Abstract

Influenza A/H3N2 viruses have developed an increased number of glycosylation sites on the globular head of the hemagglutinin (HA) protein since their appearance in 1968. Here, the effect of addition of oligosaccharide chains to the HA of A/H3N2 viruses on its biological activities was investigated. We constructed seven mutant HAs of A/Aichi/2/68 virus with one to six glycosylation sites on the globular head, as found in natural isolates, by site-directed mutagenesis and analyzed their intracellular transport, receptor binding, and cell fusion activities. The glycosylation sites of mutant HAs correspond to representative A/H3N2 isolates (A/Victoria/3/75, A/Memphis/6/86, or A/Sydney/5/97). The results showed that all the mutant HAs were transported to the cell surface as efficiently as wild-type HA. Although mutant HAs containing three to six glycosylation sites decreased receptor binding activity, their cell fusion activity was not affected. The reactivity of mutant HAs having four to six glycosylation sites with human sera collected in 1976 was much lower than that of wild-type HA. Thus, the addition of new oligosaccharides to the globular head of the HA of A/H3N2 viruses may have provided the virus with an ability to evade antibody pressures by changing antigenicity without an unacceptable defect in biological activity.

The hemagglutinin (HA) of influenza A virus is a homotrimeric glycoprotein with an ectodomain composed of a globular head and stem region (26). Both regions carry N-linked oligosaccharide chains. The appearance or disappearance of oligosaccharides on the globular head has been reported to occur naturally during antigenic drift of influenza A/H3N2 viruses from 1968 to 1975 (15, 24, 25). The acquisition of new oligosaccharides is an important mechanism underlying the antigenic drift of HA. Antigenic drift occurs by accumulation of a series of point mutations resulting in amino acid substitutions in antigenic sites on the surface of the HA (1, 25). These substitutions prevent neutralization by antibodies directed against previous epidemic strains.

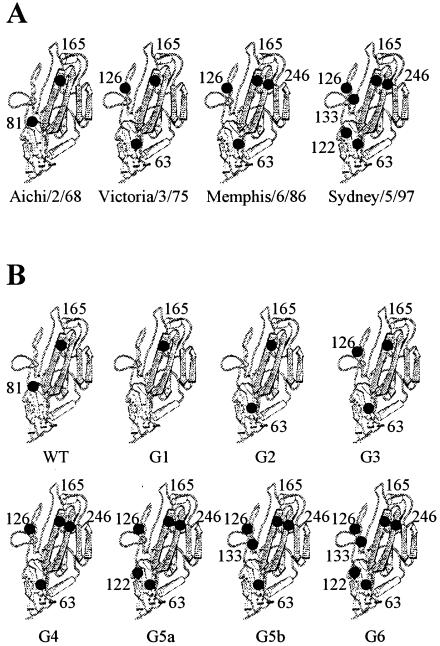

Based on analysis of the HA sequences of A/H3N2 viruses isolated from 1968 to 2002, the oligosaccharide chains on the globular head show large variations in number among different A/H3N2 isolates, although five glycosylation sites at Asn residues 8, 22, 38, 285, and 483 on the stem region are strictly conserved. Most of the A/H3N2 viruses that circulated between 1968 and 1974 (represented by A/Aichi/2/68) had only two oligosaccharides at residues 81 and 165 on the globular head of the HA (Fig. 1A). However, viruses isolated in 1975 (represented by A/Victoria/3/75) had lost a glycosylation site at residue 81 and gained two new sites at residues 63 and 126. The 1986 isolates (represented by A/Memphis/6/86) had acquired a new carbohydrate attachment site at residue 246, and the 1997 isolates (represented by A/Sydney/5/97) had obtained two additional sites at residues 122 and 133. Some recent isolates (represented by A/Panama/2007/99) had often obtained a novel site at residue 144. Thus, the A/H3N2 viruses recently circulating have six or seven glycosylation sites on the globular head of the HA, although whether these are glycosylated is not known. Moreover, the HAs of influenza A/H1N1 viruses and influenza B viruses isolated recently also possess several oligosaccharide chains on their globular head. These observations suggest that the addition of new oligosaccharides to the globular head of the HA may provide influenza viruses with an increased ability to prevail among humans (14). Interestingly, however, examination of the available HA sequences of influenza A/H2N2 viruses showed that none of the HAs had obtained a new glycosylation site on the globular head, and they had only one carbohydrate chain at position 169 (21).

FIG. 1.

Schematic drawing of the globular head of influenza A/H3N2 virus HA, showing the change in N-glycosylation sites among representative isolates (A) and the mutant HAs used in this study (B). N-glycosylation sites are indicated by solid circles. Numbers indicate Asn residues in the first position of the glycosylation sequon.

We previously studied the antigenic structure of the HA of A/H2N2 virus and revealed that most of the escape mutants selected by monoclonal antibodies had acquired a new glycosylation site at position 131, 160, or 187 on the tip of the HA (21, 22, 23). The results indicated that A/H2N2 viruses have the potential to gain at least one additional oligosaccharide on the globular head of the HA, although this has never occurred during 11 years of its circulation in humans. We constructed HA glycosylation site mutants containing one to three oligosaccharides at positions 131, 160, and 187 by site-directed mutagenesis and investigated the effect of addition of new oligosaccharide chains to the globular head of H2 HA on their biological activities (22). The results showed that all of the mutant HAs were transported to the cell surface but exhibited a decrease in both receptor binding and cell fusion activities. Thus, we postulated that A/H2N2 viruses may have failed to increase the number of oligosaccharides on the HA because, if this happens, the biological activities of the HA are reduced, presumably decreasing the ability of the virus to replicate in humans.

There are several lines of evidence indicating that the number, structure, and location of the oligosaccharide chains modulate the antigenicity of the HA by masking the protein surface and that the addition of carbohydrate is more effective than a single amino acid substitution in changing the antigenic properties of the HA (2, 14, 16, 21). The failure of A/H2N2 viruses to employ this effective strategy for evading immune pressures might be one of the causes for their short survival time in humans (22).

Several studies have been carried out to analyze the effect of oligosaccharides on the properties of H3 HA. Gallagher et al. (3) reported that the addition of oligosaccharide chains at novel sites located on areas of the surface of the HA that are not normally shielded by carbohydrate affected the folding, transport, and biological activities of the molecule. However, the effect of addition of glycosylation sites, found in natural isolates during antigenic drift in A/H3N2 viruses, has never been investigated. In the present study, we constructed seven mutant HAs of A/Aichi/2/68 (H3N2) virus having one to six glycosylation sites on the globular head and expressed them in COS-1 cells. Mutant HAs with glycosylation sites as found on the HA of representative A/H3N2 isolates (A/Victoria/3/75, A/Memphis/6/86, and A/Sydney/5/97) and their intracellular transport and biological activities were analyzed. We also investigated the reactivity of mutant HAs with human sera to study whether the addition of oligosaccharide chains to the HA of A/H3N2 virus affects their antigenicity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viruses and cells.

The A/Aichi/2/68, A/Victoria/3/75, and A/Sydney/5/97 strains of influenza A/H3N2 virus were grown in the allantoic cavities of 10-day-old embryonated hen's eggs. COS-1 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum.

Antibodies.

Rabbit antiserum against egg-grown A/Aichi/2/68 virions was prepared as described previously (27). Human sera were collected in 1976 from donors who were born between 1953 and 1955 and stored at −20°C until assay.

Plasmid construction and site-directed mutagenesis.

The wild-type HA gene cDNA of A/Aichi/2/68 virus in a transient expression vector, pME18S (19) (pMEHA), was generously provided by K. Nakajima (Nagoya City University, Japan) (10). Mutant HA gene cDNAs encoding one to six N-glycosylation sites were generated by site-directed mutagenic PCR with mutant primers (sequences are available upon request), with pMEHA as a template (Fig. 1B). Mutant oligonucleotide primers were designed as the same consensus sequence for N-glycosylation as found in natural isolates A/Victoria/3/75, A/Memphis/6/86, and A/Sydney/5/97. The Thr at position 83 was replaced with Lys to eliminate a glycosylation site at position 81. The Asp, Thr, Asn, and Gly at positions 63, 126, 135, and 248 were changed into Asn, Asn, Thr, and Thr, respectively, to create a carbohydrate addition site at positions 63, 126, 133, and 246, respectively. Moreover, the Thr and Gly at positions 122 and 124 were replaced by Asn and Ser, respectively, to create a glycosylation site at position 122.

The PCR products were excised by digestion with BclI and XhoI, and the resulting DNA fragments were subcloned into the BclI and XhoI sites of pMEHA. Each mutant HA was generated with the previous one as a template. G3, G4, and G6 had the same consensus sequences for glycosylation as the natural isolates A/Victoria/3/75, A/Memphis/6/86, and A/Sydney/5/97, respectively. The nucleotide sequences of all mutant cDNAs in pME18S plasmids were confirmed by cycle sequencing with the BigDye terminator cycle sequencing FS ready reaction kit (Applied Biosystems) and an ABI Prism 310 automatic sequencer (Applied Biosystems).

Transfection, radioisotopic labeling, and immunoprecipitation.

Subconfluent monolayers of COS-1 cells in 3.5-cm petri dishes were transfected with 1 μg of the recombinant pME18S plasmid containing a wild-type or mutant HA gene with Lipofectamine Plus (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. At 48 h posttransfection, cells were labeled for 15 min with 10 μCi of [35S]methionine (ARC) per ml in methionine-deficient DMEM. Cells were then disrupted in 0.01 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) containing 1% Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 0.15 M NaCl, and a cocktail of protease inhibitors (5) and immunoprecipitated as described previously (17) with rabbit antiviral serum or human serum. The immunoprecipitates obtained were analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) on 13% gels (unless otherwise noted) containing 4 M urea under reducing conditions.

Endoglycosidase H digestion.

Transfected COS-1 cells were labeled with [35S]methionine for 20 min at 48 h posttransfection and chased for 4 h in DMEM containing 1 mM nonradioactive methionine. Cells were then immunoprecipitated with rabbit antiviral serum, and the immunoprecipitated proteins were digested with endoglycosidase H (30 mU) for 16 h at 37°C under the conditions described previously (5), precipitated with acetone, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

Trypsin treatment of transfected cells.

At 48 h posttransfection, transfected COS-1 cells were labeled with [35S]methionine for 20 min and chased for 4 h. During the last 15 min of the chase, cells were treated with DMEM containing 5 μg of tosylsulfonyl phenylalanyl chloromethyl ketone (TPCK)-trypsin per ml, and the reaction was terminated by addition of soybean trypsin inhibitor. Cells were then immunoprecipitated with rabbit antiviral serum, and the resulting immunoprecipitates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE on 17.5% gels.

Hemadsorption test.

Transfected COS-1 cells were washed once with DMEM at 48 h posttransfection, followed by incubation with 5 mU of Arthrobacter ureafaciens neuraminidase per ml (Roche Diagnostics) at 37°C for 1 h. Cells were then washed three times with DMEM and incubated at room temperature for 10 min with a 1% suspension of guinea pig erythrocytes or a 0.5% suspension of chicken erythrocytes. The monolayers were then washed several times with phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) lacking Ca2+ and Mg2+ and examined by phase contrast microscopy. For quantification of the extent of hemadsorption, erythrocytes were lysed in 1 ml of distilled water. After removal of cellular debris by low-speed centrifugation, the released hemoglobin in the supernatant was measured by reading the absorption at 540 nm.

Cell fusion assay.

At 48 h posttransfection, transfected COS-1 cells were treated with 5 μg of TPCK-trypsin per ml in DMEM for 15 min at 37°C and then exposed to the warm fusion medium (phosphate-buffered saline with 10 mM morpholineethanesulfonic acid and 10 mM HEPES adjusted to pH 5.0) for 5 min. The fusion medium was then replaced with neutral DMEM containing 10% fetal calf serum, and the cells were incubated at 37°C for 3 h. The cells were then fixed with methanol and stained with Giemsa solution.

RESULTS

Expression of mutant HAs with one to six glycosylation sites on the globular head.

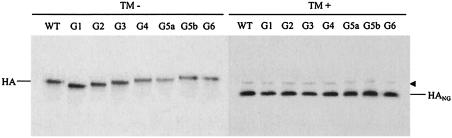

To determine whether the newly introduced glycosylation sites were used, COS-1 cells were transfected with the wild-type or one of the seven mutant HA genes and labeled with [35S]methionine in the presence or absence of 1 μg of tunicamycin , a specific inhibitor of N-linked glycosylation, per ml (18). Cells were then immunoprecipitated with rabbit antiserum against A/Aichi/2/68 virus, and the resulting precipitates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 2). All mutant HAs synthesized in the presence of tunicamycin exhibited the same mobility as nonglycosylated wild-type HA. G1 showed increased electrophoretic mobility compared with wild-type HA when protein synthesized in the absence of tunicamycin was analyzed, suggesting that Asn residue 81 of wild-type HA was used for glycosylation. G2, G3, and G4 displayed gradually reduced mobility in the same degree, suggesting that the novel glycosylation sites introduced into positions 63, 126, and 246 were used. By contrast, the electrophoretic mobility of G5a was indistinguishable from that of G4, which suggests that one of the glycosylation sites of G5a was not used. G5b migrated slightly more slowly than G4 and G5a, suggesting that Asn residue 133 was glycosylated. The same mobility of G5b and G6 suggested that one of the glycosylation sites of G6 was not used, as in G5a. Thus, it is reasonable to conclude that G1, G2, G3, G4, G5a, G5b, and G6 have one, two, three, four, four, five, and five oligosaccharide chains on the globular head of the HA, respectively (Table 1).

FIG. 2.

Expression of mutant HAs. COS-1 cells transfected with wild-type (WT) or mutated HA gene cDNA were labeled with [35S]methionine for 15 min at 48 h posttransfection in the absence (TM−) or presence (TM+) of tunicamycin. Cells were then immunoprecipitated with antiserum against A/Aichi/2/68 virus, and the resulting immunoprecipitates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. HANG, nonglycosylated HA. The arrowhead indicates the coprecipitated endoplasmic reticulum-resident chaperone binding protein BiP.

TABLE 1.

Biological activities of mutant HAs

| HA | No. of glycosylation sites | No. of oligo- saccharides | Cell surface expressiona | Binding (% of WT)b

|

Cell fusionc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guinea pig erythrocytes | Chicken erythrocytes | |||||

| WT | 2 | 2 | + | 100 | 100 | + |

| G1 | 1 | 1 | + | 111 | 115 | + |

| G2 | 2 | 2 | + | 110 | 99 | + |

| G3 | 3 | 3 | + | 97 | 36 | + |

| G4 | 4 | 4 | + | 25 | 8 | + |

| G5a | 5 | 4 | + | 17 | 4 | + |

| G5b | 5 | 5 | + | 16 | 6 | + |

| G6 | 6 | 5 | + | 11 | 3 | + |

+, efficiency of transport to the cell surface identical to that of wild-type HA.

Released hemoglobin is shown as a percentage of that of wild-type (WT) HA.

+, activity comparable to that of wild-type HA.

Intracellular transport of mutant HAs.

It is accepted that the acquisition of resistance to endoglycosidase H indicates the conversion of carbohydrate chains from the high-mannose type to the complex one that occurs in the medial Golgi cisternae (20). To examine whether the newly introduced oligosaccharide chains had acquired resistance to endoglycosidase H digestion, transfected COS-1 cells were labeled with [35S]methionine for 20 min and chased for 4 h. Cells were then immunoprecipitated with rabbit antiviral serum, and the resulting immunoprecipitates were treated with endoglycosidase H and analyzed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 3A). All of the mutant HAs, like wild-type HA, had acquired endoglycosidase H resistance during a chase, showing that all of the mutant HAs as well as wild-type HA were transported to the medial Golgi cisternae. The endoglycosidase H-resistant form of wild-type HA migrated slightly faster than the undigested protein, suggesting that at least one of the carbohydrate chains of wild-type HA was not converted to the resistant form. The rate and extent of the endoglycosidase H-resistant forms of all mutant HAs were similar to those of wild-type HA. It was previously demonstrated that the carbohydrates attached to Asn residues 165 and 285 of A/Aichi/2/68 and A/Victoria/3/75 virus HAs are not processed and remain of the high-mannose type (15, 26). Our finding is consistent with these reports.

FIG. 3.

Intracellular transport of mutant HAs. COS-1 cells expressing wild-type (WT) or mutant HA were labeled with [35S]methionine for 20 min at 48 h posttransfection and chased for 4 h. (A) Immediately after a pulse (P) or after a subsequent chase (C), cells were immunoprecipitated with antiserum against A/Aichi/2/68 virus. The resulting precipitates were digested (+) or mock digested (−) with endoglycosidase H and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. R and S indicate the endoglycosidase H-resistant and -sensitive forms of HA, respectively. (B) Cells were treated (+) or not (−) with TPCK-trypsin during the last 15 min of the chase and then immunoprecipitated with antiserum against A/Aichi/2/68 virus. The resulting immunoprecipitates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE on 17.5% gels.

To analyze the efficiency of transport of the mutant HAs to the cell surface, COS-1 cells expressing the wild-type or one of the seven mutant HAs were labeled with [35S]methionine for 20 min and chased for 4 h. Cells were treated with TPCK-trypsin during the last 15 min of the chase to cleave the HA proteins expressed on the cell surface and then immunoprecipitated with rabbit antiviral serum. The immunoprecipitates obtained were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Figure 3B shows that, in every mutant HA, the majority of the HA proteins were cleaved into HA1 and HA2 by TPCK-trypsin, indicating that all of the mutant HAs were transported to the cell surface as efficiently as wild-type HA.

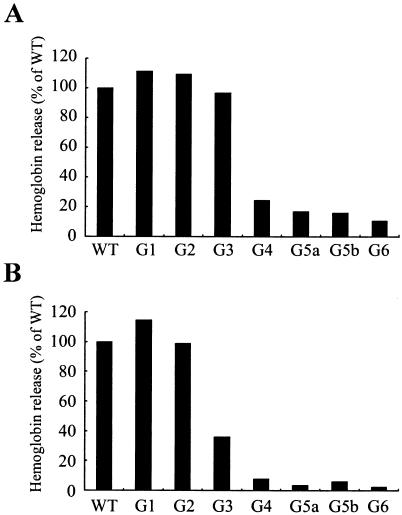

Biological activities of mutant HAs.

In order to investigate the effect of addition of new oligosaccharides to the globular head of H3 HA on its receptor binding activity, COS-1 cells transfected with the wild-type or one of the mutant HA genes were treated with neuraminidase at 48 h posttransfection and examined for hemadsorption according to the procedures described in Materials and Methods. The amounts of wild-type and mutant HAs expressed in transfected cells were determined by measuring the radioactivity of the HA bands after SDS-PAGE of [35S]methionine-labeled cell lysates, and the expression levels of all the mutant HAs were comparable to that of wild-type HA (data not shown). The extent of hemadsorption was enhanced significantly by neuraminidase treatment (data not shown), as has been observed with the HAs of H7, H1, and H2 viruses (11, 22). When the hemadsorption assays were done with guinea pig erythrocytes, little difference was observed in the extent of hemadsorption among wild-type HA from the G1, G2, and G3 mutants (Fig. 4A). When chicken erythrocytes were used for the assays, the hemadsorbing activities of G1 and G2 were similar to that of wild-type HA (Fig. 4B). By contrast, G4, G5a, G5b, and G6 exhibited a significant decrease (3 to 25% of the level with wild-type HA) in the extent of hemadsorption with both types of erythrocytes (Table 1), indicating that mutant HAs containing four to five oligosaccharide chains had drastically decreased receptor binding activity.

FIG. 4.

Receptor binding activity of mutant HAs. COS-1 cells were transfected with cDNA encoding wild-type (WT) or mutant HA protein. At 48 h posttransfection, cells were subjected to hemadsorption with guinea pig erythrocytes (A) or chicken erythrocytes (B). Erythrocytes that attached to the HA-expressing cells were lysed in distilled water, and the amounts of hemoglobin released were measured by reading the absorption at 540 nm and are shown as a percentage of the wild-type HA value.

Next, we compared cell fusion activities between the wild-type and mutant HAs (Fig. 5). Extensive syncytium formation was observed in COS-1 cells expressing any of the mutant HAs as well as wild-type HA. These observations indicated that the cell fusion activity of H3 HA was not affected by the addition of oligosaccharides to the globular head.

FIG. 5.

Cell fusion activity of mutant HAs. COS-1 cells expressing wild-type (WT) or mutant HA were treated with TPCK-trypsin at 48 h posttransfection, exposed to fusion medium (pH 5.0), and then incubated for 3 h in neutral-pH medium. At the end of the incubation period, the cells were stained with Giemsa solution.

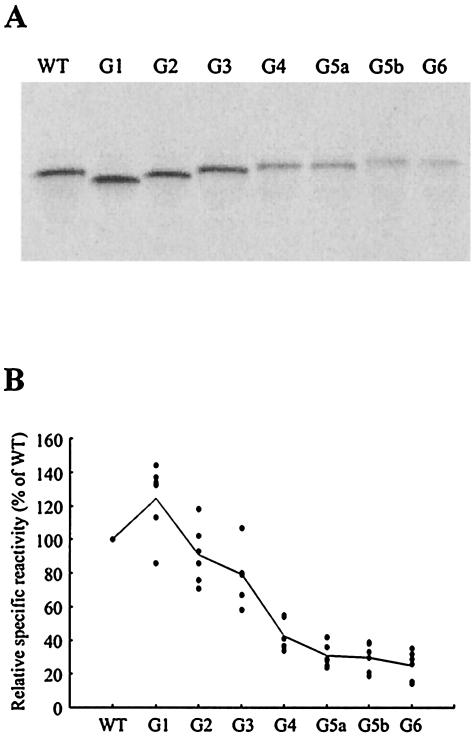

Reactivity of mutant HAs with human sera.

To examine the impact of carbohydrate addition to the globular head of H3 HA on reactivity with human sera, COS-1 cells transfected with the wild-type or one of the seven mutant HA genes were labeled with [35S]methionine and then immunoprecipitated with six human sera collected in 1976 from donors who had been infected with A/Aichi/2/68-like viruses; that is, each of the sera had hemagglutination inhibition titers against A/Aichi/2/68 virus (160 to 640 hemagglutination inhibition units [HIU]/ml) but not against A/Victoria/3/75 (<10 HIU/ml) or A/Sydney/5/97 virus (<10 HIU/ml).

The immunoprecipitates obtained were subjected to SDS-PAGE (Fig. 6A). The expression levels of all the mutant HAs were comparable to that of wild-type HA as described above. The radioactivity of the HA bands after SDS-PAGE of immunoprecipitates was measured, and the values obtained were used to calculate the relative specific reactivity with human sera (Fig. 6B). A representative result with a serum for which the hemagglutination inhibition titer against A/Aichi/2/68 virus was 160 HIU/ml is shown in Fig. 6A. The reactivity of G1 with most of the human sera tested was slightly higher than that of wild-type HA. However, the reactivity of G2 and G3 was slightly lower than that of wild-type HA, and the reactivity of G4, G5a, G5b, and G6 was reduced by 57 to 75% compared with that of wild-type HA. These observations raised the possibility that the addition of four to five oligosaccharide chains considerably affects the antigenicity of the HA molecule.

FIG. 6.

Reactivity of mutant HAs with human sera. COS-1 cells transfected with wild-type (WT) or mutated HA gene cDNA were labeled with [35S]methionine for 15 min at 48 h posttransfection. The cells were then immunoprecipitated separately with six human sera collected in 1976 which had hemagglutination inhibition activity against A/Aichi/2/68 virus (160 HIU/ml) but not against A/Victoria/3/75 virus (<10 HIU/ml) or A/Sydney/5/97 virus (<10 HIU/ml). The immunoprecipitates obtained were subjected to SDS-PAGE (A), and the radioactivity of the HA bands was measured (B). The relative specific reactivity of the mutant HAs was determined as a percentage of that of wild-type HA. The solid line shows the average for the six sera.

DISCUSSION

In order to investigate the effect of addition of oligosaccharide chains to the HA of influenza A/H3N2 viruses on its biological activities, we constructed seven mutant HAs of A/Aichi/2/68 virus having the same glycosylation sites as shown in natural isolates and analyzed their receptor binding and cell fusion activities. The data obtained in the present study are summarized in Table 1. The results showed that the addition of oligosaccharides to the globular head of H3 HA resulted in a decrease in receptor binding activity but not in cell fusion activity. This is consistent with the previous finding that H3 HA which had acquired a novel glycosylation site at position 188 lacked receptor binding activity but retained cell fusion activity (3). Ohuchi et al. (13) demonstrated with H7 HA that deletion of oligosaccharides at positions 123 and 149 caused an increase in receptor binding activity without influencing cell fusion activity. They also reported that removal of oligosaccharide chains (positions 87, 127, 155, and 160) near the receptor binding site of the H1 HA enhanced receptor binding activity but decreased cell fusion activity (12). In contrast to H3, H7, and H1 HAs, we showed previously that the attachment of oligosaccharides at positions 131, 160, and 187 of H2 HA reduced both receptor binding and cell fusion activities (22). This might be a feature unique to H2 HA and may explain why A/H2N2 viruses with carbohydrate chains at these positions did not emerge during circulation in the human population.

We previously investigated the impact of carbohydrate addition to novel sites located on the tip of H2 HA on reactivity with human sera (22). The results indicated that H2 HA with additional oligosaccharides at two or three of positions 131, 160, and 187 displayed markedly decreased reactivity with human sera. In this study, we showed that the addition of oligosaccharide chains to the globular head of H3 HA resulted in a decrease in reactivity with human sera compared with wild-type HA, as was observed with H2 HA. Therefore, the data obtained here suggest that the addition of new oligosaccharides to the globular head of the HA of A/H3N2 viruses affected the antigenicity of the molecule and may have provided the viruses with the ability to evade antibody pressures. The mutant HAs that acquired an additional oligosaccharide chain at Asn residue 246 showed drastically reduced receptor binding activity and reactivity with human sera. These observations raised the possibility that carbohydrate addition to position 246 is critical for the receptor binding activity and antigenicity of the HA of A/H3N2 virus. To confirm this notion, experiments to examine the role of individual oligosaccharide chain are in progress.

Mutant G1 had only one oligosaccharide chain at position 165 on the globular head because the glycosylation site at position 81 was removed. Previously, Gallagher et al. (4) and Nakajima et al. (8) analyzed similar mutant HAs of A/Aichi/2/68 virus which had the same glycosylation sites as in G1. Although the mutated consensus sequences for glycosylation at position 81 were different from each other, all of these mutant HAs were transported to the cell surface and had wild-type receptor binding activity and cell fusion activity. These observations suggest that the removal of an oligosaccharide chain at position 81 does not affect the intracellular transport and biological activities of H3 HA.

Comparison of electrophoretic mobility between the wild-type and mutant HAs showed that four introduced glycosylation sites at Asn residues 63, 126, 133, and 246 were used. G5a and G6 had four (positions 63, 126, 246, and 122) and five (positions 63, 126, 133, 246, and 122) introduced sites, respectively. One glycosylation site on each of G5a and G6 was not glycosylated, although it remains unclear which carbohydrate attachment site was not used for glycosylation. The electrophoretic mobility of HA of A/Sydney/5/97 virus, which had the same glycosylation sites as G6, was increased compared with that of G6 when proteins synthesized in the presence of tunicamycin were analyzed (data not shown). However, A/Sydney/5/97 virus HA synthesized in the absence of tunicamycin displayed a slightly slower mobility than G6. Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that, in contrast to G6, all of the glycosylation sites on the HA of A/Sydney/5/97 virus are used.

Since the oligosaccharide attachment sites of G6 were introduced into the HA of A/Aichi/2/68 virus as a template, distortion of the HA structure caused by amino acid substitutions between A/Aichi/2/68 virus and A/Sydney/5/97 virus might have occurred, resulting in the failure of G6 to acquire oligosaccharide chains at all of the potential glycosylation sites. Two carbohydrates at positions 122 and 126 are located close to each other, so that glycosylation at either of these positions may be impossible because of steric hindrance by an oligosaccharide attached to an asparagine in the neighborhood (7, 25).

After the 1992 and 1993 seasons, human influenza A/H3N2 viruses isolated in MDCK cells did not agglutinate chicken erythrocytes but did agglutinate human and goose erythrocytes (10). Nobusawa et al. (10) reported that a change in amino acid residue 190 from Glu to Asp was responsible for this characteristic, as determined in studies with HA cDNA of A/Aichi/51/92 virus. Nakajima et al. (8) demonstrated that an amino acid change from Glu to Asp at residue 190 of A/Aichi/2/68 virus HA did not inhibit its hemadsorbing activity with chicken erythrocytes. Therefore, they suggested that multiple amino acid substitutions on the HA of A/Aichi/2/68 virus are necessary to change the receptor specificity. The present study raised the possibility that the increase in the number of oligosaccharide chains on the globular head of H3 HA might be one of the causes for the failure of recent A/H3N2 viruses to agglutinate chicken erythrocytes. However, our mutant HAs exhibited reduced hemadsorbing activities not only with chicken erythrocytes but also with human, goose, sheep, and turkey erythrocytes (data not shown). Therefore, it seems likely that the inability of recent A/H3N2 viruses to agglutinate chicken erythrocytes might not be related to additional oligosaccharides.

The A/Aichi/2/68 strain, known to preferentially bind to sialic acid in the α2,6Gal linkage rather than the α2,3Gal linkage on erythrocytes, agglutinated chicken, guinea pig, human, and duck erythrocytes (6). Mutant G3 exhibited a decrease in the extent of hemadsorption with chicken erythrocytes (36% of wild-type HA), although its hemadsorbing activity with guinea pig erythrocytes was comparable to that of wild-type HA. These observations suggest that the guinea pig erythrocytes have higher levels of sialic acid in the α2,6Gal linkage than do chicken erythrocytes, which may explain why G3 binds guinea pig erythrocytes better.

Acknowledgments

We thank Katsuhisa Nakajima (Nagoya City University) and Takato Odagiri (National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Japan) for providing influenza A/H3N2 virus strains.

Footnotes

This paper is dedicated to Kiyoto Nakamura, who passed away on 20 October 2001.

REFERENCES

- 1.Both, G. W., M. J. Sleigh, N. J. Cox, and A. P. Kendal. 1983. Antigenic drift in influenza virus H3 hemagglutinin from 1968 to 1980: multiple evolutionary pathways and sequential amino acid changes at key antigenic sites. J. Virol. 48:52-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caton, A. J., G. G. Brownlee, J. W. Yewdell, and W. Gerhard. 1982. The antigenic structure of the influenza virus A/PR/8/34 hemagglutinin (H1 subtype). Cell 31:417-427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gallagher, P., J. Henneberry, I. Wilson, J. Sambrook, and M.-J. Gething. 1988. Addition of carbohydrate side chains at novel sites on influenza virus hemagglutinin can modulate the folding, transport, and activity of the molecule. J. Cell Biol. 107:2059-2073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gallagher, P. J., J. M. Henneberry, J. F. Sambrook, and M.-J. H. Gething. 1992. Glycosylation requirement for intracellular transport and function of the hemagglutinin of influenza virus. J. Virol. 66:7136-7145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hongo, S., K. Sugawara, Y. Muraki, F. Kitame, and K. Nakamura. 1997. Characterization of a second protein (CM2) encoded by RNA segment 6 of influenza C virus. J. Virol. 71:2786-2792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ito, T., Y. Suzuki, L. Mitnaul, A. Vines, H. Kida, and Y. Kawaoka. 1997. Receptor specificity of influenza A viruses correlates with the agglutination of erythrocytes from different animal species. Virology 227:493-499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keil, W., H. Niemann, R. T. Schwarz, and H.-D. Klenk. 1984. Carbohydrates of influenza virus. V. oligosaccharides attached to individual glycosylation sites of the hemagglutinin of fowl plague virus. Virology 133:77-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakajima, K., E. Nobusawa, K. Tonegawa, and S. Nakajima. 2003. Restriction of amino acid change in influenza A virus H3HA: Comparison of amino acid changes observed in nature and in vitro. J. Virol. 77:10088-10098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakajima, S., E. Nobusawa, and K. Nakajima. 2000. Variation in response among individuals to antigenic sites on the HA protein of human influenza virus may be responsible for the emergence of drift strains in the human population. Virology 274:220-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nobusawa, E., H. Ishihara, T. Morishita, K. Sato, and K. Nakajima. 2000. Change in receptor binding specificity of recent human influenza A viruses (H3N2): a single amino acid change in hemagglutinin altered its recognition of sialyloligosaccharides. Virology 278:587-596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohuchi, M., A. Feldmann, R. Ohuchi, and H.-D. Klenk. 1995. Neuraminidase is essential for fowl plague virus hemagglutinin to show hemagglutinating activity. Virology 212:77-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohuchi, M., R. Ohuchi, T. Sakai, and A. Matsumoto. 2002. Tight binding of influenza virus hemagglutinin to its receptor interferes with fusion pore dilation. J. Virol. 76:12405-12413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohuchi, R., M. Ohuchi, W. Garten, and H.-D. Klenk. 1997. Oligosaccharides in the stem region maintain the influenza virus hemagglutinin in the metastable form required for fusion activity. J. Virol. 71:3719-3725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schulze, I. T. 1997. Effects of glycosylation on the properties and functions of influenza virus hemagglutinin. J. Infect. Dis. 176:S24-S28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seidel, W., F. Künkel, B. Geisler, W. Garten, B. Herrmann, L. Döhner, and H.-D. Klenk. 1991. Intraepidemic variants of influenza virus H3 hemagglutinin differing in the number of carbohydrate side chains. Arch. Virol. 120:289-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skehel, J. J., D. J. Stevens, R. S. Daniels, A. R. Douglas, M. Knossow, I. A. Wilson, and D. C. Wiley. 1984. A carbohydrate side chain on hemagglutinins of Hong Kong influenza viruses inhibits recognition by a monoclonal antibody. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81:1779-1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sugawara, K., H. Nishimura, F. Kitame, and K. Nakamura. 1986. Antigenic variation among human strains of influenza C virus detected with monoclonal antibodies to gp88 glycoprotein. Virus Res. 6:27-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takatsuki, A., K. Arima, and G. Tamura. 1971. Tunicamycin, a new antibiotic. I. Isolation and characterization of tunicamycin. J. Antibiot. 24:215-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takebe, Y., M. Seiki, J. Fujisawa, P. Hoy, K. Yokota, K. Arai, M. Yoshida, and N. Arai. 1988. SRα promoter: an efficient and versatile mammalian cDNA expression system composed of the simian virus 40 early promoter and the R-U5 segment of human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 long terminal repeat. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8:466-472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tarentino, A. L., and F. Maley. 1974. Purification and properties of an endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidase from Streptomyces griseus. J. Biol. Chem. 249:811-817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsuchiya, E., K. Sugawara, S. Hongo, Y. Matsuzaki, Y. Muraki, Z.-N. Li, and K. Nakamura. 2001. Antigenic structure of the haemagglutinin of human influenza A/H2N2 virus. J. Gen. Virol. 82:2475-2484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsuchiya, E., K. Sugawara, S. Hongo, Y. Matsuzaki, Y. Muraki, Z.-N. Li, and K. Nakamura. 2002. Effect of addition of new oligosaccharide chains to the globular head of influenza A/H2N2 virus haemagglutinin on the intracellular transport and biological activities of the molecule. J. Gen. Virol. 83:1137-1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsuchiya, E., K. Sugawara, S. Hongo, Y. Matsuzaki, Y. Muraki, and K. Nakamura. 2002. Role of overlapping glycosylation sequons in antigenic properties, intracellular transport and biological activities of influenza A/H2N2 virus haemagglutinin. J. Gen. Virol. 83:3067-3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Verhoeyen, M., R. Fang, W. M. Jou, R. Devos, D. Huylebroeck, E. Saman, and W. Fiers. 1980. Antigenic drift between the haemagglutinin of the Hong Kong influenza strains A/Aichi/2/68 and A/Victoria/3/75. Nature 286:771-776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wiley, D. C., I. A. Wilson, and J. J. Skehel. 1981. Structural identification of the antibody-binding sites of Hong Kong influenza haemagglutinin and their involvement in antigenic variation. Nature 289:373-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilson, I. A., J. J. Skehel, and D. C. Wiley. 1981. Structure of the haemagglutinin membrane glycoprotein of influenza virus at 3 Å resolution. Nature 289:366-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yokota, M., K. Nakamura, K. Sugawara, and M. Homma. 1983. The synthesis of polypeptides in influenza C virus-infected cells. Virology 130:105-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]