Abstract

exon0 (orf141) of Autographa californica multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus (AcMNPV) is a highly conserved baculovirus gene that codes for a predicted 261-amino-acid protein. Located in the C-terminal region of EXON0 are a predicted leucine-rich coiled-coil domain and a RING finger motif. The 5′ 114 nucleotides of exon0 form part of ie0, which is a spliced gene expressed at very early times postinfection, but transcriptional analysis revealed that exon0 is transcribed as a late gene. To determine the role of exon0 in the baculovirus life cycle, we used AcMNPV bacmids and generated exon0 knockout viruses (Ac-exon0-KO) by recombination in Escherichia coli. Ac-exon0-KO progressed through the very late phases in Sf9 cells, as evidenced by the development of occlusion bodies in the nuclei of the transfected or infected cells. However, production of budded virus (BV) in Ac-exon0-KO-infected cells was reduced at least 3 orders of magnitude in comparison to that in wild-type virus infection. Microscopy revealed that Ac-exon0-KO was restricted primarily to the cells initially infected, exhibiting a single-cell infection phenotype. Slot blot assays and Western blot analysis indicated that exon0 deletion did not affect the onset or levels of viral DNA replication or the expression of IE1, IE0, and GP64 prior to BV release. These results demonstrate that exon0 is required for efficient production of BV in the AcMNPV life cycle but does not affect late occlusion-derived virus.

Autographa californica multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus(AcMNPV) is a member of the Baculoviridae, which are large, enveloped, double-stranded DNA viruses and pathogens of insects. During the infection cycle, NPVs produce two structurally and functionally distinct virion phenotypes: occlusion-derived virus (ODV) and budded virus (BV). ODV is occluded in polyhedra or occlusion bodies and is required for the oral infection of insects. ODVs are released from the occlusion body by the alkaline environment within the midgut lumen of the larva and subsequently initiate primary infection of the mature columnar epithelial cells of the midgut. BVs are produced when nucleocapsids bud through the plasma membrane of the midgut epithelial cells to initiate secondary infections within the infected animal (12, 27). ODVs are highly infectious to the midgut epithelial cells and mediate animal-to-animal transmission but have very low infectivity when injected directly into the hemocoel of insects or when used to infect cultured insect cells (56, 57). However, BVs are highly infectious for tissues of the hemocoel and for cultured cells.

Baculovirus infection progresses in three phases, early, late, and very late, in cultured insect cells. A complex cascade of transcription and protein synthesis occurs within the first 6 to 8 h following viral infection (11). The progression from early to late stages of infection coincides with the start of viral DNA replication between 6 and 12 h postinfection (p.i.) (4). Newly replicated viral DNA is condensed and packaged into capsid structures within the nucleus to form nucleocapsids (32). Nucleocapsids initially egress from the nucleus, migrate through the cytoplasm, and bud through a modified plasma membrane to acquire an envelope to form BVs (39). During the late phase of infection, beginning at about 20 h p.i., there is a switchover by some unknown mechanism from BV to ODV production. Nucleocapsids then remain within the nucleus and develop an envelope de novo to form ODVs, which then become incorporated within the matrix of the occlusion body (60).

The ie0 mRNA is the only known spliced gene product expressed from the AcMNPV genome. The ie0 transcriptional unit spans the region from exon0 (open reading frame [ORF] 141) to ie1 (ORF 147) and contains an intron of 4,528 bp (8, 28, 29). The resulting ie0 mRNA consists of 114 nucleotides (nt) from the 5′ end of exon0, 48 nt from the untranslated region of ie1, and the entire ie1 coding region (Fig. 1) (8, 28, 29). The ie0 intron region is transcriptionally complex, and multiple transcripts are produced during the early and late phases of infection (8, 28, 29). The ie0 intron contains six ORFs, of which two, orf143 and orf144, code for the ODV envelope proteins, ODV-E18 and ODV-EC27, respectively (7). The four remaining ORFs, exon0, orf142, orf145, and orf146, have not been characterized.

FIG. 1.

(A) Schematic map of the exon0-ie0-ie1 gene region showing the transcription and splicing pattern of ie1 and ie0 and the relative positions and orientations of the exon0 (orf141), ie1, ie0, me53, orf142, orf143, orf144, orf145, orf146, and odv-e56 ORFs. The ie0 intron and transcript are indicated as a dotted line and solid line respectively, above the ORFs. The resulting spliced ORF of IE0 is shown indicating the regions that originate from exon0 (black), ie1 UTR (white), and ie1 (grey). On the basis of the locations of polyadenylation signals, potential exon0 transcripts are indicated below the ORFs. Solid arrows agree with the observed sizes on Northern blots. (B) Northern blot analysis of exon0 transcription in AcMNPV-infected Sf9 cells from 3 to 72 h p.i. The location of the strand-specific probe is shown above the exon0 ORF in panel A (black line). Numbers above each lane indicate the time (hours) p.i. when RNA was isolated. The sizes of exon0 RNAs are indicated on the right. (C) 5′ RACE analysis of the exon0 transcriptional start site. Alignment of the ie0-exon0 promoter with the sequence obtained with exon0-specific primers (GSP-2A, GSP-2B). The TATA box (TATAAA), early transcriptional start site (CAGT), and late promoter (ATAAG) are shown in bold, and the translation start codon is underlined. The arrowhead shows the location of the transcription initiation site of exon0.

exon0 is a highly conserved gene found in all lepidopteran baculoviruses of the genus Nucleopolyhedrovirus, which have been completely sequenced (20, 21). No function has been ascribed to this gene other than its association with ie0, which utilizes only 114 nt of the 786-nt ORF. Previous attempts to delete exon0 from the AcMNPV genome by the standard approach of homologous recombination in insect cells were unsuccessful (unpublished data), suggesting that it is an essential gene. In this study, we have used AcMNPV bacmids (31) to successfully generate an AcMNPV exon0 knockout mutant by homologous recombination in Escherichia coli. The AcMNPV exon0 knockout mutant had drastically reduced production of BV and exhibited a single-cell infection phenotype. These results show that EXON0 plays a key role in BV production and therefore the AcMNPV replication cycle.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viruses and cells. The AcMNPV bacmid bMON14272 (Invitrogen Life Technologies) was derived from AcMNPV strain E2 and maintained in DH10B cells as described previously (33). Sf9 (Spodoptera frugiperda IPLB-Sf21-AE clonal isolate 9) insect cells were cultured in suspension at 27°C in TC100 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum.

Construction of exon0 knockout AcMNPV bacmid.

We used the AcMNPV bacmid to generate exon0 knockout virus by recombination in E. coli as previously described (31). An exon0 knockout transfer vector was constructed as follows. A 2,876-bp HindIII-NarI fragment containing the exon0 coding region was excised from the AcMNPV EcoRI-B fragment, and the NarI site was filled in with Pfu DNA polymerase. The fragment was cloned into pBS+, which had been digested with HindIII and EcoRI, and the EcoRI site was filled in with Pfu DNA polymerase to produce pAcExon0-1. A 483-bp XhoI-AgeI fragment containing the zeocin resistance gene under the control of the EM7 promoter was amplified from p2Zop2F (19). With pAcExon0-1 as the template, a 5,673-bp fragment was amplified with primers 507 (5′TTCTATACCGGTGTACGTGAACGAGT3′) and 508 (5′GGCGTTGTACTCGAGAAAGAAAACAAAG3′), which contain AgeI and XhoI sites. This PCR product resulted in a 383-bp deletion of the exon0 ORF but retained the flanking sequences of exon0 and the splice site of ie0. The PCR fragment was ligated to the 483-bp XhoI-AgeI EM7-zeocin resistance gene cassette to give the exon0 knockout transfer vector pAc-exon0-KO. This transfer vector therefore contains a 2.9-kbp HindIII-EcoRI fragment composed of 1,547 bp of 5′ flanking sequence containing 142 bp of the 5′ coding region of exon0 that retains the splice site of ie0 and 543 bp of 3′ flanking sequence containing 261 bp of the exon0 ORF that retains the promoter of downstream orf142.

An exon0 knockout AcMNPV bacmid was generated by using a modification of the λ phage Red recombinase system described by Datsenko and Wanner (9). The transfer vector pAc-exon0-KO was digested with EcoRI and HindIII, and the resulting linear 2.9-kbp fragment was gel purified. E. coli BW25113-pKD46 cells were electroporated with the 2.9-kbp fragment (0.2 μg) and AcMNPV bacmid bMON14272 DNA (1 μg). The electroporated cells were incubated at 37°C for 4 h in 3 ml of SOC medium (9) and placed onto agar medium containing 30 μg of zeocin per ml and 50 μg of kanamycin per ml. Plates were incubated at 37°C overnight, and colonies resistant to zeocin and kanamycin were selected and confirmed by PCR.

Four different primer pairs were used to confirm that exon0 had been deleted from the exon0 locus of the AcMNPV bacmid genome. Primers A1 and A2 (5′CGCAACAGGATCCGAACCAGCAGTC 3′ and 5′CTTTTGGATCCACAACAGGCAATTTGAT 3′, respectively) were used to detect the correct insertion of the zeocin gene cassette. Primers B1 and B2 (5′ TGTATATGCGTAGGAGAGCC 3′ and 5′ CTCGCAACTGTTTCAAGTAC 3′, respectively) were used to confirm the loss of the exon0 coding region. Primers C1 and C2 (5′ GGAAACCTGGTGCGCCATCT 3′ and 5′ CCGGAACGGCACTGGTCAACTT 3′, respectively) and D1 and D2 (5′ CTGTACGCCGAGTGGTCGGAGGTCG 3′ and CATGTCCTCGCCCAGTAGAT 3′, respectively) were used to examine the recombination junctions of the upstream and downstream flanking regions. One recombinant bacmid with all of the correct PCR confirmations was selected and named Ac-exon0-KO-ph−.

Construction of donor plasmids.

The phenotype of the commercial AcMNPV bacmid is polyhedrin gene negative. To generate exon0 knockout and wild-type (WT) AcMNPV bacmids containing the polyhedrin gene cassette, a donor plasmid called pFAcT-GFP was constructed as follows. pFastBac (Invitrogen Life Technologies) was digested with BamHI and SnaBI, the ends were filled in and made blunt with T4 DNA polymerase, and self-ligation of the fragment resulted in pFastBac-polh−. A PCR fragment containing the AcMNPV polyhedrin gene ORF under the control of its own promoter was amplified with primers 472 (5′TAACAGCCATTGTAATGAGACGCAC3′) and 480 (5′GCTAACACGCCCTAGGTTAAATATGTC3′, respectively) with AcMNPV genomic DNA as the template. The PCR fragment was inserted into pFastBac-polh−, which had been HindIII digested and filled with T4 DNA polymerase, to give pFAcT. A BamHI fragment containing the green fluorescence protein (gfp) ORF was PCR amplified with primers 242 (5′CCAGGATCCAACCATGGTGAGCAAGGGCG3′) and 243 (5′GCGGGATCCTTACTTGTACAGCTCGTCCA3′) with PE38-GFP (37) as the template. The BamHI fragment was cloned into BamHI-digested OpIE1-CAT-SalI (51) to produce OpIE1-GFP-SalI. Finally, a SalI fragment containing gfp under the control of the Orgyia pseudotsugata multiple nuclear polyhedrosis virus (OpMNPV) ie1 promoter was excised from OpIE1GFPSalI and ligated into SalI-digested pFAcT to result in pFAcT-GFP.

As a control an exon0 repair AcMNPV bacmid was generated. A donor plasmid, pFAcT-GFP-exon0-pA, was constructed as follows. An 890-bp XhoI-XbaI fragment containing the exon0 coding region and its late promoter region was amplified with upper primer 518 (5′ CGTAACTCGAGATCAATTGTGCTC 3′) and lower primer 519 (5′ ACTCATCTAGAGTTGCGTGCTTATT 3′) with pAcExon0-1 as the template. The fragment was inserted into XhoI-XbaI-digested pFAcT-GFP to produce pFAcT-GFP-exon0. A poly(A) signal of OpMNPV ie1 was excised as a 465-bp BamHI-HindIII fragment from OpIE1-CAT-SalI and blunt ended with the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I. The poly(A) signal was cloned into pFAcT-GFP-exon0, which had been digested with XbaI and blunt ended, giving pFAcT-GFP-exon0-pA.

Construction of knockout, repair, and WT AcMNPV bacmids containing polyhedrin and gfp.

AcMNPV bacmids containing the polyhedrin and gfp cassettes were generated by Tn7-mediated transposition as previously described by Luckow et al. (33). Electrocompetent DH10α cells containing both pMON7124 (Invitrogen Life Technologies) and bacmid Ac-exon0-KO-Zeo or bMON14272 were transformed with donor plasmid pFAcT-GFP-exon0-pA or pFAcT-GFP (∼0.2 μg). The transformed cells were incubated at 37°C for 4 h in 3 ml of SOC medium and placed onto agar medium containing 30 μg of zeocin per ml, 50 μg of kanamycin per ml, 7 μg of gentamicin per ml, 10 μg of tetracycline per ml, 100 μg of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) per ml, and 40 μg of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) per ml. Plates were incubated at 37°C for a minimum of 48 h, and white colonies resistant to kanamycin, gentamicin, tetracycline, and zeocin were selected and streaked onto new plates to confirm the phenotype and then verified by PCR. Primers A1 and A2 produced single fragments of 676 and 573 bp for Ac-exon0-KO and Ac-WT, respectively, and both fragments for Ac-exon0-repair. Primers B1 and B2 produced no PCR product in Ac-exon0-KO or Ac-exon0-repair but a 640-bp product in Ac-WT. Primers C1 and C2 produced a single 2.1-kb band in Ac-exon0-KO and Ac-exon0-repair but no product in Ac-WT. Similarly, primers D1 and D2 produced a single 1.02-kb band in Ac-exon0-KO and Ac-exon0-repair but no product in Ac-WT. Transposition events were confirmed by gfp expression and occlusion body formation in bacmid DNA-transfected Sf9 cells.

Time course analysis of BV production and protein synthesis.

Sf9 cells (2.0 × 106/35-mm-diameter six-well plate) were transfected with 2.0 μg of each bacmid (Ac-exon0-KO, Ac-exon0-repair, or Ac-WT) or infected with BV. For titration of BV production at various times posttransfection (p.t.) or p.i., culture medium was harvested by centrifugation (8,000 × g for 5 min) to remove cell debris. BV production was determined in duplicate by endpoint dilution in Sf9 cells with 96-well microtiter plates. For time course analysis of GP64, IE1, and IE0 protein expression at the designated times p.t., cells were harvested and pelleted (8,000 × g for 5 min) and proteins from 5 × 104 cell equivalents were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and Western blotting.

Plaque assay.

Sf9 cells (3.0 × 106 per 60-mm-diameter dish) were infected with Ac-exon0-KO or Ac-WT. Cells were incubated with viral inoculum for 1 h with gentle rocking at room temperature. The viral inoculum was removed, and the cells were washed with 1 ml of Grace’s medium. Cells were overlaid with 4 ml of TC-100 medium containing 1.5% low-melting-point agarose (SeaPlaque) pre-equilibrated to 37°C, followed by incubation at 27°C.

BV partial purification and concentration.

At 96 h p.t., medium was harvested and BVs were purified as previously described by Oomens and Blissard (43). Briefly, supernatants were cleared of cell debris (2,000 × g for 20 min) at room temperature in a GS-6R centrifuge. Supernatant (3 ml) was loaded onto a 25% sucrose cushion and centrifuged at 80,000 × g for 80 min at 4°C in an SW60 rotor. BV pellets were resuspended in 37.5 μl of 250 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.8)-30 μg of E-64 per ml and incubated at room temperature for 10 min, followed the addition of 12.5 μl of 4× protein sample buffer (200 mM Tris-Cl [pH 6.8], 8% [wt/vol] SDS, 400 mM dithiothreitol, 20% [vol/vol] glycerol, 0.1% bromphenol blue). Samples were boiled for 4 min, and 9 μl of each sample was analyzed by SDS-12% PAGE and Western blotting.

Northern blot and rapid amplification of 5′ cDNA ends (5′ RACE) analyses of AcMNPV exon0 transcription.

For the synthesis of a single-stranded exon0 RNA Northern blot probe, plasmid pLITMUS-exon0-B was constructed. A 433-nt BamHI fragment from within the AcMNPV exon0 ORF was PCR amplified with upper primer 511 (5′TTGGATCCACATGTACAACGCCGACAT3′) and lower primer 510 (5′CTTTTGGATCCACAACAGGCAATTTGAT3′) with pAcExon0-1 as the template. This fragment was cloned into BamHI-digested pLITMUS to give pLITMUS-exon0-B. The probe was generated by digesting pLITMUS-exon0-B with BglII, followed by RNA synthesis with T7 RNA polymerase by standard methods (16).

RNA was extracted from Sf9 cells (2.0 × 106/35-mm-diameter six-well plate) infected with AcMNPV at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 at the designated times p.i. with the RNeasy mini kit (QIAGEN). Total RNA (5 μg) from each time point was separated by electrophoresis in a 1% formaldehyde gel, blotted, and hybridized to an α-32P-radiolabed exon0 probe. The blot was visualized by exposure to Kodak Phosphorscreens and developed with a Storm PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics).

5′ RACE was performed to map the transcriptional initiation site of exon0 mRNAs as described previously (52). Briefly, first-strand cDNA synthesis was performed with 5 μg of total RNA isolated from AcMNPV-infected Sf9 cells at 12 h p.i. with negative-sense AcMNPV exon0 gene-specific primer GSP-1 (5′ATTTATACGATGTCCTGCACGCTGG3′). The first-strand cDNA was tailed, and second-strand cDNA synthesis was carried out with positive-sense oligonucleotide XBEdT (5′CTCGAGGGATCCGAATTCTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT3′). The exon0 5′ ends were amplified with positive-sense oligonucleotide XBE-1 (5′ GCCTCGAGGGATCCGAATTC 3′) and one of two exon0-specific, negative-sense primers, GSP-2A and GSP-2B (5′GGCATCTAGATATTAACTCGTTCACGT3′ and 5′GGCATCTAGAATAAAATGGTGACAG3′, respectively).

Slot blot analysis of viral DNA replication.

Sf9 cells (2.0 × 106/35-mm-diameter six-well plate) were transfected with 2.0 μg of DNA of each bacmid (Ac-exon0-KO, Ac-exon0-repair, or Ac-WT). At designated times p.t., cells were harvested and pelleted (8,000 × g for 5 min). Each pellet was resuspended in 500 μl of 0.4 M NaOH-125 mM EDTA and incubated at 100°C for 10 min to disrupt the cells. Each sample (30 μl) was loaded onto a Schleicher & Schuell slot blot apparatus in duplicate and blotted under vacuum onto a Hybond-N nylon membrane (Amersham). The slot blot was hybridized to an α-32P-radiolabed EcoRI-T fragment of AcMNPV DNA by standard methods (16). The blot was visualized by exposure to Kodak Phosphorscreens, developed with a Storm PhosphorImager, and quantified with ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics).

Western blot analysis.

Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE (30) with a Bio-Rad Mini-Protean II apparatus and transferred to Millipore Immobilon-P membrane with a Bio-Rad liquid transfer apparatus. Western blot hybridizations were performed by standard methods (16). Three primary antibodies were used in this study: (i) GP64 antibody, mouse monoclonal antibody AcV5, 1:2,000 dilution (24); (ii) AcMNPV IE1 antibody, mouse monoclonal antibody IE1-4B7, 1:750 dilution (48); (iii) OpMNPV VP39 antibody, mouse monoclonal antibody α-39K OpMNPV, 1:1,000 dilution (45). After incubation with a 1:20,000 dilution of peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody, signals were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL; Amersham).

RESULTS

exon0 transcriptional analysis.

The ie0/exon0 promoter contains both early and late transcriptional start motifs (TATA-CAGT and ATAAG, respectively) (Fig. 1A). Previous analysis has shown that ie0 transcription initiates at the early promoter motif TATA-CAGT (28, 52), but it was unknown whether exon0 is transcribed as an early or a late gene. To analyze only exon0 transcription by Northern blotting, we used a probe from within the exon0 coding region downstream of the ie0 splice site (Fig. 1A). The Northern blot analysis detected three RNAs from 12 to 72 h p.i. that were 3.4, 4.2, and 6.3 kb in size (Fig. 1B). The 3.4-kb RNAs was not detected until the onset of DNA replication at 12 h p.i., but the steady-state levels increased up to at least 36 h p.i. The 4.2- and 6.3-kb RNAs were detected by 24 h p.i. and reached maximal steady-state levels by 48 h p.i. and then declined by 72 h p.i. These results indicate that AcMNPV exon0 is transcribed as a late gene and the mRNA sizes agree with transcriptional initiation at the late promoter motif ATAAG (Fig. 1A).

5′ RACE was performed with two exon0-specific primers, and the resulting PCR products were sequenced directly (Fig. 1 C). The sequence data confirm the Northern blotting result showing that exon0 is a late gene as it initiates from the second A of the late promoter motif ATAAG.

EXON0 homologues contain a conserved RING finger motif.

The exon0 ORF is highly conserved and appears to be associated with all of the sequenced genomes of members of the genus Nucleopolyhedrovirus that infect lepidoptera. Homologs of EXON0 were not identified in the six sequenced genomes of the genus Granulovirus, the mosquito baculovirus Culex nigripalpus NPV, or the sawfly baculovirus Neodiprion lecontei NPV as recently reported by Lauzon et al. (30a). An alignment of the predicted EXON0 sequences is shown in Fig. 2. The N terminus region, which corresponds to the amino acids that form part of IE0, is not highly conserved and is variable in length. Conserved regions of EXON0 include a predicted coiled-coil leucine-rich domain, which is known to be involved in protein-protein interactions (34). At the C terminus there is a predicted highly conserved RING finger motif whose consensus differs from that of most other known proteins of this type. The consensus RING motif of EXON0 is C3Y/FC4, compared to the normal motif of C3HC4 (10), showing that the histidine is replaced with a tyrosine or phenylalanine (Fig. 2). The only other proteins we identified that contain a similar substitution in the RING finger motif were the orthologs of NOT4 which are subunits of a complex that regulates RNA polymerase II gene expression (15). In addition, EXON0 also contains an additional conserved cysteine adjacent to the third cysteine of the RING motif.

FIG. 2.

Alignment of EXON0 homologues from 13 baculovirus NPVs. The alignment was performed with the ClustalW algorithm (53). Identical and conserved amino acids are boxed, and regions with greater than 70% identity are shaded. Conserved cysteine and tyrosine residues in the predicted RING finger motif at the C terminus are indicated by arrowheads. The consensus RING finger motif is shown below the alignment (10). The predicted leucine-rich coiled coil and the amino acids spliced to IE1 to form IE0 are indicated by black lines above the alignment.

Generation of exon0 knockout bacmid.

To construct an exon0 knockout virus we had to ensure that the deletion did not affect ie0 or orf142, which has been recently shown to be one of the 30 core baculovirus genes (21). Therefore, to construct an exon0 knockout bacmid, 142 bp of the 5′ end and 261 bp of the 3′ end of the exon0 coding region were retained in order to preserve the ie0 splice site and the orf142 promoter, respectively (3). The remaining coding sequences were deleted and replaced with the EM7-zeocin resistance gene cassette. An exon0 knockout virus containing the polyhedrin and gfp genes was generated by transposition of polyhedrin and gfp into the polyhedrin locus of Ac-exon0-ph−, and this virus was named Ac-exon0-KO (Fig. 3B). As a control, repair virus Ac-exon0-repair was generated in which exon0, under control of its own late promoter, was inserted by transposition into the polyhedrin locus (Fig. 3B). A WT virus, Ac-WT, was also constructed by inserting the polyhedrin and gfp genes into the polyhedrin locus of WT AcMNPV bacmid bMON14272 (Fig. 3B). All constructs were confirmed by diagnostic PCRs as shown in Fig. 3D and described in Materials and Methods.

FIG. 3.

Construction of exon0 knockout, repair, and WT AcMNPV bacmids. (A) Schematic diagram of the transfer vector, Ac-exon0-KO, used to generate the exon0 knockout bacmid by recombination in E. coli. pAc-exon0-KO contains the zeocin resistance gene under the control of the EM7 promoter, 1,547 bp of the upstream exon0 flanking region, and 543 bp of the downstream exon0 flanking region. This leaves the ie0 splice site and the orf142 promoter region intact. (B) Schematic diagram of three viruses, Ac-exon0-KO, Ac-exon0-repair, and Ac-WT, showing the genes inserted into the polyhedrin locus by Tn7-mediated transposition. polh, polyhedrin; gfp, green fluorescent protein. (C) Positions of primer pairs used in the analysis of the WT locus and exon0 knockout locus to confirm the deletion of the exon0 ORF and correct insertion of the zeocin resistance gene cassette. Primers are indicated by arrows designated A through D. (D) Confirmation by PCR analysis of the presence or absence of sequence modifications in Ac-exon0-KO, Ac-exon0-repair, and Ac-WT. The virus analyzed is shown above each lane, and the primer pairs used are shown below.

Analysis of Ac-exon0-KO, Ac-exon0-repair, and Ac-WT replication in transfected Sf9 cells.

To determine the effect of deleting exon0 on virus replication, a virus growth curve experiment was performed for Ac-exon0-KO, Ac-exon0-repair, and Ac-WT. At 48 h p.t., the titers of Ac-exon0-repair and Ac-WT peaked at 1.5 × 108 to 2 × 108 50% tissue culture infective doses (TCID50)/ml; however, the titer of Ac-exon0-KO was only 2 × 104 TCID50/ml (Fig. 4A). Even at 96 h p.i., the titer of Ac-exon0-KO was still 1,000-fold lower than those of Ac-exon0-repair and Ac-WT (Fig. 4A). As the levels of BV production from Ac-exon0-repair and Ac-WT were the same (Fig. 4A), this indicates that the phenotype of Ac-exon0-KO is derived from the deletion of exon0. We can conclude from these initial results that deletion of exon0 causes a reduction of infectious BV production of greater than 99.9% in bacmid-transfected cells.

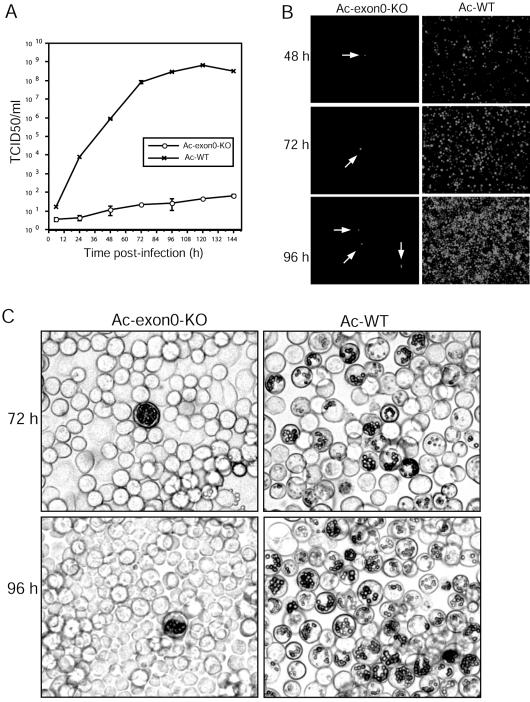

FIG. 4.

Analysis of viral replication by the exon0 knockout virus in bacmid DNA-transfected Sf9 cells. (A) Virus growth curves of Ac-exon0-KO, Ac-exon0-repair, and Ac-BAC-WT in Sf9 cells. Cells (2.0 × 106) were transfected with 2.0 μg of DNA of each virus. Cells were harvested at the indicated time points p.i., and the cell culture supernatants were harvested and assayed for the production of infectious virus by TCID50 assay. Each datum point represents the average titer derived from two independent TCID50 assays. Error bars represent standard errors. (B) Fluorescence microscopy of Ac-exon0-KO-, Ac-exon0-repair-, and Ac-WT-transfected Sf9 cells at 18 and 48 h p.t. (C) Light microscopy of Ac-exon0-KO-, Ac-exon0-repair-, and Ac-WT-transfected cells at 48, 72, and 96 h p.t.

Ac-exon0-KO-, Ac-exon0-repair-, and Ac-WT bacmid-transfected cells were also monitored for infection by fluorescence due to expression of gfp, which was under the control of the OpMNPV ie1 promoter (Fig. 3). Fluorescence can be detected in transfected cells by 6 to 12 h p.t., and no difference was observed among the three viruses before 18 h p.i. (Fig. 4B), indicating comparable transfection efficiencies of approximately 30%. Fluorescence was observed in almost all Ac-WT- and Ac-exon0-repair-transfected cells by 48 h p.t., indicating virus spread throughout the cell culture. In contrast, however, Ac-exon0-KO-infected cells showed only a slight increase in the number of infected cells (Fig. 4B). Even by 96 h p.t., fluorescence was only observed in approximately 40% of the cells transfected with Ac-exon0-KO (data not shown), indicating that there is very little spread of the virus beyond the cells initially transfected with the bacmid DNA.

Microscopic analysis of Ac-exon0-KO-, Ac-exon0-repair-, and Ac-WT-transfected cells revealed that early occlusion bodies appear by 28 to 30 h p.t., with no difference detected among the three bacmids (data not shown). At 48 h p.t., approximately 30 to 40% of the cells contained occlusion bodies, which corresponds to the number of cells initially transfected (Fig. 4C). However, by 72 h p.t., significant differences were observed between Ac-exon0-KO and Ac-exon0-repair or Ac-WT. By 72 to 96 h p.t. nearly all of the Ac-exon0-repair- or Ac-WT-transfected cells contained early or mature occlusion bodies, including those not originally transfected (Fig. 4C). In contrast, the Ac-exon0-KO transfection produced occlusion bodies in only the approximately 30 to 40% cells initially transfected. In addition, the majority of neighboring cells did not produce occlusion bodies even by 96 h p.t. (Fig. 4C). These results show that occlusion body formation in the initially transfected cells was approximately the same for all three viruses but the Ac-exon0-KO infection did not spread beyond the primary infected cells. Bacmid-transfected cells have therefore shown that deletion of exon0 has a dramatic effect on the production of BV and spread of the virus but does not affect production of occlusion bodies.

Analysis of Ac-exon0-KO and Ac-WT replication in BV-infected Sf9 cells.

To confirm our initial results obtained by bacmid DNA transfection, we performed a second time course analysis with the BV produced from bacmid-transfected cells. A low MOI (0.0002) was used so that any differences in the production and spread of the virus would be accentuated. The repair bacmid Ac-exon0-repair was not used for this analysis as PCR analysis revealed that the recombination between the repair locus and the exon0 deletion locus could be detected by 30 h p.t. generating WT virus (data not shown). Results of this time course analysis revealed that after infection with very low MOIs the BV titers of Ac-WT rapidly reached peak levels (3 × 108 TCID50/ml) at approximately 96 h p.i. (Fig. 5A). In contrast, Ac-exon0-KO had produced only 64 TCID50/ml even by 144 h p.i. (Fig. 5A), resulting in a titer 107 lower than that produced by Ac-WT.

FIG. 5.

Analysis of viral replication by the exon0 knockout virus in BV-infected Sf9 cells. (A) Virus growth curves of Ac-exon0-KO and Ac-WT in Sf9 cells. 2.0 × 106 cells were infected at an MOI of 0.0002 from each virus, and supernatants were harvested at the indicated time points p.i. and assayed for the production of infectious virus by TCID50 assay. Each datum point represents the average titer derived from two independent TCID50 assays. Error bars represent standard errors. (B) Fluorescence microscopy of Ac-exon0-KO- and Ac-WT-infected Sf9 cells at 48, 72, and 96 h p.t. The single or few cells infected by Ac-exon0-KO are indicated by the arrows. (C) Light microscopy of Ac-exon0-KO- and Ac-WT-infected cells at 72 and 96 h p.t.

Cell-to-cell spread of Ac-WT and Ac-exon0-KO in infected Sf9 cells was monitored by fluorescence and occlusion body formation (Fig. 5B and C). By 24 h p.i., because of the very low MOI, only a few isolated cells with fluorescence were observed and no difference was detected between Ac-WT and Ac-exon0-KO (data not shown). However, by 48 h p.i. 30 to 40% of the cells infected with Ac-WT exhibited fluorescence, and this increased to 100% by 72 h p.i., indicating rapid spread of the virus infection (Fig. 5B). In contrast, Ac-exon0-KO-infected cells exhibited predominately a single-cell infection phenotype that persisted up to 96 h p.i. (Fig. 5B). Similar results were obtained in the observation of occlusion body formation. By 72 h p.i., occlusion bodies were observed in about 70% of the Ac-WT-infected cells and almost all cells contained occlusion bodies by 96 h p.i. (Fig. 5C). However, in cells infected with Ac-exon0-KO occlusion bodies were observed only in a few single cells (Fig. 5C). The number and size of the occlusion bodies in the single Ac-exon0-KO-infected cells were similar to those observed with Ac-WT. These results indicated that Ac-exon0-KO BV infection was restricted primarily to the cells initially infected, supporting the conclusion that exon0 is required for efficient production of BV.

To further compare the spread of virus infections between Ac-exon0-KO and Ac-WT, we performed plaque assays to restrict virus spread to adjoining cells (Fig. 6A). By 5 days p.i., Ac-WT produced large normal plaques. In comparison, the Ac-exon0-KO plaques consisted primarily of a single cell or a few adjoining cells, showing that this virus is unable to spread. Interestingly, at the very late phases of infection with Ac-exon0-KO, the majority of cells exhibited a single-cell infection phenotype, but a few foci exhibited multicell infections (Fig. 6B). Four typical types of infection were observed with Ac-exon0-KO (Fig. 6B). The majority were (i) single-cell infections (∼80%) (Fig. 6Ba) or (ii) 2- to 4-cell infections (∼15 to 20%) (Fig. 6Bb and c), and (iii) occasionally approximately 20 or more infected cells grouped together (Fig. 6Bd, e, and f).

FIG. 6.

Plaque assay analysis of Ac-exon0-KO and Ac-WT in infected Sf9 cells. (A) Fluorescence microscopic analysis of plaques formed by Ac-exon0-KO- and Ac-WT-infected Sf9 cells at 5 days p.i. demonstrating the inability of Ac-exon0-KO to spread the infection via BV. The single or few cells infected by Ac-exon0-KO are indicated by the arrows. (B) Fluorescence microscopy of the types of infected-cell foci that contain single or few cells that are observed in Ac-exon0-KO-infected cells.

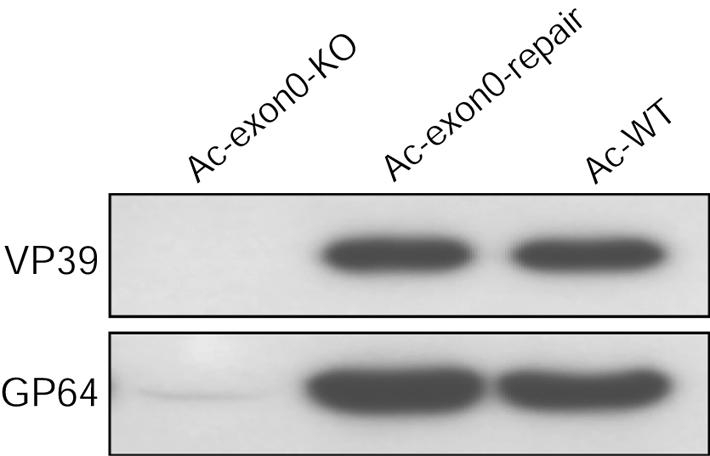

Western blot analysis of purified Ac-exon0-KO BV.

The virus growth curves and microscopy revealed that extremely low titers of infectious BVs were being produced in Ac-exon0-KO-transfected or -infected Sf9 cells (Fig. 4, 5, and 6). It is possible that (i) BVs were not budding from the infected cells or (ii) normal levels of BVs were produced but these virions were noninfectious. To address this issue we purified BV from bacmid-transfected cell supernatants and did a Western blot analysis to compare the levels of nucleocapsid protein VP39 and envelope protein GP64 (Fig. 7). Similar levels of GP64 and VP39 were detected from the Ac-exon0-repair- and Ac-WT-transfected cells (Fig. 7). Analysis of Ac-exon0-KO-transfected cell supernatant failed to detect any nucleocapsid protein VP39, even with a longer exposure time (Fig. 7). The GP64 results were very similar, except that a very faint signal was detected in Ac-exon0-KO (Fig. 7), but in comparison to Ac-WT or Ac-exon0-repair the levels were drastically reduced. Taken together, these results show that BV particles are absent or at extremely low levels in Ac-exon0-KO-transfected cell culture, indicating that nucleocapsids are inhibited from budding from Ac-exon0-KO-infected cells.

FIG. 7.

Western blot analysis of purified BV particles. Viral particles were purified from supernatants of Sf9 cells that had been transfected with Ac-exon0-KO, Ac-exon0-repair, or Ac-WT. Samples were analyzed with two monoclonal antibodies specific for nucleocapsid protein VP39 and BV-specific protein GP64.

exon0 deletion does not affect onset of viral DNA replication.

To determine whether deletion of exon0 affects other aspects of AcMNPV replication, we compared the onset and levels of viral DNA replication in Ac-exon0-KO-, Ac-exon0-repair-, and Ac-WT-transfected cells. Cells from transfected Sf9 cells were collected at designated time points, and cell lysates were prepared and subjected to slot blot analysis of viral DNA replication. The results showed that the three viruses had the same time of onset of viral replication between 12 and 18 h p.t. In addition, the levels of viral DNA replication were the same up to 30 h p.t. (Fig. 8A and B). After 30 h p.t., the levels of Ac-WT and Ac-exon0-repair started to increase exponentially whereas that of Ac-exon0-KO increased linearly. The difference observed after 30 h p.t. between Ac-exon0-KO- and Ac-exon-repair- or Ac-WT-transfected cells corresponded to the initiation of replication from secondary BV infections. As shown in Fig. 4, BV production was under way by 18 h p.t. and DNA replication from BV-infected cells started at approximately 10 to 12 h p.i. (37), which would mean that DNA replication from secondary BV infections would initiate at approximately 28 to 30 h p.t. These results therefore suggest that the onset and level of replication in individual infected cells are unaffected by deletion of exon0. It is also possible that EXON0 has a direct effect on DNA replication like other AcMNPV RING finger proteins such as IE2 and PE38.

FIG. 8.

Slot blot analysis of viral DNA replication. (A) Sf9 cells (2.0 × 106) were transfected with 2.0 μg of Ac-exon0-KO, Ac-exon0-repair, or Ac-WT DNA. At the designated times p.t., cells were harvested and cell lysates were prepared for slot blot analysis. The EcoRI-T fragment of AcMNPV was labeled with [32P]dCTP and used as a hybridization probe. On the left are the times p.t. (B) Quantitative analysis of viral DNA replication by slot blot analysis. DNA was quantified by PhosphorImager analysis, and each datum point represents the average from two independent transfections. Error bars represent the standard errors.

exon0 deletion does not affect IE1, IE0, and GP64 expression.

As described above, exon0 also contains the 5′ exon of ie0. IE0 is known to affect both early and late gene expression (25, 29, 52). Therefore, to confirm that deletion of exon0 did not affect the expression of IE0 we compared expression levels of both IE0 and IE1 by Western blotting. Up to 24 h p.t., prior to the onset of BV secondary infections, no difference was observed in the expression of IE0 or IE1 in Ac-exon0-KO-transfected cells compared to Ac-exon0-repair- or Ac-WT-transfected cells (Fig. 9A). Therefore, disruption of the exon0 locus does not affect the regulation of ie0 or ie1.

FIG. 9.

Western blot time course analysis of IE1, IE0, and GP64 synthesis in Sf9 cells that have been transfected with Ac-exon0-KO, Ac-exon0-repair, or Ac-WT. IE1 and IE0 (A) and GP64 (B) were analyzed with monoclonal antibodies specific to each protein. Sf9 cells (2.0 × 106) were transfected with 2.0 μg of DNA of each virus. At the designated times p.t., cells were harvested and cell lysates were prepared for Western blot analysis. The locations of the IE0- and IE1-specific bands are indicated on the right.

As our results indicate that exon0 is required for efficient BV production, we were also interested in determining if deletion of exon0 affects the expression levels of GP64, which is essential for BV production in cultured insect cells and insect larvae (39). As shown in Fig. 9B, GP64 was detected by 18 h p.t. in the three Ac-exon0-KO-, Ac-exon0-repair-, and Ac-WT-transfected cells and increased up to at least 48 h p.t. (Fig. 9B). At 18 and 24 h p.t. prior to the onset of BV secondary infections, no significant differences in GP64 expression were observed in Ac-exon0-KO-transfected cells compared to that in Ac-exon0-repair- or Ac-WT-transfected cells. Therefore, deletion of exon0 does not affect the levels of expression of the essential BV-specific protein GP64.

DISCUSSION

With AcMNPV bacmids we have examined the role of EXON0 in the viral life cycle in cultured insect cells and have shown that EXON0 is required for efficient production of BV. Northern blotting and 5′ RACE showed that exon0 is transcribed as a late gene, suggesting that the majority, if not all, of the early transcripts are spliced to form ie0 transcripts (8, 28, 51). Deletion of exon0 results in a virus (Ac-exon0-KO) that progresses through the very late phases in Sf9 cells, as evidenced by the normal development of occlusion bodies in the nuclei of transfected or infected cells. No differences were observed in the onset of viral DNA replication and the levels of the major regulatory proteins IE1 and IE0 and the BV-specific protein GP64. BV production, however, is reduced by at least 3 orders of magnitude relative to that of the WT virus. The infection of Ac-exon0-KO was restricted primarily to the cells initially infected, exhibiting a single-cell infection phenotype, which was confirmed by infection at very low MOIs and by plaque assay (Fig. 5 and 6). EXON0 appears to be a key protein that is required for high levels of BV production.

A very low level of what appears to be infectious BV was detected in transfected or infected cells. As the expression of GP64 is unaffected by deletion of exon0, it is possible that the stochastic association of nucleocapsids with the plasma membrane, via a nondirected process, could also result in virus budding in a small proportion of cells. In addition, preoccluded virions have very low infectivity for insect cell culture (35, 57) and could also contribute to the titers observed.

The most extensively studied AcMNPV protein that is required for BV production is GP64, which is the major BV envelope protein of group I NPVs. GP64 is involved in viral attachment and membrane fusion during virus entry and is also required for efficient virion budding (6, 18, 43). During budding and assembly of BV, GP64 accumulates in discrete areas on the plasma membrane, and nucleocapsids bud from these sites (5, 38, 39, 54, 55, 60). GP64 is essential for BV production but does not affect the formation of infectious ODV and occlusion bodies in transfected cells, similar to what was observed with EXON0 (39).

A number of viral proteins have been shown to be essential for BV production but also alter nucleocapsid and ODV synthesis. For example, the AcMNPV ODV-specific protein GP41 failed to produce BV in cells infected with a gp41 temperature-sensitive mutant. Electron microscopy showed that nucleocapsids of the gp41 temperature-sensitive mutant are produced within the nucleus but fail to egress from the nucleus so that BV is not produced. GP41 is an O-glycosylated protein and localizes to the nucleus, suggesting that GP41 may be required for nucleocapsids to move from the virogenic stroma to or through the nuclear membrane or its pores (58, 59). At the nonpermissive temperature occlusion bodies did not form correctly in both the WT and the GP41 mutant (42). Therefore, it is not known if the effect of GP41 is specific for BV or for both viral phenotypes. Electron microscopy studies are required to determine if viral nucleocapsids of exon0 knockout viruses are also retained in the nucleus.

AcMNPV proteins VLF-1 and VP1054 have been shown to play a crucial role in the production of BVs and ODVs. AcMNPV vlf-1 regulates very late gene expression and is thought to be a member of the λ phage integrase family (36). It has been suggested that the DNA cleavage activity or topoisomerase activities of VLF-1 are involved in BV production (61, 62). AcMNPV VP1054 (ORF 54), a structural component of both BVs and ODVs, has been shown to be required for nucleocapsid assembly (41).

EXON0 is conserved in all of the viruses in the genus Nucleopolyhedrovirus (except the mosquito virus CuniNPV and the sawfly baculovirus N. lecontei NPV) that have been sequenced to date. Alignment of the EXON0 sequences revealed distinct motifs that include a predicted C-terminal RING finger motif and a coiled-coil region (Fig. 2). Of particular interest is the RING finger motif, which contains an extra conserved cysteine and a tyrosine or a phenylalanine in place of the normal histidine. By a PSI-BLAST analysis, the only proteins other than EXON0 shown to contain a similar substitution are the orthologs of NOT4 (1, 2, 15). Studies of NOT4 have shown that it is part of a complex that can be a negative regulator of RNA polymerase II-based transcription. In addition, the human form has been shown to function as an E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase subunit (1, 2, 15). Ubiquitination, which involves transfer of the 76-amino-acid ubiquitin to protein targets, has been shown to have multiple regulatory functions in cells, including targeting of proteins for degradation via the proteosome, cellular protein transport, and activation of transcription factors (22, 23, 26, 40, 46). Of particular interest to this study is that ubiquitination has also been shown to be required for the budding process of a number of enveloped viruses including rhabdoviruses and retroviruses (17, 44, 46, 49, 50). It is therefore possible that EXON0 functions as a ubiquitin-ligase to direct nucleocapsids to the plasma membrane for BV formation.

Related to the ubiquitination pathway is the AcMNPV gene that codes for a ubiquitin-related protein, Ac-UBI. An AcMNPV mutant with a frameshift mutation in Ac-ubi has 5- to 10-fold lower levels of BV compared to the WT and control viruses in infected Sf9 cells (47). It was also shown that Ac-UBI is a structural protein of BV particles of AcMNPV and a number of capsid proteins are conjugated to the viral ubiquitin protein (13, 14). As a result, it was suggested that Ac-UBI may be involved in the assembly or budding of viral particles from infected cells. It is unknown if there is a functional interaction between EXON0 and Ac-UBI, and further studies are required to address this possibility.

Acknowledgments

We thank Gary Blissard and Brian Federici for providing AcMNPV bacmid DNAs and Barry Wanner for providing the λ phage Red system. We also thank Kevin Wanner and Leslie Willis for excellent technical assistance.

Partial funding for this study was from a discovery grant and a network grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albert, T. K., H. Hanzawa, Y. I. Legtenberg, M. J. de Ruwe, F. A. van den Heuvel, M. A. Collart, R. Boelens, and H. T. Timmers. 2002. Identification of a ubiquitin-protein ligase subunit within the CCR4-NOT transcription repressor complex. EMBO J. 21:355-364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albert, T. K., M. Lemaire, N. L. van Berkum, R. Gentz, M. A. Collart, and H. T. Timmers. 2000. Isolation and characterization of human orthologs of yeast CCR4-NOT complex subunits. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:809-817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ayres, M. D., S. C. Howard, J. Kuzio, M. Lopez-Ferber, and R. D. Possee. 1994. The complete DNA sequence of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. Virology 202:586-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blissard, G. W. 1996. Baculovirus-insect cell interactions. Cytotechnology 20:73-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blissard, G. W., and G. F. Rohrmann. 1989. Location, sequence, transcriptional mapping, and temporal expression of the gp64 envelope glycoprotein gene of the Orgyia pseudotsugata multicapsid nuclear polyhedrosis virus. Virology 170:537-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blissard, G. W., and J. R. Wenz. 1992. Baculovirus gp64 envelope glycoprotein is sufficient to mediate pH-dependent membrane fusion. J. Virol. 66:6829-6835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braunagel, S. C., H. He, P. Ramamurthy, and M. D. Summers. 1996. Transcription, translation, and cellular localization of three Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus structural proteins: ODV-E18, ODV-E35, and ODV-EC27. Virology 222:100-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chisholm, G. E., and D. J. Henner. 1988. Multiple early transcripts and splicing of the Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus IE-1 gene. J. Virol. 62:3193-3200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:6640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freemont, P. S., I. M. Hanson, and J. Trowsdale. 1991. A novel cysteine-rich sequence motif. Cell 64:483-484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friesen, P. D. 1997. Regulation of baculovirus early gene expression, p. 141-166. In L. K. Miller (ed.), Baculovirus. Plenum Publishing Corporation, New York, N.Y.

- 12.Granados, R. R., and A. L. Lawler. 1981. In vivo pathway of Autographa californica baculovirus invasion and infection. Virology 108:297-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guarino, L. A. 1990. Identification of a viral gene encoding a ubiquitin-like protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:409-413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guarino, L. A., G. Smith, and W. Dong. 1995. Ubiquitin is attached to membranes of baculovirus particles by a novel type of phospholipid anchor. Cell 80:301-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanzawa, H., M. J. de Ruwe, T. K. Albert, P. C. van Der Vliet, H. T. Timmers, and R. Boelens. 2001. The structure of the C4C4 ring finger of human NOT4 reveals features distinct from those of C3HC4 RING fingers. J. Biol. Chem. 276:10185-10190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harlow, E., and D. Lane. 1999. Antibodies: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 17.Harty, R. N., M. E. Brown, J. P. McGettigan, G. Wang, H. R. Jayakar, J. M. Huibregtse, M. A. Whitt, and M. J. Schnell. 2001. Rhabdoviruses and the cellular ubiquitin-proteasome system: a budding interaction. J. Virol. 75:10623-10629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hefferon, K. L., A. G. Oomens, S. A. Monsma, C. M. Finnerty, and G. W. Blissard. 1999. Host cell receptor binding by baculovirus GP64 and kinetics of virion entry. Virology 258:455-468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hegedus, D. D., T. A. Pfeifer, J. Hendry, D. A. Theilmann, and T. A. Grigliatti. 1998. A series of broad host range shuttle vectors for constitutive and inducible expression of heterologous proteins in insect cell lines. Gene 207:241-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herniou, E. A., T. Luque, X. Chen, J. M. Vlak, D. Winstanley, J. S. Cory, and D. R. O'Reilly. 2001. Use of whole genome sequence data to infer baculovirus phylogeny. J. Virol. 75:8117-8126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herniou, E. A., J. A. Olszewski, J. S. Cory, and D. R. O'Reilly. 2003. The genome sequence and evolution of baculoviruses. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 48:211-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hershko, A., and A. Ciechanover. 1998. The ubiquitin system. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67:425-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hochstrasser, M. 1996. Protein degradation or regulation: Ub the judge. Cell 84:813-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hohmann, A. W., and P. Faulkner. 1983. Monoclonal antibodies to baculovirus structural proteins: determination of specificities by Western blot analysis. Virology 125:432-444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huijskens, I., L. Li, L. G. Willis, and D. A. Theilmann. 2004. Role of AcMNPV IE0 in baculovirus late gene activation and comparison with IE1 using transient assay. Virology, 323:120-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson, E. S. 2002. Ubiquitin branches out. Nat. Cell Biol. 4:E295-E298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keddie, B. A., G. W. Aponte, and L. E. Volkman. 1989. The pathway of infection of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus in an insect host. Science 243:1728-1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kovacs, G. R., L. A. Guarino, B. L. Graham, and M. D. Summers. 1991. Identification of spliced baculovirus RNAs expressed late in infection. Virology 185:633-643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kovacs, G. R., L. A. Guarino, and M. D. Summers. 1991. Novel regulatory properties of the IE1 and IE0 transactivators encoded by the baculovirus Autographa californica multicapsid nuclear polyhedrosis virus. J. Virol. 65:5281-5288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of the bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30a.Lauzon, H. A., C. J. Lucarotti, P. J. Krell, Q. Feng, A. Retnakaran, and B. M. Arif. 2004. Sequence and organization of the Neodiprion lecontei nucleopolyhedrovirus genome. J. Virol. 78:7023-7035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Lin, G., and G. W. Blissard. 2002. Analysis of an Autographa californica multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus lef-6-null virus: LEF-6 is not essential for viral replication but appears to accelerate late gene transcription. J. Virol. 76:5503-5514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu, A., P. Krell, J. M. Vlak, and G. F. Rohrmann. 1997. Baculovirus DNA replication, p. 171-192. In L. K. Miller (ed.), Baculovirus. Plenum Publishing Corporation, New York, N.Y.

- 33.Luckow, V. A., S. C. Lee, G. F. Barry, and P. O. Olins. 1993. Efficient generation of infectious recombinant baculoviruses by site-specific transposon-mediated insertion of foreign genes into a baculovirus genome propagated in Escherichia coli. J. Virol. 67:4566-4579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lupas, A. 1996. Coiled coils: new structures and new functions. Trends Biochem. Sci. 21:375-382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lynn, D. E. 2003. Comparative susceptibilities of insect cell lines to infection by the occlusion-body derived phenotype of baculoviruses. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 83:215-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McLachlin, J. R., and L. K. Miller. 1994. Identification and characterization of vlf-1, a baculovirus gene involved in very late gene expression. J. Virol. 68:7746-7756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Milks, M. L., J. O. Washburn, L. G. Willis, L. E. Volkman, and D. A. Theilmann. 2003. Deletion of pe38 attenuates AcMNPV genome replication, budded virus production, and virulence in Heliothis virescens. Virology 310:224-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Monsma, S. A., and G. W. Blissard. 1995. Identification of a membrane fusion domain and an oligomerization domain in the baculovirus GP64 envelope fusion protein. J. Virol. 69:2583-2595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Monsma, S. A., A. G. Oomens, and G. W. Blissard. 1996. The GP64 envelope fusion protein is an essential baculovirus protein required for cell-to-cell transmission of infection. J. Virol. 70:4607-4616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muratani, M., and W. P. Tansey. 2003. How the ubiquitin-proteasome system controls transcription. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 4:192-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Olszewski, J., and L. K. Miller. 1997. Identification and characterization of a baculovirus structural protein, VP1054, required for nucleocapsid formation. J. Virol. 71:5040-5050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Olszewski, J., and L. K. Miller. 1997. A role for baculovirus GP41 in budded virus production. Virology 233:292-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oomens, A. G., and G. W. Blissard. 1999. Requirement for GP64 to drive efficient budding of Autographa californica multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus. Virology 254:297-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Patnaik, A., V. Chau, and J. W. Wills. 2000. Ubiquitin is part of the retrovirus budding machinery. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:13069-13074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pearson, M. N., R. L. Russell, G. F. Rohrmann, and G. S. Beaudreau. 1988. p39, a major baculovirus structural protein: immunocytochemical characterization and genetic location. Virology 167:407-413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pornillos, O., J. E. Garrus, and W. I. Sundquist. 2002. Mechanisms of enveloped RNA virus budding. Trends Cell Biol. 12:569-579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reilly, L. M., and L. A. Guarino. 1996. The viral ubiquitin gene of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus is not essential for viral replication. Virology 218:243-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ross, L., and L. A. Guarino. 1997. Cycloheximide inhibition of delayed early gene expression in baculovirus-infected cells. Virology 232:105-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schubert, U., D. E. Ott, E. N. Chertova, R. Welker, U. Tessmer, M. F. Princiotta, J. R. Bennink, H. G. Krausslich, and J. W. Yewdell. 2000. Proteasome inhibition interferes with gag polyprotein processing, release, and maturation of HIV-1 and HIV-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:13057-13062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Strack, B., A. Calistri, M. A. Accola, G. Palu, and H. G. Gottlinger. 2000. A role for ubiquitin ligase recruitment in retrovirus release. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:13063-13068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Theilmann, D. A., and S. Stewart. 1991. Identification and characterization of the IE-1 gene of Orgyia pseudotsugata multicapsid nuclear polyhedrosis virus. Virology 180:492-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Theilmann, D. A., L. G. Willis, B. J. Bosch, I. J. Forsythe, and Q. Li. 2001. The baculovirus transcriptional transactivator ie0 produces multiple products by internal initiation of translation. Virology 290:211-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Volkman, L. E. 1986. The 64K envelope protein of budded Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 131:103-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Volkman, L. E., P. A. Goldsmith, R. T. Hess, and P. Faulkner. 1984. Neutralization of budded Autographa californica NPV by a monoclonal antibody: identification of the target antigen. Virology 133:354-362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Volkman, L. E., and M. D. Summers. 1977. Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus: comparative infectivity of the occluded, alkali-liberated, and nonoccluded forms. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 30:102-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Volkman, L. E., M. D. Summers, and C. H. Hsieh. 1976. Occluded and nonoccluded nuclear polyhedrosis virus grown in Trichoplusia ni: comparative neutralization comparative infectivity, and in vitro growth studies. J. Virol. 19:820-832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Whitford, M., and P. Faulkner. 1992. Nucleotide sequence and transcriptional analysis of a gene encoding gp41, a structural glycoprotein of the baculovirus Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. J. Virol. 66:4763-4768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Whitford, M., and P. Faulkner. 1992. A structural polypeptide of the baculovirus Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus contains O-linked N-acetylglucosamine. J. Virol. 66:3324-3329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Williams, G. V., and P. Faulkner. 1997. Cytological changes and viral morphogenesis during baculovirus infection, p. 61-108. In L. K. Miller (ed.), Baculovirus. Plenum Publishing Corporation, New York, N.Y.

- 61.Yang, S., and L. K. Miller. 1998. Control of baculovirus polyhedrin gene expression by very late factor 1. Virology 248:131-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang, S., and L. K. Miller. 1998. Expression and mutational analysis of the baculovirus very late factor 1 (vlf-1) gene. Virology 245:99-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]