Abstract

The polyomavirus JC (JCV) infects 85% of healthy individuals, and its reactivation in a limited number of immunosuppressed people causes progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), a severe demyelinating disease of the central nervous system. We hypothesized that JCV-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) might control JCV replication in healthy individuals, blocking the evolution of PML. Using 51Cr release and tetramer staining assays, we show that 8 of 11 HLA-A*0201+ healthy subjects (73%) harbor detectable JCV-specific CD8+ CTLs that recognize one or two epitopes of JCV VP1 protein, the HLA-A*0201-restricted VP1p36 and VP1p100 epitopes. We determined that the frequency of JCV VP1 epitope-specific CTLs varied from less than 1/100,000 to 1/2,494 peripheral blood mononuclear cells. More individuals had JCV VP1-specific than cytomegalovirus-specific CTLs (8 of 11 subjects [73%] versus 2 of 10 subjects [20%], respectively). These results show that a CD8+-T-cell response against JCV is commonly found in immunocompetent people and suggest that these cells might protect against the development of PML.

The polyomavirus JC is the etiologic agent of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), a demyelinating disease of the central nervous system that occurs in immunosuppressed individuals (1). In previous studies, we demonstrated that JC virus (JCV)-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) activity could be detected in JCV antigen-stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) of PML survivors but not in patients who had a rapid evolution and died from PML (6, 14). We then characterized two HLA-A*0201-restricted CTL epitopes, JCV VP1p100 (13) and JCV VP1p36 (7). Finally, we showed that the emergence of JCV-specific CTLs early in the course of PML is predictive of an inactive form of the disease (8).

Although the demonstration of JCV-specific CTLs in immunosuppressed individuals recovering from PML suggests a role for this immune cell population in controlling PML in these subjects, whether these cells play a role in the prevention of PML in healthy people remains unclear. JCV infects more than 85% of the healthy adult population. Anti-JCV IgG, but not IgM, have been detected in PML patients (24), and JCV-specific CD4+ T cells have been found in healthy individuals (10). These findings suggest that PML is caused by viral reactivation in immunosuppressed individuals rather than by a primary infection. Therefore, it might be hypothesized that JCV-specific CTLs are present in healthy subjects. However, in previous studies, we were unable to demonstrate the presence of such CTLs in a limited group of individuals (13, 14). In this study we revisited this question with a larger group of healthy subjects by testing for the presence of CTLs specific for the newly characterized epitope, JCV VP1p36 (7). We found that three quarters of healthy individuals had detectable JCV-specific CTLs.

To determine whether healthy individuals are able to mount a cellular immune response against JCV, we enrolled 11 HLA-A*0201+ healthy subjects aged from 21.7 to 41.7 years (mean ± standard deviation, 31.6 ± 6.8 years) and obtained their informed consent according to institutional guidelines. The presence of anti-JCV IgG was determined for all subjects by hemagglutination inhibition assay, as described elsewhere (16). PBMC of the study subjects were tested for the presence of CTLs specific for either one of the following nonamer peptide HLA-A*0201-restricted CTL epitopes: JCV VP1p100 (13) and VP1p36 (7). Briefly, after isolation by the Ficoll diatrizoate gradient procedure, PBMC were put in culture in RPMI 1640-12% fetal calf serum in the presence of the virus epitope-specific peptide at a concentration of 1 to 2.5 μg/ml and, after 3 days, 25 U of recombinant human interleukin 2 (rIL-2)/ml. PBMC were cultured in vitro for a total of 10 to 14 days. Then the presence of CTLs specific for these epitopes was determined by 51Cr release and tetramer staining assays as previously described (7, 13). These assays were considered positive when the specific lysis was ≥10% or when the number of tetramer-positive CD8αβ+ T cells was ≥0.1% (7, 13, 22).

All the study subjects had anti-JCV antibodies in their serum, with titers ranging from 1/16 to 1/32 (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Detection of JCV- and CMV-specific CTL in 11 healthy subjects

| Subject | Anti-JCV IgG titer | % of CTL detected by indicated method that were specific fora:

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JCV VP1p36

|

JCV VP1p100

|

CMV pp65p495

|

||||||||

| FBTS | CCTS | 51Cr RA | FBTS | CCTS | 51Cr RA | FBTS | CCTS | 51Cr RA | ||

| 1 | 1/16 | — | 0.6 | — | — | 0.3 | — | — | — | — |

| 2 | 1/32 | — | 1.0 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 3 | 1/32 | — | 1.0 | — | — | 0.1 | — | — | — | — |

| 4 | 1/32 | — | 4.2 | — | — | 0.2 | — | — | — | — |

| 5 | 1/32 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 6 | 1/32 | 0.2 | 13.9 | 30 | — | 10 | 19 | 0.2 | 73 | 72 |

| 7 | 1/32 | — | 2.4 | — | — | 1.2 | 22 | — | — | — |

| 8 | 1/32 | — | 0.3 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 9 | 1/32 | 0.3 | 17.7 | 32 | — | 6.5 | 15 | — | — | — |

| 10 | 1/32 | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1.8 | 70.1 | 68 |

| 11 | 1/16 | NA | — | — | NA | — | — | NA | NA | NA |

Results of tetramer staining assays are expressed as percentages of CD8αβ+ T cells. Results of the 51Cr release assay are expressed as percentages of specific lysis of target cells by effector cells at an effector cell-to-target cell ratio of 20:1 Anti-CMV IgG was detected only in patients 6, 10, and 11. CCTS, cultured cell tetramer staining; 51Cr RA, 51Cr release assay performed with in vitro-stimulated PBMC; —, negative result; NA, not available.

JCV VP1p36-specific CTLs were detected in the PBMC of 8 of 11 subjects (73%), and JCV VP1p100-specific CTLs were detected in the PBMC of 6 of 11 subjects (55%). As shown in Table 1, tetramer staining of epitope peptide-stimulated PBMC was more sensitive than a 51Cr release assay in detecting JCV-specific CTLs.

To assess the cellular immune response against another DNA virus which infects a majority of the adult population, we tested the PBMC of our subjects for the presence of CTLs specific for the frequently recognized cytomegalovirus (CMV) HLA-A*0201-restricted immunodominant epitope NLVPMVATV, an epitope which is present at amino acid positions 495 to 503 of the lower-matrix 65-kDa phosphoprotein (CMV pp65p495) (4, 5). The serological analysis for CMV was performed by a clinical laboratory of our institution. We found that 3 of 11 subjects (27%) had anti-CMV IgG (subjects 6, 10, and 11). Two of these 3 subjects (subjects 6 and 10) also had CMV pp65p495-specific CTLs out of the 10 subjects tested (20%). The third subject (subject 11), who was positive for anti-CMV IgG, was not tested for the presence of CMV-specific CTLs.

To determine the frequency of virus epitope-specific CTLs in the PBMC of these healthy individuals prior to any in vitro stimulation, we used the fresh blood tetramer staining (FBTS) assay and the CTL sorting (CTLS) technique, as previously described (7) (Table 2). With FBTS, the number of tetramer-positive cells was directly calculated and expressed as a number of virus epitope-specific CD8+ CTLs per PBMC in fresh blood. For the CTLS technique, 50 million PBMC were isolated from fresh blood, stained with a given phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated tetramer, incubated with anti-PE microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) and sorted with an AUTOMACS cell sorter (Miltenyi Biotec) into a tetramer-positive and a tetramer-negative fractions. This technique allowed us to detect very rare virus epitope-specific CTLs and calculate their frequency among unstimulated PBMC.

TABLE 2.

Determination of the frequency of virus epitope-specific CTL in fresh blood

| Subject | Number of CTL detected by indicated method that were specific fora:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JCV VP1p36

|

JCV VP1p100

|

CMV pp65p495

|

||||

| FBTS | CTLS | FBTS | CTLS | FBTS | CTLS | |

| 2 | — | 1/100,000 | — | — | — | NA |

| 4 | — | <1/100,000 | — | — | — | NA |

| 6 | 1/4,785 | NA | — | NA | 1/9,100 | NA |

| 9 | 1/2,494 | 1/22,883 | — | 1/75,200 | — | NA |

| 10 | — | NA | — | NA | 1/6,000 | NA |

Results of FBTS and CTLS are expressed as numbers of tetramer-positive cells/total numbers of PBMC. —, negative result; NA, not available.

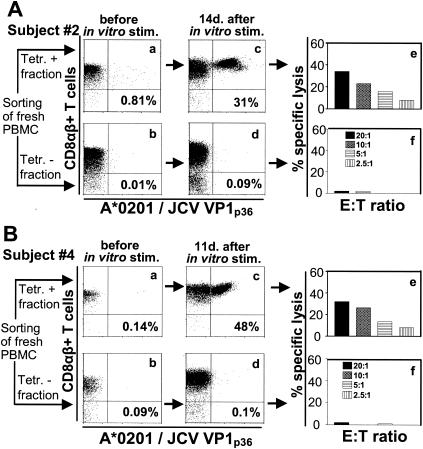

JCV VP1p36-specific CTLs were detected by FBTS in the PBMC of 2 of 10 individuals. Based on this method, the frequency of these CTLs was 1/4,785 PBMC for one subject (subject 6) and 1/2,494 PBMC for the other subject (subject 9). We also determined the frequency of VP1p36-specific CTLs by CTLS in subject 9 and found a frequency of 1/22,883 PBMC, 1 log lower than the frequency determined by FBTS. The CTLS method was used to evaluate the PBMC of two additional subjects (subjects 2 and 4) who had no detectable JCV VP1p36-specific CTLs as determined by FBTS. A nonhomogenous quantity (Fig. 1A, panel a) and a minute quantity (Fig. 1B, panel a) of tetramer binding cells were detected in the positive fraction, compared to a negligible quantity detected in the negative fraction (Fig. 1A and B, panel b). These sorted cells were then stimulated with the VP1p36 peptide in the presence of irradiated autologous feeder cells, and rIL-2 (50 U/ml) was added after 72 h. An expansion of VP1p36 tetramer binding cells were readily detected after 11 to 14 days of stimulation in culture in the positive (Fig. 1A and B, panel c), but not in the negative (Fig. 1A and B, panel d), sorted cell populations of both healthy individuals. The presence of functionally active effector cells in the positive (Fig. 1A and B, panel e) but not the negative (Fig. 1A and B, panel f) sorted cell populations was furthermore demonstrated in a 51Cr release cell killing assay. The frequency of VP1p36-specific CTLs could not be estimated with precision since the number of tetramer binding cells before in vitro stimulation was very low, being equal to or less than 1/100,000 PBMC. These results indicated that these cells were very rare in fresh blood from these two healthy individuals and that CTLS is a more sensitive technique than FBTS.

FIG. 1.

Low frequencies of JCV VP1p36-specific CTLs in two healthy individuals. Fifty million fresh PBMC of healthy subjects 2 and 4 were stained with the HLA-A*0201/JCV VP1p36 PE-labeled tetramer and sorted with an AUTOMACS cell sorter with PE-labeled immunomagnetic beads. A positive (A and B, panel a) and a negative (A and B, panel b) fraction were collected and analyzed immediately after the cells were sorted by flow cytometry. Sorted cells were stimulated in vitro in the presence of VP1p36 and feeder cells and stained with the VP1p36 tetramer after 14 days (A, panels c and d) or 11 days (B, panels c and d). The percentage of all CD8+ T cells that bind the tetramer is indicated in each panel. These cells were then assessed for the presence of functionally active effector cells in a 51Cr release assay (A and B, panels e and f). Tetr, tetramer; stim., stimulation; E:T ratio, effector cell/target cell ratio.

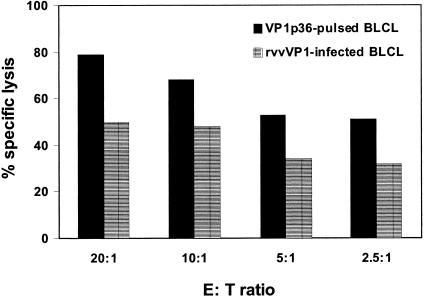

To rule out the possibility that VP1p36-specific lymphocytes were being expanded de novo from the PBMC of healthy individuals by in vitro stimulation with the peptide VP1p36, we sought to determine if similar results would be seen with another well-characterized HLA-A*0201-restricted CTL epitope peptide to stimulate the expansion of CTLs. We stimulated the PBMC of human immunodeficiency virus-negative (HIV−) subject 2 with the HIV Gagp77 peptide and evaluated the lymphocytes with the corresponding tetramer (18, 23). No tetramer binding cells were detected in the positive or negative lymphocyte fraction before or 2 weeks after in vitro stimulation with the HIV Gagp77 peptide (data not shown). Then, to rule out the possibility that HLA-A*0201/JCV VP1p36 tetramer staining of the PBMC of healthy individuals was simply the result of a particularly high affinity of the VP1p36 peptide for the HLA-A*0201 molecule, we compared the binding affinities of JCV VP1p36, VP1p100, and HIV Gagp77 to the T2 cell line, which expresses only the HLA-A*0201 molecule (21). This study demonstrated that the binding affinities of these three peptides to the HLA-A*0201 molecule were similar (data not shown). All together, these results suggest that de novo expansion of VP1p36-specific CTLs in the PBMC of healthy individuals in vitro was highly unlikely. Finally, to examine whether JCV VP1 epitope-specific CTLs were able to recognize an epitope processed by cells expressing the entire VP1 protein, the PBMC of subject 4 were stimulated with VP1p36 in the presence of rIL-2 as described above. After 2 weeks, JCV VP1p36+ cells were sorted with the corresponding tetramer. These tetramer-positive cells were put back into culture in the presence of rIL-2 for an additional 2-week period and were used as effector cells in a 51Cr release assay. Target cells were the autologous B-lymphoblastoid cell line (BLCL), which were either pulsed with VP1p36 at a concentration of 1 μg/ml or infected with a recombinant vaccinia virus expressing the entire VP1 protein, as previously described (14). Both peptide-pulsed and recombinant vaccinia virus VP1-infected target cells were lysed by effector cells. This experiment demonstrates that JCV VP1p36-specific CTLs from a healthy subject were able to recognize the corresponding epitope after it had been processed from the full-length VP1 protein by virus-infected cells (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

The JCV VP1p36 epitope is processed by autologous BLCL infected by a recombinant vaccinia virus expressing the whole VP1 protein of JCV. Enriched JCV VP1p36-specific CTLs from the PBMC of subject 4 were assessed for their ability to destroy autologous BLCL, which were either pulsed with JCV VP1p36 or infected with a recombinant vaccinia virus expressing the entire VP1 protein. An important specific lysis of target cells (T) by effector cells (E) was observed under both conditions, although this lysis was slightly more pronounced in the case of peptide-pulsed target cells. rvvVP1, recombinant vaccinia virus expressing the whole VP1 protein.

JCV VP1p100-specific CTLs were found in the PBMC of none of 10 individuals by FBTS. We then used the CTLS technique on the PBMC of subjects 2, 4, and 9. We were able to detect JCV VP1p100-specific CTLs in the cells from subject 9 at a frequency of 1/75,200 PBMC.

CMV pp65p495-specific CTLs were detected by FBTS in the PBMC of subjects 6 and 10. The frequency of tetramer-positive cells represented 0.2 and 1.8% of CD8αβ+ T cells or 1/9,100 and 1/6,000 PBMC, respectively. This result is similar to that reported in previous studies (2, 25). Therefore, we did not perform CTLS in these cases.

The underlying hypothesis of this study was that JCV-specific CTLs are present in the PBMC of healthy, immunocompetent subjects. Our results show that a majority of the JCV-infected healthy individuals studied (73%) had detectable JCV-specific CTLs in their blood. Studies of the cellular immune responses against CMV and Epstein-Barr virus, two other viruses that establish lifelong latent infections and cause severe disorders only in a minority of immunosuppressed individuals, have also shown a very good concordance rate between the results of serology and the detection of virus-specific CD8+ T cells. All subjects who were seropositive for CMV had detectable CMV-specific CD8+ T cells (9, 11, 25). Epstein-Barr virus-specific CD8+ T cells were also present in all seropositive healthy individuals at least 10 years after their seroconversion (3, 22).

Interestingly, more subjects had CTLs directed against JCV VP1p36 than against JCV VP1p100, and no subject had CTLs recognizing the latter epitope only. In addition, for those subjects who had a CTL response against both epitopes, JCV VP1p36 was always recognized by a greater number of CD8+ T cells than JCV VP1p100. These findings show that JCV VP1p36 is a more immunodominant epitope than JCV VP1p100 and might explain why we were unable to detect JCV VP1p100-specific CTLs in a limited number of healthy individuals in a previous study (13). This was confirmed by the determination of the frequency of JCV-specific CTLs prior to in vitro stimulation: JCV VP1p36-specific CTLs were found more often and in higher numbers in PBMC than JCV VP1p100-specific CTLs. The range of frequencies of VP1 peptide-specific CTLs in PBMC was relatively broad, from less than 1/100,000 to 1/2,494 PBMC. These values are similar to those reported for HIV+ patients with PML who had a favorable clinical outcome (7). Our results also indicate that CTLS is a more sensitive technique than FBTS to determine the frequency of JCV-specific CTLs. This conclusion is clearly illustrated by the facts that JCV VP1p36-specific CTLs could be detected in the PBMC of two subjects (subjects 2 and 4) and JCV VP1p100-specific CTLs could be detected in the PBMC of one subject (9) but that FBTS was negative in studies of all three subjects. However, when JCV-specific cells were frequent enough to be detected by FBTS (JCV VP1p36-specific CTLs in subject 9), the result was one log higher than with CTLS, reflecting the fact that CTLS underestimates the frequency of epitope-specific CTLs. Finally, the fact that JCV VP1p36-specific CTLs were able to recognize and destroy cells expressing the entire VP1 protein indicates that this epitope is indeed processed and presented on major histocompatibility complex class I molecules by naturally infected cells. These data suggest that recognition of this epitope by CTLs might play a significant role in the containment of JCV in healthy individuals.

When we compared the frequencies of JCV-specific CTLs with those of CTLs specific to a well-known immunodominant epitope of CMV, we found that a greater number of individuals in our study harbored CTLs recognizing JCV VP1 epitopes than CMV pp65p495. This difference in the cellular immune responses against the two viruses correlates well with the results of the humoral immune response. Indeed, while all our study subjects had detectable anti-JCV IgG, only three of them had anti-CMV IgG. This phenomenon likely reflects a higher rate of infection by JCV than by CMV in our cohort. A possible explanation for this difference might be the young age of our subjects. More than 85% of adults in the beginning of their third decade are already infected by JCV, whereas the rate of infection by CMV is approximately 50% in the general population (9) and increases with age (12).

Do these JCV-specific CD8+ T cells play a role in preventing the development of PML in healthy individuals? In mice infected with CMV, the immune system contributes to preventing the onset of CMV-associated disease, and CD8+ T cells have been shown to be more critical than CD4+ and NK cells in this viral containment (19). The fact that CMV is a very slowly replicating virus provides time for the CMV-specific CD8+ T cells to recognize and lyse infected target cells before the formation of infectious virus (19). Interestingly, JCV is also a slow-growing virus (17). It is possible that virus-specific CD8+ T cells, even in low numbers, are able to prevent the spread of JCV. This viral control is quite effective in most immunosuppressed individuals, as reflected by the fact that only 0.07% of HIV− patients with hematologic malignancies, 0.8% of liver transplant recipients, and 5.1% of AIDS patients develop PML (15, 20).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants R01 NS/AI 041198 and NS 047029 and by grant P30-AI28691 from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute-Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center-Children's Hospital Center for AIDS Research to I.J.K. R.A.D.P. is the recipient of a fellowship for advanced research from the Swiss National Science Foundation and a grant from the Eugenio Litta Foundation.

We are grateful to Michelle Lifton and Darci Gorgone for running the flow cytometry samples and to Freddie Peyerl for performing the peptide binding affinity assay.

REFERENCES

- 1.Antinori, A., A. Cingolani, P. Lorenzini, M. L. Giancola, I. Uccella, S. Bossolasco, S. Grisetti, F. Moretti, B. Vigo, M. Bongiovanni, B. Del Grosso, M. I. Arcidiacono, G. C. Fibbia, M. Mena, M. G. Finazzi, G. Guaraldi, A. Ammassari, A. d'Arminio Monforte, P. Cinque, A. De Luca, and the Italian Registry Investigative Neuro AIDS Study Group. 2003. Clinical epidemiology and survival of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: data from the Italian Registry Investigative Neuro AIDS (IRINA). J. Neurovirol. 9(Suppl. 1):47-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boppana, S. B., and W. J. Britt. 1996. Recognition of human cytomegalovirus gene products by HCMV-specific cytotoxic T cells. Virology 222:293-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Catalina, M. D., J. L. Sullivan, K. R. Bak, and K. Luzuriaga. 2001. Differential evolution and stability of epitope-specific CD8(+) T cell responses in EBV infection. J. Immunol. 167:4450-4457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen, F. E., G. Aubert, P. Travers, I. A. Dodi, and J. A. Madrigal. 2002. HLA tetramers and anti-CMV immune responses: from epitope to immunotherapy. Cytotherapy 4:41-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diamond, D. J., J. York, J. Y. Sun, C. L. Wright, and S. J. Forman. 1997. Development of a candidate HLA A*0201 restricted peptide-based vaccine against human cytomegalovirus infection. Blood 90:1751-1767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Du Pasquier, R. A., K. W. Clark, P. S. Smith, J. T. Joseph, J. M. Mazullo, U. De Girolami, N. L. Letvin, and I. J. Koralnik. 2001. Favorable clinical outcome in HIV-infected individuals with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy correlates with JCV-specific cellular immune response. J. Neurovirol. 7:318-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Du Pasquier, R. A., M. J. Kuroda, J. Schmitz, Y. Zheng, K. Martin, F. Peyrl, M. Lifton, D. Gorgone, P. Autissier, N. L. Letvin, and I. J. Koralnik. 2003. Low frequency of cytotoxic T lymphocytes against the novel HLA-A*0201-restricted JC virus epitope VP1p36 in patients with proven or possible progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. J. Virol. 77:11918-11926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Du Pasquier, R. A., M. J. Kuroda, Y. Zheng, J. Jean-Jacques, N. L. Letvin, and I. J. Koralnik. 2004. A prospective study demonstrates an association between JC virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes and the early control of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Brain 127:1970-1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gamadia, L. E., R. J. Rentenaar, P. A. Baars, E. B. Remmerswaal, S. Surachno, J. F. Weel, M. Toebes, T. N. Schumacher, I. J. ten Berge, and R. A. van Lier. 2001. Differentiation of cytomegalovirus-specific CD8(+) T cells in healthy and immunosuppressed virus carriers. Blood 98:754-761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gasnault, J., M. Kahraman, M. G. de Goer de Herve, D. Durali, J. F. Delfraissy, and Y. Taoufik. 2003. Critical role of JC virus-specific CD4 T-cell responses in preventing progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. AIDS 17:1443-1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gillespie, G. M., M. R. Wills, V. Appay, C. O'Callaghan, M. Murphy, N. Smith, P. Sissons, S. Rowland-Jones, J. I. Bell, and P. A. Moss. 2000. Functional heterogeneity and high frequencies of cytomegalovirus-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes in healthy seropositive donors. J. Virol. 74:8140-8150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klemola, E., and L. Kaariainen. 1965. Cytomegalovirus as a possible cause of a disease resembling infectious mononucleosis. Br. Med. J. 5470:1099-1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koralnik, I. J., R. A. Du Pasquier, M. Kuroda, J. E. Schmitz, X. Dang, Y. Zheng, M. Lifton, and N. L. Letvin. 2002. Association of prolonged survival in HLA-A2+ progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy patients with a cytotoxic T lymphocyte response specific for a dominant JC virus epitope. J. Immunol. 168:499-504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koralnik, I. J., R. A. Du Pasquier, and N. L. Letvin. 2001. JC virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in individuals with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. J. Virol. 75:3483-3487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martinez, A. J., and M. Ahdab-Barmada. 1993. The neuropathology of liver transplantation: comparison of main complications in children and adults. Mod. Pathol. 6:25-32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller, N. R., E. O. Major, and W. C. Wallen. 1983. Transfection of human fetal glial cells with molecularly cloned JCV DNA, p. 29-40. In J. L. Sever and D. L. Madden (ed.), Polyomaviruses and human neurological diseases. Alan R. Liss, Inc., New York, N.Y. [PubMed]

- 17.Padgett, B. L., D. L. Walker, G. M. ZuRhein, R. J. Eckroade, and B. H. Dessel. 1971. Cultivation of papova-like virus from human brain with progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy. Lancet i:1257-1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parker, K. C., M. A. Bednarek, L. K. Hull, U. Utz, B. Cunningham, H. J. Zweerink, W. E. Biddison, and J. E. Coligan. 1992. Sequence motifs important for peptide binding to the human MHC class I molecule, HLA-A2. J. Immunol. 149:3580-3587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Polic, B., H. Hengel, A. Krmpotic, J. Trgovcich, I. Pavic, P. Luccaronin, S. Jonjic, and U. H. Koszinowski. 1998. Hierarchical and redundant lymphocyte subset control precludes cytomegalovirus replication during latent infection. J. Exp Med. 188:1047-1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Power, C., J. G. Gladden, W. Halliday, M. R. Del Bigio, A. Nath, W. Ni, E. O. Major, J. Blanchard, and M. Mowat. 2000. AIDS- and non-AIDS-related PML association with distinct p53 polymorphism. Neurology 54:743-746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salter, R. D., D. N. Howell, and P. Cresswell. 1985. Genes regulating HLA class I antigen expression in T-B lymphoblast hybrids. Immunogenetics 21:235-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tan, L. C., N. Gudgeon, N. E. Annels, P. Hansasuta, C. A. O'Callaghan, S. Rowland-Jones, A. J. McMichael, A. B. Rickinson, and M. F. Callan. 1999. A re-evaluation of the frequency of CD8+ T cells specific for EBV in healthy virus carriers. J. Immunol. 162:1827-1835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsomides, T. J., A. Aldovini, R. P. Johnson, B. D. Walker, R. A. Young, and H. N. Eisen. 1994. Naturally processed viral peptides recognized by cytotoxic T lymphocytes on cells chronically infected by human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Exp Med. 180:1283-1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weber, T., C. Trebst, S. Frye, P. Cinque, L. Vago, C. J. Sindic, W. J. Schulz-Schaeffer, H. A. Kretzschmar, W. Enzensberger, G. Hunsmann, and W. Luke. 1997. Analysis of the systemic and intrathecal humoral immune response in progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. J. Infect. Dis. 176:250-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wills, M. R., A. J. Carmichael, K. Mynard, X. Jin, M. P. Weekes, B. Plachter, and J. G. Sissons. 1996. The human cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) response to cytomegalovirus is dominated by structural protein pp65: frequency, specificity, and T-cell receptor usage of pp65-specific CTLs. J. Virol. 70:7569-7579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]