Abstract

Dendritic cells (DCs) play a crucial role in bridging innate and acquired immune responses to pathogens. In human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection, immature DCs (iDCs) are also main targets for HIV-1 at the mucosal level. In this study, we evaluated the effects of HIV-1-DC interactions on the maturation and functional activity of these cells. Exposure of human monocyte-derived iDCs to either aldrithiol-2-inactivated HIV-1 or gp120 led to an upmodulation of activation markers indicative of functional maturation. Despite their phenotype, these cells retained antigen uptake capacity and showed an impaired ability to secrete cytokines or chemokines and to induce T-cell proliferation. Although gp120 did not interfere with DC differentiation, the capacity of these cells to produce interleukin-12 (IL-12) upon maturation was markedly reduced. Likewise, iDCs stimulated by classical maturation factors in the presence of gp120 lacked allostimulatory capacity and did not produce IL-12, in spite of their phenotype typical of activated DCs. Exogenous addition of IL-12 restores the allostimulatory capacity of gp120-exposed DCs. The finding that gp120 induces abnormal maturation of DCs linked to profound suppression of their activities unravels a novel mechanism by which HIV can lead to immune dysfunction in AIDS patients.

Dendritic cells (DCs) play a pivotal role in linking innate and adaptive immunity by their ability to induce appropriate immune responses upon recognition of invading pathogens. These cells reside in peripheral tissues in an immature state, where they are adapted to capture and accumulate antigens, thus acting like “immunological sensors.” Immature DCs (iDCs) typically respond to pathogen exposure by undergoing considerable morphological and functional changes, collectively called maturation, that occur while they migrate from the peripheral tissues into the draining lymph nodes. Migration of DCs to lymphoid tissues, a process orchestrated by chemotactic signals and tightly regulated expression of the cognate receptors, results in the efficient presentation of optimally processed antigens to T cells. These specialized functions of DCs permit the rapid generation and maintenance of specific immune responses to invading pathogens, largely irrespectively of the access site (21, 28, 33).

The interactions between viruses and DCs have recently gained considerable interest in the context of their possible importance in the pathogenesis of viral infection. Because of their central role in the induction of immune responses, the modulation of DC maturation and functional activity represents a strategic mechanism for a pathogen to evade immune surveillance. In this regard, growing evidence is accumulating on the capacity of some viruses to differently affect DC biology, ultimately leading to an impairment of antiviral immune responses (8, 13, 15, 18, 22, 25, 27, 30, 37, 38).

Recent findings have led to substantial conceptual advances in our understanding of the role of DCs in HIV-1 infection. Human mucosal surfaces (i.e., vaginal, ectocervical, and anal mucosal surfaces) are largely populated by DCs, which are among the first cell targets of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) early in infection (16, 20, 39). Moreover, these cells are the predominant cell type to be infected upon vaginal exposure of macaques to simian immunodeficiency virus (16). The migratory capacity of DCs, together with their ability to recruit large numbers of T cells, identify these cells as strong candidates for a role in the transmission of HIV-1. It is now becoming clear that HIV-1 exploits multiple stages of the intercellular processes responsible for the generation and regulation of the adaptive immune responses to gain access to its main target cell population, the CD4+ T cells (20). Thus, the central role of DCs in stimulating T-cell activation not only provides a route for viral transmission but also represents a vulnerable point at which HIV-1 can interfere with the initiation of primary T-cell immunity.

The present study was designed to evaluate the effect of exposure of human monocyte-derived DCs (MDDCs) to HIV-1 on their differentiation and/or maturation process and functional activities. We show that iDCs, exposed to surface HIV-1 components in the absence of maturation inducing stimuli, exhibit an apparently mature phenotype that does not correlate with the acquisition of functional activities typical of mature DCs (mDCs), such as reduced antigen uptake capacity, interleukin-12 (IL-12), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and CC-chemokine production, and increased allostimulatory activity. Likewise, the addition of recombinant gp120 during the DC maturation process induced by classical stimuli (i.e., lipopolysaccharide [LPS] and CD40L) considerably affects their capacity to produce IL-12 and to induce T-cell proliferation. Although gp120 exposure of monocytes did not interfere with their phenotypic differentiation into DCs, their subsequent maturation induced by classical stimuli was not associated with the enhanced capacity to produce IL-12, typically detected in control mDCs. Exogenous addition of IL-12 restores the allostimulatory capacity of gp120-exposed DCs. On the whole, these results indicate that HIV-1 gp120 can induce an aberrant pattern of DC maturation or activation associated with a profound impairment of functions critically important for DC activities, thus unraveling a novel mechanism by which HIV infection could lead to immune dysfunctions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell separation and culture.

Monocytes were isolated from the peripheral blood of healthy donors as previously described (14). To obtain iDCs, monocytes were cultured at 106 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 medium (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.) containing 10% fetal bovine serum in the presence of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF; 50 ng/ml) and IL-4 (500 U/ml). Cytokines were re-added to the cultures every 3 days. Both cytokines were kindly provided by Schering-Plough (Dardilly, France). In some experiments, monocytes were maintained in the presence of HIV-1 gp120 (2 μg/ml) from the beginning of culture. On day 6, iDCs were induced to final maturation by adding LPS (100 ng/ml; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Mo.) or CD40L (0.1 μg/ml plus 1 μg of enhancer/ml; Alexis Corp., Lausen, Switzerland). Alternatively, iDCs were treated with recombinant HIV-1 gp120 (2 μg/ml) or with AT-2-inactivated virus (multiplicity of infection = 0.1). Some cultures were treated with gp120 and either LPS or CD40L. Cells were harvested and analyzed 48 h later. Cell viability was routinely evaluated by a trypan blue exclusion assay. No significant differences were detected between control and HIV-1-exposed DC cultures.

HIV-1 gp120 proteins.

Recombinant HIV-1 gp120 (strain IIIB) was obtained from the centralized facility for AIDS Reagents supported by the EU Programme EVA/MRC (contract QLKZ-CT-1999-00609) and the United Kingdom Medical Research Council. Recombinant HIV-1 gp120 (strain Ada) was kindly provided by G. Gao. The gp120 was inactivated by boiling the protein for 30 min. The goat antiserum used to neutralize gp120 was raised against a IIIB gp120 (catalog no. 36) and was provided by the National Institutes of Health AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program. A total of 10 μl of the undiluted serum was used to neutralize the activity of 6 μg of gp120. All gp120 preparations used were carefully checked for the presence of bacterial endotoxin by the Limulus amoebocyte assay (detection limit, 0.125 endotoxin unit/ml; Charles River Endosafe, Charleston, S.C.) and found to be endotoxin free.

Virus inactivation procedure.

The HIV-1 Ada and IIIB virus preparations were purchased from ABI (Columbia, Md.) and consisted of pelleted viruses obtained after propagation in primary human macrophages and H9 cells, respectively. For virus inactivation, a 100 mM stock solution of the compound 2,2′-dithiodipyridine (aldrithiol-2 [AT-2]) was prepared and added directly to viral stocks at a final concentration of 1 mM. Virus preparations were treated for 1 h at 37°C and then kept on ice for 2 h. At the end of the inactivating procedure, treatment agent was removed by ultracentrifugation at 17,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C. Viral pellets were resuspended in endotoxin-free Iscove medium containing 15% fetal calf serum.

Flow cytometric analysis of cell surface molecule expression.

Expression of cell surface molecules on DCs was examined by flow cytometric analysis as previously described (14) with the following conjugated monoclonal antibodies: anti-CD83, anti-CD80, anti-CD86, anti-CD40, anti-HLA-DR, and anti-HLA-ABC (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.). Cells were analyzed with a fluorescence-activated cell-sorting (FACS) flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Mountain View, Calif.).

Measurement of antigen uptake.

The capacity of DCs for antigen capture was examined quantitatively by flow cytometric analysis of endocytosis. Briefly, 105 cells were incubated with 0.5 mg of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-dextran for 40 min at 37°C. Cells were washed twice with cold phosphate-buffered saline and then analyzed with a FACS flow cytometer. Staining of cells that had been incubated at 0°C was considered to be the negative control.

Cytokine and chemokine determination.

The levels of IL-12 p70 (detection limit, 5 pg/ml), TNF-α (detection limit, 4.4 pg/ml), and IL-10 (detection limit, 3.9 pg/ml) present in culture supernatants were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, Minn.). CCL3 (detection limit, 3 pg/ml), CCL4 (detection limit, 0.8 pg/ml), and CCL5 (detection limit, 0.2 pg/ml) were measured as previously reported (11) or by multiplex sandwich ELISA (Search Light Human Chemokine Array 1; Pierce Endogen, Rockford, Ill.) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

MLR assay.

The mixed leukocyte reaction (MLR) was performed in RPMI culture medium supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated normal human AB serum. Allogeneic T cells were isolated from the peripheral blood of healthy donors by counterflow centrifugal elutriation and cultured for 5 days in 96-well culture microplates (105/well) as responder cells with different amounts of DCs (1 × 104, 5 × 103, 2 × 103, and 1 × 103) in the presence or in the absence of recombinant human IL-12 (200 ng/ml; PeproTech, London, United Kingdom). [3H]thymidine incorporation (specific activity, 5 Ci/mM; Amersham) was measured after a 16-h pulse with 0.5 μCi/well. The results are shown as the mean counts per minute of triplicate determinations. [3H]thymidine incorporation in negative control wells containing only T cells or DCs was subtracted.

RESULTS

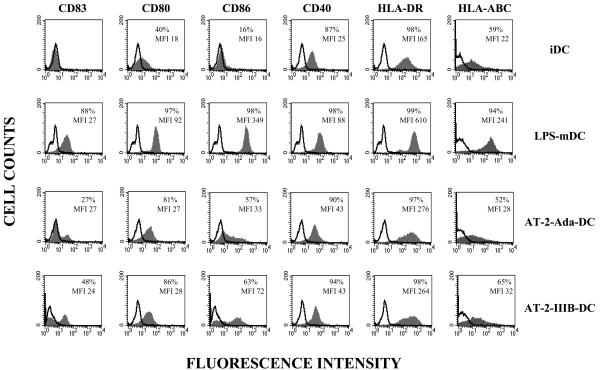

Inactivated HIV-1 and its gp120 protein induce phenotypic changes indicative of DC maturation and/or activation in monocyte-derived iDCs. To investigate whether interaction of iDCs with surface components of HIV-1 could somehow modify their phenotype, human peripheral blood MDDCs were exposed to AT-2-inactivated HIV-1 viruses. In contrast to conventional methods of inactivation (i.e., heat or formalin treatment), this procedure allows viruses to retain conformational and functional integrity of their surface glycoproteins (36). Monocytes were induced to differentiate into DCs in the presence of GM-CSF and IL-4 and subsequently stimulated with inactivated viruses or LPS as a control. Exposure of iDCs to either R5 or X4 AT-2-inactivated HIV-1 strains resulted in the acquisition of a phenotype closely resembling that of mDCs, as assessed by a high expression of costimulatory (i.e., CD80, CD86, and CD40) and HLA class II molecules, as well as by the appearance of the DC maturation marker CD83, with respect to iDCs (Fig. 1). Although the phenotypic changes induced by HIV-1 surface components were somewhat less intense compared to those observed in the presence of LPS, they were consistently detected among different donors. In contrast, the expression of HLA class I molecules, markedly upmodulated upon LPS stimulation, did not change in DCs exposed to inactivated viruses (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Inactivated HIV-1 induces DC phenotypic maturation. iDCs were treated with AT-2 inactivated viruses (strain Ada and IIIB) or with LPS. After 48 h, cells were collected and the expression of cell surface molecules was analyzed by flow cytometry. Open histograms represent background staining of isotype-matched control antibody. Values indicate the percentage of positive cells and the mean fluorescence intensity for each sample. The results from one representative experiment out of four independently performed are shown.

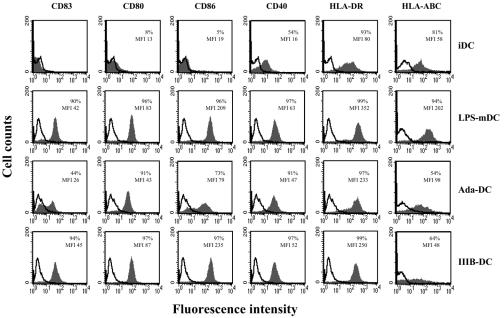

It is well documented that the surface glycoprotein gp120 of HIV-1 profoundly influences immune functions and has direct effects on a variety of cell types (3). Thus, we carried out experiments aimed at evaluating whether the phenotypic changes induced by DC exposure to inactivated viruses could be reproduced by treatment of iDCs with recombinant gp120. Exposure of iDCs to gp120 from either R5 or X4 HIV-1 strains was per se sufficient to induce upmodulation of costimulatory and HLA class II molecules, as well as the appearance of CD83 (Fig. 2). Of note, DCs exposed to recombinant gp120 exhibited a lower expression of HLA class I with respect to iDCs (Fig. 2). The effect of gp120 on DC phenotype was concentration dependent, with the maximal activity at the concentration of 2 μg/ml (Fig. 3A). At a concentration of 1 μg/ml, gp120 was still capable of inducing some significant changes in the DC phenotype, whereas no activity was detected at a concentration of 0.5 μg/ml (Fig. 3A). To exclude the possibility that gp120 could affect DC maturation through a minute LPS contamination, all gp120 preparations used were carefully checked for the presence of bacterial endotoxin by the Limulus amoebocyte assay and found to be endotoxin free (data not shown). Moreover, iDCs were exposed to heat-inactivated gp120, obtained by a procedure known to abolish gp120-induced biologic effects without affecting LPS activity (10). Exposure of iDCs to heat-inactivated R5 or X4 gp120 proteins did not result in any detectable phenotypic change compared to control iDCs (Fig. 3A). As a further control, X4 gp120 was preincubated with an antiserum raised against gp120 prior to its addition to iDC cultures. As shown in Fig. 3B, anti-gp120 antibodies completely inhibited the upmodulation of CD86 and HLA-DR observed in the presence of X4 gp120.

FIG. 2.

HIV-1 gp120 induces DC phenotypic maturation. iDCs were treated with R5 (Ada) or X4 (IIIB) recombinant gp120 or with LPS. After 48 h, cells were collected, and the expression of cell surface molecules was analyzed by flow cytometry. Open histograms represent background staining of isotype-matched control antibody. Values indicate the percentage of positive cells and the mean fluorescence intensity for each sample. The results from one representative experiment out of four independently performed are shown.

FIG. 3.

Specificity and dose dependency of the effect of gp120. (A) iDCs were treated with different concentrations of R5 or X4 gp120, LPS, or boiled gp120 preparations. After 48 h, cells were collected and the expression of cell surface molecule was analyzed by flow cytometry. The histograms report the percentage of positive cells or the mean fluorescence intensity obtained for some phenotypic markers of DCs in the different conditions. The results from one representative experiment out of two independently performed are shown. (B) iDCs were treated with X4 gp120, X4 gp120 preincubated with anti-gp120 antibodies for 30 min at 37°C, or antibodies alone. After 48 h, cells were collected, and the expression of cell surface molecules was analyzed by flow cytometry. The histograms represent the percentage of positive cells or the mean fluorescence intensity obtained for some phenotypic markers of DCs in the different conditions. The results from one representative experiment out of two independently performed are shown.

The phenotypic changes exhibited by DCs exposed to HIV-1 gp120 protein do not correlate with the acquisition of functional activities typical of mature DCs.

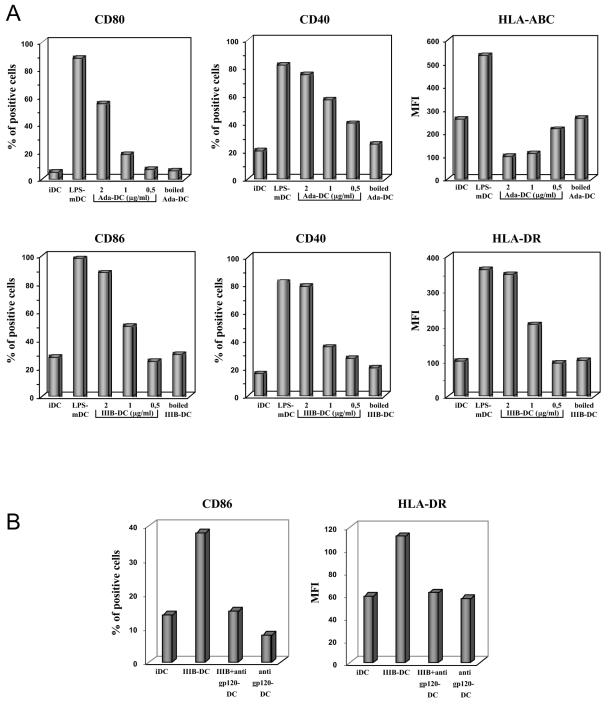

To investigate whether the phenotypic changes indicative of DC maturation paralleled the acquisition of functional activities typical of mDCs, experiments aimed at evaluating antigen uptake capacity, cytokine and chemokine secretion, and the induction of T-cell proliferative responses were performed. The ability of DCs to capture antigens is an important feature of iDCs and is known to decline upon DC maturation (1). The endocytic profile of iDCs was compared to that of DCs matured upon LPS stimulation or exposed to surface viral components. iDCs exhibited a high capacity to uptake fluorescent dextran, but this activity was almost completely lost upon maturation induced by LPS (Fig. 4A). In contrast, DCs exposed to both recombinant gp120 and inactivated viruses retained a high capacity of antigen uptake (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

Effect of HIV-1 surface components on DC functional activities. (A) Antigen uptake capacity. iDCs were treated with AT-2-inactivated viruses, recombinant gp120, or LPS. After 48 h, cells were collected and their capacity to capture FITC-dextran was measured by flow cytometry. Open histograms represent the uptake obtained at 0°C. Values indicate the percentage of cells positive for FITC-dextran. The results from one representative experiment out of three independently performed are shown. (B and C) Cytokine and chemokine production. iDCs were treated with recombinant Ada gp120 or LPS. Supernatants were collected at different time points after treatment and frozen before determination of the cytokine (B) and chemokine (C) levels. The data are the mean values of duplicate samples. The intersample standard deviation did not exceed 10%. (D) Allostimulatory capacity. After 48 h, cells were collected and their capacity to stimulate T-cell proliferation was measured in an MLR assay. The data are the mean values of triplicate samples. The results from one representative experiment out of three independently performed are shown.

To further evaluate the effects of gp120 on DC activation, we compared iDCs, mDCs, and gp120-exposed DCs for their capacity to produce cytokines known to activate immune cells and to induce Th1-type responses (35), IL-10, and CC-chemokines, which are recognized as important mediators of immune responses (31). iDCs did not produce detectable levels of IL-12 and TNF-α, whereas both cytokines were abundantly secreted in the culture medium already after 6 and 12 h of LPS treatment, respectively, and their secretion remained relatively high up to 48 h (Fig. 4B). In contrast, barely detectable levels of IL-12 and TNF-α were observed in DCs exposed to gp120 at all time points assessed (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, no IL-10 secretion was detected in iDCs and in gp120-exposed DCs, whereas LPS-matured DCs secreted very low levels of this cytokine (Fig. 4B). We then analyzed the production of a panel of CC-chemokines, including CCL3, CCL4, and CCL5. iDCs did not produce detectable levels of CCL5, whereas low levels of CCL3 and CCL4 secretion were observed (Fig. 4C). CC-chemokine production was markedly upmodulated in DCs treated with LPS (Fig. 4C). In contrast, iDCs exposed to gp120 failed to upmodulate CCL3 and CCL5 secretion, and only a very modest increase in CCL4 production was detected (Fig. 4C). Although some variability in terms of basal levels of CC-chemokine expression and extent of response to LPS and gp120 was detected among donors, the majority of the donors assessed exhibited a markedly lower responsiveness to gp120 with respect to LPS (<10-fold [data not shown]). Finally, we evaluated the proliferative response of monocyte-depleted peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs) when cocultured with different numbers of allogeneic iDCs, mDCs, or gp120-exposed DCs. As expected, induction of DC maturation upon LPS treatment resulted in a marked increase in the allostimulatory capacity of these cells with respect to iDCs (Fig. 4D). Despite the acquisition of a phenotype indicative of activation or maturation, DCs exposed to gp120 did not exhibit any increase in their allostimulatory capacity (Fig. 4D).

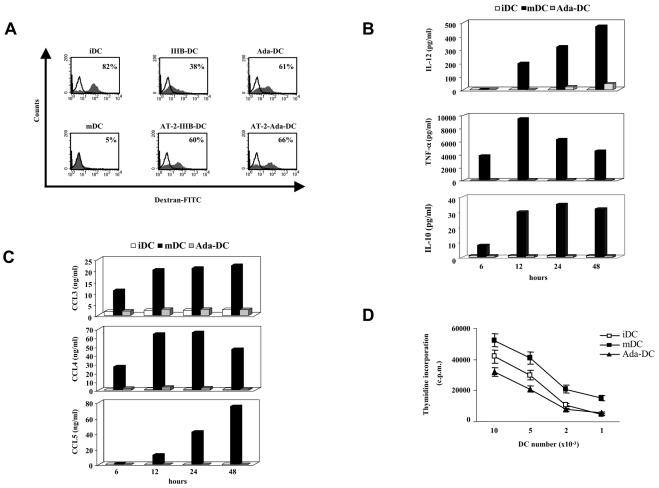

DCs activated by classical stimuli in the presence of gp120 fail to produce IL-12 and exhibit a strongly reduced allostimulatory capacity.

Experiments were then carried out to evaluate whether gp120 could interfere with DCs maturation induced by LPS and CD40L. Despite the fact that DCs stimulated to mature by LPS or CD40L and concomitantly exposed to gp120 exhibited a phenotype identical to their counterparts matured in the absence of gp120 (data not shown), their allostimulatory capacity was strongly reduced with respect to control mDC cultures (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, their reduced ability to stimulate T-cell responses was associated with a dramatic reduction of IL-12 production with respect to control mature DCs exposed to either LPS or CD40L in the absence of gp120 (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

gp120 interferes with functional DC maturation induced by classical stimuli. iDCs were treated with LPS or CD40L in the presence or in the absence of Ada gp120. After 48 h, cells and supernatants were collected. (A) The allostimulatory capacity of the DCs obtained in the different conditions was measured in an MLR assay. The data are the mean values of triplicate samples. (B) The supernatants were tested for the presence of IL-12. The results of one representative experiment out of three independently performed are shown.

DCs generated in the presence of gp120 and subsequently exposed to maturation stimuli do not produce IL-12 and exhibit a low allostimulatory capacity. Experiments carried out to evaluate whether monocyte differentiation into DCs induced by GM-CSF/IL-4 culture was somehow affected by gp120 indicated that this protein did not interfere with the generation of iDCs. In fact, as shown in Fig. 6A, a comparable expression of CD80, CD40, HLA-DR, and HLA-ABC was observed in DCs generated in the presence of gp120 with respect to control cultures. Moreover, these cells were fully competent to undergo phenotypic maturation upon stimulation with LPS or CD40L (Fig. 6A). Of note, the iDCs generated in the presence of gp120 exhibited a basal level of allostimulatory activity that was significantly lower with respect to their counterparts generated in the absence of gp120 (Fig. 6B). However, when these cells were stimulated to mature by LPS or CD40L, their capacity to induce T-cell proliferative responses increased, although to a slightly lower extent with respect to DC cultures generated in the absence of gp120. This effect was more evident with DC cultures induced to mature by CD40L (Fig. 6B). In contrast, a marked decrease in their capacity to produce IL-12 was observed upon maturation induced by both stimuli (Fig. 6C).

FIG. 6.

DCs generated in the presence of gp120 cannot be fully activated. DCs were obtained from monocytes cultured in medium containing GM-CSF/IL-4 in the presence or in the absence of gp120 Ada strain. At day 6 cells were treated with LPS or CD40L. After 48 h cells and supernatants were collected. (A) The expression of cell surface molecules was analyzed by flow cytometry. The histograms represent the percentage of positive cells or the mean fluorescence intensity obtained for some phenotypic markers of DCs in the different conditions. (B) The allostimulatory capacity of the DCs obtained in the different conditions was measured in an MLR assay. The data are the mean values of triplicate samples. (C) The supernatants were tested for the presence of IL-12. The results of one representative experiment out of three independently performed are shown.

Exogenous IL-12 restores the allostimulatory capacity of HIV-1-exposed DCs.

To investigate whether the lack of production of IL-12 observed in gp120-exposed DCs was somehow related to their reduced capacity to stimulate T-cell proliferative responses, experiments were carried out to evaluate the effect of exogenous IL-12 on DC allostimulatory capacity. As shown in Fig. 7, the addition of recombinant IL-12 to DC-T lymphocyte cocultures resulted in a marked increase in the allostimulatory capacity of DCs exposed to gp120 to levels comparable to those observed with LPS-matured DCs.

FIG. 7.

Exogenous IL-12 restores the allostimulatory capacity of HIV-1-exposed DCs. iDCs were treated with recombinant R5 gp120 or LPS. After 48 h, cells were collected, and the allostimulatory capacity of the DCs obtained in the different conditions was measured by an MLR assay in the presence or absence of IL-12. The data are the mean values of triplicate samples. The results of one representative experiment out of three independently performed are shown.

DISCUSSION

We report here for the first time that HIV-1 gp120 protein induces an aberrant pathway of DC maturation, which is associated with a profound impairment of DC functions critically important for the generation of a protective immune response. Interference with DC functions is a common feature of viral pathogenesis and can contribute to the regulation of the life cycle of many viruses (32). This effect is usually achieved by the expression of viral genes and virus replication in mature DCs or their precursors (13, 15, 18, 22, 27, 30, 37, 38). However, reports describing modulation of DC functions in the absence of productive infection or upon exposure to viral soluble factors have also been published (7, 8, 9, 17, 29, 34, 41). For example, infection of DCs with herpes simplex virus, vaccinia virus, human T-cell leukemia virus type 1, and the Ebola and Lassa viruses inhibits their phenotypic and/or functional maturation and interferes with their capacity to activate T lymphocytes (8, 25, 27, 37). Conversely, other viruses have been shown to drive DC maturation. In this regard, it has been reported that infection of iDCs with Dengue virus, human herpesvirus 6, or measles virus leads to upregulation of activation markers and enhances the production of some cytokines, a result indicative of their functional maturation (13, 15, 18, 38). Despite the activated phenotype, measles virus-infected DCs suppress mitogen-dependent proliferation of uninfected PBLs, indicating that they may potentially contribute to immune suppression in acute measles (13, 38). Finally, infection of already-mature DCs by varicella-zoster virus has been reported to downregulate maturation associated surface molecules and to inhibit DC allostimulatory capacity (30).

In the present study, we report that exposure of iDCs to surface components of inactivated R5 and X4 HIV-1 strains results in a clear-cut upmodulation of costimulatory and HLA class II molecules, as well as in the appearance of the CD83 maturation marker, indicative of DC maturation (Fig. 1). Identical results were obtained upon exposure of iDCs to recombinant gp120, which promoted these modifications in a specific and concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 2 and 3). However, functional studies indicated that, despite the activated phenotype, HIV-1-exposed DCs did not behave like mDCs (since they retained a considerable capacity to uptake antigens); did not secrete IL-12, TNF-α, and IL-10; exhibited a reduced secretion of a panel of CC-chemokines; and were poor stimulators of T-cell proliferation (Fig. 4).

We also report that iDCs, generated under standard conditions and stimulated to mature by LPS or CD40L in the presence of gp120, exhibit an apparently mature phenotype but are functionally impaired in terms of IL-12 production and capacity to induce T-cell proliferative responses (Fig. 5). Likewise, gp120 apparently does not affect monocyte differentiation into iDCs or their subsequent maturation induced by classical stimuli (i.e., LPS or CD40L), at least in terms of phenotypic features, but markedly interferes with the exploitation of their functional activities, in particular, IL-12 production (Fig. 6). Overall, these results suggest that gp120 can affect DC biology and functions at different levels by acting: (i) on DC precursors (blood monocytes) to generate iDCs exhibiting a canonical phenotype but incapable to undergo full activation upon maturation induction; (ii) on iDCs mimicking, at a phenotypic but not a functional level, the effect of a maturation inducing stimulus, when present alone; and (iii) on iDCs by inhibiting the activity of typical maturation stimuli in terms of functional activities but not of phenotypic features, when present concomitantly.

Some effects of HIV-1 or its proteins, including Nef, Tat, and gp120, on DC phenotype and/or functions have recently been reported, even though contrasting effects were described (9, 17, 29, 34, 41). In contrast with our results, Williams et al. reported that X4 gp120 exposure of iDCs results in the acquisition of an activated phenotype, correlating with increased IL-12 production and allostimulatory capacity (41). This discrepancy can be explained by the fact that different populations of monocytes were used to generate DCs, as well as by the different experimental conditions used to differentiate and stimulate these cells. Our findings are consistent with a recent report by Kawamura et al. showing that enriched populations of HIV-infected MDDCs exhibit an impaired ability to stimulate CD4+ T-cell proliferation and IL-2 production (19). This effect is mediated by soluble HIV gp120 produced and secreted by infected DCs, which directly suppresses T-cell proliferation.

HIV-1 infection elicits a broad range of host responses, many of which interfere with the regulatory pathways of IL-12 gene expression (24). In fact, IL-12 production is generally impaired in the course of HIV infection and the relevance of this IL-12 deficiency in HIV pathogenesis is suggested by the finding that exogenous IL-12 can restore immune responsiveness of peripheral leukocytes from AIDS patients (2, 4, 5, 6). In keeping with these previously published observations, our findings that DCs exposed to HIV-1 surface components exhibit an impaired capacity to produce IL-12 and that exogenous addition of IL-12 rescues the allostimulatory capacity of gp120-exposed DCs (Fig. 7) further point out the importance of HIV-1-mediated IL-12 impairment in AIDS pathogenesis and highlight DCs as potential candidate contributing to the IL-12 deficit observed in HIV infection.

DCs are currently divided into tolerogenic immature and immunogenic mature differentiation stages (40). A closer analysis reveals that tolerance is observed when partial maturation or semimaturation occurs, whereas only fully mature DCs are immunogenic. Interestingly, such semimature DCs exhibit a high expression of HLA class II and costimulatory molecules but lack the production of cytokines, including IL-12 and TNF-α, which seems to represent the decisive immunogenic signal (23, 26). Notably, many of the features exhibited by the so-called semimature DCs are shared by gp120 exposed DCs. We therefore speculate that gp120-induced phenotypic and functional alterations of DCs may result in the generation of DCs endowed with tolerogenic properties, which might ultimately lead to the expansion of T regulatory cells.

In light of our findings and of previously reported data, HIV-1 early targeting of MDDC functions may represent a novel mechanism exploited by HIV to subvert the host immune system. Exposure of iDCs to gp120 can lead to upmodulation of costimulatory and HLA class II molecules, thus favoring DC interaction with T cells. However, this interaction is likely to be not functional in terms of immune activation since important cytokines and chemokines are not produced and T-cell proliferation is not triggered. Moreover, the decreased capacity of DCs to produce CC-chemokines could result in an inefficient recruitment of immune cells endowed with the capacity to control viral infection. On the other hand, monocytes exposed to gp120 apparently undergo phenotypic differentiation or maturation into DCs, although their activities are strongly impaired. Overall, the gp120-mediated effects could contribute to the immunological abnormalities characterizing the AIDS pathogenesis through the generation of DCs subtracting uninfected T lymphocytes from the pool of cells able to mount an immune response. The aberrant pathway of DC maturation could also contribute to the elimination of the gp120-exposed poorly active DCs, which could undergo apoptosis (generally enhanced in mature versus immature cells) or become a more suitable natural killer (NK) cell target than classical mDCs, in view of their poor expression of HLA class I molecules, generally associated with increased resistance to NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity (12). Since the capacity of gp120 to phenotypically or functionally modulate DCs is not restricted to specific viral strains, these gp120-mediated effects might be operative at all stages of disease.

HIV-1 gp120 can mediate multiple effects depending on the context. Infected DCs have been described as important sources for gp120 release in the microenvironment and the released protein may impair T-cell proliferation (19). However, other DCs, not directly infected by HIV-1 but exposed to gp120 could contribute to the impairment of immune responses by virtue of their aberrant maturation not leading to an efficient T-cell activation.

Overall, these results may provide an explanation for the general impairment of the immune system observed in AIDS. Understanding how these and potentially other HIV-mediated manipulations of DCs are achieved is crucial to identify strategies biasing the DC system toward the activation of protective immune responses instead of facilitating virus spread.

Acknowledgments

We thank Stefano Billi and Marco Cardone for preparing drawings and Anna Maria Fattapposta for editorial assistance. We thank the centralized facility for AIDS reagents supported by the EU Programme EVA/MRC (contract QLKZ-CT-1999-00609) and the United Kingdom Medical Research Council for providing recombinant HIV-1 gp120 IIIB strain, the National Institutes of Health AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program for providing antiserum to gp120, and George Gao for kindly providing recombinant HIV-1 gp120 Ada strain. We are indebted with Pasqualina Bovenzi, Mira van de Velde, and Joanna La Bresh for technical support with the multiplex sandwich ELISA.

This study was supported by a research grant from the National Institutes of Health (1 R21 AI054215-01) and by EC contract QLK2-CT-2001-02103.

REFERENCES

- 1.Banchereau, J., F. Briere, C. Caux, J. Davoust, S. Lebecque, Y. J. Liu, B. Pulendran, and K. Palucka. 2000. Immunobiology of dendritic cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18:767-811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chemini, J., S. E. Starr, I. Frank, A. D'Andrea, X. Ma, R. R. MacGregor, J. Sennelier, and G. Trinchieri. 1994. Impaired interleukin-12 production in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. J. Exp. Med. 179:1361-1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chirmule, N., and S. Pahwa. 1996. Envelope glycoproteins of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: profound influences on immune functions. Microbiol. Rev. 60:386-406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clerici, M., and G. M. Shearer. 1993. A Th1→Th2 switch is a crucial step in the etiology of HIV-1 infection. Immunol. Today 14:107-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clerici, M., D. R. Lucey, J. A. Berzofsky, L. A. Pinto, T. A. Wynn, S. P. Blatt, M. J. Dolan, C. W. Hendrix, S. F. Wolf, and G. M. Shearer. 1993. Restoration of HIV-1 specific cell-mediated immune responses by interleukin-12 in vitro. Science 262:1721-1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Denis, M., and E. Ghadirian. 1994. Dysregulation of interleukin 8, interleukin 10, and interleukin 12 release by alveolar macrophages from HIV-1 type 1-infected subjects. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 10:1619-1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dolganiuc, A., K. Kodys, A. Kopasz, C. Marshall, T. Do, L. Jr Romics, P. Mandrekar, M. Zapp, and G. Szabo. 2003. Hepatitis C virus core and nonstructural protein 3 proteins induce pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines and inhibit dendritic cell differentiation. J. Immunol. 170:5615-5624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engelmayer, J., M. Larsson, M. Subklewe, A. Chahroudi, W. I. Cox, R. M. Steinman, and N. Bhardwaj. 1999. Vaccinia virus inhibits the maturation of human dendritic cells: a novel mechanism of immune evasion. J. Immunol. 163:6762-6768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fanales-Belasio, E., S. Moretti, F. Nappi, G. Barillari, F. Micheletti, A. Cafaro, and B. Ensoli. 2002. Native HIV-1 Tat protein targets monocyte-derived dendritic cells and enhances their maturation, function, and antigen-specific T cell responses. J. Immunol. 168:197-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fantuzzi, L., I. Canini, F. Belardelli, and S. Gessani. 2001. HIV-1 gp120 stimulates the production of β-chemokines in human peripheral blood monocytes through a CD4-independent mechanism. J. Immunol. 166:5381-5387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fantuzzi, L., I. Canini, F. Belardelli, and S. Gessani. 2001. IFN-β stimulates the production of β-chemokines in human peripheral blood monocytes: importance of macrophage differentiation. Eur. Cytokine Netw. 12:597-603. [PubMed]

- 12.Ferlazzo, G., C. Semino, and G. Melioli. 2001. HLA class I molecule expression is up-regulated during maturation of dendritic cells, protecting them from natural killer cell-mediated lysis. Immunol. Lett. 76:37-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fugier-Vivier, I., C. Servet-Delprat, P. Rivailler, and M. C. Rissoan. 1997. Measles virus suppresses cell-mediated immunity by interfering with the survival and functions of dendritic and T cells. J. Exp. Med. 186:813-823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gauzzi, M. C., I. Canini, P. Eid, F. Belardelli, and S. Gessani. 2002. Loss of type I IFN receptors and impaired IFN responsiveness during terminal maturation of monocyte-derived human dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 169:3038-3045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ho, L. J., J. J. Wang, M. F. Shaio, C. L. Kao, D. M. Chang, S. W. Han, and J. H. Lai. 2001. Infection of human dendritic cells by dengue virus causes cell maturation and cytokine production. J. Immunol. 166:1499-1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu, J., M. B. Gardner, and C. J. Miller. 2000. Simian immunodeficiency virus rapidly penetrates the cervicovagina mucosa after intravaginal inoculation and infects intraepithelial dendritic cells. J. Virol. 74:6087-6095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Izmailova, E., F. M. N. Bertley, Q. Huang, N. Makori, C. J. Miller, R. A. Young, and A. Aldovini. 2003. HIV-1 Tat reprograms immature dendritic cells to express chemoattractants for activated T cells and macrophages. Nat. Med. 9:191-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kakimoto, M., A. Hasegawa, S. Fujita, and M. Yasukawa. 2002. Phenotypic and functional alterations of dendritic cells induced by human herpesvirus 6 infection. J. Virol. 76:10338-10345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawamura, T., H. Gatanga, D. L. Borris, M. Connors, H. Mitsuya, and A. Blauvelt. 2003. Decreased stimulation of CD4+ T cell proliferation and IL-2 production by highly enriched populations of HIV-1-infected dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 170:4260-4266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knight, S. C. 2001. Dendritic cells and HIV infection: immunity with viral transmission versus compromised cellular immunity? Immunobiology 204:614-621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lanzavecchia, A., and F. Sallusto. 2001. Regulation of T cell immunity by dendritic cells. Cell 106:263-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.LiQi, L., L. Daorong, L. Hutt-Fletcher, A. Morgan, M. G. Masucci, and V. Levitsky. 2002. Epstein-Barr inhibits the development of dendritic cells by promoting apoptosis of their monocyte precursors in the presence of granulocyte macrophage-colony-stimulating factor and interleukin-4. Blood 99:3725-3734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lutz, M. B., and G. Schuler. 2002. Immature, semi-mature and fully mature dendritic cells: which signals induce tolerance or immunity? Trends Immunol. 23:445-449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma, X., and L. J. Montaner. 2000. Proinflammatory response and IL-12 expression in HIV-1 infection. J. Leukoc. Biol. 68:383-390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mahanty, S., K. Hutchinson, S. Agarwal, M. Mcrae, P. E. Rollin, and B. Pulendran. 2003. Cutting edge: impairment of dendritic cells and adaptive immunity by Ebola and Lassa viruses. J. Immunol. 170:2797-2801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahnke, K., E. Schmitt, L. Bonifaz, A. H. Enk, and H. Jonuleit. 2002. Immature, but not active: the tolerogenic function of immature dendritic cells. Immunol. Cell. Biol. 80:477-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Makino, M., W. Shin-ichi, S. Satoshi, A. Naomichi, and B. Masanori. 2000. Production of functionally deficient dendritic cells from HTLV-1-infected monocytes: implications for the dendritic cell defect in adult T-cell leukemia. Virology 274:140-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mellman, I., and R. M. Steinman. 2001. Dendritic cells: specialized and regulated antigen processing machines. Cell 106:255-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Messmer, D., J. M. Jacquè, C. Santisteban, C. Bristow, S. Y. Han, L. Villamide-Herrera, E. Mehlhop, P. A. Marx, R. M. Steinman, A. Gettie, and M. Pope. 2002. Endogenously expressed nef uncouples cytokine and chemokine production from membrane phenotypic maturation in dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 169:4172-4182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morrow, G., B. Slobedman, A. L. Cunningham, and A. Abendroth. 2002. Varicella-zoster virus productively infects mature dendritic cells and alters their immune function. J. Virol. 77:4950-4959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moser, B., and P. Loetscher. 2001. Lymphocyte traffic control by chemokines. Nat. Immunol. 2:123-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palucka, K., and J. Banchereau. 2002. How dendritic cells and microbes interact to elicit or subvert protective immune responses. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 14:420-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pulendran, B., K. Paluka, and J. Banchereau. 2001. Sensing pathogens and tuning the immune responses. Science 293:253-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Quaranta, M. G., E. Tritarelli, L. Giordani, and M. Viora. 2002. HIV-1 nef induces dendritic cell differentiation: a possible mechanism of uninfected CD4+ T cell activation. Exp. Cell Res. 275:243-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Romagnani, S. 1997. The Th1/Th2 paradigm. Immunol. Today 18:263-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rossio, J. L., M. T. Esser, K. Suryanarayana, D. K. Schneider, J. W. Jr Bess, G. M. Vasquez, T. A. Wiltrout, E. Chertova, M. K. Grimes, Q. Sattentau, L. O. Arthur, L. E. Henderson, and J. D. Lifson. 1998. Inactivation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infectivity with preservation of conformational and functional integrity of virion surface proteins. J. Virol. 72:7992-8001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salio, M., M. Cella, M. Suter, and A. Lanzavecchia. 1999. Inhibition of dendritic cell maturation by herpes simplex virus. Eur. J. Immunol. 29:3245-3253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schnorr, J. J., S. Xanthakos, P. Keikavoussi, E. Kampgen, V. ter Meulen, and S. Schneider-Schaulies. 1997. Induction of maturation of human blood dendritic cell precursor by measles virus is associated with immunosuppression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:5326-5331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sewell, A. K., and D. A. Price. 2001. Dendritic cells and transmission of HIV-1. Trends Immunol. 22:173-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steinman, R. M., D. Hawiger, and M. C. Nussenzweig. 2003. Tolerogenic dendritic cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 21:685-711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Williams, M. A., R. Trout, and S. A. Spector. 2002. HIV-1 gp120 modulates the immunological function and expression of accessory and co-stimulatory molecules of monocyte-derived dendritic cells. J. Hematother. Stem Cell Res. 11:829-847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]