Abstract

Although national and state estimates of child obesity are available, data at these levels are insufficient to monitor effects of local obesity prevention initiatives. The purpose of this study was to examine regional changes in the prevalence of obesity due to state-wide policies and programs among children in grades 4, 8, and 11 in Texas Health Service Regions (HSR) between 2000–2002 and 2004–2005, and nine selected counties in 2004–2005. A cross-sectional, probability-based sample of 23,190 Texas students in grades 4, 8, and 11 were weighed and measured to obtain body mass index (BMI). Obesity was greater than 95th percentile for BMI by age/sex using CDC growth charts. Child obesity prevalence significantly decreased between 2000–2002 and 2004–2005 for 4th grade students in the El Paso HSR (−7.0%, p=0.005). A leveling off in the prevalence of obesity was noted for all other regions for grades 4, 8 and 11. County-level data supported the statistically significant decreases noted in the El Paso region. The reduction of child obesity levels observed in the El Paso area is one of the few examples of effective programs and policies based on a population-wide survey: in this region, a local foundation funded extensive regional implementation of community programs for obesity prevention, including an evidence-based elementary school-based health promotion program, adult nutrition and physical activity programs, and a radio and television advertising campaign. Results emphasize the need for sustained school, community and policy efforts, and that these efforts can result in decreases in child obesity at the population level.

Keywords: child and adolescent overweight, child & adolescent obesity, nutrition, physical activity, children, adolescents, SPAN, CATCH, BMI, surveillance, obesity prevention

INTRODUCTION

Although the recent U.S. national rates for child obesity has shown no significant changes in the last few years, child obesity is still a significant problem, with 16.3% of 2–19 year old children classified as obese (at or above the 95th percentile based on CDC growth charts). (1) Several reviews have addressed recommendations and best practices to prevent or decrease rates of child obesity at the population level, and it is generally thought that a multilevel approach has the greatest chance of success (2–4). Despite these recommendations, few examples of multilevel programs targeted at a community level have been conducted. In addition, although several child obesity prevention programs have shown promising effects, (5–8) only one has documented community-level changes, (5) and this was in a mid-sized city in Massachusetts as part of a community-based participatory research study.

Many communities are implementing local programs and policies for prevention of child obesity. (9) These programs are often funded, developed, and/or implemented by foundations or health agencies, and may or may not be evidence-based or include an evaluation component. Without regional and local level measurement, the population effects of these programs may not be evident.

In addition to local programs, states and municipalities have begun to implement policies designed to address the child obesity problem. In Texas, several statewide policies, initiatives, and legislative mandates to target child obesity have been enacted. The most comprehensive legislation introduced during the timeframe of this study include Texas Senate Bill 19 from 2001 and Texas Senate Bill 1357 from 2003 (now Texas Education Agency Code 38.013 & 28.004). (10) These mandates provide for 135 minutes of physical activity/week for elementary school students, the establishment of School Health Advisory Councils, and the implementation of Texas Education Agency (TEA)-approved Coordinated School Health Programs (CSHP) based on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) model. (11,12) The first two provisions took effect in 2001, while the implementation of CSHP in elementary schools was not required until the end of the 2006–2007 school year. In addition to this legislation, in 2004, the Texas Department of Agriculture instituted the Texas Public School Nutrition Policy, (13) which regulates the types of foods available at all school levels. Unfortunately, state funds were not allocated for these regulatory efforts, and so, local and regional districts and schools must find additional funds in their budgets to implement these policies. Without consistent funding for these mandates, it is possible that differences in the implementation of these regulatory efforts across the state can have differential effects on the intended legislative outcomes.

The purpose of this study was to examine regional changes in the prevalence of child obesity due to state-wide policies and programs among children in grades 4, 8 and 11 in Texas Health Services Regions (HSR) between 2000–2002 and 2004–2005, and in nine selected counties in 2004–2005 using the School Physical Activity and Nutrition (SPAN) population-based surveillance data.

METHODS AND PROCEDURES

Study Design

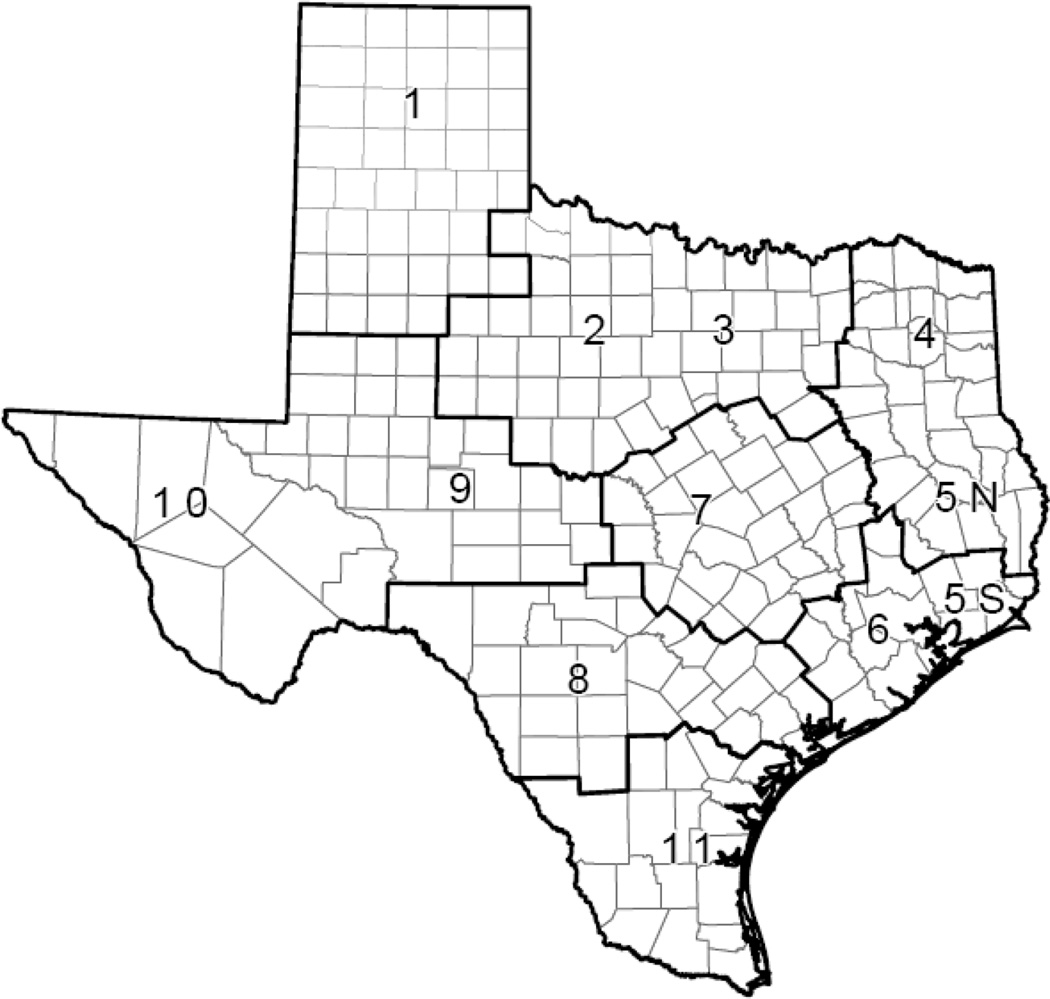

Design, sampling, analysis and measurement details about the SPAN study have been previously reported. (14,15) SPAN was designed to yield representative data at the state level, as well as to provide representative estimates at the Texas Department of State Health Services (TDSHS) regional level. (14) The TDSHS originally divided Texas into 11 HSRs to provide for administration of programs and management oversight on a local basis, as well as to build public health infrastructure; these regions were later combined into eight geographic units (Figure 1). (16) To provide comparable estimates across the years, data from both surveys (2000–2002 and 2004–2005) were analyzed using the current eight region division.

Figure 1.

Texas Health Services Regions, 2004–2005.1

1Numbers indicate original division of regions; lines indicate current boundaries for administrative and management purposes. (13)

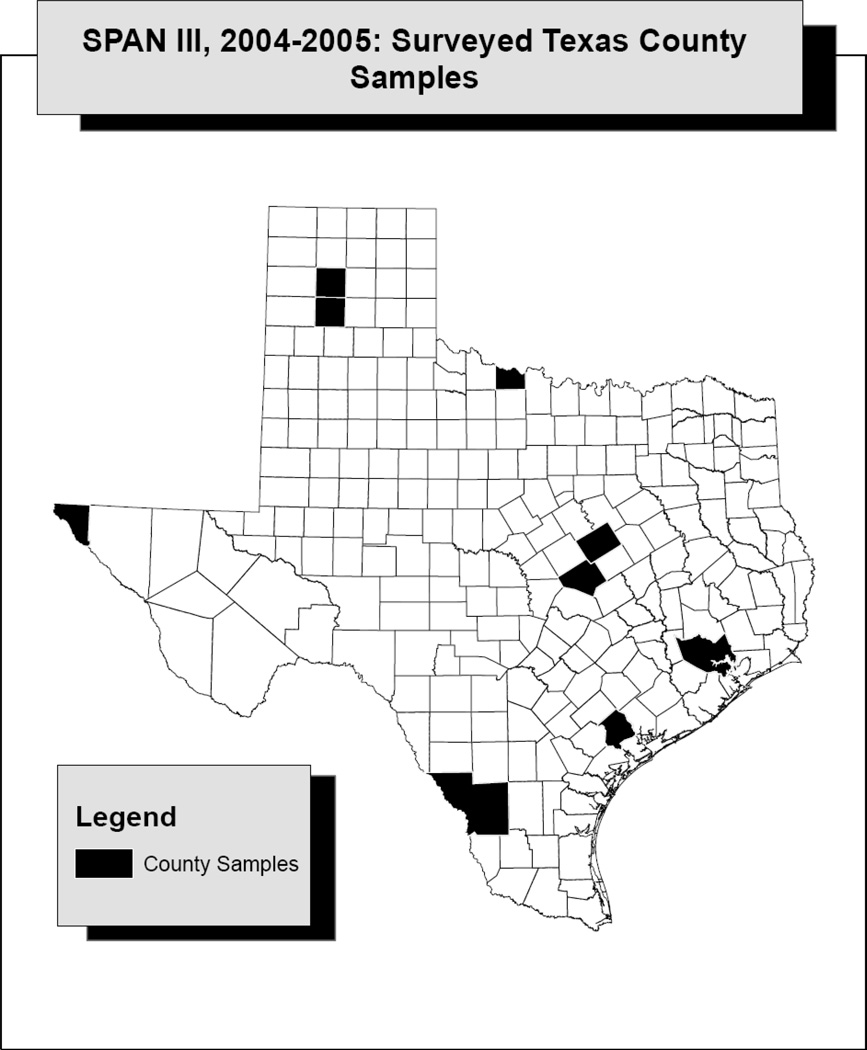

In addition to the regional data, Texas counties were invited to participate in the SPAN measurement so that more precise estimates could be generated for local purposes. After an application process, nine individual counties, located throughout the state, were selected for the survey. These selected areas included large counties, such as the Harris County/Houston area, and smaller counties in the Texas Panhandle (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Distribution of Counties selected for Texas SPAN, 2004–2005.

Subjects

Children in grades 4, 8 and 11 were targeted for the state survey to represent different age and developmental levels. (14,17) School districts selected for the survey were contacted by study staff and individual schools were contacted once district approvals were obtained.

Approval for this study was obtained from the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, HSC-SPH-00–056, as well as the Institutional Review Board of the TDSHS, 04–062, and participating school districts. Parental consent was obtained from students before participation in the study; students with parental consent completed an assent form prior to administration of the SPAN questionnaire at the school.

Sampling

Details about the sampling for SPAN 2000–2001 are provided elsewhere, and included HSR areas 1, 3, 5, 7 and 11. (14) SPAN 2001–2002 included measurement of the remainder of the HSR areas (2, 4, 6, 8, 9, 10); information from both surveys were combined to form a statewide estimate for 2000–2002. For the 2004–2005 survey, public schools were selected based on data obtained from the Texas Education Agency for the 2003–2004 school year. (18) Schools which had fewer than 75 students at one of the selected grade levels (4, 8 and 11), or were charter, magnet or special schools were excluded from the sampling frame. The final sampling frame for the 2004–2005 Texas sample contained 3,860 schools, which covered a population size of 774,263 children in grades 4, 8, and 11. (15)

The sampling frame and strata for the HSR survey have been previously described. (15) Briefly, the three strata within the HSR include the urban center (largest school district), other urban/suburban schools, and rural schools. The final sampling frames for the nine counties ranged from 7 to 607 schools. If necessary, oversampling was performed at the school level to accommodate the statistical requirement for the county level estimate.

Data Collection

Data collection at both state and county levels was conducted by trained and certified project staff, and state and county personnel. Questionnaires were distributed and collected through the main SPAN study office, and at least one site visit was conducted by SPAN staff during county data collection.

Measures

Elementary (4th grade) and secondary (8th/11th grade) questionnaires adapted from the School-Based Nutrition Monitoring (SBNM) survey were administered to study participants. (17,19, 20) Demographic data for the students, such as age, race/ethnicity and gender, were self-reported on the questionnaires. For analytic purposes, race/ethnicity was classified as African American, Hispanic/Latino, or White/Other; White/Other included non-Hispanic white, Native American, Asian, Pacific Islander, or “other”. (14)

Measurement of Height and Weight and Calculation of Body Mass Index

Measurement of height and weight were conducted using standard protocols and recommendations; (21) data were recorded directly on the questionnaire form after the students completed the written items. Student weight was recorded in kilograms using a calibrated top-loading scale (Tanita BWB 800S), and measured student height in centimeters with a Perspectives Enterprises stadiometer.

Height and weight were used to calculate body mass index (BMI), using the standard formula, (22) and classified as obese, overweight, and normal weight, using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth charts (23) and current recommendations. (24)

Data Quality Control

At all schools, 5% of the study sample was re-measured for height and weight for quality control purposes. Almost all (98.5%) of the repeated weight measurements were within 0.2 kg, while 98.9% of the repeated height measurements were within 1.2 cm.

Imputations were used to maximize sample size for representative calculations by subgroup (e.g., gender and race/ethnicity) at the HSR level; subjects with more than one missing data point were excluded from the analysis. A total of 252 cases (1% of total) were excluded from the dataset, and a total of 510 logical and mean imputations were made for variables such as birth date, age, ethnicity, height, and weight. A more detailed breakdown of the exclusions, inclusions and imputations is presented elsewhere. (15)

Data Analysis

Estimated differences between SPAN 2000–2002 and 2004–2005 were tested at the HSR level. For the 2004–2005 county level data, prevalence of obesity was compared between counties at a cross-sectional level. All analyses are reported separately by grade.

Estimation Procedure

Sampling probability weights were calculated to account for differential inclusion probabilities in multistage sampling. Sampling weights were the inverse of selection probability that encompassed the sampling ratio at each stage of selection. Post-stratification weight adjustments were made to ensure ethnic composition in the sample was the same as the total school enrollment in each HSR in the sampling frame. The estimates for the nine selected counties were based on the schools selected for the state/region sample as well as the schools selected in oversampling. Sampling weights for the county level estimate were calculated separately from the state/region sample. Post-stratification weights were also developed to ensure ethnic composition at the county level. Thus, two sets of sampling weights were computed and used: one for the county data and another one for the region.

All estimates were weighted and statistical tests performed taking into account each sample design features (stratification of the sample and clustering of students within schools). Statistical analyses are reported with the appropriate sampling weights for the HSR data or the county level data. The survey analysis module of STATA (Version 9.0, College Station, Texas) was used to analyze the data using Taylor series approximation or linearization model.

RESULTS

Although mean age and gender distribution was similar by region and county, the racial/ethnic distributions for counties and regions were variable and diverse, which is consistent with the current population distribution of Texas (Tables 1 and 2). South Texas and the Texas-Mexico border regions and counties have majority Latino populations, while East and Central Texas regions and counties have significant African American populations, and the North Texas and Panhandle regions and counties tend to be less diverse compared to the rest of the state.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of students in Texas Health Services Regions, SPAN, 2004–2005.a

| Texas Health Service Region | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (n=5675)b (N=18,959)c |

2–3 (n=2552) (N=217,497) |

4–5N (n=1928) (N=37171) |

6–5S (n=1483) (N=219667) |

7 (n=4043) (N=76115) |

8 (n=2500) (N=77604) |

9–10 (n=1977) (N=48102) |

11 (n=3032) (N=79148) |

|

| 4th Grade | n=1,217 | n=805 | n=834 | n=487 | n=1,620 | n=974 | n=786 | n=1,184 |

| Gender (%) | ||||||||

| Male | 52 | 51 | 51 | 51 | 51 | 52 | 51 | 51 |

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | ||||||||

| White/Other | 49 | 57 | 64 | 46 | 51 | 34 | 18 | 9 |

| Hispanic | 43 | 28 | 16 | 36 | 35 | 59 | 80 | 90 |

| African American | 8 | 14 | 20 | 18 | 15 | 7 | 2 | 1 |

| Age (Mean±SE) | 9.9±0.05 | 9.8±0.03 | 9.7±0.05 | 9.7±0.12 | 9.7±0.02 | 9.8±0.04 | 9.7±0.05 | 9.7±0.05 |

| 8th Grade | n=2,568 | n=990 | n=623 | n=502 | n=1,213 | n=914 | n=700 | n=1,317 |

| Gender (%) | ||||||||

| Male | 50 | 51 | 51 | 51 | 51 | 51 | 51 | 51 |

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | ||||||||

| White/Other | 51 | 58 | 65 | 49 | 45 | 33 | 23 | 10 |

| Hispanic | 41 | 25 | 14 | 31 | 40 | 60 | 73 | 89 |

| African American | 8 | 17 | 22 | 20 | 15 | 7 | 4 | 1 |

| Age (Mean±SE) | 13.8±0.03 | 13.8±0.03 | 13.8±0.07 | 13.7±0.14 | 13.7±0.05 | 13.7±0.06 | 13.8±0.03 | 13.7±0.03 |

| 11th Grade | n=1,890 | n=757 | n=471 | n=494 | n=1,210 | n=612 | n=491 | n=531 |

| Gender (%) | ||||||||

| Male | 52 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 48 | 51 | 52 | 51 |

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | ||||||||

| White/Other | 57 | 62 | 68 | 56 | 54 | 37 | 28 | 12 |

| Hispanic | 36 | 21 | 11 | 26 | 31 | 56 | 70 | 88 |

| African American | 8 | 17 | 21 | 18 | 15 | 7 | 2 | <1 |

| Age (Mean±SE) | 16.7±0.03 | 16.8±0.04 | 16.7±0.03 | 16.7±0.10 | 16.8±0.08 | 16.7±0.06 | 16.7±0.04 | 17.0±0.06 |

Column percentages may not add up to 100 due to rounding.

Indicates actual measured sample size

Indicates population size for region and weighted data

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of students in selected Texas counties participating in the SPAN survey, 2004–2005.

| El Paso County (n=1164)a (N=32023)b |

Randall County (n=1203) (N=1463) |

Bell County (n=1267) (N=9481) |

McLennan County (n=2010) (N=6234) |

Harris County (n=1035) (N=136712) |

Victoria County (n=1684) (N=2694) |

Wichita County (n=1505) (N=3822) |

Potter County (n=3513) (N=4990) |

Webb County (n=1529) (N=11055) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4th Grade | n = 488 | n =275c | n = 527 | n = 766c | n = 318 | n = 589c | n = 437c | n = 628c | n = 648 |

| Gender (%) | |||||||||

| Male | 51 | 56 | 52 | 52 | 51 | 53 | 53 | 49 | 52 |

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | |||||||||

| White/Other | 10 | 86 | 46 | 54 | 33 | 40 | 78 | 46 | 2 |

| Hispanic | 88 | 12 | 21 | 27 | 47 | 52 | 12 | 42 | 98 |

| African American | 2 | 2 | 33 | 19 | 21 | 8 | 10 | 13 | <1 |

| Age (Mean±SE) | 9.7±.06 | 9.7±0.08 | 9.8±.04 | 9.7±0.03 | 9.6±.21 | 9.7±0.05 | 9.7±0.04 | 9.8±0.03 | 9.7±0.06 |

| Participation (%) | 69.7 | 93.2 | 75.3 | 95.8 | 45.4 | 82.5 | 84.5 | 80.9 | 92.6 |

| 8th Grade | n = 422 | n = 497c | n = 318 | n = 617c | n = 384 | n = 651c | n = 626c | n = 1754c | n = 749c |

| Gender (%) | |||||||||

| Male | 51 | 50 | 53 | 51 | 51 | 51 | 52 | 52 | 50 |

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | |||||||||

| White/Other | 10 | 87 | 45 | 52 | 36 | 42 | 70 | 55 | 2 |

| Hispanic | 87 | 12 | 21 | 27 | 41 | 50 | 17 | 36 | 98 |

| African American | 3 | 2 | 34 | 21 | 22 | 8 | 13 | 9 | <1 |

| Age (Mean±SE) | 13.8±.04 | 13.9±0.02 | 13.9±.02 | 13.7±0.02 | 13.7±.12 | 13.7±0.05 | 13.7±0.03 | 13.7±0.03 | 13.6±0.03 |

| Participation (%) | 60.3 | 79.0 | 45.4 | 94.9 | 54.9 | 60.5 | 69.6 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| 11th Grade | n = 254 | n = 431c | n = 422c | n = 627c | n = 333 | n = 444c | n = 442c | n = 1,131c | n = 132c |

| Gender (%) | |||||||||

| Male | 51 | 55 | 50 | 51 | 50 | 50 | 51 | 53 | 51 |

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | |||||||||

| White/Other | 13 | 87 | 49 | 55 | 44 | 48 | 73 | 64 | 2 |

| Hispanic | 84 | 12 | 19 | 23 | 35 | 45 | 15 | 28 | 98 |

| African American | 3 | 1 | 32 | 22 | 21 | 7 | 12 | 8 | 0 |

| Age (Mean±SE) | 16.7±.03 | 16.8±0.04 | 16.7±.05 | 16.6±0.04 | 16.6±.11 | 16.6±0.03 | 16.7±0.04 | 16.6±0.06 | 17.0±0.05 |

| Participation (%) | 36.3 | 79.5 | 60.3 | 83.6 | 47.6 | 50.1 | 58.9 | 100.0 | 18.9 |

Indicates actual measured sample size

Indicates population size for region and weighted data

Census sample targeted

Participation rates for the SPAN survey varied by year and grade level (Tables 2 and 3). In 2000–2002, participation rates at the HSR level ranged from 32.3% to 100.0%, while participation rates at the HSR for 2004–2005 ranged from 67.3 to 100.0%, respectively. Participation rates for the county samples ranged from 18.9% to 100.0%. For a population-based sample, a participation rate of 60% or greater is considered acceptable. (25)

Table 3.

| Texas Health Service Region |

2000–2002 | Participationc (%) |

2004 2005 |

Participationc (%) |

Net Difference | 95% CId of Net Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4th grade | ||||||

| 1 | 20.0 | 78.8 | 23.0 | 100.0 | 3.0 | −2.6, 8.5 |

| 2–3 | 21.1 | 78.0 | 20.9 | 100.0 | −0.2 | −5.1, 4.8 |

| 4–5N | 21.3 | 72.8 | 20.6 | 100.0 | −0.6 | −4.5, 3.2 |

| 6–5S | 28.5e | 51.9 | 22.5 | 69.6 | −6.0 | −22.2, 10.2 |

| 7 | 23.3 | 69.2 | 23.5 | 100.0 | 0.2 | −5.2, 5.6 |

| 8 | 30.3 | 66.0 | 28.7 | 100.0 | −1.5 | −9.1, 6.1 |

| 9–10 | 25.8 | 77.4 | 18.8 | 100.0 | −7.0 | −11.7, −2.3f |

| 11 | 25.8 | 100.0 | 30.6 | 100.0 | 4.8 | −0.8, 10.4 |

| NHANES, USg | 16.3 | - | 17.0 | - | 0.7 | - |

| 8th grade | ||||||

| 1 | 23.5e | 48.9 | 20.0 | 100.0 | −3.5 | −12.1, 5.1 |

| 2–3 | 17.2 | 71.9 | 19.1 | 100.0 | 1.8 | −6.3, 10.0 |

| 4–5N | 23.5e | 58.5 | 25.2 | 89.0 | 1.7 | −4.5, 7.9 |

| 6–5S | 15.6e | 54.8 | 12.6 | 71.7 | −3.0 | −15.3, 9.3 |

| 7 | 17.2 | 78.5 | 17.0 | 100.0 | −0.2 | −8.8, 8.4 |

| 8 | 19.7 | 66.3 | 17.1 | 100.0 | −2.7 | −16.5, 11.2 |

| 9–10 | 20.9 | 73.7 | 17.7 | 100.0 | −3.2 | −10.6, 4.3 |

| 11 | 24.2e | 57.6 | 21.7 | 100.0 | −2.5 | −8.9, 3.9 |

| NHANES, USh | 16.7 | - | 17.6 | - | 0.9 | - |

| 11th grade | ||||||

| 1 | 21.1e | 40.0 | 15.4 | 100.0 | −5.6 | −14.3, 3.0 |

| 2–3 | 11.0e | 41.3 | 19.9 | 100.0 | 8.9 | −1.9, 19.8 |

| 4–5N | 18.3e | 44.3 | 17.2 | 67.3 | −1.1 | −5.7, 3.5 |

| 6–5S | 11.1e | 35.3 | 15.5 | 70.6 | 4.4 | −3.0, 11.7 |

| 7 | 13.9e | 46.8 | 10.0 | 100.0 | −4.0 | −12.7, 4.8 |

| 8 | 18.1e | 32.3 | 21.1 | 87.4 | 3.0 | −4.9, 10.9 |

| 9–10 | 17.4e | 51.7 | 18.9 | 70.1 | 1.5 | −8.2, 11.2 |

| 11 | 26.3e | 47.2 | 16.2 | 75.9 | −10.0 | −16.8, −3.3g |

| NHANES, USh | 16.7 | - | 17.6 | - | 0.9 | - |

Obesity indicates ≥ 95th percentile by gender & age for CDC charts.

School Physical Activity and Nutrition

Indicates number of students measured/target number of students needed for sampling scheme

Confidence interval.

Indicates that participation rate for sample was less than 60%

Data from NHANES, 2001–2002 (Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. JAMA 2006 Apr 5 295(13):1549–1555.) and NHANES, 2003–2006 (Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. High body mass index for age among US children and adolescents, 2003–2006. JAMA 2008 May 28 299(20):2401–2405.),for children aged 6–11.

Confidence intervals do not include 0.

Data from NHANES, 2001–2002 (Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. JAMA 2006 Apr 5 295(13):1549–1555.) and NHANES 2003–2006 (Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. High body mass index for age among US children and adolescents, 2003–2006. JAMA 2008 May 28 299(20):2401–2405.) for children aged 12–19

The prevalence of obesity in 4th grade students in HSR 9–10, the El Paso area, showed a statistically significant (p=0.005) decrease in child obesity between 2000–2002 and 2004–2005, from 25.8 % to 18.8% (Table 3). Health Service Region (HSR) 9–10 consists of 36 counties in West Texas; of these counties, El Paso County is the largest, with a population of 743,319 in 2006, which is 57% of the population of HSR 9–10 (26) HSR 9–10 did not include any of the other Texas counties measured in this study. In addition, a statistically significant (p=0.006) decrease in the prevalence of obesity (10.0%) was found among 11th grade students in HSR 11 (Lower Rio Grande Valley area in South Texas); however, participation rates for 11th grade students in HSR 11 were 47.2% for the 2000–2002 data (Table 3), which indicates lower confidence in this relationship. None of the other regions showed statistically significant changes in the prevalence of obesity for any grade level.

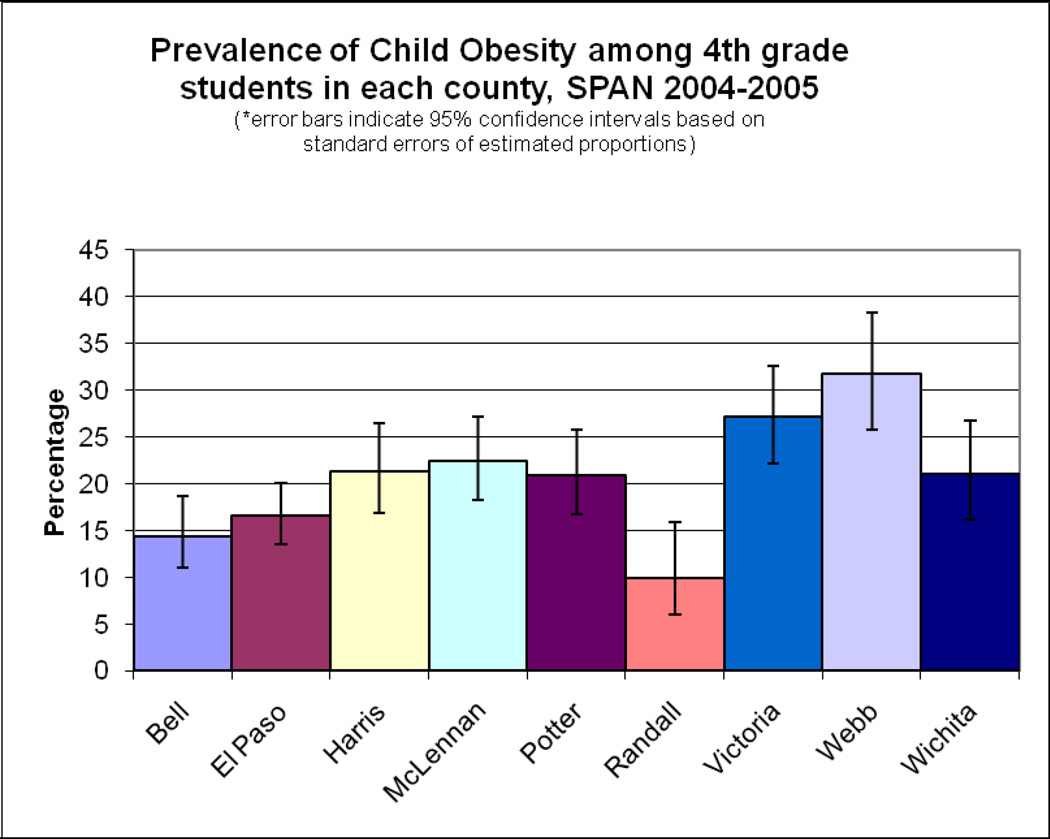

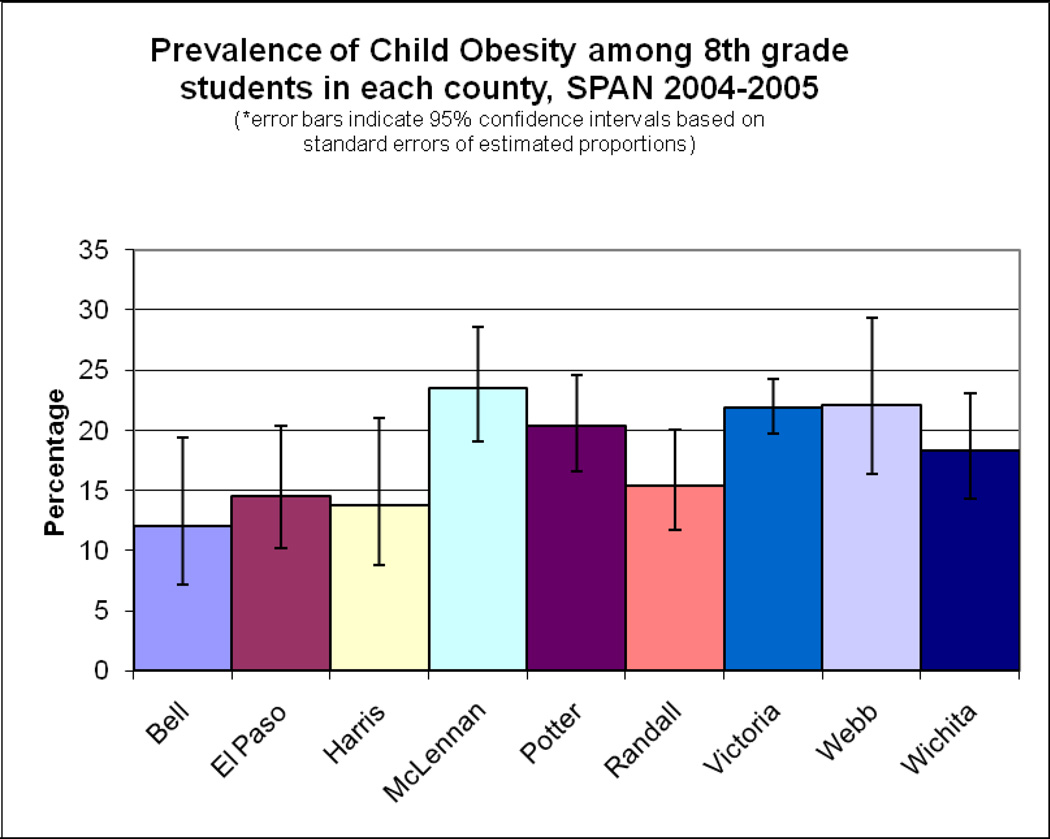

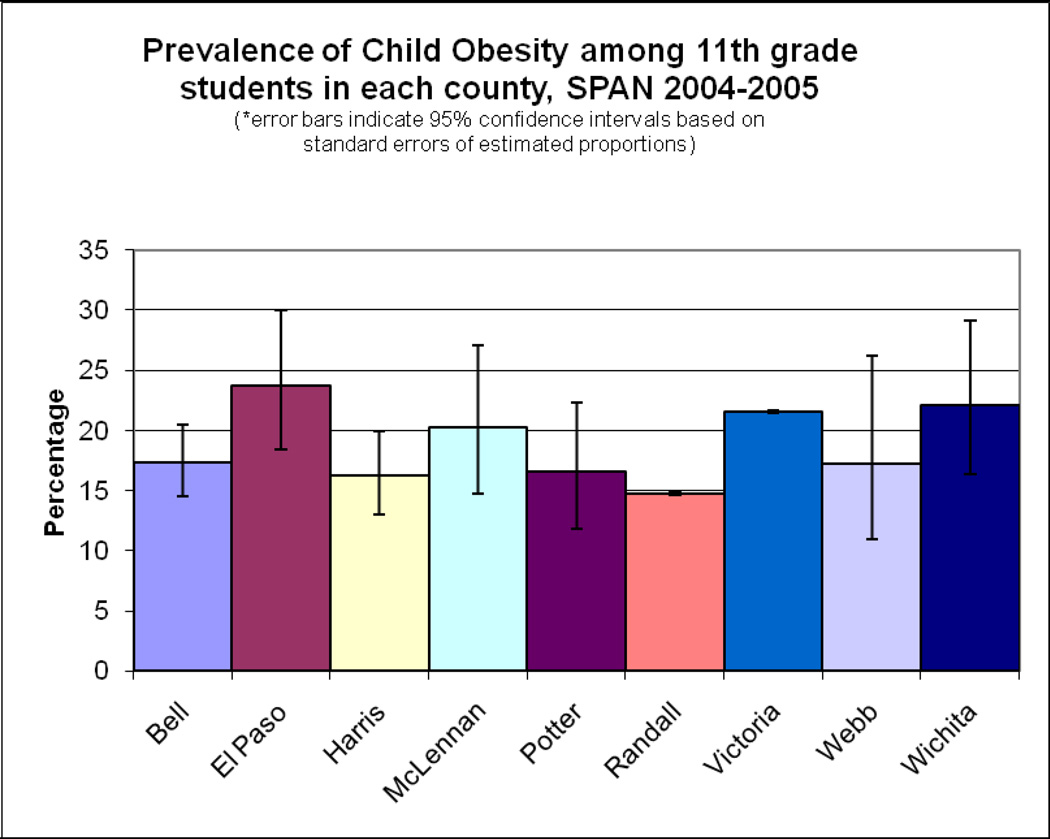

Cross-sectional county data results were consistent with findings from the regional data (Figure 3). Among 4th grade students, both Bell (Central Texas) and El Paso (West Texas) Counties had lower prevalence of obesity compared to Webb (South Texas on the border) and Victoria (South Texas) Counties (14.4 and 16.5% compared to 31.7 and 27.1%, respectively, 95% Confidence Intervals [CI] do not overlap). El Paso and Webb Counties both have similar demographics (Table 2) and are located on the Texas-Mexico border (Figure 2). The prevalence of obesity among children in Randall County (Amarillo area, Texas Panhandle) is significantly lower than those in Harris (Houston area), McLennan (Waco area in Central Texas), Potter (Amarillo area, Texas Panhandle), Victoria, Wichita (North Texas on Oklahoma border), and Webb Counties. Among 8th grade students, students in Bell County had a significantly lower prevalence of obesity compared to Victoria County (Figure 3). In 11th grade students, significant differences in adolescent obesity were seen between students in Randall County compared to Victoria, El Paso, and Wichita Counties (14.7% compared to 21.5%, 23.7%, and 22.1% respectively; CI do not overlap).

Figure 3.

Prevalence of child obesity1 among students in selected Texas Counties, Texas SPAN2, 2004–2005.

1Obesity indicates ≥ 95th percentile by gender & age for CDC charts.

2School Physical Activity and Nutrition

DISCUSSION

This study is the first in the United States to document a reduction in the prevalence of obesity in elementary school children in a regional population-based sample. This decrease occurred in a population at high risk, which is predominantly Hispanic/Latino and located on the Texas-Mexico border. In addition, a leveling of the prevalence of obesity was seen at all grade levels and in every region in Texas. SPAN data illustrate the importance of measuring the prevalence of child obesity at a local level, rather than relying on national or state estimates to monitor trends and document successful programs and policies.

Why was there such a large and significant change in 4th grade children in the El Paso area (HSR 9–10) compared to other regions in Texas? Although ecologic observational studies produce associational rather than causal data, the circumstantial evidence in favor of an effect is compelling, as several large evidence-based community- and school-level programs were heavily funded in the El Paso area in the years between the surveys. The program most relevant to the observed reduction in obesity observed in 4th grade students was a large, community-based health initiative, funded by the Paso del Norte (PDN) Health Foundation, that began with implementation of the Coordinated Approach To Child Health (CATCH) (27), but also included community-level programs for nutrition (28) and physical activity (29), as well as radio and television advertisements.

The CATCH El Paso initiative was funded for eight years (1997–2005), and included provision of training and materials to 162 schools in 14 districts, as well as continued support to schools through full-time program coordinators. (27, 30) The PDN Foundation selected CATCH because results from the main randomized controlled trial of CATCH found that the program significantly increased vigorous physical activity and decreased consumption of dietary fat; (31) a further follow-up study found that these effects were maintained for three years without further intervention. (32) Although other state child obesity initiatives have been conducted across the state using CATCH and other programs, the El Paso model was the largest and most comprehensive, with significant funding, multiple years of intervention, and evaluation.

A recently conducted replication study found that CATCH had significant effects on child obesity in a quasi-experimental study design in a Hispanic population. (33) In the Coleman study, after three years of intervention, an 11% reduction in the prevalence of at-risk and overweight was observed for girls in 5th grade in CATCH schools compared to girls in control schools; the decrease in boys was similar (−8%). (33) The results from the SPAN survey in 2004–2005 confirm the findings that Coleman and colleagues reported, and are especially noteworthy, as these two studies were conducted by separate investigative teams during different time periods.

CATCH has been widely disseminated in Texas using various funding sources since 1996 (36), and has currently been adopted by more than 2200 schools in Texas (data not shown). Data on the percentage of SPAN schools adopting CATCH were not related to the 4th grade obesity levels. For example, in El Paso County, 81% of elementary schools adopted CATCH with a 2004–05 4th grade student obesity prevalence of 17%, whereas 100% of schools adopted the program in Victoria County (obesity prevalence of 27%) and 29% of Bell County schools adopted the program (obesity prevalence of 14%). Although levels of CATCH program implementation and other community initiatives were not measured in these counties as they were in the El Paso area, no county in Texas had the extensive community support, resources and funding for obesity prevention provided by PDN in the El Paso area. Although speculative, from this ecologic observational study, it appears that adoption of a coordinated school health program with state-wide policies is not sufficient to decrease the prevalence of child obesity without significant resources for implementation or community support.

In addition to the CATCH Program in the schools, several other community-level initiatives were conducted by Paso del Norte Foundation between 2000–2002 and 2004–2005 that provided further support to the school-based efforts for healthy diet and physical activity. These included: Walk El Paso, a program to encourage walking for exercise in the community; (29) Qué Sabrosa Vida, a community based education program for mothers and caregivers to promote incorporation of healthy nutrition and physical activity into the lifestyle while keeping the rich tradition of the Mexican American diet and foods; (28) and media efforts to promote these programs. Perry and Kelder have reported similar synergistic effects in the Class of 1989 study, where school-based program effects on diet, physical activity and tobacco use were enhanced by the Minnesota Heart Health Program, a community-based heart health promotion. (34, 35) A more recent study, conducted in Somerville, MA, found that a community-based program that included a school program, community initiatives and social marketing efforts was effective in decreasing BMI in elementary school children. (5)

A leveling off in the prevalence of obesity was noted between 2000–2002 and 2004–2005 for all other HSRs for grades 4, 8 and 11. This leveling off, however, should be seen as a positive result, as the prevalence of obesity among children had been increasing steadily during the past two decades, based on national estimates (NHANES), although recent data show the same leveling trend in the United States. (1) It appears that state-wide mandates for Coordinated School Health Programs, School Health Advisory Councils, and daily PE in elementary schools (Texas Education Agency Code 38.013 & 28.004), as well as the Texas Public School Nutrition Policy, which were implemented across all of the HSRs, may slow the rise in obesity prevalence among school children, but do not produce a significant decrease without significant programmatic and community support. Thus, any population-level maintenance in the child obesity level should be seen as cautiously optimistic and efforts should be intensified, while a decrease should be seen as significant progress in addressing child obesity.

Although these trends are encouraging, the data presented are ecologic, thus, are subject to limitations. Nevertheless, for the 4th grade students in El Paso, the ecologic evidence is statistically significant and compelling: the Coleman experimental study using CATCH found similar results; (33) CATCH has been fully implemented and funded for eight years; (27,30,33) complementary community programs were developed and supported; (28,29) and state elementary school legislation and policies encouraging healthy eating and physical activity in elementary schools were enacted during this time period. (10,13) Evaluation of public health interventions such as the El Paso experience can be considered ‘natural experiments’ that may lack the rigor of randomized controlled trials, but are more generalizable and practical to implement on a population basis. (37) In addition, the methodology for this survey is rigorous and consistent with other epidemiologic surveys that show significant population changes over time, such as NHANES. The area surveyed is also significant: the total population of HSR 9–10 was 1.3 million in 2006, (38) which is comparable to the population estimates for South Dakota and Wyoming combined. (39)

Other limitations of the study include student participation rates. Although the sample sizes for most of the regional estimates were robust, some grade levels had smaller than expected sample sizes and thus, less stable parameter estimates (Tables 1–3). Given that measurement of height and weight is non-invasive, and diet and physical activity are not usually considered sensitive survey topics, utilization of passive consent procedures would considerably improve participation rates. To more precisely monitor the child obesity epidemic, we recommend state mandates and school policies that allow blanket or passive consent of child obesity surveys. In the SPAN 2004–2005 state sample of over 23,000 students, we received fewer than 25 phone calls from parents, and no reports of adverse events.

Despite the limitations, these results indicate a more generalizable and significant public health effect of a community initiative than has previously been documented. The results of this survey emphasize the importance of evaluation of translational research, in which programs developed and evaluated in more rigorous study designs, are implemented in public health settings to achieve maximum reach and impact. (40,41) Finally, the results of this study provide some data on the initial effects of policies and programmatic efforts to prevent child obesity. Although many policies and programs for child obesity are currently being implemented in the U.S. and various states, little data on the actual effects and outcomes of these efforts are available to inform decision makers at local, state, and national levels, with the recent exception of Arkansas (42).

Another unique aspect of these results is that, although significant effects were noted in local and regional results, a non-significant statewide decrease was observed. (15) Outcome measurements for obesity prevention programs for children should perhaps be conducted using smaller units of evaluation, especially in states with a large and diverse population, such as Texas. It is also important that current efforts, such as those in the El Paso area, be maintained until population goals for the prevalence of obesity are met. Withdrawing or decreasing support from the current initiatives without complete institutionalization of the programs into the community could lead to backsliding and potential increases in the current levels of child obesity in the region. (2)

Both leveling off and significant decreases in the prevalence of child obesity have been documented in Texas, specifically in the El Paso area among 4th grade students. Although these changes are noteworthy, the rates of child obesity at all HSR areas are greater than the targeted goal of a 5% prevalence of obesity. (43) The policy implications of this study are significant, especially since few studies have examined population-wide outcomes of community-based policies and programs. Results indicate that there are opportunities to reduce childhood obesity through comprehensive obesity prevention and control efforts that include an extensive community program for obesity prevention, an evidence-based elementary school health promotion program, adult nutrition and physical activity programs, and a radio and television advertising campaign, even among underserved populations. Data from this study also suggest that regulatory and educational efforts to prevent child obesity in schools should be sustained and intensified, and community-level programs and policies should be developed to support the school programs, as well as involve clinicians in these efforts. Current data, including our own, indicate a synergistic effect of all of these approaches is necessary for a decrease in child obesity. Finally, this study illustrates the importance of state and local surveys of child obesity, especially at regional levels, to monitor the effects of local prevention efforts as well as to inform and provide evidence to decision makers and to support policy and environmental change at the state and local level.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Texas Department of State Health Services with funds from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Health and Human Services Block Grant, the Michael & Susan Dell Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health, National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NCMHD), P20MD000170-019001 and P20MD000170-019003.

The authors of this manuscript would like to acknowledge Jerri Ward, MS, RD, for coordination of the data collection, Roy Allen, MS, for database management and Tiffni Menendez, MPH, Elizabeth Camp, MPH, and Donna Nichols, MSEd, CHES, for editorial assistance. We would also like to acknowledge staff of the Texas Department of State Health Services Nutrition, Physical Activity and Obesity Prevention program for assistance with data collection; Kimberley Bandelier, MPH, RD; Lesli Beidinger, MPH, RD; and Kristy Hanson, M.Ed., CHES, for assistance with data collection and coordinating the data collection process; and the school districts, schools, and children who participated in the study.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

Dr. Hoelscher receives funding from Flaghouse, Inc., the Michael & Susan Dell Foundation, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for development, dissemination and evaluation of CATCH. Dr. Kelder receives funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Active Living Program, the Texas Department of State Health Services, Houston Endowment through the Harris County and Public Health Environmental, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for development, dissemination and evaluation of CATCH. The University of Texas School of Public Health receives royalties based on sale of CATCH curriculum, of which 100% goes back into further research and development. Dr. Day receives funding from the Paso del Norte Health Foundation for development and evaluation of the Qué Sabrosa Vida community nutrition program.

The funding organizations listed above were not involved in the data management, analysis, or interpretation of the data, or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The Texas Department of State Health Services assisted with the design and conduct of the study.

Contributor Information

D. M. Hoelscher, Email: Deanna.M.Hoelscher@uth.tmc.edu.

A. Pérez, Email: adriana.perez@uth.tmc.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. High body mass index for age among US children and adolescents, 2003–2006. JAMA. 2008;299(20):2401–2405. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.20.2401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swinburn B. Obesity prevention in children and adolescents. Child Adol Psychatric Clin North America. 2009;18(1):209–223. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2008.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kropski JA, Keckley PH, Jensen GL. School-based obesity prevention programs: an evidence-based review. Obesity. 2008;16(5):1009–1018. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Dietetic Association. Position of the American Dietetic Association: Individual-, family-, school-, and community-based interventions for pediatric overweight. J Amer Diet Assoc. 2006;106:925–945. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Economos CD, Hyatt RR, Goldberg JP, Must A, Naumova EN, Collins JJ, et al. A community intervention reduces BMI z-score in children: Shape up Somerville first year results. Obesity. 2007 May;15(5):1325–1336. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gortmaker SL, Peterson K, Wiecha J, Sobol AM, Dixit S, Fox MK, et al. Reducing obesity via a school-based interdisciplinary intervention among youth: Planet Health. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(4):409–418. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.4.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robinson TN. Reducing children's television viewing to prevent obesity: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1999;282(16):1561–1567. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.16.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spiegel SA, Foulk D. Reducing overweight through a multidisciplinary school-based intervention. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006 Jan;14(1):88–96. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaloupka FJ, Johnston LD. Bridging the Gap: research informing practice and policy for healthy youth behavior. Am J Prev Med. 2007 Oct;33(4 Suppl):S147–S161. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Texas Education Agency. The Texas Education Code (TEC), Chapter 38, Health and Safety, Subchapter A, General Provisions, §38.013, Coordinated Health Program for Elementary, Middle, and Junior High School Students. 19 TAC §102.1031, Chapter 102. Educational Programs, Subchapter CC. Commissioner's Rules Concerning Coordinated Health Programs. 2005. Texas Education Code

- 11.Allensworth DD, Kolbe LJ. The comprehensive school health program: exploring an expanded concept. J Sch Health. 1987 Dec;57(10):409–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [cited 2006 Nov 2];Healthy Youth!: Coordinated School Health Program. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Division of Adolescent and School Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. 2005 Jul 1; Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/cshp/

- 13.Texas Department of Agriculture. [cited 2006 Nov 2];Texas Public School Nutrition Policy. Texas Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Division. 2006 Available from: URL: http://www.squaremeals.org/fn/render/parent/channel/0,1253,2348_2350_0_0,00.html.

- 14.Hoelscher DM, Day RS, Lee ES, Frankowski RF, Kelder SH, Ward JL, et al. Measuring the prevalence of overweight in Texas schoolchildren. Am J Public Health. 2004 Jun;94(6):1002–1008. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.6.1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoelscher D, Perez A, Kelder S, Day R, Sanders J, Frankowski R, et al. Leveling off of the prevalence of overweight in elementary school children in Texas: Results from the 2000–2002 and 2004–2005 School Physical Activity and Nutrition (SPAN) surveillance system. Under review [Google Scholar]

- 16.Texas Department of State Health Services. Health Service Regions. 2006 Sep 5; Available from: URL: http://www.dshs.state.tx.us/regions/default.shtm.

- 17.Hoelscher DM, Day RS, Kelder SH, Ward JL. Reproducibility and validity of the secondary level School-Based Nutrition Monitoring student questionnaire. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003 Feb;103(2):186–194. doi: 10.1053/jada.2003.50031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Texas Education Agency. [cited 2006 Oct 3];2003–2004 Student Enrollment Reports. 2006 Jun 21; Available from: URL: http://www.tea.state.tx.us/adhocrpt/adste04.html; http://www.tea.state.tx.us/adhocrpt/Standard_Reports.html.

- 19.Penkilo M, George GC, Hoelscher DM. Reproducibility of the School-Based Nutrition Monitoring Questionnaire among Fourth-grade Students in Texas. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2008 Jan;40(1):20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2007.04.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thiagarajah K, Bai Y, Lo K, Leone A, Shertzer J, Hoelscher D. Assessing validity of food behavior questions from the School Physical Activity and Nutrition Questionnaire. Society for Nutrition Education Annual Conference Proceedings; 2006. pp. 55–56. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nihiser AJ, Lee SM, Wechsler H, McKenna M, Odom E, Reinold C, et al. Body mass index measurement in schools. J Sch Health. 2007 Dec;77(10):651–671. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [cited 2006 Nov 1];How is BMI calculated and interpreted? 2006 Aug 28; Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpa/bmi/adult_BMI/about_adult_BMI.htm#Interpreted.

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Growth Charts. [Pamphlet] 5-30-2000. 2000 12-4-2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krebs NF, Himes JH, Jacobson D, Nicklas TA, Guilday P, Styne D. Assessment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity. Pediatrics. 2007 Dec;120(Suppl 4):S193–S228. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2329D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, Ross J, Hawkins J, Harris WA, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance--United States, 2005. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2006 Jun 9;55(5):1–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. [cited 2009 Jun 8];DSHS Center for Health Statistics, Texas Population Data. [Online] 2009 [1 screen]. Available from: www.dshs.state.tx.us/CHS/popdat/SummX.shtm.

- 27.Coleman KJ. Mobilizing a low income border community to address state mandated coordinated school health. Am J Health Educ. 2006 Jan;37(1):13–26. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith WE, Day RS, Brown LB. Heritage retention and bean intake correlates to dietary fiber intakes in Hispanic mothers--Que Sabrosa Vida. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005 Mar;105(3):404–411. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coleman KJ, Tinajero T, Galaviz J, Martinez E, Herrald M, Pauli A. Impact of a community-wide walking initiative on the U.S./Mexico Border. Oral presentation at the Fourth International Conference on Walking in the 21st Century; 2003 May 1–3; Portland, OR. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heath EM, Coleman KJ. Adoption and institutionalization of the Child and Adolescent Trial for Cardiovascular Health (CATCH) in El Paso, Texas. Health Promot Pract. 2003 Apr;4(2):157–164. doi: 10.1177/1524839902250770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luepker RV, Perry CL, McKinlay SM, Nader PR, Parcel GS, Stone EJ, et al. Outcomes of a field trial to improve children's dietary patterns and physical activity. The Child Adolescent Trial for Cardiovascular Health. CATCH collaborative group. JAMA. 1996 Mar 13;275(10):768–776. doi: 10.1001/jama.1996.03530340032026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nader PR, Stone EJ, Lytle LA, Perry CL, Osganian SK, Kelder S, et al. Three-year maintenance of improved diet and physical activity: the CATCH cohort. Child and Adolescent Trial for Cardiovascular Health. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999 Jul;153(7):695–704. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.7.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coleman KJ, Tiller CL, Sanchez J, Heath EM, Sy O, Milliken G, et al. Prevention of the epidemic increase in child risk of overweight in low-income schools: the El Paso coordinated approach to child health. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005 Mar;159(3):217–224. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.3.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kelder SH, Perry CL, Klepp KI. Community-wide youth exercise promotion: long-term outcomes of the Minnesota Heart Health Program and the Class of 1989 Study. J Sch Health. 1993 May;63(5):218–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1993.tb06125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kelder SH, Perry CL, Lytle LA, Klepp KI. Community-wide youth nutrition education: long-term outcomes of the Minnesota Heart Health Program. Health Educ Res. 1995 Jun;10(2):119–131. doi: 10.1093/her/10.2.119-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoelscher DM, Kelder SH, Murray N, Cribb PW, Conroy J, Parcel GS. Dissemination and adoption o fthe Child and Adolescent Trial for Cardiovascular Health (CATCH): a case study in Texas. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2001 Mar;7(1):90–100. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200107020-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petticrew M, Cummins S, Ferrell C, Findlay A, Higgins C, Hoy C, et al. Natural experiments: an underused tool for public health? Public Health. 2005 Sep;119(9):751–757. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Texas Department of State Health Services. [cited 2008 Mar 8];Population data (estimates) for Texas counties, 2005. Texas Department of State Health Services. 2008 Available from: URL: http://www.dshs.state.tx.us/chs/popdat/ST2005.shtm.

- 39.U.S.Census Bureau. [cited 2008 Mar 8];Population estimates. U S Census Bureau. 2008 Available from: URL: http://www.census.gov/popest/estimates.php.

- 40.Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999 Sep;89(9):1322–1327. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zerhouni EA. Translational and clinical science--time for a new vision. N Engl J Med. 2005 Oct 13;353(15):1621–1623. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb053723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raczynski JM, Thompson JW, Phillips MM, Ryan KW, Cleveland HW. Arkansas Act 1220 of 2003 to reduce childhood obesity: its implementation and impact on child and adolescent body mass index. J Public Health Policy. 2009 Jan;30(Suppl 1):S124–S140. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2008.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010. 2nd. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2000. [Google Scholar]