoid biosynthesis in the host plant. A direct stimulatory effect of AHLs on the induction of flavonoid biosynthesis was first found in M. truncatula. In this case, 3-oxo-C12-HSL was shown to activate the transcription of chalcone synthase genes in white clover roots (Mathesius et al., 2003). In the A. radicis N35—barley interaction, a different AHL (3-OH-C10-HSL) is operating, which may have caused an inhibition of flavonoid biosynthesis. In A. thaliana, the influence of the length of the acyl chain and the substitution at the AHL C3 position were shown to cause different systemic responses (Schikora et al., 2011). The contrasting response of barley to 3-OH-C10 HSL may also be due to the fact that the monocotyledonous barley may respond differently to AHLs than the dicotyledonous white clover. On the other hand, since QS autoinducers are able to regulate bacterial surface exopolysaccharide production (Krysciak et al., 2014), the lack of AHLs in the A. radicis araI mutant could also have resulted in considerable changes in the surface exopolysaccharide structure and this may have caused a different plant response.

Flavonoids are known to help plants to acquire resistance toward various biotic and abiotic stresses (Treutter, 2005). For example, flavonoids were found in relation to drought stress in winter wheat (Ma et al., 2014) and could exhibit antifungal activities, e.g., in the carnation-Fusarium pathosystem (Curir et al., 2004). Furthermore, lutonarin and saponarin isolated from barley sprouts have been shown to be effective against bacterial pathogenesis enzymes (Park et al., 2014). Finally both lutonarin and saponarin are frequently discussed as antioxidative and antimicrobial agents in alternative medicine, as e.g., recently reviewed in Lahouar et al. (2015). The enhanced accumulation of the two flavone glycosides saponarin and lutonarin in barley leaves caused by the colonization of the roots by the A. radicis N35 araI mutant is an example for this kind of defense response. The expression of several flavonoid biosynthesis genes was upregulated due to inoculation with the A. radicis N35 araI mutant. This clearly indicated that the AHL deficient mutant strains activated a defense response. Three closely related R2R3-MYBs transcription factors (MYB11, MYB12, and MYB111) redundantly activate the transcription of early flavonoid biosynthesis genes (EBGs). The UDP-glycosyltransferases UGT91A1 and UGT84A1 together with CHS, CHI, and F3H, FLS1 are controlled by this R2R3MYB factors in Arabidopsis (Stracke et al., 2007). However, no data were obtained for the regulation at the transcriptional level. The flavonoid accumulation is not only regulated at the transcriptional, but also at the post-transcriptional level through PAL-degradation mediated by Kelch domain-containing F-box (KFB) proteins and degradation of E3 ubiquitin ligase (PRT1) complexes leading to the suppression of the phenylpropanoid pathway (Feder et al., 2015). In this study, it could be demonstrated by the transcriptomic sequencing results and confirmed by q-PCR, that the expression of F-box protein and E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase were downregulated (Figure 5). F-box family proteins are components of the SCF-protein complex, which is involved in the proteome degradation pathway. This process is for example important for plant development and immunity response to various stress condition (Thines et al., 2007). In addition, also an upregulation of dnaJ expression after inoculation with the araI mutant was shown mediated by transcription factor SG7 MYB (Figure 5). Its expression was found to correlate with flavonoid related genes and to be under the control of MYB transcription factors (Stracke et al., 2007). The upregulation of dnaJ expression also correlated with the upregulation of the flavonoid biosynthesis genes and flavonoid accumulation. DnaJ is also involved in salt stress resistance and known to interact with Hsp70 in the heat shock resistance process (Zhu et al., 1993). Since dnaJ expression was also found to be involved in regulation of saline tolerance, it is reasonable to test whether the higher expression of dnaJ will also result in increased salt stress tolerance by the plants.

Integrated role of AHLs by A. radicis in plant perception

Due to common evolutionary history, plants, and microbes have developed an elaborate system of mutual detection, cooperation, or deterrence. In the first recognition step, the most important function is the plants' innate immune system recognizing MAMPS and diverse microbial elicitors. On the microbial side the response to plant surface structures and exudates have a central role in recognition. The quorum sensing communication system of rhizobacteria based on AHL compounds may be considered as an integrated part in the perception of bacteria by plants. In the plant growth beneficial endophyte A. radicis N35, 3-OH-C10-HSL is the dominant AHL (Fekete et al., 2007). However, many Gram-negative plant pathogenic rhizobacteria also synthesize AHLs, although with different chain lengths and other functional groups. Since the onset of virulence is regulated by these auto-inducers, the plant is expected to learn about the presence of AHLs in their vicinity as soon as possible. In the case of pathogens, the network of multiple interactions concludes to initiate full expression of the defense cascade, while in the case of beneficial endophytes the response is dampened or completely suppressed allowing a cooperative interaction. There are several examples, that AHL compounds applied to rooting solutions of plants can exert diverse beneficial effects on plants, which include growth promotion as well as priming or induction of pathogen resistance in the host. This was shown in different plant species, such as M. truncatula, tomato, A. thaliana, and barley (Mathesius et al., 2003; Schuhegger et al., 2006; von Rad et al., 2008; Schenk et al., 2014). However, it is much less clear, what role AHLs of a beneficial root colonizing bacterium play in the concert of interaction with all its other compounds in the plant's recognition and perception system. In the current study, it could be shown, that the production of 3-OH-C10-HSL during the colonization process by the plant growth promoting, endophytic A. radicis N35 is able to efficiently influence the plant response and reduce the onset of a defense cascade. Whether this is caused by a direct interaction with AHLs or by an indirect effect through the induction of e.g., a different surface structure of the bacteria in the presence of AHLs, which is not recognized as a pathogenic signal, is not known yet. Nevertheless, the response of barley plants to A. radicis N35 wild type is characterized by the absence of expression of several genes involved in flavonoid biosynthesis in the plant leading to an attenuated defense response. Apparently, the 3-OH-C10-HSL-production is playing a major role in this process. Future detailed studies need to focus on the role of the quorum sensing compound 3-OH-C10-HSL on the regulation of expression of enzymes involved in the modification of the fine structure of the cell surface lipo- and exopolysaccharides or of type III secretion systems or other transport systems potentially involved in bacteria-host interactions.

Author contributions

SH and DL performed the experimental work and wrote the paper; ET and KM did bioinformatic data analysis; AV and WH did plant metabolite analysis and discussion; MS, AH, and MR conceived the research and wrote the paper.

Funding

This study was funded by the China Scholarship Council (CSC), file No. 2011911941 to SH.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2016.01868/full#supplementary-material

Construction of araI mutant in A. radicis N35.

Colonization of barley roots by A. radicis N35 GFP in a monoxenic system at different time points after inoculation (dpi as indicated in the pictures).

Upper part: HPLC-separation of compounds with absorbance at 280 nm (see MM). Lower part: UV-spectra of the different eluted compounds.

qPCR primer melting curves.

References

- Ahn I. P., Lee S. W., Suh S. C. (2007). Rhizobacteria-induced priming in Arabidopsis is dependent on ethylene, jasmonic acid, and NPR1. Mol. Plant. Microbe Interact. 20, 759–768. 10.1094/MPMI-20-7-0759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alquéres S., Meneses C., Rouws L., Rothballer M., Baldani I., Schmid M., et al. (2013). The bacterial superoxide dismutase and glutathione reductase are crucial for endophytic colonization of rice roots by Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus PAL5. Mol. Plant. Microbe Interact. 26, 937–945. 10.1094/MPMI-12-12-0286-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amann R., Springer N., Ludwig W., Görtz H. D., Schleifer K.-H. (1991). Identification in situ and phylogeny of uncultured bacterial endosymbionts. Nature 351, 161–164. 10.1038/351161a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berendsen R. L., Pieterse C. M. J., Bakker P. A. (2012). The rhizosphere microbiome and plant health. Trends Plant Sci. 17, 478–486. 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besseau S., Hoffmann L., Geoffroy P., Lapierre C., Pollet B., Legrand M. (2007). Flavonoid accumulation in Arabidopsis repressed in lignin synthesis affects auxin transport and plant growth. Plant Cell 19, 148–162. 10.1105/tpc.106.044495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury S. P., Uhl J., Grosch R., Alquéres S., Pittroff S., Dietel K., et al. (2015). Cyclic lipopeptides of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens subsp. plantarum colonizing the lettuce rhizosphere enhance plant defense responses toward the bottom rot pathogen Rhizoctonia solani. Mol. Plant. Microbe Interact. 28, 984–995. 10.1094/MPMI-03-15-0066-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes-Barco A. M., Goodwin P. H., Hsiang T. (2010). Comparison of induced resistance activated by benzothiadiazole, (2R,3R)-butanediol and an isoparaffin mixture against anthracnose of Nicotiana benthamiana. Plant Pathol. 59, 643–653. 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2010.02283.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Curir P., Dolci M., Galeotti F. (2004). A phytoalexin-like flavonoid involved in the carnation (Dianthus caryophyllus)-Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. dianthi pathosystem. J. Phytopathol. 153, 65–67. 10.1111/j.1439-0434.2004.00916.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cushnie T. P., Lamb A. J. (2011). Recent advances in understanding the antibacterial properties of flavonoids. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 38, 99–107. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies D. G., Parsek M. R., Pearson J. P., Iglewski B. H., Costerton J. W., Greenberg E. P. (1998). The involvement of cell-to-cell signals in the development of a bacterial biofilm. Science 280, 295–298. 10.1126/science.280.5361.295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vleesschauwer D., Djavaheri M., Bakker P. A., Hofte M. (2008). Pseudomonas fluorescens WCS374r-induced systemic resistance in rice against Magnaporthe oryzae is based on pseudobactin-mediated priming for a salicylic acid-repressible multifaceted defense response. Plant Physiol. 148, 1996–2012. 10.1104/pp.108.127878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vleesschauwer D., Höfte M. (2009). Rhizobacteria-induced systemic resistance, in Advances in Botanical Research, Vol. 51, ed Woolhouse H. W. (London, UK: Academic Press; ), 223–281. [Google Scholar]

- Dower W. J., Miller J. F., Ragsdale C. W. (1988). High efficiency transformation of E. coli by high voltage electroporation. Nucleic Acids Res. 16, 6127–6145. 10.1093/nar/16.13.6127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugar G., Herbig A., Förstner K. U., Heidrich N., Reinhardt R., Nieselt K., et al. (2013). High-resolution transcriptome maps reveal strain-specific regulatory features of multiple Campylobacter jejuni isolates. PLoS Genet. 9:e1003495. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberl L. (1999). N-acyl homoserinelactone-mediated gene regulation in gram-negative bacteria. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 22, 493–506. 10.1016/S0723-2020(99)80001-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feder A., Burger J., Gao S., Lewinsohn E., Katzir N., Schaffer A. A., et al. (2015). A kelch domain-containing F-box coding gene negatively regulates flavonoid accumulation in muskmelon. Plant Physiol. 169, 1714–1726. 10.1104/pp.15.01008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fekete A., Frommberger M., Rothballer M., Li X., Englmann M., Fekete J., et al. (2007). Identification of bacterial N -acylhomoserine lactones (AHLs) with a combination of ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC), ultra-high-resolution mass spectrometry, and in-situ biosensors. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 387, 455–467. 10.1007/s00216-006-0970-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuqua C., Greenberg E. P. (2002). Listening in on bacteria: acyl-homoserine lactone signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Bio. 3, 685–695. 10.1038/nrm907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gantner S., Schmid M., Duerr C., Schuhegger R., Steidle A., Hutzler P., et al. (2006). In situ quantitation of the spatial scale of calling distances and population density-independent N-acylhomoserine lactone-mediated communication by rhizobacteria colonized on plant roots. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 56, 188–194. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2005.00037.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Contreras R., Nuñez-López L., Jasso-Chavez R., Kwan B. W., Belmont J. A., Rangel-Vega A., et al. (2015). Quorum sensing enhancement of the stress response promotes resistance to quorum quenching and prevents social cheating. ISME J. 9, 115–125. 10.1038/ismej.2014.98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillaume H., Thonart P., Ongena M. (2012). PAMPs, MAMPs, DAMPs and others: an update on the diversity of plant immunity elicitors. Biotechnol. Agron. Soc. 16, 257–268. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan S., Mathesius U. (2012). The role of flavonoids in root-rhizosphere signalling: opportunities and challenges for improving plant-microbe interactions. J. Exp. Bot. 63, 3429–3444. 10.1093/jxb/err430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassett D. J., Ma J. F., Elkins J. G., McDermott T. R., Ochsner U. A., West S. E., et al. (1999). Quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa controls expression of catalase and superoxide dismutase genes and mediates biofilm susceptibility to hydrogen peroxide. Mol. Microbiol. 34, 1082–1093. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01672.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hense B. A., Kuttler C., Müller J., Rothballer M., Hartmann A., Kreft J. U. (2007). Does efficiency sensing unify diffusion and quorum sensing? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5, 230–239. 10.1038/nrmicro1600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoang T. T., Karkhoff-Schweizer R. R., Kutchma A. J., Schweizer H. P. (1998). A broad-host-range Flp-FRT recombination system for site-specific excision of chromosomally-located DNA sequences: application for isolation of unmarked Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants. Gene 212, 77–86. 10.1016/S0378-1119(98)00130-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann S., Otto C., Kurtz S., Sharma C. M., Khaitovich P., Vogel J., et al. (2009). Fast mapping of short sequences with mismatches, insertions and deletions using index structures. PLoS Comput. Biol. 5:e1000502. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiyama M., Shibamoto T. (2012). Flavonoids with potent antioxidant activity found in young green barley leaves. J. Agric. Food Chem. 60, 6260–6267. 10.1021/jf301700j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krol E., Becker A. (2014). Rhizobial homologs of the fatty acid transporter FadL facilitate perception of long-chain acyl-homoserine lactone signals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 10702–10707. 10.1073/pnas.1404929111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krysciak D., Grote J., Rodriguez Orbegoso M., Utpatel C., Förstner K. U., Li L., et al. (2014). RNA sequencing analysis of the broad-host-range strain Sinorhizobium fredii NGR234 identifies a large set of genes linked to quorum sensing-dependent regulation in the background of a traI and ngrI deletion mutant. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80, 5655–5671. 10.1128/AEM.01835-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusada H., Hanada S., Kamagata Y., Kimura N. (2014). The effects of N-acylhomoserine lactones, beta-lactam antibiotics and adenosine on biofilm formation in the multi-beta-lactam antibiotic-resistant bacterium Acidovorax sp. strain MR-S7. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 118, 14–19. 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2013.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahouar L., El-Bok S., Achour L. (2015). Therapeutic potential of young green barley leaves in prevention and treatment of chronic diseases: an overview. Am. J. Chin. Med. 43, 1311–1329. 10.1142/S0192415X15500743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D. (2010). Phenotypic Variation and Molecular Signaling in the Interaction of the Rhizosphere Bacteria Acidovorax sp. N35 and Rhizobium Radiobacter F4 with Roots. Ph.D. thesis, Faculty for Biology, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München. [Google Scholar]

- Li D., Rothballer M., Engel M., Hoser J., Schmidt T., Kuttler C., et al. (2012). Phenotypic variation in Acidovorax radicis N35 influences plant growth promotion. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 79, 751–762. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01259.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D., Rothballer M., Schmid M., Esperschütz J., Hartmann A. (2011). Acidovorax radicis sp. nov., a wheat-root-colonizing bacterium. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 61, 2589–2594. 10.1099/ijs.0.025296-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugtenberg B., Kamilova F. (2009). Plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 63, 541–556. 10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.162918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma D., Sun D., Wang G., Li Y., Guo T. (2014). Expression of flavonoid biosynthesis genes and accumulation flavonoid in wheat leaves in response to drought stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 80, 60–66. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2014.03.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manz W., Amann R., Ludwig W., Wagner M., Schleifer K.-H. (1992). Phylogenetic oligodeoxynucleotide probes for the major subclasses of proteobacteria: problems and solutions. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 25, 593–600. 10.1016/S0723-2020(11)80121-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mathesius U., Mulders S., Gao M. S., Teplitski M., Caetano-Anolles G., Rolfe B. G., et al. (2003). Extensive and specific responses of a eukaryote to bacterial quorum-sensing signals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 1444–1449. 10.1073/pnas.262672599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park M. J., Ra J. E., Seo K. H., Jang K. C., Han S. I., Lee J. H., et al. (2014). Identification and evaluation of flavone-glucosides isolated from barley sprouts and their inhibitory activity against bacterial neuraminidase. Nat. Prod. Commun. 9, 1469–1472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Montaño F., Jiménez-Guerrero I., Del Cerro P., Baena-Ropero I., López-Baena F. J., Ollero F. J., et al. (2014). The symbiotic biofilm of Sinorhizobium fredii SMH12, necessary for successful colonization and symbiosis of Glycine max cv Osumi, is regulated by Quorum Sensing systems and inducing flavonoids via NodD1. PLoS ONE 9:e105901. 10.1371/journal.pone.0105901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse C. M., van Wees S. C., Hoffland E., van Pelt J. A., van Loon L. C. (1996). Systemic resistance in Arabidopsis induced by biocontrol bacteria is independent of salicylic acid accumulation and pathogenesis-related gene expression. Plant Cell 8, 1225–1237. 10.1105/tpc.8.8.1225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinaudi L. V., Giordano W. (2010). An integrated view of biofilm formation in rhizobia. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 304, 1–11. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01840.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothballer M., Eckert B., Schmid M., Fekete A., Schloter M., Lehner A., et al. (2008). Endophytic root colonization of gramineous plants by Herbaspirillum frisingense. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 66, 85–95. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2008.00582.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothballer M., Picot M., Sieper T., Arends J. B., Schmid M., Hartmann A., et al. (2015). Monophyletic group of unclassified gamma-Proteobacteria dominates in mixed culture biofilm of high-performing oxygen reducing biocathode. Bioelectrochemistry 106, 167–176. 10.1016/j.bioelechem.2015.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenk S. T., Hernandez-Reyes C., Samans B., Stein E., Neumann C., Schikora M., et al. (2014). N-Acyl-homoserine lactone primes plants for cell wall reinforcement and induces resistance to bacterial pathogens via the salicylic acid/oxylipin pathway. Plant Cell 26, 2708–2723. 10.1105/tpc.114.126763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schikora A., Schenk S. T., Hartmann A. (2016). Beneficial effects of bacteria-plant communication based on quorum sensing molecules of the N-acyl homoserine lactone group. Plant Mol. Biol. 90, 605–612. 10.1007/s11103-016-0457-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schikora A., Schenk S. T., Stein E., Molitor A., Zuccaro A., Kogel K. H. (2011). N-acyl-homoserine lactone confers resistance toward biotrophic and hemibiotrophic pathogens via altered activation of AtMPK6. Plant Physiol. 157, 1407–1418. 10.1104/pp.111.180604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuhegger R., Ihring A., Gantner S., Bahnweg G., Knappe C., Vogg G., et al. (2006). Induction of systemic resistance in tomato by N-acylhomoserine lactone–producing rhizosphere bacteria. Plant Cell Environ. 29, 909–918. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01471.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stickler D. J., Morris N. S., McLean R. J., Fuqua C. (1998). Biofilms on indwelling urethral catheters produce quorum-sensing signal molecules in situ and in vitro. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64, 3486–3490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stracke R., Ishihara H., Huep G., Barsch A., Mehrtens F., Niehaus K., et al. (2007). Differential regulation of closely related R2R3-MYB transcription factors controls flavonol accumulation in different parts of the Arabidopsis thaliana seedling. Plant J. 50, 660–677. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03078.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thines B., Katsir L., Melotto M., Niu Y., Mandaokar A., Liu G., et al. (2007). JAZ repressor proteins are targets of the SCF(COI1) complex during jasmonate signalling. Nature 448, 661–665. 10.1038/nature05960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolker-Nielsen T. (2015). Biofilm development. Microbiol. Spectr. 3:MB-0001–2014. 10.1128/microbiolspec.mb-0001-2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treutter D. (2005). Significance of flavonoids in plant resistance and enhancement of their biosynthesis. Plant Biol. 7, 581–591. 10.1055/s-2005-873009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Rad U., Klein I., Dobrev P. I., Kottova J., Zazimalova E., Fekete A., et al. (2008). Response of Arabidopsis thaliana to N-hexanoyl-DL-homoserinelactone, a bacterial quorum sensing molecule produced in the rhizosphere. Planta 229, 73–85. 10.1007/s00425-008-0811-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters C. M., Bassler B. L. (2005). Quorum sensing: cell-to-cell communication in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 21, 319–346. 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.012704.131001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei H. L., Zhang L. Q. (2006). Quorum-sensing system influences root colonization and biological control ability in Pseudomonas fluorescens 2P24. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 89, 267–280. 10.1007/s10482-005-9028-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin R., Messner B., Faus-Kessler T., Hoffmann T., Schwab W., Hajirezaei M. R., et al. (2012). Feedback inhibition of the general phenylpropanoid and flavonol biosynthetic pathways upon a compromised flavonol-3-O-glycosylation. J. Exp. Bot. 63, 2465–2478. 10.1093/jxb/err416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J. K., Shi J., Bressan R. A., Hasegawa P. M. (1993). Expression of an Atriplex nummularia gene encoding a protein homologous to the bacterial molecular chaperone DnaJ. Plant Cell 5, 341–349. 10.1105/tpc.5.3.341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zúñiga A., Poupin M. J., Donoso R., Ledger T., Guiliani N., Gutiérrez R. A., et al. (2013). Quorum sensing and indole-3-acetic acid degradation play a role in colonization and plant growth promotion of Arabidopsis thaliana by Burkholderia phytofirmans PsJN. Mol. Plant. Microbe Interact. 26, 546–553. 10.1094/MPMI-10-12-0241-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Construction of araI mutant in A. radicis N35.

Colonization of barley roots by A. radicis N35 GFP in a monoxenic system at different time points after inoculation (dpi as indicated in the pictures).

Upper part: HPLC-separation of compounds with absorbance at 280 nm (see MM). Lower part: UV-spectra of the different eluted compounds.

qPCR primer melting curves.