Abstract

Herpesvirus saimiri group C strains are capable of transforming human and simian T-lymphocyte populations to permanent antigen-independent growth. Two viral oncoproteins, StpC and Tip, that are encoded by a single bicistronic mRNA, act in concert to mediate this phenotype. A closely related New World monkey herpesvirus, herpesvirus ateles, transcribes a single spliced mRNA at an equivalent genome locus. The encoded protein, Tio, has sequence homologies to both StpC and Tip. We inserted the tio sequence of herpesvirus ateles strain 73 into a recombinant herpesvirus saimiri C488 lacking its own stpC/tip oncogene. Simian as well as human T lymphocytes were growth transformed by the chimeric Tio-expressing viruses. Thus, a single herpesvirus protein appears to be responsible for the oncogenic effects of herpesvirus ateles.

Herpesvirus ateles (ateline herpesvirus type 3) of the genus Rhadinovirus induces lethal T-cell lymphoma in New World monkeys other than its natural host, the spider monkey (Ateles spp.) (21, 28, 44). Continuous T-cell lines have been established from animals infected with herpesvirus ateles. Infection of peripheral lymphocyte cultures in vitro results in permanently growing T-cell populations from cotton-topped, white-lipped, and common marmosets, owl monkeys, or certain rabbits strains (24). Similar oncogenic properties are observed for herpesvirus saimiri (saimiriine herpesvirus type 2), the prototype of the Rhadinovirus family. Variability of a specific genomic locus that corresponds to differences in the oncogenic potential has led to the classification of herpesvirus saimiri isolates into subgroups A, B, and C (15, 43). While oncogenicity in New World primates is common to all subgroups, only group C strains are oncogenic in New Zealand White rabbit strains (12, 42, 48). In addition, only herpesvirus saimiri group C strains induce stable growth of human T lymphocytes in vitro (7). The genes required for oncogenicity map to the variable region of the genome (14, 16, 17, 34, 46) which encodes the saimiri transformation-associated proteins StpA, StpB, and StpC (3, 8, 27, 46). In group C strains, an additional gene product named the tyrosine kinase-interacting protein (Tip) is essential for the transformation of T cells (17, 41). StpC and Tip are encoded by a single bicistronic mRNA (8, 22). We found a new gene termed tio (“two-in-one”) located at a genomic position equivalent to the herpesvirus saimiri oncogenes. Its gene product Tio is encoded by a spliced mRNA, and Tio shares sequence homologies with both StpC and Tip (1). Here, we provide evidence that Tio mediates the transforming phenotype of herpesvirus ateles.

While wild-type herpesvirus ateles is oncogenic in New World primates and efficiently transforms monkey lymphocytes in vitro, it does not transform human lymphocytes. Possible explanations for this may reside in the usage of receptors not present on human lymphocytes, the lower multiplicity of infection that is achievable with the cell-associated growth of herpesvirus ateles, or the restricted transforming functions of the assumed herpesvirus ateles oncoprotein Tio. To address this last aspect, we constructed recombinant viruses in which tio replaces the herpesvirus saimiri C strain oncogene stpC/tip. The resulting chimeric viruses proved to be transformation competent not only in cultured monkey but also in human T cells. This demonstrates that when placed in a herpesvirus saimiri group C background, a single rhadinoviral oncoprotein can mediate growth transformation of human T cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of recombinant viruses.

The herpesvirus saimiri strain C488 genome (15, 20) has been cloned into a set of overlapping cosmid clones (19); recombinant viruses are reconstituted by cotransfection of overlapping cosmids into permissive owl monkey kidney (OMK) cells (13). A 2,046-bp NruI-NaeI fragment from a herpesvirus ateles Tio expression plasmid (2) was cloned into the unique PmeI site of cosmid 331-10, containing the left terminus of the viral genome with the oncogene stpC/tip removed by cleavage with Bst1107I and SwaI, and an artificial linker sequence (5′-GGTACCGGCCGGCCCGGGCGCGCCGTACGTTTAAACTCGAG-3′ [41-bp linker]) was inserted. This gave rise to recombinant viruses M158 and M159, respectively, where either virus has the cytomegalovirus immediate-early (CMVIE) promoter-driven Tio expression cassette in opposite orientation. Alternatively, a genomic fragment of herpesvirus ateles was cloned into cosmid 331GFPΔBst1107I+41bp to achieve recombinant M134, which promotes expression of Tio from its native promoter, including translation of the gene product from its spliced RNA (Fig. 1). In some experiments, CMVIE-driven Tio was recloned into cosmid 331-10 to achieve more independent recombinants, resulting in recombinant virus YYYY (Tio wild type; carries four tyrosine residues), which is identical to M158. Unmodified cosmid 331-10 was used to create Δonc, a recombinant virus deficient of StpC and Tip sequences. Each of the cosmids was analyzed by restriction enzyme analysis and DNA sequencing of the modified regions. Purity of each recombinant virus was confirmed by PCR with primers specific for Tio, StpC/Tip, and ORF03/75 (18) sequences to ensure the presence of an expression cassette, the absence of wild-type oncogene sequences, and genome integrity, respectively. Primers used for the amplification of Tio sequences were 5′-GCAGGAATTCCCATGGCTAACGAGCCACAAGAACACG-3′ and 5′-CTAGGAATTCAGATCTTTTCATTAACAGGAACAGAAAACC-3′.

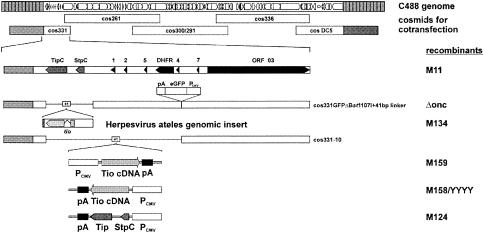

FIG. 1.

Construction of herpesvirus saimiri strain C488 recombinants from overlapping cosmids. The left terminal cosmid (cos) 331 was modified by Bst1107I digestion to delete the oncogene stpC/tip. Cosmid 331-10 resulted from a digest of cosmid 331 with Bst1107I and SwaI to delete stpC/tip, four U-RNA like-genes, and the dihydrofolate reductase gene (DHFR). A 41-bp linker sequence containing unique restriction enzyme recognition sites was inserted to facilitate cloning of a fragment of the herpesvirus ateles genome containing the tio gene or of a fragment carrying a Tio cDNA expression cassette. C488, herpesvirus saimiri strain C488; Tip, tyrosine kinase interacting protein; StpC, saimiri transformation-associated protein of group C; Tio, two-in-one protein; pA, poly(A) signal; PCMV, immediate-early promoter of human cytomegalovirus; eGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein; ORF, open reading frame.

Lymphocyte culture and transformation.

Lymphocyte cultures were maintained in a 1:1 mixture of RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) and Panserin 401 medium supplemented with 10% irradiated fetal calf serum (Pan Biotech, Aidenbach, Germany), glutamine, and antibiotics. Simian peripheral blood lymphocytes of the species Saguinus oedipus were expanded and infected as described previously (32). Human cord blood lymphocytes (CBLs) or adult peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) were obtained by selective sedimentation of erythrocytes for 45 min at 37°C in 5% dextrin (molecular weight, 250,000) in 150 mM NaCl or by Ficoll (Biochrom, Berlin, Germany) density centrifugation. These primary cells were stimulated with 1 μg of phytohemagglutinin/ml, and 10 U of exogenous interleukin-2 (IL-2; Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany)/ml was supplemented after 24 h. On the next day, the cells were infected as described previously (23). Five to seven days after infection, cells were split into two cultures, and exogenous IL-2 was depleted from one of the cultures by centrifugation and washing of the cells. In some experiments, PBLs were infected the day after phytohemagglutinin treatment, but any further exogenous stimuli were omitted. Cell culture densities were determined by automated cell counting (Micro Cell Counter F-300; Sysmex, Norderstedt, Germany; Z2; Beckman-Coulter, Krefeld, Germany).

Detection of viral oncoproteins.

Frozen cells pellets were lysed in TNE buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40) supplemented with 1 mM sodium orthovanadate (Na3VO4), 5 mM NaF (Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany), 10 μg of aprotinin (Sigma-Aldrich)/ml, and 10 μg of leupeptin (Sigma-Aldrich)/ml for 20 min on ice. Lysates were cleared at 14,000 × g for 10 min, and the protein concentration of the supernatants was determined. Equal amounts of total protein were used for each experiment as determined by protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.). Cell lysates were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-8, 9, or 10% polyacrylamide gels and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane filters (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Freiburg, Germany) for immunoblotting. Membrane filters were incubated for 1 h at room temperature in blocking buffer (phosphate-buffered saline [pH 7.4], 0.1% Tween 20, 5% [wt/vol] nonfat dried milk powder) followed by incubation with antiserum or antibody diluted in blocking buffer for 1 h or overnight. After thorough washing in phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20, immunoblots were incubated with secondary antibodies coupled to horseradish peroxidase at dilutions of 1/1,000 to 1/20,000 for 1 h. Bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence, according to the manufacturer's instructions (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Anti-Tio (2), anti-Tip (50), or anti-StpC (22) rabbit antiserum was used at a dilution of 1/5,000. Anti-STAT3 (clone 84) and anti-Grb2 (clone 81) monoclonal antibodies (Transduction Laboratories, Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany) were used at a 1/2,000 dilution. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from Dako (Hamburg, Germany), Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories (Dianova, Hamburg, Germany), and Medac (Hamburg, Germany).

Flow cytometry.

Labeled monoclonal antibodies directed to CD3 (clones SK7 and Leu-4), CD4 (clones SK3 and Leu-3a), CD8 (clones SK1 and Leu-2a), CD25 (clone M-A251), T-cell receptor (TCR) αβ (clone WT31), TCRγδ (clone 11F2), and HLA-DR (clone L243) and labeled isotype controls were obtained from Becton Dickinson. Cultured cells were labeled on ice with antibodies diluted 1/30. Flow cytometry analysis was performed according to standard protocols on a FACScalibur or FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson).

RESULTS

Growth transformation of simian lymphocytes.

In an initial experiment, lymphocytes of the monkey species S. oedipus were infected with recombinant viruses or wild-type herpesvirus saimiri C488 (Fig. 1). Cells were considered growth transformed when uninfected control cells were dead and infected cells could be expanded at exponential growth for at least 3 months. Morphological changes of the monkey T cells were not observed. Cells that were growth transformed with Tio-recombinant viruses grew as well as the wild-type herpesvirus saimiri C488 control or a C488-derived control virus in which transcription of StpC/Tip was driven by the CMVIE promoter. After 6 months of cultivation, the expression of oncogenes was compared between cells grown in either the presence or absence of exogenous IL-2 by Western blot analysis using polyclonal antiserum against Tio or StpC (Fig. 2). All cells were shown to express detectable levels of their respective oncogenes, but no remarkable quantitative differences were seen, confirming viral infection of both IL-2-treated and -untreated cells. This demonstrates that Tio can replace StpC and Tip in herpesvirus saimiri C488 in stable growth transformation of simian T cells in vitro.

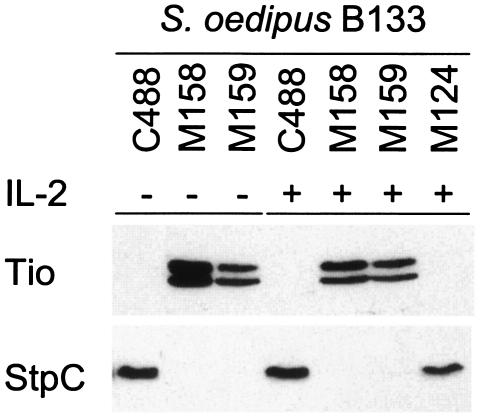

FIG. 2.

Expression of the Tio protein in primary monkey T-cell cultures. Western blot analysis was performed on cell lysates of simian (S. oedipus B133) T cells that were growth transformed with wild-type herpesvirus saimiri (C488), Tio-recombinant viruses (M158/M159), or recombinant herpesvirus saimiri C488 with CMVIE promoter-driven StpC/Tip (M124). Membranes were incubated with either anti-Tio or anti-StpC serum to demonstrate the presence or absence of the respective oncoproteins. Cultivation of T cells with (+) or without (−) exogenous IL-2 is indicated.

Transformation of human CBLs.

One of the unique properties of herpesvirus saimiri C488 is its ability to transform human T cells to permanent growth in vitro (7). Both StpC and Tip were shown to be required for this phenotype (33). We were interested in knowing whether Tio, as a single protein, is capable of replacing StpC and Tip in the human T-cell system. Thus, human CBLs were infected with recombinant viruses M158, YYYY, and M159 and wild-type C488 or cosmid-generated wild-type M11 as the control. As in transformed simian cells, expression of the respective oncoproteins was detectable in the proliferating human cells (Fig. 3A). In addition, we tested recombinant virus M134 where Tio was under control of its native promoter. As expected, protein production was much lower than expression driven by the CMVIE promoter; however, this had no effect on the oncogenic potential of Tio (Fig. 3B and Table 1). Uninfected cell cultures showed signs of massive cell death within 2 weeks, and infected cell cultures were considered to be growth transformed after at least 3 months of continuous cultivation. Further on, the transformed cells were regularly cultured for more than 18 months. Polyclonal cell lines could be generated with all recombinant viruses, even with those carrying Tio driven by its native promoter. In many cases, the generated cell lines were independent of exogenous IL-2, and there was no need for other stimuli such as antigen or irradiated feeder cells (Table 1). Thus, Tio acts as a transforming oncoprotein in growth transformation of human T cells independent of exogenous IL-2.

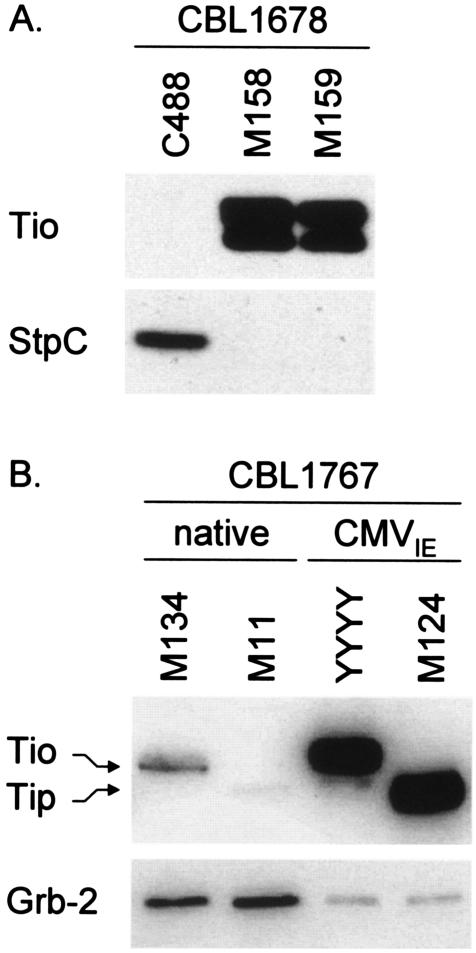

FIG. 3.

(A) Expression of the tio oncogene in transformed human T cells is independent of its genome orientation. Lysates of human CBL 1678 were equalized to total protein concentration, and blotted membranes were incubated with rabbit antisera against Tio and StpC. M158 and M159 represent recombinant viruses with the Tio expression cassette cloned in opposite genome orientation. Herpesvirus saimiri C488-transformed T cells served as a control. (B) Expression levels of Tio in CBL after 18 months of continuous culture utilizing different viral promoters. Western blot analysis was performed on cell lysates of human CBL 1767 that were growth transformed with recombinant virus carrying a genomic fragment of herpesvirus ateles (M134), reconstituted wild-type herpesvirus saimiri C488 (M11), Tio-recombinant virus driven by the CMVIE promoter (YYYY), or CMVIE-driven StpC/Tip virus (M124). The extracted protein of 375,000 cells was applied for native promoter-driven samples; 125,000 cells were lysed for CMVIE-driven samples. Adapter protein Grb-2 was used as a loading control. CBL 1678 and 1767 represent different donors of human CBLs. No IL-2 was added for cultivation of transformed T cells.

TABLE 1.

Success rate of transformation assays with human CBLsa

| Infecting virus | No. of successful transformation assays/total no. of assays

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Without IL-2 | With IL-2 | |

| C488 | 3/11 | 26/33 |

| M11 | 7/11 | 6/7 |

| M124 | 2/4 | 6/13 |

| M134 | 2/6 | 1/17 |

| Tio | 13/23 | 2/45 |

| Δonc | 0/6 | 0/7 |

Data were collected from multiple experiments of CBL infected with different subsets of virus. M11, recombinant wild-type herpesvirus saimiri C488; M124, C488 with CMVIE promoter-driven StpC/Tip; M134, C488 with StpC/Tip replaced by a genomic fragment of herpesvirus ateles encoding Tio; Tio, C488ΔStpCΔTip with CMVIE promoter-driven Tio, the summary of three different recombinants (M158, M159, and YYYY); Δonc, nontransforming C488ΔStpCΔTip.

Immortalization of human PBLs.

The above results could be confirmed in an advanced setting with PBLs of adult humans (Fig. 4). We infected four donor cultures that had not been treated with exogenous IL-2 with the reconstituted wild type (M11) or with Tio-expressing recombinant virus (YYYY). At least 3 out of 4 cultures infected with M11 proliferated for more than 70 days under these conditions (Fig. 4A). All cultures infected with Tio-recombinant virus were still proliferating after more than 20 months and were therefore considered immortalized. The cells expressed the Tio oncoprotein (Fig. 4B) and CD3 as a T-cell marker (Fig. 4D). Surface expression analysis of CD4/CD8 and CD25 revealed differences specific for the virus recombinants used (Fig. 4C and D). While cultures that were growth transformed by M11 virus consisted of CD4- and CD8-single-positive cells mixed at different ratios, the Tio-transformed PBL had a CD4 phenotype. Tio-transformed PBL expressed significantly higher levels of the T-cell activation marker CD25 (Fig. 4C and D), but endogenous IL-2 production was not detectable by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (data not shown). In summary, Tio was able to replace StpC and Tip in all T-cell transformation assays performed in this study with any of the viral recombinants tested. Moreover, the herpesvirus ateles 73 gene product reduced the requirement for exogenous IL-2 usually seen with wild-type herpesvirus saimiri C488-transformed cells, resulting in high efficiency of transformation in the absence of exogenous IL-2.

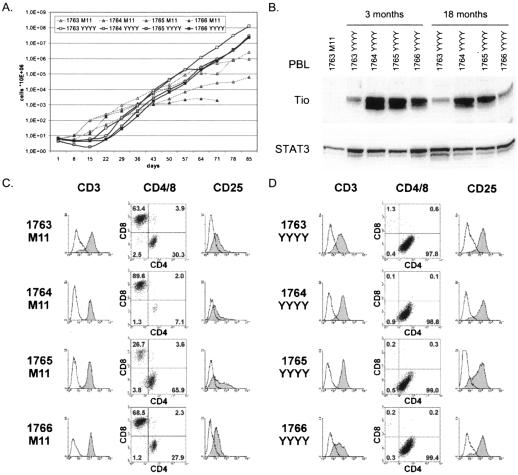

FIG. 4.

IL-2-independent growth of human PBLs from adult donors, which were growth transformed with wild-type herpesvirus saimiri C488 reconstituted from cosmids (1763 M11 to 1766 M11) or with Tio-recombinant virus (1763 YYYY to 1766 YYYY). (A) PBLs were cultivated without the addition of IL-2 or other exogenous stimuli after infection. Uninfected control cells died within 14 to 21 days (data not shown). Cells were counted every 7 days, and total cell numbers were calculated by multiplication with a splitting factor. (B) Comparison of oncogene expression after 3 and 18 months of continuous culture. STAT3 was chosen as an internal loading control; cells that were growth transformed with reconstituted wild-type herpesvirus saimiri C488 (1763 M11) served as negative control for Tio expression. Fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis was performed with monoclonal antibodies against CD3, CD4, CD8, or CD25 on PBLs of four different donors infected with recombinant wild-type herpesvirus saimiri C488 (C) or Tio-recombinant virus (D). Cells were gated for living cells, and the percentage of cells is given in each quadrant of the dot plots.

DISCUSSION

The intriguing property of herpesvirus saimiri C488 is its ability to induce growth transformation of human T cells without the need for further stimulation by an antigen. Initial attempts to transform human lymphocytes by using the closely related herpesvirus ateles were not successful in our laboratory. Here, we investigated the oncogenic potential of Tio by infecting simian and human primary T cells in vitro with recombinant herpesvirus saimiri C488. In these chimeric viruses, the stpC/tip gene was replaced by Tio expression cassettes. While the viral vector backbone lacking StpC and Tip sequences was attenuated, all Tio recombinants efficiently transformed both simian and human lymphocytes. We therefore concluded that the inability to transform human cells with herpesvirus ateles was related to its low infectious titers, its strong cell-associated growth, the usage of different cellular receptors, or restrictions of the viral replication machinery. Reduced transforming functions of Tio were excluded, as it proved to be at least as potent as StpC and Tip in our assay system.

Tio-recombinant viruses were used in a total of 13 in vitro growth transformation assays, including 12 in which the primary cells were of human origin, which regularly resulted in the outgrowth of CD3-positive-T-lymphocyte lines. The expression of Tio under the control of the CMVIE promoter appeared to be more efficient than the expression under the control of the endogenous viral sequences. This observation is in agreement with the levels of Tio protein in the transformed cells. However, this had no effect on transformation capabilities of Tio (Fig. 3B and Table 1). Long-term cultivation experiments are still successfully ongoing after more than 1 1/2 years. All continuously growing cell cultures are independent of exogenous IL-2 or stimulation by mitogen or antigen. CBL-derived cell lines represented a mixture of CD4+, CD8+, or CD4+ CD8+ cells, while infection of adult PBLs preferentially created cultures of CD4+ T cells. The reason for this variability in coreceptor expression is not known, but it may be linked to the addition of exogenous IL-2 during the initial expansion of the primary cells. Nevertheless, the more homogenous phenotype of the IL-2-independent PBL lines makes them a possibly interesting tool to study human immunodeficiency virus replication (47). Although herpesvirus saimiri C488 has been shown to induce T-cell lymphoma in a few cases after infection of rhesus monkeys with high virus doses (4, 31), the reinfusion of autologous herpesvirus saimiri-transformed T cells was tolerated in the same species and not associated with lymphoproliferative disease (31). In analogy, Tio-recombinant viruses could serve as T-cell vectors in adoptive immune transfer, provided that the biosafety of T cells transformed with these viruses is confirmed experimentally.

The numerous transformation assays clearly demonstrated that Tio is able to replace the oncogenic function of StpC and Tip in monkey and human T cells and established Tio as an oncoprotein of herpesvirus ateles. The functional similarity of Tio with StpC and Tip is in accordance with previously published sequence and protein interaction data (1, 2). StpC is known to associate with cellular Ras, and transforming Ras has been shown to be able to replace StpC in transformation assays with herpesvirus saimiri recombinants (25, 29). The interaction of StpC with TRAFs, which leads to NF-κB activation, has been shown to be essential for transformation of human T cells (37). The oncogenic properties of StpC, which have been documented by transformation of rodent fibroblasts and by induction of epithelial tumors in transgenic mice, do not appear to be T-cell specific (30, 45). In contrast, Tip is lethal in early embryonic stages of transgenic mice but induces a lymphoma-like disease in mice when its expression is turned on only after birth (50). Tip is known to interact primarily with Lck (9), the major T-cell nonreceptor tyrosine kinase. Lck phosphorylates the Tip molecule, which in turn appears to recruit STAT transcription factors for phosphorylation by Lck (26, 39, 40). Phosphorylation of STAT3 on tyrosine residue 705 was identified as a hallmark of herpesvirus saimiri C488-transformed lymphocytes (49). Tio compares to Tip in terms of Src family kinase interaction (2), and the IL-2-independent and CD25-positive phenotype of the Tio-expressing lymphocytes also suggests an effect of Tio on STAT activity. Although we found restricted sequence homologies to StpC in the amino terminus of Tio, nothing is known about a Tio function related to StpC. We observed that the addition of IL-2 had an adverse effect on the T-cell transformation of PBLs by Tio-recombinant virus. Though not yet supported by experimental data, the enhanced expression of the Tio protein driven by the human cytomegalovirus promoter might account for this phenomenon. An additional proliferation signal by exogenous IL-2 could result in lethal overstimulation in the presence of high amounts of this oncoprotein in transformed PBLs. This could be mediated at least in part by the high CD25/IL2Rα expression levels expressed on these cells. The prolonged growth and the pronounced IL-2 independence of Tio-expressing cells (compared to those transformed by reconstituted wild-type C488) suggest that Tio-dependent transformation could be more robust and might affect additional regulatory pathways.

This study shows that Tio as a single molecule can replace the two herpesvirus saimiri oncoproteins StpC and Tip in simian and human T-cell transformation, justifying its designation as a two-in-one oncoprotein. In the future, this finding may be substantiated in vivo by infection of susceptible primates or by transgenic studies (35, 50). Specific mutants will help to analyze the role of interacting cellular proteins and posttranslational modifications for the signal-transducing and transforming properties of Tio. The cell lines established here gave us a tool at hand to investigate T-cell growth driven by viral oncogenes and to observe crucial changes and differences in T-cell physiology. They may help to elucidate the emerging roles of STAT factors (6, 10, 38) and NF-κB (5, 11, 36) in development and maintenance of T-cell proliferative disorders. Comparing such cells to primary stimulated or unstimulated primary T cells or tumor-derived human T-cell lines may hint at mechanisms contributing to the multiple steps of T-cell leukemia and lymphoma induction in humans.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 466, TP B2, and C8), the BMBF (Interdisziplinäres Zentrum für Klinische Forschung, 01 KS 9601, TP C4), the Wilhelm Sander-Stiftung (2002.033.1), and the German-Israeli Foundation (674/2000).

REFERENCES

- 1.Albrecht, J.-C. 2000. Primary structure of the Herpesvirus ateles genome. J. Virol. 74:1033-1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albrecht, J.-C., U. Friedrich, C. Kardinal, J. Koehn, B. Fleckenstein, S. M. Feller, and B. Biesinger. 1999. Herpesvirus ateles gene product Tio interacts with nonreceptor protein tyrosine kinases. J. Virol. 73:4631-4639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albrecht, J. C., J. Nicholas, D. Biller, K. R. Cameron, B. Biesinger, C. Newman, S. Wittmann, M. A. Craxton, H. Coleman, and B. Fleckenstein. 1992. Primary structure of the herpesvirus saimiri genome. J. Virol. 66:5047-5058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alexander, L., Z. Du, M. Rosenzweig, J. U. Jung, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1997. A role for natural simian immunodeficiency virus and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef alleles in lymphocyte activation. J. Virol. 71:6094-6099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baldwin, A. S. 2001. Control of oncogenesis and cancer therapy resistance by the transcription factor NF-kappaB. J. Clin. Investig. 107:241-246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benekli, M., M. R. Baer, H. Baumann, and M. Wetzler. 2003. Signal transducer and activator of transcription proteins in leukemias. Blood 101:2940-2954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biesinger, B., I. Muller-Fleckenstein, B. Simmer, G. Lang, S. Wittmann, E. Platzer, R. C. Desrosiers, and B. Fleckenstein. 1992. Stable growth transformation of human T lymphocytes by herpesvirus saimiri. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:3116-3119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biesinger, B., J. J. Trimble, R. C. Desrosiers, and B. Fleckenstein. 1990. The divergence between two oncogenic Herpesvirus saimiri strains in a genomic region related to the transforming phenotype. Virology 176:505-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biesinger, B., A. Y. Tsygankov, H. Fickenscher, F. Emmrich, B. Fleckenstein, J. B. Bolen, and B. M. Broker. 1995. The product of the Herpesvirus saimiri open reading frame 1 (Tip) interacts with T cell-specific kinase p56lck in transformed cells. J. Biol. Chem. 270:4729-4734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bowman, T., R. Garcia, J. Turkson, and R. Jove. 2000. STATs in oncogenesis. Oncogene 19:2474-2488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen, F., V. Castranova, and X. Shi. 2001. New insights into the role of nuclear factor-kappaB in cell growth regulation. Am. J. Pathol. 159:387-397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daniel, M. D., R. D. Hunt, D. DuBose, D. Silva, and L. V. Melendez. 1975. Induction of herpesvirus saimiri lymphoma in New Zealand White rabbits inoculated intravenously. IARC Sci. Publ. 11:205-208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daniel, M. D., L. V. Melendez, R. D. Hunt, N. W. King, M. Anver, C. E. Fraser, H. Barahona, and R. B. Baggs. 1974. Herpesvirus saimiri. VII. Induction of malignant lymphoma in New Zealand White rabbits. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 53:1803-1807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Desrosiers, R. C., A. Bakker, J. Kamine, L. A. Falk, R. D. Hunt, and N. W. King. 1985. A region of the Herpesvirus saimiri genome required for oncogenicity. Science 228:184-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Desrosiers, R. C., and L. A. Falk. 1982. Herpesvirus saimiri strain variability. J. Virol. 43:352-356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Desrosiers, R. C., D. P. Silva, L. M. Waldron, and N. L. Letvin. 1986. Nononcogenic deletion mutants of herpesvirus saimiri are defective for in vitro immortalization. J. Virol. 57:701-705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duboise, S. M., J. Guo, S. Czajak, R. C. Desrosiers, and J. U. Jung. 1998. STP and Tip are essential for herpesvirus saimiri oncogenicity. J. Virol. 72:1308-1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ensser, A., D. Glykofrydes, H. Niphuis, E. M. Kuhn, B. Rosenwirth, J. L. Heeney, G. Niedobitek, I. Muller-Fleckenstein, and B. Fleckenstein. 2001. Independence of herpesvirus-induced T cell lymphoma from viral cyclin D homologue. J. Exp. Med. 193:637-642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ensser, A., A. Pfinder, I. Müller-Fleckenstein, and B. Fleckenstein. 1999. The URNA genes of herpesvirus saimiri (strain C488) are dispensable for transformation of human T cells in vitro. J. Virol. 73:10551-10555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ensser, A., M. Thurau, S. Wittmann, and H. Fickenscher. 2003. The genome of herpesvirus saimiri C488 which is capable of transforming human T cells. Virology 314:471-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Falk, L. A., S. M. Nigida, F. Deinhardt, L. G. Wolfe, R. W. Cooper, and J. I. Hernandez-Camacho. 1974. Herpesvirus ateles: properties of an oncogenic herpesvirus isolated from circulating lymphocytes of spider monkeys (Ateles sp.). Int. J. Cancer 14:473-482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fickenscher, H., B. Biesinger, A. Knappe, S. Wittmann, and B. Fleckenstein. 1996. Regulation of the herpesvirus saimiri oncogene stpC, similar to that of T-cell activation genes, in growth-transformed human T lymphocytes. J. Virol. 70:6012-6019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fickenscher, H., and B. Fleckenstein. 1998. Growth transformation of human T cells. Methods Microbiol. 25:573-602. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fleckenstein, B., and R. C. Desrosiers. 1982. Herpesvirus saimiri and herpesvirus ateles, p. 253-332. In B. Roizman (ed.), The herpesviruses, vol. 1. Plenum Press, New York, N.Y. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guo, J., K. Williams, S. M. Duboise, L. Alexander, R. Veazey, and J. U. Jung. 1998. Substitution of ras for the herpesvirus saimiri STP oncogene in lymphocyte transformation. J. Virol. 72:3698-3704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hartley, D. A., and G. M. Cooper. 2000. Direct binding and activation of STAT transcription factors by the herpesvirus saimiri protein tip. J. Biol. Chem. 275:16925-16932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hor, S., A. Ensser, C. Reiss, K. Ballmer-Hofer, and B. Biesinger. 2001. Herpesvirus saimiri protein StpB associates with cellular Src. J. Gen. Virol. 82:339-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hunt, R. D., L. V. Melendez, F. G. Garcia, and B. F. Trum. 1972. Pathologic features of Herpesvirus ateles lymphoma in cotton-topped marmosets (Saguinus oedipus). J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 49:1631-1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jung, J. U., and R. C. Desrosiers. 1995. Association of the viral oncoprotein STP-C488 with cellular ras. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:6506-6512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jung, J. U., J. J. Trimble, N. W. King, B. Biesinger, B. W. Fleckenstein, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1991. Identification of transforming genes of subgroup A and C strains of Herpesvirus saimiri. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:7051-7055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Knappe, A., G. Feldmann, U. Dittmer, E. Meinl, T. Nisslein, S. Wittmann, K. Matz-Rensing, T. Kirchner, W. Bodemer, and H. Fickenscher. 2000. Herpesvirus saimiri-transformed macaque T cells are tolerated and do not cause lymphoma after autologous reinfusion. Blood 95:3256-3261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knappe, A., C. Hiller, H. Niphuis, F. Fossiez, M. Thurau, S. Wittmann, E. M. Kuhn, S. Lebecque, J. Banchereau, B. Rosenwirth, B. Fleckenstein, J. Heeney, and H. Fickenscher. 1998. The interleukin-17 gene of herpesvirus saimiri. J. Virol. 72:5797-5801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knappe, A., C. Hiller, M. Thurau, S. Wittmann, H. Hofmann, B. Fleckenstein, and H. Fickenscher. 1997. The superantigen-homologous viral immediate-early gene ie14/vsag in herpesvirus saimiri-transformed human T cells. J. Virol. 71:9124-9133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koomey, J. M., C. Mulder, R. L. Burghoff, B. Fleckenstein, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1984. Deletion of DNA sequence in a nononcogenic variant of Herpesvirus saimiri. J. Virol. 50:662-665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kretschmer, C., C. Murphy, B. Biesinger, J. Beckers, H. Fickenscher, T. Kirchner, B. Fleckenstein, and U. Ruther. 1996. A Herpes saimiri oncogene causing peripheral T-cell lymphoma in transgenic mice. Oncogene 12:1609-1616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kucharczak, J., M. J. Simmons, Y. Fan, and C. Gelinas. 2003. To be, or not to be: NF-kappaB is the answer—role of Rel/NF-kappaB in the regulation of apoptosis. Oncogene 22:8961-8982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee, H., J. K. Choi, M. Li, K. Kaye, E. Kieff, and J. U. Jung. 1999. Role of cellular tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factors in NF-κB activation and lymphocyte transformation by herpesvirus saimiri STP. J. Virol. 73:3913-3919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin, T. S., S. Mahajan, and D. A. Frank. 2000. STAT signaling in the pathogenesis and treatment of leukemias. Oncogene 19:2496-2504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lund, T. C., R. Garcia, M. M. Medveczky, R. Jove, and P. G. Medveczky. 1997. Activation of STAT transcription factors by herpesvirus saimiri Tip-484 requires p56lck. J. Virol. 71:6677-6682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lund, T. C., P. C. Prator, M. M. Medveczky, and P. G. Medveczky. 1999. The Lck binding domain of herpesvirus saimiri Tip-484 constitutively activates Lck and STAT3 in T cells. J. Virol. 73:1689-1694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Medveczky, M. M., P. Geck, J. L. Sullivan, D. Serbousek, J. Y. Djeu, and P. G. Medveczky. 1993. IL-2 independent growth and cytotoxicity of herpesvirus saimiri-infected human CD8 cells and involvement of two open reading frame sequences of the virus. Virology 196:402-412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Medveczky, M. M., E. Szomolanyi, R. Hesselton, D. DeGrand, P. Geck, and P. G. Medveczky. 1989. Herpesvirus saimiri strains from three DNA subgroups have different oncogenic potentials in New Zealand White rabbits. J. Virol. 63:3601-3611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Medveczky, P., E. Szomolanyi, R. C. Desrosiers, and C. Mulder. 1984. Classification of herpesvirus saimiri into three groups based on extreme variation in a DNA region required for oncogenicity. J. Virol. 52:938-944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Melendez, L. V., R. D. Hunt, N. W. King, H. H. Barahona, M. D. Daniel, C. E. Fraser, and F. G. Garcia. 1972. Herpesvirus ateles, a new lymphoma virus of monkeys. Nat. New Biol. 235:182-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murphy, C., C. Kretschmer, B. Biesinger, J. Beckers, J. Jung, R. C. Desrosiers, H. K. Muller-Hermelink, B. W. Fleckenstein, and U. Ruther. 1994. Epithelial tumours induced by a herpesvirus oncogene in transgenic mice. Oncogene 9:221-226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murthy, S. C., J. J. Trimble, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1989. Deletion mutants of herpesvirus saimiri define an open reading frame necessary for transformation. J. Virol. 63:3307-3314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nick, S., H. Fickenscher, B. Biesinger, G. Born, G. Jahn, and B. Fleckenstein. 1993. Herpesvirus saimiri transformed human T cell lines: a permissive system for human immunodeficiency viruses. Virology 194:875-877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rangan, S. R., L. N. Martin, F. M. Enright, and W. P. Allen. 1976. Herpesvirus saimiri-induced malignant lymphoma in rabbits. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 57:151-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reiss, C., G. Niedobitek, S. Hor, R. Lisner, U. Friedrich, W. Bodemer, and B. Biesinger. 2002. Peripheral T-cell lymphoma in herpesvirus saimiri-infected tamarins: tumor cell lines reveal subgroup-specific differences. Virology 294:31-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wehner, L. E., N. Schroder, K. Kamino, U. Friedrich, B. Biesinger, and U. Ruther. 2001. Herpesvirus saimiri Tip gene causes T-cell lymphomas in transgenic mice. DNA Cell Biol. 20:81-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]